Optimization of Multi-Parameter Collaborative Operation for Central Air-Conditioning Cold Source System in Super High-Rise Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. System Modeling and Problem Formulation

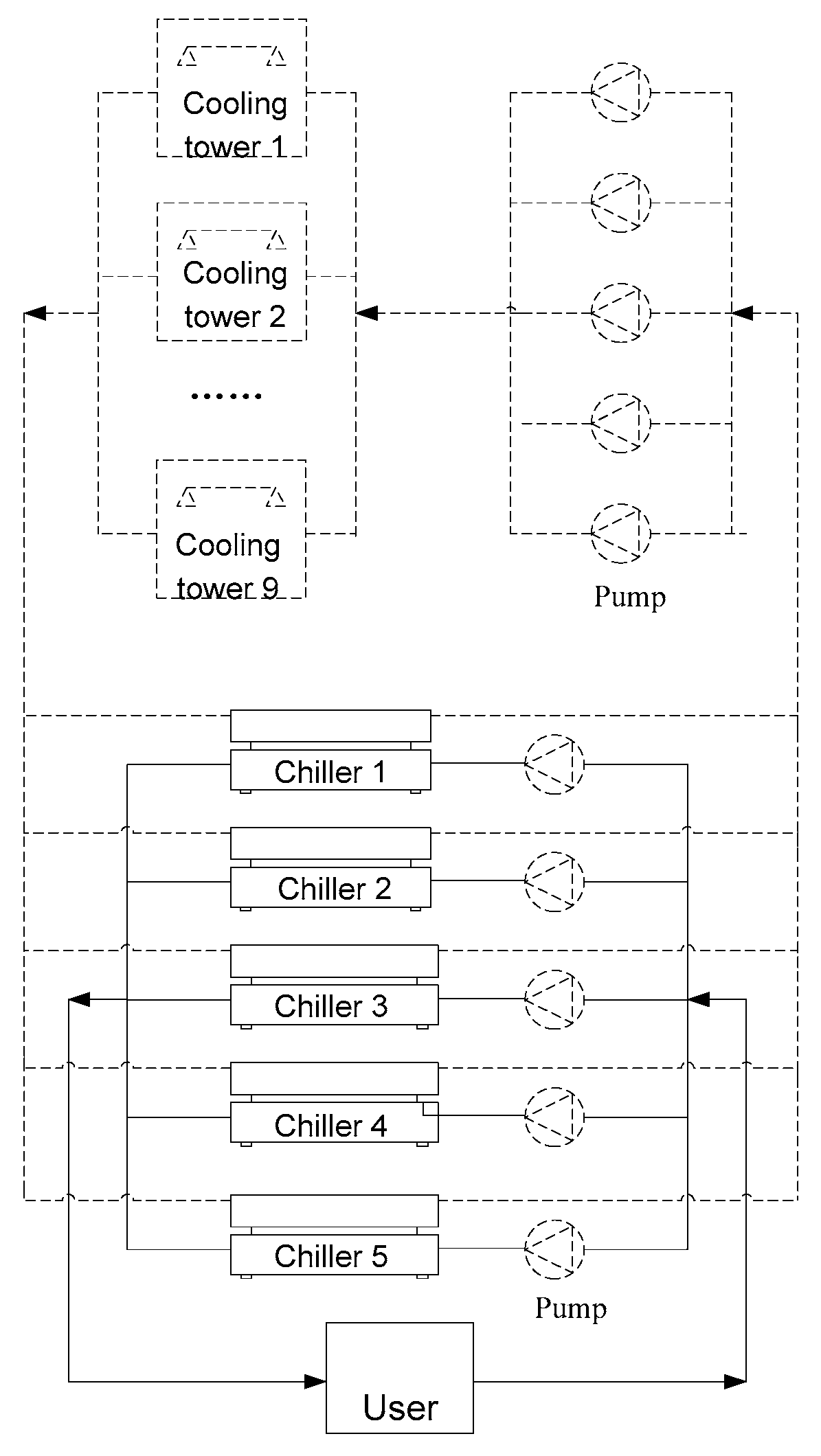

2.1. Project Overview

2.2. Equipment Energy Consumption Models

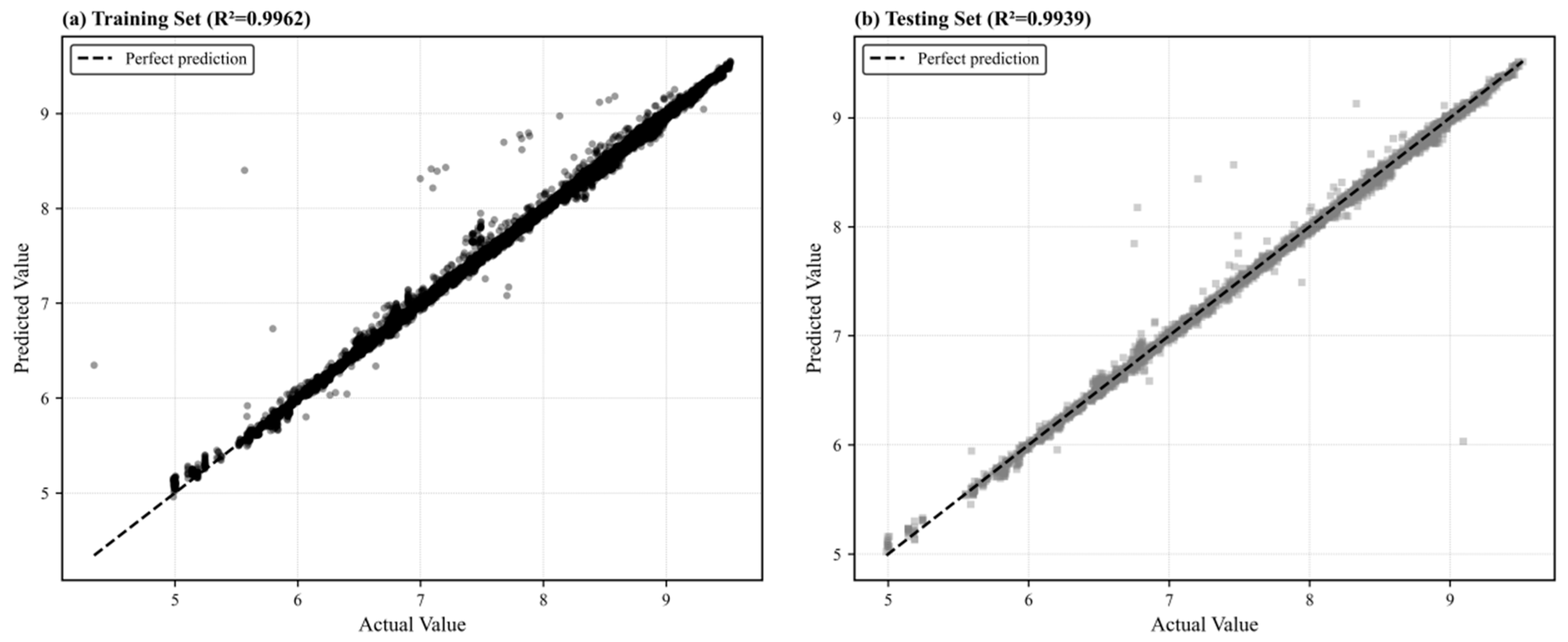

2.2.1. Chiller Model

2.2.2. Pump Model

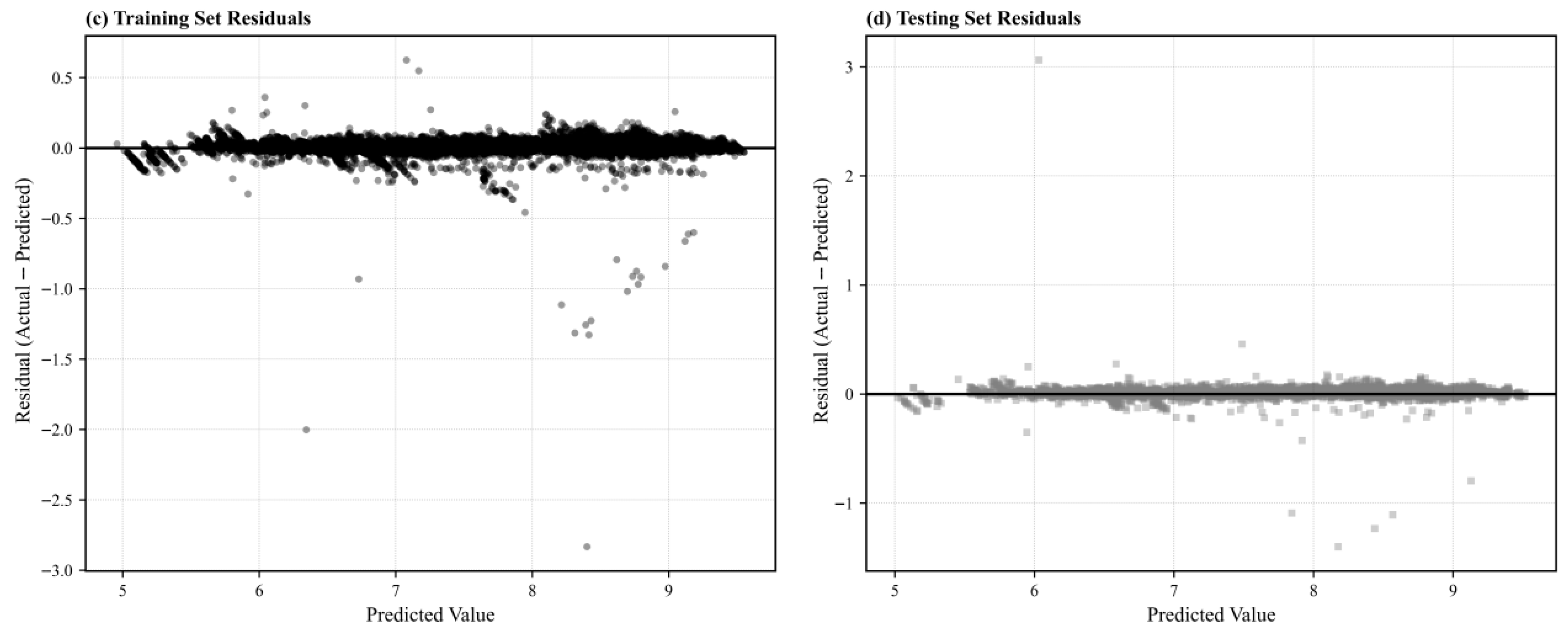

2.2.3. Cooling Tower Model

2.3. Problem Model

2.3.1. Optimization Objective

2.3.2. Optimization Variables and Constraints

3. Algorithm Design

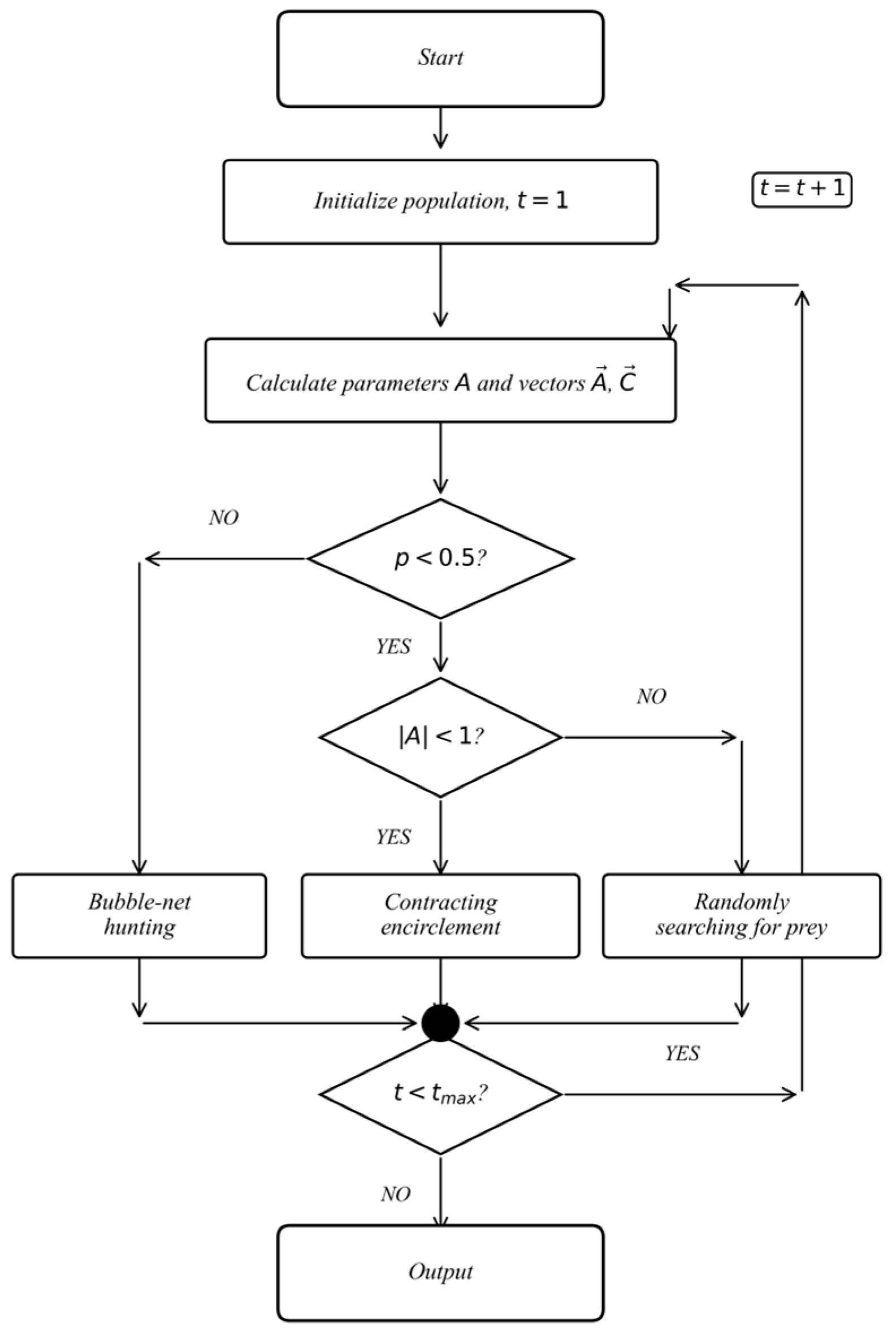

3.1. Application of the Whale Optimization Algorithm

3.2. Initialization and Solution Update

3.3. Constraint Control and Handling of Discrete Variables

3.3.1. Chiller Load Constraint Adjustment

- If , set (shut down the i-th chiller);

- If , (limit to the rated capacity of the i-th chiller).

3.3.2. Cooling Tower Approach Constraint Adjustment

- The physical lower bound Amin based on the cooling tower performance model (predicted by the gradient boosting regression model using the current wet-bulb temperature and flow ratio);

- The safety constraint that the cooling water supply temperature must not be lower than 18 °C, i.e., + A ≥ 18;

- The upper limit constraint of the cooling water supply temperature of 32 °C, i.e., + A ≤ 32 (an upper limit given from the perspective of system safe operation). Combining the above conditions, the approach boundary is ∈[max(Amin, 18 −), 32 − ]. If the updated approach exceeds this range, it is truncated to the feasible domain through a calculation function.

