Fast Electrical Activation of Shape Memory Alloy Spring Actuators: Sub-Second Response Characterization and Performance Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

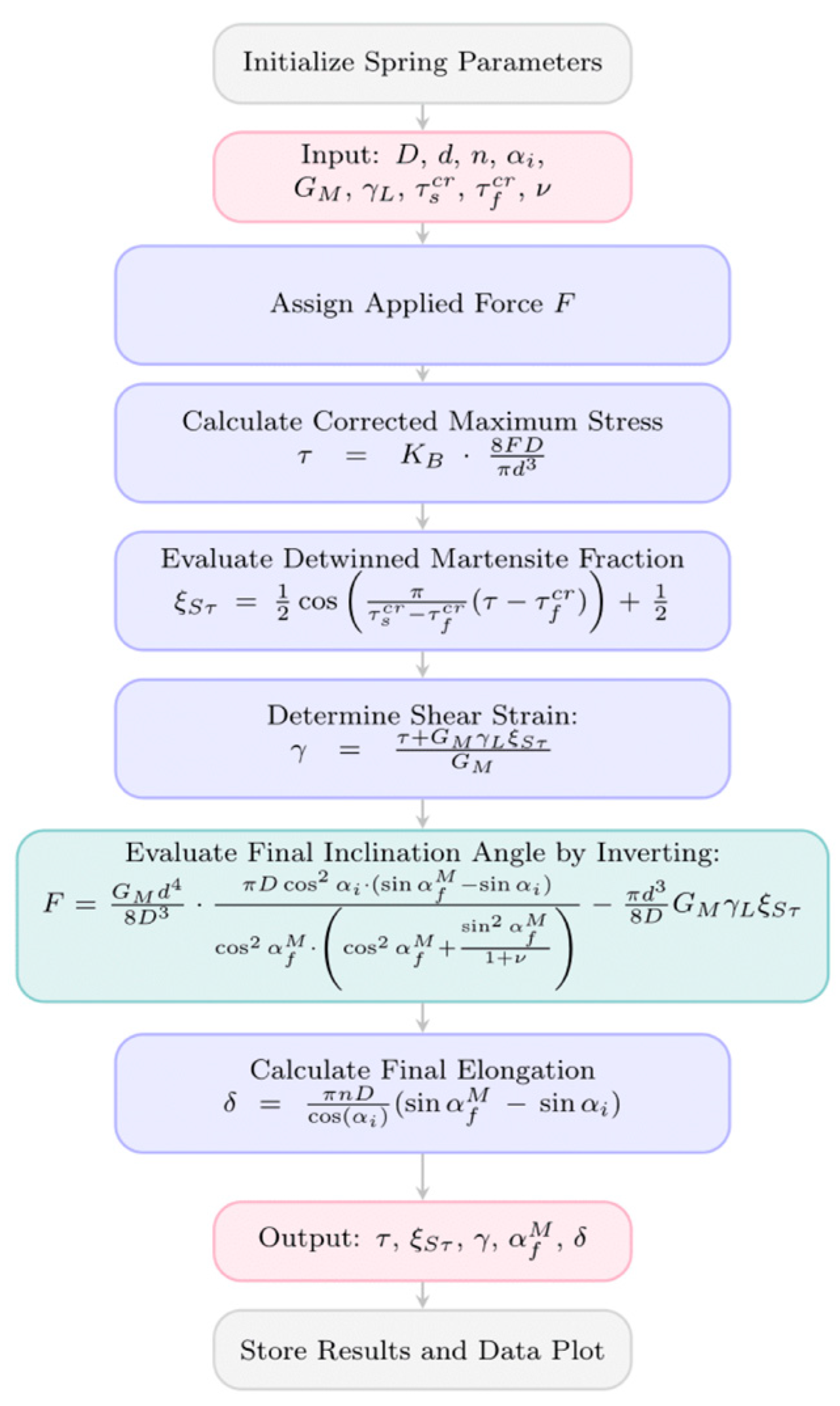

2. Materials and Methods

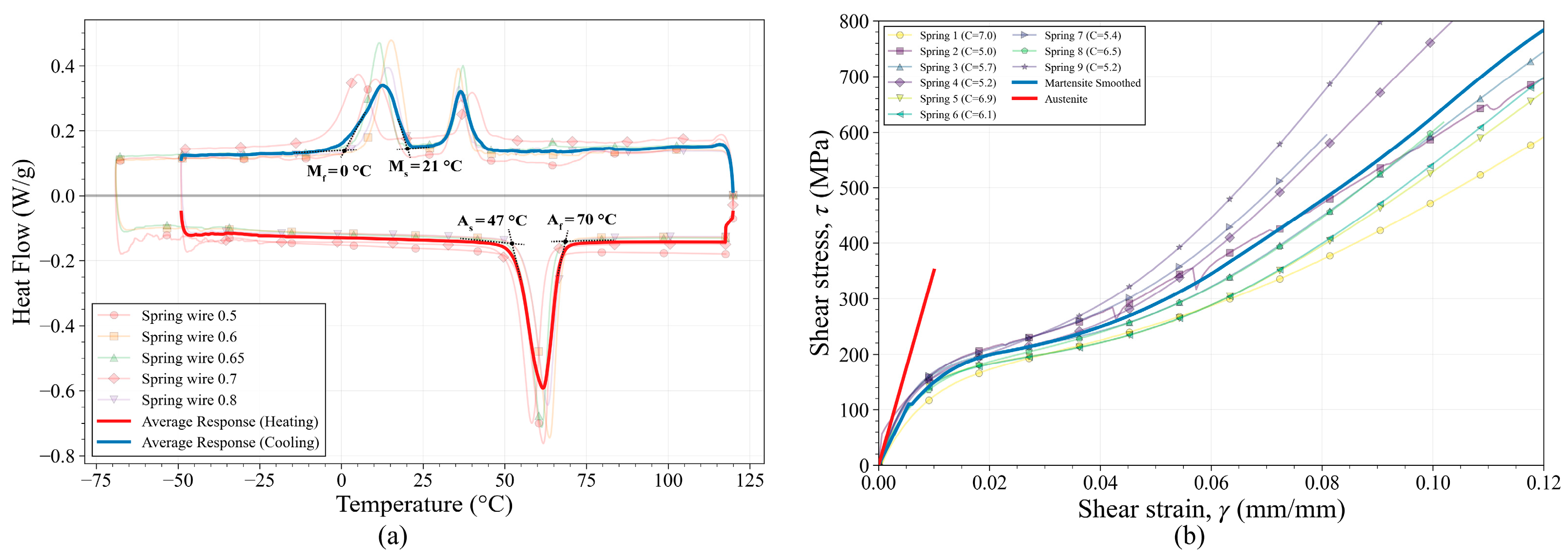

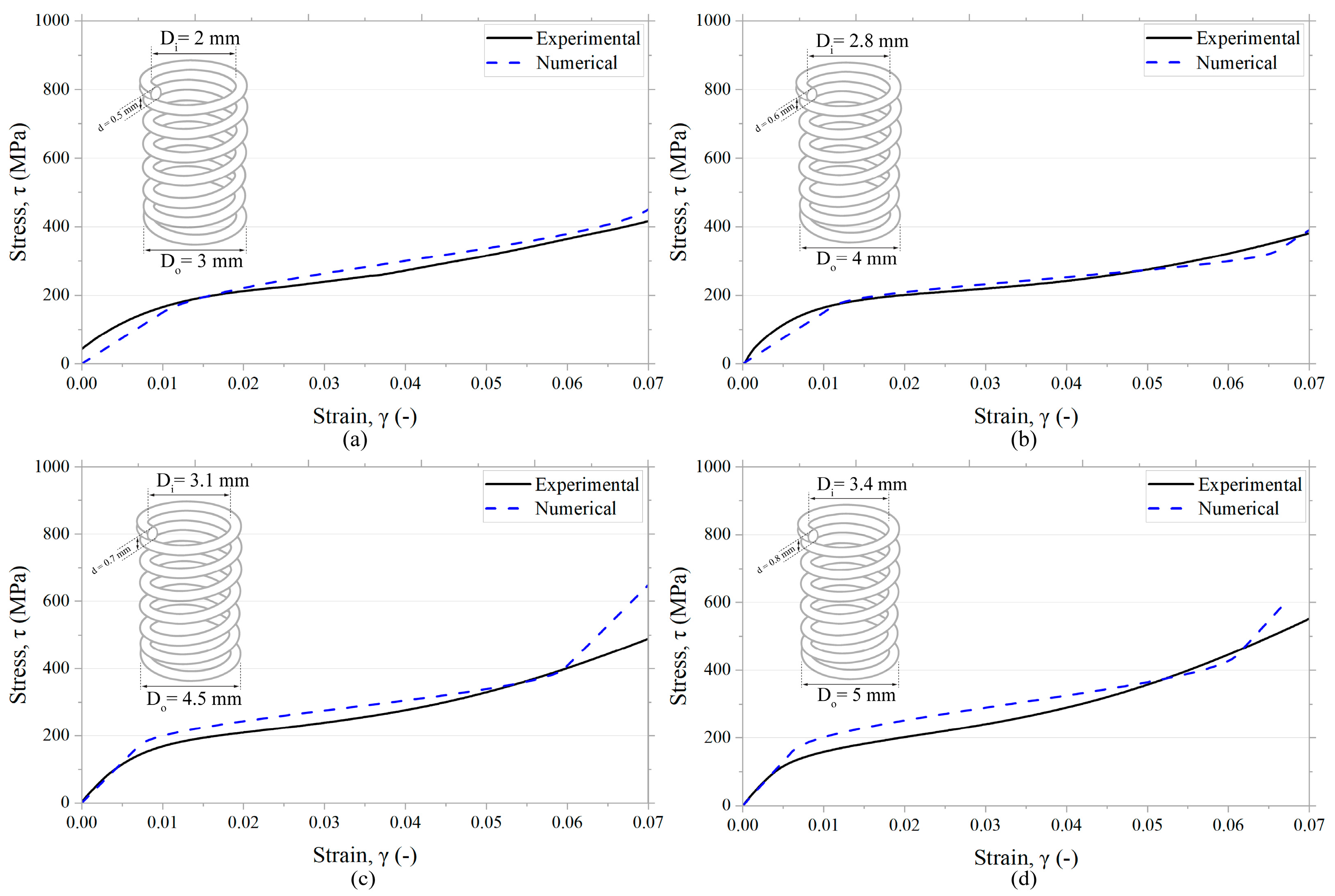

2.1. SMA Springs’ Geometry and Material

2.2. Fast Activation: Experimental Design and Methodology

2.2.1. Advanced Characterization Setup and Instrumentation

- High-precision load cell (HBM (Milano, Italy) U9C, 1kN capacity) for force measurement;

- Non-contact laser displacement sensor (Micro-Epsilon (Porto Mantovano, Italy) optoNCDT-1220) with micrometer resolution;

- Infrared thermal camera (Teledyne FLIR (Wilsonville, OR, USA) A615) for real-time temperature monitoring;

- Programmable power supply (Aim-TTi (Huntingdon, UK) CPX400DP) for controlled electrical activation;

- Data acquisition system (HBM (Milano, Italy) QuantumX 840A) for synchronized data collection.

