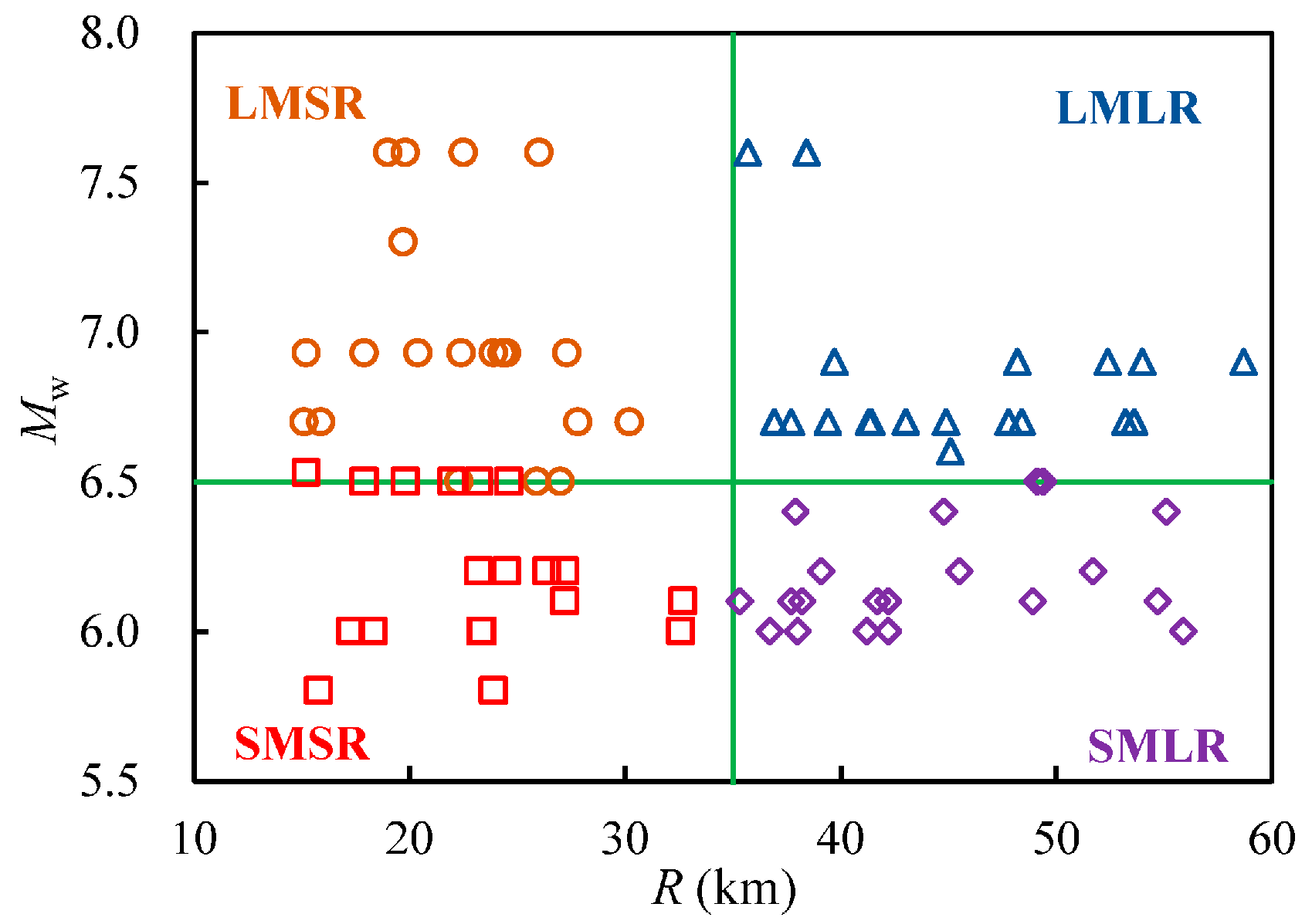

Figure 1.

Relation of Mw-R for the selected motions.

Figure 1.

Relation of Mw-R for the selected motions.

