Dynamic Splitting Tensile Behavior of Hybrid Fibers-Reinforced Cementitious Composites: SHPB Tests and Mesoscale Industrial CT Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Experimental Design

2.1. Materials, Mix Proportions, and Specimen Preparation

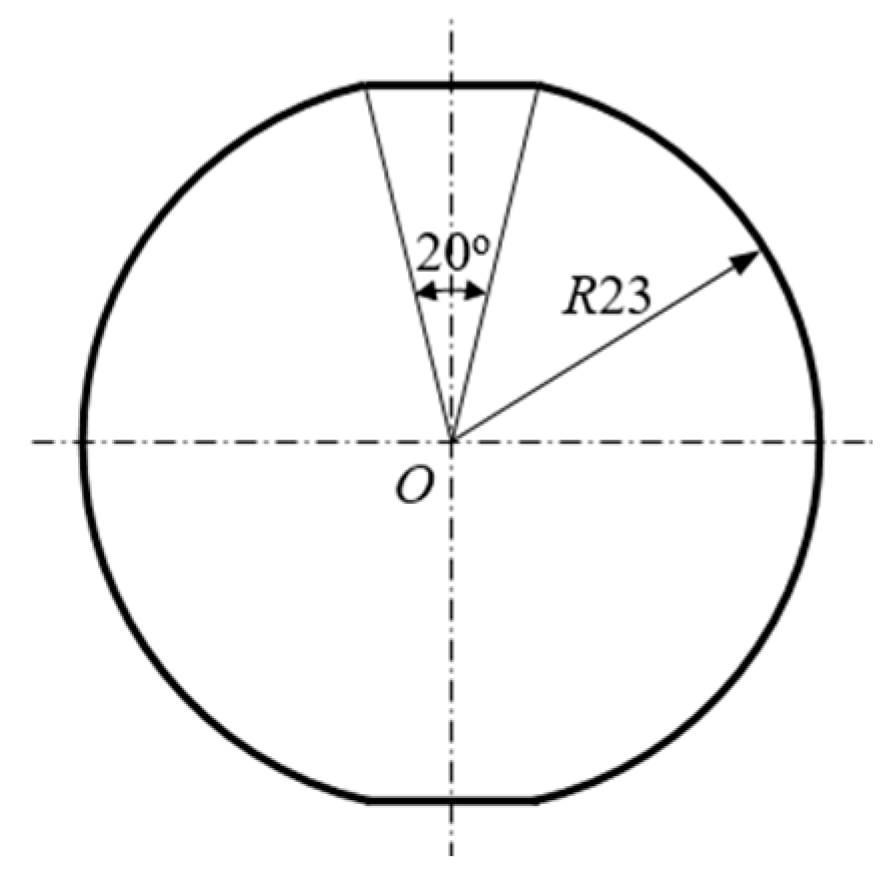

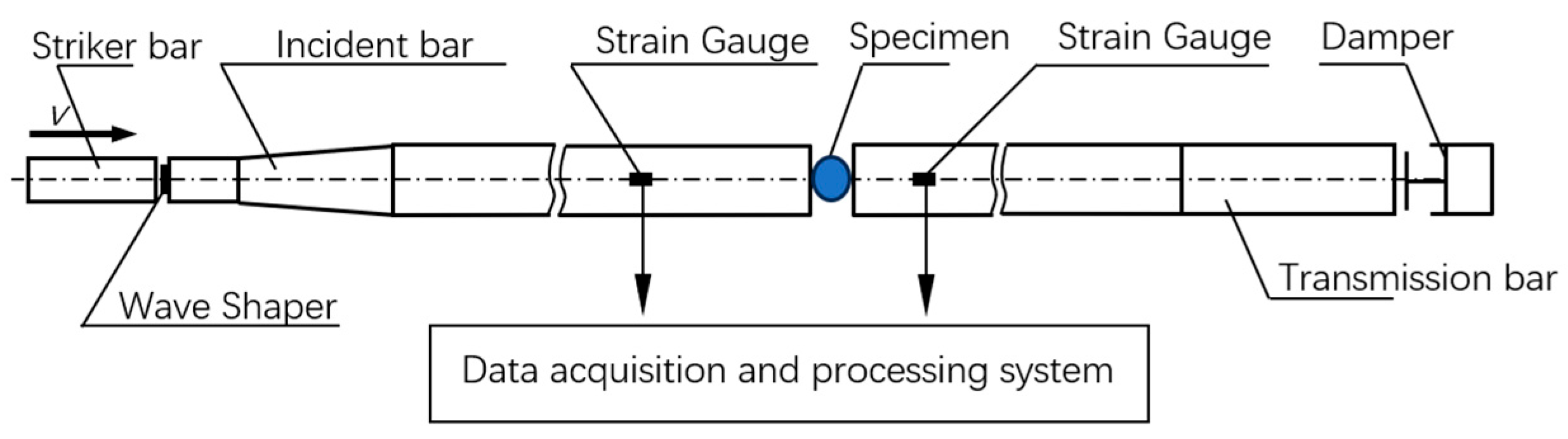

2.2. SHPB Splitting Tensile Test

2.3. Industrial CT Scanning

3. Results and Analysis

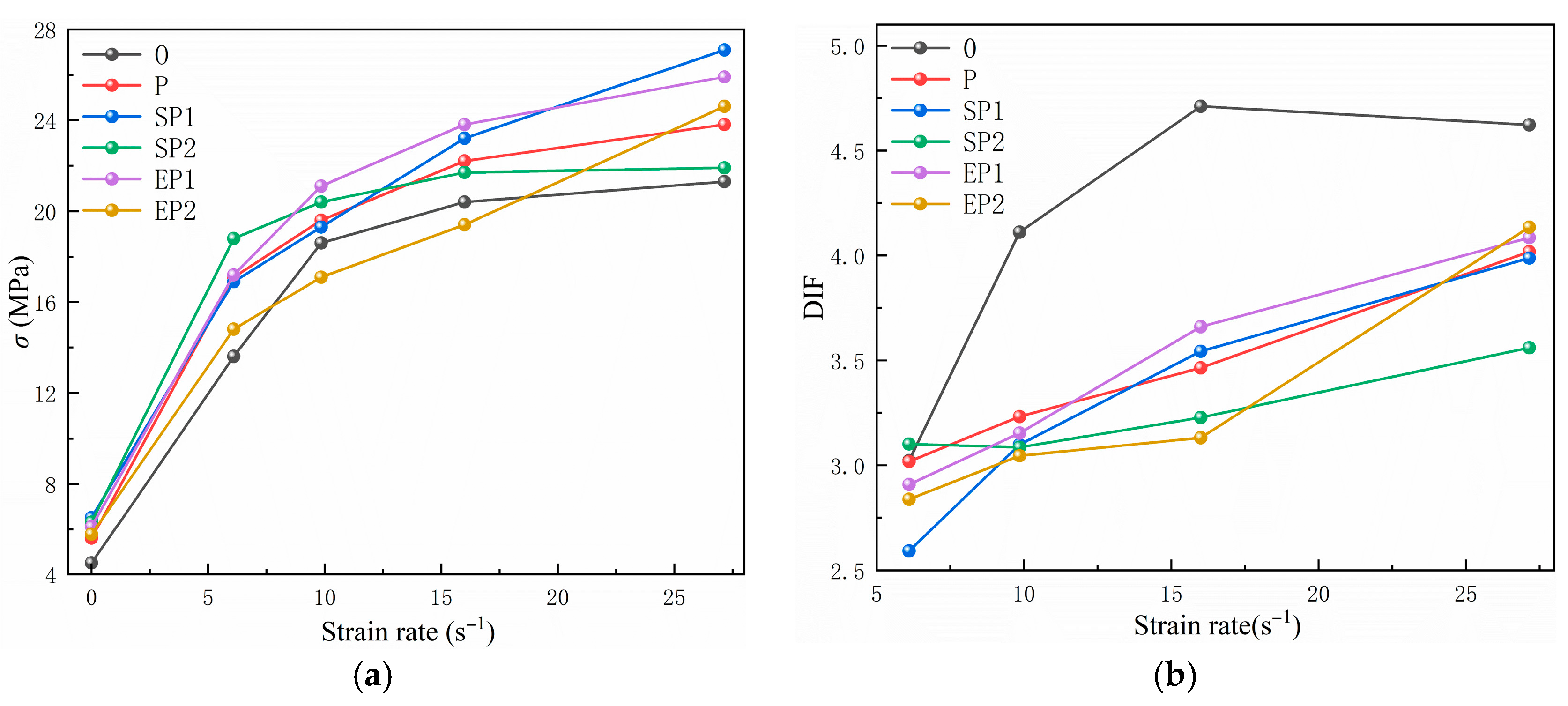

3.1. Results and Analysis of the SHPB Splitting Tensile Test

3.1.1. Dynamic Splitting Tensile Strength and Strain Rate Effects

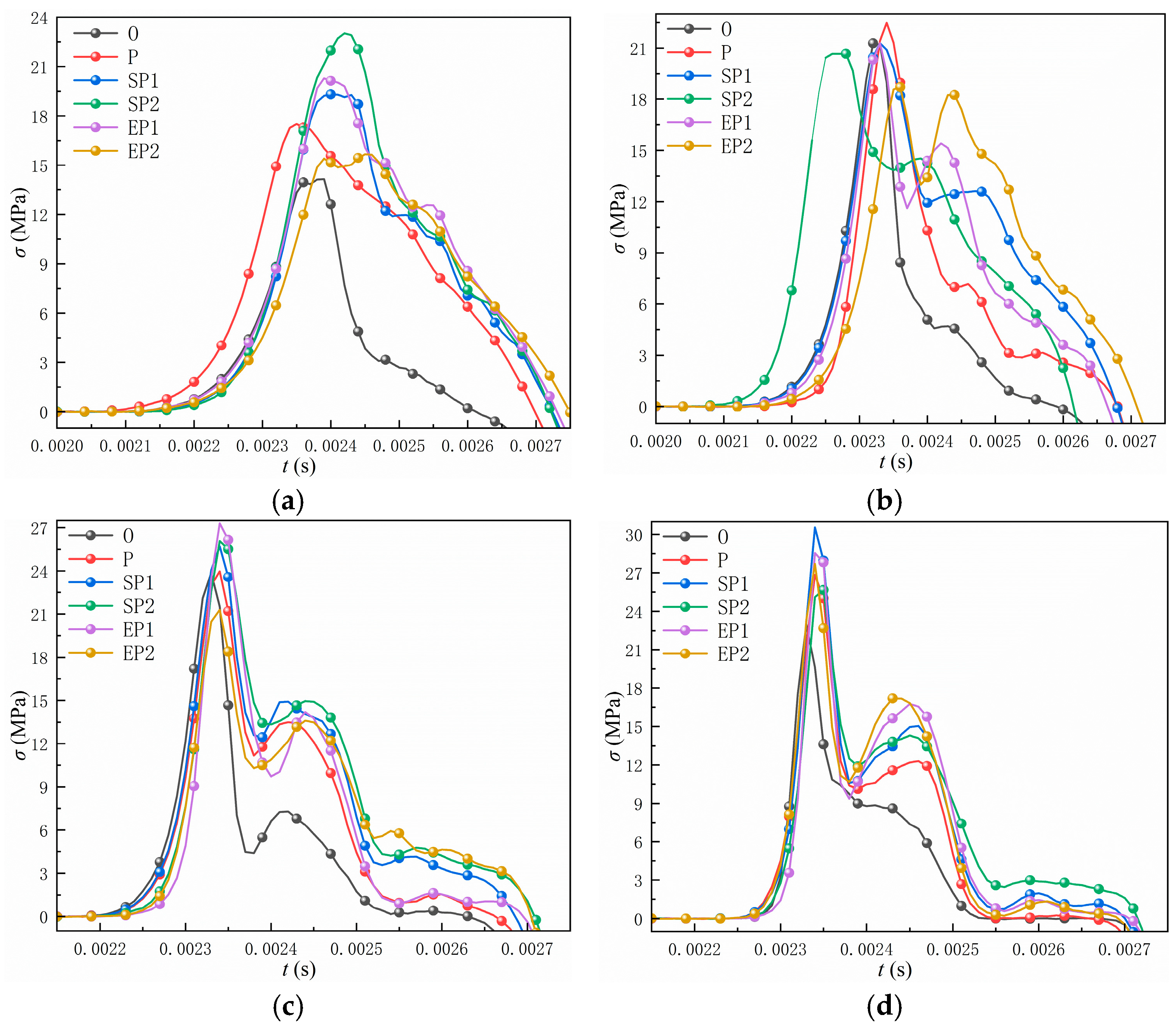

3.1.2. Stress-Time History Curves

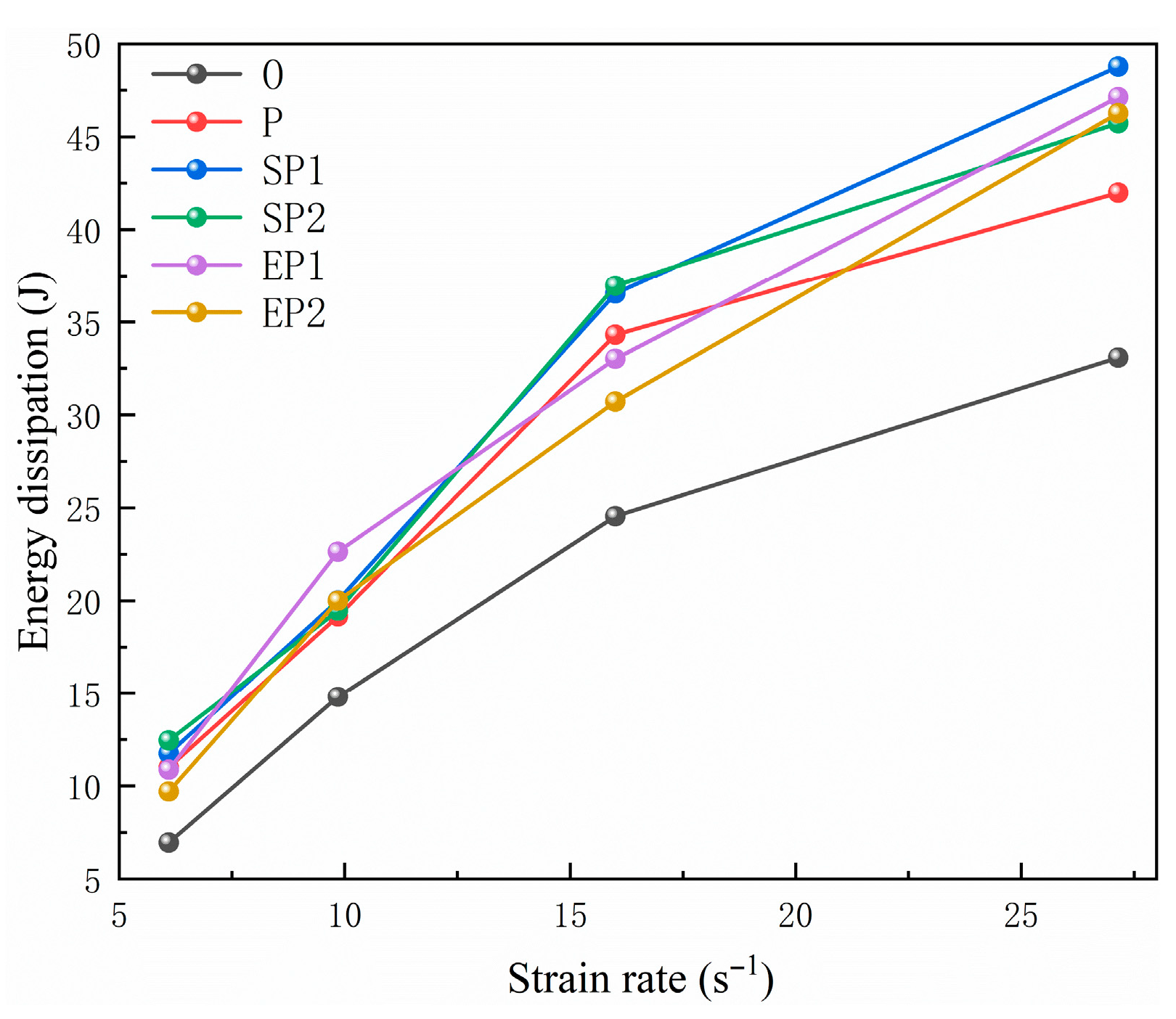

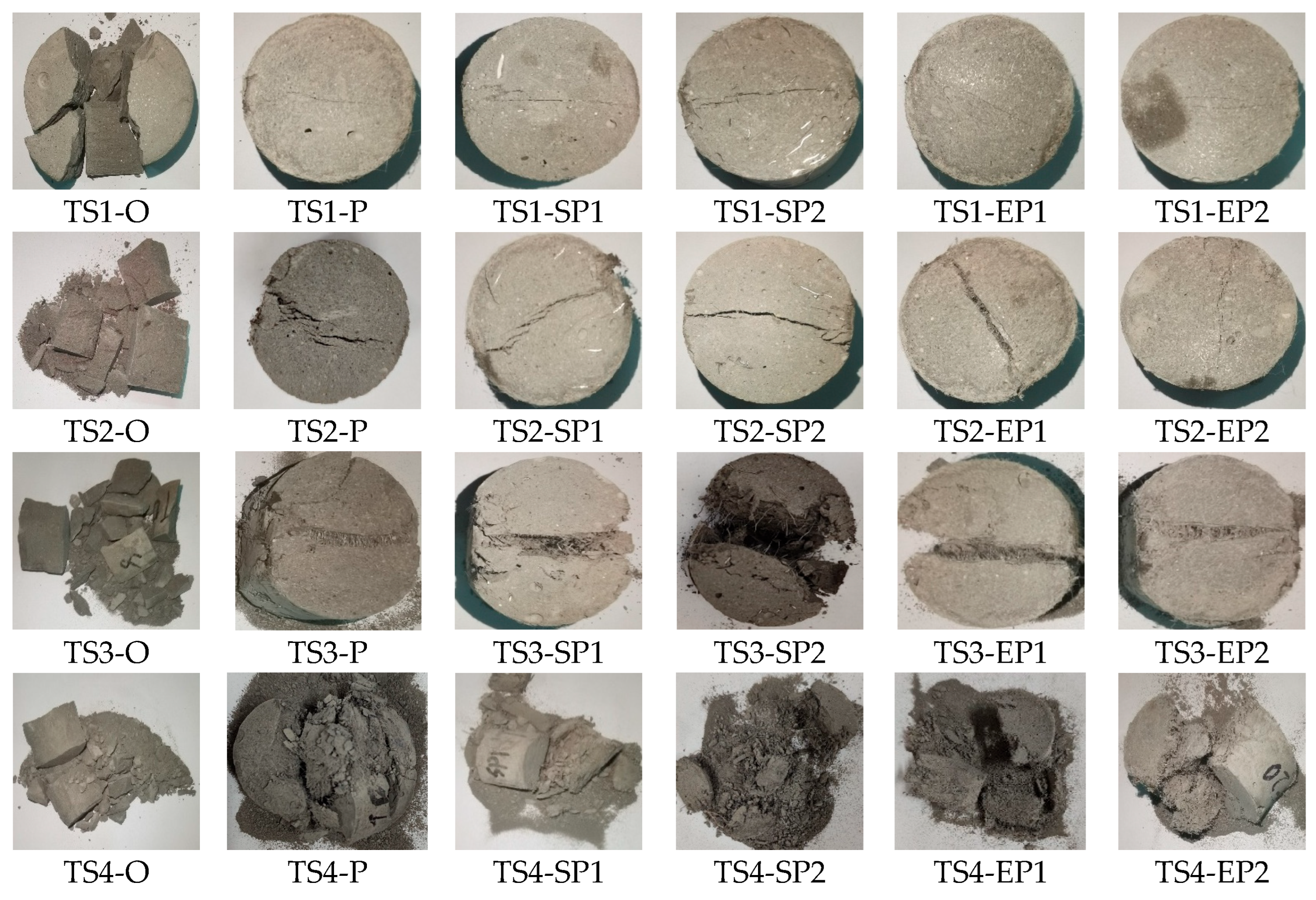

3.1.3. Failure Modes and Energy Dissipation

3.2. Results and Analysis of the Industrial CT Scanning

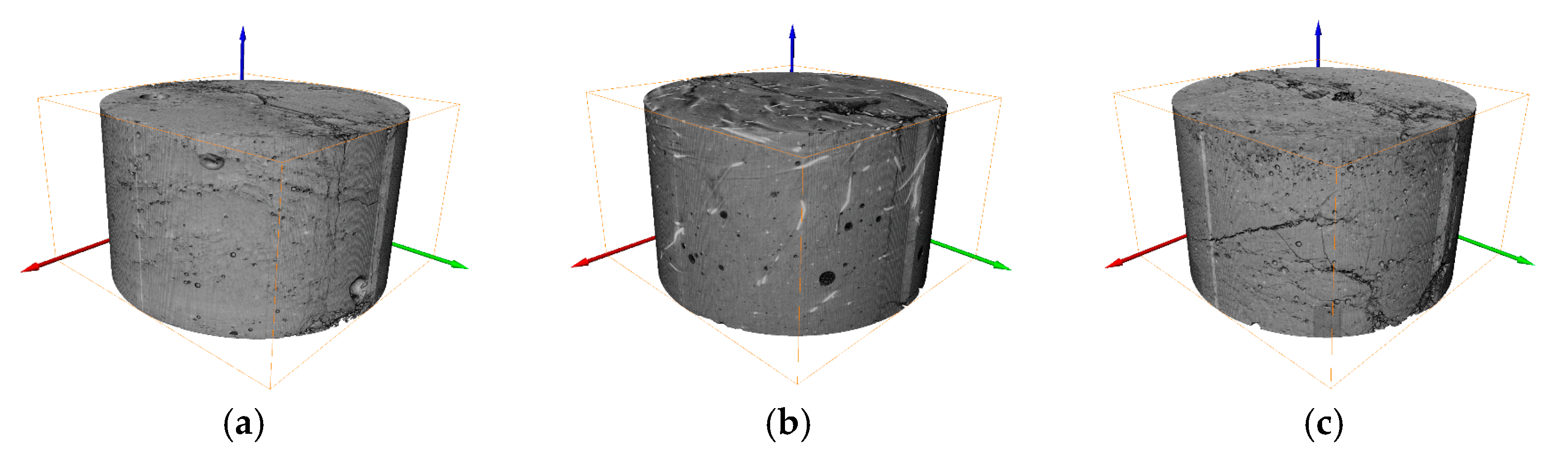

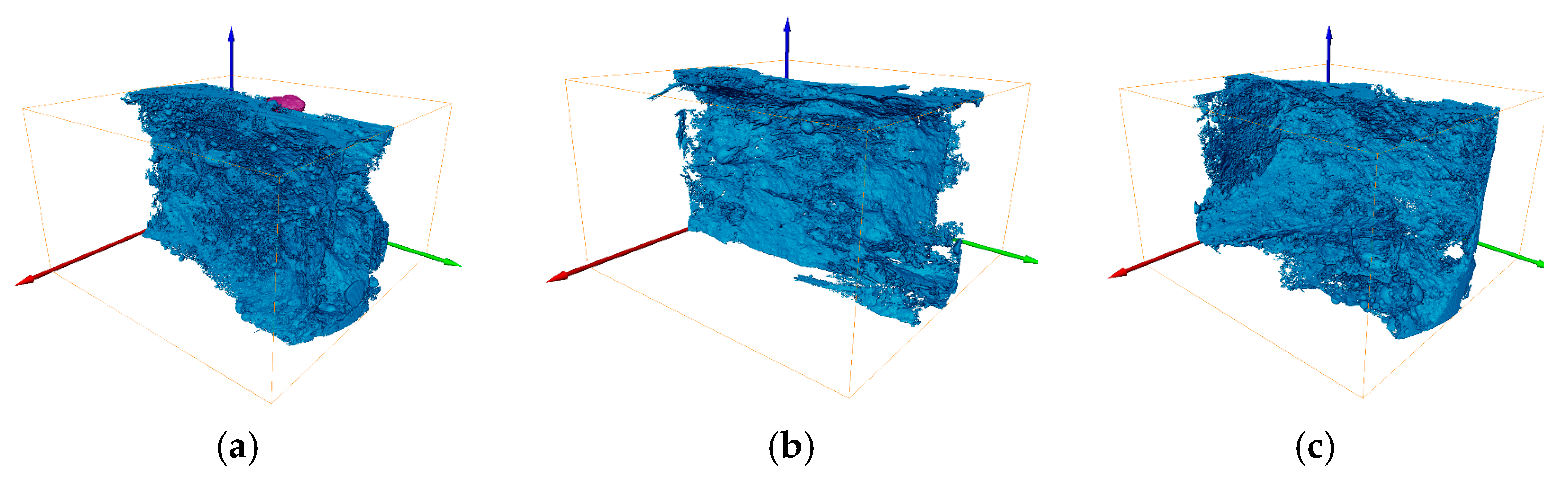

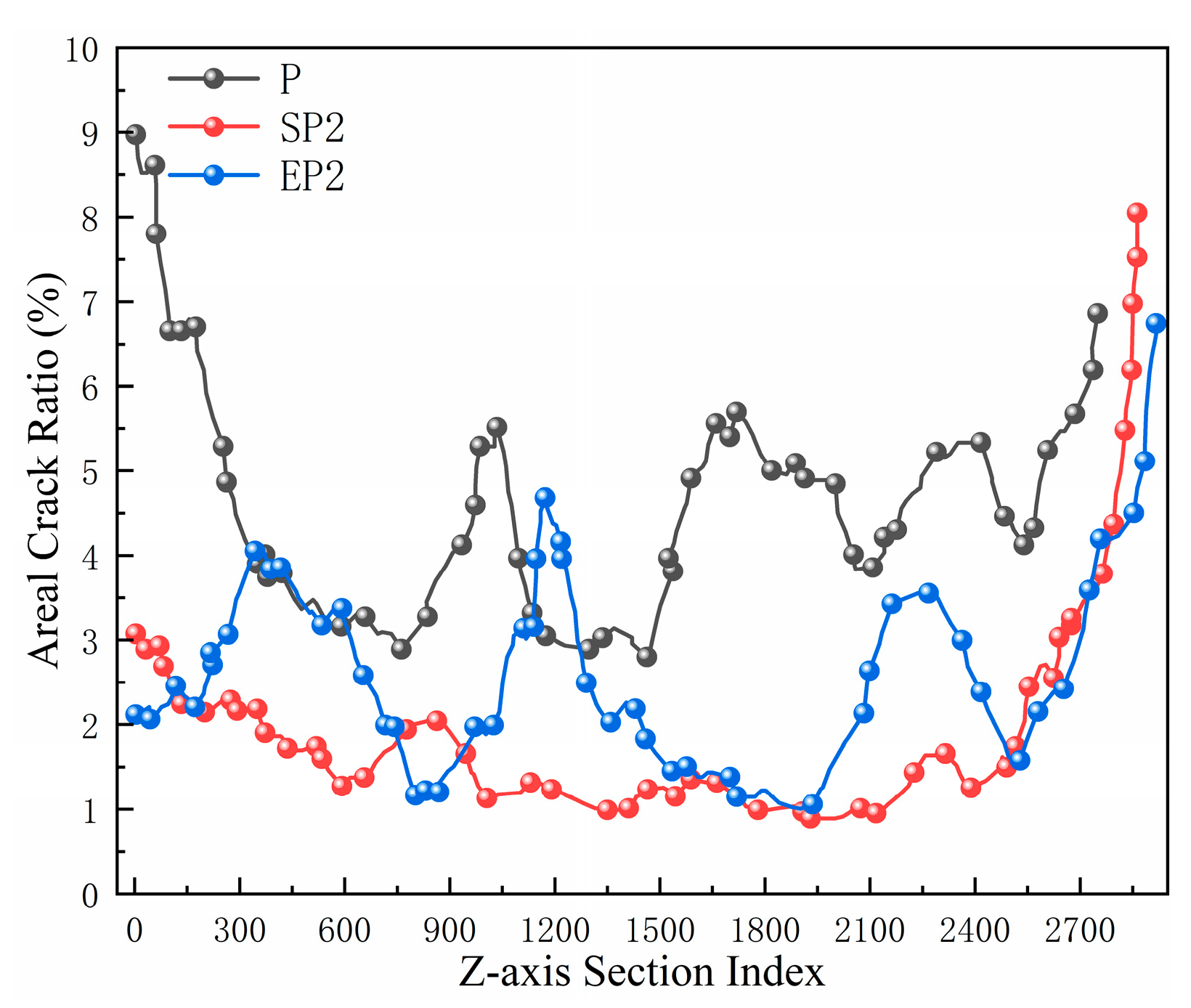

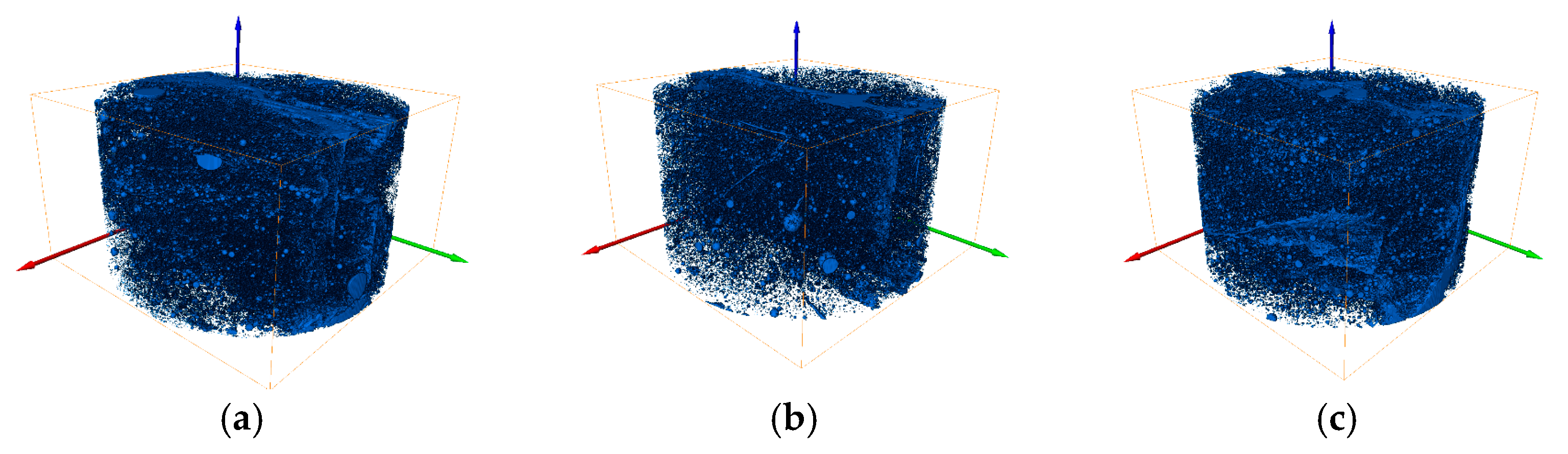

3.2.1. Internal Crack Characterization

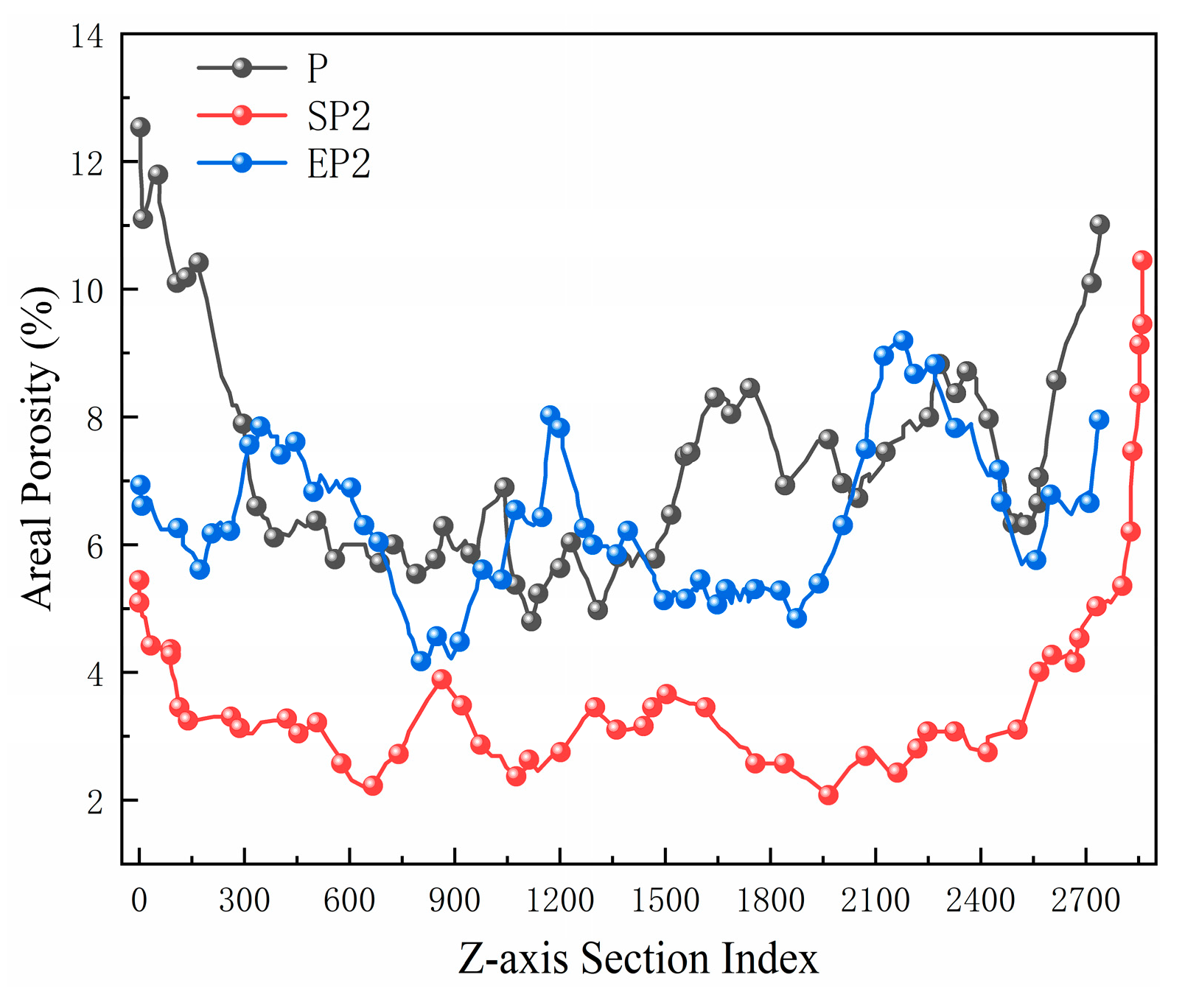

3.2.2. Internal Pore Characterization

3.2.3. Pore-Crack Evolution

4. Discussion

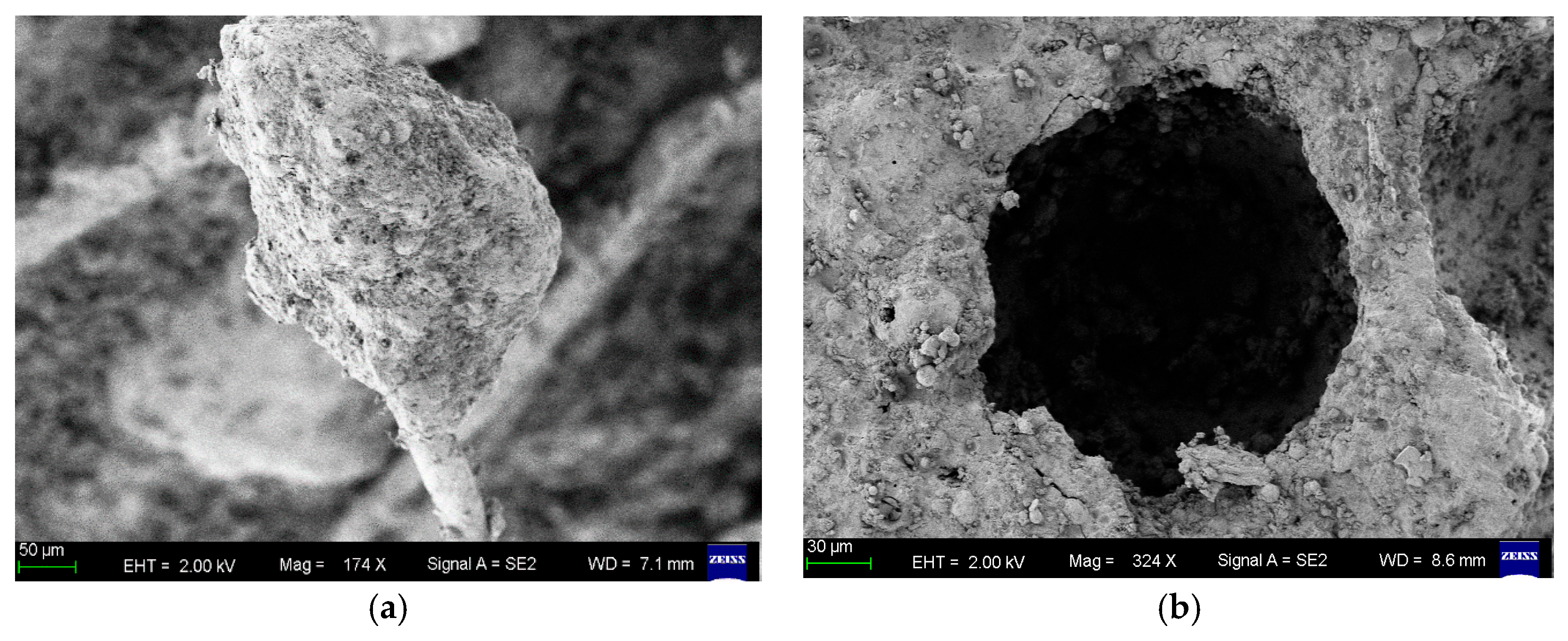

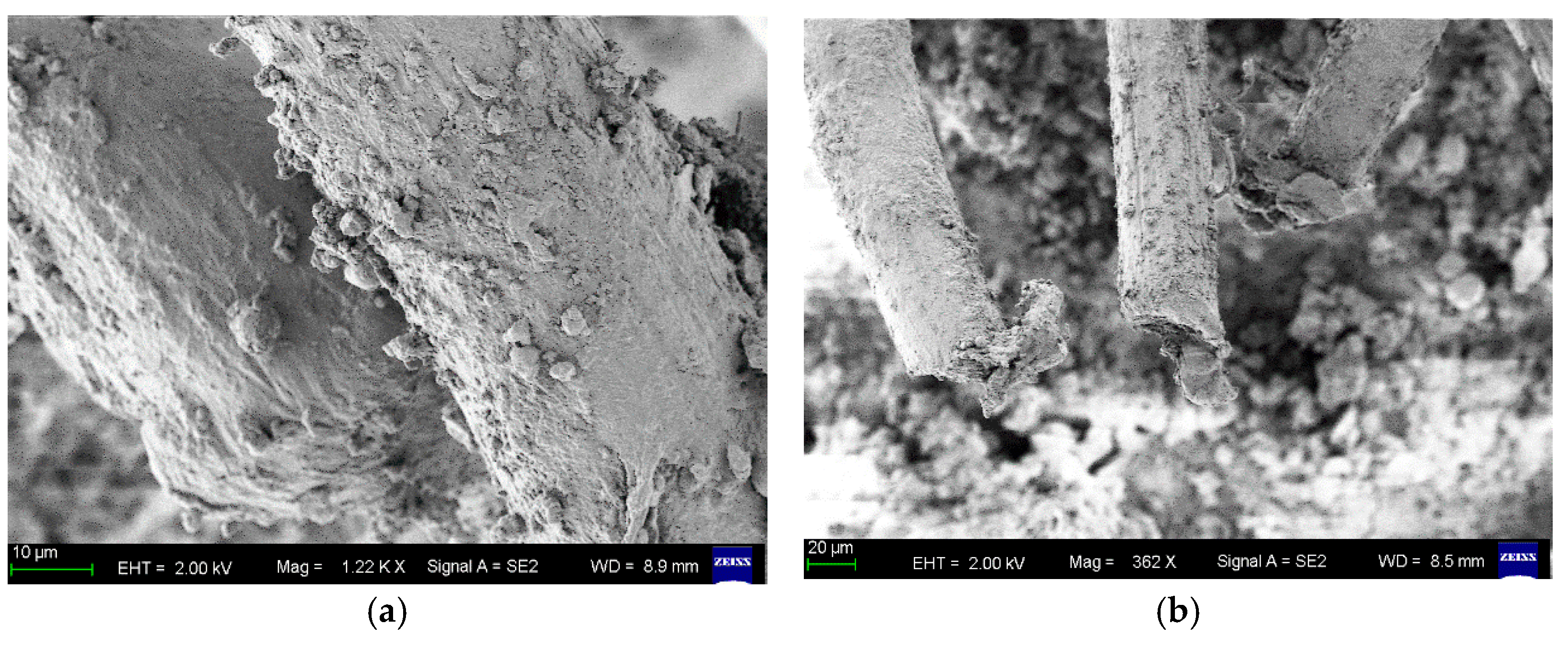

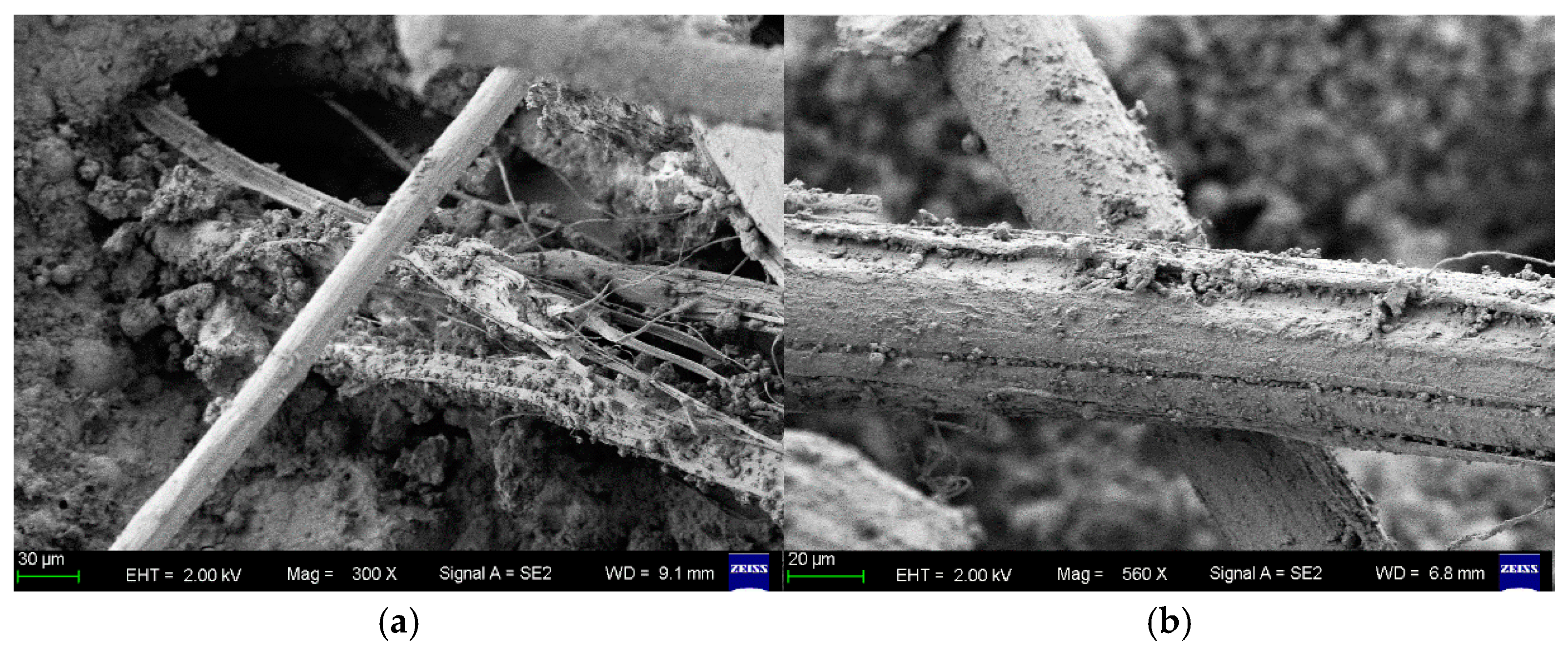

4.1. CT-Informed Meso-Scale Fiber–Matrix Damage Mechanisms

4.1.1. Steel Fibers: Multi-Scale Damage Suppression

4.1.2. PVA Fibers: Bond-Dependent Failure and Localized Damage

4.1.3. PE Fibers: Frictional Pull-Out and Dispersed Damage

4.2. Analysis of Fiber Synergy and Failure of Simple Superposition

