Sustainability Meets Society: Public Perceptions of Energy-Efficient Timber Construction and Implications for Chile’s Decarbonisation Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

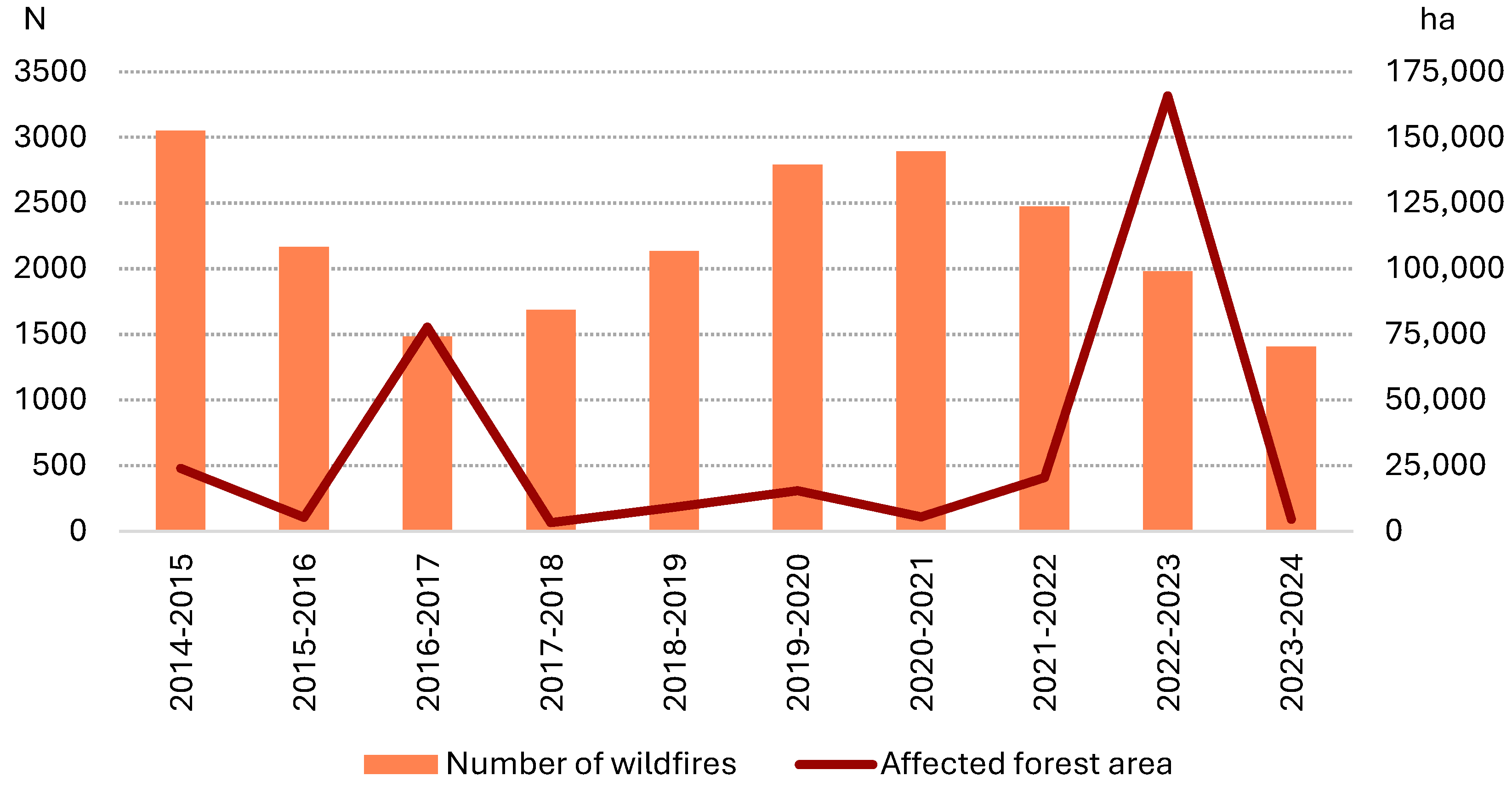

1.1. The Perception of Timber Construction Revisited

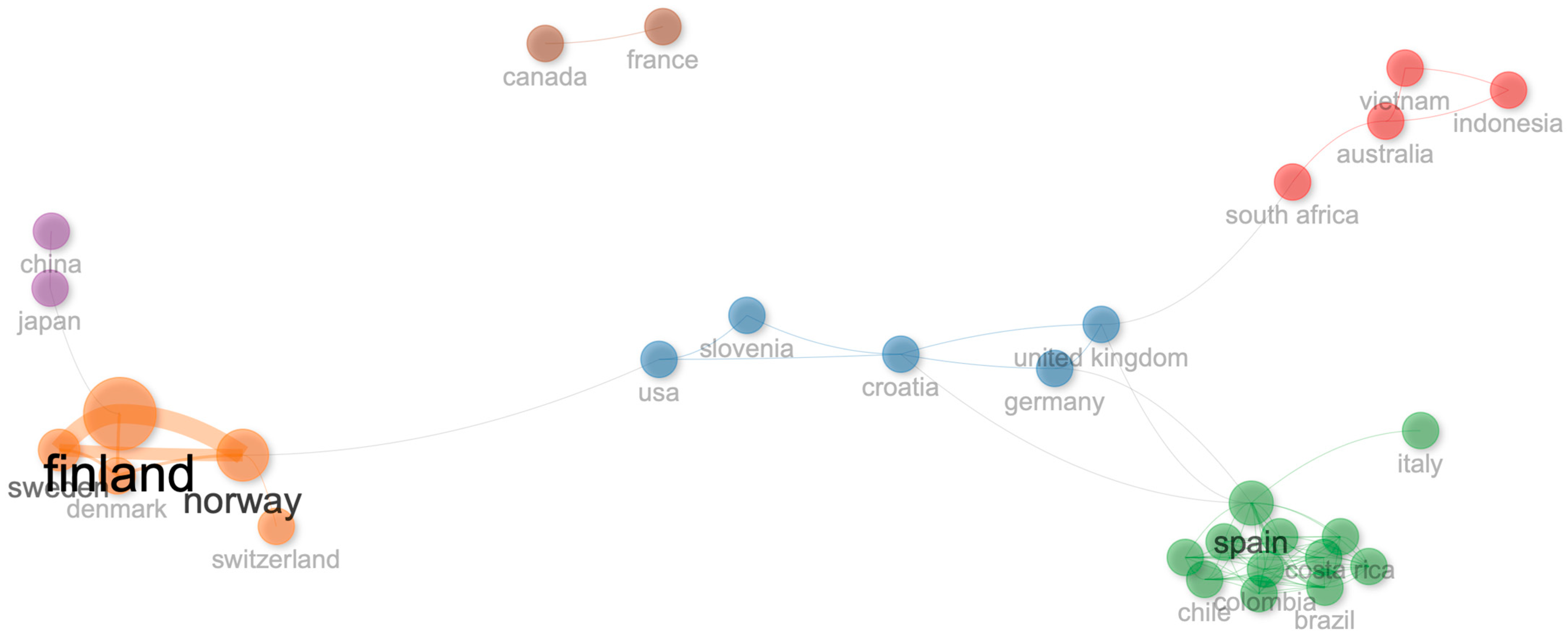

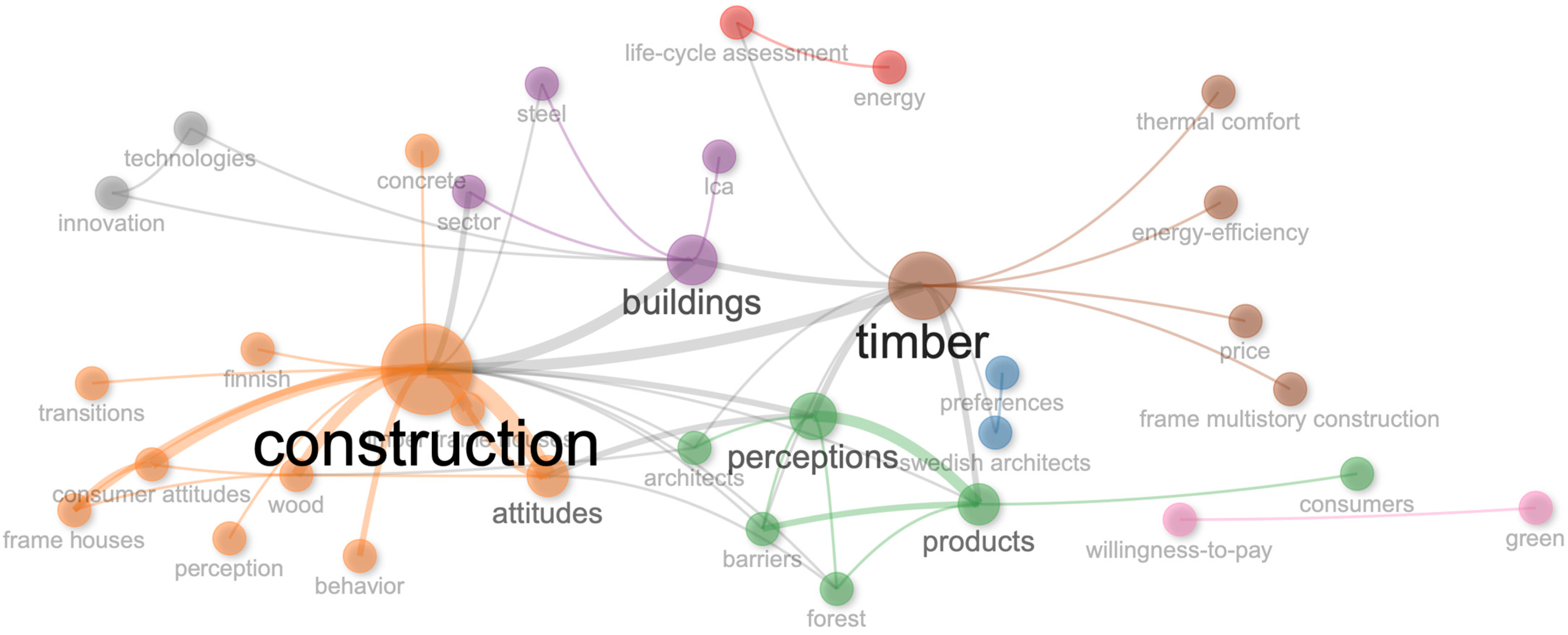

