Abstract

In 1918, San Ildefonso Pueblo artist Crescencio Martinez completed two commissions for the anthropologist Edgar L. Hewett: A set of paintings and a series of tiles. The paintings, called the Crescencio Set, mark a formative moment in the development of a new genre of art, modern Pueblo painting. Before Crescencio and his San Ildefonso peers began creating images of ceremonial and daily life for sale to outsiders, they were hired as day laborers at archaeological excavations. While Pueblo laborers benefited financially from working with anthropologists, they nevertheless understood anthropology as a threat to their communities, as scientists disrupted sacred sites and the dead, collected sensitive material, and pushed informants for esoteric information. In countering this new colonial threat, Pueblo communities deployed long-developed tactics of resistance. Among the most powerful of these tactics is what Audra Simpson calls “refusal”. Many Pueblo laborers refused to share esoteric knowledge with anthropologists, a tactic adopted by those laborers who became artists. Early Pueblo paintings can, thus, be understood as “ana-ethnographic”, a representational mode through which the artists worked both through and against ethnographic norms in order to simultaneously benefit from, manipulate, and resist scientific colonialism. Crescencio’s paintings and tiles are paradigmatically ana-ethnographic. In creating these objects, Crescencio benefited from the ethnographic desire to know and record Pueblo life, and yet he only represented aspects of his culture appropriate for outsider consumption, refusing to share protected knowledge.

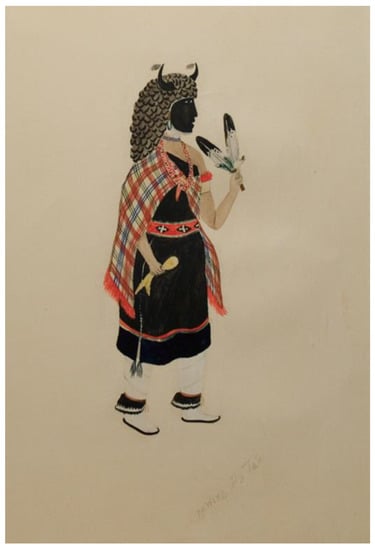

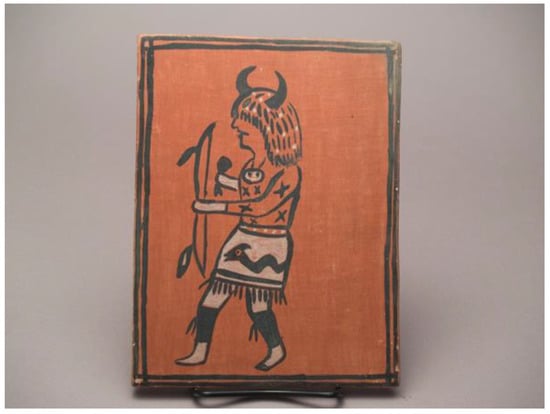

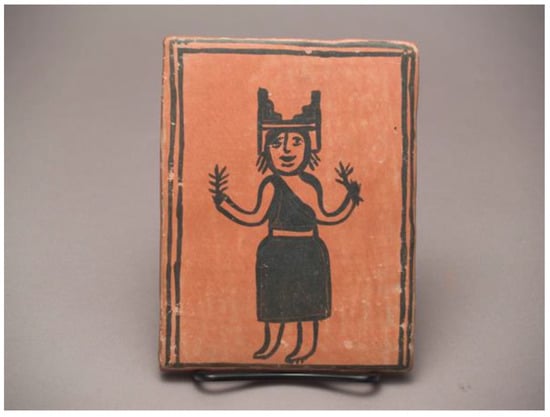

In the days before his tragic death on 20 June 1918, Crescencio Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo finished a remarkable series of paintings. In 1917, anthropologist Edgar L. Hewett commissioned the paintings, which he called the Crescencio Set. Around the same time, Hewett also commissioned Crescencio to create a series of pottery tiles.1 Most of the paintings and the tiles picture one participant in a public ceremonial dance. For example, the painting Buffalo Mother (Figure 1) and a tile with a buffalo dancer (Figure 2) both depict performers in the Buffalo Dance that occurs annually on the pueblo’s feast day, January 23. The Crescencio Set has long been understood by scholars as marking a critical moment in the formation of “modern Pueblo painting”, a genre of figurative painting on paper or canvas intended for outsider markets, which developed in the 1910s and blossomed in the 1920s.

Figure 1.

Crescencio Martinez, Buffalo Mother, 1918. Watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 24158/13.

Figure 2.

Crescencio Martinez, Tile, c. 1917–1918. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 18737/12.

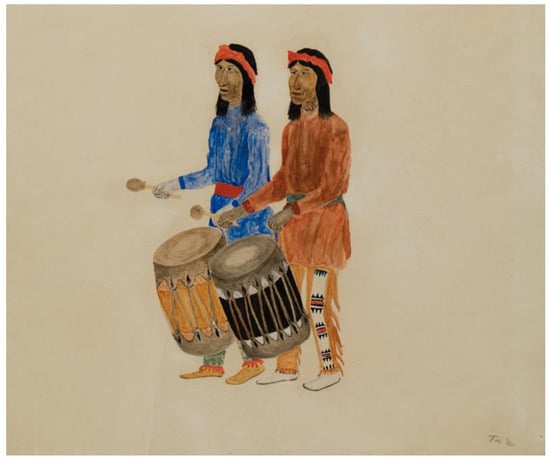

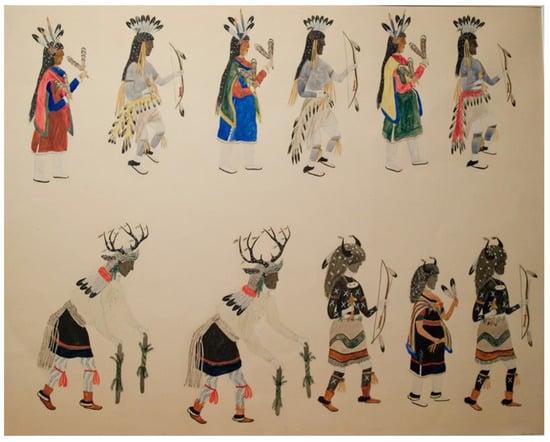

Early modern Pueblo paintings typically represent ceremonial dances, as is the case with Crescencio’s work, and “home scenes”, such as the making of bread and pottery. Pueblo ceremonials, which include dancing, drumming (Figure 3), and singing, are deeply symbolic and are akin to prayers to animals, for rain, and for agricultural growth. Ceremonials honor the interdependence between humans and non-humans.2 Crescencio rendered ceremonial dancers with great care and attention to detail, as is evinced in the Crescencio Set, as well as in his few multifigure compositions, including Eleven Figures of the Animal Dance (Figure 4). Crescencio generally set his figures in profile and before an unarticulated background. His figures dance with focused attention; their steps are gentle yet purposeful. Crescencio carefully rendered every detail, as seen in the texture of the skunk fur on dancers’ moccasins and their finely rendered feathers pictured in Eleven Figures of the Animal Dance and Buffalo Mother. Each detail is meaningful, from the symbolic avanyu (water serpents) on the dancers’ kilts to their rattles and body paint. Crescencio painted dances he knew well, rendering them from memory and drawing on his own experiences.

Figure 3.

Crescencio Martinez, Two Drummers, 1918. Watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 24157/13.

Figure 4.

Crescencio Martinez, Eleven Figures of the Animal Dance, c. 1918. Watercolor and gouache on paper. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 24145/13.

Although San Ildefonso children had been creating figurative images on paper for government school-teachers since the early 1900s, and Pueblo artists had been selling paintings of community life to outsiders since the early 1910s, it was not until after the completion of the Crescencio Set that modern Pueblo painting established itself as an artistic movement.3 This commission led Hewett to support Pueblo painting on paper more broadly. A year after the set was completed, Hewett agreed to exhibit paintings by students of Elizabeth DeHuff, a teacher at the Santa Fe Indian School. In 1919, paintings by Velino Shije Herrera (Zia Pueblo), Fred Kabotie (Hopi), and many other young Pueblo artists went on view at the new Museum of Fine Arts in New Mexico.4 With the support of Hewett, other anthropologists, and a growing number of cultural modernists, including Amelia E. White, Mabel Dodge Luhan, and John Sloan, by the mid-1920s modern Pueblo painting had found national and international audiences and markets.5

Crescencio sold relatively few paintings before he succumbed to the devastating influenza pandemic of 1918, which hit Pueblo communities particularly hard. Nevertheless, his art and story tell historians a good deal about the fraught and inequitable conditions of production in which modern Pueblo painting developed and how Pueblo artists negotiated these conditions. Almost every San Ildefonso artist who was part of the first-generation of modern Pueblo painters was supported by Hewett early in his or her career, including Crescencio, Julián Martinez (1879–1943), Tonita Peña (Quah Ah, 1893–1949), and Awa Tsireh (Cattail Bird, 1898–1955, also known as Alfonso Roybal). Hewett bought many of their earliest paintings. As significantly, well before the aforementioned San Ildefonso men began painting for Hewett, they all worked as a day-laborers at Hewett’s archeological digs.6 At the same time Pueblo laborers drew much-needed income from archaeological work, anthropology was perceived by Pueblo communities as an intrusive force and a threat. Many Pueblo communities were deeply concerned about and resisted anthropologists’ efforts to exhume the dead, excavate sacred spaces, empty historical sites, and record and publish esoteric information.7 To combat these intrusions, Pueblo laborers shared information with anthropologists with caution. Those laborers who became artists carried this caution into their art making.

