Deconstructing Seokguram Grotto: Revisiting the Schematic Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Known Facts

1.2. Literature Review & Research Objectives

2. Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Design Constraints

2.2. Historical Mathematics and Comparative Models

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

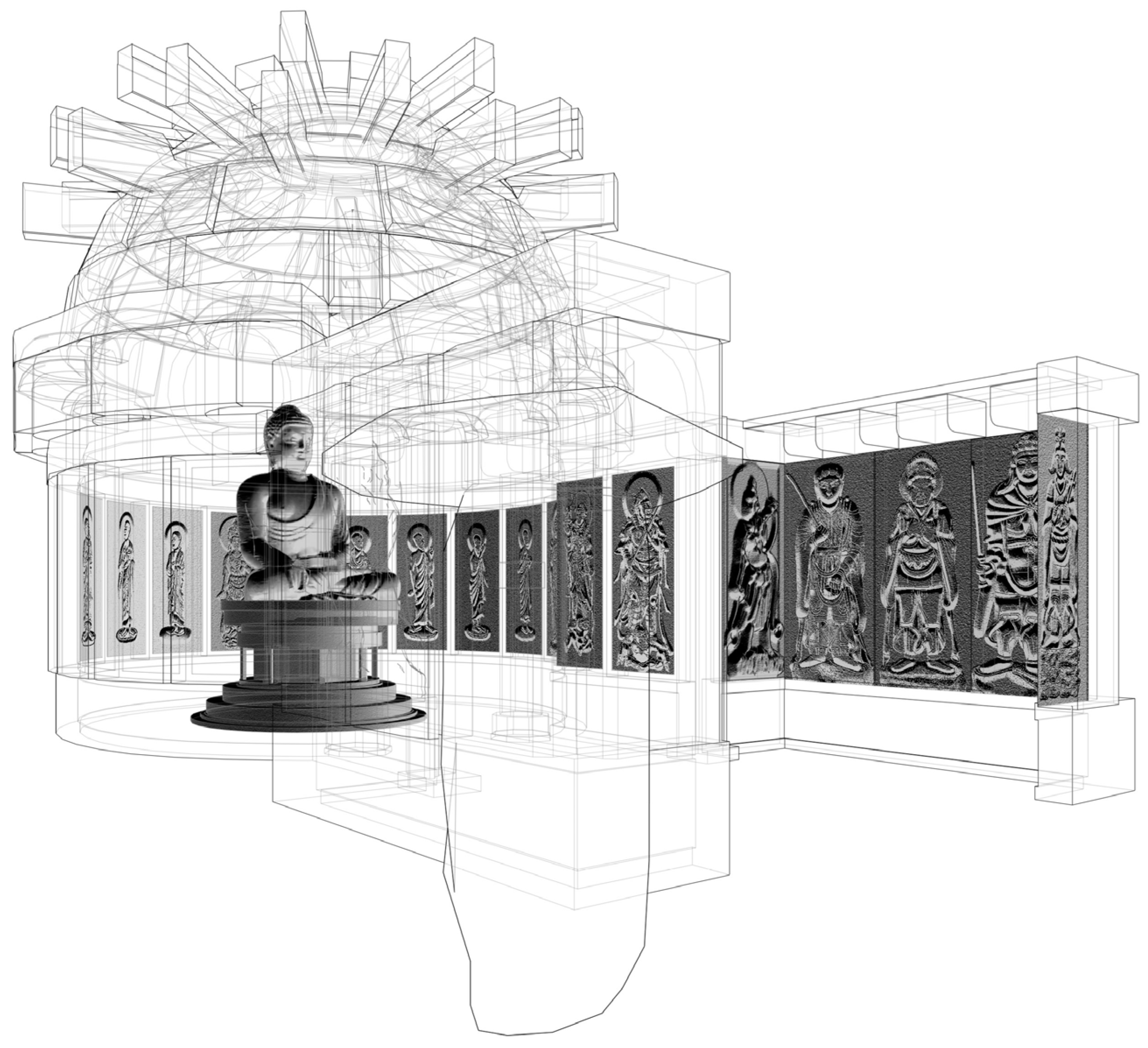

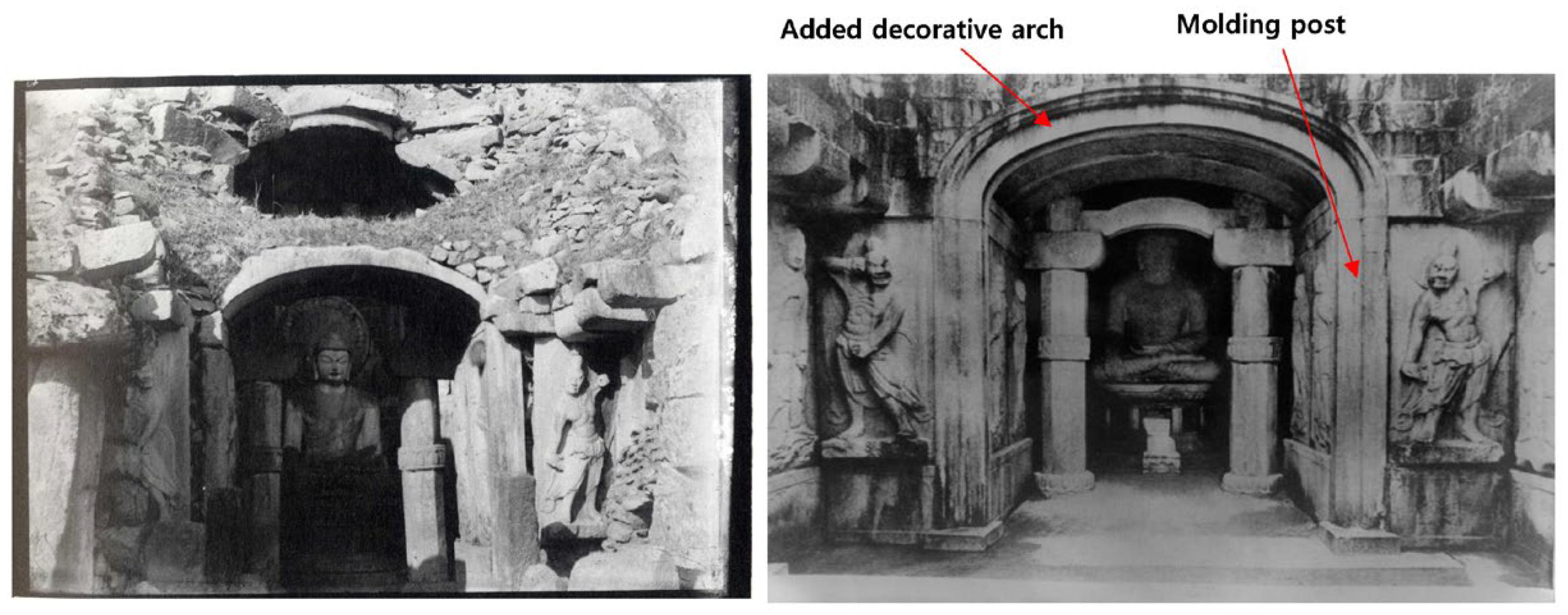

3.1. Overview of Repair Work and Spatial Changes

3.2. Analysis of External Design Constraints

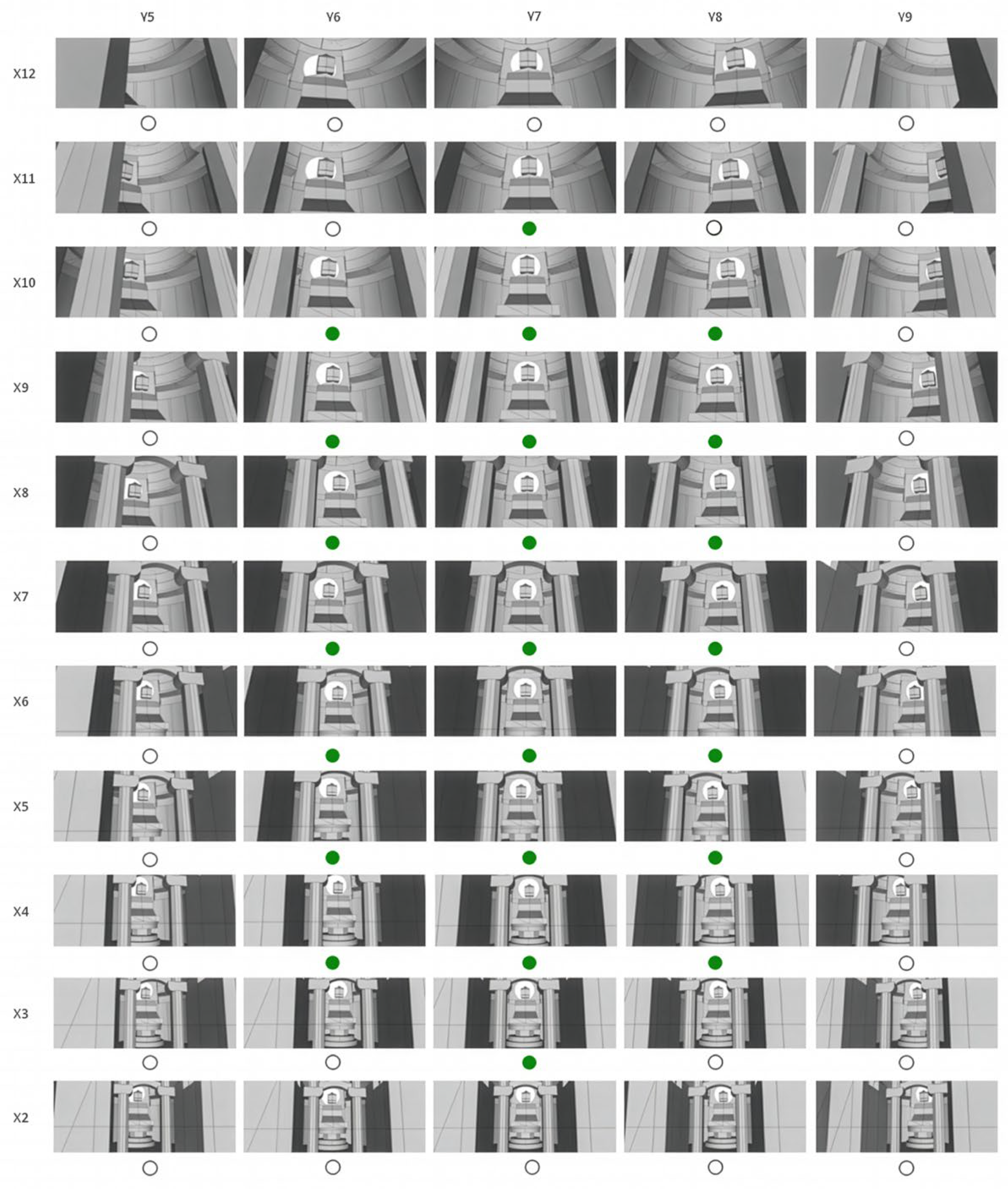

3.3. Analysis of Internal Design Constraints

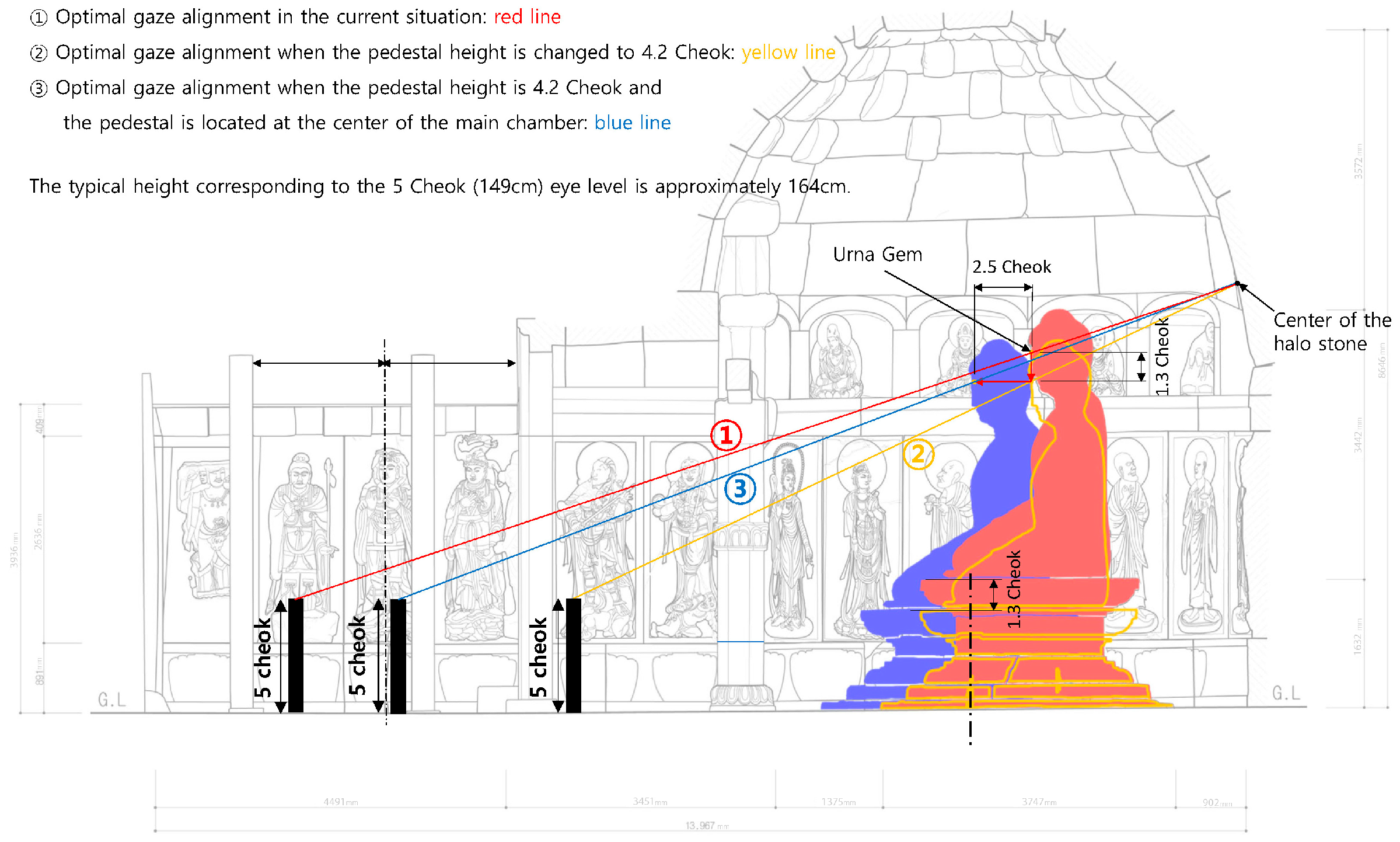

3.4. The Interplay of Internal and External Design Constraints

3.5. Analysis of Dimensional System

3.5.1. Plan Dimensions with Binary Division System

3.5.2. Section Dimensions with Binary Division System

4. Discussions

4.1. Primary Modules and Spatial Proportions

4.2. Scene Perception and Proportional System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gombrich, E.H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation—Millennium Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg, J.E. Visual Perception in Architecture. VIA 1983, 6, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda, M. A Research on Ancient Korean Architecture; Akitaya: Tokyo, Japan, 1944. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, M. The Aesthetic Beauty of the Forms in Traditional Korean Architecture; Kimoondang: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1987. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W. A Study on Iconography of Main Buddha in Sukpulsa Temple. Misuljaryo 1984, 35, 54–57. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Nam, C. Seokbulsa: Multistoried Stone Pavilion of Toham Mountain; Iljogak: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1991. