1. Introduction

Urban areas serve as economic and political centers, providing environments for social relations and cultural expression [

1]. As cities worldwide seek to make public spaces more resilient and adaptable, public events are becoming vital tools for shaping social structures [

2]. Therefore, careful planning of these events is essential to facilitate the recovery of urban public spaces and the creation of social bonds [

3].

Urban planners and policymakers have adopted various strategies to encourage socio-cultural sustainability. For instance, Barcelona’s La Mercè Festival demonstrates cultural power by activating urban spaces to foster an engaged community [

4]. Similarly, New York’s Summer Streets initiative transforms car-centric main streets into vibrant pedestrian zones for social interaction [

5]. In Copenhagen, urban planning suggests that public spaces and community events should interact in mutually supportive ways [

6]. For example, Superkilen Park was designed with input from local immigrants to function as both a daily recreation area and a venue for cultural events that celebrate the area’s diversity [

7]. This dual use demonstrates how well-planned public spaces can support routine activities and special events. Furthermore, Melbourne’s Federation Square hosts over 2000 events annually, from small community gatherings to large cultural festivals [

8]. Between 2015 and 2023, the number of festivals in the Netherlands increased by 45%, with a high concentration in urban areas [

9].

Despite these examples, researchers highlight the inherent contradictions between protecting urban spaces as a neighborhood resource and exploiting them for events [

10]. Even when private communities integrate public activities, a balance must be struck between promoting community involvement and improving residents’ quality of life, unlike dedicated event spaces in urban centers. For example, in Tokyo, the traditional Matsuri neighborhood celebrations effectively achieve this balance by enhancing community life while meeting residents’ demands [

11]. The success of these events depends on careful planning, community participation, and the intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge [

12].

Existing research widely indicates that public events have a significant impact on urban areas, transforming them into key destinations that stimulate emotion and promote relationships [

13,

14]. While neighborhood public spaces are potential locations for these events, they also present challenges related to space management and organization [

10,

11]. However, there is a limited understanding of the specific factors that contribute to the suitability of these spaces for hosting events. Hence, there is a need to explore the challenges of organizing events in residential neighborhoods, particularly in the Arabian context, which possesses unique socio-cultural characteristics. This study addresses this gap by recognizing the importance of local knowledge and cultural memory in creating public events. It aims to integrate historical elements from Riyadh’s traditional gatherings into the design of contemporary events, fostering cultural productivity and community engagement. The overall objective is to analyze the suitability of public events in residential neighborhoods by exploring the factors affecting their functionality and the motivations for residents’ participation.

This research supports the Saudi Quality of Life Program, a key component of Vision 2030, which aims to improve civic life through cultural participation and social interaction [

15]. The findings will provide theoretical and practical insights for organizing public events in residential communities, helping authorities in Riyadh create more vibrant and socially integrated neighborhoods in a changing climate and in accordance with local cultural values. Ultimately, this study offers valuable information for legislators, urban planners, and community organizers in Riyadh and other rapidly developing cities.

2. Literature Review

Public events are essential catalysts in shaping the social fabric and spatial dynamics of urban areas. They temporarily alter the use of public spaces, encouraging social interactions and providing opportunities for communities to connect, share values, and celebrate cultural diversity. Defined as temporary gatherings with a distinct start and end, events incorporate elements of management, planning, place, and people, offering unique recreational experiences [

16,

17]. Events enable residents to break away from routine, strengthen social cohesion, and foster a sense of belonging [

18]. They involve people gathering for a defined purpose with the aim of social, economic, cultural, and political gains [

19]. In urban development, public events facilitate shared prosperity and contribute to the community’s collective experience [

20]. Major events like the Olympics have demonstrated their capacity to drive local growth and enhance urban infrastructure [

21]. Planned urban events, often rooted in tradition, have long provided spaces for celebrating cultural and religious values [

22]. Such gatherings offer avenues for economic growth, social enhancement, and enrichment of urban spaces, which explains the growing interest in events as vital urban phenomena [

23,

24,

25]. In the case of Riyadh, the Saudi Vision 2030 serves as a key driver of change, explicitly prioritizing the creation of a vibrant society through cultural and entertainment events. This strategic shift is not merely reflective of global trends but represents a central pillar of national policy. It is actively reshaping the city’s urban landscape and opening new avenues for social engagement, positioning public events as instruments of cultural transformation and civic vitality.

Public events significantly influence urban spaces, transforming them into meaningful locations filled with experiences that induce emotions and encourage social interaction [

13,

14]. While they contribute positively to the vibrancy of urban environments, they can also present challenges with respect to space management and organization [

26]. By temporarily reshaping the functions of public spaces, events contribute to reimagining urban policies and guiding spatial planning, with temporary uses often leading to lasting impacts [

27]. The rhythmic nature of recurring public gatherings influences city governance and design decisions, creating short- and long-term effects on urban development [

28]. Public events also enable co-creation through community involvement, although concerns regarding commercialization and exclusivity remain [

29].

The positive impacts of public events on community well-being are also validated by several studies. A study of Winchester, UK, showed that residents feel that public events improve their quality of life while strengthening cultural identity and promoting local economic viability [

30]. Similarly, residents in South Africa responded positively to event planning, recognizing these gatherings as constructive elements for their social connections [

31,

32]. Studies from Southeast England confirmed this by showing how arts and cultural festivals generate communal bonding experiences that diminish social isolation [

33]. Overall, public events significantly help cities and communities by promoting social interaction, activating urban spaces, and strengthening local identities [

34]. These insights are particularly relevant to Riyadh’s evolving social landscape. As a rapidly growing and increasingly diverse city, Riyadh faces the challenge of bridging traditional and modern lifestyles. Public events offer a strategic tool for fostering social cohesion and shared experiences. Initiatives such as Riyadh Season exemplify this approach, attracting millions of participants and contributing to the formation of a new collective urban memory.

