Assessing the Seismic Performance of Prefabricated Coupling Beams Using Double-Lap Sleeves: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Description

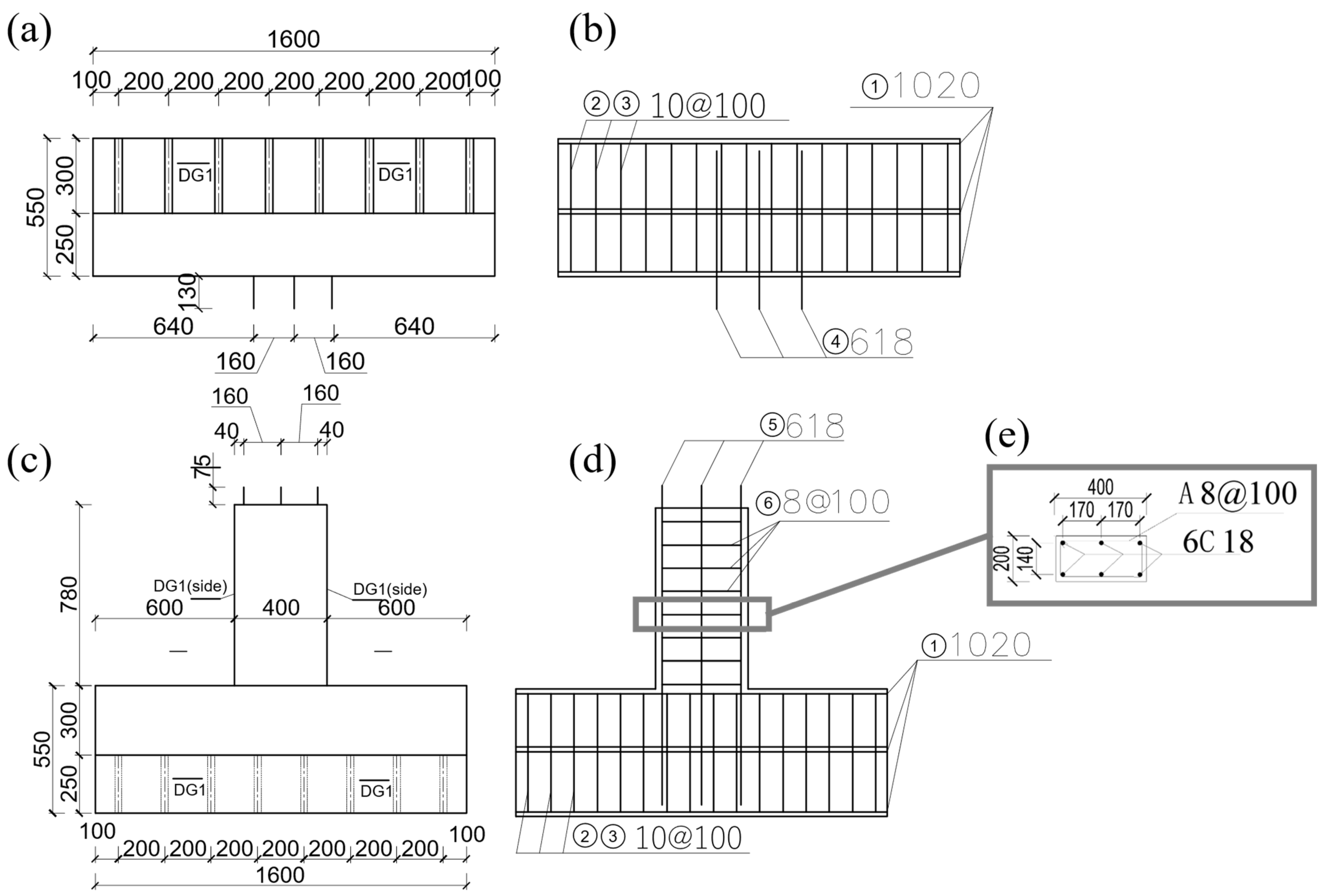

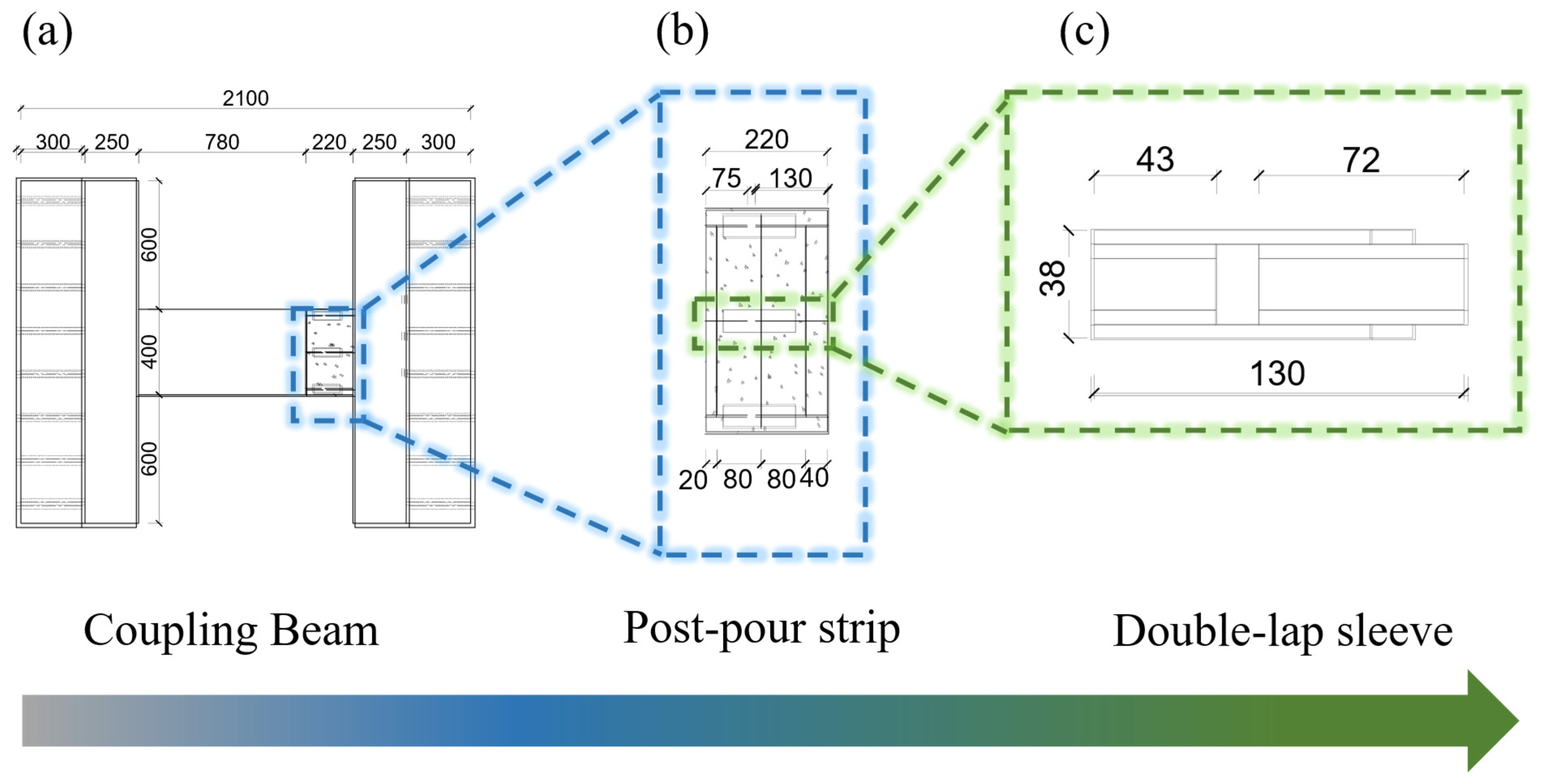

2.1. Specimen Design

2.2. Experimental Material

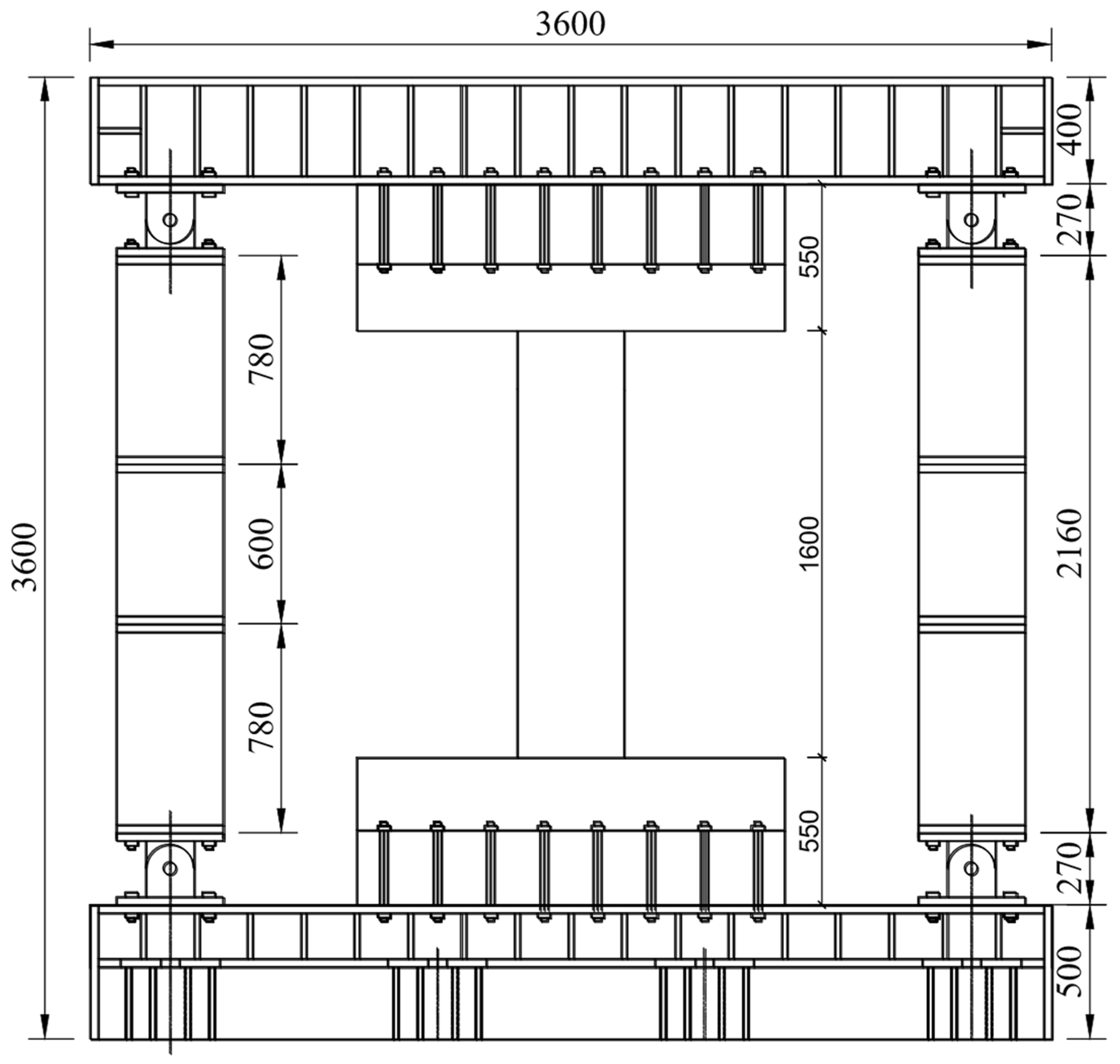

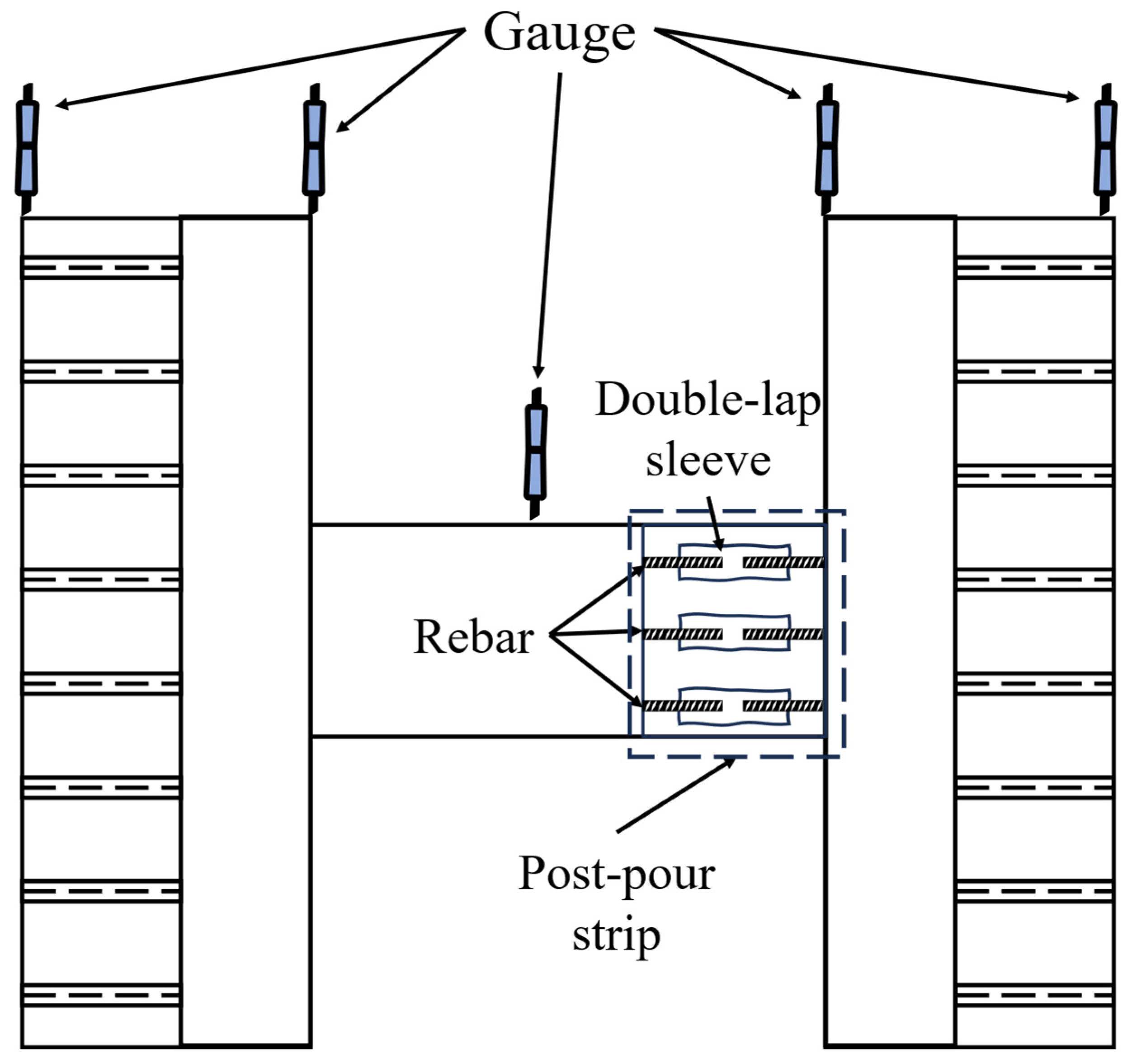

2.3. Loading System and Measurement Content

3. Development and Validation of Numerical Models Based on DIANA

3.1. Finite Element Model

3.2. Constitutive Model

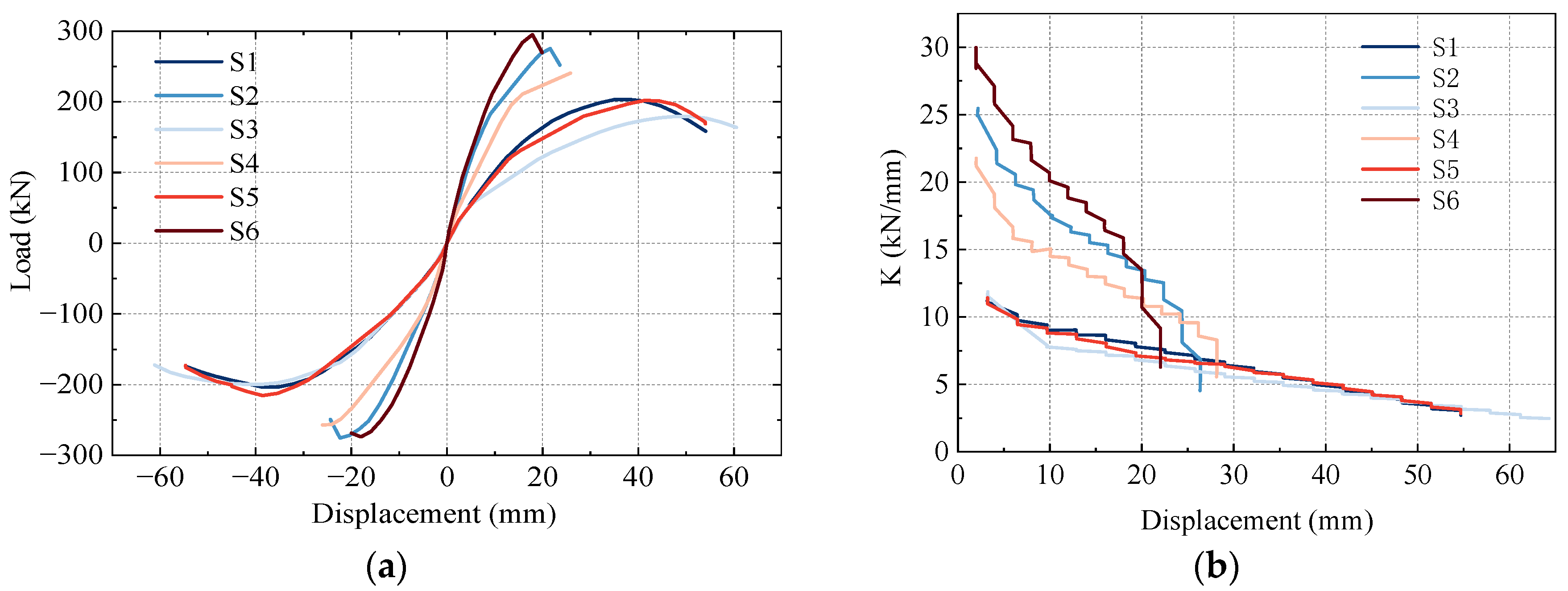

3.3. Validation of Numerical Model

3.3.1. Failure Pattern

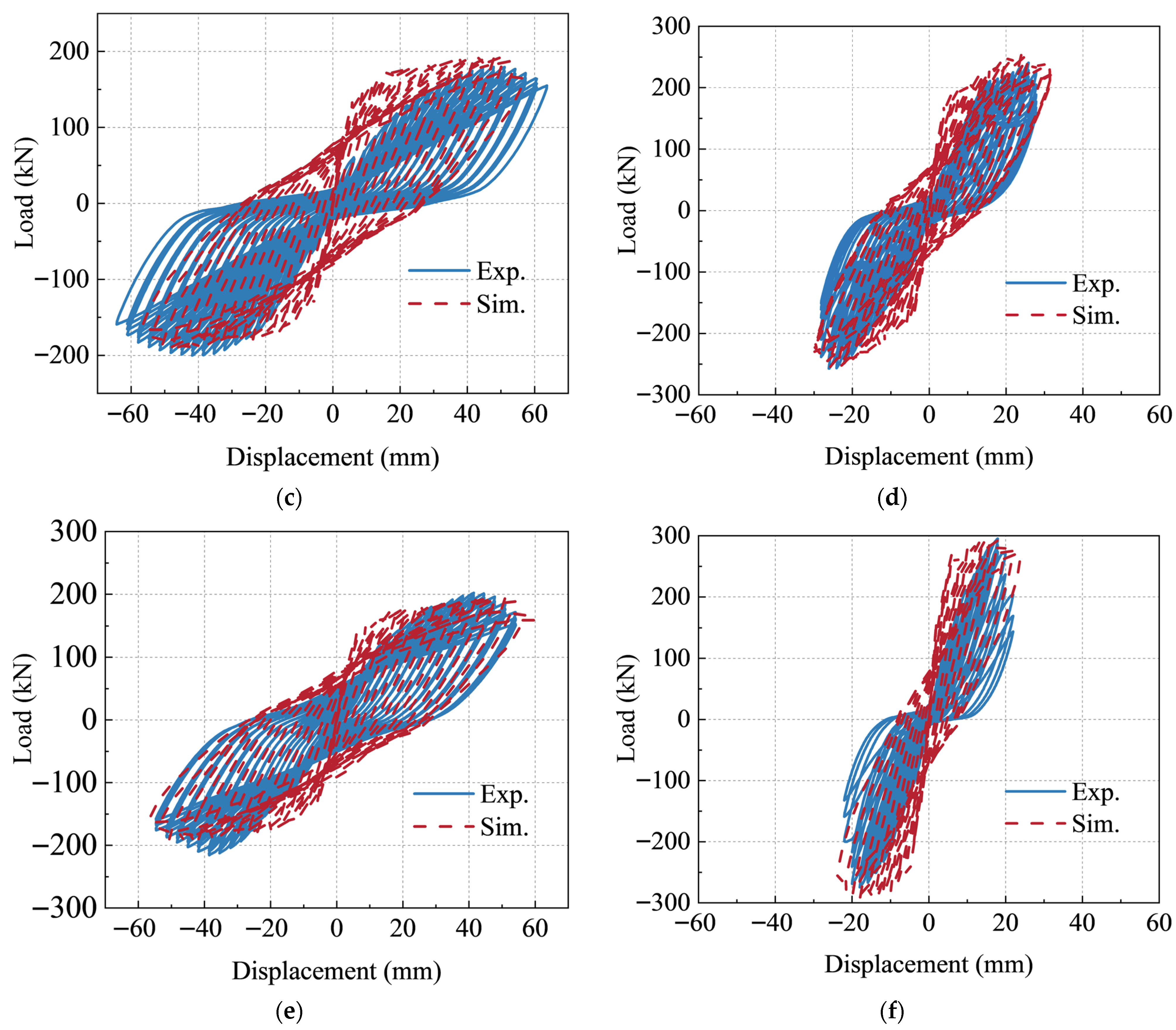

3.3.2. Hysteresis Curves and Skeleton Curves

4. Results and Discussion

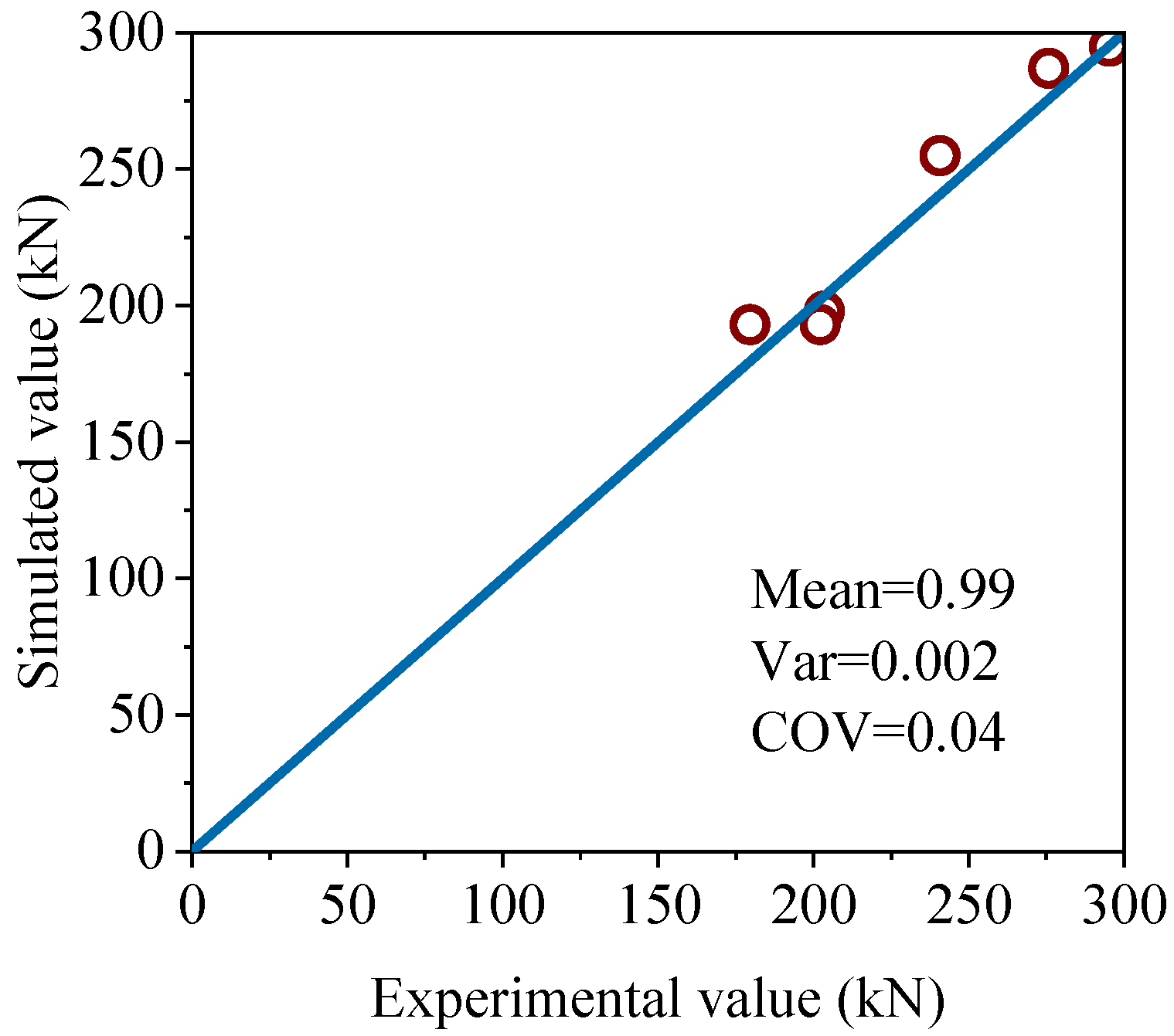

4.1. Energy Evolution of Specimens

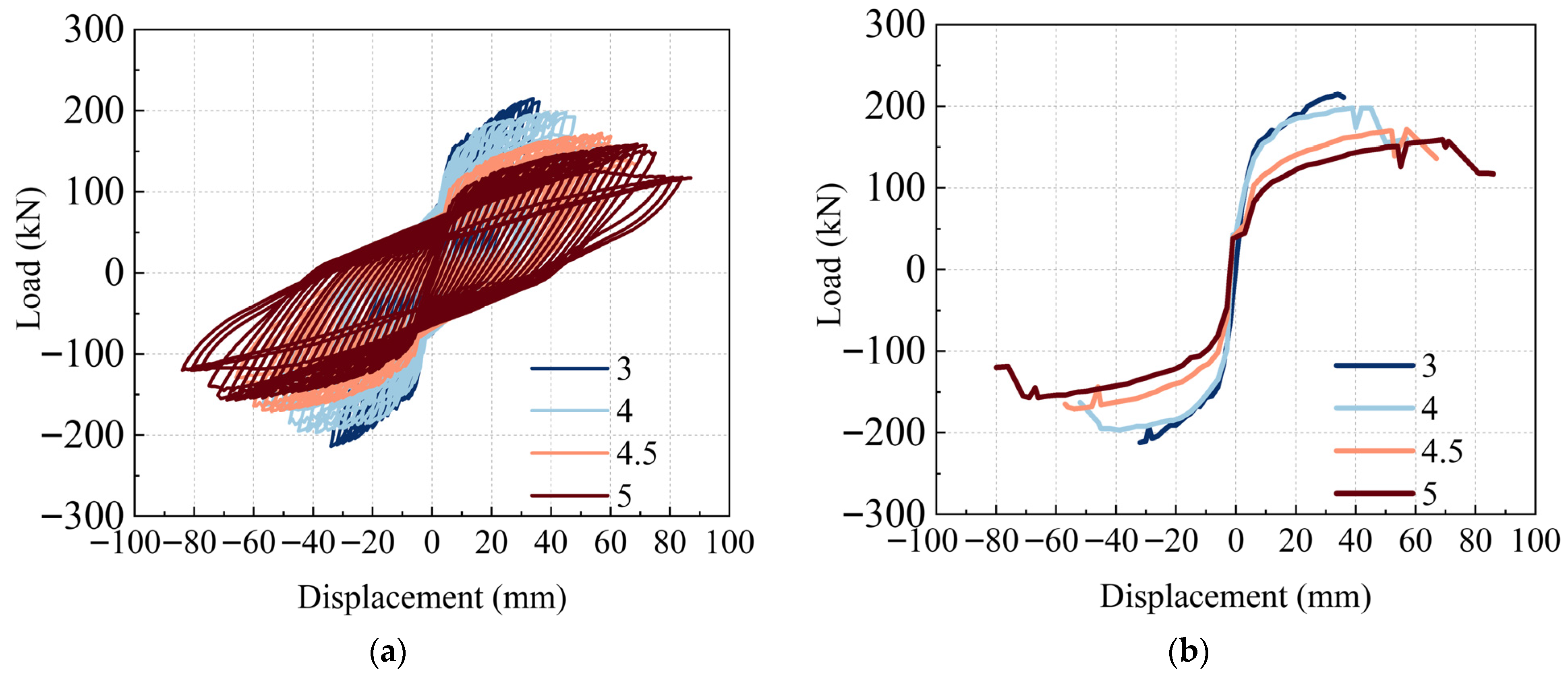

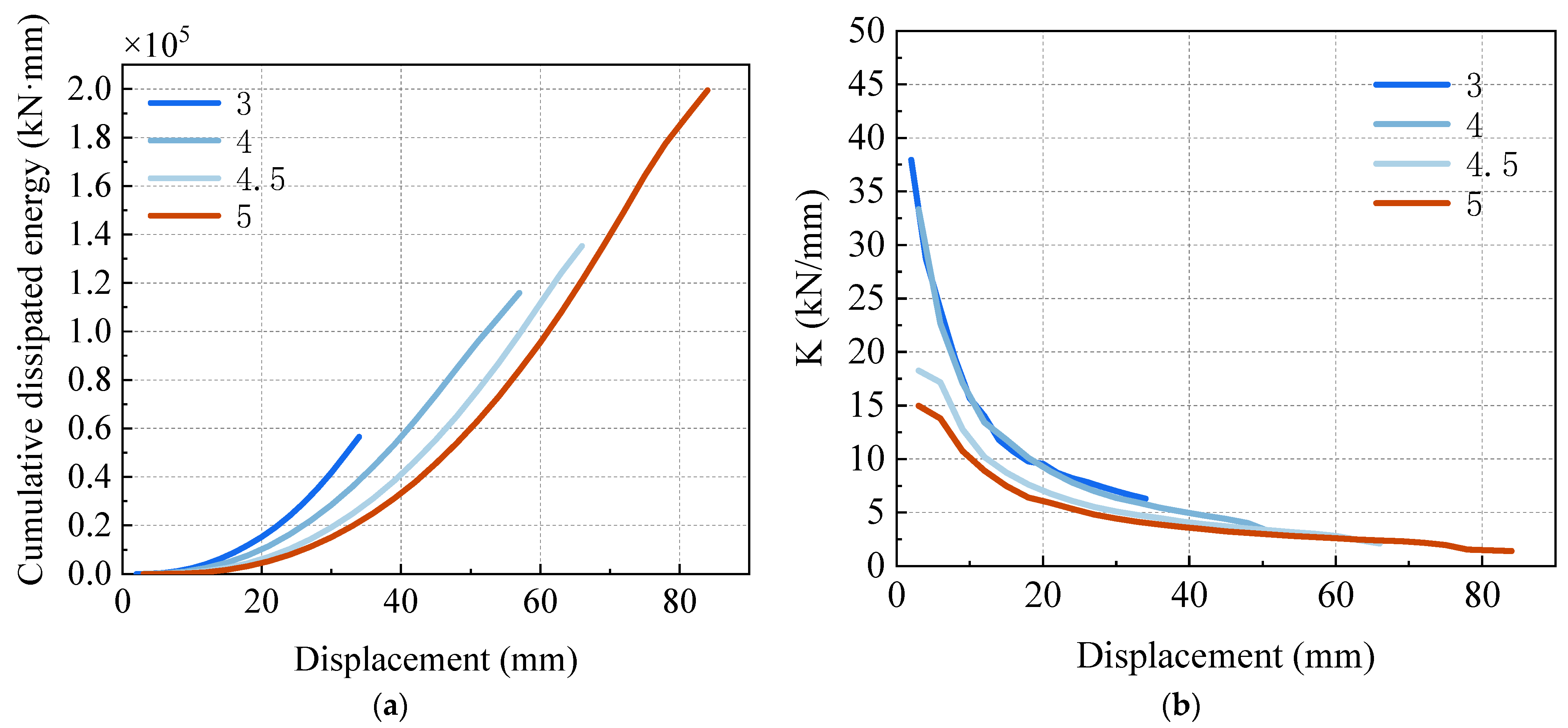

4.2. Shear Span Ratio

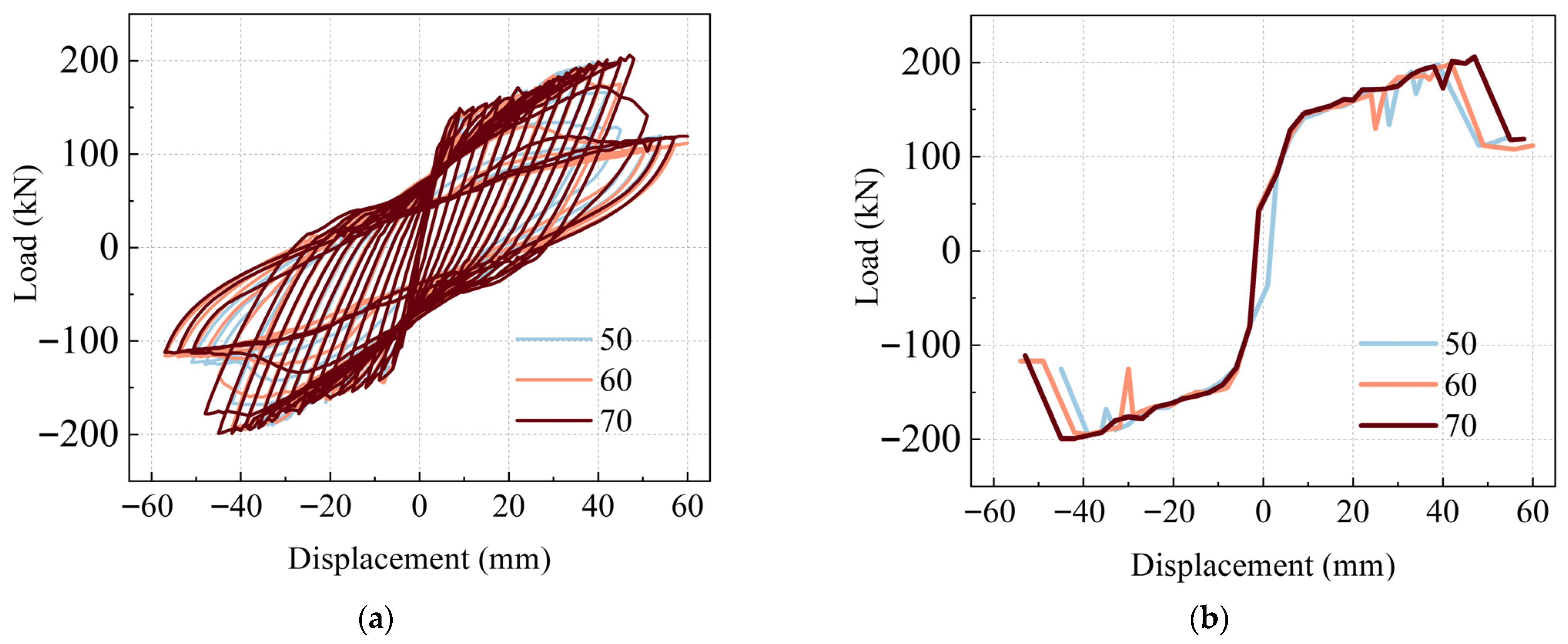

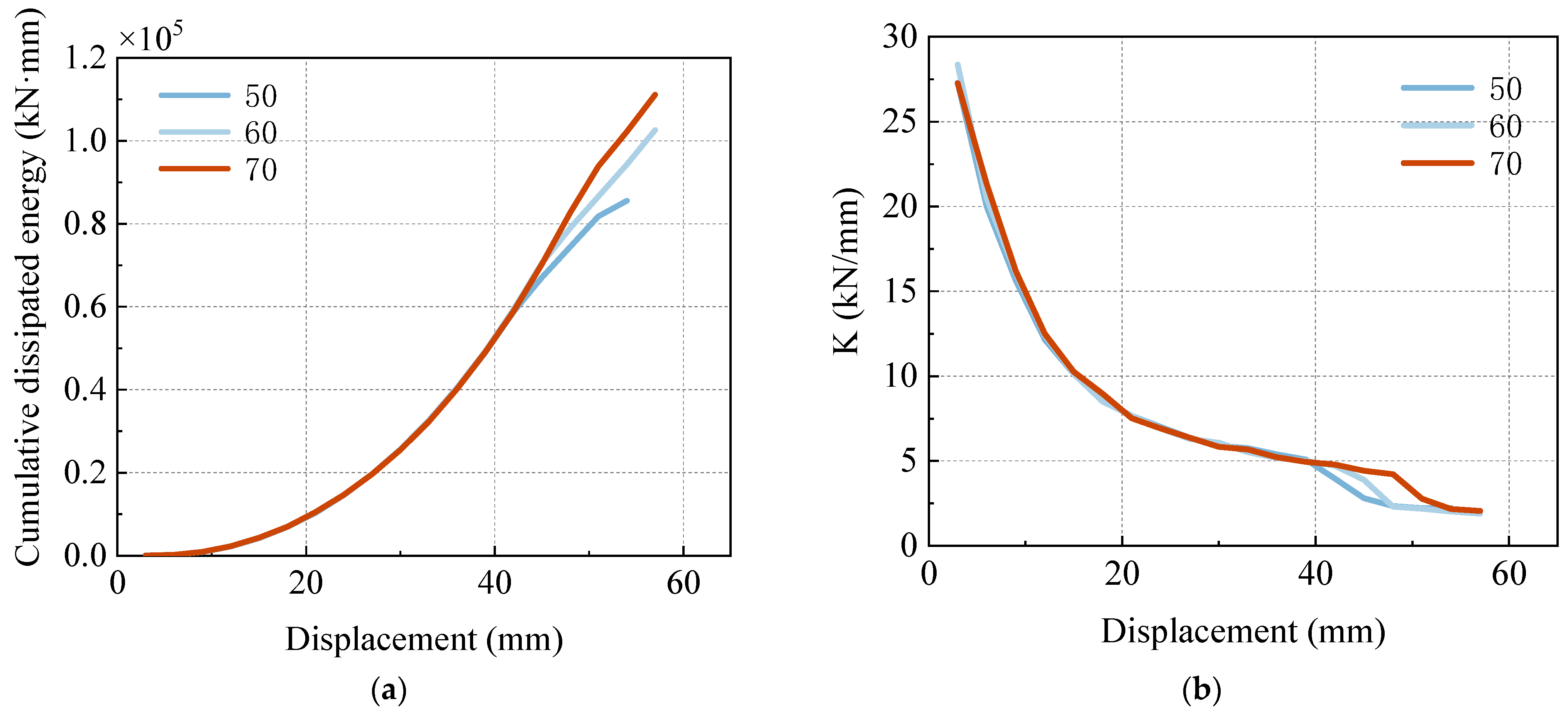

4.3. Compressive Strength

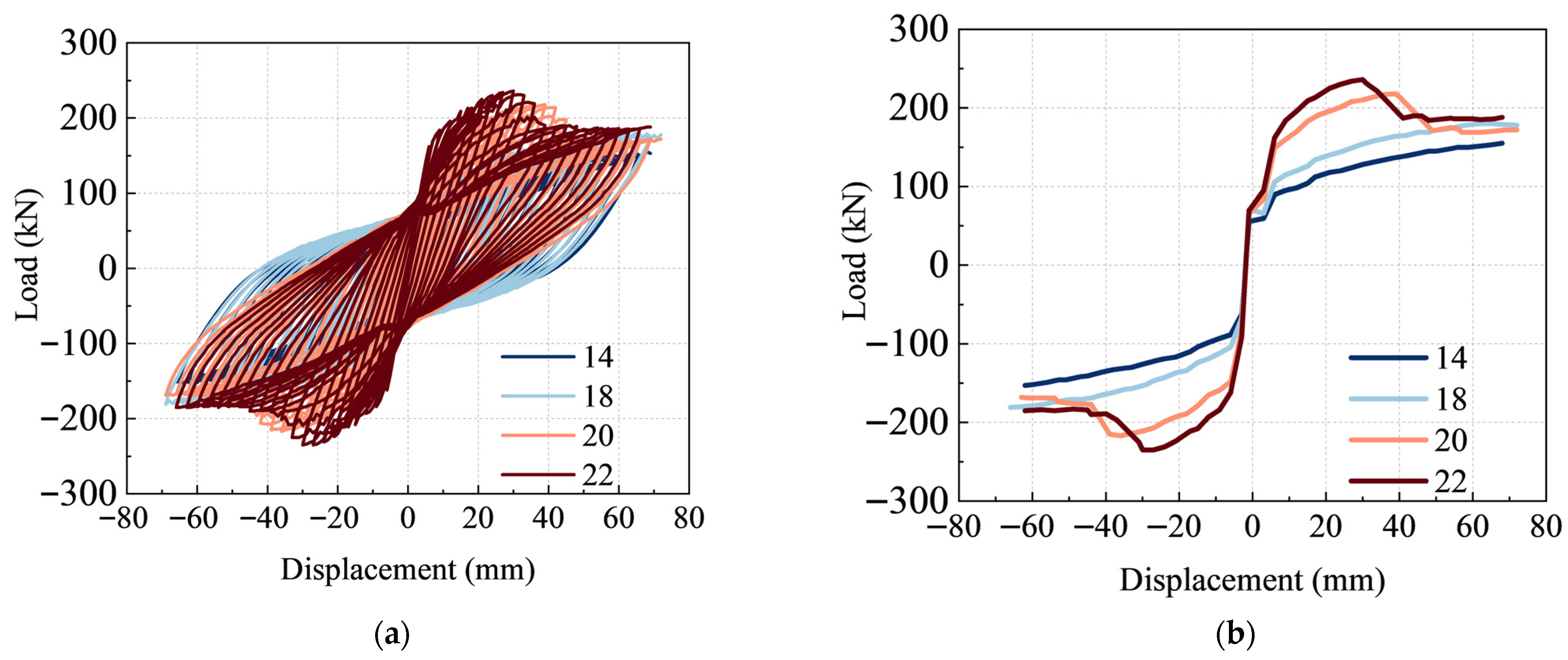

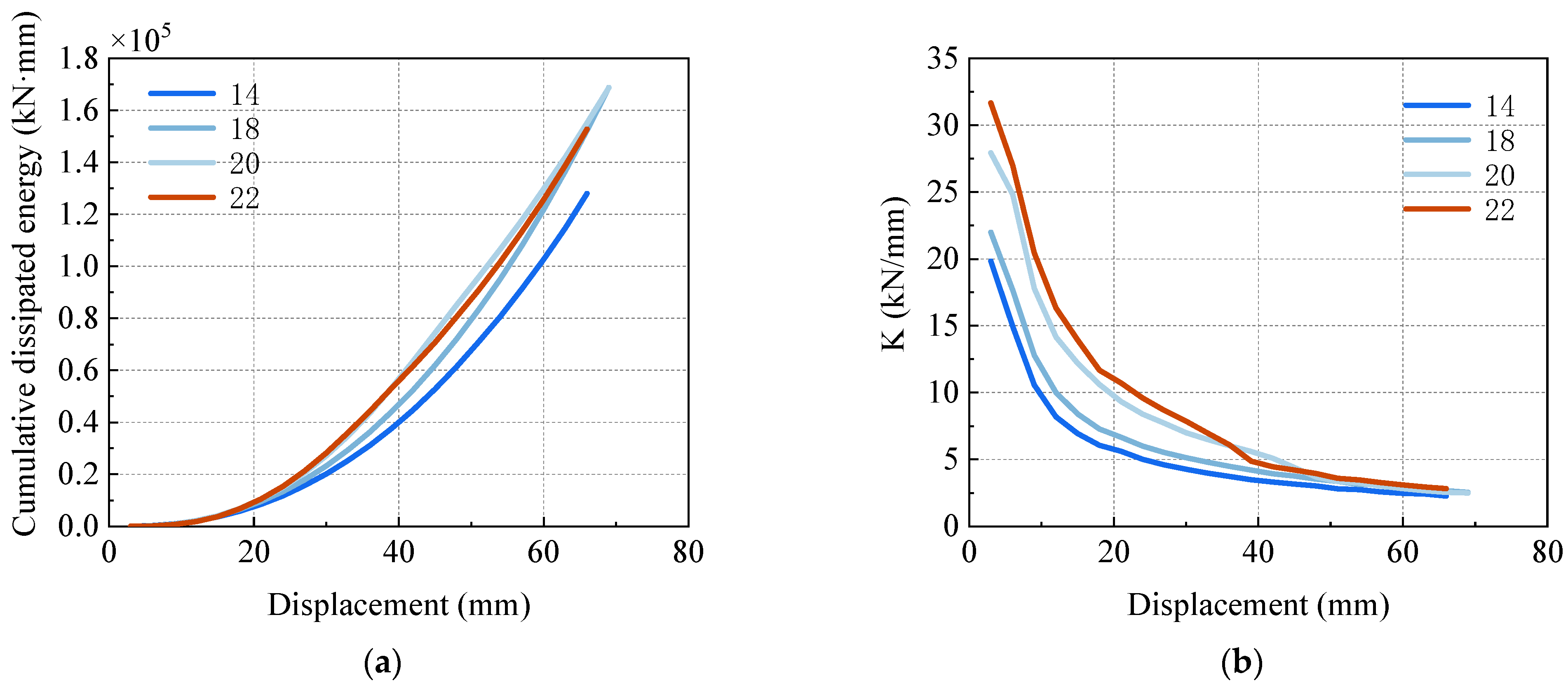

4.4. Reinforcement Ratio