This paper argues that most first-generation San Ildefonso painters drew from lessons they had learned as laborers for anthropologists, a role that required them to balance the desires of white employers and the needs of their community. This perspective is supported by an analysis of Crescencio’s paintings and tiles for Hewett, which can be understood as “ana-ethnographic”—a term I propose, which builds on and sharpens Mary Louise Pratt’s concept of “autoethnography”. “Ana-ethnographic” texts and images are created in a representational mode that works toward, through, and against ethnographic norms, empowering artists to simultaneously benefit from, manipulate, and resist “scientific colonialism”.8 Crescencio’s ana-ethnographic paintings and tiles deploy many tactics of resistance, the most prominent of which is what Audra Simpson calls “refusal”. This tactic was used by many first-generation modern Pueblo painters, allowing them to sell their art to patrons seeking records of Pueblo life while also safeguarding their communities from threats posed by scientific colonialism.

1. Ana-Ethnography and Tactics of Refusal

From the time of their creation until the 1990s, modern Pueblo paintings were often described by scholars as ethnographic records of Pueblo life.9 Statements made by many first-generation painters, at first pass, seemed to be in keeping with this perspective. In his autobiography, Fred Kabotie wrote that he wanted to “paint important Hopi ceremonies…to preserve the details for future generations”. “As the older Hopis passed away, more and more of these things were being lost”, he explained, “I knew I must record them”. In a similar vein, Velino Shije Herrera once stated, “I have danced the ceremonies. I feel it is important to record these costumes”.10

In the 1990s, many scholars began to productively challenge the notion that Pueblo paintings are unmediated records by describing the genre as “autoethnographic”, a term drawn from the work of Mary Louise Pratt. Pratt introduced the concept in a 1991 essay “Arts of the Contact Zone” and elaborated on it in her landmark book, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (1992). Thereafter, the term was adopted by scholars working on a wide range of Indigenous material and visual culture.11 Pratt (1991, p. 34) theorized that autoethnographic texts are created in “contact zones”, which she defined as “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism”. Pratt was careful to argue that autoethnographic expressions are not reflections of colonial narratives, but rather responses to and in dialogue with dominant representations of the Other (Pratt 1992, pp. 7, 102). She rightly warned scholars against seeing autoethnographic texts as pure, innocent, or unmediated windows into the lives of colonized peoples or as unambivalent forms of self-description and self-reflection. Autoethnographic narratives, like all historical texts, are motivated by the political and social needs of the author (ibid., pp. 2, 7).

Pratt (1992, p. 7) defined autoethnographic expressions as “instances in which colonized subjects undertake to represent themselves in ways that engage with the colonizer’s own terms”.12 Scholars who draw from her work typically cite this definition, emphasizing how colonial subjects adopted the media and style of the colonizer in order to respond to colonial representations. However, there is another fundamental aspect of Pratt’s formulation that sometimes get dampened or lost. Pratt argued that autoethnographic texts use the colonizer’s own language to reframe, challenge, and subvert colonial constructions of the colonized. Prattian autoethnography is a mode of resistance within the fraught and highly inequitable spaces of colonialism.13 For me, the conceptual power of the term rests on this idea.

Pratt’s concept of autoethnography is used inconsistently, and some of the confusion can be attributed to the term itself—the word “autoethnography” is the concept’s greatest liability. Pratt herself acknowledged that her use of the term was “idiosyncratic”. 14 Around the time Pratt popularized the concept in Imperial Eyes, a new research method was taking hold among ethnographers. While the term “autoethnography” has a longer history, during mid 1980s anthropologists and sociologists were defining it as a research method that blends autobiography and ethnography.15 Autoethnography is a method that connects the researcher’s personal experience to the study of a culture and that embraces self-writing and self-reflection.

While today there is heated debate about this highly flexible method, most agree that by infusing one’s academic research with personal reflections and narratives, one can disrupt notions of objectivity and the authority of the researcher.16 Importantly, those who use this method generally self-identify as researchers and are part of the academic system, which, in the words of Audra Simpson, “rests upon Empire” (Simpson 2007, p. 78). Although Pratt was aware of and contributed to the critiques of anthropology that led to the development of autoethnography as a research method, this is not how she used the term in her work.17 The colonial subjects who create autoethnographic texts in Imperial Eyes are neither ethnographic researchers nor part of the colonial power structure; rather, they are the objects of colonial power, including research.

If scholars sometimes conflate Pratt’s definition of autoethnography with the research methodology, it is, in part, because her term presents a linguistic challenge. Namely, the “standing meaning” of her term does not fully capture and is in tension with its “occasioned meaning”.18 According to philosophers of language, “standing meaning” is “fixed by convention and known to those who are linguistically competent”. The standing meaning of “autoethnographic” is something like recording (grapho, or to write) the culture (ethno, or ethnicity, race, people) of one’s self (auto). Pratt explained to me that while some use the term to mean “self-writing”, her use was meant to refer specifically to texts that are produced in a dialogic relationship with and that appropriate or redirect the norms and usages of ethnographic writing.19 Thus, she gave the term “occasioned meaning”. Occasioned meaning is “discerned by interpreters in part on the basis of contextual information”—information that, in the case of Prattian autoethnography, is found in Pratt’s work.

With these terminological issues in mind and in order to better highlight the subversive potential of Pratt’s concept, I propose the term “ana-ethnographic”, a representational mode that simultaneously draws from and resists ethnographic norms. The term ana-ethnographic has a number of benefits. First, it is defined by its “standing meaning”—”ana” (toward, throughout, against) + ethnographic (the scientific study of peoples and cultures). Thus, the term makes more explicit the nature and complexity of texts and images created in this representational mode.20 Second, the term makes clear that texts and images created in this mode are neither a form of ethnography nor unambiguously complicit in scientific colonialism. Instead, it signals a deeply ambivalent relationship to ethnography. Third, ana-ethnographic expressions have an explicit relationship to ethnographic practices and modes of representations.21 This term is not meant to be relevant to all representations produced by Indigenous people for colonial markets, but rather points to texts and images that respond to scientific colonialism.

In proposing the term ana-ethnographic, it is necessary to highlight two additional points. To describe a text or image as ana-ethnographic is not to exhaust its interpretive possibilities. Ana-ethnographic paintings, like those created by Crescencio, respond to and resist scientific colonialism, but this is not all that they do. These paintings are also highly innovative, creative interventions. They honor and celebrate ideas fundamental to Pueblo life and have potent meaning for the makers and their communities.22 In addition, ana-ethnography is not an aesthetic category. It is an anti-colonial representational “tactic” that manifests itself in many different ways. Early Pueblo painters’ ana-ethnographic paintings largely rely on the tactic of “refusal”. To understand Pueblo paintings this way is to invoke the work of both Michel de Certeau and Audra Simpson.

De Certeau makes a useful distinction between tactic and strategy. For de Certeau, the “strategic” is a “typical attitude of modern science, politics, and military strategy”. Through strategy, the powerful achieve “mastery of places through sight”, whereby “the eye can transform foreign forces into objects that can be observed and measured”, and thus, controlled. This control is rooted, in part, in the production of knowledge (de Certeau 1984, p. 36). For de Certeau, strategy builds power through the production of knowledge and uses knowledge to justify power. In both ways, strategy is the domain of colonial endeavors, including anthropology.

Ana-ethnographic texts and images are what de Certeau would characterize as a “tactic”. “The space of a tactic”, he writes, “is the space of the other.” It is the space of the disenfranchised, including colonized peoples. A tactic “must play on and with a terrain imposed on it and organized by the law of a foreign power”. Despite these constraints, tactics “maneuver ‘within the enemy’s field of vision’”, exploiting cracks in surveillance and using deception and wit to take advantage of “opportunities” (de Certeau 1984, p. 37). De Certeau had Indigenous peoples in mind when theorizing about “tactics”. In the face of harsh subjugation and conversion when threatened by the Spanish, Native peoples used the “laws, practices, and representations that were imposed on them by force” to ends other than those of their conquerors. Native peoples “made something else” out of Spanish—and later U.S.—laws, practices, and representation, “subverting them from within”, and thus, deflecting some of the power of the dominant social order (ibid., p. 32). Tactics allow Indigenous peoples to evade, and even escape, dominant social order without leaving it (ibid., p. xiii).

