1. Introduction

Over the years, architectural education has struggled to make theory-based subjects, like the history of architecture, truly captivating for students. The challenge lies in the sheer volume of factual information learners are expected to memorise, which can make learning feel overwhelming and less inspiring. Architectural heritage conservation and restoration could benefit immensely from immersive VR applications offering realistic and interactive images [

1]. Virtual reality presents a game-changing opportunity in teaching architectural history courses. By offering fully immersive, 360-degree perspectives of historical sites, VR allows learners to engage with architectural details as if they were physically present. Instead of relying solely on textbooks and images, students who use interactive visualisations would develop an improved understanding of a historical site because of their ability to control the learning process and subsequently improve their cognitive map [

2]. VR also addresses logistical challenges, as field trips are often more expensive and time-consuming, making them inaccessible to students. VR bridges this gap by providing an almost real experience without the need to physically travel. As a result of this, many architecture and interior architecture programmes are increasingly incorporating VR to complement or even replace traditional site visits. Aside from being a learning tool, VR plays a crucial role in heritage preservation. By digitally documenting historic sites, VR ensures that architectural history remains accessible for future generations. Furthermore, it greatly enhances engagement and understanding, allowing users to feel as though they are part of the past, creating a powerful tool for both learning and experiencing cultural heritage in a memorable and interactive way [

3].

Emerging technologies like VR have attracted transformative impacts across diverse fields and specialisations through the provision of immersive and interactive experiences that facilitate understanding and exploration. In medical research, for example, VR allows medical personnel to simulate surgeries and understand human anatomy, which has a positive impact on training and patient outcomes [

4]. In behavioural studies, VR creates a controlled environment to study human behaviour with accuracy [

5]. In the field of astronomy, VR allows for the exploration of planets and other celestial bodies to enhance our knowledge of the universe. For architects and designers, the technology also enables them to visualise and test building concepts in 3D and in real time to explore different options and to further optimise various stages of the designs before construction [

6]. In the virtual environment, VR helps to simulate dynamic objects where the scenes and objects can be interacted with by engaging with other senses, such as touch and hearing, to enrich visualisations in the teaching and practice of medicine [

7]. VR creates immersive environments where users interact with 3D reconstructions of historical sites, artefacts, and cultural landmarks (

Figure 1). This makes it a powerful tool for education and preservation [

8]. These applications of VR across disciplines underscore its transformative potential in research, facilitating deeper engagement and discovery across different fields.

The term cultural heritage began to be widely used, and cultural heritage, with its emphasis on the process of inheritance, was used in a large number of international conventions, such as the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, starting with the use of the term cultural heritage in the European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage in 1969. As far as the forms of cultural heritage are concerned, the classification of intangible cultural heritage and tangible cultural heritage has been widely disseminated and has become an essential part of analysing cultural heritage. In addition, the United Nations breaks down cultural heritage into categories such as architectural heritage, artistic and archaeological heritage, oral traditions, historic cities, languages, cultural landscapes, festivals and events, natural sanctuaries, consciousness and beliefs, underwater cultural heritage, music and song, museums, performing arts, movable cultural heritage, traditional medicine, handicrafts, literature, documentary and digital heritage, culinary traditions, cinematic heritage, and traditional sports and games [

5]. Over the years, historical architectural spaces have traditionally relied on methods such as documentation, restoration, and physical conservation for preservation. These techniques are indeed crucial for maintaining the integrity of historical and cultural sites; they limit the extent to which these environments can be engaged with [

10]. VR provides a transformative approach in which users experience historical architectural spaces in an immersive and interactive way [

11]. VR has allowed historical environments to be virtually visited to sustain heritage attractions that might be endangered [

12], making technologies like photogrammetry, 3D modelling, and advanced data management enhance cultural heritage preservation. The technological upgrade of the usage of VR has provided new opportunities for improved education and public engagement, offering an alternative dynamic method to conventional preservation methods.

Historical architectural space represents cultural and historical significance, serving as intermediaries to the past. Traditional methods of preserving historical spaces are essential but limit the public’s interaction and understanding of the environment [

13]. Recent trends in VR technology offer innovative ways of understanding and experiencing historical architecture, exceeding the limitations of physical preservation. VR allows for the virtual reconstruction of historical spaces, enabling users to explore them in an interactive and immersive manner. This approach provides users with a deeper understanding of the spatial qualities, cultural significance, and construction methodologies of heritage sites. The integration of VR into the preservation of historical spaces requires a balance of representation of architectural features and the immersive design of a virtual environment.

Despite the use of VR in various areas of specialisation, the use of the technology in historical architecture remains underutilised. Preservation practices currently in vogue do not leverage the interactive and immersive capability of VR, missing opportunities to enhance public engagement and education [

14]. The use of high-quality VR experiences creates unique challenges. Scholars must balance accuracy and authenticity with engaging design while considering how best to represent architectural details, spatial relationships, and cultural contexts in a digital medium. This study aims to gather authoritative takes from professionals and experts in affiliated fields to gain a thorough understanding of the best practices and potential pitfalls of utilising VR for historical architectural spaces. The findings of the study will have an impact on the future of VR in historical preservation, making cultural heritage sites more accessible and educational for a broader audience. The research aims to achieve the following objectives:

To evaluate the impact of virtual reality on user engagement and educational outcomes when assessing historical architectural spaces.

