Dynamic Parameter Identification Method for Space Manipulators Based on Hybrid Optimization Strategy

Abstract

1. Introduction

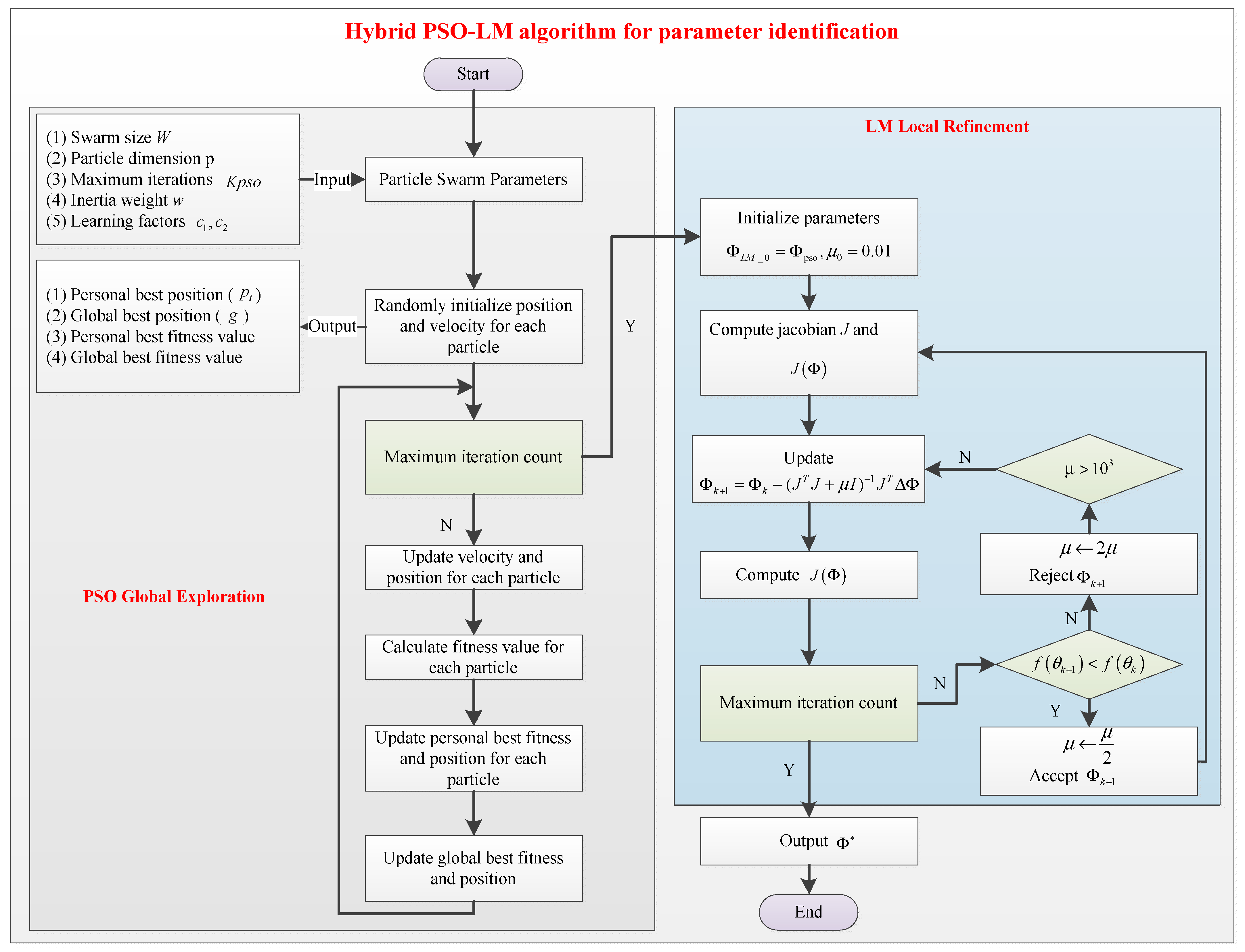

- A dynamic parameter identification method combining PSO and LM algorithms is proposed, balancing global search capability and local optimization accuracy. This method uses PSO for initial parameter estimation and then refines them with the LM algorithm, significantly improving identification accuracy while ensuring computational efficiency, making it particularly suitable for small-sample optimization problems in space missions.

