Enhancing Cement Hydration and Mechanical Strength via Co-Polymerization of Sodium Humate with Superplasticizer Monomers and Sequential Blending with Aluminum Sulfate and Carbon Fibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Synthesis of Copolymer and Derivative Admixtures

2.4. Determination of Setting Times of Cement Pastes

2.5. Measurement of Compressive and Flexural Strengths of Cement Mortars

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Admixtures

3.2. Characterizations of Admixtures

3.3. Setting Effects of Admixtures

3.4. Characterizations of Cement, Pastes and Mortars

4. Conclusions

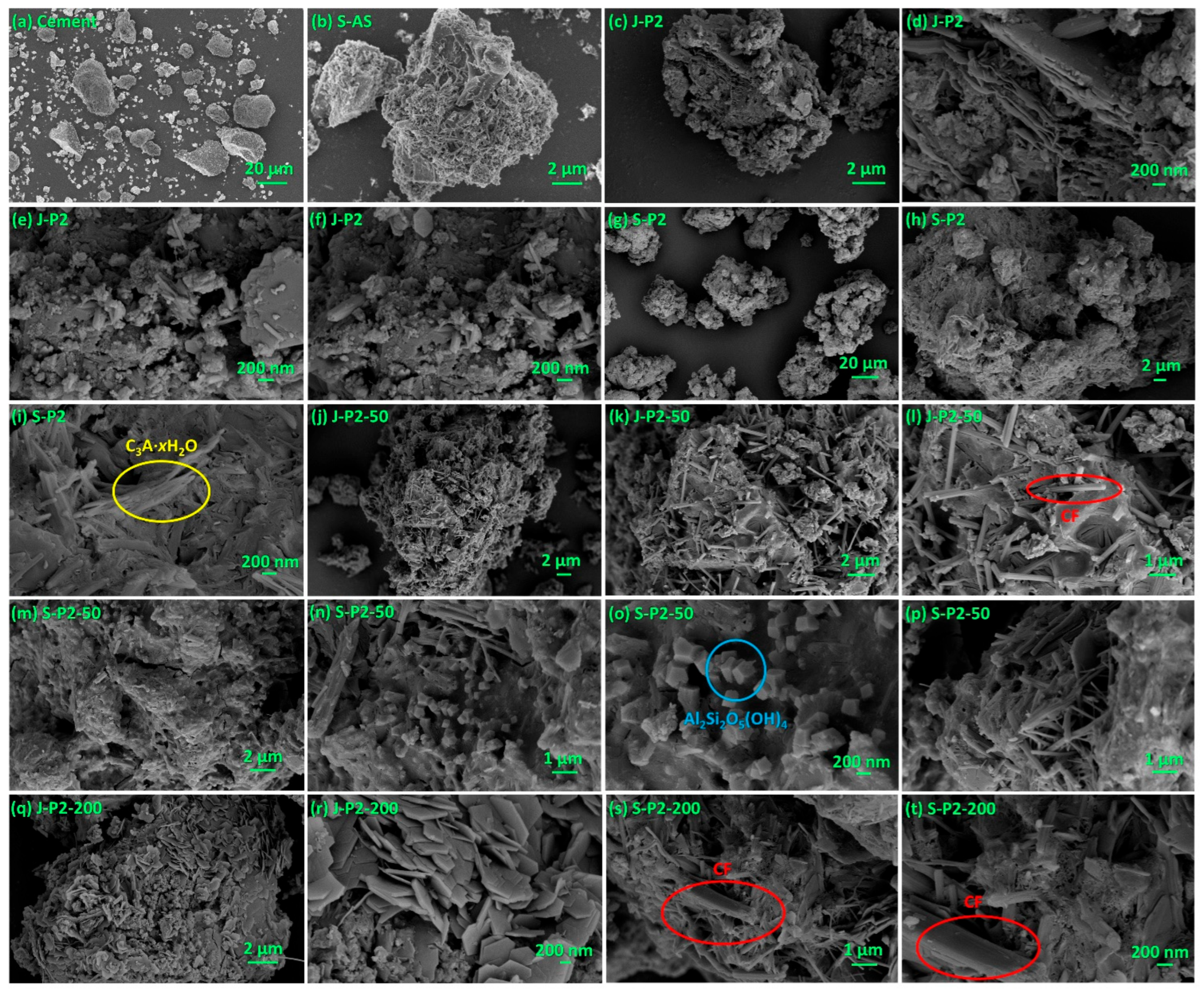

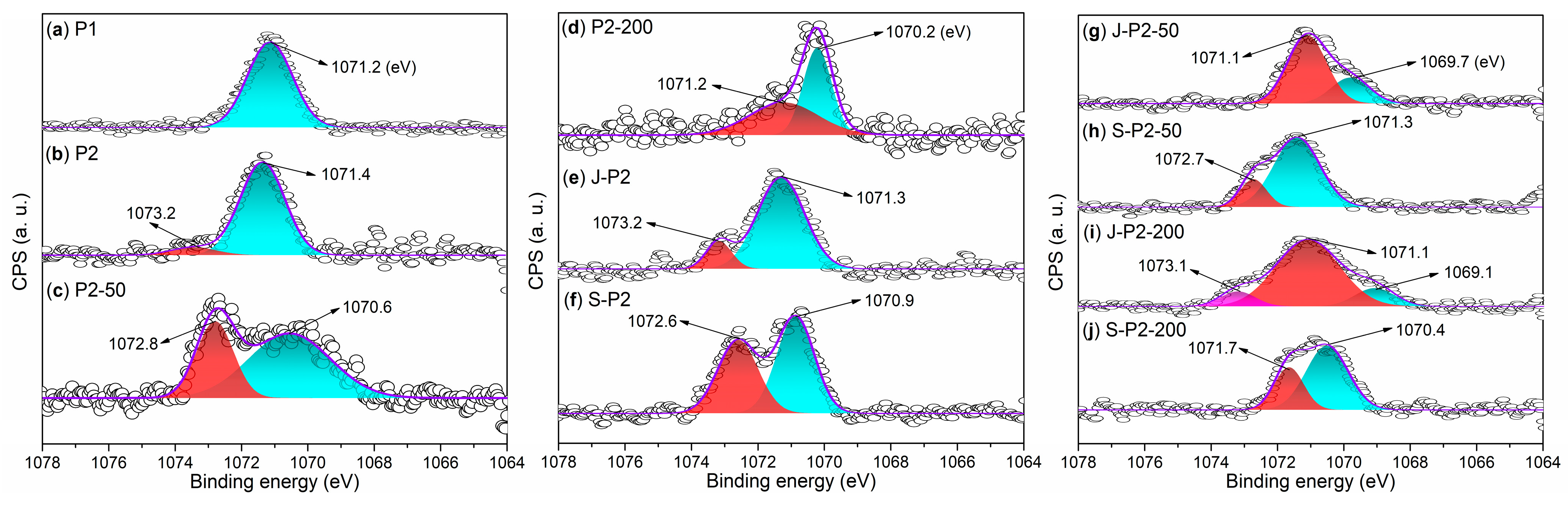

- Under the conditions of aqueous free radical polymerization initiated by ammonium persulfate, sodium humate can copolymerize with sodium 2-methylprop-2-ene-1-sulfonate (SMAS) and 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid (AMPS) to form a highly water-soluble three-dimensional porous copolymer. Using this copolymer as a ligand and complexing it with aluminum sulfate via ball milling, the resulting composite admixture contains active components such as AlO(OH). Compared to pure aluminum sulfate as a setting accelerator, this composite significantly enhances the hydration rate of cement (average initial setting time: 2.62 min; average final setting time: 4.53 min) while markedly improving the mechanical strength of the mortar at 6 h (average compressive strength: 1.7 MPa; average flexural strength: 1.4 MPa). The underlying reason is that, unlike pure aluminum sulfate, the composite additive promotes the formation of a new Al2Si2O5(OH)4 gel phase in the cement paste and a new Ca3Al2O6·xH2O gel phase in the cement mortar.

