Seismic Performance of the Full-Scale Prefabricated Concrete Column Connected in Half-Height: Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

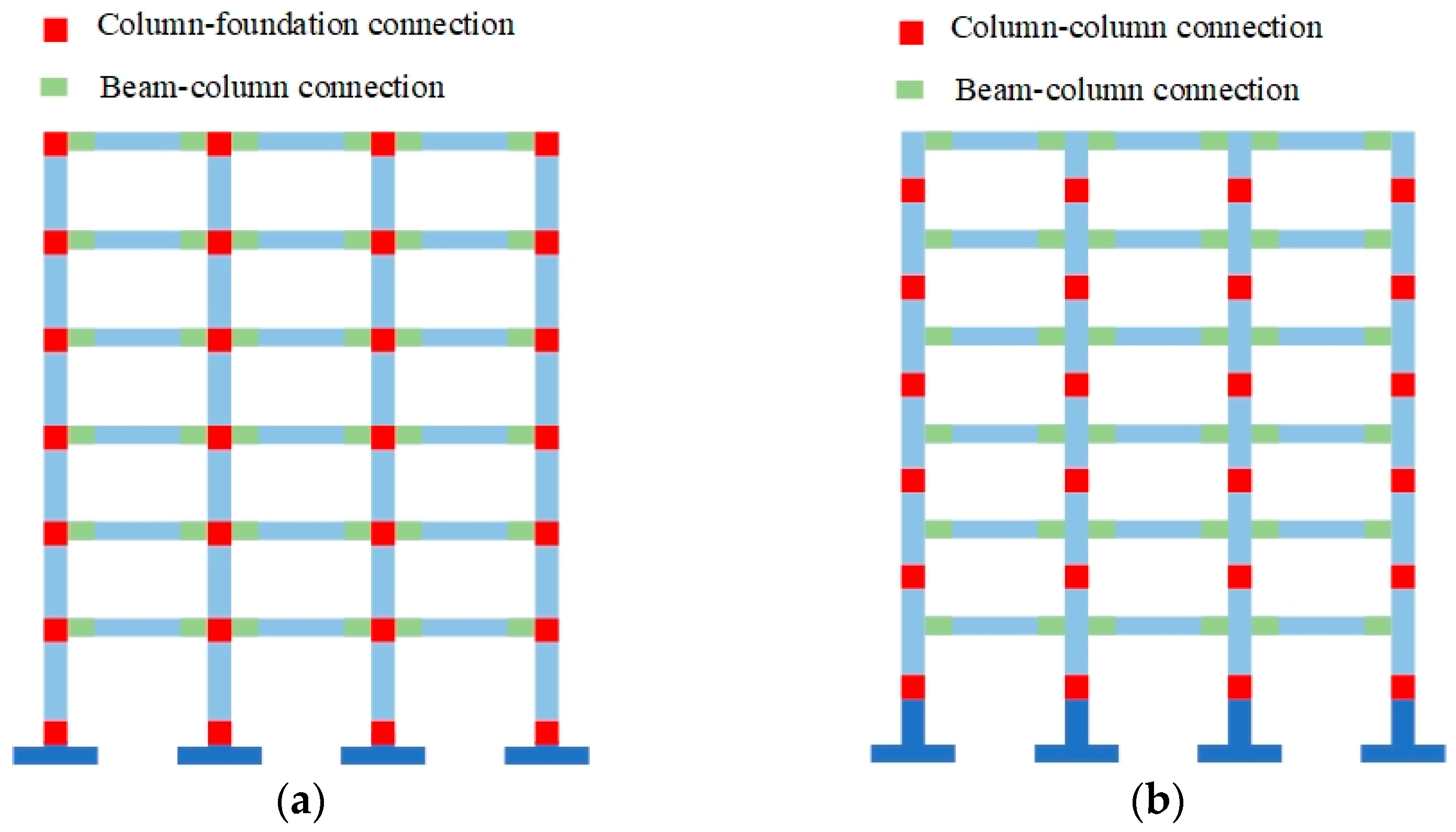

2.1. Connection Design

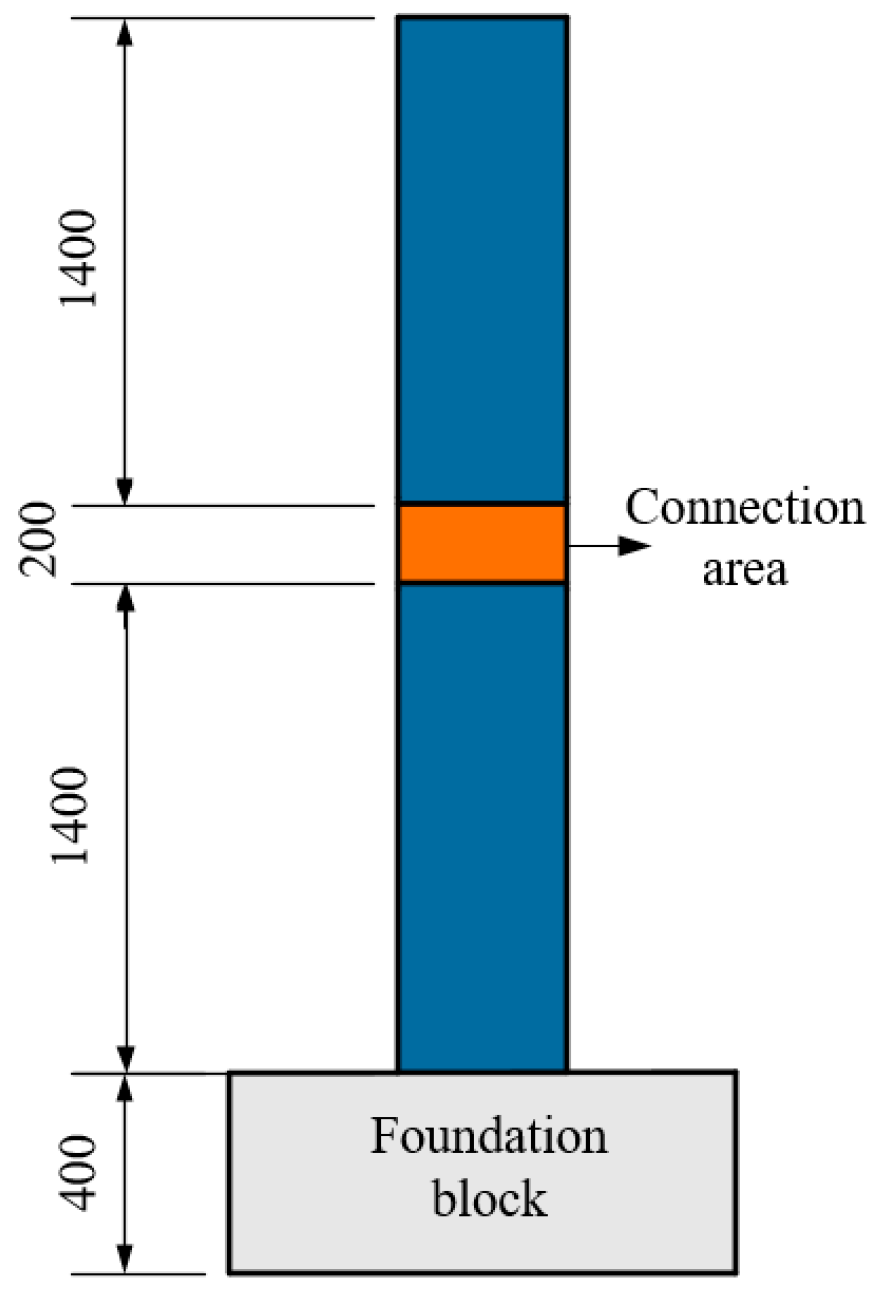

2.2. Test Specimen

2.3. Material Properties

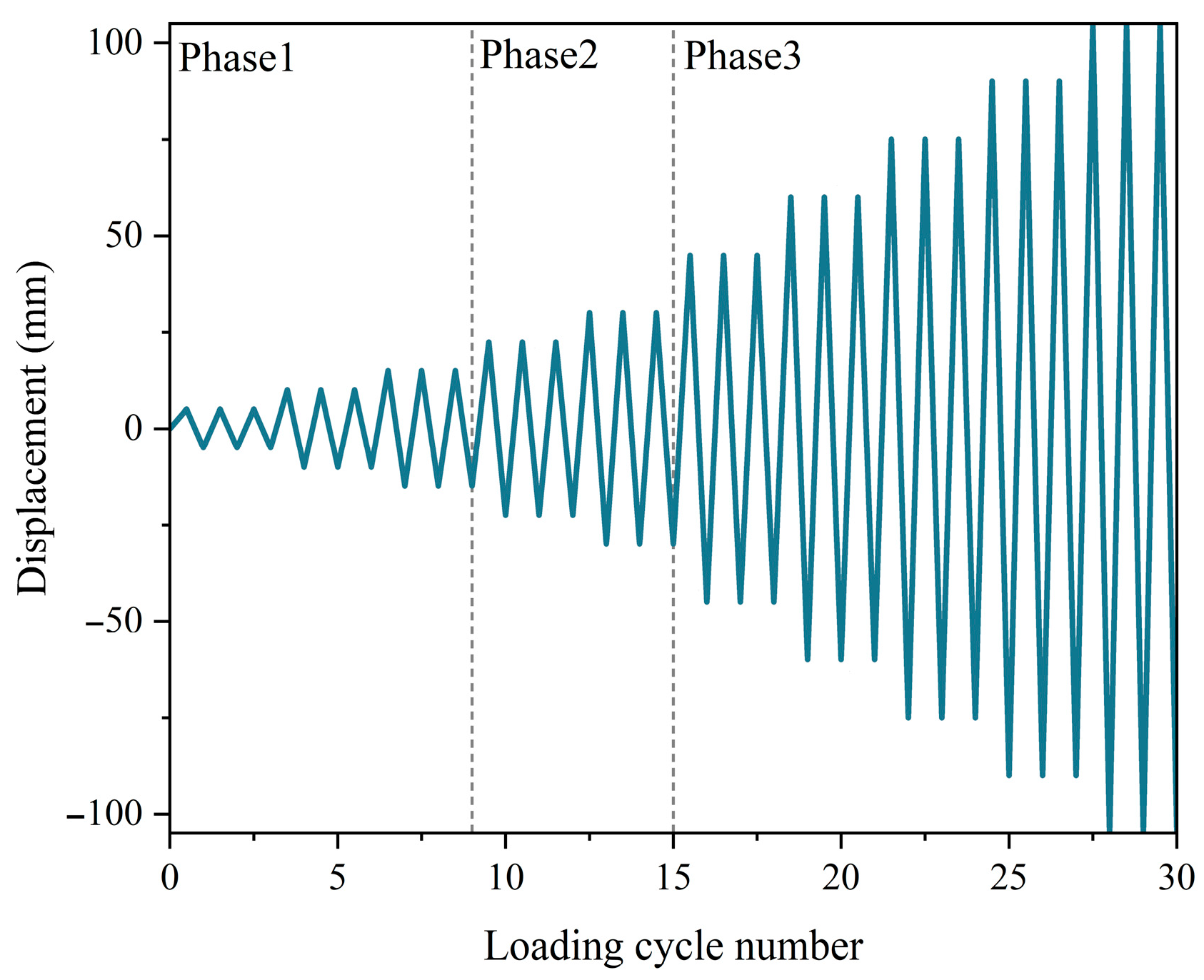

2.4. Test Setup and Instrumentation

3. Experimental Results and Discussions

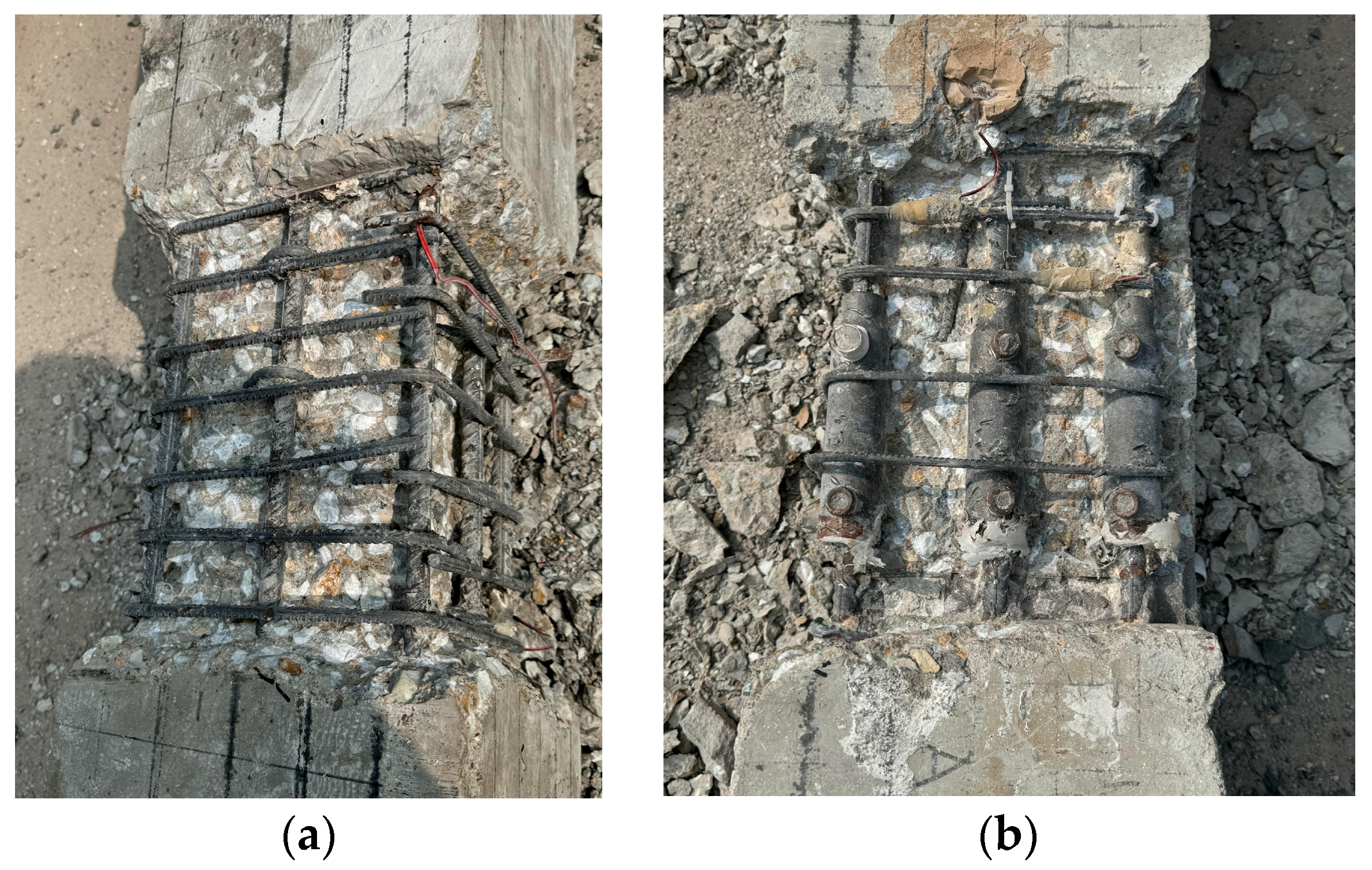