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y. Seokguram: Heaven Descended and Settled upon the Earth; The Chosun Ilbo: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2003. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Salguero-Andújar, F.; Prat-Hurtado, F.; Rodriguez-Cunill, I.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Architectural Significance of the Seokguram Buddhist Grotto in Gyeongju (Korea). Buildings 2022, 12, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. The Seokguram Grotto in Korea and the Gougu Rule: Rebuttal of the √2 and √3 Hypothesis and a New Interpretation of the Underlying Method. Nexus Netw. J. 2022, 24, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.D. Design as Exploring Constraints. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C. Thrice Repair Works and Three Space Conceptions in Seokguram. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2019, 35, 12. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C. A Critical Review of Modern Repair Works of Seokguram Grotto. In Proceedings of the 6th World Humanities Forum 2, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 4–6 November 2020; pp. 378–387. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art; Liu, H., Li, C., Eds.; Zhonghua Shuju: Beijing, China, 1985. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C. The Stones of Seokguram Speak: Floor Plan and Wall Design of Seokbulsa Grotto. J. Archit. Hist. 2020, 29, 21–37. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Argan, G.C. On the Typology of Architecture. Archit. Des. 1963, 33, 564–565. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C. Plan Schematization: A Computational Approach to Morphological Structure of Architectural Space. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Yoon, C. Seokbulsa Grotto: Architectural Engineering and Buddha Sculptures; Hakcheon: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1998. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Sungkyunkwan University Museum. The Past and Present of Silla Sites in Gyeongju: Seokguram, Bulguksa, and Namsan; Sungkyunkwan University Museum: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Government-General of Korea. Bukoku-ji Temple and Sekkutsu-an Cave in Keishu, Chosen; Government-General of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1938; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wipco. Digital Cultural Heritage Content Creation Project—Seokguram; Cultural Heritage Administration: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Cultural Property Management. The Seokguram Repair Work Report; Bureau of Cultural Property Management: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1967. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama, S. Great Tang Records on the Western Regions; Shokado: Kyoto, Japan, 1999. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G. The History of Ancient Chinese Measures and Weights, 1st ed.; Anhui kexue jishu chubanshe: Hefei, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. One Prime Object, Different Receptions: “The Auspicious Image of Bodhgaya” in Tang China and Buddha Statue at Seokguram in the Unified Silla. Art Hist. Vis. Cult. 2013, 12, 260–305. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Tadgell, C. The History of Architecture in India: From the Dawn of Civilization to the End of the Raj; Architecture, Design, and Technology Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rhi, J. Circular Shrines in India/Central Asia and their Relevance to the Seokguram Sanctuary. Cent. Asian Stud. 2006, 11, 141. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Park, S. Tectonic Traditions in Ancient Chinese Architecture, and Their Development. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2017, 16, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Zhou Bi Suan Jing: Fuyinyi, Annotated ed.; Chao, S., Chen, L., Li, C., Feng, J., Eds.; Zhonghua Shuju: Beijing, China, 1985. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ni, R. On the Origin and Formation of the Northern Dynasties Circular Stone Tombs. J. Peking Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2010, 47, 135–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I. Oriental Astronomical Thoughts, Human History; Yemunseowon: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Puett, M. The Ambivalence of Creation: Debates Concerning Innovation and Artifice in Early China; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Puett, M. To Become a God: Cosmology, Sacrifice, and Self-Divinization in Early China; Harvard University Asia Center: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Iryeon. Samguk Yusa: Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms; Lee, B., Ed.; Dongguk Munhwasa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1956. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C. A Study on the Mythological Analysis and Architectural Space Restoration of the Seokguram Grotto. J. Archit. Hist. 2023, 32, 7–18. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, R. Art of Gyeongju in Korea; Kaizō-sha: Tokyo, Japan, 1940. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Kang, J.; Seon, I. Glass Plates in Seoul National University Museum; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, Repubic of Korea, 2008. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Architectural Institute of Korea. A Study on the Safety Diagnosis of Seokguram Structure; Architectural Institute of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1997. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, M. Elements of Geometry; Xu, G., Ed.; Zhonghua Shuju: Beijing, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. The History of Korean Mathematics; Salim Publishing: Paju, Republic of Korea, 2009. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.-z. Archeoastronomy in China; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Museum of Korea. Gyeongju Seokguram Restoration Completion Drawings; National Museum of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kubovy, M. The Psychology of Perspective and Renaissance Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pirenne, M.H. Optics, Painting & Photography; Cambridge U.P.: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Wittkower, R. Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. The Hidden Dimension; Anchor Books; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. Introducing Architectural Tectonics: Exploring the Intersection of Design and Construction; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. Two Elements of Yojap (Circumambulation around the Buddha Image): The Act of Respectful Bowing and the Creation of Good Karma Between the Buddhists and the Buddha. Art Hist. Vis. Cult. 2011, 10, 142–165. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Dio, C. Roman History; Cary, E., Translator; Volume 5, Available online: https://lexundria.com/dio/53.27/cy (accessed on 12 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoon, C.; Kwon, Y. Deconstructing Seokguram Grotto: Revisiting the Schematic Design. Buildings 2025, 15, 4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244546

Yoon C, Kwon Y. Deconstructing Seokguram Grotto: Revisiting the Schematic Design. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244546

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Chaeshin, and Yongchan Kwon. 2025. "Deconstructing Seokguram Grotto: Revisiting the Schematic Design" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244546

APA StyleYoon, C., & Kwon, Y. (2025). Deconstructing Seokguram Grotto: Revisiting the Schematic Design. Buildings, 15(24), 4546. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244546