Soft MRE Gripper: Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

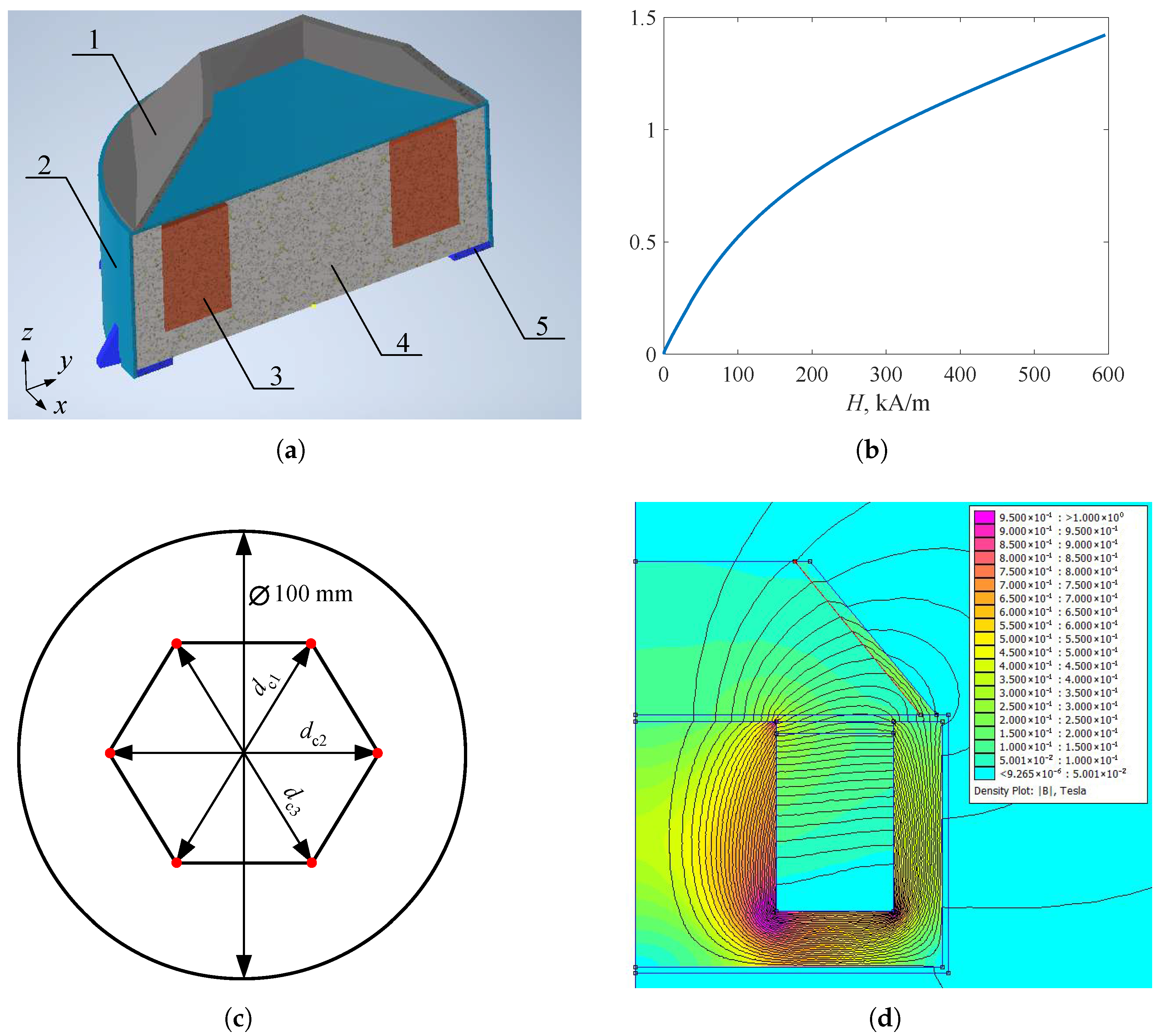

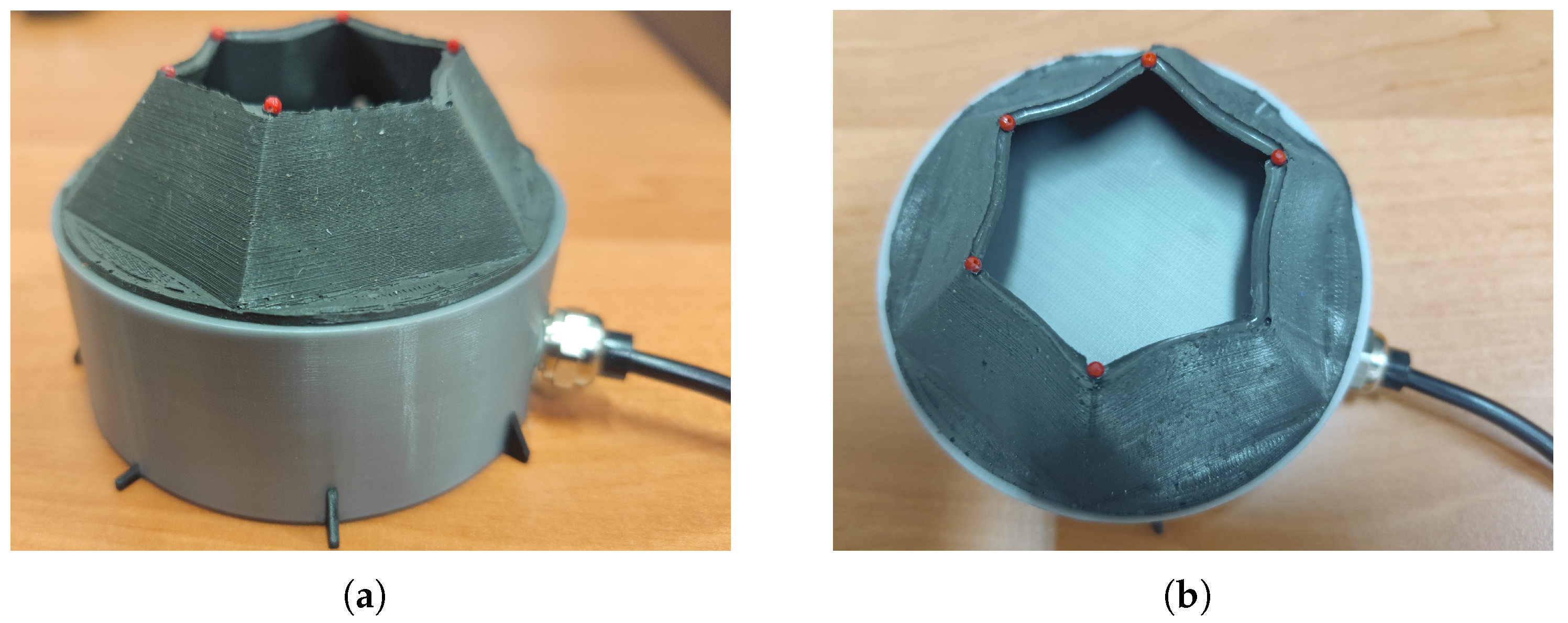

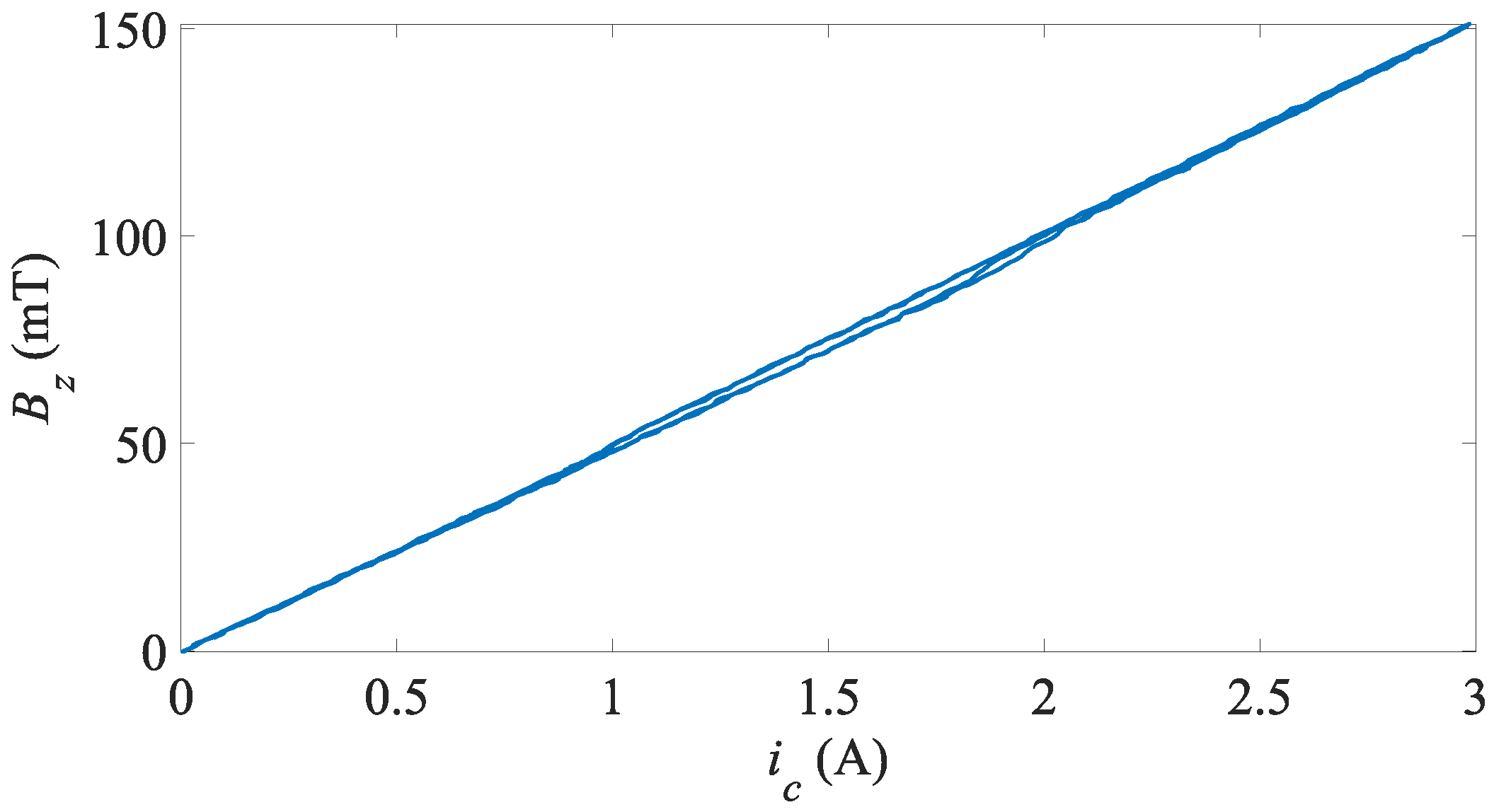

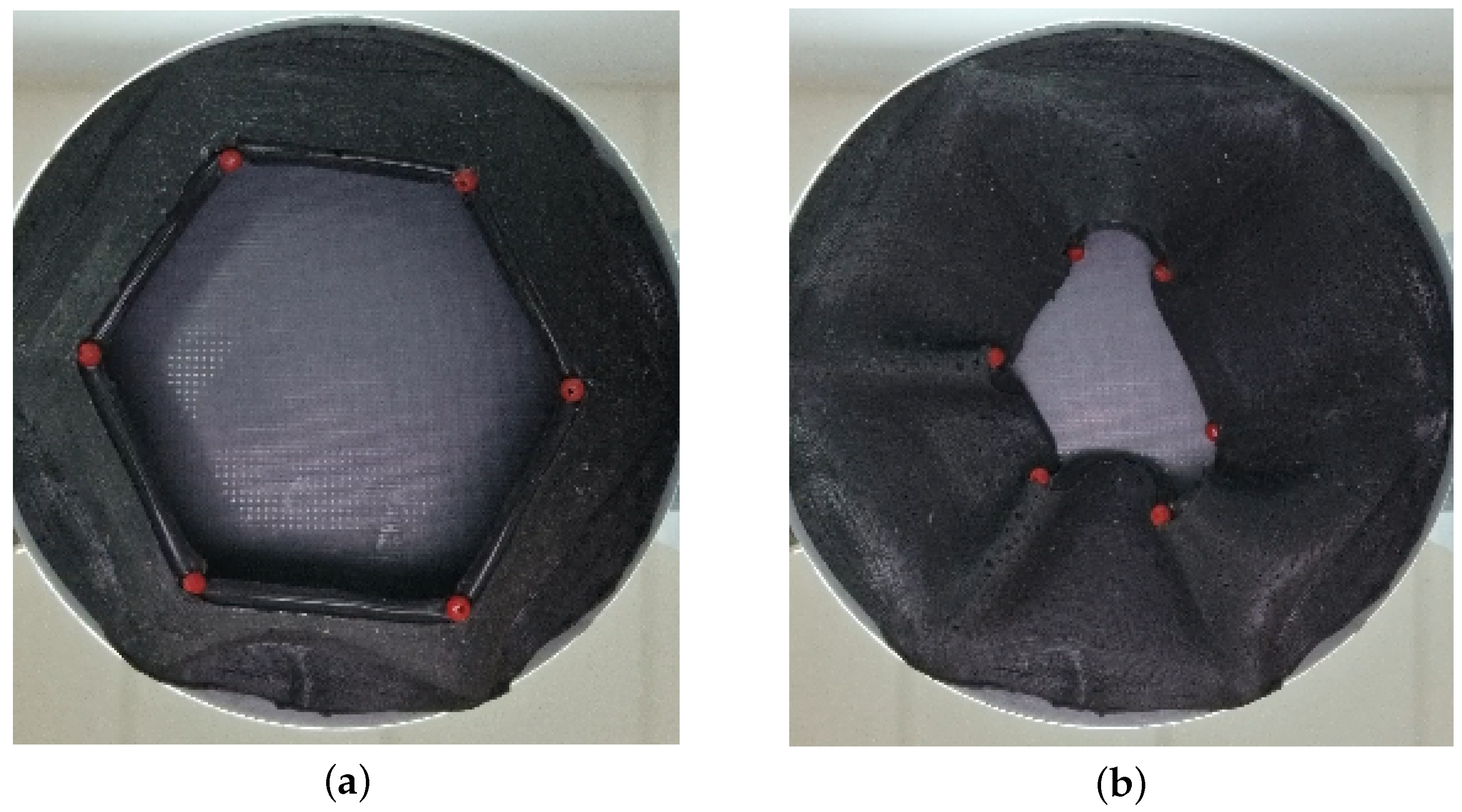

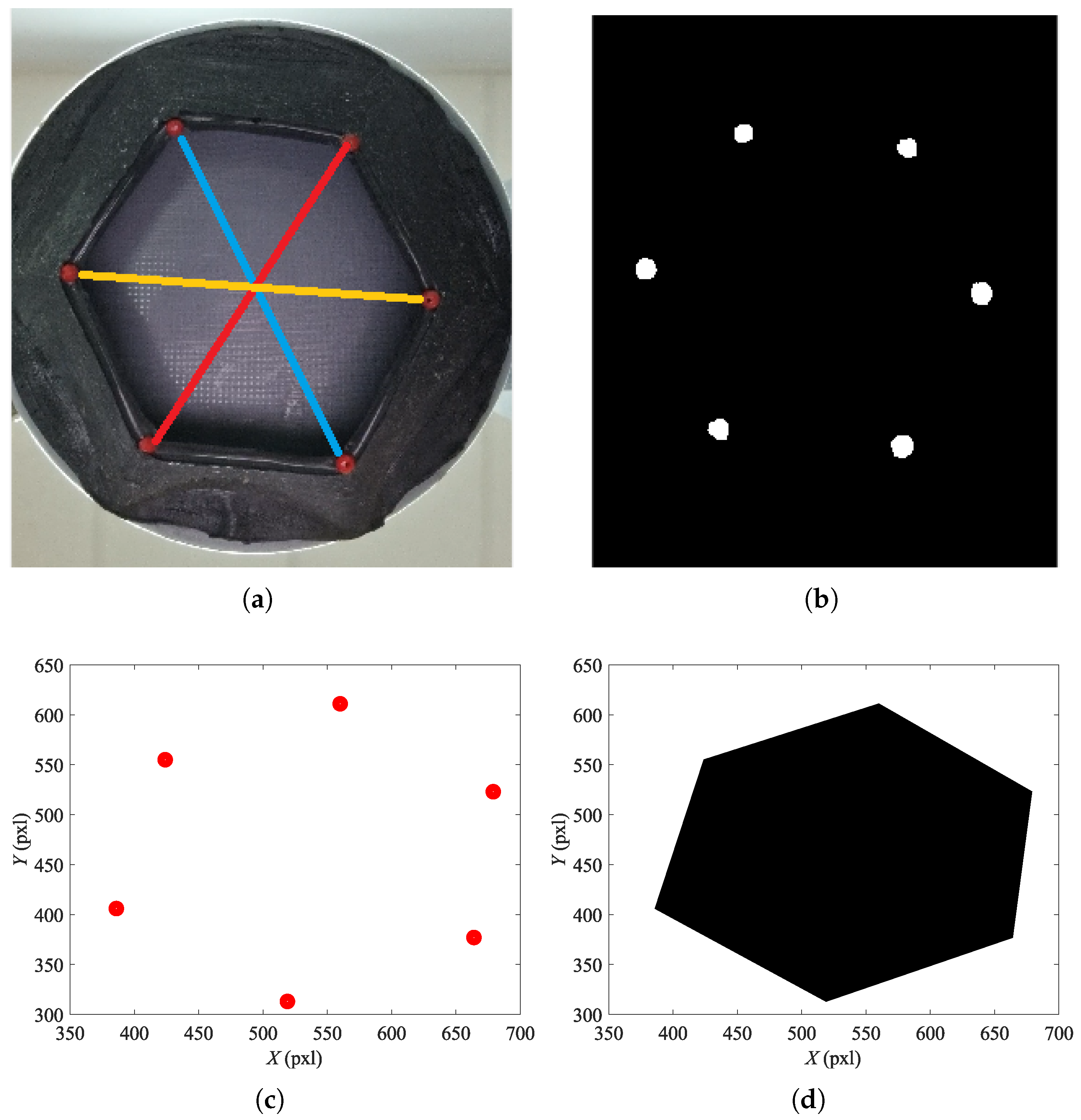

2. MRE Gripper

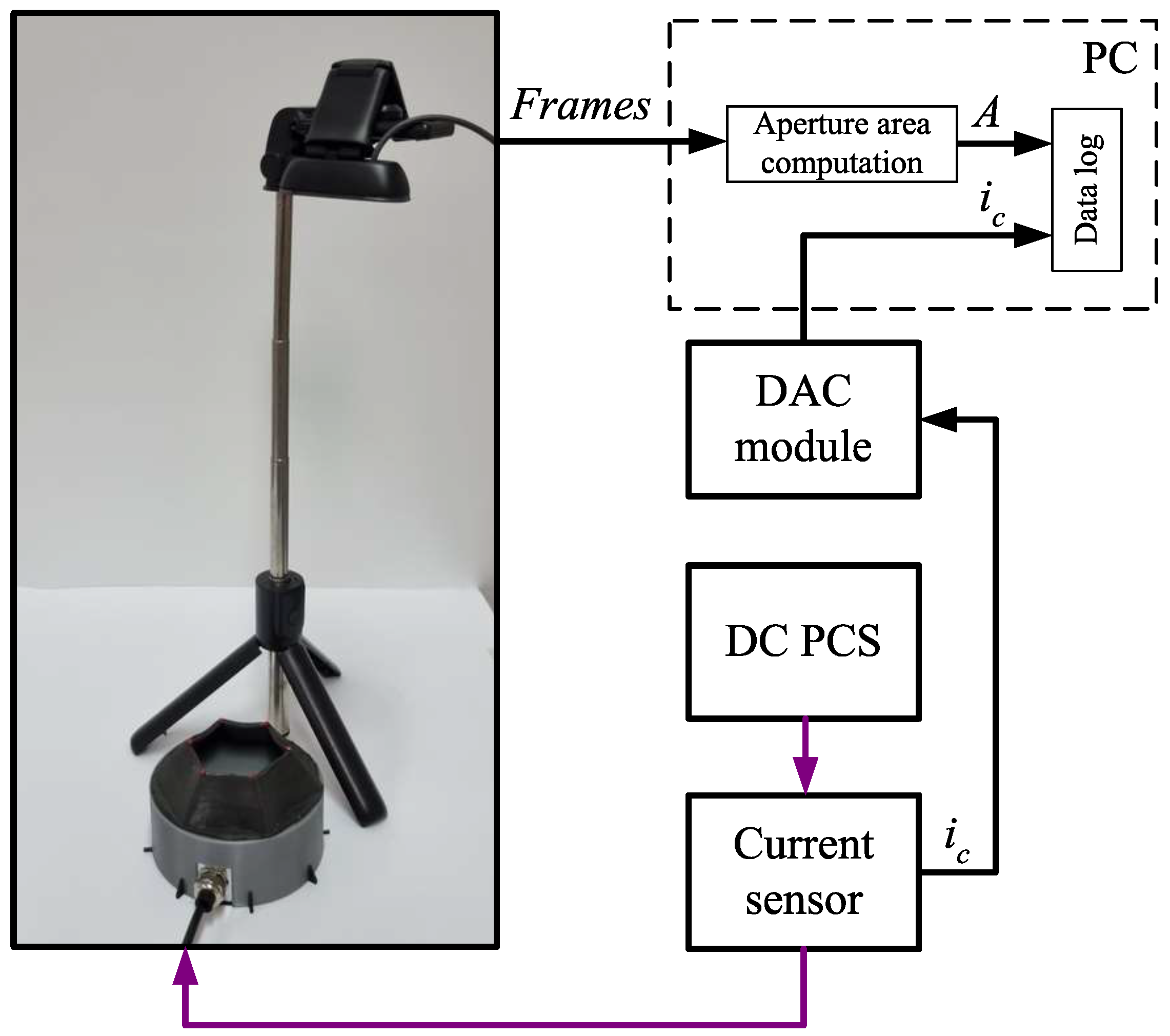

3. Test Rig, Setup and Inputs

4. Results

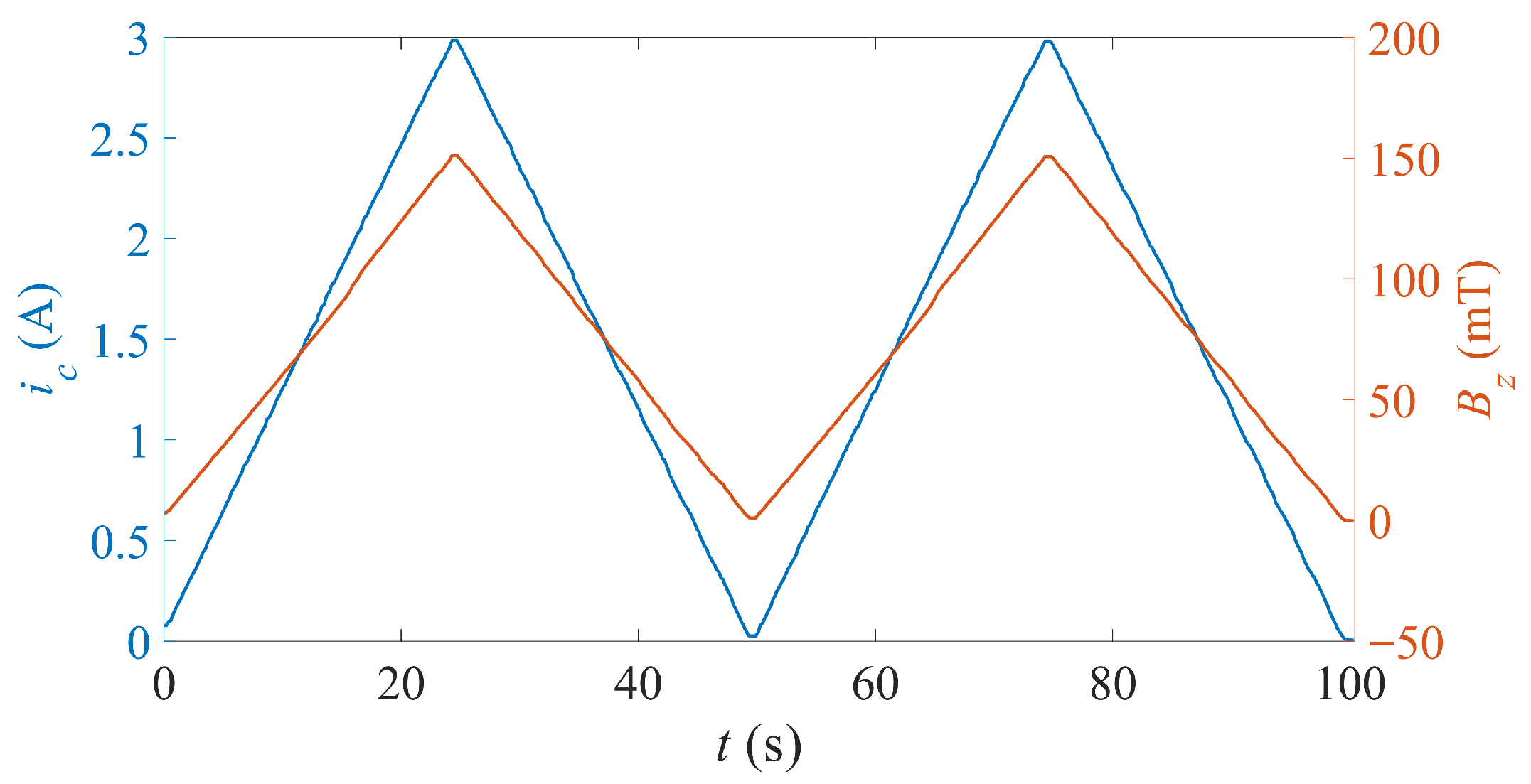

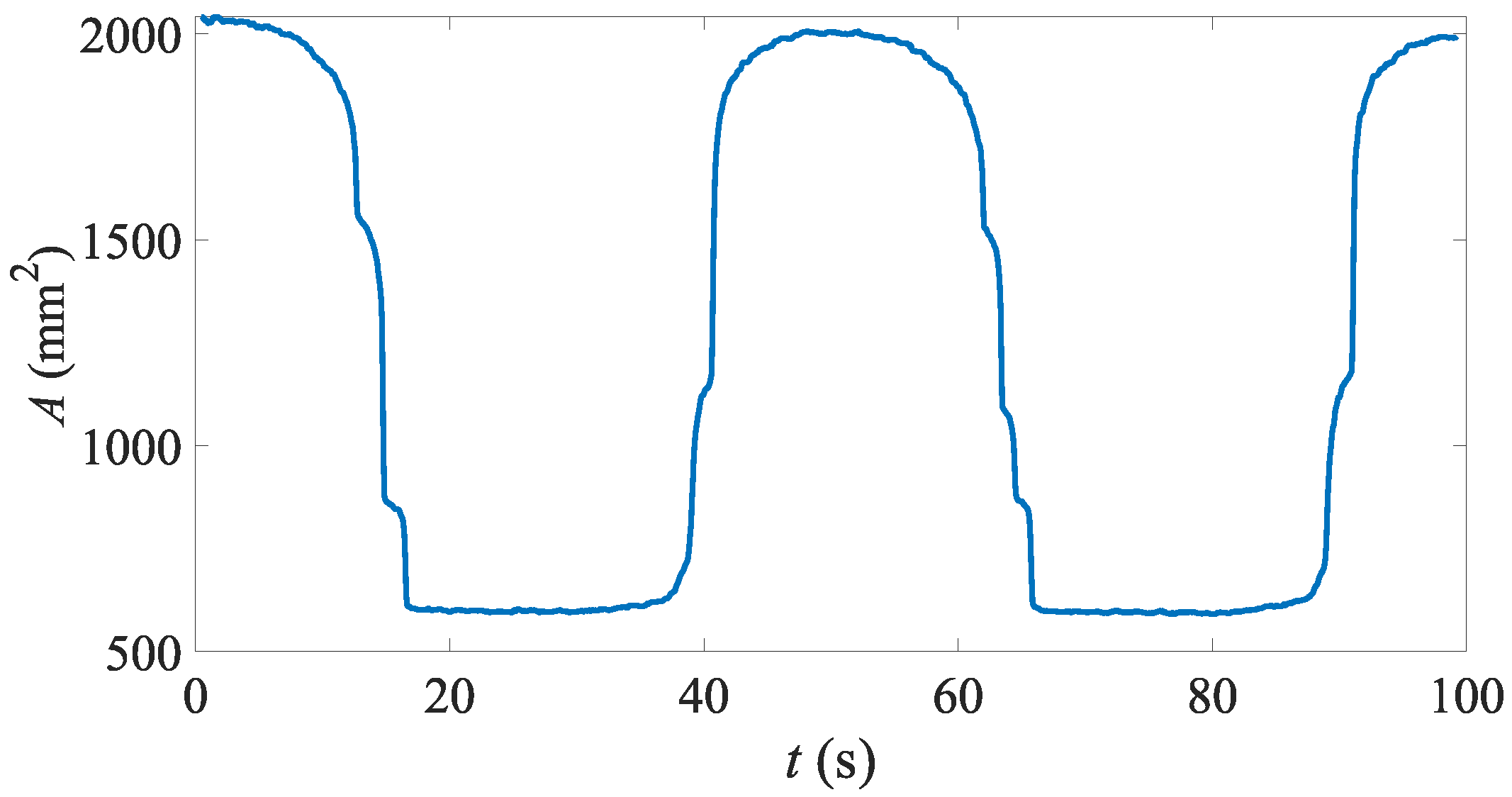

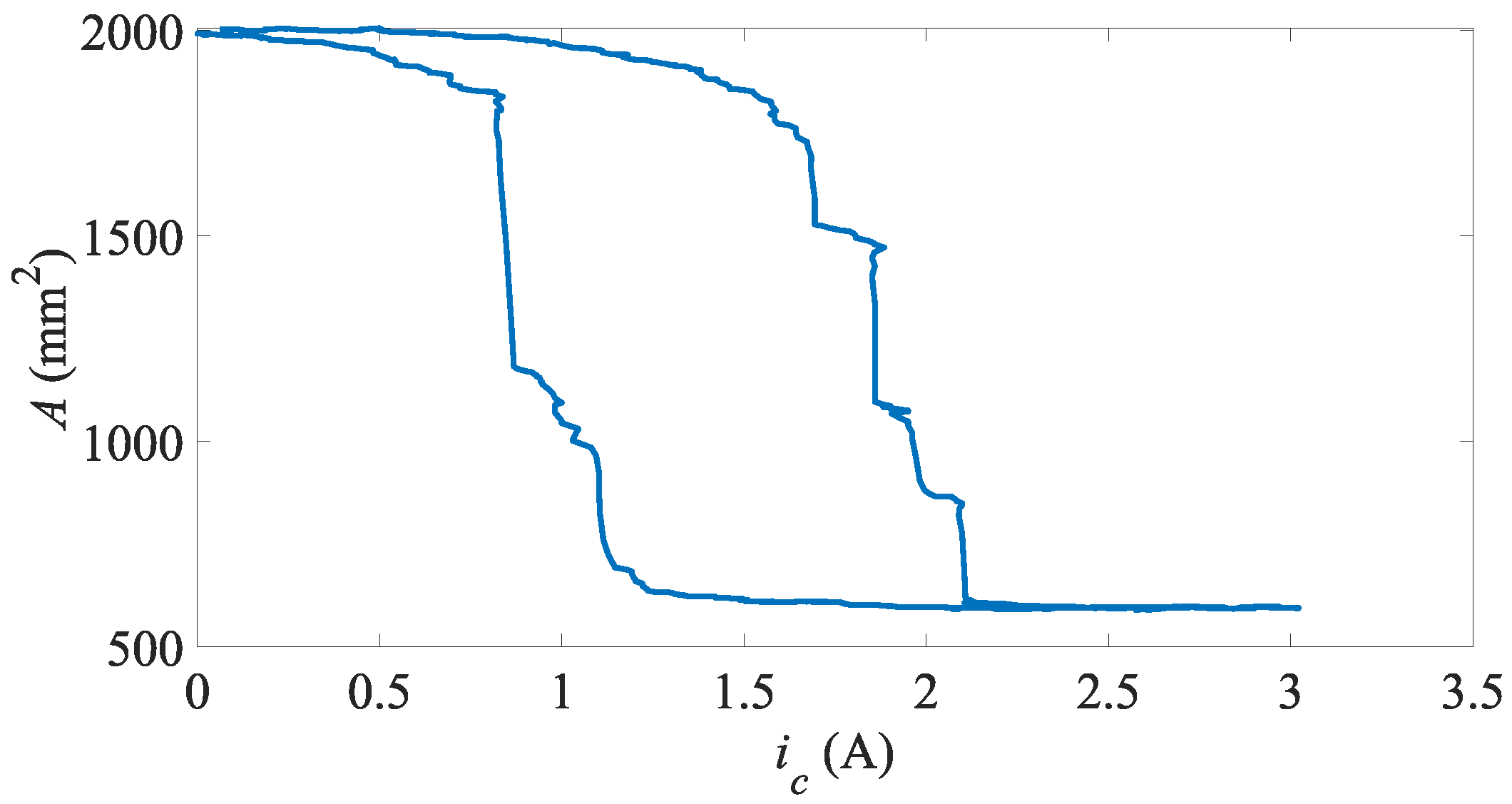

4.1. Free (No Load) State

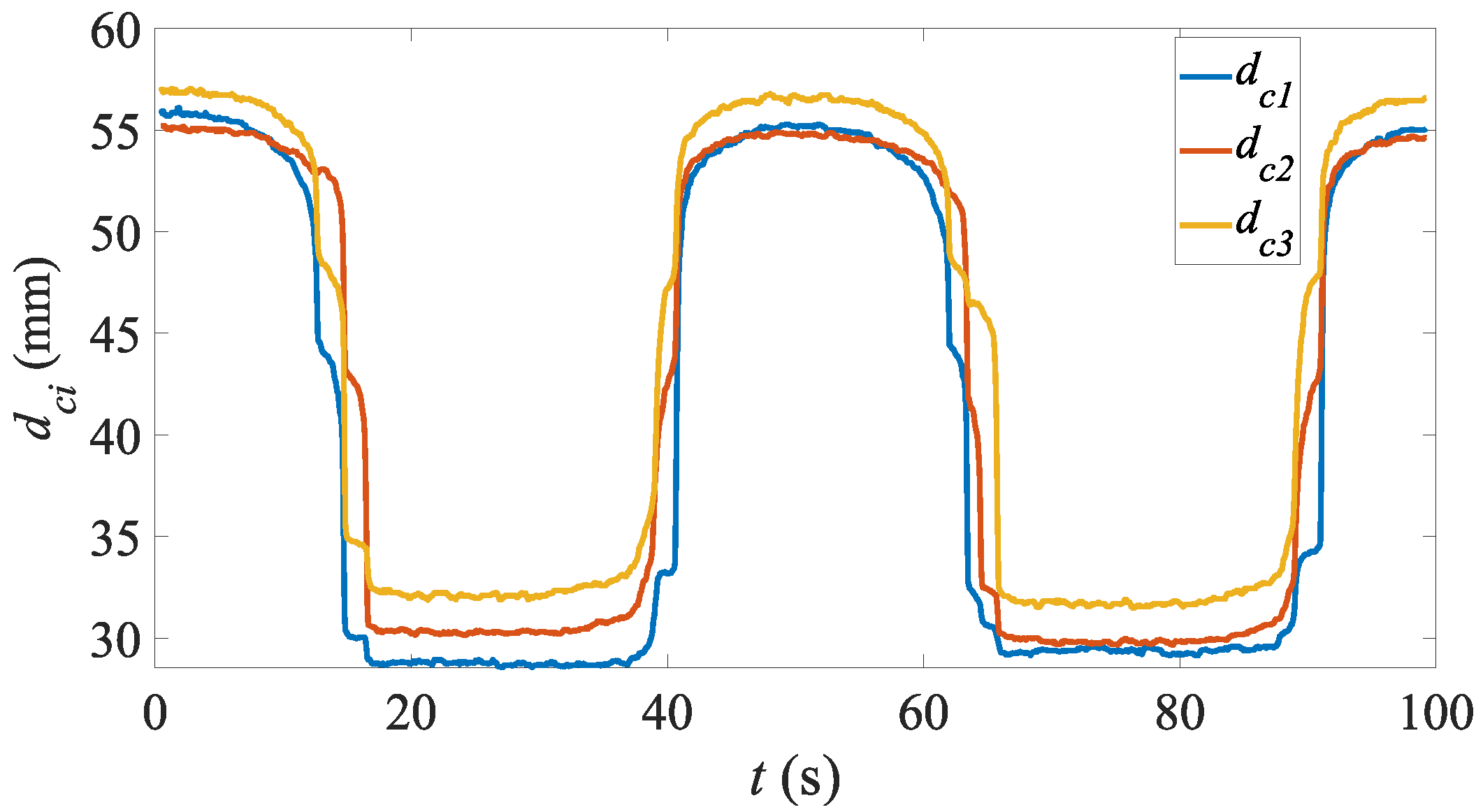

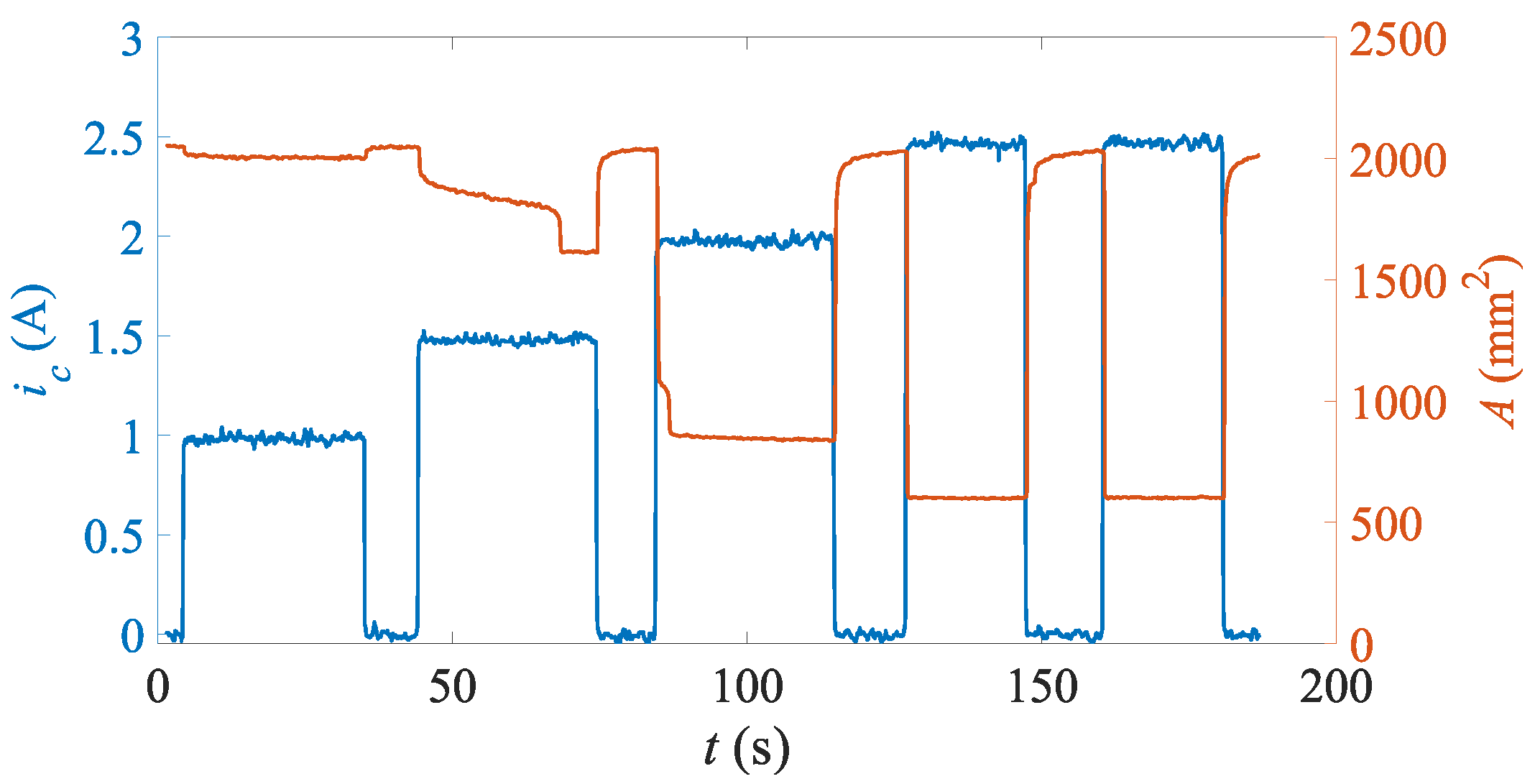

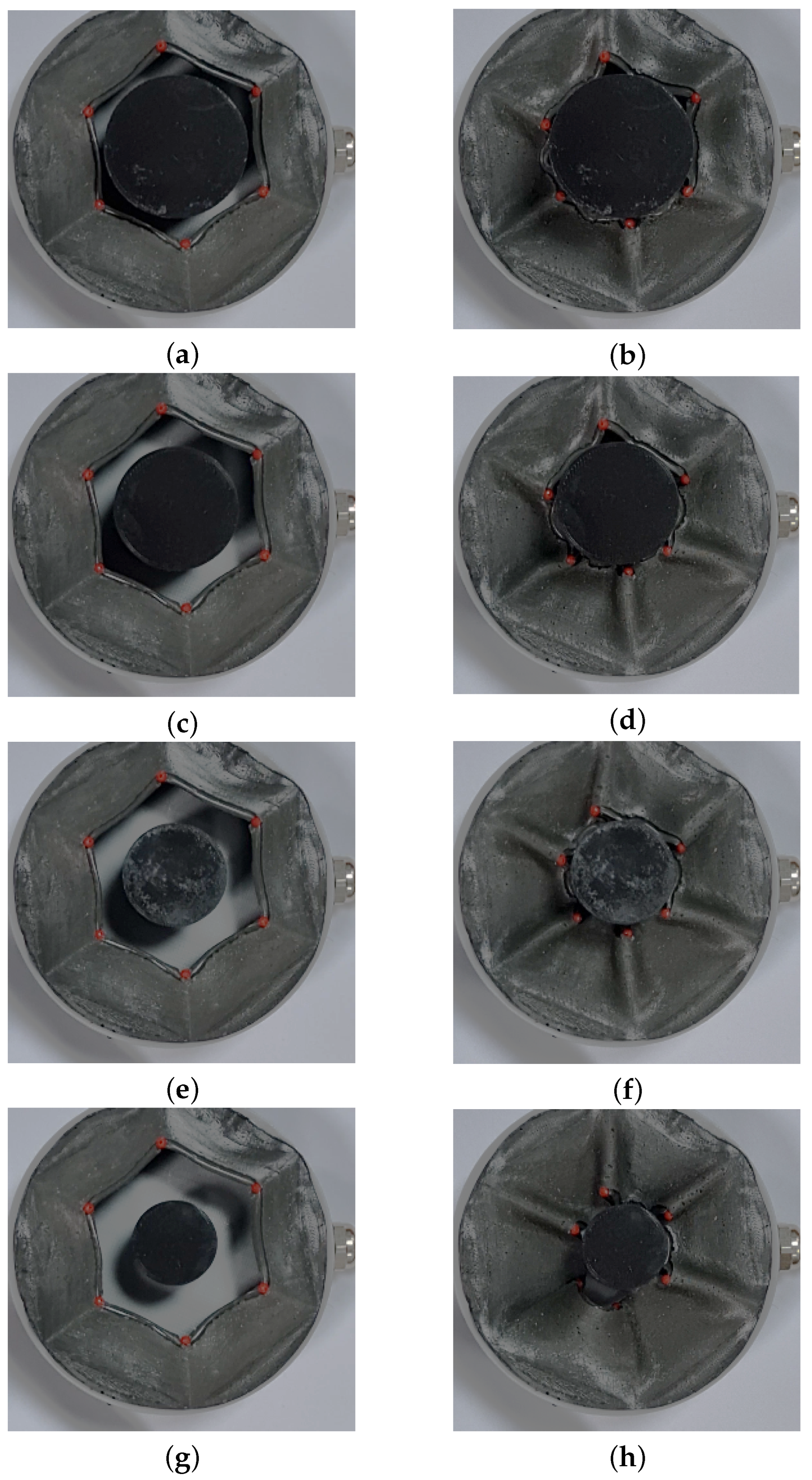

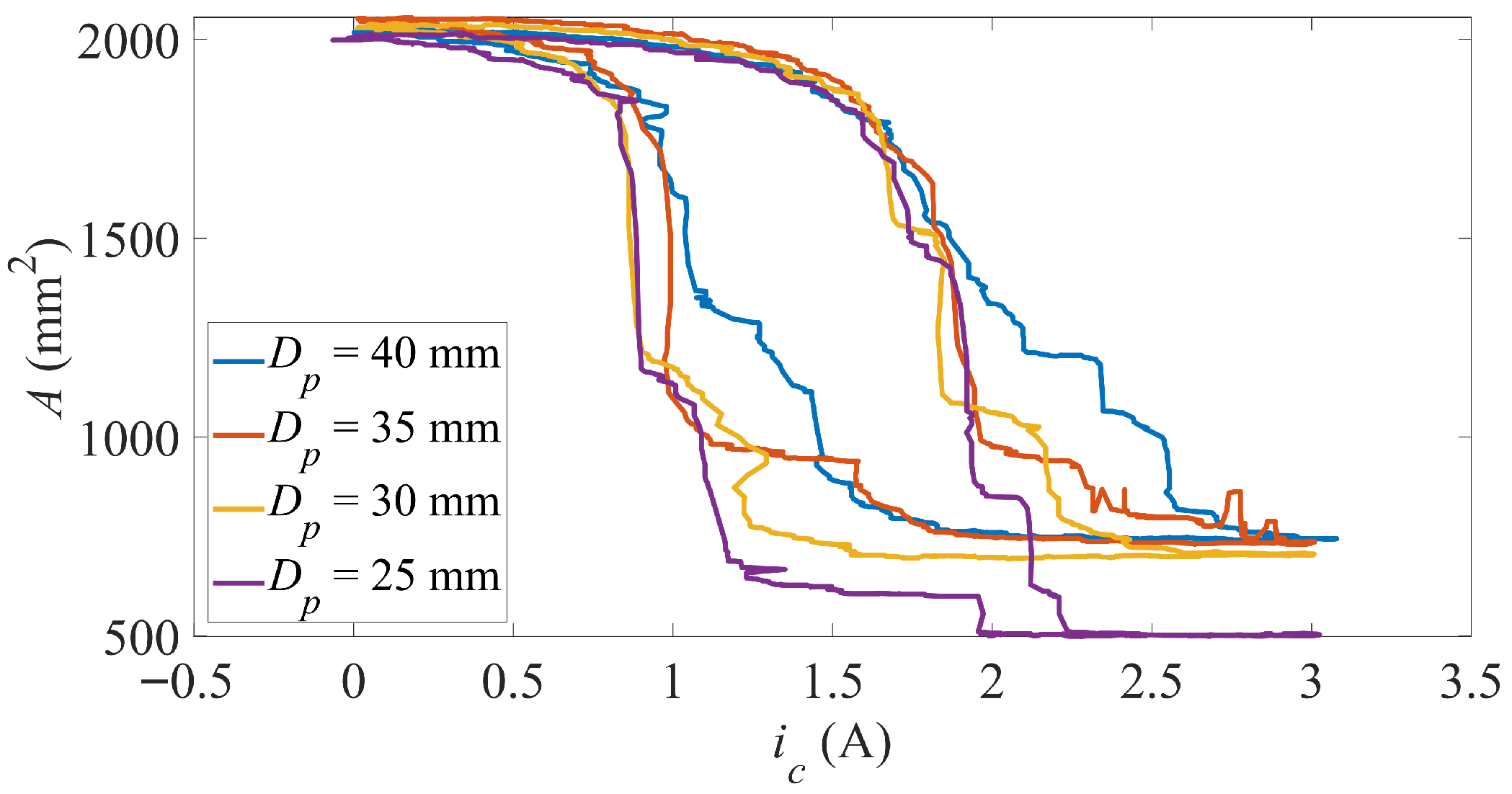

4.2. Cylindrical Objects

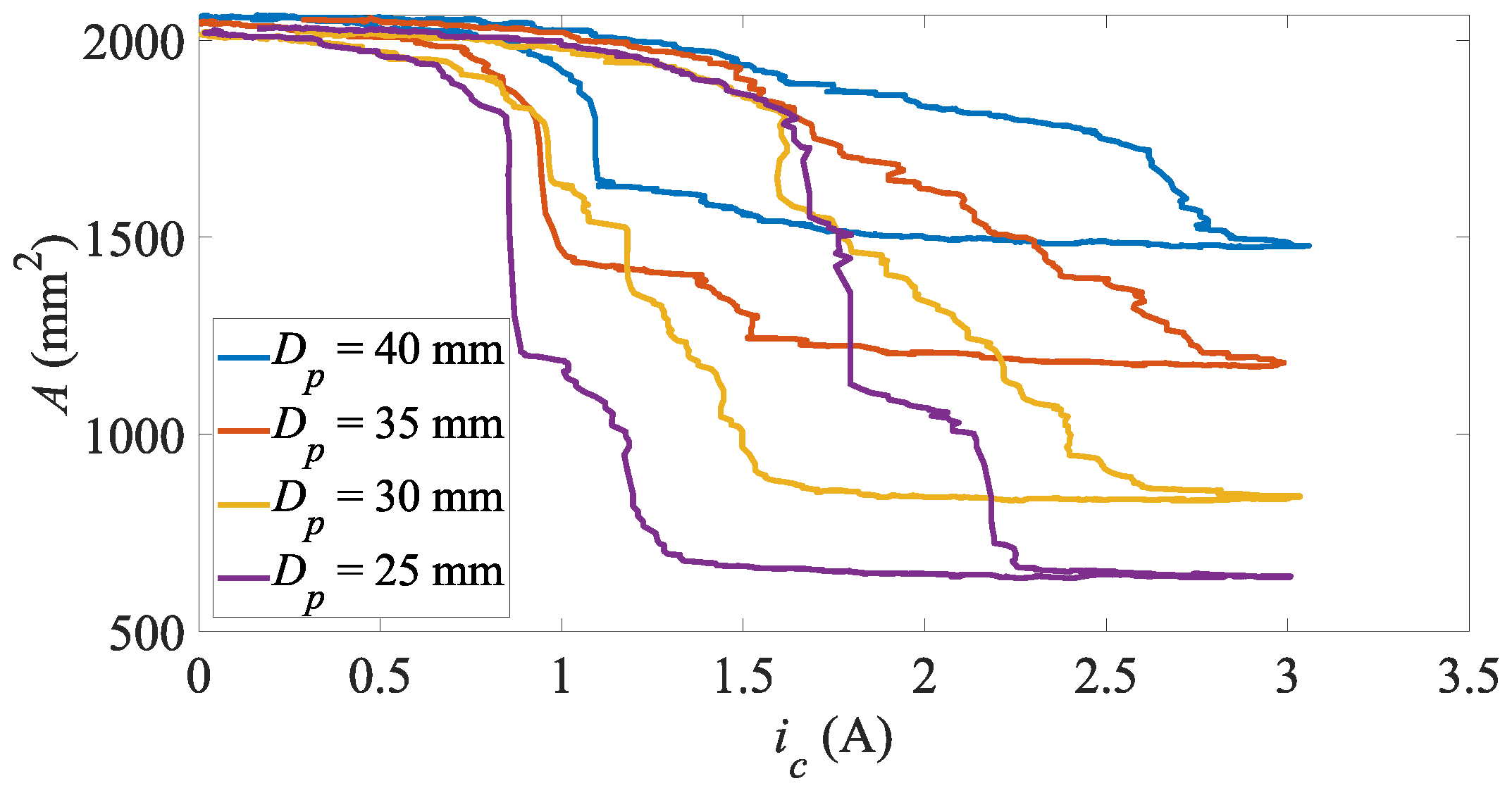

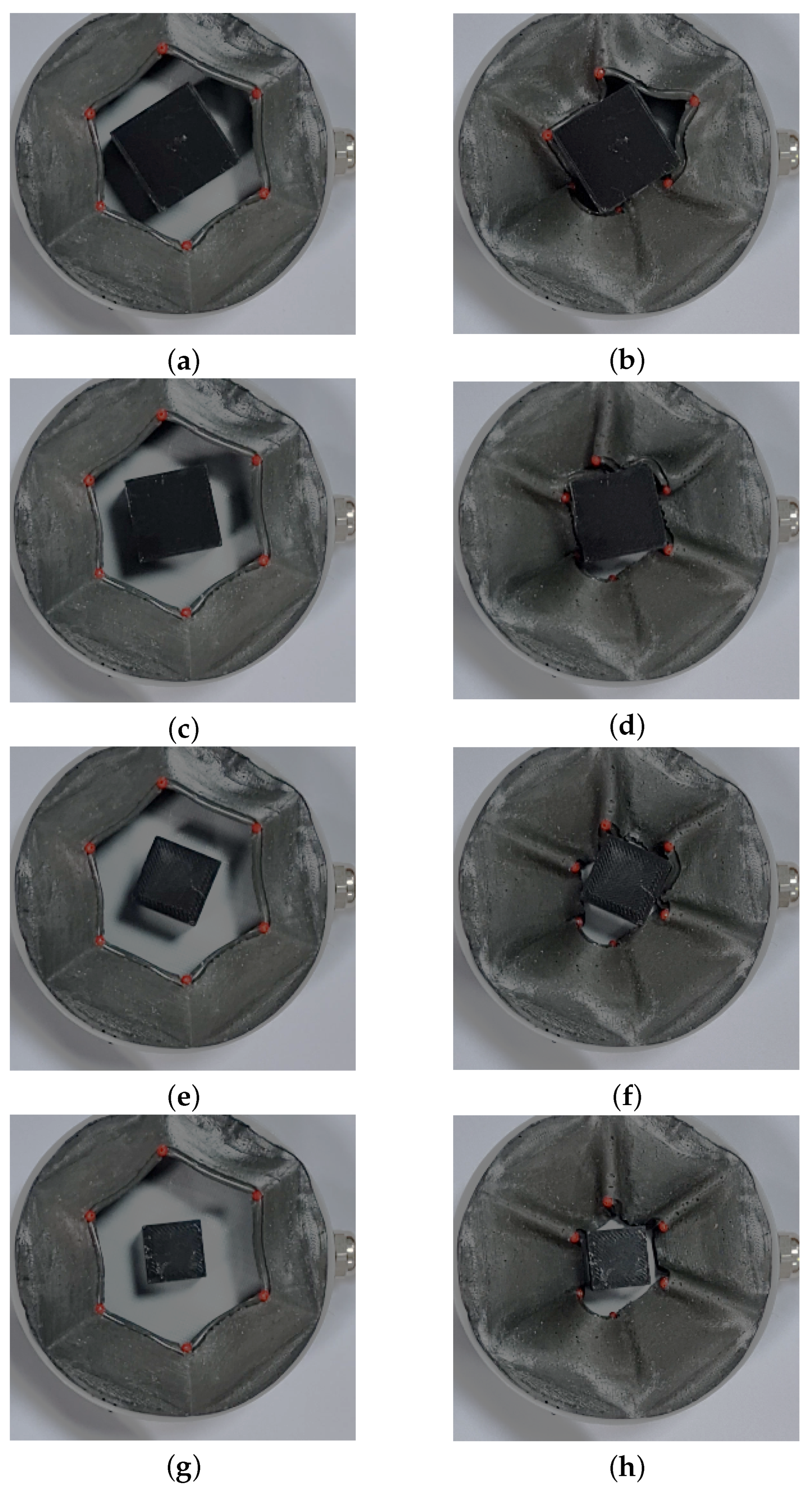

4.3. Cubic Objects

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.; Maselli, M.; Laschi, C.; Cianchetti, M. Actuation Technologies for Soft Robot Grippers and Manipulators: A Review. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2021, 2, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, A.; Davis, S.; Gray, J.O.; Dodd, T.J.; Ohlsson, T. Design of a magnetorheological robot gripper for handling of delicate food products with varying shapes. J. Food Eng. 2010, 98, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Chung, Y.S.; Rodrigue, H. Long Shape Memory Alloy Tendon-based Soft Robotic Actuators and Implementation as a Soft Gripper. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, H.; Wang, W.; Kim, D.R.; Ahn, S.H. Curved shape memory alloy-based soft actuators and application to soft gripper. Compos. Struct. 2017, 176, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Cheng, P.; Yan, B.; Lu, Y.; Wu, C. Design of a Novel Soft Pneumatic Gripper with Variable Gripping Size and Mode. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. Theory Appl. 2022, 106, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Baek, S.R.; Kim, M.S.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, I.H. Design and manufacturing process of pneumatic soft gripper for additive manufacturing. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 370, 115218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Chen, Z.; Ren, F.; He, L.; Chen, J.; Yin, L.J.; Luo, Y.; Dang, Z.M.; Mao, J. Dielectric Elastomer Network with Large Side Groups Achieves Large Electroactive Deformation for Soft Robotic Grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourazadi, S.; Bui, H.; Menon, C. Investigation on a soft grasping gripper based on dielectric elastomer actuators. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, J.; Czopek, P.; Superczynska, P.; Gajewski, P.; Marcinkowska, A. The Construction of a Soft Gripper Based on Magnetorheological Elastomer with Permanent Magnet. J. Intell. Mater. Sys. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, M.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, H.; Jiang, S. A magneto-active soft gripper with adaptive and controllable motion. Smart Mater. Struct. 2021, 30, 015024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivikko, A.; Drotlef, D.M.; Sitti, M.; Sariola, V. Magnetically switchable soft suction grippers. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2021, 44, 101263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Shin, H.N.; Park, J.; Suh, J.; Kim, Y.K. Friction variable rubber pad using magnetorheological elastomer for robot grippers. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2023, 34, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek, M.; Jędryczka, C.; Milecki, A. Investigation of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Finger Cushion with Magnetorheological Fluid for Soft-Rigid Gripper. Energies 2021, 14, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintake, J.; Cacucciolo, V.; Floreano, D.; Shea, H. Soft robotic grippers. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, J.H.; Dawson, A.