Tracing the Morphogenesis and Formal Diffusion of Vernacular Mosques: A Typo-Morphological Study of Djebel Amour, Algeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

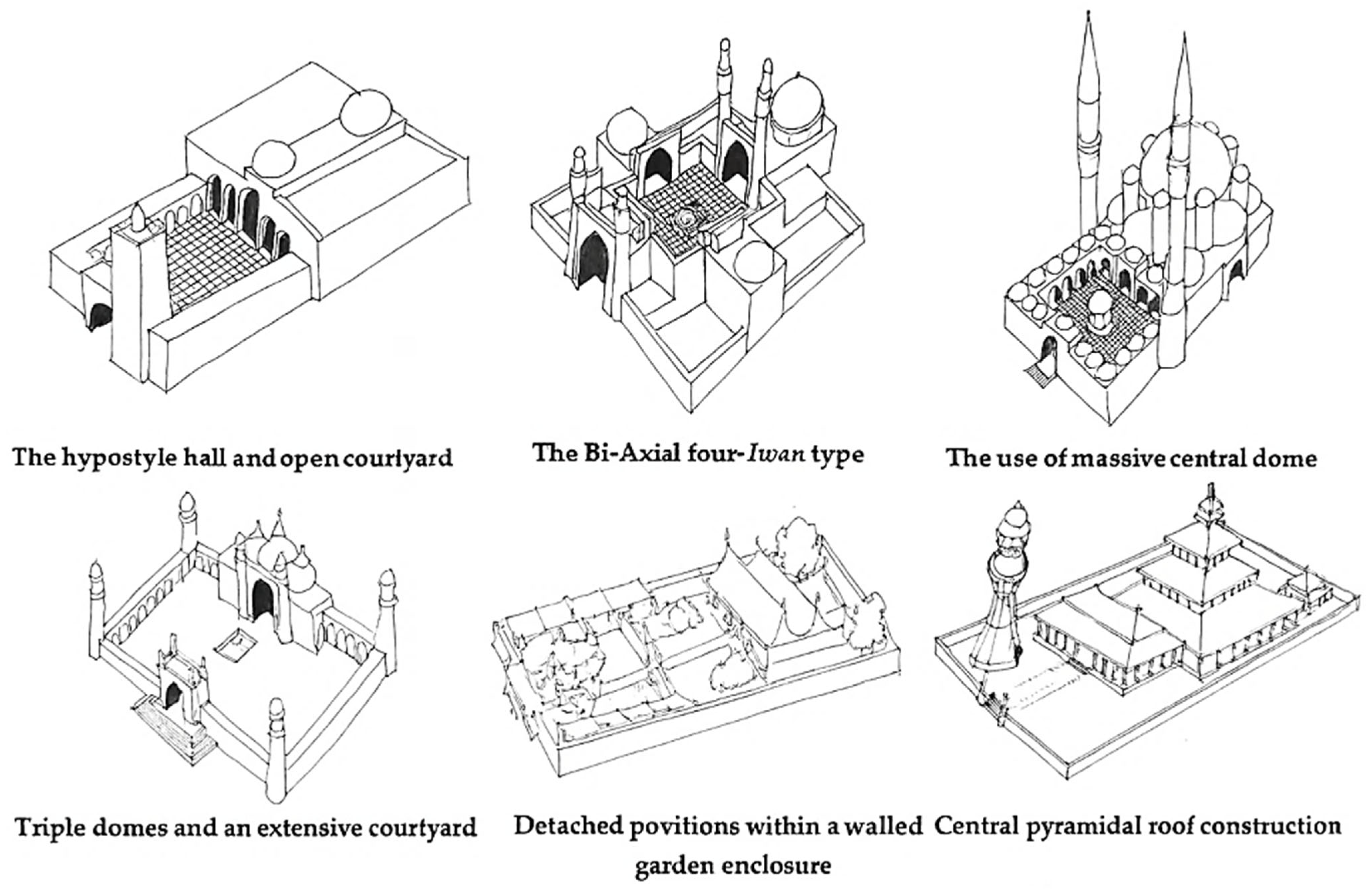

2. Evolution of Mosque Typologies: From Canonical Forms to Vernacular Traditions

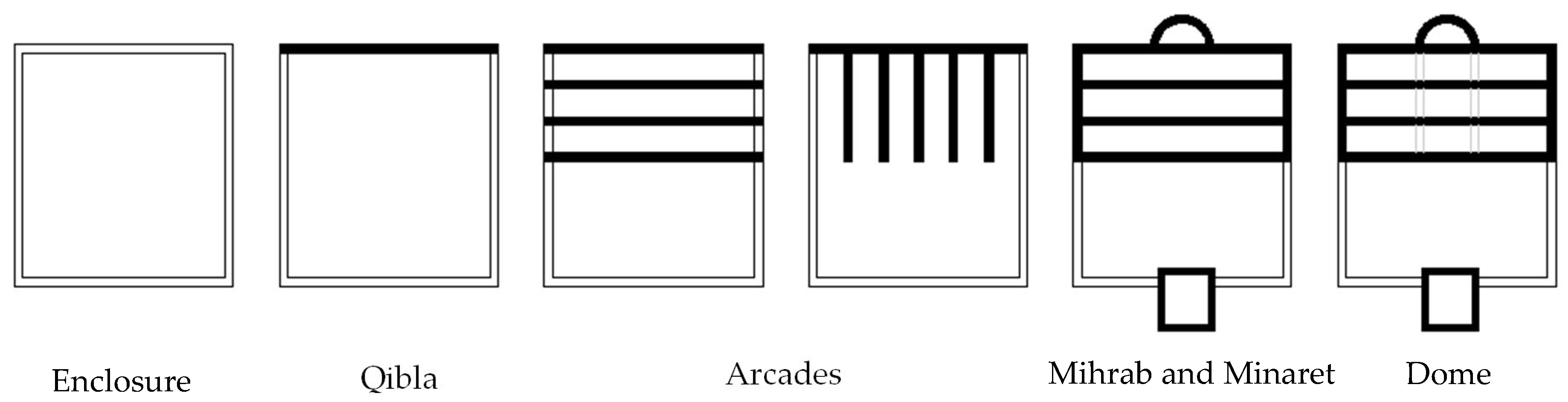

3. Study Area: Geographical and Socio-Cultural Context of Djebel Amour

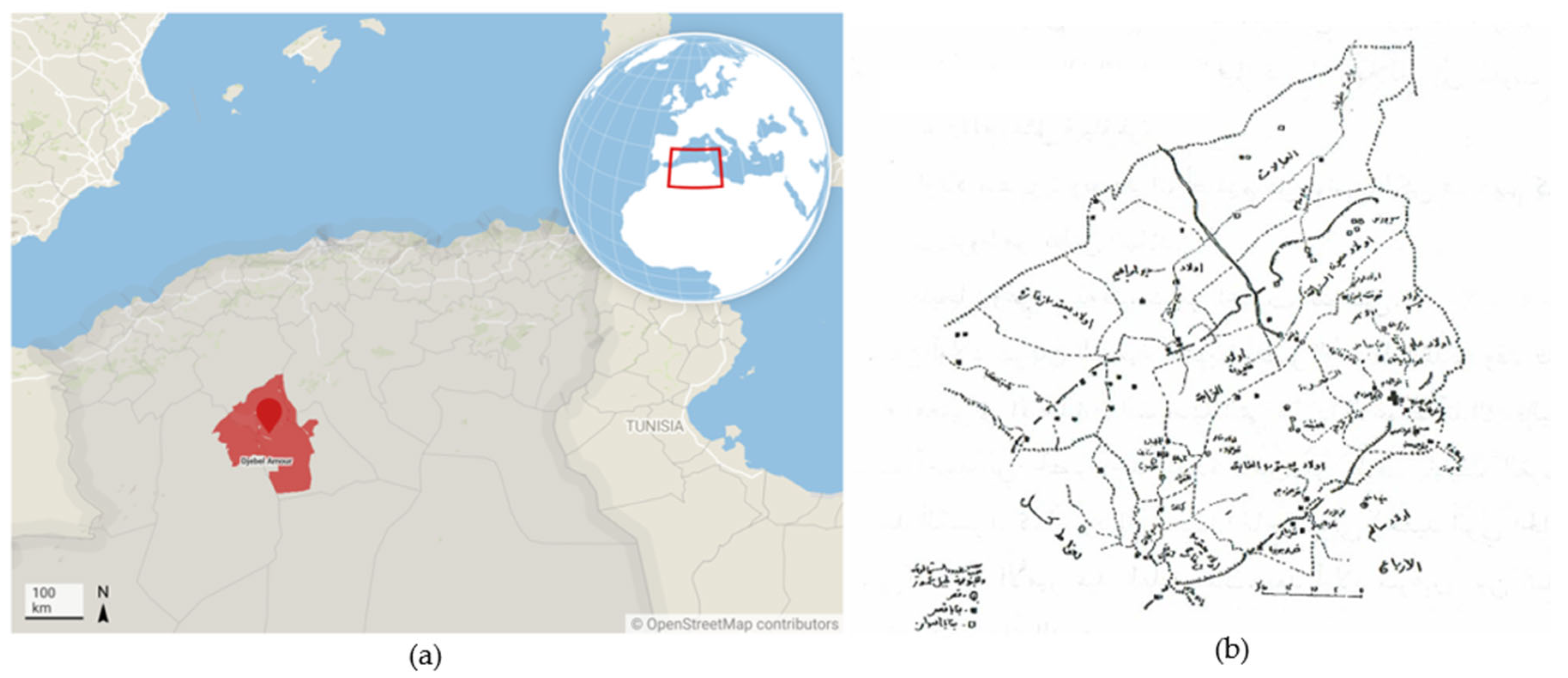

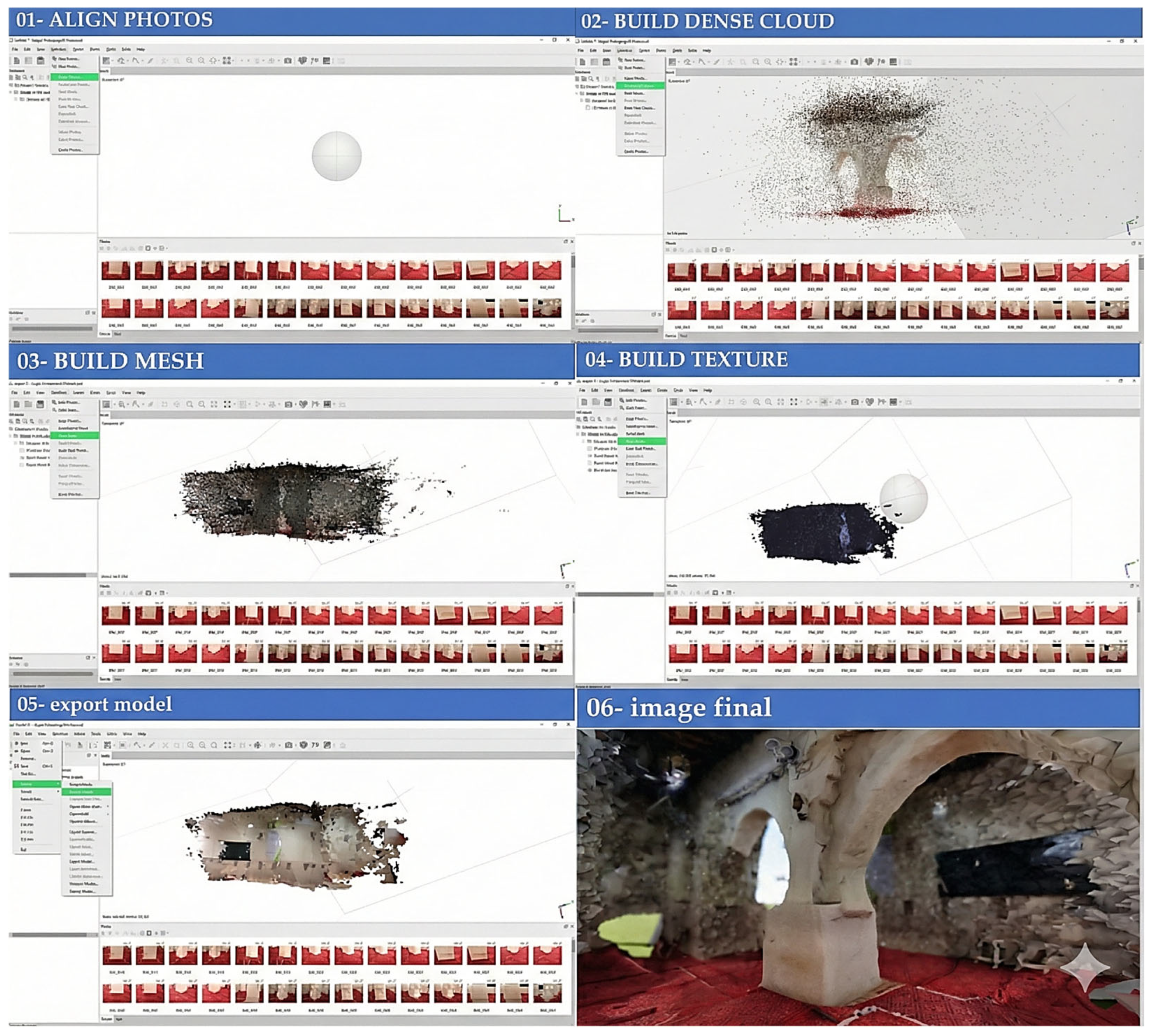

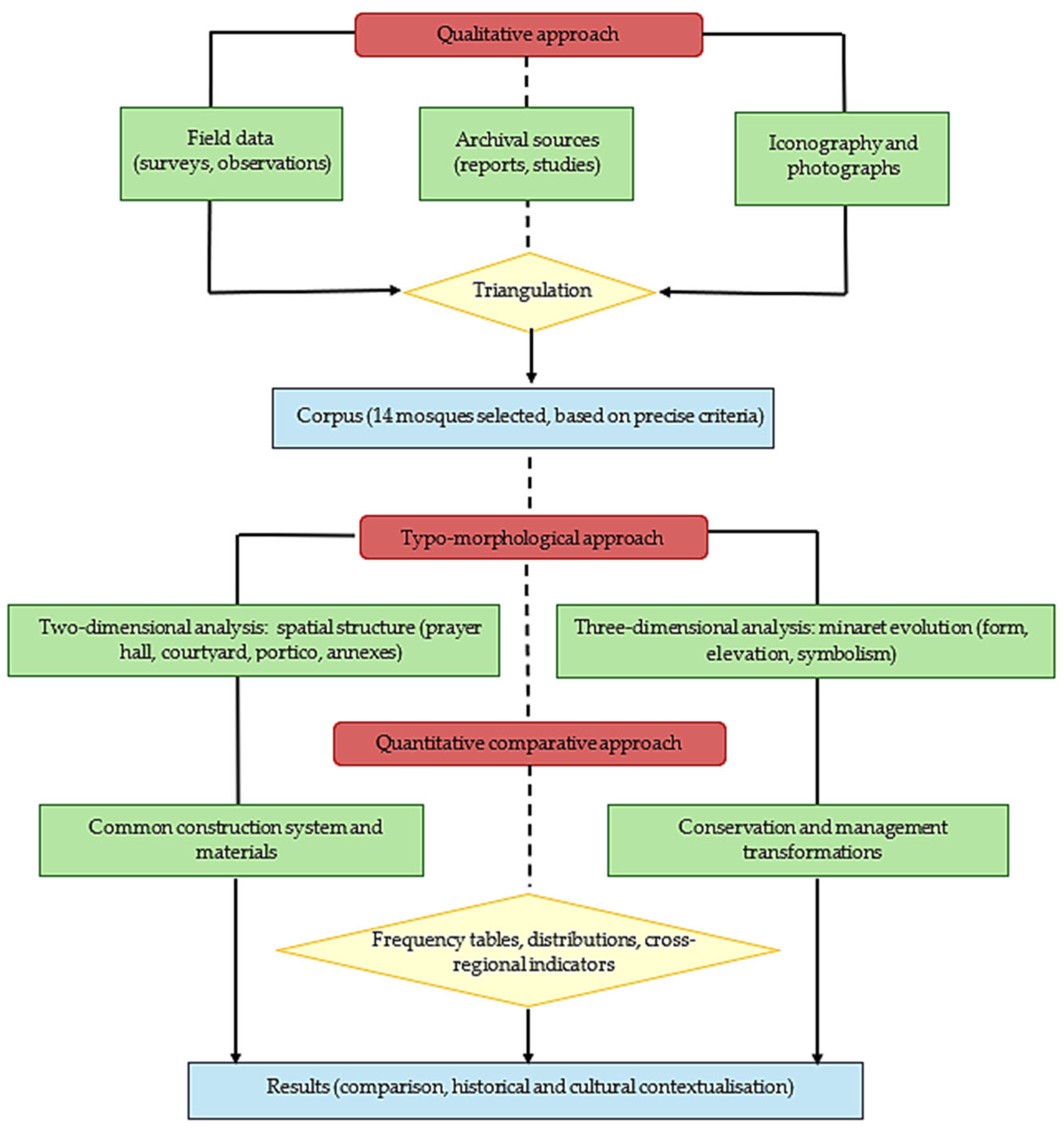

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Qualitative Approach

4.1.1. Selection of Sample and Documentation Sources

- Survey Sheet

- Written and archival sources

- Iconographic documents

- Interviews and field observations

4.1.2. Constitution of the Study Corpus

- Dating

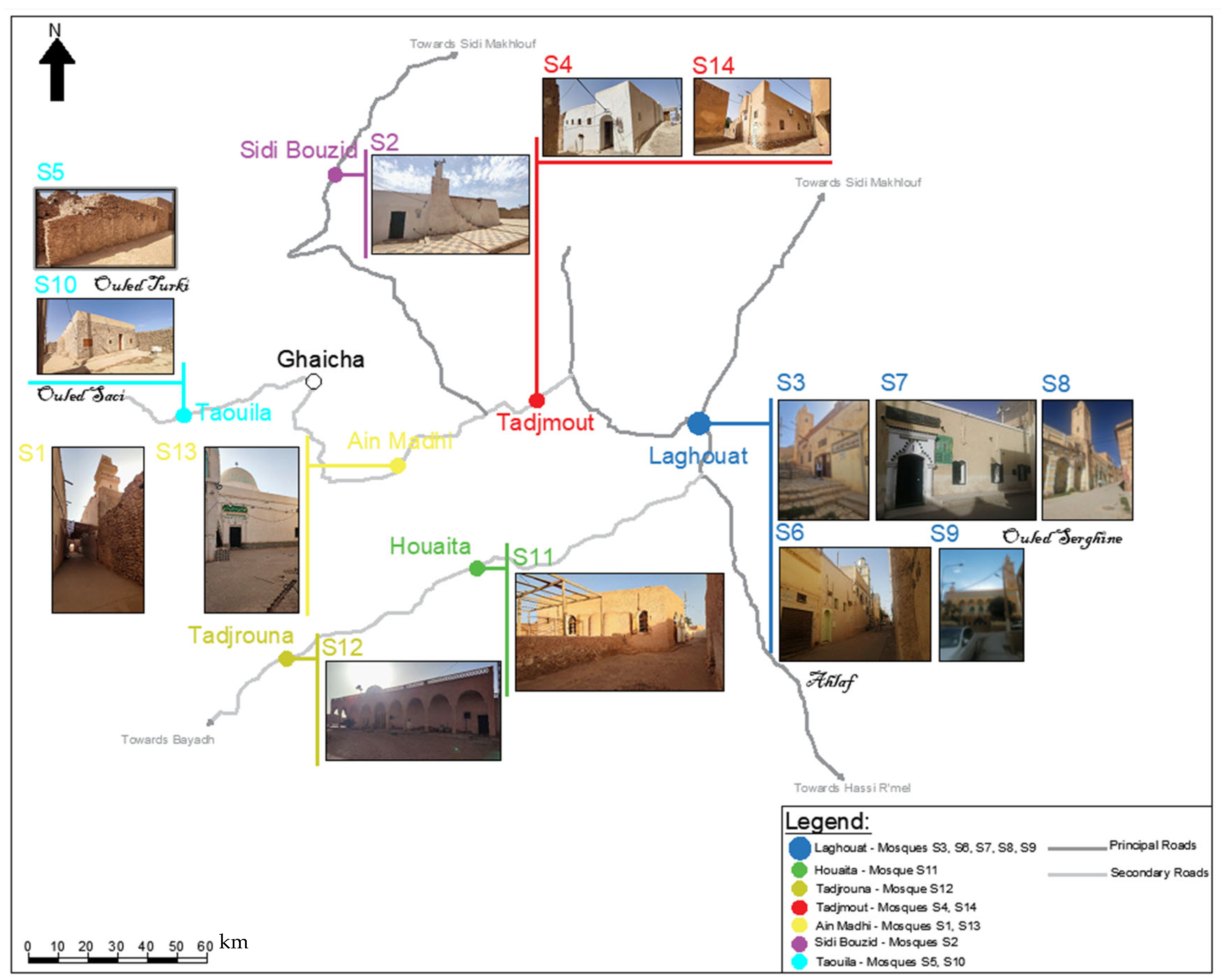

- Location

- Functional typology

- Tribal affiliation and social roots

- State of conservation and morphological reconstruction

4.2. Typo-Morphological Approach as an Analytical Framework

4.3. Quantitative Comparative Approach

5. Results and Discussion: Typo-Morphological Adaptations of Vernacular Mosques in Djebel Amour

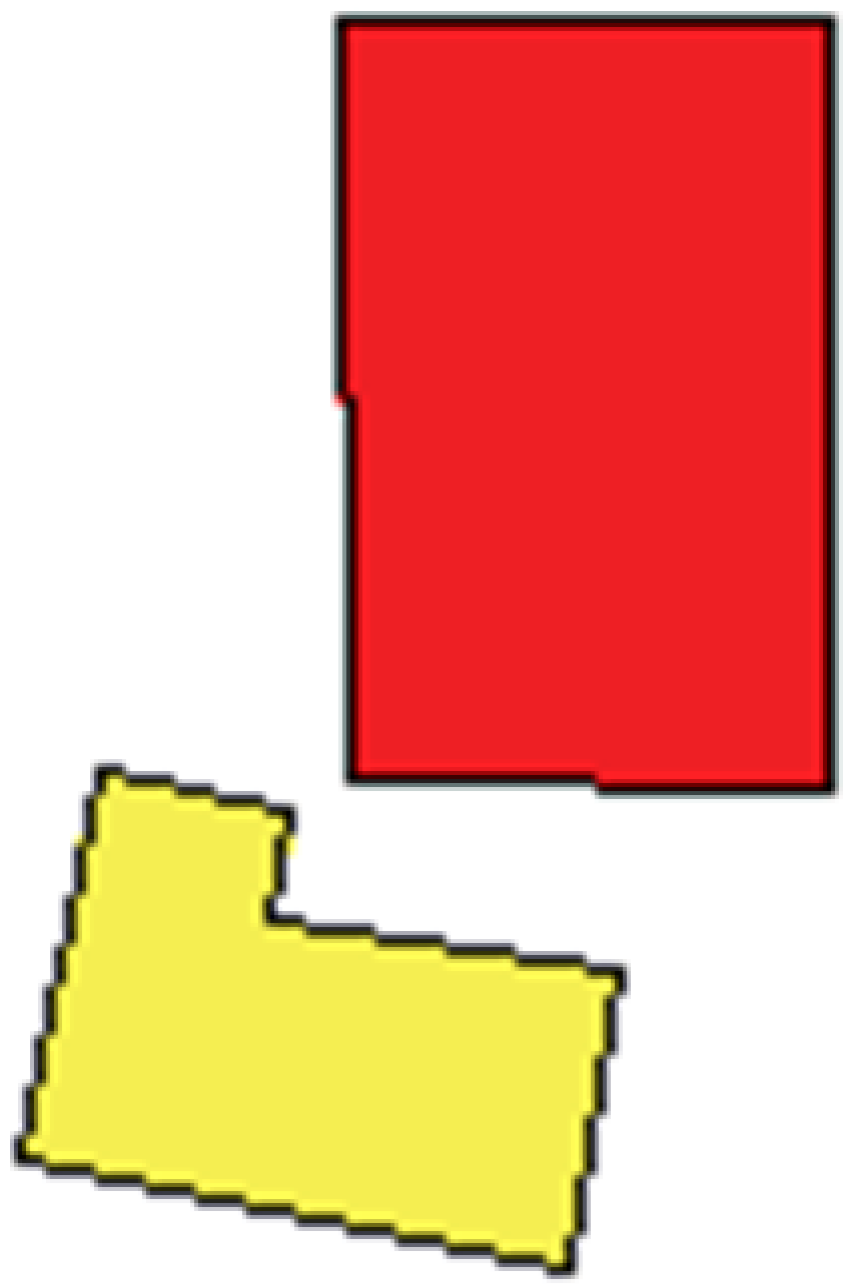

5.1. Morphological Genesis and Typological Structures of Vernacular Mosques

5.1.1. The Courtyard (Sahn): Absence, Marginality, and Contextual Adaptations

- Exceptional contextual cases involving courtyard presence:

