An Instrumented Drop-Test Analysis of the Impact Behavior of Commercial Laminated Flooring Brands

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- The wear layer—A transparent protective layer, with high resistance to scratches, abrasion, impacts, liquid penetration, minor mechanical stresses, and other minor everyday “disasters”, serving to maintain its original appearance.

- -

- Decorative layer—High-resolution printed layer that faithfully reproduces the appearance of natural materials. It can imitate a wide range of finishes, including wood, ceramic tiles, marble, natural stone, concrete, or other custom designs.

- -

- Based layer (made of wood)—The main structural component of laminate flooring, made of wood fibers compressed at high temperature and pressure, providing strength, dimensional stability, and durability without deformation.

- -

- Backing layer—An additional layer of protection, usually made of melamine or other moisture-resistant materials, which improves structural stability and provides protection against moisture, maintaining the appearance of the floor in any climate.

- -

- Support/insulation layer—Foundation layer for installing the flooring, which helps to correct unevenness in the substrate, reduce walking noise, and increase walking comfort. It may include a moisture barrier for protection in areas exposed to water.

2. Standard and Non-Standard Tests for Impact Resistance of Laminated Flooring

3. Materials, Methods and Equipment

- 2 J is roughly equivalent to the impact energy of dropping a mobile phone,

- 3 J corresponds to dropping a ceramic mug,

- 5 J corresponds to dropping a 0.5 L bottle of water.

4. Results

4.1. Parameters Resulted from the Instrumented Test

- -

- Fmax—The peak value of the measured force, during the impact,

- -

- t(Fmax)—Time to the peak force (from the last recorded value F = 0), till Fmax,

- -

- tf—Impact duration, from t(F=0) till the measured force reaches the null value again, after an evolution till Fmax,

- -

- Emax—Maximum measured impact energy (the total energy transferred when the impactor stops (v = 0), i.e., all kinetic energy has been absorbed by the sample, after which part of this energy is returned to the impactor in the form of kinetic energy (recoil)),

- -

- dmax—The maximum displacement of the impactor and the maximum deformation of the sample (plastic deformation + elastic deformation),

- -

- vmax—The maximum velocity, considered when the impactor touches the sample (meaning the same moment when the last value zero is measured for the force; after that the force is constantly increasing till Fmax).

