What are the parameters of Native American art in relationship to modern or contemporary art? Do tribal and regional idioms fall away? Do formalist concerns prevail? Can art be individualistic rather than communitarian in its subjects? All these are questions are asked by scholars and viewers alike. A variety of studies have addressed these questions over the last two decades and produced such works as Bill Anthes’ 2006,

Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960, or Jennifer McLerran’s 2012,

A New Deal for Native Art: Indian Arts and Federal Policy, 1933–1943 alongside important surveys such as

Native North American Art by Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth Phillips or David Penney’s

North American Indian Art, both of which have sections dedicated to modern and contemporary Indigenous arts.

1 Even before the above-mentioned scholars turned to the works of Native American artists in the modern era, there were already debates about the about the so-called ‘primitive arts’ in relation to the

objet d’art. Anthropologist Sally Price, wrote provocatively about the tension within Western museums concerning the ethnographic artifact and the same object when considered under the rubric of art. More recently, Sylvia Kasprycki has examined the politics if identity and representation in contemporary Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) art.

2 In this essay I am not concerned with traditional Haudenosaunee handicraft—no matter how beautiful—but rather those Haudenosaunee artists in the modern era who self-consciously adopted Western notions of fine art in the forms of two-dimensional representational art, non-traditional sculpture, and later new media, such as photography and film.

3In that same vein, as a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) scholar interested in both our historic material culture and contemporary artistic expression, I could not help but wonder where twentieth century Haudenosaunee art fits into the larger world of Indigenous modernisms, which occupy and define a different tradition than the Euro-American notion of “Modern art”.

4 On the Trails of the Iroquois was an exhibit mounted in Bonn, Germany, curated by Sylvia

Kasprycki (

2013).

5 It was an extremely ambitious retrospective survey covering some 400 years of Haudenosaunee visual and material culture—spanning from the seventeenth century up to the present. I was one of the contributors to the catalog of the same title and was present at the opening. I recall commenting that if the Six Nations had an official National Museum of Haudenosaunee Art and Material Culture that I imagined it would look something like the exhibit in Bonn. Materials had been brought together from major North American and European collections and a number of more obscure private collections as well. Aside from the inspiring pieces that survived from the early colonial period and the beautiful beadwork and handicrafts of the nineteenth century, I was most impressed by the inclusion of more contemporary pieces of art from Haudenosaunee artists of the twentieth century. Some of these works were familiar, like those of Ernie Smith, which I recognized from the Rochester Museum and Science Center where they had been since the 1930s, but others were wholly new to me and came as a revelation. It led me to wonder, what was the history of collecting Haudenosaunee art created during the modern era? With all the prescriptive notions of authentic (aka traditional) Indian handicrafts, who were those collectors that first saw the value of non-traditional media and forms?

Of course, those who know Native cultures beyond the stereotypes know that we have always been innovators—that is certainly part of Haudenosaunee tradition. We were among the earliest North American Indigenous peoples to encounter European explorers and colonial settlers. Like other Native nations of the Northeast, the real onslaught began in the seventeenth century. There had been fleeting contacts with explorers and traders in the sixteenth century, but the full-scale colonial invasions began in the early seventeenth century. In addition to encountering new diseases and new religions, we also encountered new technologies and the products they produced. We know that all of these elements had a dramatic effect on the way of life and arts and crafts of Native peoples. Scholars of the history of material culture have long noted Indigenous habits of adaptation and innovation when it came to using and repurposing newly available manufactured goods, such as copper kettles, glass beads, woven cloth, and steel tomahawks.

6 The particulars of Haudenosaunee arts and material technologies have been studied systematically by settler scholars since the work of Lewis Henry Morgan (at the least) and of course these same handicrafts were bought and used by settler consumers long before that. Iroquois basket sellers were so common a sight in parts of Ontario, Quebec, and New York that they were the frequent subject of the mid-nineteenth century genre painter Cornelius Krieghoff (

Figure 1). Yet almost all these traditional arts might be designated as ‘applied arts,’ since all had a level of utility or sacred function, and most were vulnerable to replacement by industrially manufactured goods as the nineteenth century progressed.

In part, my personal interest lies in the expansion of Haudenosaunee arts to include the two-dimensional representational arts drawn from settler traditions. Just as Haudenosaunee artisans adapted to working with glass beads, thus expanding their decorative skills beyond quillwork and shell wampum, so too were other Native artists drawn to European traditions of drawing and painting. Some of the earliest Haudenosaunee artists to take up settler-style representational art were the Cusick brothers, David and Dennis, from the Tuscarora nation in the early decades of the nineteenth century. Scholars may debate whether to accept William Sturtevant’s discussion of their style as establishing what he calls “Early Iroquois realist art” (

