Abstract

Vernacular architecture is a complex and living heritage type, and the study of the evolution laws of its spatial form is of great value to the conservation of architectural heritage diversity. Taking vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area as the research object, based on the theory of spatial syntax, 30 building samples were subjected to global and local calculations of MD, IRRA, and NACH values, while the common characteristics among the samples were obtained by using Kendall’s W test, and the individual characteristics among the samples were obtained by using differentiation analysis. The results show that: (a) vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area exhibits characteristics of multi-cluster branched centrality and spatial hierarchical layout; (b) these architectures possess four categories of inheritance factors: the privacy of granary spaces, the centrality of corridor spaces, the passability of breeding areas, and the independence of scripture hall spaces; (c) these architectures possess three categories of differentiation factors: the functional evolution of traditional spaces, the spatial reconstruction of breeding areas, and the “Toilet Revolution” driven by multiple forces. This study elucidates the regulatory role of cultural continuity in shaping the spatial forms of vernacular architecture, providing new evidence for analyzing the formation mechanisms of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area.

1. Introduction

Architectural heritage is a product of human civilization history. It transcends temporal and spatial limitations through its material existence, showcasing the trajectory of human development, while its constituent elements evoke visitors’ historical identity and value cognition. Nowadays, the inheritance and protection of architectural heritage have been paid attention to by governments and international organizations for the following reasons: (a) protecting architectural heritage helps explore the connections among regions, nations, and societies; (b) inheriting and redesigning architectural heritage contributes to the sustainable development of cultural characteristics in both rural and urban areas [1,2,3,4,5]. As a complex and living heritage type, the evolution of vernacular architecture involves both endogenous natural transition and exogenous social intervention. The “space” is the objective self-existing object used by human beings in the vernacular architecture. It has distinct self-characteristics, and its morphological features can reflect the social activity trajectory of the residents.

Currently, the research on vernacular architecture can be broadly divided into several themes: challenges and opportunities in the new era [6,7,8,9,10], sustainable protection and utilization [11,12,13,14,15], value perception and habitat analysis [16,17,18], architectural performance and construction techniques [19,20,21], and architectural form evolution and renewal [22,23,24]. Among them, the evolution and development of ethnic minorities’ vernacular architecture are relatively slow, and the cultural and geographical backgrounds are diversified, so it is necessary to combine multiple perspectives, disciplines, and methods when researching them. The core of spatial syntax theory is to elaborate the relationship between space and society. A study applying this theory to the Xiangxi region of China compared ethnic differences in vernacular architecture’s internal spatial configurations. It revealed correlations between the spatial effects of Han cultural diffusion patterns and the spatial differentiation of each ethnic group’s architectural layouts [25]. Zhe Lei takes the local customs and vernacular architecture of the Tibetan ethnic group in Ganzi, Sichuan Province of China, as the object of his study, and adopts JPG (Justified Plan Graph) as a method to study the cultural background and spatial genotypes of the vernacular architecture [26], and some scholars have also used this method to study the vernacular architecture in Huizhou, China [27]. In addition, Gokcen and Dilara combined spatial syntactic analysis and system dynamics analysis to focus on the relationship between rural vernacular architecture and social evolution in Turkey [28]. Polish housing is mainly single-family houses and apartments, and through psychosocial and spatial syntactic analyses, they compared the differences in spatial participation of single-family houses and apartments and found that single-family house dwellers are more emotionally invested in their families [29]. In addition, other scholars have examined the “genotype” of Neruda’s “Micoac” house based on the morphological context of spatial syntax, which is the center of Neruda’s political and cultural activities [30]. In conclusion, the study on vernacular architecture based on spatial syntax is distributed across different countries and ethnic groups. However, at present, few scholars have applied the theory of spatial syntax to the study of vernacular architecture in the Tibetan areas of Yunnan Province, China. It is located in the southwest of the country where the three major cultural plates of China extend, collide, and blend, and its social culture and folk history are of great value for research.

At present, academics generally divide the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area into two architectural types, “Shan pian house” and “Tu zhang house”, combined with the natural and humanistic background of the depth of analysis of its architectural structure [31]. Other scholars examine aspects such as the spatial culture, architectural paintings, and small woodwork types to discuss the protection and inheritance of the proposal to vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area [32,33,34]. In addition, Zhi Li also paid attention to building techniques, standardized construction, and fire prevention design for the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area [35]. In the comparative study of the spatial schema of the vernacular architecture, Jun Shan found that the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area embodies the unidirectional “de-centering” design [36]. Other studies also involve the extraction of traditional factors in vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area [37] but did not study the inheritance factors and differentiation factors of the spatial configuration of the vernacular architecture. Moreover, the above studies lacked the quantitative analysis and qualitative interpretation of the spatial configuration of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area and did not comprehensively analyze the effects of the survival of national culture and the promotion of social policies on the spatial configuration of the vernacular architecture, which made it difficult to reveal the social logic of the spatial forms of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area.

Based on this, the purpose of this study is: (a) to organize and summarize the atlas of architectural floor plans of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area to provide data support for the protection of local architectural heritage; (b) to identify the inheritance and differentiation factors in the vernacular architecture space through quantitative analysis of the spatial configuration relationship of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area; and (c) to associate the formation of inheritance and differentiation factors in the spatial forms of vernacular architecture with the development of national culture and social patterns, explore the role of cultural survival on the spatial forms of vernacular architecture, and provide new arguments for analyzing the formation mechanism of vernacular architecture culture in the Yunnan–Tibet area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Objects

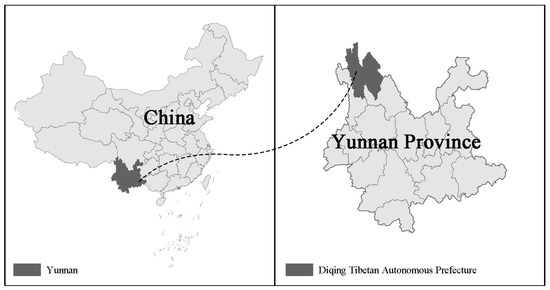

The Yunnan–Tibet area refers to the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (Figure 1), located in the northwestern part of Yunnan Province, which is an alpine region with a vertically distributed climate of cold, warm, and hot. In the doctrine of “ethnic corridor”, the Yunnan–Tibet area is located in the “Tibet-Yi corridor”, which is the main spatial corridor for ethnic migration, exchange, and integration. Since the Tubo moved southward into northwestern Yunnan Province, the Tibetan and local Qiang cultures have gradually integrated. Under the background of the great unification in successive dynasties, the Yunnan–Tibet area has changed its lords several times, and the multi-ethnic cultures have accumulated and stacked up. Then, it was infiltrated by the Naxi culture as well as the Huaxia culture under the role of the Tusi system in the Ming and Qing Dynasties [38]. As one of the main Tibetan settlement areas in China, under the influence of multi-ethnic culture, the local Tibetan compatriots constructed wood-framed buildings according to local conditions, showing distinctive indigenous characteristics (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the Yunnan–Tibet area.

Figure 2.

Real pictures of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area.

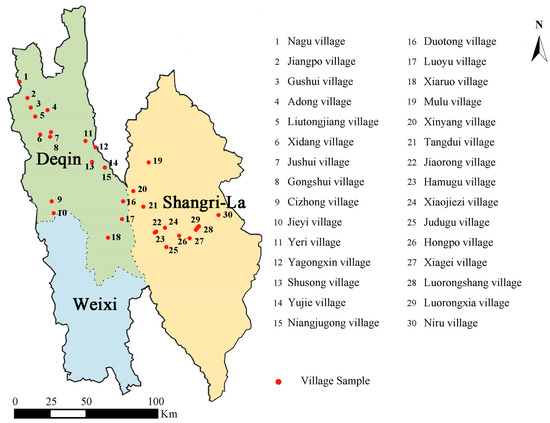

The architectural samples used in this study are derived from field investigations over the past decade, and the construction time of all samples ranged from 25 to 35 years. The specific scope is shown in Figure 3. Among them, the main ethnic group in Weixi County is the Lisu, so no samples were taken. The team conducted field investigations in the Yunnan–Tibet region over the past decade. During the investigation process, they were divided into several groups. Group A used cameras and mobile phones to record the appearance, structure, and internal space of the building. Group B used tape measures and laser rangefinders to obtain data on the building’s plan, elevation, and section. Group C sorted out the data obtained by Group A and Group B and drew them using drawing software such as AutoCAD 2018 and SketchUp 2022. After grouping, sampling is conducted first based on the usability of the buildings. The usability is judged by whether there are long-term residents and whether the appearance of the buildings is intact. Secondly, efforts should be made to ensure the integrity of data acquisition and accurately measure the data of building plans, elevations, and sections. Thirty building samples of this study were selected based on usability and the integrity of data acquisition.

Figure 3.

Scope of access to vernacular architecture samples.

The internal functional spaces of the vernacular architecture are divided into production spaces, which are mainly the breeding area, woodshed, granary, and ShaiTai (it refers to an open-air platform built on the roof for spreading out and drying crops); living spaces, which are mainly the bedroom, kitchen, toilet, storage room, and TangWu; transportation spaces, which are mainly the staircase, corridor, entrance hall, courtyard, and patio; and the spiritual space, the scripture hall. The samples are now categorized into three types according to the combination relationship between the main building, courtyard, and patio in the plan dimension: main building type, building courtyard combination type, and patio courtyard compound type.

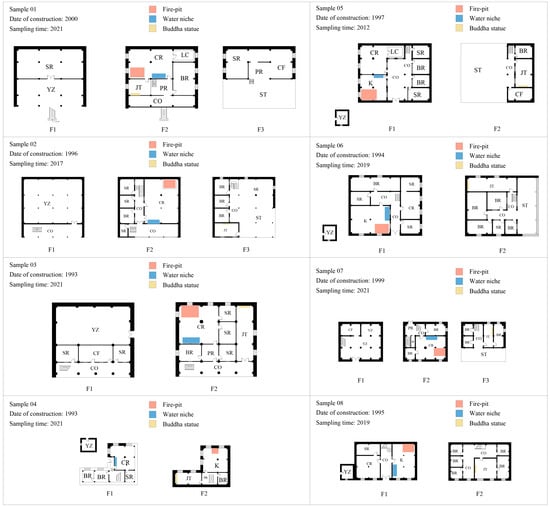

2.1.1. Main Building Type

This type is presented as a single main building, with a rectangular and “L-shaped” floor plan. With the corridor space as the center, the rest of the functional space is distributed in the front and back or left and right (Figure 4). The indoor breeding area space is located on the first floor and connected to the storage room and woodshed, and the rest of the functional spaces are located on the second and third floors; in the sample of residential houses without indoor breeding area space, the TangWu is mostly located on the first floor, the scripture hall and the ShaiTai are located on the second and third floors, and the rest of the functional spaces are distributed on the upper and lower floors.

Figure 4.

