1. Introduction

With the rapid economic development and urbanization in China, the construction of urban rail transit systems has surged, leading to an increasing number of deep foundation pit projects in complex urban environments. In the current construction landscape, subway stations are often characterized as “long, large, and deep”. When these excavations traverse complex hydrogeological environments, particularly water-rich sand strata, the interaction between groundwater seepage and soil deformation poses significant threats to construction safety and surrounding infrastructure. Historical cases indicate that in such strata, hydraulic instability can rapidly lead to catastrophic failures, such as sand boiling, quicksand formation, and the sudden collapse of supporting structures, which account for over 30% of foundation pit accidents in water-rich regions. Therefore, strictly controlling settlement and understanding the deformation mechanism in such strata is critical [

1].

Over the years, extensive research has been conducted on the design and monitoring analysis of foundation pit excavations. Peck [

2] pioneered the theoretical analysis of settlement profiles, establishing a framework that is still widely used. Sugimoto et al. [

3] derived empirical formulas for predicting maximum surface settlement based on distance from the pit edge. Building on these classical theories, recent studies have increasingly combined field monitoring with numerical simulation to address complex geological conditions. Li et al., Wu et al., and Ye et al. [

4,

5,

6] utilized finite element methods (FEMs) to analyze horizontal displacement rules, generally finding that simulation trends coincide with measured data, though accuracy is often limited by environmental factors and spatiotemporal effects.

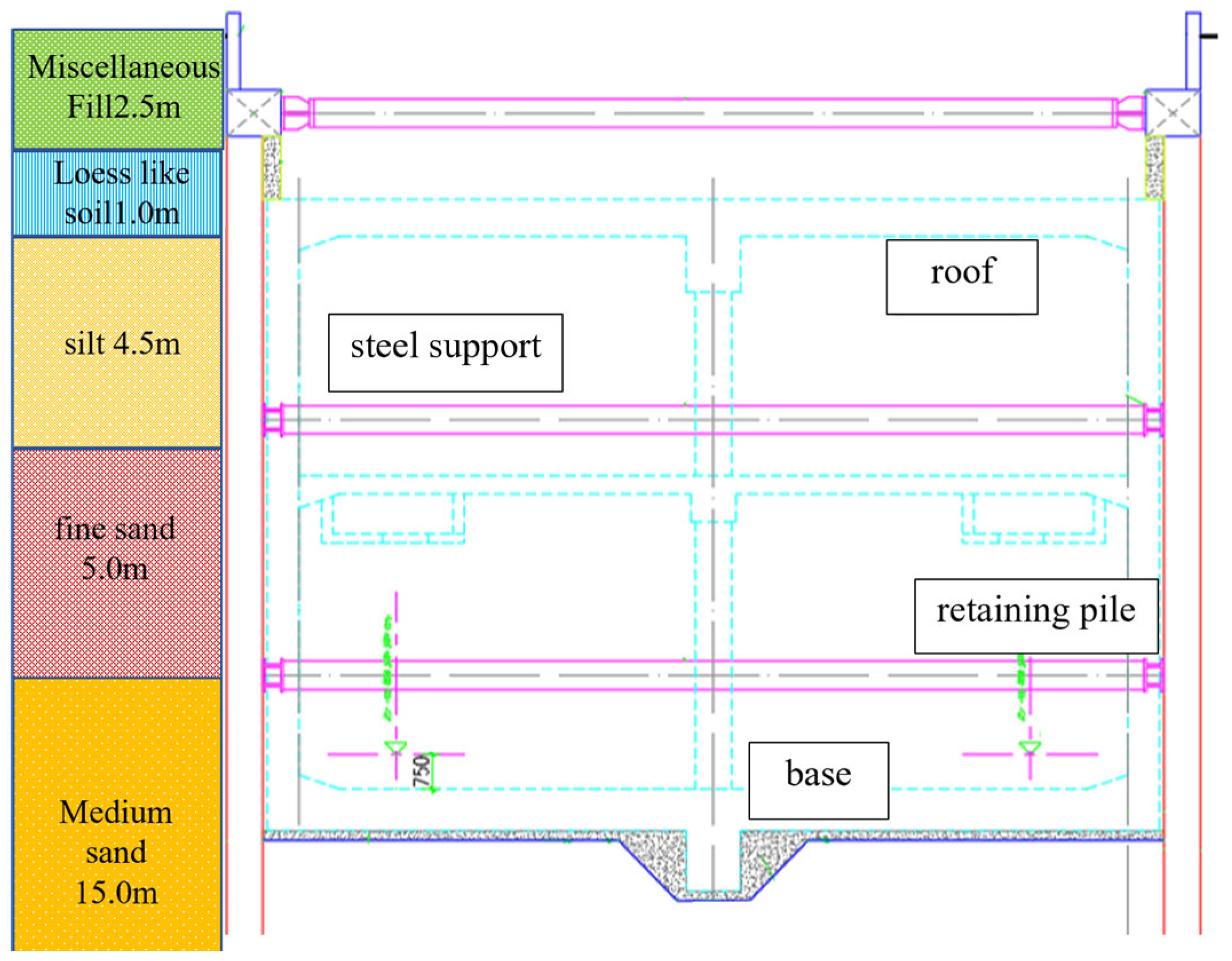

However, excavation in water-rich strata presents unique challenges compared to dry soils due to high permeability and fluid–solid coupling effects. In water-rich sand strata, the presence of groundwater significantly impacts the shear strength parameters of the soil. The lubrication effect of water reduces the inter-particle friction, and the generation of pore water pressure under dynamic construction disturbance reduces the effective stress. Consequently, this leads to a degradation in both the internal friction angle (φ) and cohesion (c), making the stratum more susceptible to deformation during excavation.

Recently, scholars have paid closer attention to the spatiotemporal evolution and hydraulic risks in these specific strata. For instance, Ren et al. [

7] analyzed the temporal and spatial evolution of earth pressure and settlement in water-rich sand layers, highlighting the sensitivity of sandy strata to construction disturbances. Similarly, Feng et al. [

8] investigated the excavation response of metro stations in water-bearing strata adjacent to tall buildings, emphasizing the impact of excavation on the surrounding environment. Regarding the specific risks induced by groundwater, Tian et al. [

9] combined on-site investigation with simulation to study leakage effects in water-rich strata, verifying that numerical methods can effectively capture the hydraulic response of underground structures. Furthermore, Xu et al. [

10] deepened the understanding of failure mechanisms by studying water and sand leakage using CFD-DEM coupling, revealing how seepage forces drive microscopic particle loss and macroscopic deformation.

Despite these advances, a significant gap remains in understanding the dynamic transition of deformation modes in water-rich sand foundation pits. Most existing numerical simulations assume ideal elastoplastic behavior and often fail to capture the “step-like” deformation pattern observed in practice, which typically results from the combined effect of rapid stress relaxation in cohesionless sand and the time lag in support installation. Standard simulations tend to predict a continuous “bulging” shape, leading to a discrepancy between design expectations and actual monitoring data.

To bridge this gap, this paper takes a subway station project in Xi’an Metro—located in a typical water-rich sand stratum—as a case study. Using the 3D finite element program Midas/GTS NX (2022), we established a dynamic excavation model to perform a comparative analysis with field monitoring data. Unlike previous studies that focus primarily on final deformation values, this research specifically investigates the spatiotemporal evolution mechanism that drives the enclosure structure from a “bulging” to a “step-like” profile. In this study, this ‘transition’ is quantitatively defined as the vertical migration of the point of maximum horizontal displacement (Hmax) from the deep soil depth (typical of the ‘bulging’ mode) to the very top of the pile (typical of the ‘step-like’ or ‘kick-out’ mode).

By elucidating the discrepancy between simulation and measurement, this study provides a theoretical basis for optimizing excavation sequences and support timing in similar high-permeability geological conditions.