- A nonlinear friction model incorporating Stribeck effects adapted to the space environment is established, revealing the influence mechanisms of vacuum, microgravity, and temperature variations on joint friction. Studies show that the space environment significantly alters friction parameter characteristics, leading to the proposal of an adaptive on-orbit modification method based on environmental monitoring, effectively enhancing the model’s environmental adaptability.

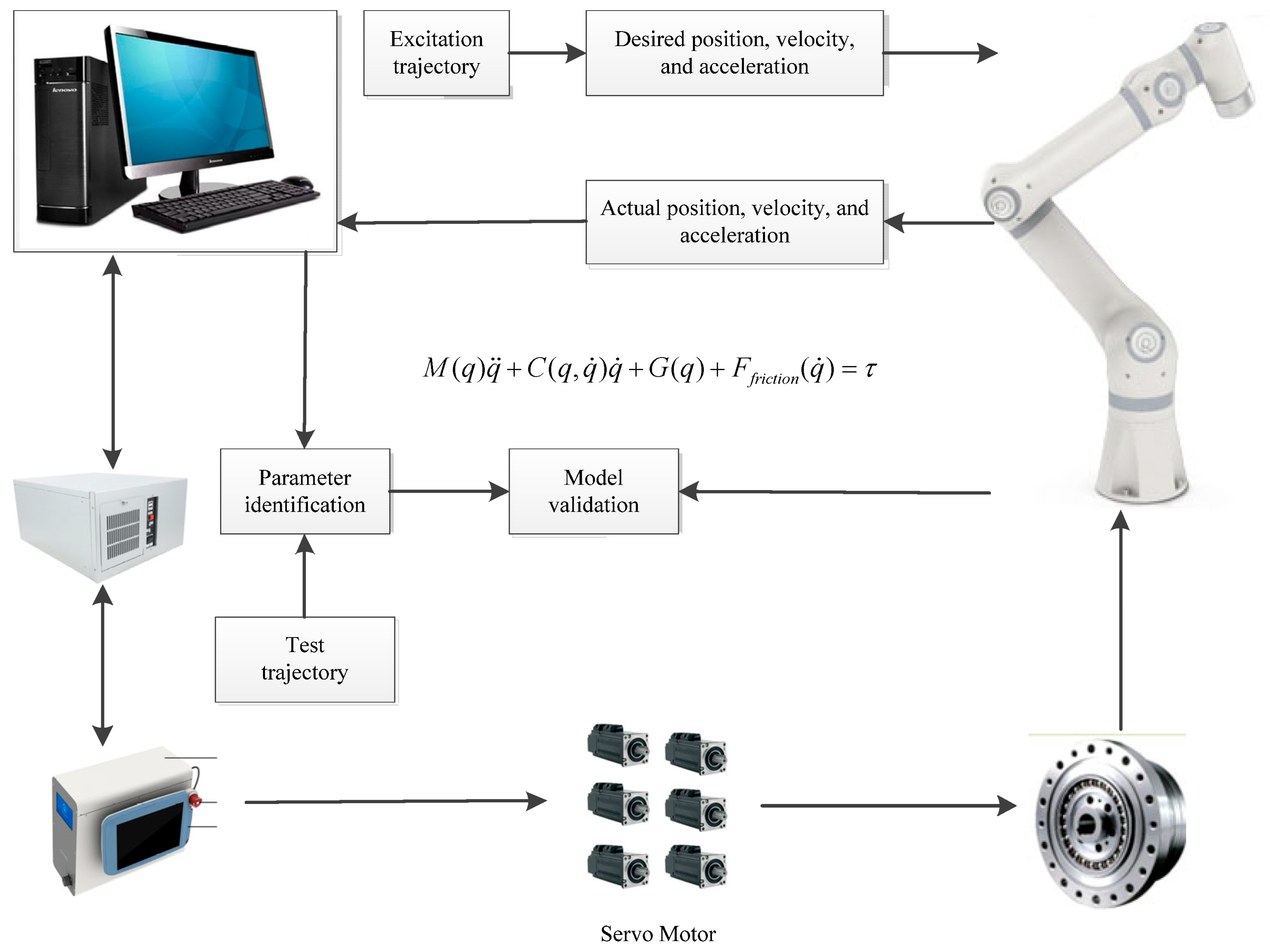

- To validate the effectiveness of the proposed dynamic parameter identification method, a 6-DOF space manipulator experimental platform without additional torque sensors was designed and built. By fusing joint current signals and motion state data, combined with an improved dynamic modeling method, high-precision parameter identification under conditions without direct torque measurement was achieved.

2. Space Manipulator Dynamic Modeling and Model Linearization

2.1. Rigid Body Dynamic Model

2.2. Space Manipulator Friction Model

2.2.1. Improved Stribeck Friction Model

- characterizes the Stribeck transition effect from static to Coulomb friction;

- represents linear viscous friction;

- and are used to describe nonlinear velocity-dependent friction.

2.2.2. Space Environment Adaptability Analysis

- Microgravity environment: The disappearance of gravity leads to changes in gear preload distribution within the gearbox, causing the static friction coefficient to drift. The strategy is to calibrate in real-time on orbit using adaptive update algorithms based on joint torque feedback.

- Vacuum environment: The disappearance of air resistance causes higher-order friction terms related to air damping (especially and ) to decrease significantly or even approach zero. In this environment, especially and can be ignored or set to zero. Under such conditions, and may be neglected or set to zero. Their corresponding coefficients can be initially estimated through ground-based vacuum chamber experiments or derived from aerodynamic theory, with final calibration performed using on-orbit data.

- Temperature variation environment: Lubricant viscosity changes with temperature, causing nonlinear shifts in parameters such as the Coulomb friction coefficient and Stribeck characteristic velocity . Therefore, temperature compensation functions can be introduced into the friction model. For example, the relationship between the Coulomb friction coefficient and temperature T can be expressed as follows:where: is the reference Coulomb friction value at reference temperature ; is the friction-temperature sensitivity coefficient (reflecting the rate of change in with temperature); is the current ambient temperature; is the reference temperature (e.g., 20 °C).

