Experimental Investigation on the Dynamic Flexural Performance of High-Strength Rubber Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Raw Materials and Mix Proportions

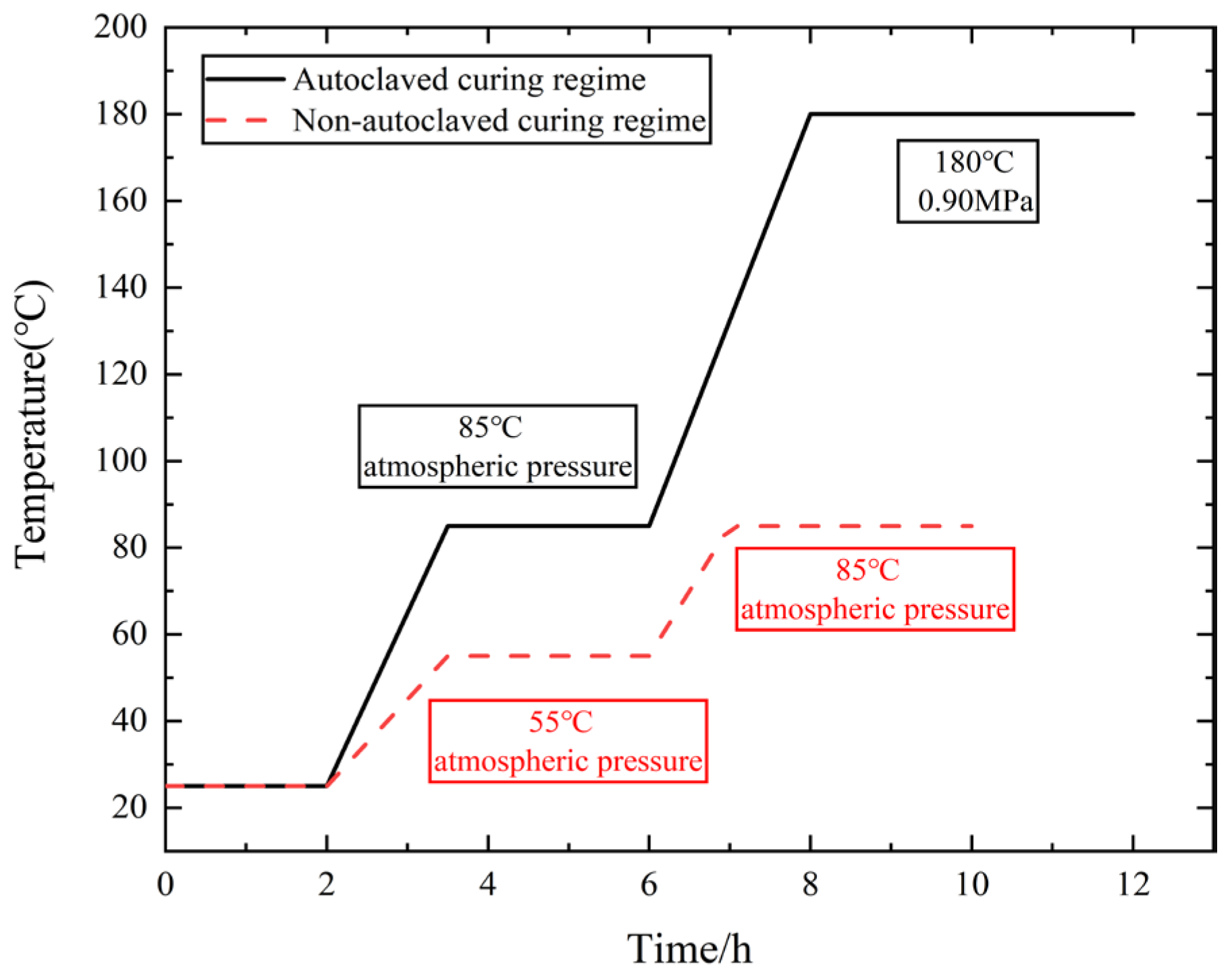

2.2. Experiment Preparation and Curing System

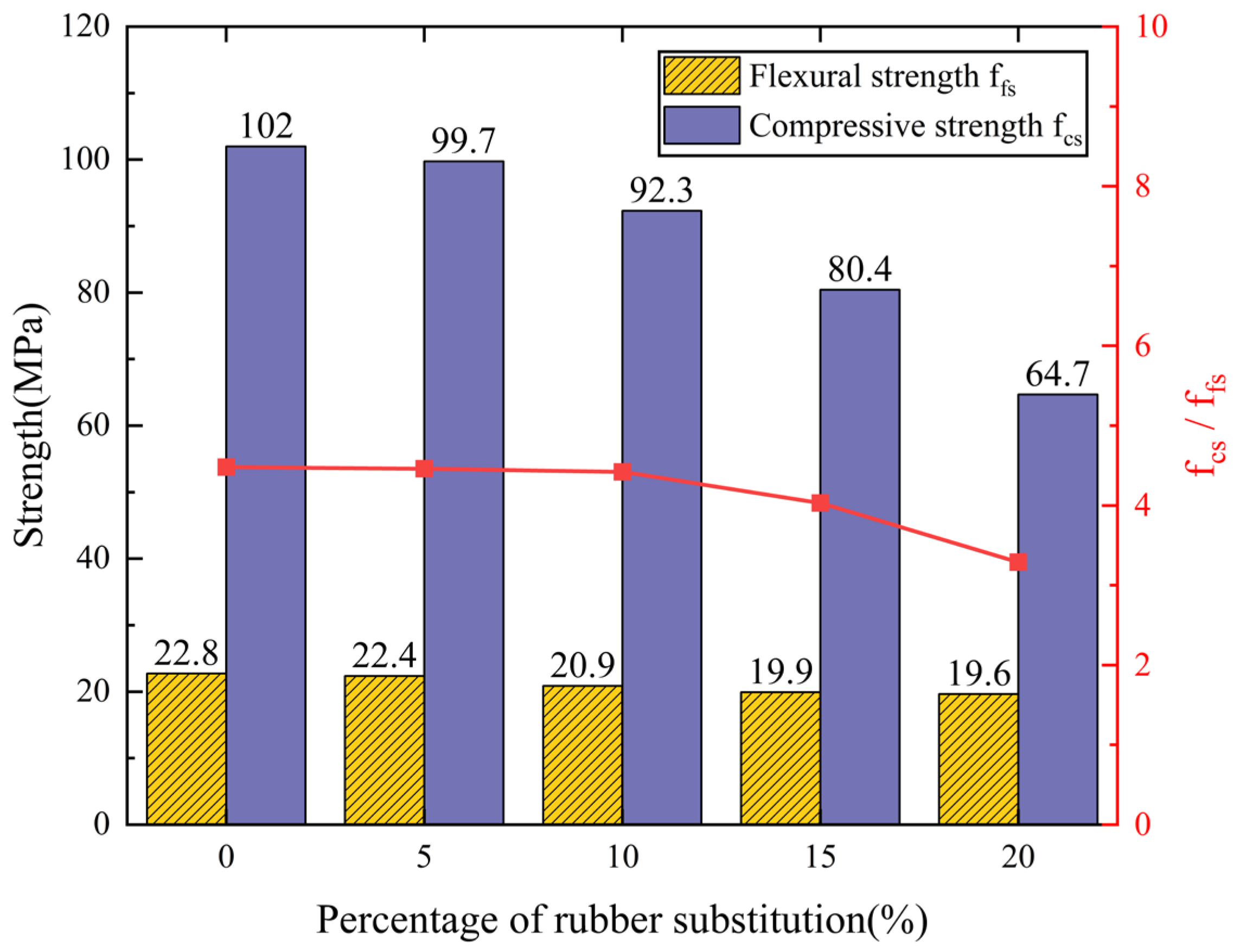

