1. Introduction

Sleep is one of the most fundamental and crucial physiological needs for humans. Poor sleep quality and persistent sleep difficulties can adversely affect mental state and overall health and may even impair neurodevelopmental processes critical for young people, particularly in prefrontal cortex maturation and HPA axis regulation, making it a matter of great concern. The lighting environment in residential spaces plays an important role in regulating sleep and circadian rhythms, influencing physiological and psychological health. Therefore, creating a healthy lighting environment in residential spaces to ensure sound sleep quality is a vital area of research.

Sleep is fundamental to both physical and mental health, with insufficient sleep being recognized in recent years as a critical modifiable risk factor for a range of diseases. Physiologically, sleeping less than six hours per night can alter gene function [

1], while acute sleep deprivation may cause DNA damage and increase the risk of chronic diseases [

2]. In women, inadequate sleep has been linked to impaired bone development and osteoporosis [

3], and sleep restriction has been shown to significantly increase abdominal and visceral fat—key risk factors for cardiometabolic disorders [

4]. Concurrently, sleep exerts a profound influence on mental well-being. REM sleep deprivation can heighten susceptibility to threatening stimuli and intensify emotional responses [

5], and daytime emotional experiences are significantly correlated with prior sleep quality [

6]. Furthermore, irregular sleep patterns and chronic sleep loss are associated with increased negative social perceptions and an elevated long-term risk of depression [

7,

8]. In summary, sleep problems detrimentally affect both physiological health and emotional regulation, underscoring the necessity of targeted interventions to improve sleep as a core component of public health strategy.

In recent years, the population suffering from sleep problems has been increasing. In 2021, Morin surveyed 594 adults and found that, due to the impact of COVID-19, the prevalence of insomnia increased by 26.7% from 2018 to 2020 [

9]. The 2024 China Sleep Research Report showed that the average sleep index of Chinese residents in 2023 continued to decline compared with 2022 and 2021, indicating an ongoing reduction in sleep duration and quality [

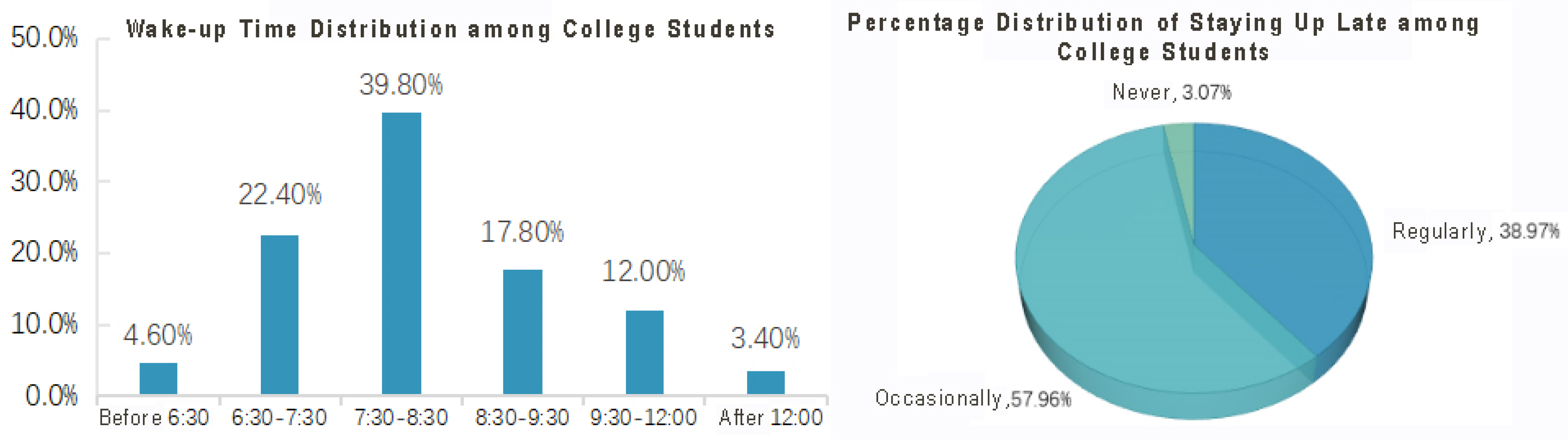

10]. The Chinese government has also emphasized sleep health as part of the national “Healthy China 2019–2030 Action Plan,” which defines adult sleep duration standards and regards adequate sleep as a vital indicator of physical and mental well-being. However, recent investigations reveal that a large proportion of Chinese university students exhibit delayed sleep phases, irregular schedules, and shortened sleep duration. As shown in

Figure 1, 57.96% of college students frequently stay up late and 38.97% occasionally stay up late, while only 3.07% do not show late-sleep behavior. Moreover, 39.80% of students get up between 7:30 and 8:30 a.m. and approximately 15.40% get up after 9:30 a.m., suggesting a widespread “late-sleep, late-wake” rhythm [

11]. This trend parallels global findings: a 2010 study by Lund et al. reported that 30–40% of European adolescents experienced insufficient sleep associated with electronic device use [

12], and the U.S. Youth Sleep Report showed that the proportion of teenagers sleeping less than seven hours rose by 16–17% from 2009 to 2015 [

13]. The 2023 China Healthy Sleep White Paper further indicated that 84.3% of Chinese youth report poor sleep quality [

11]. These findings highlight that young adults—particularly college students—are a key population for studying circadian phase shifts and the influence of environmental factors such as light exposure on sleep rhythm and emotional regulation. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of sleep phase variation in healthy youth, rather than focusing on clinical insomnia, is crucial for promoting healthy sleep and mental stability in modern society.

Light is one of the essential environmental factors in human life. It is a synchronizer for various physiological circadian rhythms, such as alertness, body temperature fluctuations, and melatonin secretion [

14], making it the most significant environmental factor influencing human circadian rhythms. Melatonin, an indole hormone secreted by the pineal gland, is closely related to various physiological processes, including the central nervous, reproductive, and immune systems [

15]. Light exposure causes significant changes in melatonin secretion, with the degree of change depending on the total amount and quality of light received [

16]. Prolonged exposure to insufficient or inappropriate lighting conditions may lead to circadian rhythm disruptions, decreased sleep efficiency, mood disturbances, and other health issues [

17]. A study by Blume and colleagues found that light intensity at night significantly inhibits melatonin secretion and affects sleep, with the inhibitory effect positively correlated with light intensity [

18]. Even under low light conditions, exposure to light at night and in the early morning suppresses the release of sleep-promoting hormones, such as melatonin, by affecting the intrinsic rhythm pacemaker of retinal intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), shifting the circadian clock to a later phase [

19], which results in difficulty falling asleep at night.

Beyond these physiological mechanisms, light also influences mood and cognition, linking visual comfort with psychological well-being. In modern indoor environments where people spend most of their daytime hours, lighting conditions not only determine visual performance but also play a central role in regulating alertness, fatigue, and subsequent sleep quality. Consequently, healthy lighting design must address both circadian and emotional dimensions to support overall well-being.

Within this context, research on workplace lighting has mainly focused on optimizing daytime illumination to enhance alertness and productivity [

20,

21]. However, lighting also acts as a key circadian zeitgeber that shapes melatonin secretion and, consequently, influences nighttime sleep quality. Recent findings highlight this regulatory link between daytime lighting and nocturnal sleep: Benedetti et al. showed that dynamic office lighting can advance melatonin onset and promote physiological sleep readiness [

22]; Aguilar-Carrasco et al. emphasized the need to dynamically adjust color temperature and luminous flux according to natural light variations [

23]; and Boubekri et al. reported that optimized daytime lighting increases employees’ nightly sleep duration by about 37 min [

24]. These studies collectively suggest that well-designed workplace lighting can improve both daytime performance and subsequent sleep health.

The light environment affects various aspects of the human body, including mood, psychology, physiology, and metabolism, through its impact on sleep. Investigating the influence of the residential lighting environment on sleep holds significant scientific value and application prospects. Utilizing an orthogonal experimental method within a laboratory simulation, this study quantifies the impact of the residential light environment on sleep health to explore the psycho-physiological mechanisms of its factors, thereby providing a scientific basis for precise evaluation and healthy lighting rhythm design. Therefore, this study aims to quantitatively assess the effects of illuminance, correlated color temperature, and blue light ratio on comfort, alertness, task performance, and sleep quality, to identify optimal lighting configurations that support well-being in daily activities, and to develop a temporal rhythm lighting framework for residential applications. It is hypothesized that higher illuminance combined with lower color temperature enhances comfort and positive emotion, that higher blue light ratios improve alertness but may reduce sleep quality, and that cycling lighting with moderate illuminance and low blue light ratio better aligns with circadian rhythms to improve sleep efficiency.

2. Methods

The experiment was conducted in the Light and Color Laboratory at Dalian University of Technology (Dalian, China), equipped with an adjustable LED lighting system. The laboratory was surrounded by white walls, with dimensions of 4.0 and 4.5 and 2.8 m (length and width and height). Additionally, desks and chairs were provided for the participants, with the desk height set at 0.75 m. The lighting protocol incorporated both static and cycling modes, in which illuminance (200, 800, 1400 lx), correlated color temperature (3200 K, 4700 K, 6200 K), and blue light ratio (0.25, 0.4, 0.6) were systematically manipulated to control the lighting environment. In the cycling mode, these parameters varied synchronously in 20 min cycles to simulate the temporal rhythm of residential lighting conditions.

Considering the delayed physiological response to light exposure—with melatonin suppression typically appearing 5–10 min after onset and potentially requiring over one hour under dim conditions—each experimental session included a continuous 120 min exposure period to ensure a measurable physiological effect. All experiments were conducted during a fixed pre-sleep period (20:00–22:00) in late December to maintain consistency across lighting conditions.