- Incorporating 50-mesh carbon fibers into the aforementioned sodium humate copolymer-aluminum composite accelerator via ball milling produces an admixture containing two active setting-accelerating components: AlO(OH) and Al2O3. These aluminum-containing species are formed through the hydrolysis of Al3+, released from the aluminum sulfate precursor, to Al(OH)3 during ball milling, followed by its subsequent dehydration. This further accelerates the cement hydration rate (average initial setting time: 2.21 min; average final setting time: 3.93 min). However, compared to the aluminum–sodium humate copolymer accelerator, it slightly reduces the 6 h mechanical strength of the mortar (compressive: 1.5 MPa vs. 1.7 MPa; flexural: 1.0 MPa vs. 1.4 MPa) while significantly enhancing the 24 h mechanical strength (compressive: 5.2 MPa vs. 4.2 MPa; flexural: 2.7 MPa vs. 2.2 MPa). This is attributed to the formation of an Al2Si2O5(OH)4 gel phase in the paste and both Al2Si2O5(OH)4 and Ca3Al2O6·xH2O gel phases in the mortar when 50-mesh carbon fibers are incorporated.

- When 50-mesh carbon fibers are replaced with 200-mesh carbon fibers, the initial setting time of the cement paste mediated by the 200-mesh carbon fiber-doped accelerator is prolonged, although the final setting time remains nearly identical. Additionally, the 6 h compressive and flexural strengths of the mortar decrease. This is because the 200-mesh carbon fiber-doped accelerator promotes the formation of Ca3Al2O6·xH2O and (CaO)X(Al2O3)11 phases in the cement paste, and Ca3Al2O6·xH2O and Ca4Al2O7·xH2O phases in the cement mortar. Evidently, the Al2Si2O5(OH)4 gel phase exhibits superior setting acceleration and reinforcement effects compared to the Ca3Al2O6·xH2O, (CaO)X(Al2O3)11, and Ca4Al2O7·xH2O phases. The mesh size of carbon fibers significantly influences the formation of gel phases. Moreover, excessively fine carbon fibers may hinder the development of early mechanical strength in cement mortar, possibly due to their inability to effectively bridge the larger gaps formed during cement hydration.

