1. Introduction

Large-scale frames have always played a pivotal role in the field of engineering structures. They have been widely used in traditional civil structures, and related technologies are also mature enough. In new application fields, especially in aerospace science, there are still many problems with large-scale frames that need to be studied. This paper chooses a space-based planar phased array antenna as an example to explore shape adjustment for large-scale structures.

Planar phased array antennas, a typical application for large-scale frames, have been widely used in space satellites. Due to the need for ground observation and target monitoring, it is desirable to arrange satellites in higher orbits to obtain a larger field of view [

1]. To maintain the same cross-range resolution, the horizontal length of the antenna is roughly proportional to the slant range [

2]. As a result, there is increasing attention being paid to large-scale antennas.

As the size of the antenna increases, many new problems will arise. There are many radiators and receivers arranged on the feed panels of planar phased array antennas to transmit and receive electromagnetic waves to and from observation targets in order to carry out observations of these targets. When performing observation tasks, these radiators will generate electromagnetic waves with different phases according to their pre-designed locations on the antenna array feed panels. When the deformation is small, the antenna’s electrical performance can be ensured by electrical compensation. Once the antenna deformation exceeds the allowable value, the radiators will deviate from their designed positions, which will immediately impact the antenna’s observation accuracy. Therefore, the shape accuracy of antennas has a crucial impact on their performance. However, the space environment in which satellites work is very complex. Antenna distortion can occur due to bending and twisting caused by temperature gradients or slewing maneuvers, resulting in less-than-desired shape accuracy, which is especially problematic for larger antennas. Scholars and experts have conducted much research in this field [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In order to examine how length uncertainties affect the geometric errors of antennas, Greschik et al. [

8] conducted a Monte Carlo study on a typical truss design. Compensation techniques that enable a multiple-order-of-magnitude reduction in structural requirements were identified by Murphey et al. [

9]. Tang et al. [

10] investigated three sources of figure errors: random thermal strains in orbit, fabrication imperfection, and faceted paraboloids. A shape accuracy optimization approach was proposed to determine the best pre-tensions of cables to achieve the desired configuration for a deployable antenna [

11]. Almost all the studies analyzed shape errors or proposed corresponding compensation strategies. However, most studies focus on mesh reflector antennas with cable nets, and research on such large-scale planar phased array antennas with great application potential still needs to be made available.

For large-scale planar phased array antennas, many mechanical compensation problems remain to be solved. These antennas are very long; when the antennas are deformed, the strain may not be large, but the displacement may not be small, so the linear model is no longer applicable. Indeed, this is a typical problem considering geometrical nonlinearity. To solve this problem, we need to establish a corresponding nonlinear model, and the finite element method is often used in structure modeling. The antenna structure is mainly composed of pre-tensioned cables, the supporting frame, and feed arrays. For some reasons mentioned later in this paper, the feed panels can be ignored in structure modeling. The pre-tensioned cables are modeled as nonlinear rod elements, and the supporting frame is modeled as nonlinear beam elements.

In terms of actuator selection, most researchers used piezoelectric ceramics, smart materials, etc., as actuators for shape control. Kalra et al. [

12] considered the shape control of a C-band parabolic space antenna reflector actuated by SMA wire. An innovative approach using several discrete actuators was presented by Andon et al. [

13] to achieve shape adjustment. Song et al. [

14] studied a reflector and developed experimental and theoretical approaches for shape control with PZT actuators. Wang et al. [

15] thoroughly investigated the shape control actuated by cables that incorporate a PZT. Furthermore, to increase the surface accuracy of reflectors, Wang et al. [

16] presented a structure that incorporates a PZT actuator with cables to achieve shape adjustment or surface correction. These studies have been effectively used in the field of antenna shape control. In recent years, research on large-aperture antennas has been increasing [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, there are still some obvious disadvantages, such as the additional mass that the actuator adds to the antenna structures. This paper proposes a scheme treating the inherent diagonal cables of the antenna as actuators. This scheme can effectively reduce the satellite load and has great application prospects. However, two major challenges remain in successfully implementing this approach. On the one hand, the inherent cables of the antenna will contribute to the deformation of the antenna structure as a load-bearing member when the antenna is subjected to external loads. In this case, the stiffness of the whole antenna structure should include the contribution of these cables. But when a cable is used as an actuator, it needs to be regarded as an active member. In this case, it does not resist its own effect, so its stiffness should be excluded from the stiffness of the whole antenna structure. On the other hand, for any cable in the antenna structure, the action of the other cables is equivalent to the external load. Therefore, when the cables in the antenna actuate simultaneously, there will be a coupling effect. To successfully achieve shape adjustment, another very important issue needs to be solved: the direction change of active cables. In most structural control problems, such as shape control or vibration control, the control forces’ directions do not change; only the control forces’ magnitudes are changed. However, in our problem, the situation is quite different; the active cables will deform along with the whole structure, and the control forces’ directions will also change during the entire control process. Therefore, accurately reflecting the change in the direction of control forces within the control model is a critical issue, which is also a difficult problem to solve in our paper. In order to address these issues, this paper analyses the difference between active cables and passive cables and proposes an optimization method that divides the control problem into several steps.

This paper is organized into six sections.

Section 2 describes the structure of the research object as well as the simplified structure studied in this paper. In

Section 3, the nonlinear model of the 3D cable element and the 3D beam element is established.

Section 4 introduces the detailed optimization method to achieve shape adjustment and gives the algorithm flow. In

Section 5, numerical simulations of a simplified 2-bay as well as an 18-bay antenna are carried out. Finally,

Section 6 gives the conclusions and suggestions.