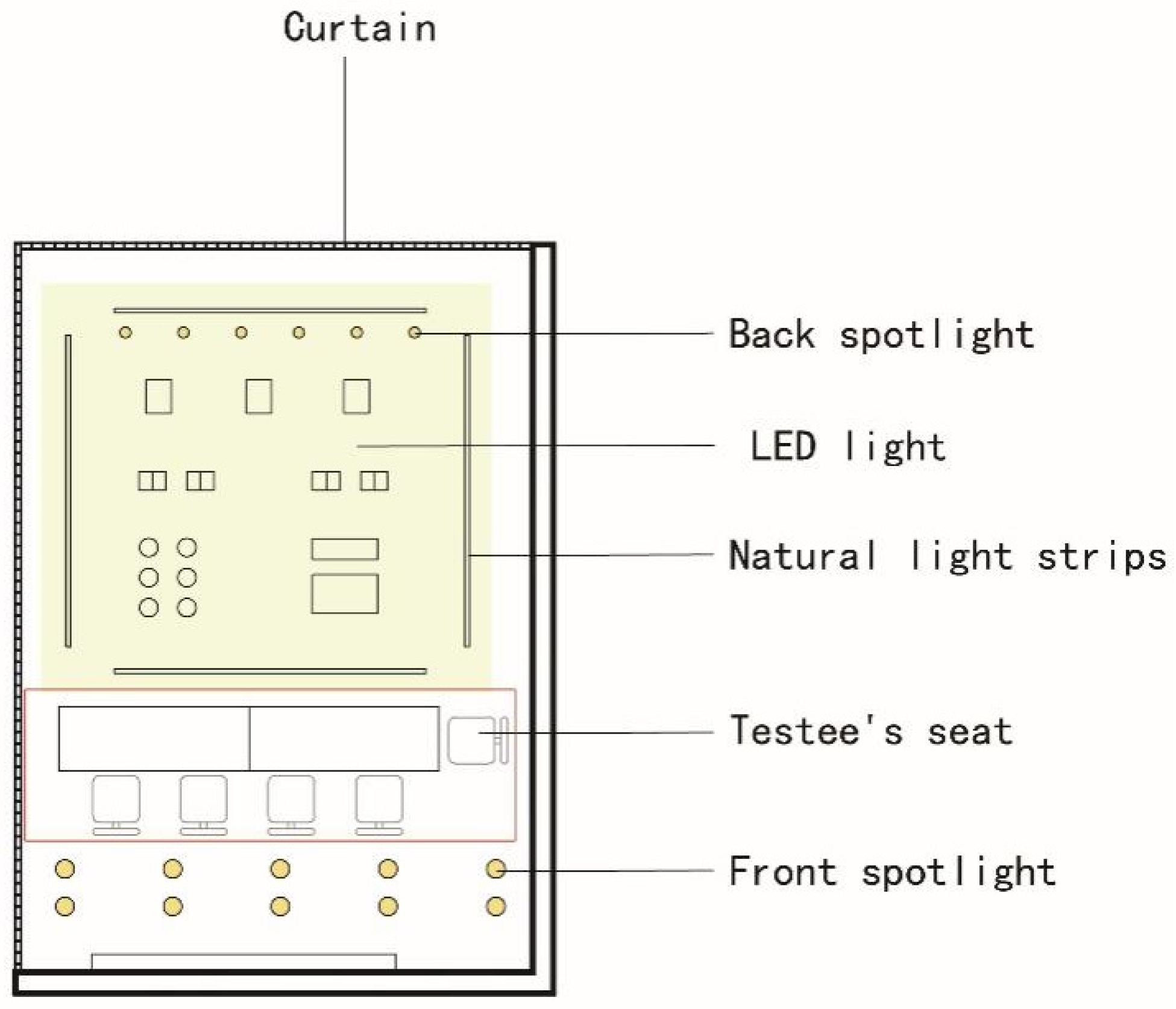

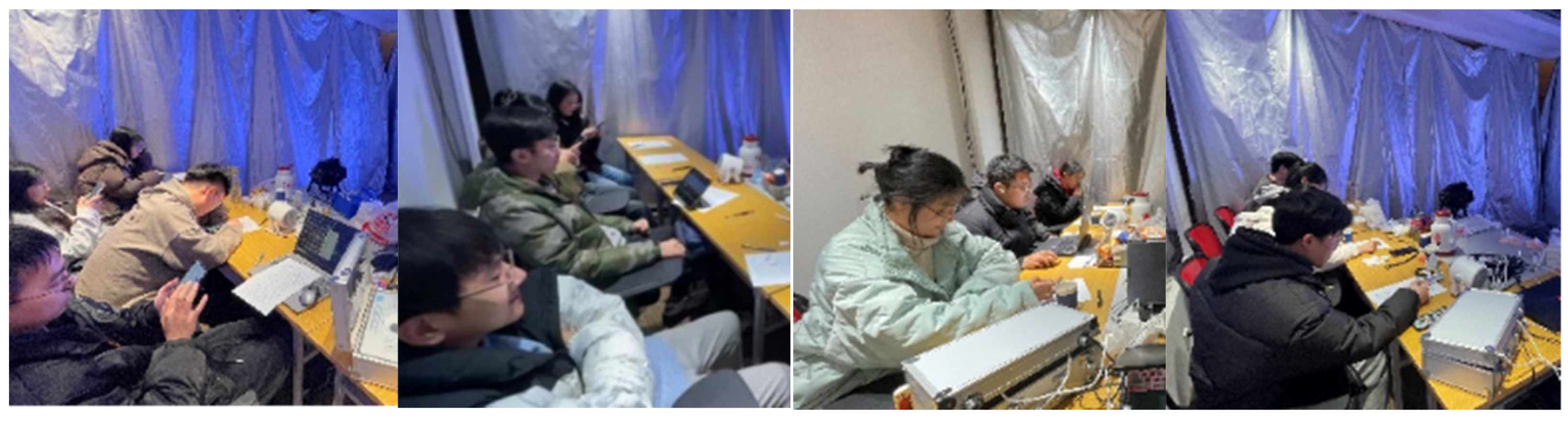

A heating device was placed in the corner of the laboratory to maintain suitable physical environmental parameters, such as temperature, humidity, and color rendering index, to prevent interference from other indoor environmental factors affecting the experimental lighting conditions. To eliminate the influence of natural light, which is difficult to control and has complex components, an opaque blackout curtain was used to block out external light interference. The layout of the Light and Color Laboratory is shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

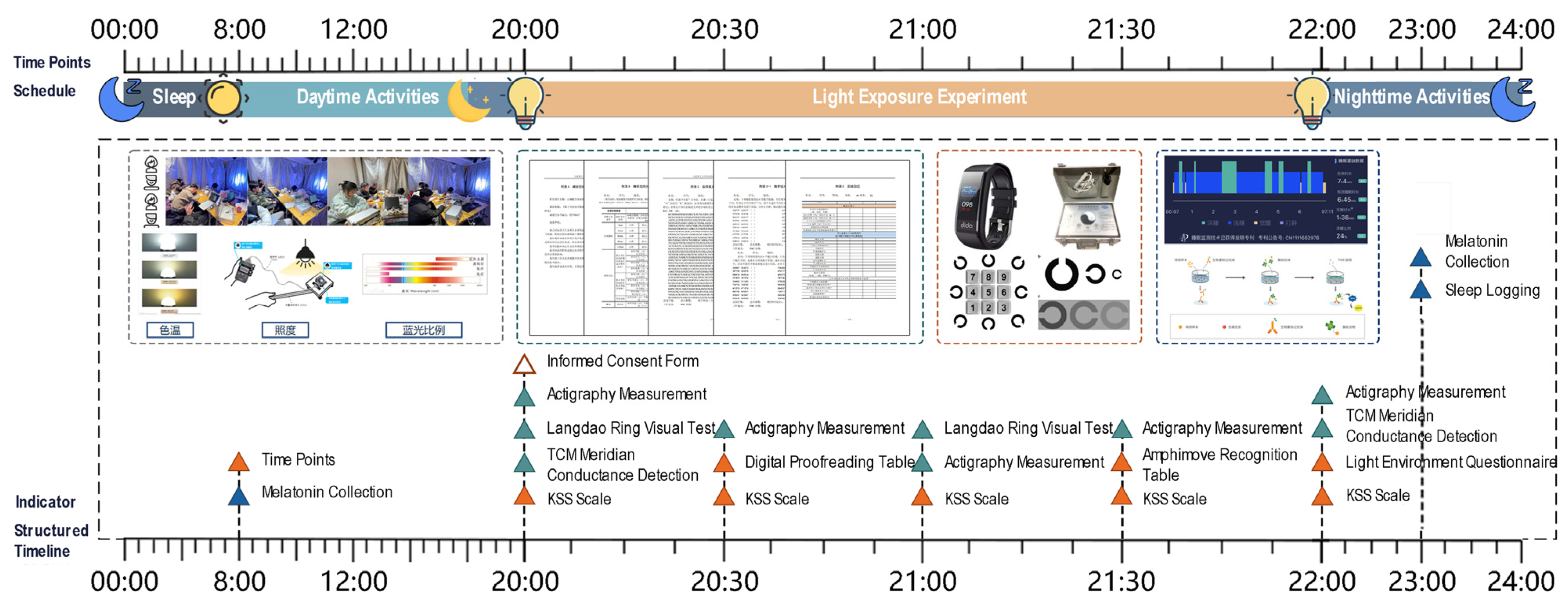

Figure 4 shows the complete procedure of the experiment. Before the participants entered the laboratory, the lighting environment parameters of the experimental space were calibrated according to the experimental design requirements. After ensuring the lighting fixtures were stable and operating under accurate conditions for 5 min, the participants were allowed to enter the laboratory to begin the experiment. Participants were tested in batches of four per session within the same laboratory space, with each batch completing four lighting scenarios sequentially. This protocol resulted in data collection over 16 nights. This study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Dalian University of Technology (Approval No. DUTSAFA240401-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the research.

The American Sleep Medicine Center has proposed five practical dimensions for monitoring sleep health: sleep satisfaction, alertness during wakefulness, sleep timing, sleep efficiency, and sleep duration [

25]. These five indicators can objectively reflect an individual’s sleep quality. This study employs a comprehensive evaluation method combining both objective and subjective assessments. The objective evaluation primarily involves measuring the lighting environment and physiological parameters, task performance, and health status of the participants during the experiment and then judging the impact of different lighting environments on sleep quality based on the results. The subjective evaluation method measures and assesses sleep quality, reflecting participants’ subjective perceptions of their sleep quality.

- (1)

Instrumental Measurement

To ensure that the participants were in a relatively stable physical environment throughout the experiment, the Testo175H1 temperature and humidity data logger (Testo SE & Co. KGaA, Lenzkirch, Germany) was used to measure and record the relevant parameters from the beginning to the end.

The CL-500A spectroradiometer (Konica Minolta, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to determine different scenarios’ color temperature and illuminance to meet the preset values. The LMK6 imaging luminance and colorimeter (Instrument Systems GmbH, Munich, Germany), along with the HP-350C spectral illuminance meter (Everfine Photo-E-Info Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China), were used to measure the lamps’ light spectrum and blue light ratio in each working condition. During the experiment, a motion sensor was used to measure the participant’s heart rate and blood oxygen levels. The Traditional Chinese Medicine meridian detector measured the electrical energy values at 24 acupuncture points on the human body’s surface to quantify and assess the participants’ health status [

26].

In addition, salivary melatonin levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. Saliva samples were collected at fixed time points before and after sleep to assess circadian phase shifts under different lighting environments. The assay employed a solid-phase antibody technique, in which samples were added to microplate wells pre-coated with a purified human melatonin antibody. After the addition of an HRP-conjugated melatonin antibody and subsequent formation of an immune complex, TMB substrate was added for color development. The resulting color intensity, proportional to the melatonin concentration, was measured at 450 nm, and concentrations were quantified against a standard curve.

- (2)

Subjective Evaluation

Subjective sleepiness was assessed throughout the experiment using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS), a well-validated 9-point self-report instrument commonly employed to evaluate the effects of light exposure on alertness [

27], and extensively applied in lighting research [

28,

29]. Concurrently, participants completed detailed sleep diaries to track and record their emotional states and perceived comfort levels across the different experimental conditions.

- (3)

Visual Task Performance Assessment

The assessment of visual performance was typically carried out using a dose–response task. The visual workload was recorded using visual task sheets, which included three different types of visual tasks: letter recognition, pattern recognition, and number recognition [

30]. Letter recognition was assessed using a customized letter chart comprising Cyrillic characters (analogous to the Amfinnsson table). This approach follows the established psychometric principle of using optotypes for visual acuity measurement, as validated in standardized charts like the ETDRS [

31] and Landolt C [

32]. Contrast sensitivity was evaluated with the FrACT10 Landolt C ring test (eight orientations), a computerized and precise method widely employed in visual performance studies [

33]. Additionally, sustained attention and processing speed were assessed using a number proofreading tasks—a validated measure of cognitive performance commonly applied in lighting research [

34].

This study employed a three-parameter mixed model design, focusing on three variables: illuminance, color temperature, and horizontal blue light ratio, to investigate their effects on the human body. Regarding illuminance intensity, retinal and corneal illuminance are commonly used as standards for photobiological effects. The current relevant standards in China primarily refer to horizontal illuminance at desk height [

35]; therefore, in this experiment, horizontal illuminance at a desk height of 0.7 m was used as the reference standard, with additional measurements taken for vertical illuminance levels at a standing eye height of 1.2 m above the ground.

As shown in

Table 1, this experiment employed a three-factor, four-level orthogonal design (L16), which simplified the experimental setup by reducing the conditions from 64 to 16, while ensuring a balanced and interpretable estimation of main effects. The experimental conditions are outlined as follows:

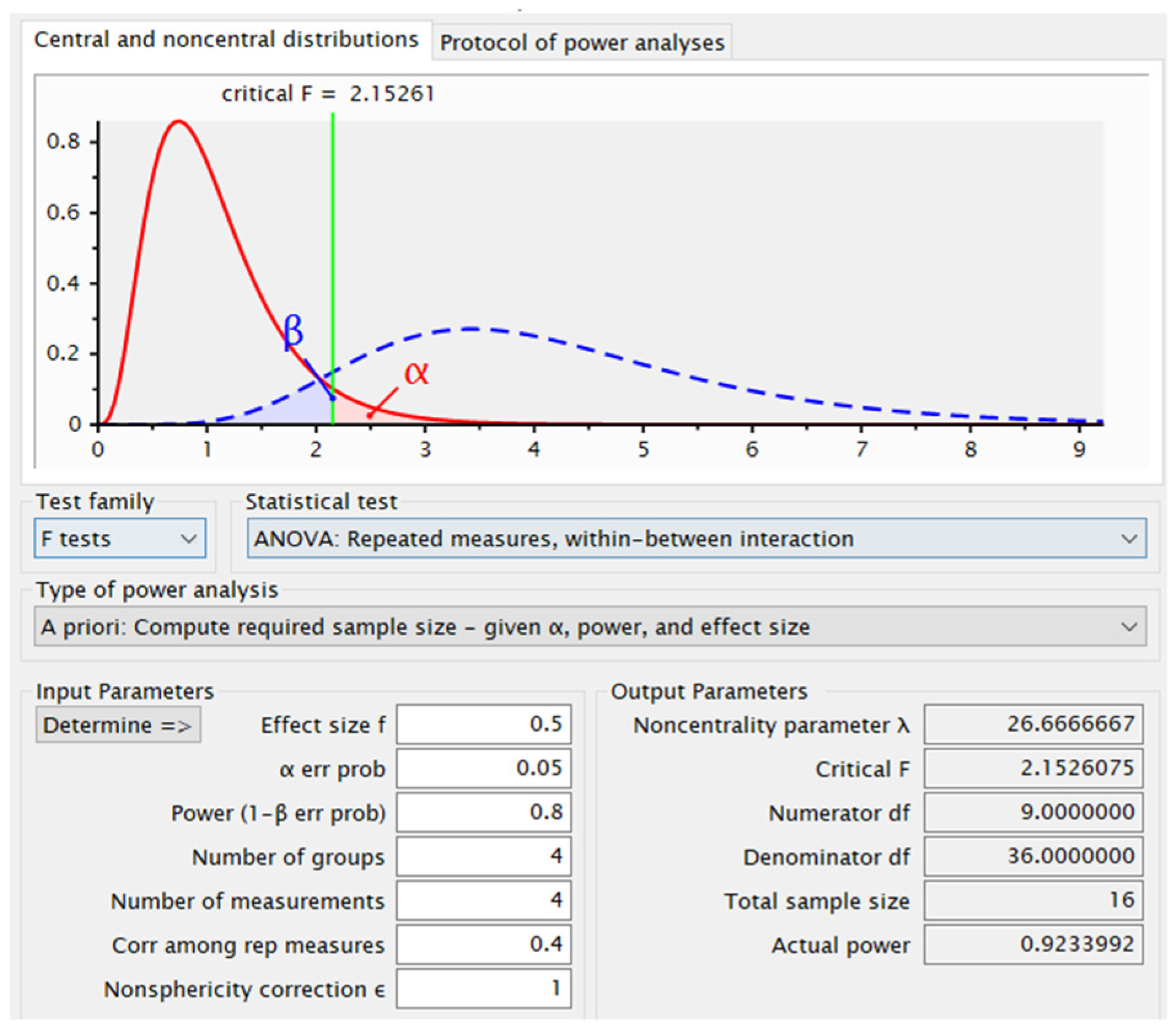

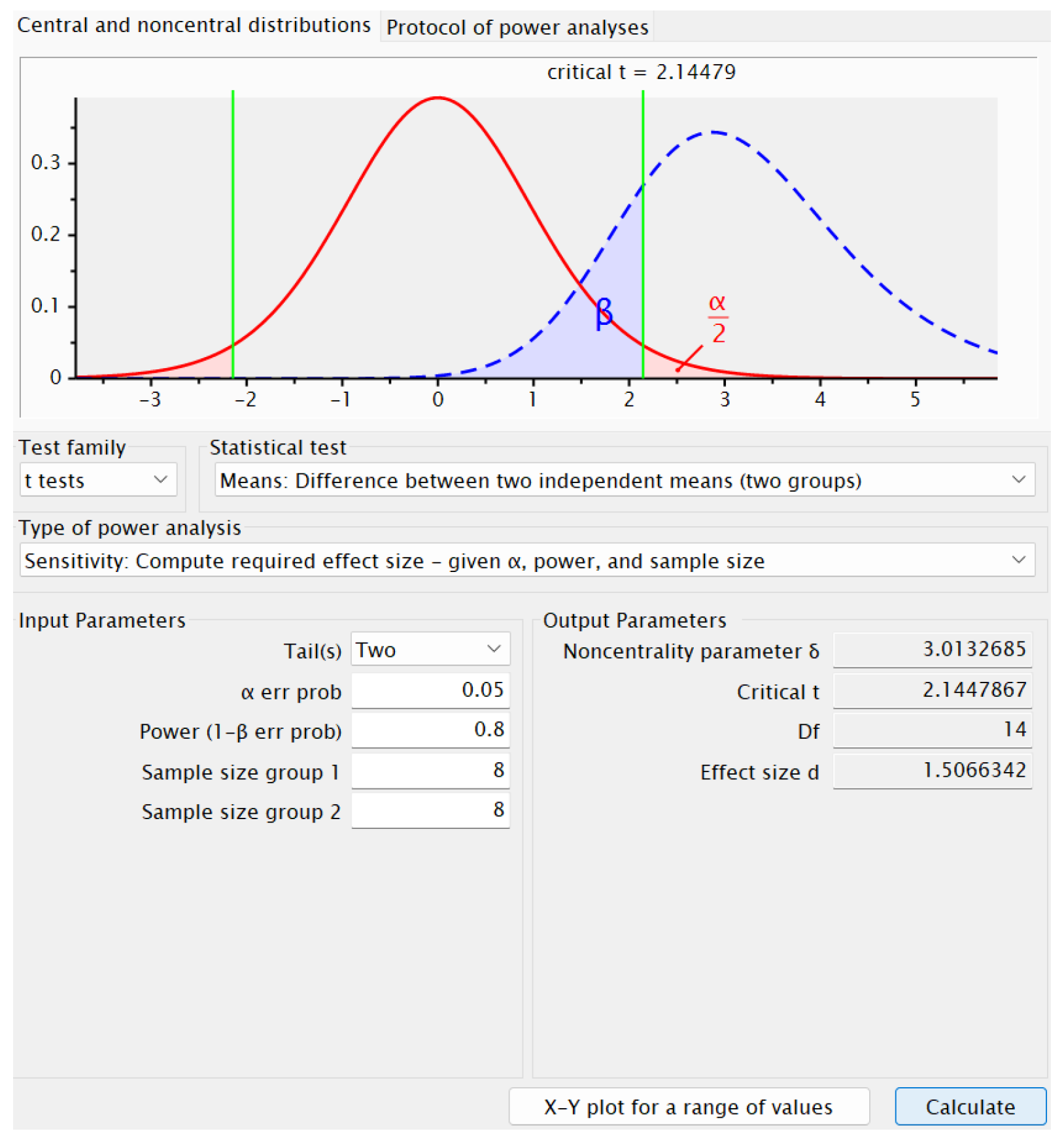

The sample size was statistically determined using G*Power version 3.1.9.7, with the statistical power set at 0.8 and a significance level of α = 0.05, following standardized protocols for behavioral and environmental studies. The calculation process involved specifying the experimental design and statistical model, selecting a one- or two-tailed test based on the research objectives, and determining the expected effect size from either a pilot experiment or from the previous literature [

36]. As shown in

Figure 5, the results indicated that a total of 16 participants were required for this experiment.

In recent years, excessive use of electronic devices has contributed to a high incidence of sleep disorders among young adults. To minimize the impact of individual differences in circadian rhythms and physiological indicators—which are closely tied to lifestyle and habits—this study recruited graduate students through open recruitment. This homogeneous population, with similar living environments and sleep–wake patterns, helps reduce variability in experimental data. All participants were rigorously screened normative sleepers, required to have maintained a consistent sleep schedule (00:00–08:00) with at least 8 h of nightly sleep over the preceding two weeks, with no history of shift work, transmeridian travel, substance use, or health or sleep disorders. During the study, alcohol consumption and other activities potentially affecting sleep or nighttime performance were prohibited. The final cohort consisted of 16 university students (8 male, 8 female), all with at least a bachelor’s degree, residing in controlled-environment dormitories as shown in

Figure 6. As summarized in

Table 2, participants were approximately 24 years old, with height and weight variations within an acceptable range.

- (1)

Illuminance Maps of Different Lighting Environments

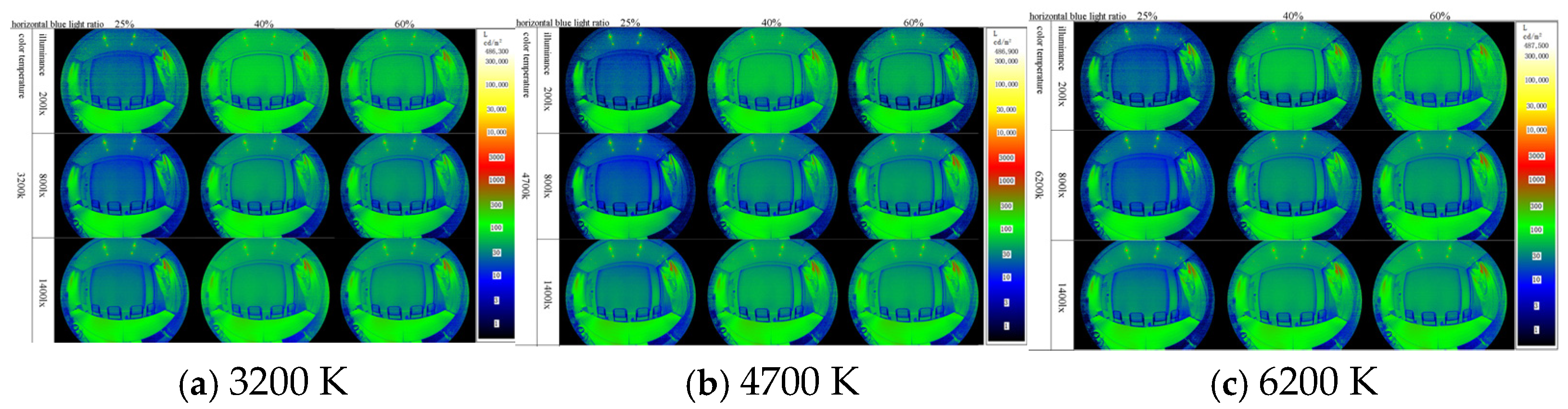

Figure 7.

The side brightness diagram of the experimental seat under different light environment.

Figure 7.

The side brightness diagram of the experimental seat under different light environment.

- (2)

Blue Light Hazard of Lighting Environments with Different Horizontal Blue Light Ratios

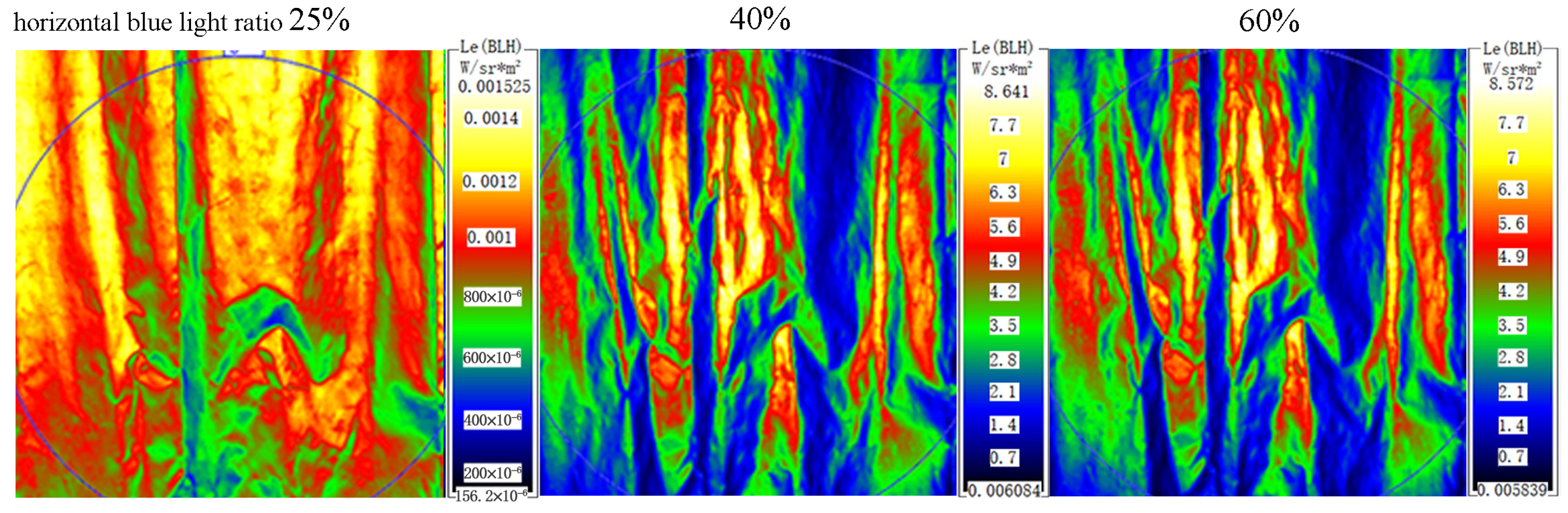

As shown in

Figure 8, the blue light hazard in lighting environments with different horizontal blue light ratios is below 100 in all cases, which falls within the non-hazardous range according to the blue light hazard classification in standard EN62471:2008 [

37].

Figure 8.

Blue light hazard measurement of experimental screen side under different levels of blue light proportional light environment.

Figure 8.

Blue light hazard measurement of experimental screen side under different levels of blue light proportional light environment.

- (3)

Spectra of Light Fixtures under Different Environments

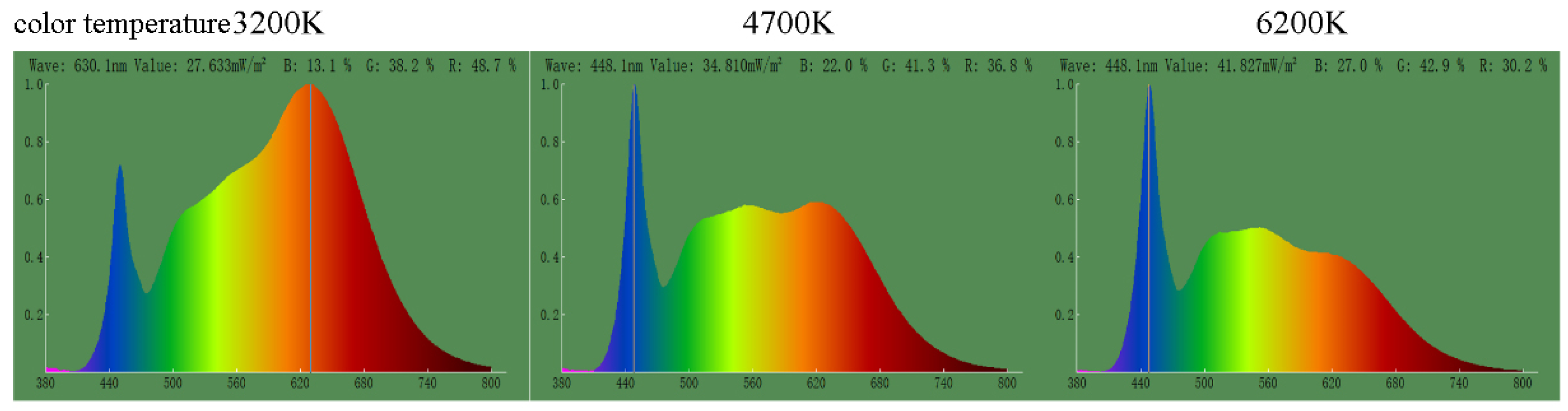

Figure 9.