2.2.2. Systematic Stress Level Selection Framework

3. Results and Discussion

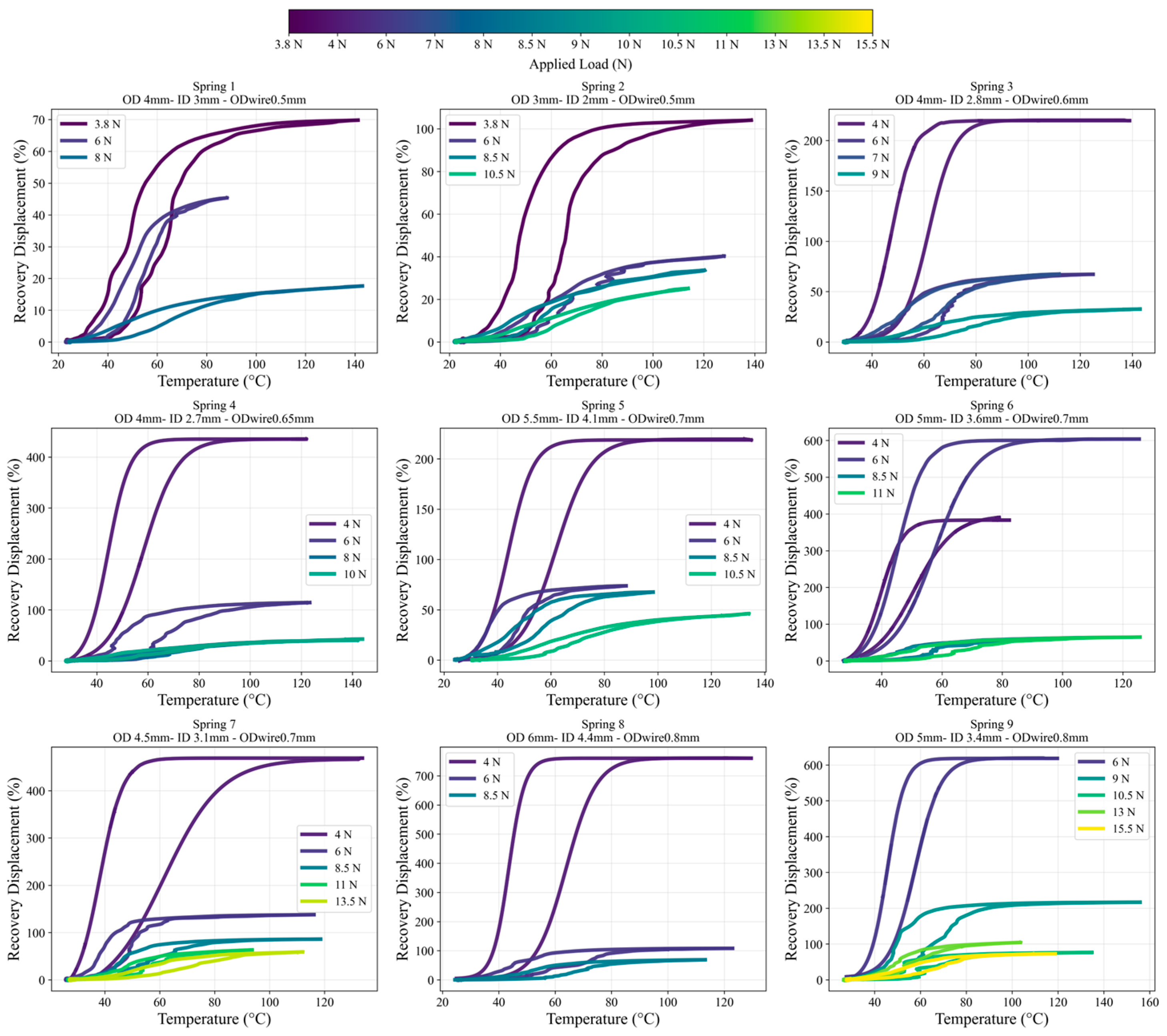

3.1. Constant Stress Recovery Static Behavior