3. Quasi-Static Test

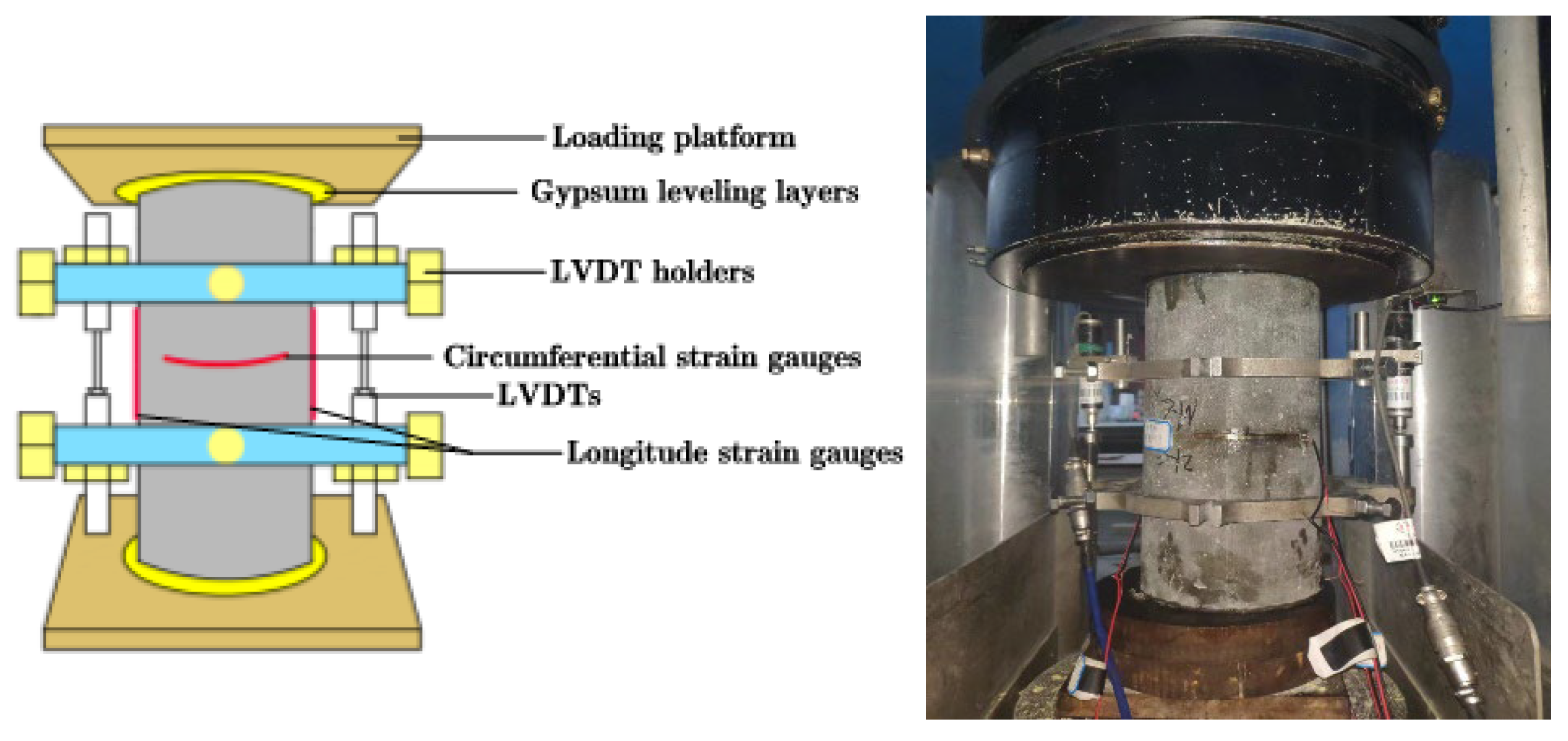

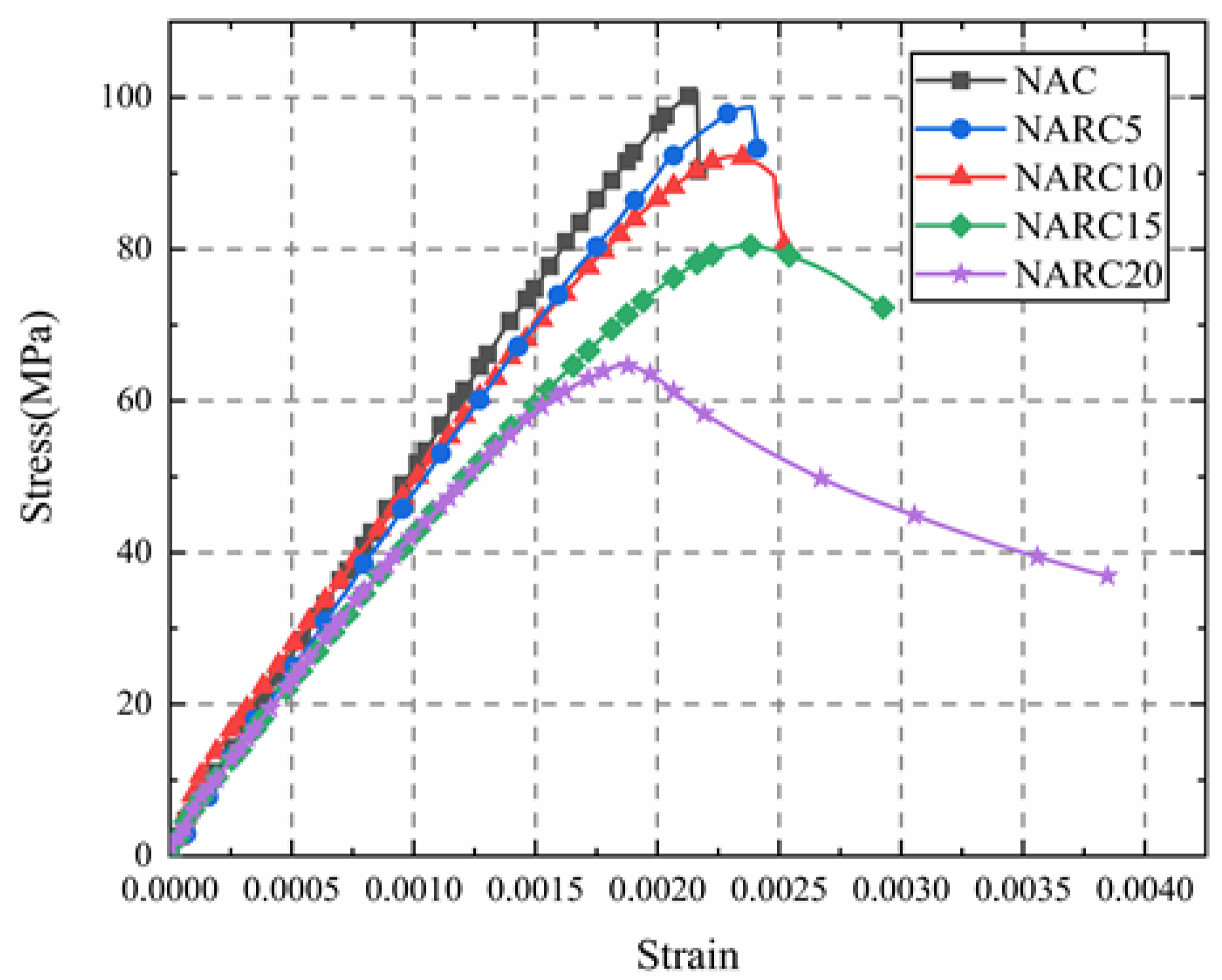

3.1. Compressive Performance

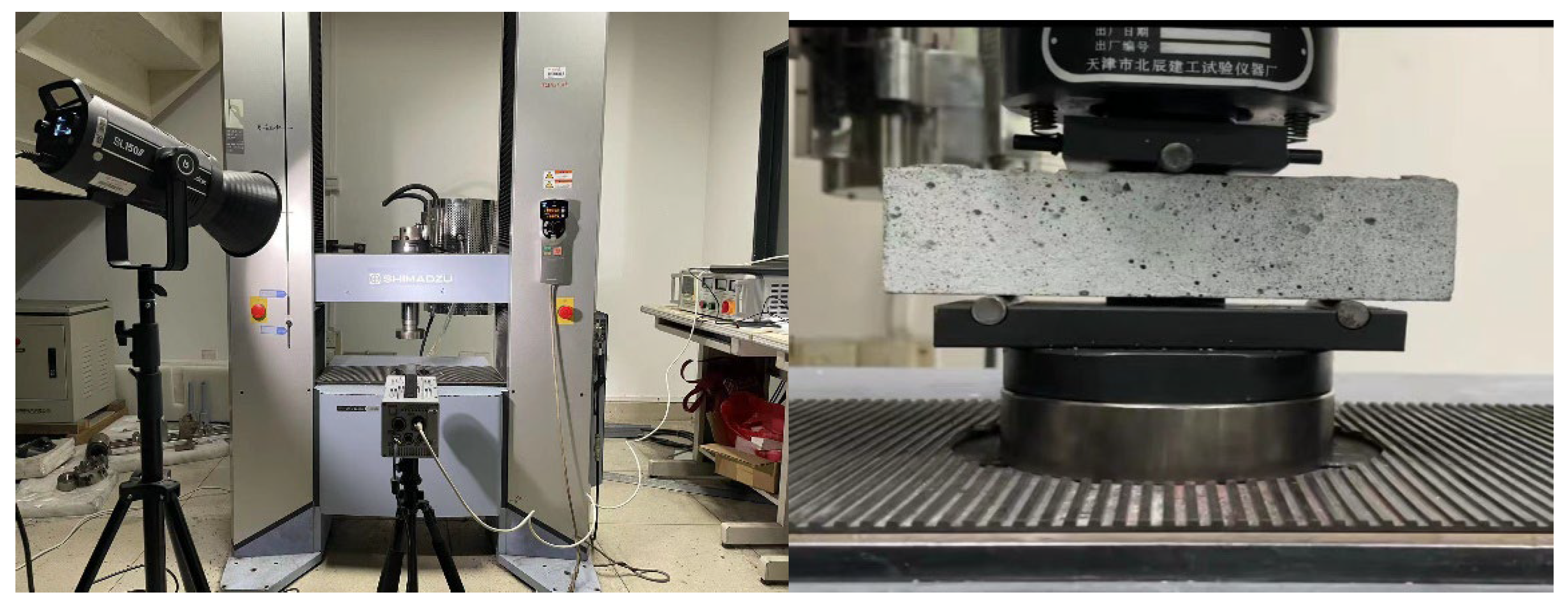

3.2. Flexural Performance

3.3. Quasi-Static Test Results and Discussion

3.3.1. Modulus of Elasticity