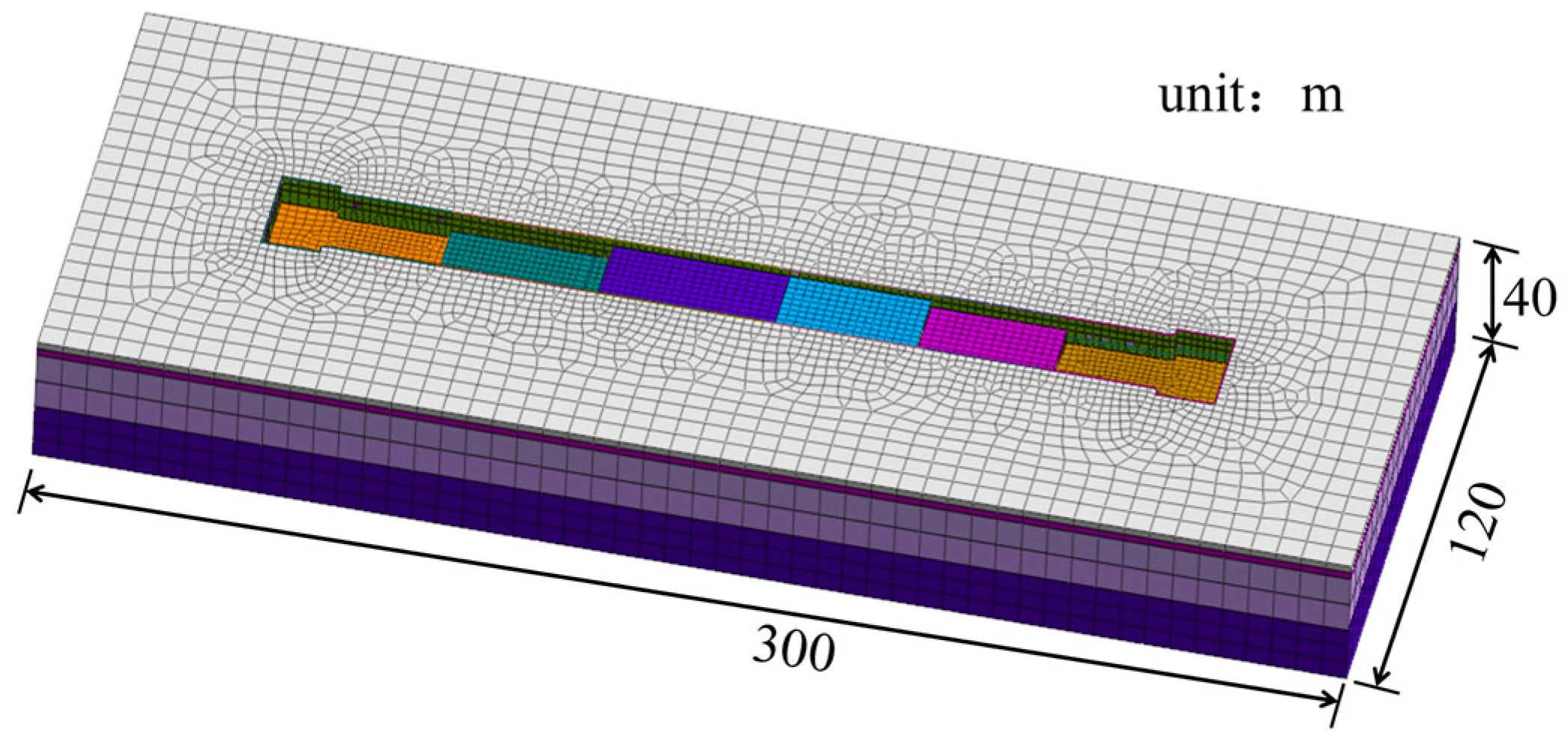

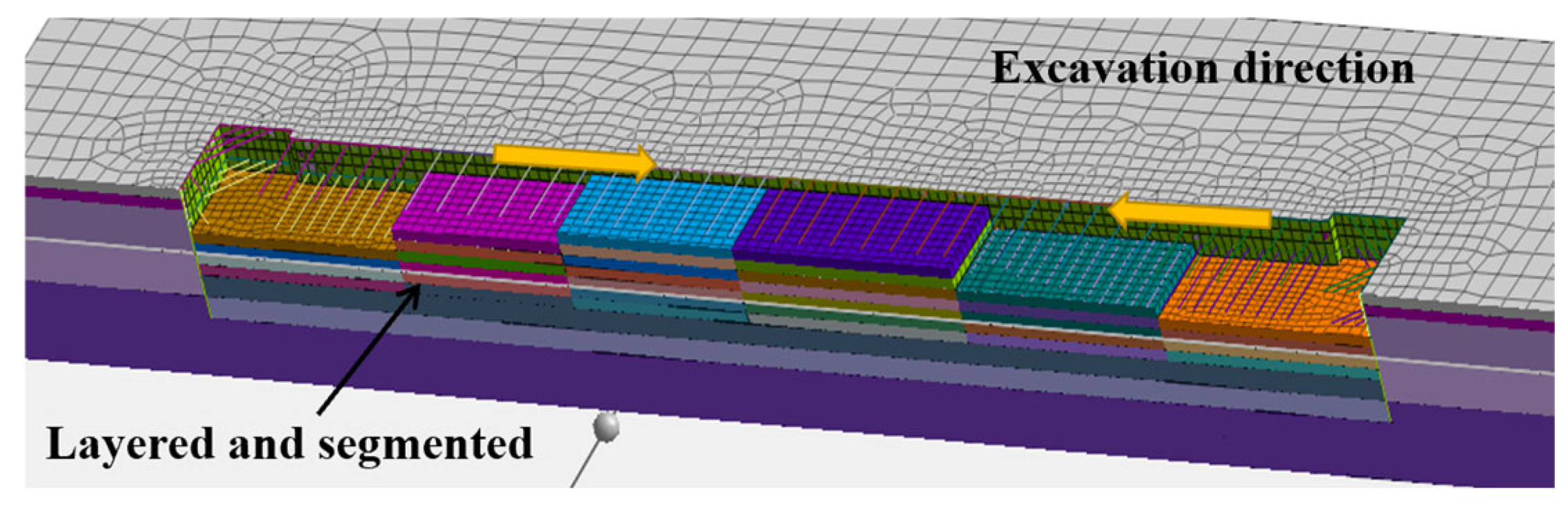

4. Numerical Simulation Results

In the process of pit excavation, the deformation of the enclosure structure and the surrounding ground surface is important and has guiding significance for engineering construction. The station pit to be excavated is long and narrow, and the construction excavation steps are complex and the scale of the project is large, so representative working conditions such as working condition 1 (the early stage of pit excavation, excavation on both sides of the pit), working condition 2 (the middle stage of pit excavation, continuous excavation to the middle and a certain digging depth), and working condition 3 (the end of pit excavation, excavation is completed to the basement) are selected to be analyzed in detail.