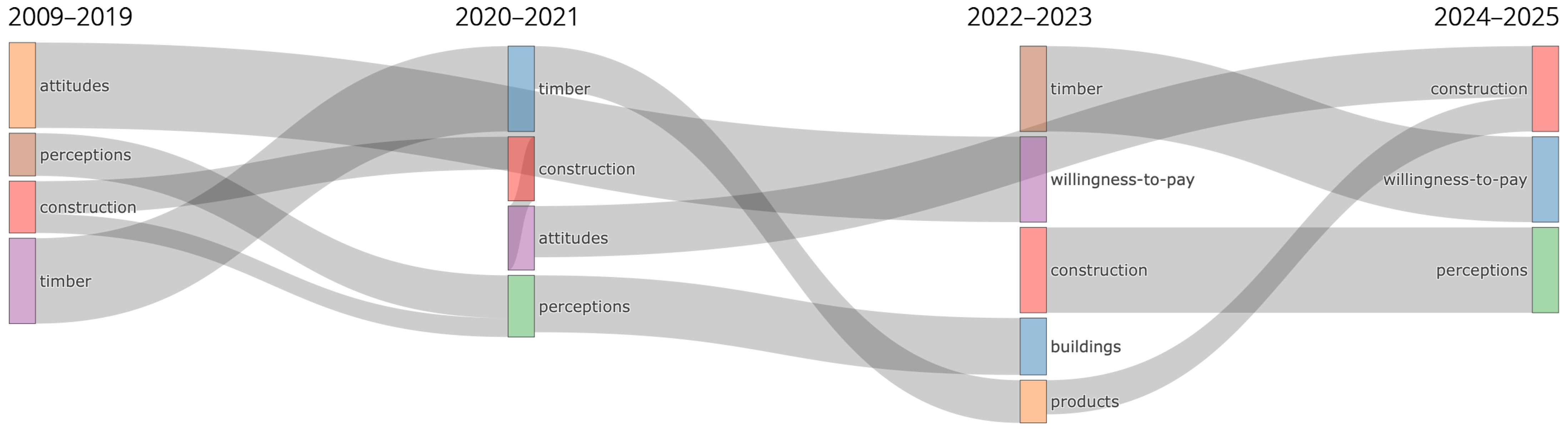

1.2. Bibliometric Analysis

2. Methodology

2.1. The Survey

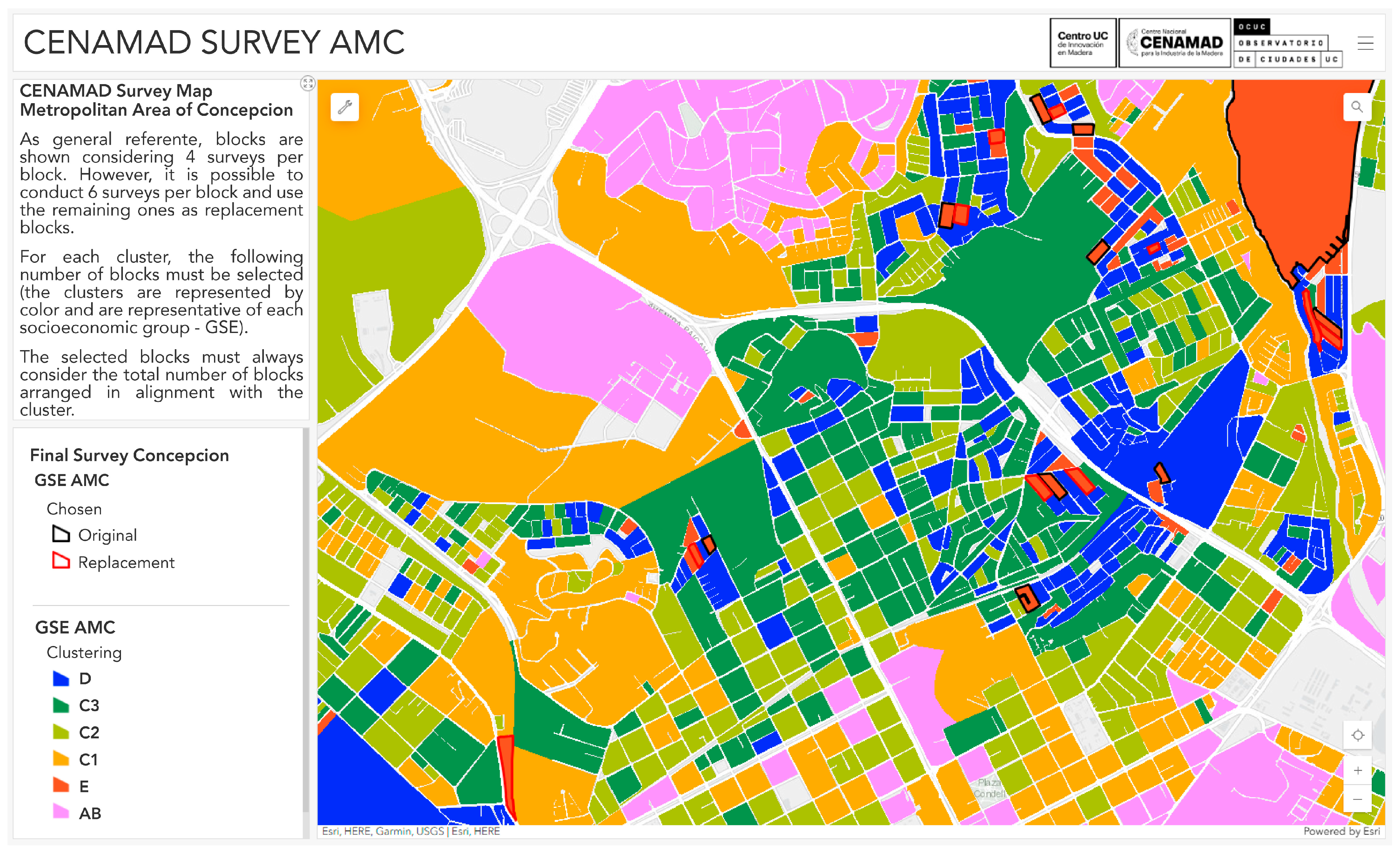

2.2. The Spatial Sampling

- When the increase in the ratio is marginal with the growth of K clusters.

- The ratio is greater than 0.85, and the within-cluster variance is less than one year of individual education for all clusters.

- That no overlap occurs in cluster recognition and that it is assimilable to a concept, in this case, socio-economic.

- The total within-cluster sum of squares: 8.71472.

- The between-cluster sum of squares: 154.542.

- The ratio of the between-cluster sum of squares to the total sum of squares: 0.946619.

