Prediction of Excavation-Induced Displacement Using Interpretable and SSA-Enhanced XGBoost Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Description and Analysis

2.2. Machine Learning Methods

2.2.1. Machine Learning Model

2.2.2. SSA Optimization Algorithm

2.2.3. SHAP-Based Explainable Analysis of Machine Learning Model Performance Evaluation

2.2.4. Performance Evaluation of Machine Learning Models

2.3. Data Partitioning and Modeling Workflow

2.3.1. Data Partitioning

2.3.2. Modeling Workflow

3. Results

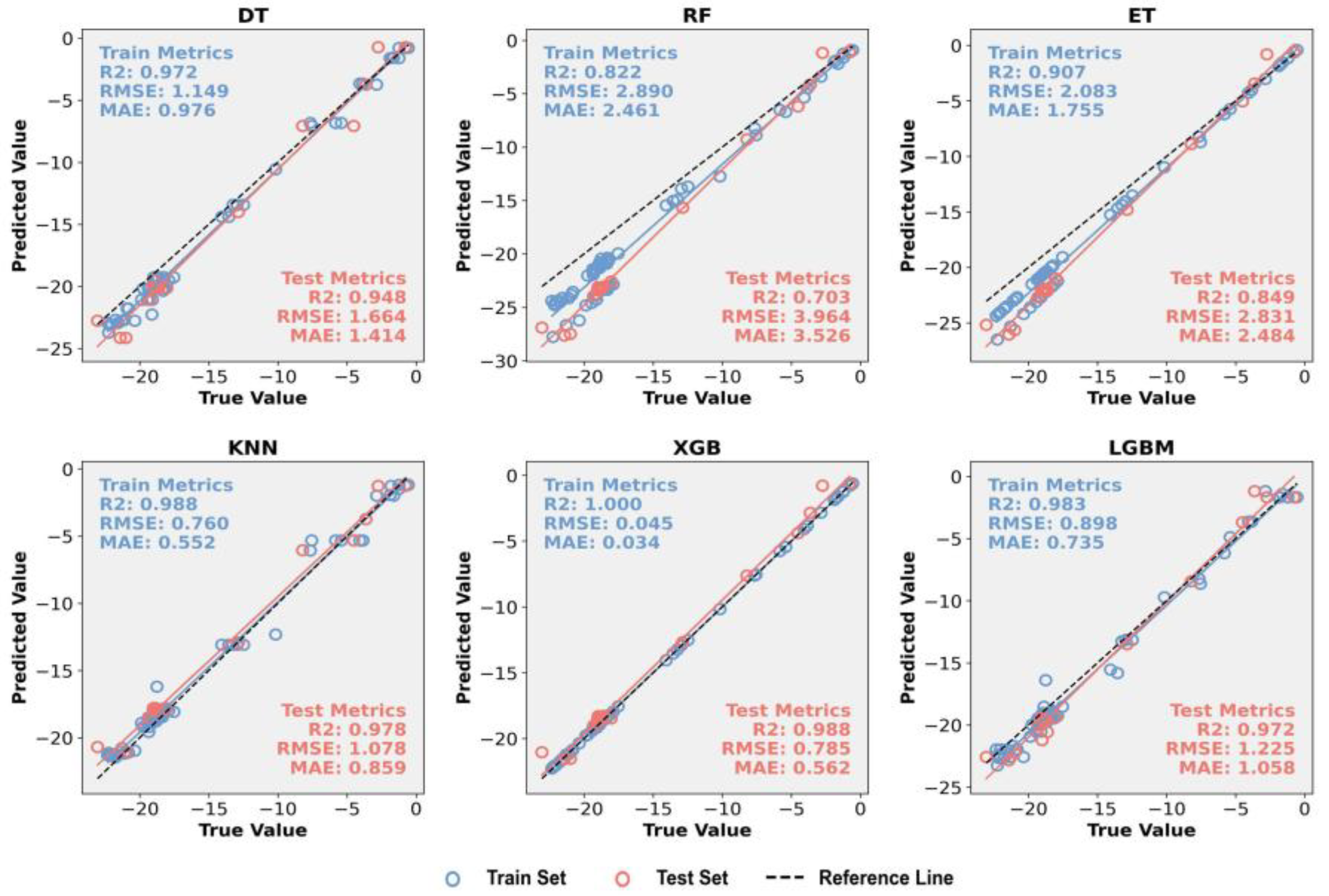

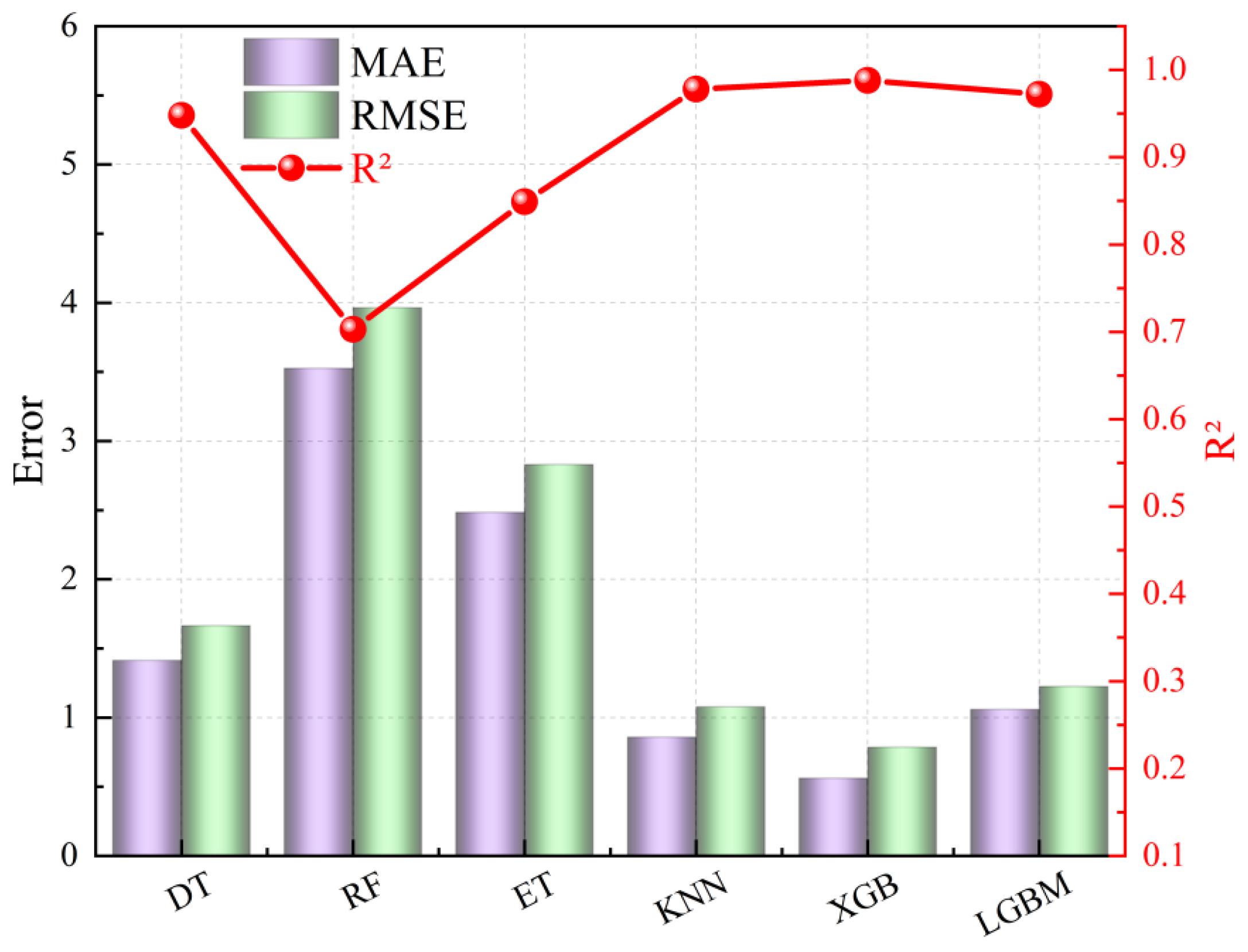

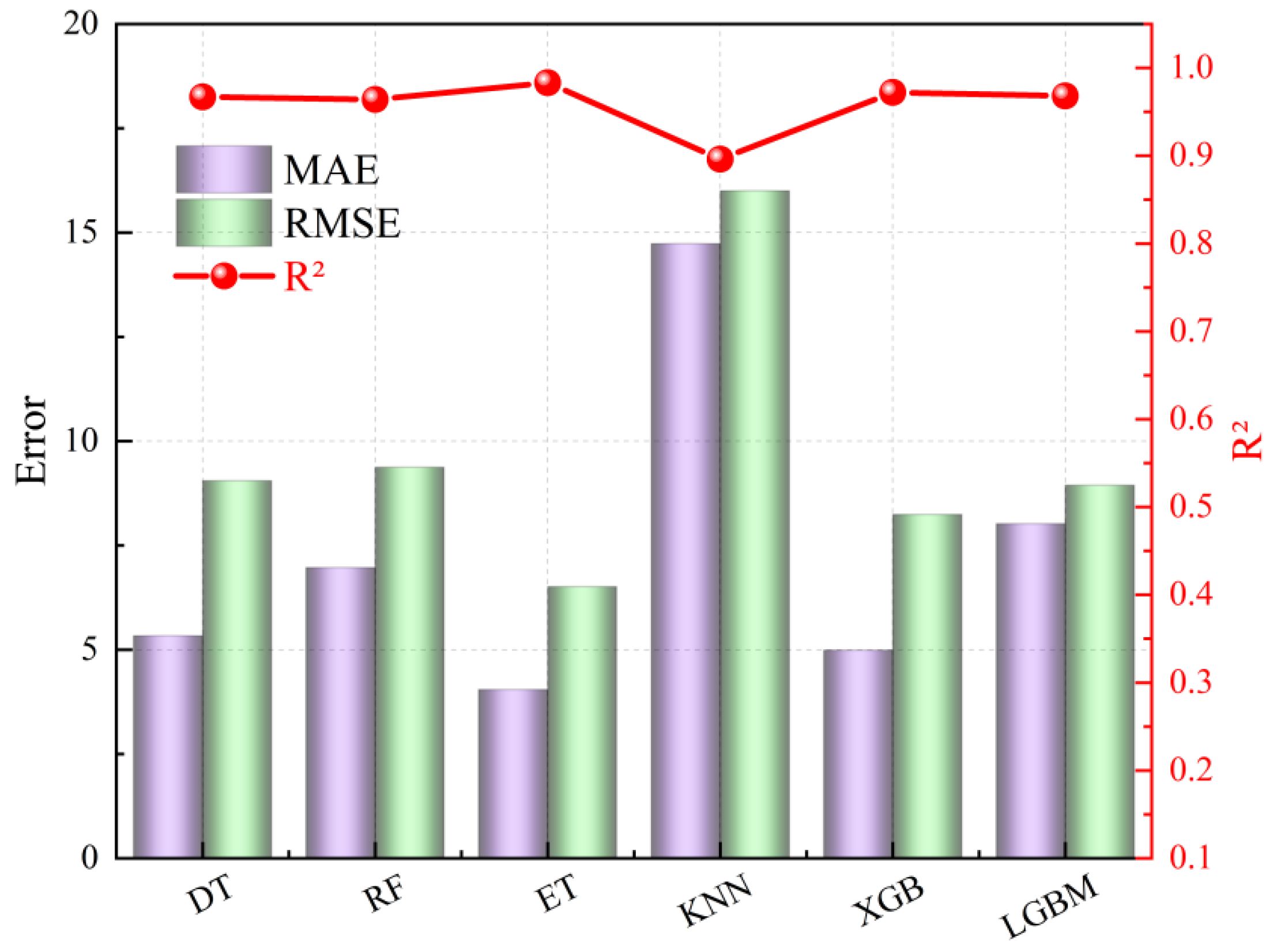

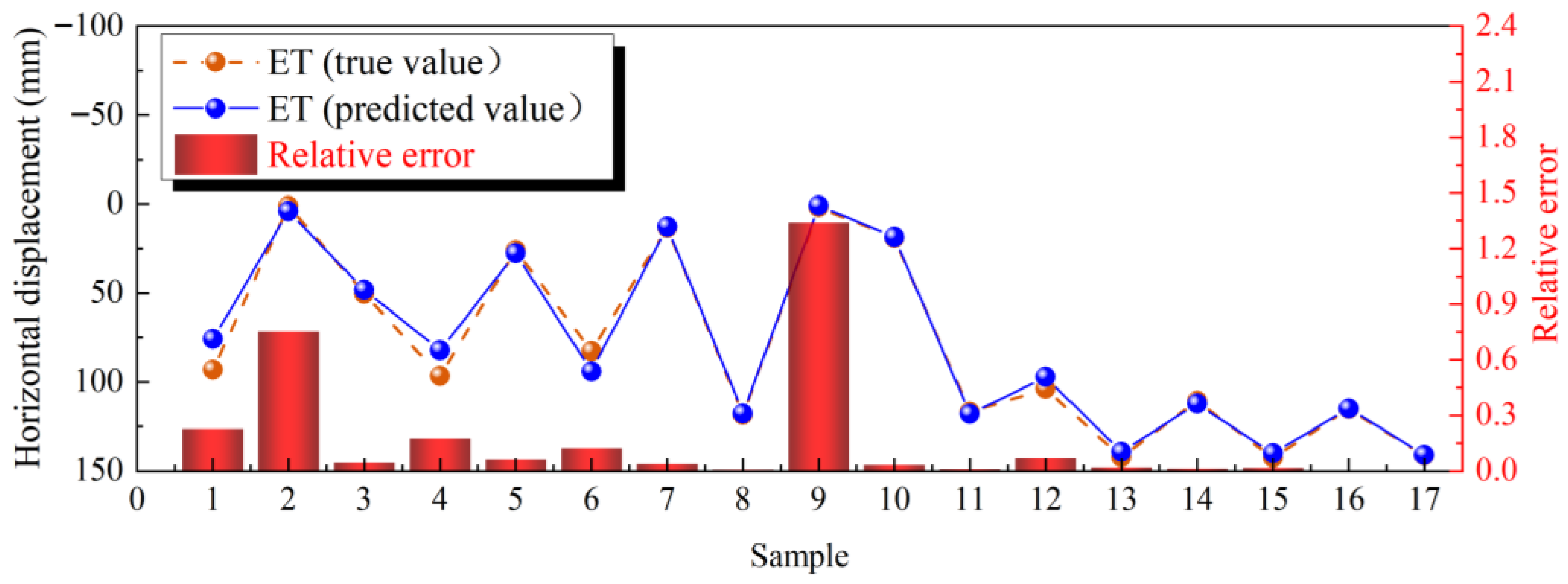

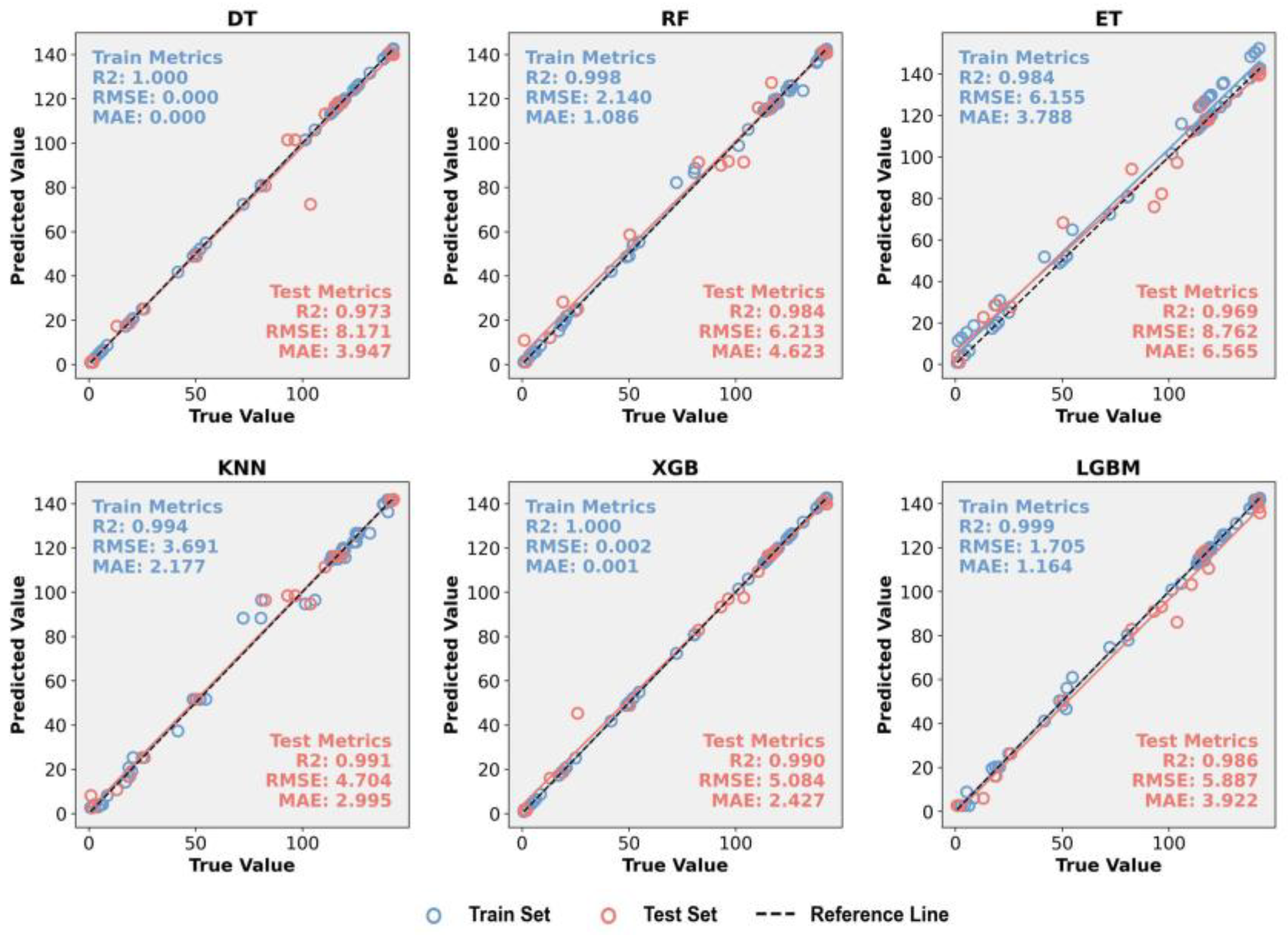

3.1. Prediction Results of Displacement

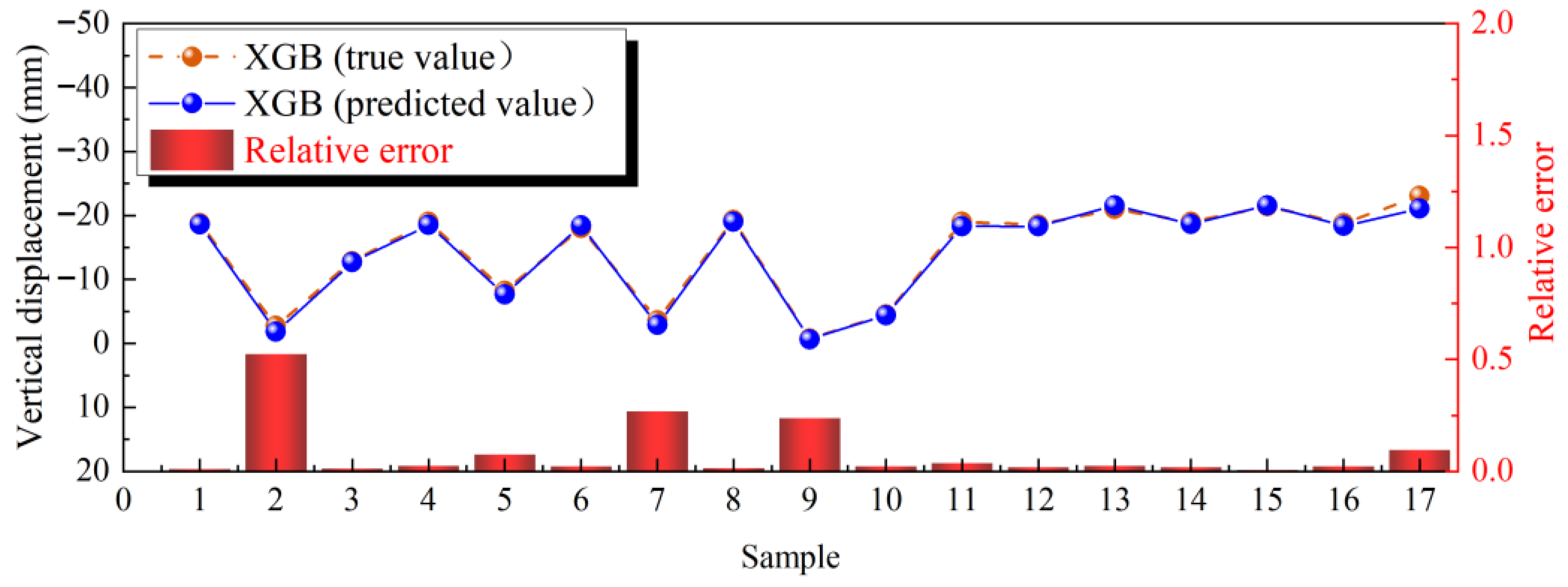

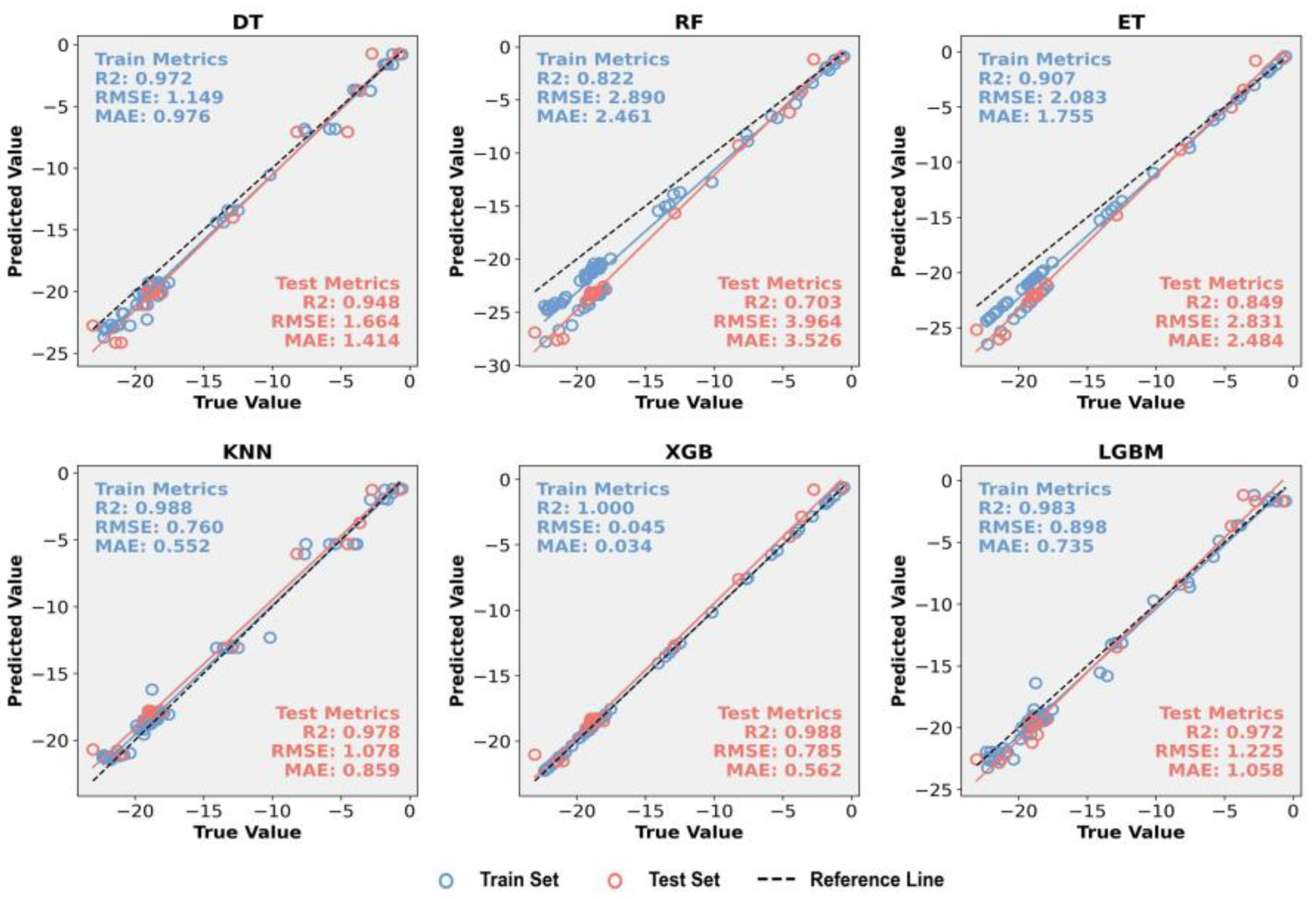

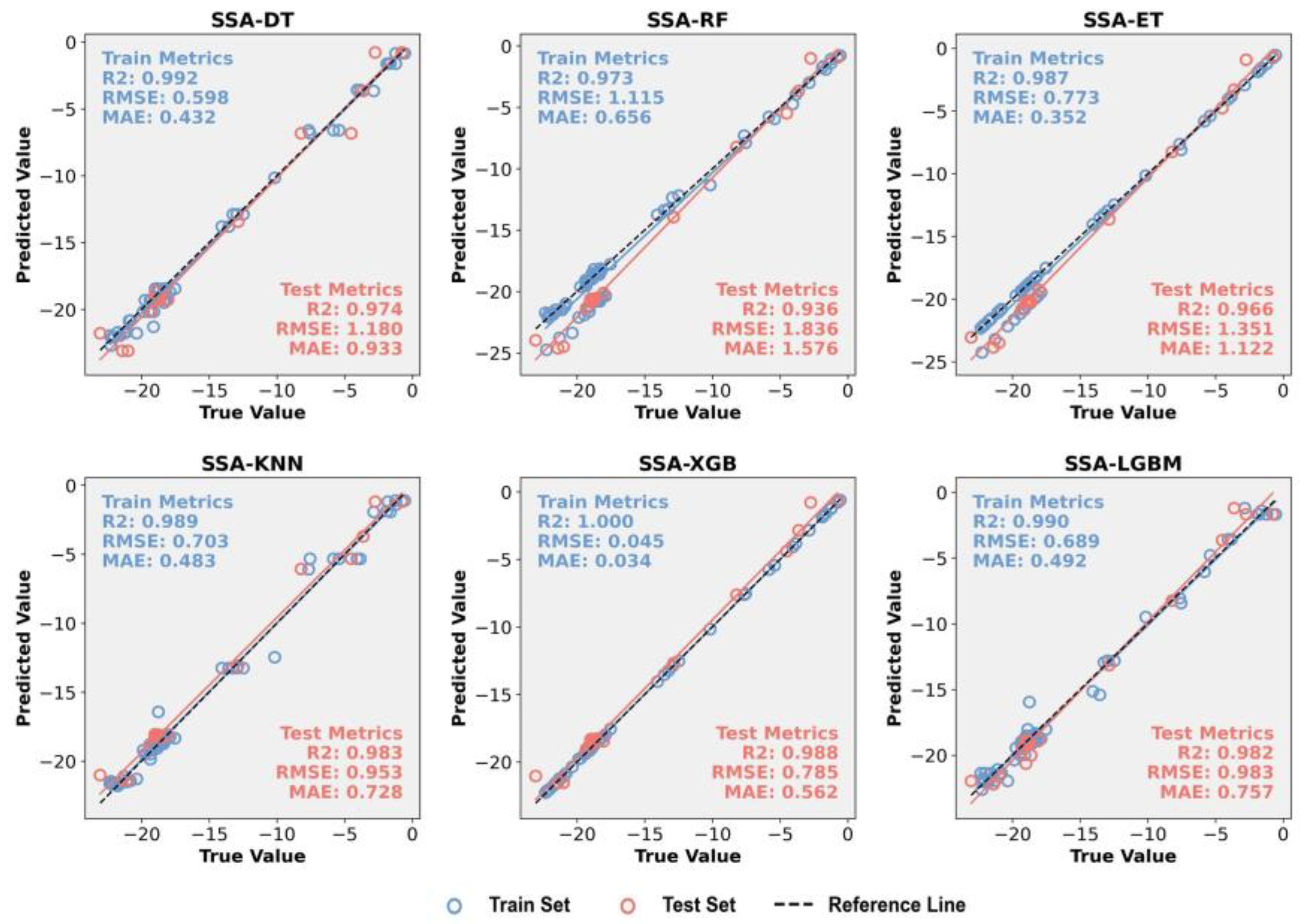

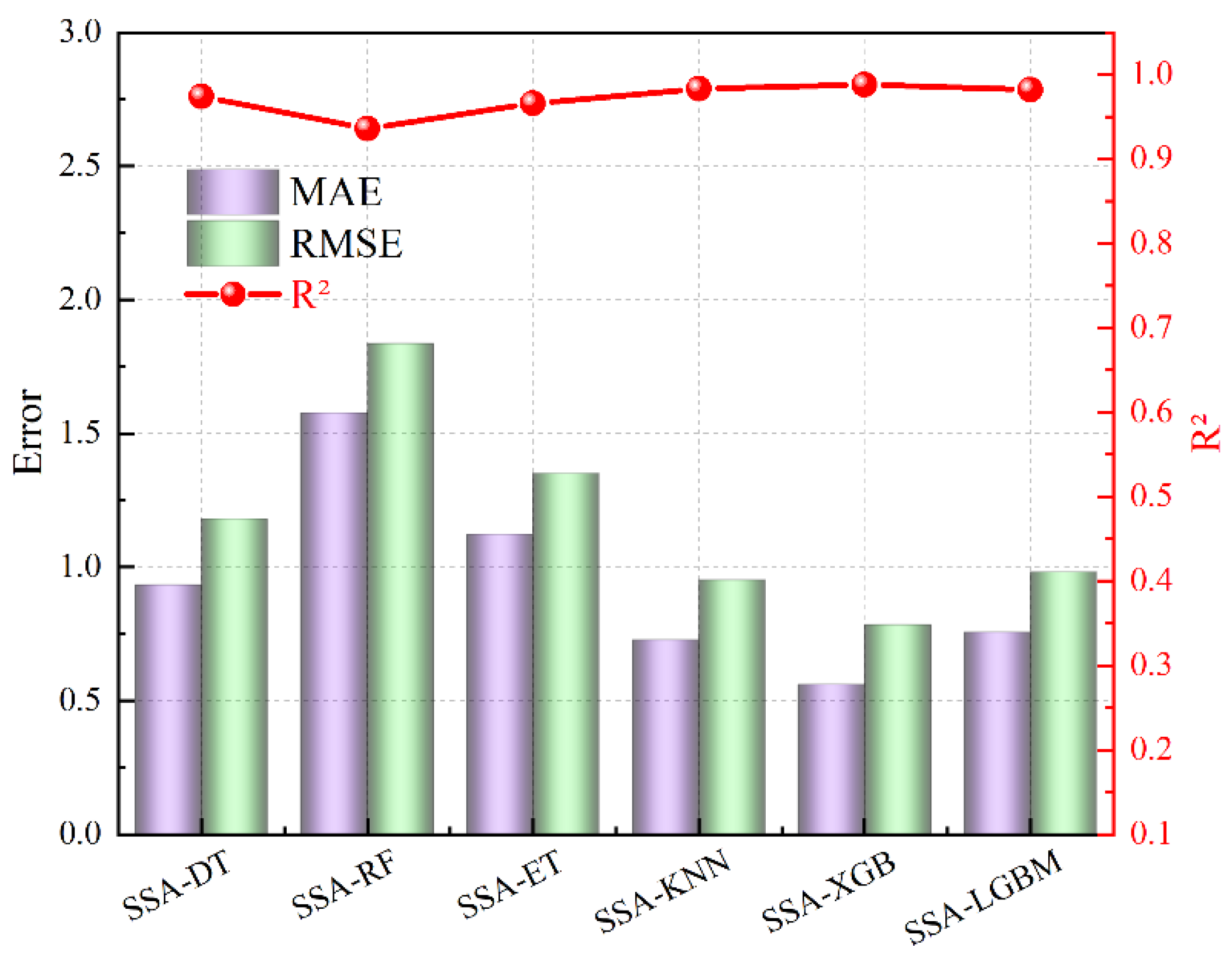

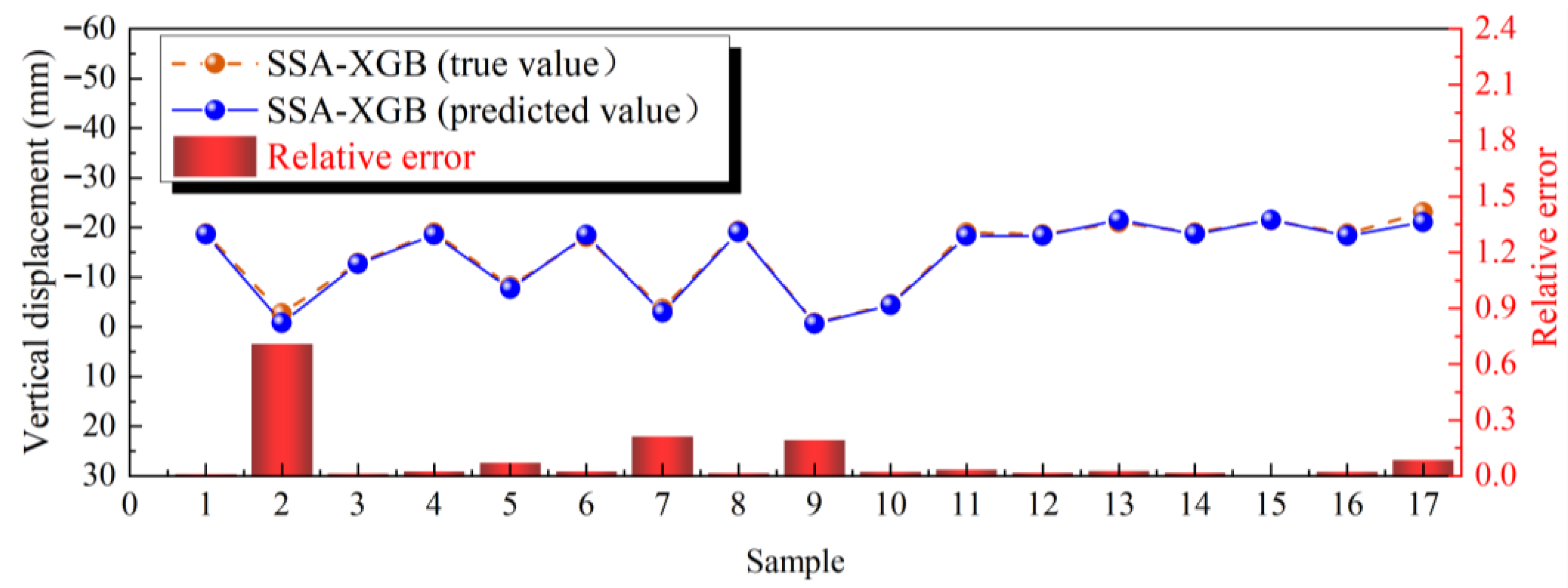

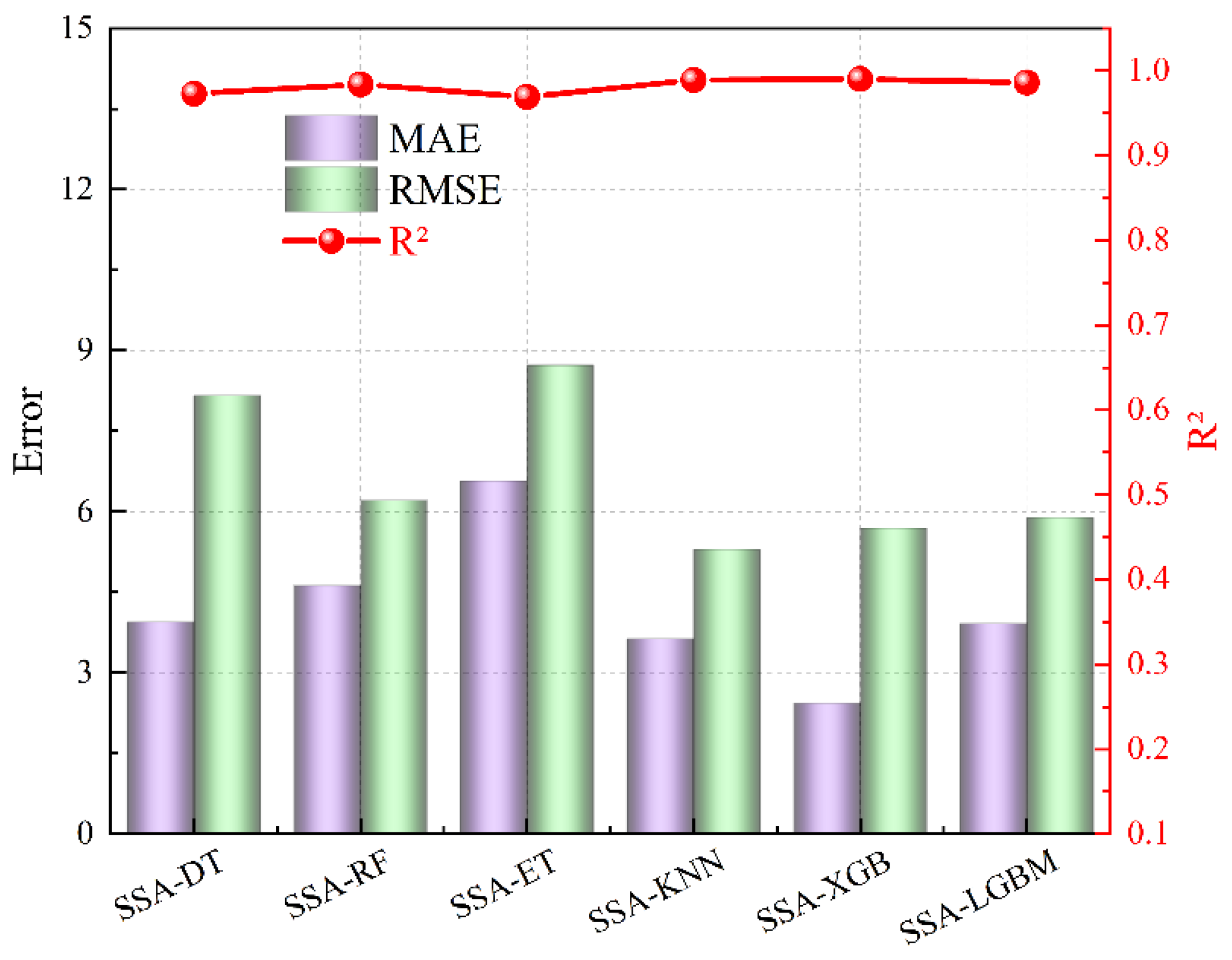

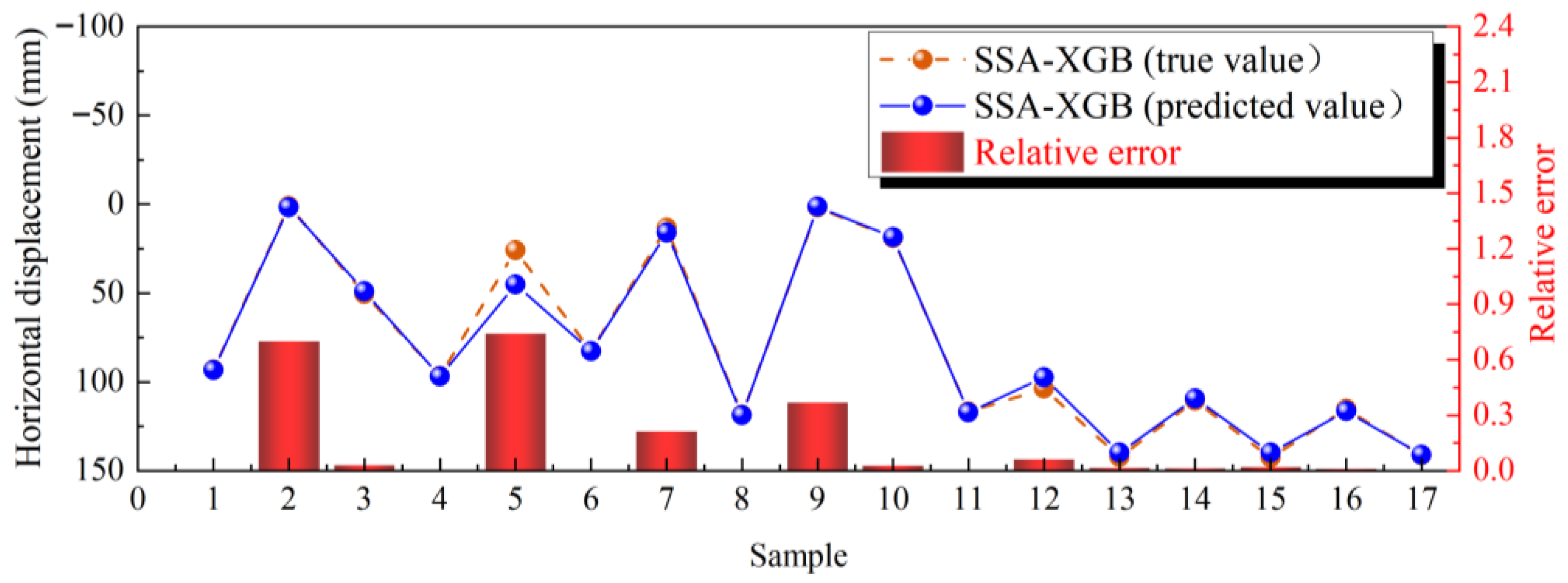

3.2. Displacement Prediction Results of SSA-Optimized Models

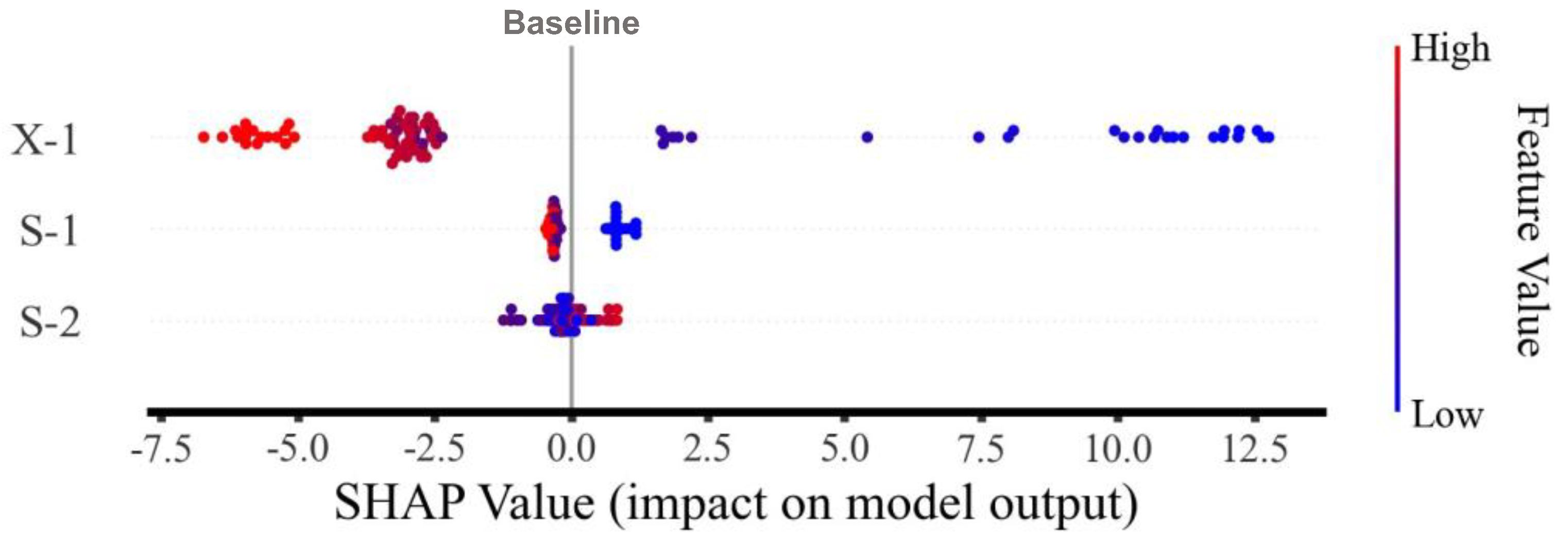

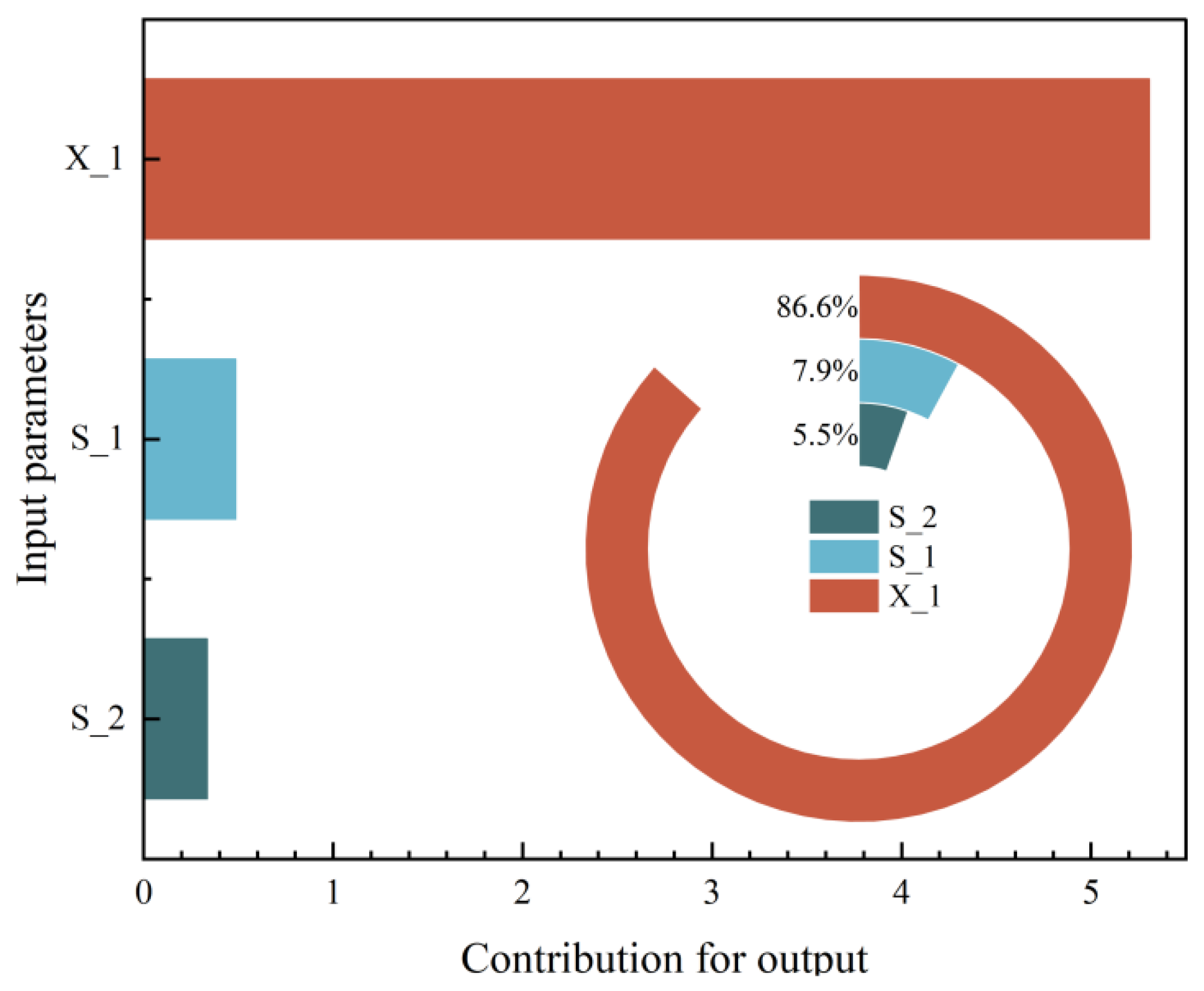

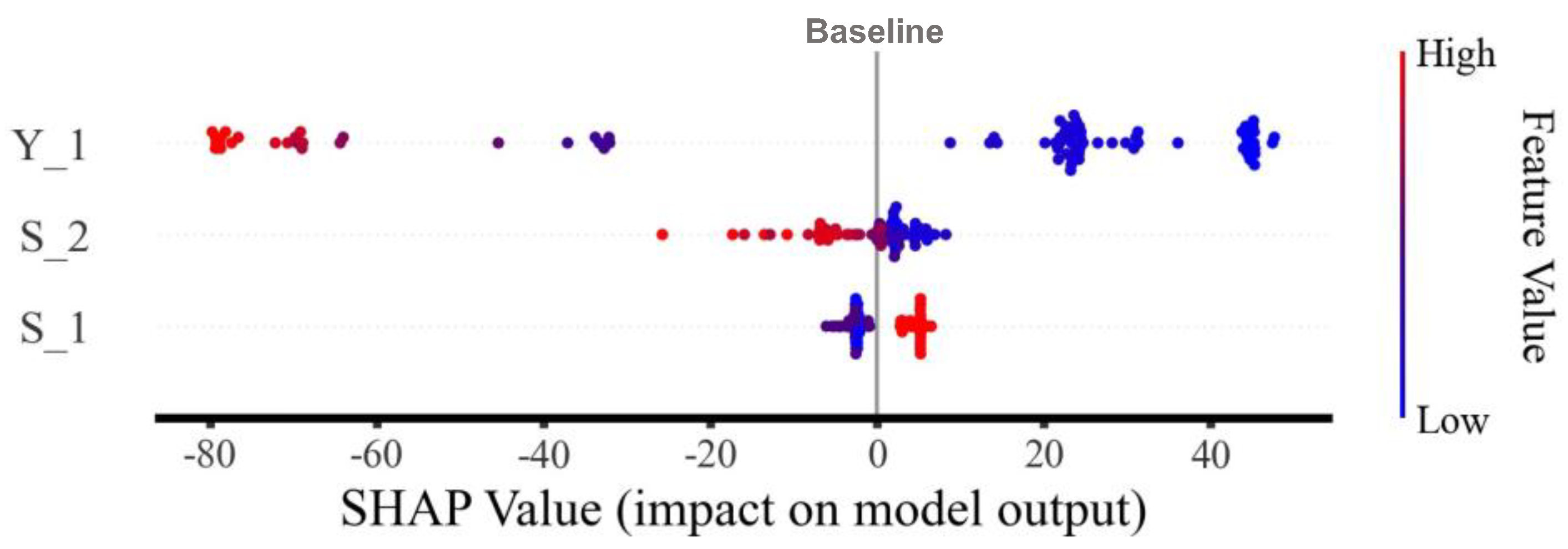

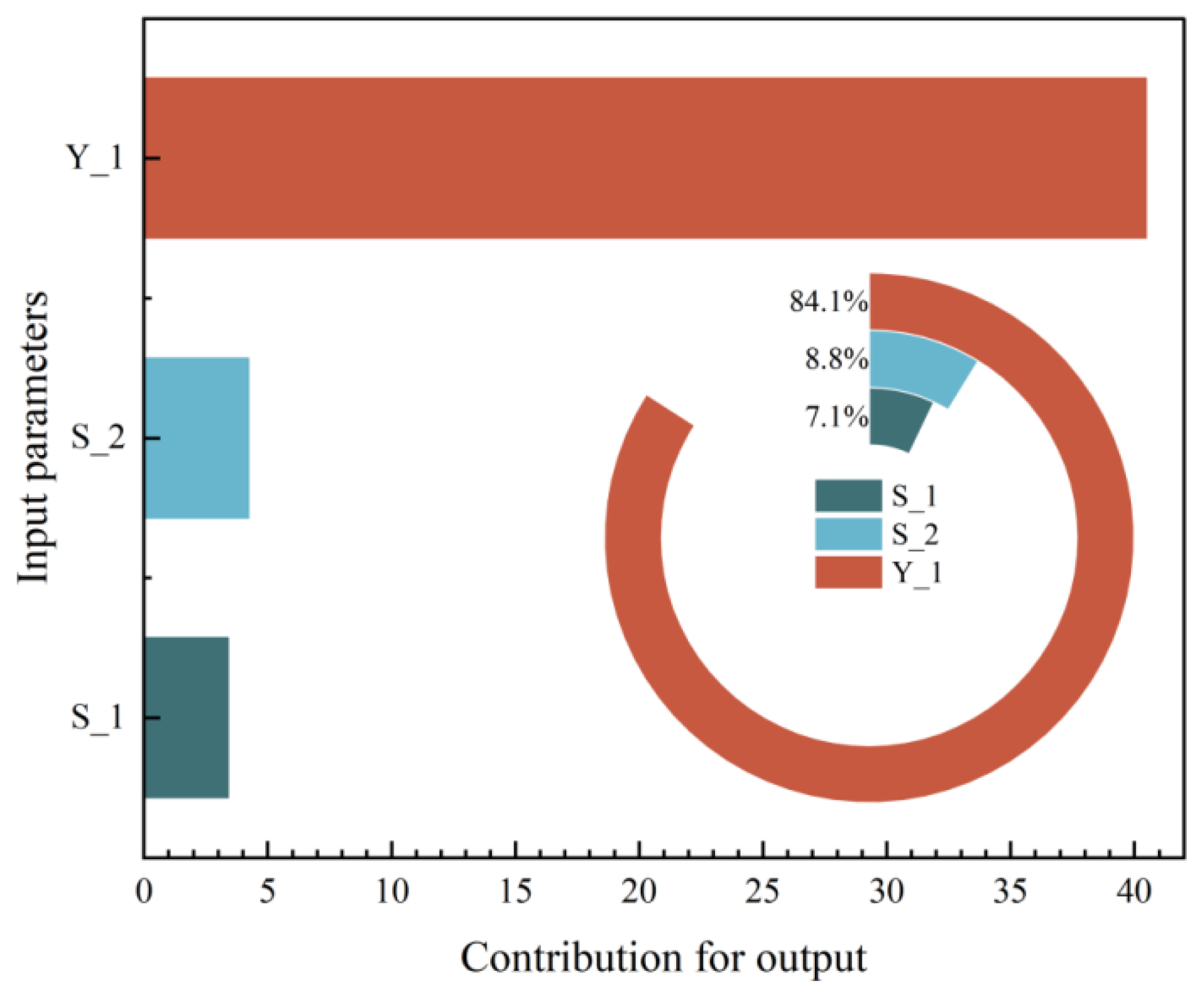

3.3. SHAP-Based Interpretability Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.W.; Chen, Z. A Systematic Review of Urban Underground Space Development in China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 131, 104785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, T.; Yang, H. Challenges and Countermeasures of Deep Excavation in Soft Soil Areas of Coastal Cities. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2022, 36, 04022045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Wang, J. Deformation Characteristics of a 30-m Deep Excavation in Soft Clay. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 134, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liao, F.; Wang, L.; Lin, J.; Wang, J. Multi-Stage and Multi-Parameter Influence Analysis of Deep Foundation Pit Excavation on Surrounding Environment. Buildings 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Ma, S. Multifactor Uncertainty Analysis of Construction Risk for Deep Foundation Pits. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.Y. Deep Excavation: Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Finno, R.J.; Blackburn, J.T.; Roboski, J.F. Three-Dimensional Effects for Supported Excavations in Clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Kung, G.T.C.; Juang, C.H.; Hashash, Y.M.A. Simplified Model for Evaluating Damage Potential of Buildings Adjacent to a Braced Excavation. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Z. A Probabilistic Risk Assessment Framework for Building Damage Induced by Adjacent Excavations. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, R.B. Deep Excavations and Tunneling in Soft Ground. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Mexico City, Mexico, 25–29 August 1969; pp. 225–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clough, G.W.; O’Rourke, T.D. Construction Induced Movements of Insitu Walls. In Design and Performance of Earth Retaining Structures; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 1990; pp. 439–470. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, P.G.; Ou, C.Y. Shape of Ground Surface Settlement Profiles Caused by Excavation. Can. Geotech. J. 1998, 35, 1004–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, H.G.; Chen, L.T.; Hull, T.S. Model Tests on Single Piles Subjected to Lateral Soil Movement. Soils Found. 