Main building type architectural floor plan atlas. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

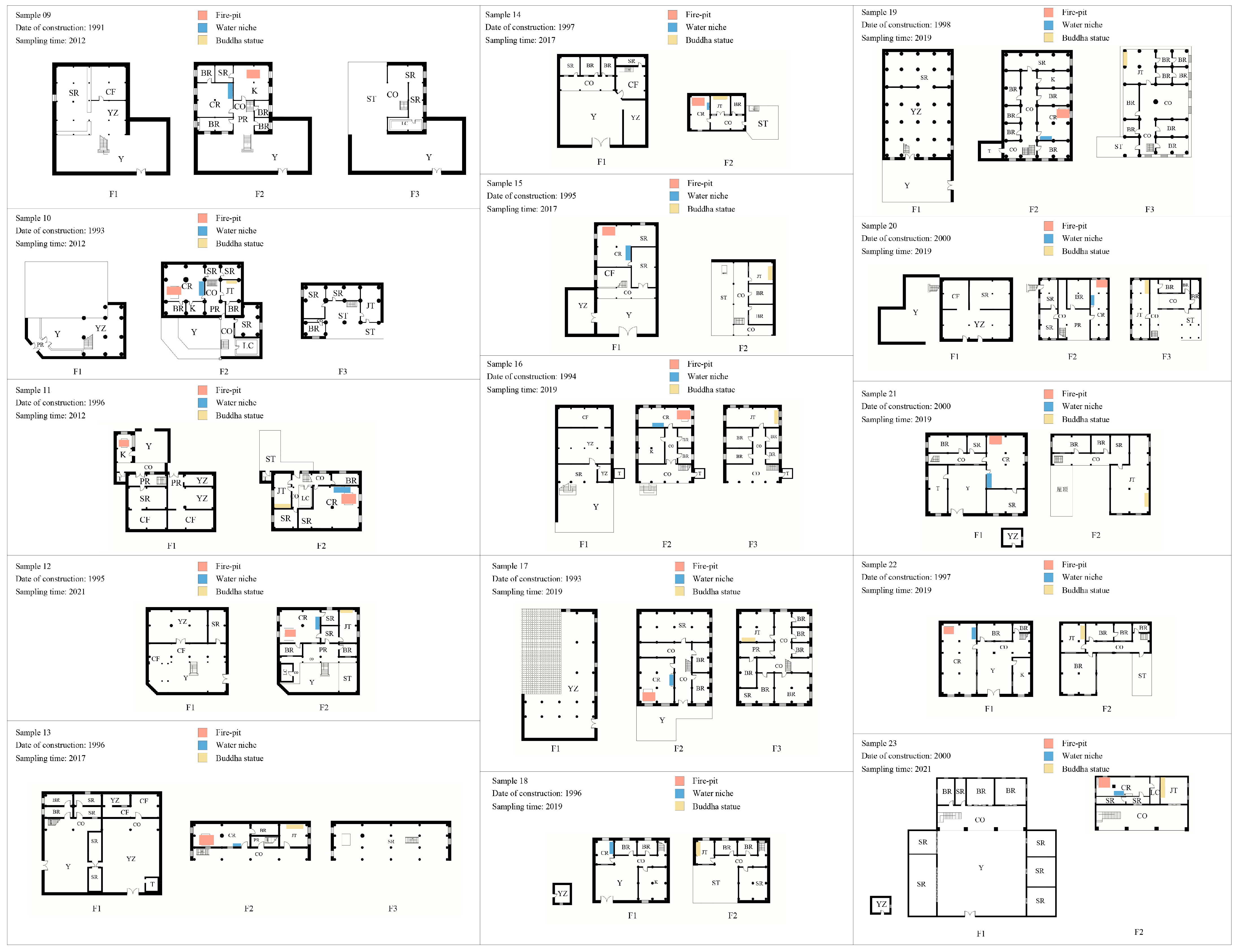

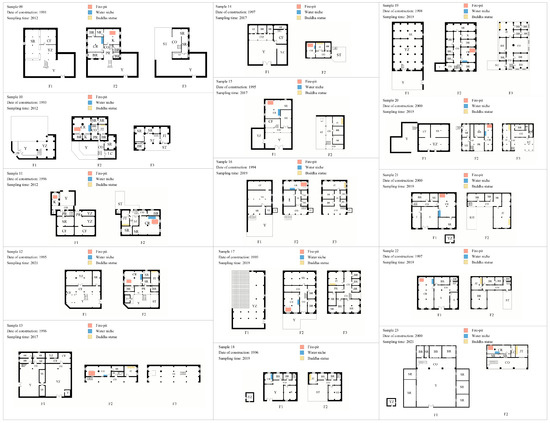

2.1.2. Building Courtyard Combination Type

This type is a combination of the main building and the courtyard, with the main building as the foundation. It can be further divided into courtyard external and courtyard embedded types. In terms of the planar form, the characteristics of this type of building are L-shaped, U-shaped, four-corner-shaped, inverted U-shaped, and irregular shapes (Figure 5). The entrance hall and corridor are the center, and the rest of the functional spaces are distributed around. A few of them are distributed in a left-right or front-back manner. The characteristics of vertical distribution of functional spaces are roughly the same as those of the main building type, with the difference that there is a connection between the breeding area on the first floor and the courtyards, and that the functional spaces of this type are distributed in a more complex way with a larger building volume.

Figure 5.

Building courtyard combination type architectural floor plan atlas. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

2.1.3. Patio Courtyard Compound Type

In this type, a patio is opened inside the main building to give it a “hui” shape, and on the basis of this, a courtyard is attached to it, giving it an overall “L” or irregular shape (Figure 6). Like the previous two types, the production space is located on the first floor, while the living space and spiritual space are located on the second and third floors. Unlike the previous two types, however, all functional spaces are distributed around the patio.

Figure 6.

Patio courtyard compound type architectural floor plan atlas. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