2. Description of the Research Object

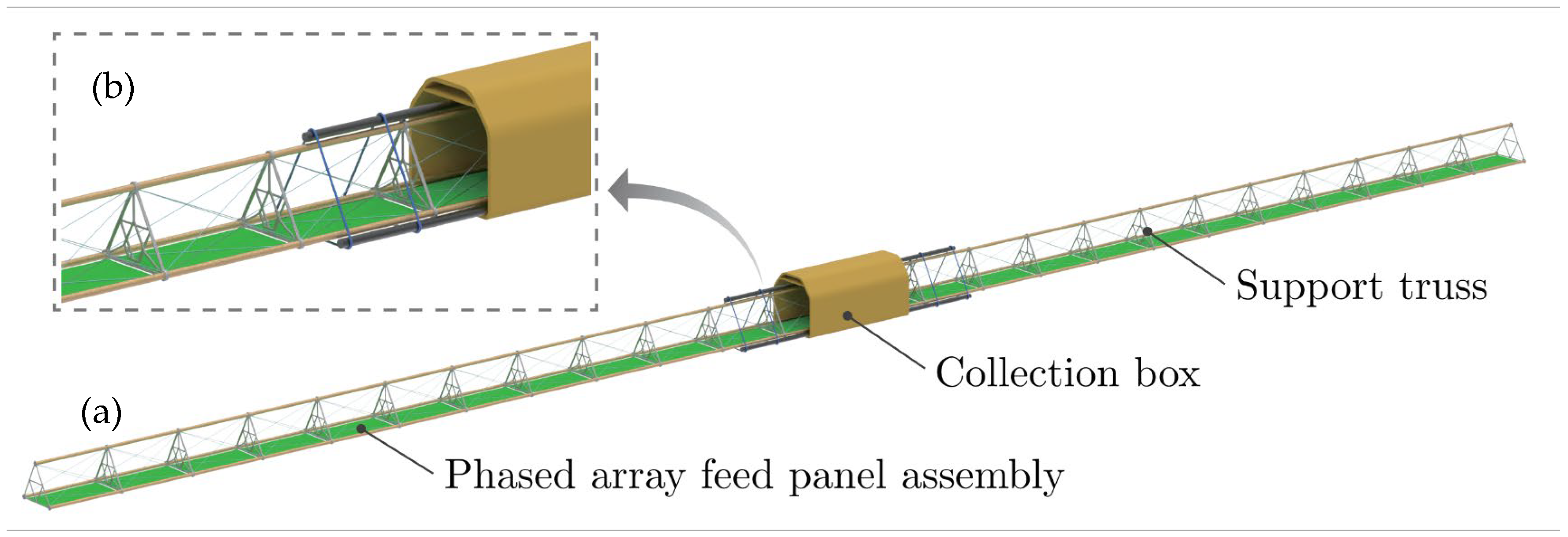

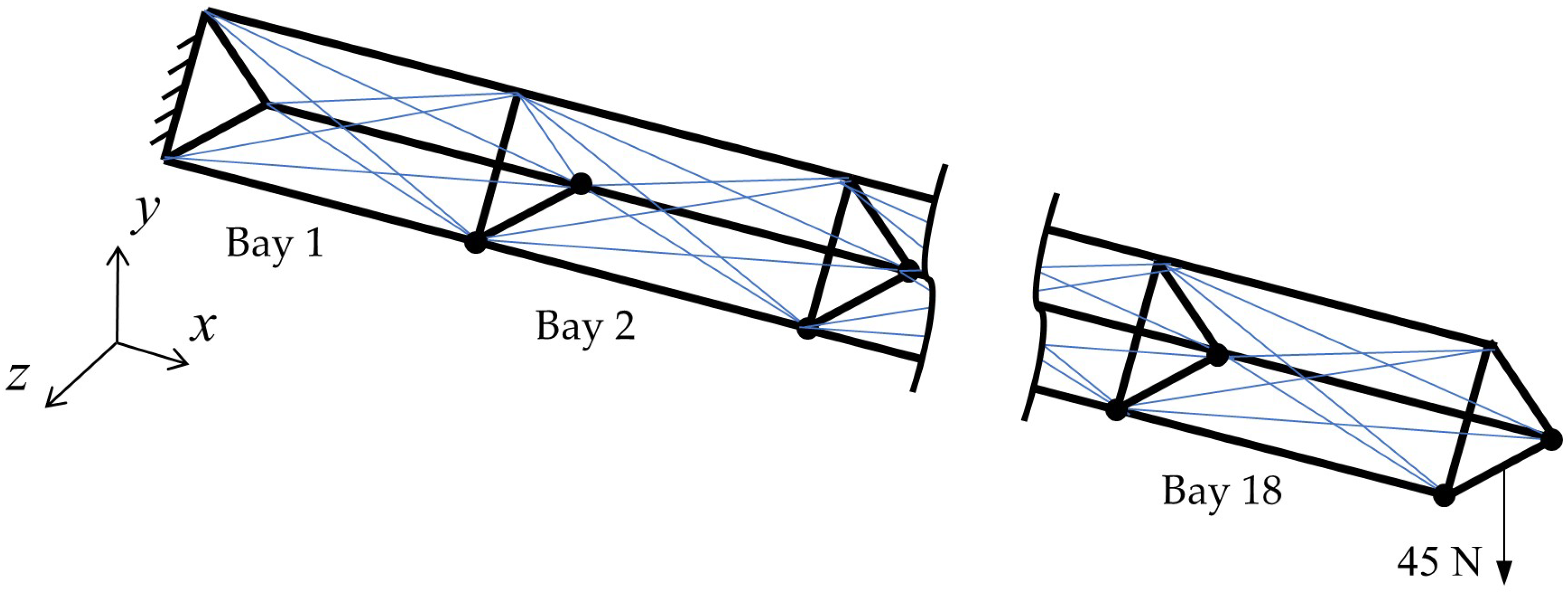

Figure 1a shows the research object; the antenna is mainly composed of three parts: (1) the collection box, (2) the supporting frame, and (3) the phased array feed panel assembly. Before launch, the supporting frame and the phased arrays are packaged in the collection box. Driven by the electric motors, the antenna will be deployed sequentially once the satellite enters its predetermined orbit. All hinges will be locked when the deployment is completed, and the final shape of the antenna is shown in

Figure 1a.