4.1. Analysis of Horizontal Displacement Results of the Enclosure Structure

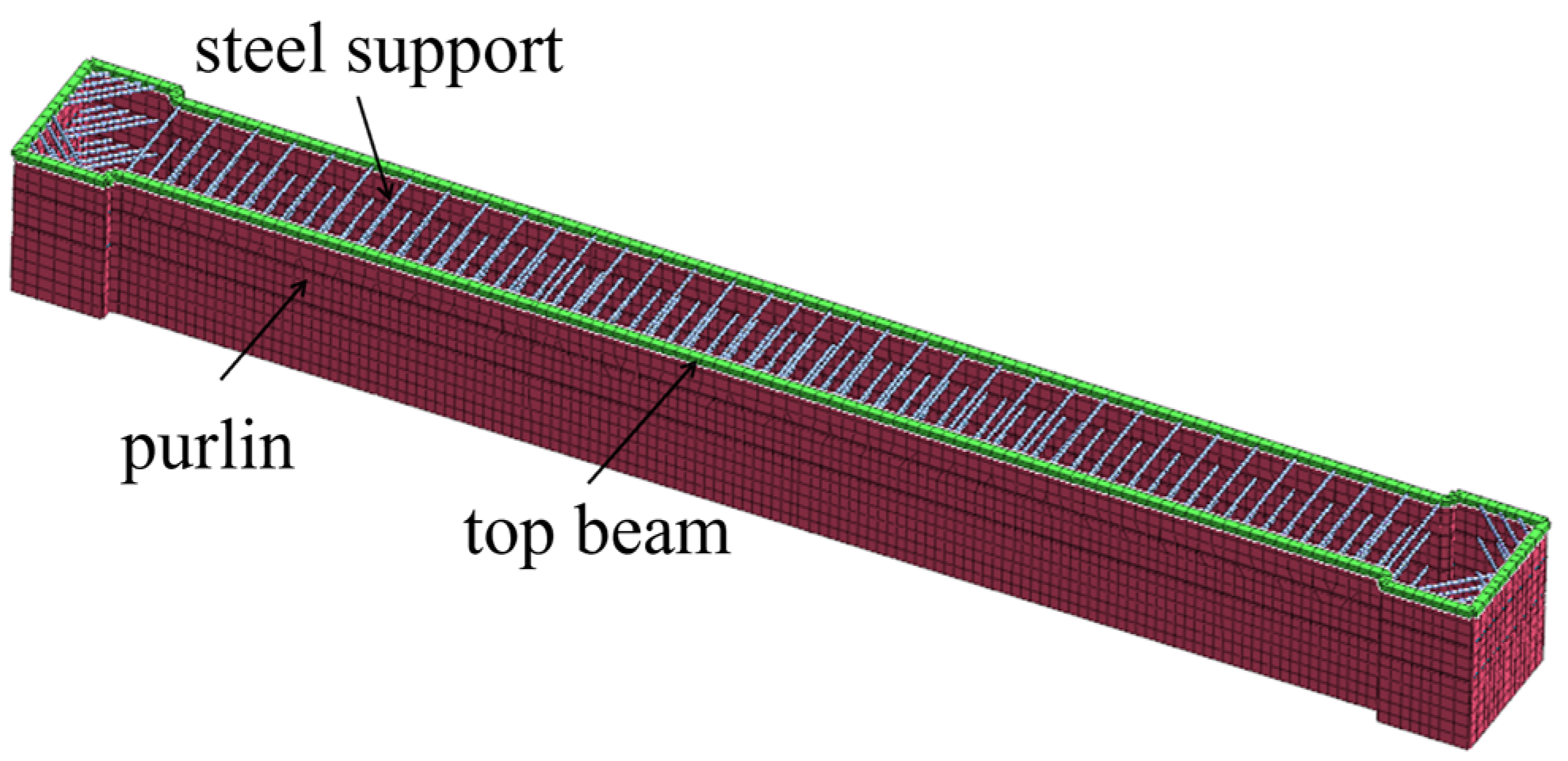

In order to effectively simulate the construction process of the shield structure passing through the high-speed railway, reasonable calculation assumptions are adopted:

Taking the envelope as a whole as the object of study,

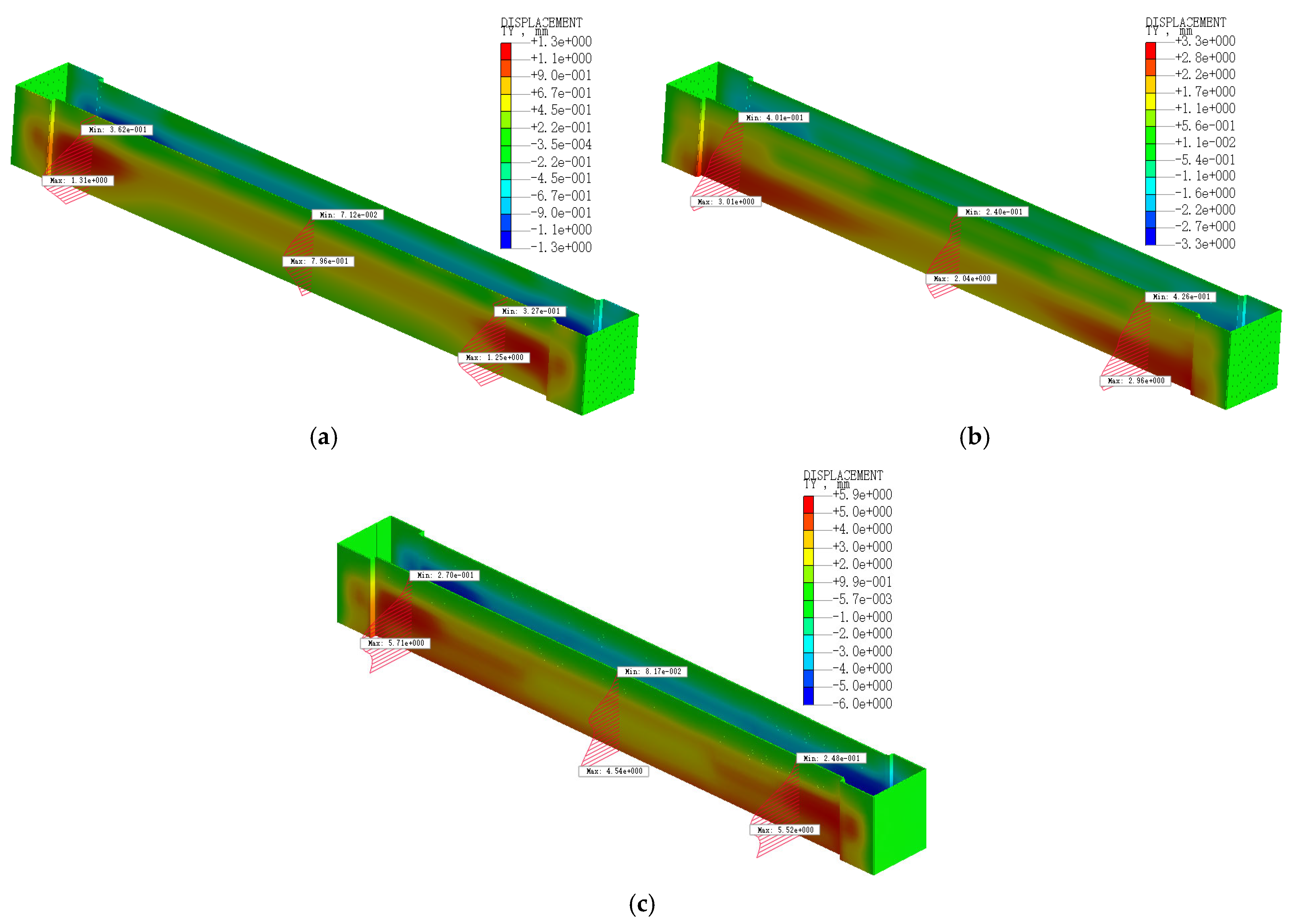

Figure 8 below shows the displacement cloud in the horizontal direction under working conditions 1 to 3.

As can be seen from

Figure 8, with the continuous excavation of the soil body, the horizontal displacement of the enclosure structure gradually increased from the initial 1 mm to about 6 mm, and, affected by the excavation sequence, the deformation was big at both ends and small in the middle, and lasted until the end of the excavation; at the same time, the implementation of the internal support erection made the location of the maximum horizontal displacement of the enclosure structure with the working conditions 1~3, from the pile head to the body of the pile gradually moved. When excavating to the bottom of the foundation pit, the maximum horizontal displacement is stably located in the middle of the pile, about 0.5–0.75 H of the foundation pit (H is the depth of excavation), and the maximum horizontal displacement is 6.00 mm. The lateral displacement pattern of the enclosure structure changes continuously [

15], and the overall deformation pattern evolves from a ‘bulging’ profile to a ‘step-like’ pattern. The deformation profile transitions continuously, shifting from a ‘bulging’ shape to a combined mode, and, finally, settling into a distinct ‘step-like’ configuration, and then to “stepped belly”, wherein the end side is subject to the local corner effect and the construction surface is long and the soil layer stress release is not synchronized, resulting in the enclosure structure lateral displacement in a certain depth range of the unsmooth decrease.

4.2. Surrounding Surface Settlement and Deformation Analysis

It is usually believed that the surface settlement around the foundation pit is influenced by a combination of factors such as lateral movement of the enclosing structure, consolidation of the soil outside the foundation pit, and soil uplift inside the foundation pit. Excessive surface settlement may cause uneven settlement of the surrounding building foundations or underground pipelines, leading to accidents such as cracking and pipeline breakage, which seriously affect their normal use and structural safety [

16].