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- SHPB dynamic splitting tests demonstrated that all specimens exhibited significant strain rate strengthening effects in terms of dynamic splitting strength, DIF, and energy dissipation capacity. Hybrid fibers specimens consistently outperformed single-fiber specimens, with SP1 showing the highest strength improvement (15.6% at the TS4 strain rate) among all mixes. The stress-time curves of hybrid fibers specimens, particularly those containing PE fibers, displayed fuller post-peak descending branches and more pronounced secondary stress peaks, indicating enhanced post-crack resistance. While failure modes transitioned from partial cracking at low strain rates to complete fragmentation at high strain rates, hybrid fibers specimens—especially those with polymer fibers—were able to maintain superior structural integrity.

- (2)

- Based on quantitative meso-scale damage analysis using industrial CT, it is demonstrated that the mono-PVA specimen exhibited the most severe internal damage, with the highest porosity (7.20%) and crack ratio (4.48%), along with the formation of penetrating large pores (maximum pore volume: 26.3 mm3) and a highly interconnected crack network (coordination number: 94). The hybrid steel fiber specimen showed optimal damage suppression, achieving the lowest porosity (3.29%) and crack ratio (1.76%), with the least severe internal damage distribution. In contrast, the hybrid PE fiber specimen, by inducing multi-scale pore distribution, not only provided certain inhibition of cracks and pores (with both porosity and crack ratio reduced compared to the P specimen) but, more importantly, led to a more dispersed and homogeneous damage distribution (crack-to-pore ratio: 39.32%, the lowest among all mixes).

