The Impact of Contract Functions on Contractors’ Performance Behaviors: A Mixed-Methods Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Contract Functions in Construction

2.2. Contractors’ Performance Behaviors

3. Hypothesis Development and Theoretical Model

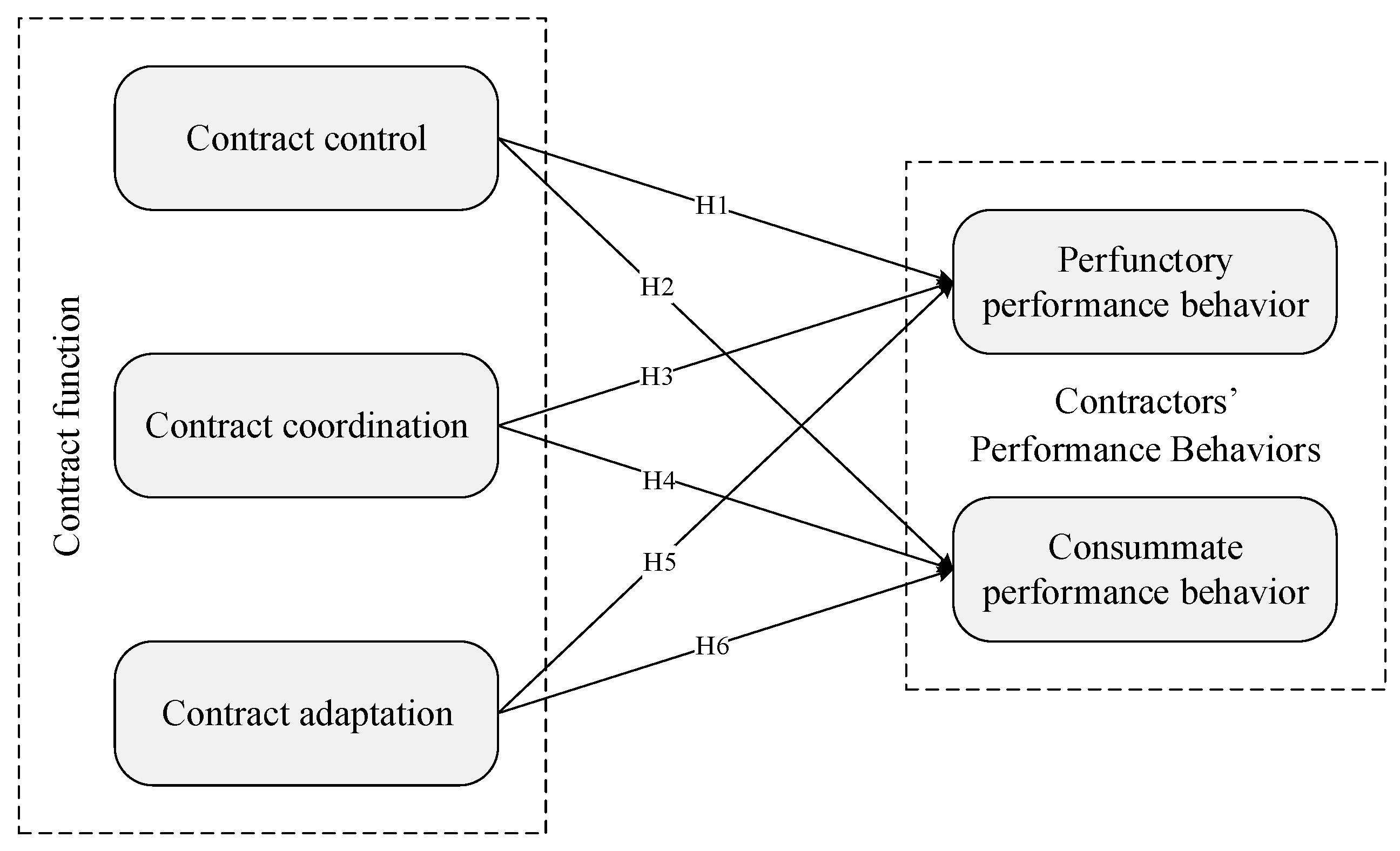

3.1. Contract Control and Contractors’ Performance Behavior

3.2. Contract Coordination and Contractors’ Performance Behavior

3.3. Contract Adaptation and Contractors’ Performance Behavior

4. Methods

4.1. Questionnaire Design

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Common Method Bias (CMB)

