Mechanisms and Protection Strategies for Concrete Degradation Under Magnesium Salt Environment: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study on the Damage Mechanism of Concrete Under Magnesium Salt Attack

2.1. Magnesium Chloride Attack

2.1.1. Chloride Ion Transport Mechanism

- (1)

- (2)

- The development of cracks is another distinctive feature unique to Mg attack. The crystallization pressure produced by Mg salts causes internal micropores/cracks to form inside concrete; such pores/cracks then become ‘highways’ along which ingress occurs. Studies have shown [19,20] that once the crack width exceeds 0.07 mm, the rate of Cl migration increases dramatically in a nonlinear fashion compared with pure diffusion without cracking.

- (3)

- Under wet–dry cycles, “pump effect” is further enhanced by magnesium-induced surface degradation: the magnesium salts attack causes surface scaling/spalling (physical removal of the protective layer), which in turn decreases the resistance to capillary uptake, thus favoring a faster accumulation and inward migration of chloride ions during wet phases [21].

- (4)

- Permeation and electromigration are further promoted by chemical effects: unlike what happens in NaCl solutions (where the pore fluid stays highly alkaline), the hydrolysis of Mg2+ leads to precipitation of Mg(OH)2, with a strong decrease in pH. Acidification destabilizes the electrostatic potential of the pore wall and decreases its capacity of repelling and binding Cl−, thereby enhancing their entry inside the specimen [22,23].

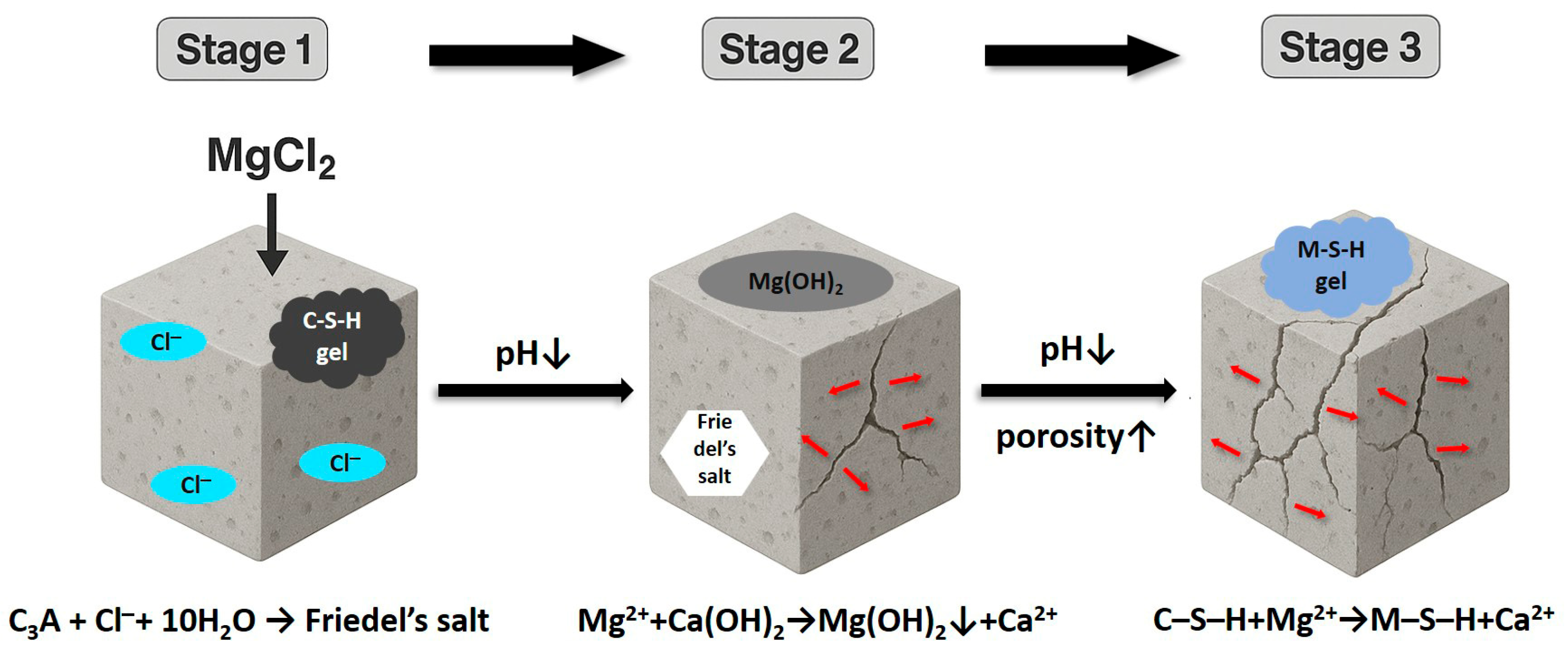

2.1.2. Mechanism of Magnesium Chloride Attack

- (1)

