Experimental Study on the Evolution and Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Chinese Fir Under Long-Term Service

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Hygroscopic Behavior Testing Method

2.3. Mechanical Properties Testing Method

2.4. Chemical Composition and Microstructure

2.4.1. Measurement of Crystallinity

2.4.2. Measurement of Chemical Components

2.4.3. Observation of Microstructure

3. Measurement Results of Mechanical Properties

3.1. Hygroscopic Behavior Properties

3.2. Mechanical Properties

4. Research on Mechanism

4.1. Comparison of Crystallinity

4.2. Chemical Composition

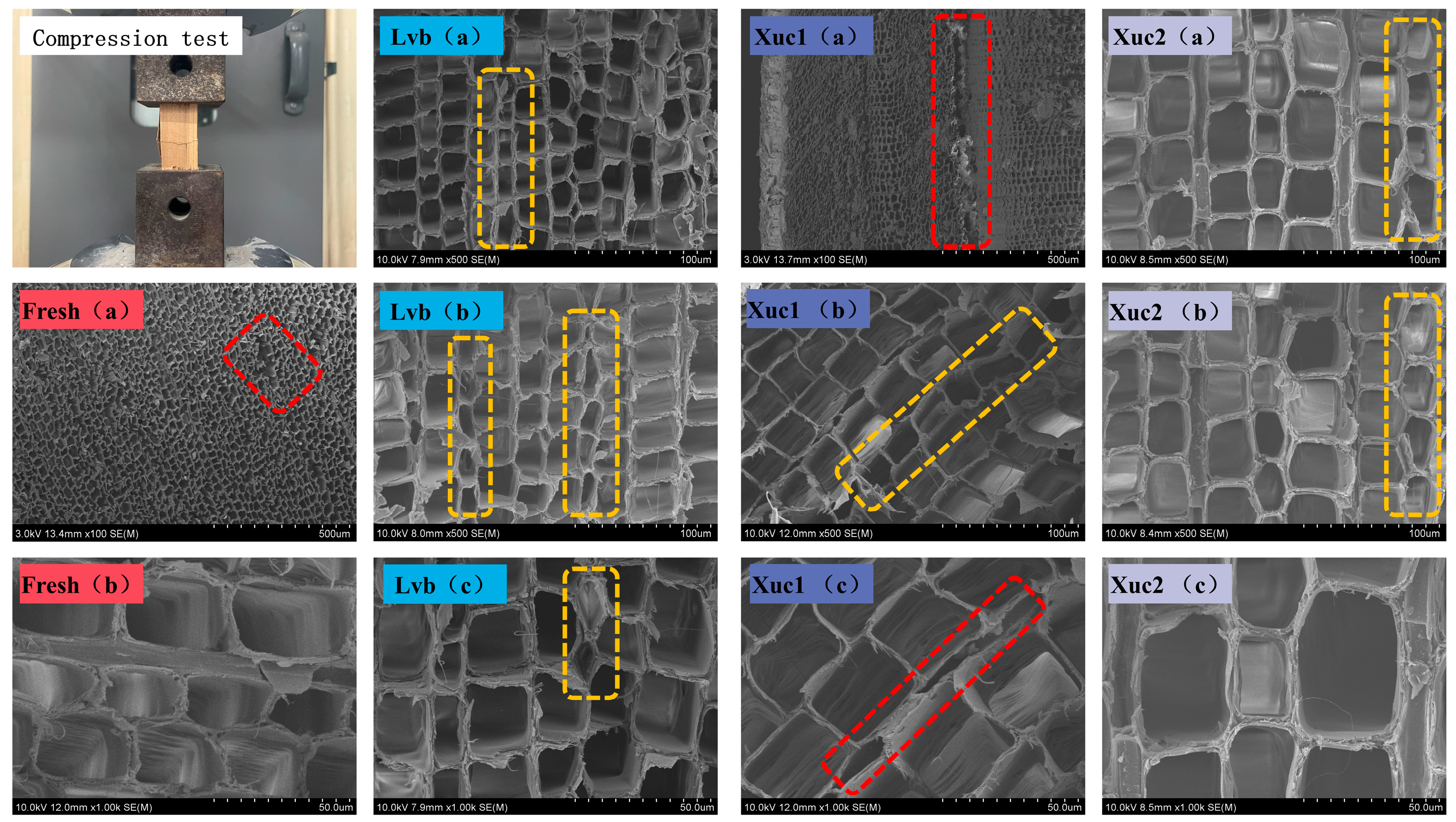

4.3. Microstructural

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The moisture absorption behavior and the longitudinal and bending mechanical properties of Chinese fir undergo significant changes after long-term service. The anisotropic mechanical response shows a Chinese fir trend of directional dependence and non-uniformity, rather than a uniform strengthening trend. Longitudinal and bending strengths generally increase with service duration, whereas certain transverse properties, such as the radial compressive strength of Xuc1, show slight reductions. And the positive impact of long-term service on the mechanical properties of Chinese fir is supported by changes in chemical composition and microstructure.

- (2)

- Aging induces degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose and relative enrichment of extractives, resulting in an increase in cellulose crystallinity with increasing service time. SEM observation shows that microstructural changes, such as interlayer separation and cell wall collapse, contribute to the densification of the aged Chinese fir timber. The changes in crystallinity and microstructure support the trend of mechanical properties of aged Chinese fir, especially the positive impact on mechanical properties.

- (3)

- The comprehensive characterization of the anisotropic mechanical properties of long-term aged Chinese fir provides a robust basis for non-destructive evaluation and targeted reinforcement of historic timber structures, thereby enhancing their structural safety and preservation. Moreover, these findings offer critical guidance for the safe reuse of aged timber, facilitating sustainable restoration practices while preserving both the structural integrity and cultural heritage of historic buildings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Guan, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xin, Z. Nondestructive testing of defect condition of wall wood columnsin Yangxin Hall of the Palace Museum, Beijing. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2021, 43, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Yang, N. Strength degradation and service life prediction of timber in ancient Tibetan building. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2018, 76, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Xue, J.; Zhang, X. Seismic vulnerability analysis of damaged ancient timber structures. J. Vib. Eng. 2023, 36, 1390–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Yang, N.; Hu, H.; Zhang, L. Study on dynamic characteristics of a damaged ancient timber structure of Ming-Qing Dynasty. J. Build. Struct. 2018, 39, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yi, D.; Chen, J.; An, R. Analysis on dynamic characteristics and seismic response of Lingguan deity hall in Qingcheng Mountain by considering effects of wall. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 43, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderegger, W.; Kranitz, K.; Bues, C.-T.; Niemz, P. Aging effects on physical and mechanical properties of spruce, fir and oak wood. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Lu, W.; Wu, Q.; Huang, J.; Jia, C.; Wang, K.; Feng, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, F. Influence of wood species and natural aging on the mechanics properties and microstructure of wood. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Fu, R.; Zong, Y.; Ke, D.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W. Effects of natural ageing on macroscopic physical and mechanical properties, chemical components and microscopic cell wall structure of ancient timber members. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorur, H.; Kurt, S.; Yumrutas, H.I. The Effect of Aging on Various Physical and Mechanical Properties of Scotch Pine Wood Used in Construction of Historical Safranbolu Houses. Drv. Ind. 2014, 65, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witomski, P.; Krajewski, A.; Kozakiewicz, P. Selected mechanical properties of Scots pine wood from antique churches of Central Poland. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2014, 72, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Wang, Z.; Chang, P. Experimental study on mechanical properties of small clear specimens of aged Tibetan populus cathayana. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 43, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Li, P.; Law, S.S.; Yang, Q. Experimental Research on Mechanical Properties of Timber in Ancient Tibetan Building. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2012, 24, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohara, J. Studies on the durability of wood—I. Mechanical properties of old timbers. (Horyuji Temple construction timbers Chamaecyparis obtusa Endlicher). Sci. Rep. Kyoto Prefect. Univ. Agric. Jpn. 1952, 2, 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wu, Q.; Lu, W.; Zhang, J.; Yue, Z.; Jie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Ji, W.; Wu, J. Effects of different accelerated aging modes on the mechanical properties, color and microstructure of wood. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Long, K.; Chu, S.; Lin, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T. Effects of Natural Aging on the Cell Wall Structure and Chemical Composition of Ancient Architectural Wood. Chin. J. Wood Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingling Fanshendong Village Preserves an Ancient Courtyard from the Jiaqing Period. Available online: https://www.yzcity.gov.cn/cnyz/msgj/202011/e2d4c3fb4e494f169ed733dfb63300f7.shtml (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- The Xu’s Mansion in Lingling Has Been Identified as the Earliest Surviving General’s Mansion in Yongzhou. Available online: https://www.yzcity.gov.cn//cnyz/msgj/201901/d292749b463b41178d833d071bc6dca8.shtml (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- GB/T 1927.3-2021; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 3: Determination of the Growth Rings Width Andatewood Rate of Wood. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 1927.2-2021; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 2: Sampling Methods and General Requirements. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 1927.11-2022; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 11: Determination of Ultimate Stress in Compression Parallel to Grain. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 1927.12-2021; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 12: Determination of Strength in Compression Perpendicular to Grain. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 1927.13-2022; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 13: Determination of the Modulus of Elasticity in Compression Perpendicular to Grain. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 15777-2017; Method for Determination of the Modulus of Elasticity in Compression Parallel to Grain of Wood. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GB/T 1927.9-2022; Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Small Clear Wood Specimens. Part 9: Determination of Bending Strength. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Jia, R.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhao, R.; Ren, H. Relativity of Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Juvenile Woods of 10-Year-Old New Chinese Fir Clones ‘Yang 020’ and ‘Yang 061’. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 57, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, T.H.; Sardela, M.; Lahr, F.A.R. X-ray diffraction on aged Brazilian wood species. Mater. Sci. Eng. B-Adv. Funct. Solid-State Mater. 2019, 246, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 2677.6-94; Fibrous Raw Material. Determination of Solvent Extractives. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1994.