5. Data Analysis and Findings

5.1. Reliability and Validity Test

5.2. Model Fit and Hypothesis Testing

5.3. Qualitative Analysis: Feedback and Explanations from Experts

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion of Results

6.2. Theoretical Contribution

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi, B.; Nie, N.L.S. Effects of contractual and relational governance on project performance: The role of BIM application level. Buildings 2024, 14, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seboka, D.A.; Gidebo, F.A. Investigating the effectiveness of contract administration at construction stage to averting substandard construction performance: In Shagar city public building projects. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Addressing project complexity: The role of contractual functions. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, R.J.; Sabel, C.F.; Scott, R.E. Braiding: The interaction of formal and informal contracting in theory, practice, and doctrine. Columbia Law Rev. 2010, 110, 1377–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schepker, D.J.; Oh, W.Y.; Martynov, A.; Poppo, L. The many futures of contracts: Moving beyond structure and safeguarding to coordination and adaptation. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fu, Y.; Kang, F. How to foster contractors’ cooperative behavior in the Chinese construction industry: Direct and interaction effects of power and contract. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Lu, W.; Kang, F.; Zhang, L. How to foster relational behavior in construction projects: Direct and mediating effects of contractual complexity and regulatory focus. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Chong, H.Y. Influence of prior ties on trust and contract functions for BIM-enabled EPC megaproject performance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yao, H. Effect of contractual functions on contractors’ consummate performance behaviors in construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wang, D.; Yin, Y.; Liu, H.; Deng, B. Response of contractor behavior to hierarchical governance: Effects on the performance of mega-projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 1661–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Guo, L.; Ning, Y. Understanding construction contractors’ intention to undertake consummate performance behaviors in construction projects. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3935843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Y. How does contractual governance affect construction project performance? The mediating role of the contractor’s behavior. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 3879–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Skitmore, M.; Yan, L. How contractor behavior affects engineering project value-added performance. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumineau, F. How contracts influence trust and distrust. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1553–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Fu, H. A governance framework for the sustainable delivery of megaprojects: The interaction of megaproject citizenship behavior and contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Chong, H.Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, X. Joint contract–function effects on BIM-enabled EPC project performance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; You, J. Understanding the multiple functions of construction contracts: The anatomy of FIDIC model contracts. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 36, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y. Contractual complexity in construction projects: Conceptualization, operationalization, and validation. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, G.; Xu, Y. Can joint-contract functions promote PPP project sustainability performance? A moderated mediation model. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2667–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. Control, coordination, and adaptation functions in construction contracts: A machine-coding model. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Chen, Y.; Lai, J.; Meng, F. Multifunctional analysis of construction contracts using a machine learning approach. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40, 04024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Yuan, J.; Tang, Y.; Xiahou, X.; Li, Q. Exploring the impact of collaboration on BIM use effectiveness: A perspective through multiple collaborative behaviors. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y. Impact of quality performance ambiguity on contractor’s opportunistic behaviors in person-to-organization projects: The mediating roles of contract design and application. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Zeng, Q. Exploring the relationship between governance mechanisms and contractor behaviors: Insights from fairness perception. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Yan, L. The role of contract flexibility in shaping contractor behaviour: A parallel mediation analysis of trust and control. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2025, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, Q.C. The effects of joint-contract functions on PPP project value creation: A mediation model. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 4162–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, M.; Elsherbeny, H.A. Operational framework for managing construction-contract administration practitioners’ perspective through modified Delphi method. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Chong, H.Y.; Xu, Y. The effects of shared vision on value co-creation in megaprojects: A multigroup analysis between clients and main contractors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yao, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y. Comparing subjective and objective measurements of contract complexity in influencing construction project performance: Survey versus machine learning. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 04023017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yue, M.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, S. How to build interorganizational trust in construction projects: A meta-analysis on three trust-building mechanisms. J. Manag. Eng. 2025, 41, 04025024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O.K.; Kristiansen, H.N. Partnering contracts and conflict levels in Norwegian construction projects. Buildings 2025, 15, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhang, L. The opportunism-inhibiting effects of the alignment between engineering project characteristics and contractual governance: Paired data from contract text-mining and survey. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 15110–15124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Lu, W.; Li, J.; Gao, X. Are trust and distrust antithetical? Explores the impacts on conflict management styles and subjective values in the construction industry. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Jia, J.; Le, Y.; Liu, T.; Xue, Y. Mitigating the aftermath of relationship conflict between the owners and contractors: A contract enforcement approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y. Understanding the double-edged sword effect of contract flexibility on contractor’s opportunistic behavior in construction project: Moderating role of BIM application degree. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L. Incentive contract design and selection for inhibiting unethical collusion in construction projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 870–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Yan, L.; Yin, Y. Trust or fairness is more important: Research on the mechanism of contract risk allocation inducing contractor to consummate performance behavior. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2946–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, B. How building information modelling mitigates complexity and enhances performance in large-scale projects: Evidence from China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2025, 43, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. (IJEC) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Haapasalo, H. Development levels of stakeholder relationships in collaborative projects: Challenges and preconditions. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2023, 16, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumineau, F.; Long, C.; Sitkin, S.B.; Argyres, N.; Markman, G. Rethinking control and trust dynamics in and between organizations. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 60, 1937–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilke, O.; Lumineau, F. The double-edged effect of contracts on alliance performance. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2827–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.Z.; Chao, L.; Wang, C.; Awan, S.H. The role of trust, opportunism and adaptation in coordination and contract cooperation: Evidence from construction projects. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2025, 41, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraket, J.; Loosemore, M. Co-creating social value through cross-sector collaboration between social enterprises and the construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 36, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, G.; Xu, Y.; Chi, M. Enhancing trust between PPP partners: The role of contractual functions and information transparency. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211038245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, G. How does contractual flexibility affect a contractor’s opportunistic behavior? Roles of justice perception and communication quality. Buildings 2023, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Huang, L. What makes contract flexibility a double-edged sword: The impact of multi-level contextual embedding factors in China. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Fu, H.; Fang, S. The efficacy of trust for the governance of uncertainty and opportunism in megaprojects: The moderating role of contractual control. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wen, S.; Li, Q. How the two-tier cross-domain control influence contractor’s design behavior: A configurational analysis. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawi, H.; Elbeltagi, E.; Eid, M.S.; Alattyih, W.; Wefki, H. Construction payment automation through scan-to-BIM and blockchain-enabled smart contract. Buildings 2025, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osifo, E.O.; Omumu, E.S.; Alozie, M. Evolving contractual obligations in construction law: Implications of regulatory changes on project delivery. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 25, 1315–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chong, H.Y.; Chi, M. Impact of contractual flexibility on BIM-enabled PPP project performance during the construction phase. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2022, 28, 04021057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, K.K.; Gunduz, M.; Falamarzi, M.H. Assessment of construction project contractor selection success factors considering their interconnections. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 3677–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Contract control (CT) | CT1: The contract defines the rights of both parties specifically. | [3,7] |