2.3. Model Linearization

2.3.1. Linearization Objective

2.3.2. Parameter Linearization

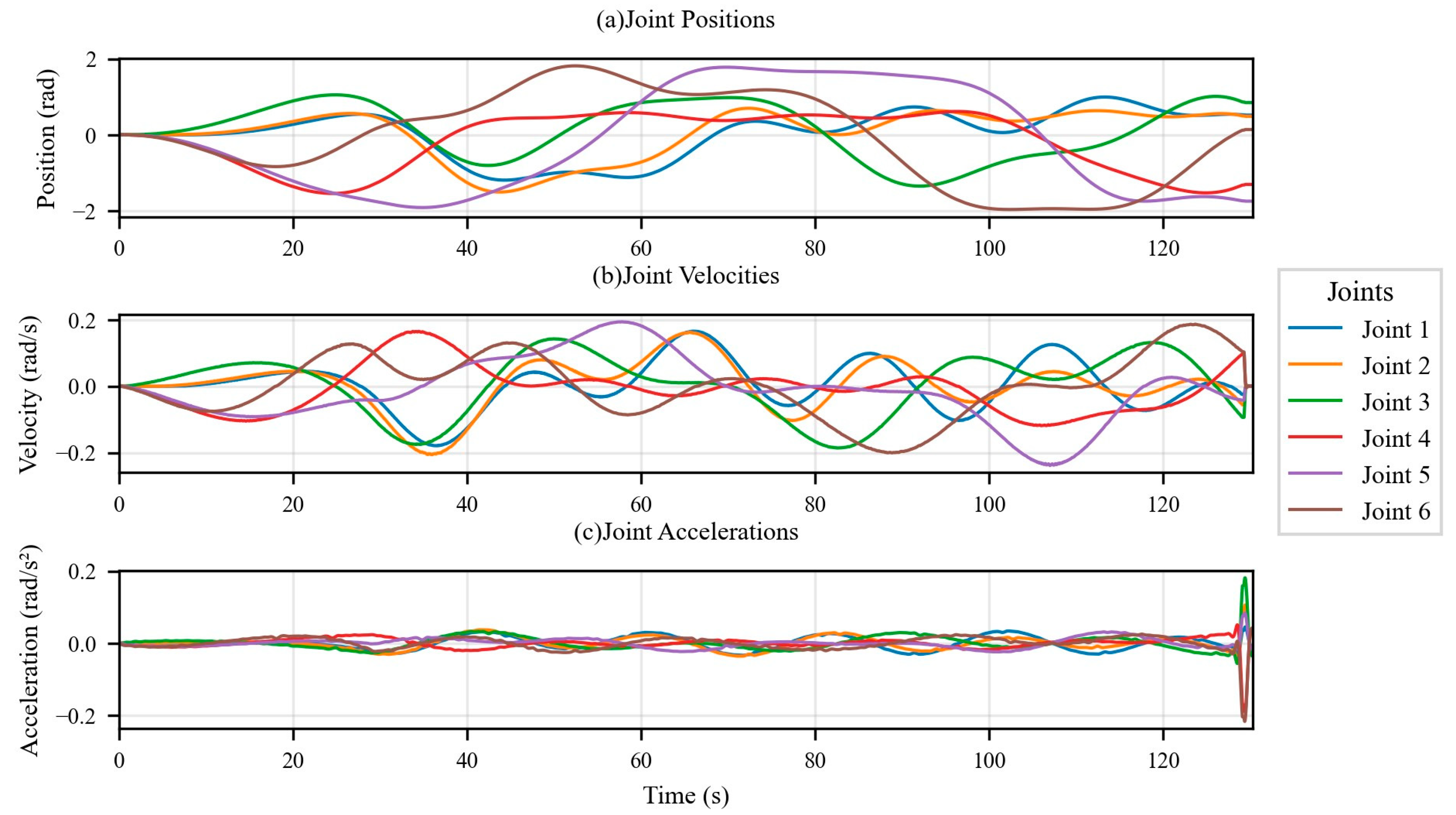

3. Excitation Trajectory Optimization Design

3.1. Optimization Objectives and Theoretical Basis

3.2. Fourier Series Excitation Trajectory Design

- Periodicity: Periodic trajectories allow for repeated experiments. Time-domain averaging of sampled data can significantly improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the data.

- Analytical Differentiation: Velocity and acceleration signals can be obtained directly through analytical differentiation of the position trajectory, avoiding additional noise introduced by numerical differentiation.

- Bandwidth Control: By limiting the highest frequency component of the Fourier series, the bandwidth of the excitation trajectory can be effectively controlled, avoiding excitation of the robot’s unmodeled high-frequency dynamics or natural frequencies and preventing resonance phenomena.