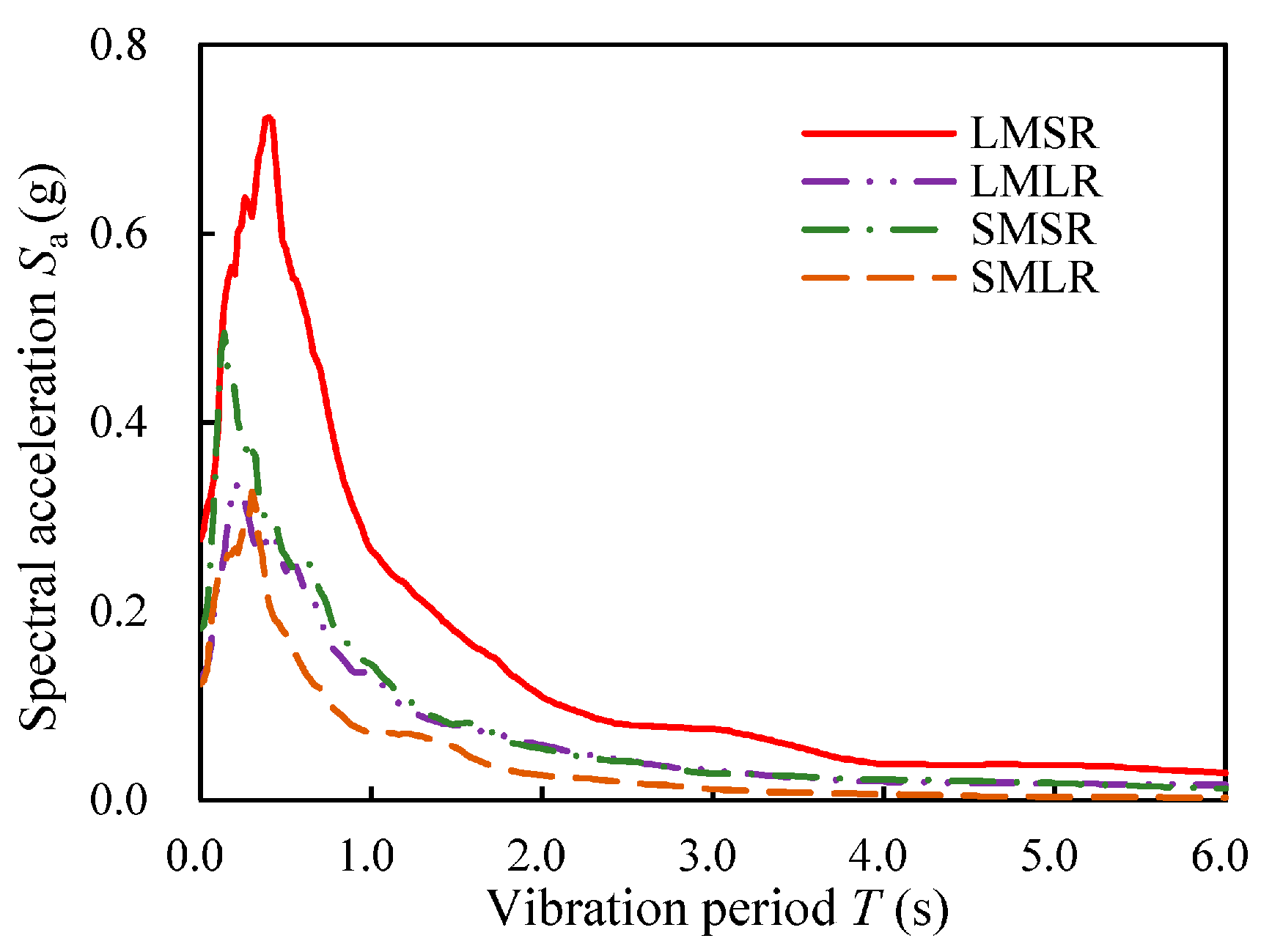

Figure 2.

Median spectral acceleration response of major components for each bin.

Figure 2.

Median spectral acceleration response of major components for each bin.

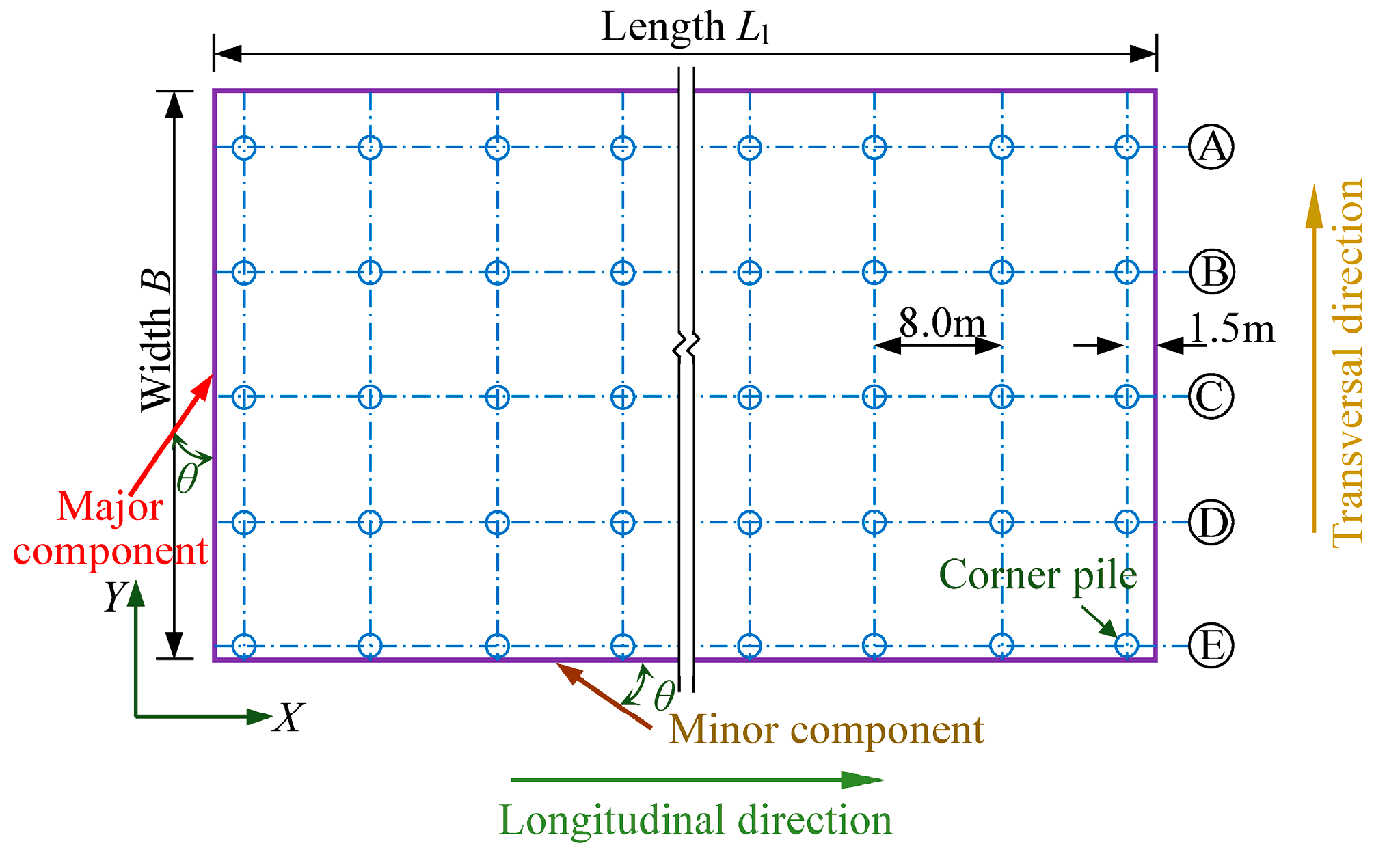

Figure 3.

Illustration of the seismic excitation orientation.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the seismic excitation orientation.

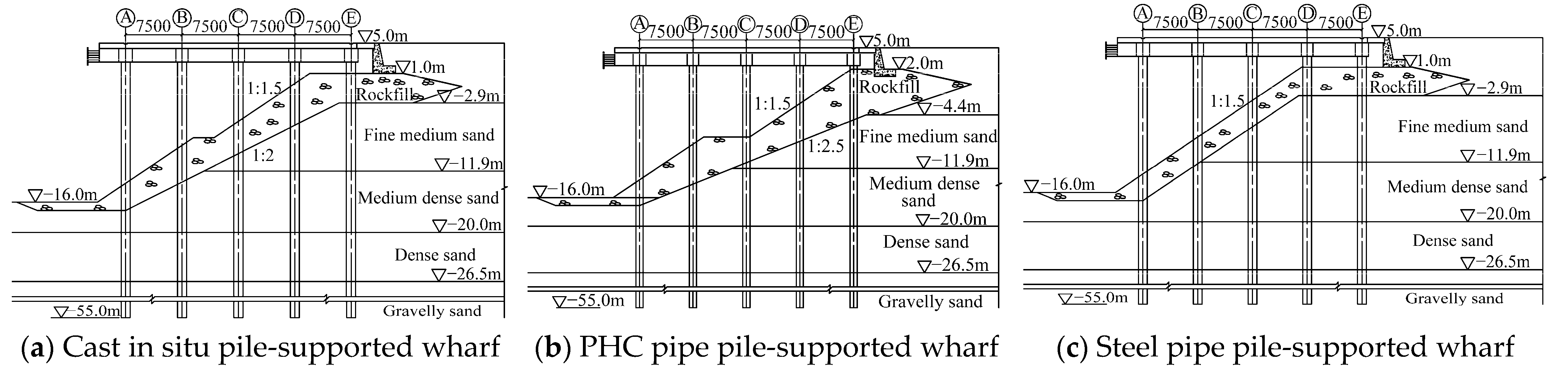

Figure 4.