Past studies have examined the interaction between physical environments and emotional connections to place, shifting the focus from static elements to dynamic experiential qualities in urban design. These studies often prioritized the physical structure of space; however, current trends suggest a need to understand how emotional and cultural factors interact with the built environment. Studies have found that people’s emotional connections to a place influence their attachment and overall quality of life [

35,

36,

37]. For example, research on the Parasol Gallery project in Chiba, Japan, found that it improved place attachment, promoted social interaction, and built community pride by engaging artists, visitors, and residents. This case underscores how public events can strengthen social cohesion and positively reshape urban social dynamics [

13]. The Tokyo 2020 Olympics is an example of how mega-events can facilitate a human-centered approach to city planning. Through local festivals, cultural programs, and community projects, municipal governments actively constructed the identity of the city, enhancing social integration and cultural expression [

38,

39]. These events played a crucial role in creating an integrated cityscape through participatory community engagement and the strengthening of social bonds. On the other hand, community-driven events help transform public areas by involving residents in planning decisions and ensuring equitable benefits for the community [

38]. Developing meaningful spaces requires active cooperation between planners and community members to create areas that showcase both neighborhood identity and shared social goals [

39]. By actively bringing people together and honoring cultural heritage, these multicultural celebrations provide metropolitan areas with their unique identity. A study in Aqaba City confirmed that public events create inclusive urban development when residents are aware, actively participate, and have positive attitudes toward them [

14]. Similarly, administrators demonstrated how large athletic events can generate economic success and community pride through investments and urban development planning, as seen during Cape Town’s 2004 Olympic bid campaign [

39]. These global examples offer valuable insights for Riyadh as it seeks to create more engaging public spaces. Given the city’s traditionally private social structure, public events and festivals serve as effective tools for encouraging civic interaction in culturally appropriate ways. Riyadh’s growing investment in parks and entertainment zones reflects a recognition of the importance of “third places” informal gathering spaces beyond home and work that foster social connectivity and urban vitality.

While numerous studies have highlighted the positive impacts of events such as enhancing social cohesion, promoting local identity, and revitalizing urban areas [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] the literature often treats these benefits descriptively, without critically examining the specific conditions under which these outcomes are realized. For instance, while mega-events like the Olympics have shown potential for infrastructural development [

21], they also risk marginalizing local communities. A growing body of research emphasizes the experiential and emotional dimensions of urban space, shifting focus from static physical structures to dynamic, people-centered environments. Concepts such as place attachment and third place theory offer valuable insights into how residents emotionally connect with their surroundings and how informal, inclusive spaces support community life [

35,

36,

37]. These perspectives are particularly relevant when assessing the suitability of residential neighborhoods for public events, where emotional resonance and social trust are essential.

Moreover, human-centered urbanism promotes participatory planning and inclusive design, aligning with studies that highlight the importance of community-driven events in fostering equitable urban development [

38]. Events that emerge organically from within communities rather than being externally imposed are more likely to reflect local values, ensure equitable access, and reinforce neighborhood identity. This critical perspective is especially pertinent to Riyadh, where urban planning has traditionally followed a top-down approach. As the city embarks on major developments such as King Salman Park, the challenge lies in balancing large-scale, state-sponsored initiatives with grassroots, community-led events that authentically represent Riyadh’s diverse neighborhoods and cultural heritage. Embracing this dual approach can help ensure that public events serve not only as instruments of urban transformation but also as platforms for inclusive civic engagement.

The transformation of residential neighborhoods into viable venues for public events reflects a growing trend in urban planning that emphasizes flexibility, inclusivity, and community engagement. Research underscores the importance of public spaces particularly parks and open areas as catalysts for social cohesion and cultural expression. A systematic review by Qi et al. (2024) [

14] highlights that accessible, well-designed public spaces with amenities such as seating, restrooms, and mixed-use infrastructure significantly enhance social interaction and community bonding. To support this transformation, urban planners must adopt modular and adaptive design strategies. Modular architecture, as explored by Urban Design Lab (2024) [

40], enables spaces to be reconfigured for various functions, from daily recreation to large-scale events. Features such as movable partitions, plug-and-play utilities, and flexible furniture systems allow for rapid adaptation without compromising long-term sustainability.

Equally important are zoning regulations, which play a critical role in enabling temporary events in residential areas. A comprehensive guide to California’s zoning laws reveals that while residential zones often impose restrictions on noise, traffic, and occupancy, updated ordinances can facilitate community events by balancing public interest with neighborhood integrity [

41]. Simplifying permitting processes and establishing clear guidelines for safety and accessibility are essential to encourage grassroots initiatives and cultural programming. Placemaking strategies further reinforce the value of integrating arts and cultural activities into neighborhood planning. Loh et al. (2022) [

42] emphasize that creative placemaking fosters vibrant, inclusive communities by embedding cultural identity into the built environment. Equally vital is the role of participatory planning. Engaging residents in the design and programming of event spaces ensures that developments align with community needs and values. As Mendhe (2024) [

43] argues, bottom-up planning approaches empower residents, foster ownership, and lead to more sustainable urban outcomes. The suitability of residential neighborhoods for hosting events hinges on a holistic integration of flexible design, regulatory reform, and community participation. By retrofitting public spaces with modular infrastructure, updating zoning laws, and involving residents in planning, municipalities can create dynamic environments that support both everyday life and vibrant public events. For Riyadh, these principles translate into specific actions. The city’s burgeoning park network, including neighborhood parks, offers an ideal canvas for adopting modular design and flexible infrastructure. Moreover, developing a framework for streamlined permitting processes for community events would empower local residents and small businesses. This is especially important in Riyadh, where the success of a community event is measured not only by its economic impact but also by its ability to respect local customs and social norms while creating a sense of shared community.

