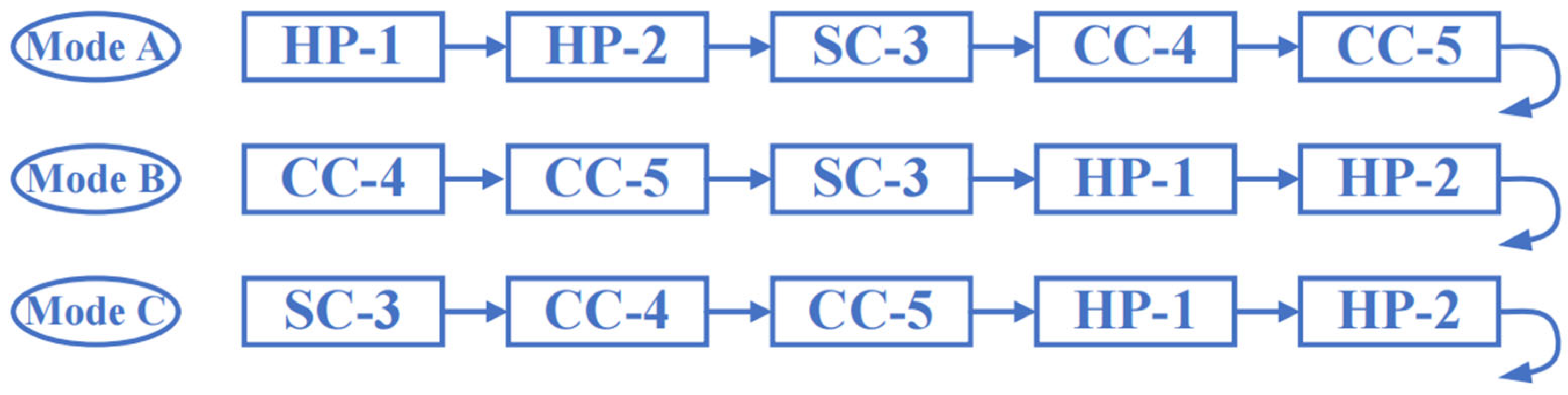

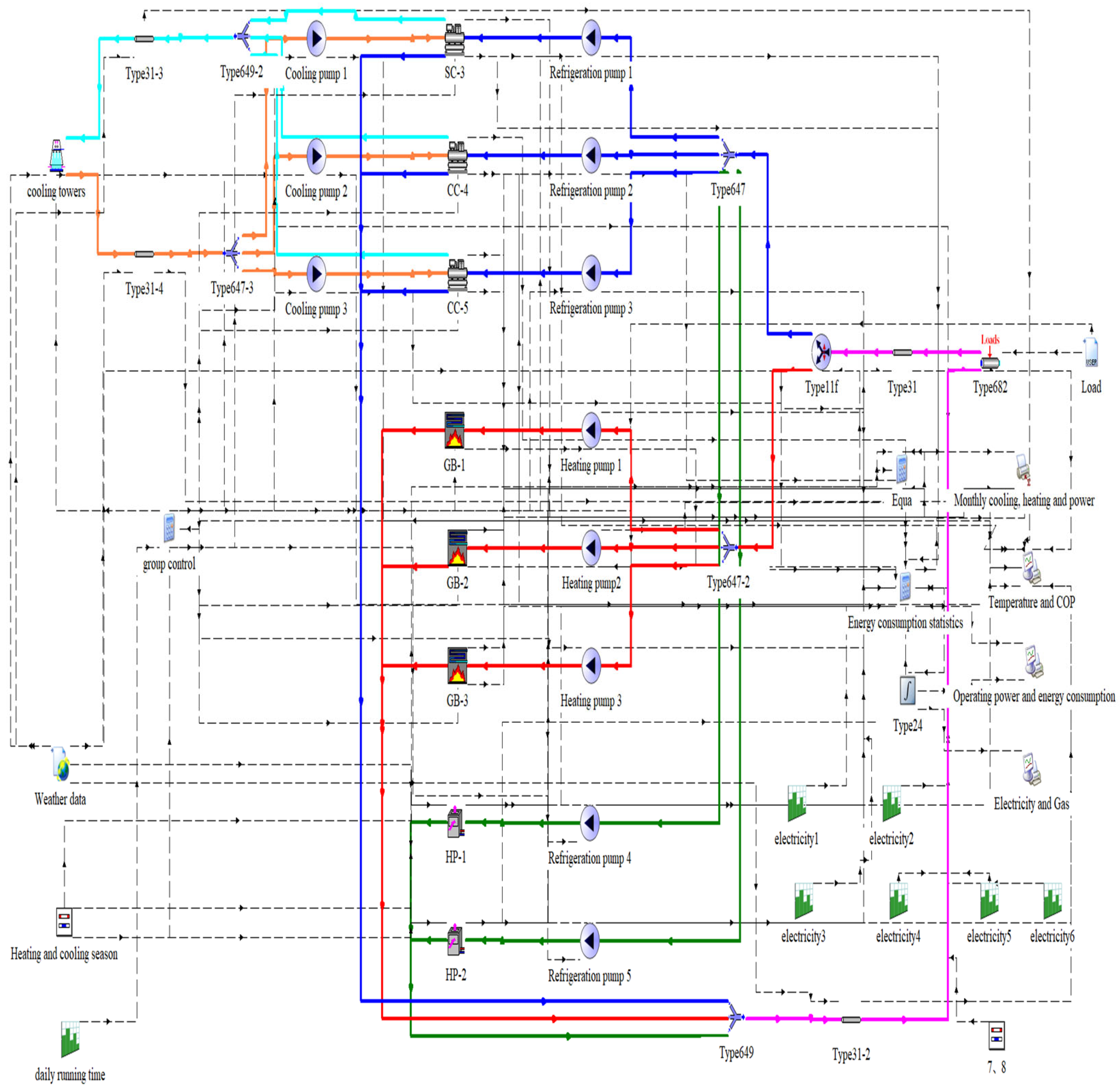

4.1. Cooling Source System Unit

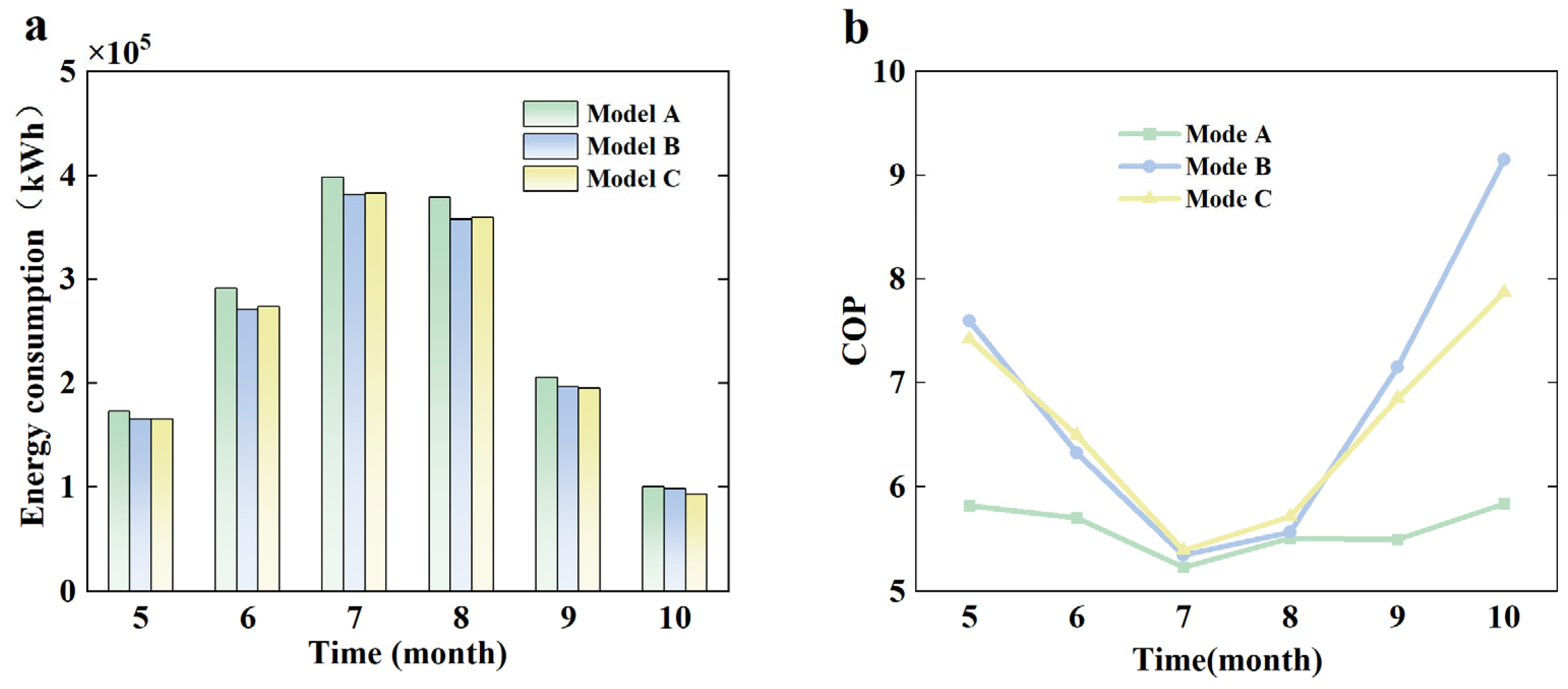

Figure 7 displays the calculated results and comparisons of monthly energy consumption and energy efficiency ratios under different strategies during the cooling season.

Figure 8 presents the total energy consumption and the overall energy efficiency ratio of the system.

From

Figure 7, it can be seen that a significant performance gap between Mode A and the other two strategies, Mode B and Mode C. As a result, Mode A is excluded from further consideration. Mode B offers both improved economic performance and greater energy-saving potential.

From

Figure 8, it can be seen that monthly analysis reveals that the energy consumption differences between Mode B and Mode C remain minimal from May to August. During this period, both strategies exhibit stable system performance. However, in September and October, Mode B shows a clear advantage. Notably, the system COP under Mode B reaches a peak value of 9.15 in October.