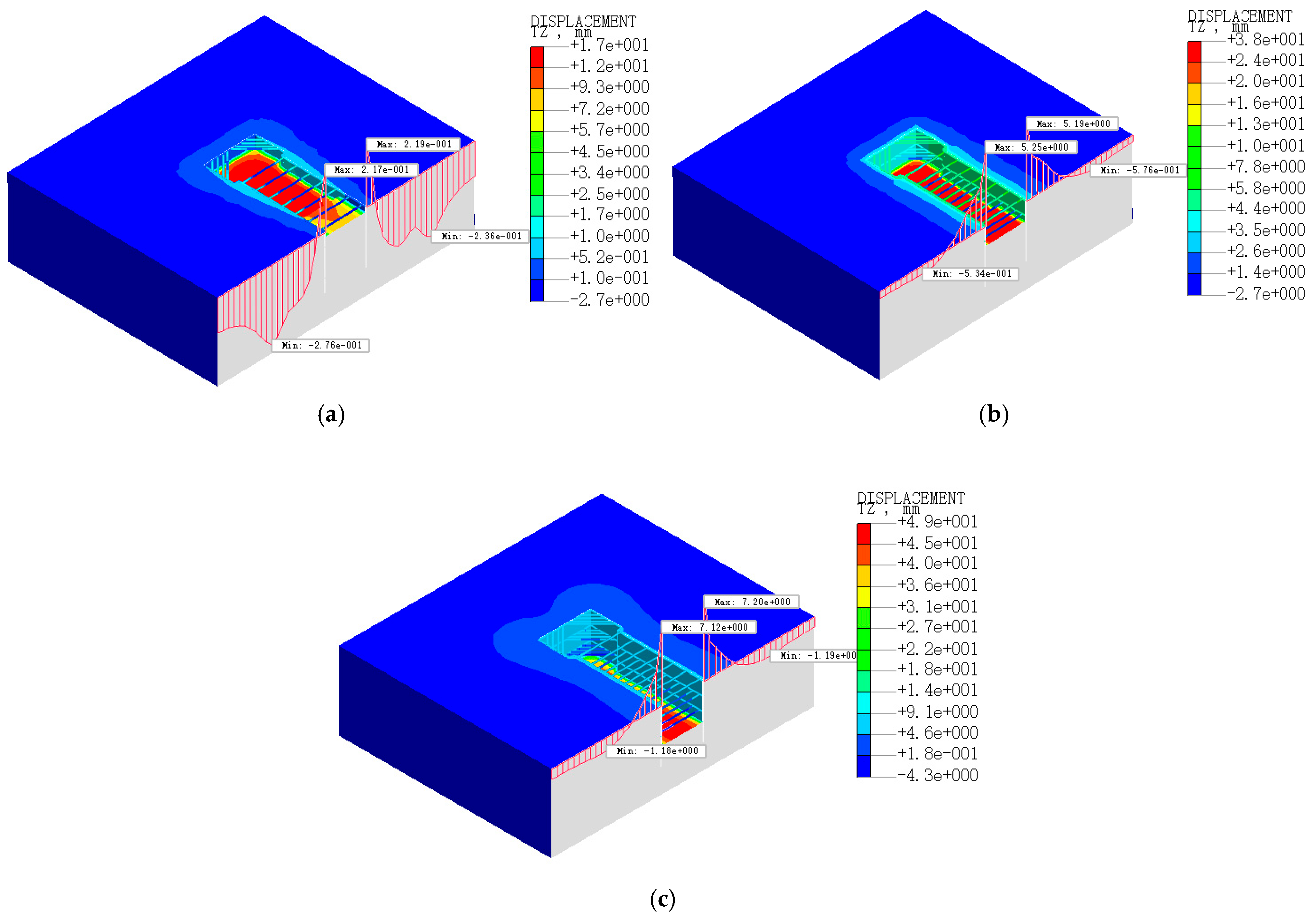

Figure 9 below shows the displacement cloud map carried out after excavation in the z-direction at the location of the model measurement point for working conditions 1 to 3.

It can be analyzed from

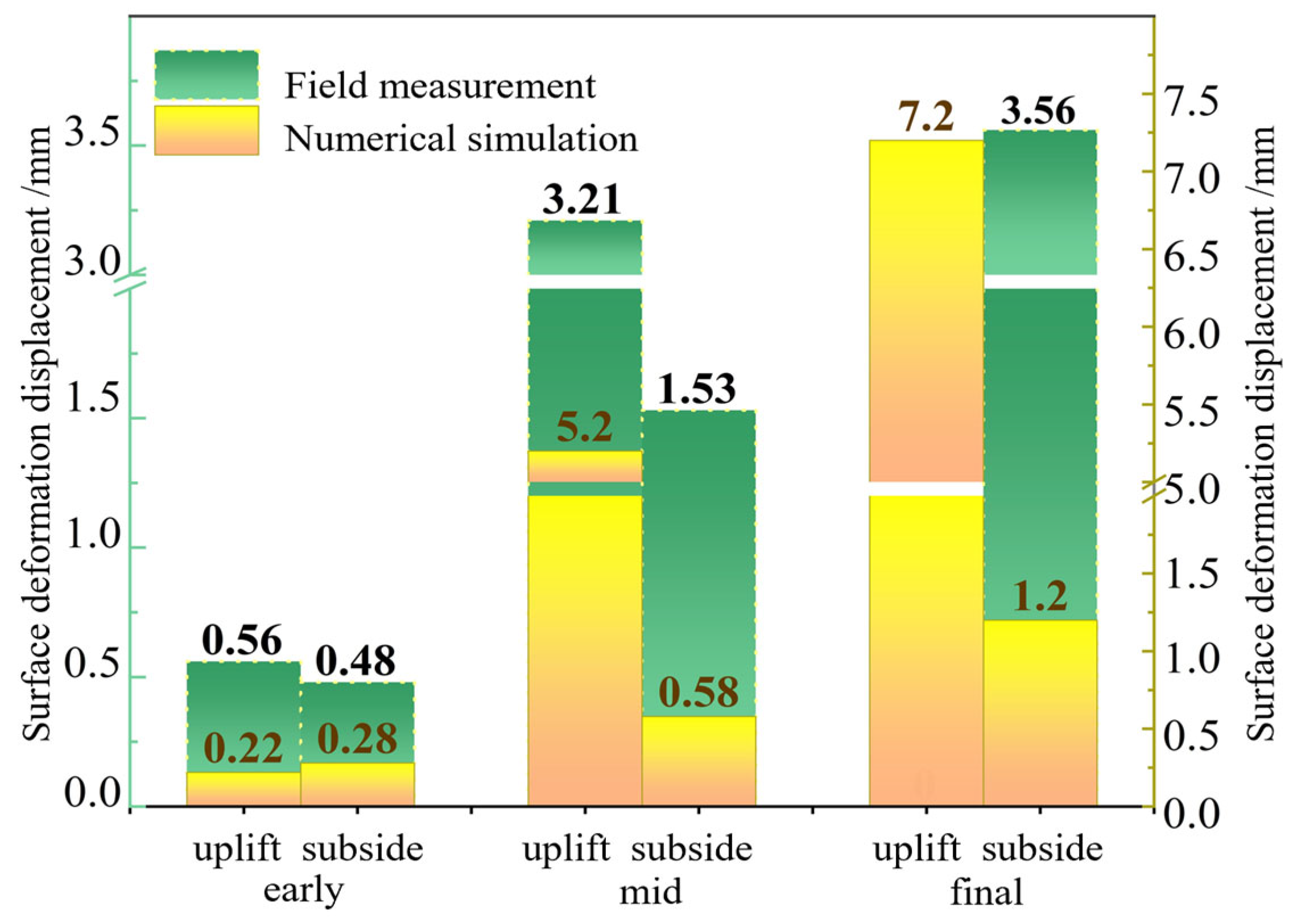

Figure 9 that the vertical deformation of the surrounding ground surface manifests as both heave and settlement, and these two conditions often exist simultaneously, according to the working conditions of the pit construction. From working conditions 1 to 3, the magnitudes of both surface settlement and heave increase progressively, and, when excavating to the bottom, the maximum settlement reaches 1.2 mm, and the starting point of the settlement is gradually moving outward from the edge of the pit, and, finally, tends to be stabilized. The main influence range of the settlement is in an area of about 15 m from the pit. The influence range of the surface heave is mainly concentrated at the edge of the pit, with the maximum heave occurring directly adjacent to the edge, and the maximum basal heave is straight to the edge. About 15 m from the foundation pit, the influence range of surface bulging deformation is mainly at the edge of the foundation pit, the maximum bulging is 7.2 mm, and the enclosure structure is subjected to an upward deformation trend by the action of the soil at the bottom of the foundation. Further, there is a trend of deformation to the outside of the foundation pit by the action of the supporting axial force; under the action of the two kinds of force at the same time, the enclosure structure takes the bottom of the pile foundation in the ground as the rotating center, and there is a trend of counterclockwise rotation, which leads to the upper part of the soil body to appear bulging deformation. The soil on the upper part of the enclosure will be bulged and deformed.

According to the Code for Monitoring Measurement of Urban Rail Transit Engineering GB 50911-2013 [

17], the widely accepted alert limit for surface settlement in this type of excavation is typically 0.2% to 0.3% of the excavation depth (approx. 30–40 mm for this project). The simulated maximum settlement (1.2 mm) and the field-measured maximum settlement (7.8 mm) are both well within the safety control standards, indicating that the overall stability of the foundation pit is effectively controlled.