Despite these insights, a significant gap remains in understanding the specific criteria that determine the suitability of residential neighborhoods for hosting public events, especially in culturally diverse and rapidly urbanizing contexts like Riyadh. Existing research tends to focus on either the benefits of events or their impacts on public spaces, with limited attention to the interplay between spatial characteristics, demographic profiles, and resident perceptions. Furthermore, the literature lacks a comprehensive framework that integrates spatial analysis, socio-demographic data, and community feedback to assess event-hosting potential at the neighborhood level. This is particularly important in cities where urban expansion and cultural sensitivities intersect, creating unique challenges and opportunities for event planning. This study addresses these gaps by proposing a multidimensional approach to evaluating neighborhood suitability for public events in Riyadh. By combining spatial metrics with perceptual data, it contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how events can be integrated into residential areas in ways that are socially inclusive, spatially appropriate, and culturally resonant.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Basic Information

The survey results have multiple sections that present complete information on demographic attributes. The information shows that women represent 72% of the total population, while men make up 23%. The population analysis shows that the 18–30 age category represents 72% of the total of respondents. The results show that 15% of the participants belong to the 31–45 age bracket, while 6% are under 18 years of age and 4.2% fall within the 46–60 age range. Employment in the private sector stands at 19% whereas the government sector and semi-governmental sector each contribute 12% and 7%, respectively.

The demographic profile of the sample was 72% female, and a predominance of younger respondents reflects common patterns in online survey participation. Maslovskaya and Lugtig [

46] note that online surveys often overrepresent younger and more educated individuals due to their higher digital engagement. While this limits statistical representativeness, it does not invalidate the findings, particularly in exploratory studies where the aim is to capture diverse and engaged viewpoints. Moreover, these demographic groups are often among the most active in community life and digital communication, making their perspectives especially relevant to the topic of public event planning.

The data displays information in a straightforward format through distinct columns dedicated to each demographic category which enables further analysis. The research design successfully integrates the variables of age with gender and work status to provide valuable information on the demographic profile of the investigated participants. The analyzed population exhibits a youthful character with female dominance and shows a broad employment distribution across various fields, especially in private sector workplaces.

4.2. Appropriateness of Holding Events in Neighborhood

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

The sampled respondents were asked different questions on the suitability of conducting public events in residential neighborhoods. Descriptive statistics suggest that the 18–30 age group appears to be the most frequent attendees of public events. The analysis further reveals that most participants understand the value of neighborhood events, as they suggest a higher frequency of such events to happen in the future. Hence, a wide range of citizen support for events becomes apparent through this data because people show different levels of event enthusiasm and significance placement.

According to the survey respondents, public parks in neighborhoods rank as the most suitable event locations. Moreover, they believe 1000 sqm to 5000 sqm is the most appropriate space on a main street with width from 20 to 30 m as the appropriate space and location for holding events. It is also pertinent to note that the respondents suggest events of medium capacity (501–1000 people) that can help create the best balance between community involvement and available urban space. Thus, the respondents prefer community gathering locations that offer integration, eco-friendly features, and easy access. It can be said that parks and open spaces are effective venues and that public events significantly enhance community connections.

Public events serve as evidence supporting the research claim that such events humanize urban environments through expanded social engagement and cultural manifestation. It is essential to note that the majority of respondents preferred smaller community events. However, they prefer cultural and entertainment-based events as their preferred event type, showing their interest in leisure activities and artistic expression. Therefore, urban planners must make efficient crowd management and security measures their priority because traffic congestion along with safety concerns represent the obstacles faced most frequently in the organization of public events. Event planning strategies require development using mode values that correspond to public preferences.

Most of the respondents agree on the need to improve the facilities in such venues. The convenience of event locations depends on the presence of essential facilities such as seating areas and restroom facilities along with waste management systems. Similarly, they suggested the availability of a mosque for men and women near the event site. In addition, the respondents highlighted the weather conditions as influential in organizing the events. On the contrary, the respondents revealed that the current infrastructure facilities in the neighborhood venues are insufficient to organize events, which indicates a widespread dissatisfaction with the current infrastructure. Therefore, there is a need to focus on providing essential infrastructure to effectively conduct public events in residential neighborhoods.

When asked about the appropriate means of transportation to reach potential event venues in residential areas, the respondents preferred public transportation, bicycles, and scooters as their preferred modes of mobility. It suggests the need for a contemporary urban planning methodology that can facilitate the alleviation of traffic congestion while advancing sustainable transportation alternatives.

4.2.2. Correlation Analysis

Correlation analyses were performed to further reveal information on how public events can be conducted within residential neighborhoods. The correlation data reveal the different elements that affect how effectively and appropriately public events function within Riyadh’s urban neighborhoods. The analysis demonstrates how population statistics combine with environmental variables while event particularities determine community participation together with event perception levels. Understanding these factors is essential to the successful creation of event strategies so that municipal authorities can design programs that promote neighborhood inclusion, cultural events, and social bonds.

