Monsters of Military Might: Elephants in Hellenistic History and Art †

Abstract

1. A Behemoth of a Monster

2. From Alexander to Hannibal

3. From Rome to India

4. Elephants as Religious Symbols

The victory in question is the aforementioned Battle of Raphia (217 bce), in which Ptolemy’s African elephants had faced Antiochus’ Asian elephants.104 The Platonic philosopher Plutarch refrains from mentioning the name of the god who appeared in Ptolemy’s nightmare. Aelian, evidently paraphrasing the same text by Ptolemy IV, however, makes clear that the deity in question was Helius.105 The implication thus being that because elephants are religious animals that worship the sun god by lifting up their trunks to the heavens at dawn—as they may have done at the morning before the battle—they are beloved by Helius, who therefore was angered that Ptolemy had slaughtered four as offering to the god.For, after he [Ptolemy] had defeated Antiochus [III], he wished to pay the divine extraordinary honor for his victory in battle [at Raphia], he sacrificed four elephants among many other offerings. The next night he had dreams in which the deity angrily threatened him because the sacrifice was unwelcome to him. [Ptolemy] performed many rites of placation and set up bronze [statues of] elephants instead of the four he had slaughtered.103

5. Alexander’s Exuvia Elephantis

6. Triumph of Fame over Death

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMC | Archaeological Museum of Cherchell. |

| ANS | American Numismatic Society, New York. |

| APM | Allard Pierson Museum, the archaeological collection of the University of Amsterdam. |

| AS-SMB | Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin [Antiquities Collection, State Museum of Berlin]. |

| BM | British Museum, London. |

| BMCRR II | Grueber, H. A. 1970. Coins of the Roman Republic in the British Museum, II: Coinages of Rome (continued), Roman Campania, Italy, the Social War, and the Provinces. London: British Museum. |

| CNG | Classical Numismatic Group, London. |

| GRMA | Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria. |

| I.Cair. | Kamal, A. B. 1904–1905. Stèles ptolémaïques, CG 22001-22208, 2 vols. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale. |

| Louvre | Musée du Louvre, Paris. |

| MAR | Musée Archéologique de Rabat/Musée de l’histoire et des civilisations [Archaeological Museum of Rabat/Museum of History and Civilizations], Morocco. |

| MFA | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

| MMA | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. |

| MNAC | Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya [National Art Museum of Catalonia], Barcelona. |

| MNE | Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia [National Etruscan Museum, “Villa Giulia”], Rome. |

| RCC | Crawford, M. H. 1974. Roman Republican Coinage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| SHM | State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. |

| SNG BM Spain | Meadows, Andrew R. and Peter Bagwell-Purefoy. 2002. Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum IX: The British Museum, II: Spain, London: British Museum. |

| SNG Cop. | Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum, Denmark, The Royal Collection of Coins and Medals. Copenhagen: Danish National Museum. |

| UCL | University College London, Petrie Museum, London. |

| V&A | Victoria and Albert Museum, London. |

| WAM | Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Md. |

References

- Abdullaev, Kazim. 2017. The Image of Alexander the Great in Small-Form Art in Bactria (and Identification of the Depiction of a Warrior on the Gold Clasp from Tillya Tepe). Ancient West and East 16: 155–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia, Roda. 2008. Rajput Painting: Romantic, Divine and Courtly Art from India. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, John. 1936. Catalogue of the Coins of Ancient India. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allard Pierson Museum. 1937. Algemeene Gids. Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Troncoso, Víctor. 2013. The Diadochi and the Zoology of Kingship: The Elephants. In After Alexander: The Age of the Diadochi. Edited by Edward M. Anson and Víctor Alonso Troncoso. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 254–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini, Laura. 2005. Su un nuovo guttus configurator ad elefante da Anzio. Mediterranea 2: 165–87. [Google Scholar]

- Amela Valverde, Luis. 2013. De nuevo sobre le denario de César con elefante (RRC 443/1). Minerva 26: 145–62. [Google Scholar]

- Anson, Edward M. 2003. Alexander and Siwah. Ancient World 34: 117–30. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, U. P. 1992. The Indika of Megasthenes: An Appraisal. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 72: 307–29. [Google Scholar]

- Asheri, David, Alan B. Lloyd, Aldo Corcella, Oswyn Murray, and Alfonso Moreno. 2007. A Commentary on Herodotus Books I–IV. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baradez, J. 1960. Un grand bronze de Juba II témoin de l’ascendance mythique de Ptolémée de Maurétanie. Bulletin d’Archéologie Marocaine 4: 117–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baratte, François. 1986. Le Trésor D’orfèvrerie Romaine de Boscoreale. Paris: Louvre. [Google Scholar]

- Barbantani, Silvia. 2002. Callimachus and the Contemporary Historical ‘Epic’. Hermathena 173: 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel. 1989. Judas Maccabaeus: The Jewish Struggle against the Seleucids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartelink, Gerard J. M. 1972. Het fabeldier martichoras of mantichora. Hermeneus 43: 169–74, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Basham, Arthur L. 1989. The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belenitskii, Aleksandr M., and Boris I. Marshak. 1981. The Paintings of Sogdiana. In Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. Edited by Guitty Azarpay. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 11–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharji, Sukumari. 1970. The Indian Theogony: A Comparative Study of Indian Mythology from the Vedas to the Purāṇas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Robert Steven. 2007. The Nahman Alexander. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 43: 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Robert Steven. 2010. [Review:] the Bronzes of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, by Wendy A. Cheshire. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 46: 265–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bieber, Margarete. 1965. The Portraits of Alexander. Greece & Rome 12: 183–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bigwood, J. M. 1993. Aristotle and the Elephant Again. American Journal of Philology 114: 537–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. 1993. On the So-Called Earliest Representation of Ganesa. Topoi 3: 425–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopearachchi, Osmund, and Philippe Flandrin. 2005. Le Portrait d’Alexandre le Grand: Histoire D’une Découverte pour L’humanité. Monaco: Rocher. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Puche, Francisco. 2013. The Egyptian Royal Titulary of Alexander the Great, I: Horus, Two-Lades, Golden Horus, and Throne Names. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 99: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Puche, Francisco. 2014. The Egyptian Royal Titulary of Alexander the Great, II: Personal Name, Empty Cartouches, Final Remarks, and Appendix. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 100: 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, Natasja. 2018. Dakṣiṇa Kosala. A Rich Centre of Early Śaivism. Groningen: Barkhuis. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, A. Brian. 1988. Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, A. Brian. 1996. The Historical Setting of Megasthenes’ Indica. Classical Philology 91: 11–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, Mary. 1979. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bracey, Robert. 2011. [Review:] the Alexander Medallion: Exploring the Origins of a Unique Artifact, by F. L. Holt, O. Bopearachchi. Numismatic Chronicle 171: 487–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, Adam L., Yohannes Hagos, Yohannes Yacob, Victor A. David, Nicholas J. Georgiadis, Jeheskel Shoshani, and Alfred L. Roca. 2014. The Elephants of Gash-Barka, Eritrea: Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genetic Patterns. Journal of Heredity 105: 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, Agnes B. 1955. Catalogue of Greek Coins. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Bricault, Laurent. 1999. Sarapis et Isis: Sauveurs de Ptolémée IV à Raphia. Chronique d’Égypte, 334–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Truesdell S. 1955. The Reliability of Megasthenes. American Journal of Philology 76: 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, Stanley M. 2008. Elephants for Ptolemy II: Ptolemaic Policy in Nubia in the Third Century BC. In Ptolemy II Philadelphus and His World. Edited by Paul McKechnie and Philippe Guillaume. Leiden: Brill, pp. 135–47. [Google Scholar]

- Çakırlar, Canan, and Salima Ikram. 2016. ‘When Elephants Battle, the Grass Suffers’: Power, Ivory and the Syrian Elephant. Levant 48: 167–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callataÿ, François de. 2013. Pourquoi le ‘distatère en or au portrait d’Alexandre’ est très probablement un faux modern. Revue Numismatique 6: 175–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Thomas P. 2004. New Evidence on ‘Triumphs of Petrarch’ Tapestries in the Early Sixteenth Century. Part I: The French Court. Burlington Magazine 146: 376–85. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Thomas P. 2007. Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty: Tapestries at the Tudor Court. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, Elizabeth D. 1996. Macedonians and Mutiny: Discipline and Indiscipline in the Army of Philip and Alexander. Classical Philology 91: 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, Lionel. 1993. Ptolemy II and the Hunting of African Elephants. Transactions of the American Philological Association 123: 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, Adolfo S. 1993. Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Chamoux, François. 1988. Pergame et les Galates. Revue des Études Grecques 101: 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Michael B. 2007. Elephants at Raphia: Reinterpreting Polybius 5.84–5. Classical Quarterly 57: 306–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

