History of Open Space and Physical Activities of China’s Danwei Neighborhood: The Case Study of Community Hua

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Open Space in Danwei Neighborhoods

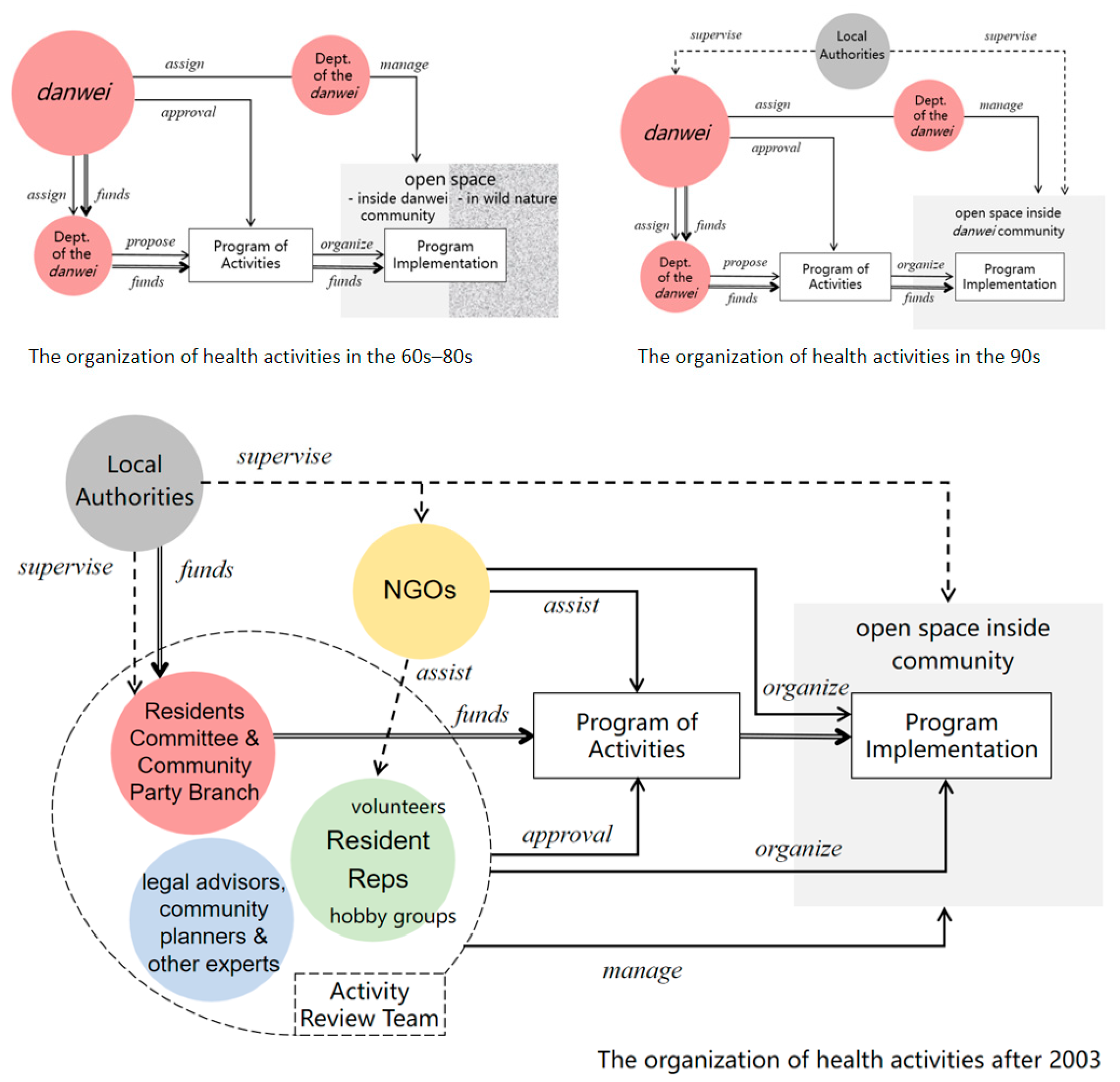

2.2. Health-Promoted Activities in Danwei Communities

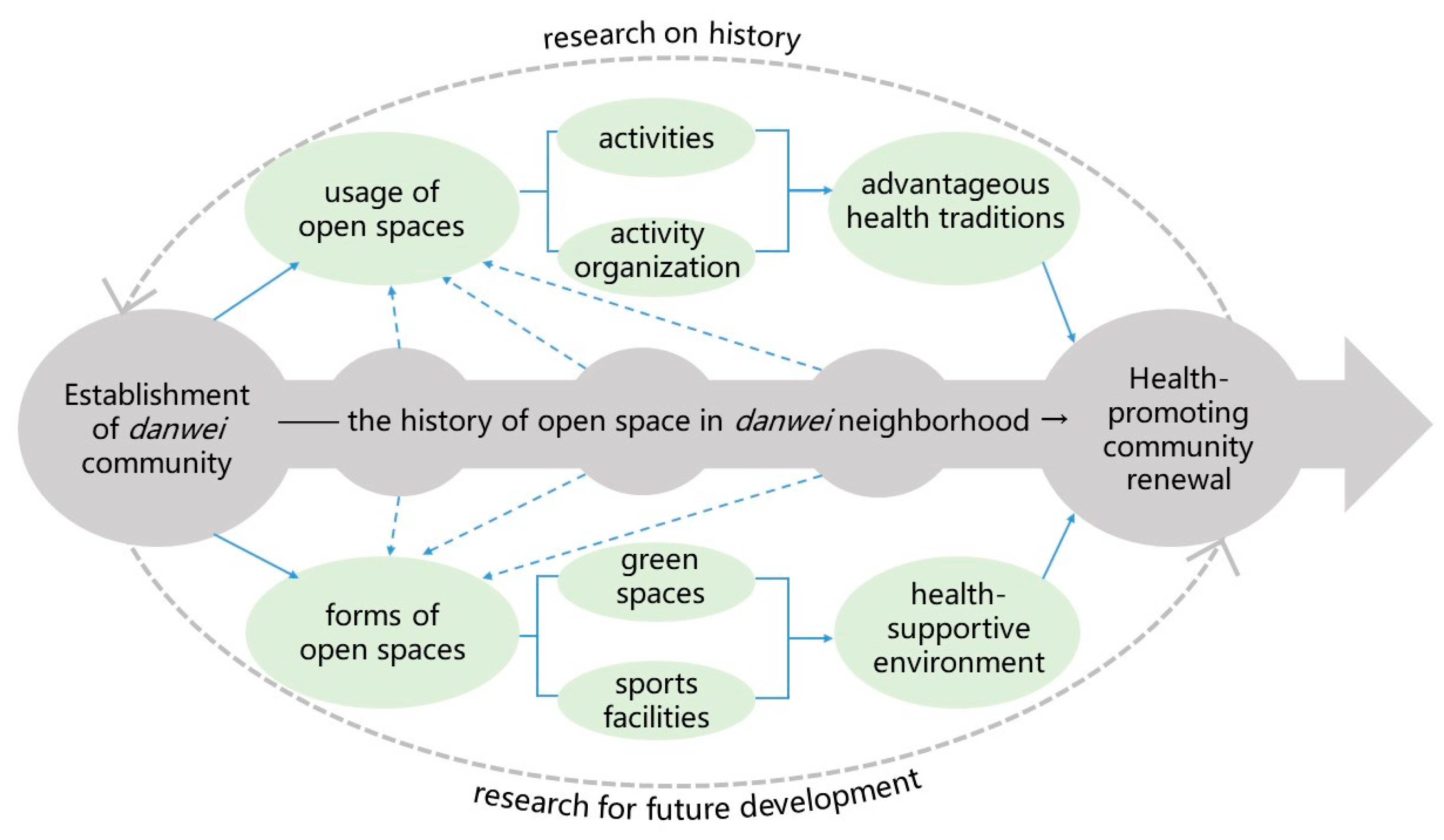

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Selection

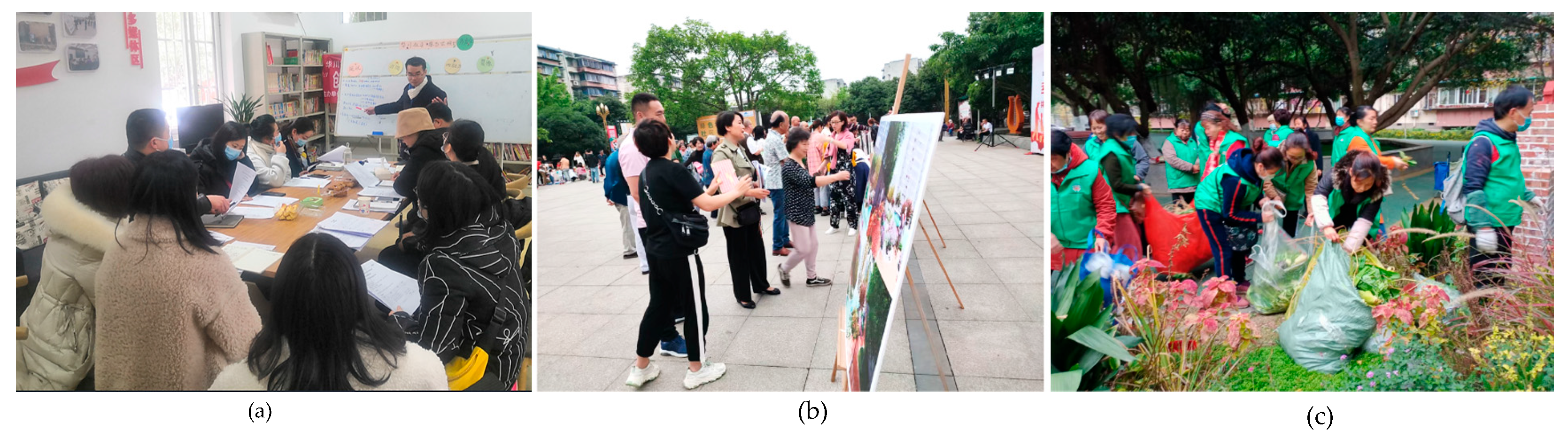

3.2. Data Collection

4. Findings: The Health Heritage in Danwei Neighborhood

4.1. The Tangible Legacy: Physical Conditions of Open Space

The living conditions were very difficult when the factory was first built. Nobody had anywhere to go after work… The young people gathered together and wanted to have a venue for activities, so we decided to fill in a recess in front of the school and built a basketball court. It was planned and constructed by the workers. Afterwards, basketball and volleyball became very popular, and the factory’s team played well in local sports games.(Interview A05)