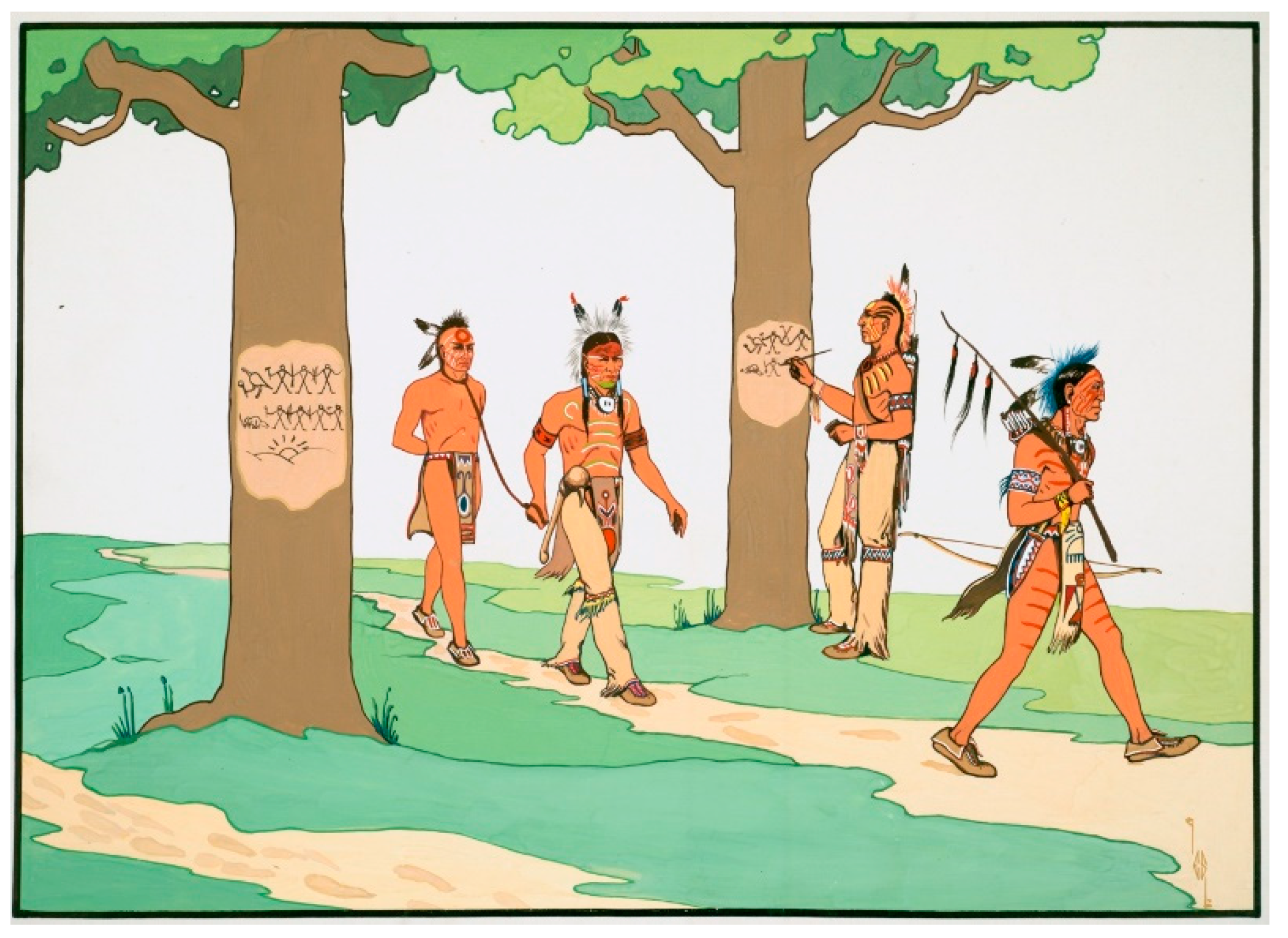

Sturtevant 2006). What is clear is that these two self-taught artists were among the first within our communities to produce representational drawings and paintings of Haudenosaunee culture. While David Cusick provided drawings that would serve as the originals for engraved illustrations to ancient Haudenosaunee legends and history, Dennis Cusick illustrated contemporary Tuscarora and Onondowagah (Seneca) life in the 1820s (

Figure 2). Janet

Berlo (

2013, pp. 178–81) notes that stylistically the works of both of these brothers had much in common with regional and self-taught settler artists of the Federalist period. They have a naïve or folk-art quality to them, but they focus exclusively on Haudenosaunee culture. They are not the only Haudenosaunee painters in this period using this style that Berlo labels ‘intercultural’. Other artists like Thomas Jacobs and George Wilson, either Onondowagah or Tuscarora (we cannot be certain as their surnames exist on both reservations), painted works collected on the Cattaraugus Reservation reminiscent in style to Dennis Cusick. They feature Native figures dressed in the hybrid styles that prevailed among Haudenosaunee people in the early nineteenth century (

Figure 3).

This turn toward two-dimensional artistic representation marks a shift in Haudenosaunee visual culture, though there remains little evidence of its true impact until the early twentieth century. The turn of the century also marked the nadir of Native American history: the Indian Wars had gone on intermittently from the end of the Civil War until 1890, when they concluded with the Massacre at Wounded Knee; Indian boarding schools had been taking up the task of forced assimilation and inflicting trauma on generations of Native children since the 1870s, even as their families left behind were confined to desperately poor and under-resourced reservations, with populations at historic lows. While Native cultures of the far West had experienced the full onslaught of American settler culture for less than one hundred years at that time, cultures of the Eastern Woodlands had endured ongoing colonial dispossession and forced assimilation for some three centuries by 1900. Yet the Haudenosaunee are among the most culturally intact Indigenous nations in the region, though understandably heavily acculturated.