5.1.2. The Portico: A Liminal Space of Vernacular Expression

5.1.3. Variability of Annexes and Spatial Integration

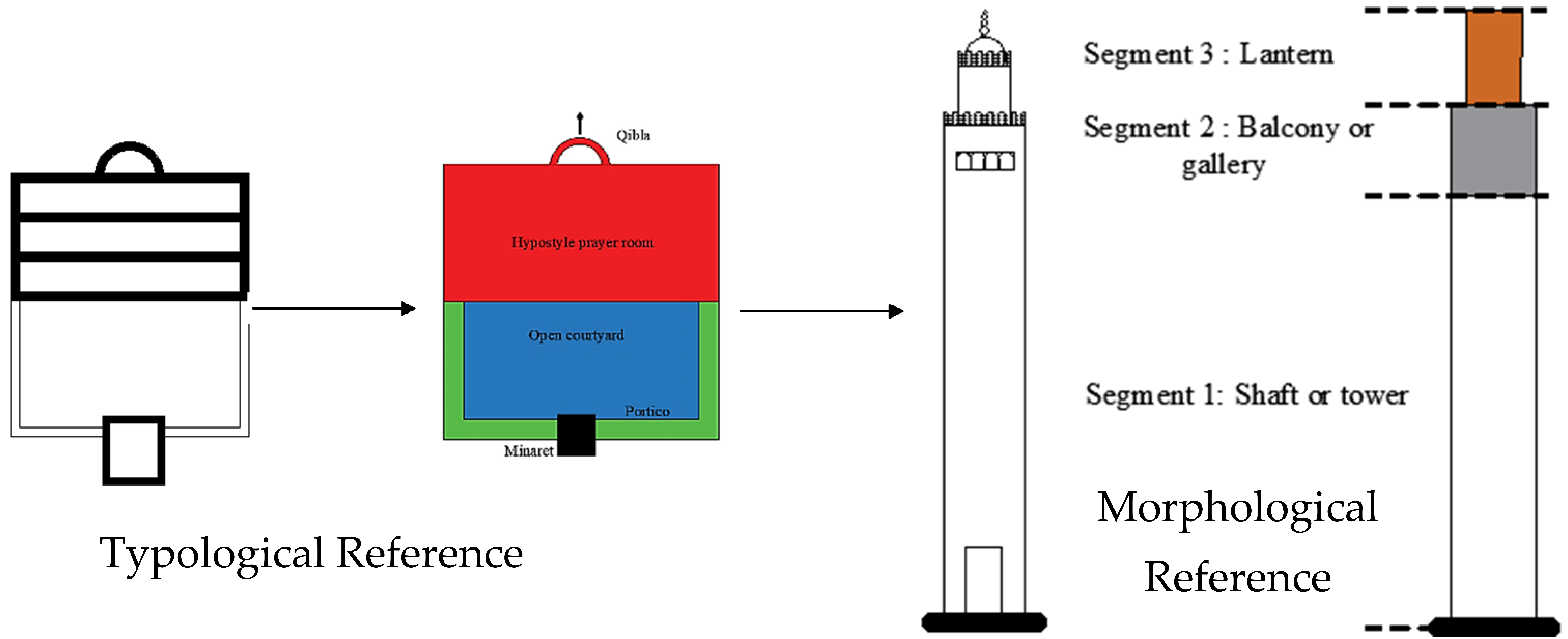

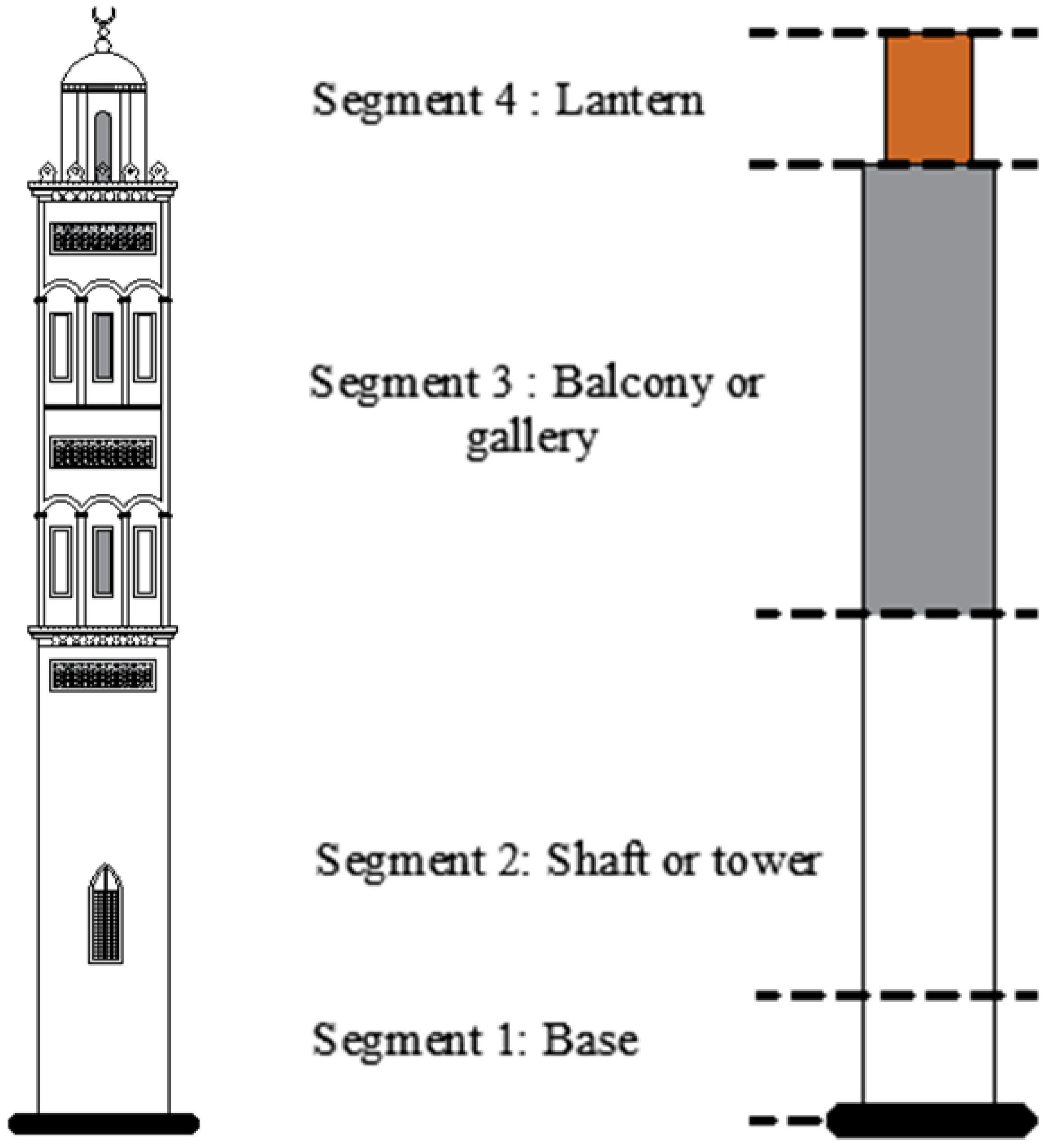

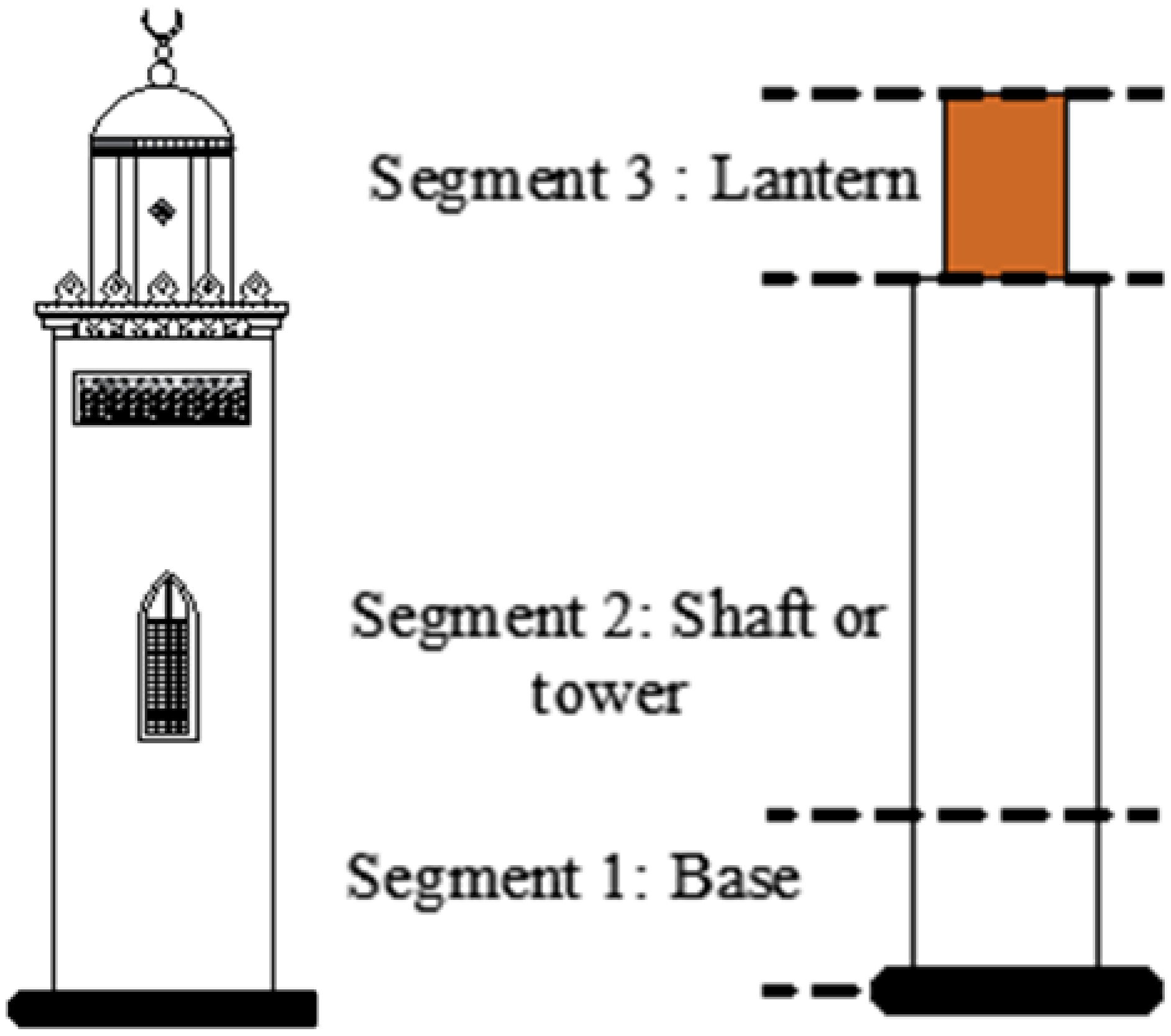

5.2. Reinventing the Canon: The Minaret Between Eastern Traditions and Colonial Influences

5.2.1. Precolonial Legacies: Architectural Sobriety and Eastern Continuities

5.2.2. Colonial Period: The Selective Emergence of Monumentality

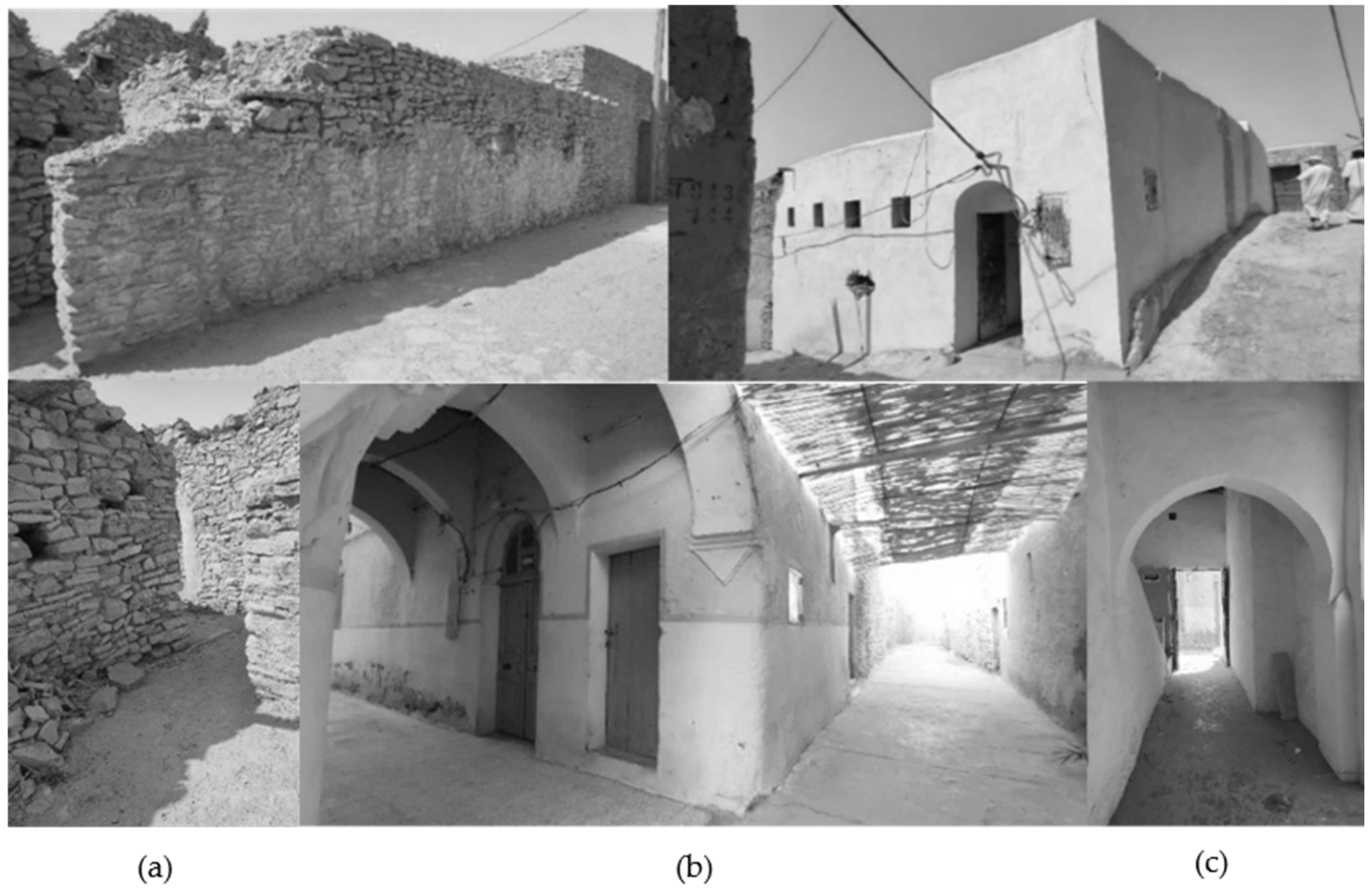

5.3. Vernacular Construction Systems and Materials

5.3.1. Local Materials and Traditional Craftsmanship

5.3.2. Traditional Flooring and Load-Bearing Structures

5.4. Conservation and Management of Transformations in the Mosques of Djebel Amour

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPSMVSS | Plan Permanent de Sauvegarde et de Mise en Valeur des Secteurs Sauvegardés |

| DC | Directorate of Culture |

| DARW | Directorate of Religious Affairs and Waqf |

| ONPCAS | National Office of the Saharan Atlas Cultural Park |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

References

- Hillenbrand, R. Islamic Architecture Form, Function and Meaning; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- El-Behnasi, S. L’art Mamelouk. Splendeur et Magie des Sultans; 2e Museum with No Frontiers: Vienna, Austria, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Golvin, L.; Rabahi, R. La Mosquée: Ses Origines, Sa Morphologie, Ses Diverses Fonctions, Son Role Dans la vie Musulmane Plus Spécialement en Afrique du Nord; Alger-Livres: Alger, Algeria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuban, D. Muslim Religious Architecture Part I The Mosque and Its Early Development; 1974; Available online: https://www.abebooks.co.uk/book-search/publisher/e-j-brill-leiden/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Ettinghausen, R. Islamic Art and Architecture; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Awoussi, M.Y.; Domtse, E.K.A.; Gake, D.K.; Genovese, P.V.; Dziwonou, Y. Analysis of the Sustainability Elements of Vernacular Architecture in Northern Togo: The Case of the Kara Region. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuban, D. Muslim Religious Architecture Part II Development of Religious Architecture in Later Periods; 1985; Available online: https://www.abebooks.co.uk/book-search/publisher/e-j-brill-leiden/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Grandet, D. Architecture et Urbanisme Islmaique; Office des Publications Universitaires: Alger, Algeria, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Benyoucef, B. Introduction à l’Histoire de l’Architecture Islamique; Office des Publications Universitaires: Alger, Algeria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weisbin, K. Common Types of Mosque Architecture; Khan Academy: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, F.A.; Ismael, Z.K. A Typological Study of the Historical Mosques in Erbil City. Sulaimani J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 6, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajuddin, M.; Rasdi, M. Mosque Architecture in Malaysia: Classification of Styles and Possible Influence; Jurnal Alam Bina: Skudai, Malaysia, 2007; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, M. Per una lettura analitica delle masjid del Maghreb. In Spazi e Culture del Mediterraneo; Edizioni Kappa: Rome, Italy, 2006; ISBN 88-7890-721-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Culture; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969; ISBN 978-0-13-395673-3. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P. Built to Meet Needs: Cultural Issues in Vernacular Architecture; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ebru Aydeniz, N.; Fellahi, N. Mzab Algerian Vernacular Architecture: A Connection Between The Architecture and The Environment; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, M.M.; Hassanpour, B.; Utaberta, N. A Study on African Vernacular Mosque: A Lesson from Tradition. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 747, 157–160. Available online: https://www.scientific.net/AMM.747.157 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Ghanbari, J. An Investigation into Architectural Creolization of West African Vernacular Mosques. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2021, 8, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghafis, M.F.; Sibley, M. The Vernacular Mosques of Al-Khabra in Saudi Arabia: Investigating Urban Architectural and Social Dimensions. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 1–15. Available online: https://kuwaitjournals.org/jer/index.php/JER/article/view/20211?utm (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Khalid, R. A Typological Study of West African Mosque at Djenné, Mali. Astrolabe A CIS Stud. Res. J. 2023, 5, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ardalan, N. The Visual Language of Symbolic Form: A Preliminary Study of Mosque Architecture. Aga Khan Award for Architecture. In Proceedings of the Architecture as Symbol and Self-Identity, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 9–12 October 1979; pp. 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zerari, S.; Cirafici, A.; Sriti, L.; Pace, V.; Palmieri, A. Reflections on the Vernacular Mosques in the Souf Region, Algeria: An Attempt to Inventory the Local Architectural Language. ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2024, 21, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, A. Espace et Sacrée au Sahara; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2002; ISBN 978-2271078544. [Google Scholar]

- Cote, M. La Ville et le Désert, le Bas-Sahara Algérien; Karthala Éditions: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chekhab-Abudaya, M. Le Qsar, Type D’implantation Humaine au Sahara: Architecture du Sud Algérien; Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology; Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78491-347-2. [Google Scholar]

- Despois, J. L’atlas saharien occidental d’Algérie: Ksouriens et Pasteurs. Cah. De Géographie Du Québec 1959, 3, 403–415. Available online: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/020194ar (accessed on 27 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Camps, G. Amour (djebel). Encycl. Berbère 1986, 4, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlaoui, A. Examples of Ksour in the Laghouat Region Namādhij min Quṣūr Minṭaqat al-Aghouat; Fonds National Pour la Promotion et le Développement des Arts et Lettres: Alger, Algeria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carroué, L. Algérie: Le Djebel Amour, les Hautes Terres des Marges Sahariennes Face aux Enjeux de la Sédentarisation et de la Désertification n. d. Available online: https://cnes.fr/geoimage/algerie-djebel-amour-hautes-terres-marges-sahariennes-face-aux-enjeux-de-sedentarisation-de (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Ali, N.; Zhou, Q. Digital Documentation and Conservation of Architectural Heritage Information: An Application in Modern Chinese Architecture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.; Mazzetto, S. Integrating Knowledge Graphs and Digital Twins for Heritage Building Conservation. Buildings 2024, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marey, M.; Guillaume, S. Expédition de Laghouat; Imprimerie A: Bourget, France, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Fromentin, E. Un été dans le Sahara; Paris, J. Clay, imprimeur, Rue Saint Benoit: Paris, France, 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Dermenghem, E. Le pays d’Abel, Le Sahara des Ouled-Nail, des Larbaa et des Amour; Paris, France, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, O. Laghouat: Eassai D’histoire Sociale; Collège de France: Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hirtz, G. L’Algérie Nomade et Ksourienne 1830–1954; P. Tacussel: Marseille, France, 1989; ISBN 978-2-903963-39-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mangin, E. Notes sur l’Histoire de Laghouat; Adolphe Jordan, Librairie-Editeur: Algeria, Algeria, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Labter, M. Laghouat: Pages de la Civilisation et de L’histoire; Hibr: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saoudi, A. Le Djebel Amour; Dar Kerdada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne, K. Sous le Ciel de Laghouat: Histoire Politique, Sociale et Culturelle de Laghouat des Origines à Nos Jours; El Alamia: Giza, Egypt, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Labter, L. Laghouat: Vue par des Chroniqueurs, Écrivains, Peintres, Voyageurs, Explorateurs et Conquérants; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cat, E. A Traves le Désert; 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Habboul, H. Rehabilitation of desert ksour: Ain Madi ksar as an example Iʿādat taʾhīl al-quṣūr al-ṣaḥrāwiyya: Qaṣr ʿAyn Māḍī namūdhajan. Magister, Algiers 2, 2010, unpublished thesis.

