Abstract

The Israeli art field has been negotiating with the definition of Israeli-ness since its beginnings and more even today, as “transnationalism” has become not only a lived daily experience among migrants or an ideological approach toward identity but also a challenge to the Zionist-Hebrew identity that is imposed on “repatriated” Jews. Young artists who reached Israel from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) as children in the 1990s not only retained their mother tongue but also developed a hyphenated first-generation immigrant identity and a transnational state of mind that have found artistic expression in projects and exhibitions in recent years, such as Odessa–Tel Aviv (2017), Dreamland Never Found (2017), Pravda (2018), and others. Nicolas Bourriaud’s botanical metaphor of the radicant, which insinuates successive or even “simultaneous en-rooting”, seems to be close to the 1.5-generation experience. Following the transnational perspective and the intersectional approach (the “inter” being of ethnicity, gender, and class), the article examines, among others, photographic works of three women artists: Angelika Sher (born 1969 in Vilnius, Lithuania), Vera Vladimirsky (born 1984 in Kharkiv, Ukraine), and Sarah Kaminker (born 1987 in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine). All three reached Israel in the 1990s, attended Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, and currently live and work in Tel Aviv or (in Kaminker’s case) Haifa. The Zionist-oriented Israeli-ness of the Israeli art field is questioned in their works. Regardless of the different and peculiar themes and approaches that characterize each of these artists, their oeuvres touch on the senses of radicantity, strangeness, and displacement and show that, in the globalization discourse and routine transnational moving around, anonymous, generic, or hybrid likenesses become characteristics of what is called “home,” “national identity,” or “promised land.” Therefore, it seems that under the influence of this young generation, the local field of art is moving toward a re-framing of its Israeli national identity.

1. Introduction

Israeli art has been negotiating the definition of Israeli-ness since its inception. These negotiations have become even more urgent today, as “transnationalism” has become not only a lived daily experience among migrants or an ideological approach toward identity but also a challenge to the Zionist-Hebrew identity, as an homogeneous, single-cultural one, in which multiplicity is undesirable—an identity imposed on “repatriated” Jews as the “normative acculturating option.” In recent years, amid global processes of migration and the rise of the transnational discourse, researchers and curators are increasingly interested in artistic manifestations that represent diversity of voices and reveal complex relations among national, cultural, gender, and class identities. Recent exhibitions in important museums, such as Odessa-Tel Aviv at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv (2017), Pravda at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (2018), and the Dreamland Never Found project at the Jerusalem Biennale (2017), along with studies such as those of Dekel (2016a, 2016b, 2018), Shapira (2017), and Guilat (2017, 2019a, 2019b), deal with young artists who reached Israel in the 1990s from the former Soviet Union as children or teenagers and developed a hyphenated “1.5-generation” immigrant identity. Like all 1.5-generation immigrants, they neither experienced the full process of uprooting as would first-generation immigrants, nor were they born in the destination country. Their immigrant experience, largely discussed in the fields of education, labor, and social behavior (Leopold and Shavit 2013; Mesh 2002; Koren and Eisikovitz 2011) has not generated a “new homogenous Israeli post-Soviet style” in the art field. Instead, it has opened that field to different and diverse voices mainly labeled as a transnational approach within the national art scene. It seems that in order to shed light not only on the way these artists elaborate transnational identity issues but also on the range of this 1.5-generation immigration’s experiences and its possible influence on generational interactions, we need to expand our points of view. Nicolas Bourriaud’s (2010) botanical metaphor of the radicant, which insinuates “a multitude of simultaneous or successive en-rootings” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 22), seems to lend this floating status of the “1.5 generation” an aesthetic dimension that accords with the radicant art concept that he coined, referring to modes of expression and communication that transcend the discourse of authenticity of the modern mono-cultured subject and connect multicultural landscapes and passageways that characterized global times (Bourriaud 2010). According to Bourriaud, artists are now starting from a globalized state of culture and responding to a new globalized perception of their self and the art field. Basing myself on previous research, and following Bourriaud’s view of the transnational identity in globalizing times and the intersectional approach (with its nexus of ethnicity, gender, and class), below I examine photographic works of three women artists: Angelika Sher (born 1969 in Vilnius, Lithuania), Vera Vladimirsky (born 1984 in Kharkiv, Ukraine), and Sarah Kaminker (born 1987 in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine). All three reached Israel in the 1990s, attended Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, and currently live and work in Tel Aviv or (in Kaminker’s case) Haifa. Situated in a liminal or, perhaps, a polar position within the 1.5-generation group, Angelika Sher, the oldest of the three, interacts extensively with young artists, including by working on collective projects with them. Through their art, Sher, Vladimirsky, and Kaminker stand at the intersection of gender, migration, and biography and, by means of all of these, express a transnational identity that replaces attempts to assimilate, “fit in,” and be Israeli, with a multi-hyphenated fluid structure. Their transnationalism may be perceived as a postmodern phenomenon related to the precarity and uncertainty that typify the early twenty-first century. Additionally, and more importantly, however, one may perceive it as a powerful contestation and response to both the modern national state and its desire to forge homogenous identities (especially in its Israeli melting-pot version) and the postmodern standardizing process of globalization that coincides with “inclusive” global approaches that are sometimes regulated by nostalgia, ethno-tourism, or cultural-ghetto-seclusion.

The relationship of time and place that Bourriaud proposed for the nomad-artist may be considered, in the case of the Former Soviet Union (FSU) women artists who predicate their work on photography, an articulation of the past into the present, a mobile deconstructed and reconstructed identity positioned at a new emplacement in front of the camera. Photography offers a wide range of possibilities with which one may challenge rigid identities and their representations. Its practice involves negotiations between documentary and staging options, between the real and the imaginary, and between the past and memory and current realities. Aim Deuelle Luski (2012, p. 7) defines photography as “transcendent to the time but not exterior to it, on the contrary, staying on the liminal of all the times, in a heterotopic space that the camera grasps as a fissure or crack on the margins of the culture.” Generalizing, one can say that photography is neither about the particular (even if the particular appears in the frame) nor about the generic, but about using both in order to transcend them. This “using”-based ontology has a potential radicant dimension that may, intentionally or not, be amplified in migrant situations. The digital era challenges this grammar of internal paradox even more but has not essentially changed it because its transformative qualities make it inherent. The photographic image, Barthes (1978) argues, is a message without a code, a continuous message from the denotative perspective. At the same time, it is a connotative message, not at the level of the message itself but at the level of its production and reception; thus it tends to be re-coded when set atop different platforms. The photographic image is an object that is selected, structured, built, and produced according to paradigms—aesthetic, cultural, or ideological—but is concurrently a mobile one continually transported through times and places.

By referring to contemporary photography works by FSU artists and subjecting them to comparative examination—among them and between them and other representative artists of the 1.5 generation, as I present in the introductory section of this article, I would like to expand the thematic mapping of the FSU 1.5 generation. The examination of photographic practices and oeuvres may abet a more complex articulation of the identity issue that immigration to Israel from the FSU raises and may also illuminate the dynamic of the local (national) field of art from a transnational (global) perspective.

2. Transnationalism, Intersectionality, Radicant Art

The three concepts in this subtitle may be understood as a triangular visor that I will use in this study. By mounting three lenses with which I will observe three case studies, I will propose a number of reflections that may allow the sum of the studies to transcend all three as separate issues. From the methodological standpoint, this triangle will abet a multi-interdisciplinary approach that, in turn, may be applied more broadly to future research on FSU artists in Israel and in different diasporas—a topic that deserves much more development than this article can provide.

The term “transnationalism” denotes a social phenomenon and a theoretical perspective that gained strength in the late 1980s and has evolved since then, investigating changes in nation-states and national self-definition in response to massive waves of migration. Transnationalism has implications for the way we conceptualize migration as a process of identity construction that occurs simultaneously in many places around the globe and involves people who are physically or virtually linked to more than one geo-national venue through family connections, economics, and national and cultural praxis. It opens earlier paradigms of discussion, such as assimilation versus dissimilation, to a range of variants and new critical understandings that challenge the national ones. The transnational subject goes about life in constant intercultural negotiation consisting of translation, de-codification, and recodification of cultural modalities.

