An Analytical Review of Humidity-Regulating Materials: Performance Optimization and Applications in Hot and Humid Regions

Abstract

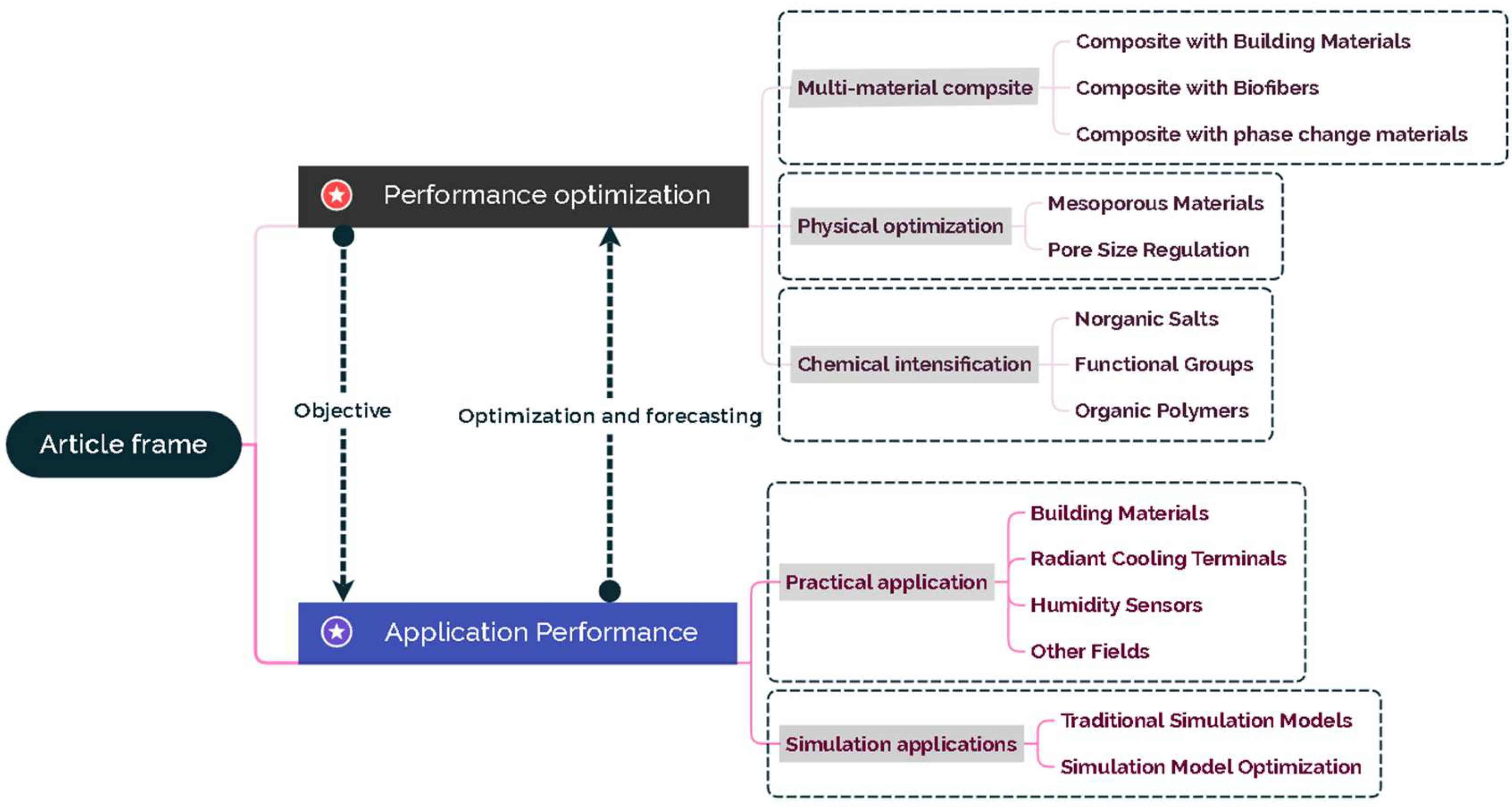

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Performance Optimization of Humidity Control Materials

3.1. Multi-Material Composites

- (1)

- Composite with Building Materials

- (2)

- Composite with Biofibers

- (3)

