Mapping a New Humanism in the 1940s: Thelma Johnson Streat between Dance and Painting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. From Murals to Spirituals

The idea that the whole body of spirituals are ‘sorrow songs’ is ridiculous. They cover a wide range of subjects from a peeve at gossipers to Death and Judgment…There never has been a presentation of genuine Negro spirituals to any audience anywhere. What is being sung by the concert artists and glee clubs are the works of Negro composers or adaptors based on the spirituals.

3. Peculiar Motion: Streat’s Variation on Modern Dance

If ever there was a time when every race needs desperately to try to understand each other and to realize that—however different their cultures—their hopes and human needs, their pride and aspirations are the same, that time is now.35

4. A New Humanist Frequency

In assigning permanent gallery space to the Department of Dance and Theatre Design, the Museum indicates its significant interest in the theatre arts, and thus assures the public of a comprehensive policy which extends into every field of contemporary artistic activity. The theatre gallery is not dedicated to a rigid program or set principles. An informal meeting place for the scenic artists and spectators, it is organized to keep a continuous pictorial record, to parallel the trends and achievements of the living stage.37

5. Travels through Native North and Central Americas

6. Enlivening and Empathy

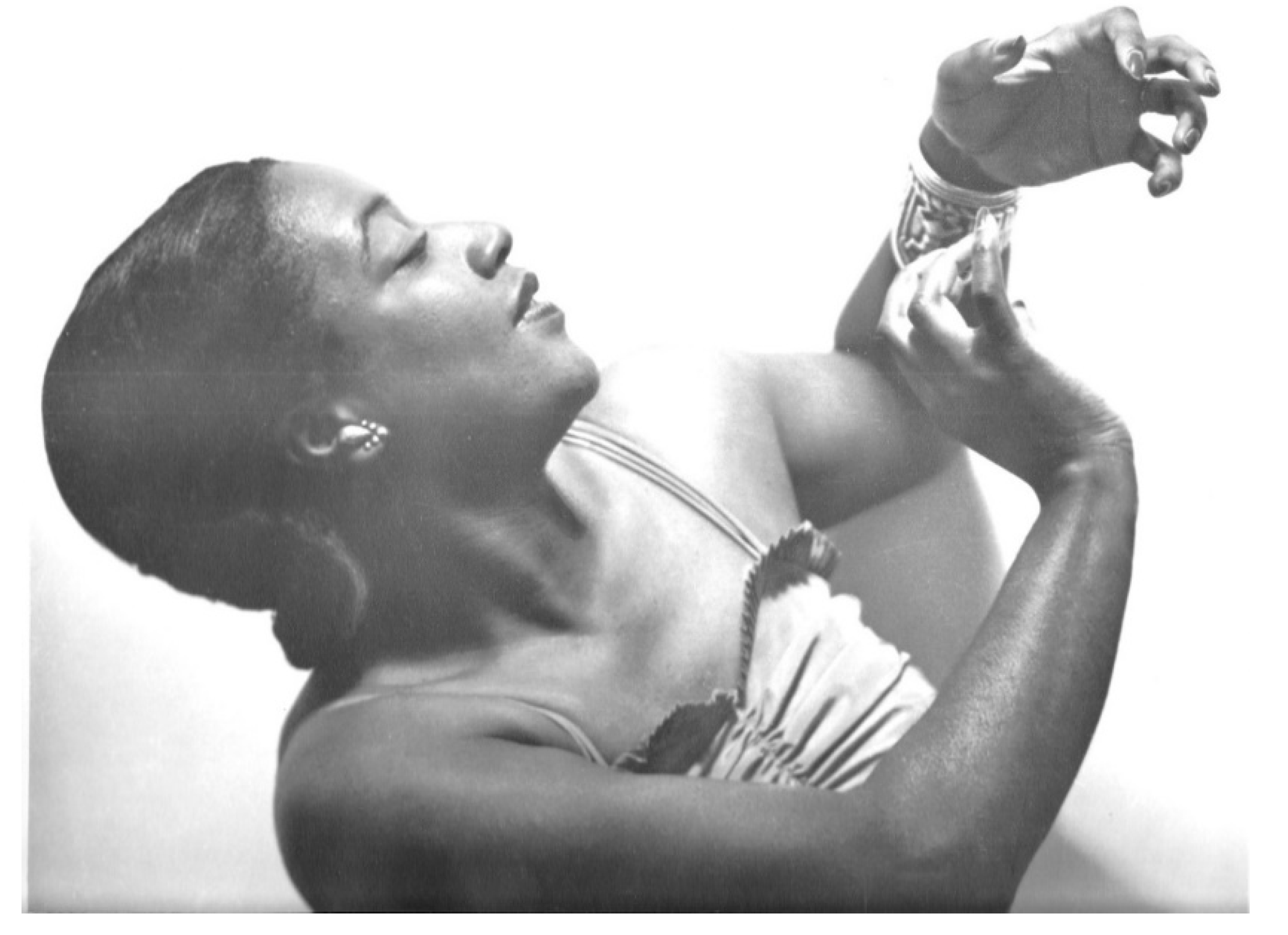

If in linking the arts, it can be said that a half way mark between a portrait and the flesh is a stone statue, certainly Thelma Johnson Streat is a step between sculpture and dance … Mrs. Streat’s effort to inject life and emotion into graphic symmetrical forms is achieved.54

The thing most people find odd is that when I was a child I did very life-like portraits of people, and now I do almost child-like paintings of simple design. But they’re more sophisticated than they look. That’s what Picasso told me when he saw my work in France.55

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NYPL | Special Collections, Thelma Johnson Streat Dance Clipping File, Jerome L. Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts |

| OHS | Thelma Johnson Streat scrapbook Coll 660, Oregon Historical Society Research Library |

| SFMMAA | San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives |

| SFPL | San Francisco Examiner News Clipping Morgue, San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library |

| TJSP | Thelma Johnson Streat Project clippings file |

References