“Transnationalism” as a lexeme was first invoked in nineteenth-century political economy in reference to private corporations that maintained large-scale financial operations and an administrative presence in several countries. Today, it is identified with the practices of migrants and networks of social-relation and filial communities that cross-national borders. As Moctezuma Longoria argues in his analysis of the topic, “There is a tendency to relate not too rigorously to globalization and transnationalism, exaggerating the idea of the disappearance of borders, nations, and states, underscoring the perspectives of insertion of the migrants in the recipient societies and losing the richness that the simultaneity of transnational practices implies and the transformation of the states involved in international migration” (Moctezuma Longoria 2008, p. 38). This situation—a complex one in practice as well as in meta-theory—complicates the ways in which room may be made for singular manifestations and multifaceted experiences of migrants and immigrants, as Dekel (2016b) shows in her studies about transnationality and gender. Israel is an especially complex case because its selective immigration policy gives priority to jus sanguinis (the right of blood), a legal principle of nationhood.1 In accordance with this principle, Jews who immigrate to Israel, known as ‘olim’ (“ascenders” or repatriates), are immediately entitled to citizenship—an entitlement hardly available to non-Jewish immigrants or persons of “dubious” origin. Therefore, in Israel today, “transnationalism” is not only a lived daily experience for migrants or an ideological approach toward identity but also a challenge to the monocultural Zionist-Hebrew identity that is imposed on “repatriated” Jews. Young artists who reached Israel from the FSU as children in the 1990s, as well as those who came from Ethiopia in those years, have stayed in touch with family and friends from their birth countries, not only retaining their mother tongue but also developing a first-generation or 1.5-generation immigrant identity that has found artistic expression in projects and exhibitions in recent years. The shift from the typical alienation and disengagement of the liminal stage between immigration and transnational self-awareness evidently takes place along different paths among immigrants from different countries and of different genders and classes, and can be understood better through intersectionality theory (Crenshaw 1991).

To invoke “intersectionality” as a theory, one must analyze the way overlapping categories of identity impact individuals and institutions, and take these relationships into account when working to promote social and political equity. Kimberle Crenshaw, a law professor at California University, coined the term in 1989 to challenge the white-middle-class feminism that, at the time, overlooked the difference between the forms of oppression experienced by white middle-class women and those experienced by black or poor women or those with disabilities. In her pivotal paper for the University of Chicago Legal Forum, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, Crenshaw wrote:

I suggest further that this focus on otherwise-privileged group members creates a distorted analysis of racism and sexism because the operative conceptions of race and sex become grounded in experiences that actually represent only a subset of much more complex phenomenon.(Crenshaw 2017)

Three interwoven aspects of the theory gained special focus: structural, political, and representational intersectionality. The first deals with how non-white women experience domestic violence. Political intersectionality proposes that laws and policies that ignore the difference between non-white women and white women in the visibility of violence have actually amplified inequality. Finally, representational intersectionality deals with how cultural portrayals of non-white women perpetuate stereotypes and obscure these women’s own authentic lived experiences. In the context of this article, representational intersectionality in its recent development toward migrant women in the globalizing world economy seems to be an adequate tool of analysis. The term “transnational intersectionality,” coined by Shelly Grabe (Grabe and Else-Quest 2012) attained a more comprehensive conceptualization of intersectionality by giving importance to the intersections among gender, ethnicity, sexuality, economic exploitation, and other social hierarchies, in a universal dynamic of global capitalism that is characterized by multiple migrations, displacement, and precarity. As Ranjoo S. Herr points out, Grabe also pays attention to “complex and intersecting oppressions and multiple forms of resistance” (Herr 2014). It is not only about oppression; it is also about contestation and new models of living amid constant uprooting. Originally developed as a Third World proposition, “transnational intersectionality” converges with the time at which Bourriaud wrote about nomadic art as “radicant.”

The development of the neoliberal market, together with the global communication and information networks, has had significant consequences for both our daily lives as for art. Seeking to understand the effect of globalization on today’s art, Nicolas Bourriaud proposes the radicant concept. As explained above, radicant is a botanical term for organisms whose roots form new roots as they grow. In art, radicant assumes the form of a path or a trajectory; the radicant subject carries their roots along with them on their travels and questions them. The result is that “[t]o be radicant means setting one’s roots in motion, staging them in heterogeneous contexts and formats, denying them the power to completely define one’s identity, translating ideas, transcoding images, transplanting behaviours, exchanging rather than imposing” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 22). That is, instead of expressing the original roots/sources/tradition from which they come, artists and their works express the journey, the passage, that they make between their cultural roots and the different contexts that they cross. In its realization, the radicant aesthetic has several characteristics. The one that I am interested in emphasizing is the focus in spacetime dimensions and, more specifically, “the crossing of the respective properties of space and time, which transforms this last in a territory” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 89), possibly a territory in a state of flight.

There lies the nexus between a transnational status and transnational self-awareness. The overlapping of the three concepts seems to be not only contingent but also powerful as a tool of analysis in the case of 1.5-generation immigrants in global migrations around the world—especially migrant artists, as has been applied in the study of Cuban diaspora artists (O’Really Herrera 2011), and Canadian artists in Berlin (Phillips 2014). Moreover, and especially in the context of the present study, it is applicable to women artists who reached Israel as part of a mass immigration movement known in Israel as “the 1990s Aliya.” Their art developed in two fields of art: one global (transnational) and the other local (national). In the latter, questions of Israeli-ness are still relevant, as are those of gender, ethnic, and class inequalities.

3. The 1990s Aliya and the Israeli Field of Art

Perestroika in the USSR triggered a process of renewal and reconstruction of identities, including the revival of religious traditions. Thus the masses of immigrants who reached Israel in the 1990s underwent this process between Soviet and post-Soviet values (Shternshis 2006). In the 1990s, approximately a million FSU immigrants reached Israel, which had a population of 4.5 million at the time. The impact of this mutual encounter was very significant: the “Russian ‘aliya’”2 transformed both Israel (Lerner 2012) and the FSU immigrants in respect of their national identification. Such was the case even though many immigrants chose Israel because the collapse of the Soviet regime left Zionism as only an instrumental economic way to escape (Philippov 2010, p. 3). Perhaps due to their massive presence and its resonance in the public sphere, the FSU immigrants and, in particular, the women among them have been subjected to a wide array of derogatory stereotypes, intercultural clashes, and competitive class struggles that became common themes in the artistic corpus of the 1.5 generation at large (Lomsky-Feder and Rapoport 2010; Rotenberg 2018). To construct a context that will help us compare the radicant photographic strategies that have characterized Sher’s, Vladimirsky’s, and Kaminker’s works, one needs a brief description of the main themes discussed in the current Israeli art field in reference to 1.5-generation FSU women visual artists as a whole. By mapping their solo and group exhibitions, we extract several main themes: the conditions of precarity that typify the lives of the 1990s aliya, gender clashes, Jewish religious identity, and the stereotype of the “Russian prostitute.”

Precarity and class, gender and ethnic clashes: This topic became associated with 1.5-generation FSU artists as a resistance and contestation to the Israeli pictorial canon and cultural hierarchies since the advent of New Barbizon Groupe, a collective of women painters comprising five FSU-born Israeli artists (Zoya Cherkassky, Natalia Zourabova, Anna Lukashevsky, Asia Lukin, and Olga Kundina). The group calls itself the New Barbizon in homage to the nineteenth-century French Realist painters who emerged from their studios and began to paint nature from observation (Guilat 2017). The new group’s paintings, in turn, reflect the precarious “back yard” of Israeli society. All five painters attended art schools and academies in the FSU, Israel, and Europe, and took their training into the urban space (Guilat 2017; Shapira 2017). There, as what Bourriaud would call nomad-artists, they developed a pictorial language that is suited to the conditions of outdoor painting as a travel- and socially engaged practice under the tough conditions of the Israeli street, especially for women immigrants. “An immigrant’s ethnic identity,” Lilach Lev Ari points out, “is an inclusive conceptual matrix that the host society constructs through daily interaction that may assign the immigrant to a certain social group within the target society and induce changes in his/her own self-perception as an immigrant” (Lev-Ari 2013, p. 204). For this reason, joining the New Barbizon Group is a declaration, so to speak, of self-presentation in the Israeli field of art that includes style, practices, and topics that, although originating in the so-called “Russian artistic school,” act in exchange with the local Israeli environment. The result is a translation of sorts into a new context that, in turn, morphs into a successive, simultaneous ongoing process or “alternating acts of en-rooting” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 46).

