Structural Equation Model (SEM)-Based Productivity Evaluation for Digitalization of Construction Supervision

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Previous Studies

2.2. Review of Digital Technologies in the Construction Industry

2.3. Theoretical Framework for Technology Adoption

2.4. Initial Hypothesis Development and Variable Definition

Hypothesis Setup

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Method

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Composition of the Questionnaire and Measurement Tools

3.4. Setting of Variables

3.4.1. Definition of Productivity in Construction Supervision

3.4.2. Definition of Work Responsibility in Construction Supervision

3.4.3. Definition of Work Adoption in Construction Supervision

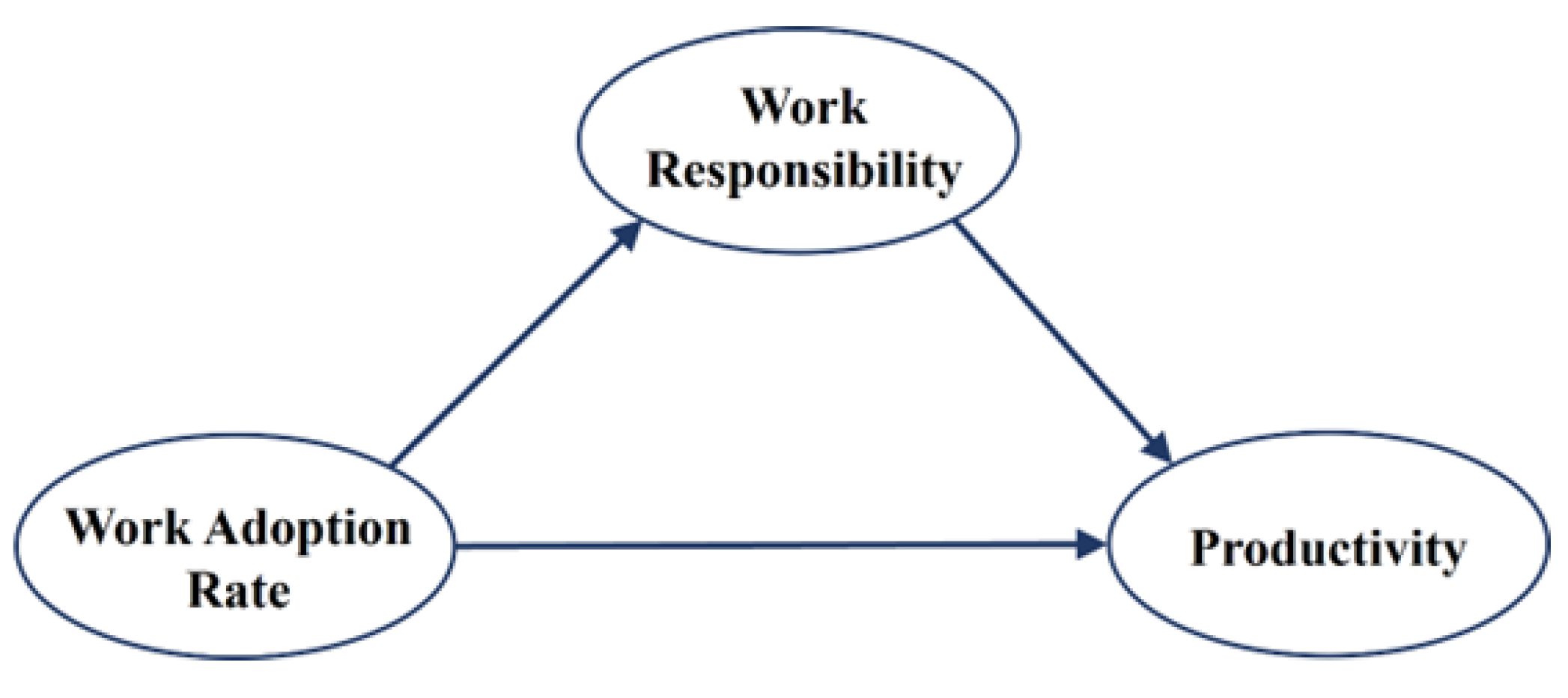

4. Research Model and Hypothesis Formulation

4.1. Research Model and Hypothesis Setting

- [Research Problem 1] Work adoption rate of technology will affect productivity.