To point out critical factors that ensure the fidelity and accuracy of VR reconstructions in historical preservation.

To identify challenges and additional considerations faced by researchers in creating VR experiences for historical architecture.

To gather best practices from experts for designing immersive and engaging VR experiences of historical architecture.

2. Literature

As an after-effect of the global pandemic, adoption of VR has risen dramatically, leading to its emergence as one of the foremost information and communication technologies (ICT) in educational reforms. With growing significance for enhancing education quality, VR represents a technological innovation with significant potential. VR is also an effective mode of communication, where students and educators can collaborate over long distances using a networked virtual world as a collaborative space. As the VR medium matures, different people and groups of people have diverse views and points of view about what it entails. Several studies have classified VR into three categories: (tele-) presence, interactivity, and immersion. Presence is commonly defined as the sensation of being physically somewhere other than where one is. Interactivity affects the presence and relates to how much users may change their virtual environment in real time. Immersion is the user immersed in another, alternate reality [

15].

Cultural heritage, subjected to environmental risks, material decay, natural disasters, and disturbance from visitors, needs to be comprehensively documented and understood. Simple and “linear” information from manuscript recordings and manual measurements can hardly collect full-scale construction details and performance with high complexity and variability and interpret its invisible interactions with the environment. In addition, the correctness and accuracy of the information are highly dependent on the expertise and responsibility of practitioners [

16].

The application of virtual reality in historical preservation has gained considerable attention as an effective tool for engaging the public with cultural heritage in new and innovative ways. VR offers immersive experiences that let users explore reconstructed historical environments in ways that traditional methods, such as physical visits or static exhibits, cannot provide [

4]. It enables dynamic interaction with historical spaces, promoting a deeper understanding and appreciation of heritage [

17]. By enabling users to virtually visit historical sites, VR shifts the experience from passive observation to active participation, enhancing educational outcomes and fostering stronger emotional connections to cultural heritage [

16].

Educational institutions and museums have increasingly adopted VR as a means to create. Virtual reality is transforming history education by creating interactive exhibits that breathe life into historical events and make them more accessible to a broader audience [

15]. This trend underscores VR’s potential to deepen learning by offering a more personal connection to historical events and environments. Additionally, VR’s ability to create realistic, interactive experiences enhances its role in history education, making it a vital tool for historical preservation and public engagement [

17,

18].

However, the accuracy and fidelity of VR reconstructions are crucial to their effectiveness in preservation. High-quality VR models depend on precise data collection and advanced rendering techniques to faithfully reproduce historical spaces. Ensuring that these virtual models accurately reflect historical environments is key to preserving the integrity of the historical narrative [

16]. Experts emphasise the importance of collaborating with historians and cultural heritage professionals to ensure that VR reconstructions are based on authentic historical data [

16].

Despite its great potential, integrating VR into historical preservation presents several challenges [

18]. Creating high-quality VR content is expensive and requires specialised skills in 3D modelling, digital rendering, and software development [

19]. In addition, accessing accurate and comprehensive historical data can be a barrier to building detailed virtual environments. Nonetheless, VR offers significant opportunities to make historical sites more accessible and interpretable, enabling the preservation and presentation of cultural heritage in unprecedented ways [

17]. VR’s ability to transcend geographical and temporal boundaries allows it to reach a global audience, increasing public engagement and expanding educational opportunities.

The preservation of historical architectural spaces is a critical challenge, as many heritage sites face threats from environmental degradation, urbanisation, and lack of proper documentation. Conventional methods of preservation rely heavily on physical restoration and static documentation, which limit the accessibility and engagement of the public. VR has emerged as a promising tool for historical preservation, offering immersive, interactive experiences that allow users to explore and understand cultural heritage sites in ways that traditional methods cannot achieve. However, the application of VR in historical architecture remains underexplored, particularly regarding its accuracy, usability, and effectiveness in educational contexts.

Recent studies have demonstrated that VR can significantly enhance learning by increasing user interaction and retention of historical knowledge. Moreover, VR provides cost-effective alternatives to physical site visits, enabling broader public engagement with heritage sites [

19]. However, issues such as hardware limitations, lack of high-resolution historical data, and the need for expert collaboration remain barriers to effective implementation [

20]. Addressing these concerns requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates expertise from architecture, digital humanities, and conservation science.

The integration of emerging technologies into heritage conservation represents a pivotal shift towards more informed, precise, and sustainable preservation practices. This section explores the convergence of imaging technologies within the context of safeguarding cultural heritage (

Table 1). This section explores how these technologies, through a synergistic application, offer the potential to revolutionise the field by enhancing documentation accuracy, enabling real-time monitoring, facilitating predictive maintenance, and ensuring the participatory involvement of stakeholders [

21].

3. Materials and Methods

This research employed a quantitative approach to examine the use of virtual reality in historical preservation, specifically focusing on the accuracy, challenges, and potential of VR applications in preserving historical architecture [

21]. A survey was conducted with 57 participants, including experts from fields like architectural history, heritage conservation, virtual reality, interior design, and architecture. The participants were chosen through convenience sampling to ensure representation from professionals in both the built environment and digital humanities.