Lamp spectra under different color temperature lighting environment (Source: Spectral Radiance Meter CL500).

Figure 9.

Lamp spectra under different color temperature lighting environment (Source: Spectral Radiance Meter CL500).

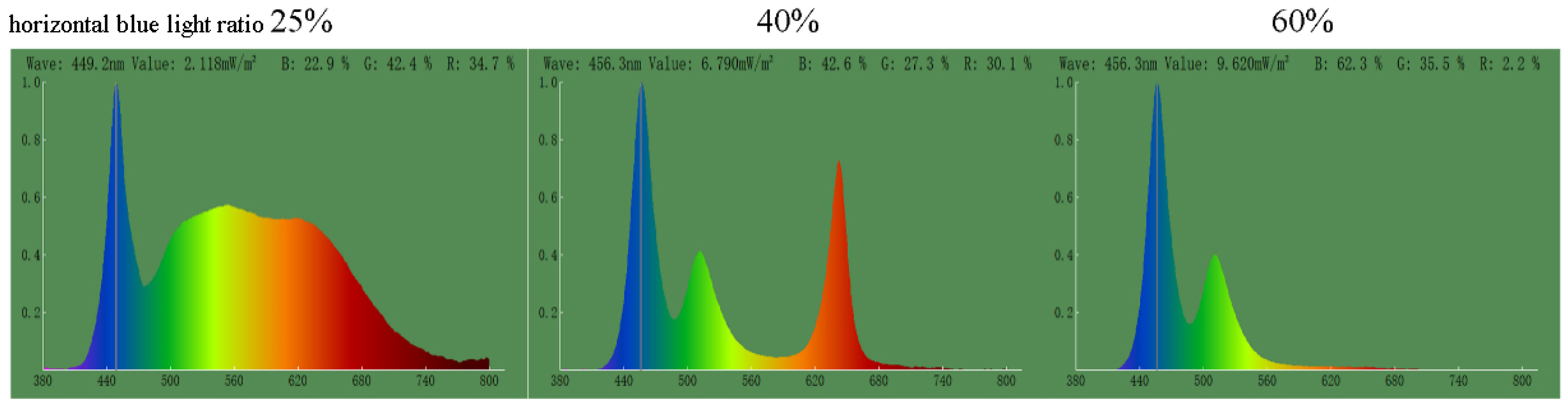

Figure 10.

Lamp spectra under different levels of blue light ratio light environment (Source: Spectral Radiance Meter CL500).

Figure 10.

Lamp spectra under different levels of blue light ratio light environment (Source: Spectral Radiance Meter CL500).

3. Experimental Data Analysis

This section aims to clarify the rationale and objectives of the data analyses. Laboratory simulations of residential environments were conducted to examine how color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio affect psychological, physiological, behavioral, and sleep-related responses. The analyses seek to determine which lighting parameters and interactions most strongly influence alertness, task performance, and sleep quality, and to reveal their underlying patterns.

Under lighting conditions meeting visual efficiency and photobiological safety, a mixed model and full factorial design were applied to evaluate changes in subjective alertness, cognitive performance, mental fatigue, sleep score, and melatonin secretion. Nonparametric and correlation analyses were then performed to identify significant trends, providing a quantitative basis for establishing relationships between lighting environments and human responses, and for developing the rhythmic lighting design framework.

In addition, post hoc multiple comparison tests (Tukey’s HSD and Bonferroni correction) were conducted following all ANOVAs to verify pairwise differences among lighting conditions. The detailed statistical outcomes are provided in

Supplementary Table S1, and corresponding effect size metrics (η

2 and Cohen’s d) were included to assess the magnitude of observed effects.

3.1. Psychological Quantities Analysis

- (1)

Mood State Evaluation

The evaluation of fatigue was an indicator that targets the participants’ conditions, aiming to avoid the influence of personal factors on the experimental results. Before each experiment, participants had to complete the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS), providing a subjective assessment of their fatigue and drowsiness levels based on their true feelings.

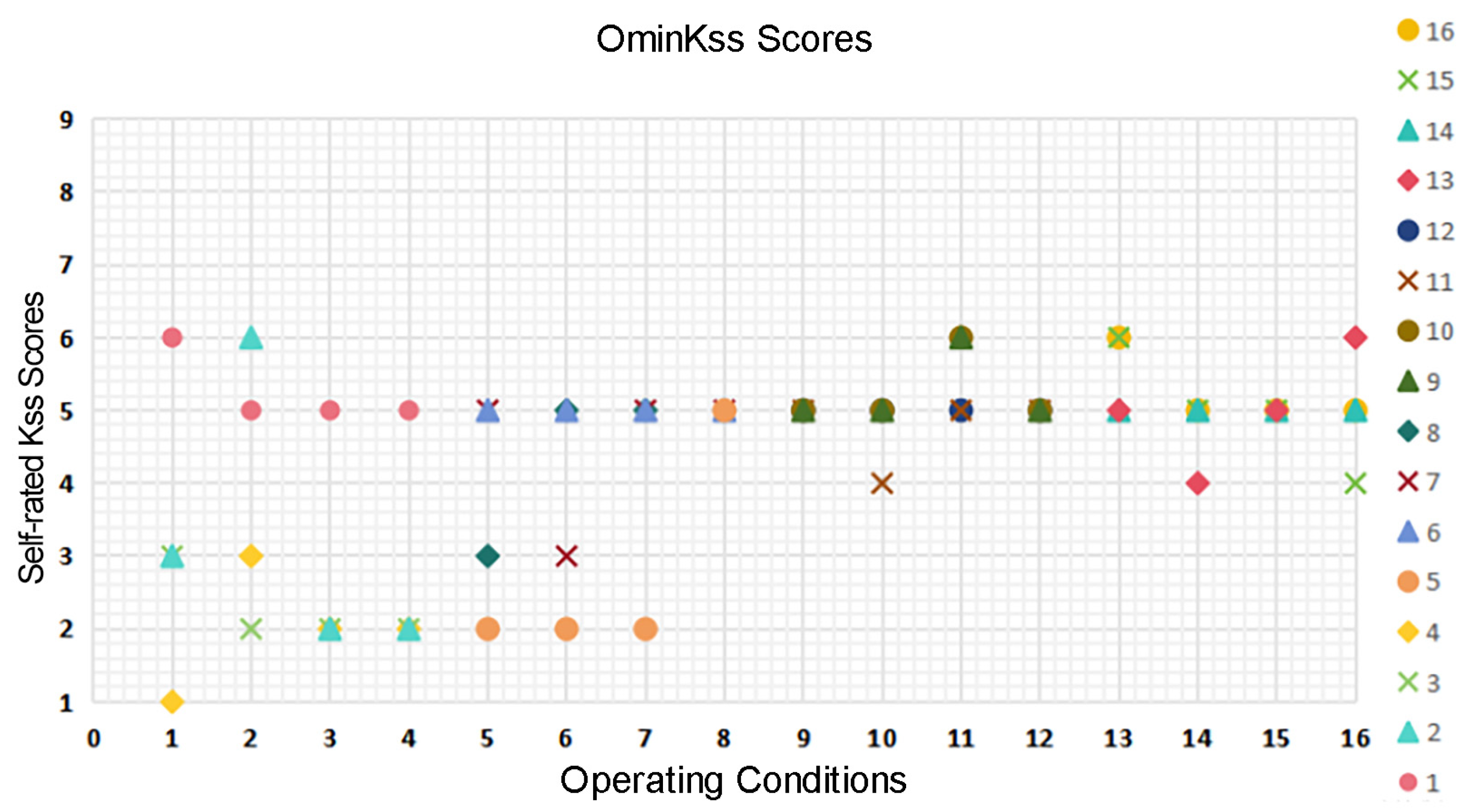

As shown in

Figure 11, the statistical evaluation of participants’ fatigue levels under different working conditions indicated that all participants rated their KSS scores between 2 and 5 before each working condition, reflecting a neutral to slightly positive state.

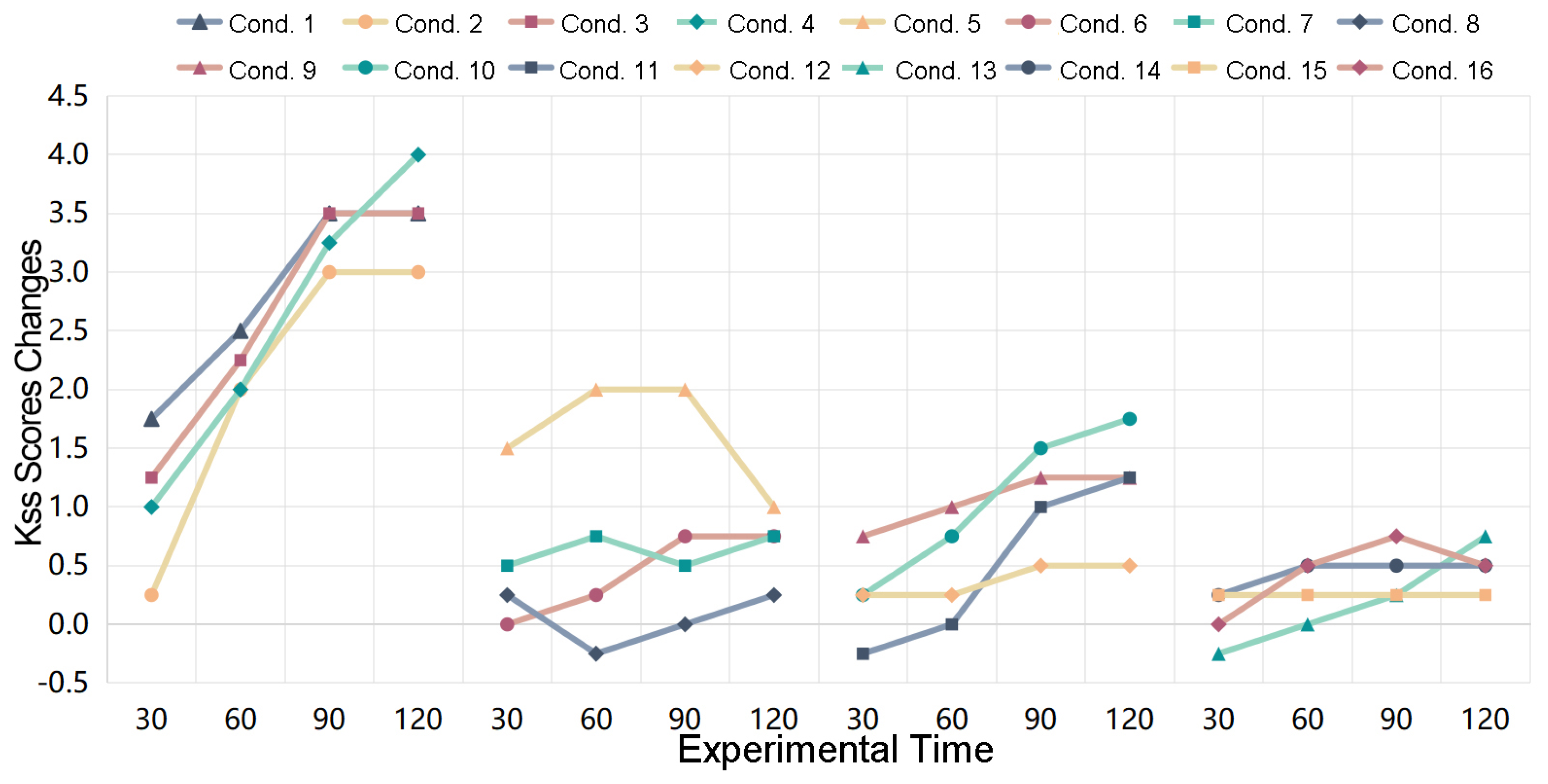

Figure 12 shows that under warm color temperature (3200 K) conditions, the mean change in KSS scores for working conditions 1–4 increased by more than three after the experiment compared to before, with the change in drowsiness being the most significant. Additionally, drowsiness levels continuously increased from 0 to 90 min into the experiment, stabilizing after 90 min. Under the same illuminance and horizontal blue light ratio, the changes in drowsiness levels under warm color temperature (3200 K) were also quite pronounced. Multiple comparisons of the changes in KSS scores revealed that color temperature exerted the strongest influence on drowsiness levels, followed by illuminance and then the horizontal blue light ratio.