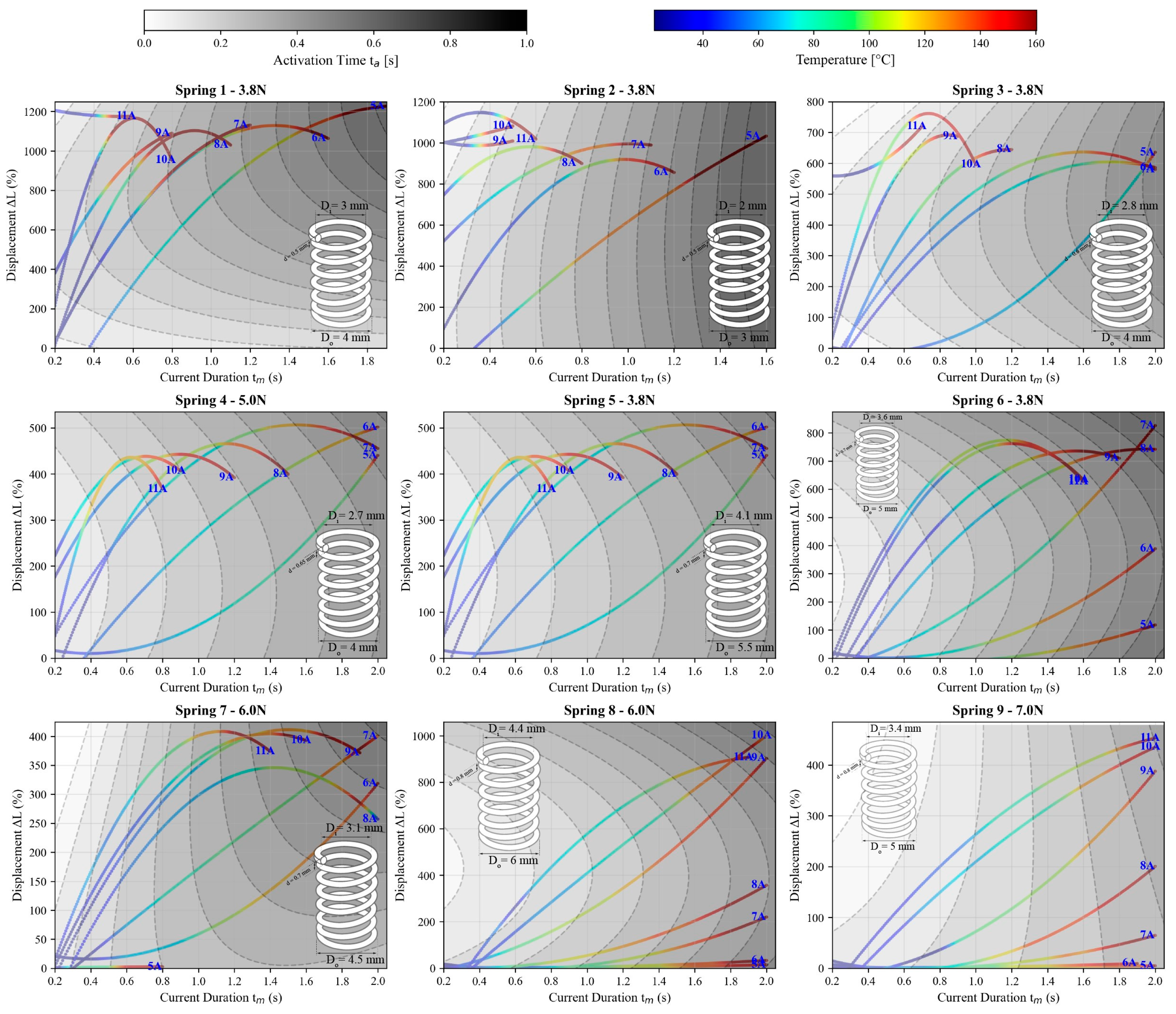

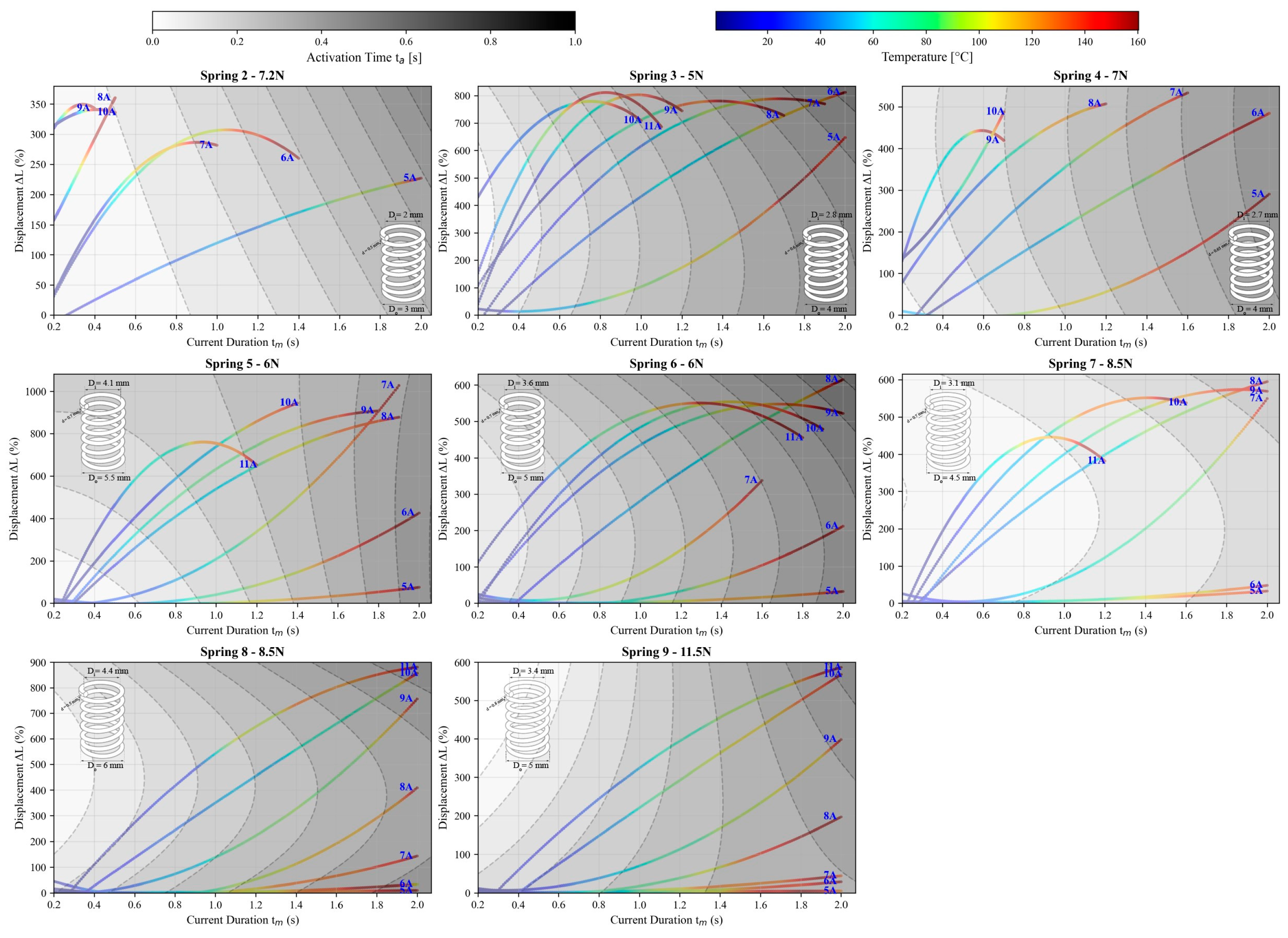

3.2. Constant Stress Recovery—Dynamic Actuation Performance

- Electrical Resistance: R ∝ 1/d2, requiring quadratically higher current for equivalent power input in thinner wires.

- Thermal Mass: Heat capacity ∝ d2, meaning thinner wires heat and cool more rapidly.