Even so, historians of material culture have long noted that several handicrafts among the Haudenosaunee had all but died out as soon as European manufactured goods became available through trade. This was most apparent with traditional pottery, which had largely been used for cooking purposes in the Northeast and was quickly replaced with copper kettles and other European cooking vessels (

Bradley 2005, p. 174). Other arts evolved and changed with the introduction of European materials such as woven cloth, glass beads, and trade silver (

Gibb and Frederickson 1980). The long-term fate of any of these traditional arts and crafts was uncertain by the twentieth century as the age of mechanical reproduction was moving into high gear and handicrafts were identified with the past in a majority culture enamored with progress. Only nostalgic notions concerning collecting Indian crafts of a bygone era or the desires of salvage ethnographers for traditional (i.e., authentic) Indian goods created any demand for such objects, but like most fads, this demand would wane (

Hutchinson 2009). After the 1920s salvage ethnography was replaced by ever growing numbers of tourists now seeking exotic souvenirs from the remote American West.

As Jennifer McLerran notes in her study of the New Deal policies’ impact on Native arts, both John Collier, head of Roosevelt’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Rene d’Harnoncourt, head of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, considered tourism and the souvenir trade an imminent threat to the quality and authenticity of Native American arts (

McLerran 2009, chp. 1). Yet these men’s attention was focused on the American Southwest and not the Northeast. They likely thought the Native communities in the East far too distant from our ancient traditions and arts to be much effected by tourism—if indeed, there was any tourism amongst the surviving reservations of New York State and New England. By this period many eastern Natives had adopted either Pan-Indian motifs in their arts or Plains Indian regalia and crafts as a means of being read as Indian by the majority population around them (ibid., p. 87). I still remember childhood trips to the annual Border Crossing Parade at Niagara Falls, a Native-organized event meant to commemorate the Jay Treaty of 1794, which guarantees our unimpeded crossing of the U.S. and Canadian border. For years there, during my childhood, Harold Johnson (Kanien’kehá:ka) led the parade wearing a full Plains headdress and riding a horse. Even as a boy I knew it was inaccurate, but for the non-Native onlookers this made the event ‘Indian’. Still, it must be noted that while White expectations about Indian-ness may have influenced our craftspeople to alter their art to accommodate that market, it was also the tourist market that had long helped perpetuate the production of our traditional arts such as beadwork and basketry (

Phillips 1999) (

Figure 4).

Much of what we know about those traditional arts we know from earlier collections. Specifically, there existed a great collection of Haudenosaunee material culture assembled by the nineteenth century anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan. Morgan made his career as a self-taught anthropologist by working primarily with the Onondowagah (Seneca) in Western New York State in the 1840s. He published his landmark study

The League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois in 1851 and would go on to be considered one of the founders of the field of anthropology in the United States. A large part of his success lay in his close work with Onondowagah cultural informants Ely and Caroline Parker of the Tonawanda Seneca. Perhaps now more important to students of material culture than his deeply problematic racialized notions of cultural evolution, are Morgan’s writings on Haudenosaunee arts, tools, and clothing, along with the collection of the same which he amassed for the State Museum in Albany. Morgan published his description of that collection which he had prepared in the

Third Annual Report of the Regents of the University on the Condition of the State Cabinet of Natural History and the Historical and Antiquarian Collection Annexed Thereto. This prosaically titled 183-paged work, with over two dozen colored lithographic plates, as well as etchings of material objects embedded in the text, represents a landmark in the preservation of Haudenosaunee material culture (

Figure 5). Without this text and the surviving objects from Morgan’s collection certain individual crafts might likely have been lost.

The state of New York saw these objects as representing the antiquarian legacy of its past, whereas for Haudenosaunee people these objects represented our living cultural inheritance. Over the three generations that followed Morgan’s mid-nineteenth century collecting activities, much of the technical knowledge that went into the production of these culturally distinct objects would be lost to the effects of forced assimilation, displacement from sites of production, and shifts in markets and tastes. By the early twentieth century, for example, Sarah Hill of the Cattaraugus Seneca Reservation was the last known weaver of traditional basswood burden straps (

McLerran 2009, p. 89). Other forms of fingerweaving were also dying out with the ready availability of industrially-produced knit ware and woven goods. Morgan’s collection would serve as a sort ‘craft hoard’ for later artisans interested in preserving or reviving Haudenosaunee arts and crafts; though the collection was dealt a severe blow in 1911 with the fire in the State Capitol building in Albany. The bulk of the Morgan collection was on display in the galleries reserved for them in that building when the fire broke out. Up to a third of the collection was lost or badly damaged. Luckily a young Onondowagah anthropologist, Arthur C. Parker, a direct descendant of the same Parker family that had been central to Morgan’s research, worked for the State at the time of this catastrophe. He was determined to rebuild this collection that represented the material and artistic heritage of Haudenosaunee culture.

Scholars have long noted the enduring legacy of Arthur C. Parker on contemporary Haudenosaunee arts. It was his vision in this dark period of ‘salvage ethnography’ that saw a way forward to cultural revival. In addition to material culture, Parker was aware of the profound importance of Haudenosaunee oral culture. He was not alone in these insights, but he did have access to institutional support that would prove invaluable during his Depression-era activities. The spiritual tradition of the Longhouse religion, as influenced by the prophet Handsome Lake, was maintained all along by our Faithkeepers and Clan Mothers. These beliefs did not require the support of outside funding or anthropologists to account for their

survivance, to use Gerald Vizenor’s term. Although Parker’s vision of an arts and crafts revival did require much-needed capital in order to be successful. Parker joined the staff of the Rochester Municipal Museum, as it was then known, when it became clear that Albany would not provide the necessary funds to rebuild the Morgan Collection (

Hauptman 1981, p. 137;

McLerran 2009, p. 88).