3.3.2. Quasi-Static Flexural Strength

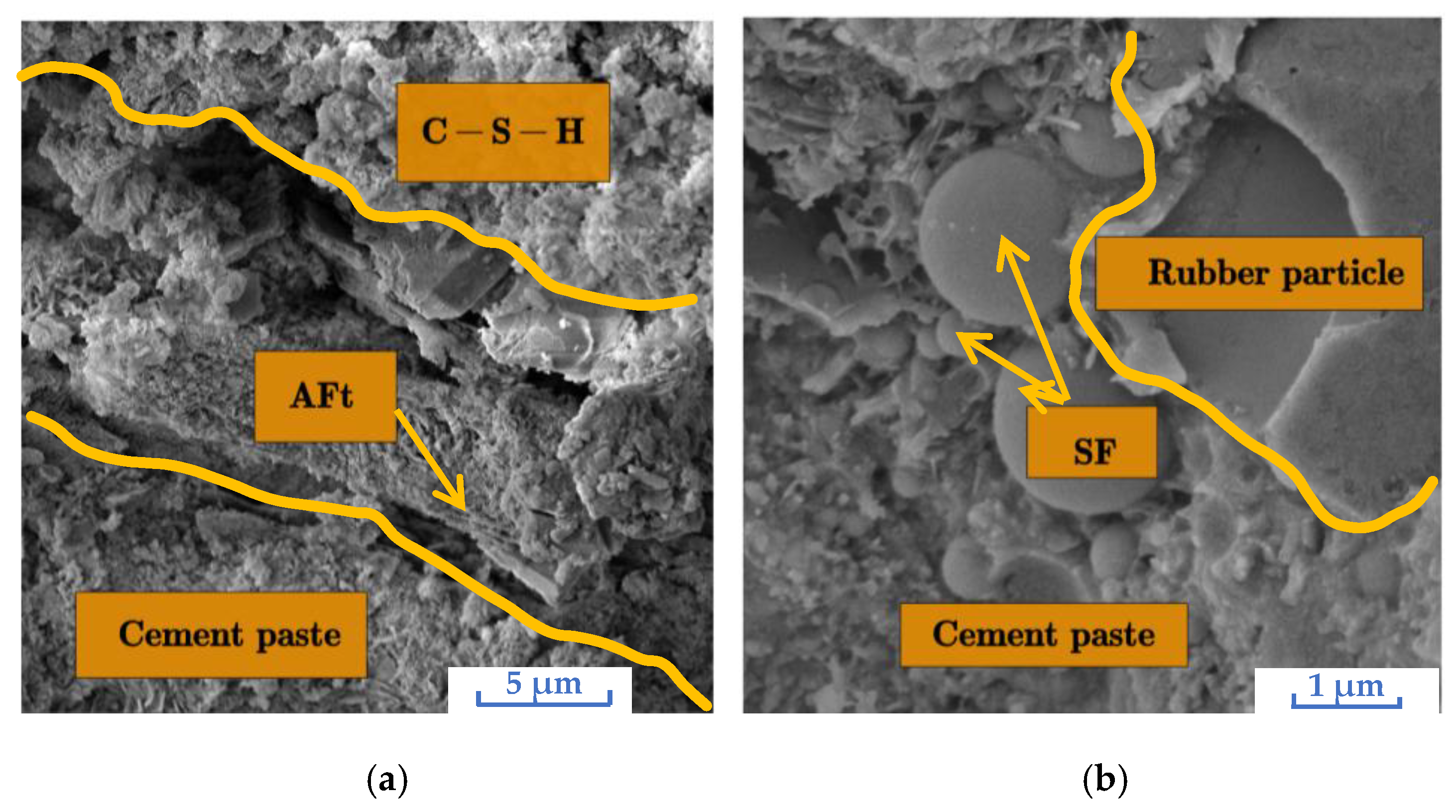

3.3.3. Microscopic Morphology of NARC

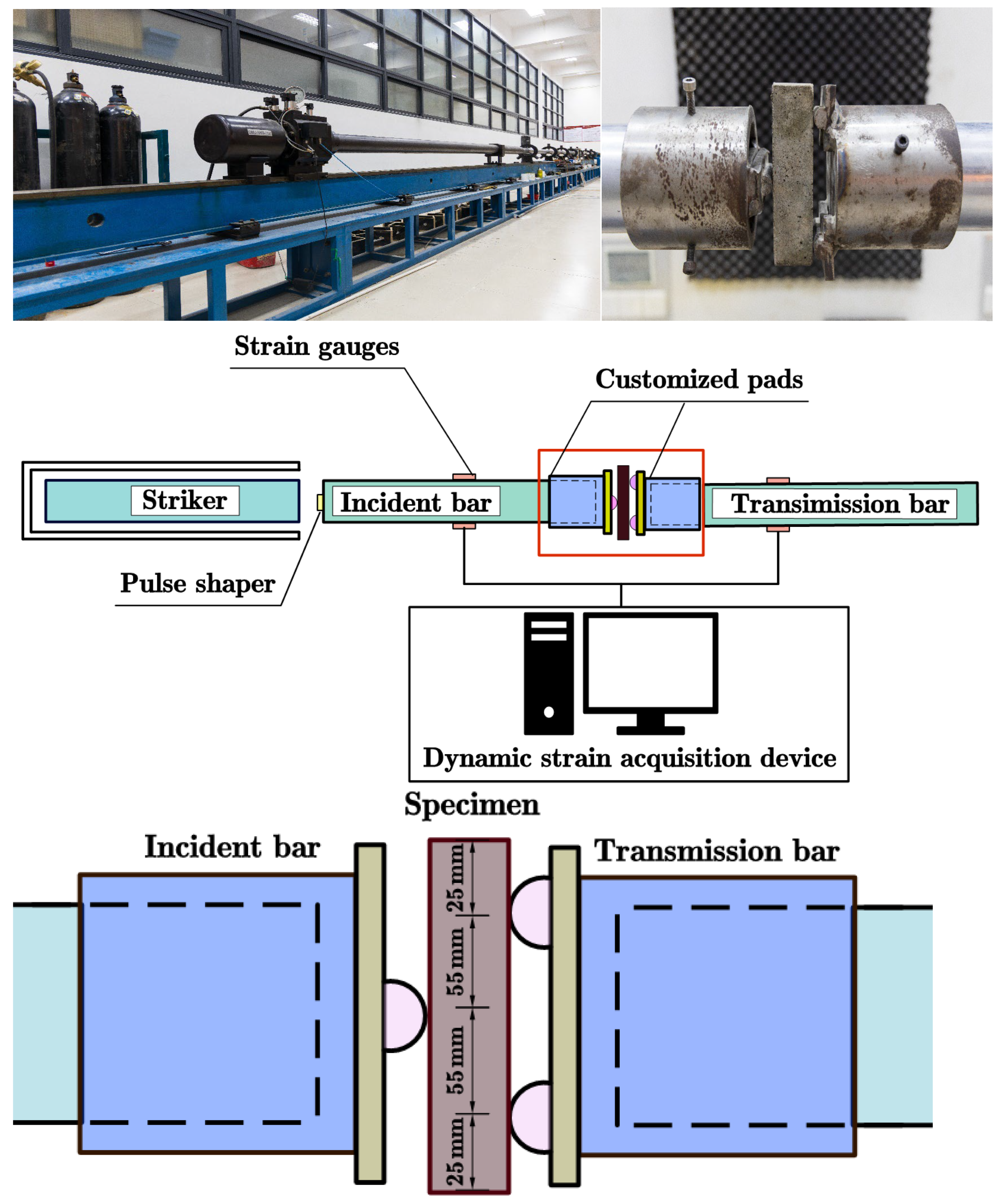

3.4. Dynamic Experimental Establishment

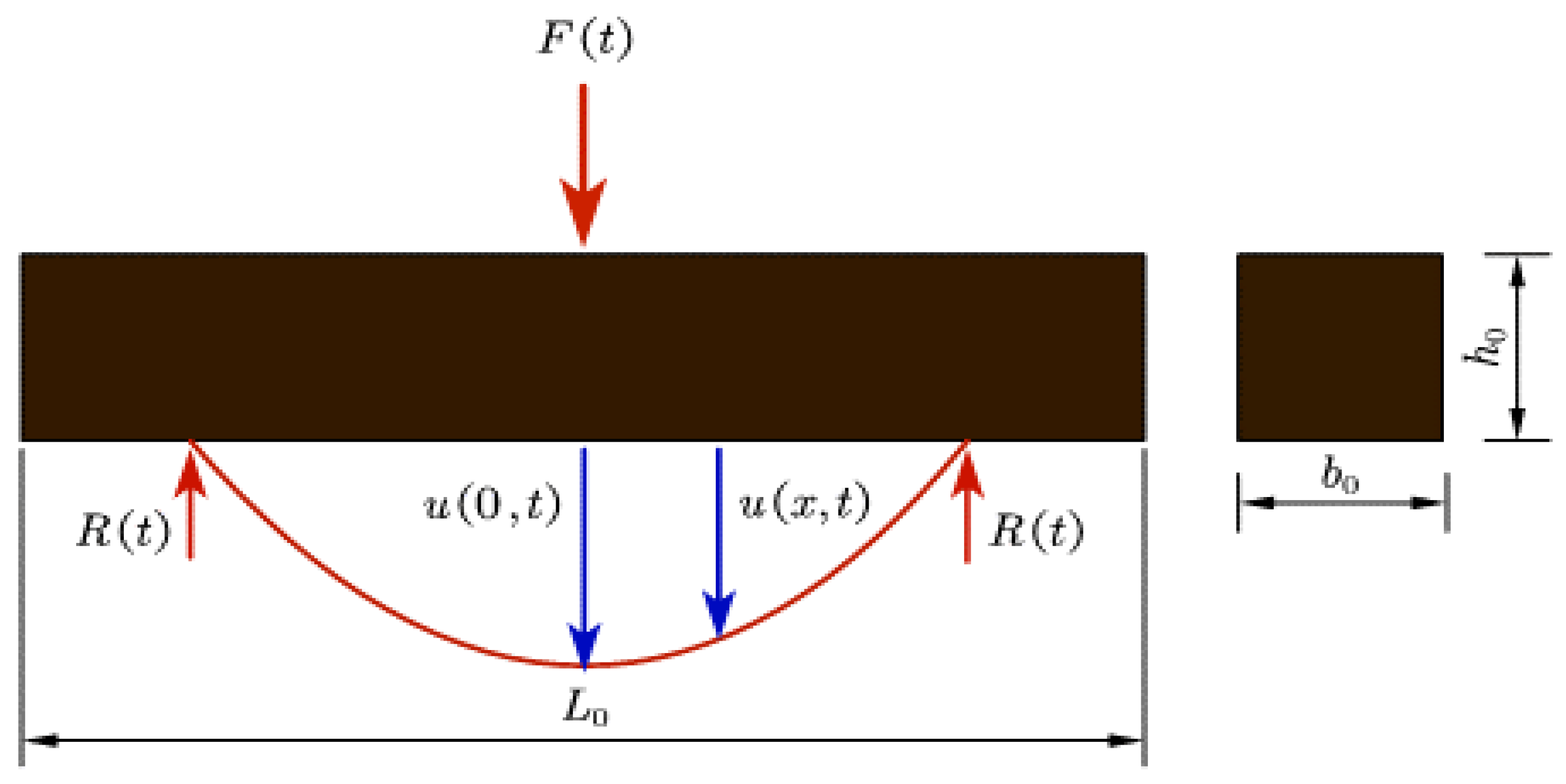

3.5. Theoretical Derivation of the Dynamicflexural Test