One tactic Crescencio used in his ana-ethnographic paintings and tiles was “refusal”. Audra Simpson provocatively theorizes about the politics of refusal, seeing this tactic (although she does not use the word “tactic”) as a way for Indigenous nations to claim and maintain their sovereignty, while being nested in a sovereign colonial state. Her ethnographical research on Kahnawà:ke Mohawk nationhood highlights how “Kahnawakero:non, the ‘people of Kahnawake’, had refused the authority of the state at almost every turn”, including the authority of anthropologists (Simpson 2007, p. 73).23 With this framework in mind, one can argue that modern Pueblo paintings honor the artists’ way of life while refusing to yield to scientific colonialism and to the authority of Western ways of knowing. Pueblo painters proclaimed their communities’ political sovereignty by proclaiming their visual sovereignty, including their right to assert their communities’ worldviews, to self-represent, to resist colonial interference and constructions, and to live, create, and pray as they saw fit.24

Modern Pueblo painters asserted their visual sovereignty, in part, by refusing to represent what anthropologists wanted most: The esoteric. The Crescencio Set is paradigmatically ana-ethnographic. Crescencio adopted the media and style of the colonizer in order to benefit from anthropological patronage, while also deploying tactics of refusal that thwarted the anthropological desire to discover and document all aspects of Pueblo ceremonial life. He engaged in what Simpson calls “a kind of discursive wrestling”, “being pushed and pushing back” (Simpson 2007, p. 74).

2. The Crescencio Set

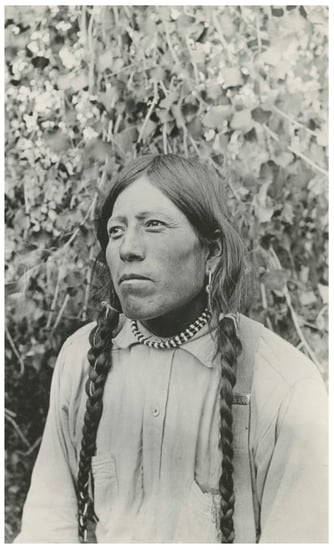

Crescencio Martinez (Figure 5), whose Tewa name is Ta’e (Home of the Elk), was born in 1879 at San Ildefonso Pueblo. San Ildefonso is one of nineteen remaining Pueblo communities in New Mexico, who consider themselves sovereign nations. Northern Pueblos peoples are made up of three different linguistic groups: Tanoan, Keresan, and Zuni. Tanoan is further differentiated into three separate languages: Tiwa, Towa, Tewa. Crescencio’s home community of San Ildefonso is a Tewa-speaking Pueblo (Ortiz 1994, pp. 16–17). Many first-generation modern Pueblo painters were also born at San Ildefonso, including Crescencio’s nephew Awa Tsireh, Tonita Peña, Alfredo Montoya (Wen Tsireh/Tree Bird, 1892–1913), and Julián Martínez. First-generation painters came from other Pueblos too, and most of these artists began their careers at the government-run Santa Fe Indian School under the tutelage of Elizabeth DeHuff, including Velino Shije Herrera, who was from the Keres-speaking community of Zia, and Fred Kabotie, who was from the village of Songòopavi on Second Mesa. The Hopi Nation in Arizona is historically included among Puebloan peoples and is made up of twelve independent villages located on three mesas.

Figure 5.

Judd Neil, “Crescencio Martinez, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico”, 1910. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), 031234.

Margretta Dietrich, an early patron of modern Pueblo painting, claimed that Hewett first realized Crescencio was a capable draftsman around 1910. As the story goes, Hewett saw Crescencio drawing single ceremonial dancers on the ends of cardboard boxes. Intrigued, Hewett gave Crescencio paper and watercolors to create paintings (Dietrich 1936, p. 20).25 Other accounts claim anthropologists first recognized Crescencio’s talents in drawing in 1917 when he was working as a laborer at Otowi, a San Ildefonso ancestral site. There, anthropologist Lucy Wilson uncovered a color fresco of a mountain lion and asked Crescencio to copy it.26 A similar narrative was repeated by Dorothy Dunn, founder of The Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School, who claimed that Hewett was admiring paintings in abandoned cave dwelling near the plateau adjacent to the city of Los Alamos (likely Otowi) in 1917 when Crescencio approached him and declared he could make paintings too. Hewett subsequently commissioned the Crescencio Set, for which Crescencio created “figures of the performers in the two great cycles of Pueblo ceremonies (summer and winter)”, as Hewett explained in Crescencio’s obituary (Hewett 1918, p. 69).27

Crescencio was not the first San Ildefonso artist to sell figurative drawings and paintings to anthropologists. The earliest known representations of Pueblo ceremonials created for sale by a named San Ildefonso artist are attributed to Alfredo Montoya, who sold his dance figures rendered on paper to anthropologists at Rito de Los Frijoles (now part of Bandelier National Park) in the years before his early death in 1913.28 (Notably, Montoya was married to Crescencio’s sister, potter Tonita Martinez Roybal.) At the time of the paintings’ creation, Montoya was a laborer for archaeological digs run by Hewett’s School for American Archaeology, and he worked alongside Julián Martínez and the young Awa Tsireh.29

While creating figurative representations on paper was a new practice, Pueblo artists were drawing from the visual traditions of their own communities. Representations of birds, animals, rainbows, stepped forms, complex battle scenes, ceremonial figures, and figures hunting—imagery prevalent in modern Pueblo painting by the 1920s—abound in ancient, historical, and contemporary Pueblo pottery, kiva murals (kivas are a sacred architectural space), petroglyphs, and pictographs.30 Modern Pueblo painting can, thus, be understood as part of a highly innovative aesthetic continuum (Chase 2002, p. 26). Throughout this long continuum, Pueblo makers have variously adopted, transformed, and resisted new ideas, ways of being, markets, and knowledge systems.

Crescencio brought Hewett the first twelve paintings of the Crescencio Set in late February or March 1918, including Buffalo Mother (Figure 1), signing these paintings “drawing by Ta’e”. Crescencio delivered ten more unsigned paintings later that spring, including Tewa Eagle Dance (Figure 6), completed in the days before his death. He died before he could finish a second eagle dancer, which would have completed the set.31 Some believe that Awa Tsireh, who would become a leading modern Pueblo painter, helped his ailing uncle finish the set.32

Figure 6.

Crescencio Martinez, Tewa Eagle Dancer, c. 1918. Watercolor on gray tag board. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 24165/13.

The completion of the Crescencio Set marks the beginning of a brief period during which Hewett offered Pueblo painters a great deal of financial support. Hewett saw early modern Pueblo paintings as having both aesthetic and ethnographic value, but he placed emphasis on the latter. Hewett’s ethnographic aims in purchasing modern Pueblo painting are signaled in a 1922 essay. He wrote, “it was supposed at one time that we [the Museum of New Mexico] had secured an almost complete list of surviving Pueblo ceremonies” (Hewett 1922, p. 110). This claim was more aspirational than true. As an anthropologist who had worked in New Mexico for over twenty years, Hewett knew well that Pueblo painters largely chose not to represent esoteric subject matter, instead of focusing on home scenes and public ceremonial dances that outsiders could observe.33 Indeed, Kabotie, who claimed he wanted to “record” and “preserve” his community’s traditions through his art, also maintained that he only painted public ceremonials that outsiders were permitted to see.34

By focusing on public ceremonials, Crescencio deployed the tactic of refusal in his Crescencio Set. The set consists of winter game animal dances, corn dances, and eagle dances, all of which were popular among Anglo residents of New Mexico and tourists. Notably, these are the dances most often represented by white illustrators, painters, and photographers, although not without contestation. The recording of sacred and ceremonial knowledge, be it through note-taking, sketching, painting, photography, film, and audio recording, has long troubled Pueblo communities because it intrudes on sacred and solemn events and because recorded information can be widely and indiscriminately circulated. Starting in the 1880s, Pueblo communities placed informal restrictions on recording ceremonials on Pueblo lands, which were formalized by the 1920s and are still in place today.35 Early Pueblo painters were well aware of their communities’ rules against recording knowledge, which applied to artists from the community too. Modern Pueblo painted from memory and most, particularly those who had ritual training and theo-political roles in their communities, were careful to represent subject matter that could be reasonably shared. Modern Pueblo painters who painted esoteric knowledge against the will of their communities were the exceptions among their peers, and the consequences were dire for those who transgressed. Shije Herrera repeatedly painted esoteric subject matter for outsiders, and he was ultimately excommunicated from Zia. The gravity of Shije Herrera’s transgressions is still felt by his community today.36

Within their representations of public dances, San Ildefonso painters used other tactics of refusal too. As I have previously argued with respect to paintings by Awa Tsireh, most Northern Pueblo painters did not depict the full range of participants in ceremonial dances, and their paintings do not disclose information about altars, boundaries, sanctuaries, and shrines that also gave the ceremonials meaning.37 This is true of Crescencio’s paintings, which feature few figures set before unarticulated backgrounds (a pervasive visual trope in modern Pueblo painting). Through these tactics of refusal, Pueblo painters represent their dances, while limiting the flow of information.