- Batiste, Stephanie. 2012. Darkening Mirrors: Imperial Representation in Depression-Era African American Performance. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, André. 1972. Manifesto of Surrealism. In Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver, and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 1–48. First published in 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Daphne. 2007. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom 1850–1910. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Jayna. 2008. Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buick, Kirsten Pai. 2010. Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bullington, Judy. 2005. Thelma Johnson Streat and Cultural Synthesis on the West Coast. American Art 19: 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, Carlos. 1940. Mexican Music: Notes by Herbert Weinstock for Concerts Arranged by Carlos Chávez as Part of the Exhibition: Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, Huey. 2010. In the Wake of the Negress. In Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art. Edited by Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz. New York: Museum of Modern Art, pp. 480–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cotera, Maria Eugenia. 2008. Native Speakers: Ella Deloria, Zora Neale Hurston, Jovita Gonzalez and the Poetics of Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, Denise. 2012. Transpacific Femininities: The Making of the Modern Filipina. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Joanna Dee. 2017. Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora. New York: Oxford University Press, Available online: https://www-oxfordscholarship-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190264871.001.0001/acprof-9780190264871-chapter-2?rskey=UtqLTX&result=1 (accessed on 14 September 2019).

- Duncan, Carol. 1993. Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting. In The Aesthetics of Power: Critical Essays in Art History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 81–108. First published in 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Brent. 2001. The Uses of Diaspora. Social Text 19: 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Patrick. 2018. Portland Art Museum School. The Oregon Encyclopedia. March 17. Available online: https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/portland_art_museum_school/ (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Fortney, Sharon. 2010. Entwined Histories: The Creation of the Maisie Hurley Collection of Native Art. BC Studies 167: 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Hal. 1985. The ‘Primitive’ Unconscious of Modern Art. October 34: 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, Julia. 2002. Modern Bodies: Dance and American Modernism from Martha Graham to Alvin Ailey. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Ann Eden. 1997. Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Ann Eden. 1995. Universality and Difference in Women’s Abstract Painting: Krasner, Ryan, Sekula, Piper, and Streat. The Yale Journal of Criticism 8: 103–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Ann Eden. 1998. “Black is a Color: Norman Lewis’s Black Paintings”: n.p. In Norman Lewis: Black Paintings 1946–1977. New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem. [Google Scholar]