The survey included multiple-choice questions, Likert-scale ratings, and open-ended questions to collect both quantitative and qualitative data on key topics. It was structured around three main themes: the accuracy of VR reconstructions (with an emphasis on spatial relationships and historical accuracy), the challenge of integrating VR technology (such as technical difficulties, data constraints, and balancing authenticity with user engagement), and the opportunities VR offers for enhancing education and making historical experiences more accessible [

22].

To ensure consistency in measuring participants’ views, all responses were rated using a 5-point Likert scale. Open-ended questions were also included to gather additional insights on best practices and the future potential of VR in historical preservation. In analysing the data, dispersion measures such as mean, variance, standard deviation, range, and interquartile range (IQR) were applied to better understand the variation in responses. This approach provided a clearer view of participant consensus and the diversity of perspectives, offering valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities of VR in this field [

23]. The results of this study offer important implications for future VR applications in historical preservation, enhancing educational engagement, and making cultural heritage more accessible to a wider audience.

4. Results

The findings reveal both the advantages and challenges of using VR in the conservation and presentation of cultural heritage. The discussion incorporates insights from various research studies focusing on the accuracy of VR models, their impact on education, and their broader implications for heritage management. It also considers technical limitations and explores VR’s potential to broaden access to cultural heritage, offering new ways for people to interact with and learn about the past. The study involved 57 participants from various fields of expertise. The largest group of participants worked in the field of architectural history, making up 32% (18 people), followed by heritage conservation (21%, 12 people), virtual reality (18%, 10 people), architecture (16%, 9 people, interior design (9%, 5 people), and other fields (5%, 3 people). Most participants (74%, 42 people) had experience working on projects that used virtual reality (VR) for historical buildings, while 26% (15 people) had never worked on such projects (

Table 2).

For people with experience working on VR projects, the main areas they focused on were improving educational experiences (63%, 36 people), helping with conservation and restoration efforts (53%, 30 people), and supporting research and documentation (61%, 35 people). The number of years they had worked in their fields varied: 7% (4 people) had less than a year of experience, 21% (12 people) had less than a year of experience, 21% (12 people) had 1–3 years, 32% (18 people) had 4–6 years, 21% (12 people) had 7–10 years, and 19% (11 people) had more than 10 years.

