Investigating Damage Evolution of Concrete with Silica Fume Under Freeze–Thaw Conditions Using DIC Technology and Gray Model Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Value

2.1. The Novelty

2.2. Research Significance

3. Experimental Design

3.1. Material and Mix Design

3.2. Specimen Preparation and Experimental Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Apparent Morphology

4.2. Mass Loss

4.3. Modulus of Elasticity

4.4. Flexural Strength

4.5. Flexural Cracking Behavior

4.5.1. DIC Analysis

4.5.2. Crack Behavior Analysis

4.6. Microstructural Characterization of Concrete Modified with SF

4.6.1. Analysis of Hydration Products

4.6.2. Analysis of Air Content in Freshly Mixed Concrete and Pores in Hardened Concrete

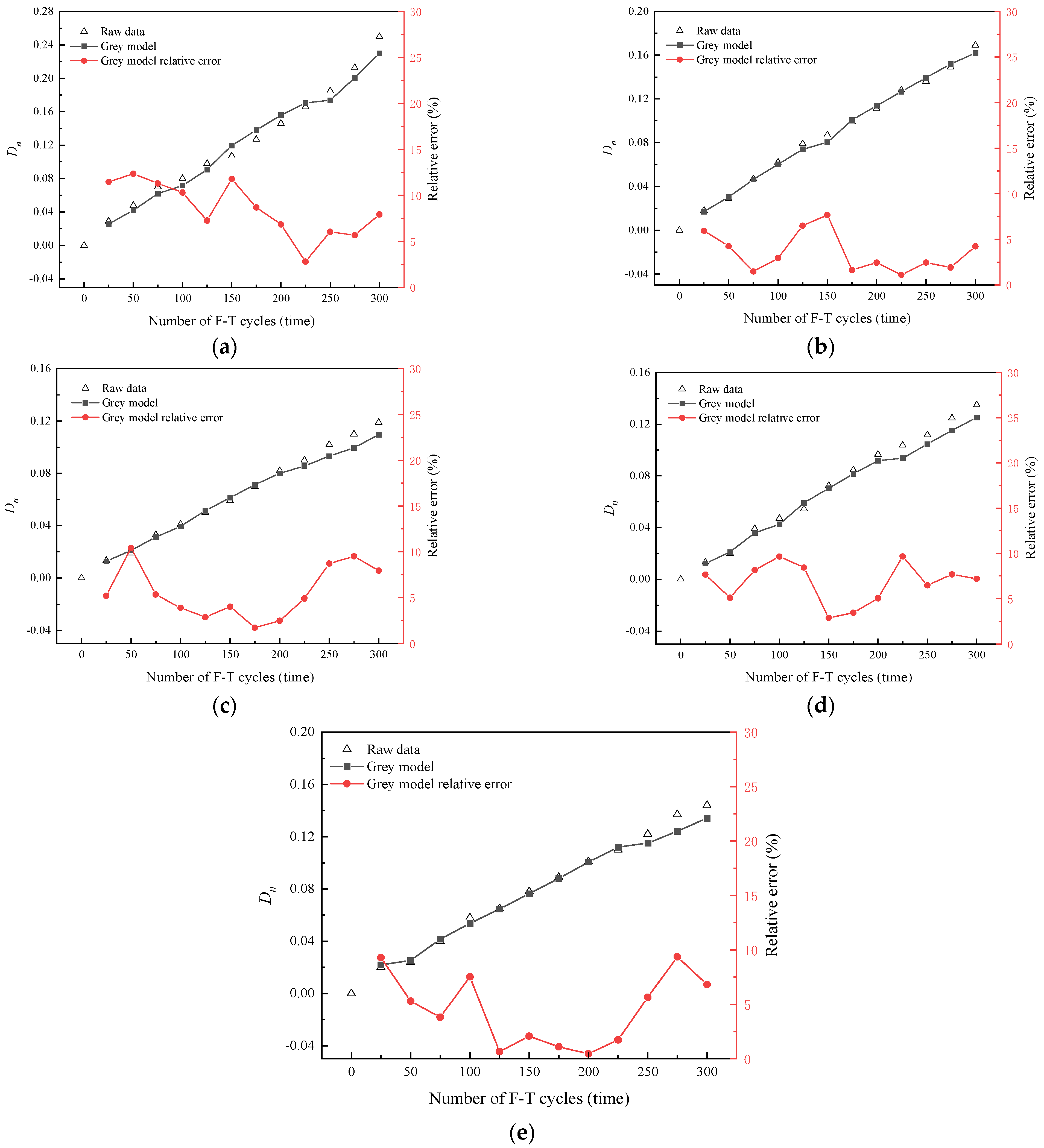

4.7. F-T Damage Model and Service Life Prediction

4.8. Accuracy Analysis of Prediction Models

5. Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The incorporation of SF can effectively improve the internal structure of concrete, enhance its relative dynamic elastic modulus and flexural strength, and reduce mass loss. Among them, the G10 specimen demonstrated the best performance. After 300 F-T cycles, the relative dynamic elastic modulus and flexural strength decreased by only 11.9% and 17%, respectively.

- (2)

- The flexural process of concrete exhibits four progressive mechanical stages: early stage, initiation stage, extension stage, and penetration stage. The addition of SF delayed the crack propagation rate and reduced the crack width. After 300 F-T cycles, the maximum crack width of G10 was reduced by 61% compared to G0, and the crack propagation rate decreased by 24.7%.

- (3)

- Microscopic experiments indicate that F-T cycles cause the expansion and interconnection of gel pores and transition pores in concrete, increasing the proportion of harmful pores. The incorporation of SF promotes cement hydration, generating a large amount of C-S-H gel that fills the pores, thereby improving the compactness of the matrix and effectively resisting F-T damage.

- (4)

- The accuracy of the gray system-based life prediction model meets Grade I standards, effectively characterizing the F-T damage of concrete. Under simulated severe cold climate conditions in Northeast China, the F-T resistance life of concrete with different SF contents follows the order of G10 > G20 > G30 > G5 > G0, with the predicted service life of G10 reaching 121.5 years.

5.2. Prospects

- (1)

- Using concrete mixed with SF in cold regions and strictly controlling the SF dosage to ensure performance can reduce carbon emissions and save costs. The gray system theory-based life prediction extends service cycles and reduces lifecycle costs.

- (2)

- In the future, we will study the synergistic effect of SF with fly ash or slag as well as analyze and explore the modification mechanism of other sustainable materials such as glass powder or industrial waste on the durability performance of concrete.

- (3)