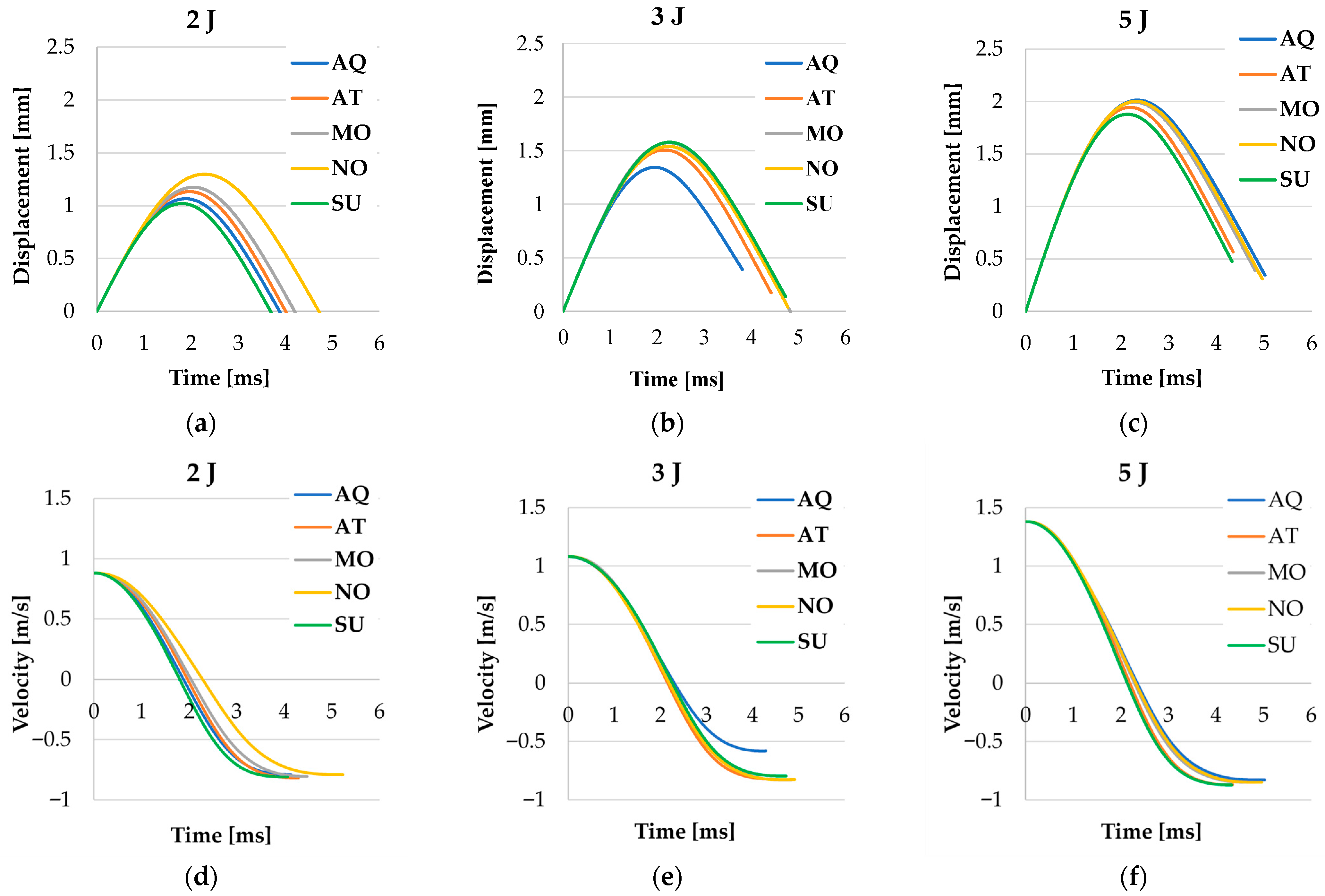

4.2. Influence of Impact Energy on Each Tested Brands

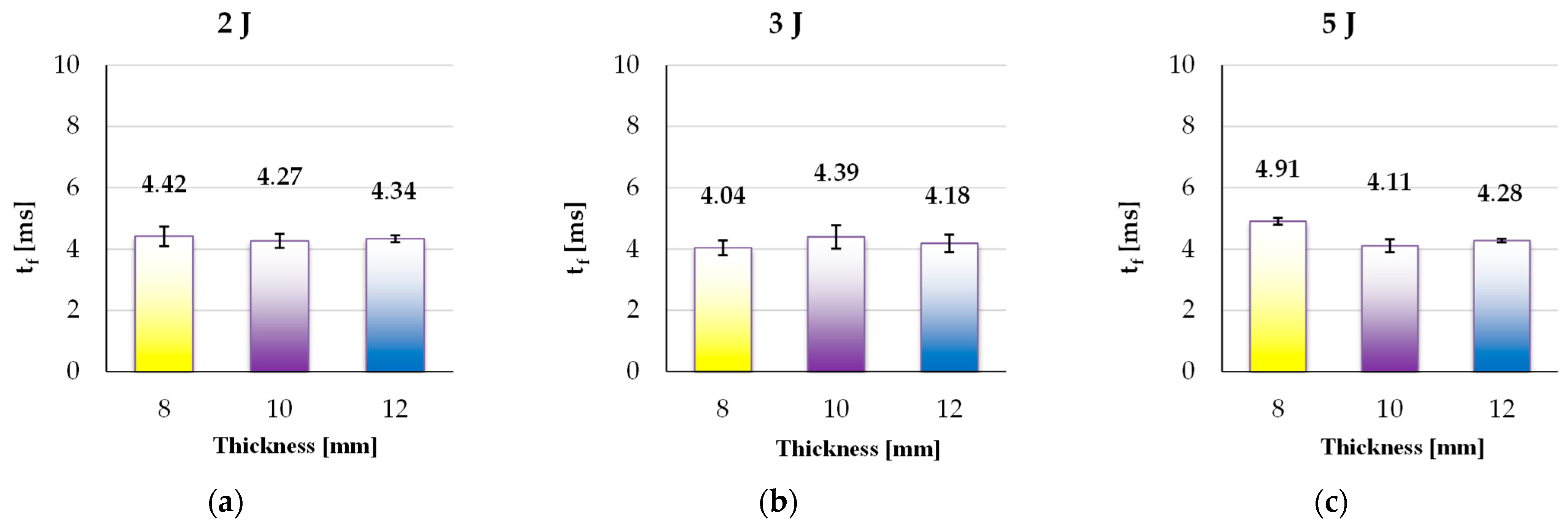

4.3. Influence of Thickness of the Laminated Flooring

- -

- For 2 J and 3 J, the variation is not sensitive to thickness, but it can be seen that although the values are within a very small range, those for 3 J are slightly higher, which was to be expected,

- -

- For 5 J, the values suggest a slight decrease with thickness, and the size of the footprint is slightly inversely proportional to the thickness of the parquet.