In terms of total energy consumption, Mode B outperforms Mode C, although the difference is marginal at 527.82 kWh. From an energy-saving perspective, Mode B demonstrates superior performance. System efficiency, measured by COP, further confirms this trend. Mode B achieves a higher overall COP of 6.85, indicating better energy utilization and enhanced operational efficiency.

The control logic for Mode B is based on sequential activation of chiller units in response to varying cooling loads. The strategy segments load demand into five intervals, each corresponding to a distinct combination of operating units. The objective is to optimize energy efficiency while ensuring sufficient cooling capacity under varying load conditions.

For the cooling season (Mode B): the energy efficiency improvement (4.72%) primarily stems from two factors:

Reducing operating hours of inefficient equipment: this strategy prioritizes running high-efficiency centrifugal chillers (CC-4, CC-5) for extended periods whenever possible, thereby delaying or reducing operating hours for low-COP air-source heat pumps (HP-1, HP-2).

Optimizing equipment part-load operation: by setting reasonable start/stop thresholds, operating equipment is maintained within high-efficiency part-load ranges whenever possible, avoiding inefficient simultaneous low-load operation of multiple units. The cooling tower control strategy (maintaining proximity) indirectly optimizes condensing temperature, though its contribution is relatively minor in this scheme.

Table 9 summarizes the load-based segmentation and corresponding unit activation logic.

Under the Mode B control strategy, the chiller system of the Xiaogan Olympic Sports Center exhibited distinct operational patterns across different cooling load intervals during the cooling season.