- Stage I—Ion-binding and sequestration effect. At the early stage, part of the entering Cl− is fixed by the cement matrix through chemical binding with aluminates to generate Friedel’s salt (3CaO·Al2O3·CaCl2·10H2O), and physical adsorption on C-S-H gels. Such fixation effects can temporarily “fix” free Cl−, forming a “buffer” effect which slows the rise in Cl− concentration in the pore solution [27,28,29].

- (2)

- Stage II-Critical threshold and depassivation. Once the binding capacity of concrete has been saturated, free chlorides will build up at the steel–concrete interface. Studies have shown that if the molar ratio of Cl−/OH− exceeds its critical threshold (usually between 0.6 and 1) [30,31], the protective passive film of the rebars would be unstable and destroyed. The threshold is not a fixed value but changes with the porosity, as well as the density of ITZ, as was reported by Sui et al. [32].

- (3)

- Stage III: Propagation and Positive Feedback Loop. After corrosion is initiated, the produced rust product has a volumetric expansion of about 6–10 times higher than steel, which will produce internal tensile stresses to crack the concrete cover [33,34,35]. These cracks develop into the shortcut path for migration, greatly increase the chloride diffusion coefficient (especially at the early stage of corrosion) [27], form another self-reinforced “corrosion–crack–migration” positive feedback loop, and cause the quick collapse of structures.

2.2. Magnesium Sulfate Attack

2.2.1. Chemical Corrosion Mechanism of Magnesium Sulfate

2.2.2. Physical Erosion Mechanism of Magnesium Sulfate

- (1)

- Theoretical Limitations: Equation (5) assumes a distinct phase transition driven by humidity (like Thenardite → Mirabilite). Applying this to MgSO4 is partially speculative. Unlike sodium sulfate, magnesium sulfate exhibits multiple metastable hydration states (e.g., kieserite, hexahydrite, epsomite) rather than a single direct transition. This complexity makes it difficult to accurately determine the specific volume change (VH-VA) and thermodynamic parameters in a real fluctuating environment [45].

- (2)

- Validated MgSO4 Mechanisms: Distinct from the theoretical assumptions based on sodium salts, experimental evidence has confirmed specific physical damage pathways for magnesium salts. The primary validated mechanism is the multi-step hydration expansion. MgSO4 hydrates evolve through various forms (MgSO4·nH2O, where n = 1, 6, 7). The transformation between these phases generates significant volume expansion. Furthermore, recent studies confirm that in the presence of sodium ions [46], the crystallization of double salts (specifically Na2Mg(SO4)2·4H2O) generates local stresses exceeding 28 MPa, acting as a key driver for surface scaling and micro-cracking in marine environments.

2.3. Coupled Corrosion of Magnesium Chloride and Magnesium Sulfate

2.3.1. Mechanisms of Coupled Corrosion

2.3.2. Modeling Analysis of Coupled Corrosion

3. Anti-Corrosion Measures

3.1. Material Anti-Corrosion Design

3.2. Interface Protection Strategies

3.3. Anti-Corrosion Cementitious Materials

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Magnesium salts environments multi-component cation coupling damage mechanism. Concrete damage under magnesium salts action is a coupled reaction process among various cations, Cl− migrates into the interior of concrete by diffusion, capillary suction, and electromigration, combines with the AFm and C-S-H phase to form Friedel’s salt, destabilizes the passivation film on steel rebars and causes local pitting corrosion. SO42− reacts with Ca2+ and Al3+ in the pores to produce gypsum and ettringite, a kind of expansive hydration product that produces expansive stress and propagates cracks. Mg2+ reacts with CH and causes the decalcification transformation of C-S-H into non-cementitious M-S-H, destroying the strength skeleton. In the presence of different cations, the destruction effect will be strengthened by the “fixation–displacement–releasing” cyclic dynamic changes among them and positive feedback between crack development and penetration.

