A Study on the Fixed-Point Adjustment Factor of Opposing Horizontal Strutsin Strutted Retaining Structures

Abstract

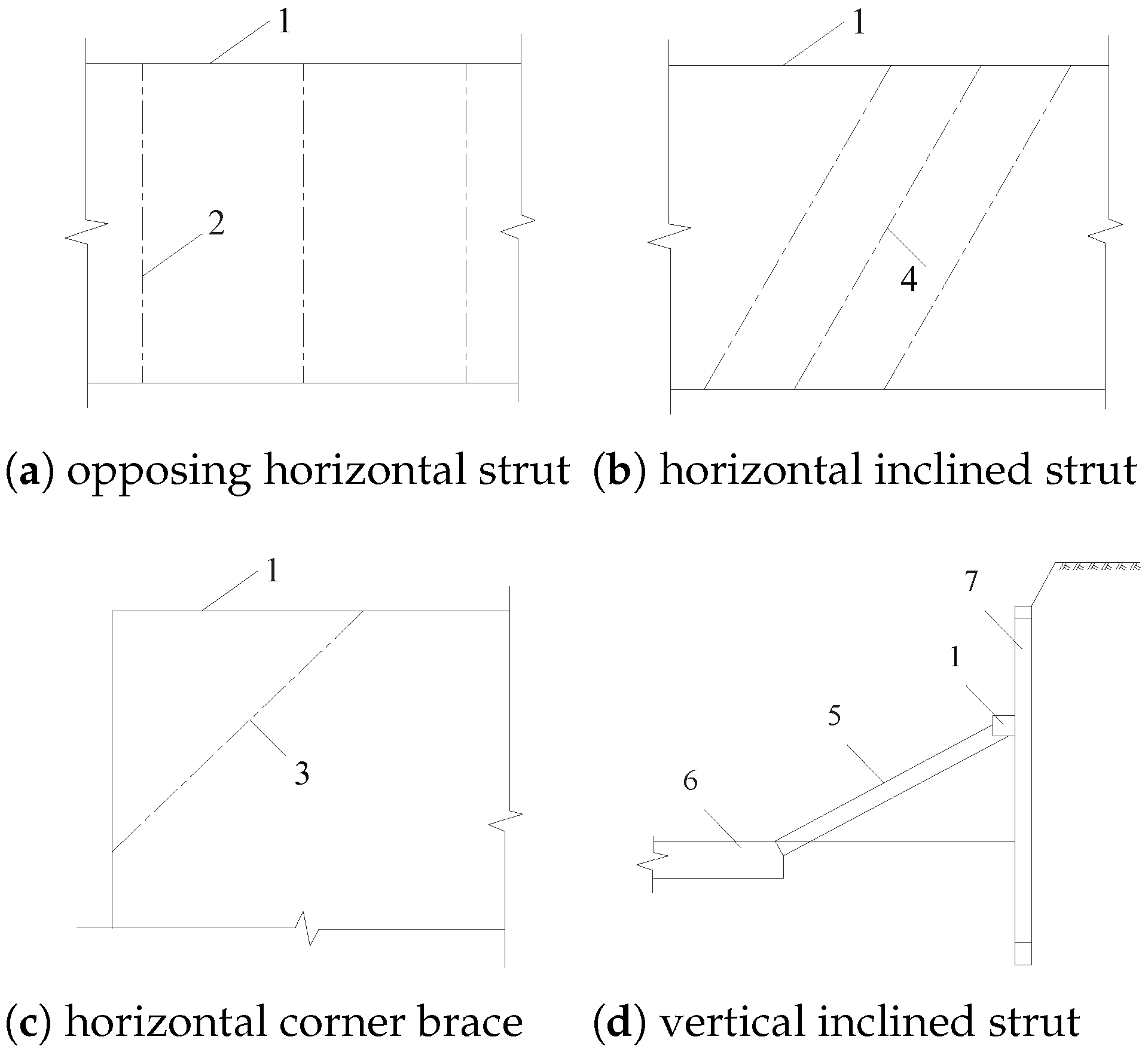

1. Introduction

1.1. The Problem of Under Asymmetric Loading

1.2. The Critical Research Gap: Severe Asymmetry and Evolving Strut Mechanisms

1.3. Research Objective and Contributions

- (1)

- To establish a clear earth pressure-based criterion for classifying the endpoint displacement of opposing horizontal struts into four distinct scenarios, covering the full spectrum from symmetry to severe asymmetry.

- (2)

- To elucidate the evolving support mechanism of the strut across these scenarios, clarifying its role when it ceases to function as a conventional elastic support.

- (3)

- To develop a unified analytical formula for calculating the fixed-point adjustment coefficient that is applicable to all four identified scenarios.

- (4)

- To validate the proposed method through comparative case studies against the published theoretical results and field monitoring data, demonstrating its generality and engineering reliability.