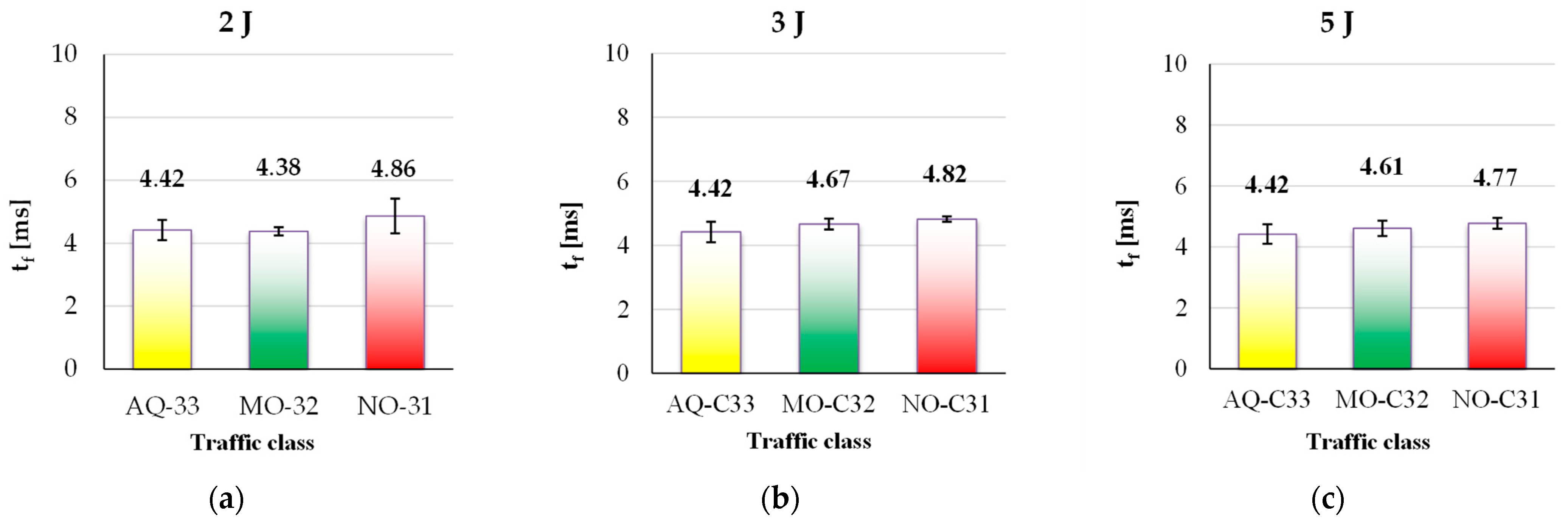

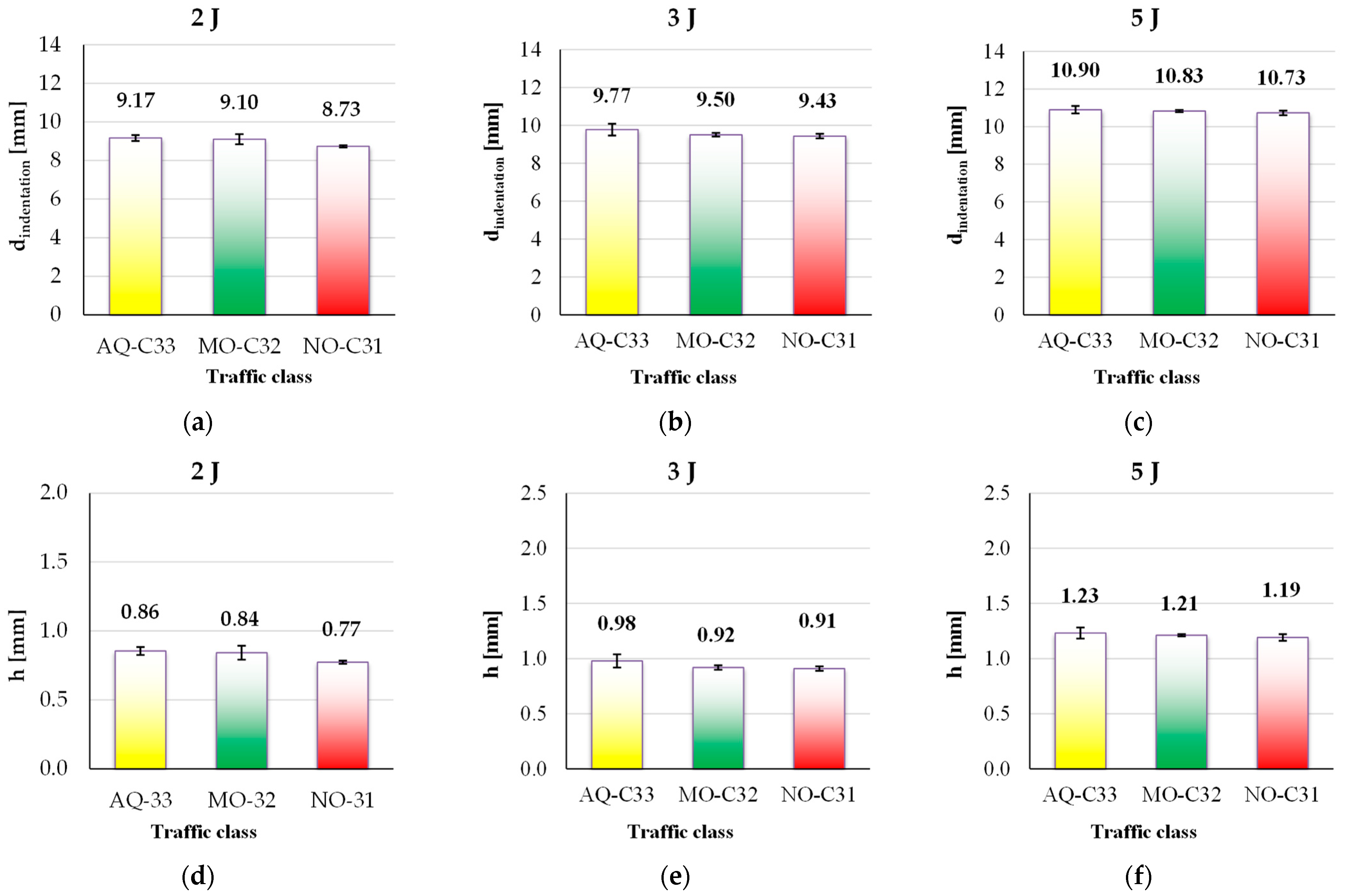

4.4. Influence of Traffic Class of the Tested Brands

- -

- At 2 J, the minimum value for Fmax was obtained for the NO brand (class C31), with the other two brands having very similar values for this parameter,

- -

- At 3 J, there is a clear upward trend in Fmax, to 4253 N,

- -

- At 5 J, Fmax increases from 3893 N for class C33 to 4958 N for class C31.

- -

- At 2 J, dmax increased from 1.13 mm to 1.21 mm, a small difference,

- -

- At 3 J, the difference was greater, from 1.13 mm to 1.53 mm,

- -

- At 5 J, the largest difference for dmax was obtained, measuring 0.89 mm, from 1.13 mm to 2.02 mm.

- -

- At 2 J, although the minimum value was obtained for class C33, 1.73 J, the difference from the other traffic classes is too small to highlight a dependence on the traffic class, at least for these brands,

- -

- At 3 J, low values were obtained for class C33, which could be explained by local variations in the quality of the flooring or/and by the increased rigidity of this brand,

- -

- At 5 J, the difference between traffic class C33 and traffic class C31 is only 0.15 J, which represents only 7.8% of the energy absorbed by the brand of traffic class C33.

- -

- 0.44 mm at an impact energy of 2 J,

- -

- 0.34 mm at an impact energy of 3 J,

- -

- 0.23 mm at an impact energy of 5 J.

5. Discussions

- -

- Brands with higher rigidity → recommended for heavy traffic, commercial spaces,

- -

- Brands with better energy dissipation capacity → useful for areas where accidental impact is more likely (e.g., children’s rooms, workshops).

- They allow objective comparison of performance between brands and traffic classes;

- They can support manufacturers in optimizing recipes and technological processes;