- [Research Problem 2] Work responsibility will affect productivity.

- [Research Problem 3] Work adoption rate of technology will influence work responsibility.

4.1.1. Relationship Between Productivity and Work Adoption Rate

4.1.2. Relationship Between Productivity and Work Responsibility

4.1.3. Relationship Between Work Responsibility and Work Adoption Rate

5. Results

5.1. Data Analysis

5.1.1. Variable Validation

5.1.2. Supplementary Correlation and Regression Analysis

5.2. Analysis of Structural Model

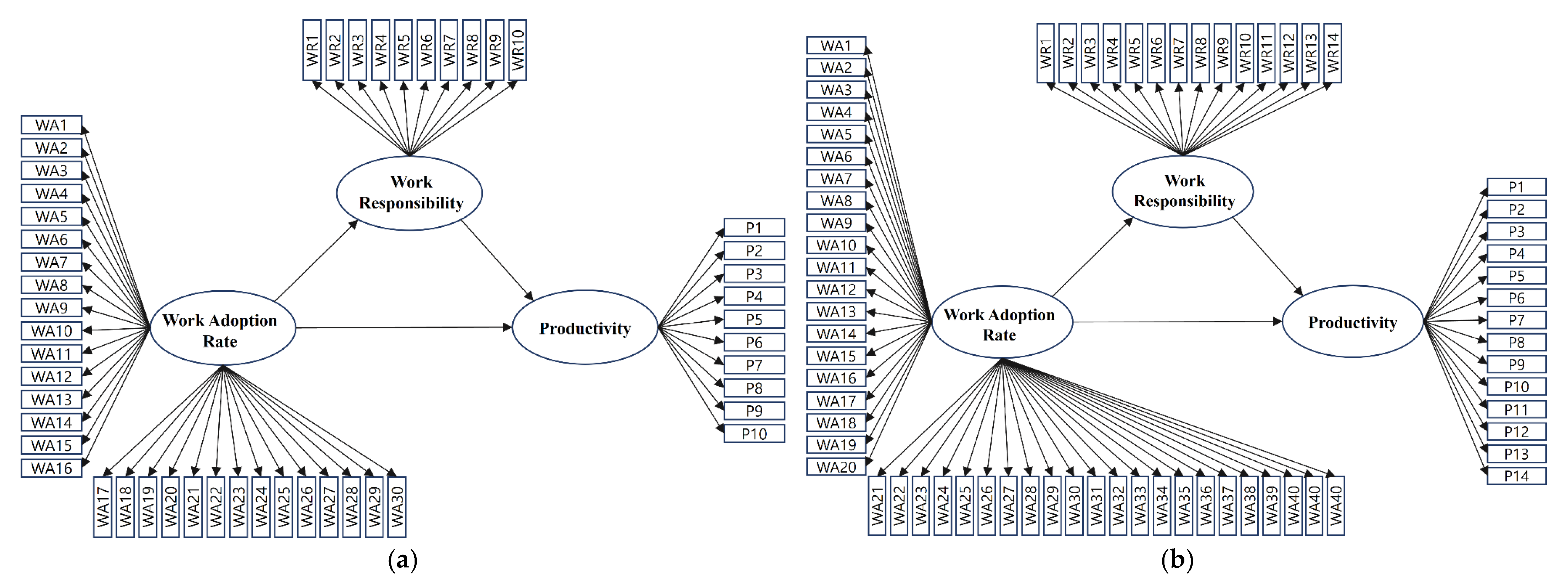

5.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results of the Initial Structural Model

