Seeing the Dog: Naturalistic Canine Representations from Greek Art

Abstract

Animals frequently go unrecorded in publications and museum captions… [and] rarely are individual species indexed in publications … The art of the ancient Mediterranean is replete with images of animals, and much Classical art features animals prominently, but there are very few modern scholarly works that seek to analyze the semiotics of the depicted animal.2

1. The Literary Evidence

2. The Dog in Greek Art

3. Canine Body Language in Greek Art

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boardman, John. 1966. Attic Geometric Vase Scenes, Old and New. JHS 86: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodson, Liliane. 1980. Place et fonctions du Chien dans le monde antique. Ethnozootechnie 25: 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bodson, Liliane. 1983. Attitudes toward Animals in Greco-Roman Antiquity. International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems 4: 312–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bodson, Liliane. 1990. Nature et statut des animaux de compagnie dans l’antiquité gréco-romaine. In Xes Entretiens de Bourgelat. Lyon: École nationale de Médecine vétérinaire et Fondation Marcel Mérieux, pp. 167–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bodson, Liliane. 2000. Motivations for Pet-keeping in Ancient Greece and Rome: A Preliminary Survey. In Companion Animals and Us: Exploring the Relationships between People and Pets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Boegehold, Alan. 1999. When a Gesture Was Expected: A Selection of Examples from Archaic and Classical Greek Literature. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, John, and Hellen Nott. 1995. Social and Communication Behaviour of Companion Dogs. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Douglas, Adrian Phillips, and Terence Clark, eds. 2001. Dogs in Antiquity. Anubis to Cerberus. The Origins of the Domestic Dog. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Broodbank, Cyprian. 2000. An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bussitil, J. 1969. The Maltese Dog. G&R 47: 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Gordon, ed. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet. 1995. Origins of the Dog: Domestication and Early History. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Coldstream, J. N. 1994. Warriors, Chariots, Dogs and Lions: A New Attic Geometric Amphora. BICS 39: 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coren, Stanley. 2000. How to Speak Dog. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia, Una R. 2005. The Decorum of a Defecating Dog. Print Quarterly 22: 119–32. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Simon J. M., and François R. Valla. 1978. Evidence for Domestication of the Dog 12,000 Years Ago in the Natufian of Israel. Nature 276: 608–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Leslie Preston. 1984. Dog Burials in the Greek World. AJA 88: 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, Mark. 2011. How the Dog Became the Dog. London: Overlook Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Dover, Kenneth James. 1989. Greek Homosexuality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Arthur. 1921. The Palace of Minos at Knossos. London: MacMillan and Co, vol. IV.ii. [Google Scholar]

- Fögen, Thorsten, and Edmund Thomas, eds. 2017. Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M. W. 1970. A Comparative Study of the Development of Facial Expressions in Canids; Wolf, Coyote and Foxes. Behaviour 36: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, Cristiana. 2014. Shameless: The Canine and the Feminine in Ancient Greece: With a New Preface and Appendix. Translated by Matthew Fox. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Furtwängler, Adolf, and Karl Reichhold. 1932. Griechische Vasenmalerei. 3 vols. Munich: Bruchman. First published 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Gácsi, Márta, Ádám Miklósi, Orsolya Varga, József Topál, and Vilmos Csányi. 2004. Are Readers of Our Face Readers of Our Minds? Dogs (Canis Familiaris) Show Situation-dependent Recognition of Human’s Attention. Animal Cognition 7: 144–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galibert, Francis, Pascale Quignon, Christophe Hitte, and Catherine André. 2011. Toward Understanding Dog Evolutionary and Domestication History. Comptes Rendus Biologies 334: 190–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Kun, Kerstin Meints, Charlotte Hall, Sophie Hall, and Daniel Mills. 2009. Left Gaze Bias in Humans, Rhesus Monkeys and Domestic Dogs. Animal Cognition 12: 409–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilakis, Yannis. 1996. A Footnote on the Archaeology of Power: Animal Bones from a Mycenaean Chamber Tomb at Galatas, NE Peloponnese. ABSA 91: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, Alistair. 2014. Animals in Classical Art. In The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 24–60. [Google Scholar]

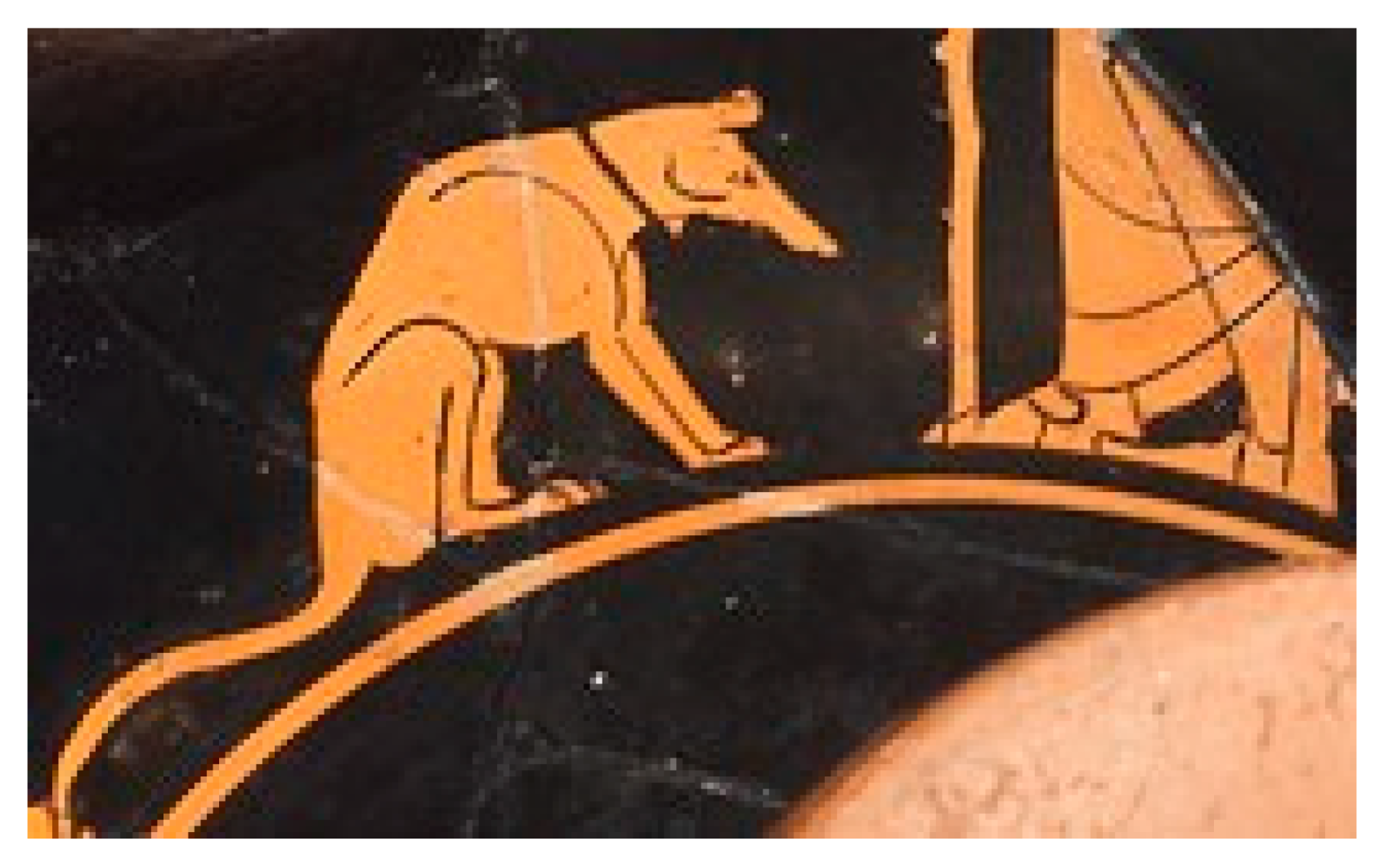

- Hare, Brian, and Michael Tomasello. 2005. Human-like Social Skills in Dogs? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9: 439–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, Brian, Michelle Brown, Christina Williamson, and Michael Tomasello. 2002. The Domestication of Social Cognition in Dogs. Science 298: 1634–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