- Composite with phase change materials (PCM)

| Material | Reinforcement Material | MBV (g/(m2·%RH)) | Equilibrium Moisture Content | Relative Humidity (RH) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali-activated | Cork | 1.89 | / | / | [16] |

| Mortar | Biochar | 0.7 | 40.29 kg/m3 | 80% | [17,18] |

| Mortar | Corn Cob/ Wood Wool | 1.116/ 0.663 | 35%/15% | 90% | [26] |

| Clay | Olive Fiber | 1.739 | 30 kg/m3 | 80% | [27] |

| Inorganic humidity-regulating Brick | Poplar Wood Fiber | 1.917 | 5.5% | 80% | [24] |

| PCM | MIL-100(Fe) | 10.2 | 29.8% | 60% | [29] |

| PCM Microcapsules | Vesuvianite/Sepiolite/ Zeolite | 1.145/0.78/ 0.514 | / | / | [34] |

| PCM Microcapsules | Sepiolite-Zeolite Powder | / | 6.28% | 99% | [34] |

| PCM Microcapsules | Gypsum/Zeolite/ Expanded Vermiculite/Shell Powder | 0.495/4.36/ 2.82/0.433 | 1%/10%/12%/1% | 80% | [36] |

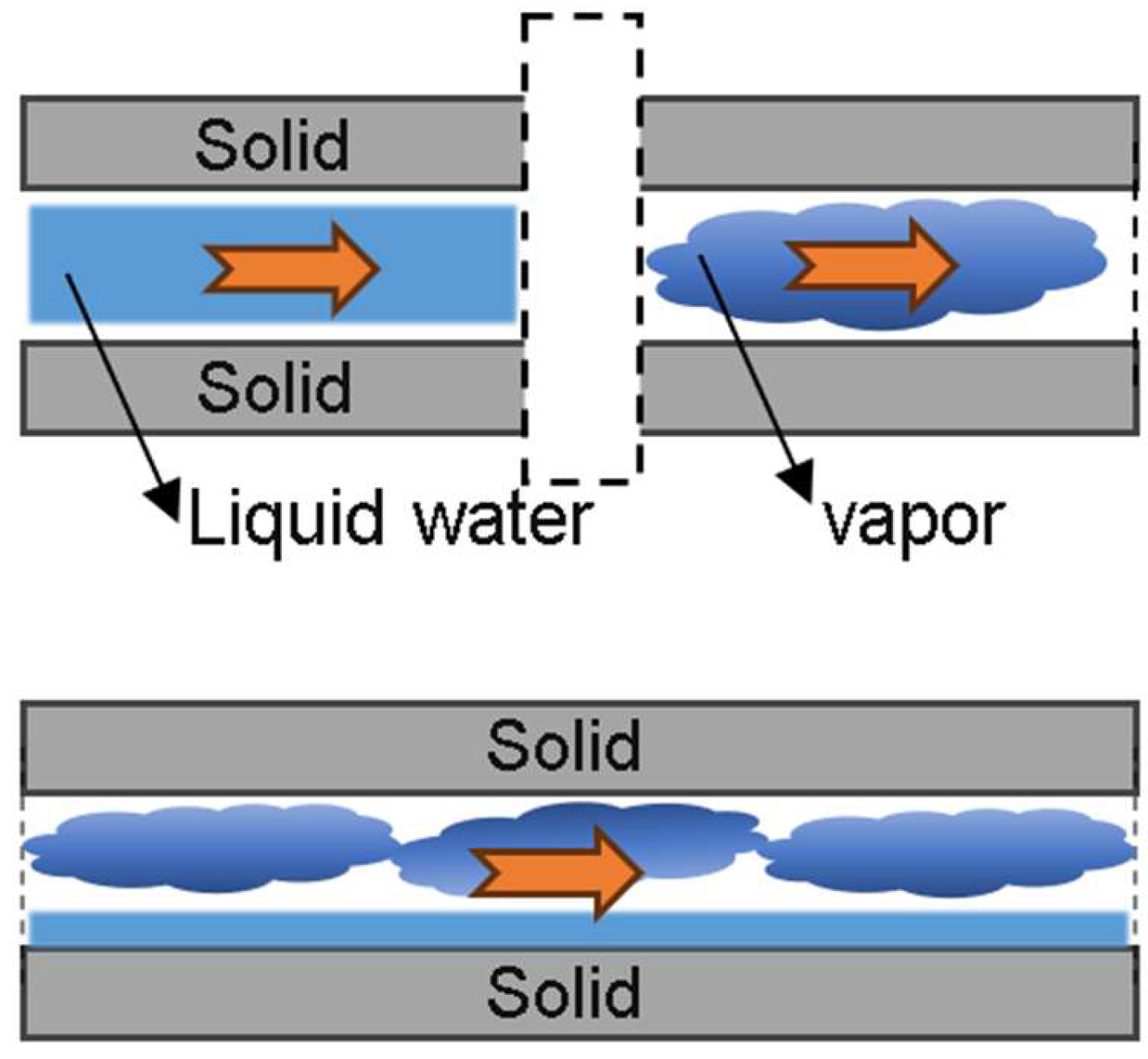

3.2. Physical Optimization

- (1)

- Mesoporous Materials

- (2)

- Pore Size Regulation

3.3. Chemical Enhancement

- (1)

- Inorganic Salts

- (2)

- Functional Groups

- (3)

- Organic Polymers

4. Application Performance

4.1. Practical Applications

- (1)

- Building Materials

- (2)

- Radiant Cooling Terminals

- (3)

- Humidity Sensors

- (4)

- Other Fields

4.2. Simulation Applications

- (1)

- Traditional Simulation Models

- (1)

- Moisture Transfer Models

- (2)

- Coupled Heat-Moisture Models

- (2)

- Simulation Model Optimization

- (1)

- Mathematical Models

- (2)

- Physical Models

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Humidity-regulating materials demonstrate exceptional moisture control capabilities and show significant potential in building envelope applications. Physical enhancement methods mainly involve optimizing pore sizes to the range of 3.0–7.4 nanometers to achieve optimal humidity regulation. Mesoporous materials, due to their suitable pore characteristics, have been widely used in the preparation of humidity-regulating materials. Chemical enhancement approaches include inorganic salt impregnation and functional group grafting techniques, which aim to improve moisture absorption properties. Moreover, when organic polymer materials such as polyacrylic acid and carboxymethyl cellulose are combined with porous materials through composite techniques like blending and copolymerization, the moisture absorption performance can be further enhanced.

- (2)

