1. Introduction

In 2014, the architectural conservator Anja Premk and the author of the present article, prompted by the director of the France Stele Institute of Art History in Ljubljana, Barbara Murovec, undertook a thorough re-examination of the available sources on the building history of Maribor synagogue. This resulted in the publication of a pocketbook in Slovenian entitled “Maribor Synagogue” (

Premk and Premk 2015), which, although classified as a professional rather than an academic or research text, presented the building history of the synagogue through the ages, scrutinizing the aims of the conservation efforts in the 1990s and proposing our vision of the earliest building phases.

1 In a 2018 article entitled Maribor Synagogue Re-examined, I reviewed the preservation history of the building in the last century (

Premk 2018) and pointed out some of the dubious conclusions regarding several aspects of the conservation led by the principal chief conservator Janez Mikuž in the 90 s. The actions of the Maribor Regional Office of the Institute for Protection of the Cultural Heritage in Slovenia (IPCHS) included conservation, reconstruction and reinterpretation of the building. The more we delved into the renovation history of the synagogue, the more we were convinced of the veracity of our initial assumption that there was a lack of coordination and cooperation between the project staff involved in the various aspects of its conservation.

2 The confusion of the project staff from the outset was pointed out unequivocally by Ruth Ellen

Gruber (

2002, p. 119): “Some of the initial work was carried out hurriedly and incorrectly, in accordance with local, uninformed ideas of what was Jewish and how a synagogue should look, and was going to have to be removed–including the women gallery”.

3In spite of the more or less substantial alterations of the space through the centuries of later Christian and secular use, Maribor synagogue still remains one of the few preserved medieval Jewish architectural landmarks in the wider European context. Its preservation succeeded thanks to its transformation into the Church of All Saints at the end of the 15th century, after the expulsion of Jews from Styria. The consecration of former synagogues into churches was common practice in Catholicism, with minimal rearrangement required: only the

bimah (elevated reading table) had to be removed and the

Aron Kodesh (the sacred closet with Torah scrolls) replaced with an altar mensa (

Paulus 2007, p. 549). In Slovenia, there are two other (well-documented) instances of such a transformation (the medieval synagogues in Ljubljana and Ptuj)—neither of which survived because of neglect and decay (

Hajdinjak 2013;

Valenčič 1992).

The main goal of the present article is to point out and interpret the evidence we have so far on the earliest, medieval stages of the building. Unfortunately, our search for the material remains of additional building elements, uncovered during reconstruction and well-documented photographically, as well as in existing documentation, was fruitless. Some of the material is, we assume, stored in the Regional Museum of Maribor (

Premk 2018, p. 79, cit. n. 44.) and in the premises of the IPCHS Maribor. Nevertheless, a re-evaluation of the IPCHS documentation and revision of the historical sources have produced fresh insights into the building history and point to the outstanding development of its building structure, almost unparalleled in medieval European synagogue architecture.

The last two decades have seen significant advances in studies of Jewish Architecture in Europe, which has been supplemented by the publication of previously unknown or lesser-known historical sources (

Borský 2007;

Harck 2014;

Klein 2017;

Kravtsov and Levin 2017;

Paulus 2007; et al.). This is also true of the history of the medieval Jewish community in Maribor and its synagogue (

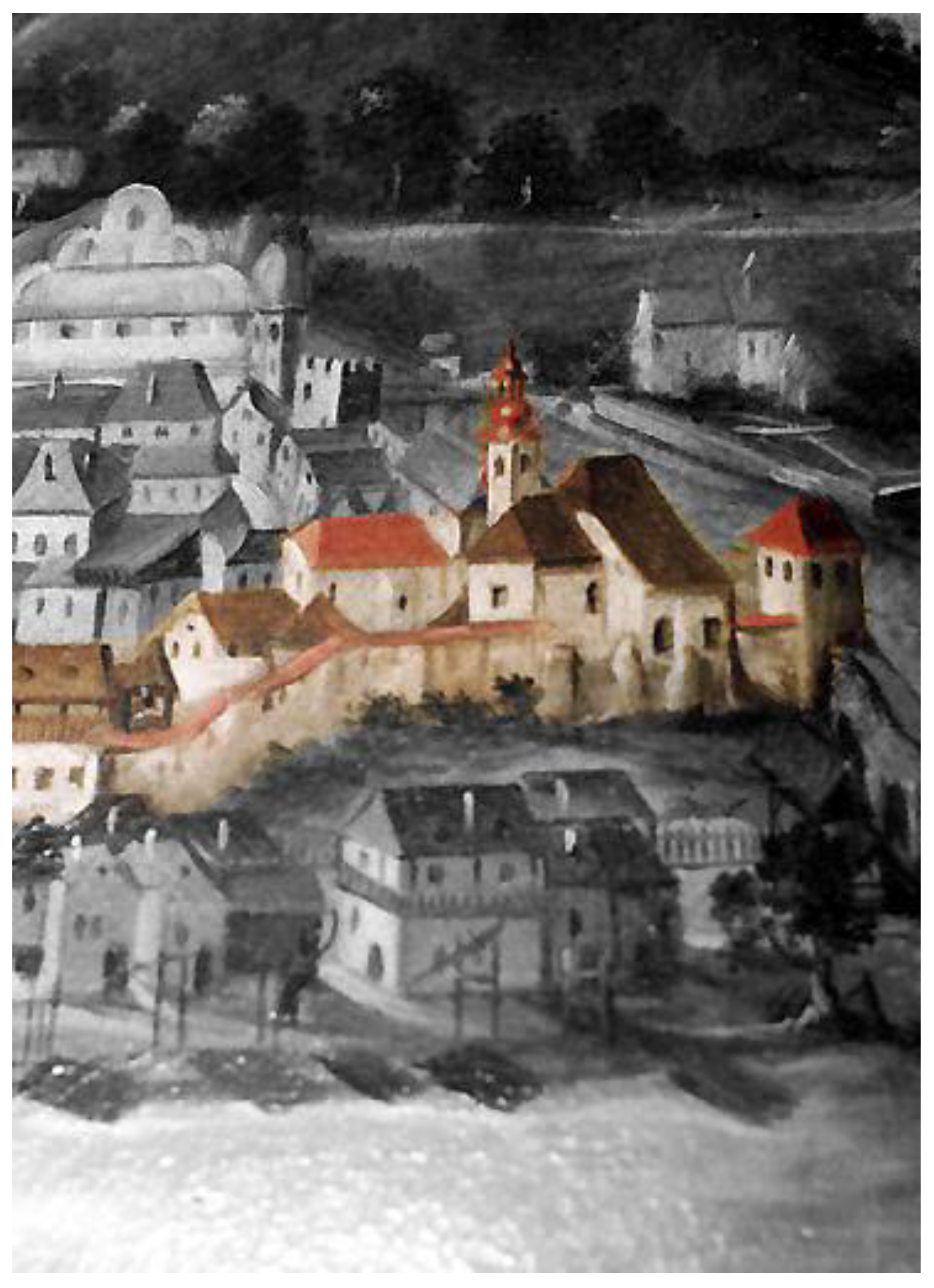

Figure 1).

2. Historical Sources and Their Significance

In addition to the abundant archival sources relating mostly to the financial aspects of Jewish life, the

responsa literature written by Rabbi Israel Isserlein and his disciples provides an invaluable cultural resource on the history of the medieval Jewish community in Maribor and the surrounding areas (

Eidelberg 1962;

Gradivo za Zgodovino Maribora 1975–2019). There are a number of sources, with varying degrees of reliability, which mention the synagogue as well as other communal buildings.