2.3. Principal Component Analysis and Cluster Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Exploratory Analysis

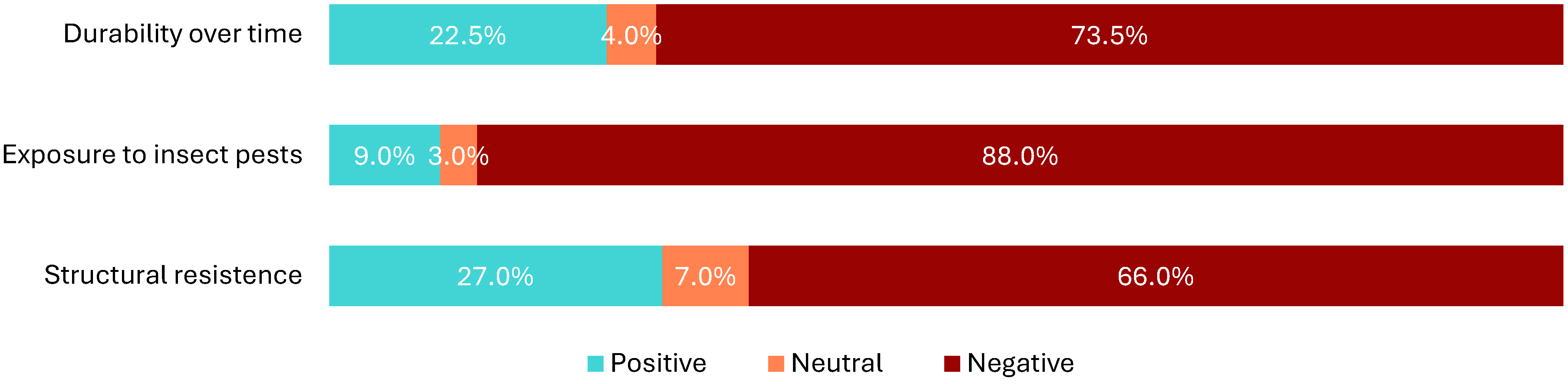

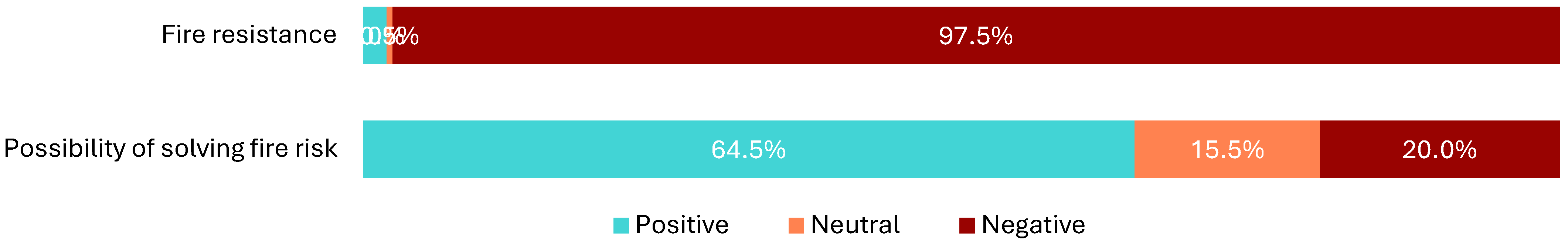

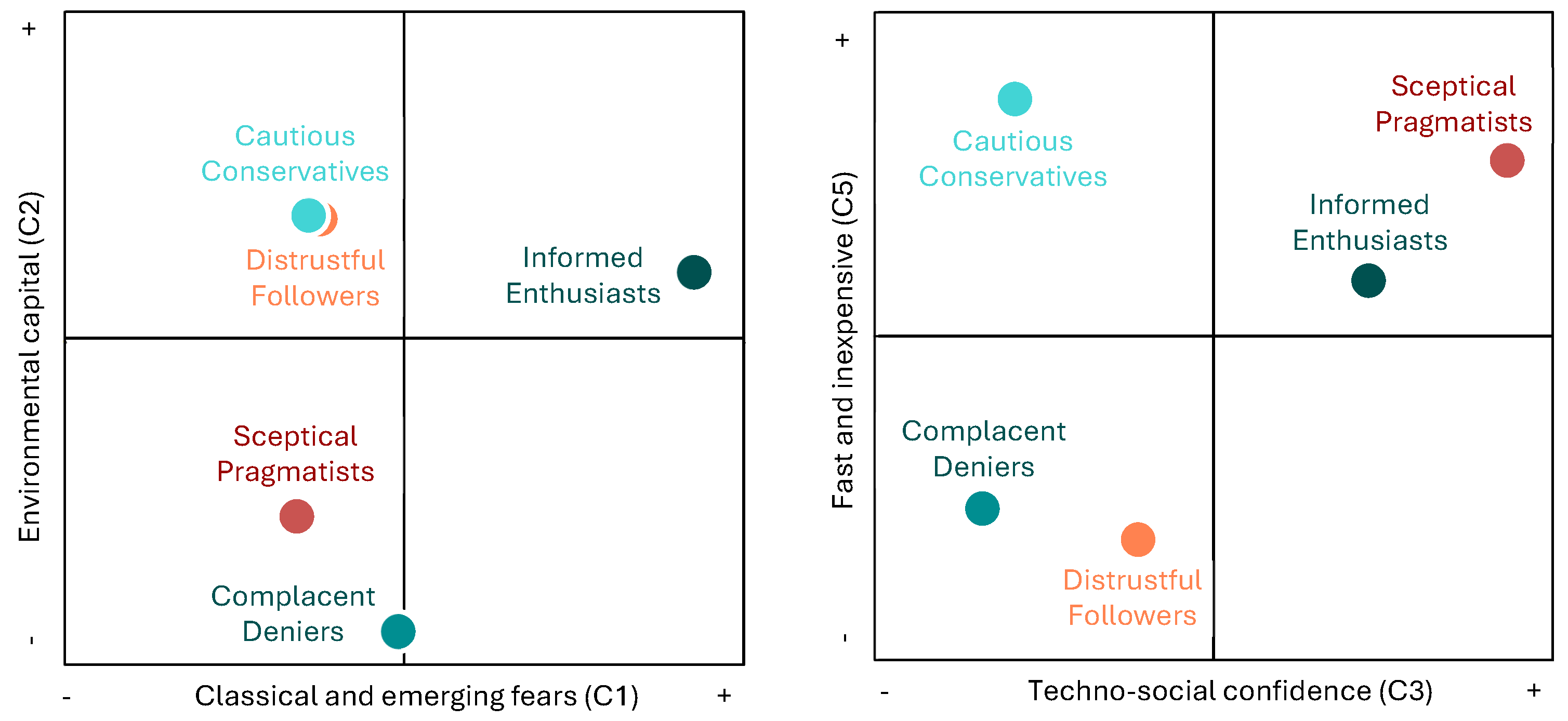

- Classical and emerging fears (C1): This component captures negative perceptions of timber construction, encompassing its presumed shorter service life, heightened vulnerability to insects, lower structural capacity, reduced fire resistance, and the belief that its use accelerates deforestation.

- Environmental capital (C2): Respondents associate timber with positive environmental qualities, highlighting its potential contribution to climate-change mitigation, superior thermal comfort, and a favourable appraisal of the timber industry’s role in national development.

- Techno-social confidence (C3): This dimension reflects confidence in technological solutions and social capital: respondents recognise the technical feasibility of mitigating fire risk, report improved acoustic performance, and link timber acceptance to higher educational attainment and occupational status.

- Industrial efficiency (C4): The component denotes positive views of prefabricated timber construction, stressing lower construction costs alongside reduced generation of waste and debris during the building process.