3.3.3. Total Cooling Load Balance Constraint

3.3.4. Discrete Variable (On/Off State) Processing

3.3.5. Convergence Control

4. Optimization Analysis

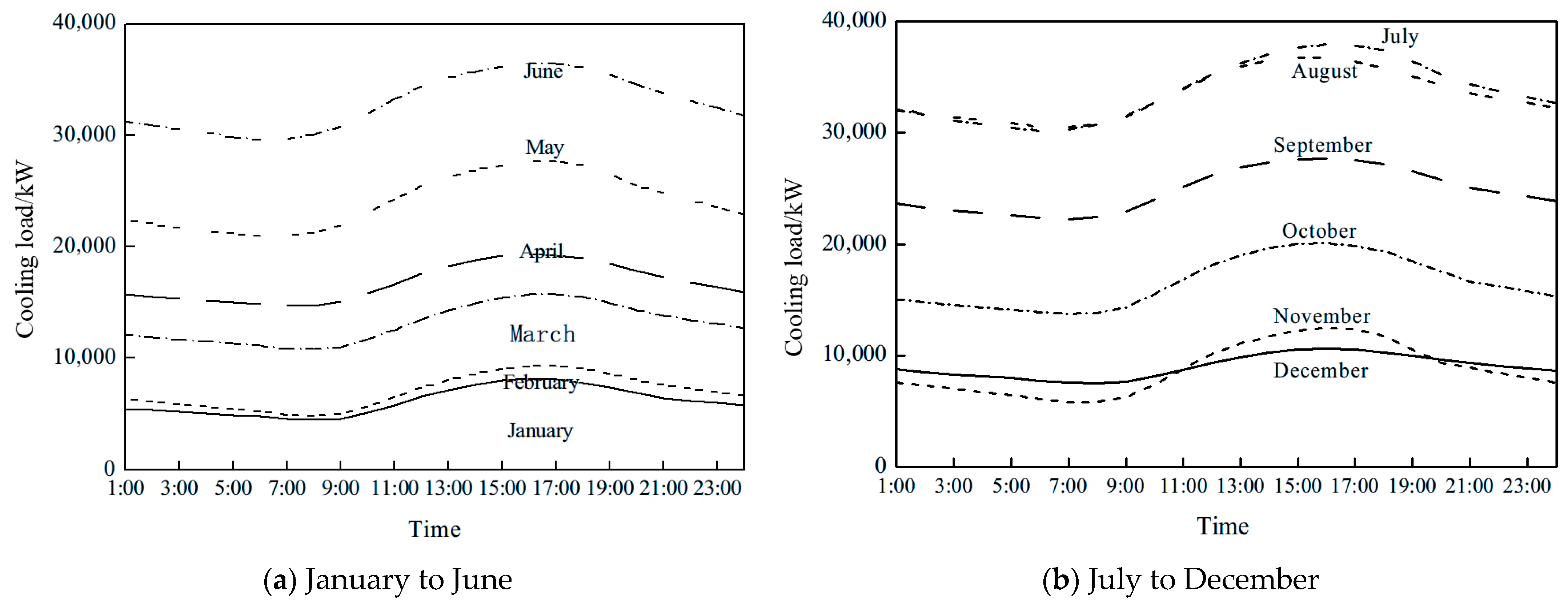

4.1. Building Cooling Load Characteristics

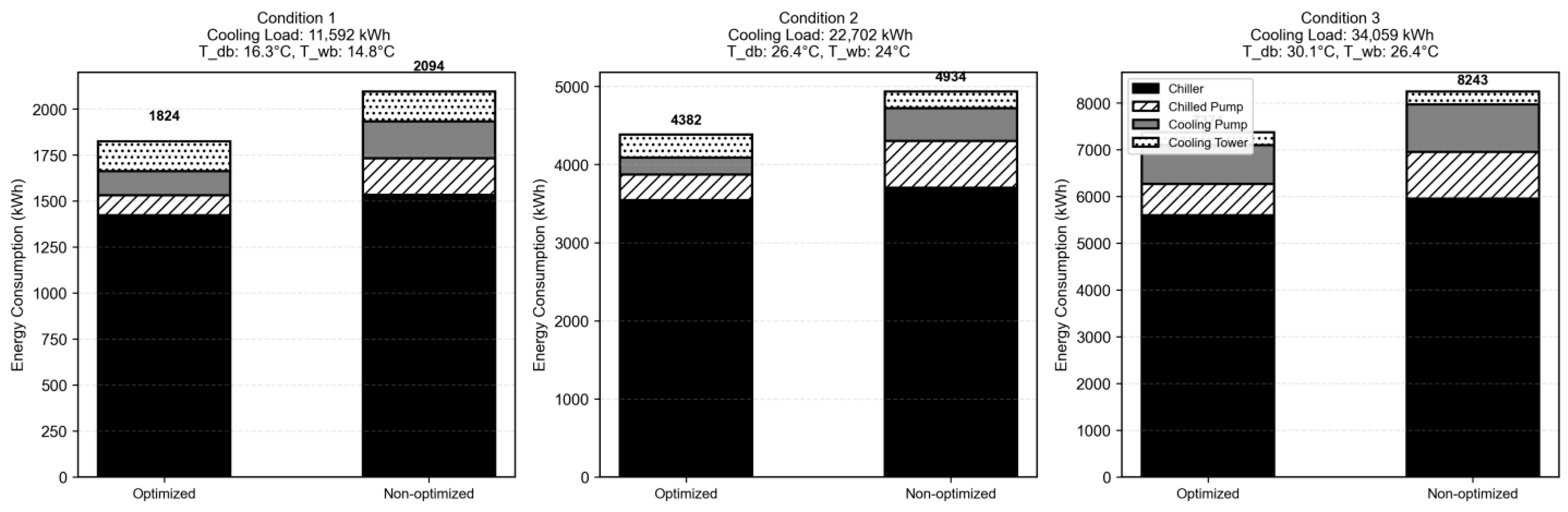

4.2. Comparison Before and After Optimization

4.2.1. Analysis of Operating Condition 1 (Low Load Scenario)

4.2.2. Analysis of Operating Condition 2 (Medium Load Scenario)