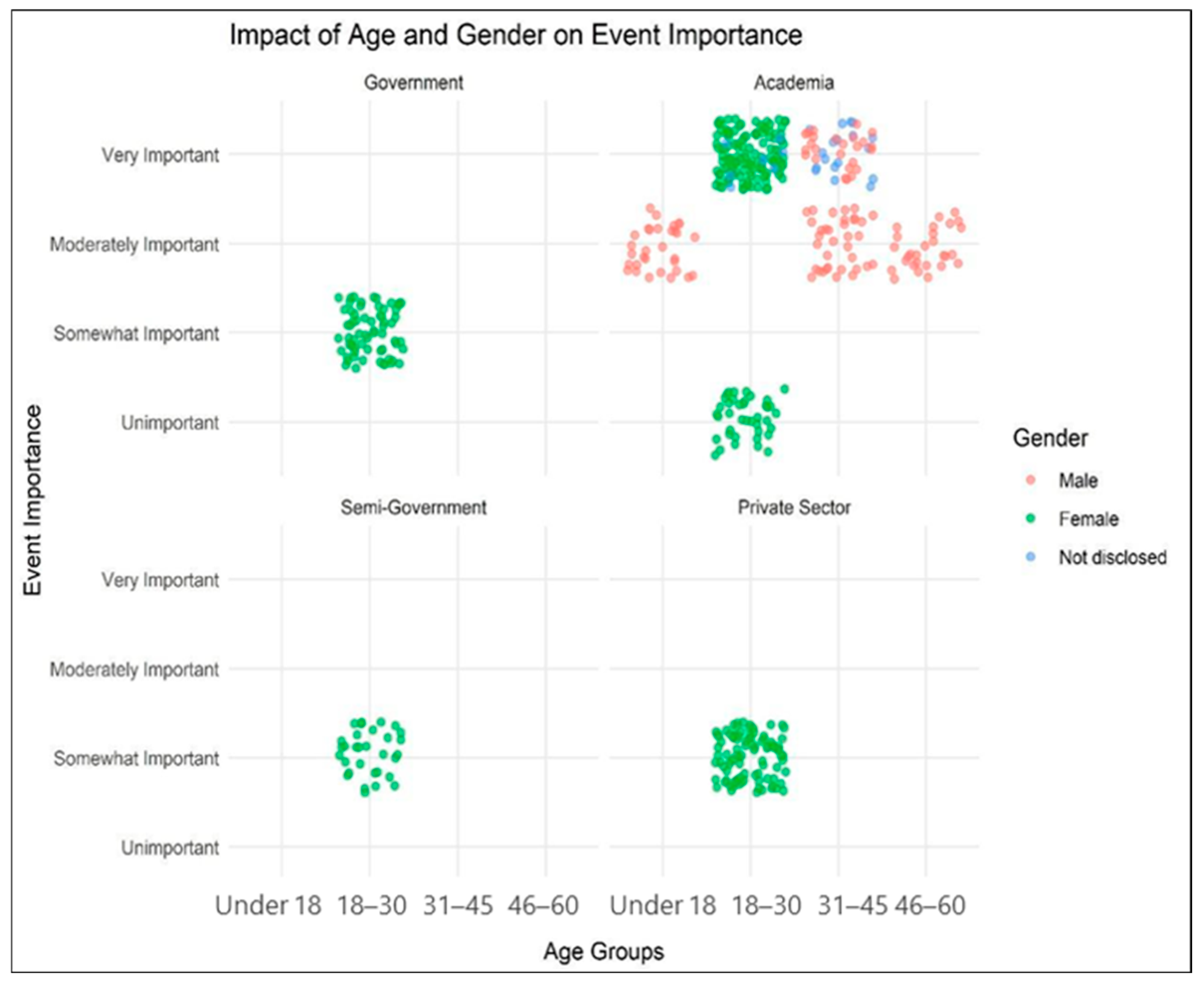

The characteristics of demographics strongly influence how city residents perceive public events together with their level of involvement. Preferences for public events strongly depend on three essential demographic variables that include age, gender, and professional work experience. Youth within the age range of 18 to 30 years show interest mostly in entertainment and cultural events, but adults ranging from 46 to 60 years choose religious and community-focused gatherings (