- They provide consumers and designers with clear information for selecting the adequate materials according to the usage scenario—residential, commercial, or industrial traffic;

- They can form the basis for improving current standards by integrating quantifiable parameters, not just visual assessments.

- -

- Parameters sensitive to the impact energy are as follows:

- -

- Indentation diameter, dindentation, increases visibly with impact energy (the best discriminator between brands and thicknesses), the indentation depth, h, derives from dindentation, maintains the same trend;

- -

- Absorbed energy, Eabsorbed, tends to increase with the impact energy; more visible for ranking at 5 J;

- -

- Maximum force, Fmax, generally increases with the impact energy (moderate sensitivity, but relevant at 5 J, for the tested brands).

- -

- Less sensitive/almost independent parameters are as follows:

- -

- Impact duration, tf—Small variations in the 2–5 J range,

- -

- Time to Fmax, t(Fmax)—Small differences between energies.

6. Conclusions

- At low energies (2 J and 3 J), the maximum force (Fmax) increases with the thickness of the board, confirming a better impact response for the thicker boards.

- At 5 J energy, the general trend is maintained, but there are small deviations, which can be attributed to the limited number of tests or local variations in sample quality.

- The diameter of the indentation decreases with increasing thickness, indicating better resistance to local deformation for the tested samples—the percentage differences were the greatest at 5 J (over 9%).

- The absorbed energy increases slightly with thickness (up to ~41% for 10–12 mm plates, at 5 J), confirming a slightly improved energy-dissipation ability within the tested thickness range.