| CT2: The contract specifically stipulates the rights entitled to one party when the other party breaches the contract. | ||

| CT3: The contract specifically stipulates provisions on early termination after breaching the contract. | ||

| CT4: The contract specifically stipulates how the party awarding the contract monitors the contractor. | ||

| Contract coordination (CD) | CD1: The contract provides detailed technical specifications and drawings. | [3,7] |

| CD2: The contract specifically stipulates the quality acceptance procedures. | ||

| CD3: The contract specifically stipulates the personnel qualifications or dispatching issues. | ||

| CD4: The contract defines the division of labor of both parties specifically. | ||

| Contract adaptation (CA) | CA1: The contract specifically stipulates the adjustments due to the changes in cost. | [3,7] |

| CA2: The contract specifically stipulates the adjustments due to the changes in exchange rates. | ||

| CA3: The contract specifically stipulates the handling procedures when climatic conditions, against which an experienced contractor could not reasonably have been expected to react, arises. | ||

| CA4: The contract specifically stipulates the handling procedures when geological conditions, against which an experienced contractor could not reasonably have been expected to react, arise. | ||

| Perfunctory performance behavior (PPB) | PPB1: The contractor can carry out the construction according to the construction drawings and standard specifications provided by the employer. | [10,13] |

| PPB2: The contractor can carry out the construction according to the contract requirements or agreement. | ||

| PPB3: The contractor can complete all the ancillary tasks required by the project. | ||

| PPB4: The contractor can complete the construction tasks stipulated in the contract or agreement. | ||

| Consummate performance behavior (CPB) | CPB1: The contractor will volunteer to make an extra effort for the project. | [10,13] |

| CPB2: The contractor will take the initiative to put forward reasonable proposals for the employer. | ||

| CPB3: The contractor will help the relevant participants to adapt to the construction site. | ||

| CPB4: The contractor will voluntarily inform the employer of the drawings or the errors or omissions in the contract. | ||

| CPB5: The contractor will actively control and internalize project risks and reflow the risk back to the employer. |

| Characteristic | Count | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | Doctor’s degree | 12 | 3.48 |

| Master’s degree | 101 | 29.28 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 224 | 64.93 | |

| College degree or below | 8 | 2.32 | |

| Working experience (years) | <5 | 33 | 9.57 |

| 5–10 | 171 | 49.57 | |

| 10–15 | 92 | 26.67 | |

| ≥15 | 49 | 14.20 | |

| Job title | General manager | 19 | 5.51 |

| Project manager | 75 | 21.74 | |

| Site manager | 72 | 20.87 | |

| Chief engineer | 60 | 17.39 | |

| Business manager | 92 | 26.67 | |

| Other managers | 27 | 7.83 | |

| Latent Variable | Item | Factor Loading | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | CT1 | 0.856 | 0.800 | 0.868 | 0.622 |

| CT2 | 0.893 | ||||

| CT3 | 0.873 | ||||

| CT4 | 0.902 | ||||

| CD | CD1 | 0.783 | 0.747 | 0.839 | 0.565 |

| CD2 | 0.766 | ||||

| CD3 | 0.817 | ||||

| CD4 | 0.838 | ||||

| CA | CA1 | 0.840 | 0.749 | 0.841 | 0.570 |

| CA2 | 0.885 | ||||

| CA3 | 0.868 | ||||

| CA4 | 0.819 | ||||

| PPB | PPB1 | 0.887 | 0.783 | 0.858 | 0.576 |

| PPB2 | 0.962 | ||||

| PPB3 | 0.914 | ||||

| PPB4 | 0.932 | ||||

| CPB | CPB1 | 0.782 | 0.816 | 0.871 | 0.602 |

| CPB2 | 0.756 | ||||

| CPB3 | 0.758 | ||||

| CPB4 | 0.753 | ||||

| CPB5 | 0.786 |

| CT | CD | CA | PPB | CPB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 0.788 | — | — | — | — |

| CD | 0.606 | 0.752 | — | — | — |

| CA | 0.663 | 0.633 | 0.755 | — | — |

| PPB | 0.251 | 0.299 | 0.105 | 0.776 | — |

| CPB | 0.079 | 0.269 | 0.268 | 0.099 | 0.759 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Coefficient (β) | T Statistics | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CT→PPB | 0.256 | 3.811 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | CT→CPB | −0.249 | 2.726 | 0.006 | Supported |

| H3 | CD→PPB | 0.194 | 2.401 | 0.016 | Supported |

| H4 | CD→CPB | 0.245 | 3.347 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | CA→PPB | −0.198 | 2.467 | 0.014 | Supported |

| H6 | CA→CPB | 0.290 | 3.542 | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J. The Impact of Contract Functions on Contractors’ Performance Behaviors: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Buildings 2025, 15, 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193438

Yang M, Chen H, Xu Y, Wu J. The Impact of Contract Functions on Contractors’ Performance Behaviors: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193438

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Mingzhu, Haitao Chen, Yongshun Xu, and Jinjian Wu. 2025. "The Impact of Contract Functions on Contractors’ Performance Behaviors: A Mixed-Methods Approach" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193438

APA StyleYang, M., Chen, H., Xu, Y., & Wu, J. (2025). The Impact of Contract Functions on Contractors’ Performance Behaviors: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Buildings, 15(19), 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193438