5.2.2. Model Revision and Configuration of Final Structural Model

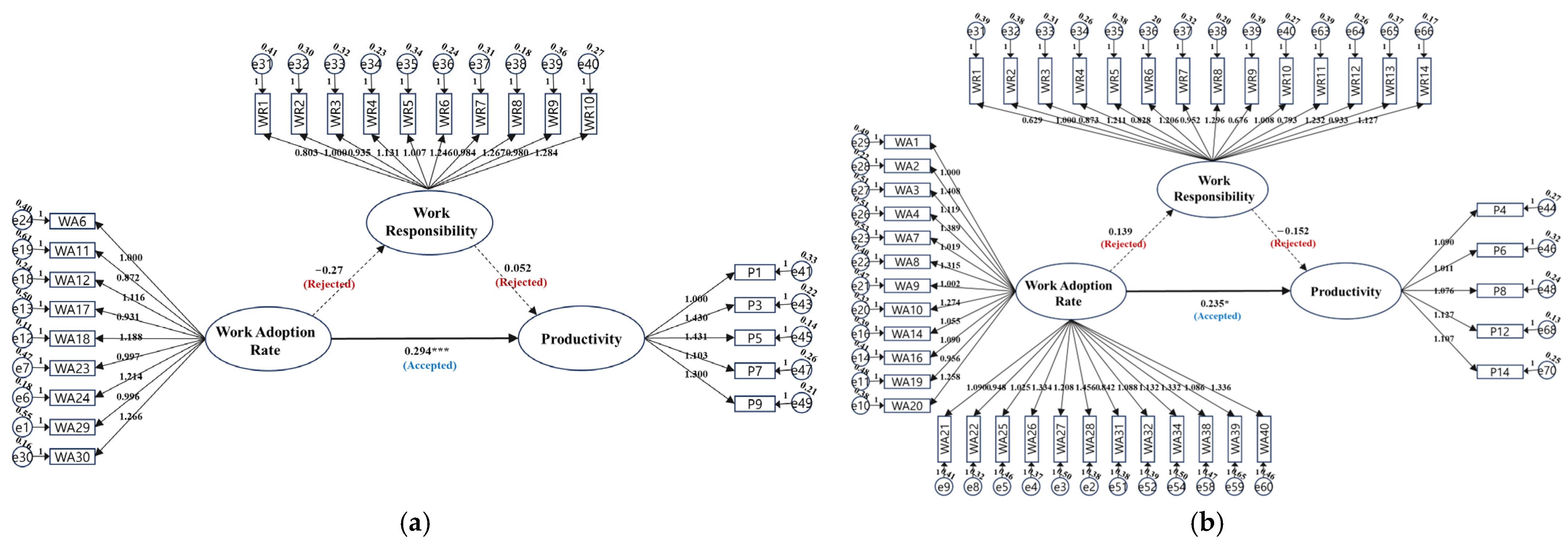

5.3. Hypothesis Testing Through Final Structural Model

6. Analysis of Evaluation Findings

6.1. Theoretical Analysis of Hypothesis Testing Results

6.1.1. Construction Work Type Perspective

6.1.2. Management Function Perspective

6.1.3. Variable Appropriateness and Interpretation Analysis

6.1.4. Theoretical Interpretation and Comparative Discussion

6.2. Practical Analysis of Hypothesis Testing Results

6.2.1. Construction Work Type Perspective

6.2.2. Management Function Perspective

7. Conclusions

7.1. Empirical Findings and Key Results

7.2. Discussion and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, G.B. Policy Review Tasks to Enhance the Utilization of Elderly Workers in the Construction Industry. Korea Res. Inst. Constr. Policy (RICON) BRIEF 2023, 55, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, J.; Fayek, A.R.; Meade, G.; Haas, C.; Manseau, A. Initial metrics and pilot program results for measuring the performance of the Canadian construction industry. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2008, 35, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.L.; Yoo, S.K.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.J. Comparing the efficiency and productivity of construction firms in China, Japan, and Korea using DEA and DEA-based Malmquist. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2015, 14, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaklar, B.G.; Erbaş, İ. The effect of motivational tools on the productivity of staff architects in developing countries: The case of Turkey. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 23, 1951–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, P.; Zhai, D.; Yasin, M. Relationship between changes in material technology and construction productivity. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, P.M.; Haas, C.T. Long-term impact of equipment technology on labor productivity in the US construction industry at the activity level. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2004, 130, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Luo, L.; Ding, C. Impacts of BIM policy on the technological progress in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry: Evidence from China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 23, 1997–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.P.; Choi, S.Y.; Son, T.H.; Choi, S.I. Current Status and Activation Strategies of Smart Technology Utilization by Domestic Construction Companies; Construction Economy Research Institute of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.H.; Kang, K.I.; Cho, H.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.R. Smart construction supervision solution for the digital transformation of construction supervision. Architecture 2024, 68, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.B.; Bae, S.J.; Kim, C.J.; Song, M.J.; Ham, J.H.; Kim, J.Y. Construction automation robot. Architecture 2024, 68, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J. A study on the development of an architectural inspection process model applied to building information modeling. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Des. 2011, 27, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, M.; Menassa, C.C.; Kamat, V.R. From BIM to digital twins: A systematic review of the evolution of intelligent building representations in the AEC-FM industry. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.C.; Moon, Y.M. Research on the direction of building an integrated smart platform at construction sites. J. Soc. Disaster Inf. 2024, 20, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, L.; Eriksson, K.; Lantz, B. Quantifying BIM investment value: A systematic review. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 23, 1384–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attencia, G.; Mattos, C. Adoption of digital technologies for asset management in construction projects. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2022, 27, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Pelosi, A.; Jia, Y.; Shen, X.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Yang, N. Implementation of technologies in the construction industry: A systematic review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 3181–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.J.; Choi, W.; Büyüköztürk, O. Deep learning—based crack damage detection using convolutional neural networks. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2017, 32, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Bulbul, T. An EEG-based mental workload evaluation for AR head-mounted display use in construction assembly tasks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y. Factors affecting the utilization of big data in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Han, S.; Zhu, Z. Blockchain technology toward smart construction: Review and future directions. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 03123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Browne, G.J.; Li, D. Adoption of building information modeling in Chinese construction industry: The technology-organization-environment framework. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 1878–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adane, M. Business-driven approach to cloud computing adoption by small businesses. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2022, 15, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, D.K.; Yeoh, K.W.; Song, Y. Quantification of spatial temporal congestion in four-dimensional computer-aided design. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Chun, H.; Chi, S. Multi-camera people counting using a queue-buffer algorithm for effective search and rescue in building disasters. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 2132–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Low, S.P.; Nair, K. Design for manufacturing and assembly (DfMA): A preliminary study of factors influencing its adoption in Singapore. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2018, 14, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry, J.; Karan, E.P.; Jalaei, F. Integrating BIM and GIS to improve the visual monitoring of construction supply chain management. Autom. Constr. 2013, 31, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Edwards, D.J.; Hosseini, M.R. Patterns and trends in Internet of Things (IoT) research: Future applications in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Cho, Y.K.; Zhang, S.; Perez, E. Case study of BIM and cloud–enabled real-time RFID indoor localization for construction management applications. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 05016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.P.; Balasubramanian, M.; Raj, S.J. Robotics in construction industry. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soto, B.G.; Agustí-Juan, I.; Hunhevicz, J.; Joss, S.; Graser, K.; Habert, G.; Adey, B.T. Productivity of digital fabrication in construction: Cost and time analysis of a robotically built wall. Autom. Constr. 2018, 92, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.R.; Lee, S.; Sun, C.; Jebelli, H.; Yang, K.; Choi, B. Wearable sensing technology applications in construction safety and health. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 03119007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrazovic, N.; Fischer, M. Assessment framework for additive manufacturing in the AEC industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliou, C.; Petrakis, E. Timing of technology adoption and product market competition. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2011, 29, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkvold, B.E. Challenges of IT implementation for supporting collaboration in distributed organizations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 1999, 8, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.G.; Ngo, J.; Teo, J.Z.K. Challenges and strategies for the adoption of smart technologies in the construction industry: The case of Singapore. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 05021014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, T.H.; Ok, H. A Study on Developing the System for Supporting Mobile-based Work Process in Construction Site. Smart Media J. 2017, 6, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.H. Smart Construction Supervising Service by Using Digital Technologies. Rev. Archit. Build. Sci. 2022, 66, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, T.; Martins, M.F. Literature review of information technology adoption models at firm level. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Eval. 2011, 14, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 1st ed.; Free Press of Glencoe: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M.; Chakrabarti, A.K. The Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.Y.; Heng, G.T.H.; Chang-Richards, A.; Chen, X.; Yiu, T.W. Impact of digital technology adoption on the comparative advantage of architectural, engineering, and construction firms in Singapore. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Chan, A.P. Critical review of labor productivity research in construction journals. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 30, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, K.N.; Ruwanpura, J.Y.; Jergeas, G.F. IT usage in Alberta’s building construction projects: Current status and challenges. Autom. Constr. 