- (2)

Light Comfort Evaluation

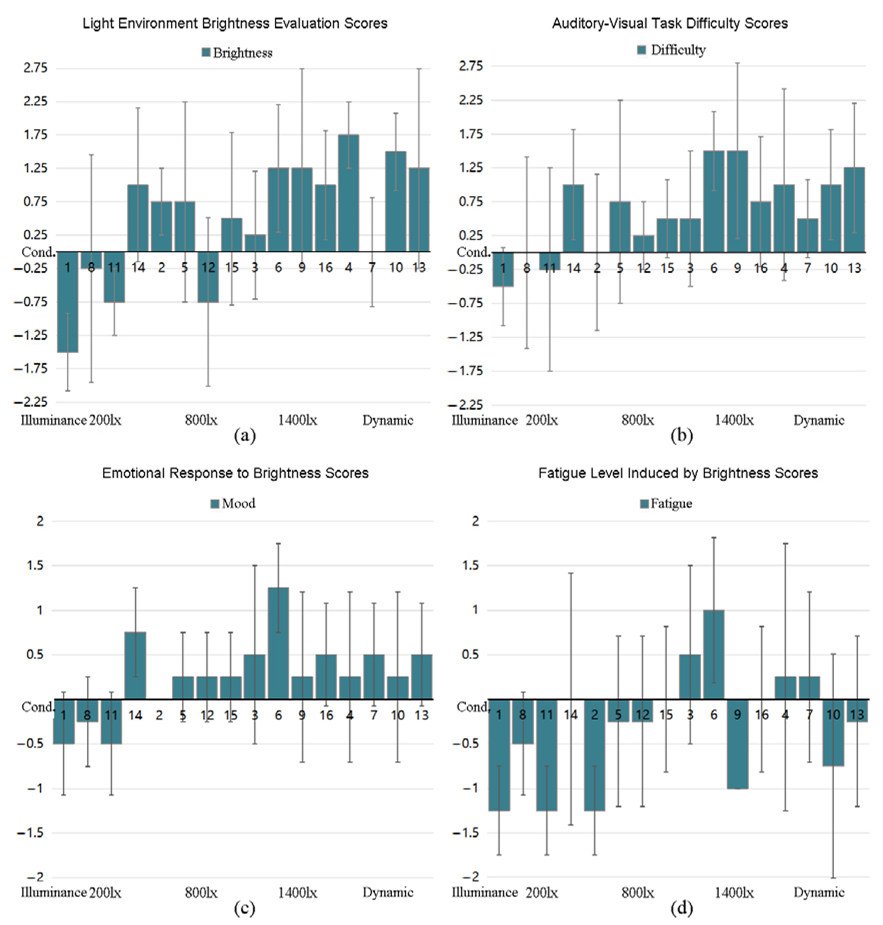

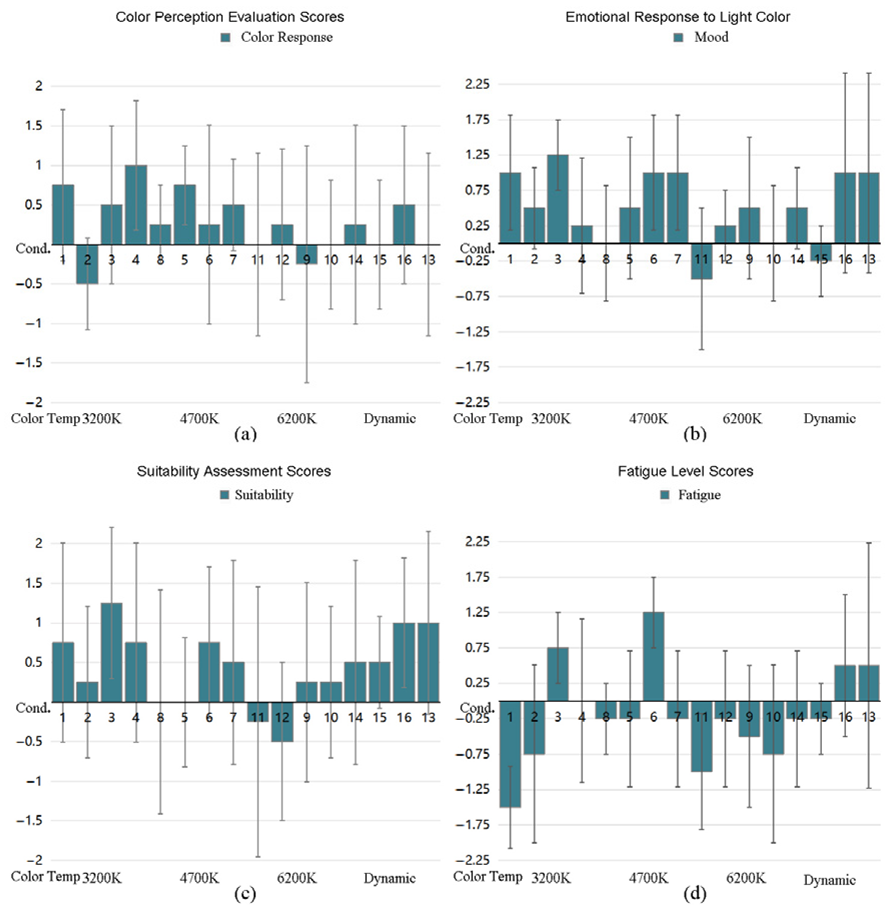

After each experimental condition, participants were asked to fill out a targeted questionnaire based on their subjective experiences, covering brightness and light color. The brightness section included four evaluation criteria: brightness (dim-bright), visual-auditory effort (strenuous-easy), visual-auditory mood (downcast-excited), and visual-auditory behavior (fatigued-alert). The questionnaire used a 7-point scale ranging from −3 to +3, with hostile to positive values representing varying response levels.

As shown in

Table 3, higher illuminance correlated with increased ratings for brightness, the ease of visual-auditory tasks, brighter mood, and fatigue levels, indicating a positive correlation. The light comfort evaluation for brightness achieved its best score under Condition 4 (3200 K color temperature, cycling illuminance), rated as the most comfortable. The ease of visual-auditory tasks was rated the best under Conditions 6 and 9 (1400 lx illuminance, 4700 K, and 6200 K color temperatures), being the most effortless. Brightness-related mood and fatigue were rated the most positively and least fatigued in Condition 6 (1400 lx, 4700 K color temperature).

In light color evaluation, higher color temperatures were associated with a more neutral subjective feeling, lower satisfaction, and reduced perceived suitability of the light color, showing a negative correlation. Continuous visual-auditory fatigue first decreased and then increased, with the lowest fatigue reported under the neutral tone (4700 K). The best evaluation for light color comfort occurred in Condition 4 (cycling illuminance, 3200 K color temperature). The light color mood and suitability were rated the highest in Condition 3 (1400 lx, 3200 K), with the most joyous mood and the most suitable light color. Environmental brightness-related fatigue was lowest in Condition 6 (1400 lx, 4700 K).

3.2. Physiological Analysis

- (1)

Heart Rate Variation Analysis

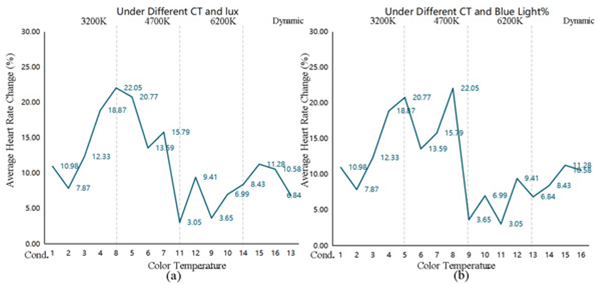

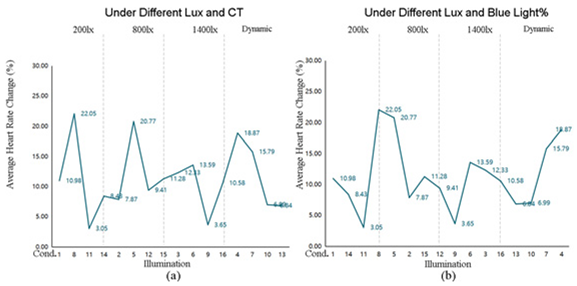

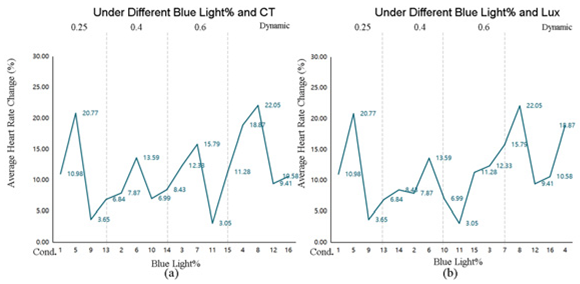

As shown in

Table 4, different color temperatures significantly impact the average heart rate change (

p = 0.000 < 0.01). The interaction terms of illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature, illuminance, and blue light ratio also significantly affected the average heart rate, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

Further analysis in conjunction with

Table 5 reveals that the average heart rate change under cycling color temperature conditions 9–12 was between 3.05% and 9.41%, significantly lower than in all other lighting conditions. The average heart rate change in other lighting conditions was evenly distributed between 6.84% and 22.05%, with relatively higher values in the 4700 K color temperature conditions 5–8, where the average heart rate was between 13.59% and 22.05%. The average heart rate reached its highest point in condition 9 under 4700 K and 200 lx lighting; it reached its lowest in condition 13 under 6200 K color temperature and 200 lx illuminance.

- (2)

Systolic and Diastolic Pressure Analysis

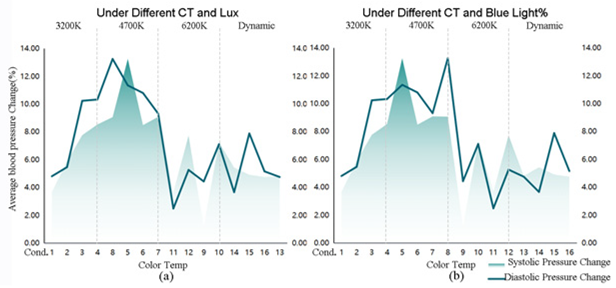

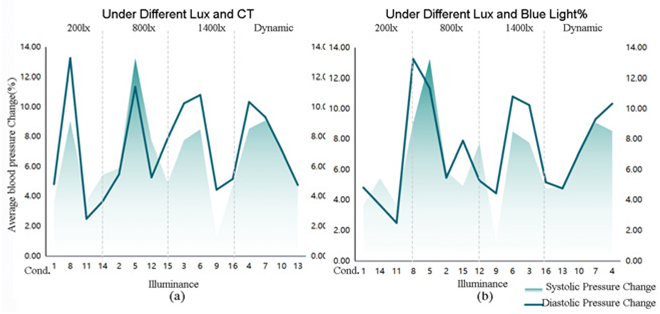

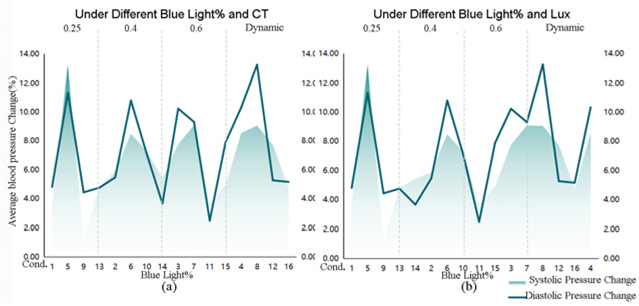

As shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7, color temperature and illuminance significantly affected the average diastolic and systolic pressures change(

p = 0.000 < 0.01). The interaction terms of illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature, illuminance, and blue light ratio also significantly affected the average diastolic and systolic pressures, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

As shown in

Table 8, analysis of the average blood pressure change under different lighting conditions showed that the average diastolic pressure change was highest in condition 8 at 4700 K, 200 lx, and cycling blue light ratio; it was lowest in condition 11 under 6200 K, 200 lx, and 60% blue light ratio. The average systolic pressure was highest in condition 5 at 4700 K, 800 lx, and 25% blue light ratio; it was lowest in condition 9 under 6200 K, 1400 lx, and 25% blue light ratio.

- (3)

Physiological Value Analysis of Good Conductance

Using a sub-health analysis instrument, the good conductance physical fitness value evaluates average physical fitness, resistance, neural activity, and physiological functions. A physical fitness value between 25 and 55 is considered normal; values greater than 55 indicate vigorous mental activity and easy depletion of energy; values between 20 and 24 indicate slight fatigue; values between 17 and 19 indicate moderate fatigue. Values below 17 indicate severe fatigue and decreased body energy.

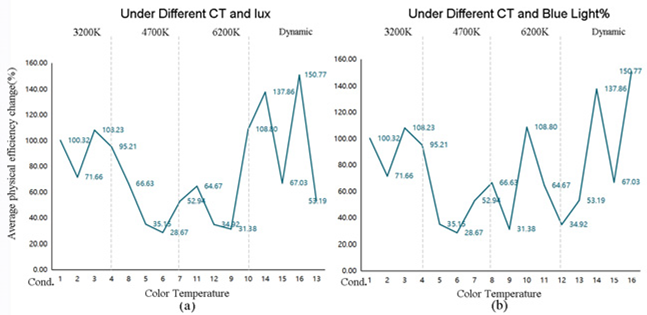

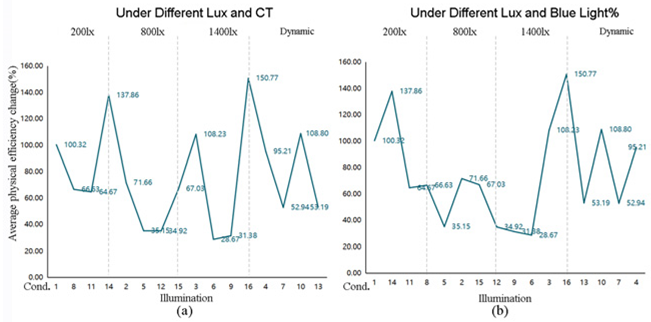

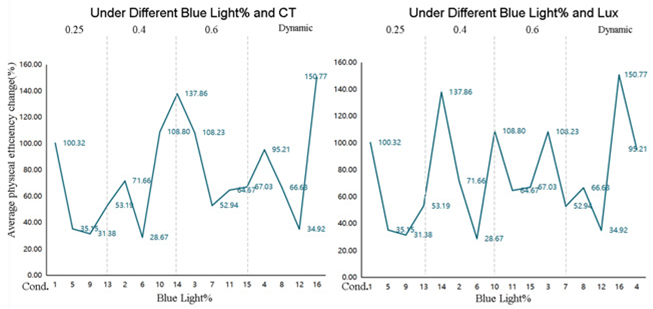

As shown in

Table 9, the interaction term of color temperature and illuminance and blue light ratio significantly affected the average good conductance physical fitness, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

As shown in

Table 10, further analysis of the average good conductance physical fitness under different lighting conditions showed that the average fitness value in the 4700 K color temperature conditions 5–8 was between 28.67% and 52.94%, significantly lower than in other lighting conditions where the average fitness value was between 31.38% and 150.77%. The average fitness values under cycling color temperature conditions 14 and 16 were 137.86% and 150.77%, respectively, relatively higher than in other lighting conditions. The lowest fitness value occurred in condition 6 under 4700 K, 1400 lx, and 40% horizontal blue light ratio; the highest was in condition 16 under cycling color temperature, cycling illuminance, and cycling horizontal blue light ratio.