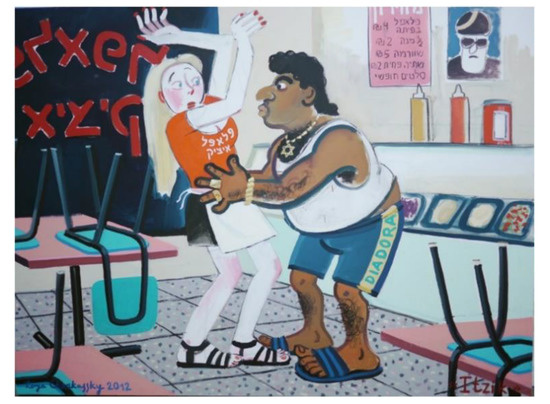

Since 2012, Zoya Cherkassky’s (b. 1976 in Kiev) solo paintings (i.e., those outside the context of the New Barbizon group) have addressed her personal experiences as well as the collective experience of the million-strong immigrant influx to Israel in the 1990s. In 2017–2018, her full project, Aliya 91 (fifty paintings and fifty works on paper) was exhibited at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and was titled Pravda. Aliya 91 is a humorous pictorial essay that transforms the mythical “repatriation” embodied by the Hebrew word ‘aliya’ into a simple act of relocation in an era of transnationality. The project underscores the contradictions that characterize intercultural encounters [Guilat 2019a]. Some of its works depict embarrassing Russian-Israeli culture clashes that have earned notoriety and critical contestation on social media. Cherkassky has been accused of racism toward Mizrahim (Jews from Muslim countries), whom she portrays as the stereotypical “Itzik” (2012), “a primitive abusive macho type” (Figure 1). In fact, through the ironic cartoonish figures and the satirical situations that she portrays in her works, Cherkassky tackles taboos associated with the ethnic conflicts in Israeli society and home culture by invoking the strategy of reversing the stereotypical image of the “others.” The image, however, is freighted with a social and historical context that sets the boundaries of possible interpretation (Ben Dayan 2012). Following intersectional theory, one may assume that the visuality of the gender and ethnic conflicts in Cherkassky’s pictures represents her experience (or the experiences of other FSU women) as a “Russian woman” but no less the image of Mizrahi male and the FSU women in the hegemonic European Ashkenazi vision. Both stereotypes of marginalized people in Israel society struggle under the eyes of the Sephardi rabbinic authority that appears at the side of the picture. While they share a precarity that spans class, race, and gender, they face the threat of male aggression through the empowering medium of the religious issue (see also the Star of David necklace).

Figure 1.

Zoya Cherkassky, “Itzik,” 2012, oil on canvas, 200 cm × 150 cm, private collection. Retrieved from http://rg.co.il/artist/zoya-cherkassky/works/. Used by permission of Rosenfeld Gallery, Tel Aviv.

Religious identity: Another trenchant theme that 1.5-generation FSU artists (again, especially the women among them) engage with is the Israeli-Jewish religious affiliation. One-third of FSU immigrants are not Jewish according to Jewish religious law, despite having immigrated to Israel under the Law of Return, which guarantees all Jews and close relatives the right to live in Israel and receive its citizenship. Orthodox interpretations of Jewish religious law, which hold sway in Israel, recognize only matrilineal descent and Orthodox conversion as indicators of Jewishness. As a result, many immigrants in Israel live in a civil limbo because, unlike most Western nation-states, which separate national issues from religious institutions, Israel defines itself as a Jewish state and attributes more than a religious identity to Jewishness—adding citizenship, nationality, ethnicity, and socio-cultural capital. Thus, argues Tal Dekel (2016c, p. 12) in her article on this theme: “As so many of the newcomers, whose Judaism [Jewishness] was called into question or rejected upon their arrival in Israel, confronted new and startling difficulties relating to their Jewish identities, [young FSU women] artists among them turned to express this burning theme extensively in their work.”

The Russian prostitute: Referring to the work of Sasha Kurbatov (b. 1987 in Ukraine) and Vanene Borian (b. 1984 in Armenia) in the public space (Kurbatov and Borian 2016), Masha Aberbuch claims that all their “provocative” projects express “monumental dramatism, a tendency to great gestures, self-sacrifice, fatalism, honesty and blatant honesty—they are the foundations of Borian and Kurbatov’s art” (Aberbuch 2016). In 2016, the two placed a sculpture in the form of a three-foot female water organ on Rothschild Avenue in central Tel Aviv. The statue was made of women’s prostitution “business cards” gathered from the streets, to which a fifty-foot-long carpet led. It is difficult to estimate the number of cards that they needed to build the statue with the carpet that leads to it. The experience of collecting them at night and on weekends was a work in itself, one that confronted attitudes and potentially delivered them to another place of contestation.

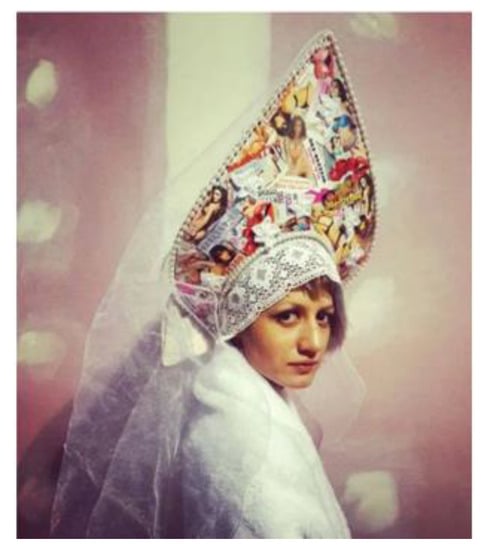

Borian and Kurbatov focused their collaborative work on acting out the “Russian prostitute” stereotype that Russophone women in Israel face. The raw material that they chose is the mass of cards that circulate in the streets. In another work (Figure 2), Kurbatov is photographed in the image of a Ukrainian bride (2015) who, putting on a shameless look, is dressed in white and wears a traditional Russian headdress called a kokoshnik, which became popular as a tiara style in Western Europe in the late nineteenth century. A closer look reveals that it is a collage of prostitution cards framed in white pearls and white lace. The kokoshnik not only evokes the connection between marriage as a sexual contract and woman’s place in the patriarchal order but also illustrates the “Israeli view,” embodied in the expectation of Russian-speaking women to provide sex services—be they imported brides, tourists, or immigrants under the Law of Return. Lomsky-Feder and Rapport conclude: “The body of the ‘Russian’ women immigrant serves as a moral marker of the boundaries of the Israeli-Jewish collective by labeling it as impure and outbreak, and thus a site of exclusion and alienation” (Lomsky-Feder and Rapoport 2010, p. 79). By extension, arguably, Kurbatov and Borian undermine not only the Israeli-Jewish-Zionist self-image but also they challenge boundaries of the field of art in Israel by referring to it.

Figure 2.

Sasha Korbatov, “Kokoshnik,” 2015, a traditional Russian headdress collage of prostitution cards. Photographed by Vanene Borian. Retrieved https://www.haaretz.co.il/magazine/the-edge/.premium-1.2883877. Courtesy of the artist.

Due to these major themes, radicant aspects of the women-immigrant experience, such as the perception of Home, Homeplace, and Family as a surrogate “motherland,” and transnationality as a cultural option that combines past and present and preserves links with the post-Soviet diaspora as well with West and East European culture, are less investigated. Artistic activism in the public sphere or its representation, and its inherent conflicts as described above, resonate more loudly in research and the media than did the activities of artists who “just” rephrased their radicant identity and re-emplaced it in a new cultural context. Sometimes it was interpreted or was seen as part of some revival of the “non-Jewish Russian” culture, a “back-to-the-roots” endeavor powered by breezes of “multicultural inclusivity” that, as a highly fashionable trend in this globalized era, made inroads into Israeli art.