4. Hybrid PSO-LM Algorithm for Dynamic Parameter Identification

4.1. PSO-LM Algorithm

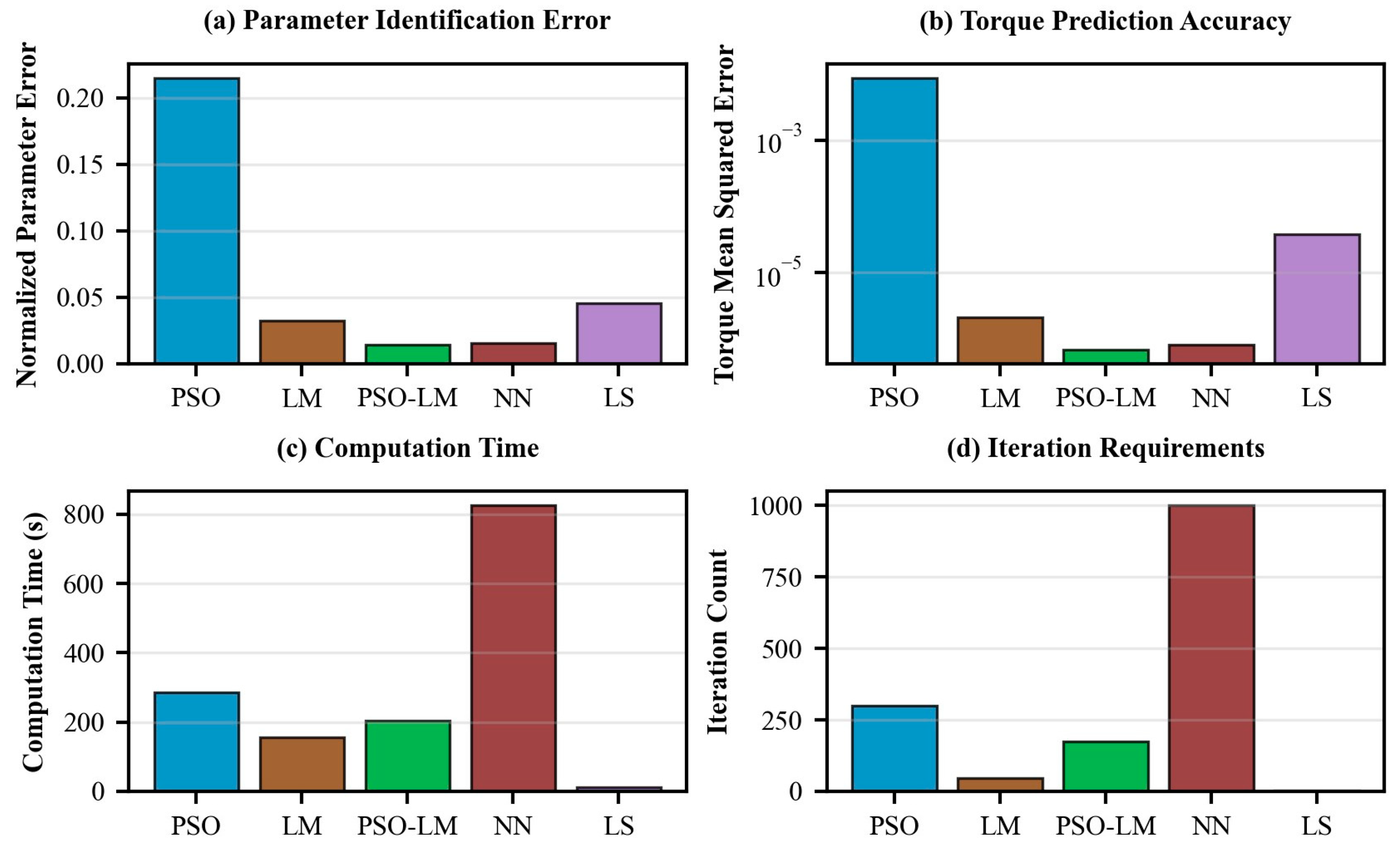

4.2. Evaluation of Dynamics Parameter Identification Algorithms Based on Simulation

5. Experimental Verification

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Experimental Platform Construction