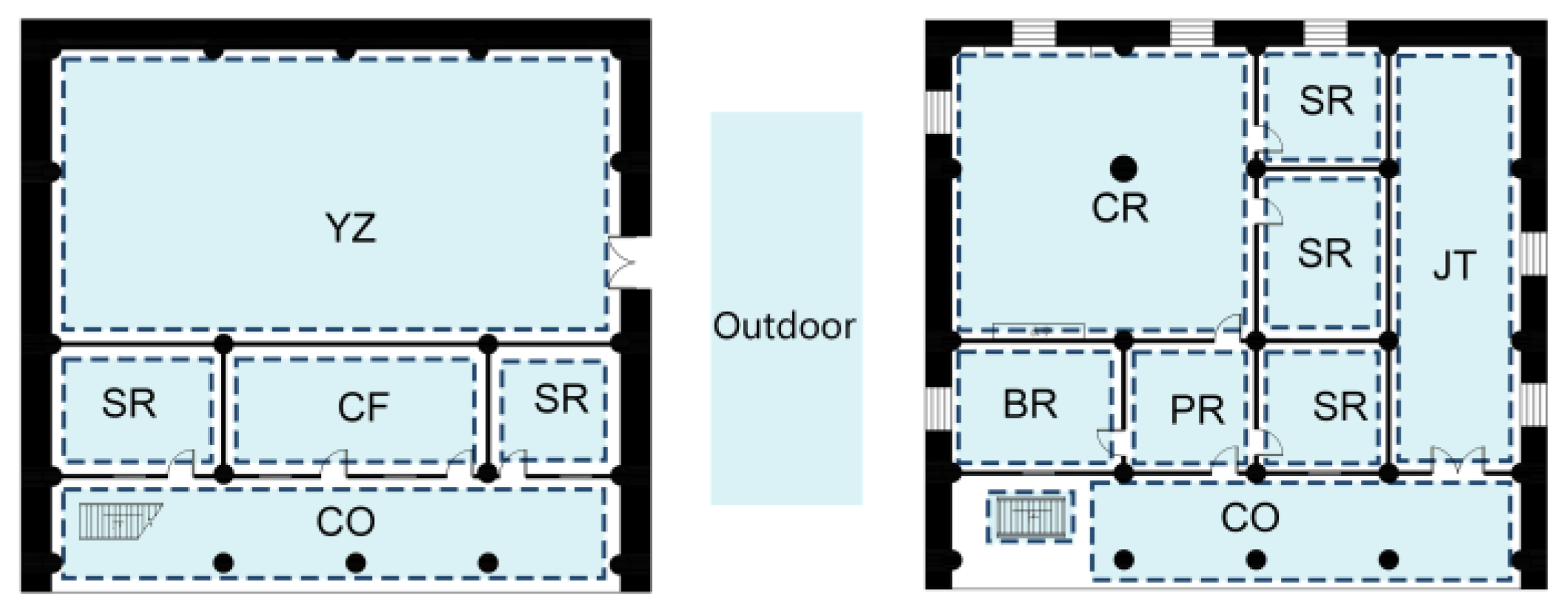

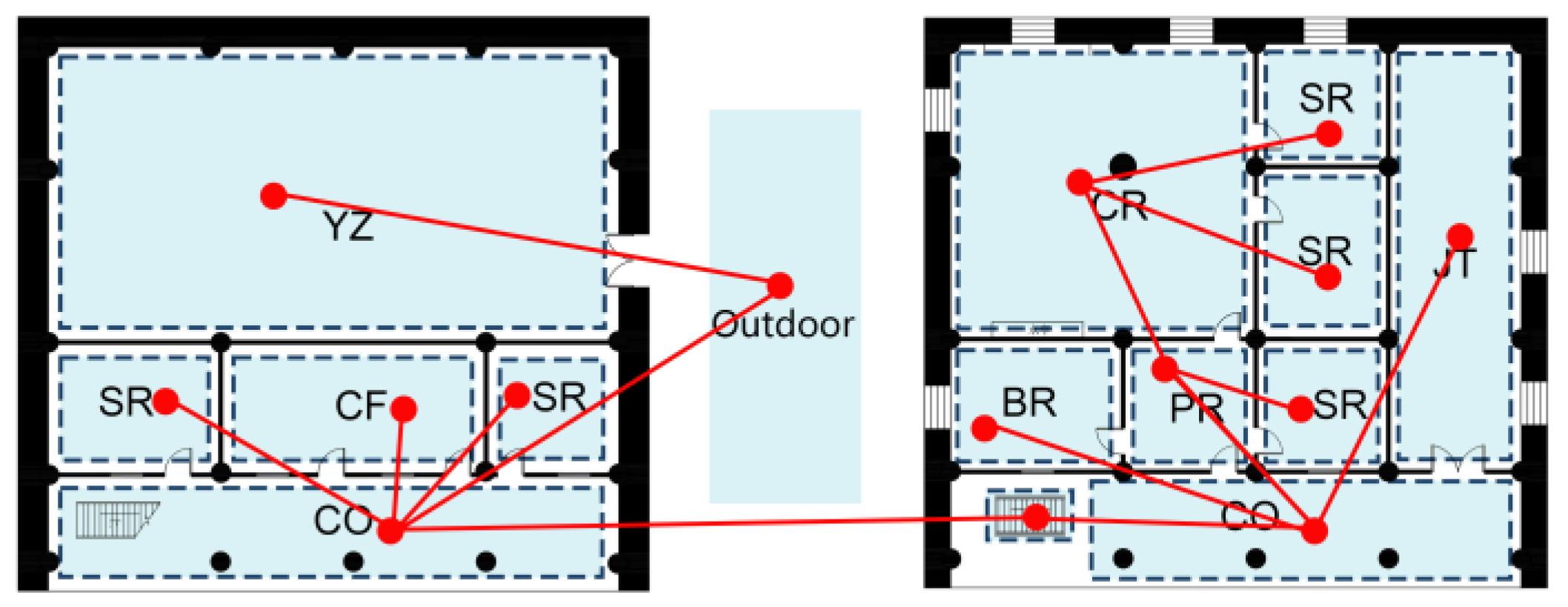

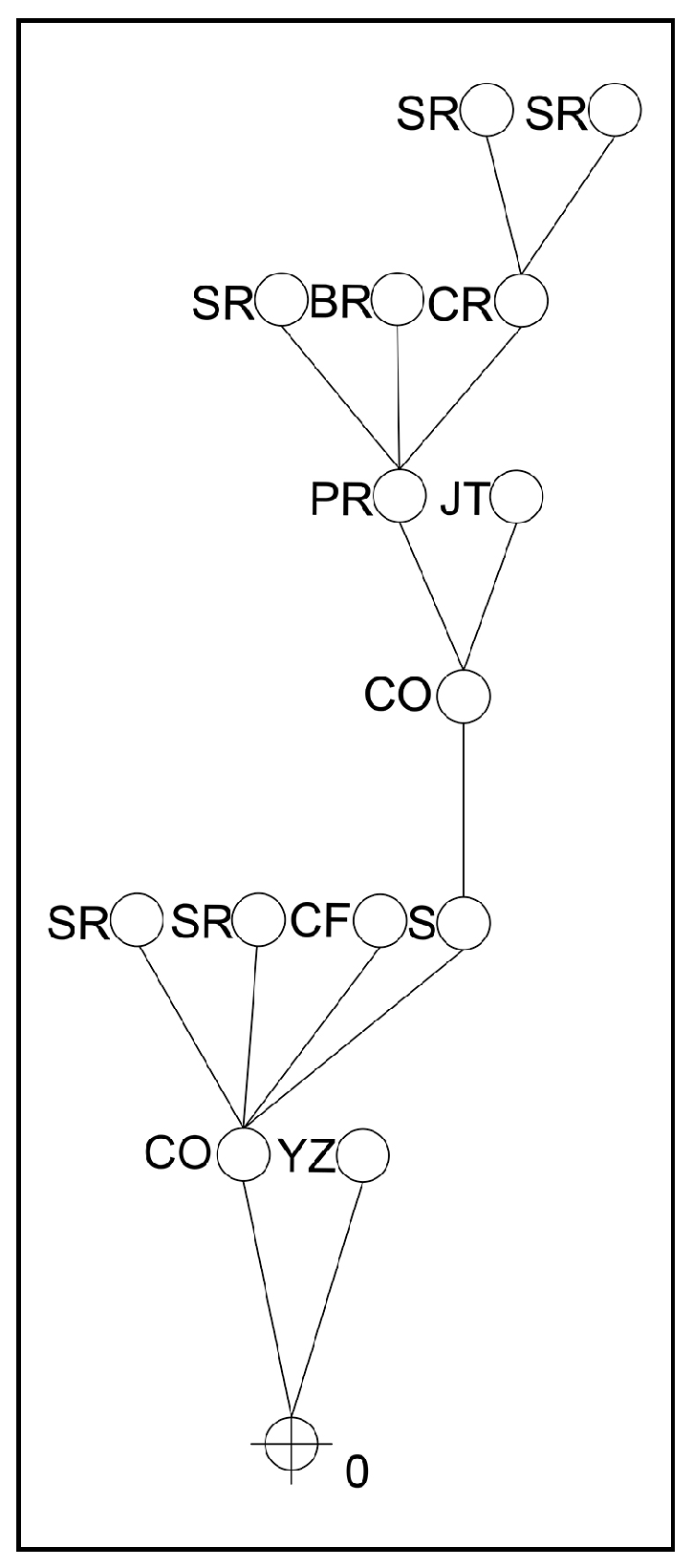

2.2. Space Syntax

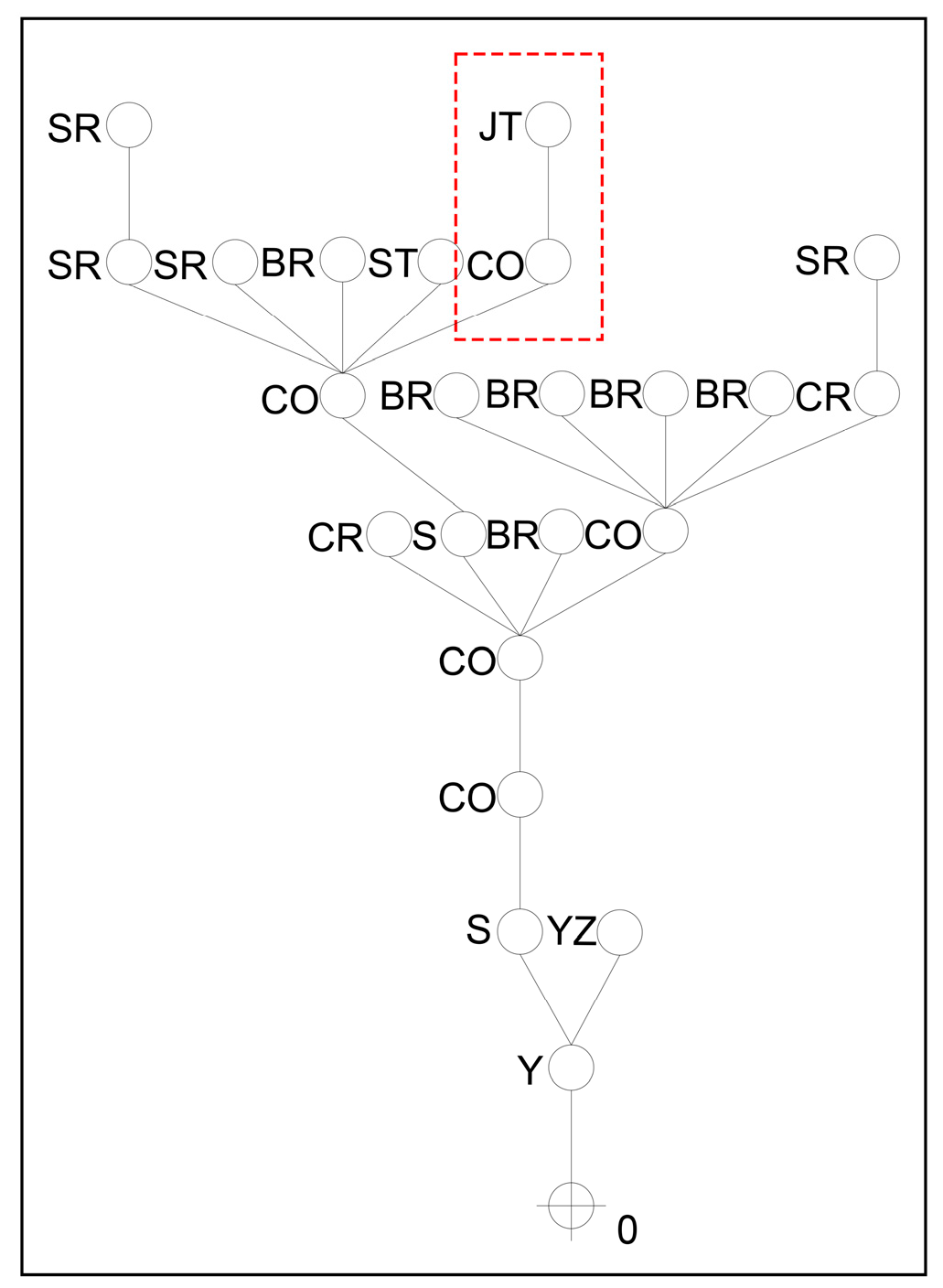

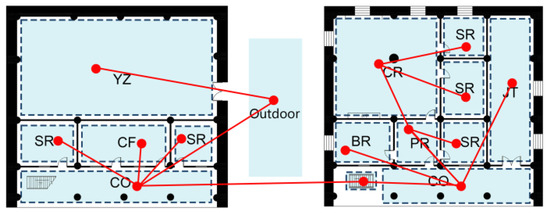

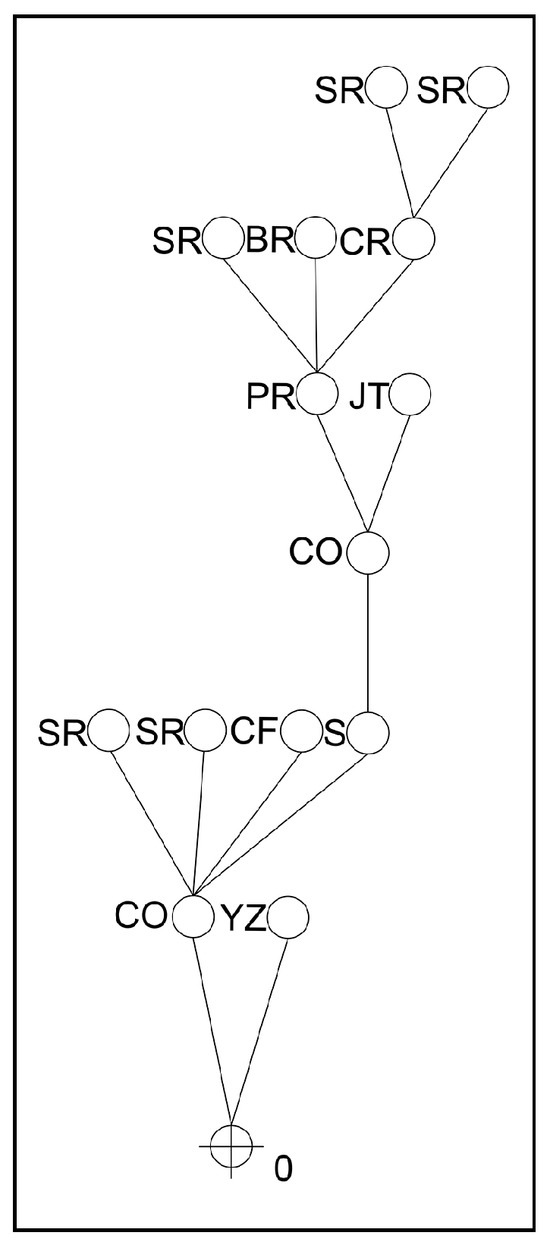

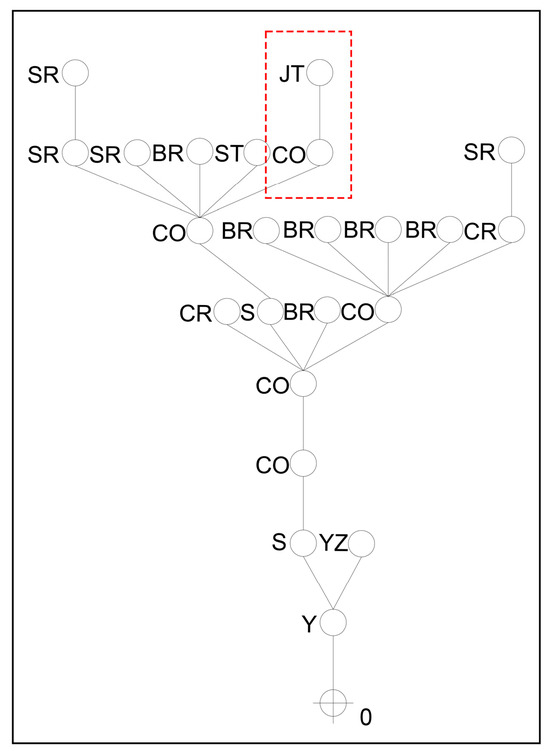

Space syntax is a theory and method that uses mathematical thinking to view the relationship between spatial forms at different scales and human activities, including three basic models of translating spatial relationships: Isovist, Convex Space, and Axial Line. In this study, we use the convex space model to analyze the spatial configuration relationship of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area. First, we divide the vernacular architecture into a number of convex spaces according to the visual principle of the convex space model and name each space (Figure 7); next, we show the connection relationship between each convex space, and because the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area are multi-story buildings, the connection relationship between the upper and lower floors should be reflected (Figure 8); finally, we get a justified plan graph (JPG) with “circle” representing the convex space and “line” representing the connectivity of the space (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Convex Space Division Schematic.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the connection relationship of convex space.

Figure 9.

Justified plan graph. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

Numerical calculations of mean depth (MD), integration (IRRA), and normalized choice (NACH) are performed based on the justified plan graph (JPG) (Table 1). Considering that the building samples are all multi-story buildings, the vertical distribution of the production space, the living space, and the spiritual space is regular from the previous analyses. Therefore, this study adopts a combination of global calculation and local calculation within a three-step topological radius to quantitatively explain and analyze the spatial relationship of vernacular architecture.

Table 1.

The main indicators in space syntax.

2.3. Min–Max Normalization

Min–max normalization is a linear transformation of the original data, through a function that normalizes three different values in the original data to a common range, maps the original data to the range [0, 1], and does not change the distribution of the original data, which is applied in this study to the data processing of the results of the computation of justified plan graphs (JPGs).

2.4. Kendall’s W Test

Kendall’s W test is mainly used to analyze the agreement between two or more sets of data, and this method is used in this study to analyze the consistency between global and local calculation results.