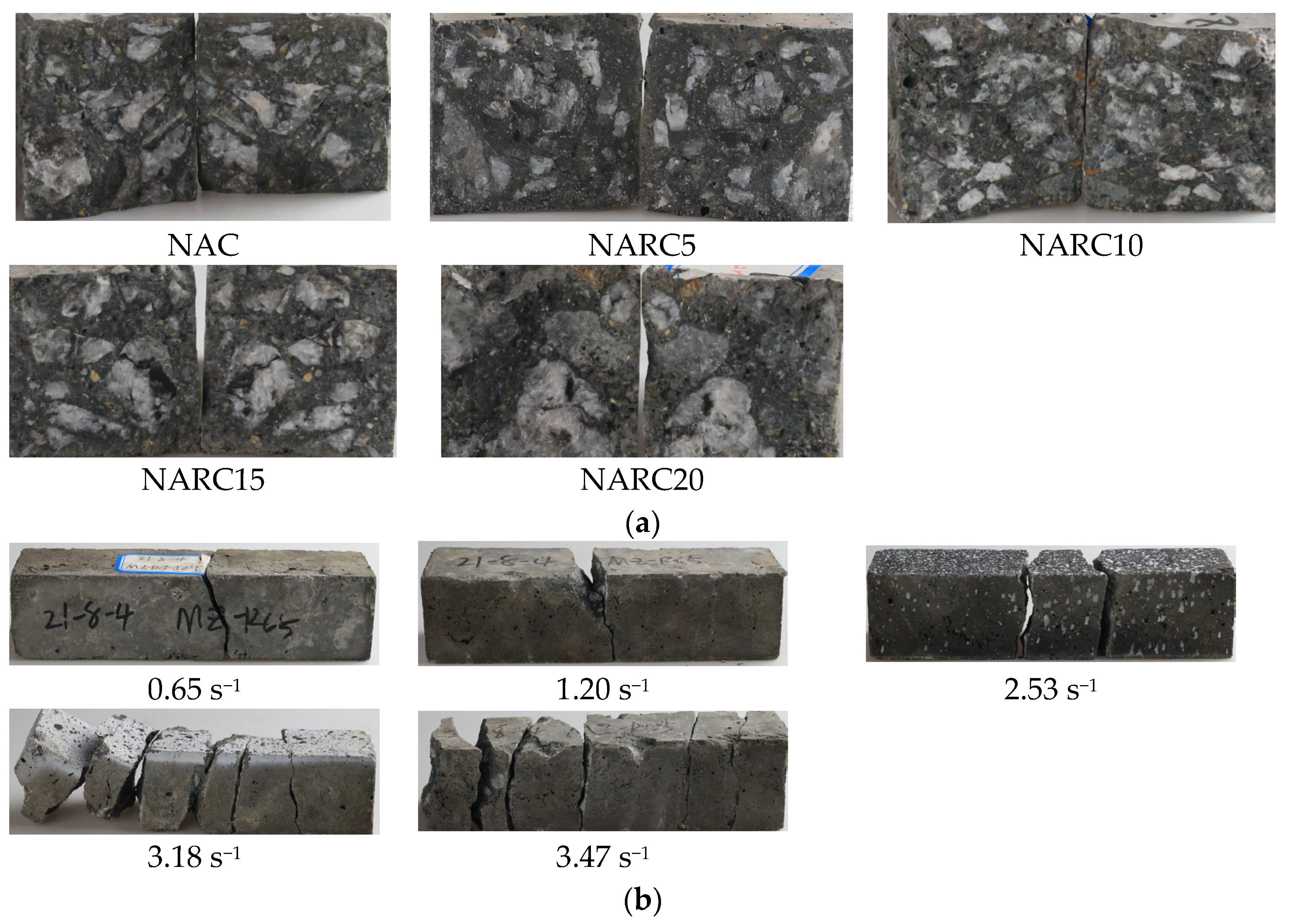

3.6. Failure Modes

3.7. Dynamic Experimental Results and Discussions

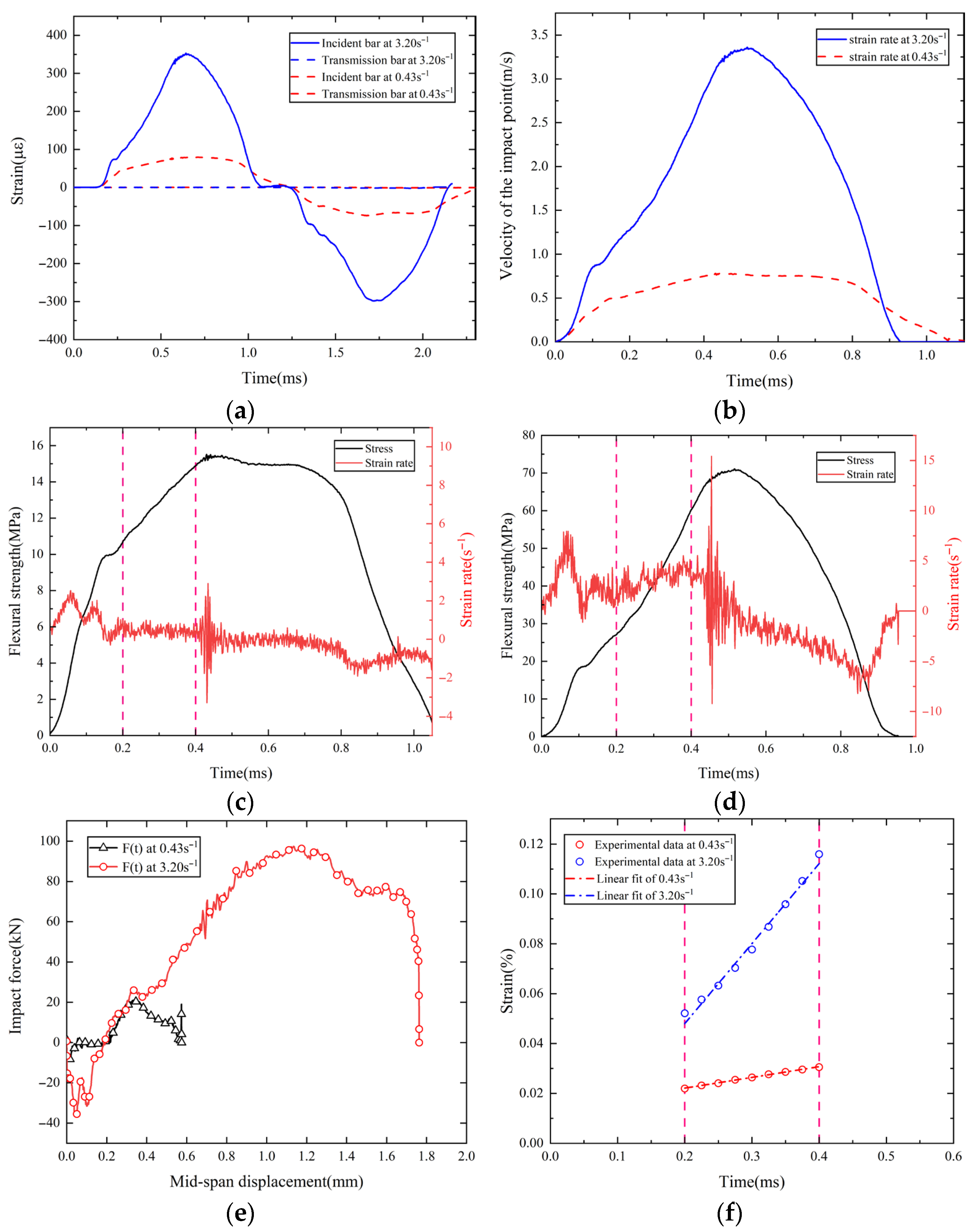

3.7.1. Example: Tests on NARC at Strain Rate of 0.43 s−1 and 3.20 s−1

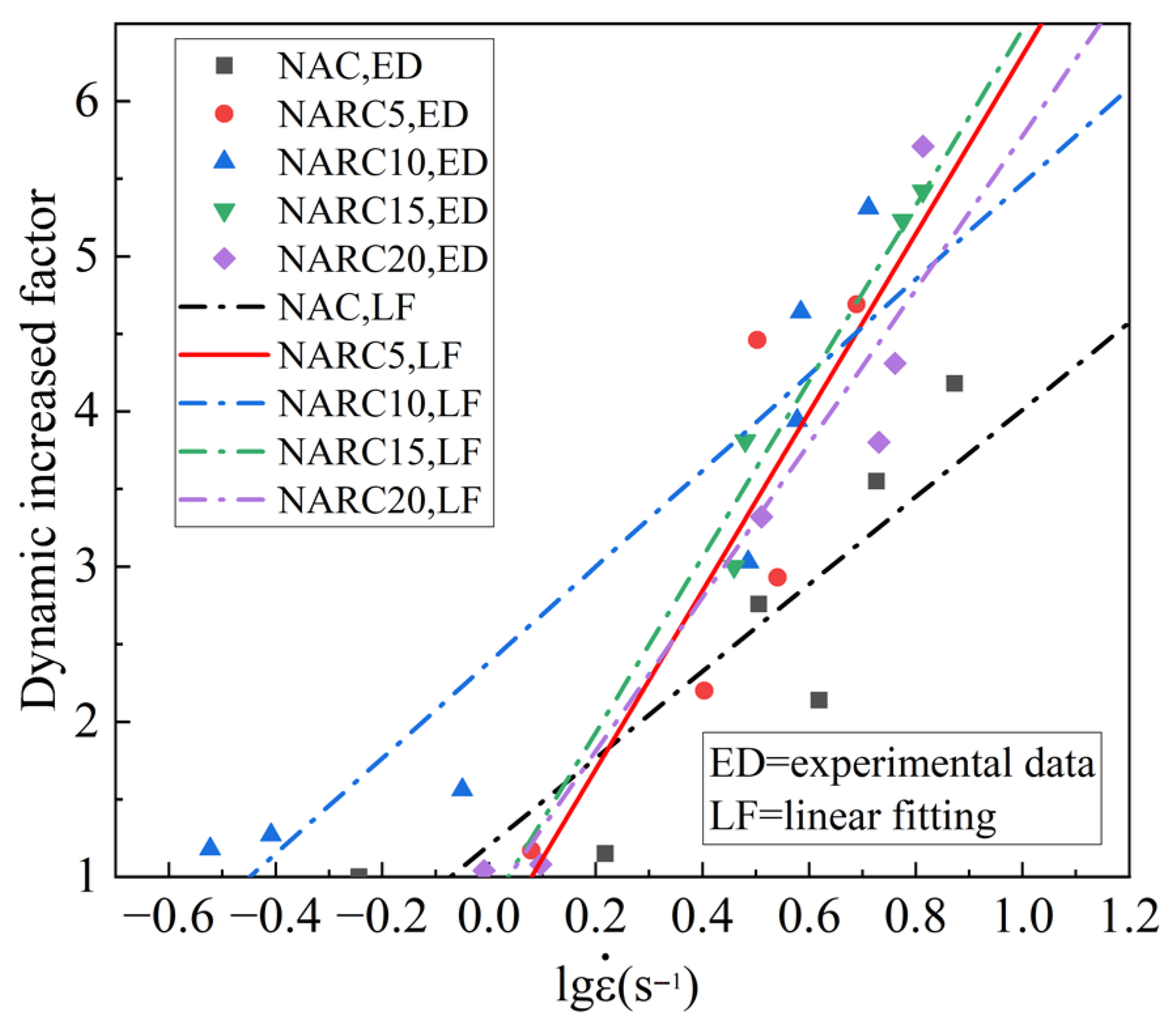