- (2)

- The spatial-temporal development of ion controls the damage pattern. In multi-salt environments, the spatial distribution and sequence of time of the ions controls the mode of deterioration, i.e., Cl− locates at the deepest penetrating front, SO42− concentrates at the middle layer of concrete as an expansive product, while Mg2+ is mainly located at the concrete surface as Mg(OH)2 and promotes decalcification and M-S-H phases. Moreover, together with the effects of the wet–dry cycle, salt crystallization/thawing stress, and initial cracks, the coupled physicochemical damage is triggered, which has nonlinearity and coupling characteristics. Different model frameworks based on diffusion-reaction equation (D-R), Nernst-Planck-Poisson (NPP), phase field method (PFM) or multiphysical field method (such as TCTD) have been proposed for quantitative description of coupled mechanisms between ion migration, binding/substitution reactions with mineral particles, and pore-crack evolution.

- (3)

- Hierarchical and synergetic material strategies. The measures for mitigating magnesium sulfate corrosion damage based on materials have hierarchically interacted and produced a synergetic effect. Taking mineral admixture as an example, ultrafine fly ash, metakaolin, and ground granulated blast furnace slag can not only reduce ion diffusion rate but also improve C-S-H gel stability by pozzolanic reaction (pozzolanic effect) and fine pore structure. But attention must be paid to the proportion of mineral admixture and the total alkali degree of the system so that adverse change caused by Ca/Si ratio is avoided. For functional admixtures with dual functions of hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity, and anti-corrosion agents, such as amine and nitrite corrosion inhibitors, they can effectively inhibit SO42− exudation amount and increase the anti-corrosion potential value of reinforcement. In addition, the indirect way of increasing fiber dosage and decreasing W/B ratio can block crack connectivity and reduce ion migration speed.

- (4)

- Surface/interface protection and improvement of cementitious matrix. The high-density surface coating (polyurethane, epoxy, acrylic, and nanocomposite coatings), as well as some types of water-repellent or crystallization admixtures, can effectively block surface water invasion and ion migration rates; CSA, PAC, modified polymer, or nanocomposite binder with functional groups can effectively reduce porosity and change the hydration products to resist the attack from SO42−/Mg2+.

- (5)