- Takhi, B. An Approach to Restoring Desert Ksour in the Laghouat Region: A Case Study of the Taouiala Ksar. Maqāraba li-Tarmīm al-Quṣūr al-Ṣaḥrāwiyya bi-Minṭaqat al-Aghwāṭ: Dirāsa Ḥāla Qaṣr Tāwiyāla. Ph.D. Thesis, Constantine, Algeria, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mahcer, I.; Takhi, B. La Revalorisation du ksar d’El-Haouita. Master’s Thesis, Amar Tledji Laghouat, Laghouat, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Talha, O. An Analytical Approach to the Transformations of the Old Mosques of the City of Laghouat: A Case Study of the Al-Atiq Mosque Maqāraba Taḥlīliyya li-Taḥawwulāt al-Masājid al-Qadīma li-Madīnat al-Aghwāṭ: Dirāsa Ḥāla Masjid al-‘Atīq. Master’s Thesis, Amae Tledji Laghouat, Laghouat, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haizoum, T. An Analytical Approach to the Transformations of the Old Mosques of the City of Laghouat: A Case Study of the Tawti Mosque Maqāraba Taḥlīliyya li-Taḥawwulāt al-Masājid al-qadīma li-Madīnat al-Aghwāṭ: Dirāsa Ḥāla masjid Al-Tāwtī. Master’s Thesis, Amar Tledji Laghouat, Laghouat, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rabhi, E. An Analytical Approach to the Transformations of the Old Mosques of the City of Laghouat: A Case Study of the Sidi Abdelkader Jilali Mosque Maqāraba Taḥlīliyya li-Taḥawwulāt al-Masājid al-Qadīma li-Madīnat al-Aghwāṭ: Dirāsa Ḥāla Masjid Sīdī ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlālī. Master’s Thesis, Amar Tledji Laghouat, Laghouat, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chettih, A. Preserving Islamic Architectural Heritage: Practices and Prospects Case Study: Ancient Mosques in the Ksours of Laghouat Al-Ḥifāẓ ‘alā al-Turāth al-Mi’mārī al-Islāmī: Al-Mumārasāt Wa-al-Āfāq—Dirāsa Ḥāla: Al-Masājid al-‘atīqa bi-Quṣūr al-Aghwāṭ. Ph.D. Thesis, Constantine, Laghouat, Algeria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Panerai, P.; Depaule, J.C.; Demorgon, M. Analyse Urbaine; Edition Parenthèses: Marseille, France, 1999; ISBN 2-86364-603-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gaci, H. Les Minarets des Mosquées Dans la Période Coloniale: Analyse Typo-Morphologique. Master’s Thesis, Abderrahmane Mira Bejaia, Laghouat, Algeria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Benabadji, L. Les Minarets Ziyanides Entre Modèles Andalous-Maghrébins et Identification Locale en Vue De Réinterprétation Contemporaine. Ph.D. Thesis, Mohamed Khider Biskra, Laghouat, Algeria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.L.; Mustafa, F.A. Mosque Typo-Morphological Classification for Pattern Recognition Using Shape Grammar Theory and Graph-Based Techniques. Buildings 2023, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, Z. Cohabitation Entre L’architecture Traditionnelle et Moderne Pour un Modèle D’habitat Adapté à l’aspect Climatique et Social des Villes Sahariennes Cas D’étude la ville de Béchar. Master’s Thesis, Mohamed Khider Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, R.; Inangda, N.; Ahmad, Y. A Typological Study Ofmosque Internal Spatial Arrangement: A Case Study on Malaysian Mosques (1700–2007). Ollr1lal Ofdesignand Tilebuilt Environ. 2008, 4, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Redjem, M. Évolution des Éléments Architecturaux et Architectoniques de la Mosquée en vue d’un cadre Référentiel de Conception. Master’s Thesis, Cas mosquées historiques de Constantine, Constantine, Algeria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cherif, I.; Allani Bouhoula, N. Tunis’s New Mosques Constructed Between 1975 and 1995: Morphological Knowledge. J. Islam. Archit. 2015, 3, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukma, M.; Stefanidou, M. The Morphology And Typology of The Ottoman Mosques of Northern Greece. Int. J. Herit. Archit. 2017, 1, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, B.S.; Wibowo, A.S. A Typological Study of Historical Mosques in West Sumatra, Indonesia. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2018, 17, 1–8. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.3130/jaabe.17.1 (accessed on 27 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Elkhateeb, A.; Attia, M.; Balila, Y.; Adas, A. The Classification of Prayer Halls in Modern Saudi Masjids: With Special Reference to The City of Jeddah. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2018, 12, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redjem, M.; Mazouz, S. Spatial and Social Interaction in Medieval Algerian Mosques: A Morphological Analysis Using Space Syntax. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, G.M.; Hajime, S. Analyses and Architectural Typology of Preserved Traditional Mosques in the Old City of Herat in Afghanistan: The Case of Quzzat Quarter. Built Herit. 2022, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakriah, N. The Typology of Mosque Architecture in West Aceh. J. Islam. Archit. 2022, 7, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrini, W.; Santosa, H.; Martiningrum, I. The Characteristic of Minaret Based on Community Preference for the Composition of Mosque Architecture in Malang City; Atlantis Press—Advances in Engineering Research: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 195, pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Duprat, B.; Paulin, M. Les Types de L’architecture Traditionnelle Des Alpes du Nord: Maisons et Chalets du Massif des Bornes; Ecole d’Architecture de Lyon, Laboratoire D’analyse des Formes: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- SRITI, L. Potentialités Architecturales et Bioclimatiques de L’habitat Autoconstruit. Cas d’une ville du Sud: Biskra. Master’s Thesis, Mohamed Khider Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 1996, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- SRITI, L. Architecture Domestique en Devenir. Formes, Usages et Représentations.—Le cas de Biskra. Ph.D. Thesis, Mohamed Khider Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2013, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Chakroun, L. Analyse morphologique de quelques minarets de l’époque ottomane: Essai de définition d’un “style” ottoman. In Proceedings of the Le Corpus d’Archéologie Ottomane dans le Monde Fondation Temimi, Lectures du Coran, Tunis, 24–25 March 2016; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zerari, S.; Sriti, L.; Pace, V. Morphological Diversity of Ancient Minarets Architecture in The Ziban Region (Algeria): The Question of Form, Style and Character (1). METU J. Fac. Arch. 2020, 37, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabadji, L.; Bencherif, M. Identite Morphologique Des Minarets Ziyanides. Sci. Technol. D 2020, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beldjilali, S.; Benkari, N.; Namourah, Z.; Varum, H. Morphological and Geometrical Study of Historical Minarets in the North of Algeria. Bud. I Archit. 2024, 23, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msadek, L.; Allani Bouhoula, N. Etude Morphologique Des Mosquées En Tunisie Du 7ème Siècle Au 19ème Siècle. Master’s Thesis, National School of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Carthage, Carthage, Tunisia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cherif, I.; Allani Bouhoula, N. Ancient Tunisian Mosques: Morphological Knowledge and Classification. Int. J. Herit. Archit. 2017, 1, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourouiba, R. L’art Réligieux Musulman en Algérie; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bourouiba, R. Apports de l’Algérie à L’architecture Religieuse Arabo-Islamique; Office des Publications Universitaires-Alger: Alger, Algeria, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, V. Les mosquées ibadites du Maghreb. Rev. Des Mondes Musulmans Mediterr. 2009, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkari, N. The Architecture of Ibadi Mosques in M’zab, Djerba, and Oman. J. Islam. Arch. 2019, 5, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schahct, J. Sur la diffusion des formes d’architecture religieuse musulmane à travers le Sahara. Trav. L’institut Rech. Sahariennes 1954, XI, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sriti, L.; Zerari, S.; Hamouda, A.; Midni, C.-D. Le Patrimoine Religieux Musulman En Algérie Comme Révélateur de l’identité Régionale. Cas Des Mosquées Du Bas-Sahara. In Proceedings of the Deuxième Colloque International sur le Patrimoine et le Développement, Sousse, Tunisia, 25 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zerari, S. Vers une Caractérisation du Patrimoine Religieux Islamique. Cas Mosquées du Bas-Sahara. Ph.D. Thesis, Mohamed Khider Biskra, Biskra, Algerie, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, V. Les Mosquées Ibadites du Djebel Nafusa: Architecture, Histoire et Religions du nord-Ouest de la Libye (VIIIe-XIIIe Siècle); Society for Libyan Studies Monograph 10; The Society for Libyan Studies c/o The British Academy 10-11 Carlton House Terrace: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-900971-44-7. [Google Scholar]