Figure 1b shows the local amplification of the antenna; we can see that there are several identical bays connected with each other.

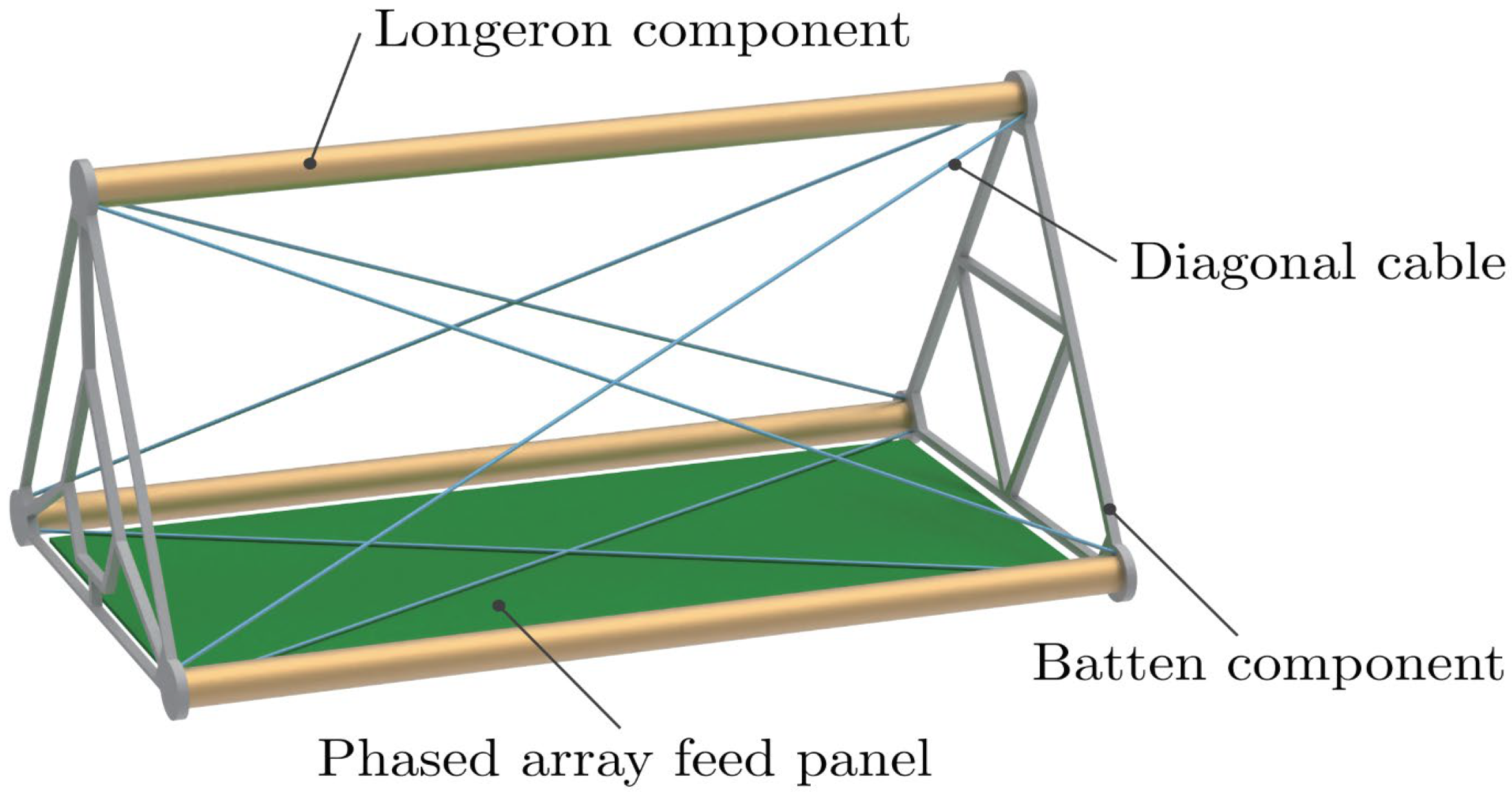

Figure 2 shows the structure of a typical bay. It can be seen that one phased array feed panel, three longeron components, and six batten components form the bay. Batten components form a triangle structure to increase the stability and rigidity of the bay; for the same reason, several connecting beams are intentionally added inside the triangle structure. Together with batten components, longeron components make the antenna form a triangular prism structure. The panels of the phased arrays are attached to the batten components using hinges. As shown in

Figure 2, the diagonal cables are arranged as shown. The satellite body has displacement sensors arranged to monitor the displacement of the nodes of interest. The relative displacement of the feed arrays along the antenna will decrease the coherence of the antenna arrays, so that needs to be eliminated. The relative displacement can result from twisting or bending of the antenna structure as a consequence of slewing maneuvers or as the result of thermal gradients. To optimize antenna performance, it is necessary to adjust its static shape using appropriate optimization methods. For large space structures such as mesh antennas, large planar antennas, and large space station solar panels, a frame with several inherent cables is often used. These cables are pre-tensioned in general and are only used to maintain the integrity of structures or improve the rigidity of structures. However, to avoid the need for additional control devices in the structure, these inherent cables are used as actuators in this paper.

The static shape adjustment of the phased arrays can be converted into static shape adjustment of the supporting frame, as the supporting frame and feed panels are connected by suspension hinges. These suspension hinges are somewhat flexible due to the pre-designed clearance, and there is also a clearance between adjacent feed panels. In this way, the feed panels will not participate in resisting deformation when deformation is not too large, so they do not contribute to the stiffness of the antenna. Therefore, successful control of the supporting frame’s deformation will allow for correct adjustment of the feed panels. Hence, the simplified antenna without feed panel arrays is studied in this paper.