- Based on the complex degradation mechanisms, practical durability design in magnesium-rich environments should prioritize material optimization. Specifically, the incorporation of Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs), such as fly ash or silica fume, is highly recommended. These materials consume calcium hydroxide to mitigate M-S-H formation while refining the pore structure to slow ion diffusion. Furthermore, maintaining a low water-to-binder ratio and ensuring adequate curing are critical to creating a dense surface skin that acts as the primary barrier against magnesium and chloride penetration. Finally, durability assessment must transition from single-salt models to multi-ion coupling frameworks to avoid underestimating the structural service life.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, Y.; Martin, R.-P.; Omikrine Metalssi, O.; Fen-Chong, T.; Dangla, P. Pore Size Analyses of Cement Paste Exposed to External Sulfate Attack and Delayed Ettringite Formation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 123, 105766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Leung, C.K.Y. A Coupled Diffusion-Mechanical Model with Boundary Element Method to Predict Concrete Cover Cracking Due to Steel Corrosion. Corros. Sci. 2017, 126, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Miao, C.; Bullard, J.W. A Model of Phase Stability, Microstructure and Properties during Leaching of Portland Cement Binders. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 49, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Sun, W.; Scrivener, K. Mechanism of Expansion of Mortars Immersed in Sodium Sulfate Solutions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 43, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, K.; Justnes, H. The Effect of Sea Water on the Phase Assemblage of Hydrated Cement Paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xiong, R.; Guan, B.W. Fatigue Damage Property of Cement Concrete under Magnesium Sulfate Corrosion Condition. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 638–640, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehdi, M.L.; Suleiman, A.R.; Soliman, A.M. Investigation of Concrete Exposed to Dual Sulfate Attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 64, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthulingam, S.; Rao, B.N. Non-Uniform Time-to-Corrosion Initiation in Steel Reinforced Concrete under Chloride Environment. Corros. Sci. 2014, 82, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Study on Chloride Ion Transport Mechanism and Service Life Prediction of Coastal Concrete Structures under Multi-Factor Coupling. Jinan Univ. 2024, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, H. Pore Structure and Chloride Permeability of Concrete Containing Nano-Particles for Pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Shams, M.A.; Bheel, N.; Almaliki, A.H.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Dodo, Y.A.; Benjeddou, O. A Review on Chloride Induced Corrosion in Reinforced Concrete Structures: Lab and in Situ Investigation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 37252–37271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DorMohammadi, H.; Pang, Q.; Murkute, P.; Árnadóttir, L.; Isgor, O.B. Investigation of Chloride-Induced Depassivation of Iron in Alkaline Media by Reactive Force Field Molecular Dynamics. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2019, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Sun, M. Effect of Sulfate Attack on the Expansion Behavior of Cement-Treated Aggregates. Materials 2024, 17, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Lothenbach, B.; Le Goff, F.; Pochard, I.; Dauzères, A. Effect of Magnesium on Calcium Silicate Hydrate (C-S-H). Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 97, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Li, T.; Yang, H. Research on the Critical Chloride Content of Reinforcement Corrosion in Marine Concrete—A Review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shen, X.; Šavija, B.; Meng, Z.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Sepasgozar, S.; Schlangen, E. Numerical Study of Interactive Ingress of Calcium Leaching, Chloride Transport and Multi-Ions Coupling in Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 165, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Feng, P.; Lyu, K.; Liu, J. A Novel Method for Assessing C-S-H ChlorideAdsorption in Cement Pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Shi, M.; Fan, H.; Cui, J.; Xie, F. The Influence of Multiple Combined Chemical Attack on Cast-in-Situ Concrete: Deformation, Mechanical Development and Mechanisms. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 251, 118988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-L.; Dai, J.-G.; Sun, X.-Y.; Zhang, X.-L. Characteristics of Concrete Cracks and Their Influence on Chloride Penetration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 107, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Wang, L. Combined Effect of Water and Sustained Compressive Loading on Chloride Penetration into Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Kim, D.; Cho, S.; Kim, M.O. Advancements in Surface Coatings and Inspection Technologies for Extending the Service Life of Concrete Structures in Marine Environments: A Critical Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omikrine Metalssi, O.; Quiertant, M.; Jabbour, M.; Baroghel-Bouny, V. New Methods for Assessing External Sulfate Attack on Cement-Based Specimens. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.; Georget, F.; Scrivener, K. Unravelling Chloride Transport/Microstructure Relationships for Blended-Cement Pastes with the Mini-Migration Method. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Beushausen, H. Durability, Service Life Prediction, and Modelling for Reinforced Concrete Structures—Review and Critique. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Transport Model of Chloride Ions in Concrete under Loads and Drying-Wetting Cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, G.R.; Andrade, C.; Alonso, C.; Borba, J.C., Jr.; Padilha, M., Jr. Durability of Concrete Structures in Marine Atmosphere Zones—The Use of Chloride Deposition Rate on the Wet Candle as an Environmental Indicator. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, J. Coupling Effect of Corrosion Damage on Chloride Ions Diffusion in Cement Based Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyl, D.; Rashetnia, R.; Seppänen, A.; Pour-Ghaz, M. Can Electrical Resistance Tomography Be Used for Imaging Unsaturated Moisture Flow in Cement-Based Materials with Discrete Cracks? Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 91, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-W.; Kwon, S.-J. Effects of Cold Joint and Loading Conditions on Chloride Diffusion in Concrete Containing GGBFS. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 115, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z. Water Absorption and Chloride Diffusivity of Concrete under the Coupling Effect of Uniaxial Compressive Load and Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 209, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Zhou, M.; Li, F.; Niu, D. Chloride Ion Transport in Coral Aggregate Concrete Subjected to Coupled Erosion by Sulfate and Chloride Salts in Drying-Wetting Cycles; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, S.; Wilson, W.; Georget, F.; Maraghechi, H.; Kazemi-Kamyab, H.; Sun, W.; Scrivener, K. Quantification Methods for Chloride Binding in Portland Cement and Limestone Systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 125, 105864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steen, C.; Nasser, H.; Verstrynge, E.; Wevers, M. Acoustic Emission Source Characterisation of Chloride-Induced Corrosion Damage in Reinforced Concrete. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 21, 1266–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepenar, I. Chloride-Induced Corrosion Damage of Reinforced Concrete Structures: Case Studies and Laboratory Research. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 58, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemstad, P.; Machner, A.; De Weerdt, K. The Effect of Artificial Leaching with HCl on Chloride Binding in Ordinary Portland Cement Paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 130, 105976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lu, Z. Effect of Sulfate Solution Concentration on the Deterioration Mechanism and Physical Properties of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.-J.; Shan, Z.-Q.; Miao, L.; Tang, Y.-J.; Zuo, X.-B.; Wen, X.-D. Finite Element Analysis on the Diffusion-Reaction-Damage Behavior in Concrete Subjected to Sodium Sulfate Attack. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 137, 106278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Dang, Y.; Shi, X. New Insights into How MgCl2 Deteriorates Portland Cement Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 120, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z. Effect of Physical and Chemical Sulfate Attack on Performance Degradation of Concrete under Different Conditions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 745, 137254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangat, P.S.; Ojedokun, O.O. Bound Chloride Ingress in Alkali Activated Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 212, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, M.; Cohen, M.D.; Olek, J. Mechanism of Sulfate Attack: A Fresh Look. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothenbach, B.; Nied, D.; L’Hôpital, E.; Achiedo, G.; Dauzères, A. Magnesium and Calcium Silicate Hydrates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 77, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Elakneswaran, Y.; Nawa, T. Electrostatic Properties of C-S-H and C-A-S-H for Predicting Calcium and Chloride Adsorption. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121, 104109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, R.J.; Scherer, G.W. Hydration and Crystallization Pressure of Sodium Sulfate: A Critical Review. MRS Proc. 2002, 712, II2-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, G.W. Stress from Crystallization of Salt. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaulow, N.; Sahu, S. Mechanism of Concrete Deterioration Due to Salt Crystallization. Mater. Charact. 2004, 53, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-J.; Liu, P.-Q.; Wu, C.-L.; Wang, K. Effect of Dry–Wet Cycle Periods on Properties of Concrete under Sulfate Attack. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, J. Damage Evolution in Cement Mortar Due to Erosion of Sulphate. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 2478–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Z.; Hu, E.; Liu, Z. Mechanical and Damage Characteristics Study of Concrete under Repeated Sulfate Erosion. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 109, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, U.H.; De Weerdt, K.; Geiker, M.R. Elemental Zonation in Marine Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 85, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, H.; Qiu, G. Research Progress on Coupled Chloride–Sulfate Erosion Mechanism, Modeling, and Numerical Simulation of Concrete. Bull. Silic. 2024, 43, 1001–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, T.; Liu, Y. Corrosion Behavior of Steel Bar and Corrosive Cracking of Concrete Induced by Magnesium-Sulfate-Chloride Ions. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2016, 14, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J. Research Progress on Concrete Durability under Chloride Erosion and Multi-Factor Coupling. China Build. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 28, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, G.; Yang, H.; Li, Y. Numerical Simulation on Diffusion-Reaction Behavior of Concrete Under Sulfate-Chloride Coupled Attack; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, L.; Bindiganavile, V.; Yi, C. Coupled Models to Describe the Combined Diffusion-Reaction Behaviour of Chloride and Sulphate Ions in Cement-Based Systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Gao, W.; Feng, Y.; Castel, A.; Chen, X.; Liu, A. On the Competitive Antagonism Effect in Combined Chloride-Sulfate Attack: A Numerical Exploration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 144, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Mo, R.; Zhou, X.; Xu, J.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, T. A Chemo-Thermo-Damage-Transport Model for Concrete Subjected to Combined Chloride-Sulfate Attack Considering the Effect of Calcium Leaching. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 306, 124918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, J.; Bindiganavile, V.; Yi, C.; Shi, C.; Hu, X. Time and Spatially Dependent Transient Competitive Antagonism during the 2-D Diffusion-Reaction of Combined Chloride-Sulphate Attack upon Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 154, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Mahadevan, S.; Meeussen, J.C.L.; van der Sloot, H.; Kosson, D.S. Numerical Simulation of Cementitious Materials Degradation under External Sulfate Attack. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Pan, Z.; Ma, R.; Chen, A. A Multi-Phase Multi-Species Phase Field Model for Non-Uniform Corrosion and Chloride Removal in Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Pan, Z.; Chen, A. Phase Field Modeling of Concrete Cracking for Non-Uniform Corrosion of Rebar. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 121, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, L. Peridynamic Investigation of Chloride Diffusion in Concrete under Typical Environmental Factors. Ocean Eng. 2021, 239, 109770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Guo, W.; Chen, D.; Guo, L.; Cai, B.; Ye, T. Mechanistic Modeling for Coupled Chloride-Sulfate Attack in Cement-Based Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 455, 139231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Arteaga, E.; Bressolette, P.; Chateauneuf, A.; Sánchez-Silva, M. Probabilistic Lifetime Assessment of RC Structures under Coupled Corrosion–Fatigue Deterioration Processes. Struct. Saf. 2009, 31, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Study on the Corrosion Mechanism of Cast-in-Situ Concrete Modified by Calcined Metakaolin under Composite Salt Attack. Tarim Univ. 2024, 4, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraghechi, H.; Avet, F.; Wong, H.; Kamyab, H.; Scrivener, K. Performance of Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3) with Various Kaolinite Contents with Respect to Chloride Transport. Mater. Struct. 2018, 51, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibara, H.; Hooton, R.D.; Thomas, M.D.A.; Stanish, K. Influence of the C/S and C/A Ratios of Hydration Products on the Chloride Ion Binding Capacity of Lime-SF and Lime-MK Mixtures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, K.; Justnes, H.; Geiker, M.R. Changes in the Phase Assemblage of Concrete Exposed to Sea Water. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 47, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; He, W.; Zhou, X. Study on the Resistance of Concrete to High-Concentration Sulfate Attack: A Case Study in Jinyan Bridge. Materials 2024, 17, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, Z.; Pang, J. A Research on Durability Degradation of Mineral Admixture Concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, W.; Cui, H.; Zhou, J. Long-Term Effectiveness of Carbonation Resistance of Concrete Treated with Nano-SiO2 Modified Polymer Coatings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 201, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Xu, T.; Hou, D.; Zhao, E.; Hua, X.; Han, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Superhydrophobic Anticorrosive Coating for Concrete through In-Situ Bionic Induction and Gradient Mineralization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Qu, X.; Li, J. Application of Polymer Modified Cementitious Coatings (PCCs) for Impermeability Enhancement of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhao, P.; Gong, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Lu, L. Investigation on the Mechanical Properties of CSA Cement-Based Coating and Its Application. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.Z.; Mou, B.; Shang, H.S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Ren, J. Mechanical and interface bonding properties of epoxy resin reinforced Portland cement repairing mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 264, 120715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.L.; Tu, Z.; Shang, X.P.; Xu, C.J.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, H.; Hu, J.; Xie, S.; Li, C.M.; Zhang, T.T. Development of Sustainable Alkali-Activated Red Mud Composite Cement: Mechanical Properties, Hydration Mechanisms, and Environmental Benefits. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 499, 144089. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Shi, Z.; Shi, C.; Ling, T.-C.; Li, N. A Review on Concrete Surface Treatment Part I: Types and Mechanisms. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.; Sobolev, K. Nanotechnology in Concrete—A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2060–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Specific Deterioration Mechanism | Key Chemo-Physical Process | Corresponding Section |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Intrusion | Multi-Species Transport Coupling (Mg2+-SO42−-Cl− Interaction) |