4.2.3. Analysis of Operating Condition 3 (High Load Scenario)

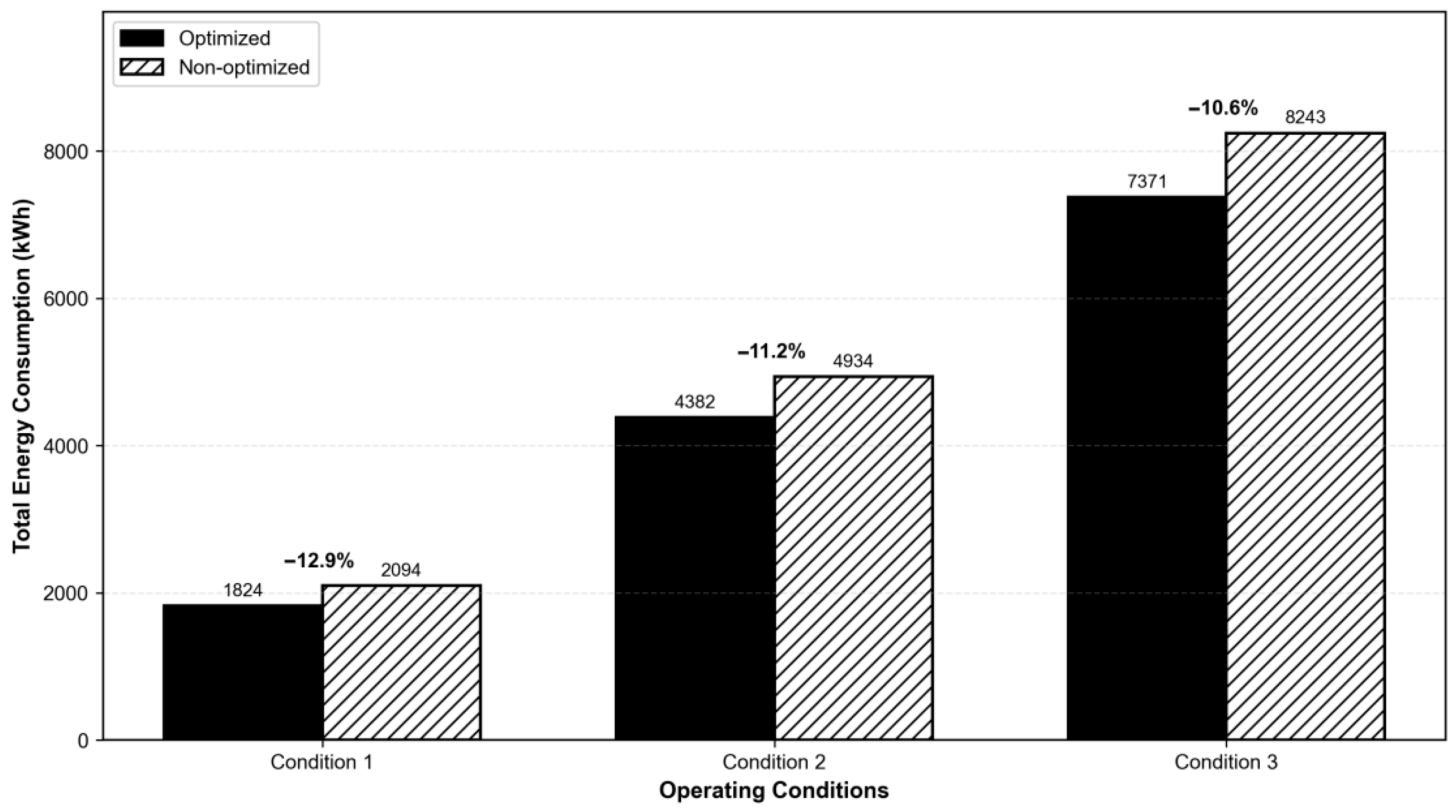

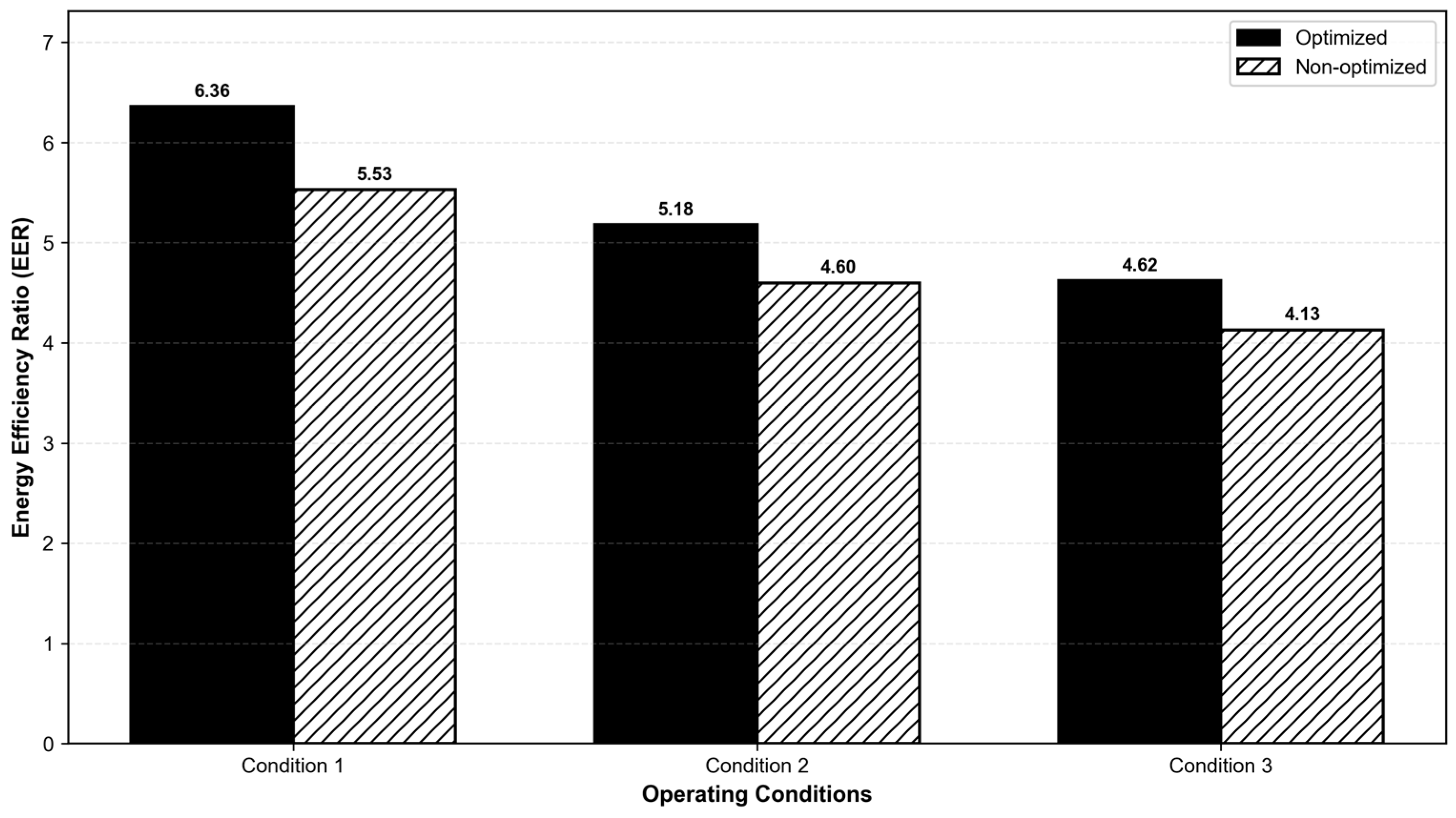

4.3. Comparative Analysis of the Three Operating Conditions

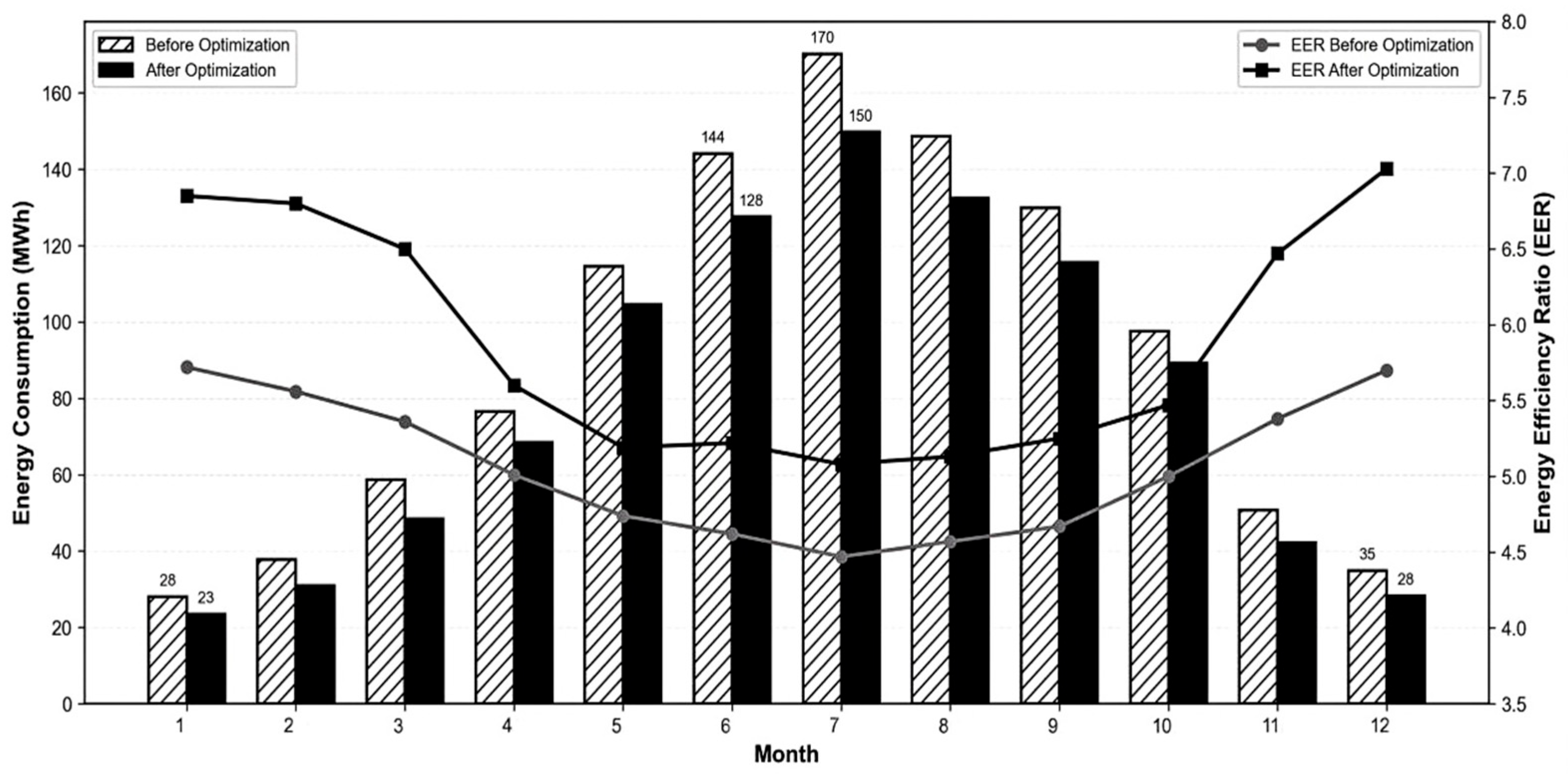

4.4. Annual Energy Consumption Comparison

5. Algorithm Comparison and Sensitivity Analysis

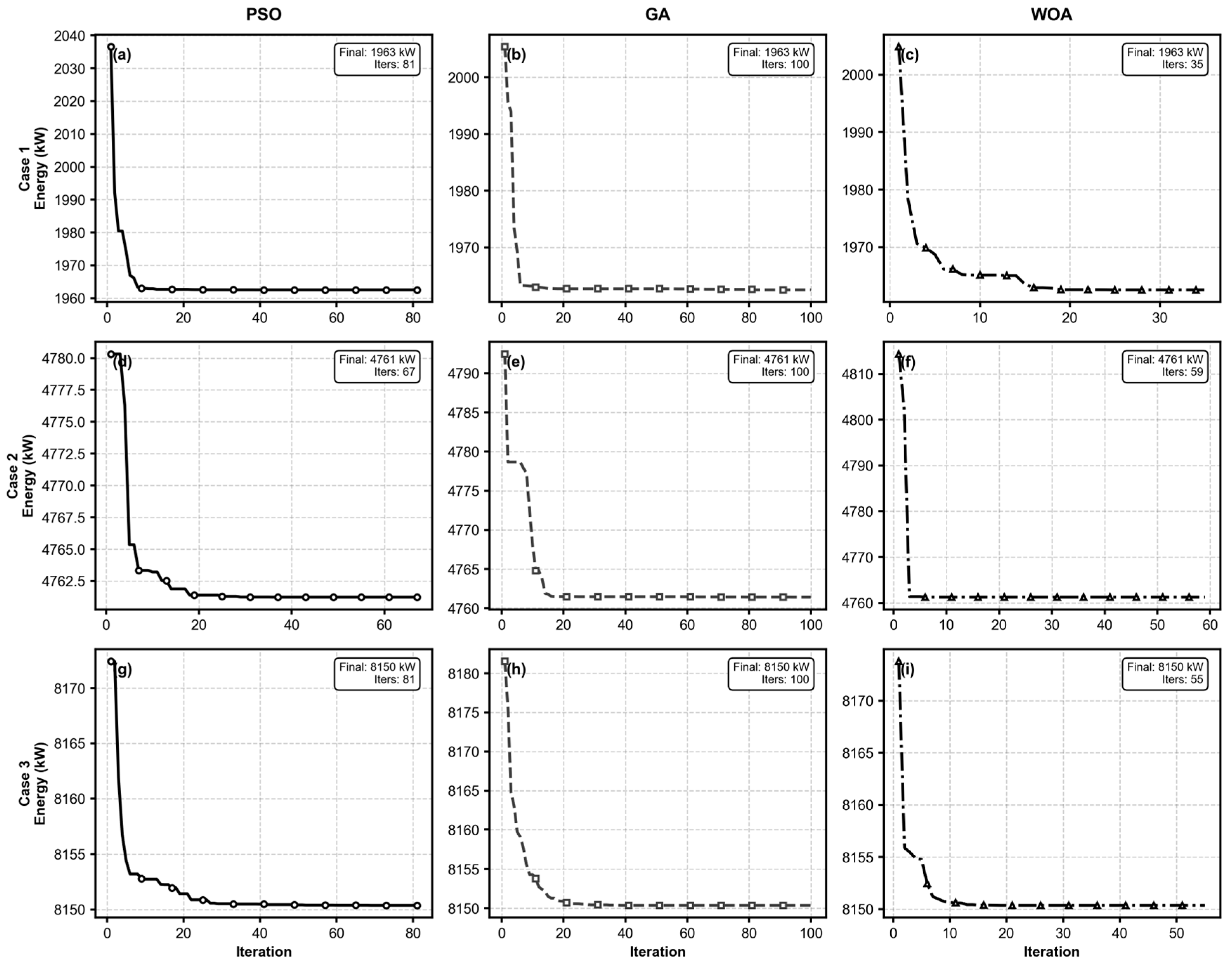

5.1. Optimization Algorithm Performance Comparison

5.2. Stability Analysis of the Algorithms

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Parameters

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BA | Building Automation |

| BQ | Bivariate Quadratic Model |

| COP | Coefficient of Performance |

| CTI | Cooling Technology Institute |

| CSA | Cuckoo Search Algorithm |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| DeST | Designer’s Simulation Toolkit |

| DQN | Deep Q-Networks |

| EER | Energy Efficiency Ratio |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regressor |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| HVAC&R | Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning, and Refrigeration |

| IPLV | Integrated Part-Load Value |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| MP | Multivariate Polynomial Regression |

| PLR | Part-Load Ratio |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SSA | Salp Swarm Algorithm |