3. Results

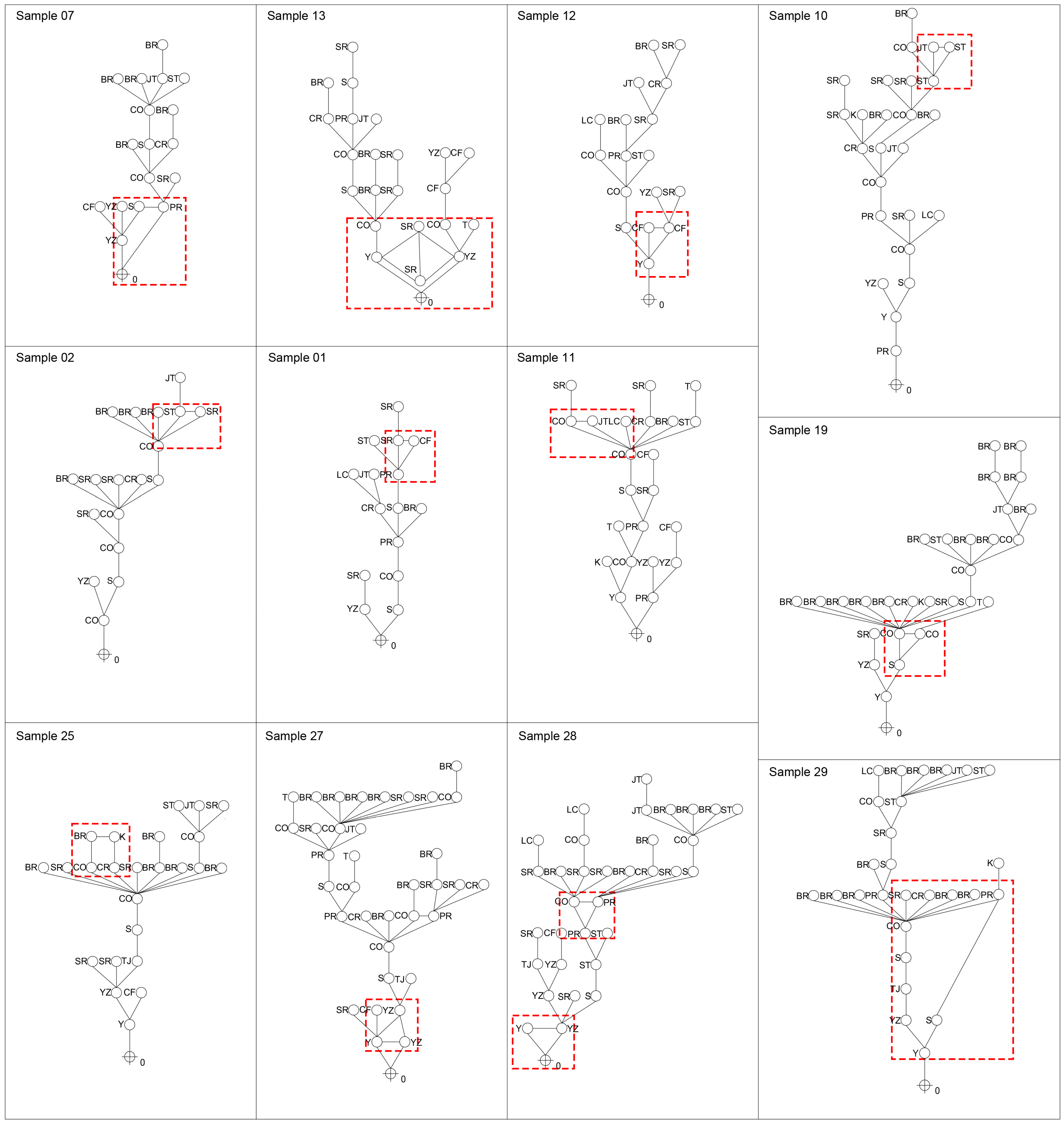

3.1. Justified Plan Graphs

Justified plan graphs (JPGs) are a method of visualizing and simplifying complex spatial relationships, from which we can make preliminary judgments about the topological depth of a space. Justified plan graphs (JPGS) translated from the sample of vernacular architecture in this study are generally tree-like. Among them, there is a cross on the circle of the starting node, which represents the root of the structure. In fact, it refers to the exterior of the building. Nodes on the same horizontal line are all at the same depth. Specifically, it includes two structural forms: multi-layer tree structure and tree-ring combination structure.

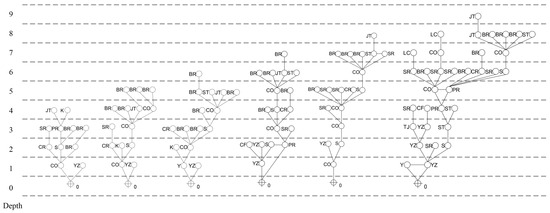

3.1.1. Multi-Layer Tree Structure

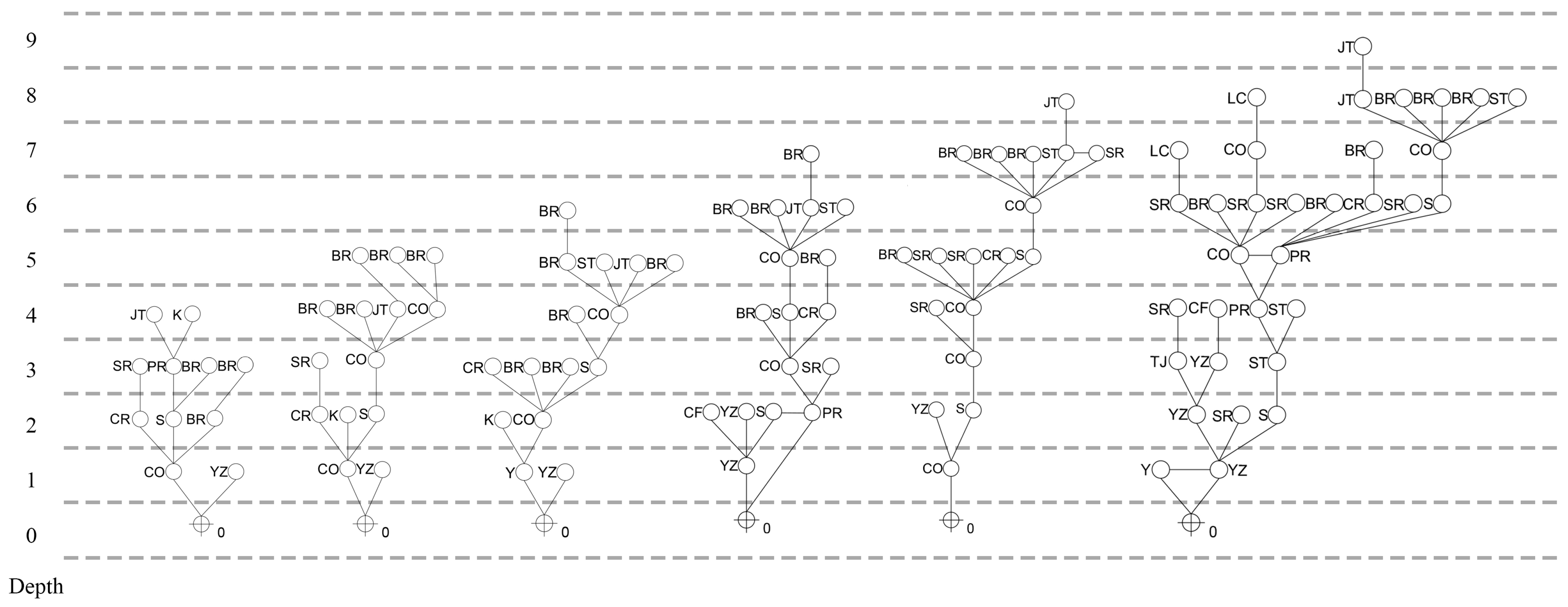

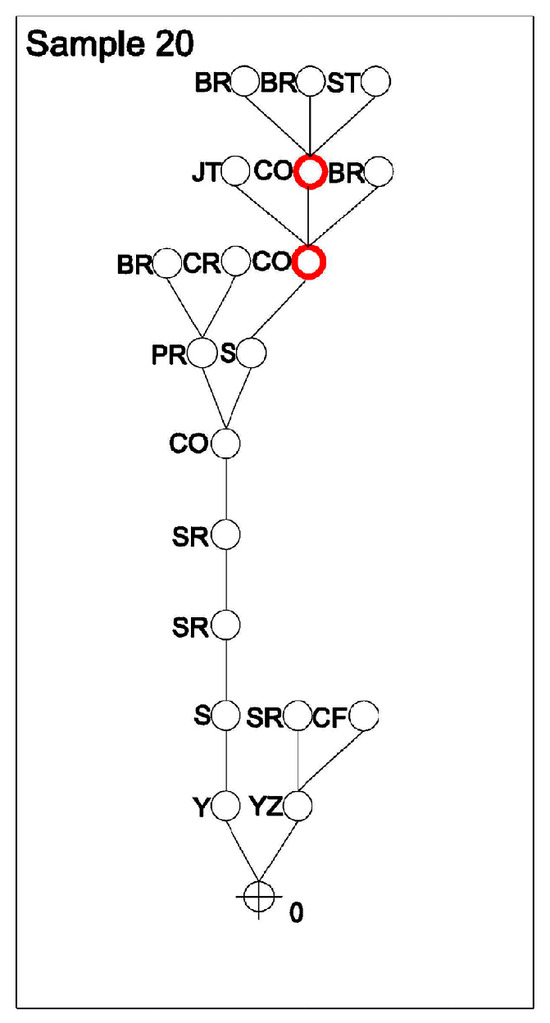

This type is a multi-branch, multi-level tree structure that starts from the root and continues to extend upward, including six topological depths of 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 (Figure 10), with a shallow structure at depth 4, a deep structure at depth 9, and the rest somewhere in between.

Figure 10.

Example of multi-layer tree structure topology depth. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

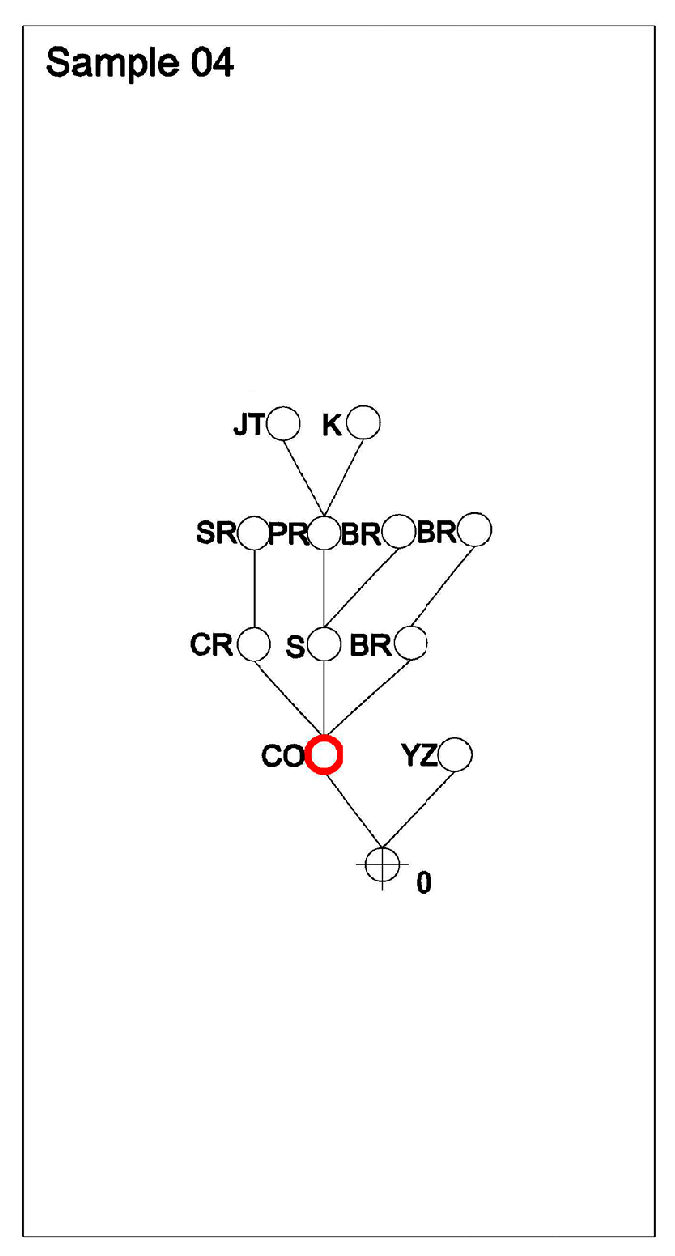

The shallow structure has a total of 12 nodes, and the overall spatial connectivity is simpler than the deep structure, extending outward from a major node to multiple nodes. The major nodes are shown in the red circles in the figure. The space type represented by the major node is the corridor, and there is no connection relationship between the nodes at the end, which indicates that the end space is more private (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The shallow structure.