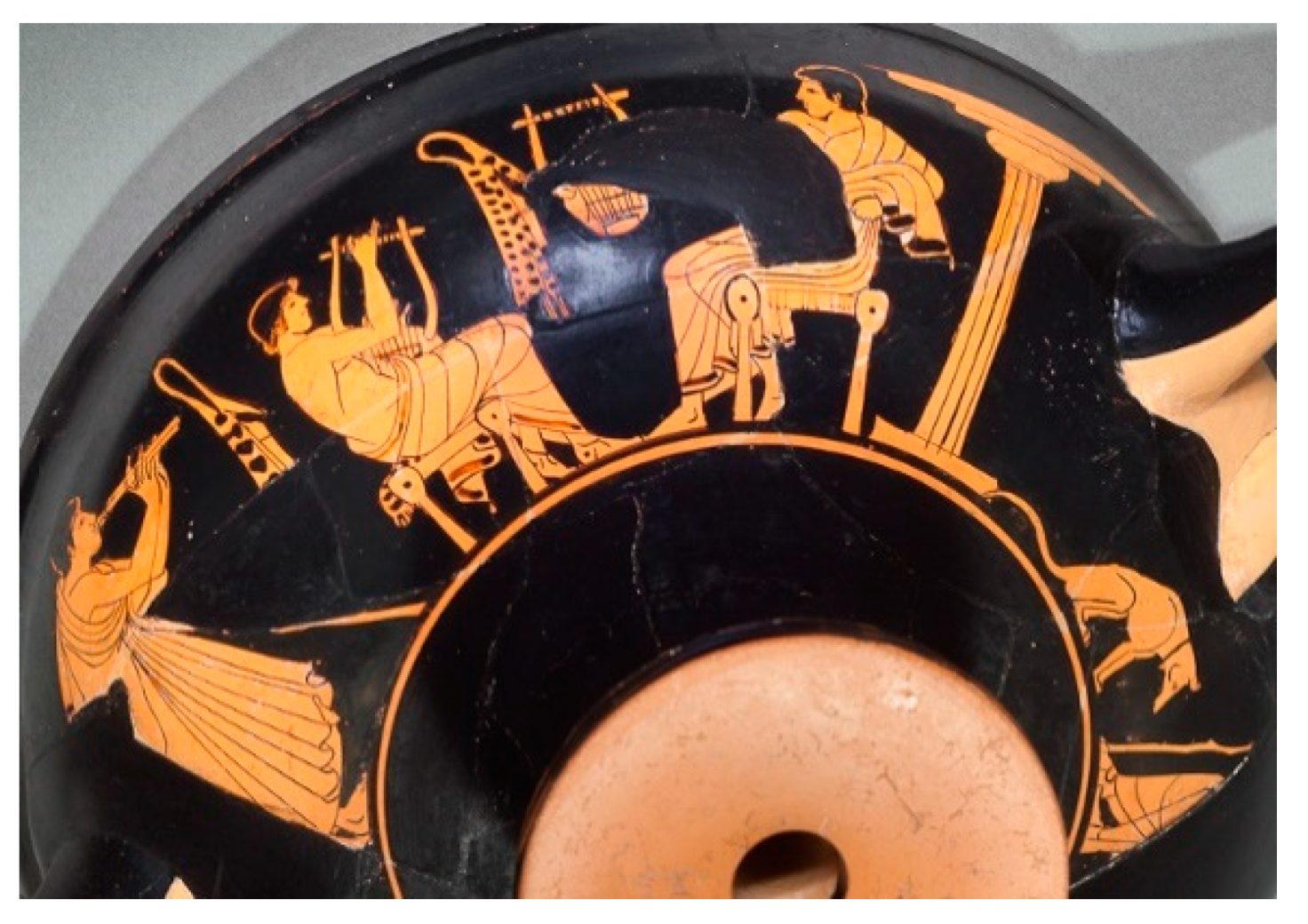

- Haworth, Marina. 2018. The Wolfish Lover: The Dog as a Comic Metaphor in Homoerotic Symposium Pottery. Archimède: Archéologie et histoire ancienne 5: 7–23. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01825115 (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Hickman, Jane. 2011. The Dog Diadem from Mochlos. In Metallurgy: Understanding How and Learning Why. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press, pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Sinclair. 1978. The Arts in Prehistoric Greece. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Horard-Herbin, Marie-Pierre, Anne Tresset, and Jean-Denis Vigne. 2014. Domestication and Uses of the Dog in Western Europe from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age. Animal Frontiers 4.3: 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, Thomas K., ed. 2003. Homosexuality in Greece and Rome. A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, Denison. 1964. Hounds and Hunting in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwit, Jeffrey. 2002. Reading the Chigi Vase. Hesperia 71: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Helen M. 1919. The Portrayal of the Dog on Greek Vases. Classical World 12: 209–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Patricia, Attilio Mastrocinque, and Sophia Papaioannou, eds. 2016. Animals in Greek and Roman Religion and Myth. Paper presented at the Symposium Grumentinum Grumento Nova, Potenza, Italy, June 5–7; Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, Juliane, and Marie Nitzschner. 2013. Do Dogs Get the Point? A Review of Dog-human Communication Ability. Learning and Motivation 44: 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Otto. 1913. Die antike Tierwelt. 2 vols. Leipzig: W. Engelmann. First published 1909. [Google Scholar]