Transverse section of wharf segments (unit: mm).

Figure 4.

Transverse section of wharf segments (unit: mm).

Figure 5.

Pile-beam connection details (unit: mm).

Figure 5.

Pile-beam connection details (unit: mm).

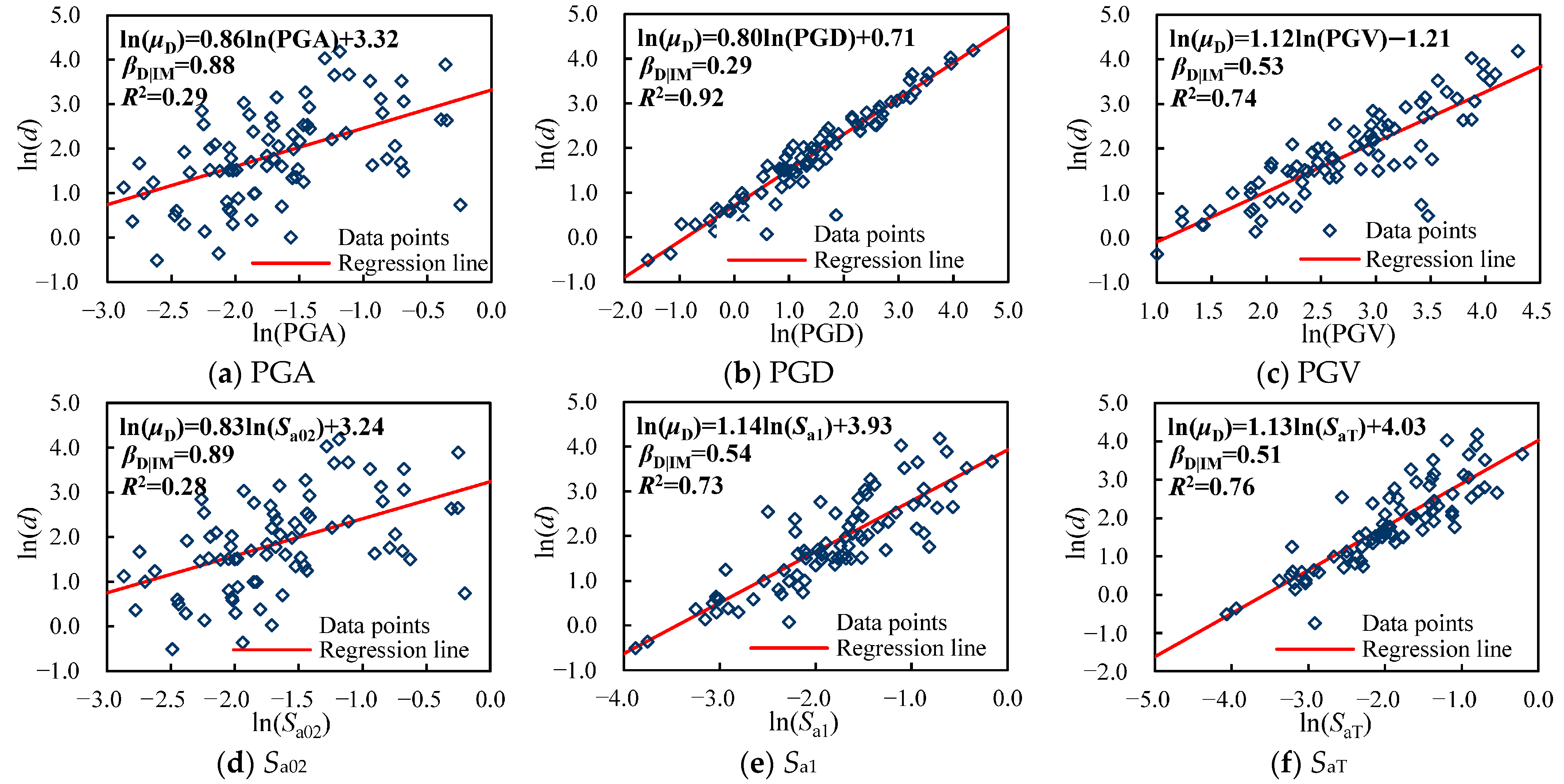

Figure 6.

Probabilistic seismic demand models of a cast in situ pile-supported wharf.

Figure 6.

Probabilistic seismic demand models of a cast in situ pile-supported wharf.

Figure 7.

Sufficiency of intensity measures with respect to Mw.

Figure 7.

Sufficiency of intensity measures with respect to Mw.