Focusing on this point from another perspective, I propose to see this approach as an opening, transitioning, performative flow that articulates migrant and female experiences “like an emulsion … producing an alloy that combines, without dissolving them” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 34) through a radicant aesthetics that, like radicant plants, exists and proliferates without having “to drill down into the ground” (ibid., p. 43), making “fewer points of contact with the soil instead of enduring them” (ibid.).

4. Transnationalism, Intersectionality, and Radicant Aesthetics through the Lenses of Israeli Women Photographers from the Former Soviet Union

The operation that transforms every artist, every author, into a translator of him-or-herself implies accepting the idea that no speech bears the seal of any sort of “authenticity”: we are entering the era of universal subtitling, of generalized dubbing. An era that valorizes the links that text and images establish, the paths that artists? forge in a multicultural landscape, the passageways they lay out connect modes of expression and communication.(Bourriaud 2010, p. 35)

Bourriaud places artists in the transnational era in the role of polyglot translator. The multicultural landscapes presented/translated/mediated in their works become vehicles of sorts for simultaneous expression of spaces and times, dissolving the linearity and a positivist perspective that characterized modern times and national societies. The works presented here, selected from the artistic corpus of Angelika Sher, Vera Vladimirsky, and Sarah Kaminker refer to one common theme and propose to exemplify how Home and Family can be under universal subtitling for FSU women artists in Israel. How the family nucleus and its physical environment, through time and places, its dis-integration and its possible re-integration, would reflect an intersectional representation of a radicant status. The connection between medium and content and the interpretative nexus of denotation and connotation in photographic research forces us to explore a multi-hyphenated fluid structure of transnational identities based on common but, at the same time, different biographical migration experiences and gender intersections.

Angelika Sher: The Odessa exhibition (2017) and the Funeral Performance of the Novy God celebration (December 2017) (Sova 2017), both with the participation of Angelika Sher and Xenia Sova—another representative of the 1.5 generation, who calls herself a “Mediterranean Russian” (in Hebrew: Rusia Yam Tikhonit) (Brook-Blom 2017), combine humor with meticulous examination of the meaning of transnationalism through the arts in reference to the ‘aliya of the 1990s (Figure 3). Sher, Sova, and Yuri Leiderman (who lives in Berlin) met at the Odessa-Tel Aviv group exhibition. Despite the geographical distance and the age gap among them, they re-created Odessa as an iconic image that replaces a real motherland, a transnational place-out-of- place that comprises a mixture of symbols, myths and allegories, language and humor, literature and theater, food, colors, fabrics, and aromas. The city thus created may be dedicated to anything one wishes as a portable identity in a global world. Sher’s “Socks and Sandals” and “Magical Tablecloth [Samobranka]” allow us to return to her entire oeuvre and reexamine what was defined as an abundance of “strangeness, foreignness, distance and alienation evident in every detail, albeit implicitly and indirectly” (Shkolnik-Brenner 2009).

Figure 3.

(a) Angelika Sher and Xenia Sova, Funeral Performance of the Novy God Celebration, 2017, Documental materials and still photo from YOUTUBE. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qs0Y1JtF_L4&t=119s&fbclid=IwAR3anKA7AJz5F4dUio0P8Le6hC5xCwblmrKRpeYWVzHFuwT723eDsZToMYw. Courtesy of the artist. (b) Angelika Sher and Xenia Sova, Funeral Performance of the Novy God Celebration, 2017, Invitation to the event, Facebook, retrieved from https://scontent.fsdv2-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t31.0-8/s960x960/26116236_1764038536954026_6983036200907152351_o.jpg?_nc_cat=105&_nc_ohc=mm180P-iBfoAQk3a7arO_-L_jovfQjABDlLfMFlRNHImm2jz4G3CxW5CA&_nc_ht=scontent.fsdv2-1.fna&oh=759b19d34b7788006416cb203c1c5b68&oe=5E81C9E0. Courtesy of the artist.

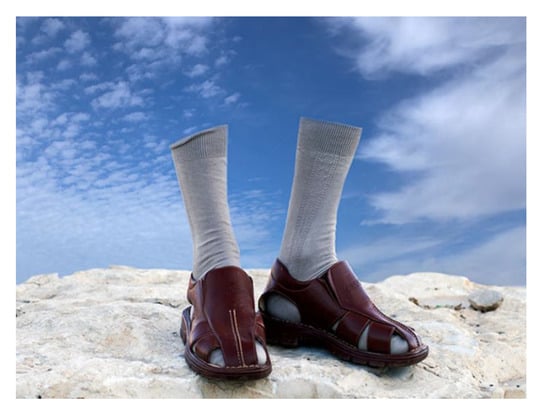

In Sher’s “Socks and Sandals” (Figure 4), created especially for the Odessa-Tel Aviv exhibition, socks in sandals stand alone in a cold, white, deserted landscape under a blue sky. “Amputated” legs present a disembodied metonymic image that emphasizes the strangeness of the background. Every detail seems to be a fragment of a different story. While the blue sky may be indicative of the Mediterranean sky, the light is different. It is true that wearing sandals with socks even in the heavy heat of the Israeli summer has been a cultural hallmark of former Soviet immigrants. Angelika Sher, however, does not produce a realist representation of this habitus; instead, she puts forward an ambivalent sign that indicates the possibility of a unique form of acclimation that is not fully adapted to the environment but preserves, survives, and marches … and, by doing so, portrays a fragmentary (radicant) existence, in which the past is a kind of “phantom.” The image that operates within and through the stereotypes bursts with self-humor. This approach recurs in “Russian Herring under a Fur Coat” [Shuba], first exhibited in Mayonnaise Snow (2015), in which the translation mode is adopted to inscribe the Soviet repertoire onto the Israeli one. Another work displays the top of St. Basil’s Cathedral (Figure 5), its vibrant colorful towers and dome “buried” in a desert of sand. The temple, one of the world’s most famous buildings—it dominates Red Square in Moscow, the very heart of Russia—is transplanted into the sands of Israel, forming an image drawn from the Middle Ages and Middle Eastern tales, again allegorizing an intercultural encounter as a milestone in an uncertain trajectory and at the same time as a distorted icon. The distortion of the symbolic icons can be interpreted as a result of the re-rooting in Bourriaud’s radicant theory, which, while facilitated by the conditions of the soil rooting, is but a temporal “multicultural landscape, the passageways” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 35) to other distortions that, in turn, problematize the essence of authenticity. Is this non-authentic and absurd image the “authentic” mode of the expression of a radicant status?

Figure 4.

Angelika Sher, “Socks and Sandals,” 2017, Photography. Retrieved from https://www.eretzmuseum.org.il/e/376/. Courtesy of the artist and Zemack Contemporary Art Gallery.

Figure 5.

Angelika Sher, “Untitled” (Saint Basil’s Cathedral in the Rishon Lezion dunes), 2015. Photography. Retrieved from https://zcagallery.com/artist/angelika-sher/. Courtesy of the artist and Zemack Contemporary Art Gallery.

When she accepted the post of curator of Odessa, Sher was considered a successful photographer due to her previous solo exhibitions: My Mother’s Fur Coat (Figure 6), Ramat Gan Museum, Israel (2007), 13 (Thirteen series) and Twilight Sleep, Tavi Dresdner Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel (2009), Inside My Life, Reartuno Gallery, Brescia, Italy; 13, Pobeda Gallery, Moscow; the Third Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, Fotografiya Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia, New York, and Milano.

Figure 6.

Angelika Sher, “Untitled,” 2007, exhibited in My Mother’s Fur Coat, Ramat Gan Museum, Israel. Retrieved from https://www.artsy.net/artist/angelika-sher. Courtesy of the artist and Zemack Contemporary Art Gallery.