- (3)

- The combined SHPB and CT results show that the dynamic performance of HFRCC is controlled by fiber–matrix interactions rather than by fiber volume alone. Hooked steel fibers with strong mechanical/chemical bonding effectively suppress internal damage, leading to the lowest porosity and crack ratios, whereas hydrophilic PVA fibers tend to rupture at high strain rates, producing more severe and connected cracking. Hydrophobic PE fibers, dominated by frictional pull-out and fibrillation, induce more dispersed microcracks and isolated pores. In SF–PVA and PE–PVA hybrids, these distinct interfacial behaviors act in a complementary, time-dependent manner, generating damage patterns and toughness levels that clearly deviate from a simple linear superposition of the mono-fiber responses.

6. Limitations and Future Work

- (1)

- Numerical Modeling

- (2)

- Assessment of Practical Engineering Viability

- (3)

- Regulatory Compliance and Sustainability

- (4)

- Integration with Emerging Construction Technologies:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noh, H.W.; Truong, V.D.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, D.J. Dynamic increase factors for fiber-reinforced cement composites: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yan, C. Long-Term Performance of PVA Fiber-Reinforced Cementitious Composites; China Building Materials Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Li, Q. Ultra-High-Toughness Cementitious Composites in High-Performance Building Structures; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Z. Experimental study on compressive behavior of PE-ECC under impact load. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1204083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. Comparative study on the effect of steel and plastic synthetic fibers on dynamic compression of UHPC. Compos. Struct. 2023, 324, 117570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kang, S.; Yoo, D.-Y. Effects of fibers on the mechanical properties of UHPC: A review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Zhou, Z.; Deifalla, A.F. Steel fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete: Fresh properties review. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2023, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, F.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; Huang, H.; et al. Hybrid Fiber Design Strategies for Improving Crack Resistance and Tensile Performance of Cementitious Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 150, 105234. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Chen, H.; Yu, J. Microstructure-Guided Toughness Enhancement in Fiber-Reinforced Cementitious Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 398, 132645. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Huang, B. Advances in Cementitious Composite Design: Multi-Scale Reinforcement, Fiber Synergy, and Durability Improvement. Materials 2024, 17, 1123. [Google Scholar]

- Maalej, M.; Quek, S.T.; Zhang, J.; Lee, B.Y.; Hsu, L.S.; Tan, D. Behavior of hybrid-fiber engineered cementitious composites subjected to dynamic tensile loading and projectile impact. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2006, 17, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Kim, D.J. Synergistic response of blending fibers in ultra-high-performance concrete under high-rate tensile loads. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 78, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Kim, G.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Nam, J.; Kobayashi, K. Effects of the strain rate and fiber blending ratio on the tensile behavior of hybrid steel–PVA fiber cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 106, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Pham, T.M.; Hao, H. Mechanical properties of high-strength concrete reinforced with hybrid basalt–polypropylene fibers under dynamic compression and split tension. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, W. Energy dissipation and fractal fragmentation of hybrid-fiber concrete under impact loading. Eng. Blasting 2023, 29, 25–32, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Bi, J.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic tensile properties of hybrid-fiber concrete based on digital image correlation. Mater. Rep. 2023, 37, 22030038. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Ou, C.; Xu, X. Microstructure analysis and dynamic splitting tensile tests of CF/SSF-reinforced coral-sand cement mortar. Explos. Shock Waves 2024, 44, 113101. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, M.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Song, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yang, L.; Xing, F. Dynamic splitting behavior of microcapsule-based self-healing cementitious composites under SHPB loading. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millon, O.; Kleemann, A.; Stolz, A. Influence of the fiber reinforcement on the dynamic behavior of UHPC. In Proceedings of the 1st International Interactive Symposium on UHPC, Des Moines, IA, USA, 18–20 July 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Shu, C.; Xu, S. Layered spalling tests on ultra-high-toughness cementitious composites. Eng. Mech. 2020, 37, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, C.; Quan, C.; Li, X. Spalling behaviour of hybrid-fiber high-strength concrete. J. Vib. Shock 2017, 36, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Mediamartha, B.; Yu, S. Simulation of the Mesoscale Cracking Processes in Concrete Under Tensile Stress by Discrete Element Method. Materials 2025, 18, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lou, Z.; Liu, X. Study on meso-scale pore defects of concrete based on CT images. J. Build. Mater. 2020, 23, 603–610. [Google Scholar]

- You, Q.; Wang, W.; Nan, C.; Liu, Y. Construction of meso-scale concrete model based on CT images. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 3385–3395. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Fan, Y. Meso-structural damage of C60 high-performance concrete at high temperature based on X-CT. J. Build. Mater. 2020, 23, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Y. Resistance of ultra-high-performance cementitious composites to repeated impacts. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 50, 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, P. CT-Based Quantitative Analysis of Crack Propagation and Internal Damage Evolution in Cement-Based Materials under Dynamic Loading. Materials 2023, 16, 3104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Macro–Mesoscale Mechanical Properties of Basalt–Polyvinyl Alcohol Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Low-Heat Portland Cement Concrete. Polymers 2023, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qiu, Z.; Hu, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, J. Macro-Meso Mechanical Behavior and Degradation Mechanisms of Silty Clay Subgrade Subjected to Coupled Traffic Load-ing and Dry-Wet Cycles. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 55, 101725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.-H.; Li, V.C. Strain-rate effects on the tensile behavior of strain-hardening cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 52, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.-H.; Sahmaran, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, V.C. Rheological Control in Production of Engineered Cementitious Composites. ACI Mater. J. 2009, 106, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, B.; Wang, Z. Effects of Hybrid PVA–Steel Fibers on the Mechanical Performance of High-Ductility Cementitious Composites. Buildings 2022, 12, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Khayat, K.H. Effect of Hybrid fibers on Fresh Properties, Mechanical Properties, and Autogenous Shrinkage of Cost-Effective UHPC. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 544.1R-96; State-of-the-Art Report on Fiber Reinforced Concrete. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1996.