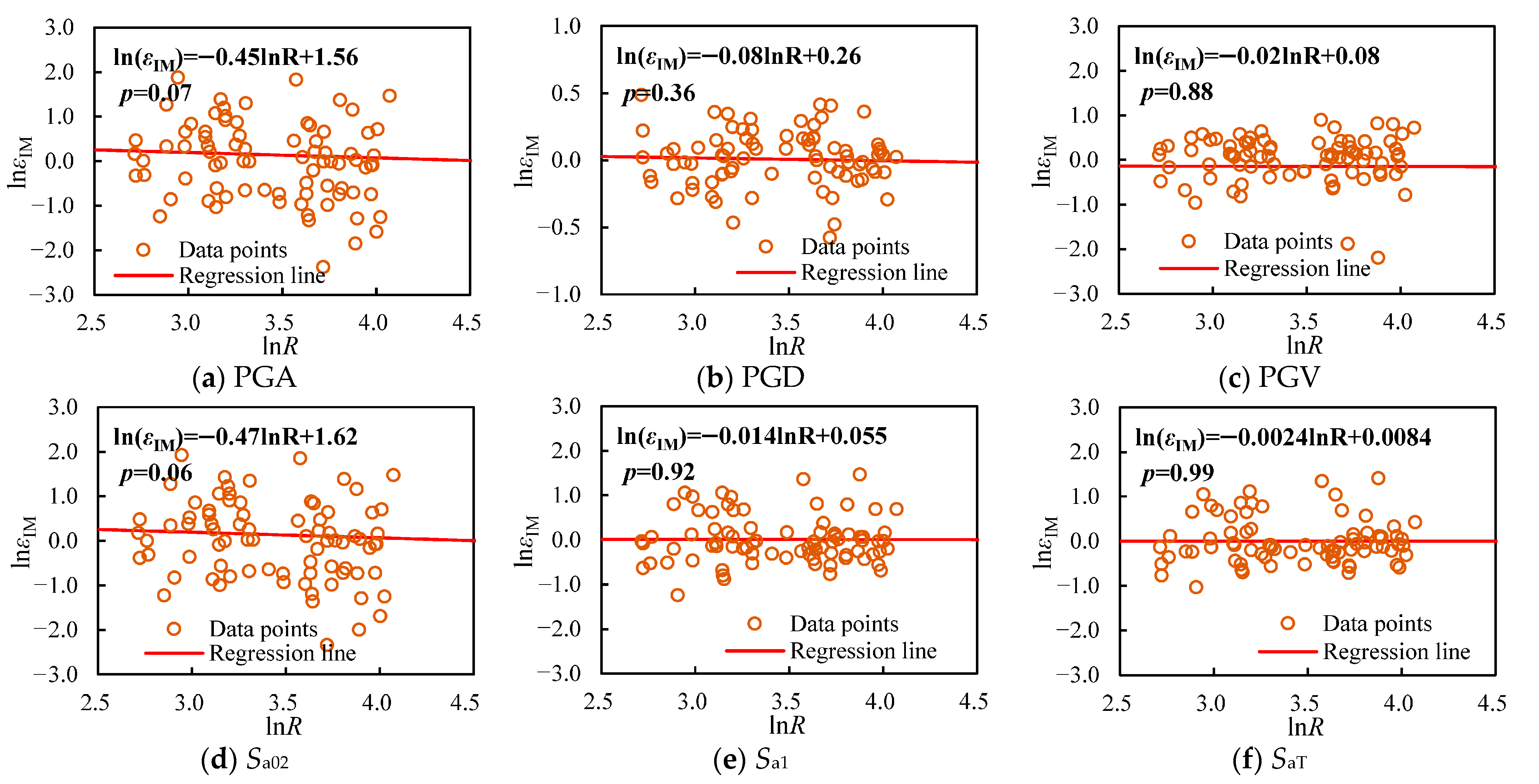

Figure 8.

Sufficiency of intensity measures with respect to R.

Figure 8.

Sufficiency of intensity measures with respect to R.

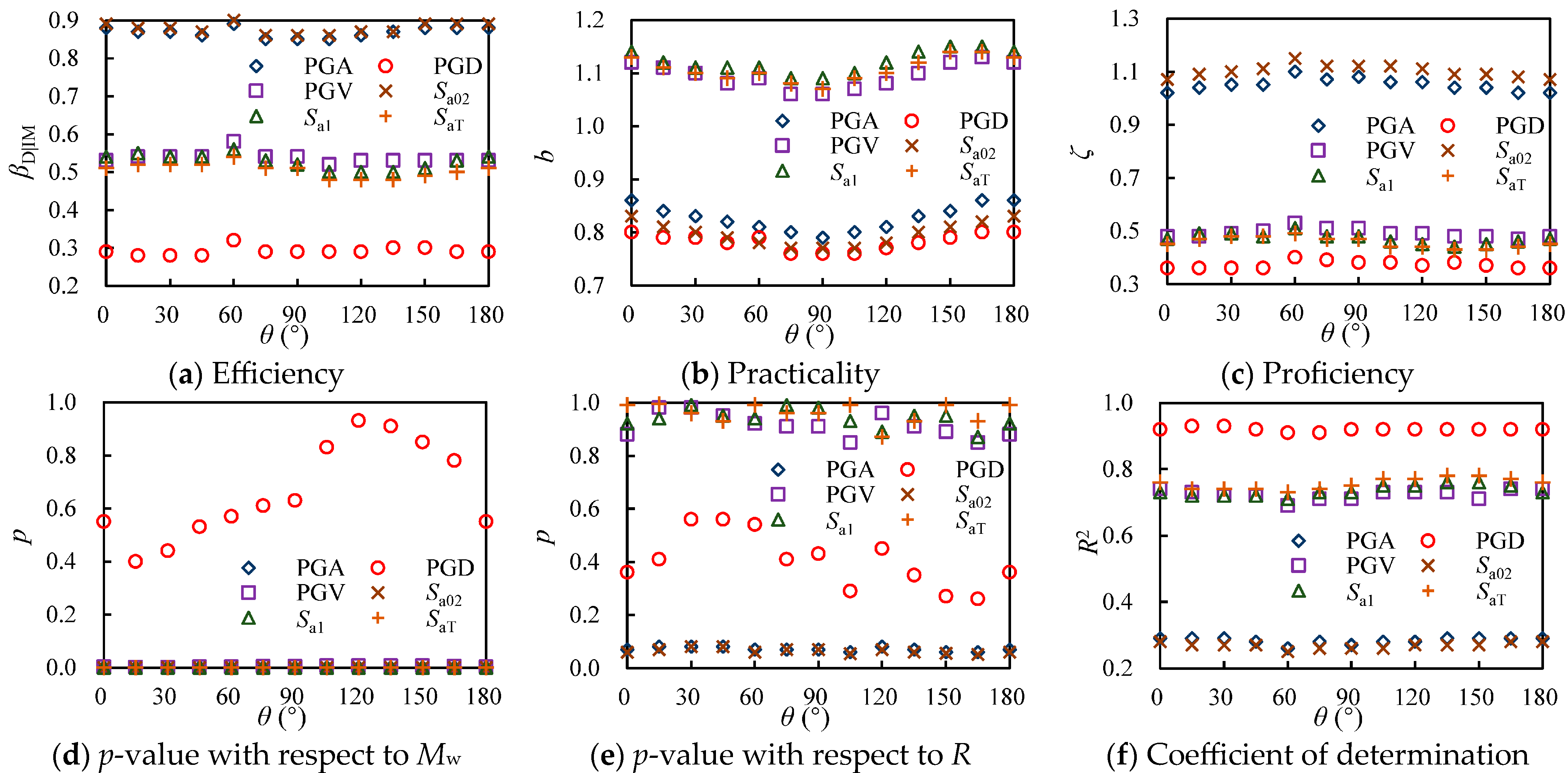

Figure 9.

Comparison of efficiency, practicality, proficiency, and sufficiency results.

Figure 9.

Comparison of efficiency, practicality, proficiency, and sufficiency results.

Figure 10.

Material strain limits of different damage limit states.

Figure 10.

Material strain limits of different damage limit states.

Figure 11.

Pushover curves of wharves.

Figure 11.

Pushover curves of wharves.