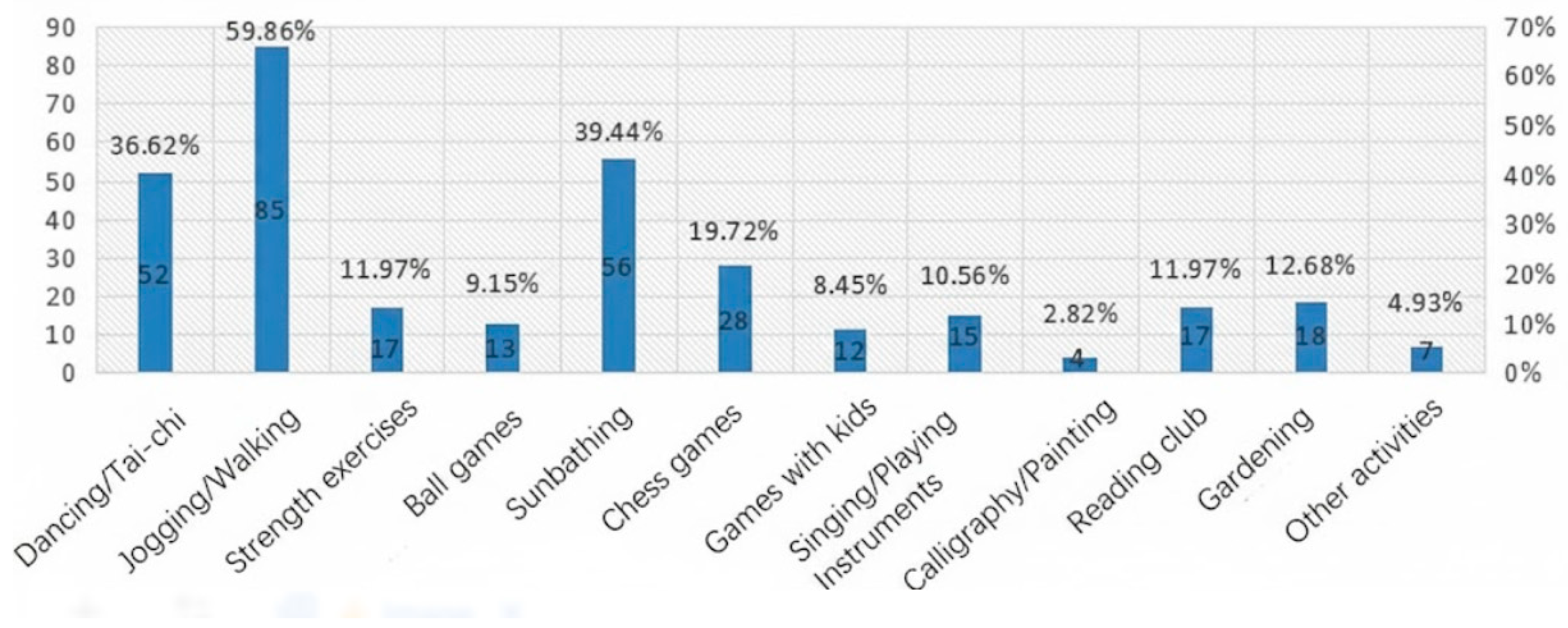

4.2. The Intangible Legacy: Traditions of Outdoor Activities

Our factory sports teams used to be famous among fellow danwei. When the workers in our basketball, volleyball, and publicity teams retired in recent years, their specialty and love for sports, singing, and dancing still exist, so they are keen to organize hobby groups among retired workers.(Interview A06)