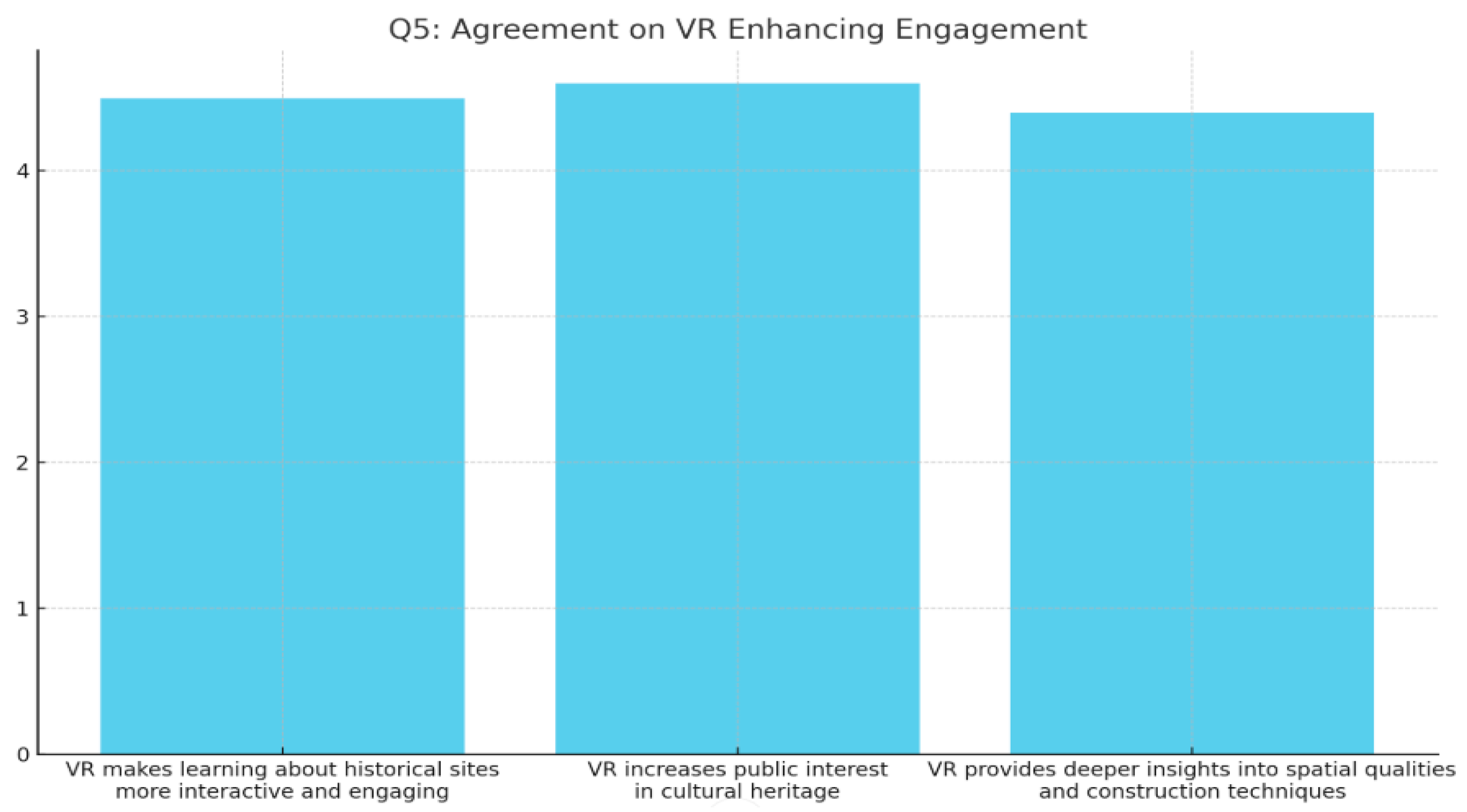

4.1. Enhancing Engagement and Educational Value

The survey results revealed a strong consensus on the positive impact that VR can have in enhancing engagement with historical architecture spaces. Participants overwhelmingly agreed that VR plays a crucial role in making the learning experience more interactive and engaging. The statement that VR makes learning about historical sites more interactive and engaging received an impressive average score of 4.6, indicating widespread agreement among respondents. Even more compelling was the response to the statement that VR increases public interest in cultural heritage, which earned the highest average score of 4.7, demonstrating the technology’s effectiveness in sparking public curiosity and enthusiasm for preserving cultural landmarks (

Figure 2). These findings align with previous studies that emphasise the role of immersive technologies in improving learning outcomes. For instance, Ref. [

23] highlighted that VR fosters active learning by engaging users through realistic simulations and interactive storytelling. Similarly, Ref. [

24] found that VR applications in heritage education increased students’ retention rates compared to traditional learning methods. This suggests that VR is not only an engaging tool but also a powerful medium for exploring the intricate details of historical architecture, offering a more immersive and comprehensive understanding than traditional methods.

The analysis of strategies to enhance the educational value of virtual reality for historical architecture revealed varying levels of perceived effectiveness among participants. “Virtual walkthroughs with guided narration” emerged as the most favoured strategy, achieving the highest average score of 4.5, underscoring its value in making VR experiences more educational. Similarly, “Enabling real-time interaction with VR environments” received a strong average score of 4.4, highlighting the importance of interactivity in improving user engagement and learning outcomes. The inclusion of “Supplementary historical and cultural materials” was rated favourably, with a score of 4.3, reflecting its role in providing valuable context. Meanwhile, “Incorporating gamification elements” scored slightly lower at 4.0, indicating it is still viewed as effective, though less critical compared to other strategies (

Figure 3). The effectiveness of guided narration is supported by research in digital heritage, where [

25] found that narrative-driven experiences improve information retention and comprehension in virtual heritage sites. The preference for real-time interactivity aligns with studies by [

26], who emphasised that interactive VR fosters deeper cognitive engagement by allowing users to explore spaces at their own pace. Meanwhile, incorporating gamification elements scored slightly lower at 4.0, indicating that it is still viewed as effective, though less critical compared to other strategies. These findings emphasise the need for guided, interactive, and context-rich VR experiences to maximise their educational potential in historical architecture.