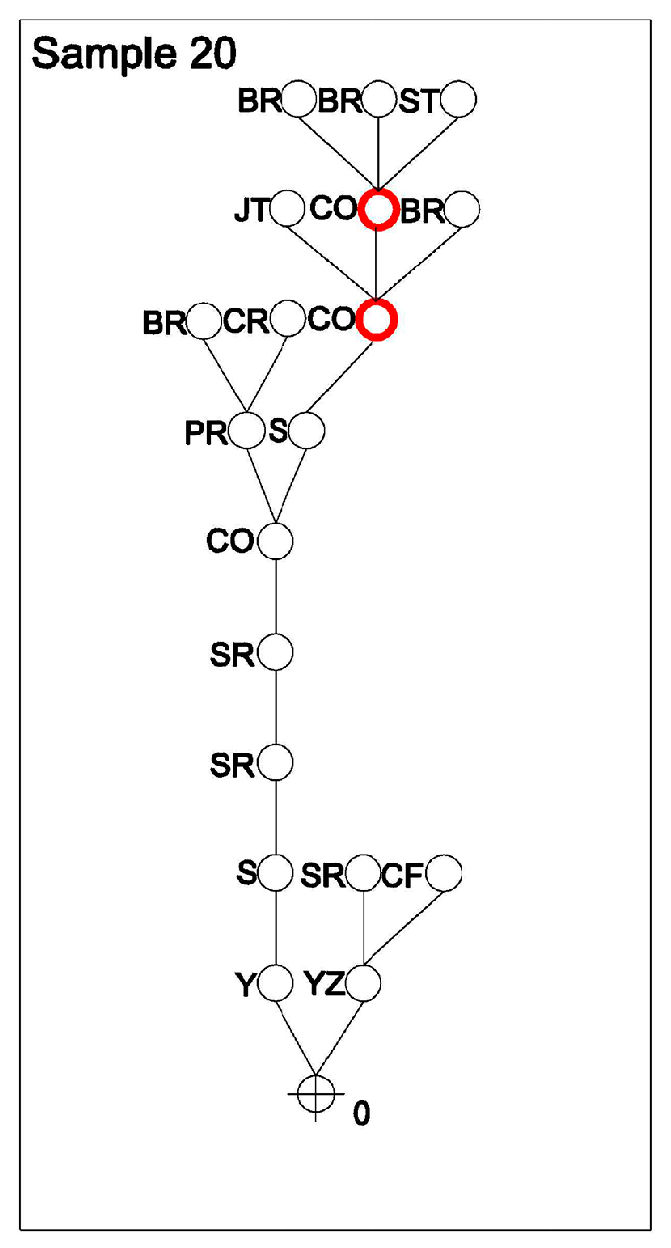

There are a total of 20 nodes in the deep structure, and the overall form is less symmetrical due to the high number of major nodes and the uneven distribution of their locations. This type of structure shows significant localized concentration, and the type of space represented by the major nodes is a corridor, which has four nodes connected (Figure 12). This structure illustrates the complexity of spatial connectivity due to the increase in the number of nodes.

Figure 12.

The deep structure.

The overall form of the structural schematic between shallow and deep shows significant asymmetry, with multiple clustered branched centers appearing locally. The type of space represented by the central node of each clustered branching center is the corridor, the entrance hall, and the courtyard, which indicates the presence of multiple centers and space groups in the space (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The structural schematic between shallow and deep. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

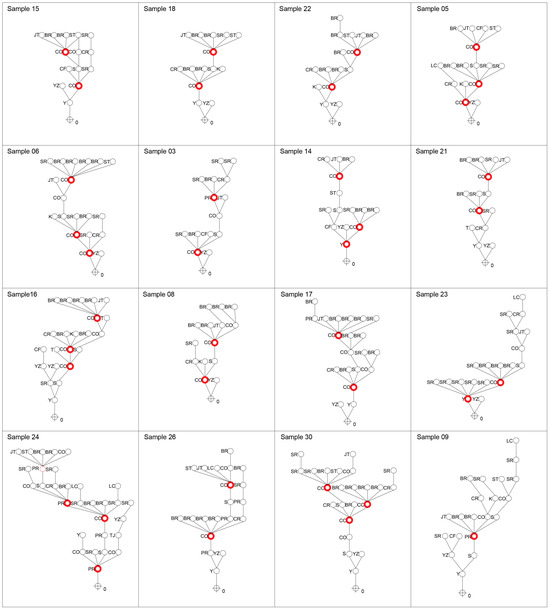

3.1.2. Tree-Ring Assemblage Structure

This kind of structure is based on the multi-layer tree-like structure, forming one or more ring-shaped connecting structures locally. Among them, the ring-shaped connecting structures are shown by the red wireframe squares in Figure 14, which indicates more possibilities for the way of connecting the space. At the same time, combined with the field research information, it is found that the ring structure mostly appears in two different connecting paths between the outside and the inside of the building. This indicates that during the construction process of the Yunnan–Tibet vernacular architecture, the Tibetan people consciously avoided the situation that the breeding area was at the entrance of the house, and instead, they reached the living space inside the local houses through another path. In addition to this, there are also multiple connections between the three types of transportation spaces, namely, the corridor, the staircase, and the entrance hall, which reflects the flexibility of the transportation relationship within the space, and there is also a ring-shaped connecting structure between the breeding area, the woodshed and the storage room space (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Tree-ring assemblage structure. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

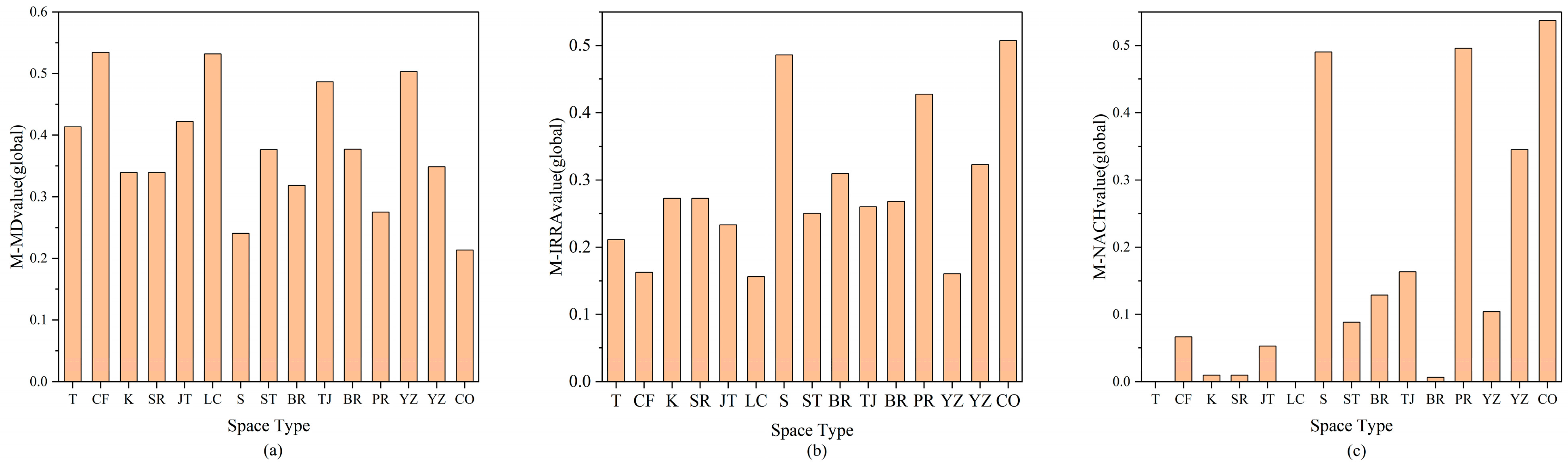

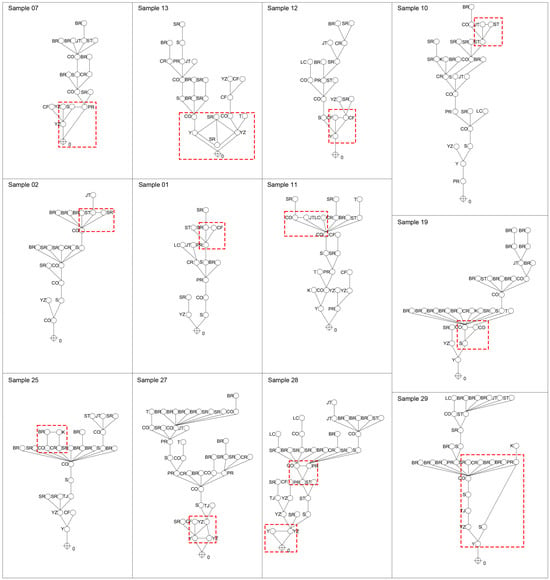

3.2. Global and Local Calculation Results

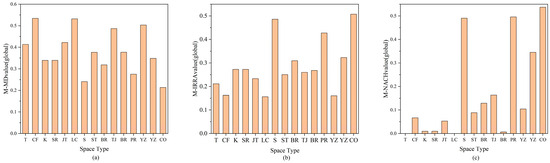

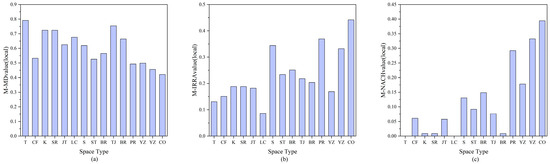

After the global calculation of 30 architecture samples based on justified plan graphs (JPGs), the mean values of the numerical results of each spatial type were taken for comparison after normalizing the data using min–max normalization, taking sample 1 as an example (Table 2). In the results, it can be found that the MD value of the granary (LC) is larger, and the order of the MD values of the rest of the spaces is: woodshed (CF) > breeding area (YZ) > patio (TJ) > scripture hall (JT) > toilet (T) > ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR) > courtyard (Y) > kitchen (K), storage room (SR) > TangWu (CR) > entrance hall (PR) > staircase (S) > corridor (CO) (Figure 15a).

Table 2.

Sample 1 data normalization results.

Figure 15.

Global calculation results: (a) MD value, (b) IRRA value, (c) NACH value.

The IRRA value of the corridor (CO) is the maximum value under the global calculation, and the ordering of the IRRA values of the rest of the spaces is: staircase (S) > entrance hall (PR) > courtyard (Y) > TangWu (CR) > kitchen (K), storage room (SR) > bedroom (BR) > patio (TJ) > ShaiTai (ST) > scripture hall (JT) > toilet (T) > woodshed (CF) > breeding area (YZ) > granary (LC) (Figure 15b).

The space type with the highest NACH value is the corridor (CO), and the rest of the spaces are ranked in order of NACH value as entrance hall (PR) > staircase (S) > courtyard (Y) > patio (TJ) > TangWu (CR) > breeding area (YZ) > ShaiTai (ST) > woodshed (CF) > scripture hall (JT) > kitchen (K), storage room (SR) > bedroom (BR) > toilet (T), granary (LC) (Figure 15c).

Then, the topological radius within three steps is selected for local calculation. On this basis, the obtained data is normalized, and finally, the mean value of each space is taken. In the results, it can be found that the MD values of each space are sorted as toilet (T) > patio (TJ) > kitchen (K), storage room (SR) > granary (LC) > bedroom (BR) > scripture hall (JT) > staircase (S) > TangWu (CR) > woodshed (CF) > ShaiTai (ST) > breeding area (YZ) > entrance hall (PR) > courtyard (Y) > corridor (CO) (Figure 16a).

Figure 16.

Local calculation results: (a) MD value, (b) IRRA value, (c) NACH value.

The ordering of IRRA values is: corridor (CO) > entrance hall (PR) > staircase (S) > courtyard (Y) > TangWu (CR) > ShaiTai (ST) > patio (TJ) > bedroom (BR) > kitchen (K), storage room (SR) > scripture hall (JT) > breeding area (YZ) > woodshed (CF) > toilet (T) > granary (LC) (Figure 16b).

The NACH values are ordered as corridor (CO) > courtyard (Y) > entrance hall (PR) > breeding area (YZ) > TangWu (CR) > staircase (S) > ShaiTai (ST) > patio (TJ) > woodshed (CF) > scripture hall (JT) > kitchen (K), storage room (SR) > bedroom (BR) > toilet (T), granary (LC) (Figure 16c).

3.3. Kendall’s W Test Results

Kendall’s W test was applied to check the consistency between the global and local calculated values of MD, IRRA, and NACH to assess whether the trend of the numerical results for each spatial type is consistent under the two different calculation methods.