Pueblo tactics of refusal were passed down from generation to generation. According to Awa Tsireh’s sister Santana Martinez, Crescencio guided her brother on what and how to paint. She recalls that sometimes her brother would tell her, “‘Oh, I went over to Uncle [Crescencio’s] and he was painting. I asked him about it and he would tell me what do and what would be all right for me to do.’”38 Withholding information was a common and defining tactic among most first-generation San Ildefonso painters. Gilbert Sanchez, son of the first-generation painter Abel Sanchez (Oqwa Pi), similarly maintained that his father and his father’s Tewa peers mostly painted social dances. Sanchez explained that they painted dances that were spiritual, but not secretive, and therefore, “they didn’t exploit their spirituality in a senseless way”.39

3. Protecting Knowledge against Scientific Colonialism

San Ildefonso Pueblo painters refused to share certain knowledge in order to protect their community. Many Indigenous peoples, including Tewa people, believe that knowledge is powerful, and that the most powerful knowledge can only be handled by those who have been trained to use it. One’s access to knowledge depends on one’s status in the community and one’s level of ritual training. Sharing esoteric information with unentitled or uninitiated parties violates the sanctity of this knowledge and drains it of its power. When protected knowledge is shared, it puts both transgressors and their communities at risk. The result can be illness, failure of crops, lack of rain, the death of livestock, etc.40 While guarding knowledge is internal to Pueblo communities, scholars have argued that doing so became all the more critical for Pueblo peoples’ survival as their homelands were invaded, colonized, and occupied (Brandt 1980, pp. 126–27).41 Pueblo communities learned to be on guard as Spanish missionaries sought to convert Indians; the U.S. government tried to suppress Indigenous ways of being; tourists and traders consumed Pueblo culture; and anthropologists collected ritual objects and recorded esoteric knowledge.

Vine Deloria, Jr., Gregory Cajete, and many others Indigenous thinkers explain that dominant (meaning Western, colonial, European, or Anglo American) ways of knowing are, in many ways, antithetical to the epistemic values held by Indigenous peoples.42 Many Indigenous communities protect and preserve certain knowledge by keeping it secret. In contrast, the Western institutions, as typified by the academy, are theoretically premised on the idea that knowledge should be freely accumulated, recorded, and widely shared. Jim Enote, CEO of the Colorado Plateau Foundation and former director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center, explains why his community finds these assumptions problematic:

This position is held by most Pueblo communities, including San Ildefonso, which have a long and fraught history with anthropology—a field that historically had a particular lust for seeking out and sharing esoteric information. As Simpson (2007, p. 69) writes, anthropology marks a colonial space of “knowing and contention with serious implications for Indigenous peoples”.People outside have the idea that knowledge should be shared. That’s what universities are built around. But at Zuni we don’t think that way. Some knowledge should be protected and not shared. There are things in Zuni you can know, and things you can’t. And there are certain people who deserve to be the keepers of that knowledge. It’s a privilege, and the rest of us respect them for that.43

It has been long acknowledged that the field of anthropology emerged alongside and was spurred by colonization (Lewis 1973, pp. 581–91; Fowles and Mills 2017). Scientists believed they had the right to study Indigenous peoples and to freely collect their cultural material for the sake of science and posterity. In the name of science, archaeologists disrupted and mined Indigenous ancestral sites in the Southwest, which were labeled as “abandoned”—rhetoric long used by colonial powers to justify claiming Indigenous spaces. Many early anthropologists in the Southwest collected Indigenous antiquities with reckless abandon—sometimes with the help of Native individuals, but rarely with the consent of the entire community—sending cartloads of objects to newly formed museums throughout the United States. Archaeologists also unearthed human remains, claiming as them as “specimens” for science.44 The history of anthropology can, thus, be understood as a history of scientific colonialism, whereby data (knowledge and objects) was extracted from colonized peoples for the benefit of the colonizer (Lewis 1973, pp. 583–85).

Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century anthropologists were working within the paradigm of salvage ethnography.45 Operating under the assumption that the Indian would vanish, they aggressively collected objects, excavated ancient and historical Indigenous places, and pushed Indigenous informants for information. It was believed that sooner or later “authentic” Indians would pass away or assimilate. They could not be saved, but what could be salvaged was their culture. The future of the Indian was in the museum and the library. Hewett subscribed to these ideas throughout the 1910s, and it is an impulse that drove him to commission the Crescencio Set.46 (By the 1920s, after closely working with cultural modernists, Hewett changed his tune, and began to argue that Pueblo culture was thriving and was an important part of America’s cultural future.47)

The Crescencio Set also was the product of another anthropological impulse, one that developed in the American Southwest: Ethno-archaeology. According to Severin Fowles and Barbara Mills, in the 1870s and 1880s, anthropologists in the Southwest developed “distinctively Americanist understandings of archaeology as an ethnology of the past and of ethnology as a kind of archaeology of the present” (Fowles and Mills 2017).48 By 1900, Fewkes described this approach as “ethno-archaeology”. Fewkes conducted field research at Zuni and among the Hopi in the 1890s. While working with the Hopi in 1899–1900, Fewkes hired four Hopi men to create hundreds of images of contemporary Katsinam, or ancestral beings, in the hopes of augmenting his archaeological findings at the ancestral Hopi site of Awat’ovi. The drawings, which were published in 1903 by the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology, became known as the Codex Hopiensis (Fewkes 1969).49 Hewett likely had Fewkes’ ethno-archaeological Codex Hopiensis in mind when he commissioned the Crescencio Set.50

As was archaeology, ethnographic research was understood by Pueblo communities as invasive and threating. Anthropologists pushed informants for protected knowledge and published these secrets. Many also published gross misinformation about Pueblo customs. Informants were often nervous about sharing information and typically did so in secret away from the community. If their communities found out what they were doing, informants could face scrutiny or punishment. Anthropologists knew this, but persisted, putting their informants (and sometimes themselves) at risk in the name of science.51 To give one example, as Hopi people learned of the images of Katsinam being created for Fewkes, they asked Fewkes to see them. At first, he shared the images freely hoping to gather more information about Katsinam, but as news about the images spread, their makers became the subject of speculation about sorcery (a grave accusation, see Chavez 2001, pp. 66, 91–92) and gossip (a powerful mode of social control among Puebloan peoples, see Chavez 2001, pp. 29–30, 86–93). Many Hopi saw the images and their makers as a threat, and these concerns hampered work on the project, according to Fewkes. Fewkes blithely dismissed the fears as the result of some Hopis’ lack of intelligence, and he was able to convince a few of the artists to continue representing Katsinam, knowing it jeopardized their safety (Fewkes 1969, pp. 15–17).

The reasons Pueblo informants shared information with anthropologists varied widely. Some genuinely worried about the future of their communities and saw in Western graphic practices a new route to cultural preservation, a position most common among informants who had attended government-run boarding schools or who lived away from their home communities.52 Some traditionalists, who understood that certain esoteric information was not meant to be shared, worked with anthropologists anyway because they were in dire poverty. Pueblo informants were paid, providing a much-needed source of income as settlers and U.S. law seriously eroded Pueblo subsistence structures. Sharing esoteric knowledge was dangerous, but starvation was a more imminent threat. Many informants were willing to risk the repercussion of working with ethnographers because, as anthropologist Charles Lange bluntly put it in 1959, it was “‘easy’ money” (Lange [1959] 1968, p. 35). Anthropologists used this fact to their advantage. Fewkes’ fieldnotes indicate that he paid Hopi artist-informant Homovi a dollar per day to create drawings at regular intervals for three months. This was a considerable sum of money for a Hopi laborer in 1899. For comparison, a man who chopped wood and carried water for Fewkes made just over two dollars per week (Munson 2006, pp. 73, 83).