- Goldner, Orville C. 1939–1940. Silent Color Footage from Golden Gate International Exposition, Treasure Island, San Francisco. Bay Area Television Archive, Leonard Library. San Francisco State University. Available online: https://diva.sfsu.edu/bundles/187038 (accessed on 24 August 2019).

- Griffin, Farah Jasmine. 2013. Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists & Progressive Politics During World War II. New York: Basic Civitas. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Harry. 1990. “Remembering Charles Alston”. 7–10. In Charles Alston: Artist and Teacher. New York: Kenkeleba Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Hurston, Zora Neale. 1934. Spirituals and Neo-Spirituals. In Negro: An Anthology. Edited by Nancy Cunard. New York: Negro Universities Press, pp. 359–62. [Google Scholar]

- Indych-Lopez, Anna. 2009. Muralism without Walls: Rivera, Orozco, and Siquieros in the United States, 1927–1940. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaprow, Allan. 2003. “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” (1958). In Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Edited by Jeff Kelley. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Robin D. G. 2002. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lafalle-Collins, Lizette. 1997. Streat, Thelma Johnson, American Painter. In St. James Guide to Black Artists. Edited by Thomas Riggs. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Lafalle-Collins, Lizette. 1996. In the Spirit of Resistance: African-American Modernists and the Mexican Muralist School. New York: American Federation of the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Anthony W. 1999. Painting on the Left: Painting on the Left: Diego Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco’s Public Murals. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leja, Michael. 1993. Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the 1940s. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lepecki, Andre. 2006. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lepecki, Andre. 2000. Still: On the Vibratile Microscopy of Dance. In ReMembering the Body [on the Occasion of the exhibition "STRESS" at the MAK, Vienna]. Edited by Gabriele Brandstetter and Hortensia Völckers. Ostfildern-Ruit and New York: Hatje Cantz and D.A.P., pp. 332–68. [Google Scholar]

- Linden, Diana L., and Harry Greene. 2001. “Charles Alston’s Harlem Hospital Murals: Cultural Politics in Depression Era Harlem. Prospects 26: 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Alain. 1997. Music: The Negro Spirituals. In The New Negro. Edited by Alain Locke. New York: Simon & Schuster. First published in 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, Susan. 2004. Modern Dance, Negro Dance: Race in Motion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, J. S. 1955. Conversations with Khahtsahlano, 1932–1954. Vancouver: City of Vancouver. [Google Scholar]

- McChesney, Mary. 1964. Oral History Interview with Shirley Staschen Triest. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. April 12–23. Available online: https://www.aaa.si.edu/download_pdf_transcript/ajax?record_id=edanmdm-AAADCD_oh_213953 (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2006. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Tiya. 2005. Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Stacy I. 2004. Rethinking Social Realism: African American Art and Literature, 1930–1953. Athens: University of Georgia Press, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Perpener, John O. 2001. African-American Concert Dance: The Harlem Renaissance and Beyond. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Radano, Ronald. 2013. The Sound of Racial Feeling. Daedalus: the Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 142: 126–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagon, Bernice Johnson. 2001. If You Don’t Go, Don’t Hinder Me: The African American Sacred Song Tradition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Harold. 1952. The American Action Painters. Art News 51: 22–23, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Audra. 2018. Why White People Love Franz Boas; or, The Grammar of Indigenous Dispossession. In Indigenous Visions: Rediscovering the World of Franz Boas. Edited by Isaiah Lorado Wilner and Ned Blackhawk. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 166–78. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 1993. Going Native: Paul Gauguin and the Invention of Primitivist Modernism. In The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History. Edited by Norma Broude and Mary Garrard. New York: IconEditions, pp. 315–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Jacqueline. 2015. The Presence of Norman Lewis. In Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis. Philadelphia and Berkeley: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and University of California Press, pp. 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument. CR: The New Centennial Review 3: 257–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Harvey. 2010. Embodying Black Experience: Stillness, Critical Memory, and the Black Body. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e025xna&AN=1527083&site=ehost-live&scope=site (accessed on 22 September 2019).