| WOA | Whale Optimization Algorithm |

References

- Berardi, U. A cross-country comparison of the building energy consumptions and their trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 123, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, M.; Pérez-Lombard, L.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R.; Yan, D. A review on buildings energy information: Trends, end-uses, fuels and drivers. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.; Wong, V.T.; Yow, A.K.; Yuen, P.L.; Chao, C.Y. Development and performance evaluation of a chiller plant predictive operational control strategy by artificial intelligence. Energy Build. 2022, 262, 112017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.H.; Park, J.; Yeon, S.H.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, K.H. Particle swarm optimization for multi-chiller system: Capacity configuration and load distribution. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 110953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parouha, R.P.; Verma, P. A systematic overview of developments in differential evolution and particle swarm optimization with their advanced suggestions. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 10448–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Feng, M.; Fan, H.; Cao, R.; Gao, Q. Optimization control strategy for a central air conditioning system based on AFUCB-DQN. Processes 2023, 11, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhao, A.; Zong, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, M. Optimal chiller loading by improved sparrow search algorithm for saving energy consumption. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qin, L.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Sheng, W. Optimal chiller loading based on flower pollination algorithm for energy saving. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 93, 109884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, B. Low-carbon economic operation of integrated energy system considering carbon emissions of electric energy storage devices. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 2334–2342. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yue, Y.; Li, B. Microgrid optimization based on Archimedean chaotic elite whale algorithm. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 12577–12584. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, M. Bi-level planning of distributed power sources based on improved whale algorithm. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 11294–11302. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J.M.; Ng, K.C. A general thermodynamic model for absorption chillers: Theory and experiment. Heat Recovery Syst. CHP 1995, 15, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.; Lu, W.C. An evaluation of empirically-based models for predicting energy performance of vapor-compression water chillers. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 3486–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, F.; Lam, V. Chiller models for plant design studies. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 1998, 19, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, T.A.; Andersen, K.K. An evaluation of classical steady-state offline linear parameter estimation methods applied to chiller performance data. HVACR Res. 2002, 8, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.E. Methodologies for the Design and Control of Central Cooling Plants. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 1988. Available online: https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/46694/Braun1988.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Yan, D.; Zhou, X.; An, J.; Kang, X.; Bu, F.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, H.; et al. DeST 3.0: A new-generation building performance simulation platform. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 1849–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50189-2015; Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

| Equipment Type | Key Technical Parameters | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Chiller 1 | Chilled water: 7 °C (inlet), 12 °C (outlet); Cooling water: 31 °C (inlet), 36 °C (outlet); Capacity: 4922 kW; Power: 859.4 kW; IPLV: 9.775; EER: 5.727; Chilled water flow: 844.9 m3/h; Cooling water flow: 988.9 m3/h; Chilled water pressure drop: 65.6 kPa; Cooling water pressure drop: 63.9 kPa | York Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Chiller Model YKQ5Q1K25DBH |

| Chillers 2–5 | Chilled water: 7 °C (inlet), 12 °C (outlet); Cooling water: 31 °C (inlet), 36 °C (outlet); Capacity: 8439 kW; Power: 1377 kW; IPLV: 7.504; EER: 6.13; Chilled water flow: 1448.6 m3/h; Cooling water flow: 1688.4 m3/h; Chilled water pressure drop: 78.4 kPa; Cooling water pressure drop: 71.4 kPa | York Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Chiller Model YKV8W6K45DJH |

| Chilled Water Pump 1 | Power: 110 kW; Head: 38 m; Flow rate: 847 m3/h | WiLO Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Pump Model SCH250/360-110/4 |

| Chilled Water Pumps 2–5 | Power: 200 kW; Head: 38 m; Flow rate: 1452 m3/h | WiLO Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Pump Model SCH300/430-200/4 |

| Cooling Water Pump 1 | Power: 110 kW; Head: 26 m; Flow rate: 1094 m3/h | WiLO Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Pump Model SCH250/380-110/4 |

| Cooling Water Pumps 2–5 | Power: 200 kW; Head: 26 m; Flow rate: 1861.75 m3/h | WiLO Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Pump Model SCH300/430-200/4 |

| Cooling Towers 1–9 | Power: 37 kW; Hot water temperature: 36 °C; Cold water temperature: 31 °C; Flow rate: 866 m3/h; Wet-bulb temperature: 28 °C | EVAPCO Manufacturer’s Technical Manual for Cooling Tower Model LCCM-N-800 |

| Pump Type | Pump ID | Rated Power (kW) | Rated Flow (m3/h) | Rated Head (m) | b0 | b1 | b2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chilled Water Pump | CHWP-1 | 110 | 847 | 38 | 46.13 | 0.001580 | −0.00001537 |

| Chilled Water Pump | CHWP-2 | 200 | 1452 | 38 | 49.15 | 0.000220 | −0.00000545 |

| Cooling Water Pump | CWP-1 | 110 | 1094 | 26 | 36.00 | 0.002843 | −0.00001103 |

| Cooling Water Pump | CWP-2 | 200 | 1862 | 26 | 45.00 | 0.001200 | −0.00000600 |

| Parameter | Meaning | Calculation/Value Method |

|---|---|---|

| Rated power of the cooling tower (kW) | Equipment nameplate parameter | |

| Rated water flow of the cooling tower (m3/h) | Equipment nameplate parameter | |

| Actual water flow of the cooling tower (m3/h) | Actual operating parameter | |

| η | Performance coefficient under current operating conditions | ( |

| Performance coefficient under base operating conditions | ( | |

| C | Unit conversion coefficient | C = 0.871 |

| Equipment Category | Variable Description | Variable Symbol | Unit | Constraint | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooling Tower | Cooling Tower Approach temperature | °C | 2.0~8.0 | Difference between the cooling water outlet temperature and the wet-bulb temperature | |

| Number of Operating Cooling Towers | Units | 1~9 | Must match the number of chillers and cooling water pumps in operation | ||

| Flow Distribution of Cooling Towers | - | 0.3~1 (Proportion of single-unit flow to rated flow) | Single-unit flow must not be lower than 30% of the rated flow (to avoid uneven heat dissipation due to low flow) | ||

| Chiller | Number of Operating Chillers | Units | 1~5 | Must meet the total cooling load demand of the system | |

| Load Distribution of Operating Chillers | - | 0.15~1 (Proportion of single-unit load to rated load) | Single-unit load must not be lower than 15% of the rated capacity (to prevent frequent start-stop of equipment) | ||

| Chilled Water Pump | Number of Operating Chilled Water Pumps | Units | 1~5 | Must be adapted to the number of chillers in operation | |

| Operating Frequency of Chilled Water Pumps | Hz | 30.0~50.0 | Set according to the chilled water flow demand, the lower limit is the minimum safe operating frequency of the pump (to avoid cavitation), upper limit is the rated frequency | ||

| Cooling Water Pump | Number of Operating Cooling Water Pumps | Units | 1~5 | Must be adapted to the number of chillers in operation | |

| Operating Frequency of Cooling Water Pumps | Hz | 30.0~50.0 | Set according to the cooling water flow demand, the lower limit is the minimum safe operating frequency of the pump (to avoid cavitation), upper limit is the rated frequency |

| Item | Operating Condition 1 | Operating Condition 2 | Operating Condition 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Load (kW) | 11,592 | 22,702 | 34,059 |

| Load Percentage (%) | 30.9 | 60.6 | 90.9 |

| Dry-Bulb Temperature (°C) | 16.3 | 26.4 | 30.1 |

| Wet-Bulb Temperature (°C) | 14.8 | 24.0 | 26.4 |

| Condition | Parameter | Before Optimization | After Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Chiller Load Distribution (kW) | [4270.0, 7321.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | [3172.2, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 8419.8] |