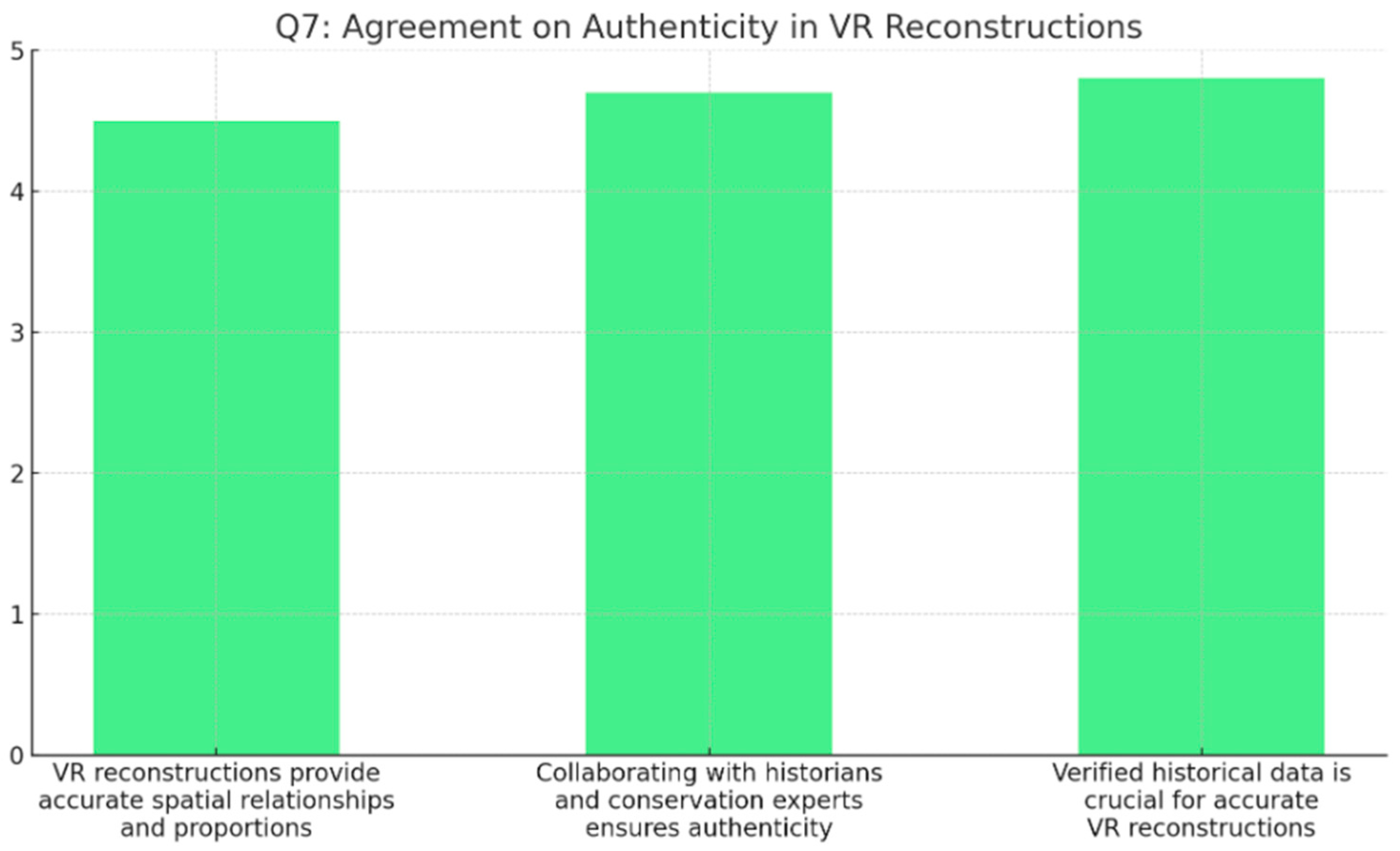

4.2. Ensuring Authenticity and Accuracy

The analysis of authenticity and accuracy in VR reconstructions of historical architecture highlights strong agreement among participants on the critical importance of maintaining historical fidelity. “Verified historical data is crucial for accurate VR reconstructions” received the highest average score of 4.8, demonstrating the consensus that accurate and reliable historical sources are foundational to the success of VR projects. Similarly, “Collaborating with historians and conservation experts ensures authenticity” scored an impressive 4.7, underlining the necessity of interdisciplinary collaboration to uphold authenticity in reconstructions. Lastly, “VR reconstructions provide accurate spatial relationships and proportions” achieved a solid score of 4.5, reflecting confidence in VR technology’s ability to faithfully represent spatial dimensions (

Figure 4). These findings are consistent with the literature on digital heritage preservation. According to [

27], ensuring accuracy in digital reconstructions requires rigorous research, including archival documents, photogrammetry, and expert validation. Furthermore, VR’s ability to represent accurate spatial relationships and proportions (mean score: 4.5) reinforces its potential as a reliable tool for historical documentation, as also argued in ref. [

28]. This indicates that historical accuracy, expert involvement, and technological precision are pivotal in creating credible and impactful VR reconstructions of historical architectural spaces.

The evaluation of practices for ensuring accuracy in VR reconstructions underscores the importance of a methodical and collaborative approach. “Consulting historical records and archival documents” emerged as the most critical practice, receiving the highest average score of 4.8, reflecting a strong consensus on the necessity of comprehensive historical research for precise VR models. “Involving multidisciplinary teams in project development” followed closely with a score of 4.7, highlighting the value of collaboration among experts from diverse fields to ensure authenticity and depth in VR reconstructions. Similarly, “Using high-resolution and detailed imagery” scored 4.6, emphasising the role of advanced visual quality in achieving realistic and accurate virtual representations. Lastly, “Conducting iterative peer reviews of VR models” scored 4.5, affirming that expert evaluations are a vital step in refining and validating the accuracy of VR outputs (

Figure 5). The importance of historical research in VR has been documented by ICOMOS [

28], which emphasises archival accuracy as a key factor in virtual reconstructions. Moreover, using high-resolution and detailed imagery (score: 4.6) supports findings from Manferdini and Remondino [

29], who stress the role of advanced imaging techniques such as Lidar scanning in achieving photorealistic representations. Lastly, conducting iterative peer reviews of VR models (score: 4.5) is crucial, as demonstrated by [

30], who argue that expert validation reduces the risk of inaccuracies in digital heritage applications.