Ten years before Odessa–Tel Aviv, the project culminating her studies at Bezalel Academy, Family Album, depicted immigrant families and created “time bubbles” of sorts that were interpreted as attempts to preserve the way of life of their origin countries. Yehudit Matzkel, curator of emerging artists in those years, curated Sher’s first solo exhibition, Mother’s Fur Coat, at the Ramat Gan Museum. This autobiographical exhibition marked Sher as an intriguing artist and gave her a thematic and stylistic foundation for her next projects. The raw material of Sher’s photographic work was, and continues to be, supplied by her family and immediate environment. Personal relations and domestic spaces are captured in moments full of longing, remoteness, and a beauty that can hurt.

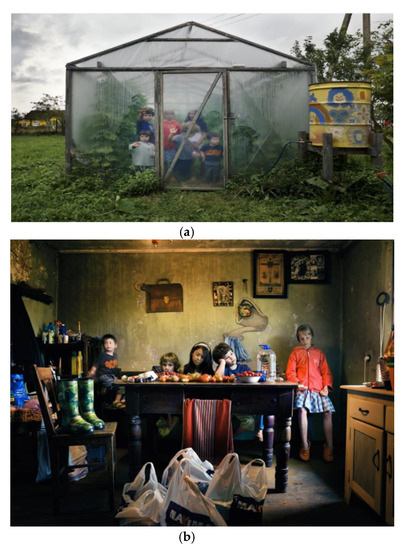

Sher invokes these images to explore ideas of foreignness, girl-ness, and woman’s identity, with special interest in adolescence, parenting, and family links amid wanderings and journeys of uprooting. In her Growing Down project, she looks at adolescents and their relationships with each other, space, and the body. 13 continues by focusing on motherhood and exploring the effect of placing the camera and its subject at greater distance (Figure 7a,b). Twilight Sleep strays from the nuclear family to investigate notions of cultural memory, destiny, and death. In his essay about Sher’s works, Yair Barak (2009) argues that the memento mori motif is central to the genre that Sher adopted in this series. “At the same time, there’s a sense that Sher is creating a whole different syntax—less specific, deceptive, dialectic. Birth and death are not dichotomous; they dwell together and echo each other.”

Figure 7.

(a) Angelika Sher, “Untitled” (Thirteen series), 2008–2009, retrieved from https://zcagallery.com/artist/angelika-sher/. Courtesy of the artist and Zemack Contemporary Art Gallery. (b) Angelika Sher, “Untitled” (Thirteen series), 2008–2009, retrieved from https://zcagallery.com/artist/angelika-sher/. Courtesy of the artist and Zemack Contemporary Art Gallery.

Throughout the series, Angelika Sher offers an image of family and children to which strangeness, alienation, and detachment are intrinsic. She often deals with childhood, adolescence, and the transition between them as a suspended time between times and cultural worlds. This transitional status and its transcultural implications are presented as an existential question that embraces all aspects of life. In these series, the repetitive themes that arise from the staging, the clothes, and material culture used portray a sense of transnationalism that has nothing to do with joy, healthy maturity, and childish delight, instead reminding us much more of a process of withering or mourning. At this time, in my opinion, Sher does not celebrate transnationality; she just lives it. Although the photographs are undoubtedly staged and every detail is significant, the thing they convey more than anything else is indifference. They are deeply connected to the “suspended time” and “the flying carpet” that Rosi Braidotti (2012) attributes to the “nomadic”3 state of mind—what Barak calls the memento mori. It is from the dualism of the meticulously arranged setting and the indifferent gaze that her oeuvre in the “aughts” decade acquires its intriguing power and its multiple significations.

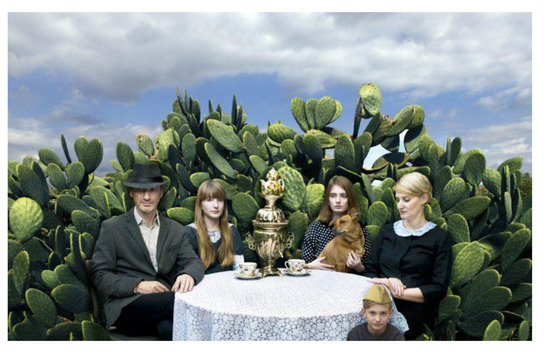

In recent years, the works of these young 1.5-generation artists have shifted to an explicitly transnational level that, while no less interesting, appears to have much more humor, irony, and self-reflection about what a transnational self is, including traditional Soviet “rites,” Christian iconography, and Russian folk tales. Through Sher’s trajectory one can see a radicant trajectory that evolved in the course of her career and reflected the exchange between her and the Israeli field of art and the mutual transformation, in terms of the artist’s attitude but no less in those of reception and interpretation. A case in point is Sher’s latest exhibition (May 2019) at the Beeri Gallery, A Green Oak Grows in the Bay (Figure 8), based on a sentence from the famous poem “Ruslan and Lyudmila,” written in 1817–1820 by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s greatest poet, and theatrically relocated to a pseudo-Israeli context. The exhibition featured a journey story in a remote, dramatic setting—a fantasy that is nevertheless rooted between Israel and Lithuania, creating a magical background of sorts for a complex narrative of immigration embedded in folk tales and folklore that translated each other. The space is designed as an archetypal paradise from which all human beings are exiled to a foreign and unknown land. Like other projects, this exhibition was autobiographical but it transformed personal experiences into fantasy, with collages consisting of objects scattered around the home of the artist or her family, and characters comprising her nuclear and distant family, her friends, and even their cat. As the curator, Sophie Barzon Makai, pointed out, “Multicultural wealth is on the walls. Eastern European, Middle Eastern, Israeli, Lithuanian, Russian, human rule. A proposal for a broad human identity of a new kind” (Barzon Makai 2019). From a “time-specific” perspective (Bourriaud 2010, p. 79), this work does more than span cultures and territories; it was created for a specific time in Israeli culture that corresponds to early ethno-nationalism and the late globalization.

Figure 8.

Angelika Sher, “Untitled,” exhibited in A Green Oak Grows in the Bay, 2019, Beeri Gallery, retrieved from http://www.gallerybeeri.co.il. Courtesy of the artist and Zemack Gallery.

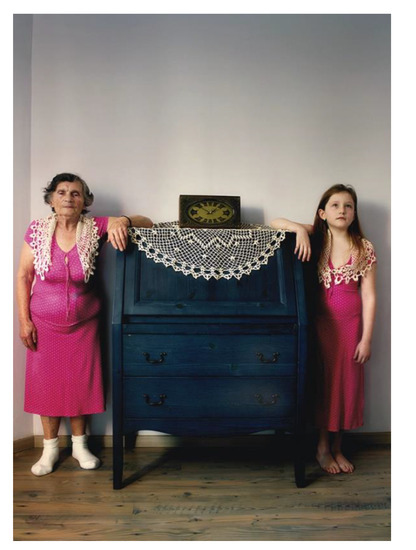

Using “representational intersectionality” as an analytic tool, I argue that Sher’s portrayals of people, particularly women, adolescents, and girls from the first, 1.5, and second generations of FSU immigration to Israel, use and manipulate stereotypes of “Russian families” in order to reverse them in a very sophisticated way. Through her camera, she appears to have assumed the role of translator—a fantastical repetitive stating, a mirror of sorts that reflects the image of the Russian cultural heritage in the eyes of the Israelis. All these strange situations, the heavy furniture, the foreign costumes, and the East European facial features configure a family affiliation that alludes to themes from Western art history through the personas of “Russian actors” and forces us to read these pictures with “subtitles,” as Bourriaud indicates. This strategy allows the “universal” viewer to confront the lived radicant experiences of generations of migrants in transnational times. In a similar way, intersections among gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and other social hierarchies in Israeli society appear in Sher’s works, their connotative significance emerging not via the individual picture but across complete series.

Vera Vladimirsky, a young artist born in the FSU, bases her conceptual approach on large research stages, manual procedures, and a sophisticated style. All these elements are crystallized into a unique transnational state of mind reflected in photos/wall papers that defy the rigid categorization of the “traditional” dichotomy: mutual acculturation versus national assimilation.