- At the low impact energy level of 2 J, the differences between the traffic classes are minimal or even negligible. However, at impact energy levels of 3 J and 5 J, a slight increasing trend in the maximum impact force can be observed, from the higher class (C33) toward the lower class (C31).

- For the higher impact energy levels (3 J and 5 J), a modest increase in maximum impact force was recorded from the upper traffic class C33 (heavy commercial) toward the lower class C31 (light residential), suggesting that class-related differences are limited for the tested specimens.

- The time-related parameters (impact duration and the time to reach Fmax) exhibit only minor variations, with a slight increase from C33 to C31. This pattern suggests a slightly stiffer impact response for C33 within the tested range.

- The indentation diameter proved to be the most sensitive indicator; nevertheless, the differences among the classes (C33, C32, C31) were small, reflecting a comparable performance level among the tested brands. This similarity is likely attributable to similarities in the protective top layer used by the analyzed brands, whose formulation is legally protected.

- The difference in indentation diameter, from the impact energy 2 J to 5 J, is 1.73 mm for C33 and C32 brands and 2.00 mm for the class C31, meaning that the selection should include other parameters required by the particular aspects of usage. Although C33 is designed for heavy-duty traffic, under impact loading it exhibited larger indentations compared with C31 and C32. This finding indicates that impact resistance does not depend only on the declared traffic class, but also on brand-specific multilayer construction. The influence of impact energy level on tested brand for class traffic pointed out that the absorbed energy differs very low among classes (maximum 7–8% at 5 J, between C33 and C31), suggesting a very similar quality level for the designated traffic classes, likely influenced by the formulation of the upper protective layer.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Floorcovering Certified Inspection Service—CA. Available online: http://www.inspectorfloors.com/laminate/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Wikipedia. Laminate Flooring. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laminate_flooring (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Laminate Flooring. Available online: https://mohawkind.com/products.php#laminate (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Brief History of Parquet Flooring. Available online: https://www.solidfloor.co.uk/journal-posts/brief-history-of-parquet-flooring?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Our History. Available online: https://valinge.com/about-us/history/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Quick-Step Laminate Flooring. Available online: https://flooringking.co.uk/laminate-flooring/quickstep-laminate/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Unilin Reaches Agreements with Välinge & Beaulieu. Available online: https://www.floordaily.net/floorfocus/unilin-reaches-agreements-with-vlinge--beaulieu- (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zhou, K.; Cheng, J.; Fan, M. Study on Innovative Laminated Flooring with Resin-Impregnated Paper. Buildings 2024, 14, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Different Laminate Flooring Patterns. Available online: https://elephantfloors.net/blog/different-laminate-flooring-patterns/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Chevron & Herringbone: History of These Popular Parquet Wood Flooring Patterns. Available online: https://anthologywoods.com/aw-blog/chevrons-herringbone-history-of-these-popular-wood-flooring-patternsand?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- The Layers of Laminate. Available online: https://www.contractinteriorsflooring.com/products/product-articles/laminate/the-layers-of-laminate?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Unveiling the Layers: What Are Laminate Floors Made Of? Available online: https://www.diverseflooring.ca/blog/articles/unveiling-the-layers-what-are-laminate-floors-made-of?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- What is Laminate Flooring: A Complete Guide. Available online: https://horizonbespokejoinery.ie/blog/what-is-laminate-flooring/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Weldon, J. Parquetry Floors. Available online: https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/parquetry/parquetry.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- What Exactly is Laminate Flooring? Available online: https://nalfa.com/what-is-laminate/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- North American Laminate Flooring Association. NALFA Standards Publication LF 01-2003; North American Laminate Flooring Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Available online: https://www.floorreports.com/images/technotes_files/45.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- AC Rating. Available online: https://www.envirobuild.com/indoor-flooring/laminate/ac-rating (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- ANSI Standards. Performance Testing Standards. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20120511105151/http://nalfa.com/ansi_standards.php (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- EN 13329; Laminate Floor Coverings—Elements with a Surface Layer Based on Aminoplastic Thermosetting Resins. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- Product Certification Standards. Available online: https://nalfa.com/product-certification-standards/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- ISO 24335:2022; Laminate Floor Coverings—Determination of Impact Resistance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- EN 17368:2020; Laminate Floor Coverings—Determination of Impact Resistance with Small Ball. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ASTM F1265; Standard Test Method for Resistance to Impact for Resilient Floor. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D2794; Standard Test Method for Resistance of Organic Coatings to the Effects of Rapid Deformation (Impact). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1968.