- King, Arthur. 2004. Historical Perspective of Rabies in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: A Testament to Rabies by Dr. Arthur A. King. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchell, Kenneth. 2004. Man’s Best Friend? The Changing Role of the Dog in Greek Society. In PECUS. Man and Animal in Antiquity. Rome: Swedish Institute, pp. 177–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, Gabriella, Márta Gásci, József Topál, and Ádám Miklósi. 2012. Comprehension and Utilisation of Pointing Gestures and Gazing in Dog–human Communication in Relatively Complex Situations. Animal Cognition 15: 201–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, Sian, and Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones. 2018. The Culture of Animals in Antiquity: A Sourcebook with Commentaries. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liston, Maria, Susan Rotroff, and Lynn Snyder. 2018. The Agora Bone Well. Havertown: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Lobell, Jarrett A., Eric A. Powell, and Paul Nicholson. 2010. More than Man’s Best Friend. Archaeology 63: 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Manakidou, Eleni. 2015. Eros und siene Tiere auf Attischen Vasen. In Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, Österreich, Beiheft 2—ΦϒТА ΚAΙ ΖΩΙA. Pflanzen und Tiere auf griechischen Vasen. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, pp. 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- Marinatos, Nano, and Lyvia Morgan. 2005. The Dog Pursuit Scenes from Tell el Dab’a and Kea. In Aegean Wall Painting: A Tribute to Mark Cameron. London: British School at Athens, pp. 119–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, Adrienne. 2014. Animals in Warfare. In The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 282–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, Adrienne, John Colarusso, and David Saunders. 2014. Making Sense of Nonsense Inscriptions Associated with Amazons and Scythians on Athenian Vases. Hesperia 83: 447–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlen, Rene Henry Albert. 1971. De Canibus. Dog and Hound in Antiquity. London: J.A. Allen. [Google Scholar]

- Miklósi, Ádám. 2003. A Simple Reason for a Big Difference: Wolves Do Not Look Back at Humans, but Dogs Do. Current Biology 13: 763–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moignard, Elizabeth. 1982. The Acheloos Painter and Relations. ABSA 77: 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Mary B. 2004. Horse Care as Depicted on Greek Vases before 400 B.C. Metropolitan Museum Journal 39: 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Mary B. 2008. The Hegesiboulos Cup. Metropolitan Museum Journal 43: 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, Darcy F. 1994. The Early Evolution of the Domestic Dog. American Scientist 4: 336–47. [Google Scholar]

- Neils, Jenifer. 2014. Hare and the Dog: Eros Tamed. In Approaching the Ancient Artefact. Representation, Narrative, and Function. A Festschrift in Honor of H. Alan Shapiro. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 311–18. [Google Scholar]

- Orphanidis, Laia. 1998. Introduction to Neolithic Figurine Art. Southeastern Europe and Eastern Mediterranean. Athens: Academy of Athens Research Centre for Antiquity, Monograph 4. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20140912175029/http://www.neolithic.gr/pdf/introduction_en.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2019).

- Papageorgiou, Irini. 2008. The Mycenaean Golden Kylix of the Benaki Museum: A Dubitandum? Mouseio Benaki 8: 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, William Armstrong. 1996. Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrakova, Anna. 2015. The Emotional Dog in Attic Vase-Painting; Symbolical Aspects and instrumental narrative Function. In Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, Österreich, Beiheft 2—ΦϒТА ΚAΙ ΖΩΙA. Pflanzen und Tiere auf griechischen Vasen. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, pp. 292–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pevnick, Seth D. 2014. Good Dog, Bad Dog: A Cup by the Triptolemos Painter and Aspects of Canine Behavior on Athenian Vases. In Athenian Potters and Painters: Volume III. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 155–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rassmussen, Tom. 2016. Interpretations of the Chigi Vase. BABESCH 91: 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Gisela. 1970. The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks, 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

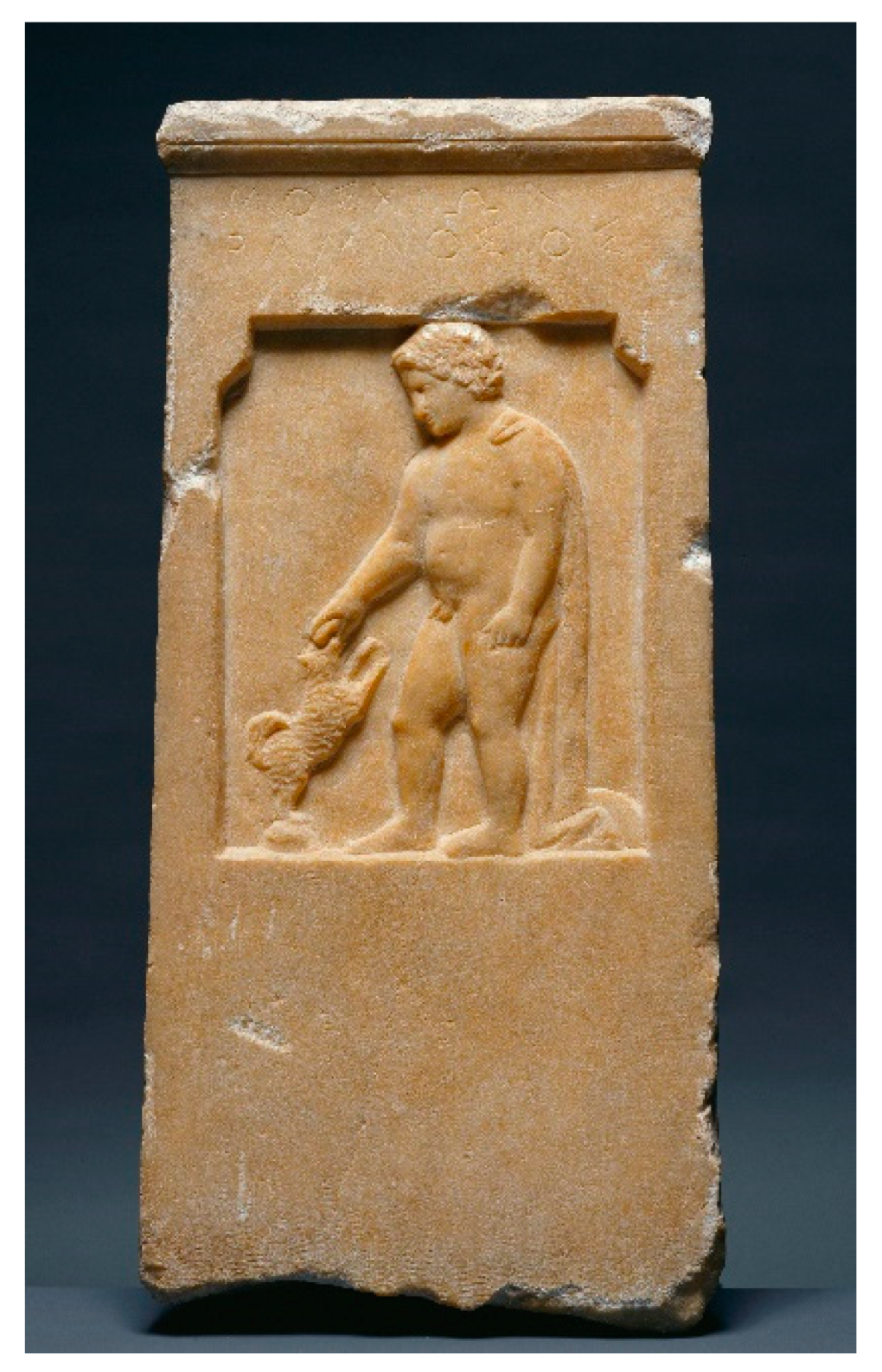

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo. 1971. The Man-and-Dog Stelai. JDAI 86: 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rombos, Theodora. 1988. The Iconography of Attic Late Geometric II Pottery. Jonsered: Paul Åströms Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Schmölder-Veit, Andrea. 2008. Zwischen Leben und Tod: Tiere in geometrischen Prothesisbildern. In Mensch und Tier in Der Antike: Grenzziehung und Grenzüberschreitung, Symposion Vom 7. Bis 9. April in Rostock. Wiesbaden: Reichert, pp. 119–37. [Google Scholar]