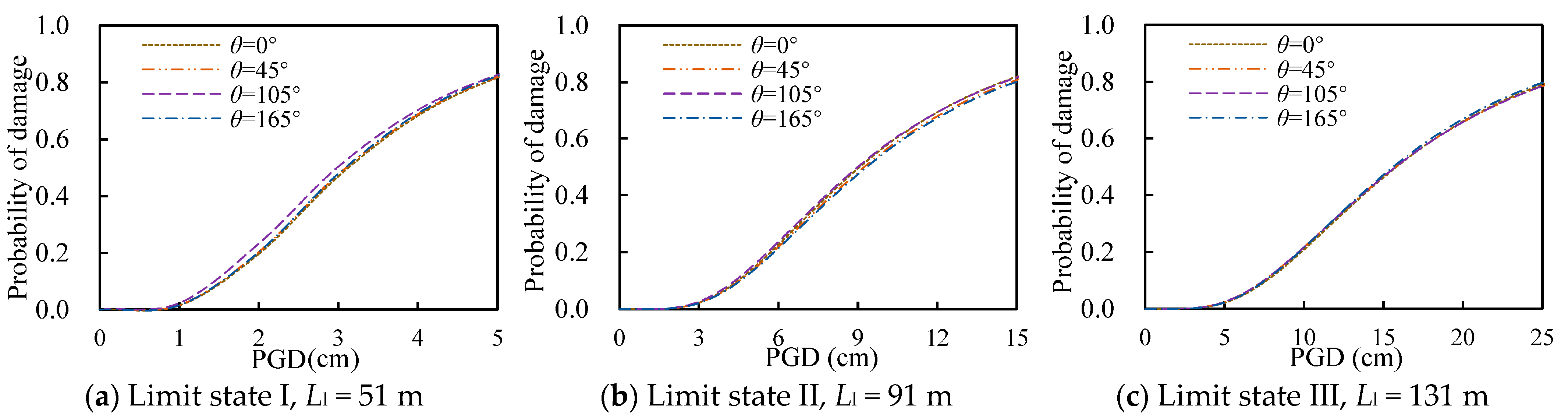

Figure 12.

Fragility curves of CIS pile-supported wharves at different limit states for given angle θ.

Figure 12.

Fragility curves of CIS pile-supported wharves at different limit states for given angle θ.

Figure 13.

Fragility curves of PHC pile-supported wharves at different limit states for given angle θ.

Figure 13.

Fragility curves of PHC pile-supported wharves at different limit states for given angle θ.

Figure 14.

Fragility curves of steel pile-supported wharves at different limit states for given angle θ.

Figure 14.

Fragility curves of steel pile-supported wharves at different limit states for given angle θ.

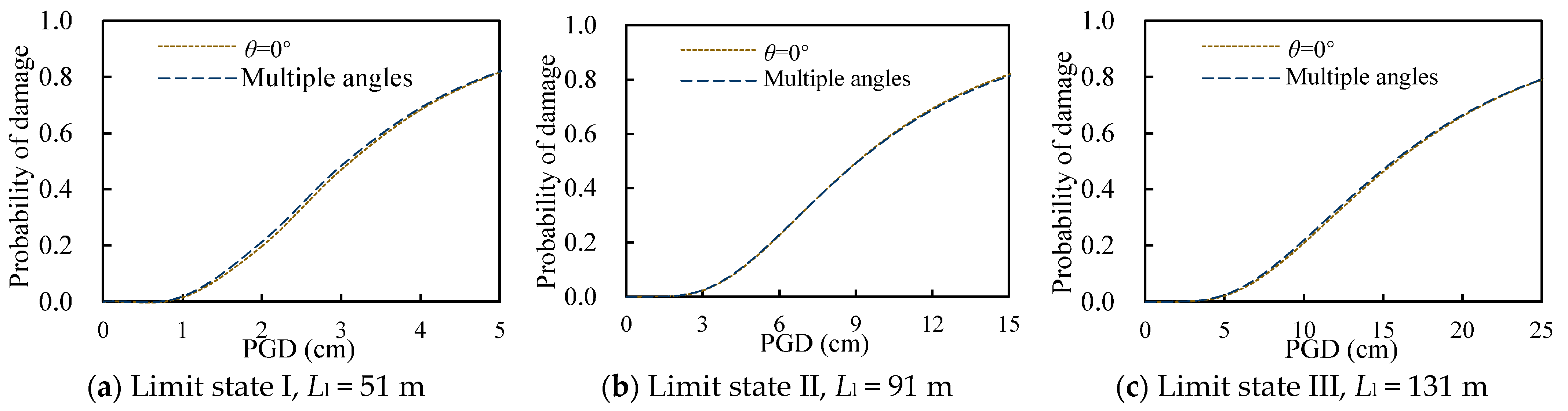

Figure 15.

Fragility curves derived from a single angle (θ = 0°) and multiple angles for CIS pile-supported wharves.

Figure 15.

Fragility curves derived from a single angle (θ = 0°) and multiple angles for CIS pile-supported wharves.

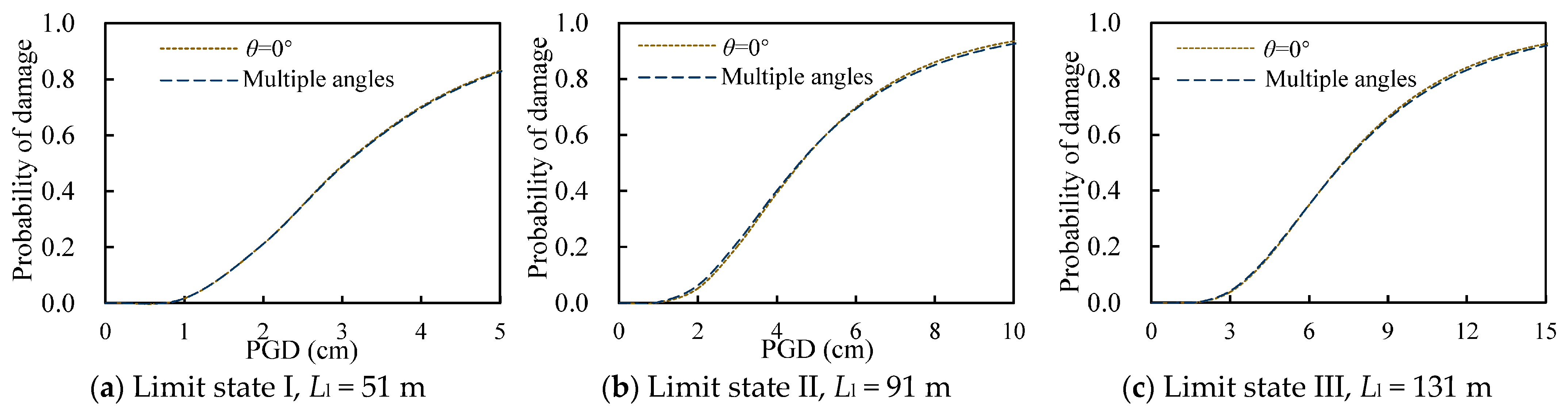

Figure 16.