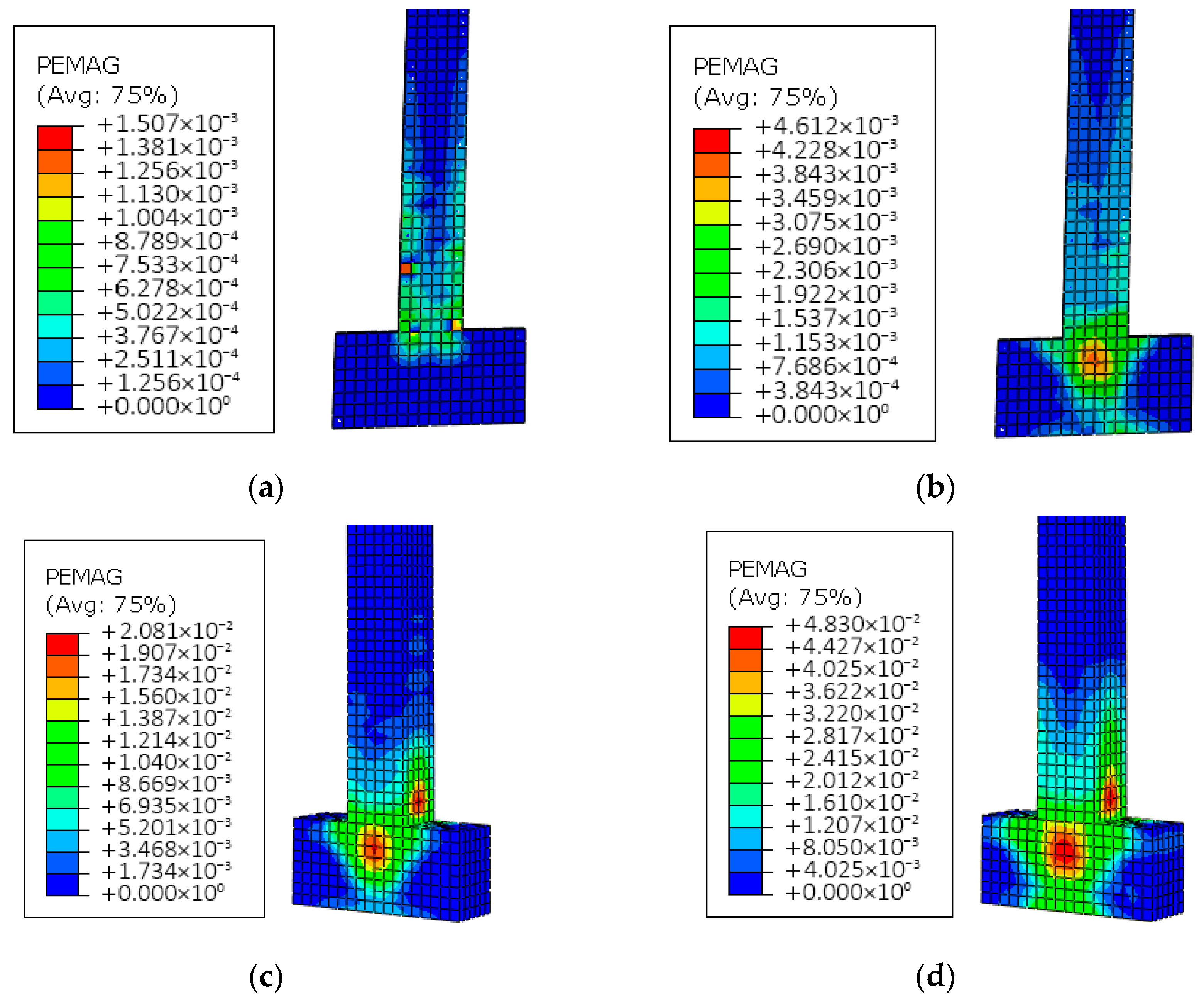

3.1. Damage Progression

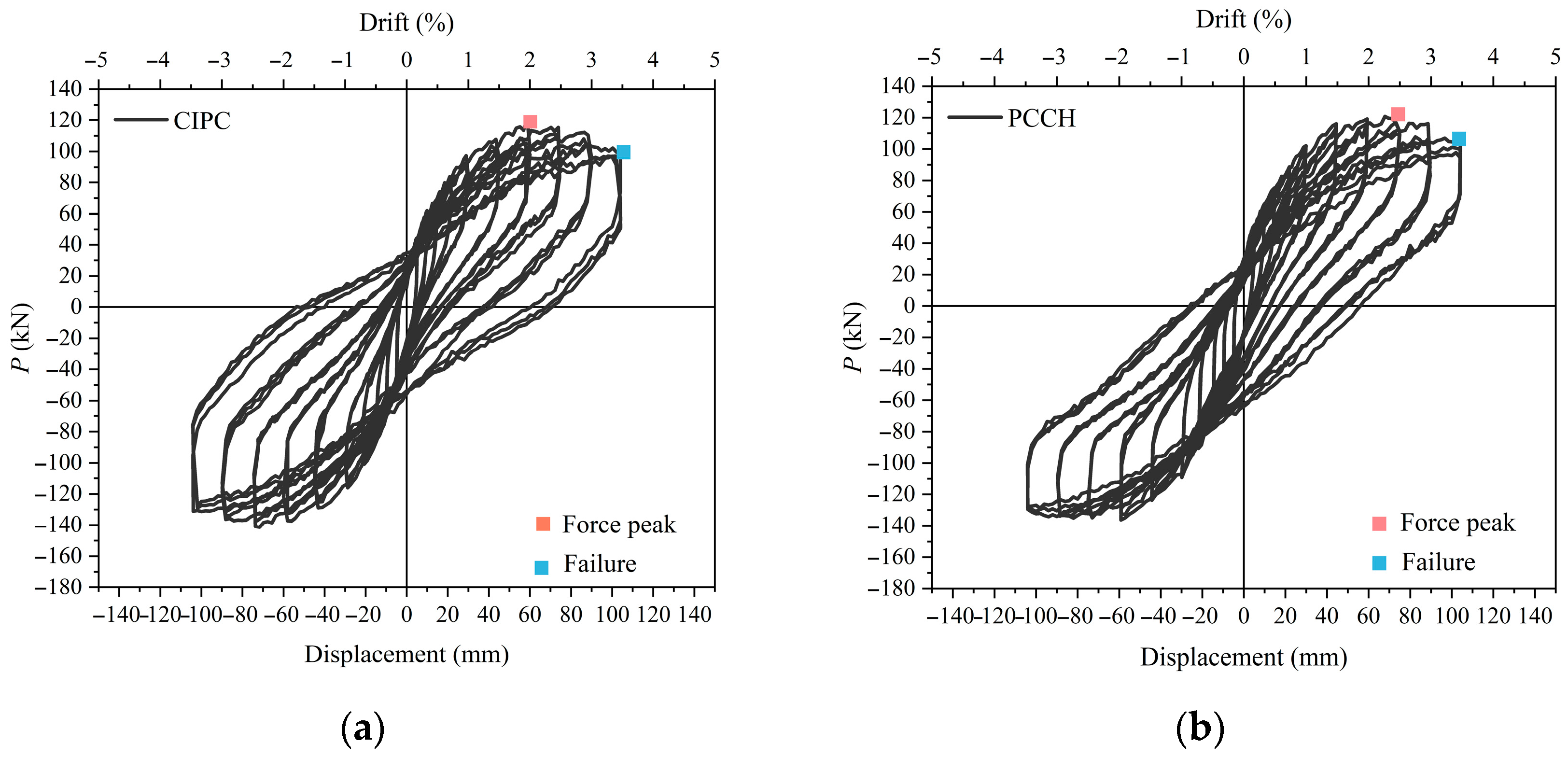

3.2. Hysteretic Response

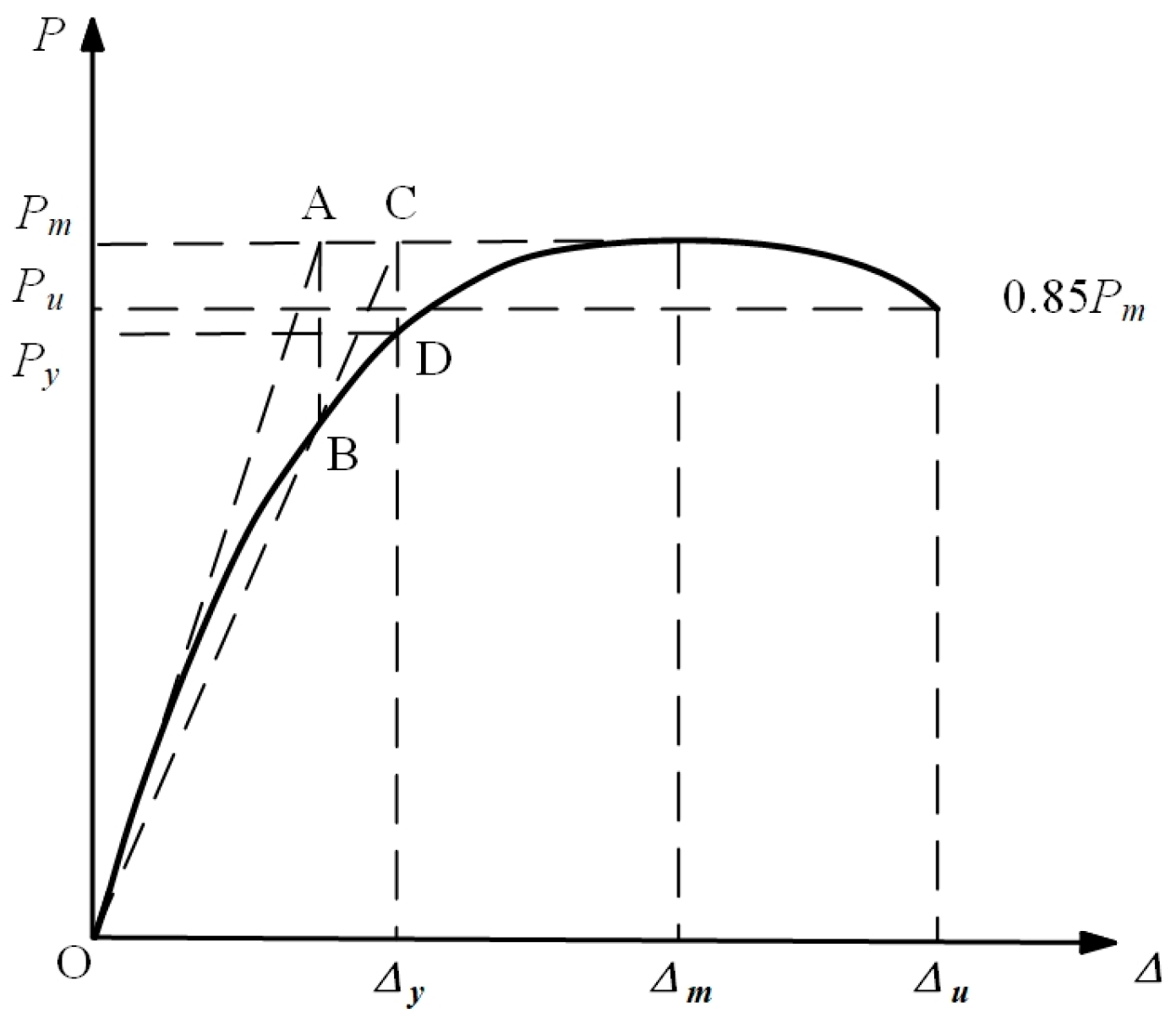

3.3. Skeleton Curve

3.4. Ductility

3.5. Secant Stiffness Deterioration

3.6. Energy Dissipation

3.7. Comprehensive Seismic Response

4. Numerical Analysis

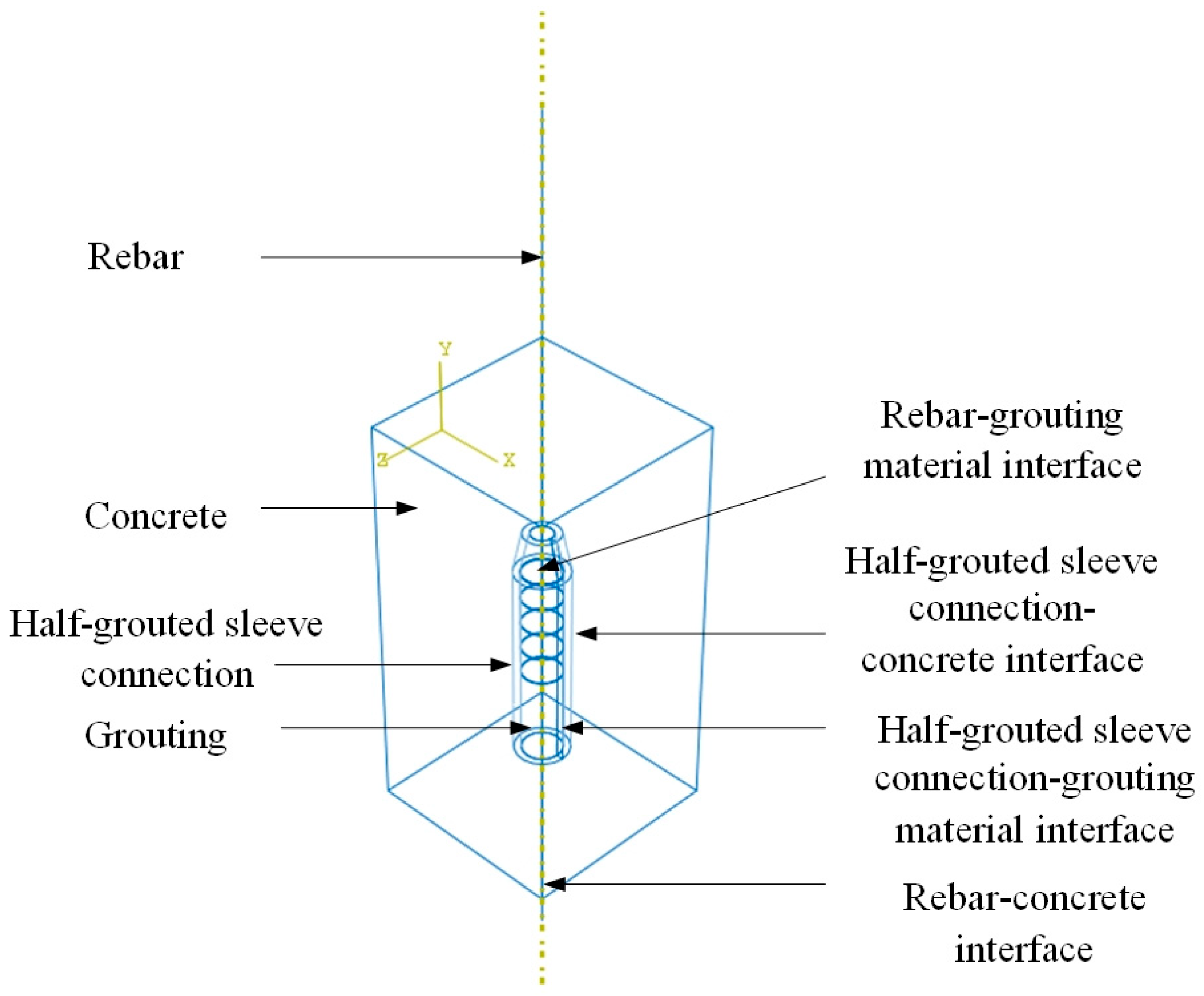

4.1. Model Description

4.2. Material Constitutive Selection

4.2.1. Concrete