- Scodel, Ruth. 2005. Odysseus’ Dog and the Productive Household. Hermes 133: 401–8. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, James. 1995a. From Paragon to Pariah: Some Reflections on Human Attitudes to Dogs. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour, and Interactions with People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 246–62. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, James, ed. 1995b. The Domestic Dog. Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Barbara. 1997. Canine Communication. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 27: 445–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliano, Armando. 2012. Stele funeraria con motivo Man and Dog da Kyme eolica. Orizzonti 13: 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- van den Dreisch, Adrian, and Joachim Boessneck. 1990. Die Tierreste von der mykenischen Burg Tiryns bei Nauplion/Peloponnes. In Tiryns: Forschungen und Berichte, XI. Edited by Hans-Joachim Weisshaar. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, pp. 87–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ventris, Michael, and John Chadwick. 1973. Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 2nd ed. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Reden, Sitta. 1995. Exchange in Ancient Greece. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Wiencke, Martha Heath. 1986. Art and the World of the Early Bronze Age. In The End of the Early Bronze Age in the Aegean. Leiden: Brill, pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Younger, John. 2005. Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Prof. Bodson’s output has been prolific. Most notable for the current study are (Bodson 1980, 1983, 1990, 2000). Note as well the internet-based bibliography assembled by Thorsten Fögen, https://www.telemachos.hu-berlin.de/esterni/Tierbibliographie_Foegen.pdf. Most recently, see (Campbell 2014; Fögen and Thomas 2017; Johnston et al. 2016; Lewis and Llewellyn-Jones 2018). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | The argument is not confined to Classical times. One wishes dearly that Evans had carefully cataloged bones from Knossos. Contrast, for example, the careful work done by van den Dreisch and Boessneck (1990) at Tiryns and Liston et al. (2018) in the Athenian Agora. |

| 4 | See (Harden 2014, pp. 33, 47; cf. Moore 2004, p. 60, n. 28) for references. The stray mongrel dogs who undoubtedly roamed Athens and any other location where they could act as garbage disposal units must have been numerous, but they are rarely depicted. On such pariah dogs, see (Serpell 1995a,b) in general and (Liston et al. 2018, pp. 58–59). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Petrakova (2015, p. 296), who states that in the late sixth and early fifth centuries “certain vase-painters of the Archaic period intentionally used dogs as rhetorical elements, for the visualization of emotions, metaphor or hyperbole, appears quite persuasive”, informs much of what is to follow. |

| 7 | All dates are BCE unless otherwise stated. |

| 8 | The breathing is variously given as smooth or rough in the lexicons. |

| 9 | Θωύσσω is Homeric and can also mean to cry out to the hounds. In English, foxhounds on the hunt are said to “cry out” when on the scent. Similarly, their handlers “cry out” to the dogs. |

| 10 | Several citations from other authors can be found in the major lexicons. |

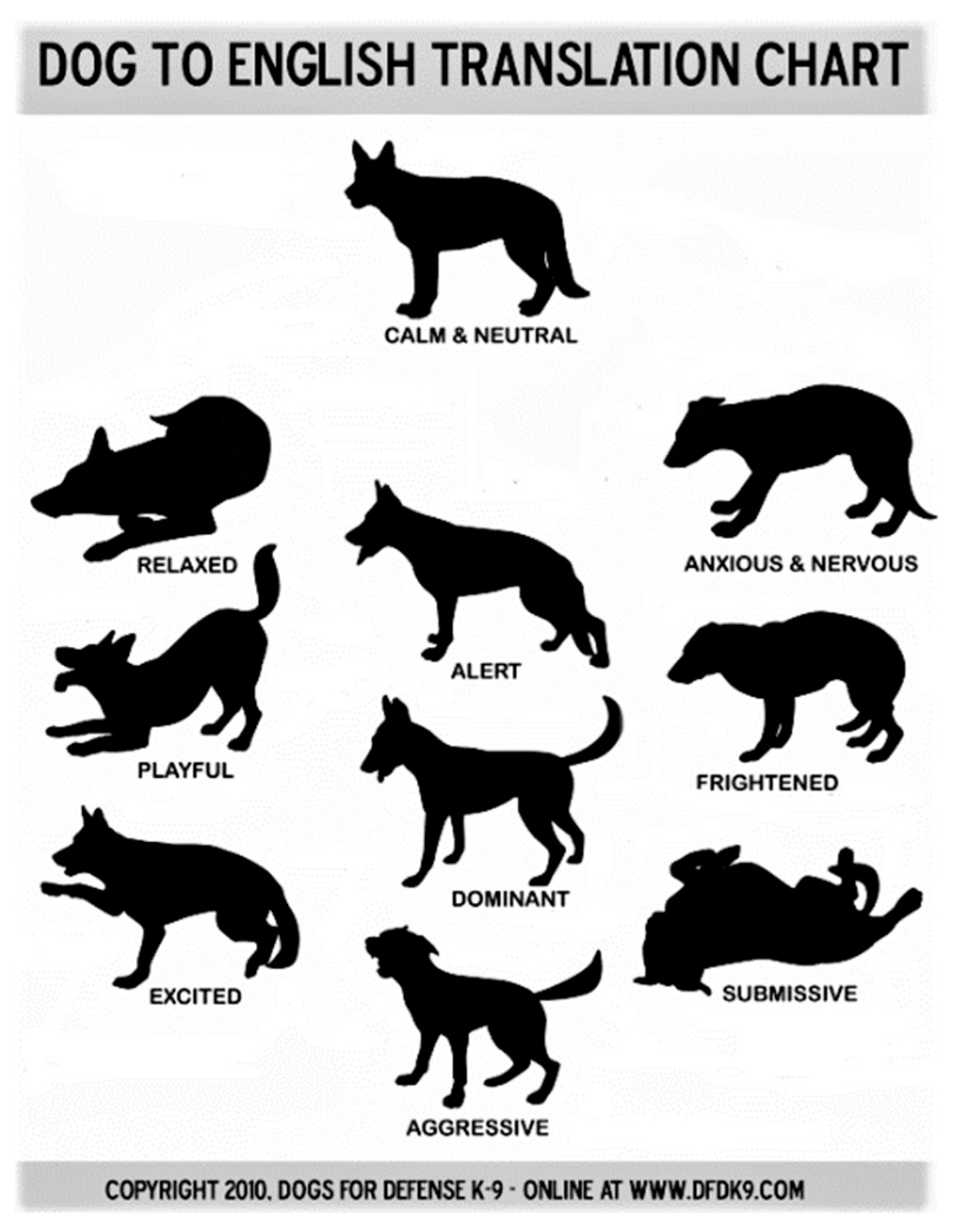

| 11 | Fox (1970) surveys the behavior throughout the Canidae. For a complete description of the submissive grin, see (Simpson 1997, p. 455). |