The results show that the numerical trends of global and local MD values show consistency in statistical significance (p = 0.005 < 0.05; W = 0.538), indicating that the high and low ordering of the MD values of each space is consistent between global and local calculations, and the spatial types with larger depth values show consistency in both calculations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Kendall’s W test results.

The numerical trends of global IRRA values and local IRRA values showed consistency in statistical significance (p = 0.005 < 0.05; W = 0.538), indicating that the spatial types with higher accessibility in the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area showed consistency under global and local calculations (Table 3).

No statistical consistency was found for NACH values (p = 0.405 > 0.05; W = 0.046), which indicates that spatial types with transportation accessibility do not show the same trends under the global and local calculations. Moreover, the breeding area, as a non-transportation spatial type, is ranked higher under the local calculations. (Table 3).

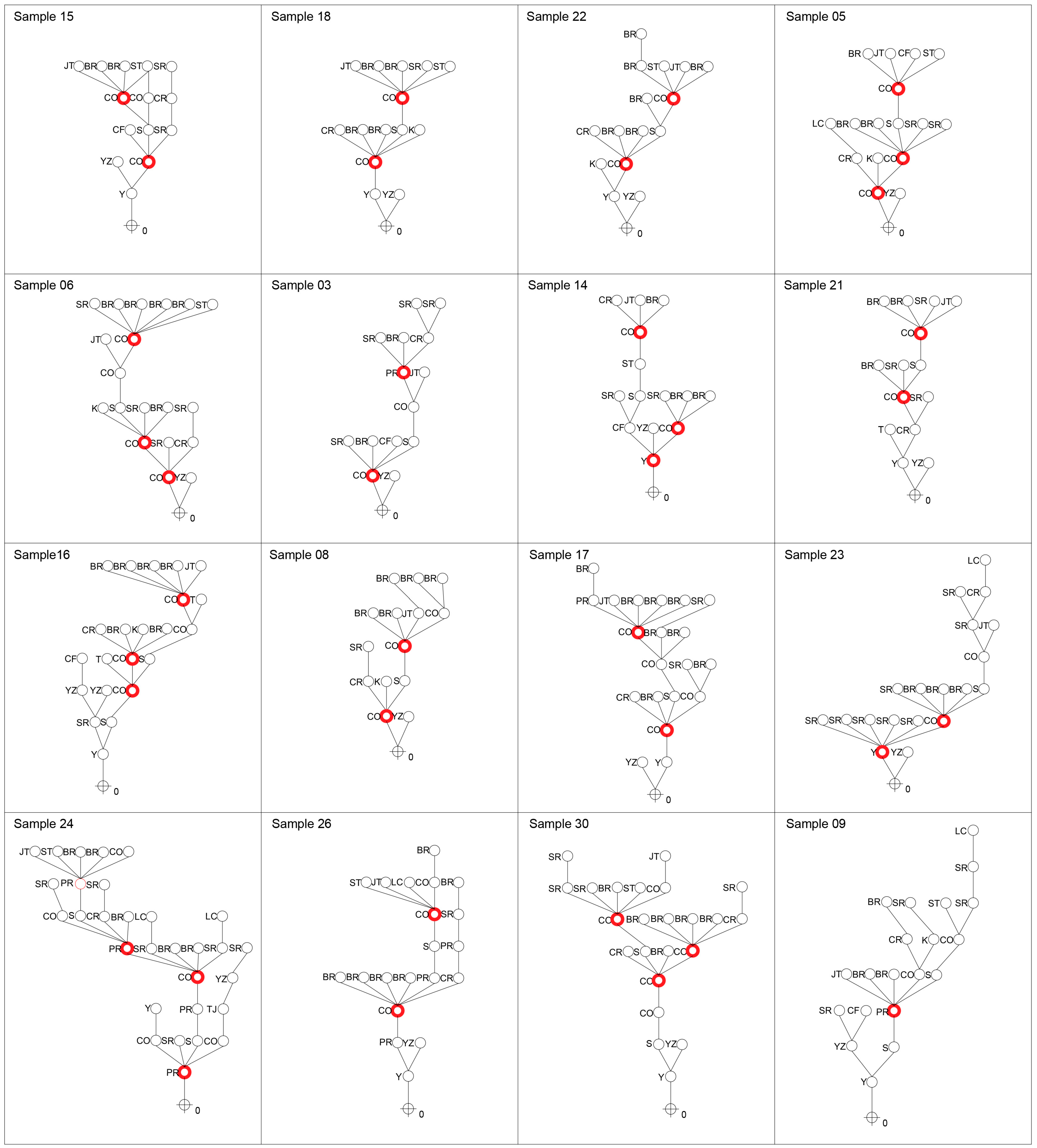

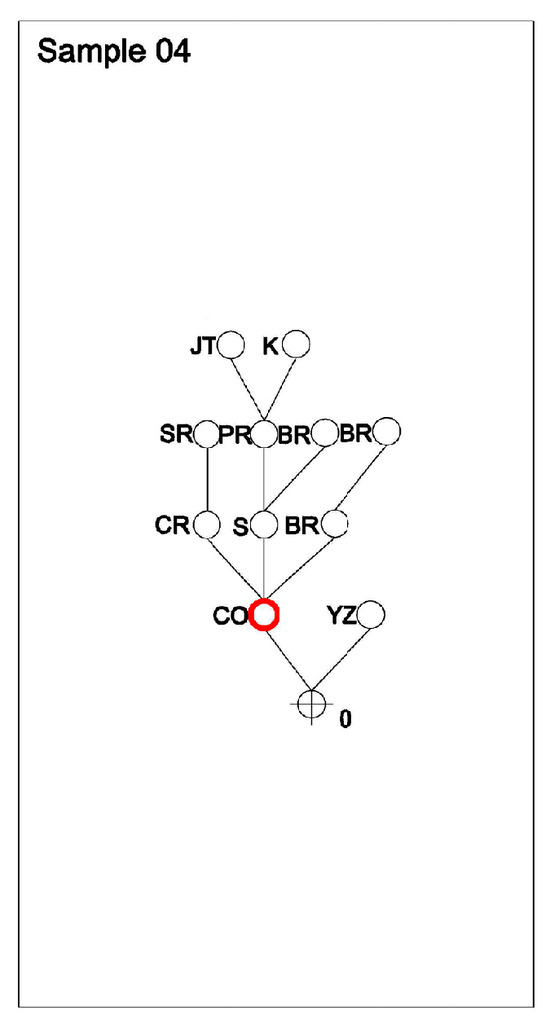

3.4. Differentiated Comparison Results

In the course of the study, it was found that some of the vernacular architecture had produced spatial types of differentiation with the development of the times, and the main spatial types of differentiation were the TangWu, the breeding area, and the toilet.