- Traditionally, sodium humate, SMAS, and AMPS have been used as retarders in cement hydration, while also functioning as superplasticizers. Carbon fibers, on the other hand, have been reported as reinforcing agents. However, none of these materials have previously been recognized for their setting-accelerating properties. This project, through graft modification of sodium humate followed by blending with aluminum sulfate and carbon fibers, has developed an additive that simultaneously exhibits excellent setting acceleration and reinforcement effects, thereby contributing to the development of a new generation of cement accelerators.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.; Li, N.; Unluer, C.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Z. 200 years of Portland cement: Technological advancements and sustainability challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguera, R.A.; Caprarob, A.P.B.; de Medeirosb, M.H.F.; Carneiroa, A.M.P.; De Oliveira, R.A. Sugar cane bagasse ash as a partial substitute of Portland cement: Effect on mechanical properties and emission of carbon dioxide. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.W.; Cai, R.J.; He, Z.; Cai, X.H.; Shao, H.Y.; Li, Z.J.; Yang, H.M.; Chen, E. Continuous microstructural correlation of slag/superplasticizer cement pastes by heat and impedance methods via fractal analysis. Fractals 2017, 25, 1740003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M.; Zhang, S.M.; Wang, L.; Chen, P.; Shao, D.K.; Tang, S.W.; Li, J.Z. High-ferrite Portland cement with slag: Hydration, microstructure, and resistance to sulfate attack at elevated temperature. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2022, 130, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, E.P.; Comodi, P.; Cambi, C.; Fastelli, M.; Corradini, A.; Montanari, C.; Zucchini, A.; Cerni, G.; Farhat, H.B.; Bocci, C.; et al. Wood biomass ash, municipal solid waste ash, and recycled concrete from construction demolition waste as supplementary cementitious materials in fine graded granular mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 498, 144016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.S.; Quang, L.V.; Van-Pham, D.; Huynh, T. Strength development and microstructural characterization of eco-cement paste with high-volume fly ash. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shu, X.; Zheng, S.; Qi, S.; Ran, Q. Effects of polyurethane–silica nanohybrids as additives on the mechanical performance enhancement of ordinary Portland cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 338, 127666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, L.; Xue, D.; Dong, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. Strength development of dredged sediment stabilized with nano-modified sulphoaluminate cement. Soils Found. 2025, 65, 101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.L.; Tan, T.H.; Ghayeb, H.H.; Koting, S.; Mo, K.H. Role of sulphate-based additives on the early age properties of Portland cement incorporating alumina-rich ladle furnace slag. Case Stud. Constr. Mat. 2025, 22, e04336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Han, B.; Dai, S.; Wang, H. The effect of glass fiber on mechanical behavior and microstructure of cement-based solidified soil for protecting foundations of offshore wind turbines. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, T.; Tian, L.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y. Effect of the presence or absence of curing agent on the properties of resin–Portland cement composite for oil and gas wells. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 255, 214120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, D.; Xie, H.; Yao, J.; Shen, X.; Wang, H.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, P. How does aluminum sulfate-based alkali-free accelerator affect calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) formation in accelerated cement pastes? Cem. Concr. Res. 2026, 199, 108052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, J.; Camarillo, R.; Martín, A. Solubility of aluminum sulfate in near-critical and supercritical water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2012, 57, 2084–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Garba, M.J.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, J.; Yuan, Q. Optimization of alkali-free accelerators via chelating acid design: Dual enhancement of early setting and strength development in cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, P.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Hong, J. The role of ettringite seeds in enhancing the ultra-early age strength of Portland cement containing aluminum sulfate accelerator. Compos. B Eng. 2024, 287, 111856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; He, S.; Liu, B.; Fu, Y.; Sun, W.; Luo, Y.; Tang, H. Efficient activation of humic acid in lignite via Fenton oxidation−nitric acid leaching for sustainable resource utilization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Huo, L.; Yi, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Yao, Z. A sustainable approach to enhancing humic acid production from lignocellulose via green alum. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gai, S.; Cheng, K.; Liu, Z.; Antonietti, M.; Yang, F. Artificial humic acid mediated Fe(II) regeneration to restart Fe(III)/PMS for the degradation of atrazine. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuzun, S.; Uzal, B. Performance of leonardite humic acid as a novel superplasticizer in Portland cement systems. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 103070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, S.; Bernhard, G. Influence of humic acids on the actinide migration in the environment: Suitable humic acid model substances and their application in studies with uranium-A review. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011, 290, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Tu, S.; Song, Y.; Shi, T.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H. A comprehensive benefit evaluation of recycled carbon fiber reinforced cement mortar based on combined weighting. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Jin, Z.; Hao, X.; Sun, P.; Han, Y.; Pan, C.; Fu, N.; Wang, H. Fracture toughness of recycled carbon fibers reinforced cement mortar and its environmental impact assessment. Case Stud. Constr. Mat. 2025, 22, e04866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Pei, C.; Xing, F. Advanced industrial-grade carbon-fiber-reinforced geopolymer cement supercapacitors for building-integrated energy storage solutions. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2025, 161, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, N.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Köberle, T.; Mechtcherine, V. Synergistic reinforcement of recycled carbon fibers and biochar in high-performance, low-carbon cement composites: A sustainable pathway for construction materials. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2025, 162, 106148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. Effect of polycarboxylate ether (PCE) superplasticizer on thixotropic structural build-up of fresh cement pastes over time. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 291, 123241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betioli, A.M.; Filho, J.H.; Cincotto, M.A.; Gleize, P.J.P.; Pileggi, R.G. Chemical interaction between EVA and Portland cement hydration at early-age. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 3332–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Lei, L.; Kang, Y.; Shi, C. Effect of 2-acrylamide-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid on the early strength enhancement of calcium silicate hydrate seed. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2024, 149, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ding, Y.; Sun, W.; Qian, W.; Liu, W.; Yang, Q. Utilization of plasma-induced graft polymerization to modify anion-exchanging membranes for enhanced selective separation of organic/inorganic salts. Polymer 2025, 335, 128805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). China National Standardization Administration Committee: Beijing, China, 2021.