- Surface Area to Volume Ratio: (A/V) ∝ 1/d, enhancing convective cooling in thin wires.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lagoudas, D.C. Shape Memory Alloys: Modeling and Engineering Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, L.; Wayman, C.M. Shape Memory Materials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Giovinco, V.; Kotak, P.; Cichella, V.; Maletta, C.; Lamuta, C. Dynamic model for the tensile actuation of thermally and electro-thermally actuated twisted and coiled artificial muscles (TCAMs). Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Jani, J.; Leary, M.; Subic, A.; Gibson, M.A. A review of shape memory alloy research, applications and opportunities. Mater. Des. 2014, 56, 1078–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, D.J.; Lagoudas, D.C. Aerospace applications of shape memory alloys. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2007, 221, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.P.; Hwang, K.C. Micromechanics modelling for the constitutive behavior of polycrystalline shape memory alloys—I. Derivation of general relations. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1993, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemov, A.; Saren, A. 3-D Meso-Scale Finite Element Calculations of Free Energy on Twin Boundaries in Magnetic Shape Memory Alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2024, 60, 2000712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisse, C.; Zaki, W.; Ben Zineb, T. A review of constitutive models and modeling techniques for shape memory alloys. Int. J. Plast. 2016, 76, 244–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambitterra, E.; Maletta, C.; Furgiuele, F. Investigation on Crack Tip Transformation in NiTi Alloys: Effect of the Temperature. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2015, 1, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarino, S.; Flores, E.S.; Ajaj, R.M.; Friswell, M.I.; Dayyani, I. A review on shape memory alloys with applications to morphing aircraft. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. On the selection of shape memory alloys for actuators. Mater. Des. 2002, 23, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambitterra, E.; Maletta, C.; Furgiuele, F. Modeling and simulation of the thermo-mechanical response of NiTi-based Belleville springs. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2016, 27, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahinia, M.H.; Hashemi, M.; Tabesh, M.; Borghesani, S.B. Manufacturing and processing of NiTi implants: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2012, 57, 911–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, J.M.; Huang, S.; Leary, M. Numerical modeling of shape memory alloy linear actuator. Comput. Mech. 2014, 53, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andianesis, K.; Tzes, A. Design of an anthropomorphic prosthetic hand driven by Shape Memory Alloy actuators. In Proceedings of the 2008 2nd IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 19–22 October 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Q.A.; Wan Hasan, W.Z.; Azmah Hanim, M.A.; Nuraini, A.A.; Hamidon, M.N.; Ramli, H.R. Shape memory alloys actuated upper limb devices: A review. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2023, 5, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerig, T.; Pelton, A.; Stöckel, D. An overview of nitinol medical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 273, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecce, L.; Concilio, A. Shape Memory Alloy Engineering: For Aerospace, Structural and Biomedical Applications; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla Navarro, P.; Copaci, D.; Arias, J.; Blanc Rojas, D. Design of an SMA-Based Actuator for Replicating Normal Gait Patterns in Pediatric Patients with Cerebral Palsy. Biometrics 2024, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Cui, J.; Nawarathne, D.D. Magnetic Field Sensing with Magnetic Shape Memory Alloy and Fiber Bragg Grating on Silica and Polymer Optical Fibers. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 7007008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodinò, S.; Curcio, E.M.; Sgambitterra, E.; Maletta, C. SMA-Polymer Composite Made by 3D Printing: Modelling and Experiments. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 47, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S. Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) Actuators: The Role of Material, Form, and Scaling Effects. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.; Srinivasa, A.R.; Reddy, J.N. Design of Shape Memory Alloy (SMA) Actuators, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.L.; Pino, L.; Barati, M.; Saint-Sulpice, L.; Daniel, L.; Chirani, S.A. Modeling of functional fatigue of SMA-based actuators under thermomechanical loading and Joule heating. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 179, 108055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpueyo, D.; Balandraud, X.; Grédiac, M. Applying full-field measurement techniques for the thermomechanical characterization of shape memory alloys. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Nie, L.; Zhang, X. Finite-Iteration Learning Tracking Control of Magnetic Shape Memory Alloy Actuator Based on Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, N.; Soni, S.; Singla, A. Analyzing the effect of parametric variations on the performance of antagonistic SMA spring actuator. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 31, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H. Simulation of Shape Memory Alloy (SMA)-Bias Spring Actuation for Self-Shaping Architecture. Materials 2020, 13, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodinò, S.; Caroleo, G.; Sgambitterra, E.; Bruno, F.; Muzzupappa, M.; Maletta, C. A multiphysics dynamic model for shape memory alloy actuators. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2023, 362, 114602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambitterra, E.; Greco, C.; Rodinò, S.; Niccoli, F.; Furgiuele, F.; Maletta, C. Fully coupled electric-thermo-mechanical model for predicting the response of a SMA wire activated by electrical input. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2023, 362, 114643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, S.; Abang Haji Abdul Majid, D.L.; Jaafar, C.; Ismail, M.; Yahya, H. Heating Techniques of Shape Memory Alloy (SMA)—A Review. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2022, 78, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, R.; Bucht, A.; Pagel, K.; Jung, J. Numerical Simulation of the Activation Behavior of Thermal Shape Memory Alloys; Fraunhofer IWU: Chemnitz, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shayanfard, P.; Kadkhodaei, M.; Jalalpour, A. Numerical and Experimental Investigation on Electro-Thermo-Mechanical Behavior of NiTi Shape Memory Alloy Wires. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 2019, 43, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollach, S.; Shilo, D. The Mechanical Response of Shape Memory Alloys Under a Rapid Heating Pulse. Exp. Mech. 2010, 50, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollach, S.; Shilo, D.; Shlagman, H. Mechanical Response of Shape Memory Alloys Under a Rapid Heating Pulse—Part II. Exp. Mech. 2016, 56, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzki, P.; Gorges, T.; Kappel, M.; Schmidt, M.; Rizzello, G.; Seelecke, S. High-Speed and High-Efficiency Shape Memory Alloy Actuation. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 075047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, A.; Vollach, S.; Shilo, D. Use the Force: Review of High-Rate Actuation of Shape Memory Alloys. Actuators 2021, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ke, Y.; Qiu, S. Actuation response of typical biased shape memory alloy wire under variable electric heating rates: Experimental investigation and modeling. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2022, 33, 2258–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, H.; Golestanian, H.; Zakerzadeh, M.R.; Homaei, H. Thermoelectric heat transfer modeling of shape memory alloy actuators. In Proceedings of the 22st Annual International Conference on Mechanical Engineering-ISME2014, Ahvaz, Iran, 22 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nizamani, A.M.; Daudpoto, J.; Nizaman, M.A. Development of Faster SMA Actuators; InTech Open: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Motzki, P. Efficient SMA Actuation—Design and Control Concepts. Proceedings 2020, 64, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zu, X.; Feng, X.; Dai, J. Effect of thermomechanical treatment on the two-way shape memory effect of NiTi alloy spring. Mater. Lett. 2002, 54, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Zu, X.T.; Feng, X.D.; Zhu, S.; Deng, J.; Wang, L.M. Effect of electrothermal annealing on the transformation behavior of TiNi shape memory alloy and two-way shape memory spring actuated by direct electrical current. Phys. B 2004, 349, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Zu, X.T.; Feng, X.D.; Zhu, S.; Bao, J.W.; Wang, L.M. Characteristics of two-way shape memory TiNi springs driven by electrical current. Mater. Des. 2004, 25, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.M.; Ryu, J.; Cho, M.; Cho, K.J. Engineering design framework for a shape memory alloy coil spring actuator using a static two-state model. Smart Mater. Struct. 2012, 21, 055009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.B.; Keith, N.J. Shigley: Progetto e Costruzione di Macchine; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brinson, L.C. One-dimensional constitutive behavior of shape memory alloys: Thermomechanical derivation with non-constant material functions and redefined martensite internal variable. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 1993, 4, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spring | Dext [mm] | Dint [mm] | d [mm] | Length [mm] | Spring Index | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.0 * | 3.0 | 0.5 | 105 | 8.00 |  |