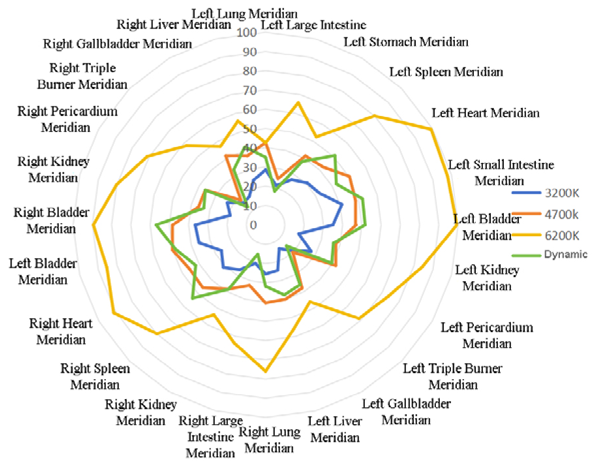

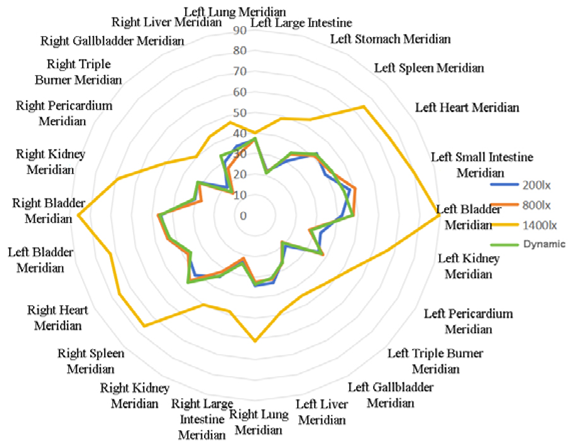

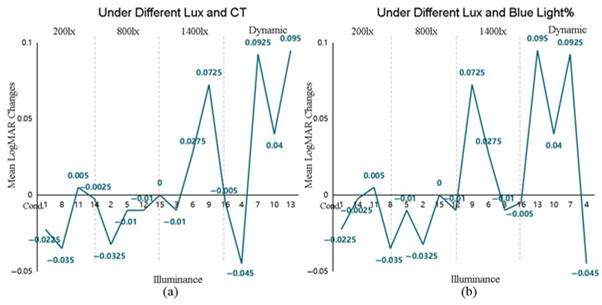

As shown in

Table 11, Analysis of the radar chart showing the average values of 24 meridians under different color temperatures, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratios indicated that the effects on the body’s good conductance response were most pronounced under the 6200 K, 1400 lx, and 60% horizontal blue light ratio conditions, which were detrimental to physiological health. The order of impact from greatest to least was color temperature, horizontal blue light ratio, and illuminance.

3.3. Task Performance Analysis

This experiment employed the visual function software FrACT (

https://michaelbach.de/fract/) for measurements to determine the optimization of various behavioral health lighting conditions in existing living spaces. Concurrently, an occupational scale was used to evaluate the experimental results, providing optimized reference values for refining pre-sleep spatial activities.

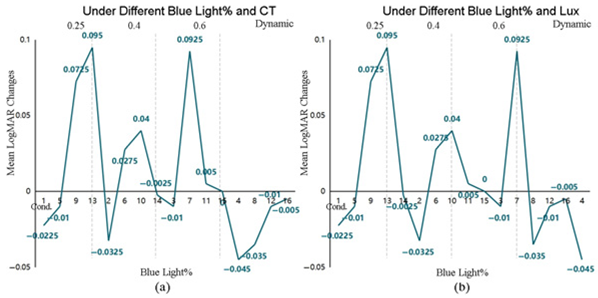

3.3.1. Acuity c Evaluation of Visual Clarity

As shown in

Table 12, color temperature and illuminance significantly affected the 120 LogMAR values (

p = 0.000 < 0.01). The interaction terms of color temperature and blue light ratio, illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature, illuminance, and blue light ratio also significantly influenced the 120 min LogMAR values, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

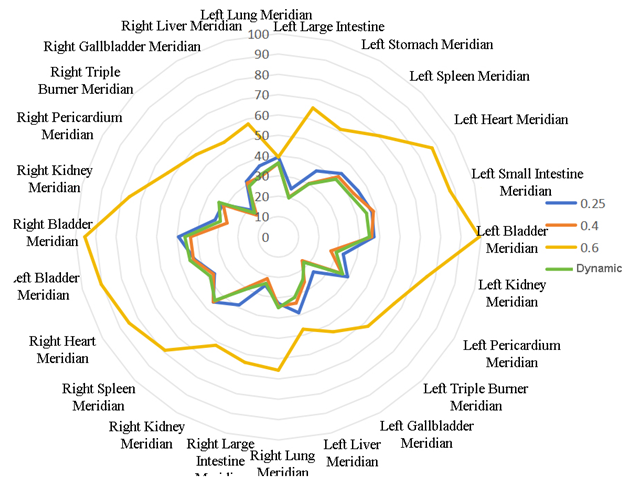

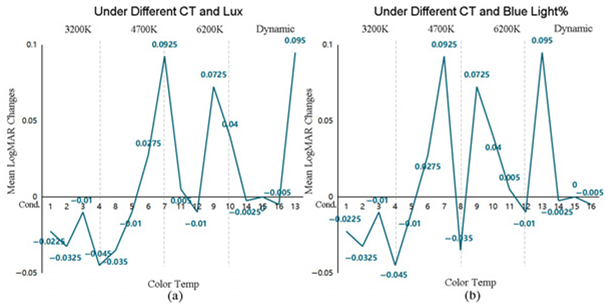

As shown in

Table 13, further analysis of the 120 LogMAR values under different lighting environments revealed that the 120 LogMAR values for the 3200 K condition in environments 1–4 ranged between −0.045 and −0.01. In contrast, other lighting environments showed an uneven distribution between −0.035 and 0.095, significantly lower than other conditions. Under the 200 lx and 800 lx illumination conditions in environments 1, 2, 5, 8, 11, 12, 14, and 15, the 120 LogMAR values ranged between −0.035 and 0.005, relatively lower than other conditions. The lowest 120 LogMAR value occurred in condition 4, characterized by 3200 K color temperature, cycling illuminance, and cycling horizontal blue light ratio; conversely, the highest value is found in condition 13, which features cycling color temperature, cycling illuminance, and a 25% blue light ratio.

According to the range analysis presented in

Table 14, color temperature exerted the strongest influence on the 120 LogMAR values, followed by the horizontal blue light ratio and then illuminance. The optimal lighting environment for achieving the best 120 LogMAR value is at a color temperature of 6200 K, with cycling illuminance and a horizontal blue light ratio of 60%.

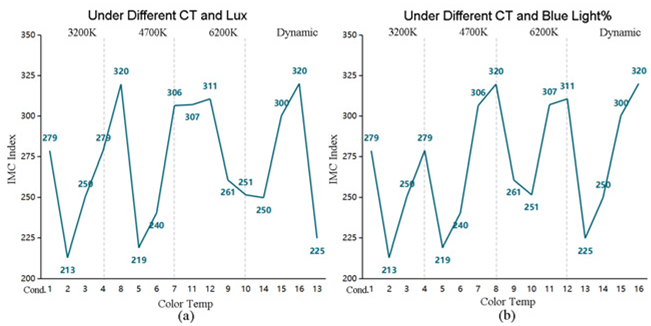

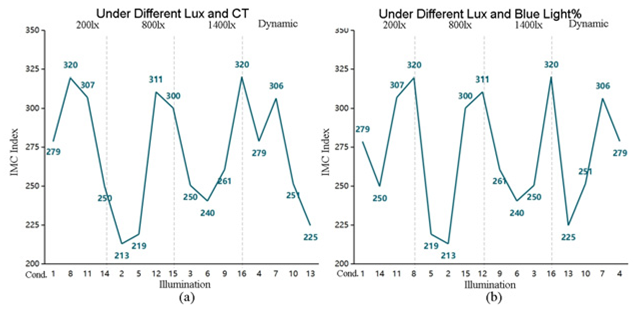

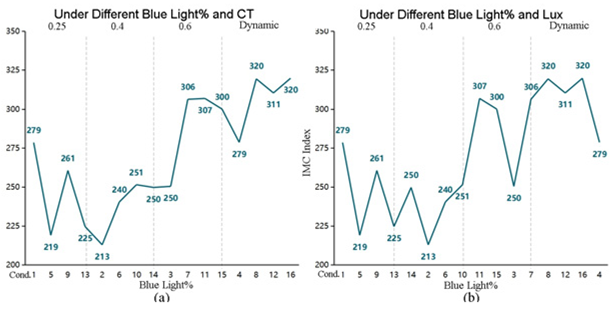

3.3.2. Evaluation of Task Performance

As shown in

Table 15, color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio significantly affected the IMC index values (

p = 0.000 < 0.01). The interaction terms of color temperature and illuminance, color temperature and blue light ratio, illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature, illuminance, and blue light ratio also significantly influenced the IMC index values, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

As shown in

Table 16, further analysis of IMC index values under different lighting environments revealed that the IMC index values for conditions 4, 8, 12, and 16, characterized by cycling horizontal blue light ratios, ranged between 279 and 320, which is significantly higher than those in other lighting environments that ranged from 213 to 307. The lowest IMC index value occurred in condition 2, with a 3200 K color temperature, 800 lx illumination, and a 40% horizontal blue light ratio; conversely, the highest value was found in condition 8, featuring a 4700 K color temperature, 200 lx illumination, and a cycling horizontal blue light ratio.

According to the range analysis presented in

Table 17, the horizontal blue light ratio exerted the strongest influence on the IMC index values, followed by illuminance and then color temperature. The optimal combination for achieving the best IMC index value was a color temperature of 6200 K, an illuminance of 200, and a cycling horizontal blue-light ratio.

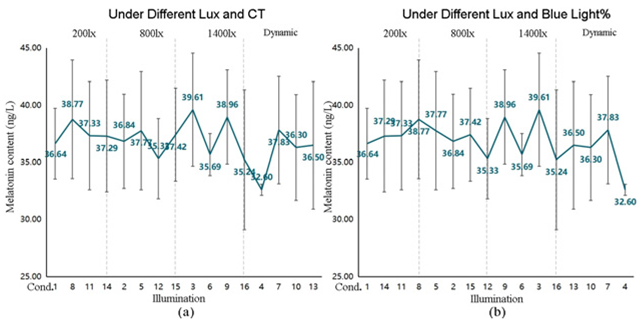

3.4. Analysis of Sleep Evaluation

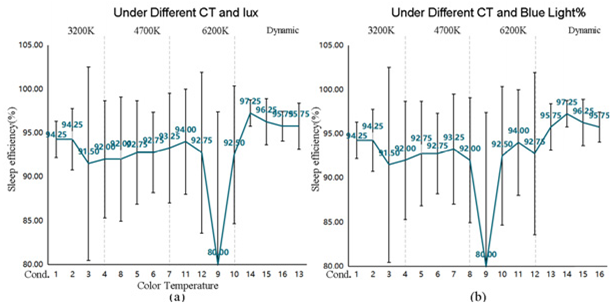

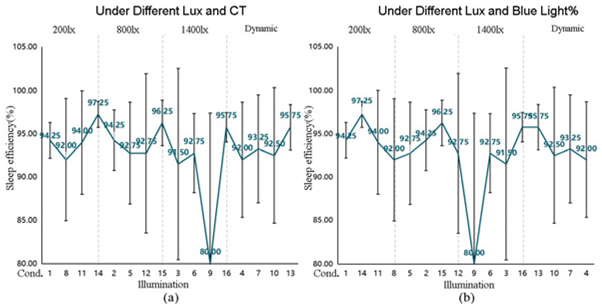

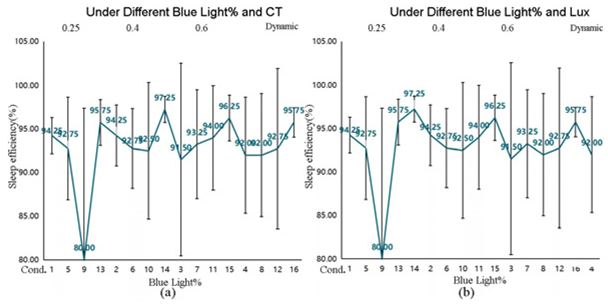

3.4.1. Analysis of Sleep Efficiency

Sleep efficiency is defined as the ratio of effective sleep duration to the total time spent in bed, reflecting the proportion of wakefulness to sleep during this time. This indicator is commonly used to assess the risk of sleep disorders, with a normal sleep efficiency above 85%.The means and standard deviations of sleep efficiency evaluation under different conditions are as shown in

Table 18.