5. Field Monitoring Results

According to the monitoring around the pit on site, the deformation of the enclosure structure and the deformation of the surface subsidence of the pit under different construction conditions were analyzed using the measured data. The monitoring data was obtained using manual measurements at set frequencies. The horizontal and vertical displacements of the pile tops were measured using a Leica high-precision Total Station (TS06) with prism targets. Surface settlement was monitored using a digital level (Leica DNA03) based on established control network points.

To ensure data integrity, a strict data quality control protocol was implemented. Singular outliers caused by non-structural factors (e.g., collision with construction machinery or optical obstruction) were identified and filtered using the 3σ criterion. No significant instrument failures occurred during the monitoring period; minor data gaps (less than 5% of the dataset) were filled using linear interpolation from adjacent temporal records.

5.1. Enclosure Deformation Analysis

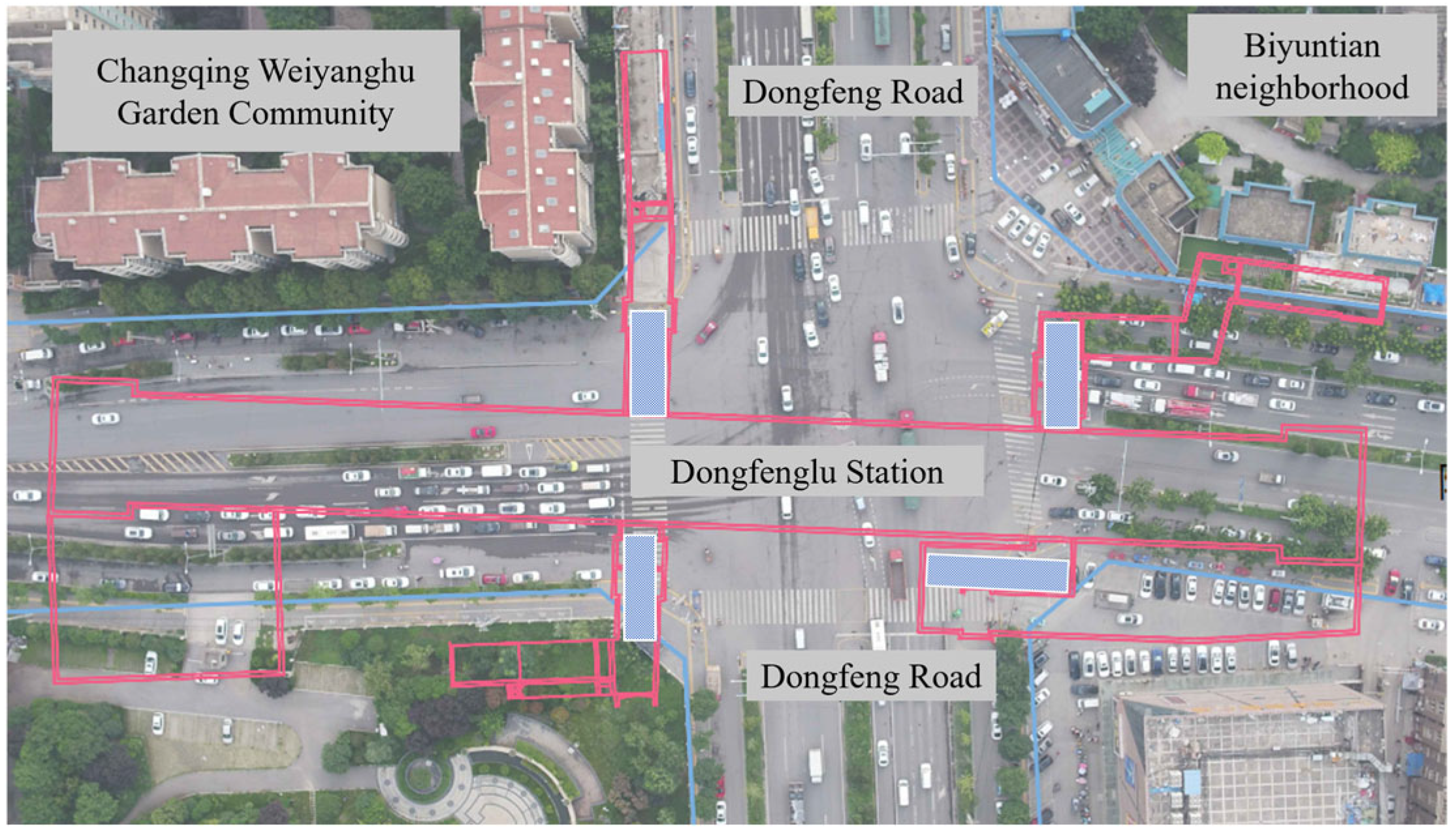

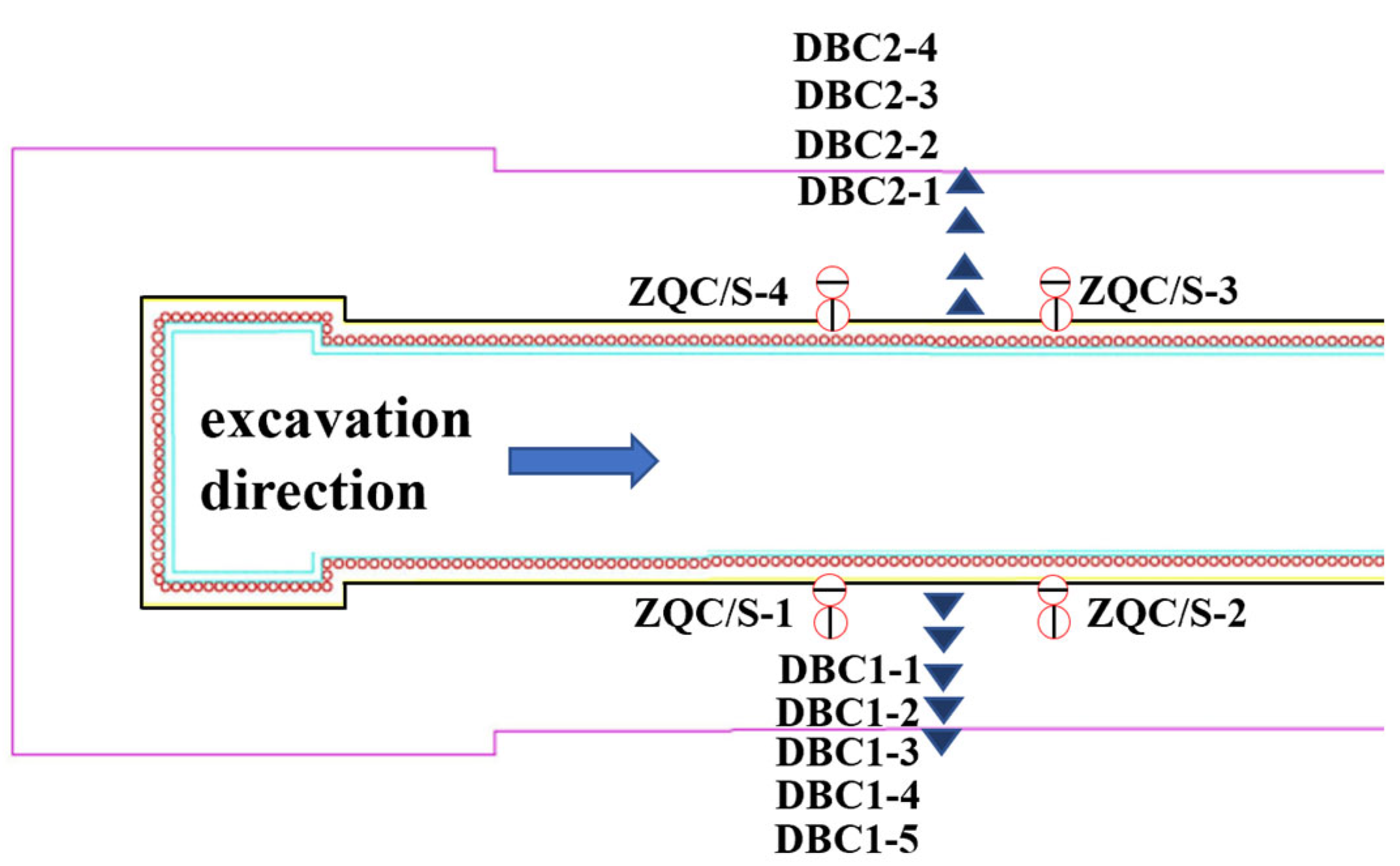

As the main enclosing structure, the enclosing piles work together with the steel supports to provide structural support for the foundation pit and maintain the deformation of the surrounding soil. Data from four measurement points near a representative monitoring section are selected for analysis, as shown in

Figure 3, and the monitoring points are ZQC/S-1, ZQC/S-2, ZQC/S-3, and ZQC/S-4, which are distributed on both sides of the foundation pit.

