The Social Life of Residential Architecture: A Systematic Review on Identifying the Hidden Patterns Within the Spatial Configuration of Historic Houses

Abstract

1. Introduction

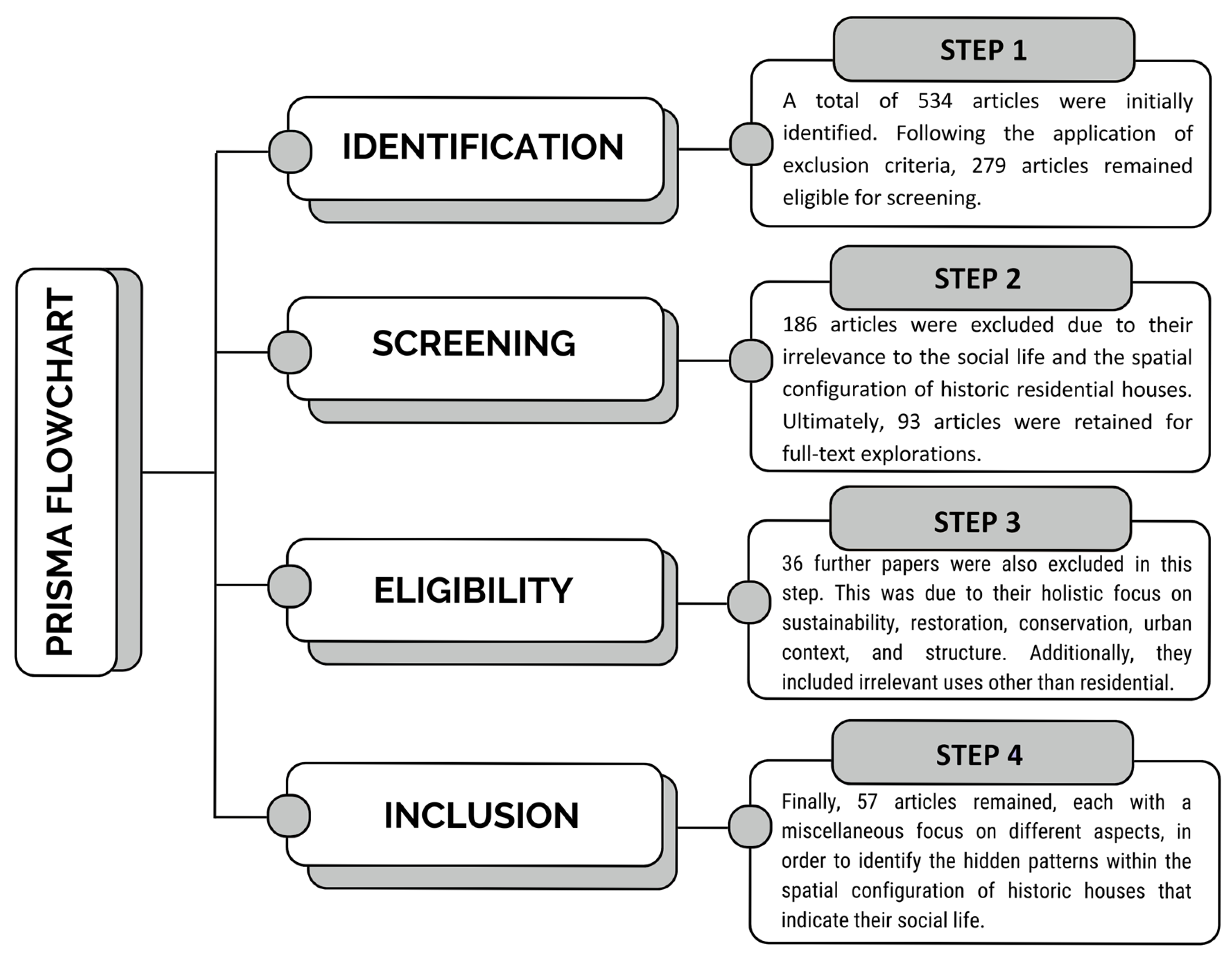

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening Process

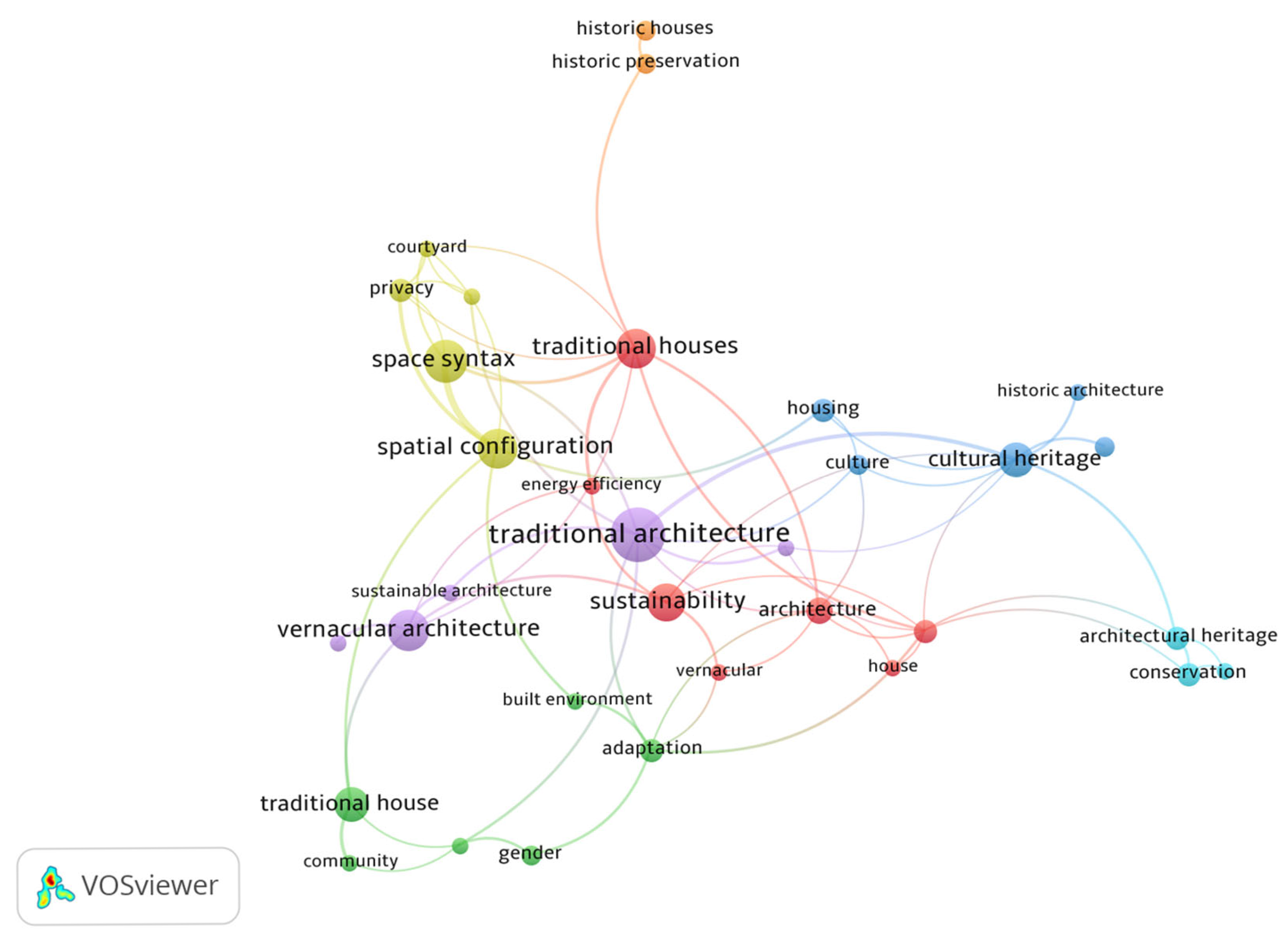

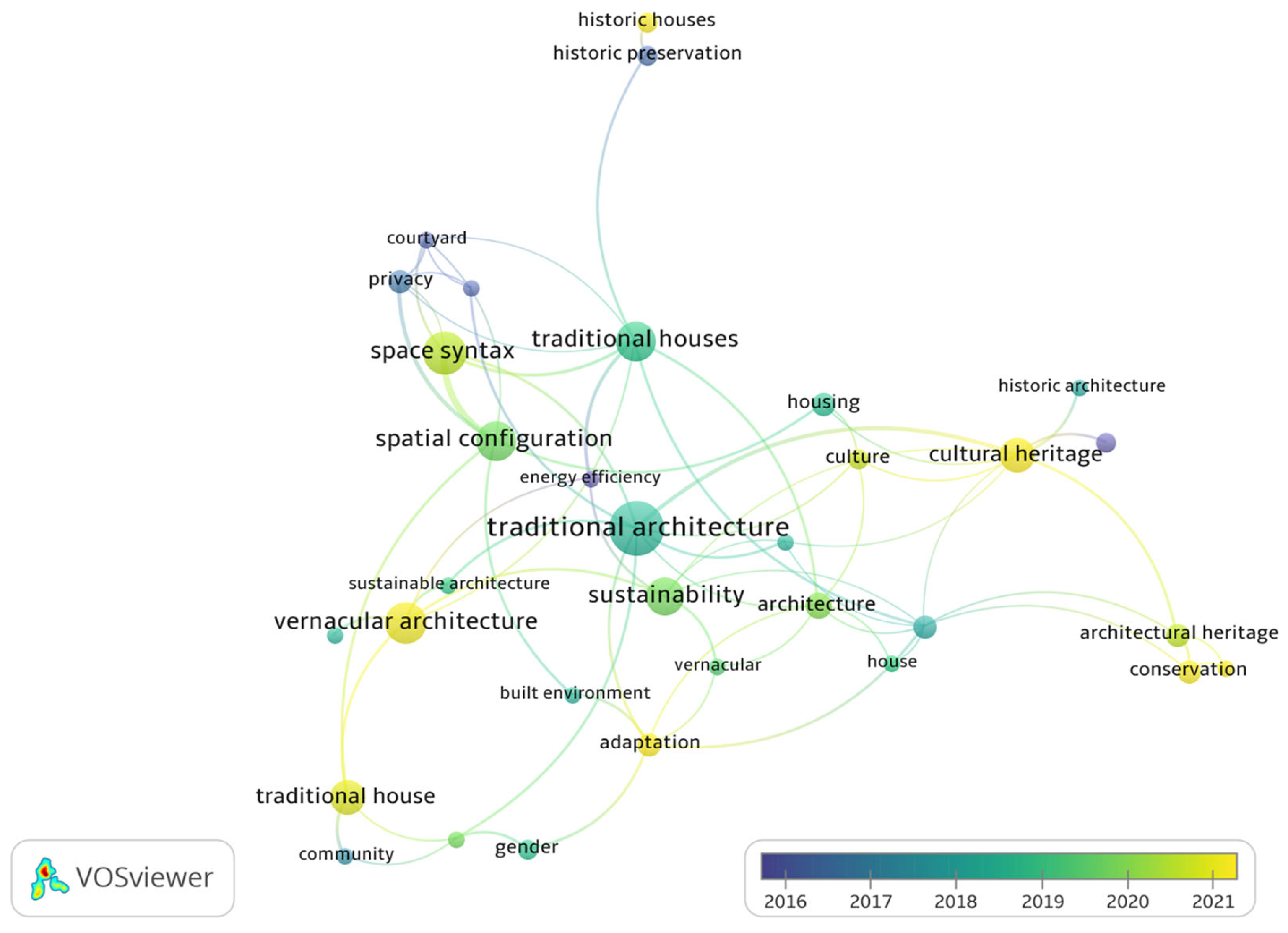

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

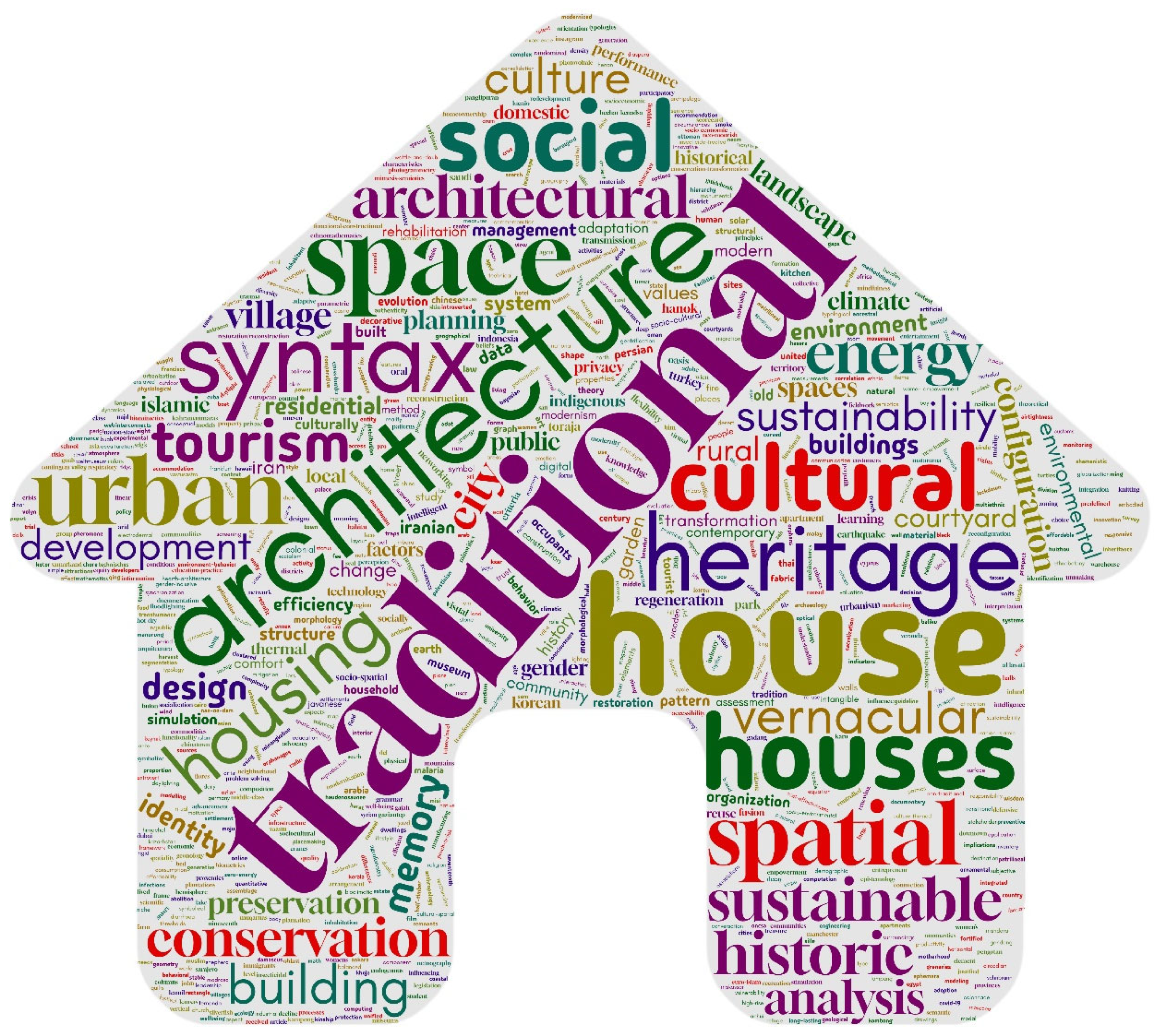

3.1. General Overview of the Findings

3.2. Critical Review on Outcomes of Prior Studies

3.2.1. Gender Roles, Privacy, and Domestic Life

3.2.2. Cultural Symbolism and Spatial Meaning

3.2.3. Space Syntax, Spatial Morphologies, and Social Structure

3.2.4. Socio-Political Dynamics and Spatial Adaptation

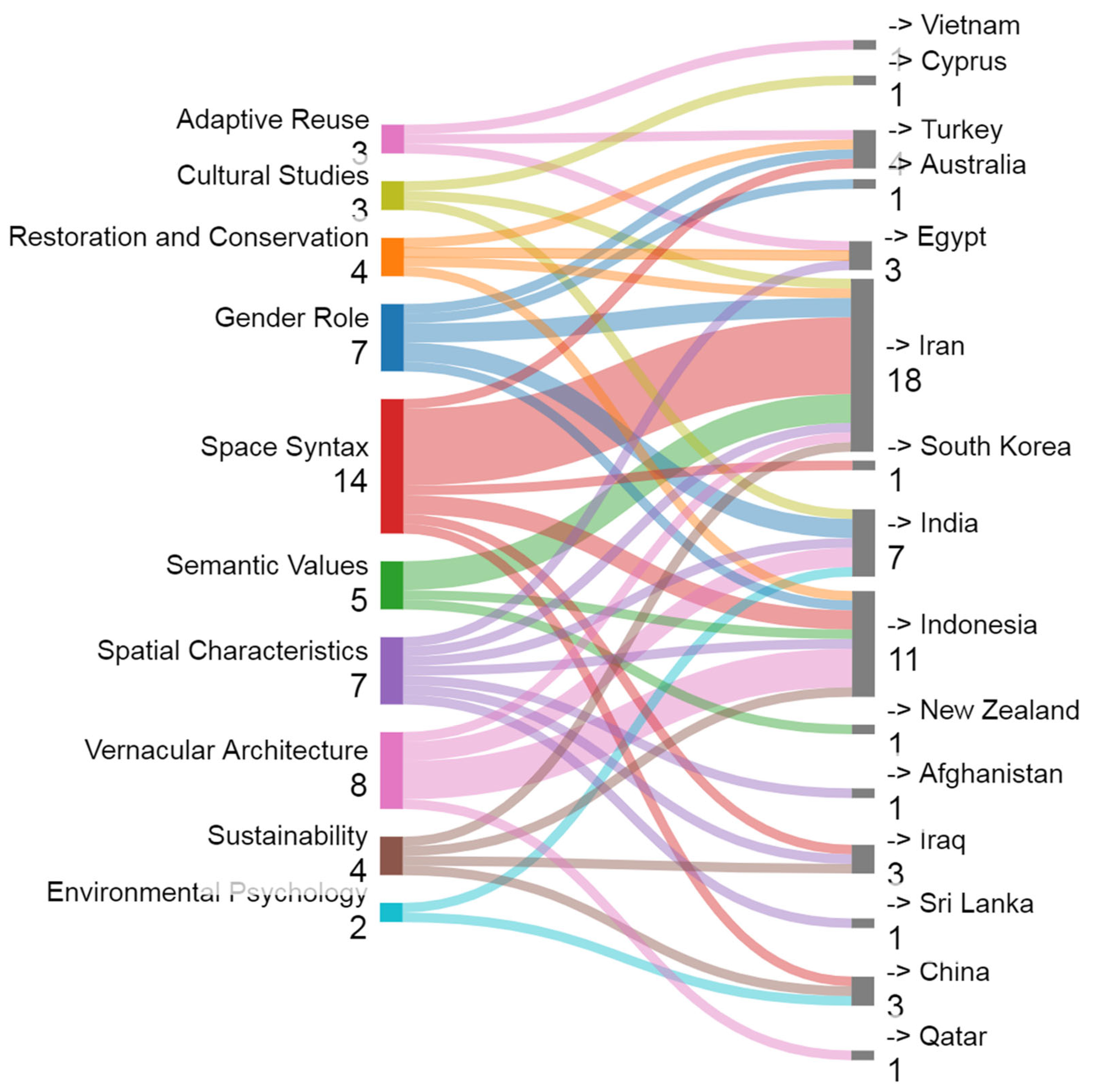

3.3. Data Synthesis and Analysis Using SankeyMATIC

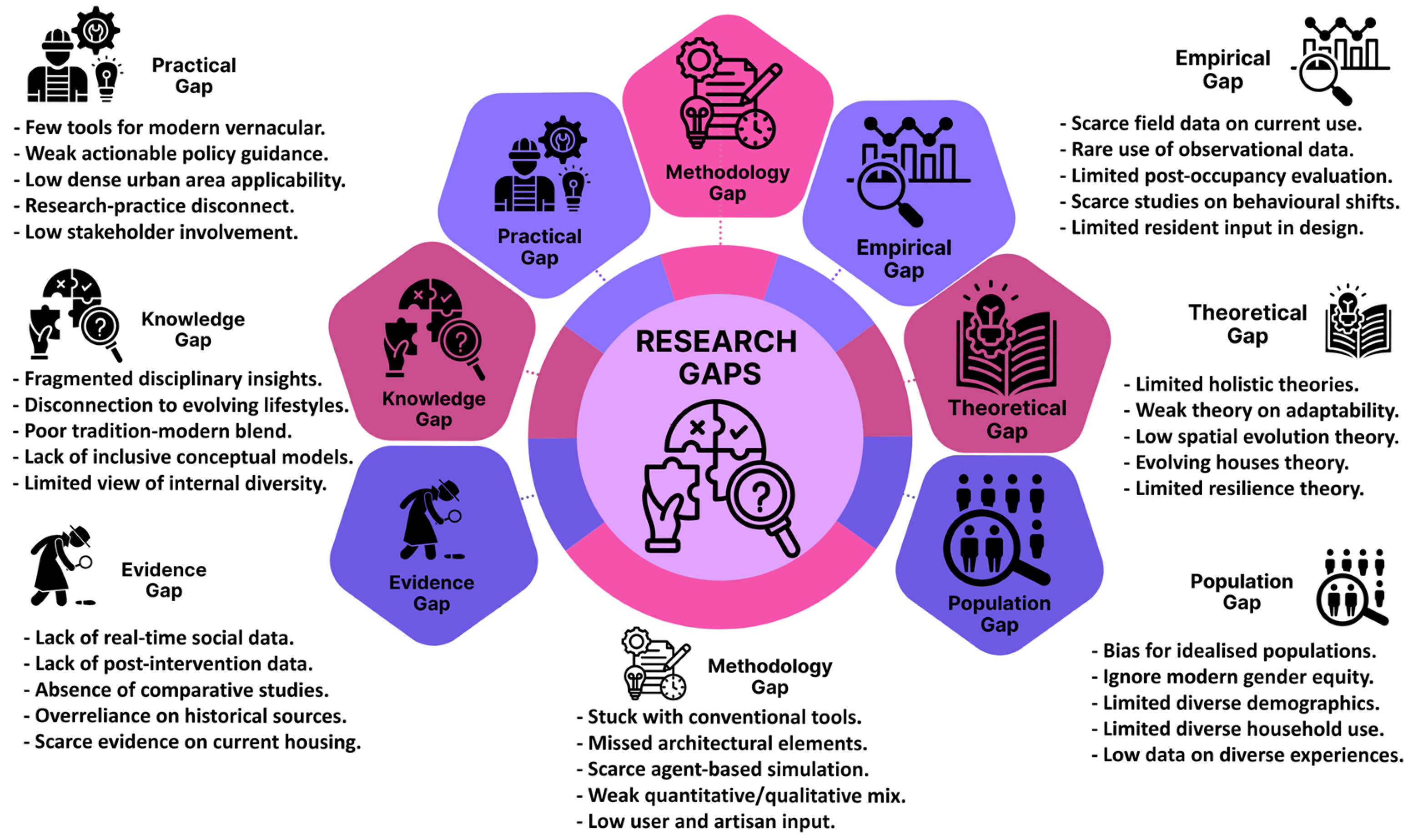

3.4. Research Gaps and Future Research Directions

3.4.1. Evidence Gap

3.4.2. Knowledge Gap

3.4.3. Practical Gap

3.4.4. Methodology Gap

3.4.5. Empirical Gap

3.4.6. Theoretical Gap

3.4.7. Population Gap

3.5. Overview of Synthesised Gaps and Study Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J. The Chinese Socio-Cultural Sustainability Approach: The Impact of Conservation Planning on Local Population and Residential Mobility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.M.; Cornadó, C.; Askarizad, R. Analyzing the Influence of Residents’ Sociocultural Reflections on the Spatial Configuration of Historical Persian Residential Architecture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qtaishat, Y.; Emmitt, S.; Adeyeye, K. Exploring the Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Old and New Housing: Two Cases from Jordan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H. The Culture of Building; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, J.F. Interpreting Historic House Museums; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B. Conservation of Historic Buildings; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J. Decoding Homes and Houses; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Akcali, S.; Ispalar Cahantimur, A. How socio-spatial aspects of urban space influence social sustainability: A case study. J. Hous. Built. Environ. 