2. Problem Statement

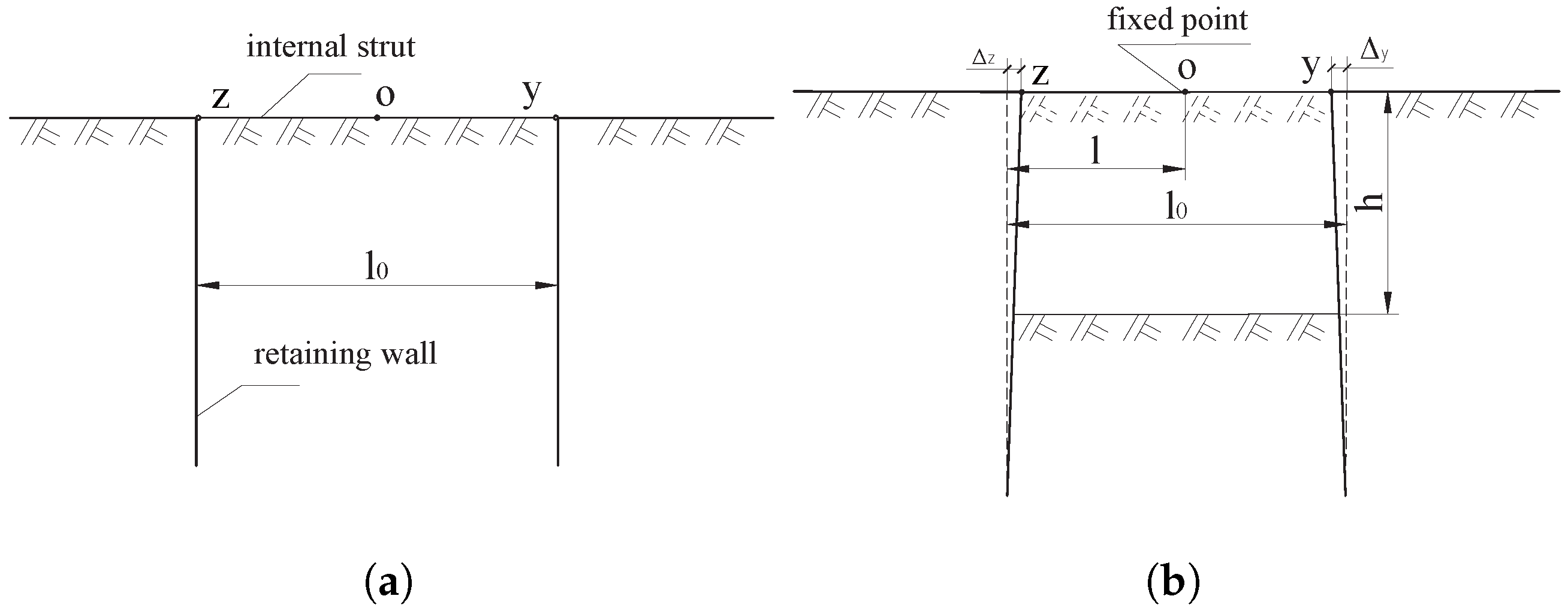

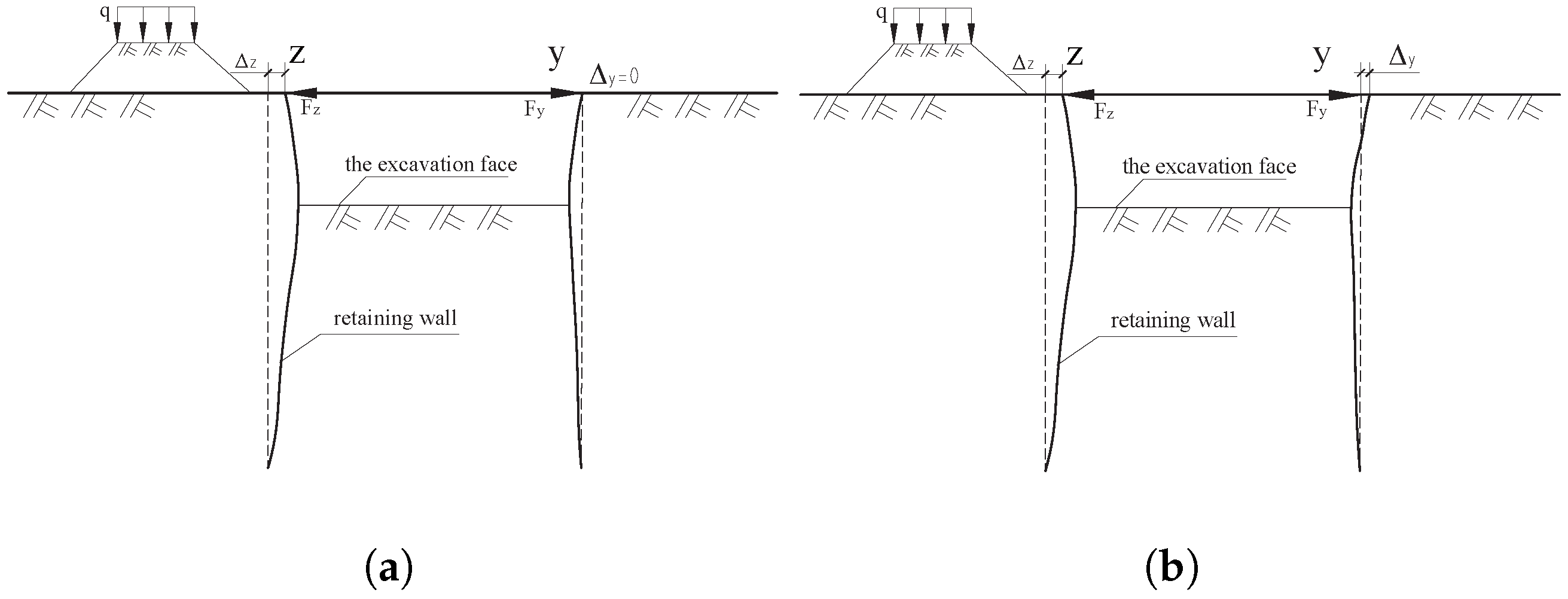

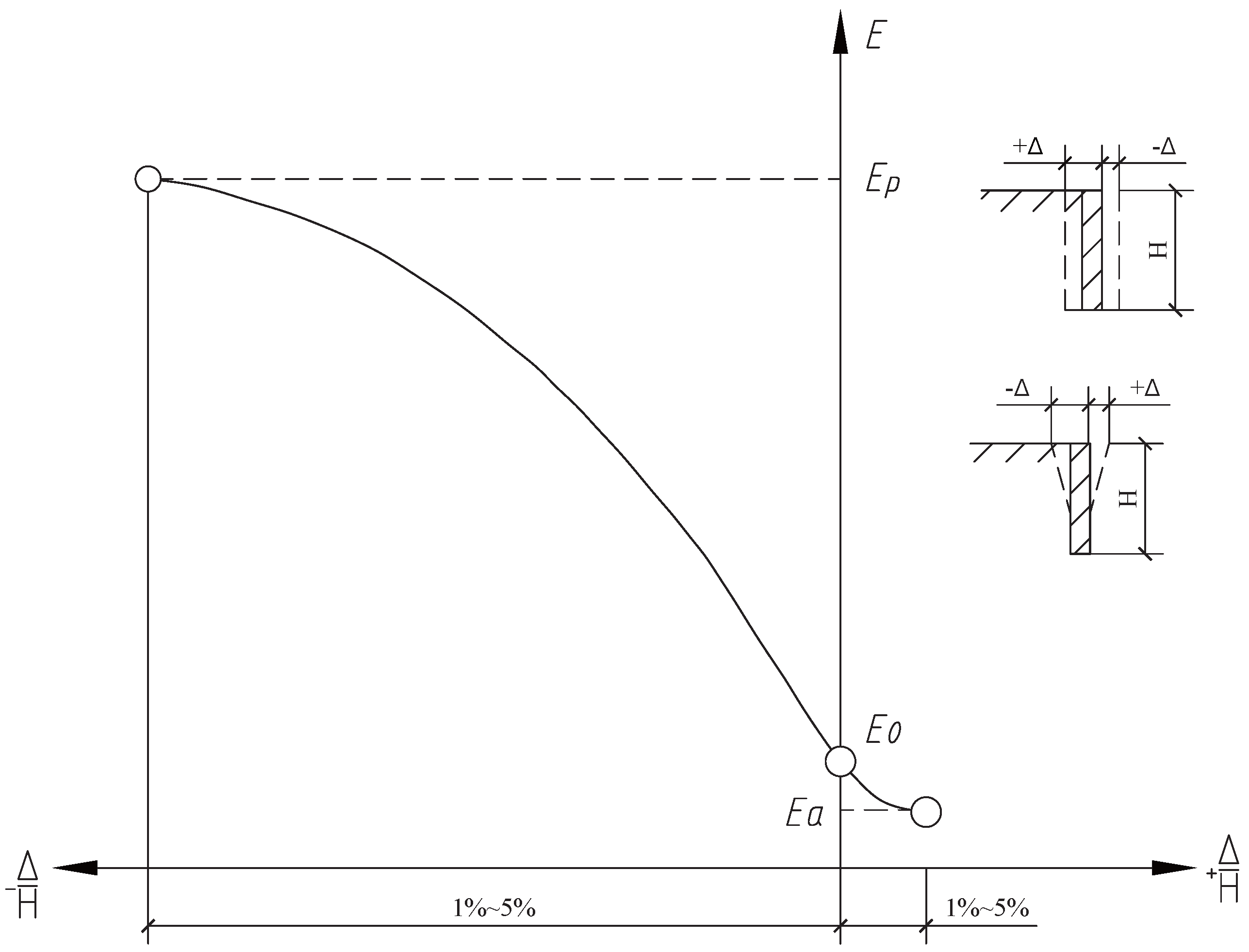

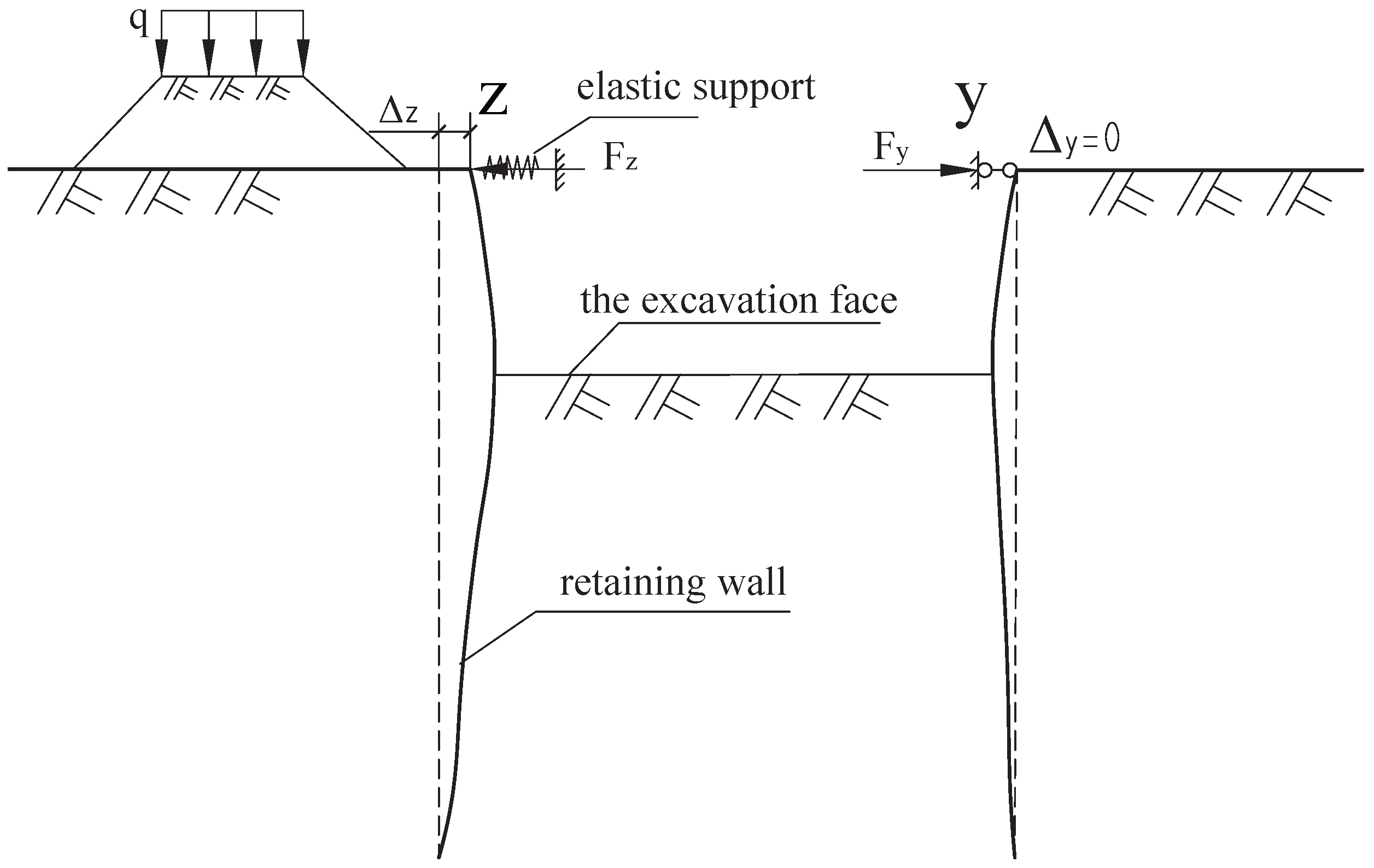

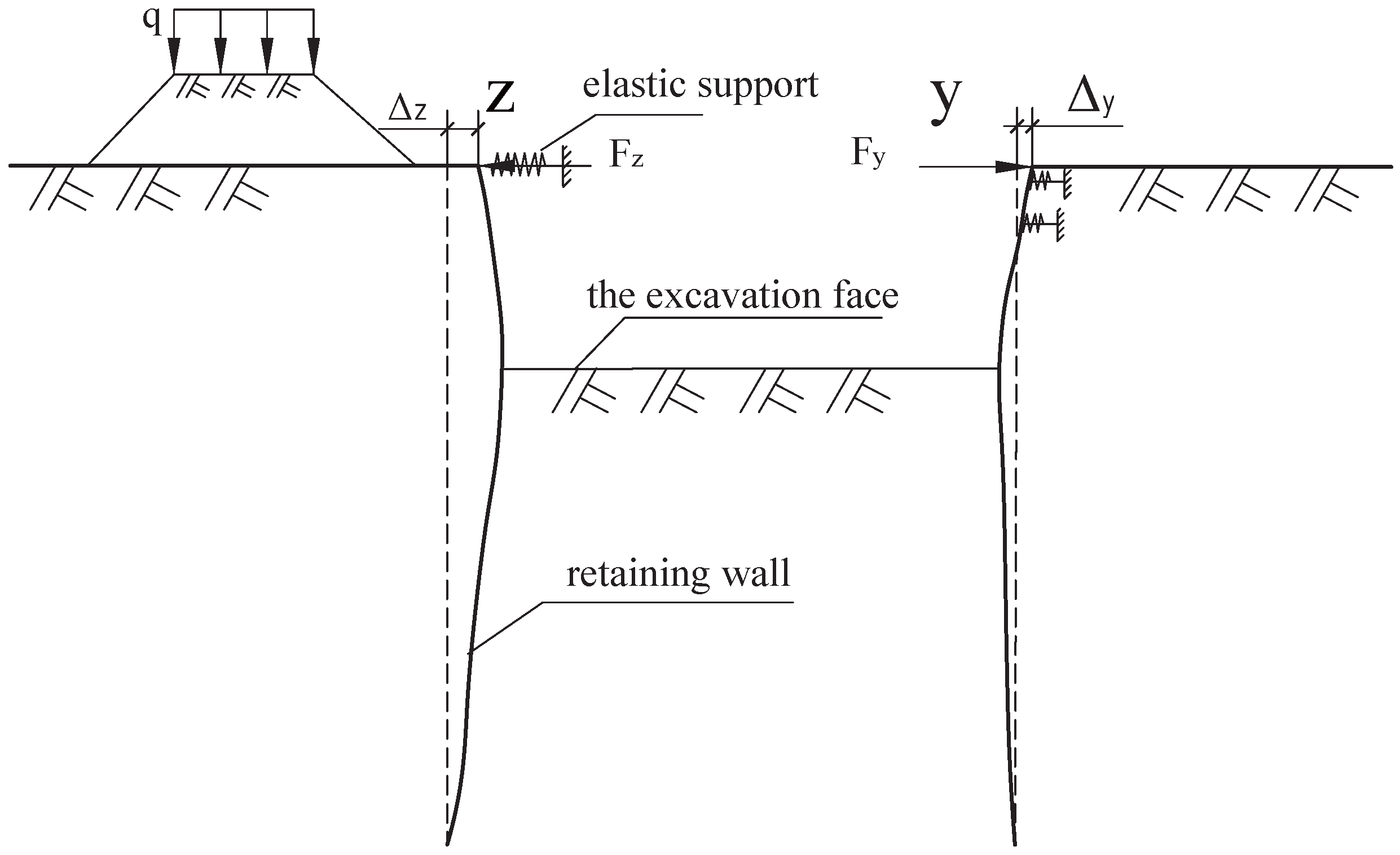

2.1. Definition of the Adjustment Coefficient for Fixed Points in Opposing Horizontal Struts

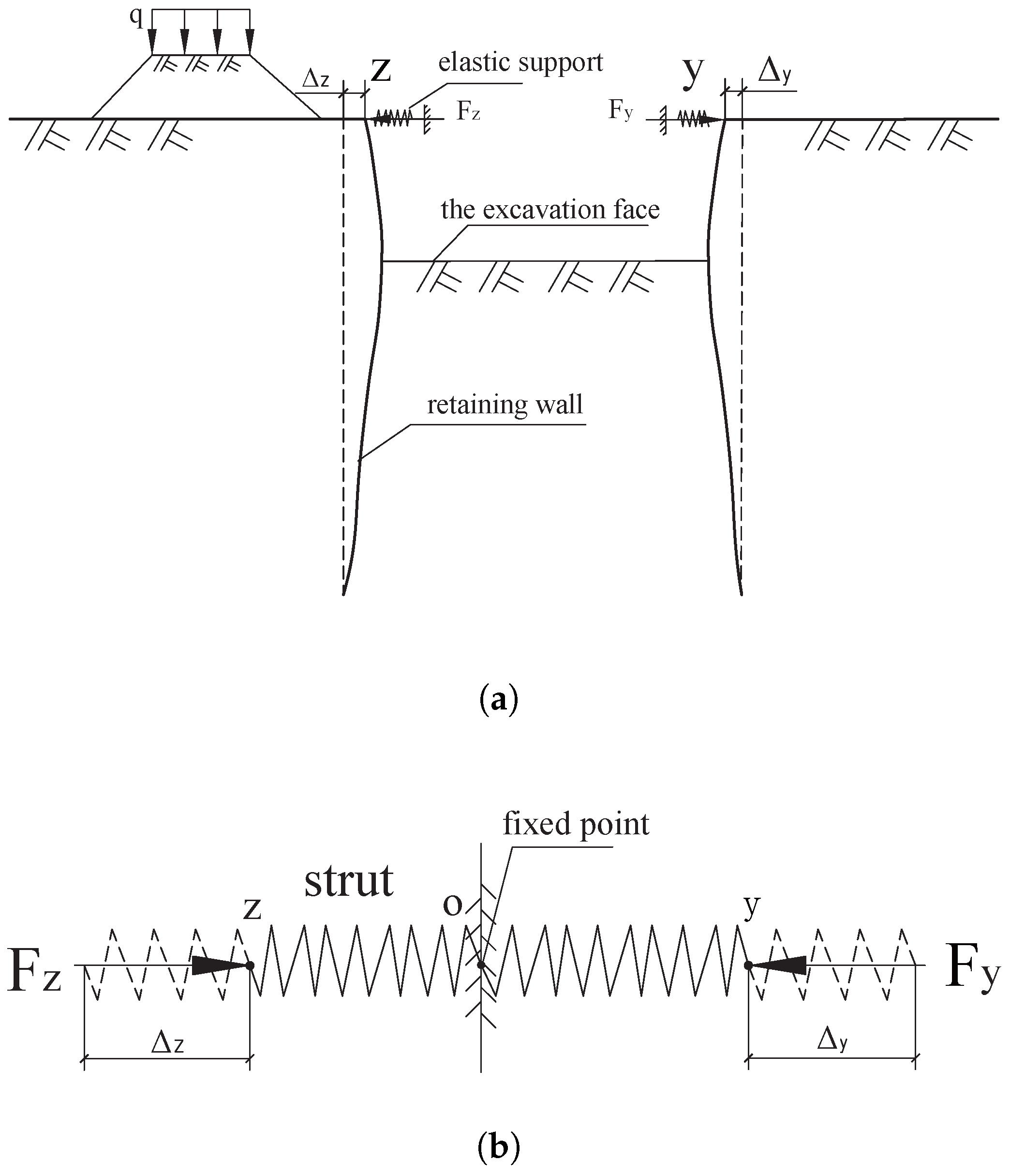

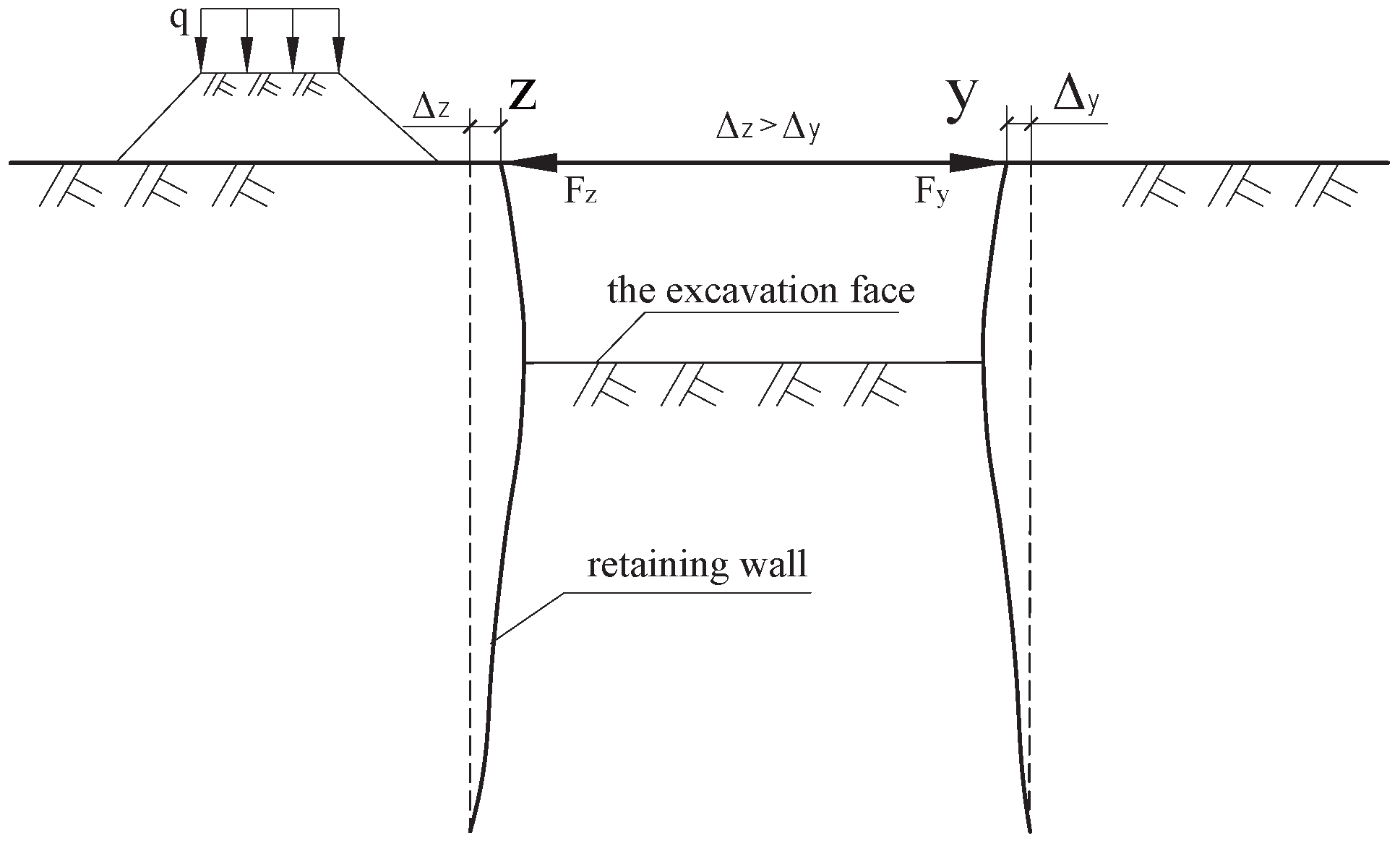

2.2. Analysis of the Support Mechanism of Opposing Horizontal Struts

2.3. Existing Issues in the Research on the Fixed-Point Adjustment Coefficient

2.3.1. Several Scenarios of Endpoint Displacement in Horizontal Cross Struts

2.3.2. Issues Associated with the Adjustment Coefficient for the Fixed Point

- (1)

- The primary issue is defining the displacement scenario of the strut endpoints. The displacement scenario is directly related to the degree of eccentric loading on the pit, which can be assessed by comparing the lateral earth pressures on opposite sides of the excavation. Therefore, comparing these lateral earth pressures presents a feasible methodology for determining the applicable displacement scenario.

- (2)

- Although the Specification and the existing literature [22,23,24,25] simplify the opposing horizontal strut in Scenarios 1 and 2 as elastic supports, providing their spring constraint stiffness on the retaining structures (Equations (1)–(3)), the mechanical mechanism of the strut in Scenarios 3 and 4 remains unclear, constituting a research gap.

- (3)

- Regarding the determination of the value, the Specification stipulates a value of 0.5 for both and in Scenario 1, which is widely accepted and applied [26,27,28]. For Scenario 2, only a value range is given without a specific calculation method, while Scenarios 3 and 4 are not addressed at all. Consequently, establishing a unified method for calculating the value applicable to all four scenarios is a crucial prerequisite for the scientific design of strutted retaining structures.