- Arigue, B.; Sriti, L.; Santi, G.; Khadraoui, M.A.; Bencheikh, D. Exploring the Cooling Potential of Ventilated Mask Walls in Neo-Vernacular Architecture: A Case Study of André Ravéreau’s Dwellings in M’zab Valley, Algeria. Buildings 2023, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devant La Mosquée. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/algerie/laghouat/cpa-algerie-laghouat-devant-la-mosquee-445464585.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- L’entrée de La Mosquée. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/algerie/laghouat/cpa-algerie-laghouat-l-entree-de-la-mosquee-445464521.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Safah Mosque. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/static/img_large/auction/002/366/954/748_001.jpg (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Khalifa (or Ahlaf) Mosque in 1944. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/static/img_large/auction/002/031/805/247_001.jpg (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- La Grande Séguia. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/algerie/laghouat/cpa-algeria-laghouat-la-grande-seguia-793973-2195150262.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Sub-Prefecture of the Wilaya of Laghouat. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/static/img_large/auction/002/366/954/742_001.jpg (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Bloom, J. Minaret Symbol of Islam; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Général De Beylie, L. La Kalaa des Beni-Hammad; Leroux, E., Ed.; Bibliothèque du Musée de l’Homme: Paris, France, 1909; Available online: https://archive.org/details/lakalaadesbeniha00beyl_0 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Echallier, J.-C. Sur Quelques Détails de L’architecture du Sahara Septentrional; Le Saharien: Douz, Tunisia, 1967; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezali, N. Masjid al-Ṣaffāḥ… masjid banāhu jundī ʾĪṭālī fī wilāyat al-Aghwāt The Safah Mosque... a Mosque Built by an Italian Soldier in the Province of Laghouat. 2023. Available online: https://waqf-dz.org/%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AC%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AD-%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AC%D8%AF-%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%87-%D8%AC%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A7/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Safah Mosque Facade. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/static/img_large/auction/002/314/059/736_001.jpg (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Laghouat: Sur La Terrasse de La Mosquée. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/static/img_large/auction/002/050/404/191_001.jpg (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Khalifa Mosque in 1944. historical Postcard Photograph (c. 1944). Private Archival Image; Originally Found on a Facebook Page But Currently Unavailable Online.

- Laghouat: Khalifa Mosque in 1956. 1956. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/algerie/laghouat/po5810-algeri-laghouat-piazza-ben-badis-cafe-de-l-etoile-fontane-no-vg-227155666.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Saint-Hilarion Cathedral. Available online: https://www.delcampe.net/static/img_large/auction/002/327/654/544_001.jpg (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Archives of the Directorate of Culture of Laghouat, The Traditionnel Floor; Internal Archival Document, Directorate of Culture, Laghouat, Algeria, s. d. Unpublished document.

- Han, P.; Hu, S.; Xu, R. Formal Feature Identification of Vernacular Architecture Based on Deep Learning—A Case Study of Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