- EN 13696; Wood Flooring—Test Methods to Determine Elasticity and Resistance to Wear and Impact Resistance. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- EN 14342:2013; Wood Flooring and Parquet-Characteristics, Evaluation of Conformity and Marking. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- EN 438-2:2016; High-Pressure Decorative Laminates (HPL)-Sheets Based on Thermosetting Resins (Usually Called Laminates)-Part 2: Determination of Properties. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- EN 16511:2023; Modular Mechanical Locked Floor Coverings (MMF)-Specification, Requirements and Test Method for Multilayer Modular Panels for Floating Installation. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- EN ISO 26987:2012; Resilient Floor Coverings-Determination of Staining and Resistance to Chemicals. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- ISO 4898; Rigid Cellular Plastics—Thermal Insulation Products for Buildings—Specifications. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- EN ISO 846:2019; Plastics—Evaluation of the Action of Microorganisms. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- ISO 4611:2019; Resistance to Humid Aging. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Swiss Krono. Flooring. Available online: https://www.swisskrono.com/global-en/about-us/swiss-krono-group/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Pergo Laminate Floors. Beautiful, Elegant Floors for Tough Living. Available online: https://int.pergo.com/en/laminate?page=1&page_size=15&sort=commercialrangename&sort_type=asc&view_size=15 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Laminate Flooring. Combining the Best in Performance and Beauty. Quick Step Floor Designers. Available online: https://int.quick-step.com/en/laminate (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Arenas, J.P. Impact Sound Insulation of a Lightweight Laminate Floor Resting on a Thin Underlayment Material above a Concrete Slab. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseby, T.; Shearer, A. Investigation of Impact Isolation of Flooring Products and Resilient Underlays. In Proceedings of the AASNZ Acoustics Conference 2016, Brisbane, QLQ, Australia, 9–11 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Services for Floorings/Sports Areas and Deckings. Available online: https://www.ihd-dresden.com/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/IHD/wissensportal/Broschueren/Bodenbel%C3%A4ge/BroschuereBodenbelaege_E.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Acuña, L.; Sepliarsky, F.; Spavento, E.; Martínez, R.D.; Balmori, J.-A. Modelling of Impact Falling Ball Test Response on Solid and Engineered Wood Flooring of Two Eucalyptus Species. Forests 2020, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunguleasa, A.; Spirchez, C.; Radulescu, L.; Diaconu, M.T. The Ball Response on the Beech Parquet Floors Used for Basketball Halls. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydor, M.; Pinkowski, G.; Jasińska, A. The Brinell Method for Determining Hardness of Wood Flooring Materials. Forests 2020, 11, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instron CEAST 9350—Universal Testing Systems. Available online: https://www.instron.us/en-us/products/testing-systems (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- WB1268C; CEAST 9300 Series—Droptower Impact Systems. Illinois Tool Works Inc.: Glenview, IL, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.instron.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ceast-9300-series-2.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Taber Abraser (Abrader). Available online: https://www.taberindustries.com/taber-rotary-abraser (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Germany’s DIN 51130 Slip Test: What’s It Good For? Available online: https://safetydirectamerica.com/germanys-din-51130-slip-test-whats-it-good-for/?srsltid=AfmBOoqqZC4RKCgkSJq53BpvI2IeG4Xs11-SM6L31V-a1tGnrdNQqI_p&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- EOTA TR 001:2003; Determination of Impact Resistance of Panels and Panel Assemblies. European Organisation for Technical Assessment (EOTA): Brussels, Belgium, 2003. Available online: https://www.eota.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/Technical%20reports/trb001.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- ETAG 004:2013; Guideline for European Technical Approval of External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems. European Organisation for Technical Assessment (EOTA): Brussels, Belgium, 2013. Available online: https://www.eota.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/ETAGs/etag-004-february-2013.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Underlay Materials Under Laminate Floor Coverings—Test Standards and Performance Indicators. Available online: https://eplf.com/storage/files/tb_-_eplf_underlay_materials_under_laminate_floor_coverings_2019-02_en_.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- E03C—Material Guides—Flooring, Canada. Available online: https://www.floorcoveringreferencemanual.com/e03c-flooring.html (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- OETI Services Overview—Laminate and Wood Floorcoverings. Available online: https://www.oeti.biz/uploads/oeti/downloads/flooring/Flooring_brochure-range-of-services-laminate-and-wood-floor-coverings_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- EN 14354:2017; Wood-Based Panels—Wood Veneer Floor Coverings. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- EN 1534; Wood Flooring—Determination of Resistance to Indentation (Brinell). CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- ISO 24338; Resilient Floor Coverings—Determination of Dimensional Stability and Curling after Exposure to Heat. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 10140-3; Acoustics—Laboratory Measurement of Sound Insulation of Building Elements. Part 3: Measurement of Impact Sound Insulation. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Vienna Agreement—Agreement on Technical Co-Operation Between ISO and CEN. Available online: https://boss.cen.eu/media/CEN/ref/vienna_agreement.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- EN 13629:2020; Wood Flooring—Solid Individual and Pre-Assembled Hardwood Boards. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- EN 13489:2017; Wood Flooring and Parquet—Multi-Layer Parquet Elements. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 14001:2019; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Pimiento, N.N. Laminated Wood and Chipboard Flooring towards Environmentally Friendly Alternatives. Electron. Vis. 2014, 7, 206–220. [Google Scholar]

- SR EN 438-4:2016; Stratificate Decorative de Înaltă Presiune (HPL)—Plăci pe Bază de Rășini Termorigide. Partea 4: Clasificare și Specificații Pentru Stratificate Compacte ≥ 2 mm. ASRO: Bucharest, Romania, 2016.