| 1 | Marie Perkins, “The Most Democratic Children”, SF Chronicle, 17 November 1952 (SFPL). |

| 2 | Streat and the Johnson family were not officially enrolled in the Cherokee Nation, though establishing membership was difficult given lack of records for enslaved people, segregation, and Native bias. However, the Johnson family did claim Cherokee ancestry and migrated west from Alabama, part of which is known to be Cherokee ancestral homeland. Thelma Johnson Streat Project, e-mail correspondence with the author, 10 November 2019. |

| 3 | While many reports cite Streat’s birth year as 1912, the hand-colored frontispiece of a personal scrapbook marks her birth date as 29 August 1911 (OHS). |

| 4 | According to an invitation saved in the Streat scrapbook, Streat made a public appearance in San Francisco in conjunction with the DeYoung Museum, which sponsored a “Meet the Artist” event in 1941 as a send-off before the artist’s travels (OHS). |

| 5 | This is, of course, the foundational premise of primitivism: using or appropriating forms “other” to oneself in order to pursue the fantasy of purity, wholeness or completion, or to rectify the perceived decline of one’s home culture. For Huey Copeland, Streat’s cooptation of the “primitive” is a self-conscious construction of herself as negresse—or the staged perception of black feminine identity—as well as the desire for cultural continuity, redress, and reparation (Copeland 2010, p. 485). |

| 6 | On the masculinist notions of primitivism and the persistent conflations of the “primitive” with black and indigenous women’s bodies, see (Duncan [1973] 1993; Foster 1985; Solomon-Godeau 1993). |

| 7 | We have no evidence of why Rabbit Man was specifically of interest to Barr, only that he was supportive of Streat in correspondence after the painting was acquired, for instance agreeing to write her a letter of recommendation for the Albert M. Bender Grants in Aid. See Alfred Barr, Letter to Thelma Johnson Streat, July 1, 1942. Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers, I.A.65, mf 2168: 589. New York: The Museum of Modern Art Archives. |

| 8 | Beginning with Paul Gilroy’s formulation of the Black Atlantic as the “counter-culture of modernity”, or the contact zone between regions involved in the transatlantic slave trade, the Atlantic Ocean has been consistently privileged as the space of black diaspora. However, as Brent Hayes Edwards has pointed out, Black Atlantic leaves little space for exploring diaspora as a transnational network throughout the western hemisphere (Edwards 2001). I further take my cue from Denise Cruz’s elaboration of “transpacific”, a formulation of contact that includes the Pacific, and its Asian and indigenous cultures (Cruz 2012). |

| 9 | Boas became known for his critique of positivist method in anthropology, which had bound the ideas of evolution and race to justify notions of racial inferiority. Instead, he championed a reparative and preservative theory of cultural relativism that studied objects within their historical and social contexts. However, an emphasis on cultural inheritance would continue to neglect the structural workings of power and dispossession, omissions that continued to mark anthropology as a discipline (Simpson 2018). |

| 10 | See “Frisco Artist in New Role”, Chicago Defender, July 21, 1945, p. 17. |

| 11 | Catherine Jones, “Thelma Streat Comes Home: Artist Tells Plans in Child Education”, The Oregonian, June 17, 1945, p. 5. |

| 12 | See “Brush Strokes”, Los Angeles Times. May 23, 1943: C8, and “Coast Painter Gets Two Threats By Klan”, Chicago Defender, December 4, 1943, p. 5. |