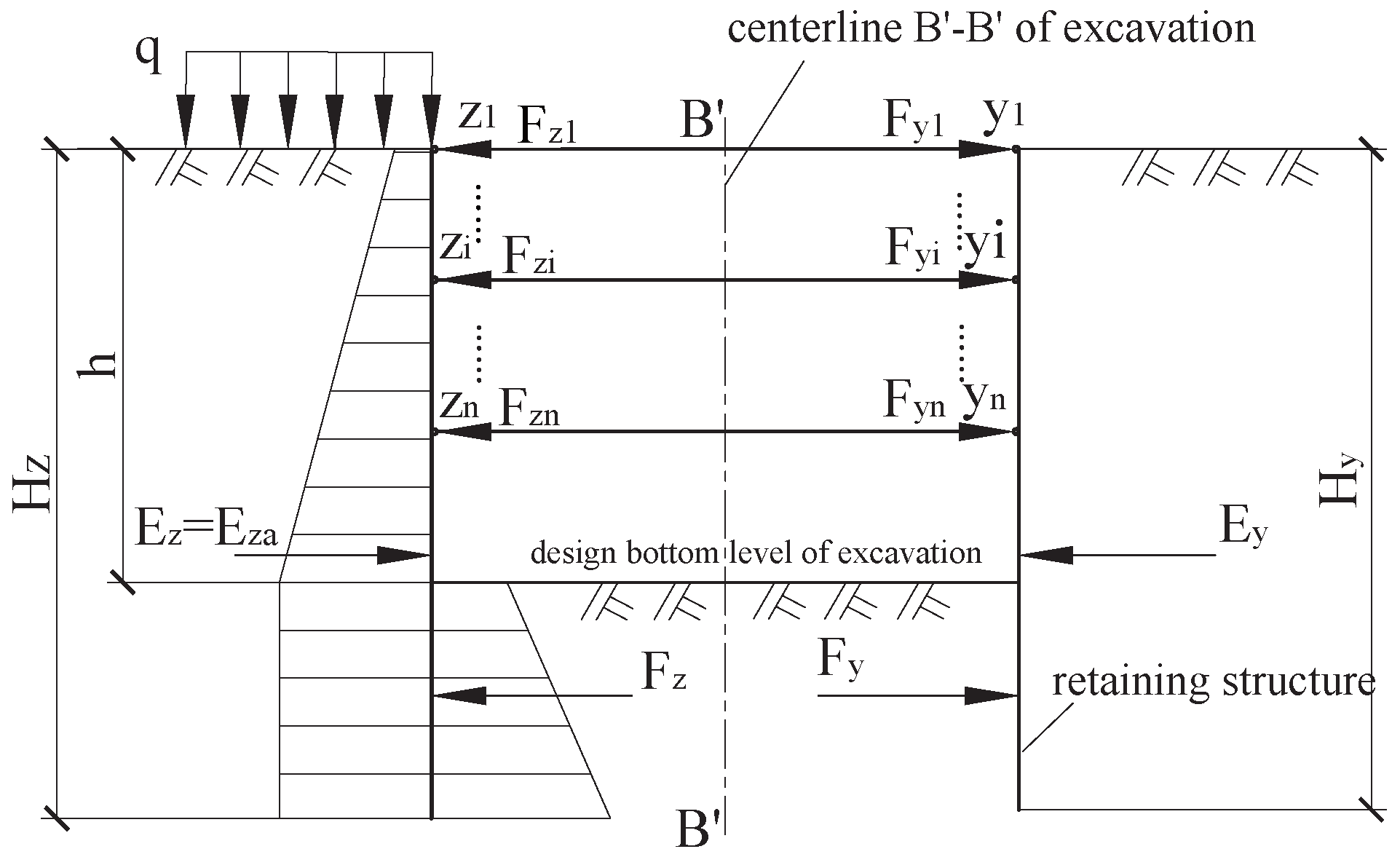

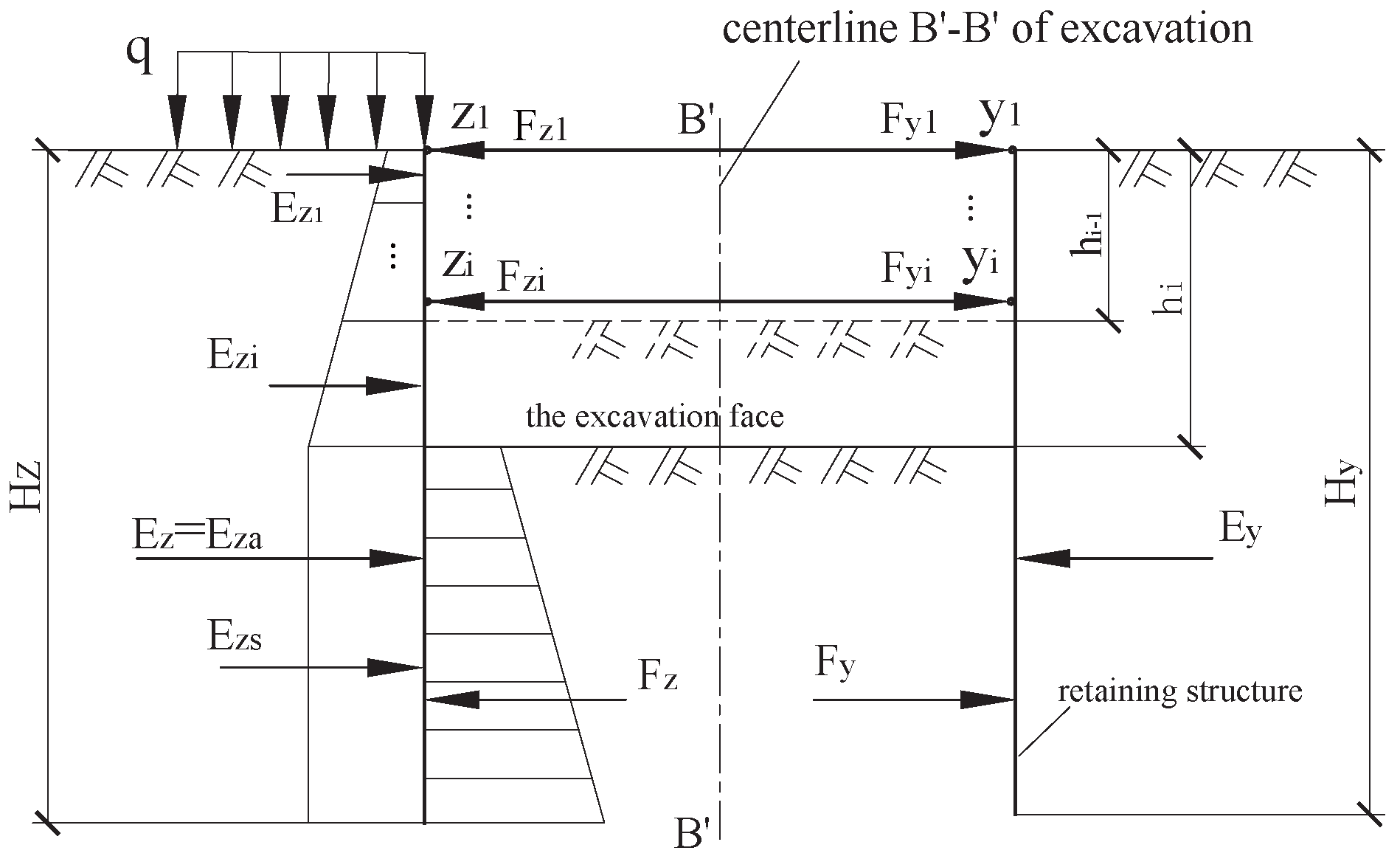

3. Mechanical Analysis of Strutted Retaining Structures in Foundation Excavations

3.1. Mechanical Assumptions for Strutted Retaining Structures in Foundation Excavations

3.2. Mechanical Analysis of the Retaining Structure During Construction

4. Study on the Fixed Points of Opposing Horizontal Struts

4.1. Determination of Endpoint Displacements for Opposing Horizontal Struts

4.1.1. Scenario 1

4.1.2. Scenario 2

4.1.3. Scenario 3

4.1.4. Scenario 4

4.1.5. Discussion

4.2. Support Mechanism and Fixed-Point Locations of Opposing Horizontal Struts

4.2.1. Scenarios 1 and 2

4.2.2. Scenario 3

4.2.3. Scenario 4

4.3. Calculation of the Fixed-Point Adjustment Coefficient for Opposed Horizontal Struts

5. Design and Application Examples of the Proposed Method

5.1. Design for Practical Application

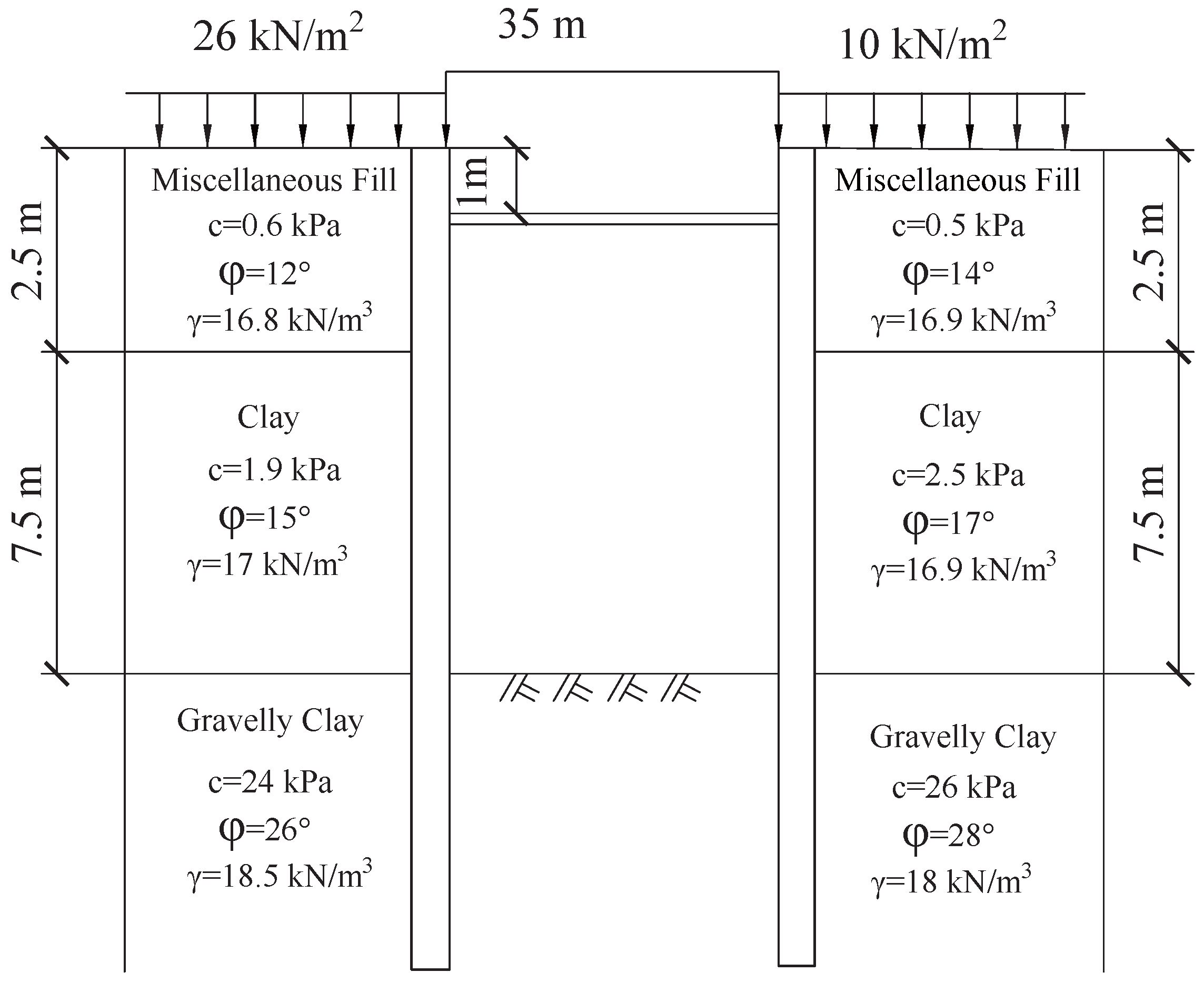

5.2. Case 1: Excavation with a Single Strut Layer

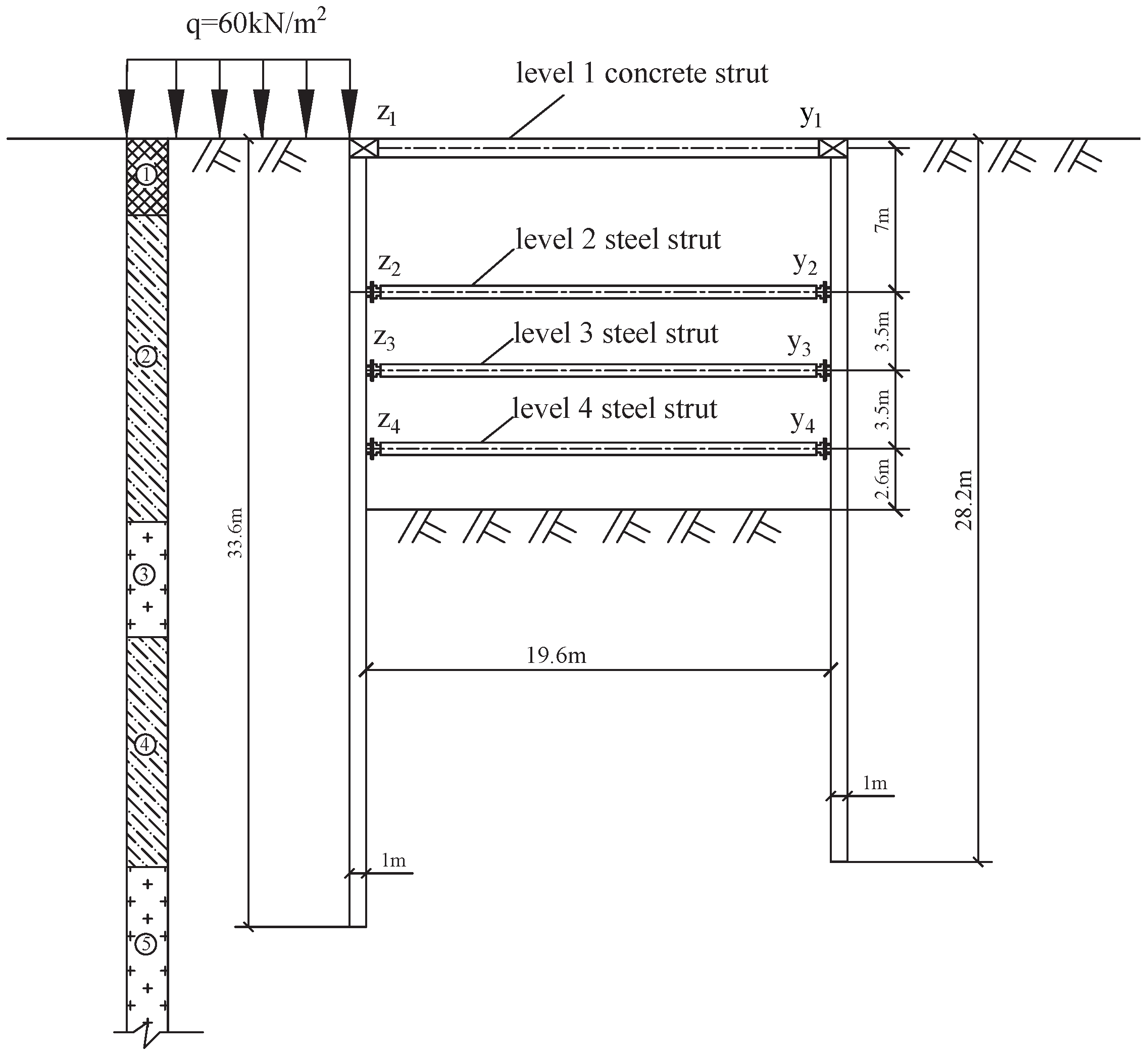

5.3. Example 2

6. Discussion

6.1. Innovation and Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Practical Implications and Advantages

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

6.4. Concluding Remarks

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Lu, J. Nonlinear soil spring model and parameters for calculating deformation of enclosure structure of foundation pits. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2020, 42, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Gendy, M.E. Analyzing laterally loaded piles in multi-layered cohesive soils: A hybrid beam on nonlinear Winkler foundation approach with case studies and parametric study. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, S.; Tang, H. Force Calculation of Mechanical Model of Pile-anchored Support Structure Based on Elastic Foundation Beam Method. Eur. J. Comput. Mech. 2023, 32, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yu, J.; Cao, X.; Shen, W. Study on Design Method of Pile Wall Combination Structure in a Deep Foundation Pit Considering Deformation Induced by Excavation. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 837950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liao, F.; Wang, L.; Lin, J.; Wang, J. Multi-Stage and Multi-Parameter Influence Analysis of Deep Foundation Pit Excavation on Surrounding Environment. Buildings 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhao, D.S.H.I.Z.; Lu, X.; Duan, X. Application of nonlinear soil resistance-pile lateral displacement curve based on Pasternak foundation model in foundation pit retaining piles. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Tang, S. Study on the horizontal coefficient of subgrade reaction for soft soil layers in Shanghai. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2004, 26, 495–499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Kang, A.; Xu, G.; Li, S. A method for calculating horizontal stiffness coefficient of ring supporting system for foundation pit. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. Discussion on equivalent elastic support stiffness of ring beam in circular foundation pit. J. Ground Improv. 2022, 4, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chen, F.; Jia, Y. Analysis on Influencing Factors for Computing the Equivalent Stiffness of the Interior Bracing of Deep Excavation by Numerical Method. Period. Ocean Univ. China 2009, 39, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ge, Y. Calculation Method of Retaining Piles with Annular Beams Elastic Support Stiffness Coefficient Forcircular Foundation Pit. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2017, 13, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- JGJ 120-2012; Technical Specification for Retaining and Protection of Building Foundation Excavations. Beijing COC Tech Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Ge, F.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Jin, Y.; Fu, X. Experimental Study on Stress and Deformation of Internal Support Structure under Asymmetric Load. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2024, 20, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Shi, Y.; Long, Z.; Ye, S. Stress and Deformation Analysis of Deep Foundation Pit Supported by Pile and Internal Bracing under Unsymmetrical Loaded. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 2952–2959. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Y. Theoretical Analysis of Displacement and Axial Force in Support Structures During Dynamic Adjustment of Internal Support Systems in Foundation Pits. Tunn. Constr. 2023, 43, 761–769. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Z.; Gao, F.; Gong, P.; Gong, Z.; Li, K. Stability of a Deep Foundation Pit with Hard Surrounding Rocks under Different in-Time Transverse Supporting Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, H.; Ni, P.; Zhao, C.; Guo, C.; Ma, H.; Dong, P.; Liang, H.; Tang, M. Model test and numerical simulation of a new prefabricated double-row piles retaining system in silty clay ground. Undergr. Space 2023, 13, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Xu, C.; Cai, Y. Research on characters of retaining structures for deep foundation pit excavation under unbalanced heaped load. Rock Soil Mech. 2010, 31, 2592–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, C. Characteristics of retaining structures of deep foundation pits under different excavation depths. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2010, 32, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Cheng, S.; Cai, Y.; Luo, Z. Deformation characteristic analysis of foundation pit under asymmetric excavation condition. Rock Soil Mech. 2014, 35, 1929–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xi, P.; Zhang, D. Numerical analysis of excavation effect of unsymmetrical loaded foundation pit with different excavation depths. J. Southeast Univ. Sci. Ed. 2016, 46, 853–859. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.B. A talk on application of incremental method in calculation of support structure of deep foundation. Undergr. Space 1999, 19, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.X. Application of incremental method in deep excavation enclosure structure horizontal displacement calculation. J. Ningbo Univ. (Nat. Sci. Eng. Ed.) 2011, 24, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.H. Practical calculation method of retaining structures for deep excavations and its application. Rock Soil Mech. 2004, 25, 1885–1902. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y.; Chen, S.Y. Improvement of incremental calculation method of retaining structure for foundation pit. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Feng, Y.Q.; Wang, R.X. Analysis of Flexible Retaining Structure of Deep Excavation and Its Comparison with Observed Results. J. Build. Struct. 1999, 20, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.W.; Shi, Z.Y.; Yi, D.Q.; Wu, S.M. Moment and Deformation Analysis of Retaining Structure of Foundation Pit in Whole Process of Construction. J. Build. Struct. 