5.1.2. Validation Method

5.2. Dynamic Parameter Identification Verification and Analysis

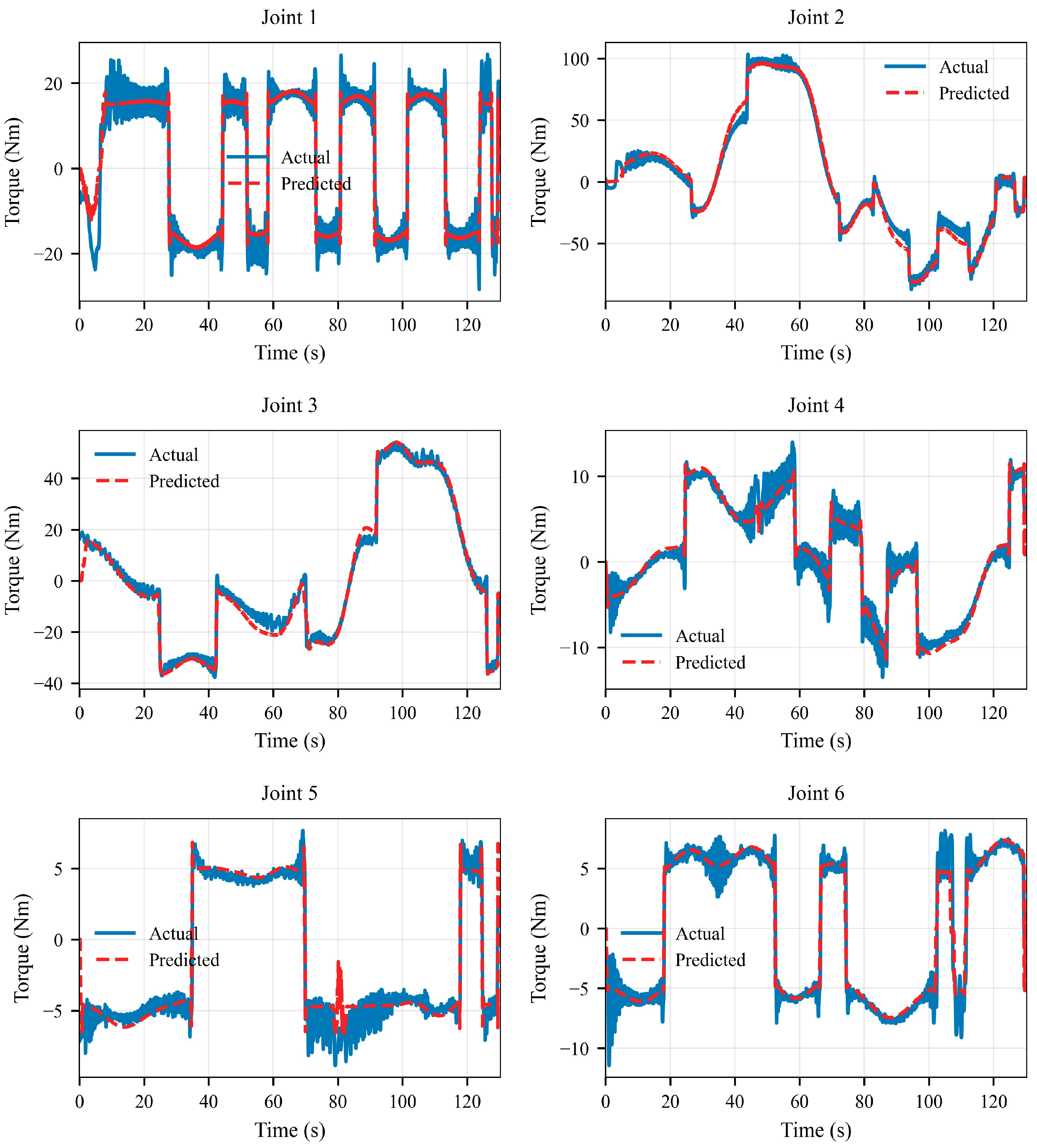

5.2.1. Validation Trajectory and Torque Prediction

5.2.2. Quantitative Accuracy Analysis

5.2.3. Discussion and Analysis for Space Applications

6. Conclusions

- A nonlinear dynamic model for space manipulators incorporating an improved Stribeck friction term is established. This model elucidates the influence mechanisms of vacuum, microgravity, and temperature variations on joint friction, and an adaptive on-orbit correction method based on environmental monitoring is proposed.

- A hybrid parameter identification method integrating Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) algorithm is proposed. This method leverages the global search capability of PSO and the fast local convergence of LM, achieving significant improvements in identification accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

- Excitation trajectories are designed using Fourier series. By optimizing the harmonic components, the condition number of the observation matrix is significantly improved, effectively enhancing parameter identifiability.