1995, 35, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Analytical Solution for Braced Excavation Deformation Considering Soil Stress History. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04021280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkgreve, R.B.J.; Swolfs, W.M.; Engin, E. PLAXIS 2015; PLAXIS bv: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, D.M.; Zdravkovic, L. Finite Element Analysis in Geotechnical Engineering: Theory; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, A.T.C.; Kulhawy, F.H. Reliability Assessment of Basement Wall Movements Using Finite Element Method. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, G.T.C.; Hsiao, E.C.L.; Schuster, M.; Juang, C.H. A Neural Network Approach to Estimating Deflection of Diaphragm Walls Induced by Excavation in Clays. Comput. Geotech. 2007, 34, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, T. Small-Strain Stiffness of Soils and Its Numerical Consequences; Universität Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tschuchnigg, F.; Schweiger, H.F. The Embedded Pile Concept—Verification of an Efficient Tool for Modelling Deep Excavations. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 63, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoon, K.K.; Kulhawy, F.H. Characterization of Geotechnical Variability. Can. Geotech. J. 1999, 36, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, D. Bayesian Model Comparison and Characterization of Undrained Shear Strength for Clays. Eng. Geol. 2016, 203, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, H.F. Results from Numerical Benchmark Exercises in Geotechnics. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Numerical Models in Geomechanics, Davos, Switzerland, 6–8 September 1995; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Do, N.A.; Dias, D.; Oreste, P.; Djeran-Maigre, I. Three-Dimensional Numerical Simulation for a Deep Excavation in Soft Soil. Geomech. Eng. 2014, 7, 155–181. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, C.H.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Ravichandran, N.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J. Robust Geotechnical Design of Drilled Shafts in Sand: A Bayesian Perspective. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 2000–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hwang, J.H.; Luo, Z.; Juang, C.H.; Xiao, J. Probabilistic Back Analysis of Braced Excavation Based on Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2015, 29, 04014036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.A. A Review of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Shallow Foundations. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2015, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Samui, P. Assessment of Pile Drivability Using Random Forest Regression and Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines. Georisk 2021, 15, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. ANN-Based Dynamic Prediction of Daily Ground Settlement of Foundation Pit Considering Time-Dependent Influence Factors. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Mamat, R.; Ramli, A.; Che Omar, M.B.H.; Samad, A.; Sulaiman, S.A. Application of Machine Learning for Predicting Ground Surface Settlement beneath Road Embankments. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2021, 12, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, C.; Luo, H. Intelligent Approach Based on Random Forest for Safety Risk Prediction of Deep Foundation Pit in Subway Stations. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2019, 33, 05018004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, X.-N.; Nguyen, H.; Choi, Y.; Nguyen-Thoi, T.; Zhou, J.; Dou, J. Prediction of Slope Failure in Open-Pit Mines Using a Novel Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Model Based on Decision Tree and Evolution Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. The Use of Machine Learning Models for Predicting Maximum Bridge Pile Lateral Displacements Caused by Excavation of Adjacent Foundation Pit. J. Eng. Res. 2025, Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. On Hyperparameter Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms: Theory and Practice. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, M.; Hutter, F. Hyperparameter Optimization. In Automated Machine Learning: The Springer Series on Challenges in Machine Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yan, Z.; Teng, S.; Cui, F.; Bassir, D. A Bridge Vibration Measurement Method by UAVs Based on CNNs and Bayesian Optimization. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2023, 9, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.G.; Goh, A.T.C. Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines and Neural Network Models for Prediction of Load and Moment Capacity of Circular Foundations. Eng. Geol. 2016, 209, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Xiao, M. Deformation Evaluation on Surrounding Rocks of Underground Caverns Based on PSO-LSSVM. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 69, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. A Novel Swarm Intelligence Optimization Approach: Sparrow Search Algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2020, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhuang, M.-L.; Xu, R.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y. Inversion Analysis for Thermal Parameters of Mass Concrete Based on the Sparrow Search Algorithm Improved by Mixed Strategies. Buildings 2024, 14, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, D.; Stefik, M.; Choi, J.; Miller, T.; Stumpf, S.; Yang, G.Z. XAI—Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaay7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscher, R.; Bohn, B.; Duarte, M.F.; Garcke, J. Explainable Machine Learning for Scientific Insights and Discoveries. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 42200–42216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, D.; Zhou, X.; Mi, C.; Wen, H. Insights into Geospatial Heterogeneity of Landslide Susceptibility Based on the SHAP-XGBoost Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Yin, K.; Luo, H.; Li, J. Landslide Identification Using Machine Learning. Geosci. Front. 2020, 11, 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.C.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; La, D.D.; Kumar, G.; Rene, E.R.; Nguyen, D.D.; Chang, S.W.; Chung, W.J.; Nguyen, X.H.; Nguyen, V.K. Development of Machine Learning-Based Models to Forecast Solid Waste Generation in Residential Areas: A Case Study from Vietnam. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.W.; Ng, C.W.W.; Liu, G.B. Characteristics of Wall Deflections and Ground Surface Settlements in Shanghai. Can. Geotech. J. 2005, 42, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanapathirana, D.S.; Nishanthan, R. Influence of Deep Excavation Induced Ground Movements on Adjacent Piles. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 52, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.Y.; Hsieh, P.G.; Chiou, D.C. Characteristics of Ground Surface Settlement during Excavation. Can. Geotech. J. 1993, 30, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finno, R.J.; Roboski, J.F. Three-Dimensional Responses of a Tied-Back Excavation through Clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DT | RF | ET | KNN | XGB | LGBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.948 | 0.703 | 0.849 | 0.978 | 0.988 | 0.972 |

| RMSE | 1.664 | 3.964 | 2.831 | 1.078 | 0.785 | 1.225 |

| MAE | 1.414 | 3.526 | 2.484 | 0.859 | 0.562 | 1.058 |

| DT | RF | ET | KNN | XGB | LGBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.967 | 0.964 | 0.983 | 0.896 | 0.972 | 0.968 |

| RMSE | 9.050 | 9.370 | 6.508 | 16.002 | 8.239 | 8.941 |

| MAE | 5.335 | 6.971 | 4.046 | 14.736 | 4.986 | 8.022 |

| Model | Parameter Name | Parameter Meaning | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DT | max_depth | maximum tree depth | 8 |

| min_samples_leaf | minimum number of samples per leaf | 2 | |

| min_samples_split | minimum samples to split a node | 4 | |

| RF | n_estimators | number of estimators | 200 |

| max_depth | maximum tree depth | 10 | |

| min_samples_split | minimum number of samples to split a node | 4 | |

| ET | n_estimators | number of estimators | 250 |

| max_depth | maximum tree depth | 12 | |

| min_samples_split | minimum number of samples to split a node | 10 | |

| KNN | n_neighbors | number of neighbors | 7 |

| weights | type of weights | distance | |

| leaf_size | leaf size of the tree | 30 | |

| XGB | n_estimators | number of estimators | 300 |

| learning_rate | learning rate | 0.05 | |

| max_depth | maximum tree depth | 6 | |

| reg_lambda | L2 regularization | 1.0 | |