5. Renewal Strategies Based on Health Heritage

6. Conclusions

6.1. Health Heritage of Danwei Community

6.2. Targeted Renewal Strategies

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, M.; Shi, L.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Lin, D.; Chang, Y.; Yan, S.; Peng, Y.; Feng, T. Perceptions of improvements and mental health outcomes of micro-renewal in old Danwei community: A survey of residents in Hengyang, China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1419267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delshad, A.B. Community gardens: An investment in social cohesion, public health, economic sustainability, and the urban environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvie-Sebileau, P.; Rees, D.; Tipene-Leach, D.; D’Souza, E.; Swinburn, B.; Gerritsen, S. Community co-design of regional actions for children’s nutritional health combining Indigenous knowledge and systems thinking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.J.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Frumkin, H. Health and the built environment: 10 years after. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1542–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Jiao, S.; Zhang, R. High-density communities and infectious disease vulnerability: A built environment perspective for sustainable health development. Buildings 2023, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Healthy China Action—Healthy Environment Promotion Action Implementation Plan (2025–2030); National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Land Institute. Building Healthy Places Toolkit: Strategies for Enhancing Health in the Built Environment; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Urban Green Spaces: A Brief for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344116 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Tianjin Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Urban Design Guidelines for Tianjin New Community Pilot Projects (for Trial Implementation); Tianjin Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau: Tianjin, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Planning and Land Resources Administration Bureau. Planning and Design Guidelines for Large-scale Residential Communities in Shanghai (for Trial Implementation); Shanghai Municipal Planning and Land Resources Administration Bureau: Shanghai, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Yu, G. Overlapping modernity and tradition: Rethinking the danwei as a basic urban unit in modern China. Plan. Perspect. 2024, 39, 1267–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chai, Y. Daily life circle reconstruction: A scheme for sustainable development in urban China. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, T.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, M. Rethinking the Spatial Prototype and Operational Organization of the Chinese Danwei System from a Collective Perspective. In The Socio-spatial Design of Community and Governance: Interdisciplinary Urban Design in China; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, N.; Kita, M.; Matsubara, S.; Okyere, S.A.; Shimoda, M. Socio-Spatial changes in Danwei Neighbourhoods: A case study of the AMS Danwei compound in Hefei, China. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Rosenberg, M.W. Aging and the changing urban environment: The relationship between older people and the living environment in post-reform Beijing, China. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, E. The danwei: Socio-spatial characteristics of work units in China’s urban society. Econ. Geogr. 1986, 62, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D. Remaking Chinese Urban Form: Modernity, Scarcity and Space 1949–2005; Routledge: Abington-on-Thames, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, T.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y. Transforming public spaces in post-socialist China’s Danwei neighbourhoods: The third dormitory of the Party Committee of Shandong Province. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. On the patterns of changes in Shougang industrial landscape (1919–2019). Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 3, 15–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Song, P. Impact of green infrastructure in smart older adult care communities on the health of the older adult and the exploration of optimization paths. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1601102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Soares, R.; Barbosa, L.; Silva, A.; Ferreira, R.; Terroso, S.; Andriolli, A.; Silva, L.; Ribeiro, C. Green Environments and Healthy Aging: Analyzing the Role of Green Infrastructure in the Functional Well-Being of Seniors—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Lu, N. Community social capital and self-rated health among older adults in urban China: The moderating roles of instrumental activities of daily living and smoking. Ageing Soc. 2025, 45, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dijst, M.; Van Acker, V.; Chai, Y. Understanding effects of daily activity on neighborhood belongingness: A Chinese perspective. Cities 2025, 158, 105680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Lin, Z. From traditional and socialist work-unit communities to commercial housing: The association between neighborhood types and adult health in urban China. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 53, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Investigation research on the current situation of physical activities among residents in varieties of community of cities in China. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2005, 28, 1009–1013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.; Song, J.; Xu, T. From “spatial bond” to “spatial mismatch”: An assessment of changing jobs–housing relationship in Beijing. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Lü, B.; De Roo, G. Impact of the jobs-housing balance on urban commuting in Beijing in the transformation era. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, X. Research on the strategy of elderly friendly landscape renewal in unit community under social transformation—A case study of Chongqing Cotton Mill Community. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 26, 95–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sun, W.; Wu, Y. Study on the impact of subjective perception of urban environment on residents’ health: Based on a large sample survey of 60 counties and cities in China. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 35, 55–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, J.; Zhao, Y. Physical health, community social capital and the subjective well-being of the elderly in danwei community. J. Popul. Econ. 2018, 3, 67–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Tao, X.; Zhou, S. The residential differentiation of residents’ obesity: A case study of Guangzhou. Trop. Geogr. 2020, 40, 487–497. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P. A socio-economic-cultural exploration on open space form and everyday activities in danwei: A case study of Jingmian compound, Beijing. Urban Des. Int. 2014, 19, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, L. Planning Advancement Strategy for Living Space and Environment of Aging Community Under Perspective of Community Life Circle. Urban. Archit. 2018, 36, 17–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G.; Gao, Y.; Xue, C.Q.; Xu, L. “Third Front” construction in China: Planning the industrial towns during the Cold War (1964–1980). Plan. Perspect. 2021, 36, 1149–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.; Cai, J.; Muller, L.; Luo, B. Peri-Urbanization in Chengdu, Western China: From “Third Line” to Market Dynamics; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. Adjustment and transformation of the third front projects and the development of key regional cities. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 46–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. The third front projects and urban development in Sichuan and Chongqing. Theory Mon. 2017, 9, 122–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Party History Research Office of the CPC Chengdu Municipal Committee. The Third Front Projects and the Development of Chengdu’s Pillar Industries; Party History Research Office of the CPC Chengdu Municipal Committee: Chengdu, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D. Social Space and Governance in Urban China: The Danwei System from Origins to Reform; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shieh, L.; Friedmann, J. Restructuring urban governance: Community construction in contemporary China. City 2008, 12, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengdu Bureau of Statistics. New Features and New Trends of Chengdu’s Population Development; Chengdu Bureau of Statistics: Chengdu, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Mou, Y. Research on the Associations between Community Built Environment and Health Outcomes of the Elderly: Mechanism of Action and Empirical Results. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2, 52–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gascon, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martínez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Forns, J.; Plasència, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4354–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lu, R.; Guo, L.; Liu, B. Social Capital and Mental Health in Rural and Urban China: A Composite Hypothesis Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Kondo, N.; Aida, J.; Kawachi, I.; Koyama, S.; Ojima, T.; Kondo, K. Development of an instrument for community-level health-related social capital among Japanese older people: The JAGES Project. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morán Uriel, J.; Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. Urban horizons in China: Challenges and opportunities for community intervention in a country marked by the heihe-tengchong line. In Diversity as Catalyst: Economic Growth and Urban Resilience in Global Cityscapes; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Du, S.; Wang, R. Social factors and residential satisfaction under urban renewal background: A comparative case study in Chongqing, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2022, 148, 05022030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Sex | Social Role in the Community | Years of Stay in the Community |