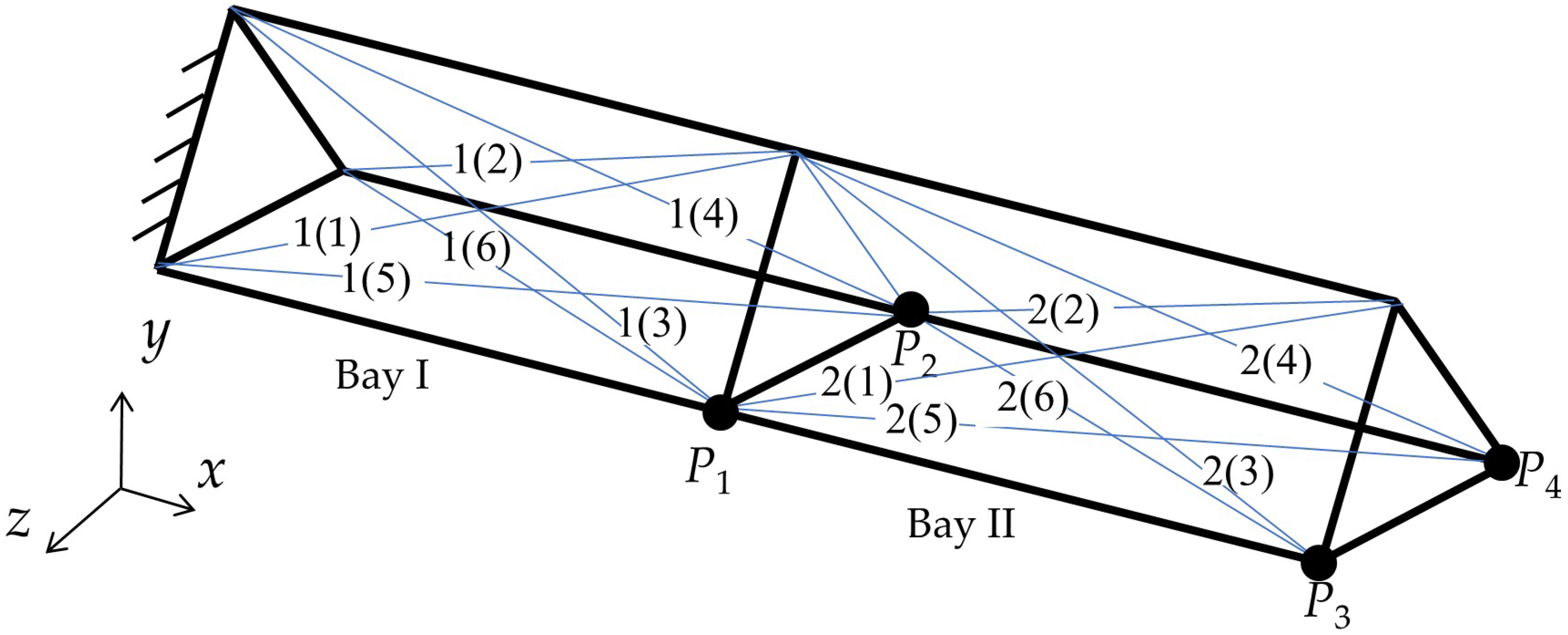

Figure 3 shows a simplified 2-bay antenna with the left end fixed to the satellite and the right end free. There are six diagonal cables in each bay. To ensure clarity in our discussion, we number the diagonal cables in the supporting frame as

p(

q), where

p represents the bay to which the cable belongs, and

q represents the location of the cable. All the locations of cables in each bay are numbered 1~6, as shown in

Figure 3.

3. Structural Modeling

In this section, a phased array antenna with a pre-defined shape is studied. As mentioned earlier, the main load-bearing member of the phased-array antenna is the supporting frame, and the feed panels are not included in our study. This paper uses the FEM to build the antenna’s structural model. Considering the effect of geometrical nonlinearity when the antenna becomes long enough, we establish a nonlinear structural model. This section introduces the nonlinear models for the cable and beam elements.

3.1. Cable Element

As the antenna is used in a gravity-free environment, there is no need to consider the sag effect. The tensioned cable can therefore be modeled as a three-dimensional two-node rod element. In the later parts of this paper, all the tensioned cables are modeled as rod elements, or called cable elements, and are no longer explained. We only consider the geometrical nonlinearity of the cables here. The nonlinear characteristics of the materials are not considered here as we assume that all the cables are made of S.t. Venant-Kirchhoff materials. The theory of the FEM is referenced in textbooks. Suppose there is a two-node cable element with nodes i and j; the nodal displacement vector in the local coordinate system of the element is denoted as . Assuming that the cable element is along the x-axis of its local coordinate system before deformation, the length, cross-sectional area, Young’s modulus, and tension of the cable element are recorded as , , , and , respectively.

According to the theory of FEM, we can build the incremental formulation of the static equilibrium equation for a cable element:

where

is the tangent stiffness matrix of the cable element, and it can be decomposed into three parts: the linear stiffness matrix

, the initial-stress stiffness matrix

, and the initial-displacement stiffness matrix

. On the right-hand side,

and

represent the equivalent external nodal force and the equivalent internal nodal force, respectively.

The specific expressions of these stiffness matrices are given as follows:

where

,

, and

are functions of the nodal displacement, and expressed as follows:

The equivalent external nodal force is determined by the external load of the cable element, and the expression of the internal load is given by

So far, the incremental formulation of the static equilibrium equation for a cable element has been well established.