Hopi and Northern Pueblo informants could have little imagined the damage they would do to their communities, as scholar Cynthia Chavez Lamar (San Felipe Pueblo) has argued with respect to those who worked with Fewkes (Chavez 2001, p. 26). Publications by Frank Hamilton Cushing and Fewkes drew other anthropologists to the Southwest, who also coerced sensitive information. In addition, anthropological publications about Pueblo cultural practices opened the door to everything from a U.S. government crackdown on supposedly lascivious and barbaric ceremonial practices to the further exploitation of Pueblo communities by anthropologists, tourists, and curio dealers. Lomayumtewa C. Ishii (Hopi) points out that the cultural archive amassed by Fewkes and other anthropologists continues to “perpetuate intellectual colonialism over Hopis” today (Ishii 2002, p. 33).53

The research of Matilda Coxe Stevenson serves as a prime example of how much harm could come of anthropological research. Stevenson had done fieldwork among the Zuni since the late 1870s. By the 1880s, summaries of her fieldwork appeared with frequency in the Bureau of Ethnology’s Annual Report, including tales of whipping of children and brutal and forcible initiations into religious societies.54 By the twentieth century, Stevenson reported that Tewa people were sacrificing women and babies to propitiate snakes as part of a ritual, a claim repeated in local and national newspapers. Stevenson’s claims were publicly rejected by both anthropologists and government officials who worked in the Southwest, but the damage was done.55 The news fed public biases against the “barbarism” of Indians, and was a factor in government investigations into supposedly “lascivious” and “immoral” Pueblo ceremonies in 1915 and 1920. These investigations, in turn, led the Office of Indian Affairs to persecute Pueblo religion as justified by the Religious Crimes Code of 1883. Commissioner Charles Burke tried to put a stop to Pueblo ceremonials and to prohibit Pueblo leaders from withdrawing students from Indian schools for ritual training.56 This is just one example of many that led Vine Deloria, Jr. to provocatively argue that “behind each policy and program with which Indians are plagued, if traced completely back to its origin, stands the anthropologist” (Deloria 1988, p. 81).

It is worth noting that anthropologists did not see themselves as conquering the lands and peoples they studied. In fact, many, including Frank Cushing and Hewett, were outwardly critical of colonial injustice and violence and of the nation’s history of imperialism.57 Nevertheless, the discipline was made possible by and helped to reiterate colonial economic and political control over Indigenous peoples. As ironically, the justification many anthropologists cited for emptying Indigenous communities of objects was the preservation of dying cultures, and yet in many places, so much was taken that anthropologists arguably did as much as Spanish conquistadors and U.S. government agents to disrupt the continuance of important Indigenous ceremonial, social, and aesthetic traditions.58 Potter Maria Martinez leveled this exact criticism at anthropologists in the 1920s. Anthropologist and artist Kenneth Chapman asked her to replicate a “butterfly” design from San Ildefonso pottery, to which she reportedly replied, “Why, Mr. Chapman. You ought to do better than we can, because you have been taking all our old pottery away from us and making pictures of it, and then sending it away, and we can’t remember any of the old designs.”59

Modern Pueblo painting developed in a context in which Pueblo culture, past and present, was being intensely studied and collected by anthropologists. As noted, most first-generation painters from San Ildefonso worked for anthropologists as day laborers well before they turned to painting on paper. Since at least 1908, almost a decade before he created paintings and tiles for Hewett, Crescencio work at Hewett’s excavations and his experience as an archaeological laborer informed how he handled Hewett’s 1917 commissions.

4. Ethno-Archaeological Labor

When Hewett was President of the New Mexico Normal School from 1898 to 1903, he was a proponent of hands-on learning. During these years, he and his students excavated on the Pajarito Plateau, located northwest of Santa Fe in the Jemez Mountains, and surveyed and collected in Chaco Canyon, a Puebloan ancestral site in northwest New Mexico.60 As was a common practice among archaeologists, Hewett hired Indigenous (and Hispanic) men to help him and his students excavate sites. When the School for American Archaeology was founded in 1907, Hewett was chosen by the Archaeological Institute of America to be the school’s first director. (The School for American Archaeology became the School of American Research in 1917 and the School for Advanced Research in 2007.61 As Hewett organized field schools for the Institute, he continued to rely on Indigenous labor for excavations, including at Puyé, a Santa Clara Pueblo (Kha’po Owingeh) ancestral site, and at Tyuonyi in El Rito de Los Frijoles, which is part of the Pajarito Plateau (Snead 2001, pp. 87–88, 141; Elliott 1987, p. 16).

Crescencio worked for Hewett at Tyuonyi as early as 1908. Hewett hired him again around 1910, as well as in 1915 and 1917 when Crescencio was a laborer at Otowi. Crescencio almost certainly worked for Hewett other years too.62 Hewett likely initially hired Pueblo men because he saw them as cheap labor, but over time he came to view these laborers as doubly useful owing to their knowledge of Pueblo ancestral and historical sites.63 By 1904, Hewett explained in the journal American Anthropologist that he was gathering valuable ethnographic information from Tewa workmen, praising the help of “Wajima” (Weyima, also known as Antonio Domingo Peña), whom Hewett described as the “head man” of San Ildefonso Pueblo (Hewett 1904, pp. 629–30).64

Pueblo communities did not willingly comply with anthropologists’ archaeological or ethnographic desires. Hewett learned this the hard way. In 1907, he wanted to excavate at Puyé, an extension of the Santa Clara reservation. One aim of the expedition was to fill Charles Lummis’s new Southwest Museum in Los Angeles with “swag”, as Hewett called his finds.65 Before settling on Puyé, Hewett and Lummis weighted whether to excavate there or at El Rito de los Frijoles. They decided to focus on Puyé because the permits would be easier to get. Securing permits for “the Rito” required permission from the Forestry Department, which put cumbersome restrictions on what anthropologists could do. Because Puyé was on reservation lands, permission was secured through Secretary James R. Garfield of the Department of the Interior, which came quickly and without restrictions. The fourteen-person Tewa labor force for the project, who were paid a dollar a day, was arranged through Superintendent of Indian Schools, Clinton J. Crandall.66

Even if Crandall had worked with Santa Clara’s governor to find laborers, the community clearly was not fully aware of the nature of the excavation, which targeted burial mounds.67 Santa Clara laborers were anxious about the work they were doing, and within the first week of the excavation, a delegation from the pueblo arrived to protest the dig. This tension was not uncommon. Many anthropologists in the Southwest documented Native laborers’ discomfort when digging, particularly when human remains were found. Disrupting sacred sites and the dead could bring calamity to a community. Many believed that their pueblos were paying the price of working with anthropologists with the health of their people, crops, and livestock.68

Despite Santa Clara’s concerns, the dig at Puyé continued (Snead 2001, pp. 88–89). It is unclear if and how Hewett appeased Santa Clara leaders. It is possible the pueblo simply had no recourse in the matter. It is also possible that Santa Clara leaders imposed stipulations on Hewett, which he was compelled to accept in order to conscript Santa Clara labor. One factor that may have led Santa Clara to work with Hewett in order to allow the excavation to continue was the income laborers brought into their community. As the son of a Hopi man who labored at Awat’ovi—a place with a traumatic history—recalled, “My dad always said he knew it was wrong [to dig there], but he needed the money to feed his family.”69

After 1907, and certainly by 1910, Hewett seemed to understand that he had to work with Pueblo governors to secure labor for his excavations. (Hewett also worked with pueblo governors when securing day labor for the Museum of New Mexico.) Hewett often sought workers from Jemez, San Ildefonso, and Santa Clara, all of which are near excavation sites, and he eventually cultivated a decent working relationship with the latter two pueblos. Letters between Hewett and governors at San Ildefonso and Santa Clara indicate that the governors decided who could go work for Hewett and for how long.70 Bruce Bernstein ventures that one strategy governors may have used to protect sensitive knowledge from archaeologists was to regulate who they allowed to work at excavation sites.71 Governors likely sent men who would use discretion when sharing information and could steer anthropologists away from particularly sensitive sites. A number of Tewa men who had experience working for Hewett were leaders in their pueblos, including Weyima of San Ildefonso and Julian Santiago Naranjo, Governor of Santa Clara.72

As a laborer for Hewett’s ethno-archeological endeavors, Crescencio would have learned and become well versed in tactics of refusal, passing down this knowledge to younger artist and laborers, including Awa Tsireh. I have shown that Crescencio brought these lessons to his art. He also brought them to his pottery design. His ana-ethnographic tiles, thus, offer another example of the visual tactic of refusal.