|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | M | Retired secretary of the construction department of the danwei | Since 1972 |

| A02 | M | Retired staff member of the construction department of the danwei | Since 1970 |

| A03 | M | Retired director of the production department of the danwei | Since 1977 |

| A04 | F | Retired staff member of the management department of the danwei | Since 1970 |

| A05 | M | Retired party branch secretary of the danwei | Since 1968 |

| A06 | M | Retired main director of the danwei | Since 1967 |

| B01 | F | Director of the community committee | Since 2003 |

| B02 | M | Deputy director of the community committee | Since 2013 |

| C01 | M | Director of an NGO based in the community | Since 2019 |

| C02 | F | Staff member of an NGO based in the community | Since 2019 |

| Name | Area m2 | Quan | Feature | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.Central square | 5800 | 1 | Planned in the 1993 plan, following the tradition of having central sport venue in the danwei community |  |

| b1.Children’s garden and sports facilities | 1300 | 1 | Using the land of unbuilt kindergarten, developed after 2003 by the Committee | |

| b2.Public posting area | 300 | 1 | Using the land of unbuilt hotel, developed after 2003 by the Committee | |

| b3.Leisure sports area | 1500 | 1 | Using the land of unbuilt track field, developed after 2003 by the Committee | |

| c. Small open space | 80–200 | Multi | Using land between apartments, developed continuously by the residents |

| Features of Outdoor Activities | Choices | |

|---|---|---|

| The choice of an open space for outdoor activities | Open spaces inside the community | 43.9% |

| Pocket parks close to the community | 33.2% | |

| Large urban and suburban parks | 23.0% | |

| The number of companions in outdoor activities | More than 3 | 77.0% |

| No more than 3 | 17.0% | |

| Alone | 6% | |

| Frequency of outdoor activities | More than 2 times per day | 65.3% |

| Once a day | 20.4% | |

| Once every two to three days | 11.2% | |

| No more than once in a week | 3.1% | |

| Length of single outdoor activity | ≥1 h | 56.0% |

| Between 30 min and 1 h | 41.0% | |

| Less than 30 min | 3.0% | |

| Physical intensity of outdoor activities | High intensity (basketball, volleyball, cycling, etc.) | 2.9% |

| Moderate intensity (jogging, leisure dance, Tai Chi, etc.) | 40.8% | |

| Low intensity (walking, chess and card games, singing, chatting, etc.) | 56.3% |

| 1960s–1990s | After 2003 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of activities | Sports (in competition and daily workout) | 5.8% | 12.4% |

| Cultural events (outdoor parties, etc.) | 8.3% | 10.1% | |

| Cleaning (sanitation campaign, etc.) | 31.1% | 25.8% | |

| Greening (arbor day, gardening, etc.) | 2.5% | 11.8% | |

| Community governance (the selection of model residential buildings, etc.) | 53.3% | 34.8% | |

| Educational activities | 2.5% | 3.9% | |

| Other types of activities | 0 | 0 | |

| Never participated | 0.8% | 1.1% | |

| Motivation of participation | Required by the danwei/residential Committee | 61.2% | 38.4% |

| Personal interests or needs | 30.6% | 27.7% | |

| Pursuing a sense of community | 8.2% | 29.4% | |

| Attracted by material awards | 0 | 4.5% | |

| Other reasons | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heng, H.; He, X.; Mo, N. History of Open Space and Physical Activities of China’s Danwei Neighborhood: The Case Study of Community Hua. Buildings 2025, 15, 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213953

Heng H, He X, Mo N. History of Open Space and Physical Activities of China’s Danwei Neighborhood: The Case Study of Community Hua. Buildings. 2025; 15(21):3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213953

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeng, Hanxiao, Xuan He, and Nina Mo. 2025. "History of Open Space and Physical Activities of China’s Danwei Neighborhood: The Case Study of Community Hua" Buildings 15, no. 21: 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213953

APA StyleHeng, H., He, X., & Mo, N. (2025). History of Open Space and Physical Activities of China’s Danwei Neighborhood: The Case Study of Community Hua. Buildings, 15(21), 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213953