| Section 2.3.1 (Transport Models) |

| II. Reaction |

|

| Section 2.1 and Section 2.2 (Reaction Pathways) |

| III. Damage | Chemo-Mechanical Damage Evolution |

| Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.3.2 (Damage Models) |

| IV. Response | Synergistic Protection and Prediction |

| Section 3 and Section 4 (Strategies and Outlook) |

| Exposure Zone | Structural Examples | Chloride Ion Transport Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Submersion Zone | Structures Submerged in Seawater | Permeation, Diffusion, Electrochemical Migration | [18,22,24] |

| Tidal Zone of Marine Structures | Components in the Upper and Lower Tidal Zones | Capillary Absorption, Diffusion | [17,21,25] |

| Splash Zone | Wave-Impacted Structural Components | Capillary Absorption, Diffusion | [9,25,26] |

| Atmospheric Zone of Marine Structures | Coastal Structures Not Directly Exposed to Seawater | Capillary Absorption | [9,26] |

| Aggressive Medium | Ions Involved in Primary Reactions | Key Reaction Products | Dominant Damage Mechanism | Characteristics of Structural Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2SO4 | SO42− | AFt, Gypsum | Expansion and Crystallization: Formation of expansive products and salt crystallization pressure | Cracking: Surface expansion, spalling, and micro-cracking | [36,37] |