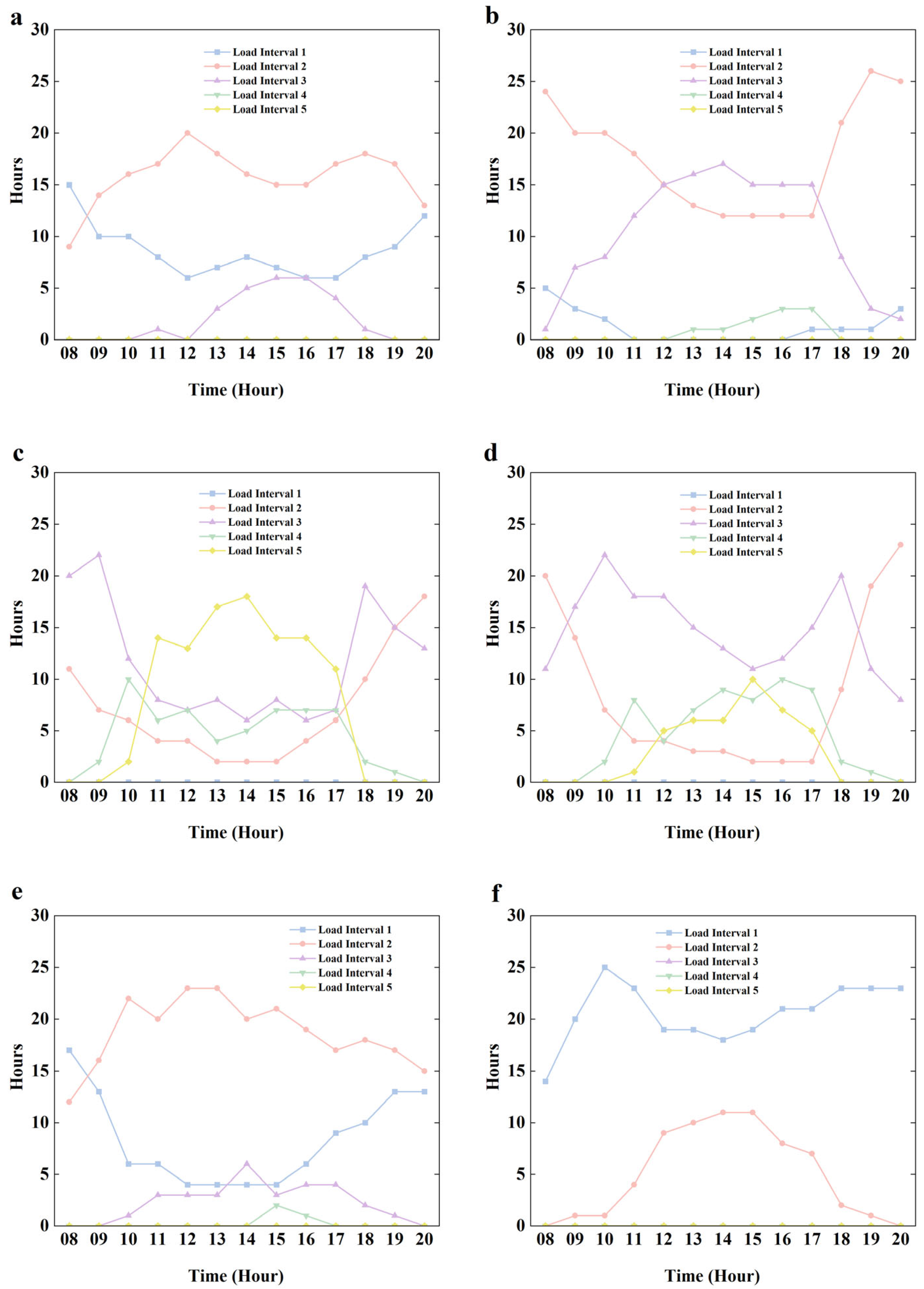

Figure 9 illustrates the monthly hourly distribution of operating zones.

From

Table 9 and

Figure 9, it can be seen that in May, the system primarily operated in Load Interval 2, with a total of 205 h. The peak operation hours were observed between 09:00 and 20:00. Load Interval 1 was active for 112 h, with the peak at 08:00. Therefore, in May, Unit CC-4 will start from 8:00 to 9:00, and Units CC-4 and CC-5 will start from 9:00 to 20:00.

In June, Load Interval 2 recorded 230 operating hours, with hourly peaks between 08:00 and 12:00 and 18:00–20:00. Load Interval 3 was active for 134 h, peaking between 12:00 and 18:00. Therefore, in June, Units CC-4 and CC-5 will be started from 8:00 to 12:00, Units SC-3, CC-4, and CC-5 will be started from 12:00 to 18:00, Units CC-4 and CC-5 will be started from 18:00 to 20:00.

In July, the system operated in Load Interval 2 for 91 h, with a peak between 19:00 and 20:00. Load Interval 3 showed 151 h of operation, peaking between 08:00 and 11:00 and 18:00–19:00. Notably, Load Interval 5 ran for 103 h, with significant peaks between 11:00 and 18:00. Therefore, in July, Units SC-3, CC-4, and CC-5 will be started from 8:00 to 11:00, Units HP-1, HP-2, SC-3, CC-4, and CC-5 will be started from 11:00 to 18:00, Units SC-3, CC-4, and CC-5 will be started from 18:00 to 19:00, Units CC-4 and CC-5 will be started from 19:00 to 20:00.