- Future research will assess the long-term performance of G10 and G20 under combined salt and F-T exposure, with a focus on quantifying the effectiveness of their densified microstructure against salt crystallization and chemical degradation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lei, D.; Yu, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Jia, H.; Wu, Z.; Bao, J.; Liu, J.; Xi, X.; Su, L. A state-of-the-art on electromagnetic and mechanical properties of electromagnetic waves absorbing cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 157, 105889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, C. Properties of road subbase materials manufactured with geopolymer solidified waste drilling mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 430, 136509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tang, G.; Lu, X.; Xiong, B.; Guan, B.; Tian, B. Thermal property evolution and prediction model of early-age low-heat cement concrete under different curing temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; An, X.; Qi, B.; Shen, D.; Lv, M. Effects of fly ash and limestone powder on the paste rheological thresholds of self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 281, 122560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, B.; Jiang, C.; Wu, L. Study on the damage mechanism of hydraulic concrete under the alternating action of F-T and abrasion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 137976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; You, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Macro-micro degradation process of fly ash concrete under alternation of F-T cycles subjected to sulfate and carbonation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 181, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Fan, S.; Xiao, S.; Huo, J.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Z. Flexural performance and damage of reinforced fly ash and slag-based geopolymer concrete after coupling effect of F-T cycles and sustained loading. Structures 2024, 64, 106537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, C. Unary, binary and ternary use of slag, nano-CaCO3, and cement to enhance F-T durability in fly ash-based geopolymer concretes. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyunbileg, D.; Amgalan, J.; Batbaatar, T.; Temuujin, J. Evaluation of thermal and F-T resistances of the concretes with the SF addition at different water-cement ratio. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02633. [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar, O.Y.; Eshtewı, S.S.T.; Benli, A.; Kaplan, G.; Toklu, K.; Gunek, F. The impact of RCA and fly ash on the mechanical and durability properties of polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete exposed to F-T cycles and MgSO4 with ANN modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 313, 125508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Mao, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Q. Influence of stress damage and high temperature on the freeze–thaw resistance of concrete with fly ash as fine aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yu, H.; Li, C.; Tan, Y.; Cao, W.; Da, B. Freeze–thaw damage to high-performance concrete with synthetic fibre and fly ash due to ethylene glycol deicer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaeipour, A.; Madhkhan, M. Effect of ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) on RCCP durability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 141, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Liu, W.; Ashour, A.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Jiang, H.; Sun, C.; Qiu, L.; Yao, S.; Lu, W.; et al. Sustainable ultra-high performance concrete with incorporating mineral admixtures: Workability, mechanical property and durability under F-T cycles. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wen, T.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Ma, Z.J. F-T resistance of Class F fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Quy, N.X.; Noguchi, T.; Kim, J.; Hama, Y. A study on the change in frost resistance and pore structure of concrete containing blast furnace slag under the carbonation conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 331, 127295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, D.; Akbulut, Z.F.; Guler, S. Porous concrete modification with SF and ground granulated blast furnace slag: Hydraulic and mechanical properties before and after F-T exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 138099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Xiao, J.H. Upcycling waste glass bottles as a binder within engineered cementitious composites (ECCs): Experimental investigation and environmental impact assessment. Clean. Mater. 2025, 16, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.M.; Coutinho, J.S. Durability of mortar using waste glass powder as cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Gu, Q.; Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, S.; Ruan, Z.; Huang, J. Effect of basalt fibers and SF on the mechanical properties, stress-strain behavior, and durability of alkali-activated slag-fly ash concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, M. Improvement in concrete behavior with fly ash, silica-fume and coconut fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasanipour, H.; Aslani, F.; Taherinezhad, J. Effect of SF on durability of self-compacting concrete made with waste recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizan, M.H.; Ueda, T.; Matsumoto, K. Enhancement of the concrete-PCM interfacial bonding strength using SF. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencel, O.; Nodehi, M.; Bayraktar, O.Y.; Kaplan, G.; Benli, A.; Gholampour, A.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Basalt fiber-reinforced foam concrete containing SF: An experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradar, A.; Nemati, P.; Paskiabi, A.S.; Moein, M.M.; Moez, H.; Vishki, E.H. Prediction of mechanical properties of lightweight basalt fiber reinforced concrete containing SF and fly ash: Experimental and numerical assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, L.; Duan, Y.; Tang, Z.; Hu, F.; Chen, Z. High-flowable and high-performance steel fiber reinforced concrete adapted by fly ash and SF. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02796. [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanzadeh, I.; Ramezanianpour, A.M.; Amani, A.; Habibi, A. Mixture optimization of alkali activated slag concrete containing recycled concrete aggregates and SF using response surface method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 135928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Cheng, H.; Que, Z.; Liu, T.; Zou, D. Enhancing marine anti-washout concrete: Optimal SF usage for improved compressive strength and abrasion resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, A.S.; Abro, F.-U.-R.; Ali, M.; Ali, T.; Bheel, N. Effect of SF on fracture analysis, durability performance and embodied carbon of fiber-reinforced self-healed concrete. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 130, 104333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoonmehr, R.; Rahai, A.; Ramezanianpour, A.A. Predicting the chloride diffusion coefficient and surface electrical resistivity of concrete using statistical regression-based models and its application in chloride-induced corrosion service life prediction of RC structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 357, 129351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taffese, W.Z.; Espinosa-Leal, L. Prediction of chloride resistance level of concrete using machine learning for durability and service life assessment of building structures. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 60, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, J. Numerical prediction for life of damaged concrete under the action of fatigue loads. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 162, 108368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Chen, D.; Yang, F.; Mei, J.; Yao, Y. Freeze–thaw damage analysis and life prediction of modified pervious concrete based on Weibull distribution. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Xue, H.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wei, L. Study on damage deterioration mechanism and service life prediction of hybrid fibre concrete under different salt freezing conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 435, 136688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhang, M.; Zou, D.; Liu, T. A failure thickness prediction model for concrete exposed to external sulfate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudi, L.; Krishnan, S.; Bishnoi, S. Numerical modeling for predicting service life of reinforced concrete structures exposed to chloride. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpay, S.; Hu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Shumuye, E.D.; Wendner, R.W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Ueda, T. The influence of testing conditions on damage zone of concrete in Uniaxial Compression: Insights from Stereo-DIC and computational modelling. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhai, Y.; Wei, S. Research on compressive failure and damage mechanism of concrete-granite composites with different roughness coefficient by NMR and DIC techniques. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 170, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Leung, C.K.Y. A fundamental method for prediction of failure of strain hardening cementitious composites without prior information. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DL/T 5150-2017; Test Code for Hydraulic Concrete. Electric Power Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 50082—2024; Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- Shi, H.; Wang, H.; Xue, S.; Feng, S.; Li, Y. Durability evaluation of iron tailings concrete under F-T cycles and sulfate erosion based on entropy weighting method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 443, 137747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, R.; Guan, X.; Cheng, K.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Z. Deterioration characteristics of coal gangue concrete under the combined action of cyclic loading and F-T cycles. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 60, 105165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttala, V.; Al Neshawy, F. Stress and strain state of concrete during freezing and thawing cycles. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhou, J.; Yin, Z. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties and Pore Structure Deterioration of Concrete under Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Materials 2021, 14, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; He, Z.; Cai, X. Application of Low-Field NMR to the Pore Structure of Concrete. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2021, 52, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Zhao, X.; Zou, B.; Chen, C. Topographical characterization and permeability correlation of steel fiber reinforced concrete surface under F-T cycles and NaCl solution immersion. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Wan, X.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, P. Experimental investigation on the mechanical properties and pore structure deterioration of fiber-reinforced concrete in different F-T media. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 350, 128887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, J.; Liu, K.; Sun, S. Study on the durability deterioration law of marine concrete with nano-particles under the coupled effects of F-T cycles, flexural fatigue load and Cl-erosion. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, H.; Haruna, S.I.; Shao, J.; Yu, Y.; Wu, K. Mechanical properties and freeze–thaw resistance of polyurethane-based polymer mortar with crumb rubber powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 352, 129040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Liang, Y.; Shen, J.; Yang, H. Study on fracture characteristics and fracture mechanism of fully recycled aggregate concrete using AE and DIC techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, H.; Liu, D. Study on fracture characteristics of steel fiber reinforced manufactured sand concrete using DIC technique. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, P.; Yan, X.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X. Effect of SF on frost resistance and recyclability potential of recycled aggregate concrete under freeze–thaw environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 134109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.L. Analysis of Mix Proportions and Mechanical Properties of Mechanically Processed Sand Modified Concrete. J. Yichun Univ. 2025, 47, 41–44+63. [Google Scholar]