- Humidity-regulating materials play crucial roles in fields such as construction, radiative cooling systems, sensors, and water treatment. In building walls, they regulate indoor humidity to enhance comfort levels. In radiant cooling systems, they reduce the risk of condensation while improving energy efficiency. For humidity sensors, they enhance measurement accuracy and stability. In water treatment applications, they efficiently adsorb and decompose pollutants in wastewater, thus increasing treatment efficiency. With broad application prospects, future research may focus on the multifunctional integration of these materials to meet the high-efficiency demands across diverse fields.

- (3)

- Significant advancements have been made in modeling heat and moisture transfer in humidity-regulating materials. Simulation approaches have evolved from foundational laws (Fick’s, Darcy’s) to sophisticated models that account for multiple coupled factors. To improve predictive accuracy, researchers are integrating more environmental variables and material parameters, while refined geometric modeling enables precise simulation of moisture regulation. These developments provide a robust theoretical foundation for applying these materials in built environments.

- (4)

- Future HRM research will shift from passive materials to intelligent, multi-functional systems responsive to temperature, light, and pollutants. Key directions include integrating air purification and energy harvesting, advancing phase-change materials, employing AI and cross-scale modeling for inverse design, and prioritizing circular economy principles using industrial and agricultural waste. In construction applications, HRMs are expected to be incorporated as standardized components in prefabricated and 3D-printed building systems. Key goals include establishing HRMs in passive building standards, developing anti-condensation solutions for radiant cooling, validating performance through large-scale demonstrations, and creating practical design guidelines for applications in hot and humid regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| HRM | Humidity-regulating material |

| MBV | Moisture buffering Value |

| PFCHRM | Phase change humidity control material |

| PCM | Phase change material |

| EPS | Expanded polystyrene |

| MSN | Mesoporous silica nanoparticle |

| MOF | Metal–organic frameworks |

| PAA | Polyacrylic acid |

| PAM | Polyacrylamide |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| EP | Expanded perlite |

| CHM | Coupled heat-moisture |

| DLCCA | Diffusion-limited cluster-cluster aggregation |

References

- Mayernik, J.; Office of Energy Efficiency Renewable Energy. Buildings Energy Data Book; National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Ed.; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2015.