2008, 17, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoum, S.G. Factors influencing labor productivity on construction sites: A state-of-the-art literature review and a survey. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Yu, J. A Study on Critical Success Factors of Off-Site Construction—By Importance Performance Analysis. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 24, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, J.; Joo, S.; Ahn, C.; Park, M. A Method of Calculating Baseline Productivity by Reflecting Construction Project Data Characteristics. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 24, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyono, W.; Suryani, D.; Wulandari, Y. The relationship between workload, work stress and the level of conflict with nurse work fatigue at the Yogyakarta Islamic Hospital PDHI Yogyakarta City. J. Public Health UAD 2009, 3, 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, R.M.W.; Talhouni, B.T. Effects of Accelerated Working, Delays and Distruption on Labour Productivity; Chartered Institute of Building: Bracknell, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Automation and new tasks: How technology displaces and reinstates labor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 33, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I.Y.; Liu, A.M.; Fellows, R. Role of leadership in fostering an innovation climate in construction firms. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 30, 06014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, G. Field studies in construction equipment economics and productivity. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 137, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Lee, B. A Study of the Demands for Improvements in Speciality Construction Technology. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 23, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A. Why an IT Strategy Is Important? Chartered Institute of Building: Bracknell, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.; Seo, Y.; Shin, S.; Kim, D. Analyzing the Relationship between the Critical Safety Management Tasks and Their Effects for Preventing Construction Accidents using IPA Method. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 23, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Tae, Y.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, K. A Study of Improvements in the Standards of Cost Estimate for the New Excellent Technology in Construction. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 23, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cary, C.; Alison, S. Successful Stress Management for the Week; Kesaint Blanc: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Semaksiani, A.; Handaru, A.W.; Rizan, M. The effect of work loads and work stress on motivation of work productivity (empirical case study of ink-producing companies). Sch. Bull. 2019, 5, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, S.; Chang, K.; Miller, K. Relations among autonomy, attribution style, and happiness in college students. Coll. Stud. J. 2013, 47, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, M.; Özdemir, M.; Marum, K.P. Perceived autonomy support, friendship maintenance, and happiness. J. Psychol. 2011, 145, 537–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; You, Y.Y. The Study on the comparative analysis of EFA and CFA. J. Digit. Converg. 2017, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.I. Utilization and Circulation of Smart Phone Mobile Application of Travel Agencies Through Expansion of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung HEE University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Scholze, A.; Hecker, A. The job demands–resources model as a theoretical lens for the bright and dark side of digitization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 155, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, T.; Warraich, N.F.; Sajid, M. Examining the impact of technology overload at the workplace: A systematic review. Sage Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Seo, J.; Chi, S.; Hwang, J. Productivity analysis method of construction structural work using computer vision. J. Constr. Autom. Robot. 2022, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.S.U.; Shafiq, M.T.; Ullah, F. Automated computer vision-based construction progress monitoring: A systematic review. Buildings 2022, 12, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Title | Author(s) | Research Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | Smart Construction Supervision Solution for the Digital Transition of Supervision Tasks | Kim T.H et al., [9]. | Introduced digital supervision solutions to improve efficiency and reliability in analog-based supervision processes. |