4.2.2. Reinforcement and Half-Grouted Sleeve Connection

4.3. Boundary Condition Settings

4.4. Model Validation

4.5. Simplified Calculation of Shear Bearing Capacity

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The cash-in-place column and the half-height prefabricated column exhibited flexural failure characteristics. Smaller crack widths and less localized damage under the same displacement were the results of the grouted-sleeve connection’s increased stiffness. No observable bond–slip failure occurred in the sleeve connection.

- (2)

- The repeated opening and closing of these cracks observed at the grouting-concrete interface aggravated bond-slip, intensifying the pinching effect in hysteretic response. The cumulative energy dissipation of the prefabricated column was approximately 5.61% lower than that of the cast-in-place specimen.

- (3)

- The precast column showed slight decreases in ultimate bearing (1.45%), capacity, and energy dissipation (5.61%) when compared to cast-in-place columns; nevertheless, their initial stiffness and ductility coefficient rose by 8.88% and 9.09%, respectively. This indicates that the prefabricated concrete column connected in half-height is reliable.

- (4)

- Using the full constitutive model of the half-grouted sleeve connection with concrete cover to address convergence challenges associated with sleeve-connected columns. The numerical results generally aligned well with the experimental data and had strong predictive power for damage localization and failure mechanisms.

- (5)

- The formula for calculating shear bearing capacity can be used to determine the failure mode. It serves as a guide for simulating whether, in extreme situations, the specimen connected in various positions experiences brittle shear failure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIPC | Cast-in-place column |