- GB/T 2677.10-1995; Fibrous Raw Material. Determination of Holocellulose. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1995.

- GB/T 744-1989; Pulps. Determination of α-Cellulose. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1989.

- GB/T 2677.8-94; Fibrous Raw Material. Determination of Acid-Insoluble Lignin. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1994.

- Cavalli, A.; Cibecchini, D.; Togni, M.; Sousa, H.S. A review on the mechanical properties of aged wood and salvaged timber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.B.; Guan, C.; Zhang, H.J.; Yu, Y.Z.; Liu, F.L.; Zhou, L.J.; Shen, Y.L. Assessing the density and mechanical properties of ancient timber members based on the active infrared thermography. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 304, 124614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.M.; Pereira, H.M. Wood modification by heat treatment: A review. BioResources 2009, 4, 370–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiniati, I.; Osman, N.B.; Mc Donald, A.G.; Laborie, M.-P. Linear viscoelasticity of hot-pressed hybrid poplar relates to densification and to the in situ molecular parameters of cellulose. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohara, J. Studies on the durability of wood—VI: The change of mechanical properties of old timbers (Chamaecyparis obtuse Endlicher). Sci. Rep. Kyoto Prefect. Univ. Agric. Jpn. 1954, 3, 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Z.; Li, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, J.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, T. Effects of environmental factors on natural aging of timber members of ancient buildings: Ultraviolet radiation, temperature and moisture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 456, 139303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R. Comparative Studies on Wooden Components of Ancient Building and Artificial Light Aging Wood. Master’s thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Fan, X.; Deng, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Hou, T.; Wang, X. Densification of poplar veneer. J. Zhejiang AF Univ. 2013, 30, 536–542. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, R.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z. Influence of density distribution on the compressive strength perpendicular to grain of sandwich-compressed Cunninghamia lanceolata wood. J. Zhejiang AF Univ. 2025, 42, 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Kohara, J.; Okamoto, H. Studies of Japanese old timbers. Sci. Rep. Kyoto Prefect. Univ. Agric. Jpn. 1955, 6, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, M.; Gril, J.; Matsuo, M.; Yano, H.; Sugiyama, J.; Clair, B.; Kubodera, S.; Mistutani, T.; Sakamoto, M.; Ozaki, H. Mechanical characteristics of aged Hinoki wood from Japanese historical buildings. Comptes Rendus Phys. 2009, 10, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Timber Types | Number | EMC (%) | SW (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 70% | 90% | T | R | ||