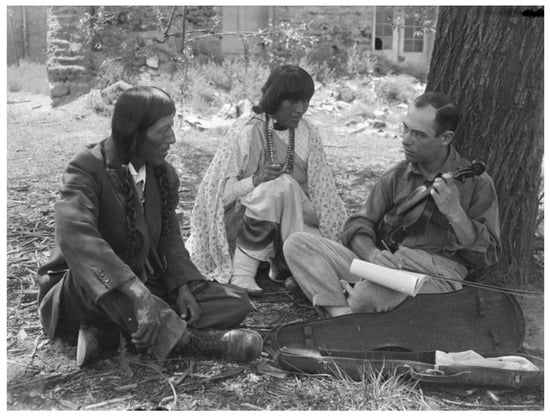

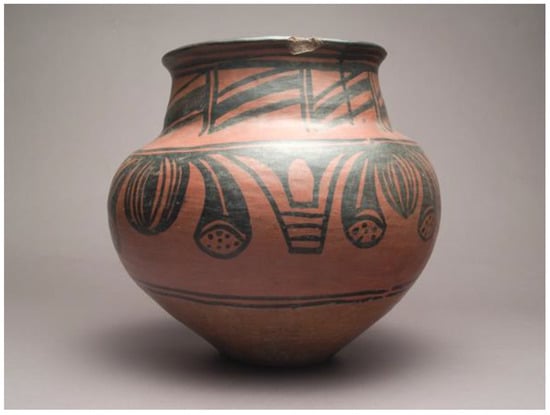

5. Crescencio’s Tiles

Early on in their relationship, Hewett learned that Crescencio was a skilled pottery designer. Crescencio collaborated with many female relatives, including his wife Maximiliana (Figure 7), known as “Anna”, and his mother Dominguita Pino Martinez, to create pottery (Figure 8).73 (His wife is the sister of potter Maria Martinez.) By 1913, Hewett was inviting Crescencio and Anna to give demonstrations of pottery making at the Palace of the Governors; and in 1915 Crescencio was among the artisans from San Ildefonso, including Julián and Maria Martinez, who gave demonstrations and sold their wares at the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego.74 Notably, many men who designed pottery would go on to become first-generation modern Pueblo painters, including Alfredo Montoya, Crescencio Martinez, Julián Martinez, and Awa Tsireh (Brody 1997, p. 19).

Figure 7.

Photograph of Crescencio Martinez and Maximiliana Martinez, no date (before 1918). Kenneth Chapman Collection, School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe, NM, AC02.861.2e.

Figure 8.

Dominguita Pino and Crescencio Martinez, Jar, 1905–1910. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 12229/12.

Crescencio’s dual talents in creating designs on pottery and figures on paper led Hewett to an unusual commission in 1917: A series of square clay tiles (Figure 2 and Figure 9). According to El Palacio, which was published under the supervision of Hewett, the “plaques” represent “Indian dance figures” (El Palacio 1918), although two of the tiles feature matching headdresses for a game animal dance. Crescencio must have made the tiles in collaboration with an accomplished potter, perhaps his wife. Square flat tiles are time-consuming and very difficult to make. The shape can become irregular when fired, they can curl and crack, and hidden air bubbles can explode. While the production of tiles was common among Hopi-Tewa potters by the early twentieth century, Crescencio’s tiles are among earliest known to be made at San Ildefonso.75

Figure 9.

Crescencio Martinez, Tile, c. 1917–1918. Courtesy of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, NM, 18755/12.

Crescencio’s tiles are distinct from the Hopi tiles in a crucial way. The first tiles made for curio dealers by Hopi-Tewa potters were painted with geometric designs, birds, and floral designs, but by 1890 Hopi tiles predominantly represented Katsinam (Messier and Messier 2007, pp. 25–26).76 This may have been Hewett’s primary reason for commissioning the tiles from Crescencio; perhaps he thought the medium would lead the artist to represent Katsinam. It did not. As Zena Pearlstone explains, Hopi and Northern Pueblo communities have differing views about the representation of these entities. Among the Hopi, painting and carving Katsinam for the market is permissible, although controversial. In contrast, most Northern Pueblos prohibit the representation of Katsinam for outsiders and restrict who can make and look at them, whether carved or visualized in two dimensions.77 Crescencio’s tiles do not represent Katsinam. The tiles, like Crescencio’s paintings, represent dancers and paraphernalia the public could see during summer and winter ceremonials. These ana-ethnographic tiles, like the Crescencio Set, thus, deploy tactics of refusal in order to guard against scientific colonialism.

Modern Pueblo painting blossomed in the early 1920s when its market dramatically grew. As it did, Pueblo artists expanded their style and subject matter. Patrons increasingly celebrated Pueblo paintings as aesthetically important, and yet this art was still understood as having ethnographic value and as offering a window into Pueblo life. Even after Hewett and other anthropologists ceased to be a major patron of the genre, modern Pueblo painters continued to build on the tactics of refusal they honed while creating their early ana-ethnographic paintings. These paintings offered a model for how twentieth-century Pueblo painters could declare the legitimacy of their culture on their people’s own terms. Ana-ethnographic Pueblo paintings are a testament to Pueblo visual sovereignty.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Thanks Joseph (Woody) Aguilar and the cultural advisors at San Ildefonso Pueblo for reviewing the images published in this paper and giving me consent to reproduce them. I am also grateful for conversations with Diane Bird, Jonathan Batkin, Amy Lonetree, and Bruce Bernstein, which helped shape this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, Tony E., Stacy Holman Jones, and Carolyn S. Ellis. 2015. Autoethnography: Understanding Qualitative Research. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Paula Gunn. 1990. Special Problems in Teaching Leslie Marmon Silko’s ‘Ceremony’. American Indian Quarterly 14: 379–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Paula Gunn. 1991. Grandmothers of the Light: A Medicine Woman’s Sourcebook. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anthes, Bill. 2006. Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandelier, Adolph F., and Edgar L. Hewett. 1973. Indians of the Rio Grande Valley. New York: Cooper Square Publishers. First published 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Bruce, and W. Jackson Rushing, III. 1995. Modern by Tradition: American Indian Painting in the Studio Style. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Mary Ellen. 2008. A Life Well Led: The Biography of Barbara Freire-Marreco Aitken, British Anthropologist. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boast, Robin. 2011. Neocolonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited. Museum Anthropology 34: 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, Elizabeth A. 1980. On Secrecy and the Control of Knowledge: Taos Pueblo. In Secrecy: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Edited by Stanton K. Tefft. New York: Human Sciences Press, pp. 123–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, J.J. 1971. Indian Painters and White Patrons. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, J.J. 1997. Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico, 1900–1930. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, James F. 2016. Mesa of Sorrows: A History of the Awat’ovi Massacre. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Michael F. 2003. Who Owns Native Culture? Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, Brian Yazzie. 2004. What the Coyote and Thales Can Teach Us: An Outline of American Indian Epistemology. In American Indian Thought: Philosophical Essays. Edited by Anne Waters. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, Gregory. 1994. Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education. Durango: Kivaki Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, Gregory. 2000. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Heewon. 2008. Autoethnography as Method. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Kenneth M. 1916. Graphic Art of the Cave Dwellers. El Palacio 3: 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Katherin L. 2002. Indian Painters of the Southwest: The Deep Remembering. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, Cynthia L. 2001. Negotiated Representations: Pueblo Artists and Culture. Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Science Monitor. 1931. American Indian Paintings. Christian Science Monitor, December 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, James. 1986. Introduction: Partial Truths. In Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Edited by James Clifford and George E. Marcus. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, James. 1988. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, James, and George E. Marcus, eds. 1986. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, Chip. 2017. Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip. 2010. Living Histories: Native Americans and Southwestern Archaeology. Lanham: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip. 2011. Sketching Knowledge: Quandaries in the Mimetic Reproduction of Pueblo Ritual. American Ethnologist 38: 451–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, V.F. 2004. Approaches to Native American Philosophy. In American Indian Thought: Philosophical Essays. Edited by Anne Waters. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, Edward S. 1926. The North American Indian. Norwood: Plimpton Press, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- D., B.P. 1942. Indian Artists Visit Museum. El Palacio 49: 128–29. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, Vine, Jr. 1988. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, 2nd ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, Vine, Jr. 1994. God Is Red: A Native View of Religion. Golden: Fulcrum Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, Vine, Jr. 2004. Philosophy and the Tribal Peoples. In American Indian Thought: Philosophical Essays. Edited by Anne Waters. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, Vine, Jr., and Daniel R. Wildcat. 2001. Power and Place: Indian Education in America. Golden: Fulcrum Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K. 1989. Interpretive Biography. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Margretta S. 1936. Their Culture Survives. Indians at Work 3: 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dillingham, Rick. 1994. Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dobkins, Rebecca J. 1997. Memory and Imagination: The Legacy of Maidu Indian Artist Frank Day. Oakland: Oakland Museum of California. [Google Scholar]