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, K.S. Experimental investigation of magneto-rheological based elastomers based on hard magnetic fillers. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Adaptive Structures and Technologies 2010, ICAST 2010, State College, PA, USA, 4–6 October 2010; pp. 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Yarali, E.; Baniasadi, M.; Zolfagharian, A.; Chavoshi, M.; Arefi, F.; Hossain, M.; Bastola, A.; Ansari, M.; Foyouzat, A.; Dabbagh, A.; et al. Magneto-/electro-responsive polymers toward manufacturing, characterization, and biomedical/soft robotic applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 26, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gordaninejad, F.; Calgar, M.; Liu, Y.; Sutrisno, J.; Fuchs, A. Sensing Behavior of Magnetorheological Elastomers. J. Mech. Des. 2009, 131, 091004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.A.M.; Nazmi, N.; Nordin, N.A.; Mazlan, S.A.; Rahman, M.A.A. An overview of graphite utilization in magnetorheological materials. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 3124, p. 080007. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, G.; Tang, S.Y.; Sun, S.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, Q.; Deng, L.; Yan, S.; Du, H.; Dickey, M.D.; Li, W. Liquid metal-filled magnetorheological elastomer with positive piezoconductivity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, K.; Navas, E.; Emmi, L.; Fernandez, R. Manufacturing of 3D printed soft grippers: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30434–30451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, L.; Qiu, Y. Advancements in Semi-Active Automotive Suspension Systems with Magnetorheological Dampers: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordonski, W.I.; Jacobs, S.D. Magnetorheological finishing. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 1996, 10, 2837–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Dapino, M.J. Review of magnetostrictive materials for structural vibration control. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.; Cramer, M.; Demeester, E.; Kellens, K. Exploring the potential of magnetorheology in robotic grippers. Procedia CIRP 2018, 76, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, R.; Choi, S.B.; Ferdaus, M.M. A state of art on magneto-rheological materials and their potential applications. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2018, 29, 2051–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böse, H.; Gerlach, T.; Ehrlich, J. Magnetorheological elastomers—An underestimated class of soft actuator materials. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2021, 32, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Du, H. A state-of-the-art review on magnetorheological elastomer devices. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.S.; Paul, P.S.; Raghunathan, G.; Alex, D.G. A review of challenges and solutions in the preparation and use of magnetorheological fluids. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2019, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Yoon, J. High-Load Capable Soft Tactile Sensors: Incorporating Magnetorheological Elastomer for Accurate Contact Detection and Classification of Asymmetric Mechanical Components. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Lai, S.; Wang, X.; Gong, X. Enhanced Mechanical-Magnetic Coupling and Bioinspired Structural Design of Magnetorheological Elastomers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2419111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Huang, Q.; Jian, Y.; Lu, H.; Zou, X.; Shen, T. Recent advances in magnetorheological materials and applications in robots and medical devices. J. Polym. Eng. 2025, 45, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.J.; Parsons, A.M.; Zheng, L. Magnetically controlled soft robotics utilizing elastomers and gels in actuation: A review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, J.; Gajewski, P.; Kołota, J.; Marcinkowska, A. Review of soft actuators controlled with electrical stimuli: IPMC, DEAP, and MRE. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vilsteren, S.J.; Yarmand, H.; Ghodrat, S. Review of magnetic shape memory polymers and magnetic soft materials. Magnetochemistry 2021, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, F.; Huang, X.; Yue, X. Review of Flexible Robotic Grippers, with a Focus on Grippers Based on Magnetorheological Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Ou, K.; sen Li, D.; Fan, J.; Fu, Q.; Sun, Y. DIW 3D printing of hybrid magnetorheological materials for application in soft robotic grippers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 223, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, J.; Gajewski, P.; Kapela, R.; Marcinkowska, A.; Superczyńska, P. Design, Fabrication and Analysis of Magnetorheological Soft Gripper. Sensors 2022, 22, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.T.; Hartzell, C.M.; Leps, T.; Wereley, N.M. Gripping characteristics of an electromagnetically activated magnetorheological fluid-based gripper. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 056701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, C.M.; Choi, Y.T.; Wereley, N.M.; Leps, T.J. Performance of a magnetorheological fluid-based robotic end effector. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 035030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| , | , | T, s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2060 | 56 | 2.106 |

| A | 2046 | −51 | 0.469 |

| A | 1963 | 150 | 5.975 |

| A | 2028 | −444 | 0.183 |

| A | 1981 | 1129 | 0.456 |

| A | 2006 | −1310 | 0.212 |

| A | 2037 | 1436 | 0.0105 |

| A | 2011 | −1519 | 0.147 |

| A | 2079 | 1475 | 0.0157 |

| A | 2041 | −1623 | 0.191 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutenko, D.; Gołdasz, J.; Sapiński, B.; Orkisz, P. Soft MRE Gripper: Preliminary Study. Actuators 2025, 14, 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120585

Gutenko D, Gołdasz J, Sapiński B, Orkisz P. Soft MRE Gripper: Preliminary Study. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):585. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120585

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutenko, Denys, Janusz Gołdasz, Bogdan Sapiński, and Paweł Orkisz. 2025. "Soft MRE Gripper: Preliminary Study" Actuators 14, no. 12: 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120585

APA StyleGutenko, D., Gołdasz, J., Sapiński, B., & Orkisz, P. (2025). Soft MRE Gripper: Preliminary Study. Actuators, 14(12), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120585