| 12 | On breeders of ancient Greek dogs, see (Hull 1964, pp. 39–43) and cf. horse breeding as described by Moore (2004, pp. 54–56). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | On the domestication of the dog, in addition to what follows, see (Morey 1994; Lobell et al. 2010) and the thorough study of (Derr 2011). |

| 15 | See (Galibert et al. 2011, p. 191). |

| 16 | They also discuss the morphological changes that occurred as the wolf became the dog. |

| 17 | See especially figs 10.1–10.4 and 95–96 for other representations in Minoan and Cycladic art. |

| 18 | See (Johnson 1919, pp. 210–11; Hickman 2011, fig. 10.6). A similar vessel was later found at Zakro. See further, (Wiencke 1986, pp. 86–87). |

| 19 | A search of the Corpus of Minoan and Mycenaean Seals (CMS) on the Arachne website yields 279 results, although the figures are often quite schematic, and the CMS tends to identify these as “Löwe oder Hund”. Some seem more clearly canine. To identify a few: CMS-VI-357-1 (with collar) and CMS-XI-008b-1 (canine ears). Hunts: CMS-VI-180-1, CMS-VI-400-1 CMS-VI-153b-1. Some show a female suckling her pup: CMS-II, 8-289-1, CMS-VII-066-1(with a collar and lead?). Other examples include: dog scratching (see below) on CMS-I-255-1, CMS-I-256-1, CMS-II,6-076-1 et al.; head of a dog, resembling a Molossian/mastiff-type breed, CMS-II,5-299.1 and 300-1 and CMS-II,5-299-1; a pair of dogs of the hunting type, CMS-VS3-396-1; play position (see below) CMS-VII-216b-1; accompanying a warrior or hunter, CMS-II,8-236-1. |

| 20 | Some excellent examples of Minoan and Mycenaean images of dogs can be found in (Papageorgiou 2008, pp. 9–37). |

| 21 | A Late Helladic hound’s head rhyton in the Ashmolean Museum, AE.298 is a notable exception. |

| 22 | But cf. Day (1984, p. 26), who notes the parallel to the table dogs (τραπεζῆες) Achilles sacrifices at the Grave of Patroclus (Iliad 23.171–77). |

| 23 | E.g., British Museum 1889, 0418.1 (the Macmillan Aryballos); Cleveland Museum of Art, 341.15; Taranto Museo Archeologico Nazionale, 4173; Louvre, CA3744A. |

| 24 | |

| 25 | Schmölder-Veit (2008) describes this development well. |

| 26 | This change is traced in (Kitchell 2004). See also (Franco 2014, pp. 17–53; Petrakova 2015, p. 292 with notes, who lists several categories of canine and human interaction). |

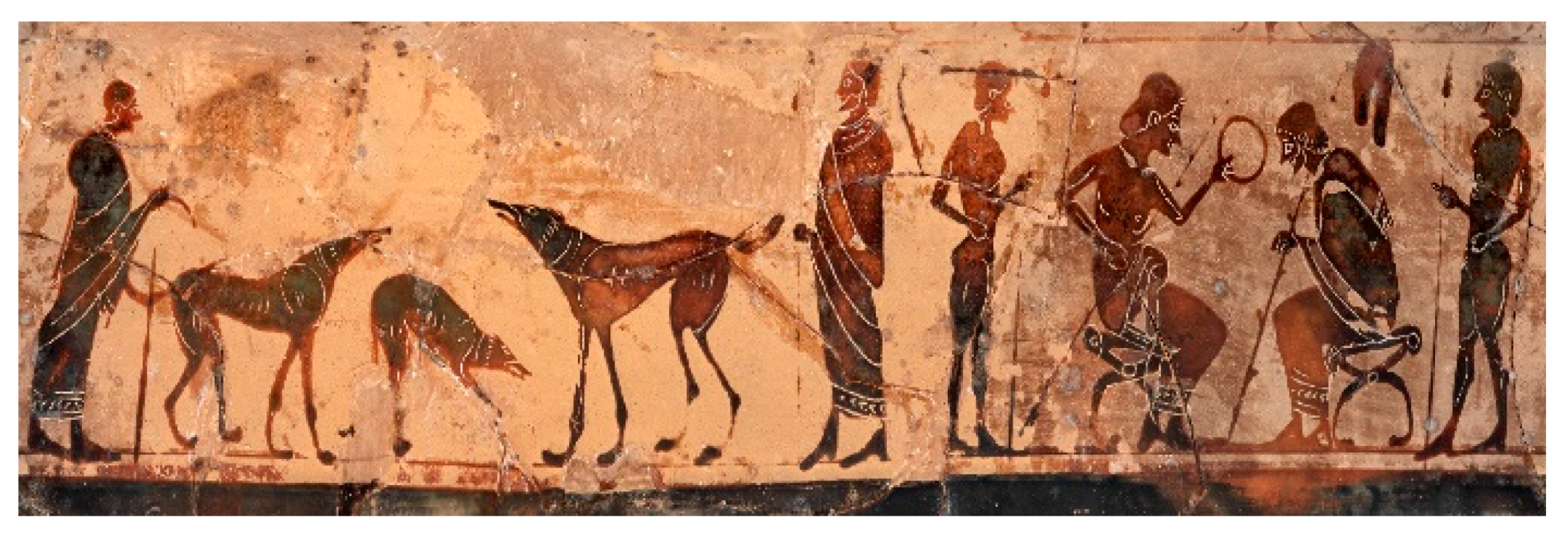

| 27 | See the careful reading of the vase by Hurwit (2002) who, however, gives only passing notice to the dogs (pp. 8–9). For the friezes in question, see his figs. 6–7 and (Rassmussen 2016, figs. 1–4). |

| 28 | Quoted by Harden (2014, p. 24). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Cf. (Kitchell 2004). |

| 31 | Black figure: Athens, National Museum 489. Red figure examples include Copenhagen, Thorvaldsen Museum, 99A and a krater attributed to the Pan Painter, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 10.185. A fragmentary mug in Wurzburg, Martin von Wagner Museum H5356, shows more animated dogs, even delineating one as female. |

| 32 | Bussitil (1969, pp. 88–93) offers an overview of the animal. See also (Brewer et al. 2001, pp. 85–86; Moore 2008, pp. 16–18). |