It was during his time at the Rochester Municipal Museum that the events of the Great Depression created a timely opportunity for Parker to propose an initiative to revive and support the traditional arts among artisans of the Onondowagah population. Founded in 1935, the Seneca Arts Project would, over the course of six years, support the work of over 100 Indigenous artists in New York State—almost all of them Onondowagah, with some few drawn from other Haudenosaunee communities as well. Parker and his cohort set out to build up the collections of the museum in Rochester with authentic Haudenosaunee artifacts that, even when explicitly reproductions of past works, qualified in the minds of the museum staff as authentic because they were produced by Haudenosaunee artists and made of the same materials and, whenever possible, by similar techniques employed hundreds of years ago. Parker’s own notions of art as culturally specific were deeply essentialist and grounded in early twentieth century notions of race:

Making Indians imitators of that which they did not create racially had done much to exterminate the Indian or to make him a poor spirit. Our arts project as a relief measure thus seeks to capitalize on the best in ancient art and to redevelop it as a racial contribution. We are saving the old arts and passing them on to the youth of the reservations and the very effort made to achieve this is reawakening interest in the Native pattern of thought. The plan has commercial as well as idealistic features in that it will provide a better type of manufactures for trade. Instead of cheap and tawdry souvenirs that have nothing of the old art in them our workers will now make objects that have ethnological value. They will be typical of the days when Indian art was original and pristine.

I would particularly like to focus on the earliest Haudenosaunee visual artists in this group whose works departed from traditional crafts such as beadwork, carving, and basketry and began to experiment with representational painting. These three artists could be said to represent a pictorial turn in Haudenosaunee art, and all were connected to the Seneca Arts Project: they were, Jesse Cornplanter (1889–1957), Sanford Plummer (1905–1974), and Ernest Smith (1907–1975).

When Parker went about assembling his team of artists and craftspeople, he quickly identified the most talented individuals living on the Onondowaga reservations at Alleghany, Cattaraugus, and Tonawanda. Prominent among them was Jesse Cornplanter, a direct descendant of the late eighteenth century Seneca leader of the same surname (

Hauptman 1981, pp. 146–50). Born in 1889 he had already lived an eventful life by the 1930s. Noted as an artistic prodigy at nine years old, he was encouraged to practice drawing; at 24 he starred in a silent film version of the

Song of Hiawatha in 1913, he then served with distinction in the First World War earning a Purple Heart, and later learned the traditional woodcarving skills necessary to produce sacred medicine masks (a.k.a. ‘false faces’). Cornplanter was also well rehearsed in Haudenosaunee folklore and storytelling—a culture bearer of sorts. In addition to teaching carving skills to those involved with the Seneca Arts Project, Cornplanter, who had been illustrating scenes of traditional Seneca life since he was a boy, was asked to provide the illustrations for the folklore which he was now dictating to an amanuensis as part of the Seneca Arts Project. Parker had been aware of Cornplanter’s earlier drawings well before the arts project, having selected several of them to serve as illustrations to his 1922

Seneca Myths and Folk Tales. These naïve rustic drawings bear some relation to the drawings of the Cusick brothers and those Haudenosaunee artists that followed their example. They are not as stylized as those earlier examples, but they have the immediacy of an insider’s view of his culture (

Figure 6). What is worth noting is the style of his drawings does not seem to progress over the years and his early drawings are difficult to distinguish from those decades later. Perhaps as important as his participation in the Seneca Arts Project was the fact that Jesse Cornplanter’s version of these

Legends of the Longhouse, as they were titled, were published as a book, complete with Cornplanter’s illustrations, in 1938.

News in our small communities of one of our members publishing a book would be noteworthy now but would have been immense news in the 1930s. It is hard to express to people outside of our communities what pride there is in any Native achievement, especially among my grandparents’ generation, who grew up recovering from the trauma of boarding schools and having internalized White attitudes about Indian inferiority. My Kanien’kehá:ka grandparents were quick to point out any and all Native accomplishments—be they the skyscrapers erected by Kanien’kehá:ka ironworkers or the fact that an Osage Indian, Maria Tallchief, had become America’s first

prima ballerina sometime in the 1950s; as a young boy I was not sure what that meant but I knew my grandparents were proud that she was Indian. Today in the post-Red Power days when one presumes all Native people are proud of their heritage, we forget those long periods in American history when it was considered something to overcome. I mention all this because in a recent conversation with the Onondowagah artist Peter Jones, he told me it occurred to him in the early 1960s to go to art school because he had seen books illustrated by Seneca artists, specifically Jesse Cornplanter and Ernest Smith.