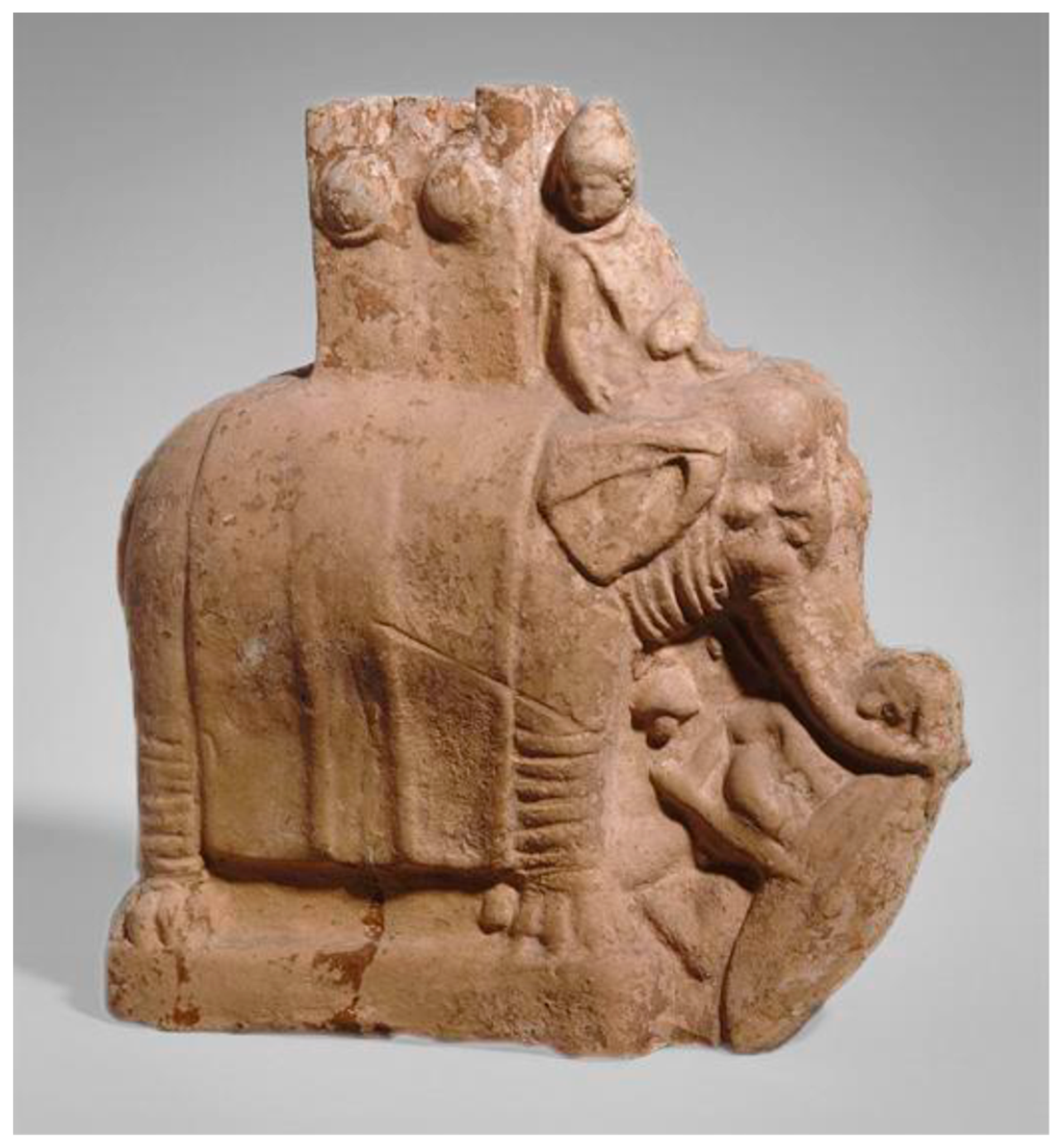

- Charles, Michael B. 2008. Alexander, Elephants and Gaugamela. Mouseion 8: 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Michael B. 2008. African Forest Elephants and Turrets in the Ancient World. Phoenix 62: 338–62. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Michael B. 2014. Carthage and the Indian Elephant. L’Antiquité Classique 83: 115–27. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Michael B. 2016. Elephant Size in Antiquity: DNA Evidence and the Battle of Raphia. Historia 65: 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Michael B., and Peter Rhodan. 2007. ‘Magister Elephantorum’: A Reappraisal of Hannibal’s Use of Elephants. Classical World 100: 363–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, George H. 1948. Three Hellenistic Coins. Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 46: 39–42. [Google Scholar]

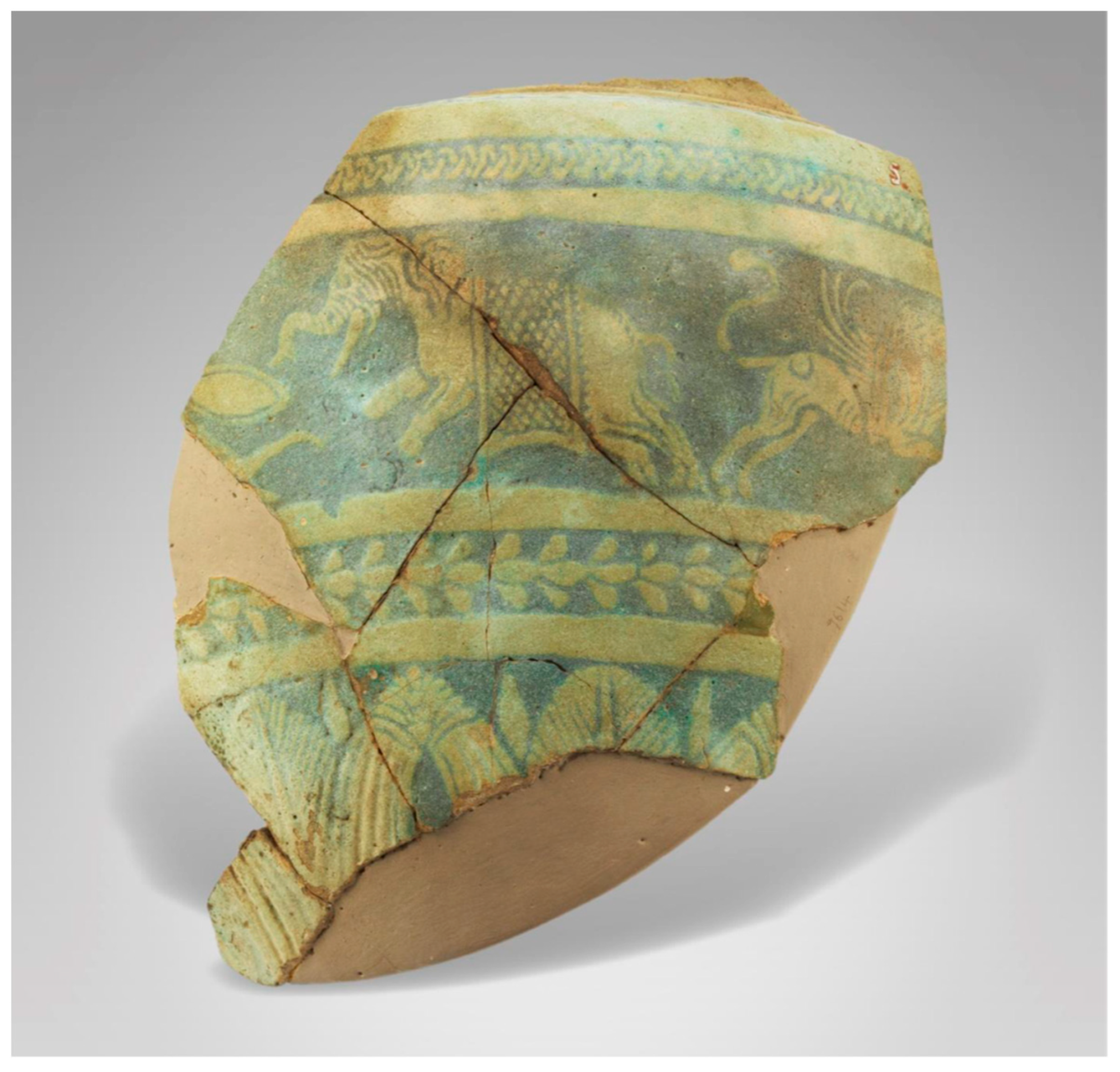

- Cheshire, Wendy A. 2009. The Bronzes of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. A gypten und Altes Testament, 77. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

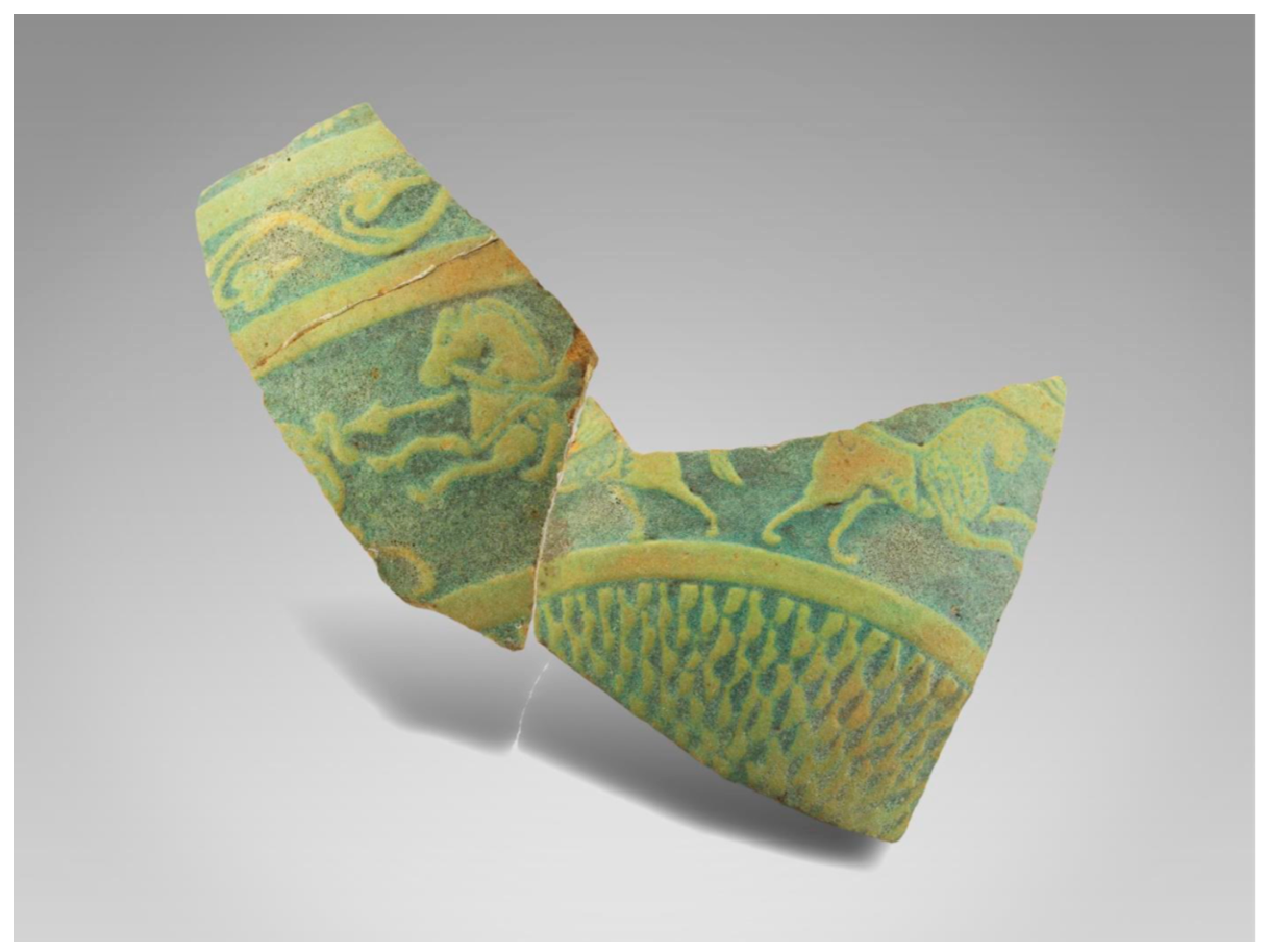

- Chugg, Andrew M. 2007. Is the Gold Porus Medallion a Lifetime Portrait of Alexander the Great? The Celator 21: 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Coarelli, Filippo. 2014. La Gloria dei Vinti: Pergamo, Atene, Roma. Milan: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, Matthew. 2016. The Decline of Ptolemaic Elephant Hunting: An Analysis of the Contributory Factors. Greece & Rome 63: 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Andrew W. 2012. The Royal Costume and Insignia of Alexander the Great. American Journal of Philology 133: 371–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Andrew W. 2014. Alexander’s Visit to Siwah: A New Analysis. Phoenix 68: 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltelloni-Trannoy, Michèle. 2000. Les représentations de l’‘Africa’ dans les monnayages africains et romains à l’époque républicaine. In Numismatique, Langues, Écritures et Arts du Livre, Spécificité des Arts Figures. Edited by S. Lancel. Paris: Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, Altay. 2012. Deconstructing a Myth of Seleucid History: The So-Called ‘Elephant Victory’ Revisited. Phoenix 66: 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlquist, Allan. 1977. Megasthenes and Indian Religion: A Study in Motives and Types. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Dahmen, Karsten. 2007. The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Danielou, Alain. 1979. Shiva et Dionysos: La Religion de la Nature et de L’EROS–de la Préhistoire à L’avenir. Paris: Fayard. [Google Scholar]