Fragility curves derived from a single angle (θ = 0°) and multiple angles for PHC pile-supported wharves.

Figure 16.

Fragility curves derived from a single angle (θ = 0°) and multiple angles for PHC pile-supported wharves.

Figure 17.

Fragility curves derived from a single angle (θ = 0°) and multiple angles for steel pile-supported wharves.

Figure 17.

Fragility curves derived from a single angle (θ = 0°) and multiple angles for steel pile-supported wharves.

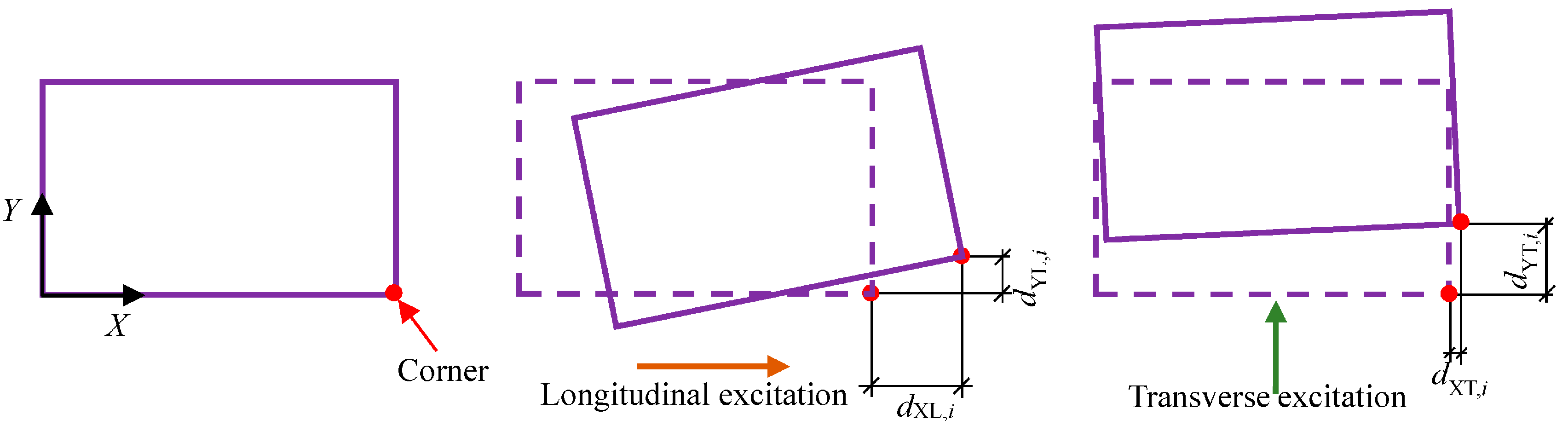

Figure 18.

Wharf deformation due to longitudinal and transverse excitations.

Figure 18.

Wharf deformation due to longitudinal and transverse excitations.

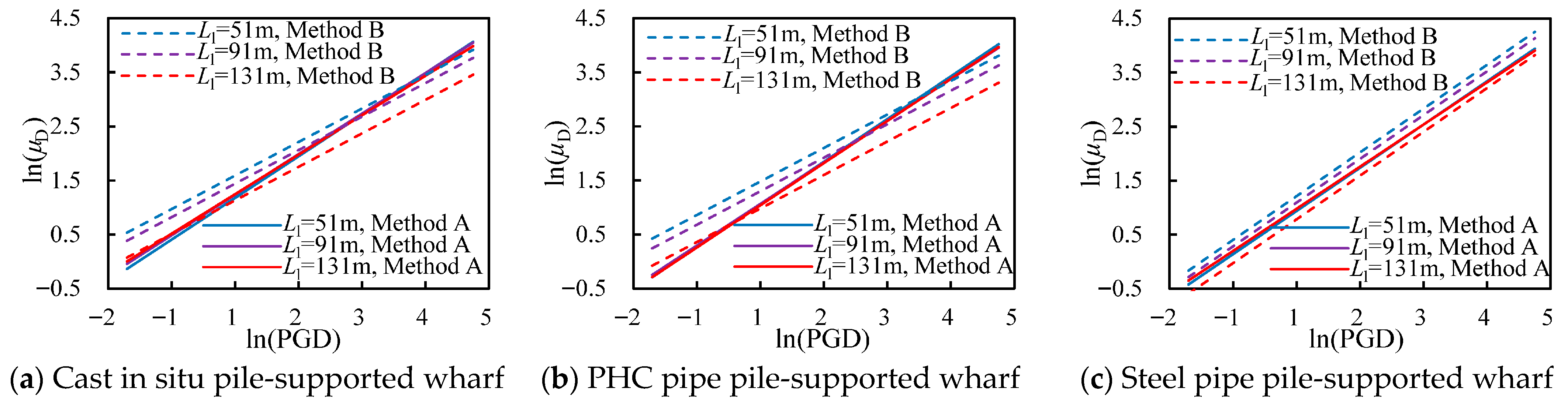

Figure 19.

Comparison of PSDMs generated from Methods A and B.

Figure 19.

Comparison of PSDMs generated from Methods A and B.

Figure 20.

Fragility curves derived from Methods A and B for CIS pile-supported wharves.

Figure 20.

Fragility curves derived from Methods A and B for CIS pile-supported wharves.

Figure 21.

Fragility curves derived from Methods A and B for PHC pile-supported wharves.

Figure 21.

Fragility curves derived from Methods A and B for PHC pile-supported wharves.

Figure 22.

Fragility curves derived from Methods A and B for steel pile-supported wharves.

Figure 22.

Fragility curves derived from Methods A and B for steel pile-supported wharves.

Figure 23.

Wharf planar configurations. (a) Regular wharf; (b) irregular wharf with partial dike; (c) irregular wharf with different adjacent rigidity; and (d) irregular wharf with angle point.

Figure 23.

Wharf planar configurations. (a) Regular wharf; (b) irregular wharf with partial dike; (c) irregular wharf with different adjacent rigidity; and (d) irregular wharf with angle point.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ground motions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ground motions.

| Bin | Mw | R | Number of Motions |

|---|

| I-SMSR (Small magnitude and small distance) | 5.8 < Mw <6.5 | 13 km< R < 30 km | 20 |

| II-LMSR (Large magnitude and small distance) | 6.5 < Mw < 7.0 | 13 km< R < 30 km | 20 |

| III-SMLR (Small magnitude and large distance) | 5.8 < Mw < 6.5 | 30 km< R < 60 km | 20 |

| IV-LMLR (Large magnitude and large distance) | 6.5 < Mw < 7.0 | 30 km< R < 60 km | 20 |

Table 2.