7 This recognition of possibilities is crucial in marginalized communities.

Jones probably had not seen the works of Sanford Plummer, the artist most influenced by European and American training of the three mentioned above. Plummer studied at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design and the National Academy School of Fine Art, both in New York City, as a young man and produced refined paintings in what is sometimes referred to as the illustrator style for the Seneca Arts Project (

Hauptman 1981, p. 221) (

Figure 7). He was proposed as a potential muralist for some WPA period projects and his individual paintings are in collections in museums in Buffalo, Rochester, and Newark (ibid., p. 156). Not much is recorded of his career beyond the 1940s and perhaps it is simply that his elegant early twentieth century style never translated to viewers beyond the realms of illustration and public art. Compared to the dynamism of the American art scene from abstract expressionism and beyond in the 1940s and postwar period, the works of a Beaux-Arts trained regional painter were not likely destined to have a large impact. When I have spoken to Haudenosaunee artists of generations older than myself, none mentioned Sanford Plummer’s work as having an impact on them or even being very familiar with them. We know Plummer remained close to his community and died in Gowanda, a village on the border of the Cattaraugus Seneca Reservation, in 1974. An excellent collection of some twenty of his watercolors is housed at the Newark Museum of Art.

By far the most prolific of the thee painters recruited by Parker was Ernest Smith (

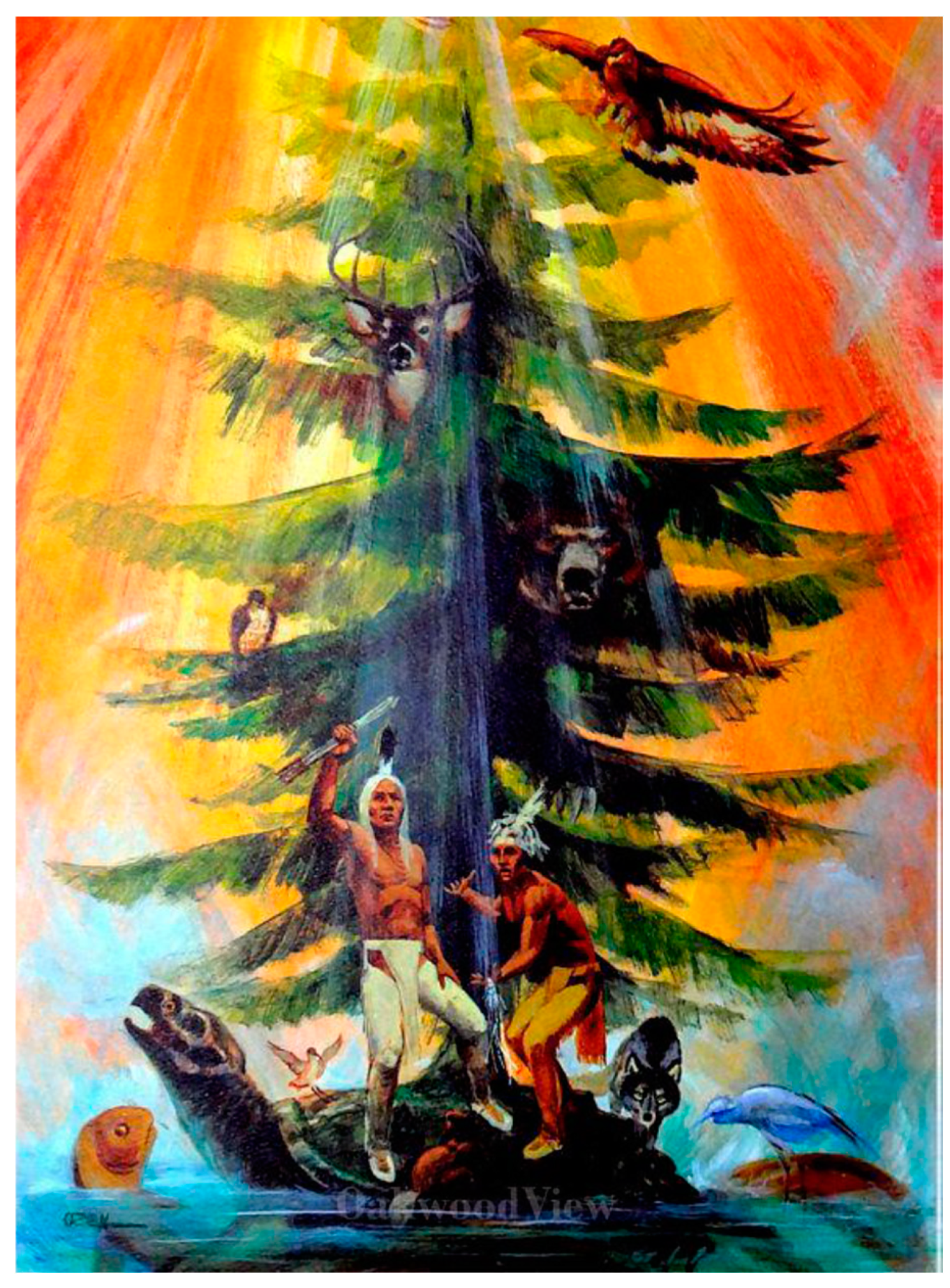

Cornelius 1999, pp. 164–68). Born on the Tonawanda Reservation in 1907, Smith grew up quite poor and was a self-taught artist who had left school before graduating to help support his family; he received no formal education beyond that. His artistic talent was innate and the focus of his work throughout his career was on depicting various aspects of his culture from ancient Haudenosaunee folklore to images of quotidian life in earlier periods of Haudenosaunee history. The bulk of his original works are held by the Rochester Museum and Science Center (previously known as the Rochester Municipal Museum). Many of these are oil paintings and the rest are watercolors or pen and ink drawings. Parker specifically charged Smith with illustrating scenes from Haudenosaunee history, beginning with the Creation Story and the fall of Sky Woman to Turtle Island (