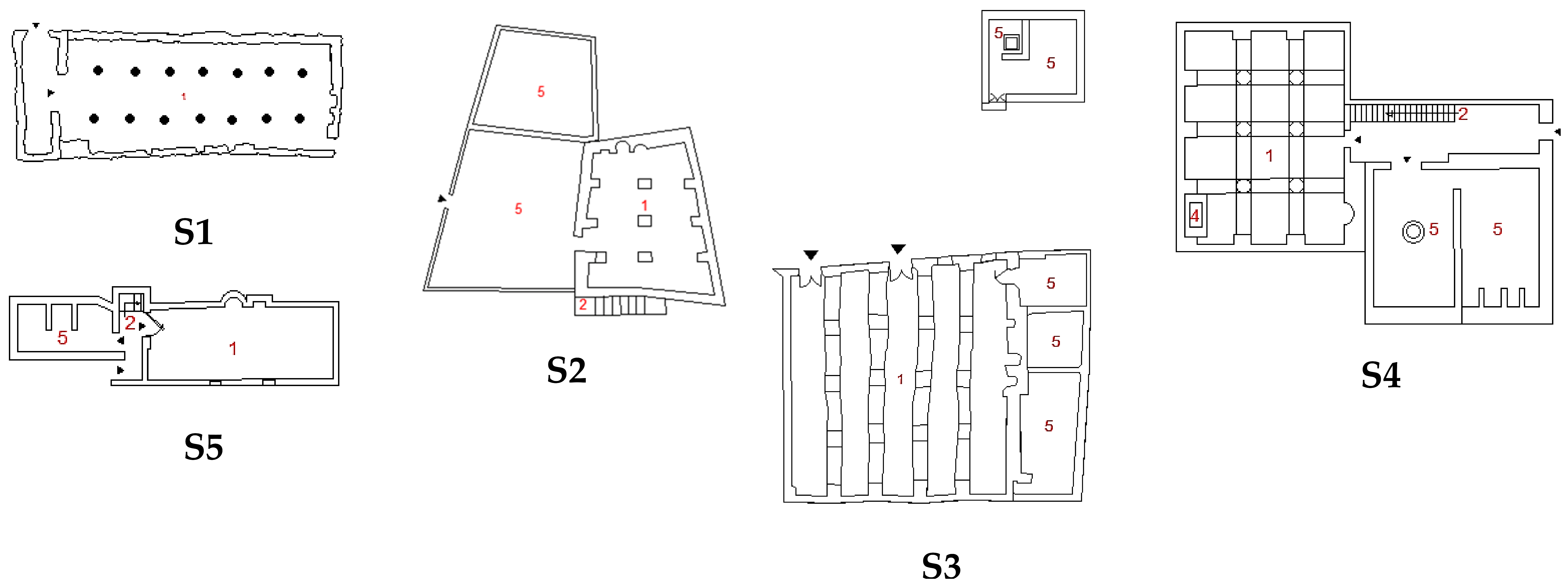

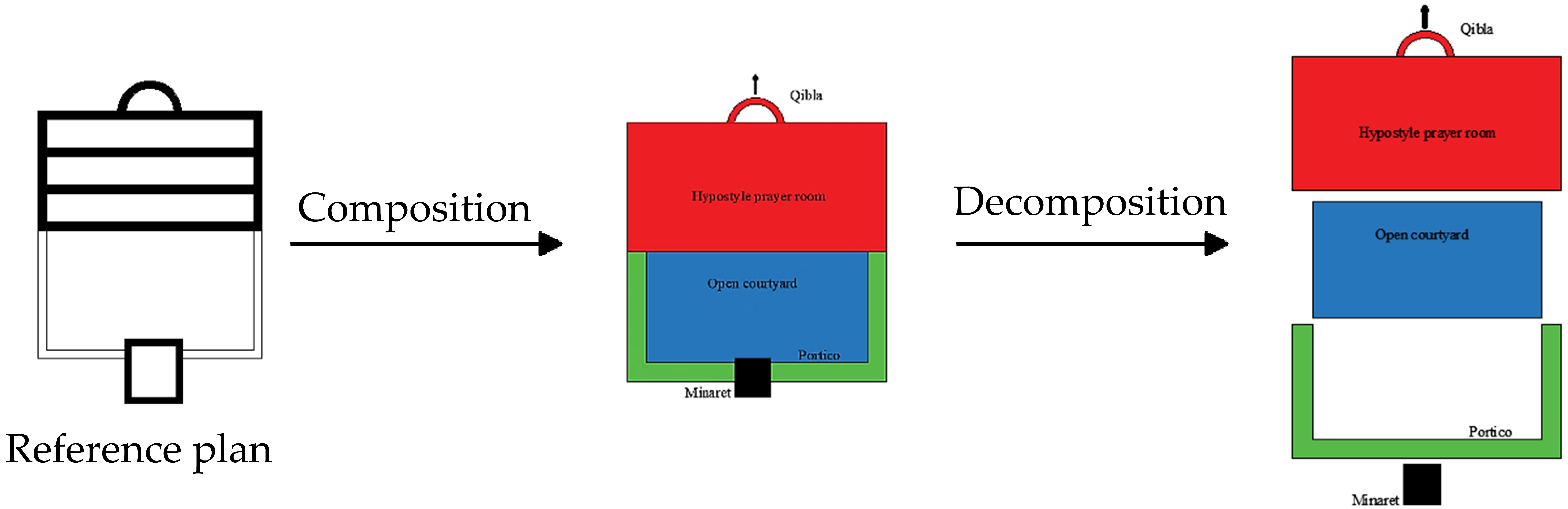

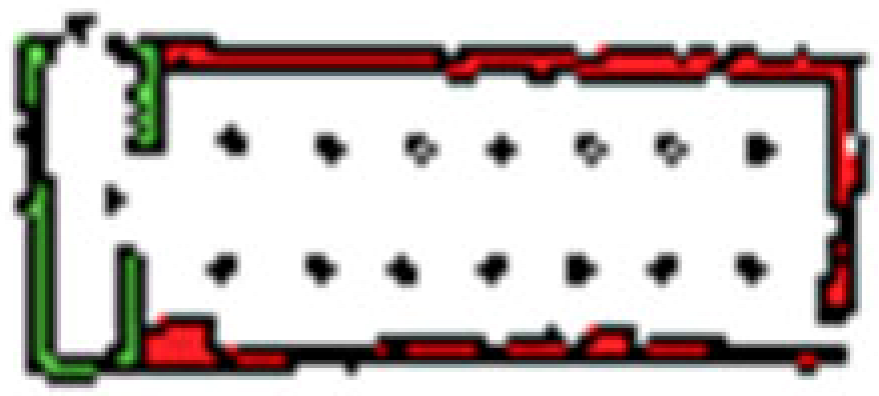

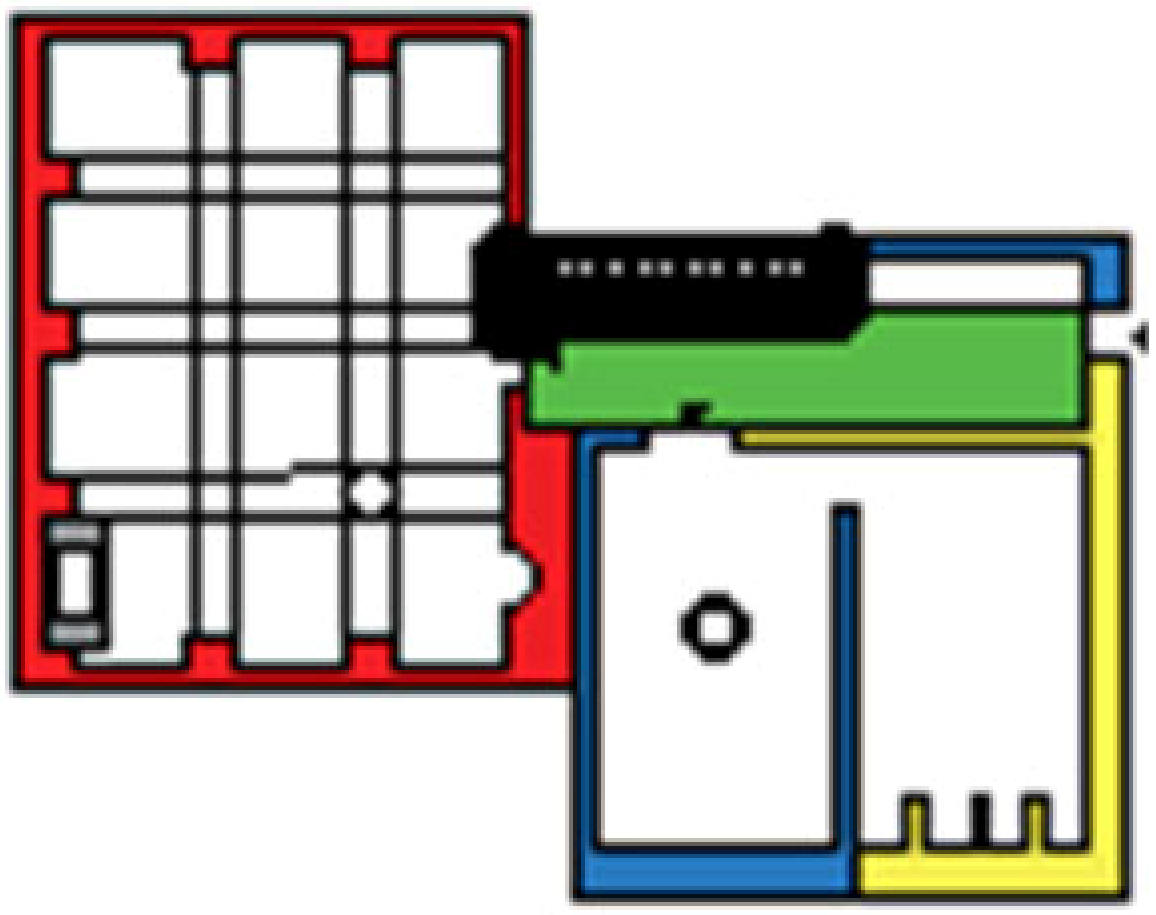

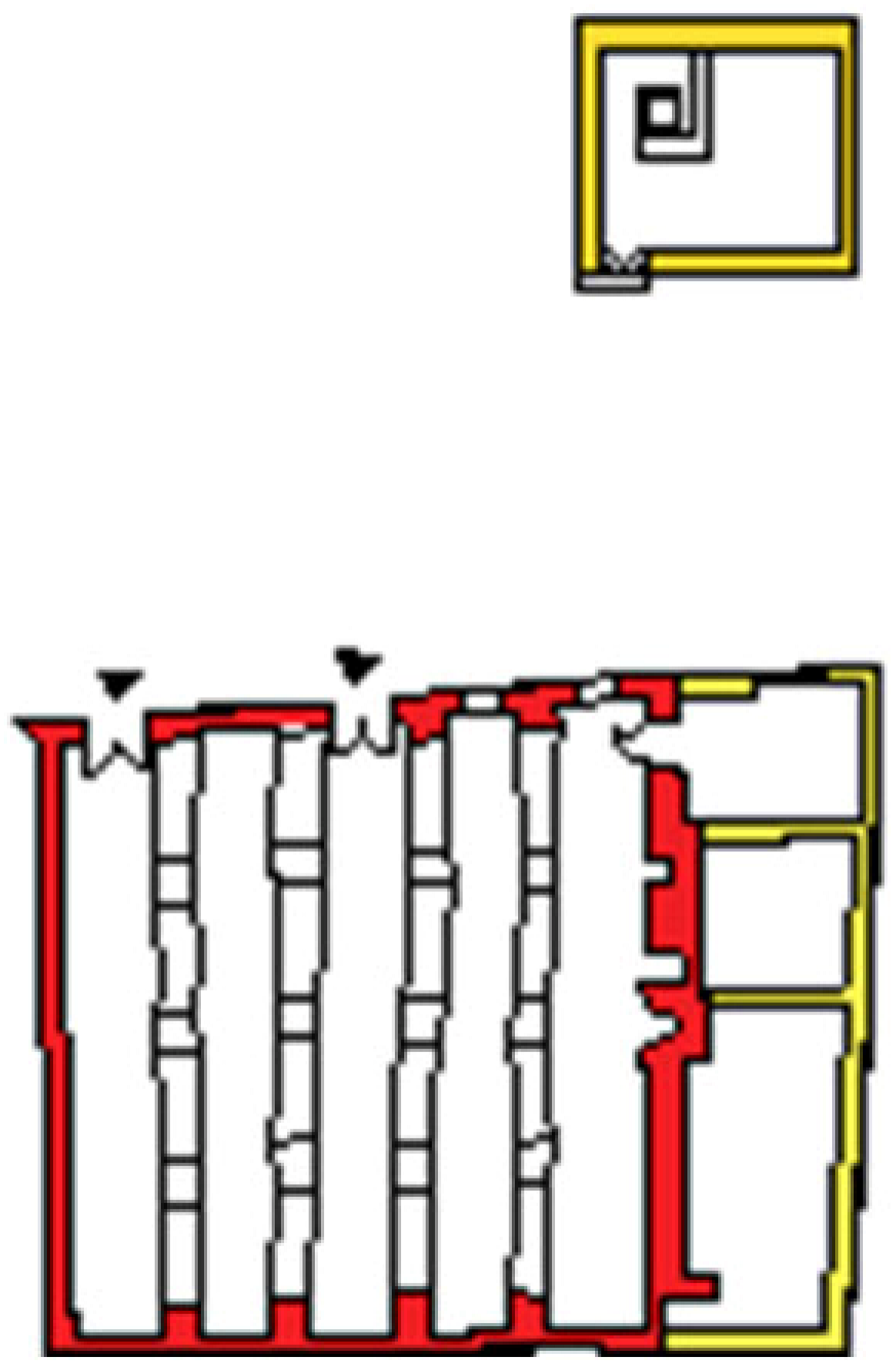

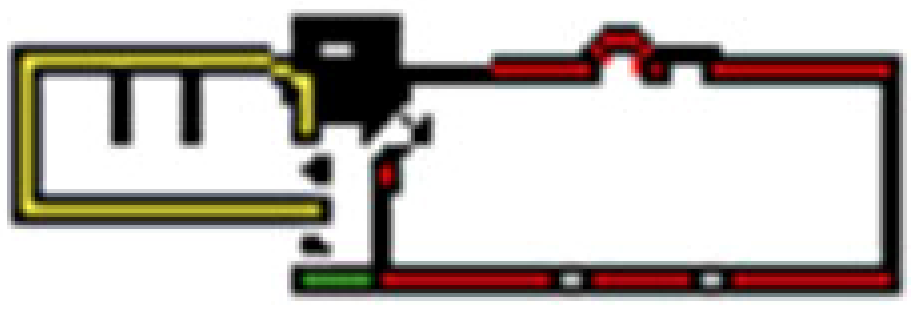

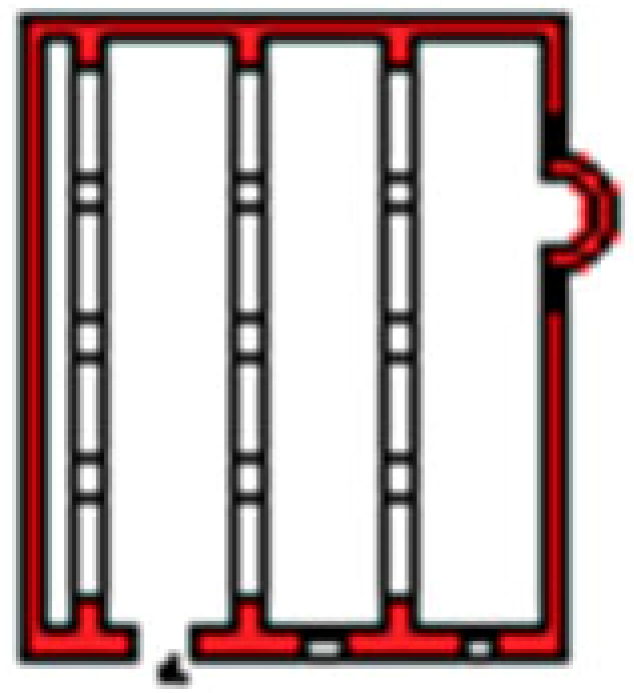

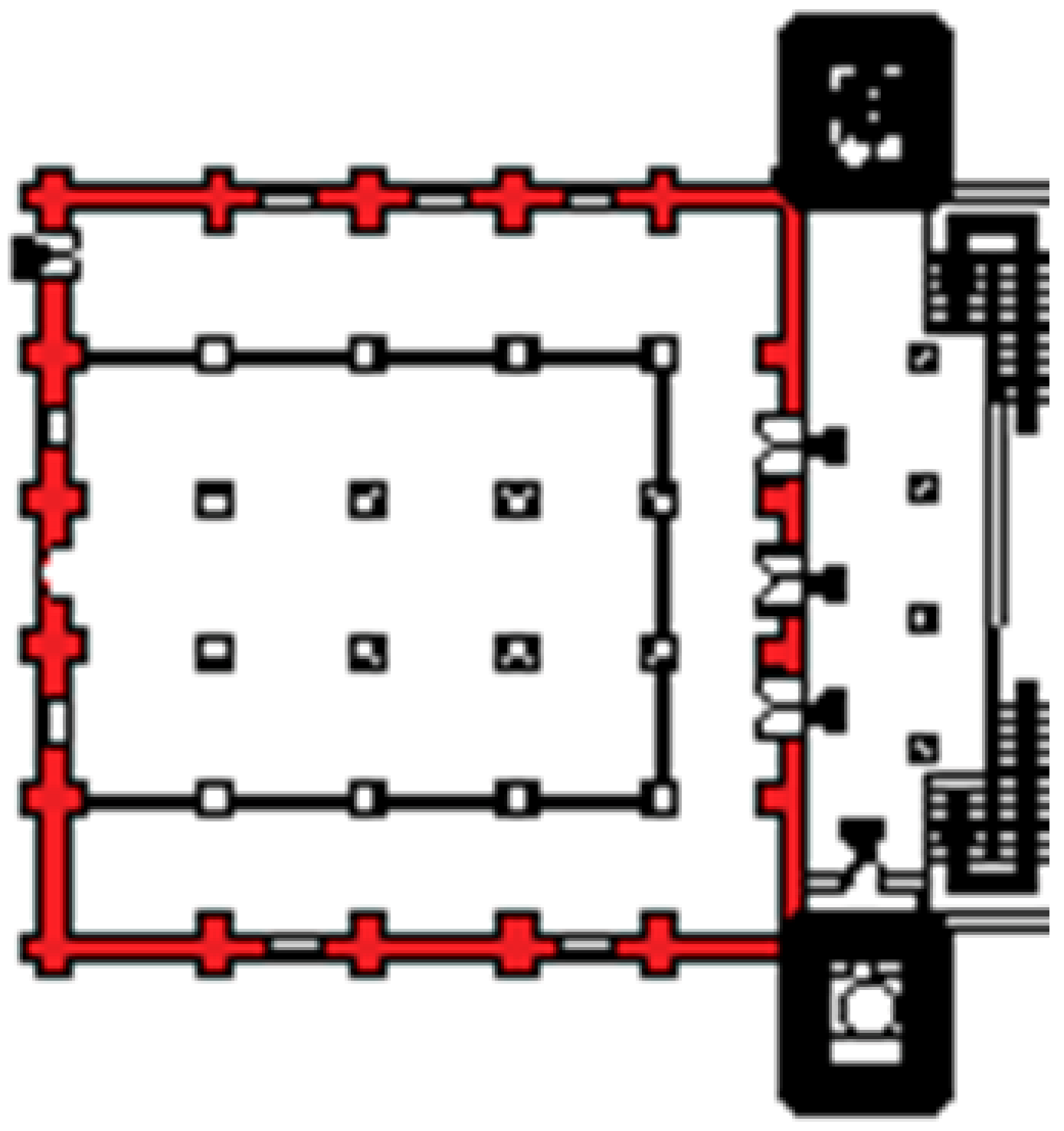

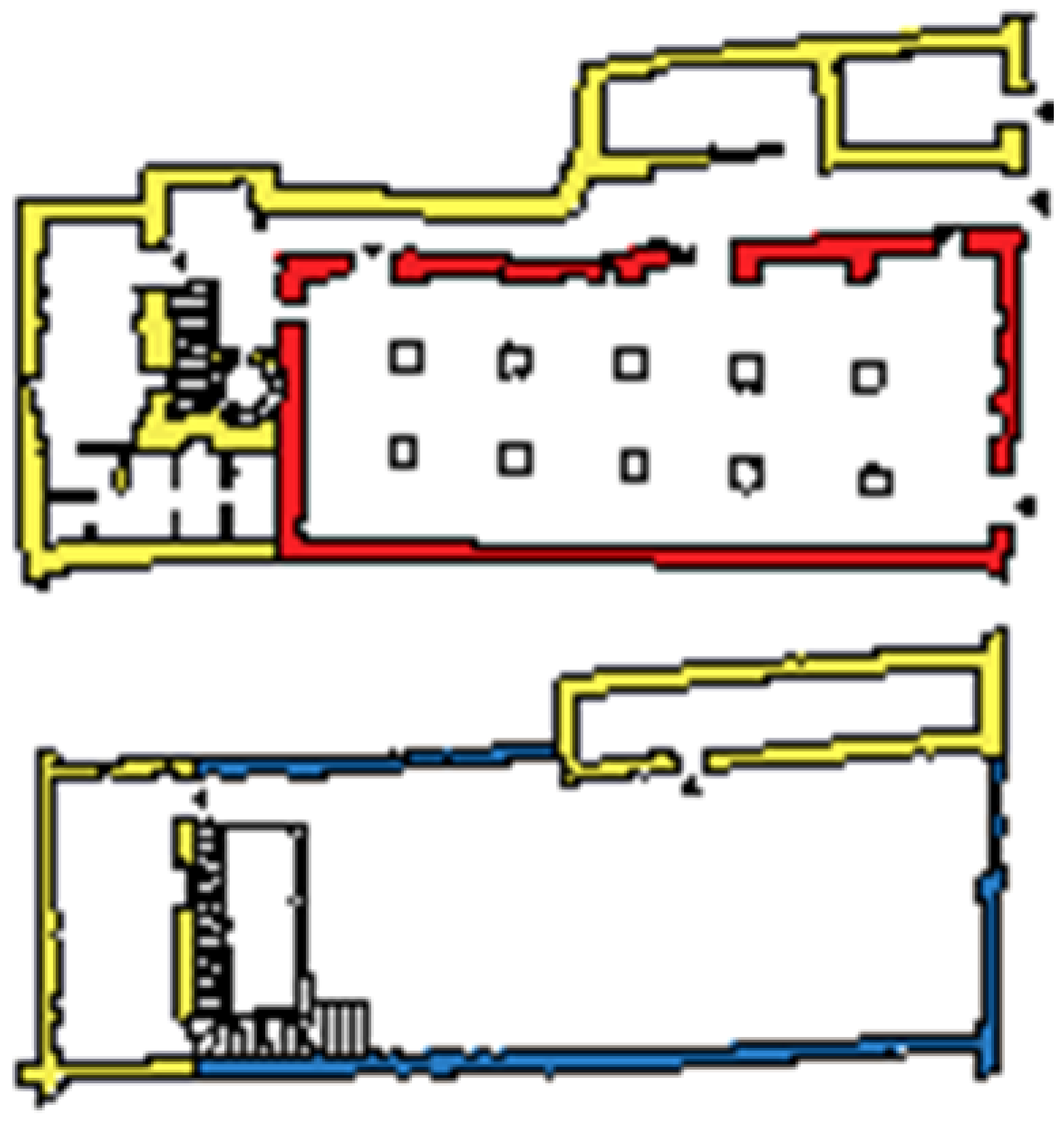

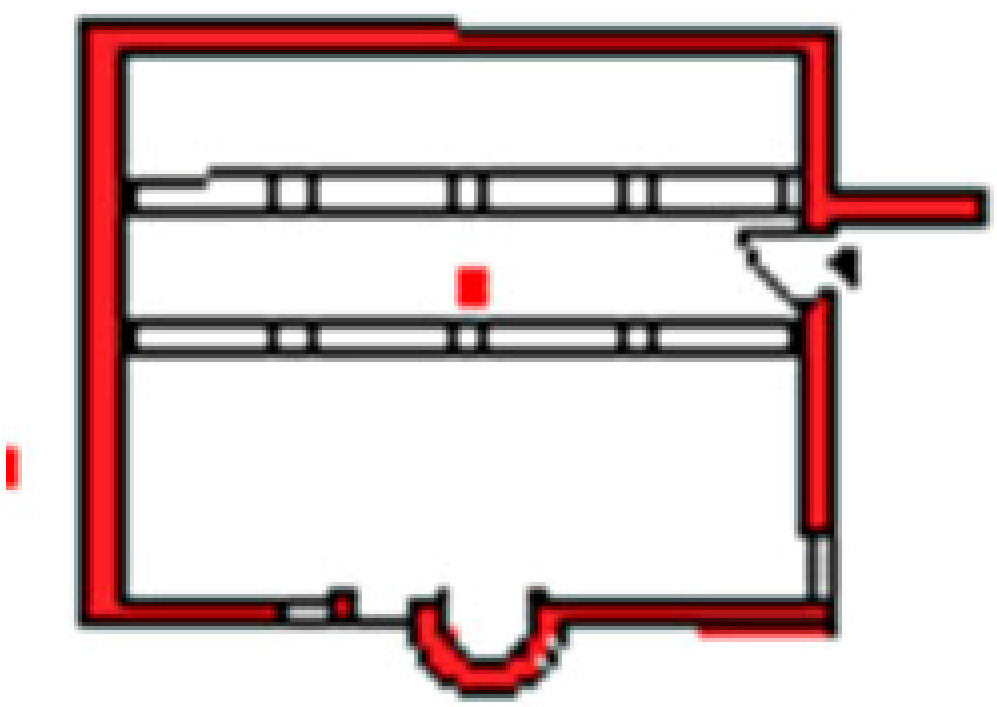

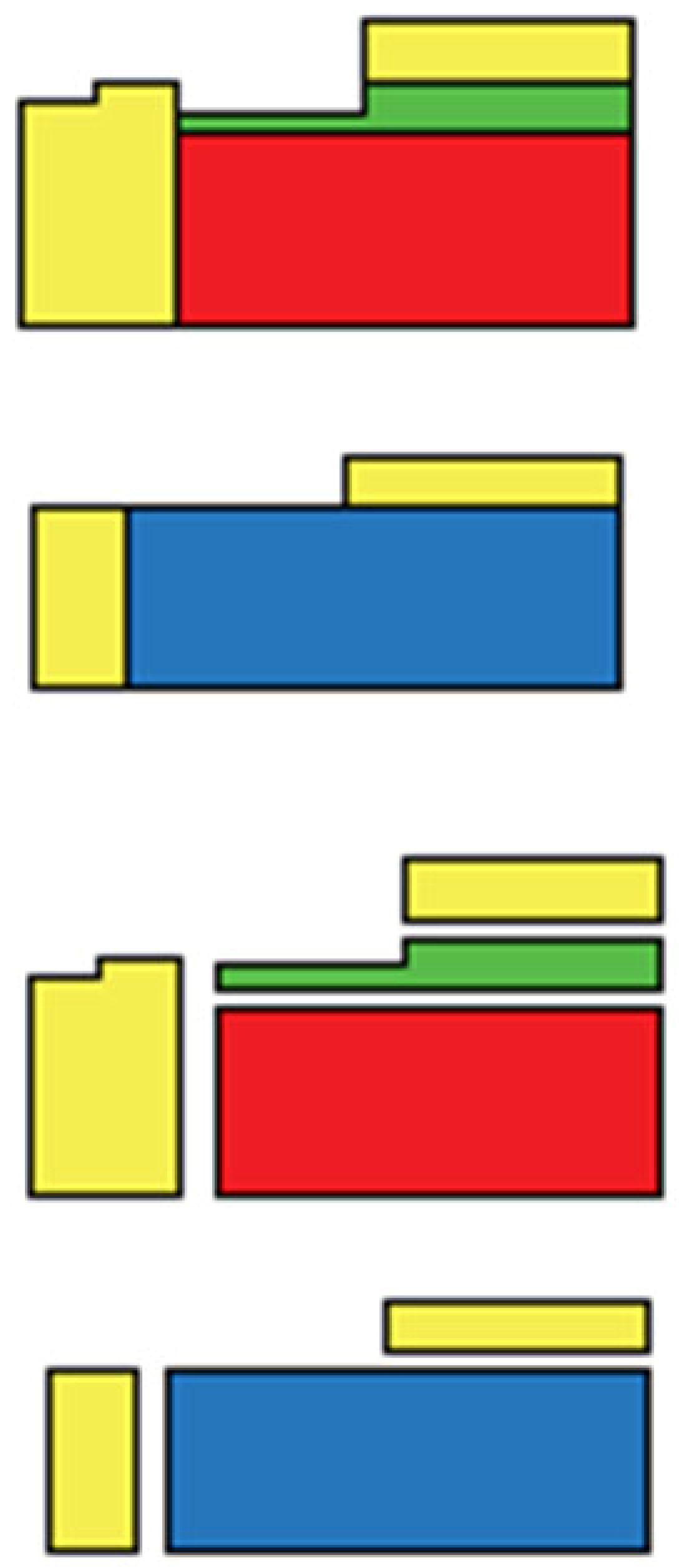

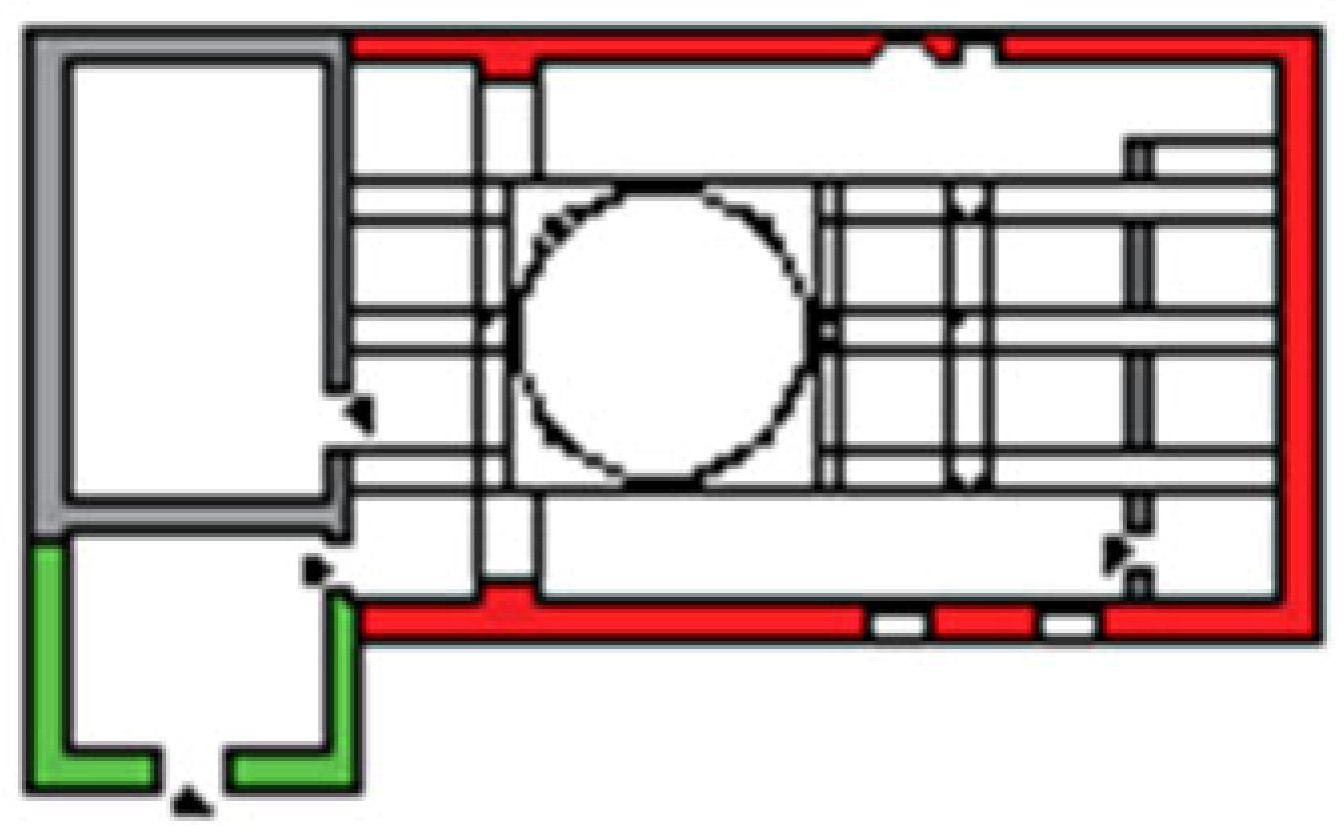

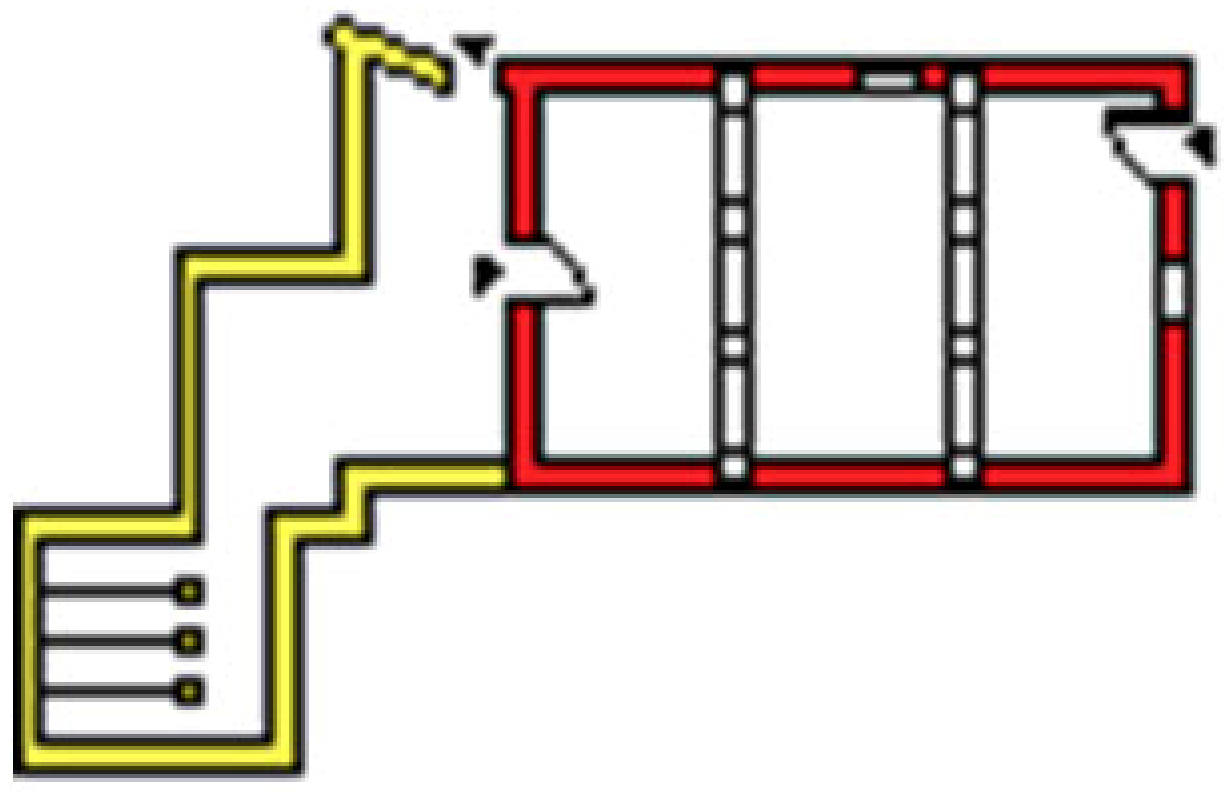

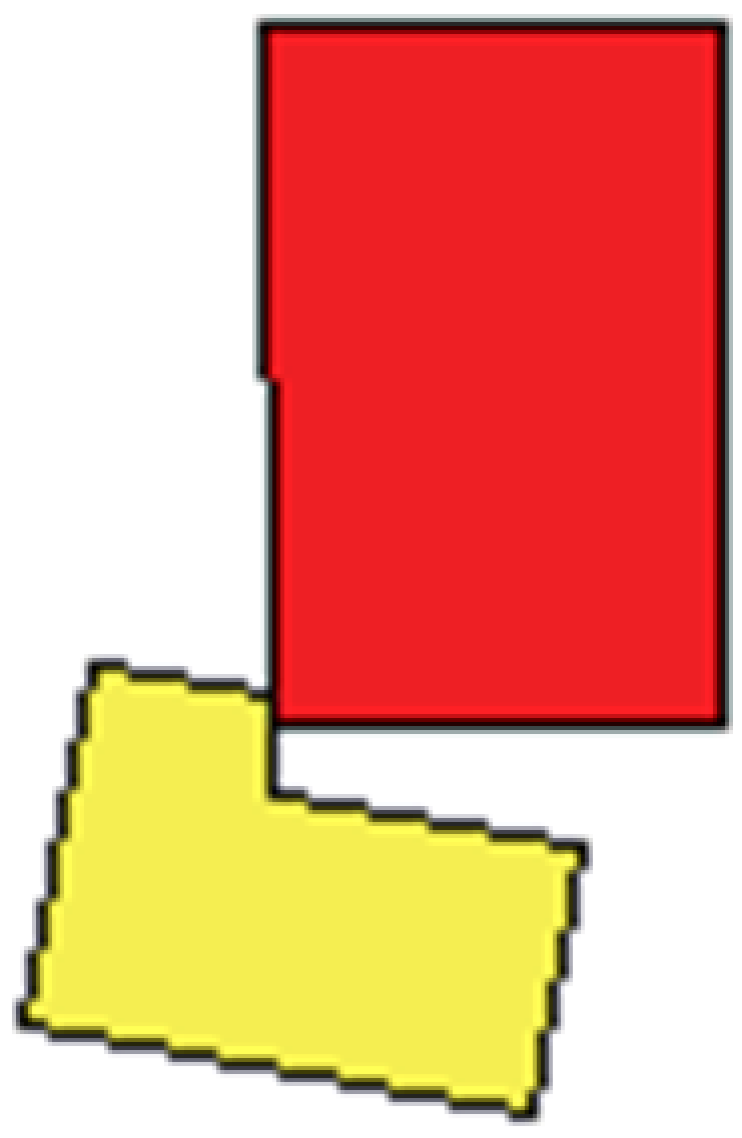

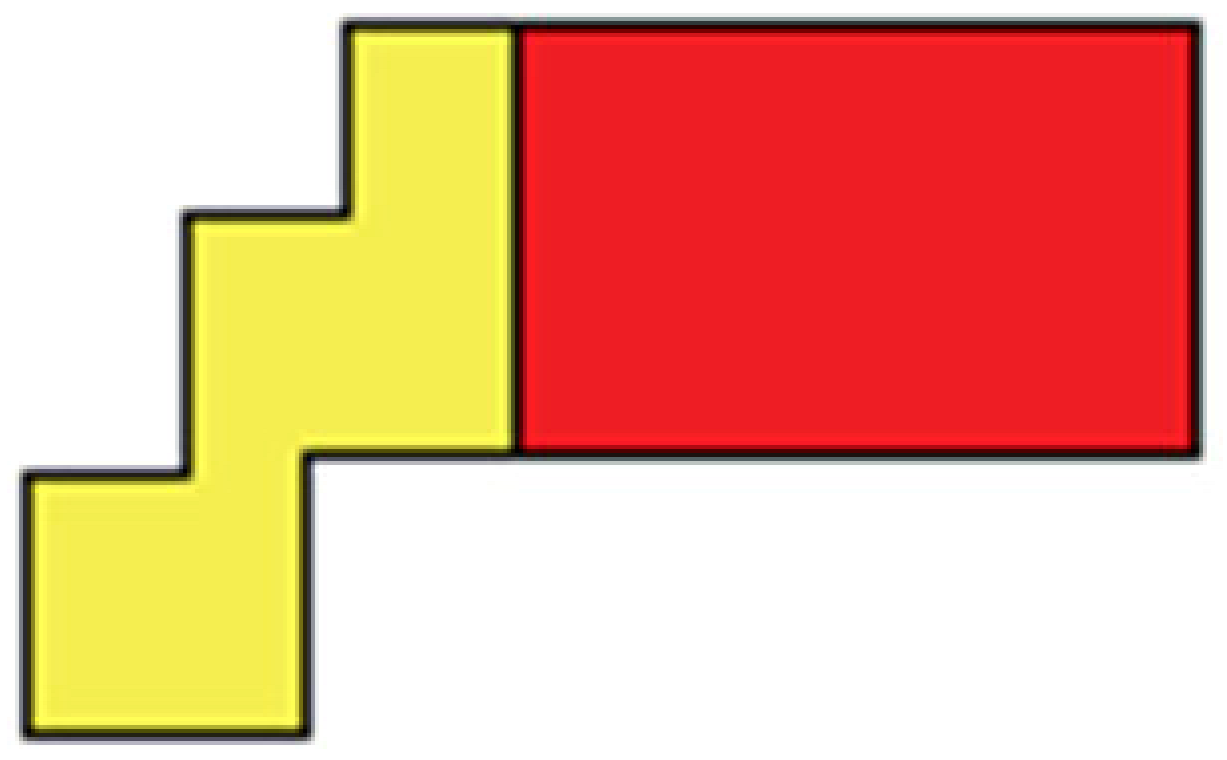

| Spatial Plans of Vernacular Mosques of Djebel Amour |

|---|

| Precolonial specimens (11th–19th centuries) |

|

| Colonial specimens (19th–20th centuries) |

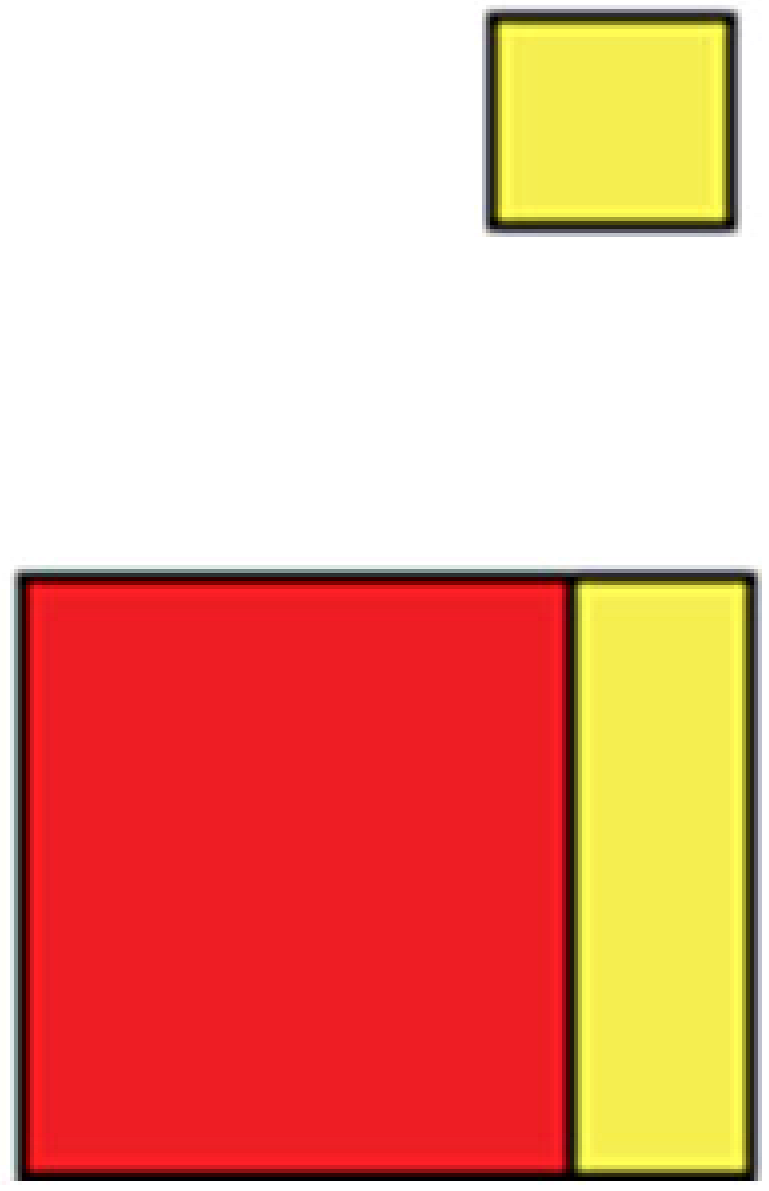