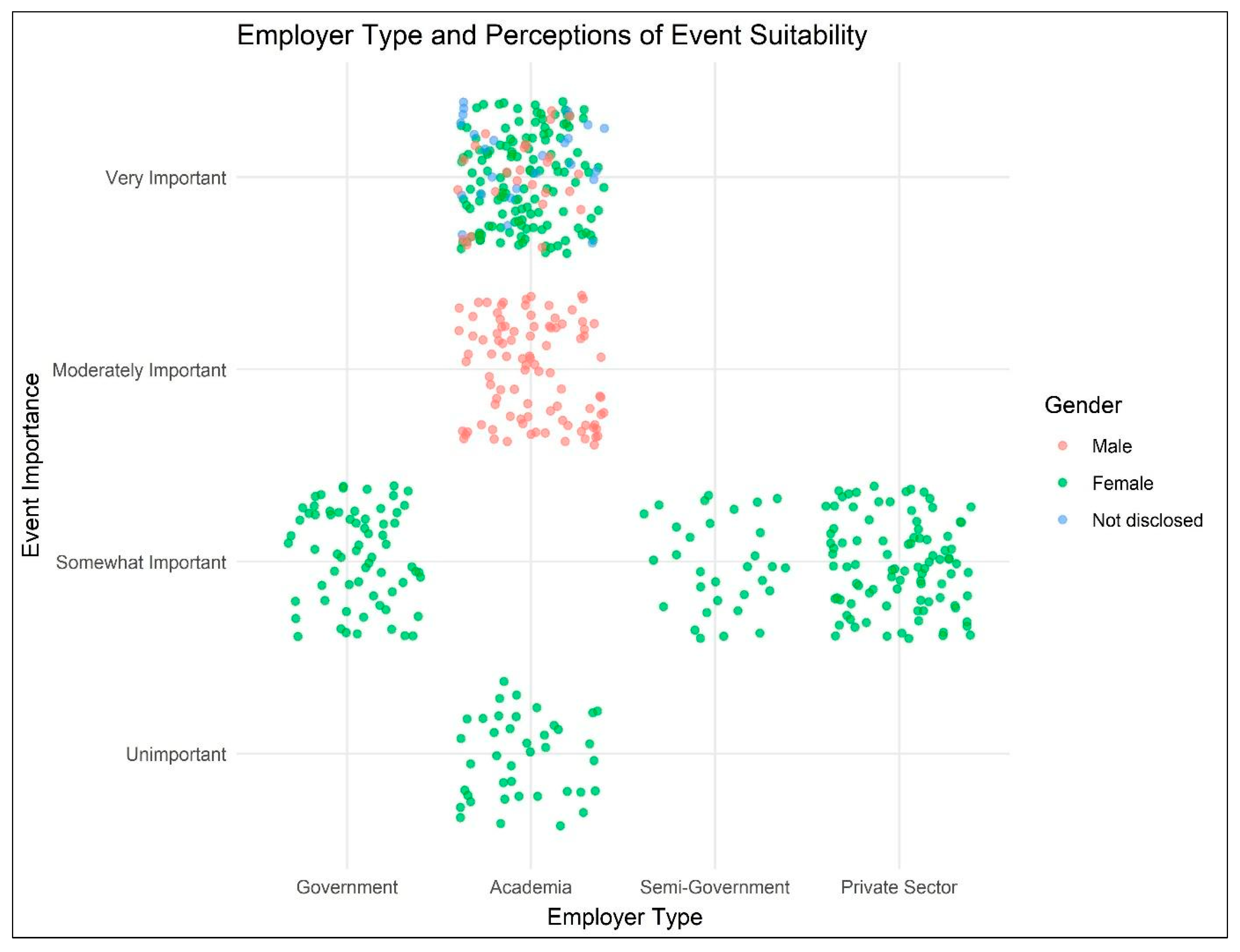

Figure 2). Participants make their event selections using a gender-biased approach that shows distinct behavioral patterns between male and female attendees. The employment sector where people work either in government or private sectors or academia determines what types of experiences employees desire from events. The analysis demonstrates why planners must plan events specifically for various audience preferences within the community.