In August, Load Interval 2 was active for 112 h, with hourly peaks at 08:00 and again between 19:00 and 20:00. Load Interval 3 recorded 191 h, peaking from 09:00 to 19:00. Therefore, in August, Units CC-4 and CC-5 will be started from 8:00 to 9:00, Units SC-3, CC-4, and CC-5 will be started from 9:00 to 19:00, Units CC-4 and CC-5 will be started from 19:00 to 20:00.

In September, Load Interval 2 reached its highest monthly utilization at 243 h, with a consistent hourly peak from 09:00 to 20:00. Load Interval 1 was also significant with 191 h, peaking at 08:00. Therefore, in September, Unit CC-4 will start from 8:00 to 9:00, Units CC-4 and CC-5 will be started from 9:00 to 20:00.

In October, the system mainly operated in Load Interval 1, with a total of 268 h. The hourly distribution was uniformly high throughout the day, indicating full-day operation between 08:00 and 20:00. Therefore, in September, Unit CC-4 will be started from 8:00 to 20:00.

These trends are closely related to seasonal thermal loads and occupancy behavior. During peak summer months, extended use of higher load intervals reflects increased cooling demand due to both higher ambient temperatures and longer facility operating hours. In contrast, transitional months like May and October show greater reliance on low-load operation intervals, suggesting milder external conditions and reduced internal load intensities.

In large sports centers, traditional fixed operation schedules cannot accommodate demand fluctuations caused by time changes due to the uncertainty of event dates. Therefore, a day-by-day control strategy has been proposed to enable flexible management during cooling and heating seasons. This strategy dynamically adjusts the start-up and shutdown of the heating and cooling source units to ensure comfort while saving energy. It provides a reference for operations and maintenance personnel at Xiaogan large sports center, allowing them to make corresponding adjustments to the start-up and shutdown of heating and cooling source units based on event dates. Through dynamic adaptation, the day-by-day control strategy achieves optimal alignment between HVAC resources and demand, offering an efficient management approach for modern large-scale sports centers.