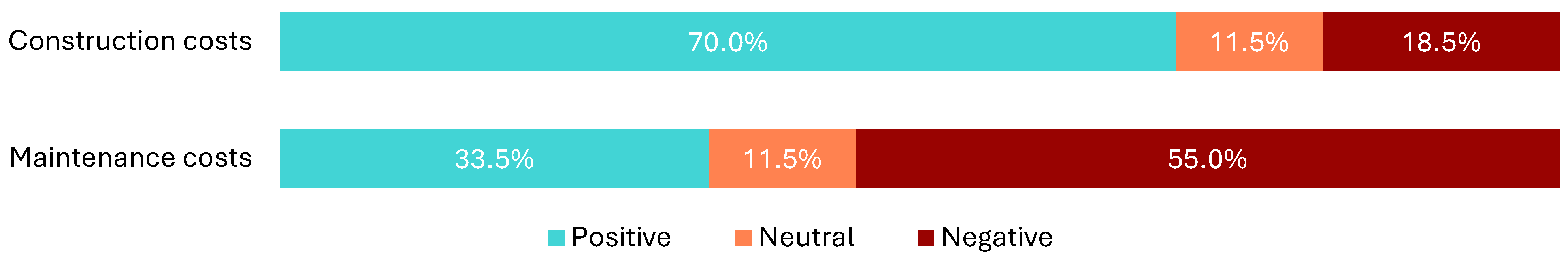

- Fast and inexpensive (C5): Here, timber is valued for economic expediency: lower initial and maintenance costs, coupled with substantially quicker construction times, position it as a cost-effective option.

- Conditional flexibility (C6): Perceptions are ambivalent: while acknowledging timber’s adaptability and ease of extension to meet changing household needs, respondents also recognise architectural design constraints inherent in prefabricated systems.

- Distrustful Followers (cluster 1, N = 61, 30.5%): Profile Individuals predominantly of low socio-economic status with school-level education; they associate timber with first homes, adopt energy-efficiency measures at home, are attuned to certification schemes, hold a favourable image of the timber industry, and exhibit a high willingness to live in a timber dwelling.

- Sceptical Pragmatists (cluster 2, N = 37, 18.5%): Mainly upper-middle and high socio-economic groups aged 45–65, possessing undergraduate or postgraduate degrees and mid-level executive occupations; they view timber primarily as social housing and maintain an unfavourable perception of the timber industry.

- Cautious Conservatives (cluster 3, N = 34, 17.0%): Respondents primarily of low socio-economic status with school education and manual occupations; this cluster has a high proportion of older adults, links timber to first-home ownership, relies on public transport, shows little enthusiasm for architectural contemporary design, yet retains a very positive image of the timber industry.

- Complacent Deniers (cluster 4, N = 26, 13.0%): Predominantly middle socio-economic levels (C2–C3), mostly men with technical education; they associate timber with emergency housing, judge the timber industry negatively, and display low willingness to occupy timber housing. Their notably negative view of the timber industry (the most relevant compared to the other clusters) hints at distrust in industry practices, which reinforces their low willingness to live in a timber home. In short, the ‘Complacent Deniers’ appear to be rooted in a socio-demographic segment that is comfortable with the status quo (conventional materials) and sceptical of timber’s touted benefits, perhaps due to a perception that wood construction is a step backwards in quality or safety. This insight, albeit based on the smallest cluster, points to the need for targeted education or demonstrations to reach this resistant segment.

- Informed Enthusiasts (cluster 5, N = 42, 21.0%): Principally high socio-economic status, aged 45–65 with university education and mid-level executive roles; they link timber to both first and holiday homes, are receptive to housing incentives, view the timber industry positively, and demonstrate high readiness to live in timber housing.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Q4.

- A wooden house lasts less than a brick or concrete construction.

- Q5.

- A wooden house is more exposed to insect pests.

- Q6.

- A wooden house is as resistant as a brick or concrete construction.

- Q7.

- A wooden house burns easily.

- Q8.

- The fire risk in a wooden house can be technically resolved.

- Q9.

- Wood construction helps combat climate change.

- Q10.

- The use of wood in construction leads to deforestation.

- Q11.

- A wooden house offers better thermal comfort than a brick or concrete construction.

- Q12.

- A wooden house has acoustic insulation problems.

- Q13.

- Building a wooden house is cheaper than a brick or concrete construction.

- Q14.

- A wooden house is more expensive to maintain.

- Q15.

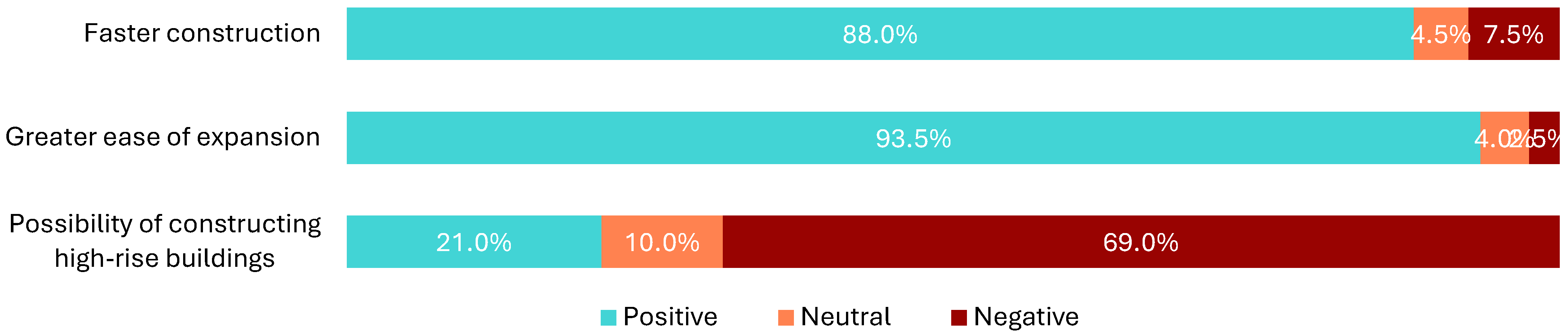

- A wooden house is faster to build than a brick or concrete construction.

- Q16.

- A wooden house is easier to expand according to the family’s needs.

- Q17.

- With wood, houses and high-rise apartment buildings can be constructed.

- Q18.