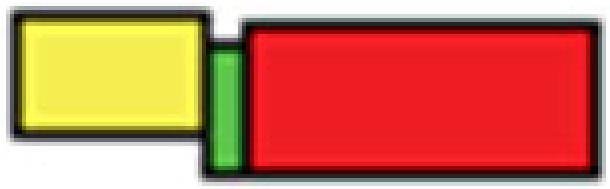

Legend: (1) Prayer Hall, (2) Courtyard, (3) Minaret, (4) Mausoleum, (5) Annexes |

| Identification specimens |

| (S1) Al-Atik Mosque in Ain Madhi (11th century); (S2) Sidi Bouzid Mosque (12th century); (S3) Al-Atik in Laghouat Mosque (12th century); (S4) Al-Atik Tadjmout Mosque (16th–17th centuries); (S5) Ouled Saci Mosque after reconstruction (19th century); (S6) Taouti Mosque (1864); (S7) Safah Mosque (1874); (S8) Abdelkader Djilali Mosque (1872); (S9) Khalifa or Ahlaf Mosque after conversion (20th century); (S10) Ouled Turki Mosque (XIX-XX); (S11) El-Atik Mosque in Haouita after reconstruction (1936); (S12) El-Atik Mosque in Tadjrouna after reconstruction (19th century); (S13) Mohamed Sidi Mohamed El-Habib Tidjani in Ain Madhi (19th century); (S14) El-Houda Mosque in Tadjmout (19th century). |