- Darbyshire, Gareth, Stephen Mitchell, and Levent Vardar. 2000. The Galatian Settlement in Asia Minor. Anatolian Studies 50: 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayet, Maurice. 1960. Carnet de numismatique celtique, VII: Le denier de César au type de l’éléphant. Revue Archéologique de l’Est et du Centre-Est 9: 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dhavalikar, M. K. 1990. Origin of Gaṇeśa. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 71: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Draycott, Jane. 2012. Dynastic Politics, Defeat, Decadence and Dining: Cleopatra Selene on the So-Called ‘Africa’ Dish from the Villa della Pisanella at Boscoreale. Papers of the British School at Rome 80: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewer, Lois. 1981. Leviathan, Behemoth and Ziz: A Christian Adaptation. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 44: 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Jacob. 2001. The Irony of Hannibal’s Elephants. Latomus 60: 900–5. [Google Scholar]

- Epplett, Christopher. 2007. War Elephants in the Hellenistic World. In Alexander’s Empire: Formulation to Decay. Edited by Waldemar Heckel, Lawrence A. Tritle and Pat V. Wheatley. Claremont: Regina, pp. 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Foltz, Richard. 2013. Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present. London: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricksmeyer, Ernst A. 1991. Alexander, Zeus Ammon, and the Conquest of Asia. Transactions of the American Philological Association 121: 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricksmeyer, Ernst A. 1997. The Origin of Alexander’s Royal Insignia. Transactions of the American Philological Association 127: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulinska, Agnieszka. 2012. Oriental Imagery and Alexander’s Legend in Art: Reconnaissance. In The Alexander Romance in Persia and the East. Edited by Richard Stoneman, Kyle Erickson and Ian Netton. Eelde: Barkhuis, pp. 383–404. [Google Scholar]

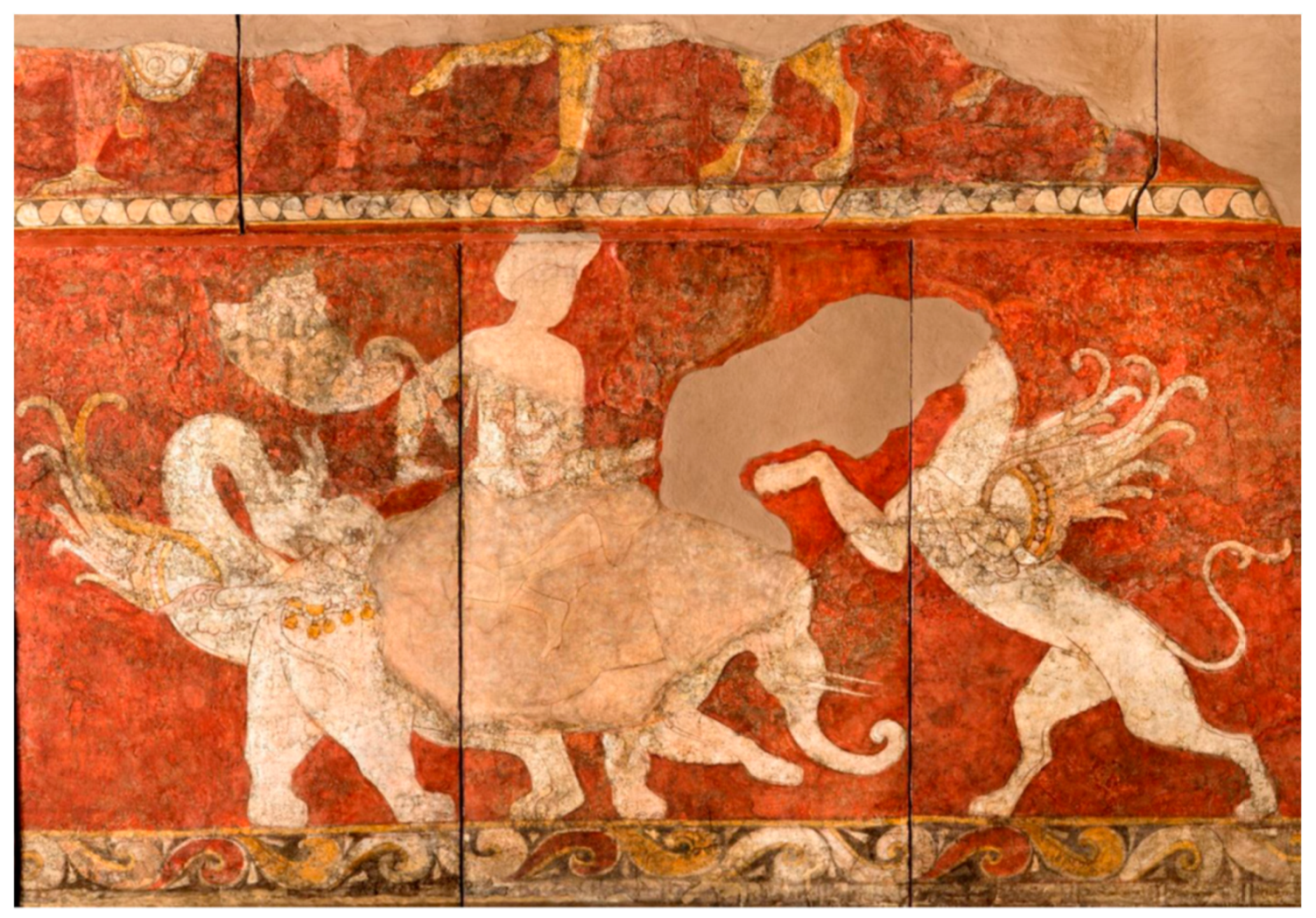

- Glover, Richard. 1944. The Elephant in Ancient War. Classical Journal 39: 257–69. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, Richard. 1948. The Tactical Handling of the Elephant. Greece & Rome 17: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Göbl, Robert. 1984. System und Chronologie der Münzprägung des Kušānreiches. Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Gorshenina, Svetlana, and Claude Rapin. 2001. De Kaboul à Samarcande: Les Archéologues en Asie Centrale. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Goukowsky, Paul. 1972. Le roi Pôros, son éléphant et quelques autres (en marge de Diodore xvii, 88, 6). Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 96: 473–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

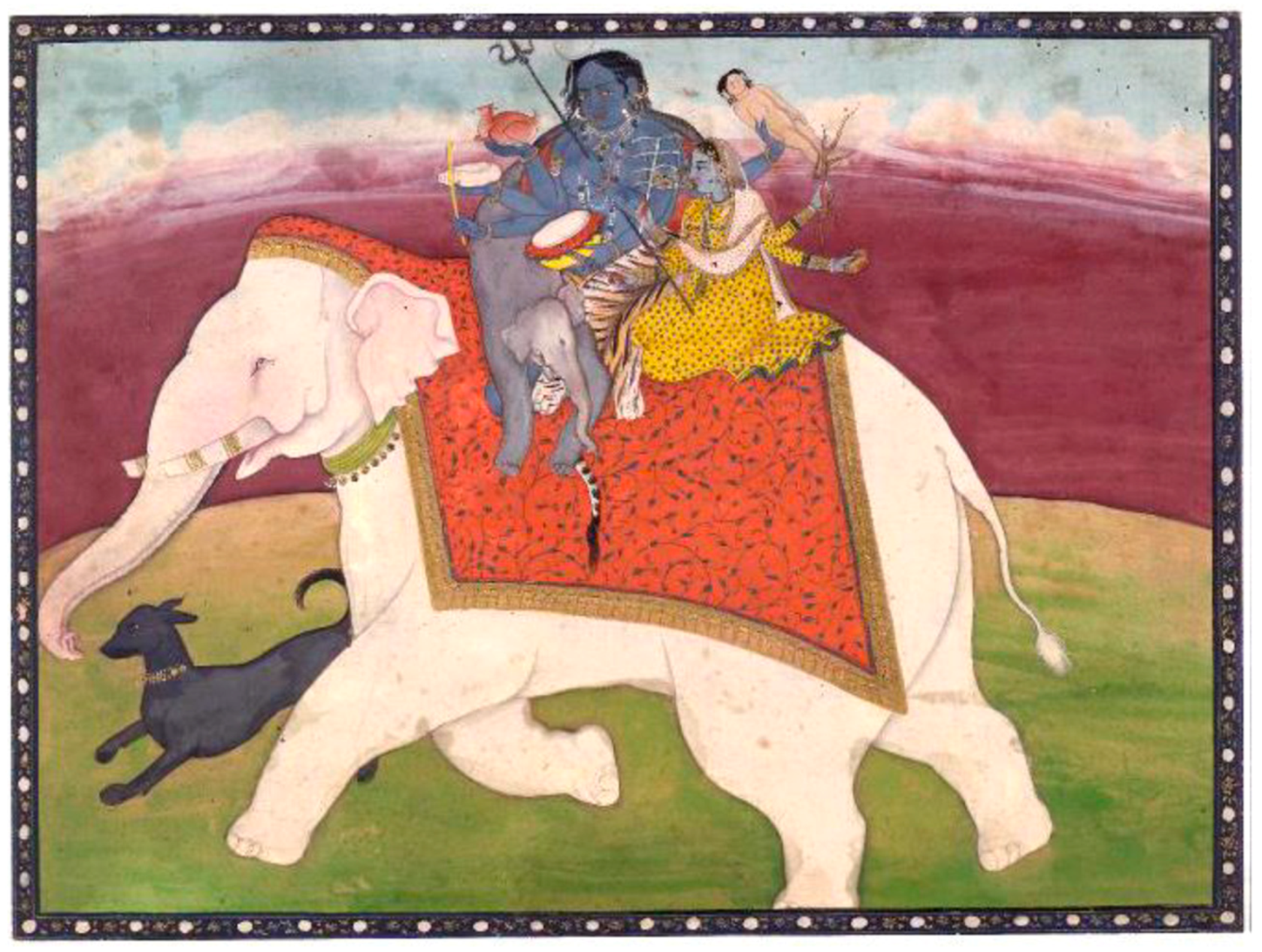

- Gowers, William. 1947. The African Elephant in Warfare. African Affairs 46: 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowers, William. 1948. African Elephants and Ancient Authors. African Affairs 47: 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, John D. 2010. The Syrian Wars. Mnemosyne, Suppl. 320. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Grüssinger, Ralf, Volker Kästner, and Andreas Scholl, eds. 2011. Pergamon: Panorama der Antiken Metropole. Berling: Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Hackstein, Olav. 2003. Apposition and Word-Order Typology in Indo-European. In Language in Time and Space: A Festschrift for Werner Winter on the Occasion of His 80th Birthday. Edited by Brigitte L. M. Bauer and Georges-Jean Pinault. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 131–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, Robert A. 1974. Royal Propaganda of Seleucus I and Lysimachus. Journal of Hellenic Studies 94: 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Nicholas G. L. 1988. Which Ptolemy Gave Troops and Stood as Protector of Pyrrhus’ Kingdom? Historia 37: 405–13. [Google Scholar]