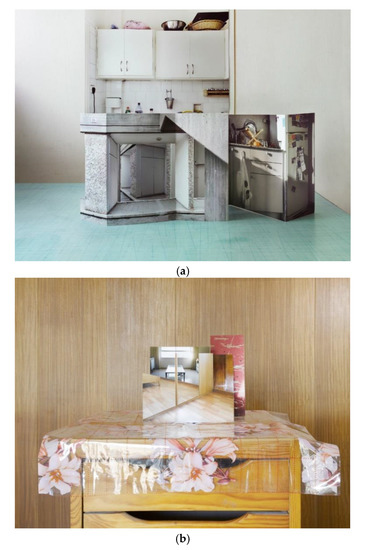

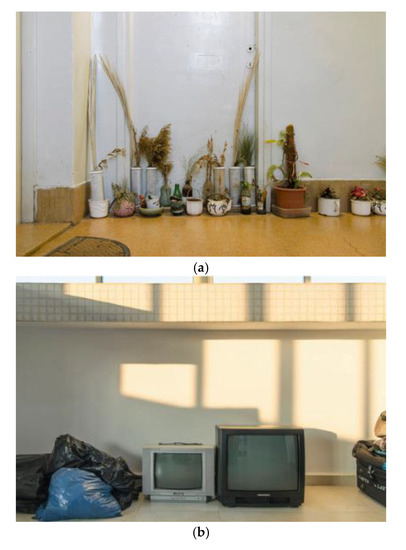

In her project The Last Apartment, Where Are You from Originally? (Figure 9a,b) first presented at the Bezalel Academy graduate exhibition in 2014, Vladimirsky asks, through a series of photos of home environments, Where are you originally from? This seemingly candid question triggers an intensive engagement with transnational migrations at times of constant “moving” and “relocation.”

“I am moving [again],” she writes. “When I was seven I came with my parents from Ukraine as part of the mass immigration in 1991. As we acclimatized, we moved house a lot. Since I turned eighteen, I’ve been moving on my own. I seem to have adopted the moving pattern. In this project, I returned to all the places that I had called ‘home.’ I photographed neighborhoods, buildings, and apartments in which other people currently live. I used the print photographs to compose three-dimensional assemblages of space, which I re-photographed in the apartment that I have been living in over the last year—my twenty-sixth apartment”.(Vladimirsky 2014b)

Figure 9.

(a) Vera Vladimirsky, “The Last Apartment, Where Are You From Originally?” 2014. Courtesy of the artist. (b) Vera Vladimirsky, “The Last Apartment, Where Are You From Originally?” 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

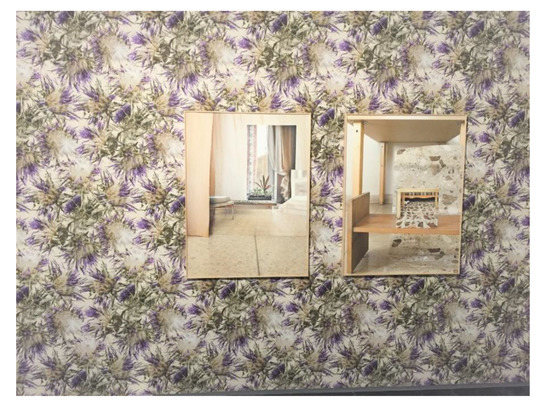

Vladimirsky’s description and the alienated and “outsider” quality of her assemblages deliver us to an unusual visual treatment of immigration, belonging, and longing in a national context. She focuses not on the efforts or difficulties that accompany the construction of a new national identity through the medium of places that are called home but on the sense of disconnection or just the realization that, in the discourse of globalization and the transnational routine of moving about, anonymous likeness and emptiness become characteristics of home (Guilat 2019b). At the group exhibition Dreamland Never Found (curated by Maria Veits at the 2017 Jerusalem Biennale), Vladimirsky unveiled a new project called “Paper Walls” (2015–2018) in which richly decorated wallpapers, typical of Soviet living rooms, become metonymic artifacts or attributes of transnationality. She paid special attention to the local flora that she used to “produce” her wallpapers (Figure 10). In a lengthy process, she created seamless, detailed and high-resolution floral patterns that she imprinted on her wallpaper sheets, merging childhood memories of richly decorated home interiors in the FSU with the common generic stuff of the local Israeli aesthetic. She observed her two cultures, the Ukrainian and the Israeli, focusing on their codes, ethos, and narratives. She sees “home” as a critical issue, through which she challenges not only the link between the mono-cultural identity discourse and the home but also the immigrant’s illusory and unfulfilled desire to feel at home and, even more, the medium of photography itself, by questioning representation and interpretation of social realities and manual and digital practices. As the paper walls evolved and were exhibited in group settings at Bat Yam Museum (2018) and the Bezalel Master’s Degree Exhibition (2019), they became more and more complex.

Figure 10.

Vera Vladimirsky, “Paper Walls,” 2015–2018, exhibited in Dreamland Never Found, Jerusalem Biennale 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

No less important from the transnational perspective is the photo essay project titled Many Years (Figure 11a,b), a reconstructed journey comprising forty images taken between 2010 and 2014 in Israel and also in Ukraine, England, and Germany—countries where Vladimirsky went to visit family members who emigrated after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The images were compiled into a book, as noted on her site. In these documentary photos, her distanced but paradoxically emotive photographic gaze remains the same as that which characterized Last Apartment, although the images are produced without any manipulation. Reverting to Barthes, they have the duality of being un-coded due to their simple family-album-photo appearance, a characteristic that is, however, coded in the context of the sense of “transitional home” and transnational links full of dislocated and relocated objects, signs of alienated identity, and life aboard a metaphorical “flying carpet” as a sort of radicant aesthetics. Again, the gaze comes to rest on the home space, one so dislodged from its family continuity as to have become unipersonal and defined no less by what is outside the frame than by what is in it. From this angle, one image is exceptional: “A rare self-portrait in my grandparents’ home in Ukraine and a small homage to Gerhard Richter” (2012) (Figure 12), as she titled it (Vladimirsky 2014a). It is one of the photos included in her artist book Many Years, published in 2014 (Vladimirsky 2014b). This image evokes the all-women transnational package with the multilayered cultural, national, aesthetic, and emotive levels that have evolved within it, to which it adds intensity by breaking down the typical distance that the artist establishes from “home” and family sites. In her grandparents’ home, fusional times come about and a physical and visceral link is achieved. In this atypical photo, we can see some affinity with Sher’s staging of an approach that refers to art history. The granddaughter, a young woman, is both an adolescent who misses her childhood and an artist who quotes a famous work. For the first time, the migrant body—her body—is the protagonist and the image carries a strangeness that, while intimate, is different from Paper Walls or the spatial home-based projects. Whereas in these projects the ascent of the body, the silence of the empty spaces, and the disengaged artifacts of the home are protagonists that represent radicant experiences, this photo serves as a sort of “translator.” Even though the artist occupies a space full of family memories, aromas, and words in the mother tongue, the past, the “origin,” is now absent and unattainable. As a result, she can manipulate all of these in an artistic setting. It seems that the subtitle wants to express “the impossibility of authenticity” that all of Vladimirsky’s works tackle. The intersection of gender and displacement emphasizes and amplifies this radicant dimension.

Figure 11.

(a) Vera Vladimirsky, Many Years series, 2010–2014. Retrieved from http://www.veravladimirsky.com/many-years, (b) Vera Vladimirsky, Many Years series, 2010–2014. Retrieved from http://www.veravladimirsky.com/many-years. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 12.

Vera, Vladimirsky “A Rare Self-Portrait in My Grandparents’ Home,” 2012. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BvJTa9igdIk/ Courtesy of the artist

Sarah Kaminker

My work originates in where I am. In 1990, I immigrated with my mother from the former Soviet Union to an old neighborhood in Ashkelon, Israel. I am in the process of establishing my identity, a kind of fluid identity in which I can live in harmony with the different, diverse, and even contradictory identities that I harbor. My identity is an emergent one: not only a singular self, a subjective matter, but one shaped by dynamic negotiation with the environment in which I live.(Kaminker 2019)

After graduating from Bezalel Academy in 2013, Sarah Kaminker focused her work on the fluidity of the feminine body and the boundaries of artistry in clay to express it. This stage of her career centered on hierarchies of gender and art materials as the class and ethnic dimensions that affected her life as an FSU woman immigrant in the Israeli social and geographical periphery bided their time to emerge. As they waited, they manifested a complex statement from the intersectional approach (Crenshaw 1991).