- Dobkins, Rebecca J. 2000. Art and Autoethnography: Frank Day and the Uses of Anthropology. Museum Anthropology 24: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, Edward P. 1970. The Pueblo Indians of North America. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- DuFour, John. 2004. Ethics and Understanding. In American Indian Thought: Philosophical Essays. Edited by Anne Waters. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Dorothy. 1951. The Development of Modern American Painting in the Southwest and Plains Area. El Palacio 58: 331–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Dorothy. 1955. America’s First Painters. National Geographic Magazine 107: 349–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Dorothy. 1968. American Indian Painting of the Southwest and Plains Areas. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Bertha P. 1942. Alfredo Montoya—Pioneer Artist. El Palacio 49: 143–44. [Google Scholar]

- El Palacio. 1918. Art of Crecencio Martinez. El Palacio 5: 59. [Google Scholar]

- El Palacio. 1919. Museum Chronology. El Palacio 6: 135. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson, Laura L., and Carolyn Ellis. 2008. Autoethnography as Constructionist Project. In Handbook of Constructionist Research. Edited by James A. Holstein and Jaber F. Gubrium. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 445–65. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Melinda. 1987. The School of American Research: A History, the First Eighty Years. Santa Fe: School of American Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autobiography. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn S., and Arthur Bochner. 2000. Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject. In The Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 733–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An Overview. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101108 (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Fewkes, Jesse Walter. 1969. Hopi Katchinas Drawn by Native Artists, Smithsonian Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report, 1903. Glorieta: Rio Grande Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles, Severin, and Barbara J. Mills. 2017. On History in Southwest Archaeology. In The Oxford Handbook of Southwest Archaeology. Edited by Severin Fowles and Barbara J. Mills. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Aaron. 2008. Local Knowledge and Art Historical Methodology: A New Perspective on Awa Tsireh and the San Ildefonso Easel Painting Movement. Hemisphere: Visual Cultures of the Americas 1: 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Jacob. 1970. Ethnographic Salvage and the Shaping of Anthropology. American Anthropologist 72: 1289–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Marsden. 1920. Red Man Ceremonials: An American Plea for American Esthetics. Art and Archaeology 9: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, Edgar L. 1904. Archeology of the Pajarito Park, New Mexico. American Anthropologist 6: 629–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, Edgar L. 1909. The Excavations at El Rito De Los Frijoles in 1909. American Anthropologist 11: 651–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hewett, Edgar L. 1916. America’s Archaeological Heritage. Art and Archaeology 4: 257–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, Edgar L. 1918. Crescencio Martinez—Artist. El Palacio 5: 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, Edgar L. 1922. Native American Artists. Art and Archaeology 13: 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Highwater, Jamake. 1976. Song from the Earth: American Indian Painting. Boston: Little, Brown and Company for the New York Graphic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Highwater, Jamake. 1986. Controversy in Native American Art. In The Arts of the North American Indian: Native Traditions in Evolution. Edited by Edwin L. Wade and Carol Haralson. New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with Philbrook Art Center, pp. 223–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, F.W. 1924. Rites of the Pueblo Indians: F. W. Hodge Denies There Is Anything Revolting or Immoral About Them and Attributes Reports to the Indians’ Desire to Fool the Whites. New York Times, October 26, X12. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, Jessica L. 2015. A Cloudburst in Venice: Fred Kabotie and the U.S. Pavilion of 1932. American Art 29: 54–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Lomayumtewa C. 2002. Hopi Culture and a Matter of Representation. Indigenous Nations Studies Journal 3: 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Margaret D. 1996. Making Savages of Us All: White Women, Pueblo Indians, and the Controversy over Indian Dances in the 1920s. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 17: 178–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Margaret D. 1999. Engendered Encounters: Feminism and Pueblo Cultures, 1879–18934. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jantzer-White, Marilee. 1994. Tonita Peña (Quah Ah), Pueblo Painter: Asserting Identity through Continuity and Change. American Indian Quarterly 18: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabotie, Fred, and Bill Belknap. 1977. Fred Kabotie, Hopi Indian Artist: An Autobiography Told with Bill Belknap. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona with Northland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Lawrence C. 1983. The Assault on Assimilation: John Collier and the Origins of Indian Policy Reform. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, Charles H. 1968. Cochiti: A New Mexico Pueblo, Past and Present. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Diane. 1973. Anthropology and Colonialism. Current Anthropology 14: 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucic, Karen, and Bruce Bernstein. 2008. In Pursuit of the Ceremonial: The Laboratory of Anthropology’s ‘Master Collection’ of Zuni Pottery. Journal of the Southwest 50: 1–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, Luke. 1988. History of Prohibition of Photography of Southwestern Indian Ceremonies. In Reflections: Papers on Southwestern Culture History in Honor of Charles H. Lange. Edited by Anne V. Poore. Santa Fe: Ancient City Press, pp. 238–72. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau, Joel. 2001. Autoethnography and Material Culture: The Case of Bill Reid. Biography 24: 242–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeough, Michelle. 2009. Through Their Eyes: Indian Painting in Santa Fe, 1918–1945. Santa Fe: Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. [Google Scholar]

- Messier, Kim, and Pat Messier. 2007. Hopi and Pueblo Tiles: An Illustrated History. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mihesuah, Devon A. 1998. Natives and Academics: Researching and Writing about American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Angela L., Janet C. Berlo, Bryan J. Wolf, and Jennifer L. Roberts. 2007. American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Barbara J. 2002. Acts of Resistance: Zuni Ceramics, Social Identity, and the Pueblo Revolt. In Archaeologies of the Pueblo Revolt: Identity, Meaning, and Renewal in the Pueblo World. Edited by Robert W. Preucel. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley-Tanaka, Jeannette L. 2002. Crossed Cultures, Crossed Meanings: The Manipulation of Ritual Imagery in Early Historic Pueblo Resistance. In Archaeologies of the Pueblo Revolt: Identity, Meaning, and Renewal in the Pueblo World. Edited by Robert W. Preucel. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Morell, Virginia. 2007. The Zuni Way. Smithsonian Magazine. April. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-zuni-way-150866547/ (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Munson, Marit K. 2006. Creating the Codex Hopiensis: Jesse Walter Fewkes and Hopi Artists, 1899–1900. American Indian Art Magazine 31: 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Akiko. 2011. Who Owns the ‘De-Aboriginalised’ Past? Ethnography Meets Photography: A Case Study of Bundjalung Pentecostalism. In Ethnography and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge. Edited by Yasmine Musharbash and Marcus Barber. Canberra: Australian National University, pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, Alfonso. 1969. The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being, and Becoming in a Pueblo Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, Alfonso. 1972. Ritual Drama and the Pueblo World View. In New Perspectives on the Pueblos. Edited by Alfonso Ortiz. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 135–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, Alfonso. 1994. The Pueblo. Edited by Frank W. Porter, III. New York: Chelsea House. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, Triloki Nath. 1972. Anthropologists at Zuni. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 116: 321–37. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Elsie Clews. 1939. Pueblo Indian Religion. 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstone, Zena, ed. 2001. Katsina: Commodified and Appropriated Images of Hopi Supernaturals. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstone, Zena. 2011. Hopi Doll Look-Alikes: An Extended Definition of Inauthenticity. American Indian Quarterly 35: 579–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, David W., and Lisa A. Roberts. 1999. America’s Pueblo Artists: Encounters on the Borderlands. In Native American Art in the Twentieth Century. Edited by W. Jackson Rushing, III. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Ruth B. 1998. Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Ruth B. 1999. Nuns, Ladies, and the ‘Queen of the Huron’: Appropriating the Savage in Nineteenth-Century Huron Tourist Art. In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds. Edited by Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1986. Fieldwork in Common Places. In Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Edited by James Clifford and George E. Marcus. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. Arts of the Contact Zone. Profession 1991: 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reed-Danahay, Deborah. 1997. Introduction. In Auto/Ethnography: Rewriting the Self and the Social. Edited by Deborah Reed-Danahay. Oxford: Berg Publishers, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard, Jolene. 1995. Sovereignty: A Line in the Sand. Aperture 139: 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard, Jolene. 2011. Visualizing Sovereignty in the Time of Biometric Sensors. South Atlantic Quarterly 110: 465–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushing, W. Jackson, III. 2018. Generations in Modern Pueblo Painting: The Art of Tonita Peña and Joe Herrera. Norman: Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma. [Google Scholar]

- Sando, Joe S. 1992. Pueblo Nations: Eight Centuries of Pueblo Indian History. Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Fe New Mexican. 1915a. Human Sacrifice Tale Groundless Says F. C. Wilson. Santa Fe New Mexican, May 3. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Fe New Mexican. 1915b. All Imagination Says Lonergan, of Human Sacrifice by the Pueblo. Santa Fe New Mexican, April 23. [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf, Gregory. 2000. Pueblo Indian Pottery: 750 Artist Biographies, C. 1800–Present. American Indian Art Series; Santa Fe: CIAC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Sascha. 2013. Awa Tsireh and the Art of Subtle Resistance. Art Bulletin 95: 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Sascha. 2015. A Strange Mixture: The Art and Politics of Painting Pueblo Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. 1911. Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: For the Year Ending June 30, 1914; Washington, DC: Washington Government Printing Office.