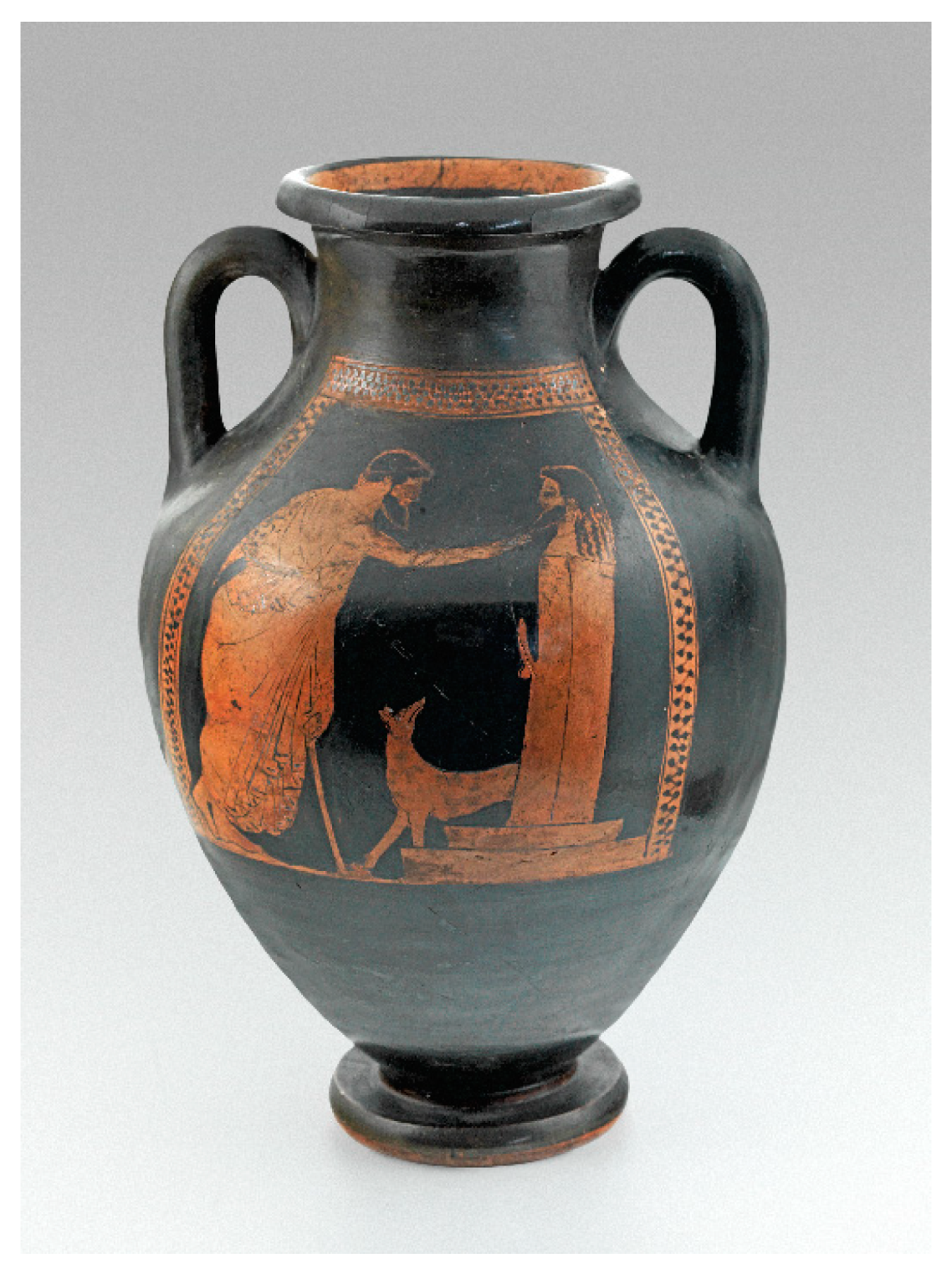

| 33 | Although Reden generally ignores the animals as gifts, as does Percy (1996). Dover (1989, p. 92) and Younger (2005, p. 70, s.v. “Love-gifts”) offer a small list of animal gifts. Examples of such scenes can be seen on vases: Munich, Antikensammlungen: 2290A (BAPD 9533) 575–525; Vatican City, Museo Gregoriano Etrusco Vaticano: 352 (BAPD 301064) 575–525 (on which, see below); Providence (RI), Rhode Island School of Design: 13.1479 (BAPD 301624). |

| 34 | E.g., a psykter from the Basel market, (BAPD 718) 550–500 (cf. Moignard 1982 Pl. 14a, b); British Museum B679, 524–475 (BAPD 4824), where the dog is female; Private collection, 550–500 (BAPD 16042; Museo Nazionale Tarquiniese RC6823. 528–475 (BAPD 7648); Louvre, Campana Collection F2 (BAPD 10707); Tübingen, Eberhsard-Karls Univ., Arch. Institute S101391 (BAPD 11642) where the dog is a maltese and seems to share the couch with the youth. |

| 35 | Jenna Rice, of the University of Missouri, generously shared with me Chapter Four (“Συστρατιώτης Κύων: The Dog in the Ancient Greek Military”) of her soon to be submitted dissertation, where she categorizes over 100 departure scenes depicting canines. Note especially: Market, 550–500 (BAPD 9032300); Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico 24 (BAPD 13161) 525–475, where a man holding two spears seems to reach out to pet the dog; Geneva, Musee d’Art et d’Histoire: 14989.1937 (BAPD) 550–500. Cf. (Moignard 1982, Pl. 10a), by the Acheloos Painter, who seems to have been fond of portraying dogs. |

| 36 | Examples include the following: Kurashiki, Ninagawa, 23 (BAPD 7307), 575–525; Brussels, Musees Royaux, Unknown, Somzee Collection, Brussels, van Branteghem, A1375 (BAPB 3277); Cleveland Museum of Art, 29.135, 525–475 (BAPD 759). It is often difficult to differentiate scenes of military training from certain athletic competitions. |

| 37 | On stelae, see (Ridgway 1971; Taliano 2012). Butcher: Heidelberg Univ., 253, Olpe, 525–475, Leagros Group (BAPD 10598) 550–500. Fishmonger: Berlin Antikensammlung F1915 (BAPD 3032328). It is just possible each is a sacrifice scene, but we can imagine dogs frequented these as well. |

| 38 | My thanks to Chris Crawford of Dogs for Defense K-9 for granting permission to use this chart. Further information may be found at www.dfdk9.com. |

| 39 | E.g., the krater by the Pan Painter depicting the death of Actaeon, MFA 10.185, ca. 470 (BAPD 206276). |