| Fresh | 6 | 9.27 | 12.33 | 16.07 | 4.12 | 2.67 |

| Lvb | 6 | 8.56 | 11.30 | 14.38 | 3.96 | 2.65 |

| Xuc1 | 6 | 8.22 | 11.18 | 14.47 | 2.97 | 1.96 |

| Xuc2 | 6 | 8.24 | 11.10 | 13.84 | 3.48 | 2.11 |

| Mechanical Properties | Fresh | Lvb | Xuc1 | Xuc2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV | COV | AV | COV | AV | COV | AV | COV | ||

| Compressive strength (MPa) | fl | 24.60 (26) | 0.114 | 27.29 (22) | 0.073 | 35.21 (26) | 0.103 | 42.08 * (9) | 0.028 |

| ft | 2.49 (13) | 0.115 | 2.83 (13) | 0.211 | |||||

| fr | 1.84 (13) | 0.342 | 1.66 (13) | 0.303 | |||||

| Compression modulus (MPa) | El | 9025.94 (26) | 0.154 | 9350.09 (22) | 0.220 | 11,595.86 (26) | 0.247 | 12,053.38 (10) | 0.070 |

| Et | 231.21 (13) | 0.311 | 316.76 (13) | 0.150 | |||||

| Er | 483.04 (13) | 0.285 | 520.88 (13) | 0.129 | |||||

| Poisson’s ratio | νLR | 0.38 * (12) | 0.129 | 0.49 (11) | 0.237 | 0.41 (13) | 0.213 | 0.39 * (4) | 0.098 |

| νLT | 0.46 (13) | 0.238 | 0.58 (11) | 0.240 | 0.48 (13) | 0.083 | 0.46 (5) | 0.229 | |

| νRT | 0.69 (13) | 0.132 | 0.73 (13) | 0.129 | |||||

| νTR | 0.45 (13) | 0.147 | 0.50 (13) | 0.103 | |||||

| Flexural strength (MPa) | fb | 48.47 (12) | 0.189 | 45.43 (20) | 0.192 | 63.82 (12) | 0.121 | 64.36 * (9) | 0.101 |

| Types | Chemistry Components (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extract | Cellulose | Hemicellulose | Lignin | |

| Fresh | 3.15 | 36.53 | 30.88 | 31.19 |

| Lvb | 5.97 | 33.27 | 27.20 | 29.98 |

| Xuc1 | 7.79 | 26.90 | 28.86 | 28.02 |

| Xuc2 | 6.79 | 32.11 | 29.91 | 29.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, Q.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Zou, F. Experimental Study on the Evolution and Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Chinese Fir Under Long-Term Service. Buildings 2025, 15, 4500. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244500

Zou Q, Wang S, Hu J, Zou F. Experimental Study on the Evolution and Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Chinese Fir Under Long-Term Service. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4500. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244500

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Qiong, Shilong Wang, Jiaxing Hu, and Feng Zou. 2025. "Experimental Study on the Evolution and Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Chinese Fir Under Long-Term Service" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4500. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244500

APA StyleZou, Q., Wang, S., Hu, J., & Zou, F. (2025). Experimental Study on the Evolution and Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Chinese Fir Under Long-Term Service. Buildings, 15(24), 4500. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244500