3.2. Beam Element

Similar to the process of the cable element modeling, we can obtain a nonlinear finite element model of a space beam element, which only considers the geometrical nonlinearity. We assume here that the space beam elements also obey the linearly elastic constitutive law. Suppose there is a two-node space beam element with nodes i and j; then, the nodal displacement vector of the beam element is denoted as .

Assuming that the x-axis direction is the direction in which the unformed beam element is extended, the incremental formulation of the static equilibrium equation can be formulated as

Similar to the incremental formulation of the cable element, is the tangent stiffness matrix of the beam element, and it can also be decomposed into three parts: the linear stiffness matrix , the initial-stress stiffness matrix , and the initial-displacement stiffness matrix . And and represent the equivalent external nodal force and the equivalent internal nodal force, respectively.

The expressions of these stiffness matrices and the equivalent internal nodal force of the beam element are very complicated, so they are not listed here. Readers can refer to the relevant literature to obtain their specific expressions [

23,

24,

25].

So far, the incremental formulation of the static equilibrium equation for a beam element has also been well established.

4. Optimization Method

A reliable optimization method for the precise adjustment of the shape of the antenna structure is presented in this section. When building a structural model, it is crucial to consider geometrical nonlinearity resulting from large structural displacements. In order to achieve shape control, it is necessary to calculate the initial deformation of the antenna structure under external forces first. After discussing the determination of the initial configuration, we elaborate on the specific realization of the optimization method. Using this method to adjust the configuration of the structure can make the actual configuration very close to the objective configuration, thereby ensuring the electrical performance of the antenna.

4.1. Determination of the Initial Configuration

In this section, we explain how to calculate the structural static response under external forces. As the incremental formulation of the static equilibrium equation for cable and beam elements has already been derived, the entire structure’s nonlinear model can be obtained through the element grouping. Herein, we denote the tangent stiffness matrix of the whole antenna structure as

KT(

δ) to show that the tangent stiffness matrix is a function of the global nodal displacement

δ. In a similar way, the equivalent external nodal force and the equivalent internal nodal force are denoted as

and

, respectively. Then, the incremental formulation of the static equilibrium equation of the whole antenna structure can be given by

Equation (8) is a nonlinear equation; here, we use the Newton–Raphson method to solve it. The algorithmic flow is shown below.

Step 1: Set the initial displacement , and set the iteration variable k = 0;

Step 2: Give the iterative formula, and calculate the tangent stiffness matrix

and the displacement increment

:

Step 3: Determine whether the displacement increment meets the convergence requirement. If it is satisfied, the iteration is terminated, and we let the final displacement equal ; otherwise, let k = k + 1 and return to Step 2.

Using the Newton–Raphson method described above, we can determine the antenna’s initial configuration under external forces. Once the initial configuration of the antenna structure is determined, the stresses and strains of every component in the structure can be determined accordingly.

4.2. Optimization Model

In this part, an optimization model for achieving shape adjustment is presented. Clarifying the effect of the cables within the antenna structure, which serve as the actuators, is essential before introducing the optimization method. The cables in the antenna structure can be divided into two categories: active cables, which are involved in structural control as actuators, and passive cables, which act as bearing members and participate in the structural deformation. In fact, in the process of structural control, it is not possible to simply classify a cable into a certain category, because structural control requires the use of many cables as actuators at the same time. Here, we need to point out that unlike the control force defined in mesh antennas, the magnitude of the control force defined in this paper is the actual change in the tension of the active cable during the control process. If the definition of control force is different, the consideration of whether the active cable itself contributes to structural stiffness when it is acting will also be different. Based on the definition of magnitude of control force given above, we find that when a cable is actuated, it does not resist its own action, at which point it belongs to the active cables; however, when the structure is deformed by other actuating cables, the cable acts as a load-bearing member against the deformation of the antenna structure just like other components inherent in the structure, in which case it is a passive cable. This conclusion can be obtained from the viewpoint of a static equivalent. Due to the nature of the cables, we need to introduce some variables:

represents the tangent stiffness matrix of the antenna structure after removing the

i-th cable,

denotes the increment in the control force produced by the

i-th cable,

Qi denotes the transformation matrix between

and the increment in the equivalent finite element control forces caused by it, and

represents the increment in displacement caused by the

i-th cable. In addition, considering the implementation of the algorithm requires several incremental steps, we attach the superscript

r to the above variables to emphasize that these variables must be evaluated in the

r-th incremental step. For example,

denotes the increment in the control force produced by the

i-th cable in the

r-th iteration step. We need to ensure that the increment in the displacement is small in each incremental step so that the tangent stiffness matrix

and the transformation matrix

Qi can be regarded as constant matrices. Then, the following formulas are established:

From Formulas (11) and (12), we can also obtain the remaining similar relationships so that the total displacement increment in the

r-th incremental step can be expressed as

where

n denotes the number of cables,

is the vector of the increment in control forces produced by all cables, and

is the matrix that establishes the relationship between

and

. Based on Equation (13), we can use the optimization method to obtain the final required control forces. The optimization model is discussed in detail below.

4.2.1. Design Variable

This paper utilizes the inherent cables as actuators so that the direction of the control forces will continuously change with the deformation of the structure for geometrical nonlinear problems, which makes it extremely difficult to solve the control forces. In order to account for the change in the direction of the control forces, we divide the solution of the total control forces into several incremental steps and determine the control forces’ directions in each incremental step according to the structural configuration at the beginning of that step. In an incremental step, the control forces’ directions are assumed to be unchanged. As long as the displacement increment of each step is small enough, this assumption is reasonable.

For each incremental step, we can apply a common optimization model to obtain the optimal incremental control forces, and then the final control forces can be obtained by accumulating the incremental control forces in all steps. So, in the optimization model, the incremental control forces are selected as the design variables and expressed as

where

n is the number of cables and

is the control force of the

i-th cable.