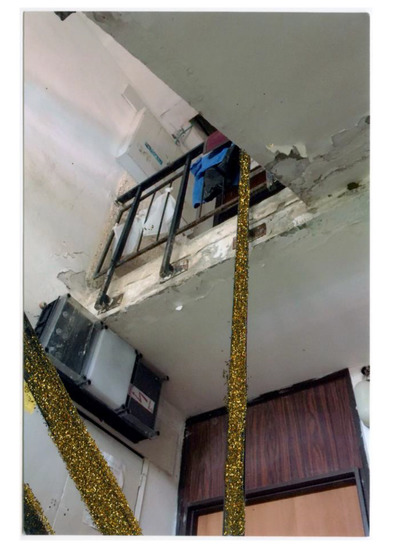

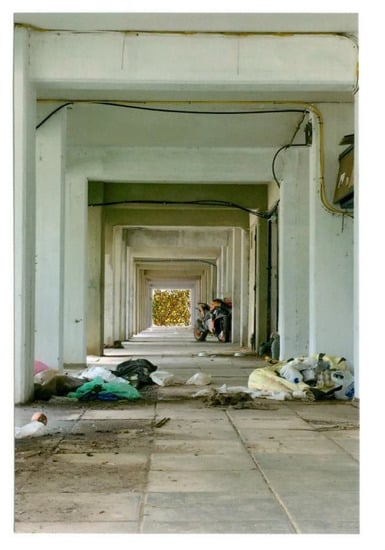

Kaminker spent all of 2019 documenting the places where she lived in precarious neighborhoods in Ashkelon. Her strategy is very different from Vladimirsky’s relocation photography inquiry and Sher’s intergenerational journey by stating places. In her current project, she aims to reconstruct the map of her immigration journey as an intersectional representation reflecting the junction of gender, class, ethic, and migration. Her mother, who still lives in the neighborhood where they first settled as a single-parent family, joined her. In three sequences, the two women, armed with video cameras, returned to all their erstwhile apartments. Choosing the cooperative work with her mother was not only a practical decision. From the intersectional point of view, this bond of solidarity between mothers and daughters in immigrant women’s single-parenthood is a gender issue that has social and economic implications. In this series, the dialogue between them, in situ and afterward, is not only part of the multilayered raw material but also a sort of co-author. In some places, they set their eyes on abandoned backyards full of waste (Figure 13); in others, they focused on interior staircases (Figure 14) or dilapidated façades of so-called “modernist housing” (Figure 15) defaced with graffiti that had also faded. Throughout, they tried to rewind their trajectory, guided only by what their eyes beheld, stopping wherever one of them suggested that they stop, recalling from the present the images that emerged with neither nostalgia nor fury nor shame. Sarah brings to the foreground the “double, triple, and sometimes quadruple forms of oppression: These are women in a male-dominated society, in a capitalist economy, and not part of the hegemonic ethnic, religious, or national group” (Dekel 2018, p. 30).

Figure 13.

Sarah Kaminker, “17 Yoseftal Str.” (Antiquities Neighborhood 3–4 Ashkelon series), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 14.

Sarah Kaminker, “5 Avshalom Habib Str.” (Antiquities Neighborhood 3–4 Ashkelon series), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 15.

Sarah Kaminker, “17 Yoseftal Str”. (Antiquities Neighborhood 3–4 Ashkelon series), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Kaminker describes her work as a detective story that she composes from evidence “left at the scene of the crime. […] I take the photos as an attempt to expose some ‘truth,’” she says. “Yet when I feel uncomfortable with this truth, I choose to cover it up by spattering it with gold powdered glitz” (Kaminker 2019). Unlike the provocative manner of Borian and Kurbatov and Cherkassky, Kaminker chooses a poetic vein, reexamining what she wants to do in the present with her multiple burden, where to place power-gold more as a mark of self-recognition than as a gesture of concealing this “truth.” The path of the power-gold traverses the series of photos and produces a metaphorical aerial root much as would a radicant, i.e., not linking the works but establishing stops and then starts for another journey (Figure 16). Without any practice that relates remotely to the impulse of “purifying, eliminating, extracting” (Bourriaud 2010, p. 35) as the modern discourse demands, or to the return to an imagined national or ethnic roots, Kaminker elaborates her radicant claim from an un-privileged place, “shaped by dynamic negotiation with the environment in which I live” (Kaminker 2019) that makes the precarious living places in the Israel periphery a central issue.

Figure 16.

Sarah Kaminker, “HaHistadrut Str.” (Antiquities Neighborhood 3–4 Ashkelon series), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

5. Conclusions

Bourriaud’s radicant aesthetic sheds light on the multiplicity of simultaneous and successive en-rootings that the radicant or the nomad can produce versus the simplified “multicultural” standardization that global capitalism demands. In the Israeli field of art, however, in which the Law of Return makes immigration a gendered ethno-religious issue, the case of “repatriated” Jews from the FSU—the 1990s ‘aliya’—is a singular case within the generality as it was shown. The ways in which the first and, especially, the 1.5 generation of FSU artists re-elaborate their identity in the context of global processes of migration and the rise of the transnational discourse combine a nomadic state of mind with intersectional struggles.

While the explicitly provocative approach of some women artists toward the main issues in the field relating to the FSU 1.5.generation has resonated in the public, Sher, Vladimirsky, and Kaminker in their photographic works portray an intimate transnational meditative state of mind that, although far from indulging in overt social critique, makes a powerful impact that allows us to reflect on the way photography can reveal much more than a documentary description of the 1990s ‘aliya’. Like the radicant metaphor, the connotative message of the photos at the level of its production and reception must be re-coded by crossing different platforms as a continuum of uprooting and re-rooting, which, in turn, offers a multiplicity of interpretations. Despite the different themes and approaches that characterize each of these artists and despite their age differences within the first or 1.5 generation, their oeuvres nod to strangeness and displacement and show variant characteristics of what is called “home,” “national identity,” and “promised land” that have been so fundamental in the Israeli art discourse since its inception. In their works, more than a quality of “Israel-less,” the visual effect is one of an Israeli-ness that still refers to the same national issue. From the radicant perspective, it seems than the tension between Israeli-ness and Israeli-less is an unresolved theme in our times. After Nancy Frazer, who argues that struggles for recognition take place at times of transcultural interaction and accelerated migration and global media flows, and demands more than “simplify[ing] and reify[ing] group identities” (Frazer 2000, p. 108), it seems that neither total assimilation into the national cultural landscapes nor the specific identity of the self-group, but rather the living places of social exchange, can play a fundamental role as substitutes for the lost place of birth. These living places are shown in Sher’s, Vladimirsky’s and Kaminker’s works as fantastic and stylized scenarios, deconstructed and recomposed apartments or dilapidated peripheral homes marked with power-gold. These representations deal with the complexity of people’s lives, the multiplicity of their self-identities, and the clashing pulls of their various affiliations. Living places create a diverse version of home, a real and imagined place of the family, and family is the medium and the object of a continuum between the real and the optional world, acting like a magic carpet that flies over the territorializing of Israeliness or even seeks to undermine it. By refusing to privilege remedies for misrecognition and exclusion of the “Russian” immigrants through the valorization of origin identities only, the approaches adopted by Sher, Vladimirsky, and Kaminker refrain from essentializing consensual configurations of both the Israeli field of art and the FSU origins.

Funding

This research was supported by the Research Unity- Oranim Academic College of Education, 2018–2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aberbuch, Masha. 2016. The “Russian Whore” is Making Art on You: Retrieved from Ha’aretz. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/art/.premium-MAGAZINE-1.2968670 (accessed on 9 June 2016).