Jews can be traced in Maribor from the second half of the 13th century (

Germania Judaica 1968, p. 522, n. 4).

4 The general assumption is that the Jewish community in Maribor originates from that period; however, the two archival sources referring to their existence do not indicate whether they were actually settled in Maribor at that point. According to Vladimir Travner, the Jewish quarter in Maribor was recorded for the first time in 1277, but he does not reveal his source (

Travner 1935, p. 155). Although tempting (

Paulus 2007, p. 202), it is not possible to confirm the existence of either the Jewish community or the synagogue before the first half of the 14th century on the basis of the archival documents alone.

At first, the specialist literature mentioned 1190 as a post quem date for the synagogue, since it supposedly leaned on the outer wall of the town wall dated to 1190 (

Gruber and Gruber 2000, p. 146). However, between 1255 and 1275, the town acquired a four-sided town wall, which delineated approx. 25 hectares of a rhombus-shaped area (

Sapač 2013). The sides of the rectangle are almost entirely straight; the only deviation arises on the south side, especially in the eastern section which includes the synagogue. Here, the terrain to which the wall was adjusted descended steeply towards the Drava River (

Figure 2).

The archival documents do not mention Maribor synagogue before the middle of the 14th century. Until recently, it was assumed that the earliest reliable source was an announcement from 1429 proclaiming “in der stat Marpurg in der sinagog” (

Mlinarič 1996, p. 8;

Toš 2016, p. 57).

5 Yet the synagogue is mentioned in the sources at least twice before—first in a document dated 4 November 1354 kept in the Austrian State Archives (Österreichische Staatsarchiv) in Vienna, and second in (or after) 1421, when after the Wiener Gesera, the massacre of Jews, Rabbi Anshel Marburg (also Marpurk) (

Brugger 2006, p. 68) arrived in town. In the

aron hakodesh (Torah ark), he found a letter by a Jerusalem scholar from the third quarter of the 14th century addressed to Austrian “scholars” (

Germania Judaica: 1350–1519 2003, pp. 835, 842, fn. 89;

Grossmann 1977, p. 195, fn. 36).

6The document from 1354 is invaluable not only because it mentions Maribor synagogue for the first time but also because it explains its wider role for Christians (

Brugger 2006, pp. 159–60, No. 782). In the document, a Maribor town judge Nikolaj Pezolt, Maribor Jewish judge

7 Wilhelm, and a Maribor resident Paltram stated that they were called upon by the messengers of the Count of Pfannberg to go together to

Judenshul (synagogue). There, they ordered the

shamash (also:

shulklapper,

messner—the synagogue’s caretaker) to ask the Jews whether there was anyone among them who had a promissory note from the Count of Pfannberg. None of the (Maribor) Jews, however, had one. The

shamash then declared that all the notes which the (Maribor) Jews had presented from the revocation onwards were invalid (

Brugger and Wiedl 2010, p. 160).

8It is necessary to add that the role of the

shamash was not confined to taking care of the synagogue (lighting the menorah and hannukiah candles), but also knocking on doors and summoning the members of the community to everyday prayers, and also taking part in various matters of the Jewish commune, e.g., tax affairs, Jewish court, authentication of documents. Thus, he was a messenger of religious and general affairs. The

shamash and the

hazzan were present everywhere synagogues existed, and both roles are specifically mentioned in the

responsa referring to Maribor and Judenburg (

Brugger 2006, p. 50;

Jelinčič Boeta 2009, pp. 374–75).

It is also possible to infer from the document that Christians had no reservations about visiting the synagogue; it was also accessible to them, as the building was not exclusively Jewish but also functioned as a public space.

9 Significantly, one of the

responsa mentions three or four special seats reserved for Christian guests in Maribor Synagogue (

Joseph bar Moshe 1903, p. 31).

10The reading of announcements, public documents, and promissory notes in Maribor Synagogue is also mentioned in other documents. In 1429 Gregor Schurff presented his confirmatory document/charter in synagogues in Graz, Wiener Neustadt, Judenburg, Hartberg, Voitsberg, Bad Radkersburg, Sankt Veit an der Glan and Maribor, and in 1445 the Lamberger document was introduced in Maribor, Bad Radkersburg, Judenburg, Sankt Veit an der Glan and Ljubljana (

Rosenberg 1914, p. 13).

In 1477, Emperor Frederick III issued a document stating that the rabbi from Radgona erases the fine of 12 florins that David from Maribor had to pay for the construction of the Jewish school (

Judenshul) there, as he would no longer be living in the town. In this case, the reference is to the synagogue and not to the separate construction of a Jewish school (

Beth Midrash) as had previously been presumed in the literature (

Jelinčič Boeta 2009, p. 278). The term

Judenshul in the legal documents of medieval Austria always denotes a synagogue (

Keil 1998). This is a single document referring to the building of a synagogue in Maribor and is therefore of immense value. In this case, as shown in the section dealing with the building phases later in this article, construction most probably refers to the rebuilding of a (damaged) synagogue (

Figure 3).

The medieval Jewish community in Maribor ceased to exist after the expulsion of Jews from Styria in 1497 (

Mlinarič 2000, p. 26).

11 The synagogue and appertaining buildings were purchased by a wealthy Maribor couple, Barbara and Bernardin Druckher, soon after. The last late medieval mention of the synagogue concerns its transformation into All Saints church. In a 1501 founding letter for the All Saints benefice, Druckher orders a daily mass service: “

in vunser aufgebauthen khirchen und capeln, so zu Mahrburg gelegen, die vor zeiten ain sinagog der Juden gewesen…“ (

GZM 1985, No. 8).

12 It is impossible to conclude from this passage whether the former synagogue was rebuilt, expanded, rearranged or built entirely anew (

Figure 4). The building must have functioned as a church before 1501, probably soon after being purchased by the couple after the 1497 expulsion of the Jews (

Mlinarič 1996, p. 39). In most similar cases, only minor spatial alterations were carried out (

Paulus 2007, p. 549).

3. Archaeological Research

Thorough archaeological research of medieval synagogues is in many cases a precondition for the clarification of a building’s history. Until recently, the main issues facing researchers concerned the methodological shortcomings of medieval archaeology as well as the ownership of the buildings. Since the renovation of the Maribor Synagogue in the 1990s, a noteworthy step forward has been made in the research of medieval Jewish synagogue architecture and archaeology (synagogues,

mikvehs,

Talmud school, cemeteries), particularly in France, Germany, and Austria (

Harck 2014;

Paulus 2007;

Synagogen, Mikwen, Siedlungen Jüdisches Alltagsleben im Lichte Neuer Archäologischer Funde 2004).

13 Archaeological research could also offer answers to the numerous questions related to the (presumed) locations of medieval synagogues in Slovenia; however, Slovene archaeology has paid little attention to the high and late Middle Ages. To date, only Maribor Synagogue has been the focus of archaeological research (

Mikuž 1994).

14 Without the owners’ consent, the law does not allow any interventions into buildings, especially when they are not subject to monument protection.