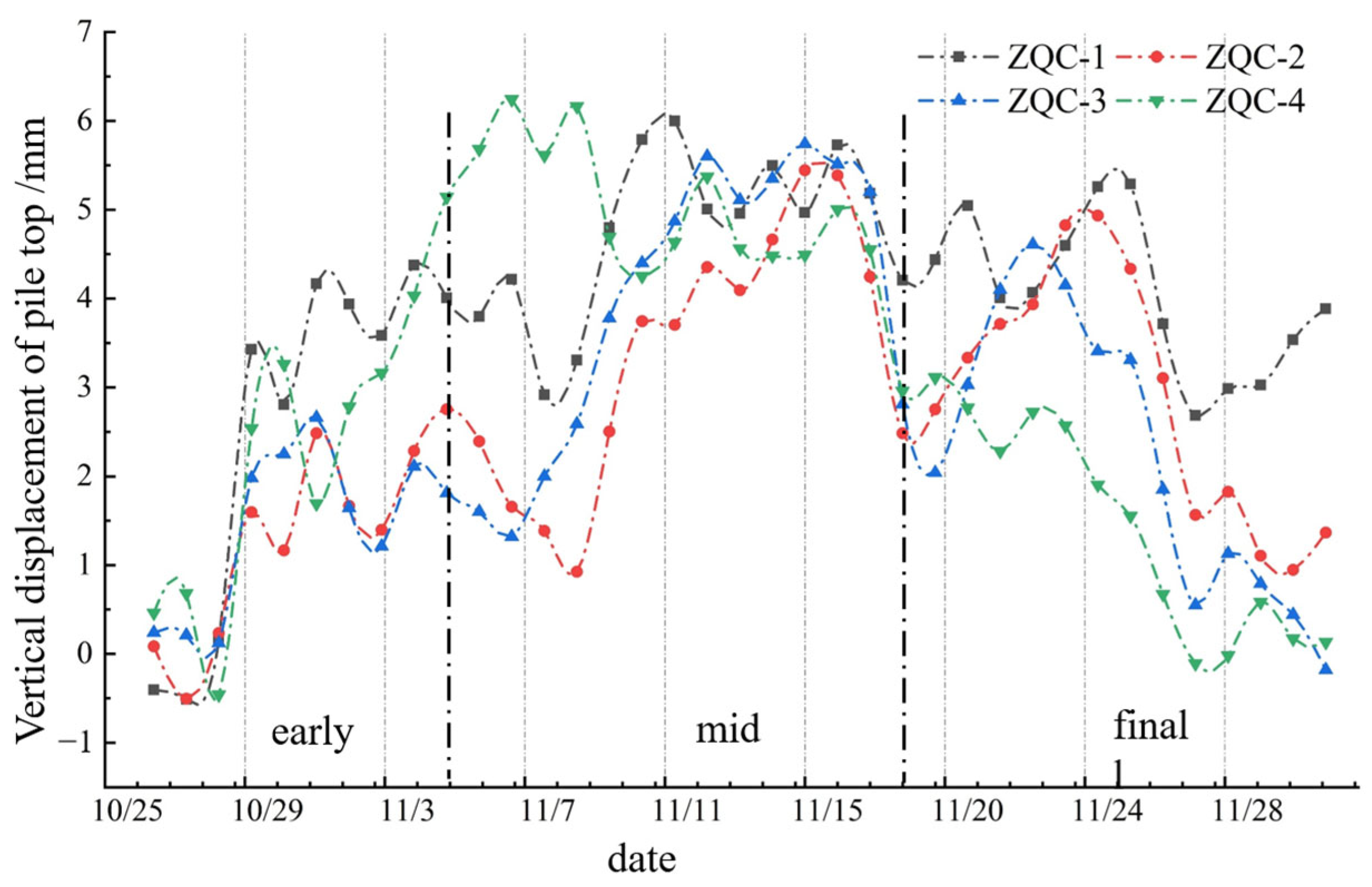

Figure 10 shows the changes in vertical displacement of the top of the pile with the excavation of the pit at each time point.

Figure 10 shows that the vertical displacement of pile tops is mainly bulging and wavy, and the bulging trends of the four measurement points are highly coincident. With the unloading of the excavation, the soil inside the pit releases its own gravity, the enclosure structure is deformed upward by the subsoil pressure, and deformed to the outside of the pit under the push of the multi-channel support axial force, and the two forces work together to make the enclosure structure bulge upward as a whole, and the maximum bulging occurs in the middle and late stages of the excavation, which is 6.2 mm. The maximum uplift occurs in the middle and late stages of excavation, which is 6.2 mm. Comparing the displacement changes in the pit edge of the model, it is found that both of them have a high degree of approximation and similar displacement values, which indicates that this numerical simulation analysis can simulate the construction situation better.

At the same time, the author analysis shows that the value of the bulge is reduced in the late stage of excavation, and the main reason is that after the soil excavation stress release stabilization, the station floor, side walls, and other construction processes are carried out to limit the change in the subsoil of the foundation pit and inhibit the upward soil pressure effect makes the bulge reduced, which shows that in the process of the station construction, it is necessary to follow up the construction progress in a timely manner, and through the process itself to complete the control of the displacement in order to achieve the purpose of safety. During the whole excavation process, the vertical displacement of the top of the enclosing piles is much smaller than the cumulative deformation control value of the vertical displacement of the top of the piles, and the settlement difference is normal, which meets the construction control requirements.

Horizontal deformation of the enclosing structure is one of the important indices for judging the stability of the foundation pit, and monitoring the deformation in the longitudinal direction of the support system can control the deformation status of the foundation pit in real time and take corresponding measures to prevent and control it.

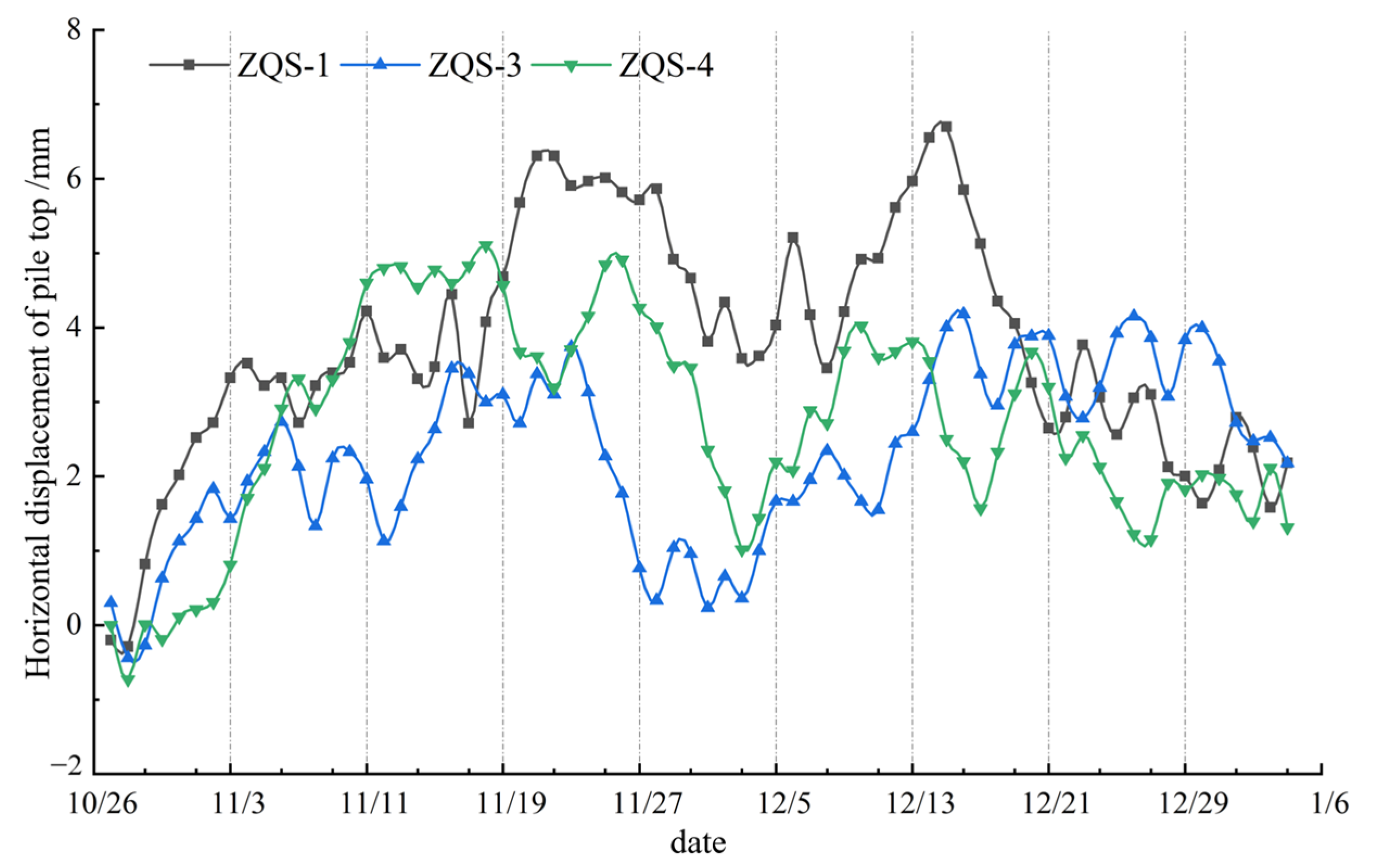

Figure 11 shows the horizontal displacement of the pile top in each time period.