1998, 19, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.H.; Qian, F.; Cai, J.P. Research on a Calculation Method for the Horizontal Displacement of the Retaining Structure of Deep Foundation Pits. Buildings 2024, 14, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.B.; Yu, P.; Ge, F.; Fu, X.D. Incremental iterative calculation method for stress and deformation of retaining structures under asymmetric excavation. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.B.; Ying, Y.; Hu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fang, H.J.; Zhu, H.D.; Hu, M.Y. In situ axial loading tests on H-shaped steel strut with double splay supports. Proc. ICE Geotech. Eng. 2024, 177, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y.; Zhang, M.J.; Wu, L.W. An effective stiffness calculation method of the inner-bracing in the system of diaphragm walls. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 2024, 50, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, P.Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Teng, H.-B.; Chen, B.; Tao, X.-L. Compatibility of deformation and spatial effects for retaining pile, crown beam and braces under complex retaining conditions of deep foundation pit. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 2592–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.B.; Liu, D. Analytical methods for horizontal stiffness coefficient at pivots of inner support structures in deep foundation pits. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 41, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, J.; Bai, W.; Zhang, X. Analysis of field testing for deformation and internal force of unsymmetrical loaded foundation PIT’s enclosure structure close to railway. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2011, 30, 826–833. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Li, Z.; Fu, X. Calculation Method of Inner Support Fixed Point Adjustment Coefficient of Asymmetric Load Foundation Pit. Fly Ash Compr. Util. 2020, 34, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.B.; Wang, W.D. Foundation Ditch Engineering Handbook; Version 2; China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.S.; Lin, L.X. Measurement and analysis on supporting axial force in deep foundation pit. Build. Struct. 2012, 42, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.J.; Yao, X.B.; Hu, J. Monitoring and numerical simulation of axial forces of struts for foundation pit of a metro transfer station. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2014, 36, 455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Z.C.; Huang, J.F.; He, Y.J.; Ning, M.-Q. The active earth pressure calculation for retaining structure of deep foundation pit adjacent to river based on upper bound analysis. Eng. Mech. 2022, 39, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.X.; Jin, L.Z. Study on non-limit active earth pressure of finite soil under T mode. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 531, 2041–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C.; Yan, E.C.; Lu, W.B.; Cong, L.; Zhu, C.J.; Li, X.M.; Ye, S.W. Analytical solution of active earth pressure for cohesionless soils. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 2513–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Liu, K.; Zhu, X.; Tong, X.; Zhou, X. Active earth pressure against rigid retaining walls for finite soils in sloping condition considering shear stress and soil arching effect. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 14, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.X.; Zhang, B.Y.; Yu, Y.Z. Soil Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.B.; Liu, D. Analytical solution calculation method research of pivot horizontal stiffness coefficient of inner support structure in deep foundation pit. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 41, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, S.; Jin, Y.B.; Xu, J.X.; Sun, Y. A calculation method of single-layer opposite bracing foundation pit under asymmetric load. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.B.; Liu, D.; Sun, Y. Design and Calculation Method of Inner Support Structure in Deep Foundation Pit under Asymmetric Load. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2019, 15, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar]

| Feature | Case 1 (Example 1) | Case 2 (Example 2) | Significance for Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excavation depth | 10 m | 17.1 m | Tests the method across a spectrum of practical complexity |

| Retaining structure | Cast-in-place piles | Cast-in-place piles | |

| Support system | Single layer of strut | Four layers of struts | Validates calculations for multiple brace levels |

| Asymmetric surcharge | 26 vs. 10 kPa | 60 vs. 0 kPa | Tests the method’s core capability to handle eccentric loading |

| Validation approach | Comparison with other theoretical methods from the literature [40,41] | Comparison with field monitoring data via back-analysis | Validates findings in both theory and practice |

| Key validation metric | Calculation and verification of the single value | Calculation and verification of multiple values | Demonstrates reliability for both single and multiple calculation points |

| Calculation Method | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hinged (Ruan et al., 2022) [45] | 0.543 | 0.457 |

| Rigid (Ruan et al., 2022) [45] | 0.566 | 0.434 |

| The method by Jin (Jin et al., 2019) [46] | 0.733 | 0.267 |

| Formula (8) in the present study | 0.671 | 0.329 |

| No. | Name | Layer Thickness/m | /(kN/m3) | c/(kPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ➀ | Mixed fill soil | 3 | 18.8 | 30 | 1.0 |

| ➁ | Clay | 12 | 18.0 | 5.6 | 24 |

| ➂ | Fine sand | 4 | 19.0 | 31 | 1.0 |

| ➃ | Clay | 8 | 18.3 | 25 | 4.0 |

| ➄ | Fine sand | 8.5 | 19.0 | 30 | 1.0 |

| No. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3009.6 | 2368 | 1375.2 | 1.0 | |

| 2 | 1237.8 | 1305 | 887.4 | 0.920 | |

| 3 | 1668.9 | 1884.9 | 1318.5 | 0.809 | |

| 4 | 1048.8 | 1221.6 | 864.9 | 0.758 |

| No. | (mm) | (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.4 | 8.6 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | 19.1 | −3.2 | 0.857 | 7.4% | |

| 3 | 35.7 | −10.3 | 0.793 | 2.0% | |

| 4 | 50.5 | −18.9 | 0.723 | 4.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, B.; Zhu, J.; Cai, J.; Cai, Y.; Qiu, L. A Study on the Fixed-Point Adjustment Factor of Opposing Horizontal Strutsin Strutted Retaining Structures. Buildings 2026, 16, 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020450

Feng B, Zhu J, Cai J, Cai Y, Qiu L. A Study on the Fixed-Point Adjustment Factor of Opposing Horizontal Strutsin Strutted Retaining Structures. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):450. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020450

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Bo, Jianghong Zhu, Jianping Cai, Yue Cai, and Liang Qiu. 2026. "A Study on the Fixed-Point Adjustment Factor of Opposing Horizontal Strutsin Strutted Retaining Structures" Buildings 16, no. 2: 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020450

APA StyleFeng, B., Zhu, J., Cai, J., Cai, Y., & Qiu, L. (2026). A Study on the Fixed-Point Adjustment Factor of Opposing Horizontal Strutsin Strutted Retaining Structures. Buildings, 16(2), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020450