2023, 38, 2525–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, V.; Dines, N.; Gesler, W.; Curtis, S. Mingling, Observing, and Lingering: Everyday Public Spaces and Their Implications for Well-Being and Social Relations. Health Place 2008, 14, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; Rezaei Liapee, S.; Mohajer, M. The Role of Sense of Belonging to the Architectural Symbolic Elements on Promoting Social Participation in Students within Educational Settings. Space Ontol. Int. J. 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.L. Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Housing: A Conceptual Exploration. Hous. Theory Soc. 2004, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, D. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, S.F.; Tanaka, T. Analyzing the Role of Identity Elements and Features of Housing in Historical and Modern Architecture in Shaping Architectural Identity: The Case of Herat City. Architecture 2023, 3, 548–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Ji, S. A review of integrating space syntax analysis into heritage impact assessment: A comprehensive framework for sustainable historic urban development. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2024, 29, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, F.D.K. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.L.; Low, S.M. The built environment and spatial form. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1990, 19, 453–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Leaman, A.; Stansall, P.; Bedford, M. Space Syntax. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1976, 3, 147–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Tang, L.; Xi, J. Research and Application of Space-Time Behavior Maps: A Review. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2021, 20, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.F. Behavioral Mapping and Tracking. In Research Methods for Environmental Psychology; Gifford, R., Steg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Li, J. Genotype extraction of traditional dwellings using space syntax: A case study of Tibetan rural houses in Ganzi County, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ostwald, M.J.; Gu, N. A Justified Plan Graph (JPG) Grammar Approach to Identifying Spatial Design Patterns in an Architectural Style. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, S. Typal and Typological Reasoning: A Diagrammatic Practice of Architecture. J. Archit. 2015, 20, 938–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, D. Changing Building Typologies: The Typological Question and the Formal Basis of Architecture. J. Space Syntax 2014, 5, 168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Khotbehsara, E.M.; Yu, R.; Somasundaraswaran, K.; Askarizad, R.; Kolbe-Alexander, T. The Walkable Environment: A Systematic Review through the Lens of Space Syntax as an Integrated Approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.A.; Kim, S. Designing for Modern Living: The Strategic Evolution of Residential Spaces in Response to Improved Lifestyles. Teh. Glas. 2024, 18, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khozaei Ravari, F.; Hassan, A.S.; Abdul Nasir, M.H.; Mohammad Taheri, M. The development of residential spatial configuration for visual privacy in Iranian dwellings, a space syntax approach. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2024, 42, 672–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfagharkhani, M.; Ostwald, M.J. The spatial structure of Yazd courtyard houses: A space syntax analysis of the topological characteristics of the courtyard. Buildings 2021, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, Y.S.; Tahoon, D.; Abdel-Fattah, N.A.; El-Alfi, M.F. Socio-Spatial Vulnerability Assessment of Heritage Buildings through Using Space Syntax. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamelnia, H.; Hanachi, P.; Moayedi, M. Exploring the spatial structure of Toon historical town courtyard houses: Topological characteristics of the courtyard based on a configuration approach. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 14, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Valladares, O.P.; Peña, D.M. Sustainability Performance by Ten Representative Intelligent Façade Technologies: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.; Ioannidis, J.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual; Univeristeit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Nagy, G.J.; Setti, A.F.F.; Sharifi, A.; Donkor, F.K.; Batista, K.; Djekic, I. Handling the impacts of climate change on soil biodiversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; Daudén, P.J.L.; Garau, C. The Application of Space Syntax to Enhance Sociability in Public Urban Spaces: A Systematic Review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastoum, M.; Guevara, C.S.; Arranz, B. Efficient daylighting and thermal performance through tessellation of geometric patterns in building façade: A systematic review. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 83, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewi, H. Kitchen Tours: Re-Interpreting the History of Gendered Labour and Technologies in the Home Through Four Australian Heritage Houses. Fabrications 2023, 33, 432–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhada, S.K.; Lukito, Y.N. The Dynamics of Kitchen Adaptation Based on the Cultural Spatial System in Minangkabau West Sumatra. Evergreen 2022, 9, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhun, D. The relationship between space and gender in traditional homes across Turkey. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2010, 27, 340–355. [Google Scholar]