- Henrichs, Albert. 1978. Greek Maenadism from Olympias to Messalina. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 82: 121–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héron de Villefosse, Antoine. 1899. Le trésor de Boscoreale. Monuments et Mémoires Publiés par L’académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, Fondation Eugène Piot 5: 1–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Inge. 1970. Zur Kombination von Elefant und Riesenschlange im Altertum. Anthropos 65: 625–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein, Wilhelm. 1995. Münzen des Ptolemaios Keraunos. Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau 74: 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Frank L. 2003. Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Frank L., and Osmund Bopearachchi, eds. 2011. The Alexander Medallion: Exploring the Origins of a Unique Artefact. Rouqueyroux: Lattara. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, A. Arthur, and Catharine C. Lorber. 2002. Seleucid Coins: A Comprehensive Catalogue I: Seleucus I through Antiochus III. 2 vols. New York: American Numismatic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Seymour. 1983. The Dying Gaul, Aigina Warriors, and Pergamene Academicism. American Journal of Archaeology 87: 483–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, Timothy. 2013. The Diadochi, Invented Tradition, and Alexander’s Expedition to Siwah. In After Alexander: The Time of the Diadochi, 323–281 bce. Edited by Víctor Alonso Troncoso and Edward M. Anson. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Timothy, and Sabine Müller. 2012. Mission Accomplished: Alexander at the Hyphasis. Ancient History Bulletin 26: 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyte, John. 1960. Trunk Road for Hannibal: With an Elephant over the Alps. London: Bles. [Google Scholar]

- Hsing, I-Tien. 2005. Heracles in the East: The Diffusion and Transformation of His Image in the Arts of Central Asia, India, and Medieval China. Asia Major 18: 103–54. [Google Scholar]

- Iossif, Panagiotis P., and Catharine C. Lorber. 2010. The Elephantarches Bronze of Seleucos I Nikator. Syria 87: 147–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Gilbert K. 1960. An Early Ptolemaic Hoard from Phacous. American Numismatic Society Museum Notes 9: 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, Li, ed. 2003. The Glory of the Silk Road: Art from Ancient China. Dayton: Dayton Art Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Scott C. 2013. Corporeal Discourse in the Book of Job. Journal of Biblical Literature 132: 845–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jurriaans-Helle, Geralda. 2011. Een nieuw muntenkabinet. Allard Pierson Mededelingen 104: 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Karttunen, Klaus. 1997. India and the Hellenistic World. Helsinki: Finnish Oriental Society. [Google Scholar]

- King, Carol J. 2013. Plutarch, Alexander, and Dream Divination. ICS 38: 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnier Wilson, James V. 1975. A Return to the Problems of Behemoth and Leviathan. Vetus Testamentum 25: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiy, Evgeniy, Pavel Lurje, and Kira Samosyuk, eds. 2014. Expedition Silk Road: Journey to the West–Treasures from the Hermitage. Amsterdam: Hermitage. [Google Scholar]

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. 2007. A Survey of Hinduism, 3rd ed. Albany: State University of New York. First published 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, David. 2013. Who Was with Antiochos III at Raphia? Revisiting the Hieroglyphic Versions of the Raphia Decree (CG 31008 and 50048). Chronique d’Égypte 87: 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmin, Paul J. 2014. The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krishan, Yuvraj. 1994. Evolution of Gaṇeśa. East and West 44: 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Krishan, Yuvraj. 1999. Gaṇeśa: Unravelling an Enigma. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrieleis, Helmut. 1975. Bildnisse der Ptolemäer. Berlin: Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Landwehr, Christa. 2007. Les portraits de Juba II, roi de Maurétanie, et de Ptolémée, son fils et successeur. Revue Archéologique 2007: 65–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane Fox, Robin. 1996. Text and Image: Alexander the Great, Coins and Elephants. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 41: 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Li Causi, Pietro. 2003. Sulle Tracce del Manticora: La Zoologia dei Confini del Mondo in Grecia e a Roma. Palermo: Palumbo. [Google Scholar]

- Linfert, A. 1984. Die Tochter, nicht die Mutter: Nochmals zur ‘Afrika’ Schale von Boscoreale. In Alessandria e il Mondo Ellenistico-Romano: Studi in Onore di Achille Adriani. Edited by Nicola Bonacasa and Antonino Di Vita. Rome: Bretschneider, pp. 351–58. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Robert N. 1999. Ruthless Compassion: Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art. London: Serindia. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J. Bruce. 1971. Śiva and Dionysos: Visions of Terror and Bliss. Numen 18: 180–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lorber, Catharine C. 2011. Theos Aigiochos: The Aegis in Ptolemaic Portraits of Divine Rulers. In More than Men, Less than Gods. Edited by Panagiotis P. Iossif, Andrzej S. Chankowskki and Catharine C. Lorber. Louvain: Peeters, pp. 293–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lorber, Catharine C. 2012. An Egyptian Interpretation of Alexander’s Elephant Headdress. American Journal of Numismatics 24: 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lorber, Catharine C. 2018. Coins of the Ptolemaic Empire I: Ptolemy I through Ptolemy IV. 2 vols. New York: American Numismatic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, Ernest J. H. 1935. The Indus Civilization. London: Dickson and Thomson. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Richard. 2007. The Splitting of Skanda: Distancing and Assimilation Narratives in the Mahābhārata and Ayurvedic Sources. Journal of the American Oriental Society 127: 447–70. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, Jessie A. 2001. The Image of Africa: The Evidence of the Coinage. Acta Classica 44: 105–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, Jessie A. 2004a. Putting ‘Africa’ on the Map. Acta Classica 47: 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, Jessie A. 2004b. The Face of Alexandria–The Face of Africa? In Alexandria, Real and Imagined. Edited by Anthony Hirst and Michael Silk. London: Ashgate, pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, Jessie A. 2006. ‘Dea Africa’: Examining the Evidence. Scholia 15: 102–21. [Google Scholar]

- Massiera, Magali. 2015. Des serpents entrelacés et des éléphants: Enquête sur des motifs prédynastiques. In Apprivoiser le Sauvage/Taming the Wild. Edited by Magali Massiera, Bernard Mathieu and Frédéric Rouffet. Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry, pp. 245–61. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, Michael W. 2009. Gaurīśikhara: Temple as an Ocean of Story. Artibus Asiae 69: 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Stephen. 1993. Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchiner, Michael. 1975. Indo-Greek and Indo-Scythian Coinage: The Early Indo-Greeks and Their Antecedents. London: Hawkins. [Google Scholar]

- Moormann, Eric M. 2000. Ancient Sculpture in the Allard Pierson Museum. Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Muntz, Charles E. 2012. Diodorus Siculus and Megasthenes: A Reappraisal. Classical Philology 107: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, K. Krishna. 1985. Mythical Animals in Indian Art. New Delhi: Abhinav. [Google Scholar]

- Narain, A. K. 1991. Gaṇeśa: A Protohistory of the Idea and the Icon. In Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. Edited by Robert L. Brown. Albany: State University of New York, pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, Percy E. 1944. The Elephant’s Trunk Called its drt (ḏrt) ‘Hand’. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 30: 75. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, Hélène. 1978. Monnaies à l’éléphant. Bulletin de la Société française de Numismatique 33: 401–3. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet-Pierre, Hélène. 1995. Ptolémée en Suisse. Gazette Numismatique Suisse 45: 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nock, Arthur D. 1928. Notes on Ruler-Cult, I–IV. Journal of Hellenic Studies 48: 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousek, Debra Lynn. 2008. Turning Points in Roman History: The Case of Caesar’s Elephant Denarius. Phoenix 62: 290–307. [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty, Wendy D. 1980. Dionysus and Śiva: Parallel Patterns in Two Pairs of Myths. History of Religions 20: 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, Daniel. 1999. Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death: The Hellenistic Dynasties. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Pajón Leyra, Irene. 2012. Artemidorus Behind Artemidorus: Geographic Aspects in the Zoological Designs of the Artemidorus Papyrus. Historia 61: 336–61, 366–67. [Google Scholar]

- Parlasca, Klaus. 2004. Alexander Aigiochos: Das Kultbild des Stadtgründers von Alexandria in Ägypten. Stadel-Jahrbuch 19: 340–62. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, Sylvain. 2013. Elephants and Bells in the Greco-Roman World: A Link between the West and the East? Music in Art: Images of Music-Making and Cultural Exchange between the East and the West 38: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pfrommer, Michael. 1993. Metalwork from the Hellenized East: Catalogue of the Collections. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Picón, Carlos A., and Seán Hemingway, eds. 2016. Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, Wilfried. 2013. [Compte-rendu:] F. Holt et O. Bopearachchi, The Alexander Medallion (2011). Topoi 18: 623–30. [Google Scholar]

- Plantzos, Dimitris. 2002. Alexander of Macedon on a Silver Intaglio. Antike Kunst 45: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Possehl, Gregory L. 1993. Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Pottier, Edmund, Salomon Reinach, and Alphonse Veyries. La Nécropole de Myrina: Recherches Archéologiques Exécutées au nom et au Frais de l’École Française d’Athènes. 2 vols. Paris: École Française d’Athènes, 1887–1888.