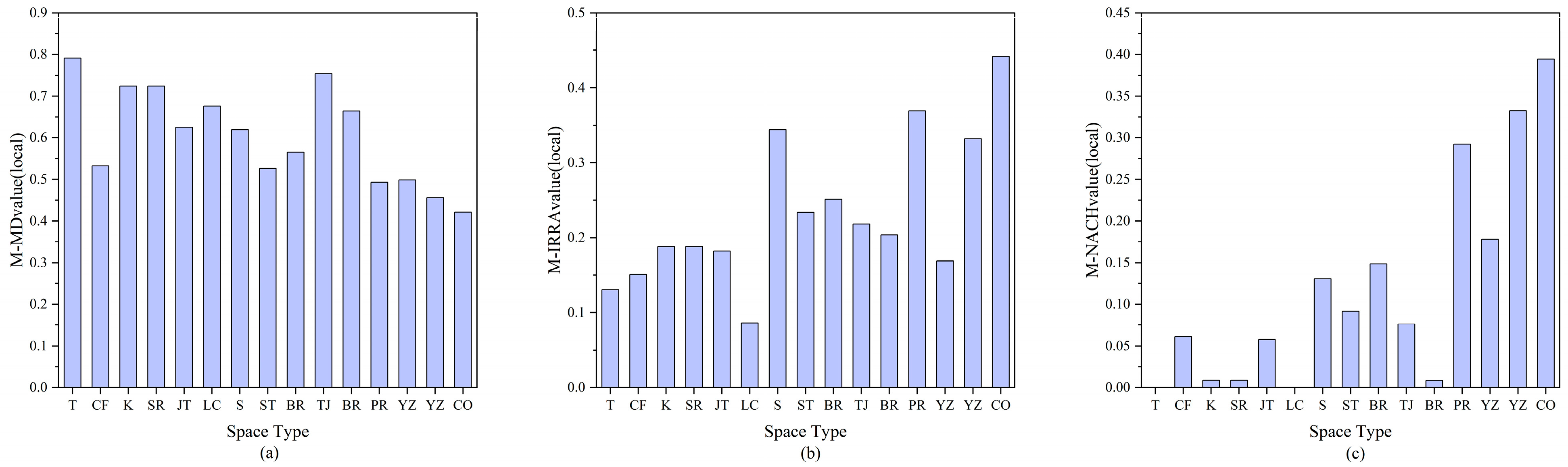

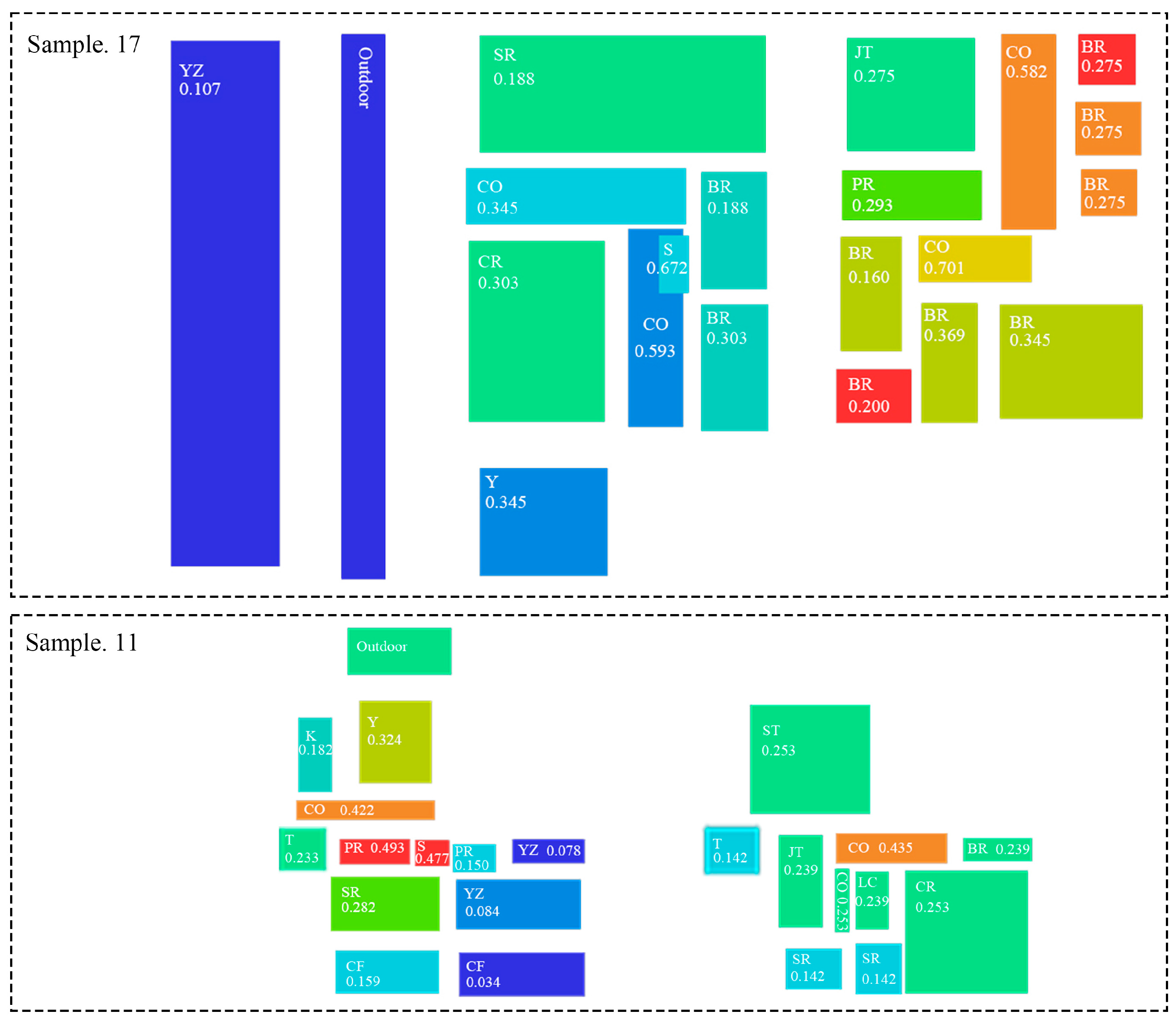

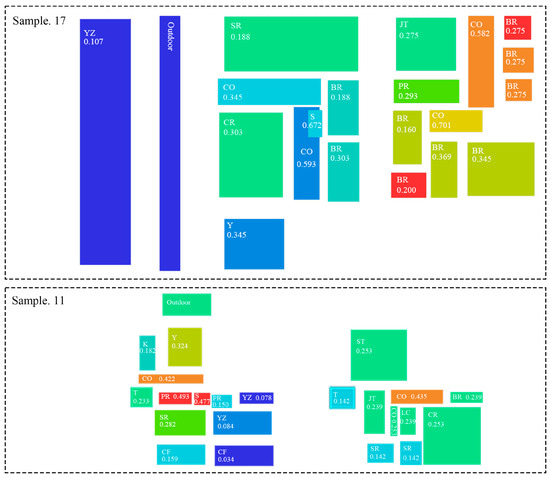

As an important space type integrating functions such as cooking, dining, gathering, and rituals, the functional attributes of cooking and dining are now gradually divorced from a single TangWu space into two spaces, TangWu and Kitchen. Taking sample 11 and sample 17 as an example, the global IRRA values of the TangWu before and after the differentiation are compared, and it is found that the IRRA value of sample 11 after the differentiation is lower than sample 17, and the accessibility of the space is reduced (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Comparison of global IRRA calculation results before and after TangWu space differentiation. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

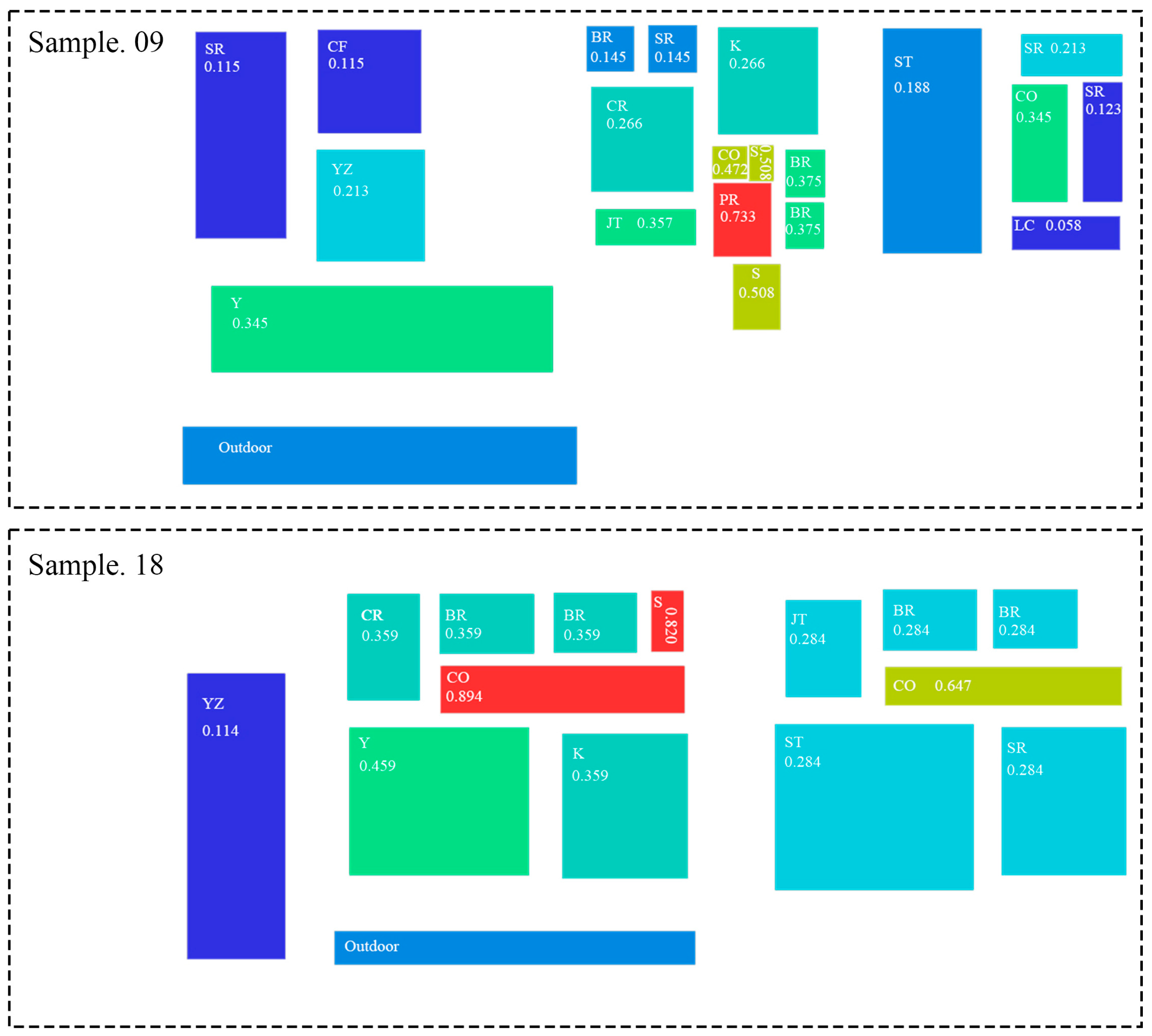

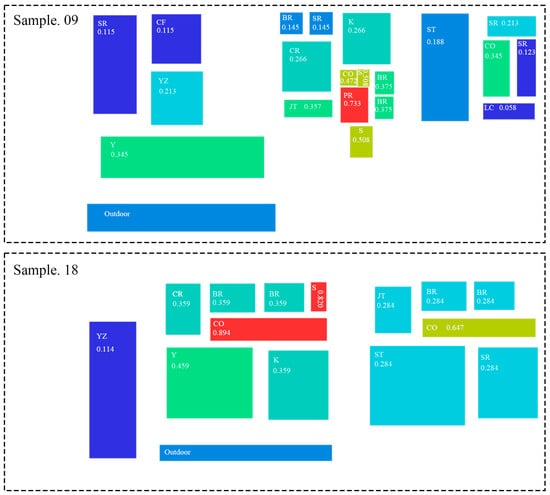

It is not difficult to see that most of the breeding areas are located on the first floor of the building, but there are also cases in which the breeding areas are placed outdoors. Taking sample 09 and sample 18 as an example, the global IRRA value of the breeding area located indoors is compared with that of the breeding area located outdoors, and the comparison shows that the IRRA value of sample 18 is lower than that of sample 09 (Figure 18), and the spatial accessibility of the breeding area of sample 18 is weaker.

Figure 18.

Comparison of global IRRA calculation results before and after Breeding area space differentiation. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

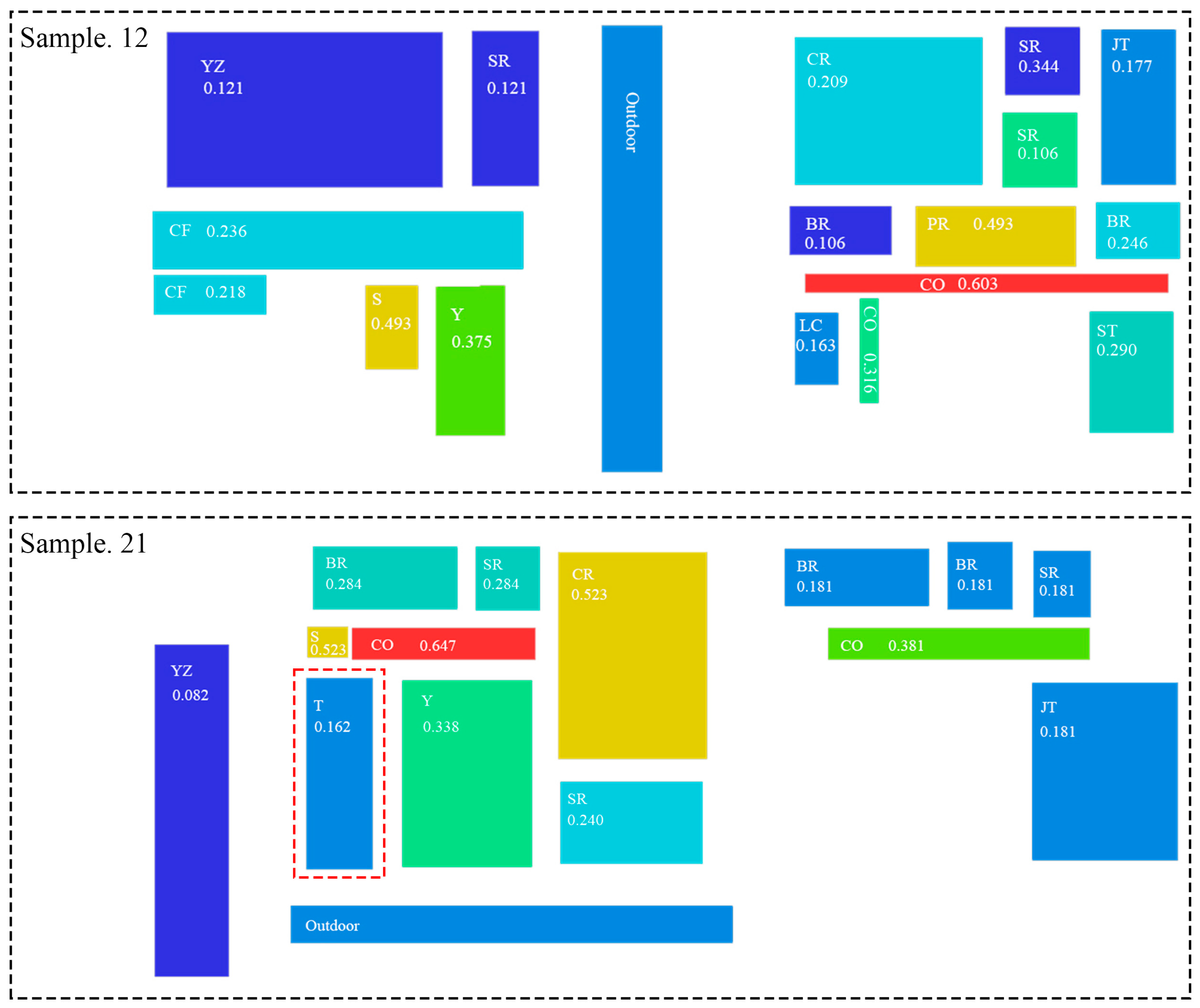

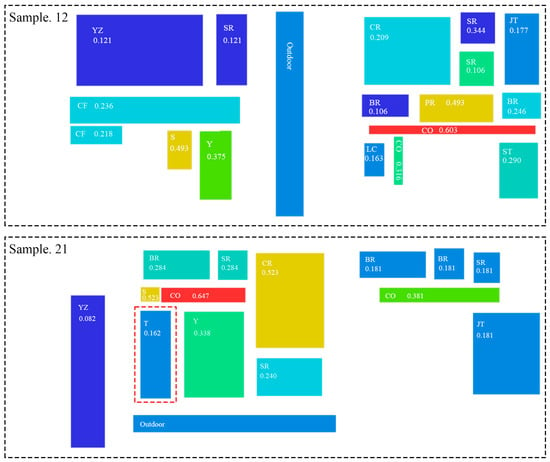

Another kind of spatial differentiation is reflected in the toilet space in the case of sample 12 and sample 21. For example, sample 12 does not have a toilet space, and sample 21 has a toilet space (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Comparison of global IRRA calculation results before and after space differentiation of toilets. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Spatial Configuration Relationships

From the analysis of the justified plan graphs above, it is concluded that the spatial configuration relationship characteristics of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area are asymmetrically distributed with multiple clusters of branching centers, and the corridor, staircases, and entrance halls are important spatial nodes linked with these clusters, and the topological structure of such multiple branching centers is affected by a variety of factors. The “three realms cosmology” concept of the universe is a summary and condensation of the worldview of the Tibetan people, which fully embodies the understanding of the social order in Tibetan culture. This conceptualization sees the entire universe as divided into three levels: the Divine Realm, the Nian Realm, and the Lu Realm, with the Divine Realm, referring to the place where the deities reside in the sky, the Nian Realm to the space above the land where human beings and all things of nature reside, and the Lu Realm to the world of all kinds of living beings below the land [39]. This abstract cultural logic has been mapped into the multi-story architectural form of today’s vernacular architecture, while the half-agricultural, half-pastoralist mode of production also influences the increase and division of spatial types. The shelters of Tibetan people reflect their social cognition, vertically stratifying the architectural space into the bottom space group for livestock, the middle space group for human activities, and the upper space group for religious activities, thus forming a spatial grouping relationship of multi-level and multi-space groups. Multiple spatial groups in the same vernacular architecture are connected by transportation spaces such as corridors and staircases, which shows the importance of transportation spaces in spatial connection.