| PCCH | Prefabricated column connected at half-height |

References

- Zhao, S.Y.; Qu, X.R.; Zhao, X.J. The carbon emissions of prefabricated building in urban renewal: Assessment and emission reduction path. Energy Build. 2025, 341, 115830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Ding, M.T.; Qiu, J.A.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.B.; Sun, D. Severity of earthquake disasters triggered by ms ≥ 5.0 events: Retrospective analysis of 288 cases in China (1991–2020). Nat. Hazard. 2025, 121, 15993–16011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parastesh, H.; Hajirasouliha, I.; Ramezani, R. A new ductile moment-resisting connection for prefabricated concrete frames in seismic regions: An experimental investigation. Eng. Struct. 2014, 70, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaygua, B.; Sánchez-Garrido, A.J.; Yepes, V. A systematic review of seismic-resistant prefabricated concrete buildings. Structures 2023, 58, 105598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, M.; Praticò, L.; Savoia, M. PRESSAFE-DISP: A method for the fast in-plane seismic assessment of existing prefabricated RC buildings after the Emilia earthquake of May 2012. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 2751–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghini, F.; Ongaretto, E.; Ligabue, V.; Savoia, M.; Tullini, N. Observational failure analysis of prefabricated buildings after the 2012 Emilia earthquakes. Earthq. Struct. 2016, 11, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Yang, C.; Fan, W.; Sun, C.; Guo, W. Hysteresis characteristics of multi-segment prefabricated columns with ultra-high performance concrete-based grouted sleeve connections: An experimental and analytical approach. Eng. Struct. 2025, 322, 119157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Chen, J.J.; Shan, K.; Wu, Y.F. Seismic performance of corroded prefabricated column-footing joint with grouted splice sleeve connection: Experiment and simulation. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.T.; Wang, Z.Y.; Xu, C.S.; Du, X.L. Influence of axial compression ratio on the seismic performance of prefabricated columns with grouted sleeve connections. J. Struct. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Xiao, J.Z. Simulation on seismic performance of the post-fire prefabricated concrete column with grouted sleeve connections. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 3299–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pan, J.L.; Guo, L. Mechanical performance of prefabricated RC columns with grouted sleeve connections. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullini, N.; Minghini, F. Grouted sleeve connections used in prefabricated reinforced concrete construction–experimental investigation of a column-to-column joint. Eng. Struct. 2016, 127, 784–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Abruzzese, D.; Milani, G.; Li, S. Influence of internal defects of semi grouted sleeve connections on the seismic performance of prefabricated monolithic concrete columns. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.Y.; Tao, Y.C.; Yuan, L.L.; Jin, Z.F.; Zhao, W.J. Seismic performance of new detailing RCS connection with different axial compression ratio and FBP thickness. Structures 2024, 68, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Qu, H.Y.; Li, T.T.; Wei, H.Y.; Wang, H.; Duan, H.L.; Jiang, H.X. Quasi-static cyclic tests of prefabricated bridge columns with different connection details for high seismic zones. Eng. Struct. 2018, 158, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.J.; Xu, W.B.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.J.; Du, X.L.; Fang, R. Seismic performance of prefabricated concrete columns with grouted sleeve connections, and a deformation-capacity estimation method. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 55, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Zhou, B.B.; Cai, J.G.; Lee, D.S.H.; Deng, X.W.; Feng, J. Experimental study on seismic behavior of prefabricated concrete column with grouted sleeve connections considering ratios of longitudinal reinforcement and stirrups. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 16, 6077–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompa, D.V.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Ductility considerations for mechanical reinforcement couplers. Structures 2017, 12, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.X.; Yu, W.M.; Luo, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, X. Experimental study on seismic behavior of prefabricated concrete circular section column with grouted sleeve. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, Z.B.; Saiidi, M.S.; Sanders, D.H. Seismic performance of prefabricated columns with mechanically spliced column-footing connections. ACI Struct. J. 2014, 111, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, M.J.; Pantelides, C.P. Seismic analysis of prefabricated concrete bridge columns connected with grouted splice sleeve connectors. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 143, 04016176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.S.; Wang, J.J.; Li, Z.X.; Liang, X. Effect of reinforcement grade and concrete strength on seismic performance of reinforced concrete bridge piers. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z. Equivalent stress-strain model of half grouted sleeve connection under monotonic and repeated loads: Experiment and preliminary application. Eng. Struct. 2022, 260, 114247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- GB/T50011-2010; Code for Seismic Design of Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- ISO6892-1; Metallic Materials-Tensile Testing-Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. International Organization for Standardization: ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Method of Testing Cements-Determination of Strength (ISO 679:2009). Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- JG/T 408-2019; Cementitious Grout for Coupler of Rebar Splicing. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- JGT 398-2019; The Grouting Coupler for Rebars Splicing. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- Xu, L.; Pan, J.; Cai, J. Seismic Performance of Precast RC and RC/ECC Composite Columns with Grouted Sleeve Connections. Eng. Struct. 2019, 188, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R. Evaluation of ductility of structures and structural assemblages from laboratory testing. Bull. N. Z. Soc. Earthq. 1989, 22, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Peng, T.; Miao, J.; Liu, C.; Ba, G.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, J.; Hou, D.; Liu, Y. Uniaxial tensile behavior of half-grouted sleeve connections with concrete cover after exposure to elevated temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABAQUS. ABAQUS Standard User’s Manual, Version 6.12; Dassault Systems Simulia Corporation: Providence, RI, USA, 2012.

| Specimen Type | Sectional Size (mm) | Height (mm) | n | Concrete Strength | Longitudinal Reinforcement | Stirrups (Stirrups Near Mid-Connection) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIPC | 300 × 300 | 3000 | 0.2 | C35 | 8C16 | B8@100 (B8@50) |

| PCCH | 300 × 300 | 3000 | 0.2 | C35 | 8C16 | B8@100 (B8@50) |

| Material | Diameter (mm) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRB400 | 16 | 400.37 | 551.85 |

| HRB335 | 8 | 346.13 | 433.36 |

| Type | Total Length (mm) | Anchor Length (mm) | Thread Length (mm) | Outer Diameter (mm) | Inner Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTB4Z-16/16 * | 175 | 144 | 29 | 38 | 28 |

| Specimen | Δy (mm) | Δu (mm) | μ |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIPC | 27.8 | 104.0 | 3.74 |

| PCCH | 24.6 | 100.3 | 4.08 |

| Experimental Results | CIPC | PCCH |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate load (kN) | 120.90 | 119.15 |

| Ultimate displacement (mm) | 104.01 | 100.32 |

| Energy dissipation (kN·mm) | 60,462.09 | 57,069.17 |

| Ductility coefficient | 3.74 | 4.08 |

| Initial stiffness (kN/mm) | 9.23 | 10.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, T.; Miao, J.; Zhang, J.; Song, B.; Liu, Y.; Song, S. Seismic Performance of the Full-Scale Prefabricated Concrete Column Connected in Half-Height: Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 4491. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244491

Peng T, Miao J, Zhang J, Song B, Liu Y, Song S. Seismic Performance of the Full-Scale Prefabricated Concrete Column Connected in Half-Height: Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4491. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244491

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Tingting, Jijun Miao, Jiaqi Zhang, Bochen Song, Yanchun Liu, and Sumeng Song. 2025. "Seismic Performance of the Full-Scale Prefabricated Concrete Column Connected in Half-Height: Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4491. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244491

APA StylePeng, T., Miao, J., Zhang, J., Song, B., Liu, Y., & Song, S. (2025). Seismic Performance of the Full-Scale Prefabricated Concrete Column Connected in Half-Height: Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis. Buildings, 15(24), 4491. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244491