- Price, Martin J. 1991. Circulation at Babylon in 323 b.c. In Mnemata: Papers in Memory of Nancy M. Waggoner. Edited by William E. Metcalf. New York: American Numismatic Society, pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Prignitz, Sebastian. 2008. Der Pergamonaltar und die Pergamenische Gelehrtenschule. Berlin: Arenhövel. [Google Scholar]

- Puskás, Ildikó. 1990. Magasthenes and the ‘Indian Gods’ Herakles and Dionysos. Mediterranean Studies: Greece and the Mediterranean 2: 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rance, Philip. 2009. Hannibal, Elephants and Turrets in Suda Θ 438 [Polybius fr. 162b]: An Unidentified Fragment of Diodorus. Classical Quarterly 59: 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsberg, Carola. 2005. Alexander-Porträts. In Ägypten, Griechenland, Rom: Abwehr und Berührung. Edited by Herbert Beck, Peter C. Bol and Maraike Bückling. Frankfurt: Stadelsches Kunstinstitut und Stadtische Galerie, pp. 216–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Ellen E. 1983. The Grand Procession of Ptolemy Philadelphus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Terence R. 1993. Alexander and the Ganges: The Text of Diodorus XVIII 6.2. Ancient History Bulletin 7: 84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, Duane W. 2003. The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene: Royal Scholarship on Rome’s African Frontier. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Romm, James S. 1989. Aristotle’s Elephant and the Myth of Alexander’s Scientific Patronage. American Journal of Philology 110: 566–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Jenny. 2011. Zoroastrianism: An Introduction. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield, John M. 1967. Dynastic Art of the Kushans. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, Kenneth S. 1990. Diodorus Siculus and the First Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savvoupoulos, Kyriakos, Robert Steven Bianchi, and Yasmine Hussein. 2014. Graeco-Roman Museum Series II: The Omar Toussoun Collection in the Graeco-Roman Museum. Alexandria: Bibliotheca Alexandrina. [Google Scholar]

- Scheurleer, Robert A. Lunsingh. 1979. Elephants in Faience. Babesch 54: 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Pierre. 2009. De l’Hydaspe à Raphia: Rois, éléphants et propagande d’Alexandre le Grand à Ptolémée IV. Cchronique d’Égypte 84: 310–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullard, Howard H. 1974. The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, Jo-Ann. 2006. Elephants as Enemies in Ancient Rome. Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 32: 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin, Vasily A. 1963. Bapaxшa [Varakhsha]. Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sick, David H. 2002. An Indian Perspective on the Graeco-Roman Elephant. Ancient World 33: 126–46. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Upinder. 2009. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Delhi: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Roland R. R. 1988. Hellenistic Royal Portraits. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, C. E. 1959. Julius Caesar’s Elephant. History Today 9: 626–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Andrew. 1993. Faces of Power: Alexander’s Image and Hellenistic Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Frank. 2010. The Mahabharata and Andha Yug: A Brief Summary. Mānoa: Andha Yug: The Age of Darkness 22: 111–14. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, Karl. 1994. Keltensieg und Galatersieger. In Forschungen in Galatien. Edited by Elmar Schwertheim. Bonn: Habelt, pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Strootman, Rolf. 2005. Kings against Celts: Deliverance from Barbarians as a Theme in Hellenistic Royal Propaganda. In The Manipulative Mode: Political Propaganda in Antiquity—A Collection of Case Studies. Edited by Karl A. E. Enenkel and Ilja L. Pfeijffer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 101–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tafazzoli, Ahmad. 1975. Elephant: A Demotic Creature and a Symbol of Sovereignty. Acta Iranica 5: 395–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tarn, William W. 1940. Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus’ 500 Elephants; 2. Tarmita. Journal of Hellenic Studies 60: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapan, Anita R. 1997. Understanding Gaṇapati: Insights into the Dynamics of a Cult. New Delhi: Manohar. [Google Scholar]

- Thiers, Christophe. 2001. Ptolémée Philadelphe: l’exploration des côtes de la mer Rouge et la chasse à l’éléphant. Égypte, Afrique and Orient 24: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Thonemann, Peter. 2015. Pessinous and the Attalids: A New Royal Letter. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 194: 117–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tola, Fernando, and Carmen Dragonetti. 1986. India and Greece Before Alexander. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 67: 159–94. [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann, Thomas R. 2015. Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trinquier, Jean. 2013. ‘Cinnabaris’ et ‘sang-dragon’: Le ‘cinabre’ des anciens entre mineral, végétal et animal. Revue Archéologique 2013: 305–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alfen, Peter G. 2000. The ‘Owls’ from the 1973 Iraq Hoard. American Journal of Numismatics 12: 9–58. [Google Scholar]

- van Oppen de Ruiter, Branko F. 2013. Lagus and Arsinoe: An Exploration of Legendary Royal Bastardy. Historia 62: 80–107. [Google Scholar]

- van Oppen de Ruiter, Branko F. 2019. Elephants in Hellenistic History & Art. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Available online: https://www.ancient.eu/article/1381/elephants-in-hellenistic-history--art/ (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Walker, Susan, and Peter Higgs, eds. 2001. Cleopatra of Egypt: From History to Myth. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, H. B. 1926. Catalogue of Engraved Gems and Cameos: Greek, Etruscan and Roman. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, Patrick V. 2014. Seleukos and Chandragupta in Justin XV 4. In The Age of the Successors and the Creation of the Hellenistic Kingdoms, 323–276 bc. Edited by Hans Hauben and Alexander Meeus. Louvain: Peeters, pp. 501–15. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Joanna. 2000. The Eponymous Elephant of Elephanta. Ars Orientalis 30: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfers, David. 1990. The Lord’s Second Speech in the Book of Job. Vetus Testamentum 40: 474–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, David. 2009. Caesar the Elephant against Juba the Snake. Numismatic Chronicle 169: 189–92. [Google Scholar]

- Woytek, Bernhard. 2006. Die Verwendung von Mehrfachstempeln in der antiken Münzprägung und die ‘Elefantendenare’ Iulius Caesars (RRC 443/1). Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau 85: 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yalouris, Nicholas, Elisabeth Alföldi-Rosenbaum, Manoles Andronikos, John Herrmann, and Katerina Rhomiopoulou, eds. 1980. The Search for Alexander: An Exhibition; Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, Boston: Little, Brown.

- Zambrini, Andrea. 1982. Gli Ἰνδικά di Megastene. Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa 12: 71–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrini, Andrea. 1985. Gli Ἰνδικά di Megastene. Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa 15: 781–853. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | LXX Job 40:15–24 = Vulg. Job. 40.10–19; Kinnier Wilson (1975); Drewer (1981); Wolfers (1990); Jones (2013, esp. pp. 860–63). The Septuagint and Vulgate translations both diverge at times from the Hebrew original. |

| 2 | Hdt. Hist. 6.44; Plat. Phaedr. 230a; Polyb. 11.1.12. |

| 3 | Varr. Ling. Lat. 7.39–40; Plin. Nat. Hist. 8.6 (16); cf. Flor. Epit. 13.1 (18) (ferarum terrore, of elephants). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Hdt. Hist. 4.192 recognizes several types of antelopes: πύγαργοι καὶ ζορκάδες καὶ βουβάλιες (white-rump antelopes, dorcas gazelles and hartebeests); the ὄνοι κέρεα mentioned at 4.191.4 are therefore unlikely to refer to a type of antelopes; Asheri et al. (2007, pp. 714–15). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Ctes. Epit. ap. Phot. Bibl. 72 §7. For the martichora (or manticore), also see: Arist. Hist Anim. 2.1; Plin. Hist. Nat. 8.21 (30); Ael. Nat. Anim. 4.21; Paus. 9.21.4 (751); Brown (1955, pp. 22–23); Bartelink (1972); Tola and Dragonetti (1986); Romm (1989, p. 572); Bigwood (1993); Karttunen (1997, pp. 97–98); Li Causi (2003). For the Greek κιννάβαρι, see: Trinquier (2013). |

| 8 | Ctes. Epit. ap. Phot. Bibl. 72 §12; Brown (1955, p. 29); Tola and Dragonetti (1986, pp. 179–83); Karttunen (1997, pp. 27, 188). |

| 9 | Arist. Hist. Anim. 2.1, 8.9 and 9.46; Scullard (1974, pp. 37–52); Tola and Dragonetti (1986, pp. 185–88); Romm (1989, esp. pp. 572–73); Bigwood (1993); Karttunen (1997, pp. 188–89); Schneider (2009, p. 310). |

| 10 | Diod. Bibl. 2.16.2; Brown (1955, pp. 23–27); Sacks (1990, p. 76); Bigwood (1993, p. 543); Bosworth (1996, pp. 122–23); Karttunen (1997, p. 188); Schneider (2009, p. 311); Muntz (2012, pp. 23–31). |

| 11 | Strab. Geogr. 15.1.43 (705), 15.1.55 (710) and 16.4.16 (775); Brown (1955, p. 31); Scullard (1974, pp. 52–60); Karttunen (1997, pp. 190, 227); Schneider (2009, pp. 322–24); Pajón Leyra (2012, pp. 338, 349); Kosmin (2014, pp. 261–71). |

| 12 | Plin. Nat Hist. 8.11. For the mythic theme of dragons/serpents fighting elephants in antiquity, see: Hofmann (1970); Karttunen (1997, pp. 227–28); Pajón Leyra (2012, pp. 349–50); Massiera (2015) (predynastic Egypt). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Mackay (1935); Possehl (1993); Trautmann (2015); Singh (2009, pp. 132–81). For the supposed “Syrian” elephant (viz., the Asian elephant imported from India), present in the Near East in the Bronze Age (ca. 18th–8th century bce), now see: Çakırlar and Ikram (2016). |

| 19 | BM reg. no 1947,0416.5 (steatite stamp seal, Mohenjo-daro, ca. 2600–1900 BCE); cf. MFA acc. no. 36.970 (seal stamp, Chanhu-daro); Mackay (1935, pp. 69–70, 79, 140, 172, 193, pl. M); Singh (2009, p. 173). |

| 20 | Arr. Anab. 3.15.5. |

| 21 | Curt. Ruf. 5.2.10. |

| 22 | Curt. Ruf. 8.12.11; Bosworth (1988, p. 125); Karttunen (1997, pp. 31–33); Schneider (2009, p. 313). Greek and Roman authors refer to the ruler as Taxiles or Omphis, the latter probably reflects the Sanskrit name Ambhi; the ancient city from which he ruled is called Takshasila in Sanskrit. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Arr. Anab. 5.17–18. |

| 25 | Diod. Bibl. 17.89.2; cf. Philostrat. Vit. Apollon. 2.12 (relating that an elephant that fought at the Hydaspes still lived some 350 years later). |

| 26 | Diod. Bibl. 2.37.2–3, 17.93.2–4 and 18.6.1–2; Curt. Ruf. 9.2.2–9; Plut. Alex. 62.2–3 (200,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 8000 chariots, and 6000 elephants); Metz Epit. 68–69; Glover (1948, p. 1); Bosworth (1996, p. 120); Schneider (2009, p. 314); Kosmin (2014, pp. 263–64); Singh (2009, p. 273). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | BM reg. nos. 1887,0609.1 and 1926,0402.1; ANS inv. no. 1959.254.86 = SNG Berry no. 295; Bieber 1965, (pp. 185–86, pl. 1, figs. 3a–b); Scullard (1974, pp. 75–76); Nicolet (1978); Price (1991); Lane Fox (1996); Holt (2003); Dahmen (2007, pp. 109–11, pl. 2, figs. 1–2); Holt and Bopearachchi (2011); Schneider (2009, p. 316); Picón and Hemingway (2016, p. 110, no. 10a). |