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, X.; Hao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.; Hou, X.; Ou, T. Coupling Ratio and Parametric Analysis of Coupled Steel Plate Shear Wall Based on Orthogonal Test. Thin-Walled Struct. 2026, 218, 113917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-Q.; Pang, M.-D.; Li, Y.-W.; Li, L.-L.; Sun, F.-F.; Sun, J.-Y. Experimental Comparative Study of Coupled Shear Wall Systems with Steel and Reinforced Concrete Link Beams. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2019, 28, e1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Ma, K.; Yu, H. Seismic Behavior of Coupled Wall Structure with Steel and Viscous Damping Composite Coupling Beams. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Z. Experimental Study and Numerical Simulation on Hybrid Coupled Shear Wall with Replaceable Coupling Beams. Sustainability 2019, 11, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, N.; Shi, Z.; Li, P.; Lei, Y. Seismic Performance of RC Coupled Shear Wall Structure with Hysteretic-Viscous Replaceable Coupling Beams: Experimental and Numerical Investigations. Eng. Struct. 2025, 326, 119493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Fan, G.; Tao, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. Seismic Behavior of Prefabricated Steel Reinforced Concrete Shear Walls with New Type Connection Mode. Structures 2022, 37, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Bai, G.; Liu, B.; Wu, T.; Wang, B. Study on the Global Bidirectional Seismic Behavior of Monolithic Prefabricate Concrete Shear Wall Structure. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 136, 106194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, W.; Jia, H.; Chen, M.; Zheng, J. Research Progress on Seismic Behavior of Precast Reinforced Concrete Shear Wall Structures (Ⅰ): Study on Joint Performance. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2013, 33, 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C. Study on Seismic Performance of Connecting Prefabricated Coupling Beam and Shear Wall with Equivalent Bars. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 2784137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yuan, S.; Jiang, R.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Dou, L.; Zou, G. Behavior of Prefabricated Composite Arch Coupling Beam for Shear Walls Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Buildings 2022, 12, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Hu, X.; Xue, W. Experimental Study on Seismic Behavior of Bolted Connection between Composite Beam and Precast Shear Wall. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2021, 42, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Gu, J.-B.; Guo, J.-Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, J. Seismic Performance of Precast Concrete Shear Wall with Treatments of Connecting Reinforcement Defects in Grouted Sleeves under Combined Axial Tension and Cyclic Horizontal Load. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.; Wu, H.; Huo, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Thermo-Mechanical Behavior and Flexural Enhancement of in-Service Steel-Concrete Composite Beams Strengthened by Welded Channel Steel. J. Build. Eng. 2026, 117, 114720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Cao, K.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Experimental and Numerical Evaluation of Seismic Behavior in Fully Prefabricated Composite RCS Joints with Cover Plates and Bolted Connections. Structures 2025, 81, 110153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Feng, J.; Xue, Y.; Liang, C. Seismic Behavior of an Innovative Prefabricated Steel-Concrete Composite Beam-Column Joint. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50010—2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Mander, J.B.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Park, R. Theoretical Stress-Strain Model for Confined Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1988, 114, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite Euro-International Du Beton. CEB-FIP Model Code 1990: Design