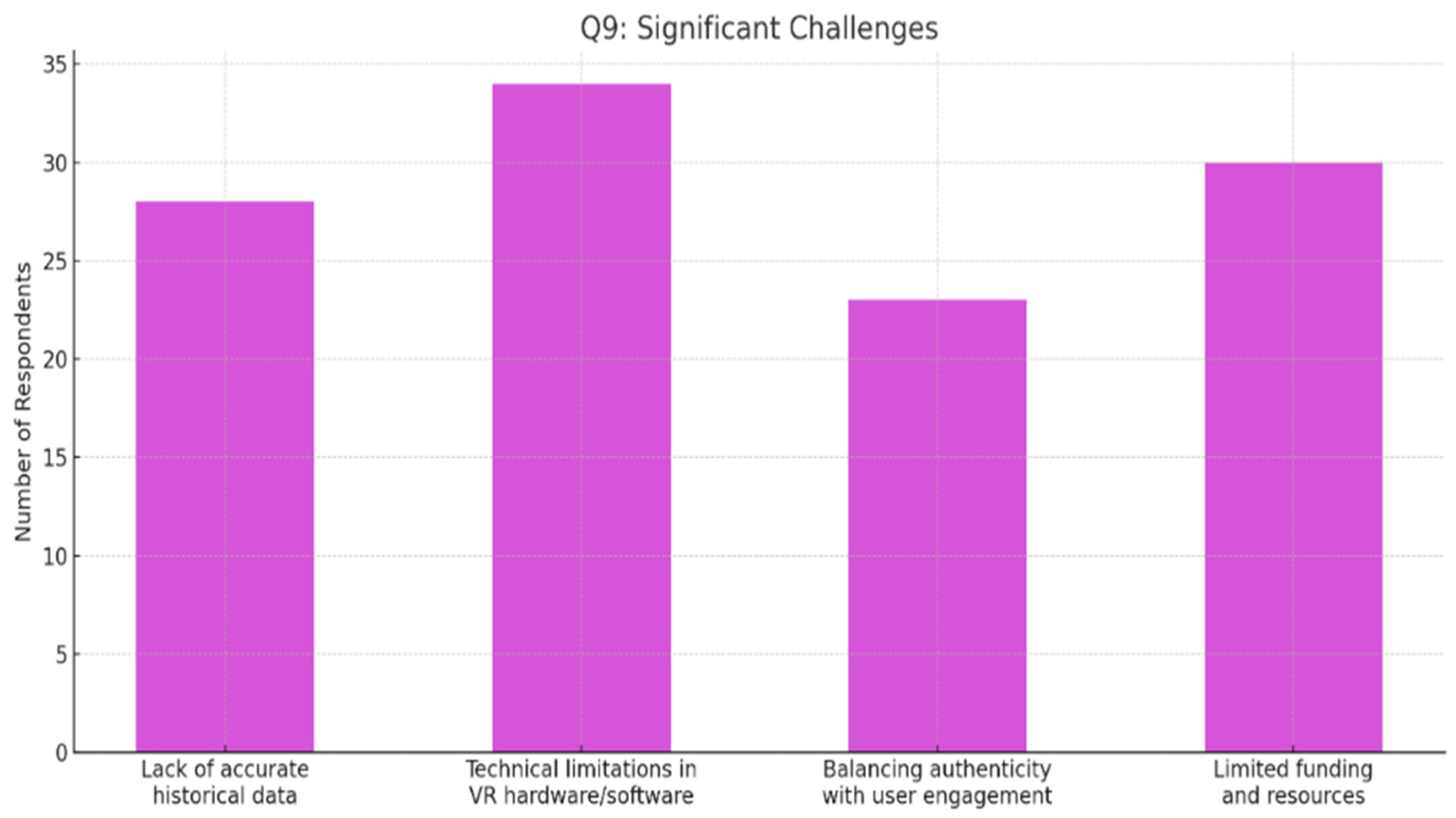

4.3. Challenges and Considerations

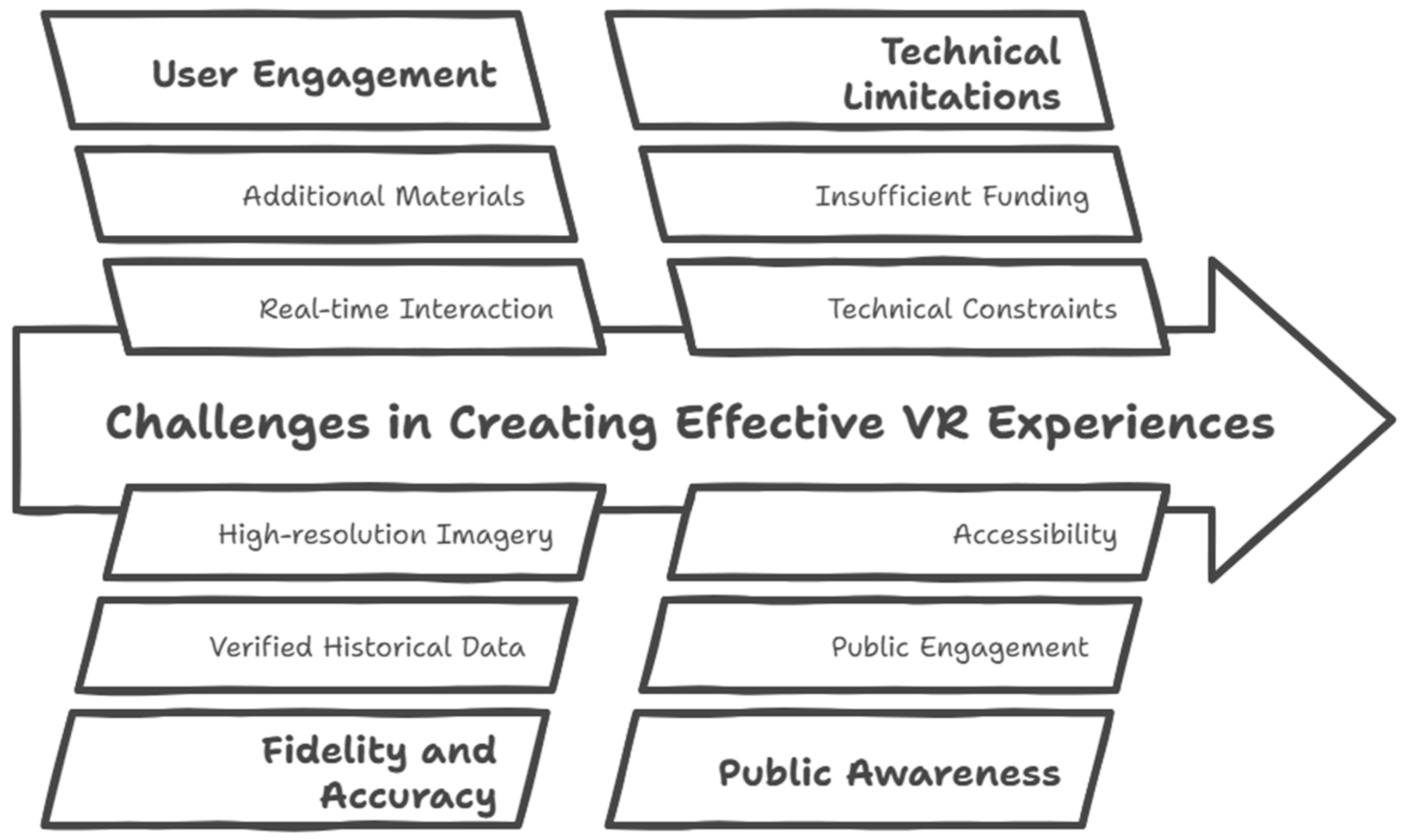

Respondents identified several critical challenges in implementing VR for historical architecture. The most prominent challenge was technical limitations in VR hardware/software, cited by 60% of respondents (34 individuals), underscoring the constraints posed by the current state of the technology. Similar concerns were raised in a study by [

30], which highlighted the need for improved rendering capabilities and real-time processing to enhance VR realism. Additionally, a lack of accurate historical data was noted by 50% (28 respondents), reinforcing the challenges of sourcing verifiable documentation, as pointed out by Styliani et al. [

31]. Limited funding and resources (53%, 30 respondents) are another major issue, reflecting broader financial barriers in digital heritage initiatives [

32]. Finally, balancing authenticity with user engagement (40%, 23 respondents) remains an ongoing debate (

Figure 6), as the authors of [

33] arguing that interactivity can sometimes compromise historical integrity.