- Xie, Q.; Shi, D.; Chen, X.; Peng, L.; Sun, R. Investigation on Dynamic Splitting Mechanical Properties of Weakly Cemented Siltstone Based on Digital Image Correlation Method and FracPaQ Algorithm. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondros, G. The Evaluation of Poisson’s Ratio and the Modulus of Materials of a Low Tensile Resistance by the Brazilian (Indirect Tensile) Test with Particular Reference to Concrete. Aust. J. Appl. Sci. 1959, 10, 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.-C.; Ma, J.; Cheng, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Li, J. Review of the Flattened Brazilian Test and Research on the Three-Dimensional Crack Initiation Point. Yantu Lixue 2019, 40, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Lv, N.; Lu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zong, Q. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties and Breakage of High-Temperature Carbon Fiber-Bar Reinforced Concrete under Impact Load. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ma, D. Critical Dynamic Stress and Cumulative Plastic Deformation of Calcareous Sand Filler Based on Shakedown Theory. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairagade, V.S.; Dhale, S.A. Hybrid fibre reinforced concrete—A state of the art review. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cement | Sand | Fly Ash | Water | Superplasticizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 583 | 467 | 700 | 298 | 19 |

| Fiber Type | Length (mm) | Diameter (µm) | Density (g/cm3) | Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA | 12 | 40 | 1.3 | 1600 |

| SF | 13 | 200 | 7.8 | 2000 |

| PE | 12 | 25 | 0.97 | 3100 |

| Mix ID | PVA | SF | PE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P | 26.0 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| SP1 | 19.5 (1.5%) | 39.0 (0.5%) | 0 |

| SP2 | 6.5 (0.5%) | 112.5 (1.5%) | 0 |

| EP1 | 19.5 (1.5%) | 0 | 4.85 (0.5%) |

| EP2 | 6.5 (0.5%) | 0 | 14.55 (1.5%) |

| Strain Rate ID | Pressure (MPa) | Projectile Velocity (m/s) | Wave Shaper | Measured Strain Rate Range (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS1 | 0.14 | 6.7 | Rubber Sheet | 5.4–6.8 |

| TS2 | 0.20 | 9.3 | Rubber Sheet | 9.1–10.6 |

| TS3 | 0.32 | 13.5 | Rubber Sheet | 11.5–20.5 |

| TS4 | 0.52 | 19.0 | Rubber Sheet | 23.3–31.0 |

| Mix ID | St-S (MPa) | TS1 | TS2 | TS3 | TS4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp-S (MPa) | DIF | Sp-S (MPa) | DIF | Sp-S (MPa) | DIF | Sp-S (MPa) | DIF | ||

| O | 4.5 | 13.6 | 3.0 | 18.5 | 4.1 | 21.2 | 4.7 | 20.8 | 4.6 |

| P | 5.6 | 16.9 | 3.0 | 18.1 | 3.2 | 19.4 | 3.5 | 22.5 | 4.0 |

| SP1 | 6.5 | 16.9 | 2.6 | 20.2 | 3.1 | 23.1 | 3.5 | 26.0 | 4.0 |

| SP2 | 6.3 | 19.6 | 3.1 | 19.5 | 3.1 | 20.4 | 3.2 | 22.5 | 3.6 |

| EP1 | 6.1 | 17.8 | 2.9 | 19.3 | 3.2 | 22.4 | 3.7 | 25.0 | 4.1 |

| EP2 | 5.8 | 16.4 | 2.8 | 17.6 | 3.0 | 18.1 | 3.1 | 23.9 | 4.1 |

| Parameter | P | SP2 | EP2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity | 7.20% | 3.29% | 6.48% |

| Maximum Areal Porosity | 12.51% | 10.35% | 9.28% |

| Minimum Areal Porosity | 4.76% | 2.07% | 4.13% |

| Maximum Pore Diameter (μm) | 965.54 | 667.27 | 531.24 |

| Average Pore Diameter (μm) | 42.60 | 35.20 | 39.43 |

| Maximum Pore Volume (μm3) | 2.63 × 1010 | 5.99 × 109 | 1.49 × 109 |

| Average Pore Volume (μm3) | 1.27 × 107 | 4.96 × 106 | 3.56 × 106 |

| Maximum Coordination Number | 94 | 13 | 24 |

| Number of Small Pores (0–100 μm) | 2,180,614 | 805,665 | 1,913,994 |

| Number of Medium Pores (100–500 μm) | 106,071 | 40,938 | 186,434 |

| Number of Large Pores (500–2000 μm) | 2135 | 852 | 2821 |

| Number of Extra-large Pores (>2000 μm) | 12 | 13 | 18 |

| Parameter | P | SP2 | EP2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porosity | 7.20% | 3.29% | 6.48% |

| Crack Ratio | 4.48% | 1.76% | 2.55% |

| Difference | 2.72% | 1.53% | 3.93% |

| Crack/Pore Ratio | 62.16% | 53.50% | 39.32% |

| Parameter | P | SP2 | EP2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crack Ratio | 4.48% | 1.76% | 2.55% |

| Max-Areal Crack Ratio | 8.93% | 8.04% | 6.73% |

| Min-Areal Crack Ratio | 2.75% | 0.86% | 0.92% |

| Equivalent Diameter (µm) | CZ-1: 14,823.8 CZ-2: 5436.29 | 11,163.8 | 12,728.6 |

| 3D Length (µm) | CZ-1: 51,223.5 CZ-2: 9709.58 | 51,480.8 | 51,418.8 |

| 3D Width (µm) | CZ-1: 28,317.1 CZ-2: 3609.54 | 24,415.1 | 29,665.0 |

| 3D Thickness (µm) | CZ-1: 31,844.7 CZ-2: 2958.68 | 17,594.3 | 34,958.2 |

| 3D Area (µm2) | CZ-1: 3.17 × 1010 CZ-2: 1.48 × 108 | 1.53 × 1010 | 2.42 × 1010 |

| 3D Volume (µm3) | CZ-1: 1.71 × 1012 CZ-2: 8.41 × 1010 | 7.29 × 1011 | 1.08 × 1012 |

| Angle with Z-axis (°) | CZ-1: 81.66 CZ-2: 86.29 | 78.07 | 77.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Cai, T.; Yao, W.; Wang, H.; Shu, X. Dynamic Splitting Tensile Behavior of Hybrid Fibers-Reinforced Cementitious Composites: SHPB Tests and Mesoscale Industrial CT Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234381

Li X, Cai T, Yao W, Wang H, Shu X. Dynamic Splitting Tensile Behavior of Hybrid Fibers-Reinforced Cementitious Composites: SHPB Tests and Mesoscale Industrial CT Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234381

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiudi, Tao Cai, Weilai Yao, Hui Wang, and Xin Shu. 2025. "Dynamic Splitting Tensile Behavior of Hybrid Fibers-Reinforced Cementitious Composites: SHPB Tests and Mesoscale Industrial CT Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234381

APA StyleLi, X., Cai, T., Yao, W., Wang, H., & Shu, X. (2025). Dynamic Splitting Tensile Behavior of Hybrid Fibers-Reinforced Cementitious Composites: SHPB Tests and Mesoscale Industrial CT Analysis. Buildings, 15(23), 4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234381