| MgCl2 | Cl−, SO42− | Friedel’s Salt, Mg(OH)2, M-S-H | Decalcification and Binding: Transformation of C-S-H to M-S-H; Reaction of Cl− to form Friedel’s salt | Pore Coarsening: Increased porosity, surface softening, and pitting corrosion of steel | [14,27,38] |

| MgSO4 | SO42−, Mg2+ | Mg(OH)2, M-S-H, AFt | Coupled Attack: Simultaneous decalcification of C-S-H and formation of expansive products | Disintegration: Loss of binder cohesion (mushy surface) combined with internal cracking | [1,39] |

| Modeling Framework | Strengths | Limitations | Applicability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Models (Diffusion-Reaction) | High computational efficiency; Simple inputs; Analytical solutions available | Ignores thermodynamic equilibrium; Low accuracy for multi-ion coupling | Rapid service life estimation for simple geometries | [55,64] |

| Multiphysics Models (PNP-Damage) | High accuracy; Rigorous theoretical basis; Captures electric field coupling | Requires extensive input parameters; Sensitive to boundary conditions. | Detailed durability design for critical infrastructure | [56] |

| Chemo-Mechanical Models (Phase-Field) | Visually simulates crack propagation; Captures “corrosion-cracking” feedback | Extremely high computational cost; Difficult to simulate large-scale structures | Theoretical research and mechanism verification | [57,61] |

| Numerical Schemes (FEM/FDM) | Flexible for complex geometries; Mature commercial software support (e.g., COMSOL) | Mesh-dependency issues; Long-term validation data is often lacking | Engineering applications with complex boundary conditions | [37,58] |

| Category of Measures | Primary Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral Admixtures (e.g., Fly Ash, Slag, Silica Fume, etc.) | Dilution effect and pozzolanic reaction to refine pore structure and reduce ion diffusion rate | Cost-effective, utilizes industrial by-products; significantly reduces Cl− diffusion and SO42− reactions | Limited reactivity, lower early-age strength; restricted inhibition of Mg2+-induced decalcification |

| Functional Cementitious Materials (e.g., CSA, Magnesium-Based Binders, etc.) | Rapid formation of ettringite/other non-expansive products to mitigate sulfate attack; strong Mg2+ binding capacity | Highly targeted; significantly enhances resistance to SO42− and Mg2+ attack | Relatively high cost; limited compatibility with ordinary cement systems |

| Surface Protectives/Coatings (Hydrophobic Agents, Penetrating Crystallization Agents, Polymer Coatings) | Barrier effect to reduce water and ion penetration; some coatings possess self-healing properties | Easy to apply, rapid effect; particularly effective against Cl−-induced corrosion | Limited durability; potential for cracking or delamination; requires periodic maintenance |

| Composite Material Systems (Nanomaterials, Graphene, Fiber-Reinforced Systems) | Enhances microstructural density, improves mechanical toughness, adsorbs/fixes part of the aggressive ions | Simultaneously improves mechanical performance and durability; suitable for complex coupled corrosion environments | High cost; large-scale application remains limited |

| Structural and Design Optimization (High-Performance Concrete, Low Water-to-Binder Ratio, Protective Layer Thickness Design) | Reduces ion transport pathways and penetration efficiency through design measures | Can be combined with material optimization for synergistic effects; high engineering feasibility | Requires optimization based on environmental conditions; still limited under extreme environments |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shang, X.; Yue, X.; Pan, L.; Dong, J. Mechanisms and Protection Strategies for Concrete Degradation Under Magnesium Salt Environment: A Review. Buildings 2026, 16, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020264

Shang X, Yue X, Pan L, Dong J. Mechanisms and Protection Strategies for Concrete Degradation Under Magnesium Salt Environment: A Review. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020264

Chicago/Turabian StyleShang, Xiaopeng, Xuetao Yue, Lin Pan, and Jingliang Dong. 2026. "Mechanisms and Protection Strategies for Concrete Degradation Under Magnesium Salt Environment: A Review" Buildings 16, no. 2: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020264

APA StyleShang, X., Yue, X., Pan, L., & Dong, J. (2026). Mechanisms and Protection Strategies for Concrete Degradation Under Magnesium Salt Environment: A Review. Buildings, 16(2), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020264