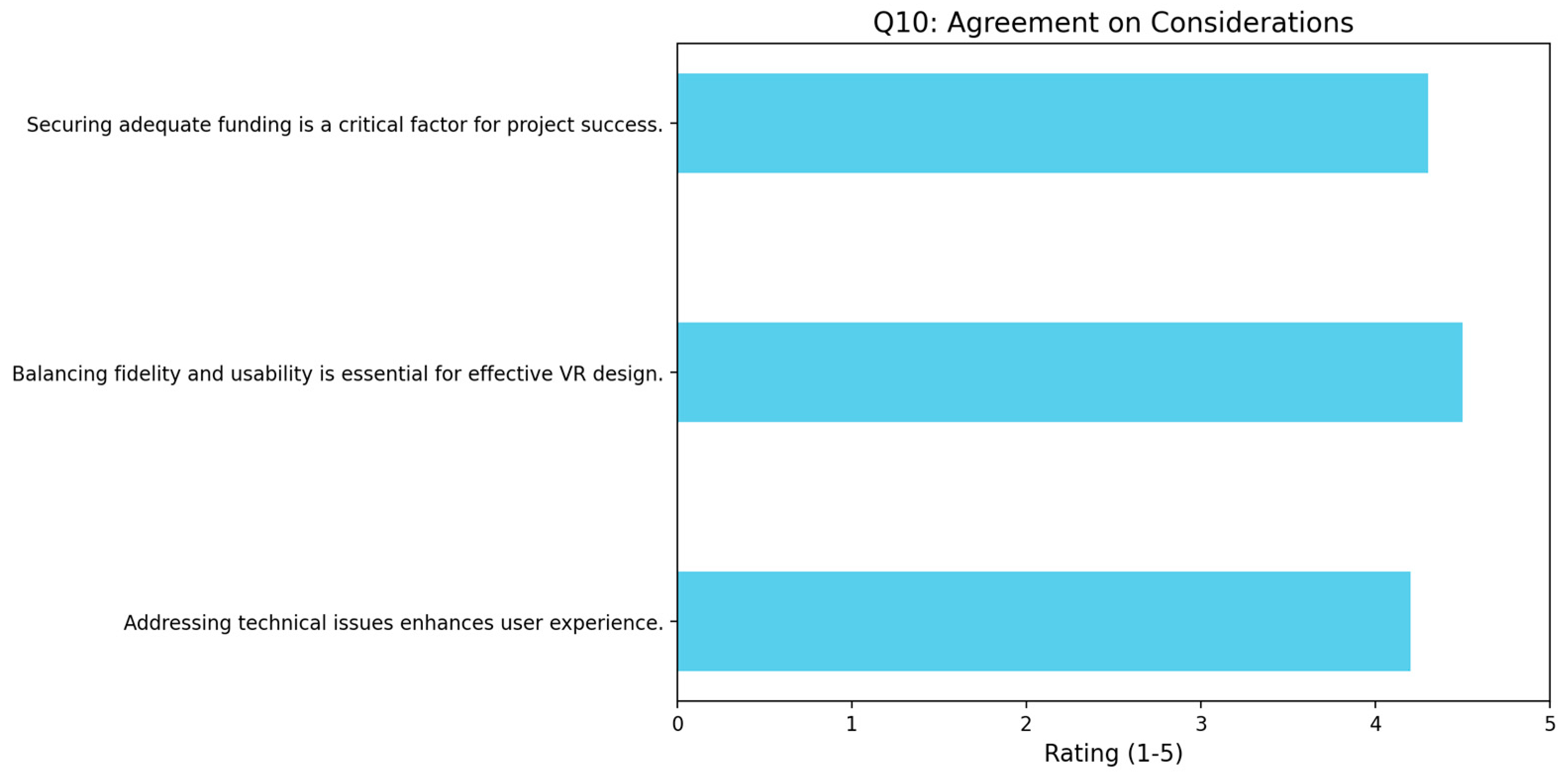

Participants highlighted key considerations for improving VR applications in historical architecture, emphasising the significance of addressing financial, design, and technical aspects. The highest-rated factor, “Securing adequate funding is a critical factor for project success”, received an agreement score of 4.6, underscoring the necessity of robust financial support for the development and long-term viability of VR initiatives. “Balancing fidelity and usability is essential for effective VR design”, followed closely with a score of 4.5, indicating the importance of creating VR experiences that maintain historical accuracy while being accessible and user-friendly. Finally, “Addressing technical issues enhances user experience” was rated at 4.4, highlighting the need to overcome technological challenges to deliver immersive and engaging environments (

Figure 7). Collectively, these insights reflect the multi-dimensional challenges of integrating VR into historical preservation and the pivotal role of strategic planning, resource allocation, and technological innovation in ensuring project success [

31].

4.4. Dispersion Measure

The dispersion measures reveal strong consensus across most factors related to virtual reality applications in historical architecture. For aspects like VR enhancing engagement, various strategies for enhancing educational value, authenticity in VR reconstructions, and practices for accuracy, the low variance and standard deviations suggest that participants shared similar views. In particular, authenticity in VR reconstructions and practices for accuracy showed very high consistency, with extremely low variability in responses. The narrow range and interquartile ranges for these factors further emphasise this agreement, indicating that most respondents were aligned in their perceptions. Considerations on improving VR also reflected strong agreement, with low dispersion in the responses. However, the challenges of implementing VR in historical architecture displayed much greater variability. With a mean score of 4.52, and substantial variance and standard deviation, this factor shows that there were significant differences in how respondents viewed the challenges of implementing VR. The wide range and interquartile range further indicate diverse opinions on this issue, highlighting the complexity and varied perspectives regarding the difficulties in applying VR technology to historical architecture. Overall, while there is strong alignment on the benefits and strategies of VR, the challenges associated with its implementation seem to be more contentious and diverse in opinion (

Table 3).

6. Conclusions

The findings from this study highlight the significant potential of Virtual Reality (VR) for enhancing public engagement and educational experiences related to historical sites. VR not only facilitates a more immersive and interactive learning experience but also offers a way to accurately reconstruct and explore historical contexts through digital environments. The study shows that VR’s integration with verified historical data, high-resolution imagery, and collaboration with historians and conservation experts are crucial for creating accurate and engaging virtual experiences. Despite some challenges related to technical limitations, funding, and balancing authenticity with user engagement, the results demonstrate that VR is a valuable tool for promoting cultural heritage appreciation. Results of this study could be a foundation to initiate robust educational resources studying of the applicability of emerging technologies like VR, AR, and MR for conservation of culture and the built environment to enhance learners’ experience. The acceptance of VR technology, with interactive elements including real-time interactions and supplementary materials, propels that VR can be powerfully utilized to increase the interest of the public to cultural heritage. The effectiveness of the technology can be applied to get informative insights into spatial features and construction technique to support the teaching and learning process. The study highlights that VR is a powerful historical preservation tool, improving educational outcomes and public engagement. However, accuracy, usability, and funding constraints must be addressed to maximize its potential. By addressing the following recommendations, stakeholders and practitioners can maximize the impact of VR applications for promoting cultural heritage preservation and public engagement:

Enhancing Data Accuracy—Future projects should prioritise archival research, photogrammetry, and expert validation in VR reconstructions.

Securing Funding—Governments, cultural institutions, and private investors should establish dedicated VR heritage funding programmes.

Improving Accessibility—Developers should explore cloud-based VR solutions and mobile-compatible applications to expand access.

Encouraging Public Engagement—Gamification, interactive storytelling, and multisensory VR environments can increase user interest and retention.

Future Research Directions

Comparative analysis of VR applications in different cultural contexts.

Exploration of AI and machine learning in enhancing VR heritage reconstructions.

Development of cost-effective VR tools for underfunded heritage sites.