- Barak, Yair. 2009. Memento Mori, Thoughts about Angelika Sher’s Twilight Sleep. Tel Aviv: Dresdener Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Ronald. 1978. The Photographic Message. In Image, Music, Text. Edited by Roland Barthes. Translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill & Wang, pp. 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barzon Makai, Sophie. 2019. Once in a Distant Land between Israel and Lithuania. Retrieved from Beeri Art Gallery. Available online: http://www.gallerybeeri.co.il/exhibition/%d7%90%d7%a0%d7%92%d7%9c%d7%99%d7%a7%d7%94-%d7%a9%d7%a8 (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Ben Dayan, Ortal. 2012. Do Not Upload Art to Facebook, All the “Arsim” Mizrahim Will Come, from Erev Rav-Digital Art Magazine. Available online: https://www.erev-rav.com/archives/19259 (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2010. The Radicant. Translated by James Gussen, and Lili Porten. New York: Lukas & Sternberg. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2012. Nomadic Theory. In The Portable Rosi Braidotti. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Brook-Blom, Hilli. 2017. From Russia with Love: Talking about Novy God, Migration and Longing with the Artist and Social-Media Star Xenia Sova. Available online: http://brook-it.com/%D7%9E%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%A1%D7%99%D7%94-%D7%91%D7%90%D7%94%D7%91%D7%94/ (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity, Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 436: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 2017. “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later.” Columbia Law School. 8 June 2017. Available online: https://www.law.columbia.edu/pt-br/news/2017/06/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Dekel, Tal. 2013. Women and Migration. Tel Aviv: Resling. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2016a. In Search of Transnational Jewish Art: Immigrant Women Artists from the Former Soviet Union in Contemporary Israel. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 151: 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, Tal. 2016b. Transnational Identities: Women, Art and Migration in Contemporary Israel. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2016c. Welcome Home? Israeli-Ethiopian Women Artists and Questions of Citizenship and Belonging. Third Text 2: 310–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2018. Sexism and Racism in Israel Arts and Their Impact on the Ability of Women Artists from Various Social Groups to Earn a Fair Living. In For My Sister: Racism, Sexism and Multiple Discrimination of Women as Reflected in Israeli Visual Art. Tel Aviv: Achoti, pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Della Pergola, Sergio, and Shulamit Reinharz. 2009. Jewish Intermarriage around the World. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Deuelle Luski, Aim. 2012. Introduction. In Reality Trauma and the Inner Grammar of Photography Spilman Institute. Edited by Aim Deulle Luski. Tel Aviv: Shpileman Institute of Photography, pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, Nancy. 2000. Rethinking Recognition. New Left Review 3: 108. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe, Shelly, and Nicole M. Else-Quest. 2012. The role of transnational feminism in psychology: Complementary visions. Psychology of Women Quarterly 36: 158–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilat, Yael. 2017. Collective Practices in the Field of Art in Israel in Times of Precarity: The New Barbizon as a Case Study. Dvarim, Multidisciplinary Academic Journal—Solidarity and Others, October 10, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Guilat, Yael. 2019a. “Living Room” and “Family Gaze” in Contemporary Israeli Art: Comparative Perspectives on Cultural-Identity Representations. Israel Studies 24: 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilat, Yael. 2019b. Home Sweet Home: The Domestic Sphere in Contemporary Israeli Art as a Space of Intercultural Encounters and Conflicts. In Encuentros Interculturales en Sociedades Multiculturales: Inmigración, Multilingüismo y Multiculturalidad. Edited by Carmen Egea Jimenez. Granada: Collecion Eirene, Universidad de Granada, pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- Herr, Ranjoo Seodu. 2014. Reclaiming third world feminism: Or why transnational feminism needs third world feminism. Meridians 12: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminker, Sarah. 2019. Identity as a Detective Action: An Artist’s Statement. In HOTAM Stamp ABR Exhibition. Tivon: Museum Kupperman, Oranim College. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Chaya, and Zvi Eisikovitz. 2011. Continuity and Discontinuity of Violent and Nonviolent Behavior: Toward a Classification of Male Adolescent Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel. Sociological Focus 4: 314–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatov, Sasha, and Vanene Borian. 2016. About Shasha Kurbatov’s and Vanene Borian’s Works. Retrieved from Korbatov-Borian Graduates’ Stories. Shenkar Academy. Available online: https://www.shenkar.ac.il/he/news_items/haaretz-korbatov-borian (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Leopold, Liliya, and Yossi Shavit. 2013. Cultural Capital Does Not Travel Well: Immigrants, Natives and Achievement in Israeli Schools. European Sociological Review 3: 450–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Julia. 2012. Introduction: The Pragmatic Power of Culture in Migration. In Russians in Israel: The Pragmatics of Culture in Migration. Edited by Julia Lerner and Rivka Feldhay. Jerusalem: Van Leer and Hakibbutz Hamehuhad Press, pp. 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ari, Lilach. 2013. Multiple Ethnic Identities among Israeli Immigrants in Europe. International Journal of Jewish Education Research 5: 203–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lomsky-Feder, Edna, and Tamar Rapoport. 2010. Visibility in Immigration: Body, Gaze, Representation. Jerusalem: The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad. [Google Scholar]

- Mesh, Gustavo S. 2002. Between Spatial and Social Segregation among Immigrants: The Case of Immigrants from the FSU in Israel. The International Migration Review 36: 912–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moctezuma Longoria, Miguel. 2008. Trans-nationality and Transnationalism. Papeles de Poblacion 57: 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- O’Really Herrera, Andrea. 2011. Cuban Artists across the Diaspora: Setting the Tent against the House. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philippov, Michael. 2010. Ex-Soviets in the Israeli Political Space: Values, Attitudes and Electoral Behavior. College Park: The Joseph and Alma Gildenhorn Institute for Israel Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Alexandra. 2014. Both Here and There: Canadian Artists and the Berlin Experience. International Contemporary Art volume 122: 39–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg, Elena. 2018. Russian Women with No Sense of Humor and Their Friends: Young Russian-Speakers in the Public Sphere in Israel. In For My Sister: Racism, Sexism and Multiple Discrimination of Women as Reflected in Israeli Visual Art. Edited by Shula Keshet (Kashi). Tel Aviv: Achoti, pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, Yaniv. 2017. The New Barbizon, Back to Life, Catalogue. Ein Harod: Ein Harod Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnik-Brenner, Hilla. 2009. Do You Want to Feel that Your Family is a Normal One? Go See Angelika Sher’s Exhibit, Featuring Home and Family Scenes Where the Alien, the Distant and the Strange Dominate. Ha’aretz, February 20. Retrieved from haaretz. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/art/1.3346668 (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Shternshis, Anna. 2006. Soviet and Kosher: Jewish Popular Culture in the Soviet Union 1923–1939. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sova, Xenia. 2017. Russia Yam-Tichonit. Retrieved from Youtube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qs0Y1JtF_L4 (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Vladimirsky, Vera. 2014a. Many Years. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BvJTa9igdIk/ (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Vladimirsky, Vera. 2014b. Vera Vladimirsky, “Vera Vladimirsky Art Site,” 10 February 2014, from Vera Vladimirsky’s Art Site. Available online: http://www.veravladimirsky.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2017).

| 1 | The Israeli Law of Return entitles anyone who has a Jewish grandparent, or is married to a Jew, to immigrate and receive citizenship. The immigration wave from the FSU included many who are not Jewish under the halakha (rabbinical law), such as children of a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother, grandchildren of Jews, or non-Jewish spouses of Jews. In 1988, a year before the immigration wave began, 58 percent of married Jewish men and 47 percent of married Jewish women in the Soviet Union had non-Jewish spouses. Some 26 percent of FSU immigrants to Israel since then—240,000 people—had non-Jewish mothers and thus are not considered Jewish under religious law (Della Pergola and Reinharz 2009). |

| 2 | “Aliya” being the Jewish and Zionist term for immigration, literally “ascent.” |

| 3 | I use the word “nomadic” figuratively, as Rosi Braidotti (2012) defines it: “My project of feminist nomadism traces to more than an intellectual itinerary; it also reflects the existential situation as a multicultural individual, a migrant who turned nomad.” |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).