- Shaikh, P.H.; Nor, N.B.M.; Nallagownden, P.; Elamvazuthi, I.; Ibrahim, T. A review on optimized control systems for building energy and comfort management of smart sustainable buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.J.; Chou, S.K.; Yang, W.M.; Yan, J. Achieving better energy-efficient air conditioning—A review of technologies and strategies. Appl. Energy 2013, 104, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomson, A.E.; Sokolova, T.V.; Sosnovskaya, N.E.; Pekhtereva, V.S.; Goncharova, I.A.; Arashkova, A.A.; Kozhich, D.T. Prospects for the use of modified peat for indoor humidity control. Solid Fuel Chem. 2017, 51, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, G.; Baldinelli, G.; Bianconi, F.; Filippucci, M.; Fioravanti, M.; Goli, G.; Rotili, A.; Togni, M. Characterisation of wood hygromorphic panels for relative humidity passive control. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; El-Sharkawy, I.I.; Miyazaki, T.; Saha, B.B.; Koyama, S. An overview of solid desiccant dehumidification and air conditioning systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 46, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padfield, T. Humidity Buffering of the Indoor Climate by Absorbent Walls. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Building Physics in the Nordic Countries, Gothenburg, Sweden, 24–26 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Saatchi, D.; Oh, S.; Oh, I.-K. Biomimetic and Biophilic Design of Multifunctional Symbiotic Lichen-Schwarz Metamaterial. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2214580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.H.; Wang, K.-S.; Bac, B.H.; Nam, B.X. Humidity control materials prepared from diatomite and volcanic ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.F. Humidity control in the laboratory using salt solutions—A review. J. Appl. Chem. 1967, 17, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.M.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, X.W.; He, Y.F.; Zhu, Y.F.; Jiang, M.L. Preparation of acrylate-based copolymer emulsion and its humidity controlling mechanism in interior wall coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 71, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Tan, Y.; Jia, M. Preparation and characterization of diatomite/silica composite humidity control material by partial alkali dissolution. Mater. Lett. 2017, 196, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y. Review of evaluation methods for moisture absorption and desorption properties of humidity control materials. Mater. Rep. 2022, 36, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yuan, L. Research status and recent advances in composite humidity control materials. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2020, 39, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qin, M. Theory, preparation and performance of composite heat and humidity control materials. Archit. Pract. 2019, 2, 10–11. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=-PyPURV5YK0JbWU0uvE76XelugL6b80eER5iY682w132Bj_JNLU2-p_LlIbS5oC8GXGfXLNiEFmVyAeh3eg_fGXw6Ggh92oelBdyy6okMzP1ZNq1Ifc1LSl_vjO3CuqmOMbdTX83NrzDZYKarjmjag5ve-UVSWjbZ0sP6RPf9DrPa8rujN_JTQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Novais, R.M.; Carvalheiras, J.; Senff, L.; Lacasta, A.M.; Cantalapiedra, I.R.; Giro-Paloma, J.; Seabra, M.P.; Labrincha, J.A. Multifunctional cork–alkali-activated fly ash composites: A sustainable material to enhance buildings’ energy and acoustic performance. Energy Build. 2020, 210, 109739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.U.; Jeon, J.; Yun, B.Y.; Kang, Y.; Kim, S. Analysis of biochar-mortar composite as a humidity control material to improve the building energy and hygrothermal performance. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Min, F.; Zhang, N.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, L. Experimental study on water transfer mechanism of quicklime modified centrifugal dewatering clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xiao, P.; Kang, A.; Kou, C.; Chen, J. Preparation of biomass composites with high performance and carbon sequestration from waste wood fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, M.; Jia, W. Effects of corn stalk fiber content on properties of biomass brick. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 127, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreño-Rojas, M.A.; Porras-Amores, C.; Villoria-Sáez, P.; Morales-Conde, M.J.; Flores-Colen, I. Characterization and performance of building composites made from gypsum and woody-biomass ash waste: A product development and application study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, H.; Zou, S.; Liu, L.; Bai, C.; Zhang, G.; Fang, L. Experimental study on durability and acoustic absorption performance of biomass geopolymer-based insulation materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 361, 129575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouferra, R.; Bouchehma, A.; Bahammou, Y.; Essaleh, M.; Belhouideg, S.; Lamharrar, A.; Idlimam, A. Experimental study of relative humidity absorbed through capillarity of building material under isothermal conditions: Clay-Kaolin reinforced with Alfa fibers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 154, 107416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lu, Z. Thermal and moisture coupling performances of poplar fiber inorganic humidity control brick. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 348, 128656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda Múnera, J.C.; Gosselin, L. Impact of Density, relative Humidity, and fiber size on hygrothermal properties of barley straw for building envelopes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, M.; Lacasta, A.M.; Giraldo, M.P.; Haurie, L.; Correal, E. Bio-based insulation materials and their hygrothermal performance in a building envelope system (ETICS). Energy Build. 2018, 174, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzi, S.; Rubino, C.; Stefanizzi, P.; Petrella, A.; Boghetich, A.; Casavola, C.; Pappalettera, G. Hygrothermal properties of clayey plasters with olive fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahammou, Y.; Kouhila, M.; Tagnamas, Z.; Lamsyehe, H.; Lamharrar, A.; Idlimam, A. Hygroscopic behavior of water absorbed by capillarity and stabilization of a bio-composite building material: Clay reinforced with Chamarrops humilis fibers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 135, 106077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luo, F.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y. Myristic acid-tetradecanol-capric acid ternary eutectic/SiO2/MIL-100(Fe) as phase change humidity control material for indoor temperature and humidity control. J. Energy Storage 2023, 74, 109437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Taghavi, S.F.; Neshat Safavi, S.H.; Afsharpanah, F.; Yaïci, W. Thermal management of shelter building walls by PCM macro-encapsulation in commercial hollow bricks. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 47, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shannaq, R.; Farid, M.M.; Ikutegbe, C.A. Methods for the Synthesis of Phase Change Material Microcapsules with Enhanced Thermophysical Properties—A State-of-the-Art Review. Micro 2022, 2, 426–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; He, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Fu, B.; Tang, W. Preparation and characterization of fatty acid ternary eutectic mixture/Nano-SiO2 composite phase change material for building applications. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qin, M. Preparation and hygrothermal properties of composite phase change humidity control materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 98, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lei, W. Sepiolite-zeolite powder doped with capric acid phase change microcapsules for temperature-humidity control. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 595, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraine, Y.; Seladji, C.; Aït-Mokhtar, A. Effect of microencapsulation phase change material and diatomite composite filling on hygrothermal performance of sintered hollow bricks. Build. Environ. 2019, 154, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, L.; Mao, Z.; Shi, C. Hygrothermal performance of temperature-humidity controlling materials with different compositions. Energy Build. 2021, 236, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Sun, P.Z.; Fumagalli, L.; Stebunov, Y.V.; Haigh, S.J.; Zhou, Z.W.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Wang, F.C.; Geim, A.K. Capillary condensation under atomic-scale confinement. Nature 2020, 588, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Geng, W.; He, X.; Tu, J.; Ma, M.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Q. Humidity sensing performance of mesoporous CoO(OH) synthesized via one-pot hydrothermal method. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 280, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.C.; Kuok, C.H.; Liu, S.H. High-performance humidity control coatings prepared from inorganic wastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Asgar, H.; Kuzmenko, I.; Gadikota, G. Architected mesoporous crystalline magnesium silicates with ordered pore structures. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 327, 111381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jin, H.; Gu, A.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Mao, P.; Yang, Y.; Ding, S.; Chen, J.; Yun, S. Eco-friendly hierarchical porous palygorskite/wood fiber aerogels with smart indoor humidity control. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Hou, P.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J. Precise humidity control materials for autonomous regulation of indoor moisture. Build. Environ. 2020, 169, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Zu, K.; Qin, M.; Cui, S. A novel metal-organic frameworks based humidity pump for indoor moisture control. Build. Environ. 2021, 187, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Feng, Y.; Xue, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wang, R.; Ge, T. Mesoporous Silica-Guided Synthesis of Metal-Organic Framework with Enhanced Water Adsorption Capacity for Smart Indoor Humidity Regulation. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2300173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, G.; Gao, Y. Bioinspired Ant-Nest-Like Hierarchical Porous Material Using CaCl2 as Additive for Smart Indoor Humidity Control. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lin, X.; Xiong, Q.; Jiang, Q. Optimization of minor-LiCl-modified gypsum as an effective indoor moisture buffering material for sensitive and long-term humidity control. Build. Environ. 2023, 229, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.-J.; Lin, Y.-W.; Lin, W.-T.; Lee, W.-H.; Kuo, B.-Y.; Lin, K.-L. Functionalization of mesoporous Al-MCM-41 for indoor humidity control as building humidity conditioning material. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1299, 137024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Wang, J.; Diao, Y.; Hu, W. Study on Preparation and humidity-regulating Capabilities of Vermiculite/Poly(sodium Acrylate-acrylamide) Humidity Controlling Composite. Materials 2024, 17, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Qiu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, J.; Jing, Z. Hydrothermal synthesis of an expanded perlite based lightweight composite for indoor humidity regulating. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 351, 128960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y. Colorful Wall-Bricks with Superhydrophobic Surfaces for Enhanced Smart Indoor Humidity Control. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 13896–13901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Z.; Meijia, R.; Wenjian, H.; Linying, S.; Erlin, M.; Jun, L. Study on temperature-humidity controlling performance of zeolite-based composite and its application for light quality energy-conserving building envelope. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 69, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, S.; Dujardin, N.; Giovannacci, D.; Boudenne, A. Experimental and numerical evaluation of heat and mass transfer of a compressed raw earth block wall. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, T.; Peng, Y.; Cai, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, S. Experimental study on enhancing the waterproof and moisture-proof performance of foam open-cell reed-based insulation material. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Shi, Z.; Yi, X.-H.; Wang, P.; Li, A.; Wang, C.-C. MOFs helping heritage against environmental threats. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, G.; Cao, B.; Ji, Q. Experimental investigation on condensation characteristics of a novel radiant terminal based on sepiolite composite humidity-conditioning coating. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, L.; Wang, X.; Chang, J. Condensation retardation performance of metal-organic framework-based composite humidity-regulating materials in a radiation cooling room. Build. Environ. 2023, 243, 110630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Fan, F.; Cao, B.; Ji, Q.; Xu, G. Sepiolite based humidity-control coating specially for alleviate the condensation problem of radiant cooling panel. Energy 2023, 272, 127129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Xue, H.; Liu, X.; Jia, Z.; Xue, Q.; Zhang, J.; et al. Embedded SnO2/Diatomaceous earth composites for fast humidity sensing and controlling properties. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 303, 127137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, K.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, J.; Chen, Y. Enhanced-performance relative humidity sensor based on MOF-801 photonic crystals. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384, 126678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Guan, X.; Hou, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, S.; Fei, T.; Zhang, T. Humidity sensors based on metal organic frameworks derived polyelectrolyte films. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 602, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetya, N.; Okur, S. Investigation of the free-base Zr-porphyrin MOFs as relative humidity sensors for an indoor setting. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 377, 115713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; He, Q. Highly sensitive low humidity sensor by directional construction of ionic liquid functionalized MOF-303. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 425, 136992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Alayyafi, A.A.; Albedair, L.A.; El-Desouky, M.G.; El-Bindary, A.A. Efficient fabrication of a composite sponge for Cr(VI) removal via citric acid cross-linking of metal-organic framework and chitosan: Adsorption isotherm, kinetic studies, and optimization using Box-Behnken design. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 26, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, J. Removal of cadmium ion from wastewater by manganese oxides-loaded sludge biochar. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.K. The Rate of Drying of Solid Materials. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1921, 13, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, J. Über das Gleichgewicht und Bewegung, insbesondere die Diffusion von Gemischen. Sitzber. Akad. Wiss. Wien Math.-Naturwiss. Kl. Abt. 2a 1871, 63, 63–124. [Google Scholar]