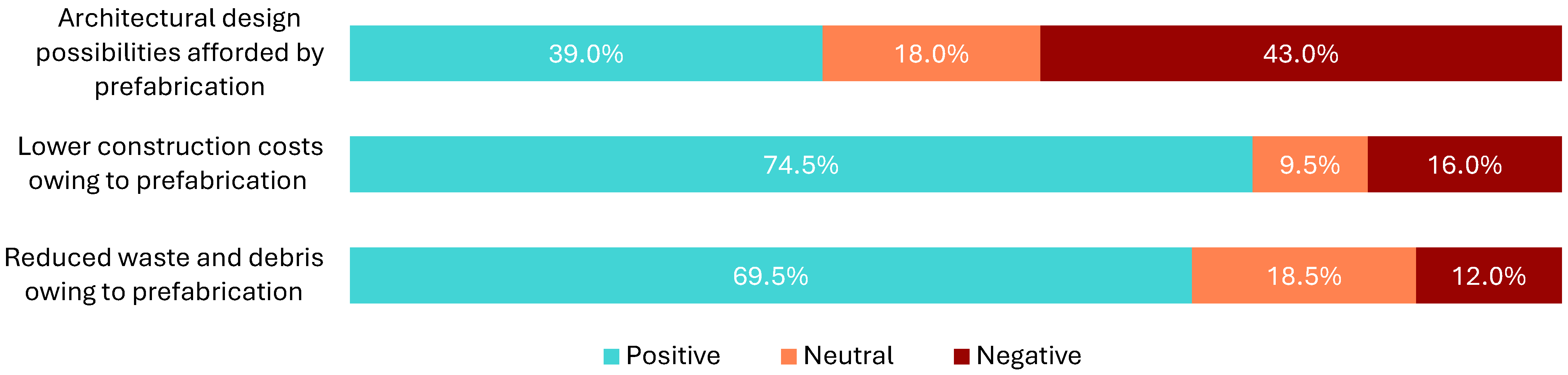

- Architectural design possibilities are more limited in a prefabricated wooden house (where components and modules are built in a factory and assembled on-site).

- Q19.

- A prefabricated wooden house is cheaper to build than one built traditionally (where it is completely done on-site).

- Q20.

- The construction of a prefabricated wooden house generates less waste and debris than one built in a traditional way (where it is completely done on-site).

| Questions | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Q4 | 75 | 37.5% | 72 | 36.0% | 8 | 4.0% | 39 | 19.5% | 6 | 3.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q5 | 88 | 44.0% | 88 | 44.0% | 6 | 3.0% | 16 | 8.0% | 2 | 1.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q6 | 9 | 4.5% | 45 | 22.5% | 14 | 7.0% | 71 | 35.5% | 61 | 30.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q7 | 115 | 57.5% | 80 | 40.0% | 1 | 0.5% | 4 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q8 | 35 | 17.5% | 94 | 47.0% | 31 | 15.5% | 26 | 13.0% | 14 | 7.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q9 | 15 | 7.5% | 57 | 28.5% | 43 | 21.5% | 62 | 31.0% | 23 | 11.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q10 | 75 | 37.5% | 69 | 34.5% | 25 | 12.5% | 27 | 13.5% | 4 | 2.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q11 | 43 | 21.5% | 38 | 19.0% | 13 | 6.5% | 94 | 47.0% | 12 | 6.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q12 | 48 | 24.0% | 84 | 42.0% | 17 | 8.5% | 46 | 23.0% | 5 | 2.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q13 | 63 | 31.5% | 77 | 38.5% | 23 | 11.5% | 33 | 16.5% | 4 | 2.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q14 | 36 | 18.0% | 74 | 37.0% | 23 | 11.5% | 56 | 28.0% | 11 | 5.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q15 | 80 | 40.0% | 96 | 48.0% | 9 | 4.5% | 14 | 7.0% | 1 | 0.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q16 | 81 | 40.5% | 106 | 53.0% | 8 | 4.0% | 4 | 2.0% | 1 | 0.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q17 | 8 | 4.0% | 34 | 17.0% | 20 | 10.0% | 67 | 33.5% | 71 | 35.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q18 | 27 | 13.5% | 59 | 29.5% | 36 | 18.0% | 71 | 35.5% | 7 | 3.5% | 200 | 100% |