Figure 8). The influence of Jesse Cornplanter is apparent in some of his paintings’ style at the beginning of the Arts Project (

Figure 9). In many ways it was his depictions of daily life in a reimagined past that captured my imagination as a boy. The somewhat flat illustrator style presents us with a dignified, if not idealized, version of Haudenosaunee life free of the endemic poverty and cares of contemporary reservation life during the Great Depression (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). What likely strikes any student of Smith’s art is that his style changes remarkably within short periods of time and occasionally he seems to return to an earlier style, closer to Jesse Cornplanter. We cannot know if Smith was ever exposed to the works of the Native artists from the Southwest who were developing an analogous “Studio style” at the same time under the instruction of Dorothy Dunn in Santa Fe. She taught at the Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School from 1932 until 1937 (

Berlo and Phillips 2014, p. 260). There is a slim possibility Smith would have been exposed to her through the museum, but the timeline is possibly too short given Smith’s relative geographic isolation (beyond the museum in Rochester). At other times it seems Smith may have been influenced by the cartoon style of Walt Disney whose feature length films were tremendously popular at this time. There is a smoothness and flatness to some paintings from 1939 onward, and a hard edge to Smith’s depictions that appear to have more visual similarities with the human figures in Disney’s

Snow White than the rougher drawings of Jesse Cornplanter that influenced his earlier paintings (

Figure 12). Whatever the influences were, copies of Smith’s paintings were easily adapted to serve as illustrations to any number of works or as decorative prints illustrating scenes of Haudenosaunee history or everyday life.

What Arthur Parker valued in both Cornplanter and Smith’s works was their adherence to his instructions to represent all aspects of Haudenosaunee culture, while reviving an iconographic vocabulary that would be identifiably ‘Iroquois’ in the minds of the viewer. It was to a great extent not only a plan for cultural revival but also for cultural branding. Native artisans had strayed from traditional crafts and decorative motifs that had distinguished Haudenosaunee material culture in the past and adopted an easy Pan-Indianism or else simply appropriated Plains styles as a shorthand for Indigeneity. Parker’s quest for a return to cultural specificity demanded that Haudenosaunee artists practice traditional arts and use traditional folkloric themes and visual motifs in their representational works. He meticulously recorded various elements of design and iconography in his scholarly publications and the Seneca Arts Project supplied him with artisans who could turn his scholarly work into contemporary practice. In six years, the Seneca Arts Projects was estimated to have produced some 5000 pieces of traditional Haudenosaunee arts and crafts along with murals, paintings, and dozens of illustrations for printed materials. Not only were certain arts and techniques that had been on the brink of being lost now revived with new practitioners, but the printed materials gave interested members of the broader public resources for learning about traditional Haudenosaunee culture.