| 2024 | Development of Digital-Based Construction Supervision and Automation Robot Technologies: Technology 4 Robotic Automation for Construction Supervision | Park J.B et al., [10]. | Proposed Scan-to-BIM and robotic automation methods for optimized supervision and monitoring. |

| 2011 | A Study on the Development of BIM-Based Construction Supervision Process Models | Kim S.J [11] | Analyzed BIM-based supervision models and interrelationships among supervision process variables. |

| 2021 | From BIM to Digital Twins: A Systematic Review of the Evolution of Intelligent Building Representations in the AEC-FM Industry | Deng et al., [12]. | Reviewed the evolution from BIM to digital twins and proposed a roadmap for future implementation. |

| 2024 | A Study on the Establishment of an Integrated Smart Platform for Construction Sites | Shin D.H et al., [13]. | Identified limitations in current smart platforms and suggested integration strategies for on-site application. |

| 2024 | A Study on the Establishment of an Integrated Smart Platform for Construction Sites | Gharaibeh L et al., [14]. | Reviewed BIM ROI evaluation methods and proposed a framework for quantifying BIM investment value. |

| Construction Industry Experience | Construction Supervision Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 5 years | 10 | Less than 3 years | 26 |

| 5~7 years | 2 | 3~5 years | 5 |

| 7~10 years | 2 | 5~7 years | 9 |

| 10~20 years | 7 | 7~10 years | 6 |

| More than 20 years | 61 | More than 10 years | 36 |

| Total | 82 | Total | 82 |

| Latent Variable | Construction Supervision Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Adoption Rate | Object recognition algorithm technology | Expected time reduction upon implementation of technology | 5-Point Likert Scale |

| Expected workforce reduction in upon implementation of technology | |||

| 3D vision technology | Expected time reduction upon implementation of technology | ||

| Expected workforce reduction in upon implementation of technology | |||

| PDF construction documentation system | Expected time reduction upon implementation of technology | ||

| Expected workforce reduction in upon implementation of technology | |||

| Level of difficulty in task execution before technology implementation | |||

| Level of difficulty in task execution after technology implementation | |||

| Productivity before technology adoption | |||

| Productivity after technology adoption | |||

| Classification | Measurement Variable | Num. of Evaluation Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Construction Work Type | Work Adoption Rate | 30 | 0.949 |

| Work Responsibility | 10 | 0.956 | |

| Productivity | 10 | 0.901 | |

| By Management Function | Work Adoption Rate | 42 | 0.969 |

| Work Responsibility | 14 | 0.969 | |

| Productivity | 14 | 0.907 |

| Observed Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Error | Statistic | Error | |

| Structural work: Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology 1 | 3.39 | 0.846 | −0.454 | 0.239 | 0.138 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology 1 | 3.01 | 0.928 | 0.056 | 0.239 | −0.332 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology 2 | 3.41 | 1.047 | −0.580 | 0.239 | −0.144 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology 2 | 3.20 | 0.975 | −0.275 | 0.239 | −0.287 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology 3 | 3.28 | 1.047 | −0.280 | 0.239 | −0.323 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology 3 | 2.94 | 0.953 | 0.189 | 0.239 | 0.098 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: level of difficulty in task execution after technology adoption | 2.89 | 0.922 | 0.063 | 0.239 | −0.484 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: increase in workload after technology adoption | 2.81 | 1.022 | 0.100 | 0.239 | −0.443 | 0.474 |