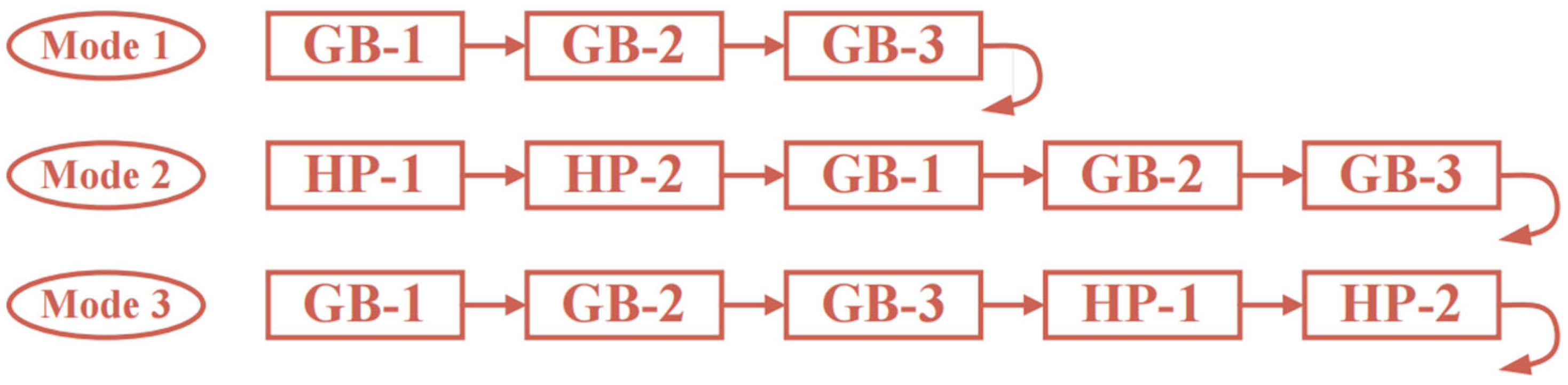

4.2. Heating Source System Unit

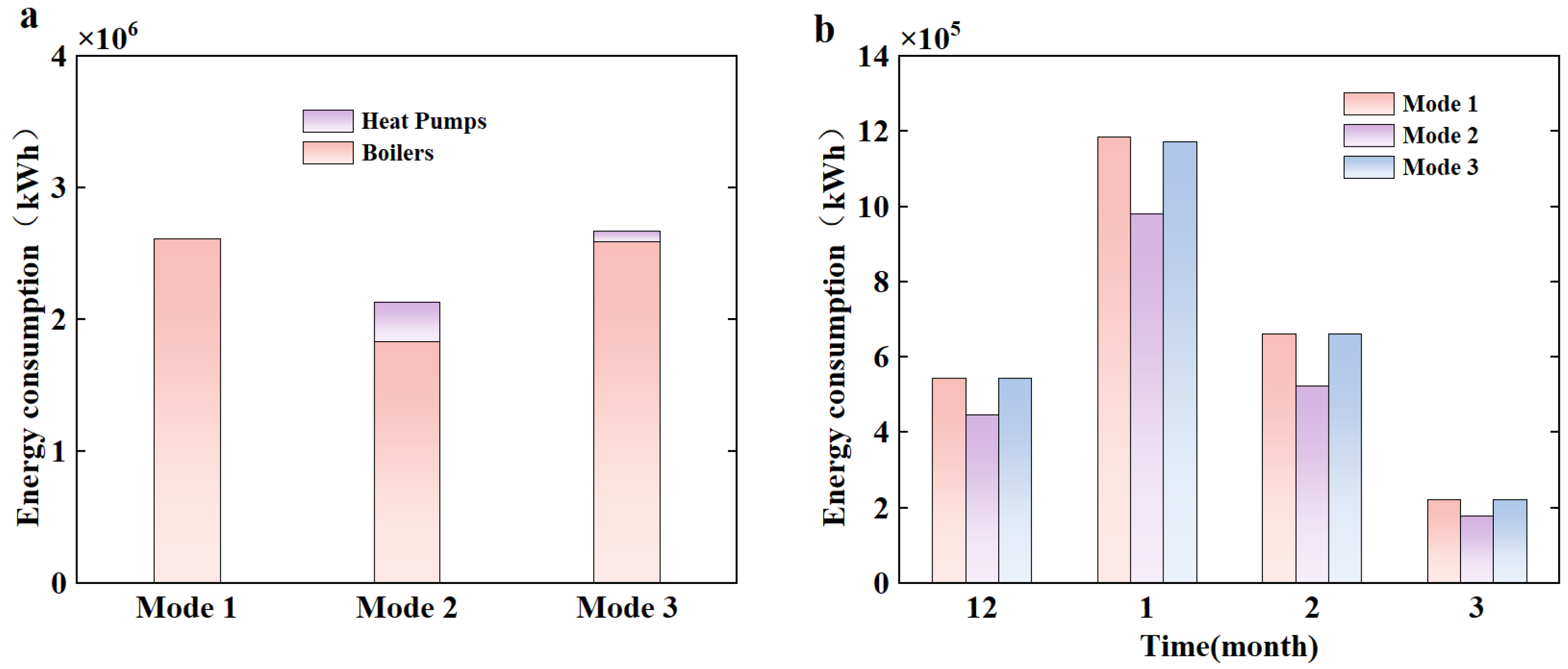

The results of system energy consumption of the heating system in different modes are shown in

Figure 10. Mode 1, which relies solely on gas boilers, exhibits the highest total energy use at 2,612,813.21 kWh. Mode 2 integrates both gas boilers and air-source heat pumps. It achieves the lowest total energy consumption of 2,127,935.94 kWh, including 1,833,401.84 kWh from gas boilers and 294,434.10 kWh from heat pumps. Mode 3, where gas boilers are prioritized and heat pumps serve as supplementary units, results in 2,599,849.45 kWh total consumption, with 2,593,499.05 kWh from boilers and only 6350.40 kWh from heat pumps. Mode 2 demonstrates the most energy-efficient performance, achieving savings of approximately 484,877.27 kWh compared to Mode 1 and 47,191,351 kWh compared to Mode 3. This confirms the effectiveness of employing heat pumps as base-load units to reduce overall system energy use.