| 13 | Judy Bullington quotes the testimony of Beatrice Judd Ryan, California’s supervisor of Federal Art Project exhibitions and one of the organizers of the Pan-American Unity mural (in full called Unión de la Expresión Artistica del Norte y Sur de este Continente [The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South of this Continent]); however, there is no other evidence that Streat was a direct assistant to Rivera (Bullington 95). |

| 14 | Anthony W. Lee identifies Asian American and white assistants on Pan-American Unity, but no African American assistants (Lee 1999, pp. 250–51n17). |

| 15 | See Helen Clement, “Thelma Johnson Streat at S.F. Museum of Art”, Oakland Tribune, March 17, 1946 (TJSP). |

| 16 | Cited in “2 Artists Tie in Art Center Mural Contest” unnamed newspaper clipping, 1944 (OHS). |

| 17 | In their thoroughgoing article on the Harlem Hospital murals, Diana L. Linden and Harry Greene identify this figure alternatively as Aesculapius, the Ancient Roman god of medicine (Linden and Greene 2001, p. 405). |

| 18 | New Horizons in American Art was dedicated to works done under the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration led by Holger Cahill. It was around this time that the circulation and reception of Mexican muralists were also making their way through U.S. exhibition circuits, as Anna Indych-Lopez has written. While Mexican murals were less emphasized in the 1940 exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art, they were front and center in Rivera’s 1931 solo exhibition for which he created eight portable frescoes (Indych-Lopez 2009). |

| 19 | Most of the newspaper articles and reviews of Streat’s performances put 1945 as the earliest performance; Helen Clement dates the first performance to June of 1945. See Clement, “Thelma Johnson Streat at S.F. Museum of Art” (TJSP). |

| 20 | For André Breton’s notion of the “marvelous”, see (Breton [1924] 1972, pp. 1–48). See also (Kelley 2002, pp. 164–70). |

| 21 | “Frisco Artist in New Role”, Chicago Defender, July 21, 1945, p. 17. |

| 22 | Daphne Brooks describes white fascination with the Jubilee Singers in the transcultural “‘contact zone’ of black postbellum performance”, which contributed to their status as the first black “cross-over” musical act (Brooks 2007, pp. 296–97). |

| 23 | See for instance: “Dancer Appears at Recital at Exhibition of Paintings”, The Oregonian. October 15. 1950 (TJSP); “Couple to Give Programs for School Children.” Oakland Tribune. April 7. 1946 (TJSP); and “Negro Dance Mime Will Give Program on Campus Sunday.” Reed College Quest 40 (1951), p. 1. |

| 24 | For a masterful analysis of Hurston’s genre transgressions, see (Cotera 2008). |

| 25 | Primus received a doctorate in anthropology in 1978 from New York University, after completing some coursework at Columbia, where she enrolled in 1945. Dunham began working towards a Masters in anthropology at University of Chicago with Robert Redfield though never completed it, and corresponded with Melville Herskovits at Northwestern as part of her Julius Rosenwald Fund grant (Griffin 2013; Das 2017). |

| 26 | Both points have yet to be corroborated, however (Bullington 2005). |

| 27 | Langston Hughes, Letter to Juanita Johnson, October 13, 1941 (OHS). |

| 28 | While film recordings of Streat’s performances are said to exist, the archive has yet to reveal them. At least one newspaper article notes the existence of film recordings made of Streat’s performance at the San Francisco Museum of Art by actor Burgess Meredith and his production company New World Studio. See “Artist-Dancer, Thelma Streat, To Appear Here”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 7, 1948 (OHS). |

| 29 | A Recital of Interpretive Rhythms Program. Chicago: Kimball Theater. September 16, 1945 (OHS). |

| 30 | Albert Goldberg, “Kimball Hall Opens Season with Recital by Thelma J. Streat”, Chicago Daily Tribune. September 17, 1945, p. 16. |

| 31 | Wilma Morrison, “Portland Interpretive Dancer Wins World Acclaim, Professes She Prefers School Work to Club Glitter”, The Oregonian, September 4, 1951 (TJSP). |