| 2 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 105 | 6.00 |  |

| 3 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 102 | 6.67 |  |

| 4 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 0.65 | 103 | 6.15 |  |

| 5 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 104 | 7.86 |  |

| 6 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 104 | 7.14 |  |

| 7 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 103 | 6.43 |  |

| 8 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 110 | 7.50 |  |

| 9 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 102 | 6.25 |  |

| Spring Type | GA [MPa] | GM [MPa] | γL | Spring Index (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39.0 | 14.0 | 0.043 | 8.00 |

| 2 | 31.0 | 15.0 | 0.040 | 6.00 |

| 3 | 36.0 | 15.0 | 0.044 | 6.67 |

| 4 | 35.0 | 22.0 | 0.040 | 6.15 |

| 5 | 32.0 | 17.0 | 0.047 | 7.86 |

| 6 | 37.0 | 22.0 | 0.046 | 7.14 |

| 7 | 30.0 | 24.0 | 0.043 | 6.43 |

| 8 | 35.0 | 24.0 | 0.044 | 7.50 |

| 9 | 32.0 | 26.0 | 0.044 | 6.25 |

| Average | 32.1 | 19.6 | 0.0434 | 6.89 |

| Spring Type | Load [N] | % Detwinned Martensite |

|---|---|---|

| 1 * | 3.8 | 100 |

| 2 | 3.8 | 50 |

| 2 | 7.2 | 100 |

| 3 | 3.8 | 50 |

| 3 | 5.0 | 100 |

| 4 | 5.0 | 50 |

| 4 | 7.0 | 100 |

| 5 | 3.8 | 50 |

| 5 | 6.0 | 100 |

| 6 | 3.8 | 50 |

| 6 | 6.0 | 100 |

| 7 | 6.0 | 50 |

| 7 | 8.5 | 100 |

| 8 | 6.0 | 50 |

| 8 | 8.5 | 100 |

| 9 | 7.0 | 50 |

| 9 | 11.5 | 100 |

| Spring Type | Load [N] | 5 A | 6 A | 7 A | 8 A | 9 A | 10 A | 11 A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2 | 3.8 7.2 | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ |

| 3 | 3.8 5 | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | |||

| 4 | 5 7 | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ||

| 5 | 3.8 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | |||

| 6 | 3.8 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ||||

| 7 | 6 8.5 | ✓ ✓ | ||||||

| 8 | 6 8.5 | ✓ | ||||||

| 9 | 7 11.5 | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodinò, S.; Chiodo, M.; Corigliano, A.; Rota, G.; Maletta, C. Fast Electrical Activation of Shape Memory Alloy Spring Actuators: Sub-Second Response Characterization and Performance Optimization. Actuators 2025, 14, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120584

Rodinò S, Chiodo M, Corigliano A, Rota G, Maletta C. Fast Electrical Activation of Shape Memory Alloy Spring Actuators: Sub-Second Response Characterization and Performance Optimization. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120584

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodinò, Stefano, Matteo Chiodo, Antonio Corigliano, Giuseppe Rota, and Carmine Maletta. 2025. "Fast Electrical Activation of Shape Memory Alloy Spring Actuators: Sub-Second Response Characterization and Performance Optimization" Actuators 14, no. 12: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120584

APA StyleRodinò, S., Chiodo, M., Corigliano, A., Rota, G., & Maletta, C. (2025). Fast Electrical Activation of Shape Memory Alloy Spring Actuators: Sub-Second Response Characterization and Performance Optimization. Actuators, 14(12), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120584