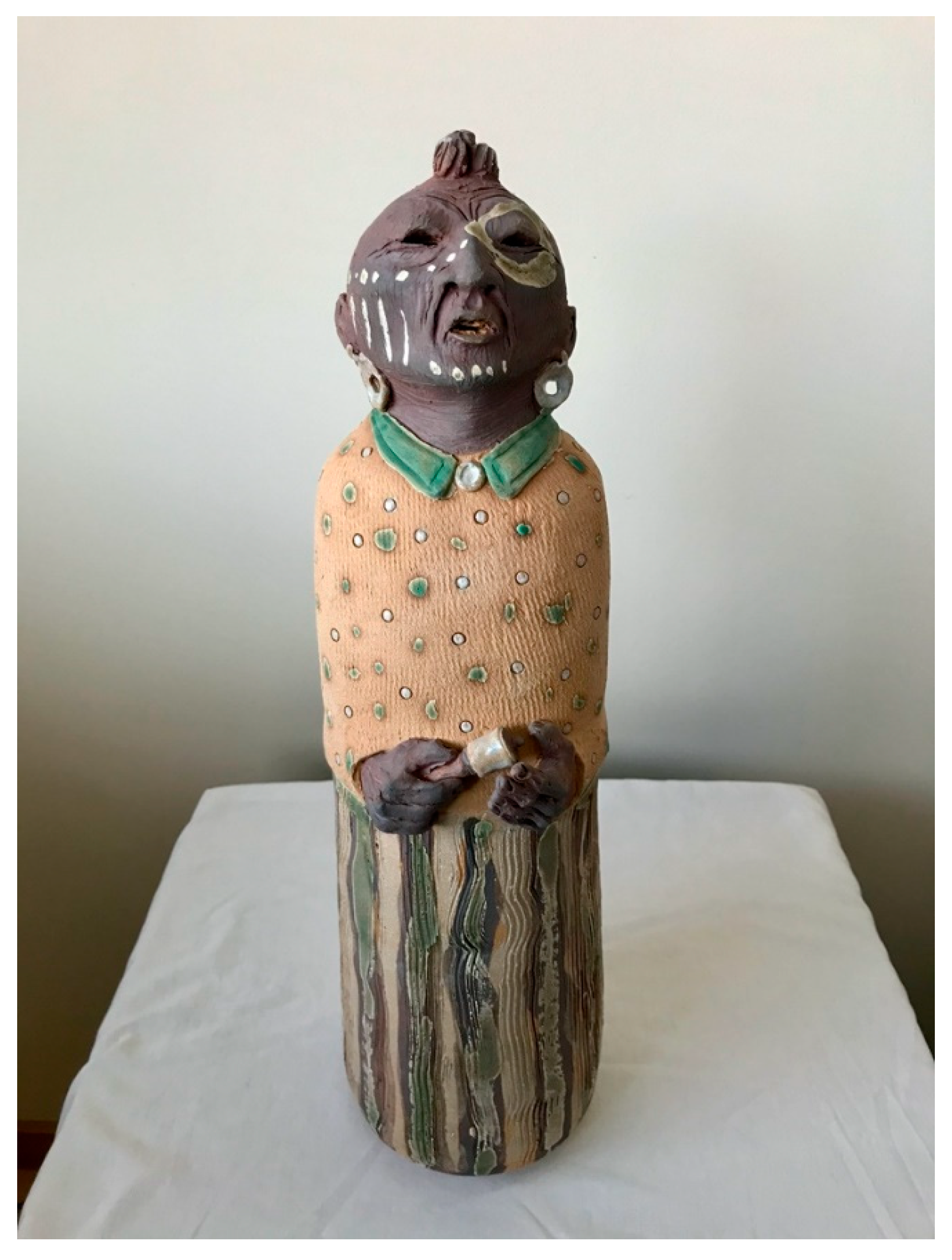

World War II was a major disruption in the movement begun by Arthur C. Parker and supported by the WPA, but the skills that it reintroduced to Haudenosaunee communities were not forgotten. The fact that Seneca artists now had works in museums and had published their illustrations made the possibility of the life as an artist, commercial or otherwise, a genuine possibility. Representational paintings and illustrations allowed for new outlets to those individuals in our communities with artistic interests. Both the Onondaga Faithkeeper, Oren Lyons, and the Seneca ceramic artist, Peter Jones, pursued college degrees in the fine arts with the notion of becoming commercial artists. Oren Lyons received a BFA from Syracuse University in the 1950s and spent several years illustrating and designing for a greeting card company before returning to his home reservation and painting scenes from Haudenosaunee culture and history (

Figure 13). Jones was amongst one of the early cohorts of students to attend the newly founded Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe in the mid 1960s and went there with the intention of becoming a commercial artist as well; but finding he much preferred his classes in ceramics to the figurative drawing and painting classes, switched his artistic medium to clay (

Figure 14). Works by both Lyons and Jones have been collected by art museums and ethnographic collections. Jones is represented in a wide variety of collections, including the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and Institute of American Indian Arts in the mid-1960s. Many others would follow, such as the Heard Museum, the Southern Plains Museum in Anadarko, the Bruce Museum in Connecticut and Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Museum of Anthropology in Frankfurt, the Woodland Cultural Center in Brantford Ontario, and the National Museum of the American Indian.

The Tuscarora artist and educator Richard Hill likewise acknowledged in a published essay that his artistic models were both Ernest Smith and Jesse Cornplanter. Of them he wrote, “My influences have been Ernest Smith, a Seneca painter who taught me that painting has a role to play in the education of the Indians of the future; [and] Jesse Cornplanter, Seneca artist whose work taught me that we have a grand tradition in storytelling and that the visual artist has become the storyteller of this generation” (

Hill 1996, p. 131). Clearly the recognition that both of those Depression-era artists received in their lifetimes had a larger effect than their respective styles of drawing or painting. Arguably it was the redeployment of Haudenosaunee cultural idioms into their visual representations that inspired later generations of Haudenosaunee artists. Once the possibility of becoming an artist opened up to Haudenosaunee youths there was no stopping its tremendous and liberating appeal. The 1960s and 1970s saw the continuing and persistent growth and revival of craft work and contemporary arts throughout the Haudenosaunee homelands. By 1976 Haudenosaunee promoters of the arts formed the Association for the Advancement of Native North American Arts and Crafts in Niagara Falls, NY. The founding directors were all active Haudenosaunee cultural practitioners: Huron Miller, Elwood Green, Michael Mitchell, Carson Waterman, and Allen Jock. They, along with researchers and interviewers, Christina Johannsen and Alisa Myke, would after several years of research publish

Iroquois Arts: A Directory of a People and Their Work in 1983 (

Johannsen and Ferguson 1983). This a

magnum opus of sorts, covering the craftspeople of twelve reservations and interviewing and recording the works of 568 individual Haudenosaunee artists. Arthur Parker in his wildest imagination could never have predicted that number. In the final five decades of the twentieth century there was a considerable movement by Haudenosaunee artists into new and mixed media and these artists would reach broad acclaim and some established international reputations for themselves and their culture.

While Native artists such as Oscar Howe, Fritz Scholder, and T.C. Canon are usually identified with the Native Modernism developed in the Plains and the Southwest in the late 1950s and early 1960s, their art usually touched on Native American themes in a broader manner with less reference to specific Native national cultures and their content concerned the American Indian experience in a postwar period of burgeoning inter-tribal political activism. This occurred at the same period that the United States Congress instituted its so-called “Termination and Relocation” policies, which aimed at dissolving reservations and encouraging Native people to move to urban centers, with the ultimate goals of detribalization and assimilation. Haudenosaunee people were likewise increasingly politically engaged in this same period, but their artists still tended to draw on a culturally specific visual vocabulary.