Figure 11 shows that the horizontal displacement measurement points ZQS1 and ZQS3/4 are on the east and west sides of the foundation pit, and the overall displacement of the pile is shifted to the east side of the foundation pit with the center axis of the foundation pit as the base, showing the rule of change in the “anti-bending type”. The overall displacement of the pile top is mostly shifted to the outside of the foundation pit, and the maximum deformation value is within 6–8 mm. There are two reasons: (1) the high compressibility of miscellaneous fill and loess soil, and the soil body behind the perimeter piles is very easy to be compressed after being pushed outward by the gantry crane erected on the crown beam; and (2) under the influence of the construction, the steel support started to be erected after the crown beam is applied, and in order to reach the preset axial force, the perimeter piles will produce a large horizontal outward pushing force and outward thrust [

18].

According to the tracking analysis of the excavation process of the pit construction, comparing the measurement points ZQS4 and ZQS3, it is found that with the excavation of the pit, the horizontal displacement of the top of the enclosure pile becomes larger and larger, and the deformation value of the measurement point ZQS4 is larger than that of ZQS3 in the middle and late stages of the excavation, which is due to the fact that the measurement point ZQS4 is excavated to the bottom of the pit first and the subsequent stages of the construction will still have an impact. The decrease in pile top displacement in the later stage is mainly due to the horizontal force exerted at the bottom of the foundation pit by the construction of the station floor and other structures, which makes the displacement of the pile bottom increase to the outside, and the top of the pile shrinks and deforms horizontally to the inside.

The sudden decrease in displacement deformation values all occurred at the time nodes of the three steel support erections, indicating that the support erection is very important for displacement control in the process of foundation pit excavation construction, so it is important to support the erection in time to effectively control the deformation of the enclosure structure during the construction process [

19].