As shown in

Table 19, the analysis of the mean sleep efficiency across all conditions using the range method indicated that color temperature exerted the strongest influence on sleep efficiency, followed by illuminance and then the horizontal blue light ratio. According to the range method, the optimal combination for achieving the best sleep efficiency was a cycling color temperature, an illuminance of 200, and a horizontal blue-light ratio of 40.

The results of the variance analysis presented in

Table 20 indicate that color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio significantly affected sleep efficiency (

p = 0.000 < 0.01), demonstrating a primary effect. The interaction terms of color temperature and illuminance, color temperature and blue light ratio, illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature, illuminance, and blue light ratio also significantly influenced sleep efficiency, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

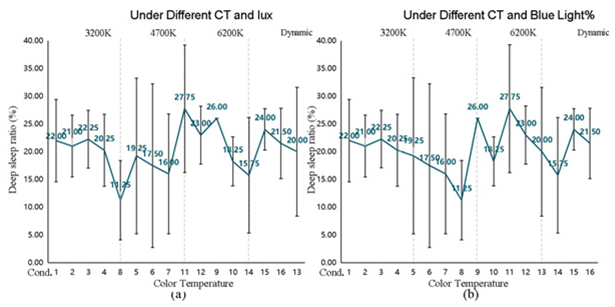

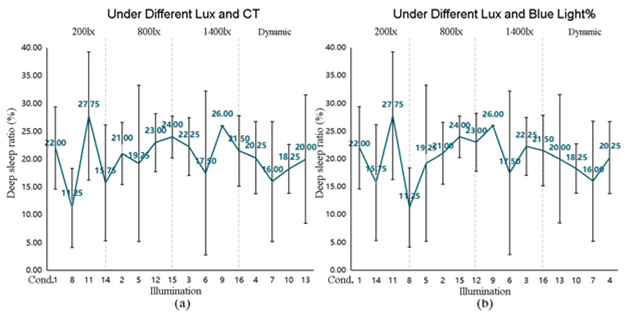

3.4.2. Analysis of Deep Sleep Ratio

The means and standard deviations of deep sleep ratio under different conditions are as shown in

Table 21.

As shown in

Table 22, calculation of the mean deep sleep ratio across all conditions and its analysis using the range method determined that color temperature exerted the strongest influence on the deep sleep ratio, followed by the horizontal blue light ratio and then illuminance. The recommended optimal lighting environment parameters are a color temperature of 6200 K, an illuminance of 800 lx, and a horizontal blue light ratio of 60%.

As shown in

Table 23, the results of the variance analysis indicate that color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio significantly affected the deep sleep ratio (

p = 0.000 < 0.01), demonstrating a primary effect. The interaction term of color temperature and illuminance and blue light ratio also significantly impacted the deep sleep ratio, indicating an interaction effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

3.4.3. Analysis of Sleep Score

According to the sleep quality recommendations from the American Sleep Foundation, the sleep score is calculated based on six factors: total sleep duration, sleep onset time, sleep latency, wakefulness duration, deep sleep duration, and morning stability. In this scoring system, the total score for effective nighttime sleep duration accounts for 50%, while sleep latency and awakenings each account for 15%. Morning stability contributes 10%, and deep sleep duration and onset time contribute 5% each [

38].

- (1)

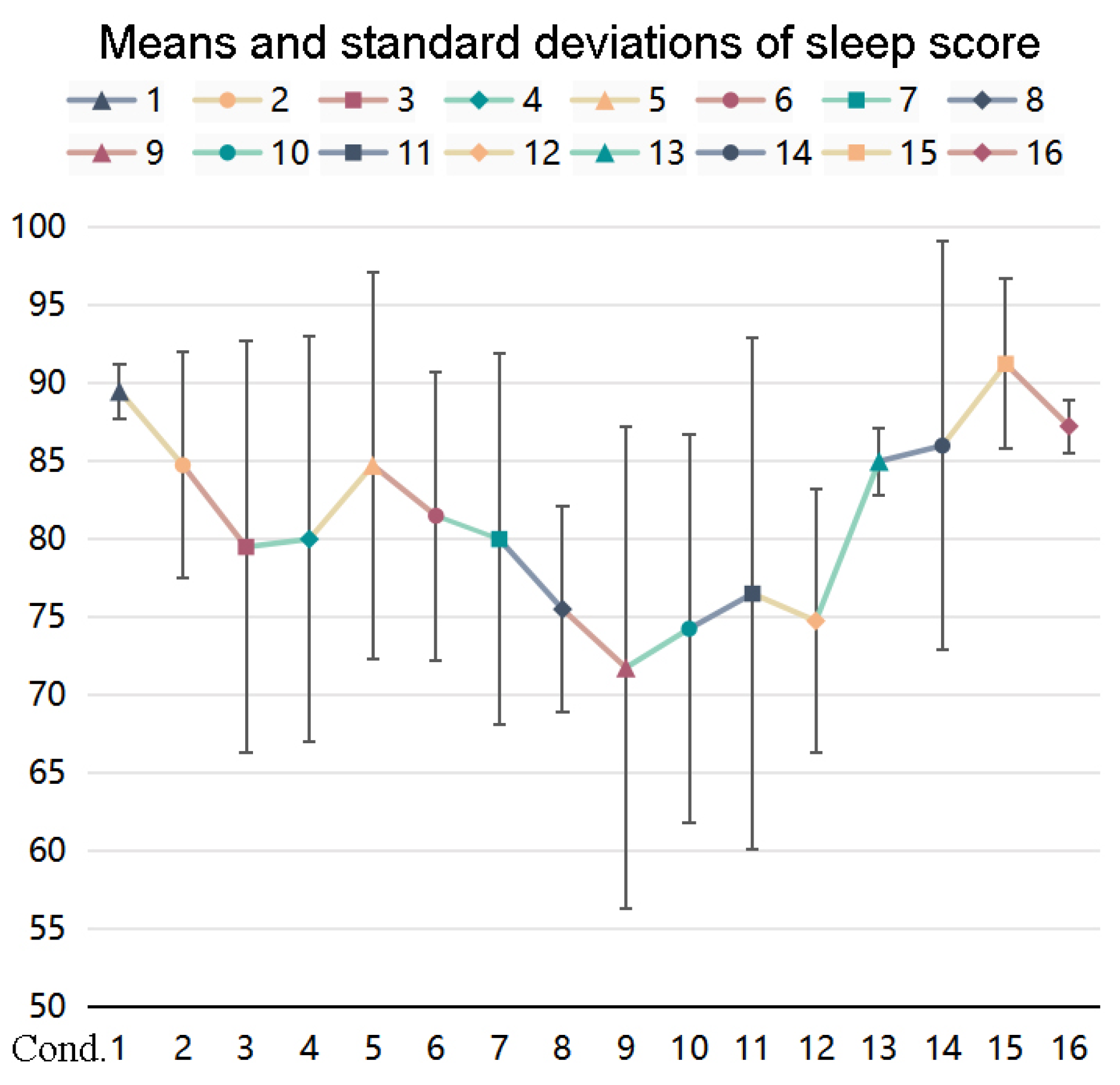

Analysis of Sleep Score

Figure 13 shows the mean and standard deviation of sleep scores under different conditions, arranged in ascending order of color temperature and horizontal blue light ratio. It can be observed that, under low and medium color temperature lighting environments, the average sleep score decreased as the color temperature increased, whereas, in high-level and cycling color temperature lighting conditions, the average sleep score increased with rising color temperature.

By calculating the mean sleep score across all conditions and analyzing it using the range method, the order of influence on sleep score was determined, as presented in

Table 24, to be color temperature, followed by illuminance and then the horizontal blue light ratio. The analysis revealed that the sleep score gradually declined with increasing color temperature, achieving the highest score in cycling color conditions. The recommended optimal lighting environment parameters were cycling color temperature, illuminance of 800 lx, and a horizontal blue light ratio of 25%.

As shown in

Table 25, The results indicate that color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio significantly affected the sleep score, demonstrating a primary effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01). The interaction terms of color temperature and illuminance, color temperature and blue light ratio, illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature, illuminance, and blue light ratio also significantly impacted sleep score, indicating interaction effects (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

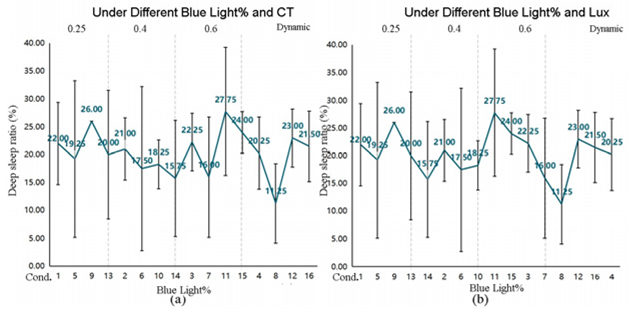

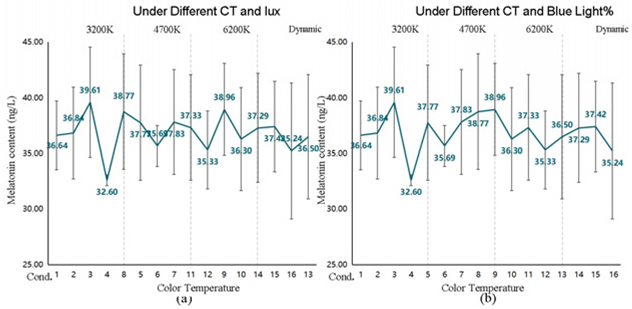

- (2)