| 29 | BM reg. no. 1926,0402.1 (decadrachm or five-shekel, prop. Babylon, local mint, ca. 324–321 bce). Note that Nike can only be well determined on a single specimen. |

| 30 | ANS inv. nos. 1990.1.1 and 1995.51.68 (silver tetradrachms, prob. Babylon, local mint, ca. 324–321 bce); Van Alfen (2000, pp. 9–10 (with refs.)); Picón and Hemingway (2016, p. 110, nos. 10b–c). |

| 31 | Bopearachchi and Flandrin (2005); Holt and Bopearachchi (2011); contra Chugg (2007); Bracey (2011); Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 256, with n. 6); Callataÿ (2013); cf. Pieper (2013). |

| 32 | Cf. Diod. Bibl. 18.26–28; Strab. Geogr. 17.1.8; Paus. 1.6.3; Just. Epit. 13.4.1–8. |

| 33 | Diod. Bibl. 18.27.1; A. Stewart (1993, pp. 216–21); Schneider (2009, pp. 317–18); Alonso Troncoso (2013, pp. 255–56, with n. 1). |

| 34 | Diod. Bibl. 18.2; Curt. Ruf. 10.6–9; Just. Epit. 13.2–4; Arr. Succ. ap. Phot. Bibl. 92. |

| 35 | Curt. Ruf. 10.9.1 and 16. |

| 36 | Curt. Ruf. 10.9.18; Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 256, with n. 2). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | Plut. Eum. 5.1; Arr. Succ. (ap. Phot. Bibl. 92) 28; Just. Epit. 13.6, 8; Oros. Adv. Pag. 3.23.19–20 and 23. |

| 39 | MFA acc. no. 11.1754 (gold stater, Alexandria, ca. 304–298 bce); Dahmen (2007, p. 113, pl. 4, figs. 6–7); Alonso Troncoso (2013, pp. 262–63); Lorber (2018, no. 99). |

| 40 | Cf. Athen. Deipn. 5.31–32 (200d–f); Rice 1983, (pp. 85, 90) (elephant quadrigae appearing in the Grand Procession of Ptolemy II). |

| 41 | Jenkins (1960); Bieber (1965, esp. pp. 185–86, pl. 6, fig. 12); Nicolet-Pierre (1995); Bianchi (2007); Dahmen (2007, pp. 112–13, pl. 4, figs. 1–4); Schneider (2009, pp. 320–21); Lorber (2011, pp. 299–304, figs. 2–3); Lorber (2012, p. 25, fig. 2); Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 256); Kakavas in Picón and Hemingway (2016, pp. 70–72, fig. 86). |

| 42 | |

| 43 | Bieber (1965, p. 186, pl. 7, figs. 13a–b); Hadley (1974, esp. p. 52); Dahmen (2007, pp. 116–17, pl. 6 [Agathocles of Syracuse], pp. 117–18, pl. 7, fig. 1–3 [Seleucus], pp. 119–20, pl. 8, figs. 1–4 and pp. 120–21, pl. 9 [Agathocles of Bactria]); Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 259); Picón and Hemingway (2016, fig. 93 and no. 139). |

| 44 | |

| 45 | Scullard (1974, pp. 98–100); cf. Rice (1983, pp. 90–92) (counting 96 elephants in the Grand Procession of Ptolemy II, derived from expeditions into Nubia and the Sudan). |

| 46 | CNG 101, Triton XIX (6 January 2016), lot 2037 (gold stater, Lysimachia, ca. 281–280 bce); ex CNG 72 (14 June 2006), lot 499; Hollstein (1995, fig. 3 [Leu 50, 25 April 1990, lot 93]); Picón and Hemingway (2016, fig. 93). |

| 47 | |

| 48 | Diod. Bibl. 22.3; Just. Epit. 24.4–8; Paus. 10.19.7; Memn. ap. Phot. = FGrH 434, 8.8; Mitchell (1993, I: p. 13). |

| 49 | Just. Epit. 24.5.6 (Ptolomeus multis vulneribus saucius capitur; caput eius amputatum et lancea fixum tota acie ad terrorem hostium circumfertur); Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 256) (pointing out that Ceraunus is the only Hellenistic king known to have fought on the battlefield on the back of an elephant). |

| 50 | |

| 51 | Plin. Nat. Hist. 8.16; Plut. Pyrrh. 15–17; Paus. 1.12.3; Just. Epit. 8.1 and 17.2.14. |

| 52 | Trog. Prol. 17; Just. Epit. 17.2.12–15. In this passage, Justin apparently refers to three different Ptolemies indiscriminately: Ptolemy I (whose “daughter”, Antigone, was married to Pyrrhus), Ptolemy Ceraunus (who is the main subject of the chapter), and Ptolemy II (who must have been the king supplying the troops under question); Hammond (1988). |

| 53 | Dion. Rom. Ant. 20.12.3 (14); Flor. Epit. 1.12–13; Plut. Pyrrh. 25; Zonar. Epit. 8.6. |

| 54 | Sen. Brev. Vit. 13.3 (primus Curius Dentatus in triumpho duxit elephantos); Eutrop. Brev. 2.14 (Curius in consulatu triumphavit. Primus Romam elephantos quattuor duxit); Shelton (2006, p. 9). |

| 55 | MNE inv. no. 23.949 (polychrome ceramic plate, diam, 29.5 cm, Capena, ca. 275–270 bce); Bar-Kochva (1989, p. 584, pl. 12); Ambrosini (2005); Picón and Hemingway (2016, pp. 118–19, no. 21). |

| 56 | Gowers (1947, pp. 44–47); Hoyte (1960); Scullard (1974, pp. 154–77); Edwards (2001); Charles and Rhodan (2007); Rance (2009). |

| 57 | Liv. Ab Urb. Cond. 21.58.11. |

| 58 | BM reg. no. 1911,0702.1 (silver double shekel, Mogente Hoard, Spain, ca. 237–209 bce); SNG BM Spain, no. 97; Charles and Rhodan (2007, p. 367). |

| 59 | Suda θ 438 s.v. Θωράκιον; Glover (1944, p. 259); Gowers (1947, p. 43); Charles (2008b, 2014); Rance (2009). |

| 60 | Hist. Aug., Ael. 2.3 (ab elephanto, qui lingua Maurorum caesai dicitur, in proelio caeso); Scullard (1974, pp. 194–98, pl. 24d). |

| 61 | Polyaen. Strat. 8.23.5; cf. Caes. Bell. Gall. 5.18 (where no word is said about the elephant); Gowers (1947, pp. 48–49); Stevens (1959, pp. 626–28). |

| 62 | Caes. Bell. Civ. 2.40; Vell. Hist. 2.54; Suet. Jul. 39; App. Bell. Civ. 2.14.96. For the death of Juba, see: Strab. Geogr. 17.3.12; Suet. Jul. 35. |

| 63 | Suet. Jul. 36; App. Bell. Civ. 2.15.101. |

| 64 | BM reg. no. R.8822 (silver denarius, travelling mint, ca. 49/48 bce); BMCRR II: 390, no. 27, pl. 103, fig. 5; RCC no. 443/1; Dayet (1960); Hofmann (1970); Woytek (2006); Nousek (2008); Woods (2009) (pointing to an association between the serpent’s crest, iuba in Latin, and the Numidian king’s name; if correct, the association of the cognomen with the elephant might even be explicit here); Amela Valverde (2013). |

| 65 | Tac. Ann. 4.5; Plut. Alex, 36, 54, 87; Dio Cass. Hist. Rom. 49.41 and 51.15; Roller (2003, pp. 76–90). For a possible portrait of Cleopatra Selene, see: AMC inv. no. S 66(31); Walker and Higgs (2001, p. 219, no. 197 [with lit.]). |

| 66 | For a portrait bust of Juba II, see: MAR inv. no. 99.1.12.1340; Baradez (1960); Roller (2003, pp. 147–48, fig. 19); Landwehr (2007); Picón and Hemingway (2016, pp. 311–12, no. 262). |

| 67 | Louvre inv. no. Bj 1969 (silver emblema dish, discovered at the Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale, created ca. 25 bce–25 ce); Linfert (1984); Walker and Higgs (2001, pp. 312–13, no. 324); Roller (2003, pp. 141–42, fig. 16). For the Boscoreale Treasures, esp., see: Héron de Villefosse (1899, pp. 39–43, no. 1, 175–86, fig. 7, pl. 1); Baratte (1986, pp. 77–81). |

| 68 | I.Cair. 31088a (Raphia Decree); Scullard (1974, pp. 137–43); Bricault (1999); Grainger (2010, pp. s195–218). |

| 69 | Polyb. 5.65 and 79–87 (102 vs. 73 elephants resp.). |

| 70 | Glover (1944, pp. 267–69); Gowers (1947, p. 43); Glover (1948, p. 5); Gowers (1948); Karttunen (1997, pp. 194–97); Sick (2002); Charles (2007, 2016); Schneider (2009, pp. 332–34); Brandt et al. (2014). For Ptolemaic elephant hunting expedition, esp. see: Casson (1993); Thiers (2001); Burstein (2008); Cobb (2016). |

| 71 | Tarn (1940, pp. 84–89); Scullard (1974, pp. 95–100); Bosworth (1988, pp. 180–81); Bosworth (1996, pp. 119–20); Schneider (2009, p. 319); Kosmin (2014, pp. 32–33); Wheatley (2014). For the Mauryan Empire, see: Singh (2009, pp. 320–67). |

| 72 | Strab. Geogr. 15 (724), 16 (752); Plut. Alex. 62.2 and Demetr. 28.3; Glover (1944, pp. 257, 261); Gowers (1947, pp. 42–43); Glover (1948, p. 2); Schneider (2009, p. 319). |

| 73 | Diod. Bibl. 20.113 (mentioning 480 elephants); App. Syr. 62. |

| 74 | ANS inv. no. 1944.100.44992 (tetradrachm, Seleucia-on-the-Tigris mint II, ca. 296–281 bce); Hadley (1974, p. 52 n. 7, p. 58 n. 49, and p. 60); Houghton and Lorber (2002, p. 130, no. 39b); Schneider (2009, p. 320); Iossif and Lorber (2010, esp. fig. 1); Coşkun (2012, p. 66, n. 30); Alonso Troncoso (2013, pp. 260–63). |

| 75 | APM inv. no. 5147 (bronze coin, Antioch, ca. 280–261 bce); SNG Cop. 35, no. 67; Houghton and Lorber (2002, pp. 339–40); Jurriaans-Helle (2011, p. 23, fig. 5a–b); Coşkun (2012, p. 66, n. 29). |

| 76 | APM inv. no. 5148 (bronze coin, Ecbatana, ca. 228–226 bce); SNG Cop. 35, no. 146; Houghton and Lorber (2002, no. 819a). |