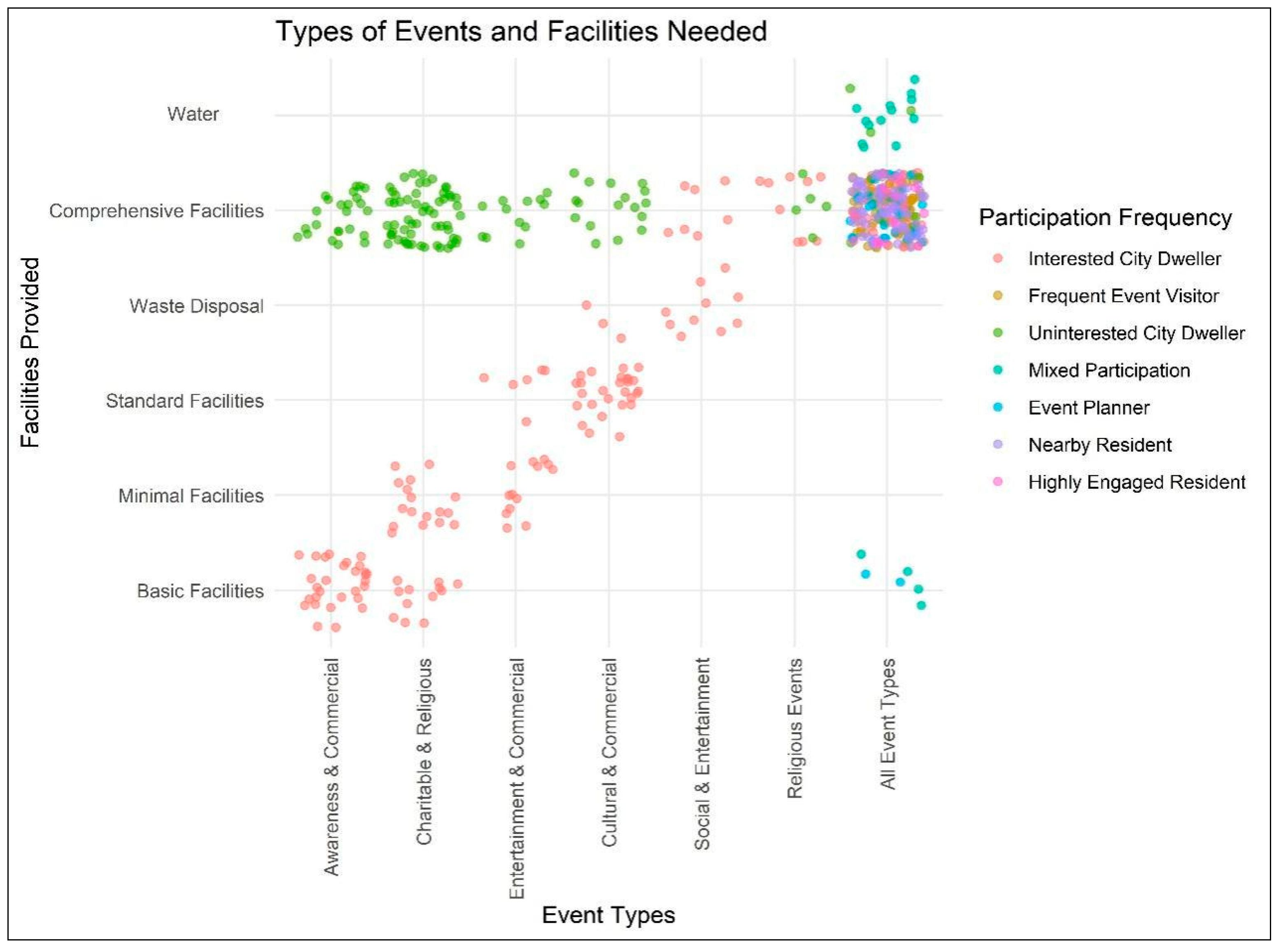

The levels of participant fulfillment and their accessibility to events depend heavily on the combination of essential event features including type, scale, duration along with access provisions. Different population segments tend to select between sports events, cultural programming, and commercial gatherings, whereas large gathering events usually achieve higher attendance figures. The size of the event directly impacts logistics management because it leads to increased challenges with respect to space distribution and transport solutions along with facility provision (

Figure 3).

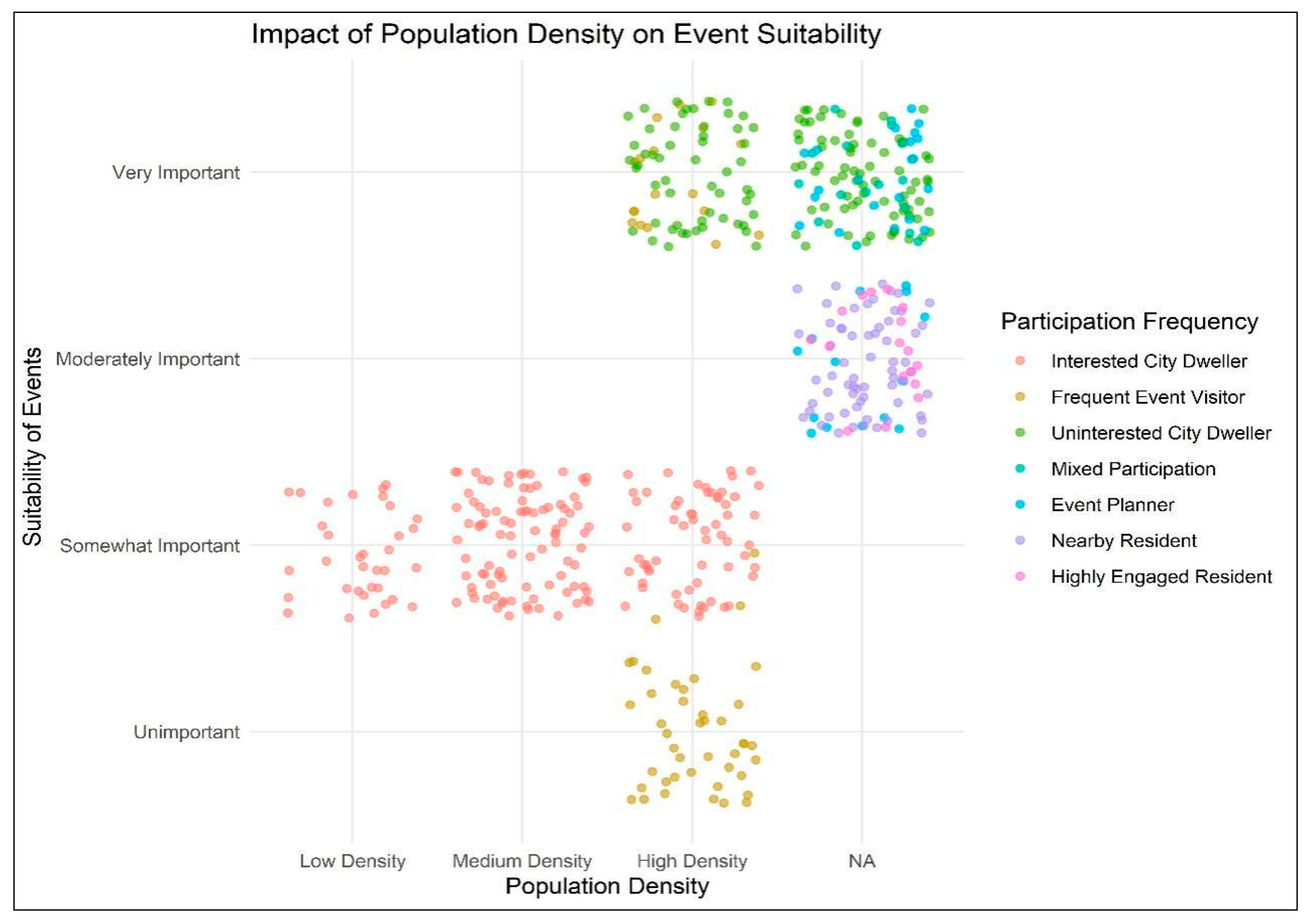

Population density is a significant consideration in a neighborhood’s ability to accommodate public events. Extremely dense neighborhoods offer high visibility and accessibility, ideal for large events; they are also prone to high noise, traffic, and enclosure issues (

Figure 4). Low-density neighborhoods offer more space, but are likely to suffer from issues of drawing patrons due to poor accessibility. Urban planners must weigh the potential of using high-visibility locations against the danger of overcrowding and resource exhaustion. Recognizing these dynamics, strategic planning can improve community participation and optimize the benefits of public events.