| Q19 | 49 | 24.5% | 100 | 50.0% | 19 | 9.5% | 26 | 13.0% | 6 | 3.0% | 200 | 100% |

| Q20 | 52 | 26.0% | 87 | 43.5% | 37 | 18.5% | 19 | 9.5% | 5 | 2.5% | 200 | 100% |

References

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Ley 21455 Ley Marco de Cambio Climático; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MMA. 5to Informe Bienal de Actualización Ante La Convención Marco de Las Naciones Unidas Sobre Cambio Climático; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Victorero, F.; Caamaño, J.L.; Méndez, D. Ciudades Sostenibles En Madera: Políticas Públicas Para La Densificación de Ciudades Con Bajas Emisiones de Carbono. In Propuestas para Chile. Concurso Políticas Públicas 2024; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2025; pp. 79–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Anteproyecto Actualización de La Contribución Determinada a Nivel Nacional 2025; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ONG FIMA. Policy Brief: Anteproyecto de NDC En Chile: A Medio Camino Para Una Política de Cambio Climático Efectiva y Ambiciosa; ONG FIMA: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ECLP2050. Estrategia Climática de Largo Plazo Para Chile. Camino a La Carbono Neutralidad y Resiliencia a Más Tardar al 2050; Gobierno de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, N. The Quest for Balance: The Journey of Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yu, M. Green Bond Issuance and Green Innovation: Evidence from China’s Energy Industry. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 94, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lv, Y.; Wang, T.; Wan, S.; Ye, Y. Assessment of the Impacts of the Life Cycle of Construction Waste on Human Health: Lessons from Developing Countries. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 1348–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madera 21. En Biobío se firmó acuerdo por la construcción en madera. CORMA. 2024. Available online: https://www.corma.cl/blog/en-biobio-se-firmo-acuerdo-por-la-construccion-en-madera (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- DITEC. Construcción Sustentable. Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo: Santiago, Chile, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Ubilla, M.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C.; Schueftan, A. Perceptions, Tensions, and Contradictions in Timber Construction: Insights from End-Users in a Chilean Forest City. Buildings 2024, 14, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistema Integrado de Monitoreo de Ecosistemas Forestales Nativos de Chile (SIMEF) Región del Biobío. Available online: https://simef.minagri.gob.cl/herramientas/informacion-de-bosques-de-chile/ver/08 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Centro de Información de Recursos Naturales (CIREN) Observatorio Institucional. Available online: https://observatorio.ciren.cl/profile/geo-27/del-biobio (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Banco Internacional de Reconstrucción y Fomento. Los Bosques de Chile. Pilar Para Un Desarrollo Inclusivo y Sostenible; Banco Internacional de Reconstrucción y Fomento: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Innovum FCH. Fuerza Laboral de La Industria Forestal Chilena 2015–2030: Diagnóstico y Recomendaciones; Innovum, Fundación Chile (FCH) and Corporación de la Madera (CORMA): Santiago, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría Ejecutiva Comité Interministerial de Descentralización. Informe Fundado Para La Recomendación de Constitución Del Área Metropolitana Del “Gran Concepción”; Secretaría Ejecutiva Comité Interministerial de Descentralización: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Informe Anual de La Edificación 2014; INE: Santiago, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Lara, A.; Boisier, J.P.; Galleguillos, M. The Impacts of Native Forests and Forest Plantations on Water Supply in Chile. Forests 2019, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmayr, R.; Echeverría, C.; Lambin, E.F. Impacts of Chilean Forest Subsidies on Forest Cover, Carbon and Biodiversity. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAF Incendios. Resumen de Ocurrencia y Daño Por Comuna, 1985–2024. Centro Documental Corporación Nacional Forestal. Available online: https://www.conaf.cl/centro-documental (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Collect. Informe Estudio Cuantitativo “Madera Como Material Constructivo”; Preparado para Proyecto FONDECT D03I1020: Santiago, Chile, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate Web of Science. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Zhang, T.; Hu, Q.; Dewancker, B.J.; Gao, W. Comparative Assessment of Consumer Attitudes to Timber as a Construction Material in China and Japan. For. Prod. J. 2024, 74, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baul, T.K.; Atri, A.C.; Salma, U.; Alam, A.; Jashimuddin, M. Understanding Substitution Impacts of Harvested Wood and Processing Residues to Mitigate Climate Change: A Case of Chattogram, Bangladesh. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 15, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Størdal, S.; Gangsø, M.R.; Lien, G.; Sjølie, H.K. Drivers of Housing Developers’ Perception on Future Construction Reuse Material Premium for Wood. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Tang, T.K.H.; Lowe, A. Policy Forum: Opportunities and Challenges for Vietnamese Companies to Source Sustainable Timber from Africa, and Implications for Future Implementation of the EU Deforestation Regulation. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 170, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.; Jussila, J.; Häyrinen, L.; Lähtinen, K.; Mark-Herbert, C.; Toivonen, R.; Toppinen, A.; Roos, A. Unlocking Success: Key Elements of Sustainable Business Models in the Wooden Multistory Building Sector. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1364444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, F.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C.; Vergara-Perucich, F. When Residential Energy Labeling Becomes Irrelevant: Sustainability vs. Profitability in the Liberalized Chilean Property Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, F.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C.; Sánchez de la Flor, F.; Aguirre, C. Does Energy Efficiency Matter to Real Estate-Consumers? Survey Evidence on Willingness to Pay from a Cost-Optimal Analysis in the Context of a Developing Country. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 45, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, F.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C.; Wagemann, E.; Aguirre, C. Energy-Efficient Real Estate or How It Is Perceived by Potential Homebuyers in Four Latin American Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viholainen, N.; Franzini, F.; Lähtinen, K.; Nyrud, A.Q.; Widmark, C.; Hoen, H.F.; Toppinen, A. Citizen Views on Wood as a Construction Material: Results from Seven European Countries. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, B.; Blanchet, P.; Barlet, A. Social Representations of Mass Timber and Prefabricated Light-Frame Wood Construction for Multi-Story Housing: The Vision of Users in Quebec. Buildings 2022, 12, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyszyn, E.; Heräjärvi, H.; Verkasalo, E.; Garcia-Jaca, J.; Araya-Letelier, G.; Lanvin, J.-D.; Bidzińska, G.; Augustyniak-Wysocka, D.; Kies, U.; Calvillo, A.; et al. The Future of Wood Construction: Opportunities and Barriers Based on Surveys in Europe and Chile. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruch, M.; Walcher, D. Timber for Future? Attitudes towards Timber Construction by Young Millennials in Austria—Marketing Implications from a Representative Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truffello, R.; Flores, M.; Garretón, M.; Ruz, G. La Importancia Del Espacio Geográfico Para Minimizar El Error de Muestras Representativas. Rev. De Geogr. Norte Gd. 2022, 81, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A. Effective Geographic Sample Size in the Presence of Spatial Autocorrelation. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 740–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz Vela, H.M. Revisando Los Métodos de Agregación de Unidades Espaciales: MAUP, Algoritmos y Un Breve Ejemplo. Estud. demogr. urbanos. 2016, 31(2), 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C.; Puig, I.; Vergara-Perucich, F.; Freed, C.; Rodríguez, B. Mapping Energy Poverty: How Much Impact Do Socioeconomic, Urban and Climatic Variables Have at a Territorial Scale? Land 2022, 11, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Aguirre, C.; Hidalgo, R. Speculation, Land Rent, and the Neoliberal City. Or Why Free Market Is Not Enough. ARQ 2019, 81, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, J.C.; Anselin, L.; Rey, S.J. The Max-p-Regions Problem. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, B.; Duque, J.C.; Ye, X. The Network-Max-P-Regions Model. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIM. Actualización GSE AIM 2023 y Manual de Aplicación; AIM: Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante; Pearson Educación, S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. The Construction of Timber Houses in Chile. A Pillar of Sustainable Development and the Agenda for Economic Recovery; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Anuario de La Edificación 2022; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Menzemer, L.W.; Vad Karsten, M.M.; Gwynne, S.; Dragsted, A.; Ronchi, E. Public Perception of Fire Safety and Risk of Timber Buildings. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viholainen, N.; Kylkilahti, E.; Autio, M.; Toppinen, A. A Home Made of Wood: Consumer Experiences of Wooden Building Materials. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, P.; Symmons, M. Overcoming Psychological Barriers to Widespread Acceptance of Mass Timber Construction in Australia. PNA309-1213; Forest & Wood Products Australia Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Terraza, H.C.; Donoso, R.; Victorero, F.; Ibanez, D. La Construcción de Viviendas En Madera En Chile: Un Pilar Para El Desarrollo Sostenible y La Agenda de Reactivación; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Dimension | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characterisation | Age | 1 ordinal variable |

| Gender | 1 categorical variable | |

| Education level | 1 ordinal variable | |

| Occupation | 1 ordinal variable | |

| Household | 3 categorical variables | |

| Tenure or occupancy regime | 1 ordinal variable | |

| Subtotal | 8 variables | |

| Perception of wooden houses | Durability | 3 categorical variables (Likert scale) |