| 77 | App. Syr. 65.343; Scullard (1974, pp. 120–23, pl. 7b); Mitchell (1993, I: p. 18); Coşkun (2012, p. 62, n. 17, and p. 69). |

| 78 | Luc. Zeuxis 8–11; Glover (1944, pp. 260–61); Mitchell (1993, I: p. 18); Coşkun (2012, p. 63, n. 19). |

| 79 | |

| 80 | Pomp. Trog. Prol. 25; Suda s.v. Σιμωνίδης = FGrH 163f = Suppl. Hell. 723; Strootman (2005, pp. 115–17); Coşkun (2012, p. 62, n. 15, 67–68, n. 34). |

| 81 | Louvre inv. no. Myr. 284 (terracotta figurine, Myrina, ca. 3rd century bce); Pottier et al. (1887–1888, I: pp. 318–27, pl. 9); Bar-Kochva (1989, p. 586, pl. 13b); Mitchell (1993, I: p. 18); Coşkun (2012, p. 65); Perrot (2013, pp. 30–31); Picón and Hemingway (2016, p. 119, no. 22). |

| 82 | APM inv. no. 7855 (limestone stamp, diam. 18.5 cm, Egyptian Delta [?], late Roman [?]); Allard Pierson Museum (1937, p. 65, no. 578); Moormann (2000, p. 205 [with lit.], no. 277, pl. 95a). |

| 83 | |

| 84 | Mitchell (1993, I: p. 21); Strootman (2005, pp. 122–29); Prignitz (2008); Grüssinger et al. (2011); A. Scholl in Picón and Hemingway (2016, pp. 44–53, figs. 53–63). |

| 85 | |

| 86 | AS-SMB inv. no. AvP VII 265 (marble relief block, h. 15 cm, Pergamon, ca. 3rd–1st century bce); Grüssinger et al. (2011, pp. 466–67, no. 3.41); Picón and Hemingway (2016, p. 131, no. 38). |

| 87 | APM inv. no. 7614 (faience sherd, Memphis [?], ca. 3rd century bce); cf. APM inv. no. 7569 (kneeling warrior, winged sphynx and partial elephant trunk); Allard Pierson Museum (1937, p. 177, nos. 1623–1624); Scheurleer (1979, pp. 100–1, no. 2, figs. 2–4, and cf. nos. 1 and 3, figs. 1 and 5). |

| 88 | APM inv. no. 7609 (faience sherd, Memphis [?], ca. 3rd century bce). |

| 89 | APM inv. nos. 7572 and 7578 (faience appliques, Memphis [?], ca. 3rd century bce); Allard Pierson Museum (1937, p. 177, nos. 1630–1631); Scheurleer (1979, pp. 103–4, nos. 4–5, figs. 8–9, and cf. pp. 105–06, nos. 6–7, figs. 10–17). |

| 90 | SHM inv. nos. S-64 and 65 (chased and gilded silver phalerae, diam. ca. 25cm, Eastern Iran [?], ca. 3rd–2nd century bce); Scullard (1974, pl. 12); Bar-Kochva (1989, p. 585, pl. 13a); Pfrommer (1993, p. 10, fig. 4). |

| 91 | ANS inv. no. 1995.51.23 (silver tetradrachm, Panjshir, ca. 190–171 bce); Mitchiner (1975, no. 103d); cf. Chase (1948, p. 40, fig. 4). |

| 92 | |

| 93 | Little is known about Antialcidas beside his ample coinage, except that he sent his ambassador Heliodorus of Taxila to King Bhagabhadra of the Shunga dynasty (ca. 185–75 BCE) in eastern and central India; at Besnagar (mod. Vidisha), near the Buddhist stupa’s at Sanchi, Heliodorus erected a pillar on which he declared his devotion to the Hindu deity Krishna; for which, see: Bieber (1965, pl. 1, fig. 4); Puskás (1990, p. 43); Karttunen (1997, p. 296). |

| 94 | MFA inv. no. 47.128 (silver tetradrachm, Taxila, ca. 115–95 bce); Chase (1948, p. 41, fig. 5); Brett (1955, no. 2345). |

| 95 | BM reg. no. OR.7296 (silver karshapana, Maurya, ca. 3rd century bce); Allan (1936, p. 79, no. 5, pl. 8.2); cf. Sick (2002, pp. 132–33). |

| 96 | ANS inv. no. 1948.34.1 (gold dinara, Peshawar, ca. 151–190 ce); Göbl (1984, no. 305a.2); cf. Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 269 n. 3). For the coins of Huvishka, see: Rosenfield (1967, esp. pp. 59–66). |

| 97 | For Ardochsho, see: Rosenfield (1967, pp. 74–75). |

| 98 | Diod. Bibl. 19.80–84. |

| 99 | |

| 100 | Plut. Soll. Anim. 17.1 (= Mor. 972B–C) = FGrH III: 146–147, F 51a, 53; cf. Ael. Nat. Anim. 7.44. |

| 101 | Plin. Nat. Hist. 8.1 (the reference to Mauretania indicating that Juba was the source for this statement); for similar statements, cf. Ael. Nat. Anim. 4.10; Cass. Dio 39.38.5. |

| 102 | Plut. Soll. Anim. 17.2 (= Mor. 972c); Ael. Nat. Anim. 7.2 (for a similar claim). |

| 103 | Plut. Soll. Anim. 17.2 (= Mor. 972c); cf. Ael. Nat. Anm. 7.44. |

| 104 | Supra p. 4. |

| 105 | Ael. Nat. Anm. 7.44; Lorber (2011, p. 302). Note that, in the Raphia Decree (I.Cair. CG 31.088a = CG 50.048), Ptolemy IV is hailed as youthful Horus, beloved of Isis, to whom Ra (Helius) has given victory, the living image of Amun (Zeus-Ammon); the gods and goddesses appear to the king in an oracular dream before the campaign against Antiochus III; Bricault (1999) (suggesting that Ptolemy IV honored Isis and Sarapis as his saviors at Raphia); Klotz (2013, pp. 50–51). Also note that in ancient Egyptian the elephant’s trunk is called its “hand (ḏrt)”; Newberry (1944). |

| 106 | BM reg. no. 1889,1014.60 (terracotta stamp, max. diam. 12.8 cm, Bubastis, ca. 3rd–2nd century bce); cf. UCL, Petrie Museum, inv. no. 69.097 (terracotta mould, Memphis, ca. 1st–2nd century ce); GRMA inv. no.18.759 (terracotta group, 13.5 cm, Egypt, ca. 1st–2nd century bce); Savvoupoulos et al. (2014, pp. 122–23, no. 40). |

| 107 | Athen. Deipn. 5.22 (194f–195a), 31–32 (200d–f) and 34 (202a); Rice (1983, p. 85); Schneider (2009, pp. 325–29). |

| 108 | |

| 109 | SHM inv. no. SA-14.658–675 (mural, Varachsha, ca. 720–740 ce); Shishkin (1963, pp. 54–59, 152–53, 204–5, pl. 4); Belenitskii and Marshak (1981, pp. 31–33, 47–49); Gorshenina and Rapin (2001, pp. 112–13, 155); Kiy et al. (2014, pp. 90–97, 202–3, no. 135). |

| 110 | Jian (2003, p. 161). |

| 111 | |

| 112 | For ancient Zoroastrianism, e.g., see: Boyce (1979, esp. pp. 1–12); Rose (2011, pp. 8–64); Foltz (2013, pp. 1–74). For the elephant as a symbol of sovereignty in Avestan belief, esp. see: Tafazzoli (1975). |

| 113 | Bhattacharji (1970); Murthy (1985, pp. 6, 13, 17, 28, 31–34, 46–47); Williams (2000, esp. figs. 4–5); Sick (2002); Trautmann (2015). For (ancient) Indian religion, e.g., see: Basham (1989); Klostermaier (2007, pp. 15–118); Singh (2009, pp. 182–255). |

| 114 | For the association of Shiva with Airavata, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 55, 60 and 180); Dahlquist (1977, p. 140); Danielou (1979, pp. 124, 143 and 202); Murthy (1985, pp. 13, 32); Basham (1989, p. 108); Karttunen (1997, pp. 89–90); Mann (2007, esp. pp. 449, 457). For contact between India and Greece, e.g., see: Tola and Dragonetti (1986); Karttunen (1997, pp. 1–18, 26–30). |

| 115 | BM reg. no. 1925,1016,0.15 (tantric gouache painting, Pahari School, Punjab, ca. 1790–1800); Ahluwalia (2008, p. 159, fig. 106). |

| 116 | For Bhairava and the elephant skin, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 130, 197 and 205); Long (1971, pp. 192, 205); Dahlquist (1977, p. 73); Basham (1989, p. 108); Linrothe (1999, pp. 123–24, 252–53 and 277–303); Klostermaier (2007, pp. 109, 230–31); Bosma (2018, p. 168, n. 462, pp. 190–91, 276). |

| 117 | Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 141, 159, 183–84, 193); Danielou (1979, pp. 74, 114); Murthy (1985, pp. 31–34, pl. 7, figs. 49–50); Basham (1989, p. 108); Dhavalikar (1990) (drawing a direct connection between Ganesha and Alexander the Great); Narain (1991); Krishan (1994, 1999); Bopearachchi (1993); Karttunen (1997, p. 311); Williams (2000, fig. 6); Klostermaier (2007, esp. pp. 4–5); Meister (2009, pp. 296–98, 313–15). |

| 118 | For the association of Ganesha with Vināyaka, see: Bhattacharji (1970, p. 183); Murthy (1985, p. 32); Narain (1991, pp. 22–23); Krishan (1994, 1999); Thapan (1997); Linrothe (1999, pp. 20, 45–46, 90, 139 and 214). |

| 119 | Fredricksmeyer (1997, p. 102); Plantzos (2002); Schneider (2009, pp. 320–21); Fulinska (2012); Lorber (2012); Alonso Troncoso (2013, p. 257); Collins (2012, p. 382). While the headband is worn over the forehead, like the Dionysian mitra, I understand its function on Alexander’s portrait as an intentional reference to the royal fillet (diadēma), thus drawing an implicit connection between both. |

| 120 | |

| 121 | E.g., (a.) Bonhams, London, 25 April 2012, lot 43 (bronze applique, 4 cm, unknown provenance, ca. 3rd century bce); (b.) SHM inv. no. GR-27.178 (bronze figurine, 5.7 cm, unknown provenance, ca. 2nd–1st century bce); cf. BM reg. no. 1871,0619.4 (bronze applique, 4.8 cm, Egypt, Graeco-Roman) and 1858,0526.11 (bronze applique, 3.4 cm, Egypt, Graeco-Roman); MMA acc. no. 26.7.1430 (bronze applique, 5 cm, Egypt, ca. 2nd century bce–1st century ce); Yalouris et al. (1980, p. 123, pl. 46). |