| Category | Origin/Author (s) | Nature/Field of Study | Main Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical sources | Field surveys (2023–2025) | Survey sheets (date, location, morphology, materials, conservation status, interventions) | Identification of historical and morphological characteristics |

| Photogrammetric documentation (Canon EOS 750D, Agisoft Metashape) | Orthophots, point clouds, textured 3D models | Metric accuracy, support for morphological reconstruction | |

| Archives: Directorate of Culture, Directorate of Religious Affairs and Waqf and ONPCAS Travel accounts: M. Marey, 1846; E. Fromentin, 1857; E. Dermenghem, 1960; O. Petit, 1976; G. Hirtz, 1989 [32,33,34,35,36] Recent authors: M. Labter, 2020; A. Saoudi, 2020; K. Sonne; 2020 and L. Labter, 2021 [38,39,40,41] | Reports, articles and documentary sources | Historical context, transformations, evolution of uses | |

| Iconographic documents: Delcampe; E. Cat 1892 [42] | Old maps, photographs, | Verification and enrichment of surveys and archival sources | |

| Interviews and field observations: inhabitants, experts and visits 2022–2025 | Oral testimonies and direct observations | Chronology, tribal identity, external influences | |

| Typological and morphological references | Previous university studies: Habboul, 2011, Takhi, 2018; Mahcer et al. 2018; O. Talha, 2018; T. Haizoum, 2018; Rabhi, 2018; Chettih, 2019 [43,44,45,46,47,48,49] Archives: PPSMVSS Monographs: Hamlaoui, 2006 [28] | Theses and archival documents | Scientific support for morphological restitution and corpus selection |

| Muratori, Rossi, Aymonino, Caniggia (1960s–1980s); Panerai (1980s–2000s) [50] | Italian and French typo-morphology schools | Foundations and adaptation of the typo-morphological approach | |

| Othman et al., 2008 [55]; M. Redjem 2014 [56]; M. Loukma & M. Stefanidou, 2017 [58]; Budi & Wibowo, 2018; Elkhateeb et al., 2018; Mustapha & Ismael, 2019; Redjem & Mazouz, 2022; Asim & Hajime., 2022; Fakriah, N. 2022 [11,59,60,61,62,63]; Abubakr Ali & Mustapha, 2023 [53] | International studies on historical and traditional mosques | Comparative typological analysis | |

| Duprat and Paulin, 1989; Sriti. L, 1996; 2013 [65,66,67]; I. Msadek, 2012 [72]; H. Gaci 2012 [51]; I. Cherif & N. Allani-Bouhoula, 2015 [57]; Chakroun, 2016 [68]; I. Cherif & N. Allani-Bouhoula, 2017 [73]; Zerari et al., 2020; Benabadji & Bencherif 2020; Beldjilali et al., 2024 [69,70,71]; Zerari et al., 2024 [22] | Mosques of the Maghreb | Morphological analysis (classification and minaret studies) | |

| J. Schacht, 1954 [78]; Bourouiba, 1983–1986 [74,75]; V. Prévost, 2009; N. Benkari, 2018 [76,77,81]; Sriti et al., 2018 [79]; Zerari, 2021 [80] | Monumental and Ibadi mosques | Comparative historical and Saharan studies | |

| A. Hamlaoui, 2006 [28]; O. Talha, 2018; T. Haizoum, 2018; Rahbhi, 2018; Chettih, 2019 [46,47,48,49] | Vernacular mosques of Djebel Amour | Initial local and partial studies |

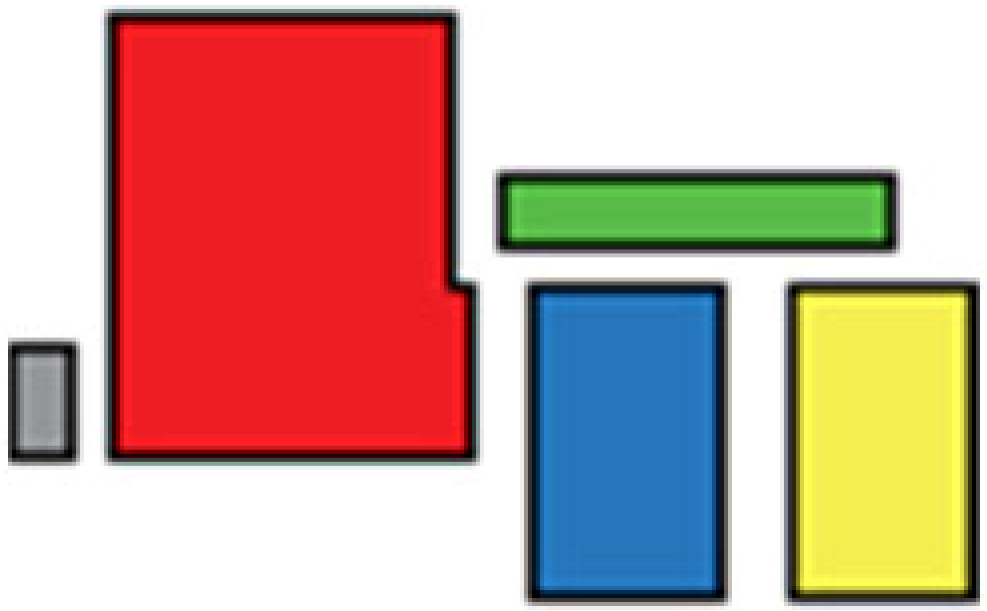

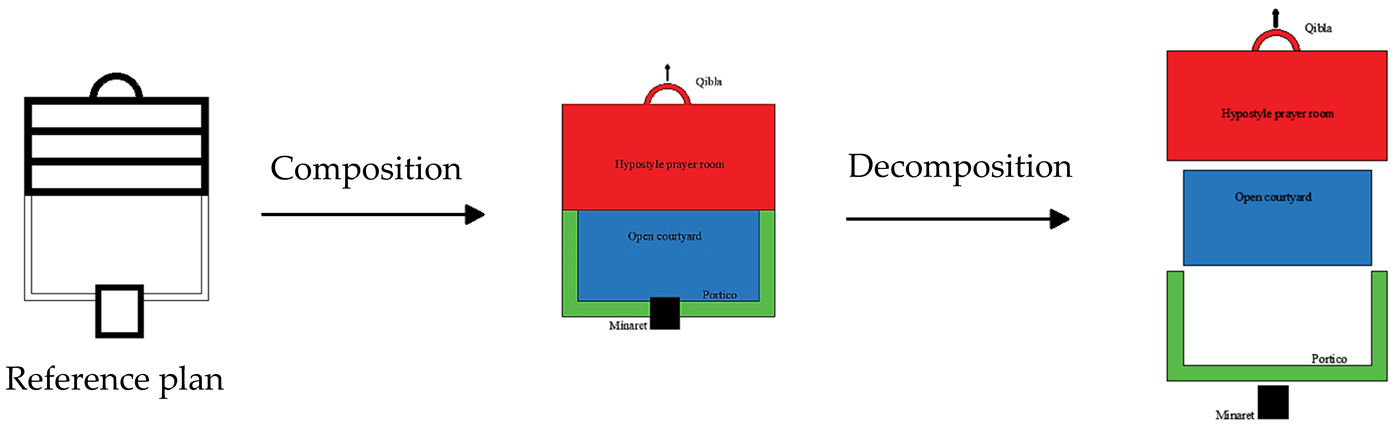

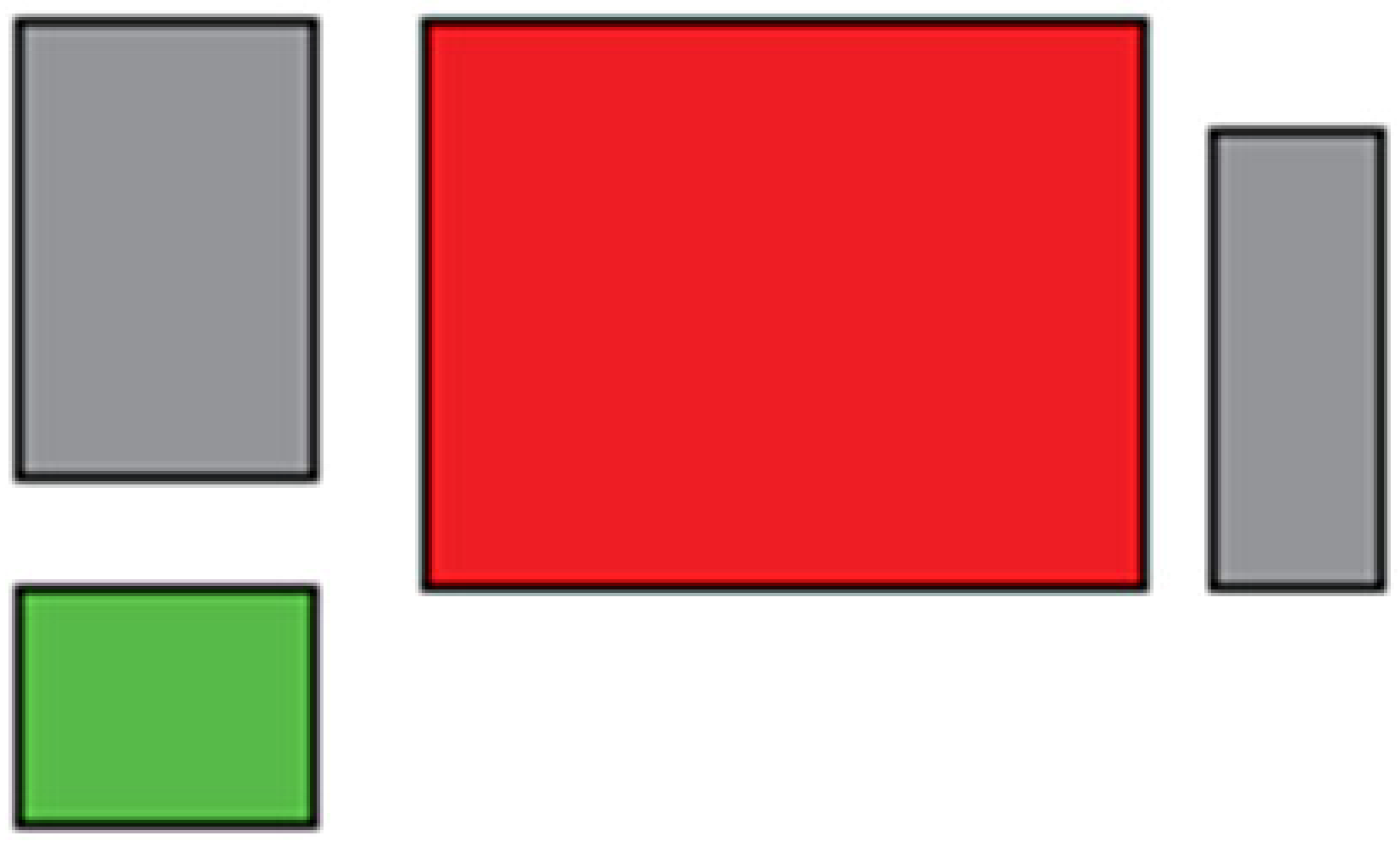

| Reference model |  | ||||

| Period | Precolonial period (11th–19th) centuries | ||||

| Mosques codes | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

| Mosques plans |  |  |  |  |  |

| Composition and Decomposition of mosques |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  | |

| Morphological components | Prayer hall | ||||

| X | X | X | X | X | |

| Courtyard | |||||

| / | / | / | X | / | |

| Portico | |||||

| X | / | / | X | X | |

| Minaret | |||||

| / | / | / | / | / | |

| Type of prayer hall | Deeper than wide/aisles perpendicular to the Qibla wall | wider than deep/aisles perpendicular to the Qibla wall | Square | Wider than deep/aisles parallel to the Qibla wall | Wider than deep/no aisles |

| Variables/Criteria | Topological relationship (prayer hall/courtyard) | ||||

| No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyard (Absence) | The courtyard on one side of the prayer hall (Adjacency) | No courtyad (Absence) | |

| Absence/presence of the portico | |||||

| Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | No portico (Absence) | No portico (Absence) | Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | |

| Number and position of the minaret in relation to the mosque | |||||

| No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | |

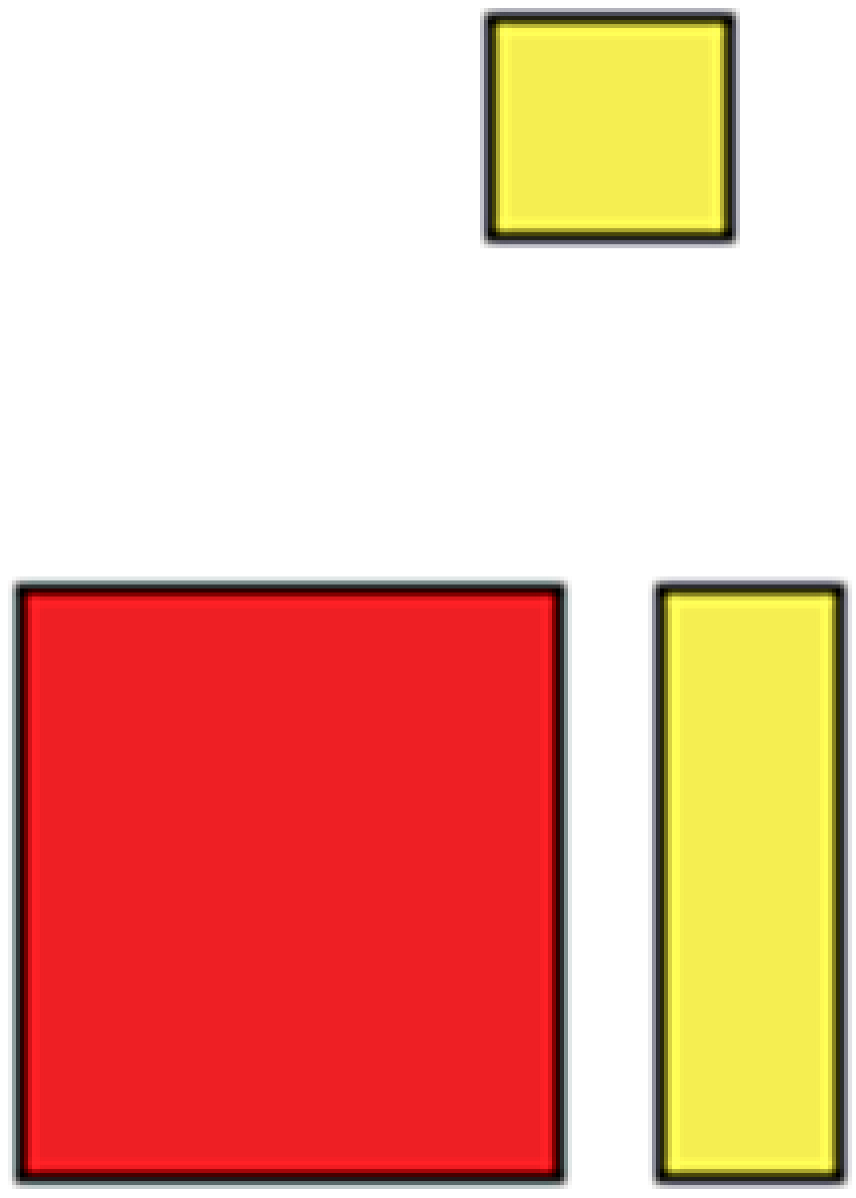

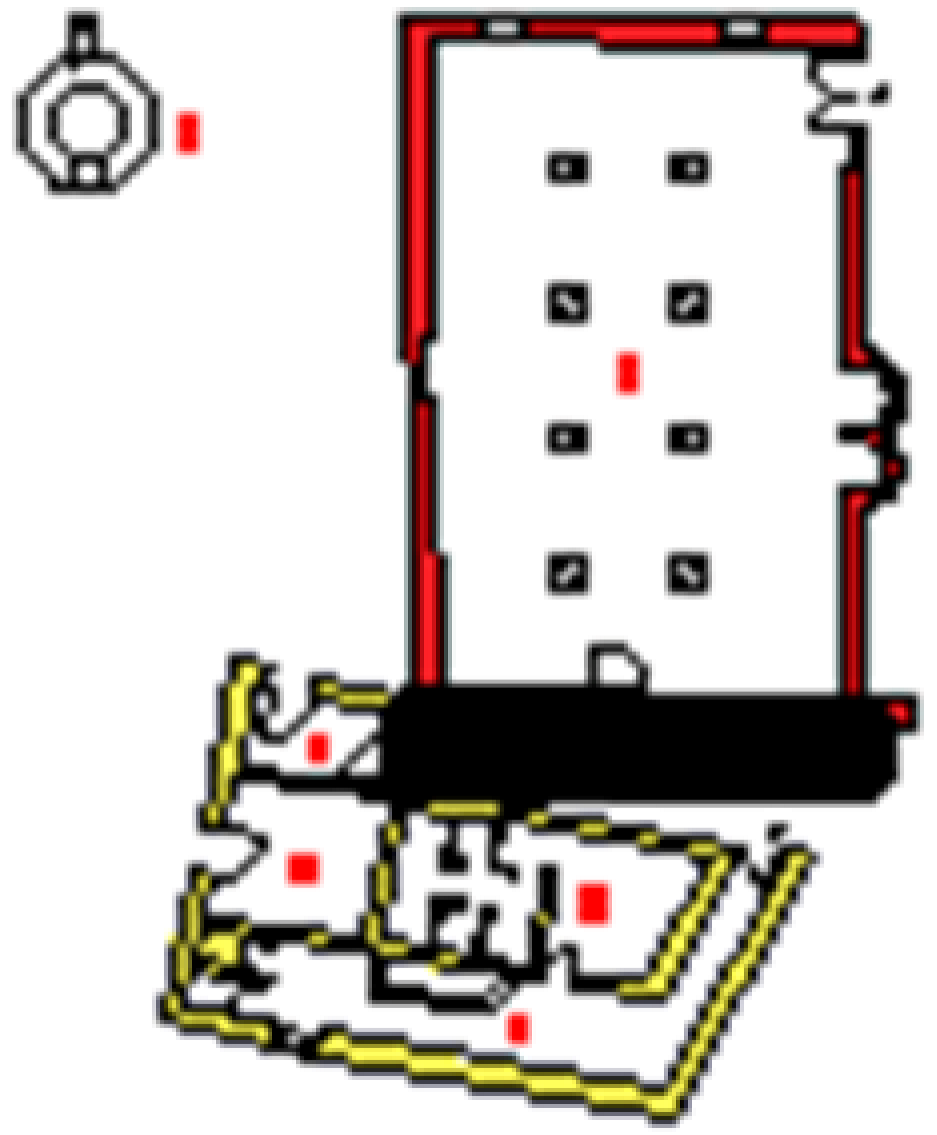

| Reference model |  | |||||

| Period | Colonial period (19th–20th) centuries | |||||

| Mosques codes | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | |

| Mosques plans |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Composition and Decomposition of mosques |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Morphological components | Prayer hall | |||||