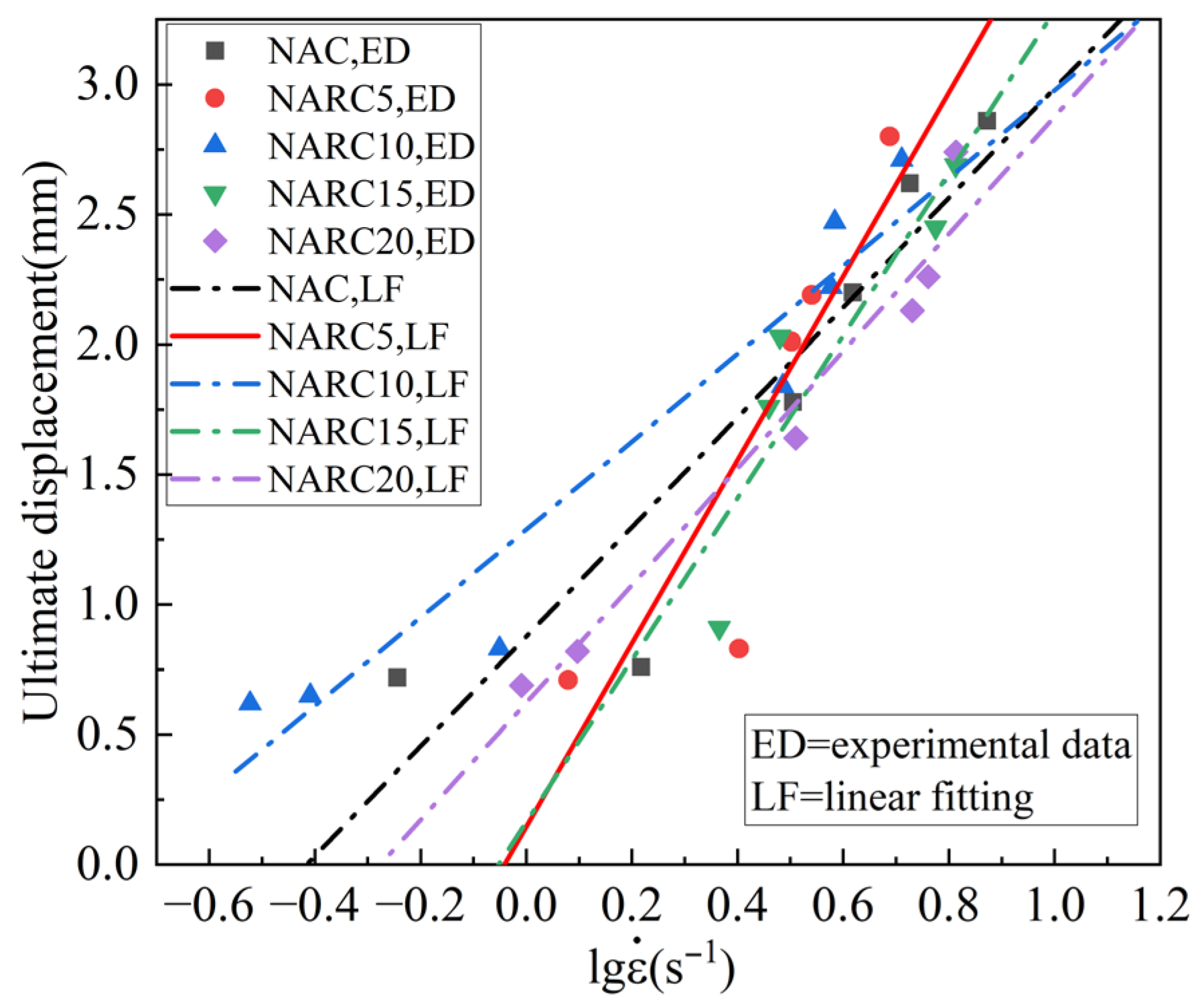

3.7.2. Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- NARC has achieved environmental benefits without compromising performance. Non-autoclaved curing reduces carbon emissions by approximately 20% compared to steam curing. Coal-based curing decreases from 447.54 kg/m3 to 354.72 kg/m3. Quasi-static testing indicates that NARC5 exhibits a flexural strength of 22.35 MPa, comparable to ordinary concrete (22.75 MPa). However, the brittleness ratio (compressive strength/flexural strength) decreased from 4.48 to 4.46, demonstrating enhanced toughness.