Further analysis of monthly trends indicates that Mode 2 consistently outperforms Modes 1 and 3 throughout the entire heating season. This reinforces its potential as an optimal energy-saving control strategy in large-scale public buildings.

Based on regional utility pricing provided by State Grid Hubei Electric Power Company for commercial users and the official natural gas tariff for non-residential pipeline users in Hubei Province, the operational cost results for the heating system under three control modes are summarized in

Figure 11. Mode 1, which relies solely on gas boilers, yields a total operating cost of CNY ¥703,924.69. Mode 2, which utilizes air-source heat pumps as base-load units and gas boilers for peak-load support, achieves the lowest total cost of CNY ¥672,339.10, consisting of CNY ¥493,941.48 for gas and CNY ¥178,397.62 for electricity. Mode 3, prioritizing gas boilers with limited heat pump use, results in the highest cost at CNY ¥70,235.14, with CNY ¥702,354.14 for gas and only CNY ¥3632.93 for electricity. From an economic standpoint, Mode 2 demonstrates superior cost-efficiency, with a CNY ¥31,585.59 reduction compared to Mode 1 and a CNY ¥30,015.04 savings relative to Mode 3. This validates the benefit of allocating base-load heating to high-efficiency electric heat pumps, supported by lower-cost electricity during off-peak periods. Monthly analysis further confirms that Mode 2 maintains lower operating costs throughout the entire heating season, offering consistent economic advantages over the other two strategies.

In conclusion, Mode 2 presents both higher energy-saving potential and better economic performance, making it a compelling option for heating control optimization in large-scale public facilities. During the air conditioning season, it can save energy by 4.72%. The specific start–stop control logic for Mode 2 is summarized in

Table 10.

For the heating season (Mode 2): the energy savings (18.6%) primarily stem from optimized energy grade utilization. Specifically, high-efficiency electrically driven heat pumps (COP~3.4) are prioritized for base load coverage, while primary energy (natural gas)-driven boilers (efficiency < 1.0) are reserved solely for peak shaving. This fundamentally shifts heating loads from inefficient energy conversion methods to more efficient ones, thereby reducing primary energy consumption at the system level.

Under the Mode 2 control strategy, simulation analysis was conducted to assess hourly operational intervals of the heating system at the Xiaogan Olympic Sports Center during the winter season. The results are summarized in

Figure 12.

In December, the system operated two air-source heat pump units in combination with one 1050 kW and one 2100 kW gas boiler for a total of 233 h. Peak operation hours were observed throughout the entire day. Therefore, in December, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1 and GB-2 will be started from 8:00 to 20:00.

In January, full-load operation occurred under Interval 5—which includes two heat pumps, one 1050 kW boiler, and two 2100 kW boilers—for 170 h, with hourly peaks between 08:00 and 11:00. Additionally, the system operated under Interval 4 for 216 h, with peak hourly load between 11:00 and 20:00. Therefore, in January, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1, GB-2 and GB-3 will be started from 8:00 to 11:00, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1 and GB-2 will be started from 11:00 to 20:00.

In February, the same configuration as Interval 4 was active for 228 h, again with continuous operation throughout the day. Therefore, in February, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1 and GB-2 will be started from 8:00 to 20:00.

In March, the system operated under Interval 4 for 132 h, with peak hours concentrated in 08:00–10:00, 11:00–17:00, and 19:00–20:00. Additionally, Interval 3 operation—comprising two heat pumps and one 1050 kW gas boiler—occurred for 89 h, peaking from 10:00 to 11:00 and 17:00 to 19:00. Therefore, in March, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1 and GB-2 will be started from 8:00 to 10:00, Units HP-1,HP-2 and GB-1 will be started from 10:00 to 11:00, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1 and GB-2 will be started from 11:00 to 17:00, Units HP-1, HP-2 and GB-1 will be started from 17:00 to 19:00, Units HP-1, HP-2, GB-1 and GB-2 will be started from 19:00 to 20:00.

These results highlight the seasonal and hourly variability in heat load demand. The control strategy prioritizes heat pump operation for base loads and activates gas boilers in a cascading sequence to meet rising demand, thereby balancing energy efficiency with thermal reliability.