The preferences and perceptions about the events exhibited by the respondents show a correlation with their occupational professional status. Public servants tend to select events that follow the directions of governmental policy consisting of cultural or social events, while private sector staff tend to choose commercial and entertainment-based events (

Figure 5). Academic professionals tend to choose events that combine education with culture to stimulate intellectual development. Event planning should be inclusive because each sector demonstrates unique preferences that should guide planning decisions. Event organizers can design productions that appeal to larger audiences due to their enrollment in demographic correlations to create better community satisfaction and social bonds.

The interrelated links illustrated by the correlation graphs dictate how demographic factors and event attributes interact with population density to align the interests of various professions and ensure event success. The insights derived from these data points help create events that address the diverse needs of urban residents and enhance the humanization and vibrancy of urban spaces.

4.3. Participation in Neighborhood Events

To examine the relationship between demographic characteristics and participation in neighborhood public events, Chi-Square Tests (χ2) and Measures of Association (Cramer’s V) were conducted. The variables analyzed included gender, age, employment sector, and the perceived importance of neighborhood events. The results revealed statistically significant associations across all variables, offering a nuanced understanding of how these factors influence civic engagement in Riyadh.

Gender vs. Participation: The analysis yielded a chi-square statistic of χ

2 = 677.89 with a

p-value < 0.001, indicating a statistically significant association between gender and participation in community events (

Table 1). This moderate association (Cramer’s V = 0.33) suggests that gender plays a meaningful role in shaping attendance patterns. In the context of Riyadh’s cultural landscape, this finding highlights potential disparities in access, preferences, or social roles between male and female participants, reinforcing the need for gender-sensitive event planning.

Age vs. Participation: Age was found to be a significant determinant of event engagement, with a moderate association (Cramer’s V = 0.32). Younger participants tended to favor dynamic, entertainment-oriented events, while older individuals prioritized accessibility and relevance to their lived experiences. These findings underscore the importance of age-sensitive programming to ensure inclusivity across generational lines.

Gender and Participation: The moderate association between gender and participation (Cramer’s V = 0.33) reinforces the need to consider gender-specific preferences and barriers. Differences in leisure activities, social roles, and cultural expectations may influence how men and women engage with public events, necessitating thoughtful design and outreach strategies.

Employment and Participation: Although statistically significant, the association between employment sector and participation was weaker (Cramer’s V = 0.23). This suggests that while professional context such as work schedules or institutional culture affects engagement, it is not the primary driver. Nonetheless, tailoring event timing and format to accommodate diverse work patterns could enhance accessibility.

Importance of Events and Participation: The strongest association was observed between the perceived importance of neighborhood events and actual participation (Cramer’s V = 0.37). This finding confirms that value-driven engagement is a key motivator, aligning with theories of place attachment, civic identity, and community cohesion. Strategic communication and cultural framing can therefore play a vital role in increasing participation.

Collectively, these results reveal a layered pattern of cultural participation in Riyadh. Perceived importance and age emerge as central factors, while gender and employment play secondary roles. These patterns reflect broader urban dynamics in Gulf cities, where rapid modernization intersects with traditional social structures. For urban planners and cultural policymakers, the findings suggest that effective event design must prioritize accessibility, cultural relevance, and demographic sensitivity to foster stronger community cohesion.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the feasibility of hosting public events in residential neighborhoods of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, by examining the interconnections between urban design and community participation. The findings align with the established academic proposition that urban neighborhoods play an essential role in fostering social cohesion and cultural exchange. Public events, in particular, serve as key catalysts for shaping community identities and shared urban experiences [

13,

14]. To explore this potential, the research adopted a quantitative approach, collecting data from 510 Riyadh residents and analyzing their demographic characteristics, event-related factors, and participation patterns. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and Chi-square tests were employed to address the study objectives.

The quantitative analysis provided critical insights into the suitability of residential neighborhoods for hosting public events. The findings suggest that neighborhood parks ranging from 1000 to 5000 square meters, especially those situated on main streets with a width of 20–30 m, are appropriate venues. These locations are ideal for smaller community gatherings, aligning with the principles of human-scale urbanism, where spatial legibility and walkability improve urban life by creating accessible, inclusive, and sociable environments [

27,

33]. However, the successful implementation of such events necessitates that policymakers and organizers ensure comprehensive infrastructure, including seating, restrooms, waste management systems, water coolers, electricity, and mosques [

30,

38]. This highlights that the nature, scale, timeframe, and accessibility of events are crucial determinants of participant satisfaction and the overall success of public gatherings in these spaces.

Correlation analysis further illuminated how various factors influence the functionality of public events. The study revealed significant insights tied to age, with older respondents showing a greater preference for religious and community-building activities, whereas younger respondents favored entertainment and cultural events. Occupation also played a role; public sector employees tended to select cultural events, while private sector workers preferred commercial and entertainment themes. Additionally, the analysis indicated that workers, in general, prefer evening events to accommodate their professional schedules. These findings are consistent with existing literature, underscoring the necessity for event organizers to consider demographic characteristics when planning to meet diverse community needs [

31,

47,

48]. The analysis also highlighted that population density within a neighborhood impacts event suitability, influencing both accessibility and noise concerns due to increased traffic and limited space in dense areas [

35]. Event planners must balance resource management with enhanced visibility to create effective and inclusive events. These results are in line with research on place attachment, where individuals’ emotional and behavioral connections to public spaces are shaped by their life stage, social identity, and cultural expectations [

35,

36,

47,

49].