Code; Comite Euro-International Du Beton: Lausanne, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Sun, M.; Yao, G.; Guo, H.; Zhong, R. Research on Optimization Design of Prefabricated ECC/RC Composite Coupled Shear Walls Based on Seismic Energy Dissipation. Buildings 2024, 14, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, W. Numerical Investigation on Seismic Performance of a Hollow Precast Coupling Beam-Shear Wall Connection with Insulation. Structures 2025, 79, 109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Yan, G.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Lu, J.; Jiang, G. Seismic Behavior and Parametric Study of the Precast Shear Wall with Steel Energy-Dissipating Connection. Structures 2025, 82, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Xu, H.; Zeng, S.; Chen, T.; He, K. Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Precast High-Strength RC Beam-Column Joint with Embedded Channel Steel and UHPC. Structures 2025, 81, 110235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Qing, L. Research on the Application of Solid Waste-Derived Reactive Powder in Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) and Micro-Mechanisms. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 197, 107033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wallace, J.W.; Jiang, X.; Qian, J. Seismic Behaviour of Assembled Monolithic Concrete Coupling Beams through Tests of Two-Story Coupled Shear Walls. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen | Coupling Beam Dimensions (mm) | Longitudinal Reinforcement | Shear Reinforcement | Span-to-Depth Ratio | Sleeve Connection Detail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 1600 × 400 × 200 | Top & Bottom: 2C18 each Side: 1C18 each | C8@100 | 4 | Single-sided |

| S2 | 1000 × 400 × 200 | 2.5 | Single-sided | ||

| S3 | 1600 × 400 × 200 | 4 | Double-sided | ||

| S4 | 1000 × 400 × 200 | 2.5 | Double-sided | ||

| S5 | 1600 × 400 × 200 | 4 | Cast-in-place | ||

| S6 | 1000 × 400 × 200 | 2.5 | Cast-in-place |

| Concrete | fcu,m (MPa) | fcu,k (MPa) | fc,m (MPa) | fck (MPa) | fc (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 42.0 | 38.7 | 31.9 | 28.5 | 19.1 |

| Rebar Diameter (mm) | Es (MPa) | fy (MPa) | fu (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 2.02 × 105 | 451 | 656 |

| 14 | 2.02 × 105 | 474 | 622 |

| 18 | 2.02 × 105 | 448 | 628 |

| Specimen | Coupling Beam Length (mm) | Chord Rotation Increment | Displacement Increment per Step (mm) | Loading Cycles per Step | Maximum Chord Rotation | Maximum Displacement (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 1600 | 0.2% | 3.2 | 3 times | 3.4% | 54.4 |