By the 1970s the influence of Fritz Scholder can be seen in the work of Clifford Maracle (Kanien’kehá:ka). In a painting like “Back to School” in which a figure in a blue boarding school student’s uniform stands behind a Native man in traditional dress, both rendered more abstractly, signals a critique of the boarding school experience from a broadly Indigenous North American perspective, since Maracle was from the Tyendinaga Reserve in Ontario. We do not see the Haudenosaunee-specific references that will develop as we move into the late 1980s with the foregrounding of a more ethnically specific iconography, such as we find in the paintings of Carson Waterman (Onondowagah). It was also a period when the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) was being formulated as the Haye Foundation began to turn over its voluminous artifacts to the Smithsonian Institute to serve as the core collection of the newly planned National Museum of the American Indian. The 1989 National Museum of the American Indian Act called for the creation of a national museum on the capital mall in Washington, DC, with a smaller portion of the collection to be housed in the former U.S. Customs House in lower Manhattan.

This new museum was to be very different from its Smithsonian siblings—the NMAI would have to address the deep distrust many Native people had concerning museums, be it the fact that they sometimes held the human remains of our ancestors or alienated so many objects of our cultural patrimony from their source communities. One way to address this long-term problem was to commit to community consultations and another way would be the employment of Indigenous museum professionals and curators. This would occur at both its New York City site and in the site on the Mall in Washington. The New York museum opened first in 1994 and was followed by the capital museum ten years later. Among the dozens of Native scholars and artists who consulted with and held positions at NMAI, two Haudenosaunee scholar-artists, Rick Hill and Jolene Rickard, both contributed to exhibits and long-term collecting strategies. In order to shed the assumption that NMAI would deal only with Native cultures in the past, many curators and educators now at NMAI argue for the inclusion of contemporary Native American art. This policy would have the effect of promoting contemporary Indigenous art exhibitions and the collection and display of that art at a national museum.

The 1990s saw figures like Shelley Niro (Kanien’kehá:ka), Alan Michelson (Kanien’kehá:ka), and Jolene Rickard (Tuscarora) all achieve recognition through individual and group exhibits, and all collected by major art museums. Other exhibitions have focused solely on Haudenosaunee contemporary artists at least since the 2000s and have done much to familiarize the art viewing public with our cultural idioms and our social and political concerns—often foregrounded in the work of our artists. Exhibits such as the 2003 Lifeworlds—Artscapes: Contemporary Iroquois Art, curated by Sylvia Kasprycki and Doris Stambrau in Frankfurt, Germany, traveled to Zurich, Switzerland and then Brantford, Ontario. It featured artists who remain at the center of the Haudenosaunee artworld today: G. Peter Jemison, Katsitsionni Fox, Peter Jones, Alan Michelson, Shelley Niro, Ryan Rice, and Jolene Rickard among others. In 2008 Ryan Rice would curate Kwah I:ken Tsi Iroquois (Oh so Iroquois/Tellement Iroquois) in the Ottawa Art Gallery in Canada. It featured work by twenty-three prominent Haudenosaunee artists working in a variety of media from painting, assemblage, video, site-specific installations, and sculpture. All of these artists are represented in major museums and private collections at this point and several have shown work at international venues like the biennials of Venice, Sao Paulo, and Sydney. There are no formal definitions of Haudenosaunee art, but these artists all show a deep regard for the cultural heritage that formed them and their culture’s visual sovereignty, which they uphold in their work.

We frequently hear discussions about Indigenous sovereignty in today’s political discourse; our right to self-governance and political autonomy is by its very nature at odds with the settler colonial nation states in which we live. Added to that general political struggle are specific notions such as linguistic sovereignty, food sovereignty, and visual sovereignty (

Raheja 2010, pp. 198–200). In each case, Native communities are reclaiming the sovereign identities that they were denied through attempts at assimilating Indigenous peoples into the American or Canadian cultural mainstream. We were systematically denied the right to speak our languages, produce and procure our traditional foods, and value and practice our own cultural aesthetics and the arts. There is no easy definition for visual sovereignty but the Indigenous artists who resist prescriptive definitions of what is or is not art, or conversely, what is or is not authentically Indian, are engaging in a praxis of visual sovereignty. The roots of collecting Haudenosaunee art from the modern era are entangled with the ethnographic projects of the Rochester Museum and the WPA and larger desires for cultural revival held by the Haudenosaunee artists involved in those early projects. While traditional handicrafts among the Haudenosaunee were indeed reclaimed at this cultural low point in our communities, the Seneca Arts Project also opened a way for Haudenosaunee artists interested in non-traditional media such as drawing and painting to make professional advances through public arts commissions, published illustrations, and museum collections. Their success, while modest and regional at the outset, signaled to a younger generation in their home communities the possibilities that existed for Haudenosaunee artists beyond our traditional crafts and the venues in which they were sold. Young artists from our small constellation of reservations in the U.S. and Canada began to imagine themselves as artists, and more importantly, as Haudenosaunee artists.