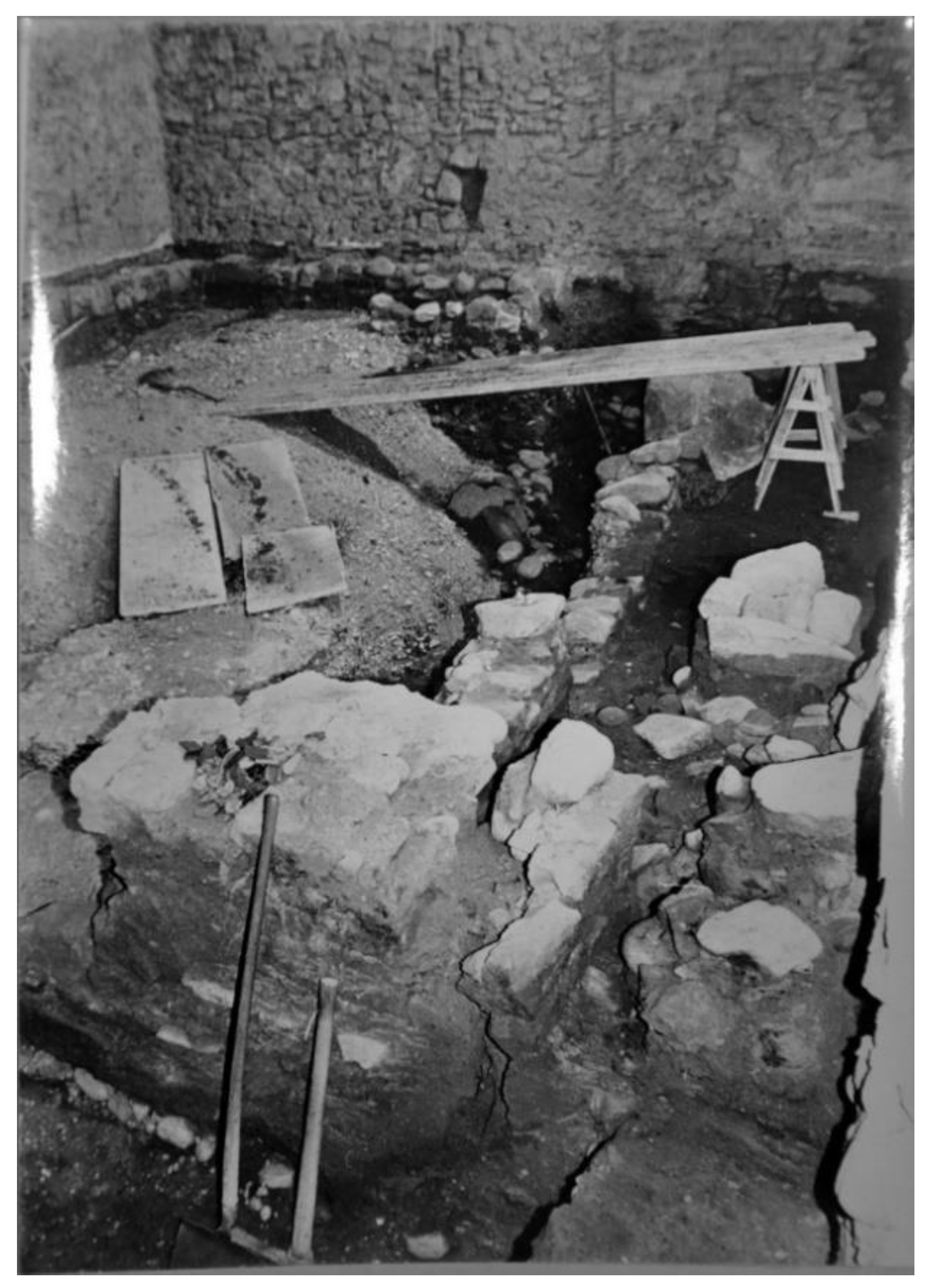

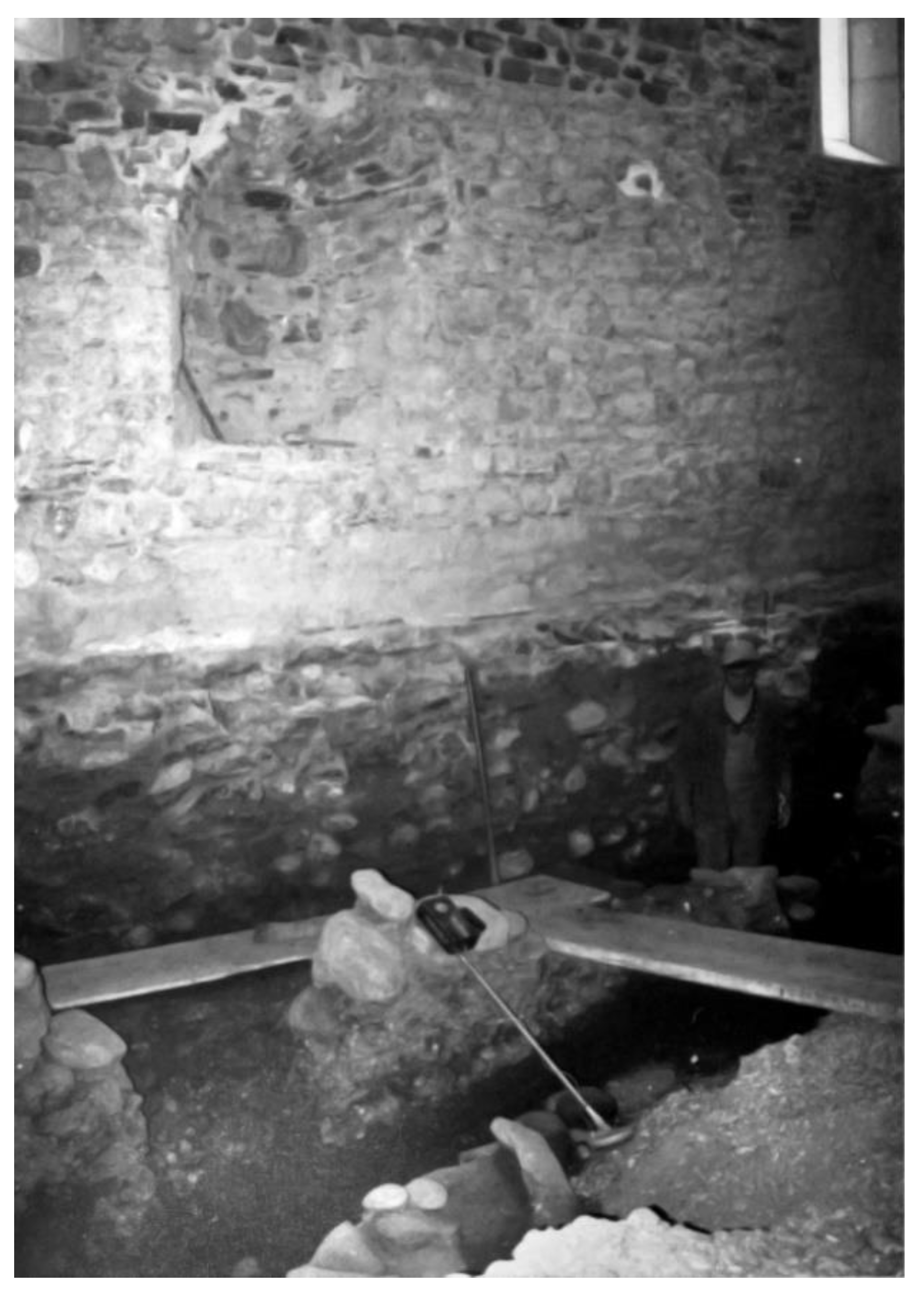

The need for archaeological supervision quickly arose during work on the Maribor Synagogue building, which was followed by protective archaeological excavations under the leadership of Ivan Tušek. Research was carried out in the main hall, in the area north and west to it, as well as along the outer section of the eastern façade (

Figure 5). The results were published in two separate reports, but there is some inconsistency between the two and a lack of thorough analysis and exact documentation of the architectural findings (

Mikuž 1994,

1999). Aware of the insufficiencies in the archaeological excavation, Marjan Teržan, chief restorer, suggested leaving a section of the synagogue floor covered by wooden beams, which could easily be removed in the case of additional archaeological examination (

Figure 6).