The Chi-square tests demonstrated that gender, age, and occupation are significant factors influencing event participation. The results showed that medium-sized events in accessible locations attract a greater proportion of younger people, particularly females. This highlights potential differences in event accessibility or preferences between genders and emphasizes the need for thoughtful event planning to ensure inclusiveness and social sustainability [

50,

51,

52]. Similarly, age has a significant impact, as different age groups have varying interests and capacities for participation, influenced by factors like time availability, curiosity, and accessibility. The findings suggest that young people can be a primary participant group in neighborhood events, alongside older individuals who also engage in urban activities. Employment status further affects participation, as different work cultures and schedules influence attendance. This information underscores the need for targeted interventions, such as creating events that attract a wider range of participants and removing barriers for specific population groups. Aligning with current literature [

51,

53], urban planners and policymakers must consider demographic diversity and density to create events that foster inclusive, culturally dynamic, and socially cohesive urban settings.

Public events in residential neighborhoods can significantly strengthen social bonds and community identity, particularly in a rapidly developing city like Riyadh. The study concludes that Riyadh needs a strategic approach to event management, combined with improved infrastructure and inclusive policies, to enhance public event experiences. This research advances the understanding of urban humanization [

54] by emphasizing the role of public events in shaping urban experiences. The findings can offer valuable guidance to other cities facing similar challenges in adapting traditional social habits to modern urban environments.

The findings of this study are well-supported by existing literature. The emphasis on retrofitting parks with essential infrastructure and adopting flexible urban design is consistent with Qi et al. (2024) [

14], who stress the importance of well-equipped public spaces for social cohesion. Similarly, the call for modular urban design reflects the insights of the Urban Design Lab (2024) [

40], which advocates for adaptable architecture. The need for updated zoning regulations and simplified permitting processes echoes the guidance from Generis Online (2024) [

41], highlighting the balance between community engagement and residential integrity. Furthermore, the research supports Loh et al. (2022) [

42] by recognizing creative placemaking as a tool for embedding cultural identity into neighborhood planning. Finally, the participatory planning approach aligns with Mendhe (2024) [

43], who argues that community involvement is essential for inclusive and sustainable urban interventions. These convergences reinforce the validity of the study’s recommendations, underscoring the importance of integrated, community-centered planning in enhancing the livability and vibrancy of residential neighborhoods.

In Riyadh, cultural participation is segmented by generation and occupation, revealing a dual trajectory that reflects the city’s evolving urban identity. Younger residents (ages 18–30) show a marked preference for entertainment and creative events, signaling a shift toward urban expressiveness and social engagement. In contrast, older residents (ages 46 and above) continue to favor community-based gatherings, indicating the persistence of traditional collective values. This duality illustrates the coexistence of modernity and heritage within Riyadh’s urban fabric. It suggests that cultural participation is not a unified phenomenon but is segmented along generational lines, with each group engaging with public spaces in distinct ways. These findings align with broader urban studies that emphasize how age and life stage shape cultural preferences and spatial behavior. Occupational affiliation further reinforces this segmentation. Public sector employees tend to favor cultural and civic events, reflecting an alignment with institutional values. Meanwhile, private sector workers show a stronger inclination toward commercial and entertainment-oriented activities, which may be influenced by market-driven lifestyles. Academic professionals, on the other hand, exhibit preferences for intellectually stimulating events that blend education with cultural enrichment. These findings contribute to a conceptual framework for cultural urbanism in Riyadh, positioning public events as dynamic tools for negotiating identity, space, and community in a rapidly transforming Gulf metropolis. This framework reframes cultural participation not as a passive outcome but as an active process of urban co-creation, where residents engage with their environment through culturally significant practices. The study highlights the importance of demographic sensitivity and cultural responsiveness in urban event planning. By acknowledging the differentiated needs and aspirations of Riyadh’s residents, urban initiatives can foster stronger community bonds, support cultural expression, and contribute to the humanization of the city. This approach aligns with contemporary urban theory and provides practical insights for cities across the Gulf region seeking to balance tradition with innovation in their public space strategies.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, Urban planners should designate and retrofit neighborhood parks and open spaces as flexible event venues, ensuring they are equipped with essential infrastructure such as restrooms, seating, and waste disposal systems. Where zoning regulations should be updated to allow temporary public events in residential areas, with clear guidelines on noise, traffic, and safety management. Event permitting processes should be simplified to encourage community-led initiatives, especially those that promote cultural diversity and social cohesion.

Correspondingly Urban design strategies should incorporate modular and multi-use elements that support both daily use and occasional events, such as shaded seating, open lawns, and integrated mobility access. Also, public transportation and micro-mobility infrastructure should be enhanced to improve accessibility to event venues. Municipalities should engage residents in participatory planning processes to ensure that event programming reflects local needs and preferences.

This study offers valuable insights into event suitability in Riyadh but is limited by its reliance on digitally active, self-selected respondents. Such sampling may exclude older adults and individuals with limited digital literacy, especially in a context where gender norms and cultural expectations influence access to digital platforms and participation in academic surveys. However, to better understand these limitations, it is essential to consider Saudi Arabia’s demographic profile. The Kingdom is a predominantly young society, with 60% of its population under the age of 30. Children aged 0–14 constitute 22.46%, while youth aged 15–24 represent 15.25% [

54,

55]. This demographic composition offers significant potential for vibrant civic engagement. Additionally, the study’s cross-sectional design limits understanding of how preferences evolve over time, particularly amid rapid social change driven by Vision 2030. To address these gaps, future research should adopt longitudinal or mixed-methods approaches, combining online and offline tools. Expanding to other Saudi or Gulf cities and explicitly considering the interplay of digital literacy, gender norms, and cultural dynamics will support more inclusive and context-sensitive urban planning.