- Seymour, Tryntje Van Ness. 1988. When the Rainbow Touches Down: The Artists and Stories Behind the Apache, Navajo, Rio Grande Pueblo and Hopi Paintings in the William and Leslie Van Ness Denman Collection. Phoenix: Heard Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Audra. 2007. On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship. Junctures 9: 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life across the Borders of Settler States. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Snead, James E. 2001. Ruins and Rivals: The Making of Southwest Archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spinden, Herbert J. 1930. Indian Artists of the Southwest. International Studio 95: 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Tilly E. (a pen name for Matilde Coxe Stevenson). 1887. The Religious Life of the Zuñi Child. In Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1883–1884. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Government Printing Office, pp. 533–55. [Google Scholar]

- Suina, Joseph H. 1992. Pueblo Secrecy: Result of Intrusions. New Mexico Magazine 70: 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, Jill D. 2004. Dances of the Tewa Pueblo Indians: Expressions of New Life, 2nd ed. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, Zoltán Gendler. 2017. Compositionality. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/compositionality/ (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Tanner, Clara Lee. 1973. Southwest Indian Painting: A Changing Art, 2nd ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Nicholas. 1994. Colonialism’s Culture: Anthropology, Travel and Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warrior, Robert Allen. 1995. Tribal Secrets: Recovering American Indian Intellectual Traditions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Washington Post. 1915a. Human Sacrifices, She Says, Are Still Offered by Tewa Indians. Washington Post, January 18, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Washington Post. 1915b. Human Sacrifices by Indians: Tewas Offer up Women and Children in Rites. Says Mrs. Stevenson. Washington Post, April 17, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, Tisa. 2009. We Have a Religion: The 1920s Pueblo Indian Dance Controversy and American Religious Freedom. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, Peter. 1993. The End of Anthropology (at Hopi)? Journal of the Southwest 35: 125–57. [Google Scholar]

- Whitt, Laurie Anne. 1995. Indigenous Peoples and the Cultural Politics of Knowledge. In Issues in Native American Cultural Identity. Edited by Michael K. Green. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 223–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, L.L.W. 1917. This Year’s Work at Otowi. El Palacio 4: 87. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, L.L.W. 1918. In Memoriam: Crescencio Martinez. El Palacio 5: 33. [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff, Lydia L. 1996. Vision and Voices: Native American Painting from the Philbrook Museum of Art. Tulsa: Philbrook Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Twenty paintings from the Crescencio Set can be identified at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC) in Santa Fe. MIAC also houses at least twelve tiles by Crescencio, which can be dated by a reference to them in (El Palacio 1918). On the commission, also see (Hewett 1918). |

| 2 | On the meaning and significance of Pueblo ceremonial dances, see (Ortiz 1972, pp. 35–161; 1969; Sweet 2004). |

| 3 | Alfredo Montoya sold paintings to outsiders at least as early as 1911, as will be discussed later in this paper. Montoya, Awa Tsireh, and Tonita Peña are among the painters who attended the San Ildefonso Day School. Students were encouraged to draw and paint images of Pueblo life by teachers Esther Hoyt (1900 to 1907) and Elizabeth Richards (1909 and after). The role school teachers played in fostering modern Pueblo painting has been well documented (Dunn 1968, pp. 201, 204–5; Tanner 1973, pp. 67, 84; Bernstein and Rushing 1995; Brody 1997, pp. 37–40, 82–83; McGeough 2009, pp. 17–41). |

| 4 | Elizabeth DeHuff encouraged a handful of students to paint ceremonial dances in early 1919 and first exhibited the paintings at the school’s library in early March 1919; see letter from Elizabeth DeHuff to her mother, 11 March 1919, Elizabeth Willis DeHuff Family Papers, 1883–1981 (MSS99), Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico (hereafter CSWR), box 10, folder 25. Hewett was taken with the show and opened an exhibition of the paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts on 29 March 1919; see (El Palacio 1919). The Museum of Fine Arts, which is part of the Museum of New Mexico, was dedicated in 1917. |

| 5 | On patronage and national exhibitions and markets, see (Brody 1971, 1997). On international exhibitions, see (Horton 2015). |

| 6 | Notably, first-generation painter Tonita Peña did not work for Hewett as a laborer, almost certainly because of her gender. She was born at San Ildefonso and moved to Cochiti in 1905 after the death of her mother. She asked Hewett if she could live and work at the museum in 1921, but her request was denied. See letters from Peña to Lansing Bloom, 19 September 1921 (box 4, folder 4) and Bloom to Peña, 26 October 1921 (box 4, folder 5), Edgar L. Hewett Collection, Fray Angélico Chávez History Library, Santa Fe, New Mexico. |

| 7 | These concerns and acts of resistance are well documented and are discussed later in this paper with respect to the Hopi and Santa Clara communities. For other examples, see (Pandey 1972; Lucic and Bernstein 2008, pp. 11, 14–19, 33–41; Colwell 2017, pp. 17–18, 23–24). |

| 8 | On “scientific colonialism”, see the landmark essay (Lewis 1973, pp. 583–85). Anthropology’s rootedness in colonialism has been widely discussed, including in (Clifford and Marcus 1986; Clifford 1988; Thomas 1994; Smith 1999; Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2010). |

| 9 | Hewett (1922, p. 110) argues that Pueblo paintings are of ethnographic (and aesthetic) interest. Reflecting on her reasons for asking her Native students to paint, DeHuff wrote, “eight years ago after seeing my first Indian ceremonial, enthusiasm demanded that I secure a reproduction of it in colors. However, how could such a thing be had? After days of pondering, I canvassed the rooms at the Santa Fe Indian School for children, who showed especial aptitude for drawing and crayon coloring”; see Elizabeth DeHuff, “American Primitives in Art”, unpublished manuscript, Elizabeth Willis DeHuff Family Papers, Center for Southwest Research, box 6, folder 3. In a similar vein, Tanner (1973, pp. 133–34) wrote that the fine details Tonita Peña’s paintings make them “the same excellent ethnological records that are the case with so much of this [Pueblo] Indian art”. Brody (1997, p. 157) writes that Awa Tsireh’s early paintings for Hewett were objective, descriptive, and “ethnographically detailed”, arguing that the artist moved to a more subjective mode as he matured, a claim Brody extends to other Pueblo painters too (189). |

| 10 | Velino Shije Herrera quoted in “Well-known Indian Painter Thanks to Dr. Edgar Hewett”, The Santa Fe New Mexican, 19 December 1944, 2. Kabotie quoted in (Kabotie and Belknap 1977, p. 44). Similar statements by twentieth-century Pueblo artists can be found in (Seymour 1988, pp. 147, 162–63, 168). |

| 11 | On “autoethnography” with respect to Pueblo painting, see (Penney and Roberts 1999, pp. 23, 25, 27; Anthes 2006, p. 4; Rushing 2018, p. 5). The term is also used in broader scholarship about Indigenous visual and material culture, including (Phillips 1999, p. 34; 1998, p. 17; Ono 2011, pp. 64–65; Martineau 2001; Dobkins 1997, p. 15; 2000). |

| 12 | Emphasis original to the text. She previously defined the term in (Pratt 1991, pp. 35–36). |

| 13 | On autoethnographic representation as oppositional and a mode of resistance, see (Pratt 1991, pp. 35–36; 1992, p. 9). She offers many specific examples throughout both texts. Not all scholars emphasize this aspect of Pratt’s concept. For example, Rushing (2018, p. 5) describes the work of Tonita Peña as “auto-ethnographic, as they reflect a keen awareness of, and appreciation for, the desire of Euro-American anthropologists to collect (images of) traditional culture”. Miller et al. (2007, p. 500) defines “auto-ethnography” as a practice through which modern Pueblo painters and Plains ledger artists narrated “their own cultural ways during the same period anthropologists were writing ethnographic accounts of their culture”. Just as the fraught nature of Prattian autoethnography is sometimes dampened, so too is Pratt’s concept of the “contact zone”, as is discussed in (Boast 2011). |

| 14 | Pratt (1992, p. 7) writes “a third and final idiosyncratic term that appears in what follows is ‘autoethnography’ or ‘autoethnographic expression’”. |

| 15 | On autoethnography as a research method, see (Denzin 1989, pp. 27–48; Reed-Danahay 1997, pp. 1–9; Ellis 2004; Ellingson and Ellis 2008, pp. 445–65; Chang 2008; Ellis et al. 2011; Adams et al. 2015). |