15A recapitulation and critical reinterpretation of the archaeological examination carried out soon after the initiation of the works in 1992 are thus necessary to unearth the oldest building phases.

At first, after the removal of the ceramic floor, remnants of pebble stones, medieval and newer ceramic chards, and remnants of Gothic architectural stone elements (a piece of stone ornamentation, broken ribs made of sandstone, two large brick plates) were discovered in a half-a-meter deep layer, under a cement screed in the main hall (

Mikuž 1994, p. 6).

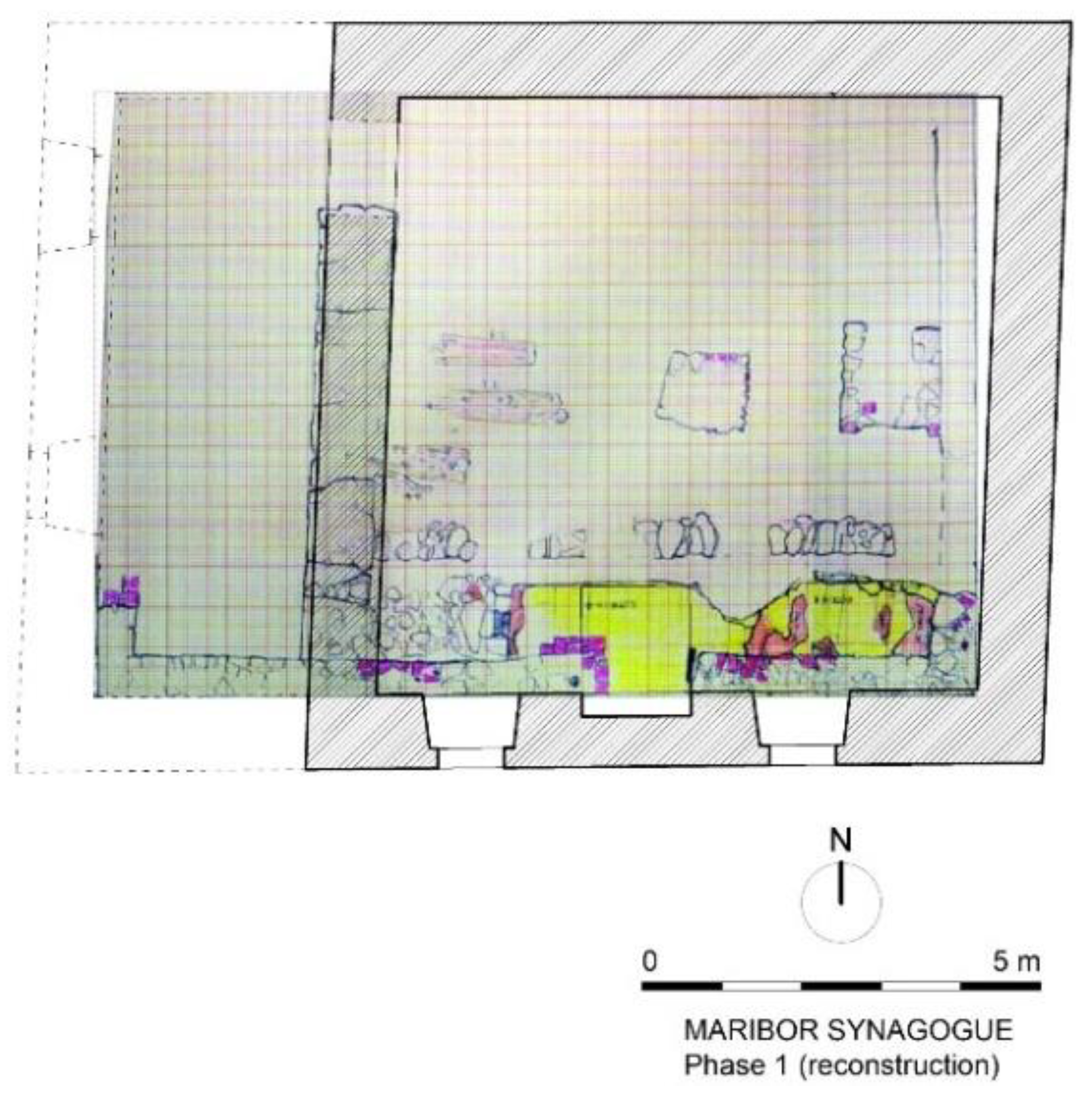

When the floors in the main hall were further deepened to the gravel and conglomerate layers, widened foundations made of larger quarry stones and bound by lime mortar made of fine sand appeared next to the northern, eastern, and southern walls. It was only pointed out in the first archaeological report in 1994 that these foundations, with the foundations lying north–south discovered on the western side, could have formed a smaller structure, probably the synagogue from phase one (

Figure 7). The research also showed that along the entire length of the southern side, the foundations are built in a uniform and even manner, and that it is thicker than the foundations on the remaining three mentioned sides. This means that the building leaned on the older town wall. The expanded inner foundations next to the northern and eastern side are only 30 cm wide and are younger, which is confirmed by the layer of ruins on which they were built (

Mikuž 1994, p. 6) (

Figure 8).

It is hard to understand why such an important finding—the foundations of a smaller space, which might even have functioned as the first synagogue—was omitted from the final conservation reports. We are convinced that the smaller space indeed predated the later expansions of the building. There is also solid evidence of its original, sacred function (

Premk and Premk 2015, p. 54).

Besides the foundations, fragments of small Gothic columns were also discovered (

Mikuž 1994, p. 7). The stone pieces of small Gothic columns, which were a constituent part of a

bimah, were found during the excavations of the former medieval synagogue in Vienna and belonged to the third phase of the building (

Heigert 2000, p. 192). But in the case of Maribor Synagogue, such an identification of the columns is mere speculation, since to our knowledge they were neither properly documented nor preserved.

A square stone foundation was uncovered in the central part of the hall. Based on the archaeological report, it was used as the base of a column in the church’s architecture (

Mikuž 1994). In the concluding conservation report, the conclusion about the late Medieval origin of the column was changed:

We expected to find the foundations of bimah, one of the most important parts of the synagogue furnishings, which was generally brick built, however, precisely in the place where, according to the analogy, the bimah should stand, a column of a later date, which supported the 19th century vaults, was standing.

In the 19th century, the room was used for secular rather than ecclesiastical purposes. The question arises as to whether a younger column could be leaning on an older foundation. It seems unusual that during the 19th century renovations, a foundation would have been made for only one of the two supporting columns of the vaults—the other was not found during archaeological investigations. Furthermore, the most common location of a

bimah would be in the middle of the space, as supported by

responsa literature and numerous analogies. However, it is true that in the case of a two-column division of the space, the

bimah might have been slightly shifted towards the eastern column (

Paulus 2007, p. 532).

The existence of a preserved foundation of the medieval column would support the assumptions about the possible division of the prayer room, something that was very common in synagogue architecture in the Middle Ages. Examples of medieval Ashkenazi synagogues in which the space was divided with one, two, or even three columns are known (

Paulus 2007, pp. 512–17). We believe that the foundation indeed supported one of the two medieval columns belonging to the second stage of the building (

Premk and Premk 2015, p. 43).