- Trapeznik, A. Dismissing the staff: Domestic servants and a historic house in Dunedin, New Zealand. J. N. Z. Stud. 2022, 34, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughianzadeh, M. Gender Structure and Spatial Organization: Iranian Traditional Spaces. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohannadi, A.S.; Furlan, R. The syntax of the Qatari traditional house: Privacy, gender segregation and hospitality constructing Qatar architectural identity. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazidizaji, S.; Safari, H. The social logic of Persian houses, in search of the introverted houses genotype. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 26, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asriana, N.; Khidmat, R.P.; Jaya, M.A.; Ujung, V.A.; Satria, W.D.; Andriani, R. Syntactic analysis of traditional houses in urban kampung. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asriana, N.; Khidmat, R.P. Decoding spatial layout patterns of traditional houses in urban kampung settlements. J. Archit. Urban. 2024, 48, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, N.; Dongre, A. Analysing social relevance of spatial organisation: A case study of traditional Pol houses, Ahmedabad, India. Asian Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejadriahi, H.; Dincyurek, O. Identifying privacy concerns on the formation of courtyards. Open House Int. 2015, 40, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkarnain, A.S.; Hamzah, B.; Wikantari, R.; Sir, M.M. Meanings of Spatial Order in the Customary House of Sapo Battoa Kaluppini in the Enrekang Regency, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. ISVS E-J. 2022, 9, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tarigan, R.; Antariksa, A.; Salura, P. Reconstructing the Understanding of the Symbolic Meaning Behind the Architecture of Javanese Traditional House. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bura, P.P.; Ando, T. Study on the settlements composition of Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja in Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 1826–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryani, N.P.; Wijaya, I.K.M. Comparison of Residential Patterns and Influence Analysis of Cultural, Economic and Social Aspects on the Dualism of Residential Patterns in Pengotan Traditional Village, Bangli, Bali. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 13, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.Y.; Lim, E.J. Landscape Characteristics of the Nae-oe-dam (wall) of Traditional Houses in Gyeongsangnam-do. J. People Plants Environ. 2024, 27, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S. The Courtyard in Cairene Traditional Houses; A Territorial Dispute, Game of Spaces Geometry and Light. J. Islam. Archit. 2022, 7, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebara, T.M. Private open space as a reflection of culture: The example of traditional courtyard houses in Nigeria. Open House Int. 2022, 48, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, A.L.; Chithra, K. Decoding Namboothiri illams of Kerala: A shape grammar approach. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 52, 841–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaivani, P.; Pongomathi, S.; Priya, R.S. A study of transition spaces in traditional houses of Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2023, 22, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, B.; Junaidi, M.A.; Ariadi, L.M. Authenticity of traditional houses, Islam and cultural tourism products and services. Ulumuna 2023, 27, 467–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraty, H.J.S.; Raschid, M.Y.M.; Yunos, M.Y.M. Morphology of Islamic Traditional Iraqi Courtyard House Toward Holistic Islamic Approach in New Residential Development in Iraq. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Atak, Ö.; Çağdaş, G. The reflection of religious diversity and socio-cultural meaning on the spatial configuration of Traditional Kayseri Houses. A|Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2015, 12, 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ozyilmaz, H.; Aluclu, I.; Akin, C.T. The Social and Spatial Reflections of Culinary Culture on Traditional Diyarbakir Houses. Milli Folk. 2014, 102, 138–153. [Google Scholar]