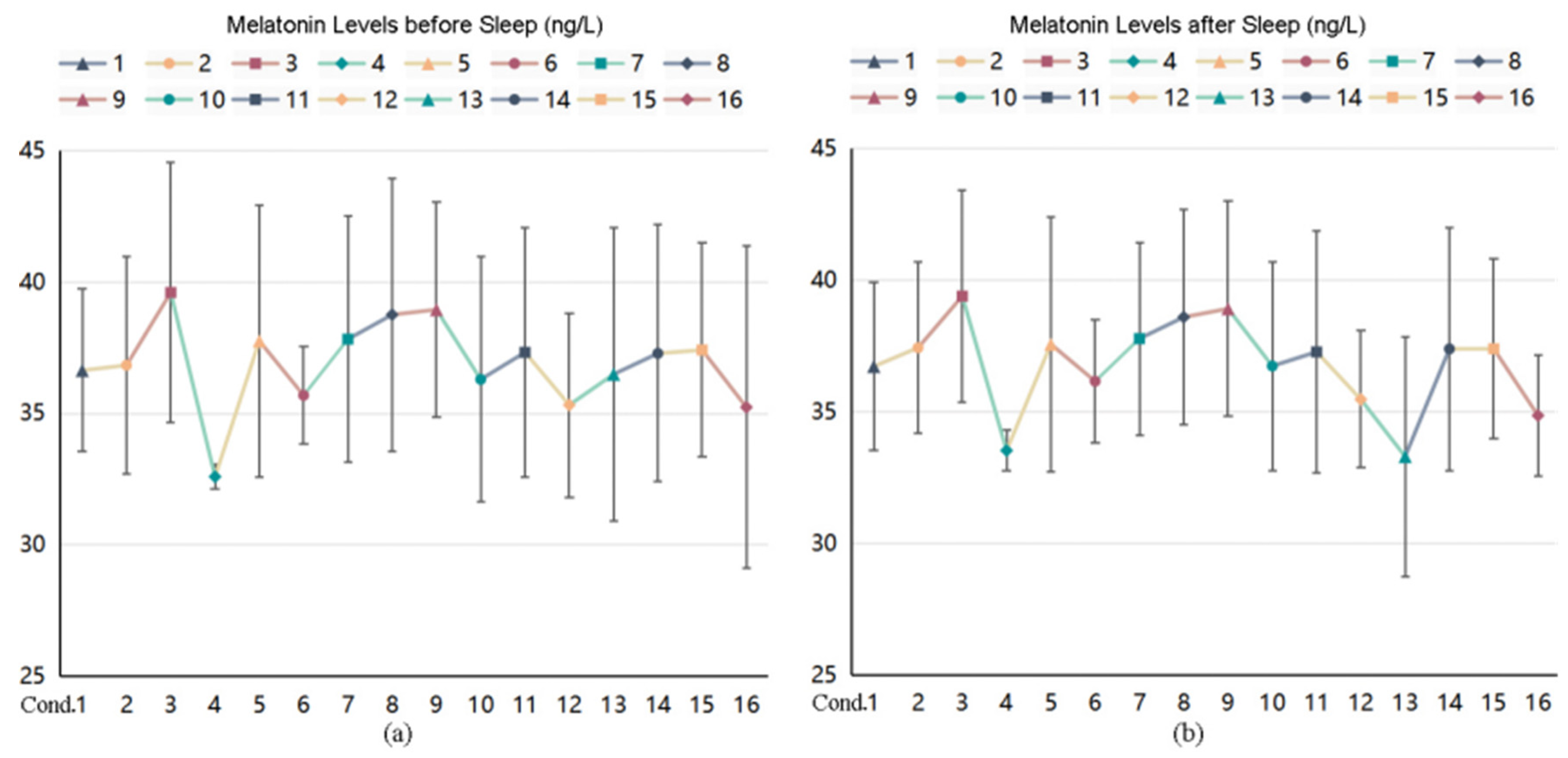

Analysis of Melatonin Levels Before and After Sleep

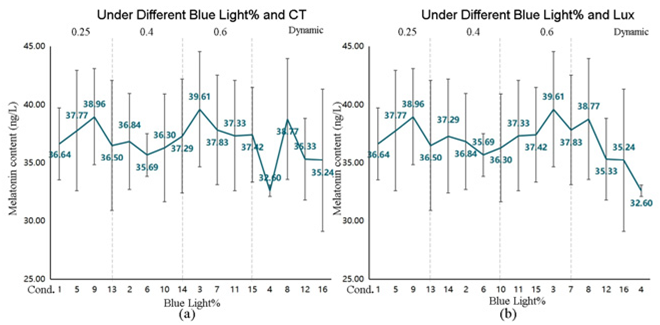

The secretion of melatonin from the pineal gland had a particular influence on inducing sleepiness in humans, where the level of melatonin secretion was inversely proportional to the level of alertness. Changes in melatonin levels can describe whether a person is in a state of wakefulness or drowsiness. In this experiment, saliva samples were collected from participants twice daily to detect melatonin levels and plot their trend curves, as shown in

Figure 14. Except for condition 13, the experimental results indicate a similar trend in melatonin levels before and after sleep. Notably, due to the uniqueness of condition 13, the changes in melatonin levels show significant deviation from other data, and it can be regarded as an outlier.

Analysis of melatonin content before bedtime under different conditions is shown in

Table 26. By calculating the mean pre-sleep melatonin levels across all conditions and analyzing them using the range method, the order of influence on pre-sleep melatonin content was determined, as presented in

Table 27, to be horizontal blue light ratio, followed by illuminance and then color temperature. The lighting environment with the highest pre-sleep melatonin content is a color temperature of 4700 K, illuminance of 200 lx, and a horizontal blue light ratio of 60. In contrast, the condition with the lowest pre-sleep melatonin content was a color temperature of 3200 K, cycling illuminance, and cycling horizontal blue light ratio.

As indicated by the results of the variance analysis presented in

Table 28, color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio significantly affected pre-sleep melatonin levels, demonstrating a primary effect (

p = 0.000 < 0.01). The interaction terms of color temperature and illuminance, color temperature and blue light ratio, illuminance and blue light ratio, and color temperature and illuminance and blue light ratio also significantly affected pre-sleep melatonin levels, indicating interaction effects (

p = 0.000 < 0.01).

4. Discussion

This article starts from the perspective of a healthy lighting environment in residential spaces. It explores the effects of different lighting conditions—color temperatures (3200 K, 4700 K, 6200 K, cycling), illuminance levels (200 lx, 800 lx, 1400 lx, cycling), and horizontal blue light ratios (25%, 40%, 60%, cycling)—on psychological, physiological, efficiency, and sleep factors through subjective evaluations and objective measurements. Research data indicate that lighting parameters significantly affect participants’ psychological states. Under warm color temperature (3200 K) conditions, drowsiness significantly increases. The analysis suggests that this is due to people’s heightened sensitivity to colors caused by color temperature, with warm-toned lighting more readily inducing feelings of drowsiness. Thus, neutral color temperatures, high illuminance, and high horizontal blue light ratio fixtures can be employed to suppress drowsiness. Suggestions on the selection of healthy light intervention parameters is shown in

Table 29.

Our findings elucidate the targeted applications of specific lighting parameters and provide practical guidance for human-centric lighting design. High illuminance combined with low color temperature (1400 lx, 3200 K) elicited the greatest comfort and positive affect, suggesting its suitability for restorative and social spaces, such as medical facilities, cafés, and living areas, where a warm and relaxing ambience is desired. Conversely, high illuminance with high color temperature (1400 lx, 6200 K) increased physiological arousal, reflected by elevated heart rate and galvanic skin response, indicating its relevance for alertness-demanding environments, including offices, classrooms, and industrial workspaces.

For task performance, lighting with cycling modulation of blue-light ratios effectively enhanced visual clarity and sustained attention, supporting its use in work and study environments that aim to simulate the spectral characteristics of natural daylight. Incorporating gradual changes in color temperature across the workday may further stabilize circadian rhythms and reduce visual fatigue.

Regarding residential settings, the optimal configuration for sleep and relaxation involved cycling color temperature with medium illuminance and a low blue-light ratio (800 lx, 25%). This lighting scheme can be implemented in bedrooms and evening living spaces to promote melatonin production and support healthy sleep patterns.

Overall, this study establishes an evidence-based framework for human-centric lighting, advocating context-specific prescriptions—such as warm, low-blue lighting for residential settings and cycling, high-blue lighting for workplaces—to enhance well-being, comfort, and performance across diverse environments.

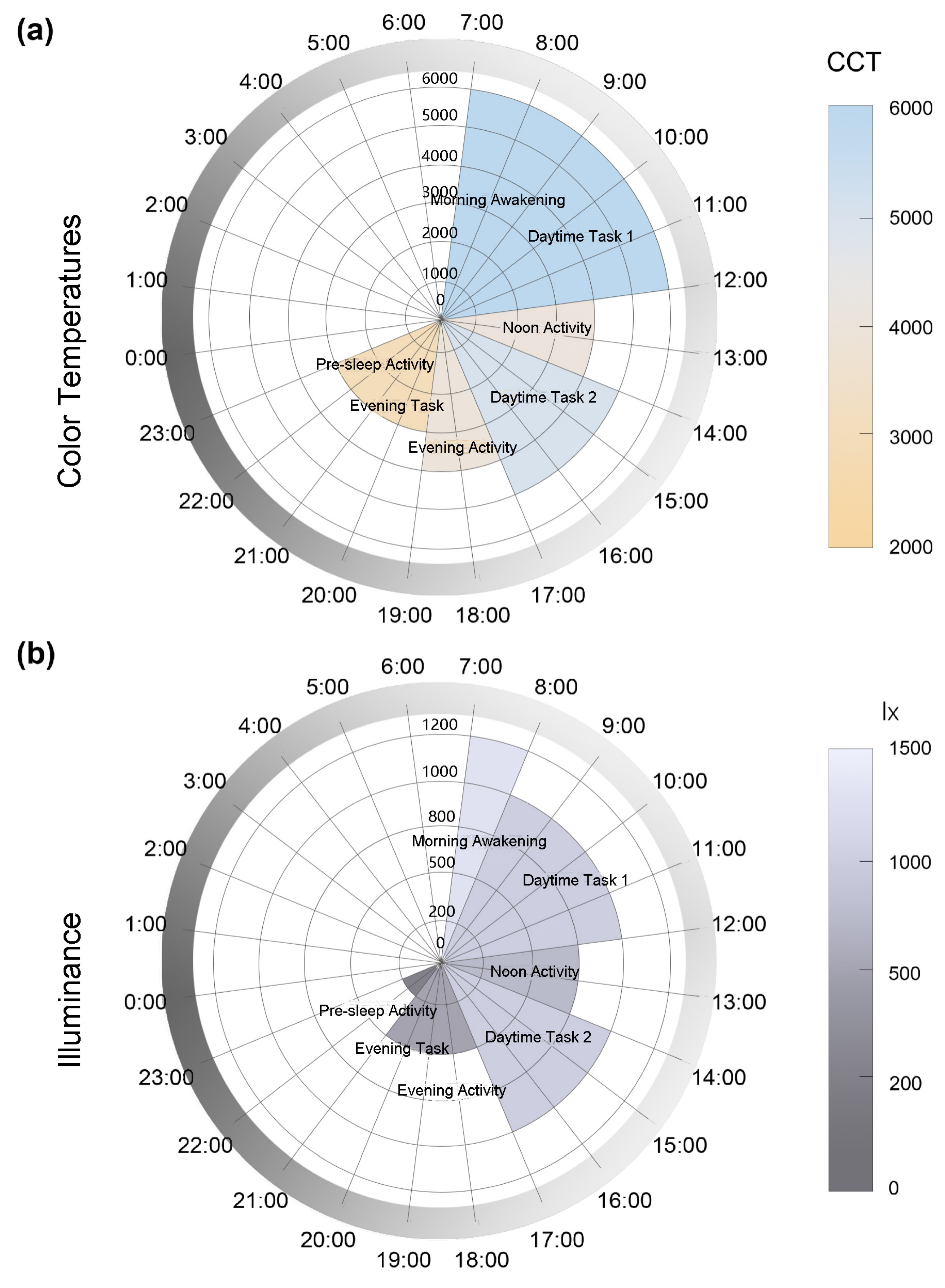

As shown in

Table 30 and

Figure 15, this approach is consistent with the CIE’s concept of “human-centered dynamic lighting,” which emphasizes adjusting illuminance and color temperature throughout the day to align with human circadian rhythms. This approach refers to the real-time adjustment and variation in illuminance or color temperature according to a predetermined pattern at different times of the day, to optimize and improve aiming to optimize and improve individuals’ physical and mental functions. This study applies dynamic lighting technology to design and implement a basic temporal rhythm lighting scheme based on the daily activity schedules of most people, taking into account various factors. The scheme includes eight lighting scene modules to address user issues related to daytime emotions, work efficiency, and sleep quality while enhancing cognitive performance. In practice, it has demonstrated specific effective results; however, adjustments must be made based on actual conditions during application.

This study partially validates previous research indicating that nighttime light intensity inhibits melatonin secretion [

39]. Furthermore, it clarifies that factors such as color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio collectively influence melatonin secretion in residential lighting environments, with pre-sleep melatonin levels being significantly affected by the horizontal blue light ratio. This provides a new perspective for more precisely regulating lighting environments to promote sleep. Additionally, Legates’ research found that light directly impacts people’s psychology and behavior [

40]. Through evaluations of mood states and lighting comfort among subjects in different lighting environments, this study explicitly highlights the subjective differences in participants’ experiences under various combinations of color temperature and illuminance, enriching the research on the relationship between lighting environments and psychology.

However, this study also has some limitations. For instance, the experimental subjects were primarily students, and different age groups may respond differently to lighting environments regarding physiological and psychological effects. Consequently, the findings may not be universally applicable to all populations. Moreover, the experiments were conducted in simulated residential spaces, which differ from real living environments. Factors such as spatial layout and furniture arrangement can also affect the lighting environment in practical life. Additionally, human activities in residential spaces are more diverse, with longer and more complex exposure times to light in daily life. A further limitation concerns the sample size. As shown in

Figure 16, A post hoc sensitivity power analysis (G*Power 3.1.9.7) showed that with eight participants per group (α = 0.05, power = 0.8), the study had sufficient power only to detect very large effects (Cohen’s d = 1.51), which substantially exceeds Cohen’s conventional threshold for a “large” effect (d = 0.8). As a result, while the significant large-effect findings are considered reliable, the study was likely underpowered to detect small-to-medium effects, and non-significant outcomes in these cases should be interpreted with caution. Therefore, future studies with larger and more diverse samples are needed to further validate and generalize the present results.

5. Conclusions

This study quantitatively examined the effects of color temperature, illuminance, and horizontal blue light ratio on human psychological, physiological, and sleep-related responses in residential environments. Statistical analyses revealed that color temperature exerted the most significant influence on physiological indicators (heart rate, blood pressure, and galvanic skin response; p < 0.01), followed by illuminance and blue light ratio. Sleep efficiency and sleep score were both highest under cycling color temperature (800 lx, 25% blue light ratio), while deep sleep ratio peaked under 6200 K and 800 lx conditions. In addition, visual performance (IMC index) was significantly enhanced in cycling blue-light environments (p < 0.01). These findings confirm that the lighting parameters have quantifiable effects on multiple sensory and behavioral dimensions. Utilizing range and variance methods, the study identifies comfort zones and recommended lighting conditions for different behavioral orientations, developing a rhythmic lighting scheme for residential spaces. Adjusting the lighting environment aims to indirectly regulate users’ physiological rhythms to improve sleep quality, promote health, stabilize emotions, and enhance memory. This ultimately helps users achieve positive outcomes in sleep, mood, and health, illustrating a blueprint for optimizing healthy lighting environments and providing robust support for research and practice in related fields.

In the future, integrating dynamic lighting technology with healthy lighting design presents broad application prospects and significant potential. It creates more beautiful, comfortable, and intelligent lighting environments that fulfill people’s pursuit of high-quality living and serve as an important means to address global climate change and promote sustainable development. Therefore, it is imperative to pursue in-depth research in this direction during future studies to advance toward the goals of green and healthy development.