- JC 477-2005; Flash Setting Admixtures for Shotcrete. China National Standardization Administration Committee: Beijing, China, 2005.

- Liu, X.; Köpke, J.; Akay, C.; Kümmel, S.; Imfeld, G. Sulfamethoxazole transformation by heat-activated persulfate: Linking transformation products patterns with carbon and nitrogen isotope fractionation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 5704–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, J.; Ray, S.K. Synthesis, characterization and column adsorption properties of gum ghatti and water hyacianth derived cellulose grafted poly(vinyl sulfonic acid-co-acrylamide) composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Keshar, K.; Mehta, R.K.; Yadav, M. Synthesis of novel carbon dots as efficient green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in an acidic environment: Electrochemical, gravimetric, and XPS analysis. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 209, 109561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntumalla, M.K.; Michaelson, S.; Hoffman, A. Nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen bonding and thermal stability of ambient exposed nitrogen-terminated H-diamond (111) surfaces studied by XPS and HREELS. Surf. Sci. 2024, 749, 122555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asifa, J.; Bhat, F.H.; Anjum, G.; Faisal, S.; Meena, R. Irradiation induced oxygen vacancy and strain effects in LaMn1-xCoxO3 thin films: Insights from XAS, XPS, and Raman spectroscopy. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 716, 417709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Wu, C.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, G. Green synthesis of nitrogen and oxygen enriched porous carbon from lignite humate for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, B.; Narwal, P.; Khandelwal, A.; Pal, S. Aqueous photo-degradation of Flupyradifurone (FPD) in presence of a natural Humic Acid (HA): A quantitative solution state NMR analysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 405, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devipriya, C.P.; Deepa, S.; Udayaseelan, J.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Aravinthraj, M.; Sabari, V. Quantum chemical and MD investigations on molecular structure, vibrational (FT-IR and FT-Raman), electronic, thermal, topological, molecular docking analysis of 1-carboxy-4-ethoxybenzene. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 8, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, F.; Shi, H.; Yan, J.; Shen, H.; Yu, S.; Gan, N.; Feng, B.; Wang, L. Protein FT-IR amide bands are beneficial to bacterial typing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.C.; Jablonsky, M.J.; Mays, J.W. NMR and FT-IR studies of sulfonated styrene-based homopolymers and copolymers. Polymer 2002, 43, 5125–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubar, N. XPS determined mechanism of selenite (HSeO3-) sorption in absence/presence of sulfate (SO42−) on Mg-Al-CO3 Layered double hydroxides (LDHs): Solid phase speciation focus. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, D.; Li, M.; Xie, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Hong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, P. Unraveling the role of magnesium salts in liquid alkali-free accelerators: Insights into setting and early-age properties of accelerated cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 195, 107920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunino, F.; Bentz, D.P.; Castro, J. Reducing setting time of blended cement paste containing high-SO3 fly ash (HSFA) using chemical/physical accelerators and by fly ash pre-washing. Cem. Concr. Comp. 2018, 90, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pel, L.; Sun, Z. NMR investigations on Cl− and Na+ ion binding during the early hydration process of C3S, C3A and cement paste: A combined modelling and experimental study. Compos. B Eng. 2024, 283, 111624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 34231-2017; Coal. Determination of Loss on Ignition for Coal Combustion Residues. National Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Li, X.; Wanner, A.; Hesse, C.; Friesen, S.; Dengler, J. Clinker-free cement based on calcined clay, slag, portlandite, anhydrite, and C-S-H seeding: An SCM-based low-carbon cementitious binder approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergold, S.T.; Goetz-Neunhoeffer, F.; Neubauer, J. Quantitative analysis of C–S–H in hydrating alite pastes by in-situ XRD. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 53, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatsunskyi, I.; Gottardi, G.; Micheli, V.; Canteri, R.; Coy, E.; Bechelany, M. Atomic layer deposition of palladium coated TiO2/Si nanopillars: ToF-SIMS, AES and XPS characterization study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 542, 148603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Shi, Z.; Medepalli, S.; Zhou, J.; He, F.; Ishida, T.; Hou, D.; Zhang, G.; et al. Effects of Al in C–A–S–H gel on the chloride binding capacity of blended cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 190, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Paste (J-Admixture- CF Mesh) | Setting Time (ST, Min, Paste) a | Mortar (S-Admixture-CF Mesh) | Compressive Strength (MPa, Mortar) b at: 6 h (24 h) | Flexural Strength (MPa, Mortar) b at: 6 h (24 h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (IST) | FST (FST) | |||||