- The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated on a six-degree-of-freedom ground-based manipulator test platform. All 108 dynamic parameters are successfully identified, with the correlation coefficients between predicted and measured joint torques exceeding 0.97, and the root mean square errors remaining below 5.1 N·m.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chien, S.A.; Visentin, G.; Basich, C. Exploring beyond Earth using space robotics. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadi6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.Y.; Jiang, Z.N.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Z.W. Advances in Space Robots for On-Orbit Servicing: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Intell. Syst.-Ger. 2023, 5, 2200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotras, P.; King-Smith, M.; Ticozzi, L. Spacecraft-Mounted Robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 6, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, L.J.; Wang, G.K.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.M.; Wang, L.J.; Dong, J.M.; Guo, B.W. Trajectory Optimization and Simulation of Aerospace Robotic Arm. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 655, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woerkom, P.T.L.M.; Misra, A.K. Robotic manipulators in space: A dynamics and control perspective. Acta Astronaut. 1996, 38, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; She, Y.; Xu, W.; Lu, W.; Liang, B. Dynamic modeling and vibration characteristics analysis of flexible-link and flexible-joint space manipulator. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2018, 43, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Chen, W.; Shao, M.; Ni, S. Trajectory Tracking and Adaptive Fuzzy Vibration Control of Multilink Space Manipulators with Experimental Validation. Actuators 2023, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Deng, F.; Guo, S. Dynamics Modeling and Parameter Identification for a Coupled-Drive Dual-Arm Nursing Robot. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xu, S.; Han, M.; Li, T.; Liu, J. Identification and application of dynamic parameters of manipulator based on improved IRLS algorithm. Ind. Robot Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2024, 52, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, Z.L.; Jia, Q.X.; Sun, H.X. Dynamic Parameter Identification of Unknown Object Handled by Space Manipulator. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 487, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidi-Loumpasefski, O.-O.; Papadopoulos, E. On the parameter identification of free-flying space manipulator systems. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 160, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.R.; Fang, J.W.; Qi, S.A.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.L.; Ren, H.J. Step-by-step identification of industrial robot dynamics model parameters and force-free control for robot teaching. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 3747–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.; Souza, D.; dos Reis, L.; Barbosa, A.; Araújo, R. Dynamic Model and Inverse Kinematic Identification of a 3-DOF Manipulator Using RLSPSO. Sensors 2020, 20, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hu, H. Dynamic parameter identification and adaptive control with trajectory scaling for robot-environment interaction. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.; Bao, S.; Lai, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z. A dynamic model parameter identification method for quadrotors using flight data. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 233, 1990–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon, C.L.C.-D.; Vergara-Limon, S.; Vargas-Trevino, M.A.D.; Lopez-Gomez, J.; Gonzalez-Calleros, J.M.; Gonzalez-Arriaga, D.M.; Vargas-Trevino, M. Parameter Identification of a Robot Arm Manipulator Based on a Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 55002–55019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wu, K.; Hui, N. Co-Optimization of Vibration Suppression and Data Efficiency in Robotic Manipulator Dynamic Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Liu, G.; Lu, Z.; Hu, L.; Han, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X. Dynamic parameter identification based on improved particle swarm optimization and comprehensive excitation trajectory for 6R robotic arm. Ind. Robot Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2023, 51, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Zhao, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q. Deep-reinforcement learning aided dynamic parameter identification of multi-joints manipulator. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Technol. Appl. 2024, 22, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.Q.; Yuan, J.J.; Hu, Z.T.; Du, L.; Bao, S.; Zhou, M.J. Lie-theory-based dynamic model identification of serial robots considering nonlinear friction and optimal excitation trajectory. Robotica 2024, 42, 3552–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-P.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Chen, J.-L.; Cao, J.-F.; Fu, Y.; Li, S.-Q. An improved parameter identification method of redundant manipulator. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 17298814211002118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Li, H.Q.; Wang, J.S.; Cai, G.P. Dynamics analysis of flexible space robot with joint friction. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2015, 47, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yin, Z.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, K. Dynamics Parameter Identification of Articulated Robot. Machines 2024, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, A.; Bertleff, W.; Elhardt, F.; Iskandar, M.; Beck, F.; Rebele, B.; Stemmer, A.; Beyer, A.; Schedl, M.; Albu-Schäffer, A.; et al. Friction in Space—Analysis of Robotic Joint Friction in Space Conditions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–8 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lampaert, V.; Swevers, J.; Al-Bender, F. Modification of the Leuven integrated friction model structure. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 47, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichalar, J.; Ostrom, C. Estimating Drag and Heating Coefficients for Hollow Reentry Objects in Transitional Flow Using Direct Simulation Monte Carlo. In Proceedings of the First International Orbital Debris Conference, Sugar Land, TX, USA, 9–12 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Arya, Y.; Xia, Y. An Accurate Dynamic Model Identification Method for Industrial Robots Based on Improved Excitation Trajectory. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electron. Netw. Devices Fields 2025, 38, e70062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yao, B.; Ma, X. On the Fully Decoupled Rigid-body Dynamics Identification of Serial Industrial Robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 4588–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgarm, N.; Sajadi, B.; Kowsary, F.; Delgarm, S. Multi-objective optimization of the building energy performance: A simulation-based approach by means of particle swarm optimization (PSO). Appl. Energy 2016, 170, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budil, D.E.; Lee, S.; Saxena, S.; Freed, J.H. Nonlinear-Least-Squares Analysis of Slow-Motion EPR Spectra in One and Two Dimensions Using a Modified Levenberg–Marquardt Algorithm. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. A 1996, 120, 155–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Joint 1 | Joint 2 | Joint 3 | Joint 4 | Joint 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.9695 | 7.2326 | 2.0867 | 1 × 10−6 | 3.7425 | |