- SR EN 13893:2004; Acoperiri Rezistente la Șoc, Stratificate și Textile Pentru Pardoseală—Determinarea Coeficientului Dinamic de Frecare pe Suprafața Uscată. ASRO: Bucharest, Romania, 2004.

- ISO 6603-2:2023; Plastics—Determination of Puncture Impact Behaviour of Rigid Plastics. Part 2: Instrumented Impact Testing. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Parchet Laminat 12 mm Krono Original Atlantic K476PP, Inca V, Class 33. Available online: https://www.dedeman.ro/ro/parchet-laminat-12-mm-krono-original-atlantic-k476pp-inca-v-clasa-33/p/4026652 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- AQUApro Select TILE 8.0 Sm. Available online: https://cdn.dedeman.ro/media/catalog/product/fise-tehnice/Fisa_tehnica_AQUApro_Select_TILE_8.0_Sm_RO.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Parchet Laminat 10 mm Krono Original Supreme K419, Armoury Oak, Class 33. Available online: https://www.dedeman.ro/ro/parchet-laminat-10-mm-krono-original-supreme-k419-armoury-oak-clasa-33/p/4027199 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Parchet Laminat 8 mm Krono Original Novella K337, Hayloft Oak, Class 31. Available online: https://www.dedeman.ro/ro/parchet-laminat-8-mm-krono-original-novella-k337-hayloft-oak-clasa-31/p/4027517 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Parchet Laminat 10 mm Krono Original Modera Plus 5985, Sherwood Oak, Class 32. Available online: https://www.dedeman.ro/ro/parchet-laminat-10-mm-krono-original-modera-plus-5985-sherwood-oak-clasa-32/p/4023997 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- OSB3; Load Bearing Boards for Use in Humid Conditions OSB3. KronoSpan Trading SRL: Sebeș, Romania, 2006. Available online: https://kronospan.com/ro_RO/products/view/kronobuild/osb/osb-3/osb-3-699/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Özen, M. Influence of Stacking Sequence on the Impact and Postimpact Bending Behavior of Hybrid Sandwich Composites. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2017, 52, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.J.; Cantwell, W.J. Impact Damage Initiation in Composite Materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassir, N.A.; Guan, Z.W.; Birch, R.S.; Cantwell, W.J. Damage Initiation in Composite Materials under Off-Centre Impact Loading. Polym. Test. 2018, 69, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaycıoğlu, H. Evaluation of Surface Characteristics of Laminated Flooring. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 7053–7058. [Google Scholar]

- Tita, V.; de Carvalho, J.; Vandepitte, D. Failure Analysis of Low Velocity Impact on Thin Composite Laminates: Experimental and Numerical Approaches. Compos. Struct. 2008, 83, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.J.; Arumugam, V.; Santulli, C.; Jennifers, A.; Poorani, M. Failure Modes of GFRP after Multiple Impacts Determined by Acoustic Emission and Digital Image Correlation. J. Eng. Technol. 2015, 6, 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tiberkak, R.; Bachene, M.; Rechak, S.; Necib, B. Damage Prediction in Composite Plates Subjected to Low Velocity Impact. Compos. Struct. 2008, 83, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, G.C.; Deleanu, L.; Chiracu, I.G.; Boțan, M.; Ojoc, G.G.; Vasiliu, A.V.; Cantaragiu Ceoromila, A. Influence of Resin Grade and Mat on Low-Velocity Impact on Composite Applicable in Shipbuilding. Polymers 2025, 17, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Typical Values | Light Residential (Bedrooms, Guest Rooms) | High-Traffic Areas (Living Rooms, Halls) | Commercial Spaces (Offices, Small Shops) | High Commercial Activity (Public Spaces, Large Retails) | Light Industrial (Technical Areas) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plank thickness | 6–7 mm | ✔ | – | – | – | – |

| 8 mm | ✔ | ✔ | – | – | – | |

| 10–12 mm | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Abrasion class | AC3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ Limited | AC3 | ✔ |

| AC4 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | – | – | |

| AC5 | – | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| AC6 | – | – | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Level of use (EN 13329) [19] | 21–23 | ✔ | ✔ | – | – | – |