| 1 | J-non | 34.78 ± 0.33 | 46.23 ± 0.37 | S-non | 0.8 ± 0.03 (3.4 ± 0.19) | 0.4 ± 0.05 (1.0 ± 0.17) |

| 2 | J-AS | 30.89 ± 0.79 | 36.08 ± 0.08 | S-AS | 0.8 ± 0.08 | 0.7 ± 0.10 |

| 3 | J-P2 | 2.62 ± 0.25 | 4.53 ± 0.07 | S-P2 | 1.7 ± 0.16 (4.2 ± 0.17) | 1.4 ± 0.05 (2.2 ± 0.17) |

| 4 | J-P2-50 | 2.21 ± 0.17 | 3.93 ± 0.13 | S-P2-50 | 1.5 ± 0.10 (5.5 ± 0.17) | 1.0 ± 0.05 (2.7 ± 0.20) |

| 5 | J-P2-200 | 2.91 ± 0.02 | 3.93 ± 0.02 | S-P2-200 | 1.3 ± 0.11 | 1.0 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Z.; Chaudhary, S.; Ding, Y.; Yan, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, Y. Enhancing Cement Hydration and Mechanical Strength via Co-Polymerization of Sodium Humate with Superplasticizer Monomers and Sequential Blending with Aluminum Sulfate and Carbon Fibers. Buildings 2025, 15, 4422. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244422

Song Z, Chaudhary S, Ding Y, Yan Y, Jia Q, Wu Y, Li X, Sun Y. Enhancing Cement Hydration and Mechanical Strength via Co-Polymerization of Sodium Humate with Superplasticizer Monomers and Sequential Blending with Aluminum Sulfate and Carbon Fibers. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4422. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244422

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Zhiyuan, Sidra Chaudhary, Yan Ding, Yujiao Yan, Qinxiang Jia, Yong Wu, Xiaoyong Li, and Yang Sun. 2025. "Enhancing Cement Hydration and Mechanical Strength via Co-Polymerization of Sodium Humate with Superplasticizer Monomers and Sequential Blending with Aluminum Sulfate and Carbon Fibers" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4422. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244422

APA StyleSong, Z., Chaudhary, S., Ding, Y., Yan, Y., Jia, Q., Wu, Y., Li, X., & Sun, Y. (2025). Enhancing Cement Hydration and Mechanical Strength via Co-Polymerization of Sodium Humate with Superplasticizer Monomers and Sequential Blending with Aluminum Sulfate and Carbon Fibers. Buildings, 15(24), 4422. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244422