| Case 2 | Chiller Load Distribution (kW) | [0.0, 7567.0, 7567.0, 7567.0, 0.0] | [2593.4, 0.0, 6798.2, 6757.3, 6553.1] |

| Case 3 | Chiller Load Distribution (kW) | [4334.0, 7431.0, 7431.0, 7431.0, 7431.0] | [2971.3, 7775.1, 7771.3, 7776.5, 7764.7] |

| Case 1 | Chilled Water Pump Frequency (Hz) | [48.2, 47.4, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | [30.4, 30.4, 0, 0, 0] |

| Case 2 | Chilled Water Pump Frequency (Hz) | [0.0, 48.0, 48.0, 48.0, 0.0] | [0, 36.4, 36.4, 36.4, 0] |

| Case 3 | Chilled Water Pump Frequency (Hz) | [50.0, 50.0, 50.0, 50.0, 50.0] | [42.9, 42.9, 42.9, 42.9, 42.0] |

| Case 1 | Cooling Water Pump Frequency (Hz) | [40.0, 40.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | [35.3, 35.3, 0, 0, 0] |

| Case 2 | Cooling Water Pump Frequency (Hz) | [0.0, 45.0, 45.0, 45.0, 0.0] | [41.1, 41.1, 41.1, 0, 0] |

| Case 3 | Cooling Water Pump Frequency (Hz) | [50.0, 50.0, 50.0, 50.0, 50.0] | [0, 43.5, 43.5, 43.5, 43.5] |

| Case 1 | Cooling Tower Flow Distribution (m3/h) | [452.0, 452.0, 452.0, 452.0, 452.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0] | [453.0, 453.0, 453.0, 453.0, 453.0, 0, 0, 0, 0] |

| Case 2 | Cooling Tower Flow Distribution (m3/h) | [495.0, 495.0, 495.0, 495.0, 495.0, 495.0, 495.0, 495.0, 495.0] | [494.0, 494.0, 494.0, 494.0, 494.0, 494.0, 494.0, 494.0, 494.0] |

| Case 3 | Cooling Tower Flow Distribution (m3/h) | [742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0] | [742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0, 742.0] |

| Case 1 | Approach Temperature (°C) | 4 | 3.5 |

| Case 2 | Approach Temperature (°C) | 4 | 2.5 |

| Case 3 | Approach Temperature (°C) | 4 | 3.54 |

| Case | Algorithm | Load (kW) | Wet-Bulb Temperature (°C) | Total Energy Consumption (kW) | EER | Computation Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 (Low Load) | GA | 11,592 | 14.8 | 1824 | 6.355 | 396.52 |

| PSO | 11,592 | 14.8 | 1824 | 6.355 | 170.61 | |

| WOA | 11,592 | 14.8 | 1823 | 6.356 | 120.41 | |

| Case 2 (Medium Load) | GA | 22,702 | 24.0 | 4380 | 5.183 | 458.10 |

| PSO | 22,702 | 24.0 | 4384 | 5.178 | 150.92 | |

| WOA | 22,702 | 24.0 | 4380 | 5.183 | 146.95 | |

| Case 3 (High Load) | GA | 34,059 | 26.4 | 7371 | 4.621 | 513.52 |

| PSO | 34,059 | 26.4 | 7371 | 4.621 | 437.16 | |

| WOA | 34,059 | 26.4 | 7371 | 4.621 | 408.23 |

| Algorithm | Success Rate (%) | Mean Energy (kW) | Std Energy (kW) | Min Energy (kW) | Max Energy (kW) | CV Energy (%) | Mean Time (s) | Std Time (s) | CV Time (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOA | 100 | 4762.7 | 2.17 | 4761 | 4770 | 0.046 | 248.92 | 78.46 | 31.52 |

| GA | 100 | 4761 | 0 | 4761 | 4761 | 0 | 386.71 | 112.31 | 29.04 |

| PSO | 100 | 4761.15 | 0.65 | 4761 | 4764 | 0.014 | 262.68 | 92.76 | 35.31 |

| Index | Parameter Type | Baseline Value | Range of Change | Step Size | Number of Experiment Groups | Control Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of Chillers | 4 units | 4 to 5 units | 1 unit | 2 | Number of cooling towers, number of pumps, pump frequency, and approach temperature |

| 2 | Number of Cooling Towers | 5 units | 5 to 9 units | 2 units | 3 | Number of chillers, number of pumps, pump frequency, approach temperature |

| 3 | Number of Pumps | 4 units | 4 to 5 units | 1 unit | 2 | Number of chillers, number of cooling towers, pump frequency, and approach temperature |

| 4 | Lower Limit of Pump Frequency | 70% | 70% to 100% | 5% | 7 | Number of chillers, number of cooling towers, number of pumps, approach temperature |

| 5 | Cooling Tower Approach Temperature | 4 °C | 2 to 6 °C | 1 °C | 5 | Number of chillers, number of cooling towers, number of pumps, pump frequency |

| Rank | Parameter Type | Parameter Range | Change in Total Energy Consumption (kW) | Change in EER | Sensitivity Coefficient | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of Pumps | 4 → 5 units | −53.0 | +0.04 | 1.1125 | High |

| 2 | Lower Limit of Pump Frequency | 70% → 100% | +340.0 | −0.31 | 0.1957 | Medium |

| 3 | Cooling Tower Approach Temperature | 2 → 6 °C | +208.5 | −0.20 | 0.0431 | Medium |

| 4 | Number of Chillers | 4 → 5 units | −35.0 | +0.04 | 0.0325 | Low |

| 5 | Number of Cooling Towers | 5 → 9 units | +6.2 | 0.00 | 0.0023 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Xu, A.; Guan, L.; Zhang, D. Optimization of Multi-Parameter Collaborative Operation for Central Air-Conditioning Cold Source System in Super High-Rise Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234363

Yang J, Xu A, Guan L, Zhang D. Optimization of Multi-Parameter Collaborative Operation for Central Air-Conditioning Cold Source System in Super High-Rise Buildings. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234363

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jiankun, Aiqin Xu, Lingjun Guan, and Dongliang Zhang. 2025. "Optimization of Multi-Parameter Collaborative Operation for Central Air-Conditioning Cold Source System in Super High-Rise Buildings" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234363

APA StyleYang, J., Xu, A., Guan, L., & Zhang, D. (2025). Optimization of Multi-Parameter Collaborative Operation for Central Air-Conditioning Cold Source System in Super High-Rise Buildings. Buildings, 15(23), 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234363