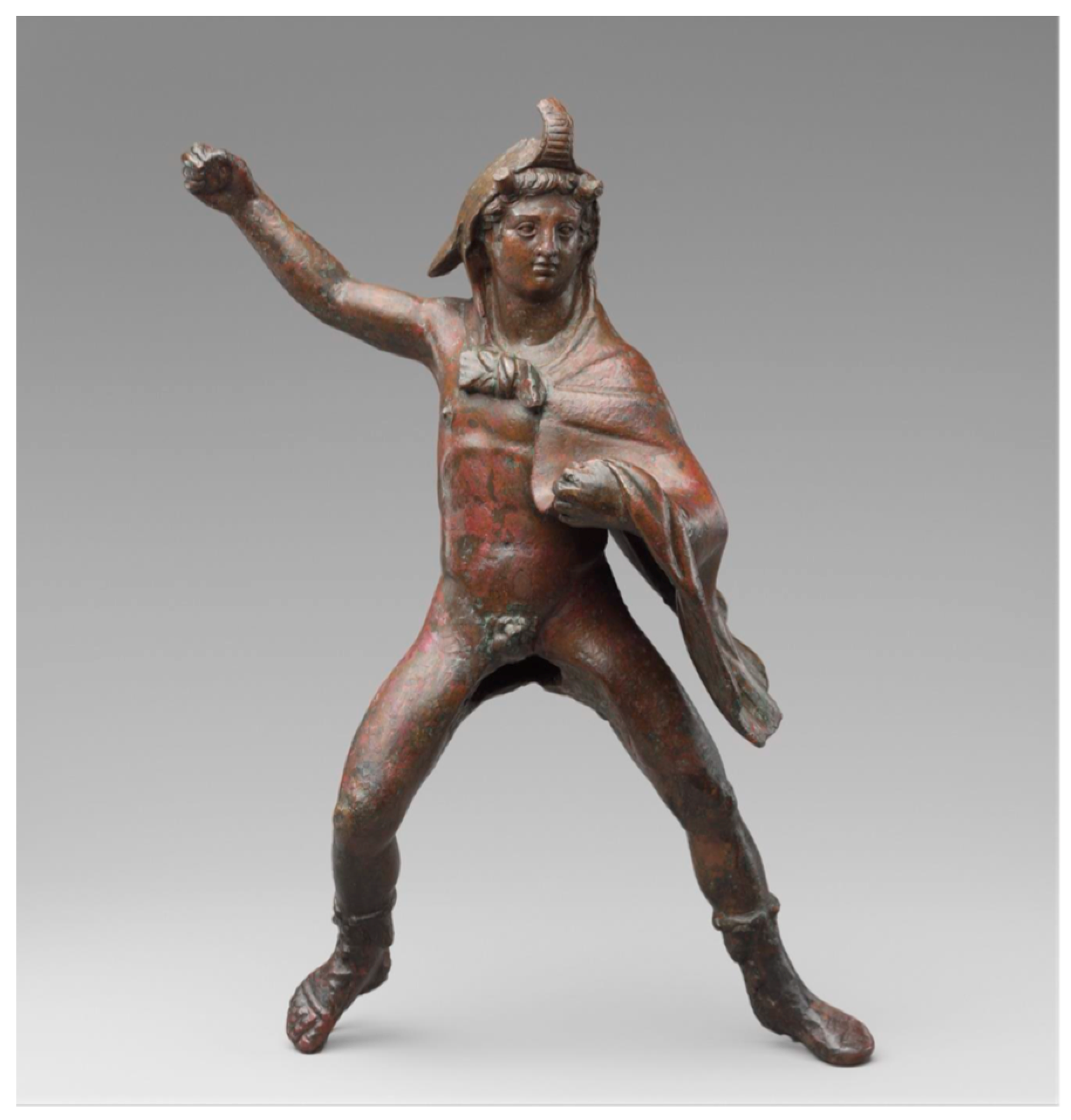

| 122 | MMA acc. no. 55.11.11 (bronze statuette, Arthribis [?], ca. 3rd century bce); Scullard (1974, p. 144 and pl. 16g); Kyrieleis (1975, p. 166, no. B2, pl. 10, figs. 1–3); Smith (1988, p. 153, app. 8, no. 4, pl. 70, fig. 2); Cheshire (2009, pp. 11–63); Schneider (2009, p. 329); Bianchi (2010); Picón and Hemingway (2016, p. 111, no. 12). The figurine has been identified variously as Alexander the Great, Ptolemy II and III, and Demetrius of Bactria; only the first and last kings are otherwise known to have been portrayed with the exuvia elephantis (the Egyptian origin of acquisition make the latter unlikely). |

| 123 | Supra p. 7, n. 39. |

| 124 | BM reg. no. 1866,0804.1 (dark blue jasper, unknown provenance, ca. 3rd–2nd century bce); Walters (1926, no. 1188); cf. Plantzos (2002) (for a silver intaglio). |

| 125 | |

| 126 | Acc. to Bigwood (1993), Arist. Hist. Anim. describes the African elephant, and only since Alexander’s campaign did authors point out that the Indian elephant was larger than the African (which implies they knew about the size of the latter); this observation also means that, even though earlier authors such as Ctesias were aware that elephants were found both in Asia and Africa, they did not realize their differences. Furthermore, if Ptolemy IV indeed left a memoir of his campaign against Antiochus III (the so-called Fourth Syrian War, ending with the Battle of Raphia), he would certainly indicate their differences in physical appearance (not in the least their size). |

| 127 | |

| 128 | MFA inv. no. 04.727 (silver tetradrachm, Side (?), ca. 326–318 bce); Brett (1955, no. 679); Bieber (1965, p. 185, pl. 6, figs. 10–11); Fredricksmeyer (1991, p. 204); Hsing (2005, p. 111, fig. 9); Dahmen (2007, pp. 108–9, pl. 1, fig. 1 and 3); Lorber (2012, fig. 3). |

| 129 | Diod. Bibl. 2.39.1; Arr. Ind. 5.13 and 8.4–6; Puskás (1990, pp. 42–46); Sacks (1990, p. 67); Arora (1992, esp. pp. 316, 319); Bosworth (1996, pp. 121–22); Hsing (2005, pp. 108–10). |

| 130 | Dahlquist (1977); Zambrini (1982, 1985); Karttunen (1997, pp. 210–19); Puskás (1990, pp. 41–47); Hsing (2005, esp. pp. 118–23); Muntz (2012, pp. 32–34). |

| 131 | For the origin of Indra, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 249–83); Basham (1989, pp. 9–13); Hackstein (2003, p. 134); Klostermaier (2007, esp. pp. 103–4). |

| 132 | For the identification of Indra with Heracles or Zeus, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 280–81); Dahlquist (1977, esp. pp. 164–74); Puskás (1990, pp. 43–44); Karttunen (1997, pp. 89–90). |

| 133 | For the origin of Shiva, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 23–210); Long (1971, pp. 185–88); Basham (1989, pp. 4, 44 and 82); Linrothe (1999, pp. 181–83); Klostermaier (2007, esp. pp. 109–10, 218–31). |

| 134 | For the meaning of Shiva and Rudra, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 109–57); Long (1971); Basham (1989, pp. 15–16); Linrothe (1999, pp. 215–16); Klostermaier (2007, esp. pp. 219–22). |

| 135 | For the identification of Shiva with Heracles or Dionysus, see: Diod. Bibl. 2.38; Strab. Geogr. 15.1.6–9; Arr. Ind. 1, 5, 7 and 9; Brown (1955, pp. 27–28); Long (1971); Dahlquist (1977, esp. pp. 278–89); Danielou (1979); O’Flaherty (1980); Puskás (1990, p. 46); Arora (1992, p. 319); Bosworth (1996, pp. 121, 123). |

| 136 | Satyr. ap. Theophil. 2.7 = FGrH 631 F 2; Nock (1928, pp. 21–30); van Oppen de Ruiter (2013, p. 81, n. 4). |

| 137 | For the origins of Krishna, see: Bhattacharji (1970, pp. 301–16); Basham (1989, pp. 73, 90–93); Klostermaier (2007, pp. 60, 63, 77–80, 111 and 200–04); F. Stewart (2010, p. 113). |

| 138 | For the identification of Krishna with Heracles, see: Strab. Geogr. 15.1.6–9; Arr. Ind. 5 and 8–9; Puskás (1990, pp. 42–45); Arora (1992, p. 319); Karttunen (1997, p. 89). |

| 139 | Bosworth (1988, pp. 71–74); Fredricksmeyer (1991, pp. 199–201); Anson (2003); Lorber (2012, p. 25); Bosch-Puche (2013, p. 151); Howe (2013); Collins (2014). |

| 140 | |

| 141 | For the intricate matter of Alexander’s “sonship”, e.g., see: Diod. Bibl. 17.49–51; Strab. Geogr. 17.1.43; Curt. Ruf. 4.7.23–25; Plut. Alex. 27; Arr. Anab. 3.4.5; cf. lit. cit. supra n. 139. |

| 142 | |

| 143 | E.g., Hom. Il. 2.375. |

| 144 | WAM acc. no. 54.1075 (bronze statuette, Alexandria [?], ca. 1st–2nd century bce); A. Stewart (1993, pp. 243–52); Parlasca (2004); Reinsberg (2005, pp. 226–29). |

| 145 | Arr. Anab. 3.5 (I owe this suggestion to Robert S. Bianchi). |

| 146 | Plut. Alex. 2; Arr. Anab. 3.3.2; ps.-Callisth. 1.1–12; Henrichs (1978, esp. p. 143); Bosworth (1988, pp. 19, 282–84); Ogden (1999, pp. 27–29); King (2013, pp. 88–93); van Oppen de Ruiter (2019, pp. 92–93). |

| 147 | For instance, V&A inv. no. 439–1883 (tapestry, Brussels, ca. 1507–1510); MNAC inv. no. 214.101–000 (tapestry, Brussels, ca. 1520–1548); Campbell (2004, 2007, pp. 149–55). |

| 148 | MMA acc. no. 41.167.2 (tapestry, 3.66 cm × 3.25 m, South Netherlandish, ca. 1500–1530); Cavallo (1993, pp. 463–78, no. 33a). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Oppen de Ruiter, B.F. Monsters of Military Might: Elephants in Hellenistic History and Art. Arts 2019, 8, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040160

van Oppen de Ruiter BF. Monsters of Military Might: Elephants in Hellenistic History and Art. Arts. 2019; 8(4):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040160

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Oppen de Ruiter, Branko F. 2019. "Monsters of Military Might: Elephants in Hellenistic History and Art" Arts 8, no. 4: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040160

APA Stylevan Oppen de Ruiter, B. F. (2019). Monsters of Military Might: Elephants in Hellenistic History and Art. Arts, 8(4), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040160