Also interesting was the discovery of a 140 cm × 110 cm large foundation next to the eastern wall of the hall (

Figure 9). In the adjacent wall, a niche for keeping the Torah scrolls in the synagogue (

Aron Kodesh) was found (

Mikuž 1994, p. 26). The new interpretation of the findings answers the question of this foundation. In the hall with two columns, the location of the console on the east wall would be in the upper part of the niche, thus, the niche for keeping the Torah had not yet existed at that time. The Torah Ark must have been of a different, free-standing type and was placed on an elevated landing; it was this foundation that was discovered (

Premk and Premk 2015, p. 43).

In the archaeological sketch of the findings, the southern wall can be seen, doubled by a parallel running narrower foundation approximately a meter to the north. It is made of dry stones from larger river pebbles, forming part of the protective wall. It protects the dry-stone foundation and the walking surface for the defenders on the inner side of the southern town wall. The surface is additionally confirmed by the discovery of the walled-in passage on the southeastern corner of the present eastern wall of the synagogue (

Mikuž 1999, p. 7) (

Figure 10). In the southwestern corner of the hall, a fragment of the embrasure of the original town wall-which was later split by a built-in elongated window-was visible (

Mikuž 1994, p. 2). It is possible that this part of the wall was built next to the Drava River for defense purposes, and therefore existed even before overall fortification of the settlement in the 13th century (

Sapač 2013). In this case, the building of the synagogue was not envisioned together with the construction of the original town wall, but could have been erected after a fire, traceable in the archaeological excavations. On the outer side of the eastern wall of the synagogue, at a depth of 3.5 m, a scorched layer and burnt wooden beams were found, along with a topsoil layer with remnants of human bones underneath it. The archaeological report mentions the possibility that these bones belong to the victims of a fire of a wooden roof construction, possibly set up for the defenders along the inner side of the town wall (

Mikuž 1994, p. 8).

It would be logical for the destroyed sections to have been restored as soon as possible, perhaps financed by private funds; in this case, Jewish money would have been welcome.

The structure of the southern wall of the façade shows at least two medieval construction phases. The older was built in straight even layers with partially carved stone elements, connected with lime mortar, while the younger phase, made of uneven layers, was put in place to repair the older one. The collapse could have happened because of damage to the defense system sustained during an attack, a fire or because of lack of maintenance (

Mikuž 1994, p. 8).

The later Christian use of the building is attested to by four skeletal graves which were found in the central part of the hall. These were not Jewish burials, potentially linked to the adjacent Jewish cemetery, since the deceased in the second grave had his hands folded on his stomach and a rosary wrapped around them. He died a violent death, as his skull was pierced with a sharp object. Next to one of the deceased, the bones of a child were found. Thus, the graves point to the former Christian use of the building (

Mikuž 1994, pp. 6–7). They might also be connected to the Turkish siege of Maribor in 1532 (

Mlinarič 2001). At that time the town wall had not yet reached the Drava, so the building stood right on the front line.

During the probation of the wall, an entrance portal made of grey sandstone was discovered on the west side of the hall, on the lower level. It was separated from the ground floor with three stairs (

Figure 11). It had a rod-shaped profile, a spiral scroll and was made in the late Gothic period (

Mikuž 1994, p. 1). The right side of the portal was sufficiently preserved so that reconstruction was possible, although the realization of the stairs lacks historic accuracy, as recorded by the chief restorer. There were spolia found on the lower area of the portal, dating to before 1400. Another fragment of a portal was discovered on the northern wall of the western extension, belonging to the last synagogue phase (

Mikuž 2000, pp. 164–65).

A small niche was also revealed in the eastern part of the southern wall; however, it was poorly preserved due to numerous reconstruction efforts (

Figure 12). Several reconstructions of the windows were visible in the southern wall of the hall, while two older reconstructions in stone were visible, although not the latest, Gothic one. Also intriguing are two arched-topped windows in the western wall of the western extension, which were wrongly identified as Romanesque and belong most probably to the initial phase of the extension hall (cf.

Mikuž 2000, p. 165).

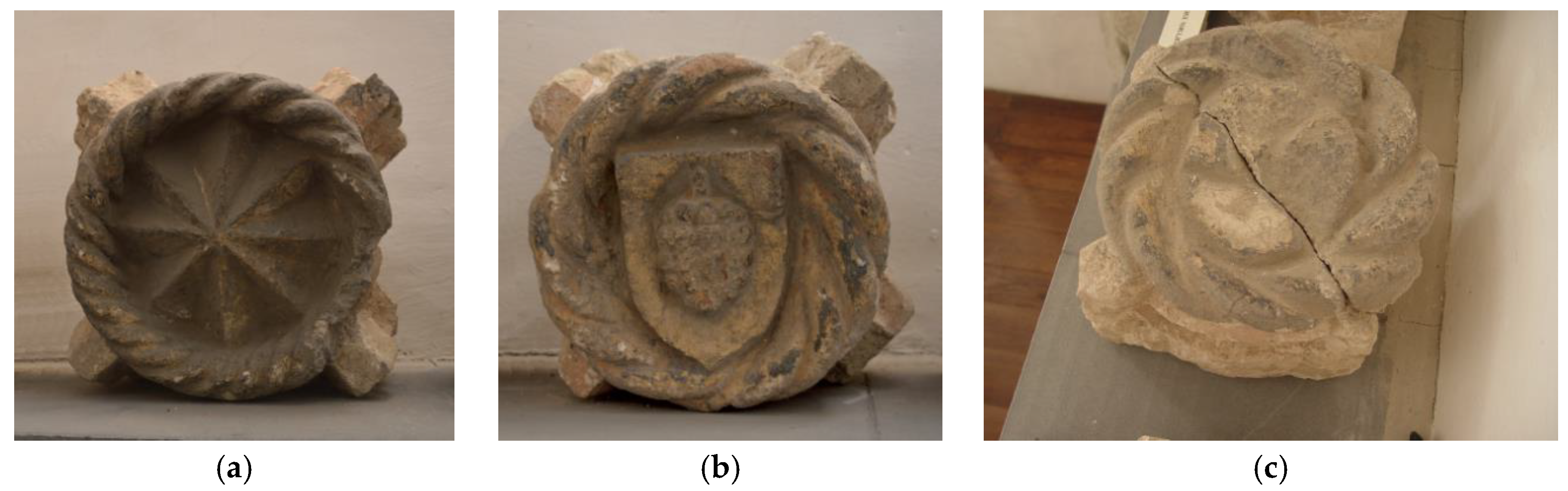

16Fragments of former vault bays, keystones and profiles of (door) frames, which were used as construction material in later reconstructions, were found during the probing of the building’s walls (

Figure 13).

17During examination of the ruins, part of a broken Jewish tombstone was found in the cave on the outer side of the northern wall of the building as were some other fragments on the excavation area.