| X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Courtyard | ||||||

| / | / | X | / | / | ||

| Portico | ||||||

| / | X | X | X | / | ||

| Minaret | ||||||

| / | X | / | X | / | ||

| Type of prayer hall | Wider than deep/aisles parallel to the Qibla wall | Square | Wider than deep/aisles parallel to the Qibla wall | Wider than deep/aisles parallel to the Qibla wall | Wider than deep/aisles parallel to the Qibla wall | |

| Variables/Criteria | Topological relationship (prayer hall/courtyard) | |||||

| No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyard (Absence) | The courtyard is superimposed onto the prayer room (Superposition) | No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyad (Absence) | ||

| Absence/presence of the portico | ||||||

| No portico (Absence) | Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | No portico (Absence) | ||

| Number and position of the minaret in relation to the mosque | ||||||

| No minaret (Absence) | Minaret is outside of the entire mosque with two minarets | No minaret (Absence) | Minaret on one side of the entire mosque with one minaret | No minaret (Absence) | ||

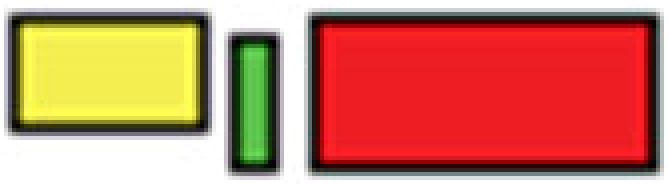

| Period | Colonial period (19th–20th) centuries | |||||

| Mosques codes | S11 | S12 | S13 | S14 | ||

| Mosques plans |  |  |  |  | ||

| Composition and Decomposition of mosques |  |  |  |  | ||

|  |  |  | |||

| Morphological components | Prayer hall | |||||

| X | X | X | X | |||

| Courtyard | ||||||

| / | / | / | / | |||

| Portico | ||||||

| / | / | X | / | |||

| Minaret | ||||||

| / | / | / | / | |||

| Type of prayer hall | Wider than deep/aisles parallel to the Qibla wall | Square | Wider than deep/aisles perpendicular to the Qibla wall | Wider than deep/aisles perpendicualr to the Qibla wall | ||

| Variables/Criteria | Topological relationship (prayer hall/courtyard) | |||||

| No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyard (Absence) | No courtyad (Absence) | |||

| Absence/presence of the portico | ||||||

| No portico (Absence) | No Portico (Absence) | Portico is in front of the entrance to the prayer hall (Presence) | No portico (Absence) | |||

| Number and position of the minaret in relation to the mosque | ||||||

| No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | No minaret (Absence) | |||

| Region/Corpus | Total Mosques | Courtyard Presence (Count) | Courtyard Presence (%) | Portico Presence (Count) | Portico Presence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djebel Amour | 14 | 2 | 14.3% | 7 | 50% |

| Souf | 5 | 3 | 60% | 4 | 80% |

| Al-Khabra (Saudi) | 2 | 2 | 100% | 2 | 100% |

| Erbil (Iraq) | 5 | 5 | 100% | 4 | 80% |

| West Sumatra (Indonesia) | 25 | 24 | 96% | Not applicable | — |

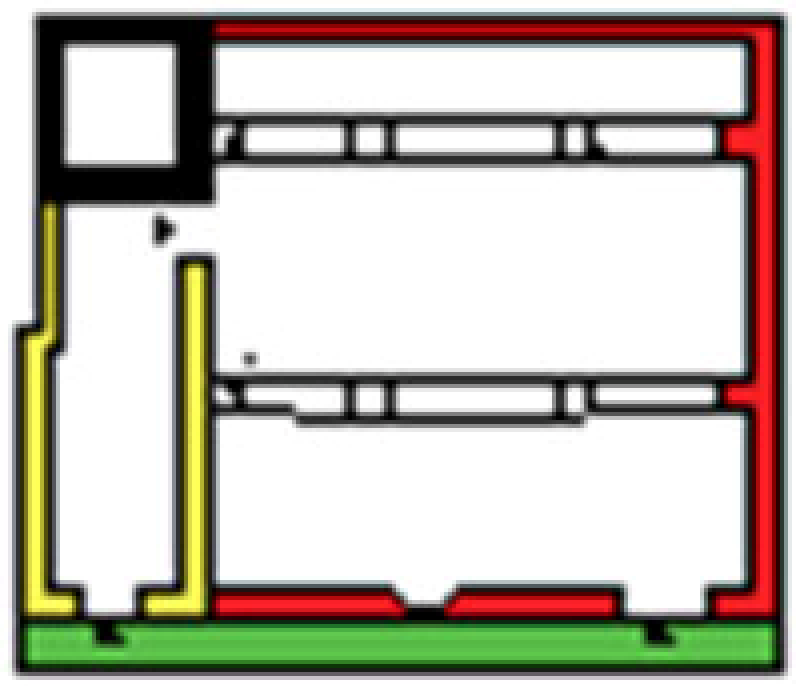

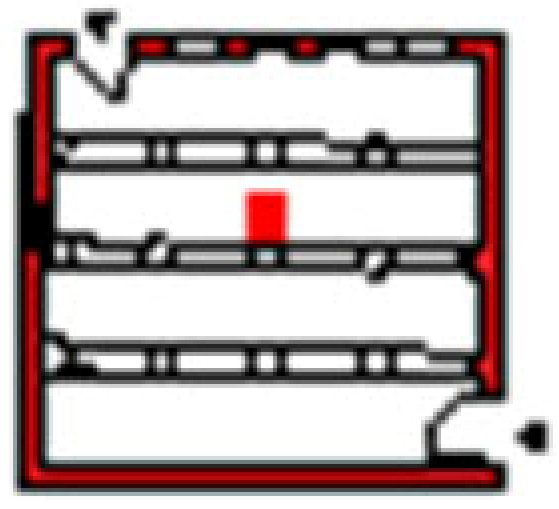

| Segmentation of the minaret architecture by Reference model |  | ||

| Period | Colonial period (19th–20th) centuries | ||

| Mosques and minarets codes | S7 | S9 | |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| Segmentation of the minaret architecture in the Djebel Amour |  |  | / |

| Note: Minaret M3 of Mosque S9—Presented as a figure due to insufficient data regarding its exact dimensions and architectural details. | |||

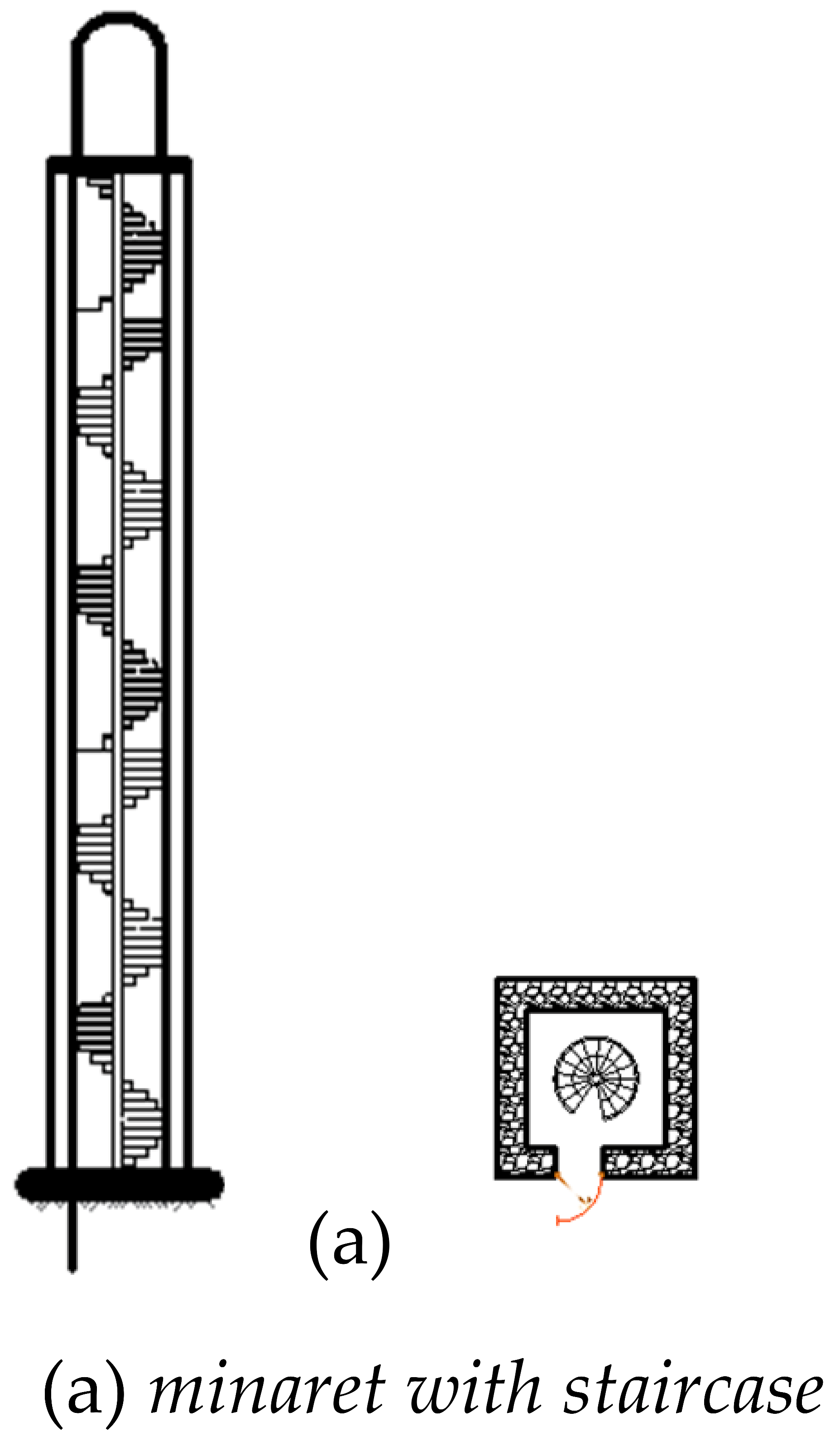

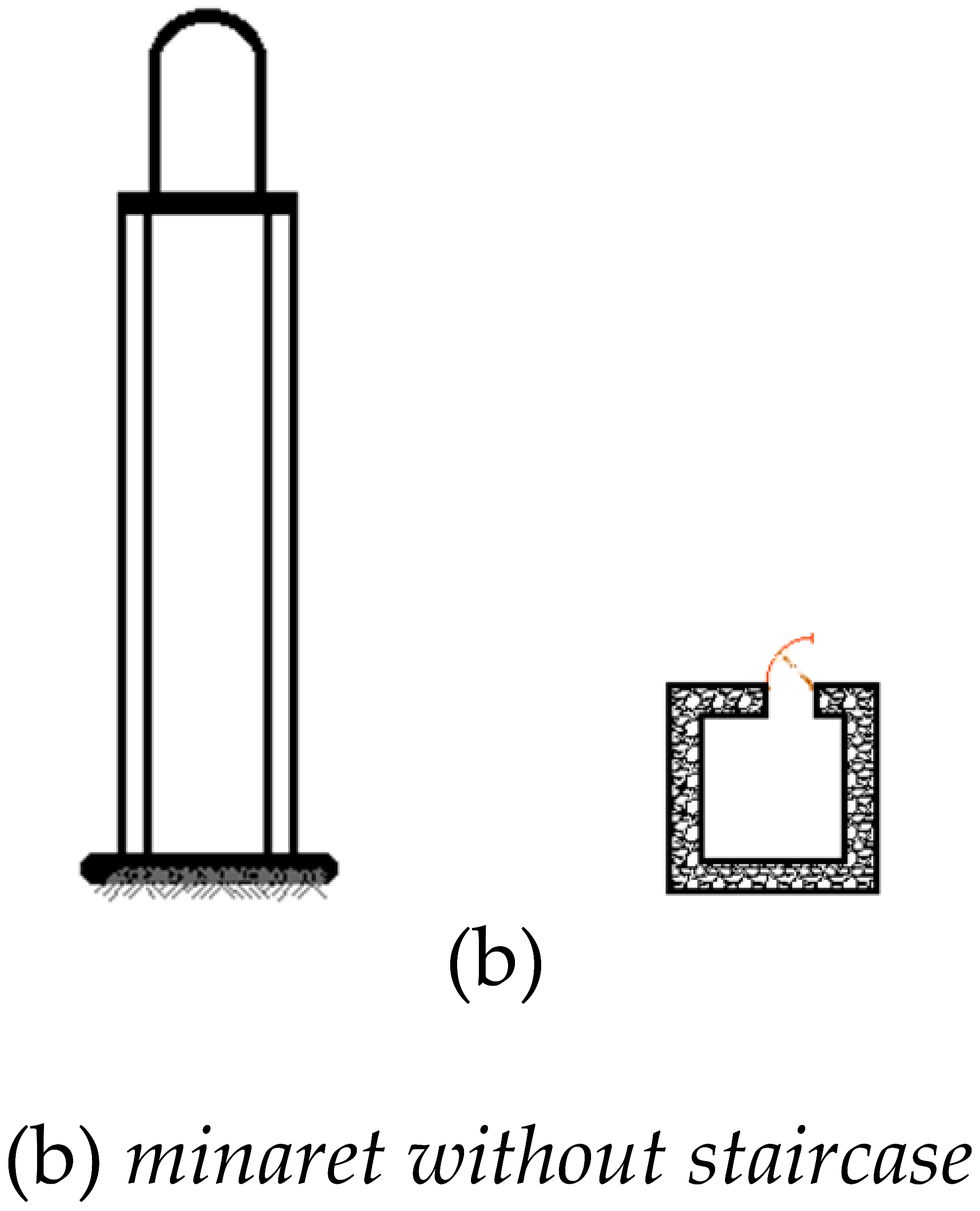

| Section and elevation showing the presence and absence of staircase of minaret |  |  | |

| Variables/criteria of the minaret in the colonial period | Presence/Absence of the balcony/gallery (segment 2) | ||

| Presence Absence Presence | |||

| Presence/Absence of the lantern (Segment 3) | |||

| Presence Presence Presence | |||

| Region | Total Mosques Considered | Staircase Minaret (Count) | Staircase Minaret (%) | Monumental Minaret (Count) | Monumental Minaret (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djebel Amour | 14 | 4 | 28.6% | 3 | 21.4% |

| Souf | 5 | 3 | 60.0% | 0 | 0% |

| Al Khabra (Saudi Arabia) | 2 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 100% |

| Erbil (Iraq) | 5 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mekki, S.; Arigue, B.; Santi, G.; Sriti, L.; Pace, V.; Leporelli, E. Tracing the Morphogenesis and Formal Diffusion of Vernacular Mosques: A Typo-Morphological Study of Djebel Amour, Algeria. Buildings 2025, 15, 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234277

Mekki S, Arigue B, Santi G, Sriti L, Pace V, Leporelli E. Tracing the Morphogenesis and Formal Diffusion of Vernacular Mosques: A Typo-Morphological Study of Djebel Amour, Algeria. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234277

Chicago/Turabian StyleMekki, Sana, Bidjad Arigue, Giovanni Santi, Leila Sriti, Vincenzo Pace, and Emanuele Leporelli. 2025. "Tracing the Morphogenesis and Formal Diffusion of Vernacular Mosques: A Typo-Morphological Study of Djebel Amour, Algeria" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234277

APA StyleMekki, S., Arigue, B., Santi, G., Sriti, L., Pace, V., & Leporelli, E. (2025). Tracing the Morphogenesis and Formal Diffusion of Vernacular Mosques: A Typo-Morphological Study of Djebel Amour, Algeria. Buildings, 15(23), 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234277