- (2)

- Although rubber particles can reduce the fragility of NARC as a flexible material, they significantly decrease the strength of NARC and are not suitable for the excessive addition of rubber particles. As the rubber content increased from 0% to 20%, the dynamic flexural strength decreased significantly. The weak interfacial adhesion between rubber particles and the cement matrix acts as a microcrack nucleus, leading to reduced strength. For example, at a strain rate of 7.45 s−1, the dynamic flexural strength of NAC (0% rubber) was 139.50 MPa, while that of NARC20 (20% rubber) decreased to 74.72 MPa.

- (3)

- Rubber particles dissipate impact energy, synergistically improving flexural strength and ultimate deformation. At a rubber replacement rate of 5%, the impact of strain rate on DIF becomes more pronounced, and the strain rate effect is also evident in the mid-span displacement during flexural tests. The mechanism is that at high strain rates, the large impact energy causes coarse aggregates to fracture rather than being bypassed, thereby enhancing flexural strength. As a flexible material, rubber particles positively enhance the NARC’s ultimate deformation capacity by dissipating part of the impact energy. At appropriate rubber content levels, they can improve the strain rate sensitivity of strength on NARC.

- (4)

- Future research should focus on optimizing rubber–cement interfacial bonding to enable higher rubber content without strength loss and investigating NARC’s impact resistance under harsh environments (e.g., fires, oceans, and cold regions).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeyad, A.M.; Johari, M.A.M.; Alharbi, Y.R.; Abadel, A.A.; Amran, Y.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Abutaleb, A. Influence of steam curing regimes on the properties of ultrafine POFA-based high-strength green concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.E.; Aliu, J. Strategies for the implementation of environmental economic practices for sustainable construction in a developing economy. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2025, 25, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.; Nazir, S.; Nguyen, T.-H.; Ho, N.-K.; Dinh, T.-H.; Nguyen, V.-P.; Nguyen, M.-H.; Phan, Q.-K.; Kieu, T.-S. Empirical Examination of Factors Influencing the Adoption of Green Building Technologies: The Perspective of Construction Developers in Developing Economies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Paul, B.; Sarkar, B. Revolutionizing sustainable construction through predictive modeling of green concrete. Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 23, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M.; Mahmoudi, M.M.; Rooholamini, H.; Motlagh, N.M. A hybrid fuzzy multi-criteria sustainability framework for incorporating recycled tire waste into green concrete technologies: Large scale applications of retaining walls and pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 500, 144126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, B.; Zhou, F.; Shen, S.; Guo, A.; Xie, Y. Effect of steam curing regimes on temperature and humidity gradient, permeability and microstructure of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 281, 122562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Shao, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Xiong, C. Evolution of temperature stress and tensile properties of concrete during steam-curing process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wei, W.; Liu, F.; Cui, C.; Li, L.; Zou, R.; Zeng, Y. Bond behaviour of recycled aggregate concrete with basalt fibre-reinforced polymer bars. Compos. Struct. 2021, 256, 113078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, Z.; Nong, Y.; Guan, S.; Sun, J. Fracture behavior of a sustainable material: Recycled concrete with waste crumb rubber subjected to elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Tayeh, B.A.; Namdar, A. Fracture characteristics of sustainable crumb rubber concrete under a wide range of loading rates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, H.; Isleem, H.F.; Tayeh, B.A.; Namdar, A. Mechanical behavior and constitutive model of sustainable concrete: Seawater and sea-sand recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 364, 130010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wei, W.; He, S.; Liu, F.; Luo, H.; Li, L. Dynamic bond behaviour of fibre-wrapped basalt fibre-reinforced polymer bars embedded in sea sand and recycled aggregate concrete under high-strain rate pull-out tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 276, 122195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, G.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Xiong, Z.; Liang, J.; Zou, X.; Qiu, Y.; Qiao, S.; Liang, D.; Liu, F. Fatigue performance of basalt fibre-reinforced polymer bar-reinforced sea sand concrete slabs. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 706–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J. Inner blast response of fiber reinforced aluminum tubes. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 172, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J. Novel visual crack width measurement based on backbone double-scale features for improved detection automation. Eng. Struct. 2023, 274, 115158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qi, X.; Li, C.; Gao, P.; Wang, Z.; Ying, J. Seismic behaviour of seawater coral aggregate concrete columns reinforced with epoxy-coated bars. Structures 2022, 36, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Mai, G.; Qiao, S.; He, S.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Zhou, K.; Li, L. Fatigue bond behaviour between basalt fibre-reinforced polymer bars and seawater sea-sand concrete. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 218, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, L.; Xiao, J.; Zuo, J.; Wu, H. Effects of eco powders from solid waste on freeze-thaw resistance of mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 333, 127405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Research and Application of Non-autoclaved PHC Pipe Pile Concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 688, 033065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Yang, Y.B.; Wu, X.H.; Xie, Y.H.; Luo, J.; Guo, W.Y.; Hao, Y.H.; Wang, H.C. Experimental Study on Non-Autoclaved PHC Pile Concrete Applying Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 629–630, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, N.; Asce, M.F.; Manzur, T. Effect of Steam Curing on Concrete Piles with Silica Fume. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2010, 4, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Yue, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, K. Effects of nano-SiO2 and secondary water curing on the carbonation and chloride resistance of autoclaved concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyad, A.M.; Azmi Megat Johari, M.; Abutaleb, A.; Tayeh, B.A. The effect of steam curing regimes on the chloride resistance and pore size of high–strength green concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Feng, W.; Xiong, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Lin, H.; Shen, Y. Impact performance of new prestressed high-performance concrete pipe piles manufactured with an environmentally friendly technique. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Fu, H.; Zuo, W.; Luo, S.; Zhao, H.; Feng, P.; Wang, H. Effect of n-C-S-H-PCE and slag powder on the autogenous shrinkage of high-strength steam-free pipe pile concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Bu, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, G. Durability and microstructure of steam cured and autoclaved PHC pipe piles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 209, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, A.; El-Feky, M.S.; Nasr, E.-S.A.R.; Kohail, M. Performance of high strength concrete containing recycled rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Siddique, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Chaudhary, S. Effect of aggressive environment on durability of concrete containing fibrous rubber shreds and silica fume. Struct. Concr. 2021, 22, 2611–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, G.; Li, L.; Guo, Y. Study of impact performance of rubber reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.S.; Chandra Gupta, R. Properties of high strength concrete containing scrap tire rubber. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atahan, A.O.; Yücel, A.Ö. Crumb rubber in concrete: Static and dynamic evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, F.; Yang, F.; Li, L.; Jing, L.; Chen, B.; Yuan, B. Experimental study on the effect of strain rates on the dynamic flexural properties of rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, F.; Yang, F.; Li, L.; Jing, L. Experimental study on dynamic split tensile properties of rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C469; Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM C39; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM C293; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Center-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Liu, F.; Feng, W.; Xiong, Z.; Tu, G.; Li, L. Static and impact behaviour of recycled aggregate concrete under daily temperature variations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Tao, W.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huan, S. A modified method of pulse-shaper technique applied in SHPB. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 165, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolsky, H. An Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of Materials at very High Rates of Loading. Proc. Phys. Soc. B 1949, 62, 676–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchau, O.A.; Craig, J.I. Euler-Bernoulli beam theory. In Structural Analysis; Spinger: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvare, F.; Hanus, J.L.; Bailly, P. A non-equilibrium approach to processing Hopkinson Bar bending test data: Application to quasi-brittle materials. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2010, 37, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanus, J.-L.; Magnain, B.; Durand, B.; Alanis-Rodriguez, J.; Bailly, P. Processing dynamic split Hopkinson three-point bending test with normalized specimen of quasi-brittle material. Mech. Ind. 2012, 13, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Lin, G. Dynamic properties of concrete in direct tension. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Shao, Y. Dynamic flexural strength of concrete under high strain rates. Mag. Concr. Res. 2017, 69, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yuan, B.; Yang, F.; Chen, L.; Feng, W.; Liang, Y. Dynamic three-point flexural performance of unsaturated polyester polymer concrete at different curing ages. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.B.; Gao, G.F.; Jing, L.; Shim, V.P.W. Response of high-strength concrete to dynamic compressive loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 108, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mixture | NAC | NARC5 | NARC10 | NARC15 | NARC20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/C | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Cement | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| Sand | 740 | 704 | 669 | 644 | 599 |