| LGBM | n_estimators | number of estimators | 1000 |

| learning_rate | learning rate | 0.06 | |

| max_depth | maximum depth | 10 | |

| num_leaves | number of leaves | 64 | |

| bagging_fraction | subsample rate per iteration | 0.9 | |

| lambda_l2 | L2 regularization | 1.0 |

| SSA-DT | SSA-RF | SSA-ET | SSA-KNN | SSA-XGB | SSA-LGBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.974 | 0.936 | 0.966 | 0.983 | 0.988 | 0.982 |

| RMSE | 1.180 | 1.836 | 1.351 | 0.953 | 0.785 | 0.983 |

| MAE | 0.933 | 1.576 | 1.122 | 0.728 | 0.562 | 0.757 |

| SSA-DT | SSA-RF | SSA-ET | SSA-KNN | SSA-XGB | SSA-LGBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.973 | 0.984 | 0.969 | 0.989 | 0.990 | 0.986 |

| RMSE | 8.171 | 6.213 | 8.726 | 5.294 | 5.684 | 5.887 |

| MAE | 3.947 | 4.623 | 6.565 | 3.638 | 2.427 | 3.922 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, G.; Zhang, F.; Guo, D.; Yan, A.; Fu, Q.; He, Z. Prediction of Excavation-Induced Displacement Using Interpretable and SSA-Enhanced XGBoost Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234372

You G, Zhang F, Guo D, Yan A, Fu Q, He Z. Prediction of Excavation-Induced Displacement Using Interpretable and SSA-Enhanced XGBoost Model. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234372

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Guiliang, Fan Zhang, Dianta Guo, Anfu Yan, Qiang Fu, and Zhiwei He. 2025. "Prediction of Excavation-Induced Displacement Using Interpretable and SSA-Enhanced XGBoost Model" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234372

APA StyleYou, G., Zhang, F., Guo, D., Yan, A., Fu, Q., & He, Z. (2025). Prediction of Excavation-Induced Displacement Using Interpretable and SSA-Enhanced XGBoost Model. Buildings, 15(23), 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234372