Intensity measures considered in this study.

Table 2.

Intensity measures considered in this study.

| Intensity Measure | Description | Units |

|---|

| PGA | Peak ground acceleration | g |

| PGD | Peak ground displacement | cm |

| PGV | Peak ground velocity | cm/s |

| Sa02 | Spectral acceleration at 0.2 s | g |

| Sa1 | Spectral acceleration at 1.0 s | g |

| SaT | Spectral acceleration at natural period | g |

Table 3.

Specifications for piles.

Table 3.

Specifications for piles.

| Pile Type | Diameter (m) | Section Information |

|---|

| Cast in situ (CIS) pile | 0.8 | The pile is circular and is cast by concrete with Chinese grade C40, the compressive strength of which is taken as 26.8 MPa. The pile section is reinforced by 18 HRB400 bars with a diameter of 20 mm. The transverse reinforcement is provided by the HPB 300 bars with a diameter of 16 mm at a pitch of 100 mm. The yield strengths of Chinese grade HRB400 and HPB300 are 400 MPa and 300 MPa, respectively. |

| Prestressed high-strength concrete (PHC) pipe pile | 1.0 | C80 concrete, which has a compressive strength of 50.2 MPa, is utilized for the PHC pile. The section is reinforced by 32 prestressing tendons with a diameter of 9 mm, whose maximum tensile strength is 1420 MPa. The thickness of the pile is 130 mm. The spacing of HPB300 confining the steel along the pile axis is 80 mm. |

| Steel pipe pile | 1.2 | Q345, which is a Chinese-grade material with a yield strength of 345 MPa, is utilized as structural steel for the pipe pile. The thickness of the pile is 22 mm. |

Table 4.

Soil properties for the wharf case study.

Table 4.

Soil properties for the wharf case study.

| Soil Unit | φ (°) | Effective Soil Weight (kN/m3) |

|---|

| Fine medium sand | 32.1 | 9.2 |

| Medium dense sand | 34.0 | 10.0 |

| Dense sand | 36.0 | 10.5 |

| Gravelly sand | 38.2 | 11.1 |

Table 5.

Probabilistic seismic demand models for cast in situ pile-supported wharves.

Table 5.

Probabilistic seismic demand models for cast in situ pile-supported wharves.

| Angle θ | Ll = 51 m | Ll = 91 m | Ll = 131 m |

|---|

| PSDM | βD|IM | R2 | PSDM | βD|IM | R2 | PSDM | βD|IM | R2 |

|---|

| 0° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.77ln(PGD) + 0.78 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.79 | 0.30 | 0.91 |

| 15° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.78 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.79 | 0.31 | 0.91 |

| 30° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.80 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 45° | 0.78ln(PGD) + 0.74 | 0.28 | 0.92 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.81 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 60° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 75° | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 90° | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.78 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.81 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 105° | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.83 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 120° | 0.77ln(PGD) + 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.83 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.90 |

| 135° | 0.78ln(PGD) + 0.77 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.91 |

| 150° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.74 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.77ln(PGD) + 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.78 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

| 165° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.76ln(PGD) + 0.78 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.91 |

Table 6.

Probabilistic seismic demand models for PHC pipe pile-supported wharves.

Table 6.

Probabilistic seismic demand models for PHC pipe pile-supported wharves.

| Angle θ | Ll = 51 m | Ll = 91 m | Ll = 131 m |

|---|

| PSDM | βD|IM | R2 | PSDM | βD|IM | R2 | PSDM | βD|IM | R2 |

|---|

| 0° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.93 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.93 |

| 15° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.93 |

| 30° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.93 |

| 45° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.93 |

| 60° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.93 |

| 75° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.74ln(PGD) + 0.66 | 0.45 | 0.88 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.60 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

| 90° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

| 105° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

| 120° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.61 | 0.29 | 0.93 |

| 135° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.83ln(PGD) + 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.90 |

| 150° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.92 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

| 165° | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.93 | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

Table 7.

Probabilistic seismic demand models for steel pipe pile-supported wharves.

Table 7.

Probabilistic seismic demand models for steel pipe pile-supported wharves.

| Angle θ | Ll = 51 m | Ll = 91 m | Ll = 131 m |

|---|

| PSDM | βD|IM | R2 | PSDM | βD|IM | R2 | PSDM | βD|IM | R2 |

|---|

| 0° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.87 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

| 15° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.91 |

| 30° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.92 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.91 |

| 45° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.91 |

| 60° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.92 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.92 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.91 |

| 75° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.92 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.91 |

| 90° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.91 |

| 105° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.91 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

| 120° | 0.83ln(PGD) + 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.90 |

| 135° | 0.82ln(PGD) + 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

| 150° | 0.83ln(PGD) + 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

| 165° | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.89 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

Table 8.

Limit states for this study.

Table 8.

Limit states for this study.

| Damage Limit States | Limit State I | Limit State II | Limit State III |

|---|

| Description | The structure exhibits a near-elastic response with minor or no residual deformation. The serviceability of the structure is not interrupted after earthquake. | The structure suffers limited inelastic deformations. The loss of serviceability is no more than several months. | The structure continues to support gravity loads. The egress is not prevented. |

| Concrete compression strain limits for CIS and PHC pile | | | |

Steel tensile strain limits for

CIS and PHC pile | | | |

Steel tensile strain limits for

steel pipe pile | | | |

Table 9.

Displacement capacities of different limit states (unit: cm).

Table 9.

Displacement capacities of different limit states (unit: cm).

| Wharf Type | Limit State I | Limit State II | Limit State III |

|---|

| CIS pile-supported wharf | 5.06 | 11.93 | 17.50 |

| PHC pile-supported wharf | 4.52 | 6.24 | 9.02 |

| Steel pipe pile-supported wharf | 6.70 | 11.95 | 22.87 |

Table 10.

Values of βD|IM, b, ζ, and R2 for Method A.

Table 10.