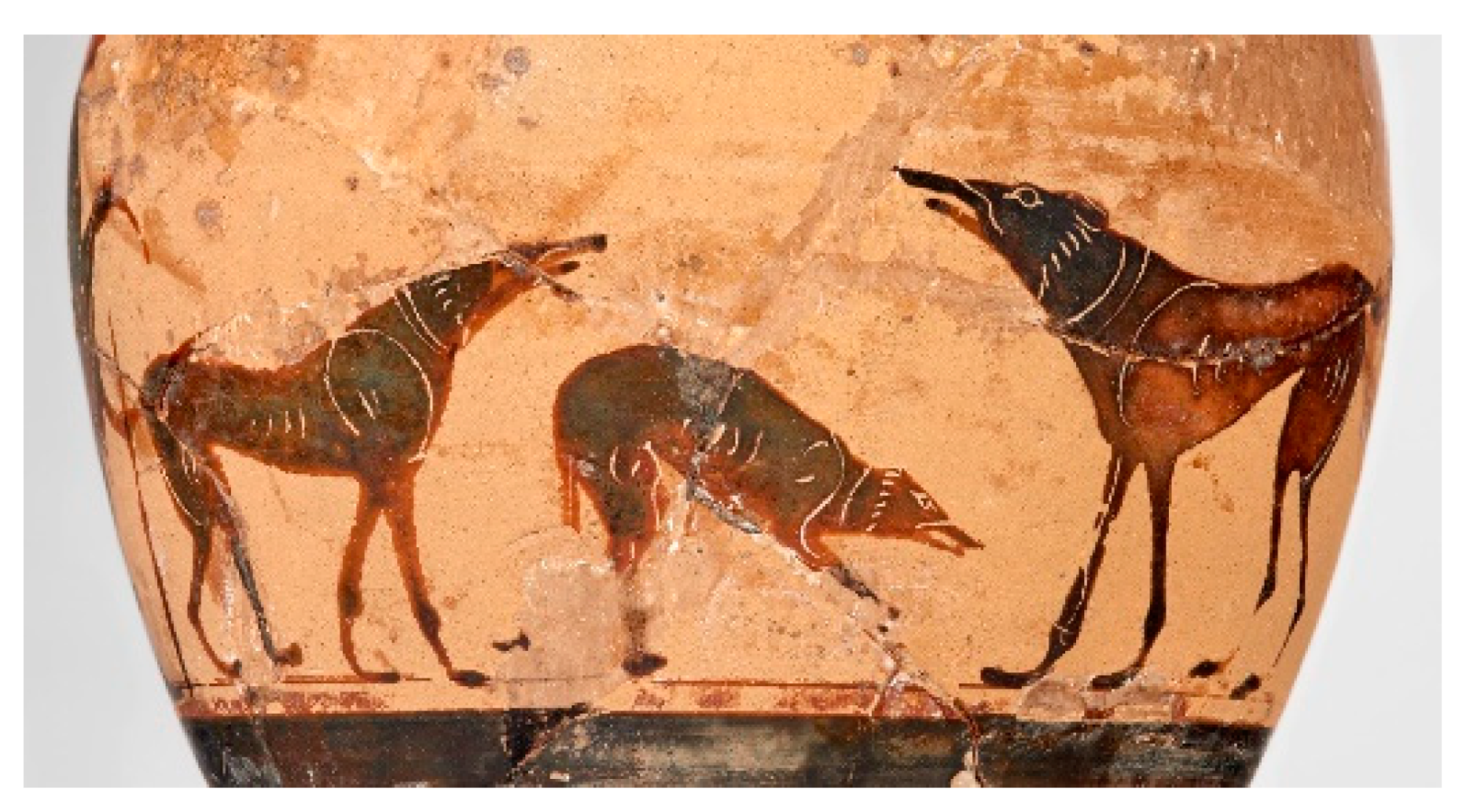

| 40 | A similar scene is depicted on a seal in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (99.356) dated to the early fifth century. Dogs also scratch the ground in order to raise a scent. This is well depicted on a cup dated to 500–450 and attributed to the Onesimos Painter in the same museum (95.27, BAPD 203223). |

| 41 | I am deeply indebted to Martin Bürge, curator of the Archäologische Sammlung at the University of Zurich, who not only issued permission to use images, but also had new photographs taken to provide the views presented here. |

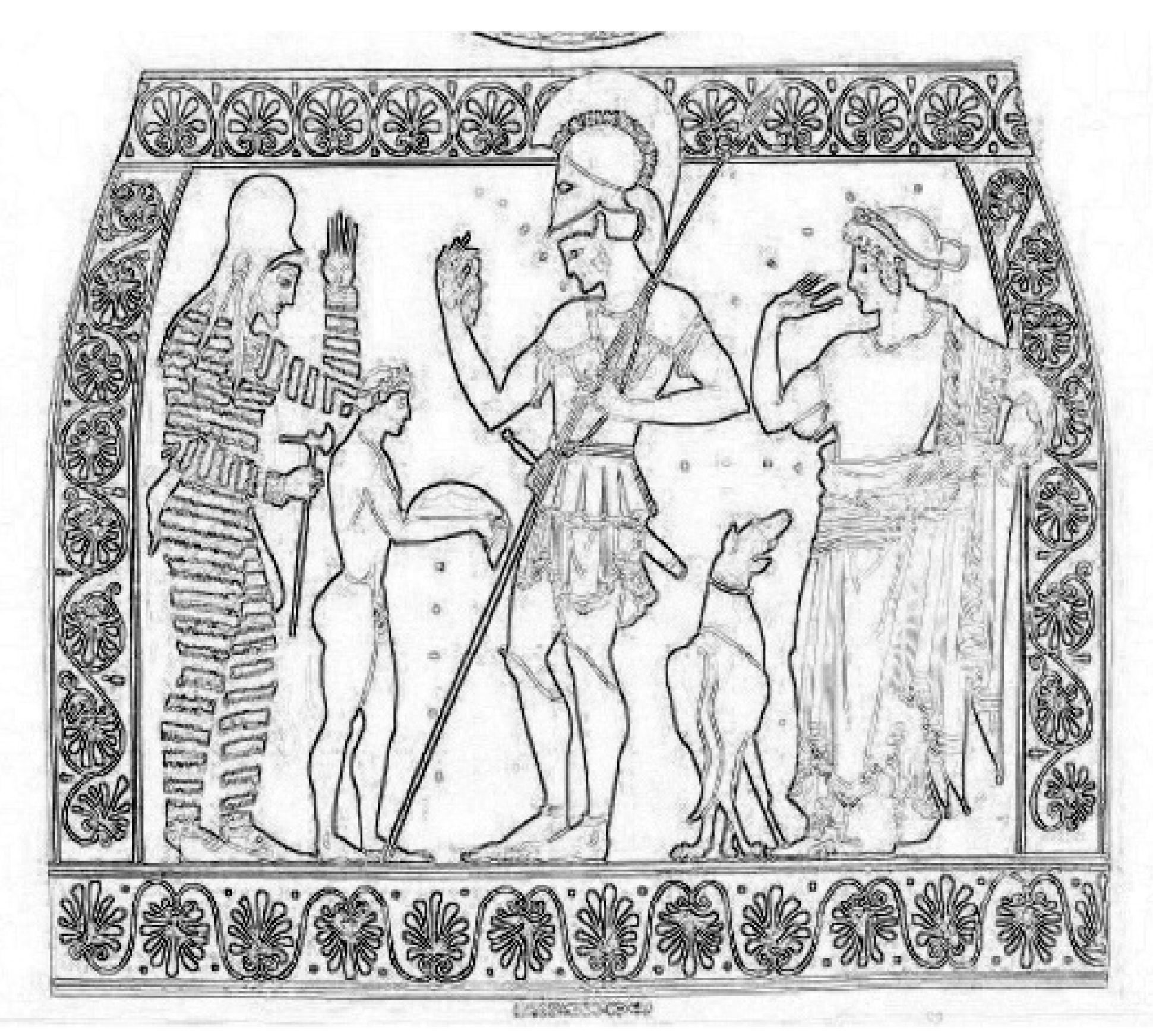

| 42 | Keller ([1909] 1913, 1.93) states that this engraving is “nach Roulez”, Moore (2008, fig. 14) shows this engraving and a comparandum by the Brygos Painter, fig. 15. I have been unable to find further information as to its current location as it does not seem to appear in the BAPD. Note the coins of Cyzicus, where a dog is curiously shown in the play position above a tuna fish. |

| 43 | Cf. (Pevnick 2014, fig. 4), where a solitary dog under the handle of a cup in the National Museum of Athens raises its paw as it defecates. Cf. also (Haworth 2018, pp. 18–19). The vignette of a defecating dog is not unheard of in fine art. D’Elia (2005), who was unaware of the Greek examples collected by Pevnick, discusses examples found in the art of Titian (Woodcut: “The Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea”), Dürer (woodcut: The Visitation), and Rembrandt (etching: The Good Samaritan Bringing a Wounded Man to an Inn”), among others. |

| 44 | The literature is vast, but the consensus of opinion and further bibliography can be found in (Coren 2000; Hare et al. 2002; Hare and Tomasello 2005; Johnston et al. 2016; Kaminski and Nitzschner 2013; Lakatos et al. 2012; Miklósi 2003). |