- Nima, H.; Prannoy, S. Synergistic effects of air content and supplementary cementitious materials in reducing damage caused by calcium oxychloride formation in concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, G.; Niu, J. Effect of recycled concrete powder-cement composite coating modification on the properties of recycled concrete aggregate and its concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 444, 137860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, X. Performance degradation mechanism and strength prediction of SF concrete under sulfate dry–wet cycles. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05163. [Google Scholar]

- Smarzewski, P. Mechanical and Microstructural Studies of High-Performance Concrete with Condensed Silica Fume. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Muntean, R. The Effectiveness of Different Additives on Concrete’s Freeze–Thaw Durability: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Li, W.G. Uniaxial compressive behaviors of fly ash/slag-based geopolymeric concrete with recycled aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Yu, H.F.; Wu, C.Y. Research on the constitutive relationship of concrete under uniaxial compression in freeze–thaw environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 336, 127543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Li, Z.Y.; Li, Y.L.; Hao, J.P.L.; Pan, Y.K. Grey relational analysis of pore structure-mechanical property relationships in concrete under low-temperature and low-humidity curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.H.; Dong, W. Grey correlation analysis of macro- and micro-scale properties of aeolian sand concrete under the salt freezing effect. Structures 2023, 58, 105551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Guan, K.; Kou, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X. Durability evaluation and life prediction of fiber concrete with fly ash based on entropy weight method and grey theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhang, J. Spatial degradation characteristics and numerical prediction for life of MWCNTs-reinforced concrete by salt freezing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B. Frost resistance and life prediction of equal strength concrete under negative temperature curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 396, 132278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Lu, J.X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Sun, J.P.; Yang, G. A β-VAE-stacking ensemble prediction model for fatigue life of reinforced concrete beams. Structures 2025, 79, 109616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Components | Al2O3 | SiO2 | SO3 | Cl | TiO2 | Fe2O3 | Na2O | K2O | MgO | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (%) | 4.16 | 20.42 | 2.75 | 0.028 | 0.341 | 2.83 | 0.7 | 0.46 | 1.6 | 60.74 |