| Coarse aggregate | 1280 | 1280 | 1280 | 1280 | 1280 |

| Water-reducer | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Water | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 |

| Mineral powder | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 |

| Rubber particle | 0 | 9.04 | 18.08 | 27.12 | 36.16 |

| Slump (mm) | 38 | 50 | 38 | 28 | 20 |

| Emission Type | Autoclaved Curing (kg/m3) | Non-Autoclaved Curing (kg/m3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | Natural Gas | Coal | Natural Gas | |

| C1 | 345.86 | 345.86 | 307.76 | 307.76 |

| C2 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| C3 | 81.61 | - | 32.89 | - |

| C4 | - | 43.85 | - | 17.67 |

| C5 | 19.66 | - | 19.66 | - |

| Total | 447.54 | 409.78 | 354.72 | 339.50 |

| Specimen | Elastic Modulus E0, (GPa) | Compressive Strength fcs, (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio v |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | 50.90 ± 1.12 | 101.97 ± 5.42 | 0.22 |

| NARC5 | 48.78 ± 2.23 | 99.74 ± 2.23 | 0.19 |

| NARC10 | 45.82 ± 1.65 | 92.30 ± 1.53 | 0.17 |

| NARC15 | 41.72 ± 2.36 | 80.42 ± 8.35 | 0.17 |

| NARC20 | 38.08 ± 2.71 | 64.69 ± 7.36 | 0.16 |

| Specimen | Flexural Strength, ffs (MPa) | fcs/ffs |

|---|---|---|

| NAC | 22.75 ± 1.25 | 4.48 |

| NARC5 | 22.35 ± 1.54 | 4.46 |

| NARC10 | 20.86 ± 1.58 | 4.42 |

| NARC15 | 19.93 ± 1.68 | 4.03 |

| NARC20 | 19.64 ± 2.04 | 3.29 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Incident bar length | 5500 mm |

| Striker length | 1000 mm |

| Transmission bar length | 3500 mm |

| Bars diameter, Db | 100 mm |

| Bars young’s modulus, Eb | 5169 m/s |

| Velocity of elastic wave, Cb | 206 GPa |

| Specimen | Quasi-Static Flexural Strength | Strain Rate (s−1) | Dynamic Flexural Strength (MPa) | DIF | Displacement (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAC-1 | 22.75 | 0.57 | 22.55 | 1.00 | 0.72 |

| NAC-2 | 1.65 | 23.85 | 1.15 | 0.76 | |

| NAC-3 | 3.20 | 75.55 | 2.76 | 1.78 | |

| NAC-4 | 4.15 | 95.32 | 2.14 | 2.20 | |

| NAC-5 | 5.32 | 119.83 | 3.55 | 2.62 | |

| NAC-6 | 7.45 | 139.50 | 4.18 | 2.86 | |

| NARC5-1 | 22.35 | 1.20 | 26.16 | 1.17 | 0.71 |

| NARC5-2 | 2.53 | 32.91 | 2.20 | 0.83 | |

| NARC5-3 | 3.47 | 91.80 | 2.93 | 2.19 | |

| NARC5-4 | 3.18 | 78.15 | 4.46 | 2.01 | |

| NARC5-5 | 4.88 | 130.18 | 4.69 | 2.80 | |

| NARC10-1 | 20.86 | 0.30 | 26.95 | 1.18 | 0.62 |

| NARC10-2 | 0.39 | 29.01 | 1.27 | 0.65 | |

| NARC10-3 | 0.89 | 35.52 | 1.56 | 0.83 | |

| NARC10-4 | 3.06 | 69.05 | 3.03 | 1.84 | |

| NARC10-5 | 3.78 | 89.71 | 3.94 | 2.22 | |

| NARC10-6 | 3.84 | 105.56 | 4.64 | 2.47 | |

| NARC10-7 | 5.14 | 120.93 | 5.31 | 2.71 | |

| NARC15-1 | 19.93 | 2.32 | 29.68 | 1.49 | 0.91 |

| NARC15-2 | 2.88 | 59.84 | 3.00 | 1.76 | |

| NARC15-3 | 3.02 | 76.01 | 3.81 | 2.03 | |

| NARC15-4 | 6.50 | 108.02 | 5.42 | 2.69 | |

| NARC15-5 | 5.96 | 102.78 | 5.23 | 2.45 | |

| NARC20-1 | 19.64 | 1.25 | 21.26 | 1.08 | 0.82 |

| NARC20-2 | 0.98 | 20.47 | 1.04 | 0.69 | |

| NARC20-3 | 3.24 | 65.24 | 3.32 | 1.64 | |

| NARC20-4 | 5.38 | 74.72 | 3.80 | 2.13 | |

| NARC20-5 | 5.77 | 84.63 | 4.31 | 2.26 | |

| NARC20-6 | 6.51 | 112.12 | 5.71 | 2.74 |

| Specimen | a | b | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | 2.81 | 1.20 | 0.79 |

| NARC5 | 5.76 | 0.54 | 0.77 |

| NARC10 | 3.09 | 2.38 | 0.88 |

| NARC15 | 5.67 | 0.80 | 0.98 |

| NARC20 | 4.96 | 0.81 | 0.92 |

| Specimen | η | λ | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | 2.11 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| NARC5 | 3.53 | 0.15 | 0.79 |

| NARC10 | 1.69 | 1.29 | 0.93 |

| NARC15 | 3.12 | 0.16 | 0.83 |

| NARC20 | 2.25 | 0.62 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wen, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, D.; Feng, W.; Lan, S. Experimental Investigation on the Dynamic Flexural Performance of High-Strength Rubber Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234377

Wen J, Yang F, Chen D, Feng W, Lan S. Experimental Investigation on the Dynamic Flexural Performance of High-Strength Rubber Concrete. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234377

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Jiahao, Fei Yang, Dawei Chen, Wanhui Feng, and Sheng Lan. 2025. "Experimental Investigation on the Dynamic Flexural Performance of High-Strength Rubber Concrete" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234377

APA StyleWen, J., Yang, F., Chen, D., Feng, W., & Lan, S. (2025). Experimental Investigation on the Dynamic Flexural Performance of High-Strength Rubber Concrete. Buildings, 15(23), 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234377