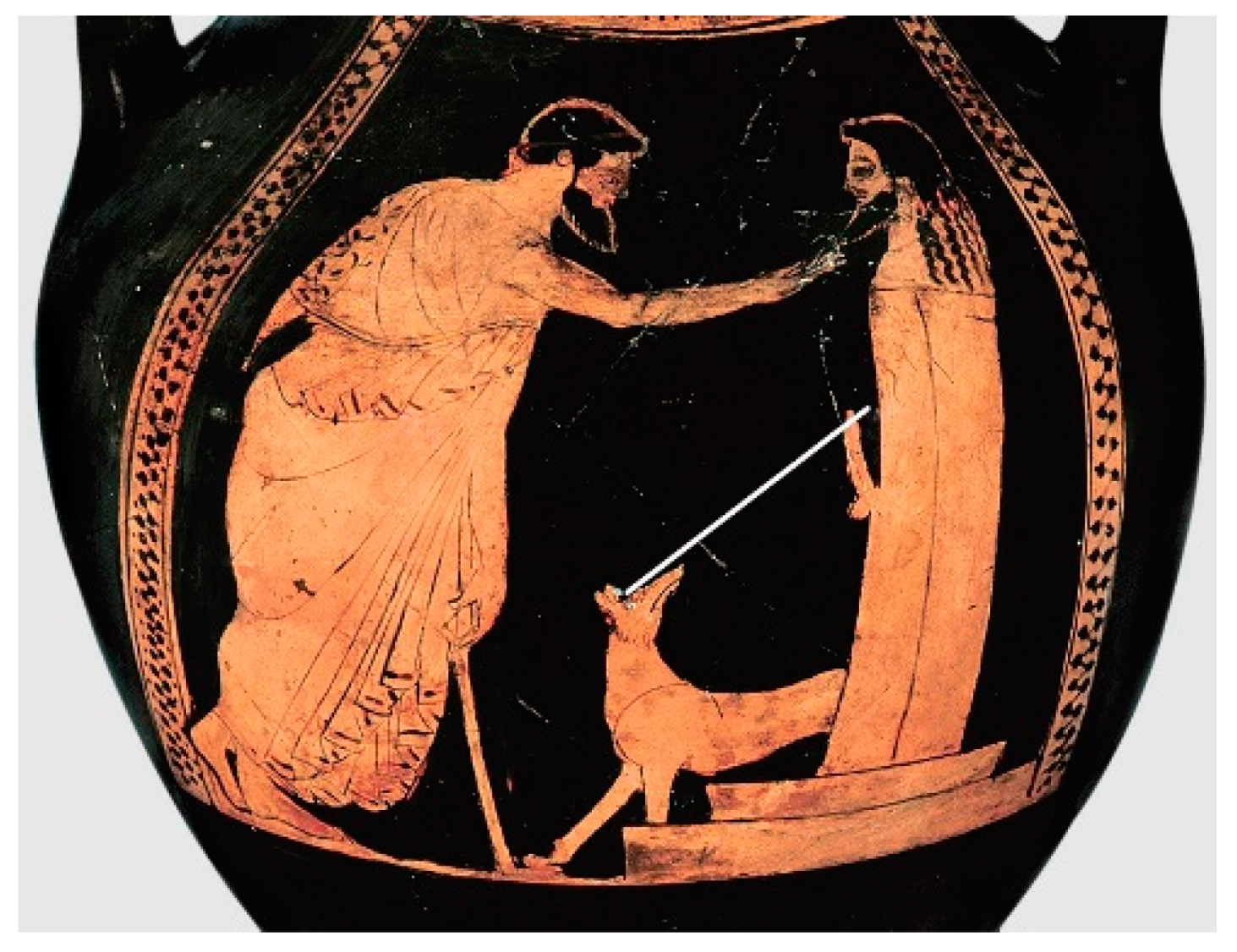

| 45 | The gesture is found as early as Homer’s Iliad 1.500–502 where Thetis beseeches Zeus to help Achilles (cf. Boegehold 1999, p. 19, figs. 9, 12). Its use in homoerotic scenes can be seen on Museo Gregoriano Etrusco Vaticano 17829, mentioned above (Dover 1989, ill. B76 and cf. B75), and vase illustrations in (Hubbard 2003, pp. 6, 12d). |

| 46 | The gesture appears on vases and stelae alike. Excellent examples of stelae can be found in (Ridgway 1971, figs. 1–3). Vases: Berkeley (CA), Phoebe Apperson Hearst Mus. of Anthropology, 8.921 (BAPD 203994); Rome, Accademia di Lincei, 2478 (BAPD 207462); Wurzburg, Universitat, Martin von Wagner Mus., 218 (BAPD 301643). The “farewell” gesture is also used between humans as in Figure 8, where the man reaches out to a young child, by whom a dog stands. That the dog’s gaze is fixed on the child, and may be licking his face, may be a clue as to which of the two humans has died. Ridgway’s copious notes list many comparanda. |

| 47 | E.g., ἀναβρυάζω, ἐγχρεμετίζω, ἐπιχρεμέθω, ὑποχρεμετίζω, φθέγγομαι, φρυάσσομαι/φρύθαγμα, χρεμετίζω, /χρεμετισμός. |

| 48 | |

| 49 | Cage: Gotha, Scholssmuseum, 48, Euphronius, 550–450 (BAPD 200100). Leash: Worcester (MA) Art Museum, 1936.148, Eretria Painter, 450–400 (BAPD 216970, leash not mentioned in Beazley, confirmed visually by author). Held by ears: New York, Metropolitan Museum GR575, Antiphon Painter, 500–450 (BAPD 203515); St. Petersburg, Heritage Museum (Canino Collection) B2009, Epidromos Painter, 525–475 (BAPD 200982); Hare by rear legs: Adria, Museo Archeolotico Nazionale, 22141, Foundry Painter, 500–450 (BAPD 204368); Rome, Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Matsch Painter, 500–450. Hare by front and rear legs and ears; Rome, Mus. Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia 50462, Kleophrades Painter, 500–450 (BAPD 202569), cf. (Manakidou 2015, pp. 130–31 with fig. 1a). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kitchell, K.F. Seeing the Dog: Naturalistic Canine Representations from Greek Art. Arts 2020, 9, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010014

Kitchell KF. Seeing the Dog: Naturalistic Canine Representations from Greek Art. Arts. 2020; 9(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitchell, Kenneth F. 2020. "Seeing the Dog: Naturalistic Canine Representations from Greek Art" Arts 9, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010014

APA StyleKitchell, K. F. (2020). Seeing the Dog: Naturalistic Canine Representations from Greek Art. Arts, 9(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010014