18 It was probably shattered during previous construction efforts.

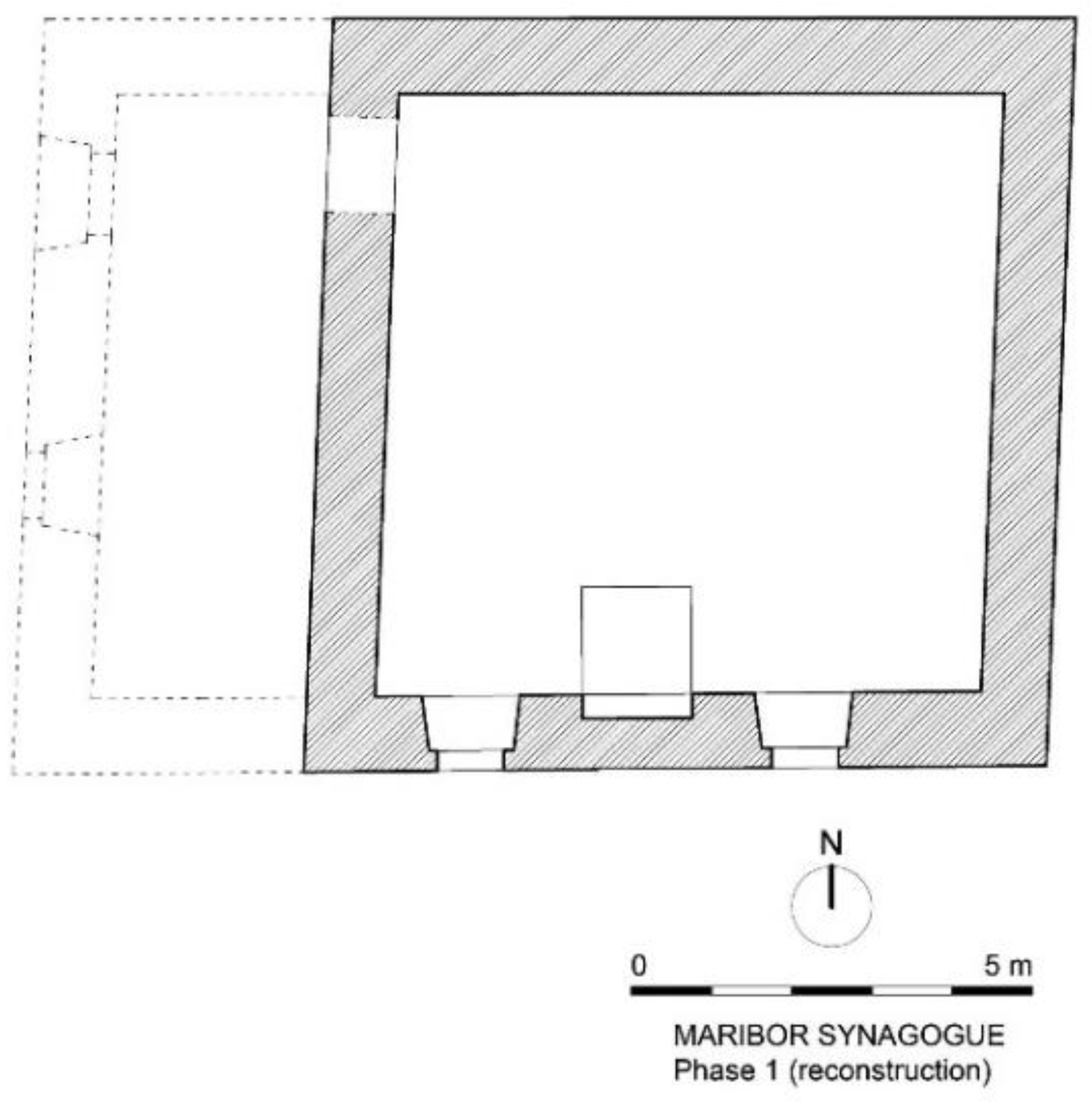

4. Medieval Phases of the Building

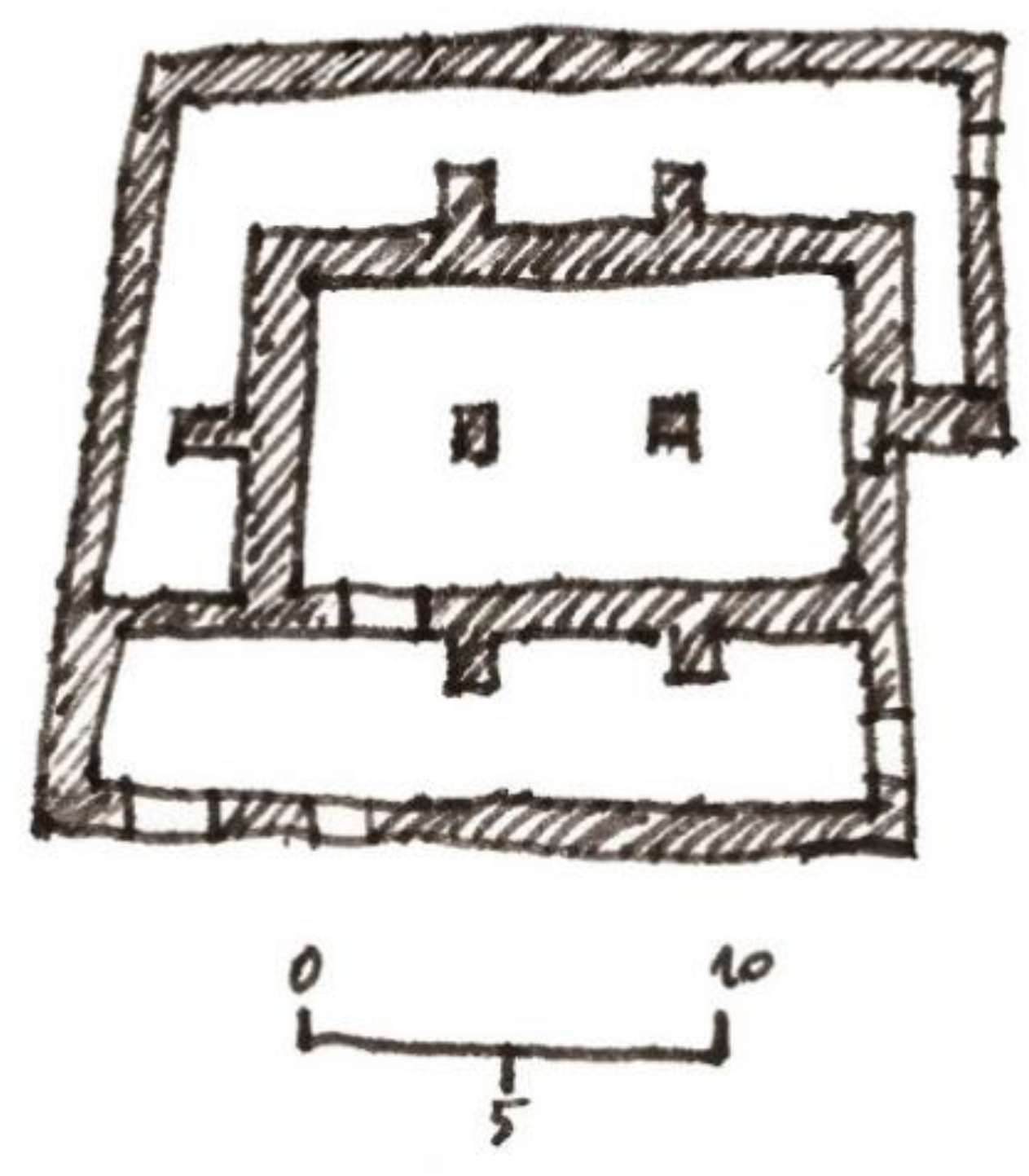

Based on archaeological findings only, it is evident that there were several construction phases, which had begun as early as the Middle Ages. Part of phase one are the foundations of the sacred space, which is 1/3 shorter than the reconstructed hall and concludes at the wall. This space is almost square (

Figure 14), although the sides do not meet at a precise right angle. The foundations lie north–south, however, enclosing an area of approximately 7.5 cm × 7.3 m (cf.