| Structural work: productivity after technology adoption | 3.63 | 0.832 | −0.258 | 0.239 | −0.410 | 0.474 |

| ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ |

| Reinforced concrete work: level of difficulty in task execution after technology adoption | 3.00 | 0.975 | 0.131 | 0.239 | −0.579 | 0.474 |

| Reinforced concrete work: increase in workload after technology adoption | 2.57 | 1.148 | 0.269 | 0.239 | −0.925 | 0.474 |

| Reinforced concrete work: productivity after technology adoption | 4.07 | 0.836 | −1.065 | 0.239 | 1.605 | 0.474 |

| Reinforced concrete work: increase in productivity after technology adoption | 4.00 | 0.901 | −0.828 | 0.239 | 0.511 | 0.474 |

| Observed Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Error | Statistic | Error | |

| General Management: Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology 1 | 3.35 | 0.935 | −0.491 | 0.266 | 0.432 | 0.526 |

| General Management: Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology 1 | 3.12 | 0.986 | −0.171 | 0.266 | 0.192 | 0.526 |

| General Management: Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology 2 | 3.54 | 0.996 | −0.641 | 0.266 | 0.365 | 0.526 |

| General Management: Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology 2 | 3.29 | 1.024 | −0.408 | 0.266 | 0.127 | 0.526 |

| General Management: Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology 3 | 3.52 | 0.820 | −0.424 | 0.266 | 0.291 | 0.526 |

| General Management: Expected workforce reduction upon adoption of technology 3 | 3.32 | 0.941 | −0.135 | 0.266 | 0.124 | 0.526 |

| General Management: level of difficulty in task execution after technology adoption | 3.11 | 0.832 | 0.186 | 0.266 | −0.077 | 0.526 |

| General Management: increase in workload after technology adoption | 3.04 | 1.059 | 0.053 | 0.266 | −0.395 | 0.526 |

| General Management: productivity after technology adoption | 3.67 | 0.754 | −0.251 | 0.266 | −0.127 | 0.526 |

| ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ | ︙ |

| Cost Management: level of difficulty in task execution after technology adoption | 3.12 | 1.011 | −0.030 | 0.266 | −0.444 | 0.526 |

| Cost Management: increase in workload after technology adoption | 2.93 | 1.152 | −0.053 | 0.266 | −0.712 | 0.526 |

| Cost Management: productivity after technology adoption | 3.84 | 0.853 | −0.298 | 0.266 | −0.534 | 0.526 |

| Cost Management: increase in productivity after technology adoption | 3.89 | 0.832 | −0.054 | 0.266 | −1.005 | 0.526 |

| Factor | Construction Work Type | Management Function |

|---|---|---|

| (CMIN) | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| TLI (Turker-Lewis index) | 0.324 | 0.324 |

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) | 0.353 | 0.345 |

| RMSEA (Root Mean Square of Approximation) | 0.202 | 0.183 |

| Category | Exclusion Criteria | Relationship with Model Appropriateness |

|---|---|---|

| p-value of Regression Weights | Over 0.05 | If the model appropriateness is good but the p-value is above 0.05, the variable is deleted. |

| Standardized Regression Weights | Under 0.5 | If the model appropriateness is good, variables with regression weights below 0.5 are not deleted. |

| Variances | Negative (“-“) | If the model appropriateness is good but the regression weight is negative, the variable is deleted. |

| Squared Multiple Correlations | Under 0.4 | If the model appropriateness is good, variables with regression weights below 0.4 are not deleted. |

| Factor | Construction Work Type | Management Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Revised | Initial | Revised | |

| (CMIN) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| TLI (Turker-Lewis index) | 0.324 | 0.584 | 0.324 | 0.536 |