| 31–32 | – | ✔ | ✔ | – | – | |

| 33–34 | – | – | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Resistance to humidity | Standard | ✔ ** | ✔ ** | – | – | – |

| Resistant to humidity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Impermeable | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Phonic insolation (dB) | <17 dB | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| ≥18 dB | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Compatible with floor heating | Yes | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| No | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ (No) |

| Brand | Codification | Thickness (mm) | Traffic Class | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krono Original Atlantic K476PP, Inca V [64] | AT | 12 | 33 | Kronospan Trading SRL, Brasov, Romania |

| AQUApro Select TILE 8.0 Sm [65] | AQ | 8 | 33 | Kaindl Flooring, Salzburg, Austria |

| Krono Original Supreme K419 [66] | SU | 10 | 33 | Kronospan Trading SRL, Brasov, Romania |

| Krono Original Novella K337 [67] | NO | 8 | 31 | Kronospan Trading SRL, Brasov, Romania |

| Krono Original Modera Plus 5985 [68] | MO | 8 | 32 | Kronospan Trading SRL, Brasov, Romania |

| Load Bearing Board (OSB3) [69] | - | 8 | - | Kronospan Trading SRL, Brasov, Romania |

| Nominal Impact Energy [J] | Average Maximum Value [J] | Standard Deviation [J] | Standard Deviation (%) | Ratio Emax/Enominal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2.120 | 0.004 | 0.215846 | 1.060 |

| 3 | 3.180 | 0.0065 | 0.205866 | 1.060 |

| 5 | 5.171 | 0.0063 | 0.123748 | 1.034 |

| AQ (8 mm) | SU (10 mm) | AT (12 mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emax [J] | 5.18 | 5.16 | 5.16 |

| Eabsorbed [J] | 1.92 | 2.12 | 2.13 |

| Percentage ratio for Eabsorbed/Emax | 37.06 | 41.0 | 41.2 |

| Energy Level [J] | [%] |

|---|---|

| 2 | −7.88 |

| 3 | −4.71 |

| 5 | −9.17 |

| Parameter, at 5 J | AQ (8 mm) | SU (10 mm) | AT (12 mm) | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmax [N] | 4774.20 | 5743.60 | 5472.00 | Increase with thickness, but with small local variations |

| dindentation [mm] | 10.90 | 10.33 | 10.07 | Smaller values at greater thicknesses |

| Eabsorbed [J] | 1.92 | 2.12 | 2.13 | Light increase with thickness |

| Parameter, at 5 J | AQ-C33 (8 mm) | MO-C32 (8 mm) | NO-C31 (8 mm) | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmax [N] | 4774.20 | 5188.01 | 4958.12 | Increase from class C33 to class C31, but with local variations. |

| dindentation [mm] | 10.90 | 10.83 | 10.73 | Tendency to decrease from class C33 to class C31. |

| Eabsorbed [J] | 1.92 | 2.07 | 2.02 | A better absorbing energy capacity for traffic classes C32 and C31. |

| Ratio Eabs/Emax [%] | 37.06% | 40.0% | 39.07% | Light increase from the traffic class C33 to C31. |

| Impact duration, tf [ms] | 4.91 | 4.61 | 4.77 | Light decrease with traffic class (from C33 to C31), but with small differences. |

| Time to Fmax, t(Fmax) [ms] | 2.06 | 2.00 | 2.13 | Very small differences. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vasiliu, A.V.; Tudurache, C.; Cristea, G.C.; Constandache, M.; Azamfirei, V.; Martin, M.C.; Ojoc, G.G.; Deleanu, L. An Instrumented Drop-Test Analysis of the Impact Behavior of Commercial Laminated Flooring Brands. Buildings 2026, 16, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020259

Vasiliu AV, Tudurache C, Cristea GC, Constandache M, Azamfirei V, Martin MC, Ojoc GG, Deleanu L. An Instrumented Drop-Test Analysis of the Impact Behavior of Commercial Laminated Flooring Brands. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020259

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasiliu, Alexandru Viorel, Constantin Tudurache, George Cătălin Cristea, Mario Constandache, Valentin Azamfirei, Marian Claudiu Martin, George Ghiocel Ojoc, and Lorena Deleanu. 2026. "An Instrumented Drop-Test Analysis of the Impact Behavior of Commercial Laminated Flooring Brands" Buildings 16, no. 2: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020259

APA StyleVasiliu, A. V., Tudurache, C., Cristea, G. C., Constandache, M., Azamfirei, V., Martin, M. C., Ojoc, G. G., & Deleanu, L. (2026). An Instrumented Drop-Test Analysis of the Impact Behavior of Commercial Laminated Flooring Brands. Buildings, 16(2), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020259