Paulus 2007, pp. 402–3). This includes the niche on the southern wall, located in the axis of the space. Bearing in mind that the niche belonged to the oldest medieval phase of the building, it was probably used for religious purposes. If the uncovered space was indeed the oldest phase of the synagogue, the niche could have functioned as a Torah Ark. This is further supported by a limestone screed with the imprints of the pavement, which was found during archaeological excavations, next to it. The screed extends to the niche, as documented in the archaeological sketch, and was probably the original (sub)pavement of the synagogue (

Premk and Premk 2015, p. 54) (

Figure 15). The southward orientation deviates from the common practice in this part of Europe of positioning synagogues eastward. This might have been because of the location of the oldest Jewish burial ground in Maribor, which supposedly adjoined the eastern side of the synagogue (

Mikuž 1994, p. 8).

19 Thus, the most sacred part of the synagogue was turned away from the cemetery, but still in the direction of Jerusalem, within a tolerated deviation. Based on the research, the windows also point towards two reconstruction phases before the last, Gothic one—there are traces of windows on the left and right of the niche. One would enter from the side, as is usual for a synagogue, probably from a built vestibule. It is possible to compare the ground plan of the first discovered phase of the synagogue with the first phase of the synagogue in Erfurt, dated between 1250 and 1270. The first synagogue in Judenplatz in Vienna (

Figure 16), dated around 1250, and the original synagogue in Rouffach (Alsace) (

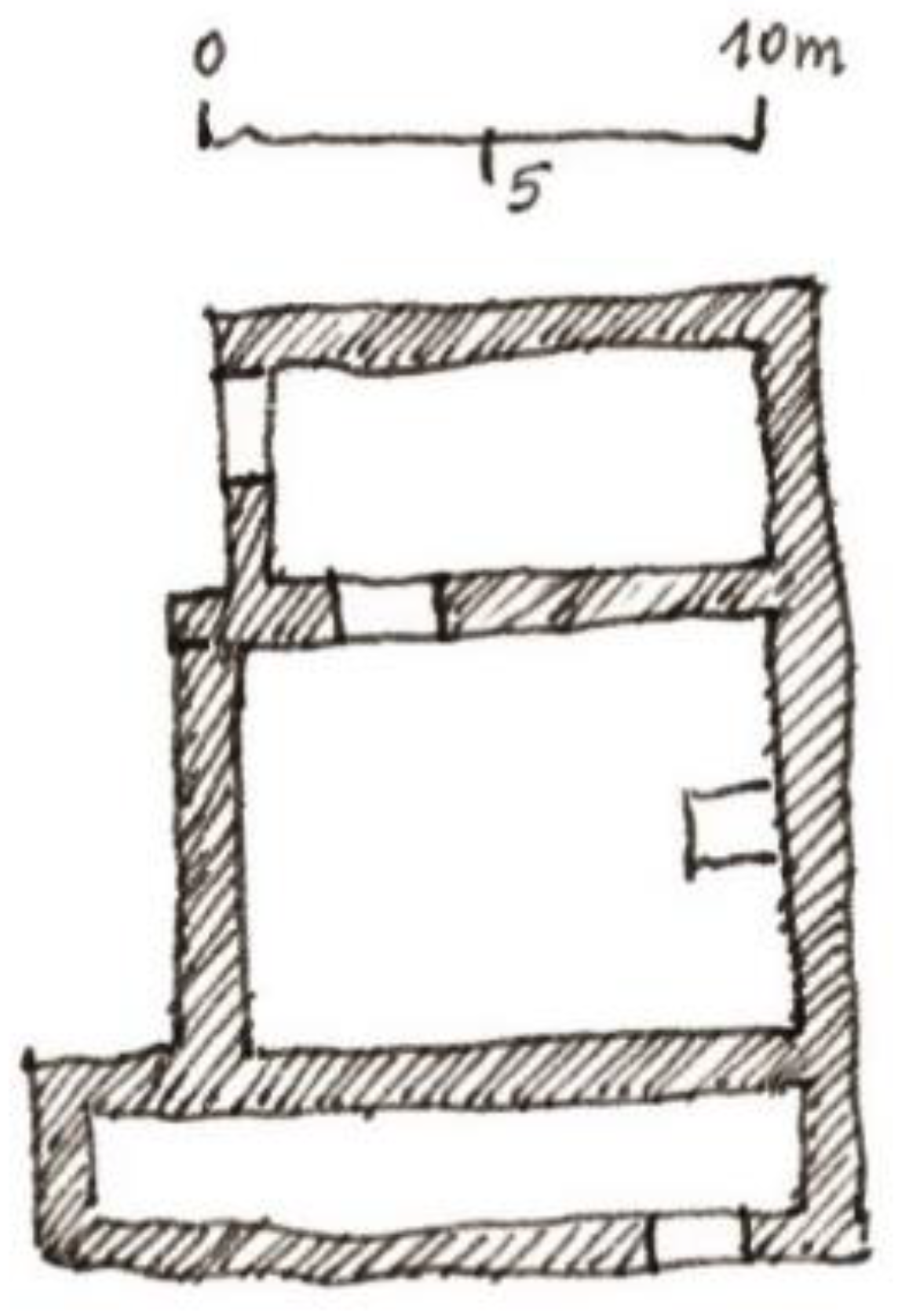

Paulus 2007, pp. 487–92, 515), which also stood next to a cemetery and was built ca. 1290, have almost a square ground plan as well. The first phase of the Maribor Synagogue could have been built in the last third of the 13th century, although there is insufficient historic evidence to support such an early date.