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) | 0.353 | 0.625 | 0.345 | 0.560 |

| RMSEA (Root Mean Square of Approximation) | 0.202 | 0.216 | 0.183 | 0.172 |

| Factor | Value | C.R (t) | p-Value | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Type | Management Function | Work Type | Management Function | Work Type | Management Function | Work Type | Management Function | |

| The work adoption rate of technology is expected to affect productivity. | 0.294 | 0.235 | 5.037 | 1.972 | *** | 0.049 (*) | Accept | Accept |

| Work responsibility is expected to influence productivity. | 0.052 | −0.152 | 1.249 | −1.829 | 0.212 | 0.067 | Reject | Reject |

| The adoption rate of technology is expected to influence work responsibility. | −0.27 | 0.139 | −0.303 | 0.871 | 0.762 | 0.384 | Reject | Reject |

| Latent Variable | Measurement Variable | Construction Work | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Adoption Rate | Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology | Formwork | 0.997 |

| Reinforced concrete work | 0.996 | ||

| Designated and foundation work | 0.931 | ||

| Earthwork | 0.872 | ||

| Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology | Reinforced concrete work | 1.266 | |

| Formwork | 1.214 | ||

| Designated and foundation work | 1.188 | ||

| Earthwork | 1.116 | ||

| Structural work | 1.000 | ||

| Productivity | Productivity after technology adoption | Designated and foundation work | 1.431 |

| Earthwork | 1.430 | ||

| Reinforced concrete work | 1.300 | ||

| Formwork | 1.103 |

| Factor | Technology | Measurement Variable | Management Function | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work adoption rate | Object recognition algorithm | Expected time reduction upon adoption of technology | Contract Mgmt. | 1.025 |

| Design Mgmt. | 1.019 | |||

| General Mgmt. | 1.000 | |||

| Schedule Mgmt. | 0.956 | |||

| Safety Mgmt. | 0.842 | |||

| 3D vision technology | Contract Mgmt. | 1.208 | ||

| General Mgmt. | 1.119 | |||

| Cost Mgmt. | 1.086 | |||

| Design Mgmt. | 1.002 | |||

| Schedule Mgmt. | 0.948 | |||

| Object recognition algorithm | Expected workforce reduction in upon adoption of technology | General Mgmt. | 1.408 | |

| Contract Mgmt. | 1.334 | |||

| Cost Mgmt. | 1.332 | |||

| Design Mgmt. | 1.315 | |||

| Schedule Mgmt. | 1.258 | |||

| Safety Mgmt. | 1.088 | |||

| Quality Mgmt. | 1.055 | |||

| 3D vision technology | Contract Mgmt. | 1.408 | ||

| General Mgmt. | 1.389 | |||

| Cost Mgmt. | 1.336 | |||

| Schedule Mgmt. | 1.327 | |||

| Design Mgmt. | 1.274 | |||

| Safety Mgmt. | 1.132 | |||

| Quality Mgmt. | 1.090 | |||

| Productivity | Productivity after technology adoption | Safety Mgmt. | 1.127 | |

| Cost Mgmt. | 1.107 | |||

| Schedule Mgmt. | 1.076 | |||

| Quality Mgmt. | 1.011 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.H.; Park, C.H.; Yoo, W.S.; Kang, S.M. Structural Equation Model (SEM)-Based Productivity Evaluation for Digitalization of Construction Supervision. Buildings 2025, 15, 4380. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234380

Kim DH, Park CH, Yoo WS, Kang SM. Structural Equation Model (SEM)-Based Productivity Evaluation for Digitalization of Construction Supervision. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4380. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234380

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Da Hee, Chan Hyuk Park, Wi Sung Yoo, and Seong Mi Kang. 2025. "Structural Equation Model (SEM)-Based Productivity Evaluation for Digitalization of Construction Supervision" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4380. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234380

APA StyleKim, D. H., Park, C. H., Yoo, W. S., & Kang, S. M. (2025). Structural Equation Model (SEM)-Based Productivity Evaluation for Digitalization of Construction Supervision. Buildings, 15(23), 4380. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234380