- Buckinghan, E.A. Studies on the Movement of Soil Moisture; Bulletin No.: 38; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1907.

- Miller, E.E.; Miller, R.D. Theory of Capillary Flow: I. Practical Implications. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1955, 19, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, X.; Yang, B. Heat and moisture transfer of building envelopes under dynamic and steady-state operation mode of indoor air conditioning. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Janssen, H.; Roels, S. Hygrothermal Modelling of one-dimensional Wall Assemblies: Inter-model Validation between WUFI and DELPHIN. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2654, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Chen, Y.; Cao, C.; Lv, L.; Gao, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, C. Influence of materials’ hygric properties on the hygrothermal performance of internal thermal insulation composite systems. Energy Built Environ. 2023, 4, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarbi, Y.E.; Ferroukhi, M.Y.; Issaadi, N.; Poullain, P.; Bonnet, S. Assessment of hygrothermal performance of raw earth envelope at overall building scale. Energy Build. 2024, 310, 114119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroukhi, M.Y.; Belarbi, R.; Limam, K.; Bosschaerts, W. Experimental validation of a HAM-BES co-simulation approach. Energy Procedia 2017, 139, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fu, H.; Qin, M. Evaluation of Different Thermal Models in EnergyPlus for Calculating Moisture Effects on Building Energy Consumption in Different Climate Conditions. Procedia Eng. 2015, 121, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Kavgic, M.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Azzouz, A. Comparison of EnergyPlus and IES to model a complex university building using three scenarios: Free-floating, ideal air load system, and detailed. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 22, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, T.; Julien, B.; Amandine, P.; Mickael, P.; Woloszyn, M. Comparison of model numerical predictions of heat and moisture transfer in porous media with experimental observations at material and wall scales: An analysis of recent trends. Dry. Technol. 2019, 37, 1363–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defo, M.; Lacasse, M.A.; Laouadi, A. A comparison of hygrothermal simulation results derived from four simulation tools. J. Build. Phys. 2021, 45, 432–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paepcke, A.; Nicolai, A. Performance analysis of coupled quasi-steady state air flow calculation and dynamic simulation of hygrothermal transport inside porous materials. Energy Procedia 2017, 132, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luikov, A.V. Heat and Mass Transfer in Capillary-Porous Bodies. In Advances in Heat Transfer, 1st ed.; Irvine, T.F., Hartnett, J.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1964; Volume 1, pp. 123–184. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, D.A. The theory of heat and moisture transfer in porous media revisited. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1987, 30, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Ge, H.; Fazio, P.; Chen, G. Numerical investigation for thermal performance of exterior walls of residential buildings with moisture transfer in hot summer and cold winter zone of China. Energy Build. 2015, 93, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Bai, M.; Yuan, Y. Pore Network Simulation and Experimental Investigation on Water-Heat Transport Process of Soil Porous Media. J. Heat Transf. 2019, 141, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi Janetti, M.; Janssen, H. Effect of dynamic contact angle variation on spontaneous imbibition in porous materials. Transp. Porous Media 2022, 142, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, L. Transient simulation of coupled heat and moisture transfer through multi-layer walls exposed to future climate in the hot and humid southern China area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Cho, W.; Ozaki, A.; Lee, H. Influence of the moisture driving force of moisture adsorption and desorption on indoor hygrothermal environment and building thermal load. Energy Build. 2021, 253, 111501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, S.T.; Chareyre, B.; Tsotsas, E.; Kharaghani, A. Pore network modeling of phase distribution and capillary force evolution during slow drying of particle aggregates. Powder Technol. 2022, 407, 117627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, W.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Ma, G.; Wang, Q. Mesoscopic analysis of heat and moisture coupled transfer in concrete considering phase change under frost action. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, R.; Shadloo, M.S.; Hopp-Hirschler, M.; Hadjadj, A.; Nieken, U. Three-dimensional lattice Boltzmann simulations of high density ratio two-phase flows in porous media. Comput. Math. Appl. 2018, 75, 2445–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, H. Simultaneous Heat and Moisture Transport in Building Components. One- and Two-Dimensional Calculation Using Simple Parameters. In Research Reports; Fraunhofer IBP, Ed.; Fraunhofer IBP: Stuttgart, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kaoutari, T.; Louahlia, H. Experimental and numerical investigations on the thermal and moisture transfer in green dual layer wall for building. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alioua, T.; Agoudjil, B.; Boudenne, A.; Benzarti, K. Sensitivity analysis of transient heat and moisture transfer in a bio-based date palm concrete wall. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, M.; Sophie, M.; Yacine, A.O.; Lanos, C. Transient hygrothermal modelling of coated hemp-concrete walls. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2014, 18, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Chen, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, A. A validation of dynamic hygrothermal model with coupled heat and moisture transfer in porous building materials and envelopes. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, H. A comment on “A validation of dynamic hygrothermal model with coupled heat and moisture transfer in porous building materials and envelopes”. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 47, 103835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennai, F.; Abahri, K.; Belarbi, R. Contribution to the Modelling of Coupled Heat and Mass Transfers on 3D Real Structure of Heterogeneous Building Materials: Application to Hemp Concrete. Transp. Porous Media 2020, 133, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahanni, H.; Rima, A.; Abahri, K.; Hachem, C.E.; Assoum, H. Impact of the 3D morphology on the hygro-thermal transfer of hygroscopic materials: Application to spruce wood. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2069, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galy, T.; Mu, D.; Marszewski, M.; Pilon, L. Computer-generated mesoporous materials and associated structural characterization. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 157, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Li, Z.; Mahardika, M.A.; Wang, W.; She, Y.; Wang, K.; Patmonoaji, A.; Matsushita, S.; Suekane, T. Pore-scale investigation of wettability effects on drying process of three-dimensional porous medium. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 140, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Liu, R.; Liao, Y. Archetype Identification and Energy Consumption Prediction for Old Residential Buildings Based on Multi-Source Datasets. Buildings 2025, 15, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Qi, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chang, Y. Neural topic modeling of machine learning applications in building: Key topics, algorithms, and evolution patterns. Autom. Constr. 2025, 170, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yong, J.C.E.; Yu, L.J.; Olugu, E.U.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Muhieldeen, M.W. A review of research on intelligent technology in building air conditioning system optimisation. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 176, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, K.; Benekis, V.; Kokkinakos, P.; Askounis, D. Genetic algorithm-based multi-objective optimisation for energy-efficient building retrofitting: A systematic review. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Method | Most Probable Pore Size | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Compounds | Template Method | 3.93 nm | [38] |