4.2.2. Objective Function

For many different kinds of antennas, an important indicator called displacement root mean square (RMS) is always used to evaluate the shape accuracy of the antenna. The antenna’s RMS can be defined by the displacement of antenna nodes relative to their designed position, the expression of which is as follows:

where

is the absolute value of the displacement of the

i-th node,

N is the number of nodes, and the expression of

is

where

,

, and

are the displacements of the

i-th node along the

x-axis,

y-axis, and

z-axis, respectively. If the RMS is very small, it means that all nodes are very close to their designed positions, so the RMS can be used to evaluate the deviation of the actual configuration of the antenna from its objective configuration.

To simplify the calculation, we introduce a new objective function defined as

where

δ is the global nodal displacement vector. From Equations (15) and (17), we can obtain the relationship between the RMS and

J, that is,

From the above equation, we can see that the objective function can also evaluate the deviation of the actual configuration of the antenna from the objective configuration. If δ is a zero vector, it means that all nodes are in their ideal positions; at this time, J and RMS are both equal to 0.

4.2.3. Constraints

The constraints can be expressed as follows:

where

is the incremental displacement in an increment step; a reasonable value of e guarantees that the displacement increment in each incremental step is small. In Equation (20),

is the total control force vector and

is the vector reflecting the upper limit of the total control force vector.

4.2.4. Optimization Model in an Incremental Step

According to Relation (13) and the above constraints, the optimization model in the

r-th step can be summarized as

In this paper, the genetic algorithm is used to solve this optimization problem.

Then, the algorithm flow to solve the total control force vector can be given as follows.

Step 1: Set the initial displacement and set the increment variable r = 0.

Step 2: Give the incremental formula and calculate

and the displacement increment

.

Step 3: Determine whether the objective function J meets the convergence requirement . If it is satisfied, the algorithm is terminated and the final vector of control forces equals ; otherwise, let r = r + 1 and return to Step 2.

According to the above algorithm, as long as we set reasonable e and Je, we can obtain the vector of control forces that meets the control requirements. So far, we have completely established the control model and we will use it in the following simulations.

5. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we investigate a simplified 2-bay antenna and an 18-bay antenna to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method. We can easily establish the linear structural model and nonlinear structural model of the simplified 2-bay antenna. By comparing the simulation results of these two models under the same external loads, the validity of the proposed method can be ensured. When the loads are not large, the results of the two models should be close. The simplified 18-bay antenna is even more worth studying. That is because as the structure size increases, a small load may also cause a sufficient displacement, which will reflect the geometric nonlinearity of the structure. The left ends of both the 2-bay antenna and the 18-bay antenna are fixed to the satellite, and their right ends are free. The parameters of longerons and battens are given in

Table 1. The algorithms were all implemented using MATLAB 2022b, running on a 64-bit Windows 11 personal computer with an AMD Ryzen 7 5800 8-Core 3.40 GHz processor and 32 GB RAM. It is necessary to clearly point out that the linear model calculation results presented in this paper are all derived from reference [

26].

The antenna structure can be modeled by several finite elements. The number of elements in each bay is as follows: the number of elements of the longeron is 30, and that of the batten is 10.