| Fire resistance | 2 categorical variables (Likert scale) | |

| Environmental sustainability and climate impact | 4 categorical variables (Likert scale) | |

| Costs (construction and maintenance) | 2 categorical variables (Likert scale) | |

| Flexibility in construction | 3 categorical variables (Likert scale) | |

| Industrialisation potential | 3 categorical variables (Likert scale) | |

| Subtotal | 17 variables | |

| Decision variables for acquiring or constructing a wooden house | Housing types associated with timber construction | 1 categorical variable |

| Environmental actions in daily life | 1 categorical variable | |

| Factors that would encourage buying a wooden house | 1 categorical variable | |

| Perception of the reputation of the wood industry | 1 categorical variable | |

| Previous experience with timber construction | 1 categorical variable | |

| Willingness to buy a wooden house | 1 categorical variable (1 to 10 scale) | |

| Subtotal | 6 variables | |

| Other | Interest in participating in the 2nd phase of the study | 1 dichotomic variable (yes or no) |

| Contact details of interested individuals | 1 open-ended variable | |

| Subtotal | 2 variables | |

| Total | 33 variables |

| Cluster | Socio-Economic Level | Households | p-Value | Within Clusters | Heterogeneity | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | high | 48,096 | 0.95 | 1.43 | 0.87% | 33 |

| C1 | medium-high | 58,736 | 0.95 | 1.09 | 0.66% | 24 |

| C2 | medium | 58,406 | 0.95 | 1.1 | 0.67% | 25 |

| C3 | medium-low | 77,562 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.67% | 25 |

| D | low | 73,306 | 0.95 | 1.53 | 0.94% | 35 |

| E | very low | 18,800 | 0.95 | 2.36 | 1.40% | 52 |

| Cluster | Socio-Economic Level | Number of Surveys | Percent of Surveys | Households per Block | Number of Blocks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | high | 34 | 17.0% | 4 | 10 |

| C1 | medium-high | 25 | 12.5% | 3 | 10 |

| C2 | medium | 26 | 13.0% | 4 | 7 |

| C3 | medium-low | 26 | 13.0% | 4 | 7 |

| D | low | 36 | 18.0% | 4 | 10 |

| E | very low | 53 | 26.5% | 4 | 15 |

| Total | Total | 200 | 100.0% | 59 |

| Components | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| Eigenvalues | 4.17 | 1.97 | 1.42 | 1.24 | 1.07 | 1.04 |

| Percent of variance | 21.9% | 10.3% | 7.5% | 6.5% | 5.6% | 5.5% |

| Cumulative percent | 21.9% | 32.3% | 39.8% | 46.3% | 51.9% | 57.4% |

| Variables | Components | Communalities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | ||

| Reduced durability over time | 0.78 | 0.69 | |||||

| Increased exposure to insect pests | 0.67 | 0.50 | |||||

| Enhanced structural strength | −0.64 | 0.68 | |||||

| Reduced fire resistance | 0.58 | 0.51 | |||||

| Technical feasibility of mitigating fire risk | 0.60 | 0.50 | |||||

| Contributes to mitigating climate change | 0.52 | 0.60 | |||||

| Causes deforestation | 0.60 | 0.50 | |||||

| Greater thermal comfort | 0.73 | 0.57 | |||||

| Reduced acoustic comfort | −0.47 | 0.41 | |||||

| Lower construction costs | 0.60 | 0.57 | |||||

| Higher maintenance costs | −0.59 | 0.54 | |||||

| Faster construction | 0.58 | 0.60 | |||||

| Greater ease of extension to meet changing needs | 0.65 | 0.57 | |||||

| More limited architectural design possibilities | 0.70 | 0.55 | |||||

| Lower construction costs owing to prefabrication | 0.76 | 0.65 | |||||

| Reduced waste and debris during construction | 0.64 | 0.50 | |||||

| Contribution of the timber industry to national development | 0.74 | 0.62 | |||||

| Higher educational attainment | 0.78 | 0.69 | |||||

| Higher occupational status | 0.80 | 0.72 | |||||

| Clustering Method | Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) |

|---|---|

| Proximity type | Euclidean distance |

| Agglomeration method | Ward’s method |

| Number of observations | 96 |

| Input variables | C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6 2 |

| Truncation | Number of clusters = 5 |

| Clusters | Components | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical and Emerging Fears | Environmental Capital | Techno-Social Confidence | Industrial Efficiency | Fast and Inexpensive | Conditional Flexibility | |

| Distrustful Followers | 0.37 | 0.55 | −0.22 | 0.58 | −0.63 | |

| Sceptical Pragmatists | 0.47 | −0.82 | 0.87 | 0.29 | 0.54 | |

| Cautious Conservatives | 0.42 | 0.56 | −0.59 | −0.96 | 0.73 | |

| Complacent Deniers | −1.35 | −0.68 | −0.53 | −0.30 | ||

| Informed Enthusiasts | −1.28 | 0.30 | 0.46 | −0.27 | 0.17 | |

Positive perception.

Positive perception.  Negative perception.

Negative perception.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Margalet, M.; Inostroza, B.; Aguirre-Núñez, C.; Ubilla, M. Sustainability Meets Society: Public Perceptions of Energy-Efficient Timber Construction and Implications for Chile’s Decarbonisation Policies. Buildings 2025, 15, 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162921

Encinas F, Truffello R, Margalet M, Inostroza B, Aguirre-Núñez C, Ubilla M. Sustainability Meets Society: Public Perceptions of Energy-Efficient Timber Construction and Implications for Chile’s Decarbonisation Policies. Buildings. 2025; 15(16):2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162921

Chicago/Turabian StyleEncinas, Felipe, Ricardo Truffello, Macarena Margalet, Bernardita Inostroza, Carlos Aguirre-Núñez, and Mario Ubilla. 2025. "Sustainability Meets Society: Public Perceptions of Energy-Efficient Timber Construction and Implications for Chile’s Decarbonisation Policies" Buildings 15, no. 16: 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162921

APA StyleEncinas, F., Truffello, R., Margalet, M., Inostroza, B., Aguirre-Núñez, C., & Ubilla, M. (2025). Sustainability Meets Society: Public Perceptions of Energy-Efficient Timber Construction and Implications for Chile’s Decarbonisation Policies. Buildings, 15(16), 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162921