| 32 | Performance Program, Sartu Theater, Los Angeles. December 9, 1951 (OHS). |

| 33 | Unpaginated notice in Dance Magazine, November 1945. (NYPL). |

| 34 | See Marcel Frere, “Ce Soir”, included in The Art of Thelma Johnson Streat: American Artist brochure (NYPL). |

| 35 | Marion McEniry, “Thelma Streat Back from Triumphs; Noted Artist Returns to S.F.”, San Francisco Examiner, November 23, 1952, p. 5 (OHS). |

| 36 | Jones, “Thelma Streat Comes Home”, p. 5. |

| 37 | “Museum of Modern Art Opens Theatre and Ballet Design Gallery”, Press Release, April 9, 1945. Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. |

| 38 | Ann Eden Gibson proposes that we see women working in the various idioms of Abstract Expressionism as claiming a “universality of difference”, rather than difference as at odds with the universal (Gibson 1995, p. 110). |

| 39 | Grace McCann Morley, Letter to Thelma Johnson Streat. February 21, 1946. Box 70, Folder 16 (SFMMAA). |

| 40 | “Interpretations Based on Negro Themes”, Program for Thelma Johnson Streat, presented jointly by The San Francisco Museum of Art and The San Francisco Dance League, March 20, 1946 (SFMAA). |

| 41 | Grace McCann Morley, Undated loan letter to lenders. Box 70, Folder 16 (SFMMAA). |

| 42 | “Interpretations Based on Negro Themes”, Program for Thelma Johnson Streat, presented jointly by The San Francisco Museum of Art and The San Francisco Dance League, March 20, 1946 (SFMMAA). |

| 43 | Bill Rose, “Brilliant Negro Artist is Here to Study Indian Lore”, Vancouver Sun. August 16, 1946, p. 15. |

| 44 | The name “Khahtsahlano” was not used by the Native community but was recorded by deed poll in Victoria before the “Change of Name Act” was passed; thus it was the name commonly referenced in the press (Matthews 1955). |

| 45 | Squamish Nation Online, “Our Land”, 2013. Available online: https://www.squamish.net/about-us/our-land/ (accessed on 27 November 2019). |

| 46 | The mask now resides in the North Vancouver Museum and Archives (Fortney 2010, p. 85). |

| 47 | Fortney notes a recent episode in which Squamish community members lobbied the North Vancouver Museum and Archives to remove the mask that Khahtsahlano carved and gifted to Maisie Hurley, which had been on view (Fortney 2010, pp. 86–87). |

| 48 | McEniry, “Thelma Streat Back from Triumphs”, 5 (OHS). |

| 49 | Ibid. |

| 50 | See May Ebbitt, “Hypnosis Aids Artist in Work”, The Montreal Standard, August 18, 1951 (OHS). |

| 51 | For more on black women’s roles in the orientalizing function of revues and popular dance, see (Brown 2008; Batiste 2012). |

| 52 | See citation in “Negro Dance Mime Will Give Program on Campus Sunday.” Reed College Quest 1951, p. 1. |

| 53 | Performance Program, Sartu Theater, Los Angeles. December 9, 1951 (OHS). |

| 54 | Zelda Ormes, “Noted Dancer-Painter to Show in First Local Performance Today”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Undated, unpaginated clipping originally published in the Pittsburgh Courier (OHS). |

| 55 | Ebbitt, “Hypnosis Aids Artist in Work” (OHS). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schriber, A. Mapping a New Humanism in the 1940s: Thelma Johnson Streat between Dance and Painting. Arts 2020, 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010007

Schriber A. Mapping a New Humanism in the 1940s: Thelma Johnson Streat between Dance and Painting. Arts. 2020; 9(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchriber, Abbe. 2020. "Mapping a New Humanism in the 1940s: Thelma Johnson Streat between Dance and Painting" Arts 9, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010007

APA StyleSchriber, A. (2020). Mapping a New Humanism in the 1940s: Thelma Johnson Streat between Dance and Painting. Arts, 9(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010007