| Silica | Hydrothermal Synthesis | 8.4 nm | [39] |

| Magnesium Silicate | Sol–Gel Method | 2.58 nm | [40] |

| Palygorskite/Wood Fiber Composite | Freeze-Drying | 10 nm | [41] |

| Metal–Organic Framework | Hydrothermal Synthesis | 2 nm | [43] |

| MIL-101/MCM-41 Composite | Template Method | 3.2 nm | [45] |

| Software Name | Transfer Dimensions | Core Features and Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| WUFI | 1D/2D/3D | Engineering-grade coupled heat-moisture model; mature for wall system analysis. | [69,70,71] |

| COMSOL | 1D/2D/3D | Multi-physics coupling (heat, moisture, radiation, convection); highly customizable. | [72,73] |

| EnergyPlus | 1D | Whole-building energy simulation; simplifies wall heat-moisture transfer to 1D. | [74,75] |

| MATCH | 1D | Transient hygrothermal calculations for hygroscopic materials; combines finite volume method with Fick’s law. | [76] |

| TRNSYS | 1D/2D | Modular dynamic simulation; supports system integration and control strategy optimization. | [73] |

| hygIRC | 1D | Fully coupled heat-air-moisture (HAM) model; emphasizes building durability. | [77] |

| DELPHIN | 1D/2D | Fully coupled heat-air-moisture (HAM) model; emphasizes moisture impact on building durability. | [69,70,78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Wang, T.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, P.; Yang, J. An Analytical Review of Humidity-Regulating Materials: Performance Optimization and Applications in Hot and Humid Regions. Buildings 2025, 15, 4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234376

Zhang D, Wang T, Zhou B, Zhang P, Yang J. An Analytical Review of Humidity-Regulating Materials: Performance Optimization and Applications in Hot and Humid Regions. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234376

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Dongliang, Tingyu Wang, Bo Zhou, Pengfei Zhang, and Jiankun Yang. 2025. "An Analytical Review of Humidity-Regulating Materials: Performance Optimization and Applications in Hot and Humid Regions" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234376

APA StyleZhang, D., Wang, T., Zhou, B., Zhang, P., & Yang, J. (2025). An Analytical Review of Humidity-Regulating Materials: Performance Optimization and Applications in Hot and Humid Regions. Buildings, 15(23), 4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234376