Values of βD|IM, b, ζ, and R2 for Method A.

| Wharf Type | IM | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m |

|---|

| βD|IM | R2 | b | ζ | βD|IM | R2 | b | ζ | βD|IM | R2 | b | ζ |

|---|

| CIS pile-supported wharf | PGA | 0.84 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.29 | 0.80 | 1.04 | 0.82 | 0.28 | 0.78 | 1.05 |

| PGD | 0.26 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.42 |

| PGV | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.10 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 1.05 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 1.02 | 0.52 |

| Sa02 | 0.85 | 0.29 | 0.82 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0.77 | 1.09 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 1.11 |

| Sa1 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 1.13 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 1.09 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.75 | 1.07 | 0.45 |

| SaT | 0.47 | 0.78 | 1.11 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.77 | 1.06 | 0.44 |

| PHC pile-supported wharf | PGA | 0.81 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.38 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.84 |

| PGD | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.36 |

| PGV | 0.45 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 0.39 |

| Sa02 | 0.82 | 0.36 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.36 | 0.93 | 0.88 |

| Sa1 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.15 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 1.14 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 1.15 | 0.43 |

| SaT | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.12 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 1.12 | 0.44 |

| Steel pile-supported wharf | PGA | 0.80 | 0.43 | 1.05 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 1.04 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.43 | 1.03 | 0.75 |

| PGD | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.41 |

| PGV | 0.44 | 0.82 | 1.20 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.83 | 1.18 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 0.37 |

| Sa02 | 0.81 | 0.41 | 1.01 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.79 |

| Sa1 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 1.14 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 1.11 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 1.16 | 0.49 |

| SaT | 0.57 | 0.71 | 1.10 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 1.07 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 1.07 | 0.53 |

Table 11.

Values of βD|IM, b, ζ, and R2 for Method B.

Table 11.

Values of βD|IM, b, ζ, and R2 for Method B.

| Wharf Type | IM | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m |

|---|

| βD|IM | R2 | b | ζ | βD|IM | R2 | b | ζ | βD|IM | R2 | b | ζ |

|---|

| CIS pile-supported wharf | PGA | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.75 | 1.03 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.75 | 1.03 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.75 | 1.03 |

| PGD | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| PGV | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 0.51 |

| Sa02 | 0.78 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 1.09 | 0.78 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 1.09 | 0.78 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 1.09 |

| Sa1 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.36 |

| SaT | 0.27 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.26 |

| PHC pile-supported wharf | PGA | 0.74 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| PGD | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.74 |

| PGV | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.45 |

| Sa02 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.91 |

| Sa1 | 0.41 | 0.80 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.40 |

| SaT | 0.41 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.40 |

| Steel pile-supported wharf | PGA | 0.93 | 0.35 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.35 | 1.02 | 0.91 |

| PGD | 0.47 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.58 |

| PGV | 0.60 | 0.73 | 1.20 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 1.20 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 1.20 | 0.50 |

| Sa02 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.95 |

| Sa1 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 1.04 | 0.74 |

| SaT | 0.79 | 0.54 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 1.02 | 0.77 |

Table 12.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to Mw from Method A.

Table 12.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to Mw from Method A.

| IM | CIS Pile-Supported Wharf | PHC Pile-Supported Wharf | Steel Pile-Supported Wharf |

|---|

| L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m |

|---|

| PGA | 4.1 × 10−7 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 3.1 × 10−7 | 5.1 × 10−7 | 6.0 × 10−7 | 6.8 × 10−7 | 1.4 × 10−6 | 1.4 × 10−6 | 1.1 × 10−6 |

| PGD | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.95 |

| PGV | 7.95 × 10−3 | 6.35 × 10−3 | 5.47 × 10−3 | 9.2 × 10−3 | 0.01 | 0.012 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Sa02 | 2.9 × 10−7 | 2.3 × 10−7 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 3.7 × 10−7 | 4.4 × 10−7 | 5.2 × 10−7 | 6.8 × 10−7 | 8.3 × 10−7 | 8.5 × 10−7 |

| Sa1 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−4 | 1.5 × 10−4 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 4.8 × 10−4 | 5.6 × 10−4 | 2.5 × 10−3 |

| SaT | 3.9 × 10−5 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 4.5 × 10−5 | 4.9 × 10−5 | 5.9 × 10−5 | 7.6 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 1.8 × 10−4 |

Table 13.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to R from Method A.

Table 13.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to R from Method A.

| IM | CIS Pile-Supported Wharf | PHC Pile-Supported Wharf | Steel Pile-Supported Wharf |

|---|

| L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m |

|---|

| PGA | 0.054 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.049 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| PGD | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.052 | 0.053 | 0.07 |

| PGV | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.77 |

| Sa02 | 0.048 | 0.052 | 0.06 | 0.045 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Sa1 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.997 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.65 |

| SaT | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.949 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

Table 14.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to Mw from Method B.

Table 14.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to Mw from Method B.

| IM | CIS Pile-Supported Wharf | PHC Pile-Supported Wharf | Steel Pile-Supported Wharf |

|---|

| L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m |

|---|

| PGA | 4.8 × 10−5 | 4.5 × 10−5 | 4.5 × 10−5 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 8.1 × 10−5 | 8.1 × 10−5 | 7.9 × 10−5 |

| PGD | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.43 |

| PGV | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Sa02 | 3.4 × 10−5 | 3.5 × 10−5 | 3.5 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 6.8 × 10−5 | 6.8 × 10−5 | 6.8 × 10−5 |

| Sa1 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| SaT | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.014 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Table 15.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to R from Method B.

Table 15.

Comparison of the sufficiency results with respect to R from Method B.

| IM | CIS Pile-Supported Wharf | PHC Pile-Supported Wharf | Steel Pile-Supported Wharf |

|---|

| L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m | L1 = 51 m | L1 = 91 m | L1 = 131 m |

|---|

| PGA | 0.056 | 0.06 | 0.059 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| PGD | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| PGV | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.591 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Sa02 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Sa1 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| SaT | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

Table 16.

Probabilistic seismic demand models generated from Methods A and B.

Table 16.

Probabilistic seismic demand models generated from Methods A and B.

| Method | Segment Length | CIS Pile-Supported Wharf | PHC Pile-Supported Wharf | Steel Pile-Supported Wharf |

|---|

| Method A | L1 = 51 m | 0.77ln(PGD) + 0.79 | 0.79ln(PGD) + 0.66 | 0.80ln(PGD) + 0.54 |

| L1 = 91 m | 0.75ln(PGD) + 0.86 | 0.77ln(PGD) + 0.68 | 0.78ln(PGD) + 0.59 |

| L1 = 131 m | 0.73ln(PGD) + 0.88 | 0.78ln(PGD) + 0.65 | 0.78ln(PGD) + 0.59 |

| Method B | L1 = 51 m | 0.62ln(PGD) + 1.28 | 0.62ln(PGD) + 1.17 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.81 |

| L1 = 91 m | 0.62ln(PGD) + 1.13 | 0.62ln(PGD) + 0.99 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.69 |

| L1 = 131 m | 0.62ln(PGD) + 0.82 | 0.62ln(PGD) + 0.67 | 0.81ln(PGD) + 0.38 |