| S2 | 1000 | 2.0 | 2.6% | 26.0 | ||

| S3 | 1600 | 3.2 | 3.8% | 60.8 | ||

| S4 | 1000 | 2.0 | 2.6% | 26.0 | ||

| S5 | 1600 | 3.2 | 3.4% | 20.4 | ||

| S6 | 1000 | 2.0 | 2.6% | 26.0 |

| Shear Span Ratio | Yield Load/kN | Yield Displacement/mm | Peak Load/kN | Peak Displacement/mm | Ultimate Displacement/mm | Ductility Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 172.79 | 14.42 | 215.00 | 34.00 | 36.00 | 2.50 |

| 4.0 | 164.11 | 12.58 | 198.00 | 39.00 | 48.45 | 3.85 |

| 4.5 | 143.18 | 21.89 | 172.00 | 57.00 | 64.17 | 2.93 |

| 5.0 | 130.19 | 27.19 | 159.00 | 69.00 | 76.60 | 2.82 |

| Compressive Strength/MPa | Yield Load/kN | Yield Displacement/mm | Peak Load/kN | Peak Displacement/mm | Ultimate Displacement/mm | Ductility Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 157.64 | 19.56 | 198.00 | 39.00 | 42.11 | 2.15 |

| 60 | 157.66 | 19.09 | 198.00 | 42.00 | 44.42 | 2.33 |

| 70 | 165.17 | 20.94 | 206.00 | 47.00 | 49.81 | 2.38 |

| Bar Diameter/mm | Yield Load/kN | Yield Displacement/mm | Peak Load/kN | Peak Displacement/mm | Ultimate Displacement/mm | Ductility Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 123.66 | 26.74 | 155.00 | 68.00 | 68.00 | 2.54 |

| 18 | 144.04 | 24.02 | 180.00 | 62.00 | 72.00 | 3.00 |

| 20 | 180.39 | 14.40 | 218.00 | 39.00 | 46.01 | 3.20 |

| 22 | 196.06 | 12.01 | 236.00 | 30.00 | 38.20 | 3.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, M.; Wu, H.; Su, L.; Hu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Cai, Q.; Yang, W. Assessing the Seismic Performance of Prefabricated Coupling Beams Using Double-Lap Sleeves: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Buildings 2025, 15, 4387. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234387

Jin M, Wu H, Su L, Hu X, Zeng Y, Cai Q, Yang W. Assessing the Seismic Performance of Prefabricated Coupling Beams Using Double-Lap Sleeves: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4387. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234387

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Mei, Hao Wu, Lei Su, Xiaoyi Hu, Yong Zeng, Qiang Cai, and Wenju Yang. 2025. "Assessing the Seismic Performance of Prefabricated Coupling Beams Using Double-Lap Sleeves: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4387. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234387

APA StyleJin, M., Wu, H., Su, L., Hu, X., Zeng, Y., Cai, Q., & Yang, W. (2025). Assessing the Seismic Performance of Prefabricated Coupling Beams Using Double-Lap Sleeves: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Buildings, 15(23), 4387. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234387