- Pulhan, H.; Numan, I. The transitional space in the traditional urban settlement of Cyprus. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2005, 22, 160–178. [Google Scholar]

- Foruzanmehr, A. People’s perception of the loggia: A vernacular passive cooling system in Iranian architecture. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 19, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqadam, S.; Nubani, L. From house to home: Exploring the spatial expression of social identity on traditional Shiraz houses. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2024, 18, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessari, P.; Chegeni, F. Measuring the relationship between spatial configuration concept variables and flexibility components. J. Archit. Urban. 2022, 46, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessari, P.; Chegeni, F. The impact of environmental construction on the spatial configuration of traditional Iranian housing (case study: Comparison of Dezful and Boroujerd traditional housing). J. Archit. Urban. 2021, 45, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chai, X.; Jiang, R.; Chen, Y. Quantitative comparison of space syntax in regional characteristics of rural architecture: A study of traditional rural houses in Jinhua and Quzhou, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.F.; Sadiq, C.J.; Farhan, R.F. Space performance assessment of traditional houses in Akre. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; He, J. Gender Equality of Privacy Protection in the Use of Urban Furniture in the Muslim Context of Iran. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1311–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçen, D.; Özbayraktar, M. Integrating space syntax and system dynamics for understanding and managing change in rural housing morphology: A case study of traditional village houses in Düzce, Türkiye. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, S.A.B.; Maraschin, C. Built heritage and urban spatial configuration: The case of Herat, Afghanistan. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 2101–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ma, S. Comparative analysis of habitation behavioral patterns in spatial configuration of traditional houses in Anhui, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang provinces of China. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian, G.; Sadoughi, A. Application of access graphs and home culture: Examining factors relative to climate and privacy in Iranian houses. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 6350–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Nagendra, N. House form of Porbandar. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolani, B.; Boccagni, P. Two houses, one family, and the battlefield of home: A housing story of home unmaking in rural Punjab. Geoforum 2021, 127, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprapti, A.; Sejati, A.W.; Pandelaki, E.E.; Sardjono, A.B. Archiving traditional houses through digital social mapping: An innovation approach for living heritage conservation in Java. J. Archit. Urban. 2022, 46, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Song, S.; Feng, K. The Sustainability Cycle of Historic Houses and Cultural Memory: Controversy between Historic Preservation and Heritage Conservation. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, R.M.; Aksulu, B.I. Reasons and Results of Social and Physical Changes in Traditional Mosul Houses Between 2014-2023. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formolly, A.; Saraei, M.H. Socio-cultural transformations in modernity and household patterns: A study on local traditions housing and the impact and evolution of vernacular architecture in Yazd, Iran. City Territ. Archit. 2024, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.; Pernice, R. Modernism in Sri Lanka: A comparative study of outdoor transitional spaces in selected traditional and modernist houses in the early post-independence period (1948–1970). J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 1791–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti, M.; Norouzian-Maleki, S. Spatial reconfiguration of Iranian traditional houses to explore effective strategies of flexibility using space syntax analysis. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2025, 40, 65–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itma, M.; Khaleefa, T. Affordable housing design in response to sociocultural context. A comparative study in Koya City. Local Dev. Soc. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-González, C.; Ruiz-Jaramillo, J.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Joyanes-Díaz, M.D.; Montiel Vega, L.; Cano-Martos, V.; Navas-Martín, M.Á. Natural lighting in historic houses during times of pandemic. The case of housing in the Mediterranean climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erman, O.; Kasapbasi, E. Monitoring the Changes of Spatial Configuration of Gaziantep Urban Housing Through the Samples of 1960-1980 Period. ART-SANAT 2020, 14, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosanlı, D.A. Housing in transition: The first apartments of the New capital city, Ankara. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, P.P.; Giao, P.N.Q.; Gyu, O.S. Spatial configuration of traditional houses and apartment unit plans in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: A comparative study. Spatium 2021, 45, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günçe, K.; Ertürk, Z.; Ertürk, S. Questioning the “prototype dwellings” in the framework of Cyprus traditional architecture. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayed, N.N.; Türker, Ö.O. Comparative Compatibility Assessment on Reused Iranian Houses from Qajar Era. Arquit. Rev. 2021, 17, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasurya, V.R.; Hardiman, G.; Sari, S.R. The Influence of Social Change on the Transformation Process of Traditional Houses in Brayut Village. ISVS e-J. 2019, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- AlSadaty, A. Historic houses as pillars of memory: Cases from Cairo, Egypt. Open House Int. 2018, 43, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Jiaanbieyuan new courtyard-garden housing in Suzhou: Residents’ experiences of the redevelopment. J. Chin. Archit. Urban. 2019, 1, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Turan, G. Sustainable development in historic areas: Adaptive re-use challenges in traditional houses in Sanliurfa, Turkey. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.A.M. Impact of Social Rules on Creating a Liveable Space the Case of El-Fawakhria Traditional Quarter-Al-Arish-Egypt. Open House Int. 2007, 32, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Luna, R.D.; Alvarez, J.; Stevens, E. Collectivism and individualism in Latino recovery homes. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse 2018, 17, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotbehsara, E.M.; Somasundaraswaran, K.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Yu, R. The influence of spatial configuration on pedestrian movement behaviour in commercial streets of low-density cities. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shershneva-Zastavnaia, J.; Fernández-Aragón, I.; Piasek, G. Urban regeneration in vulnerable neighborhoods: Tensions between the physical and the social dimensions in the case of Otxarkoaga, Bilbao (Spain). Ciudad Y Territorio Estudios Territoriales 2024, 56, 919–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasek, G.; Garcia-Almirall, P. Vulnerable Neighbourhoods, Disaffiliated Populations? A Comprehensive Index of Social Capital and Social Infrastructure in Barcelona. Buildings 2023, 13, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, P.G.; Cornadó, C.; Piasek, G.; Grau, S.V. Review of socio-residential vulnerability identification methodologies. Application to the cities of Bilbao and Barcelona. VITRUVIO-Int. J. Archit. Technol. Sustain. 2023, 8, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vima-Grau, S.; Cornadó, C.; Garcia-Almirall, P. Socio-spatial analysis of the vulnerable urban fabric in the city of Barcelona. VITRUVIO-Int. J. Archit. Technol. Sustain. 2019, 4, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vima-Grau, S.; Cornadó, C.; Ravetllat, P.-J.; Garcia-Almirall, P. Multiscale Integral Assessment of Habitability in the Case of El Raval in Barcelona. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bishawi, M.; Ghadban, S.; Jørgensen, K. Women’s behaviour in public spaces and the influence of privacy as a cultural value: The case of Nablus, Palestine. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1559–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; He, J. The role of urban furniture in promoting gender equality and static social activities in public spaces. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.; Sebar, B.; Whitehead, D.; Hatam, N.; Coyne, E.; Harris, N. Young Iranian women as agents of social change: A qualitative study. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2020, 79, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Kundt, R. The evolution of human ritual behavior as a cooperative signaling platform. Relig. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott, P.; Keys, C. Redefining architecture to accommodate cultural difference: Designing for cultural sustainability. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2015, 58, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; He, J.; Dastoum, M. Gender disparity in public spaces of Iran: Design for more inclusive cities. Cities 2025, 158, 105651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Martínez, J.; Gutiérrez-Mozo, M.-E.; Gilsanz-Díaz, A. Inclusive Higher Education and the Built Environment. A Research and Teaching Agenda for Gender Mainstreaming in Architecture Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, R.; Anbu, M.; Noguchi, M. Analysis of Design Agents for Mediation of Gender Inclusivity in Domestic Space: A Case Study of Chettinad Vernacular Architecture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Gaps | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Evidence Gap | An evidence gap refers to a lack of sufficient or contextually appropriate data, empirical support, or documented outcomes necessary to substantiate the claims, theories, or recommendations presented in the literature. |