5.1. 2-Bay Antenna

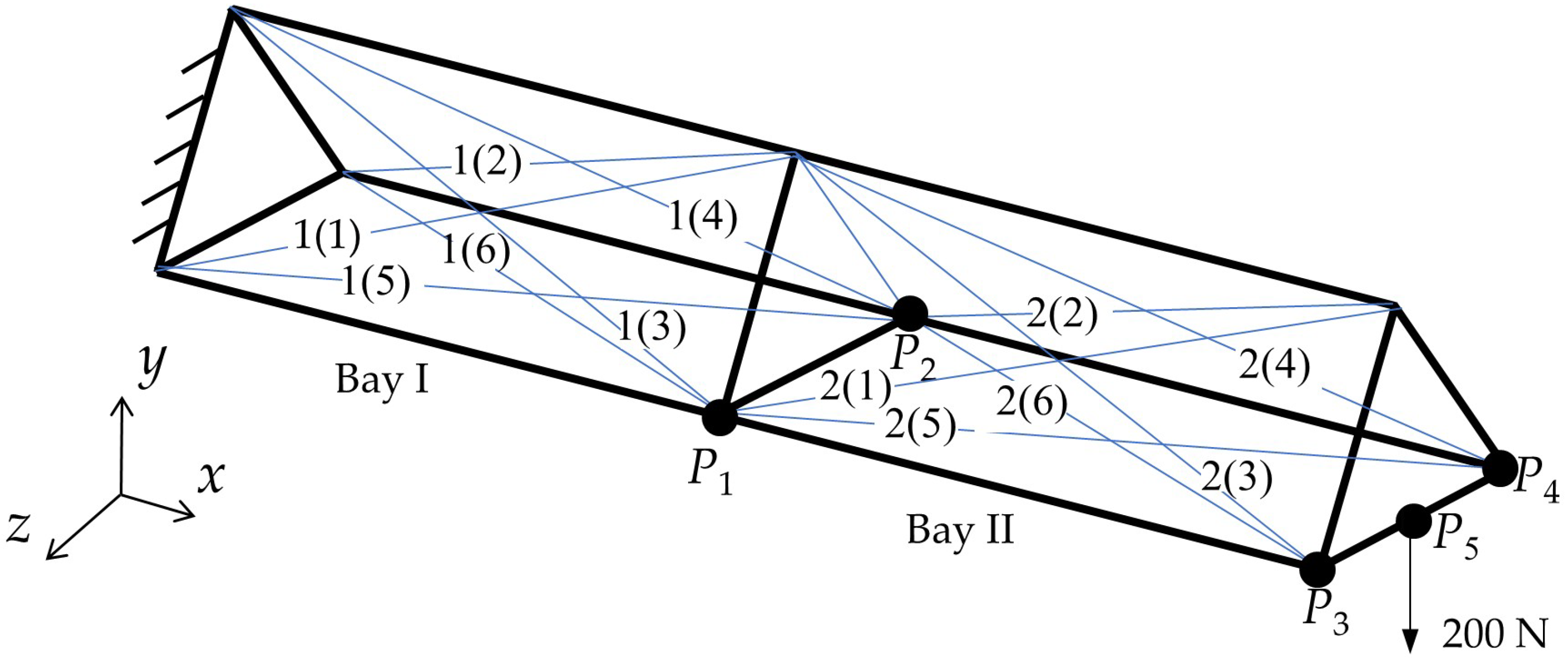

To verify the proposed adjustment method, we first studied the simplified 2-bay antenna. Then, we established both a linear and a nonlinear structural model for the antenna. When the displacements of all the nodes are not too large, the nonlinearity of the structure will be less obvious, so the results of these two models would be similar. If the results of the linear model are in agreement with those of the nonlinear model, then we can conclude with confidence that the optimization method can be successfully applied to static shape control of the 18-bay antenna. In our simulation, there is an external force of 200 N in the negative direction of the

y-axis applied to the node

P5 to generate the initial displacements.

Figure 4 shows that

P5 is the midpoint of

P3 and

P4.

The initial displacements of

P1~

P4 calculated by the linear and nonlinear models are shown in

Table 2.

From the symmetry of structure and load, we find that the displacements of nodes

P1~

P4 are symmetrical, which can also be concluded from

Table 2. Actually, according to the theory of structural mechanics, bending deformation occurs in the

x-

y plane, so the results in

Table 2 are reliable. Comparing the results of linear and nonlinear models, we can conclude that the displacements of the nonlinear model and the linear model are close to each other when the external loads are not so large. On the other hand, compared to the displacements of the linear model, those of the nonlinear model are smaller.

For the linear and nonlinear models, corresponding linear and nonlinear optimization methods are performed. The problem constraints are listed as follows:

(1) The upper limit of the displacement of the nodes is set to 0.2 mm;

(2) The control forces of actuators in the linear model must lie between 0 and 260 N;

(3) The control forces of actuators in the nonlinear model must lie between 0 and 270 N.

The reason why we choose different force limits is that the upper limit of 260 N has no solution for nonlinear conditions.

Table 3 shows the control forces of these two methods.

Table 3 demonstrates the almost symmetrical control forces generated by diagonal cables in both linear and nonlinear models, specifically in cables 1(3) and 1(4) about the

x-

y plane. The result is logical because of the symmetries of the structure and the applied loads. From

Table 3, we can also find that some cables have far greater control forces than others, such as the cables 1(3), 1(4), 2(3), and 2(4). This result may indicate that some cables are indispensable for controlling certain structural deformations. In addition, we note that for cables with small control forces such as 1(1) and 1(2), the percentage difference between linear and nonlinear control forces is significant. We attribute this phenomenon primarily to numerical computation considerations. In this study, the genetic algorithm was employed for optimization; to enhance computational efficiency, the algorithm accepted feasible solutions within the expected accuracy rather than pursuing the global optimum. For cables with minimal control forces, their contribution to structural deformation is negligible. Consequently, although the percentage difference between their linear and nonlinear control forces may appear large, the algorithm converged early to a feasible—rather than strictly optimal—solution, as the impact on overall structural behavior remains within acceptable limits.

Comparing the results of linear and nonlinear models, we can find that nonlinear model tends to have greater control forces than the linear model. This phenomenon can reflect that the nonlinear model exhibits greater stiffness than the linear model under the same external load.

Table 2 and

Table 3 demonstrate that the initial deformation and control forces are comparable in both linear and nonlinear models for small deformation. We can also conclude that the method proposed in this paper for statically adjusting the shape of the antenna is correct. In addition, it should be noted that, under ideal conditions, the control forces of some cables should strictly equal 0. However, the genetic algorithm may not always provide the global optimum, so the control forces of some cables are not strictly equal to 0.

5.2. 18-Bay Antenna

The correctness of the nonlinear finite element model and the corresponding optimization method proposed in this paper has been demonstrated in the above section. So, we can study the 18-bay antenna in the same way. An external force of 45 N in the negative direction of the y-axis is applied to the midpoint of the right end of the simplified 18-bay antenna. The 18-bay antenna is shown in

Figure 5.

In a similar fashion, the problem constraints include the following:

(1) The upper limit of the displacement of the nodes is set to 10 mm;

(2) The control forces of actuators in the linear model must lie between 0 and 100 N;

(3) The control forces of actuators in the nonlinear model must lie between 0 and 160 N.