| Chemical Components | Al2O3 | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Na2O | MgO | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (%) | 1.28 | 91.8 | 2.83 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.35 |

| Water | Water–Cement Ratio | Coarse Aggregate | Fine Aggregate | Sand | Water-Reducing Agent | Air-Entraining Agents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 164.66 | 0.36 | 688.82 | 688.82 | 982.42 | 1.85 | 0.23 |

| Group Name | G0 | G5 | G10 | G20 | G30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF content (%) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| Dynamic Elastic Modulus/GPa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of F-T Cycles | G0 | G5 | G10 | G20 | G30 |

| 0 | 36.36 | 38.08 | 42.01 | 40.35 | 39.72 |

| 25 | 35.35 | 37.50 | 41.60 | 39.94 | 39.04 |

| 50 | 34.67 | 37.10 | 41.49 | 39.73 | 38.91 |

| 75 | 33.84 | 36.39 | 40.80 | 38.89 | 38.18 |

| 100 | 33.35 | 35.66 | 40.34 | 38.41 | 37.37 |

| 125 | 32.65 | 34.86 | 39.86 | 38.06 | 37.01 |

| 150 | 32.23 | 34.53 | 39.45 | 37.25 | 36.37 |

| 175 | 31.37 | 33.96 | 38.93 | 36.66 | 35.92 |

| 200 | 30.53 | 33.36 | 38.36 | 36.03 | 35.33 |

| 225 | 29.54 | 32.67 | 37.89 | 35.71 | 34.82 |

| 250 | 28.68 | 32.06 | 37.30 | 35.19 | 34.10 |

| 275 | 27.39 | 31.36 | 36.65 | 34.39 | 33.30 |

| 300 | 25.67 | 30.22 | 35.96 | 33.61 | 32.58 |

| Group Name | C-S-H (%) | Ca(OH)2 (%) | Total Loss of Water (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G0 | 9.53 | 7.37 | 20.20 |

| G5 | 9.20 | 5.00 | 13.15 |

| G10 | 12.48 | 3.70 | 15.13 |

| G20 | 9.37 | 3.75 | 15.75 |

| G30 | 7.16 | 4.71 | 20.88 |

| Group Name | Verification Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| C | P | |

| G0 | 0.1594 | 1 |

| G5 | 0.0893 | 1 |

| G10 | 0.0821 | 1 |

| G20 | 0.0939 | 1 |

| G30 | 0.089 | 1 |

| Group Name | G0 | G5 | G10 | G20 | G30 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor F-T cycle times | 604 | 862 | 1215 | 1046 | 997 | ||

| Prediction | Northeast China/year | 60.4 | 86.2 | 121.5 | 104.6 | 99.7 | |

| North China/year | 86.3 | 123.1 | 173.6 | 149.4 | 142.4 | ||

| Northwest China/year | 61.4 | 87.7 | 123.6 | 106.4 | 101.4 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, W.; Dou, T.; Xia, S.; Li, M. Investigating Damage Evolution of Concrete with Silica Fume Under Freeze–Thaw Conditions Using DIC Technology and Gray Model Approach. Buildings 2025, 15, 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224051

Niu W, Dou T, Xia S, Li M. Investigating Damage Evolution of Concrete with Silica Fume Under Freeze–Thaw Conditions Using DIC Technology and Gray Model Approach. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224051

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Wenlong, Tiesheng Dou, Shifa Xia, and Meng Li. 2025. "Investigating Damage Evolution of Concrete with Silica Fume Under Freeze–Thaw Conditions Using DIC Technology and Gray Model Approach" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224051

APA StyleNiu, W., Dou, T., Xia, S., & Li, M. (2025). Investigating Damage Evolution of Concrete with Silica Fume Under Freeze–Thaw Conditions Using DIC Technology and Gray Model Approach. Buildings, 15(22), 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224051