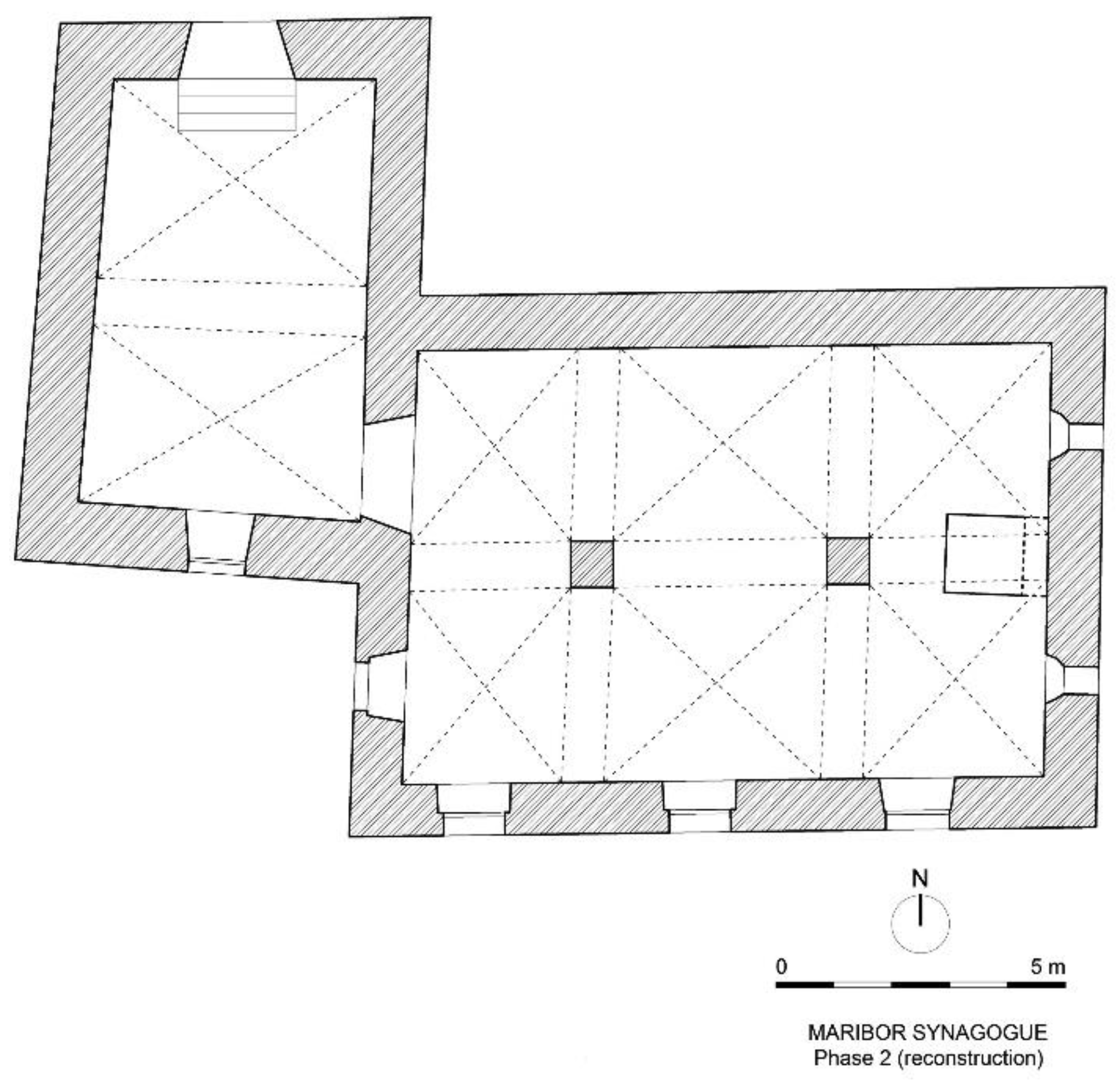

In the 14th century, the number of Jews in Maribor was growing, and the synagogue needed to be enlarged. In 1354, when it was first mentioned in the sources, the building had probably already been extended. The expansion is also connected to the abandonment of the cemetery next to the synagogue and the purchase of the land for the cemetery outside the city walls, first mentioned in 1367 (

Mlinarič 1996, p. 6). At that time it was possible to orientate the synagogue towards the east, and with the inclusion of the anteroom into the hall, it was possible to expand the synagogue by one third and thus obtain a ground plan ratio of 2:3 (

Figure 17). The western wall of the hall had to be demolished and a column was built on its foundations. Together with the second column—the foundation of which was uncovered through archaeological research—the space was divided, with a

bimah standing between the columns (

Figure 18). Based on the findings, the columns stood slightly further apart than the ideal thirds, which was not uncommon for the spatial organization of a synagogue (

Paulus 2007, pp. 512–17). The column supported the ceiling, which was divided into six square vault bays—at the top of which, three discovered wreath-rimmed keystones with an outset of perpendicular crossed ribs may have been placed (

Premk 2018, pp. 87–89). The identification of the three keystones as forming part of the same vault is additional confirmation of our two-column theory (

Figure 19). The outset angle of the two keystones with the grape is slightly different to the angle of the two others, which can be simply explained by the minimally dissimilar dimensions of the two middle bays (

Premk 2018, pp. 79–82). The reason it was initially assumed that they formed two different building phases is the fact that due to the perpendicular outset of the ribs, a three-bay division of the space would not have been possible. Besides, three additional keystones forming the vault of the three southern bays are missing. However, in the final conservation report, the possibility of a six-bay division of the vault, supported by two columns, was completely left out of consideration (

Premk 2018). The eight discovered consoles also correspond to this arrangement, however, the three outside buttresses do not, meaning that they were not yet built to their present height at that time. They were lower and perhaps extended much later because of the static demands of the new construction (

Premk 2018, p. 82).

20 Modifications of the southern wall are also visible from the archaeological sketch.

When the synagogue was turned towards the east, a new Torah Ark location had to be found. According to the construction of the vault, this area was not formed as a niche, which would have weakened the wall, but was instead freestanding—the foundation next to the east side attests to that. The windows were also rebuilt then for the first time—the discovered segments of the lancet windows could also belong to this phase (

Mikuž 2000, p. 164). When the hall was expanded, a new anteroom had to be built and was constructed on the western side. Numerous similar examples of synagogues from that time can be found in Europe. The most famous Old New Synagogue in Prague (last quarter of the 13th century) has an identical ground plan in a 2:3 ratio, divided by two columns, which also do not correspond entirely to the ideal thirds (

Paulus 2007, pp. 437–48) (

Figure 20). Two columns divide the synagogue space in Worms and in Judenplatz in Vienna (2nd phase, beginning of the 14th century) as well (

Heigert 2000) (

Figure 21).

The third construction phase or the rebuilding of the synagogue dates back to 1477, when the building of a Jewish school (

Judenshul) in Maribor is mentioned. The last synagogue phase is connected to extensive restoration work and arrangements on the town wall in and after 1465, resulting also in construction of the “Jewish tower” in 1477 (

Mlinarič 2000, pp. 54–55). The rebuilding was most likely carried out along with general fortification of the city wall (

Sapač 2013, p. 16), although there might have been additional reasons, such as a landslide, mentioned in the report on the archeological excavations (

Mikuž 1994), or weakening of the southern part of the synagogue wall, caused by the Baumkircher conquest of Maribor in 1469 (

Germania Judaica: 1350–1519 2003, p. 837, n. 13c).

The Jews had to also take care of the wall delimiting the southeastern section of the Jewish quarter. In this phase, the synagogue hall was rebuilt in the late Gothic style. The windows with a segmental arch and both of the discovered late Gothic portals could be placed in this phase, although there is a possibility that the portals were built when the synagogue was turned into a church, before 1500. The raising of the buttresses would have necessitated changes to the vault. We can presume that due to static, there is a possibility of a more elaborate, star-like vault, transmitting force to the walls in a more even manner. Maybe that is what the Maribor historian Rudolf Gustav Puff saw in the first half of the 19th century, when he mentioned “the richly ribbed stone vaulting of the ceiling, whose supporting stones emanate into finely chiselled stars” (

Puff 1847, p. 45). Nevertheless, the Gothic windows had already been changed before Puff’s writing, since he only saw “remains of four windows with a pointed arch, two rectangular and one rose window” (

Puff 1847, p. 45). A niche in the eastern wall was also discovered; by reconstructing the vault, it was possible to move the Torah Ark away into the wall, although it is difficult to discern the real proportions from the preserved documentation alone. There is serious doubt as to the dimensions of the reconstructed version, especially in relation to the height of the consoles supporting the vault, and dimensions of the windows, which must have been shorter during the synagogue phase (

Klein 2019). Besides, the two keystones with the outset of sharp-angle crossed ribs, used in the reconstruction of the main hall, might have been initially located in the entrance hall. Was the lack of the additional two keystones of the entrance hall the reason that the medieval cross ribbed vault was not reconstructed in spite of the entirely preserved medieval consoles? Because of the (late) Baroque reconstruction of the vault in the entrance hall, its medieval origin is nearly lost, in spite of the two preserved Gothic arched-topped windows and preserved consoles with the onset of the cross ribbed vault. Another question concerns the northern annex. If it at all existed in the medieval period, it probably was built during the last synagogue phase or later and consisted initially of a single floor. Since there are literally no material remains of a vault system, as described by the Maribor historian Puff, and the argumentation for the reconstructed version remains far from convincing, speculation about the last synagogue phase will have to be left out of future considerations. The same holds true for many other questions linked to the former synagogue in Maribor, such as the window and door positioning, the northern annex, which might or might not yet have been built in the last synagogue phase (if yes, it certainly must have consisted of a single and not two floors, as in the reconstructed version), the location of the bimah, and the location of women.