| 19.7469 | 37.8161 | 14.1530 | 7.3522 | 5.3967 | |

| 0.0574 | 0.4232 | −0.3233 | 0.7128 | 0.2969 | |

| −0.1671 | −0.1859 | −0.0090 | −0.0300 | 0.2570 | |

| 14.8791 | 12.0478 | 15.5775 | 4.0419 | 4.5851 | |

| 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | 0.0055 | 1 × 10−3 | 0.0011 | |

| 20.1409 | 12.3278 | 18.3598 | 6.0389 | 7.3202 | |

| 0.02258 | 1 × 10−6 | 1 × 10−6 | 1 × 10−6 | 1 × 10−6 | |

| 6.0683 | 6.4725 | 4.2054 | 2.7177 | 2.6093 | |

| −1 × 10−5 | −2 × 10−5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.0464 | −0.2869 | 0.2762 | −0.0454 | 0.0425 | |

| −0.2781 | −0.1292 | 0.0584 | −0.1970 | −0.1680 | |

| 0.5006 | 0.8002 | 0.4125 | 0.1163 | 0.0829 | |

| −3 × 10−5 | −4 × 10−5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 × 10−5 | −2 × 10−5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.4833 | 0.1253 | 0.0241 | 0.1081 | 0.0761 | |

| −0.0798 | 0.2242 | 0.0780 | 0.0245 | −0.0188 | |

| 0.0309 | 0.6887 | 0.3941 | 0.0108 | 0.0093 |

| Joint No. | RMSE (N·m) | Max Error (N·m) | MAE (N·m) | Correlation Coefficient (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint 1 | 3.9462 | 22.8779 | 2.5430 | 0.9737 |

| Joint 2 | 5.0670 | 21.3276 | 3.9640 | 0.9953 |

| Joint 3 | 3.2432 | 19.0617 | 2.2192 | 0.9941 |

| Joint 4 | 1.4322 | 7.7453 | 1.0329 | 0.9740 |

| Joint 5 | 1.0583 | 8.3433 | 0.6640 | 0.9753 |

| Joint 6 | 1.1699 | 8.1504 | 0.6278 | 0.9815 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jing, H.; Ma, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, J. Dynamic Parameter Identification Method for Space Manipulators Based on Hybrid Optimization Strategy. Actuators 2025, 14, 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14100497

Jing H, Ma X, Chen M, Chen J. Dynamic Parameter Identification Method for Space Manipulators Based on Hybrid Optimization Strategy. Actuators. 2025; 14(10):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14100497

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Haitao, Xiaolong Ma, Meng Chen, and Jinbao Chen. 2025. "Dynamic Parameter Identification Method for Space Manipulators Based on Hybrid Optimization Strategy" Actuators 14, no. 10: 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14100497

APA StyleJing, H., Ma, X., Chen, M., & Chen, J. (2025). Dynamic Parameter Identification Method for Space Manipulators Based on Hybrid Optimization Strategy. Actuators, 14(10), 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14100497