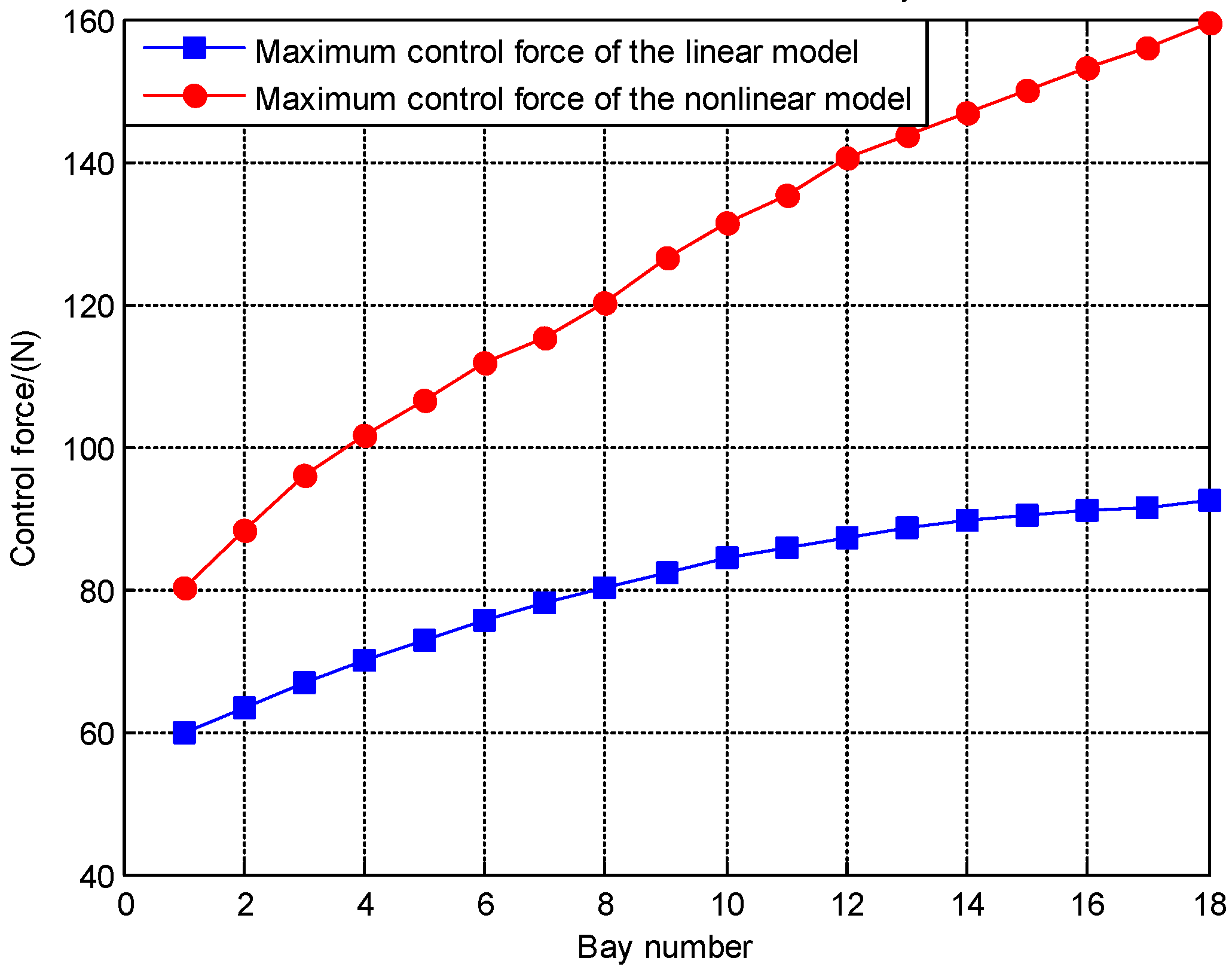

The upper displacement limit for the 18-bay antenna has been increased from 0.2 mm to 10 mm, which is a significant improvement from the 2-bay antenna case. This is due to the greater difficulty in controlling the larger antenna, which we have successfully overcome. The simplified 18-bay antenna has a total of 108 diagonal cables. Listing all the control forces for each cable can be challenging. Therefore,

Figure 6 shows the maximum control forces of the linear and nonlinear model in each bay. From

Figure 6, we can see that, corresponding to the external force of 45 N, the maximum control forces are a manageable size so that they can be accepted.

Figure 6 shows that the maximum control force of the nonlinear model is significantly greater than that of the linear model. This phenomenon is different from the case of a 2-bay antenna. The reason is that geometrical nonlinearity is more pronounced as the size of the structure increases. So, when the size of the structure becomes larger, the linear model will give inaccurate results.

Similarly, comparing linear and nonlinear models before and after control can also yield meaningful conclusions.

Table 4 gives the results of the two control models.

It can be seen from

Table 4 that before control, the maximum displacement of the linear model is greater than the displacement of the nonlinear model when subjected to the same load. In addition, after control, both of them achieved the expected accuracy.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a nonlinear finite element model and a corresponding nonlinear control model for static shape adjustment of the supporting frame are proposed and followed by verifications of the simplified 2-bay and 18-bay satellite antennas. This optimization method uses diagonal cables as the actuators to avoid adding redundant control devices. Therefore, it can not only improve the reliability of the antenna but also reduce the mass of the whole antenna structure. However, there are two major difficulties in using this method. The first difficulty stems from the increase in structural size. As the size of the structure increases, the linear finite element model cannot accurately describe the mechanical properties of the antenna structure. Thus, the geometrical nonlinearity must be considered to establish a nonlinear finite element model. Another difficulty stems from the different effects of cables on structural static response and structural control. When the structure is loaded, the inherent cables behave as load-bearing members, but when they act as actuators, they do not resist their own actions. In other words, when a cable is actuated, it does not resist its own action, so this cable does not contribute to the overall stiffness of the structure, while other cables should be treated as passive members to resist deformation. To overcome the first difficulty, we use the nonlinear finite element method to establish more accurate nonlinear beam elements and cable elements. As for the second difficulty, a nonlinear optimization method is designed, and the final control law is obtained by several incremental steps. After establishing a nonlinear finite element model and a nonlinear optimization method, a simplified 2-bay and a simplified 18-bay antenna supporting frame are studied. The results show that the geometrical nonlinearity is not obvious when the structure size is small, but when the structure size becomes large, the geometrical nonlinearity will greatly affect the mechanical properties of the structure. In the simulation of the 18-bay antenna, it can be seen that for the large-size antenna supporting frame, the initial displacements of the structure calculated by the nonlinear model are significantly smaller than the initial displacements calculated by the linear model. In addition, the control forces required for the nonlinear model are also significantly greater than the control forces required for the linear model. This is because when considering geometrical nonlinearity, the stiffness matrix of the structure is a function of the structural displacement, and the additional stiffness due to geometrical nonlinearity will increase as the structural displacement increases.