5.2. Analysis of Surface Deformation

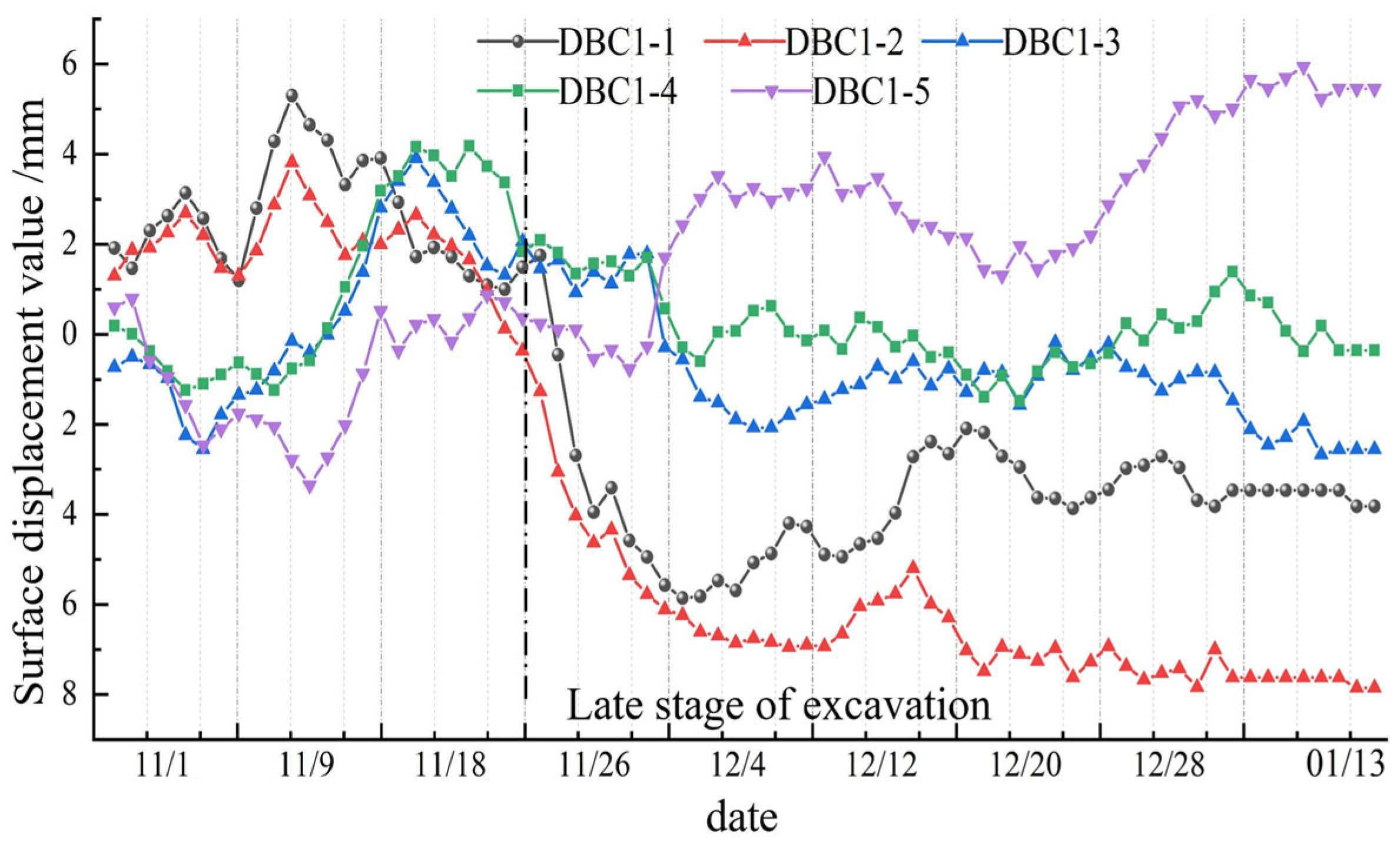

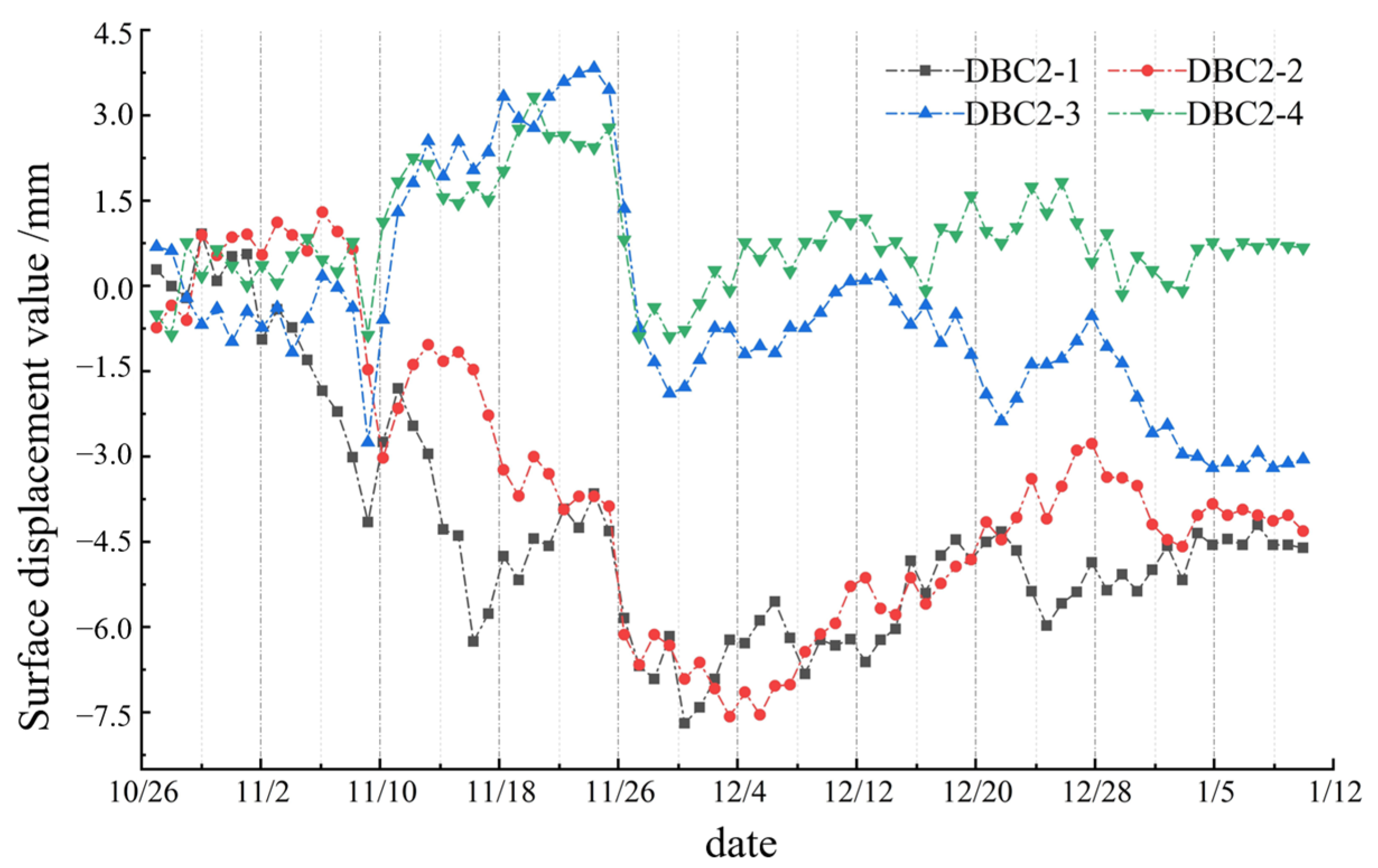

The two points in

Figure 3 are distributed along the longitudinal direction of the foundation pit, in which multiple measurement points of each monitoring point are arranged with a spacing of about 2 m from the edge of the foundation pit to the outside. Further, it is known from

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 that the measurement points near the edge of the foundation pit in the early stage of the excavation are mainly bulging, with the deformation value ranging from 2 to 5 mm. The further out the deformation is mainly settlement, and the farther away from the foundation pit, the greater the settlement. The settlement value is increased from 0 to 8 mm, and the overall trend is almost the same as that in the numerical simulation; in the late stage of the excavation, there is obvious settlement and deformation of the surrounding surface. The overall trend of change is approximately the same as that of the numerical simulation; in the late excavation, the surrounding surface’s overall obvious settlement deformation, with a maximum settlement deformation value of 7.8 mm. The reason is that the greater the depth of excavation, the more the depth of pit precipitation increases, and, when the precipitation increases to the water-rich sand layer, the drop in water level has a greater effect on the soil consolidation settlement [

20]. Further, in the open excavation of the enclosure structure to the outside of the side of the top of the big shift, enclosure structure rigidity, the bottom of the pit to the inside of the lateral shift occurs, making its pile back to the side, and the bottom of the pile back to the outside, and the bottom of the pit to the inside of the pit. Lateral shift occurs, so that its post-pile stratum stress release presents a trapezoidal distribution, and surface displacement is mostly manifested as settlement; at the same time, the construction of the station structure makes the soil stress redistributed, and the combination of multiple factors makes it appear the phenomenon of rapid growth of the settlement rate, and then the soil stress gradually reaches equilibrium, and the overall settlement tends to be stabilized [

21].

Therefore, in the construction of similar strata, the precipitation factor has a greater influence, and more attention should be paid to the settlement deformation brought by the water-rich soil layer; each step of the construction process will have an influence on each other, and it is necessary to consider all the relevant factors in advance during the construction, so as to ensure the construction safety [

22,

23,

24,

25]. From the statistical analysis of the monitoring data, the cumulative surface settlement and deformation values of other measurement points in the vicinity are less than 10 mm, which meet the requirements of pit deformation control.

To further investigate the root cause of the observed “step-like” deformation and the discrepancy between simulation and measurement, it is essential to scrutinize the actual construction timing. The spatiotemporal evolution of the retaining structure in water-rich sand is highly sensitive to the duration of the unsupported state.

Table 3 presents the reconstructed construction sequence and detailed time logs for the representative monitoring section. As indicated in the table, the unsupported exposure time during the critical sand layer excavation reached approximately 18–24 h. This significant time lag between excavation and support installation provides a quantitative basis for analyzing the stress relaxation mechanism discussed in the following section.

6. Discussion: Mechanism of Deformation Divergence

While the numerical simulation captures the general trend of the excavation behavior, a critical comparison with field monitoring data reveals significant divergences in deformation modes. As shown in

Figure 14, the field data exhibits a distinct “step-like” horizontal displacement and larger surface settlement compared to the smooth “bulging” curves predicted by the simulation. This section analyzes the mechanical origins of these discrepancies, focusing on the rheological properties of the water-rich sand layer and fluid–solid coupling effects.

6.1. Mechanism of “Step-like” Deformation Evolution

The most notable discrepancy is the transition of the pile deformation mode from “bulging” (simulation) to “step-like” (monitoring). In the numerical model, the excavation and support installation are simulated as instantaneous steps within a continuous elastoplastic continuum. However, in the actual construction of water-rich sand strata, the soil exhibits distinct “time-dependent stress relaxation” characteristics.

Sand, being a cohesionless material, is highly sensitive to the stress release path. During the time interval between excavation and the pre-loading of the steel support (the “unsupported exposure time”), the retaining piles undergo rapid inward displacement driven by the active earth pressure. As noted by Ren et al. [

7], the earth pressure in sandy layers adjusts dynamically with time. When the support is finally installed, the upper part of the pile is already displaced, while the lower part (embedded in the soil) remains relatively fixed, creating a “kick-out” or “step” point at the excavation interface. Notably, the vertical position of these steps correlates strongly with the excavation layer thickness (2 m), suggesting that the depth of each ‘kick-out’ is physically determined by the height of the unsupported excavation face. The standard Modified Mohr–Coulomb model used in the simulation simplifies this time-dependent plastic flow, thus producing a smoother, idealized curve. Furthermore, real-world geological discontinuities, such as localized uneven sand density or the presence of lenticular inclusions, can cause stress concentrations that differ from the homogeneous isotropic assumptions in the numerical model, contributing to the slight asymmetry and fluctuations observed in the field displacement distribution. This finding suggests that in high-permeability sand, shortening the exposure time is more critical for deformation control than merely increasing support stiffness.

6.2. Impact of Seepage and Dewatering on Settlement

Regarding ground settlement, the measured values (up to 7.8 mm) exceed the numerical predictions (approx. 3–4 mm). This underestimation is primarily attributed to the simplification of the fluid–solid coupling effect in the simulation. The simulation mainly considers the mechanical unloading of the soil mass. However, in this project, continuous dewatering was required to maintain a dry working face in the water-rich sand layer.

According to Terzaghi’s effective stress principle (σ’ = σ − u), the reduction in pore water pressure (u) due to dewatering leads to a corresponding increase in the effective stress (σ’) of the soil skeleton. This increase causes additional consolidation settlement of the soil outside the pit, which is superimposed onto the settlement caused by excavation unloading. Tian et al. [

9] and Xu et al. [

10] demonstrated that in permeable strata, seepage forces induced by hydraulic gradients can significantly amplify microscopic particle migration and macroscopic deformation. The “step-like” deformation of the retaining wall further exacerbates this by creating localized volume loss zones behind the piles, leading to the observed “trapezoidal” settlement profile (

Figure 12) rather than the standard “peck-type” settlement.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

While this study elucidates the mechanism of step-like deformation, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the numerical simulation utilized the Modified Mohr–Coulomb (MMC) model. While effective for engineering design, the MMC model does not fully capture the intrinsic time-dependent creep behavior of sand, which could be better represented by rheological models (e.g., the Burger model) in future theoretical studies. Second, due to site constraints, pore water pressure and pile toe displacement were not directly monitored; their contributions were inferred from surface settlement and pile top displacement, respectively. Finally, the influence of alternative excavation sequences (e.g., center-to-sides) on suppressing step-like deformation warrants further investigation through comprehensive parametric simulations.