| Knowledge Gap | A knowledge gap refers to a lack of understanding, clarity, or established science in a particular domain, topic, or relationship. |

| Practical Gap | A practical gap refers to the disconnect between theoretical knowledge and its pragmatic application. |

| Methodology Gap | A methodology gap refers to inadequacies, limitations, or outdated procedures in the research approaches employed within a field of study. |

| Empirical Gap | An empirical gap refers to the absence or insufficiency of first-hand, observation-based, or measurable data to support theoretical claims or hypotheses. |

| Theoretical Gap | A theoretical gap refers to the absence, underdeveloped, or fragmentation of conceptual frameworks that explain observed phenomena in a coherent, systematic, and generalisable manner. |

| Population Gap | A population gap refers to the limitations in the scope, diversity, or representativeness of the populations studied in a given research field. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moosavi, S.M.; Cornadó, C.; Askarizad, R.; Garau, C. The Social Life of Residential Architecture: A Systematic Review on Identifying the Hidden Patterns Within the Spatial Configuration of Historic Houses. Buildings 2025, 15, 2120. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122120

Moosavi SM, Cornadó C, Askarizad R, Garau C. The Social Life of Residential Architecture: A Systematic Review on Identifying the Hidden Patterns Within the Spatial Configuration of Historic Houses. Buildings. 2025; 15(12):2120. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122120

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoosavi, Seyedeh Maryam, Còssima Cornadó, Reza Askarizad, and Chiara Garau. 2025. "The Social Life of Residential Architecture: A Systematic Review on Identifying the Hidden Patterns Within the Spatial Configuration of Historic Houses" Buildings 15, no. 12: 2120. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122120

APA StyleMoosavi, S. M., Cornadó, C., Askarizad, R., & Garau, C. (2025). The Social Life of Residential Architecture: A Systematic Review on Identifying the Hidden Patterns Within the Spatial Configuration of Historic Houses. Buildings, 15(12), 2120. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15122120