Although the number of samples with a ring structure in the tree structure is relatively small, it also reflects the flexibility and freedom of the Tibetan in spatial configuration. From the above analysis, it can be seen that the ring-shaped structure appears in three different situations, which reflects that with the accumulation of time and experience, the Tibetans are gradually and consciously improving and optimizing their living environment, forming an endogenous development mode.

4.2. Analysis of Inheritance Factors

From the results of the consistency test above, it can be seen that the spatial forms of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area show commonalities. The samples of vernacular architecture selected for this study were all built between 25–35 years ago, and from the research, it can be seen that the construction of vernacular architecture is spontaneous, which means that the Tibetans have an endogenous drive to create their own vernacular architecture. By analyzing the regularity of the spatial forms, we can obtain the inheritance factors in the vernacular architecture that are built spontaneously and with a high degree of freedom, including the privacy of the granary space, the centrality of the corridor space, the transportability of the breeding area space, and the independence of the scripture hall space, which imply the cognitive level and cultural norms of the local Tibetan people.

4.2.1. Privacy of the Granary Space

From Table 3, it can be seen that the global calculation results of the MD value of the granary space have the same trend as the local calculation results, which shows that this type of space is farther away from the center space and has better privacy.

The deep depth of the granary space is not only related to its own spatial functional characteristics but also related to the defense psychology of the Tibetan people. In the space of vernacular architecture, the granary is usually set in the corner of the building’s sunny backside in order to reduce the influence of temperature change on the effective storage of food and also to improve the utilization rate of the sunny side. The Tibetans live in an uncontrollable natural environment, and under the influence of this natural environment, the Tibetan people have transformed the relationship between humans and nature into the relationship between humans and deities. In addition to this, historically, the Yunnan–Tibet area has also experienced the beliefs of disputes and social upheavals, the double impact of an uncontrollable natural environment, and war strife, which made the Tibetan people gradually form a defense mentality [40]. The granary is the main place for grain storage, and its concealment and security are related to the survival of the Tibetan people. Under the influence of defense psychology, this kind of space is set in a position with deep depth in the vernacular architecture. So, ethnic psychology is a reflection of the consciousness of each ethnic group toward the natural environment and other material forms formed under historical changes.

4.2.2. Centrality of the Corridor Space

The corridor space reaches the maximum value in both the global IRRA value calculation and the local IRRA value calculation, which indicates that the corridor space has a stronger ability to gather people flow in the vernacular architecture and has the attribute of the central space. Moreover, the corridor space belongs to the type of traffic space. It reflects the Tibetan emphasis on transportation between spaces, which means the pursuit of architectural utility.

The square structure of vernacular architecture has led to the modular division of indoor functional space, and based on the pursuit of the practicality of the Tibetan people, the connection between modules becomes the key. The Tibetan people live in a complex natural environment, and this square structure, which is closed to the outside and open to the inside. It is not only for the sake of warmth and earthquake resistance but also because the Tibetans have a strong sense of internal and external spatial differentiation in order to form a self-defense mechanism. In this context, the corridor space not only connects the inner space module but also serves as the core connection between the inner and outer space. Moreover, production–life–piety is the daily activity track of the Tibetan people, and all three are independent on different floors of the building, so the space of the corridor becomes an important spatial node that connects the activity track of the Tibetan people. Therefore, whether it is the pursuit of practicality or the constraints of national psychology, the accessibility of the corridor space is gradually enhanced and becomes the center space.

4.2.3. Transportability of the Breeding Area Space

From Table 3, it can be seen that the value of the breeding area space is higher in the local calculation of NACH value, which indicates that the space of the breeding area as a non-traffic type has transportability in the local spatial relationship.

The climate and environment of the Yunnan–Tibet area provide them with fertile grasslands and pastures. At the same time, the intake of high-calorie food and the need for warm clothing have made animal husbandry the main mode of production for Tibetans, and breeding areas are their main type of production space. Since the development of the Yunnan–Tibet area animal husbandry, the domestication and feeding of livestock have been the basis of its development. Among them, feeding and herding are the center of production activities, and the Tibetan people carry out herding in groups according to the different kinds of livestock, and there will be different ways of herding in different seasons. The breeding area is the main space responsible for feeding and herding activities, and the storage room for fodder is located in a location with a deep depth value, so its accessibility not only provides convenience for the acquisition of fodder but also facilitates the grazing of domestic animals. Based on the vertical layering characteristics of the residential space type, the transportability of the breeding area space improves the organization of production spaces on the same floor, which in turn improves the efficiency of production activities.

4.2.4. Independence of the Scripture Hall Space

The scripture hall space is an important spiritual space that carries the daily religious rituals of the Tibetan people. The IRRA value of this space is ranked low, and there is only one space connected to it in the justified plan graphs (JPGs), as exemplified by sample 30 (Figure 20). This shows that the scripture hall space has good independence in the overall connectivity of the space.

Figure 20.

Schematic diagram of the connection relationship of the scripture hall space in the justified plan graph. Note: Granary (LC), woodshed (CF), breeding area (YZ), patio (TJ), scripture hall (JT), toilet (T), ShaiTai (ST), bedroom (BR), courtyard (Y), kitchen (K), storage room (SR), TangWu (CR), entrance hall (PR), staircase (S), corridor (CO).

The culture of faith is the spiritual core of each ethnic group, capable of sustaining and organizing its social behavior. The reason why the Tibetan nation can still become an ancient nation standing on the top of the plateau in the change of dynasties and social development is precisely because it has formed and inherited its own religious belief culture. The inheritance of such a spiritual kernel is also embodied in the development of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area. Tibetan forefathers had a natural fear of all things, which formed respect for the mountains and water, the unity of man and heaven, and the coexistence of all things; these beliefs are the root of the Tibetan people’s belief in the culture of Bon Religion [41,42]. Then, in the thousands of years of collision and fusion between Bon Religion and Buddhism, national beliefs permeate the concepts of production and life of the Tibetan people and run through the life and social activities of the Tibetan people. As the carrier of the spiritual world of the Tibetan people, the scripture hall space is the physical manifestation of the beliefs of the Tibetan people and carries important folk activities, and except for the monks and lamas and other honored guests, it is not allowed for any ordinary people to live there. In the construction process of the vernacular architecture, the space of the scripture hall is the most gorgeous decoration, and in the connection relationship between the space of vernacular architecture, it is located in the highest level of the spatial setup, and there is only one space connected to it, so as to reflect its independence and sublimity.

4.3. Differentiation Factor Analysis

4.3.1. Functional Evolution of Traditional Space

The TangWu space is equipped with important folk cultural feature elements such as central columns, fire pits, and water pavilions, and is usually regarded as the core of traditional culture in vernacular architecture. As can be seen from the above text, in the buildings constructed in the past three decades or so, the TangWu space has been divided into two spaces: the TangWu and the kitchen. This is related to the gradual transformation of the daily activities of the Tibetan people toward modern life.

Before the reform and opening up, the production and life of the Tibetan people were dependent on the background of agricultural civilization. The energy structure was restricted, and livestock manure and firewood were the main sources of heating. Moreover, due to the scarcity of material resources, heating sources were concentrated in a single space. Therefore, a series of activity trajectories closely related to the survival of the Tibetan people are all concentrated in the TangWu space. Influenced by modern life concepts, the Tibetan people gradually developed an awareness of public and private spaces. The cooking and dining functions in the TangWu were separated and divided into two different spaces for receiving guests and for family solitude. The development of modern technology and energy has led to the popularization of cooking tools and heating equipment. In addition, independent cooking spaces are more conducive to solving ventilation and smoke exhaust problems and further optimizing the indoor living environment.

The functional differentiation of the TangWu space is the result of the impact of modern human settlement concepts on traditional settlement concepts. However, the social development in the Yunnan–Tibet area is relatively lagging behind [43]. Therefore, with the rapid development of science and technology today, the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area of Yunnan has only shown this slow differentiation phenomenon in the past two or three decades. On the one hand, it is due to the remote geographical location and inconvenient transportation. On the other hand, it is because of the survival awareness of respecting nature formed by the Tibetan ethnic group during its development. The development of the new social form has placed the Tibetan people in a period of recuperation and prosperity. The life of the Tibetan people is both for survival and to meet the needs of a better life. As a result, there has been a reduction in collective defensive life and an increase in the demand for personal private space.

4.3.2. Reorganization of the Location of the Breeding Area Space

In the results of the differentiation, it can be seen that there are cases of placing the breeding area outdoors in the vernacular architecture built in the last 30 years. This affects to some extent the connection between the breeding area space and the rest of the space.

During the research process, it was found that the indoor environment of some of the breeding area located on the first floor was poor. The excrement of humans and animals was piled up randomly and not treated. The coexistence of humans and animals in the same room also increased the risk of common diseases. For this reason, the local government began to implement the policy pilot of “separation of humans and livestock” as early as 2012. The implementation of this policy has enhanced the tidiness of indoor spaces. The partitioned nature of the space has cut off the transmission chain of diseases, making the prevention and control of human and animal diseases more effective. From the perspective of the Tibetan people’s national consciousness—the consciousness of purity, placing the breeding area outdoors also conforms to the distinction between the sacred and the secular. In addition, modern human settlement concepts are gradually influencing the Tibetan people’s increasing requirements for indoor environments.

Under the construction of the new era, the Yunnan–Tibet area in Yunnan is confronted with the contradiction between the traditional natural economy and the emerging market economy. The Tibetan people in a state of “self-sufficiency” do not have a strong sense of wealth accumulation, which is also related to the “otherism” in their national consciousness [43,44]. “Otherism” emphasizes the detachment from mundane desires, but the development of emerging market economies has brought the possibility of wealth creation to the Tibetan people. The outdoor breeding area is conducive to the modernization of the local animal husbandry. The government’s development and management of local animal husbandry have enabled the Tibetan people to increase their income on the basis of self-sufficiency.

4.3.3. “Toilet Revolution” with Multiple Drivers

In the context of rural revitalization, Diqing Prefecture began to implement the “toilet revolution” work program in 2017 that aims to improve the hygiene management of households in order to build a beautiful countryside. In this study, it was found that there were fewer toilet spaces in the sample. From the field research, it can be seen that in the vernacular architecture without toilet space, the human defecation place and the livestock on the ground floor are in one place.

The ecological environment of Diqing Prefecture is fragile, with a large ecological threshold, so an overly large or dense settlement layout is potentially hazardous to the environment, and non-standardized defecation patterns add to the burden on the local ecology. The standardization of toilet space has led to the formation of a “toilet + biogas + planting” cycle, and the harmless treatment of feces has reduced the degree of pollution of local water sources. Under the effective guidance of the government, the local Tibetan people’s awareness of personal hygiene has gradually increased, but some of the hygiene habits may be contrary to traditional folk beliefs. For example, under the influence of the Tibetan concept of cleanliness, toilets should not be placed indoors. However, after the founding of New China, the medical care, education, and culture of Diqing Prefecture have gradually shifted from “traditional” to “modernization”, and new ideas and concepts have weakened the existence of reliance on faith in the hearts of the Tibetan people, and the importance of human beings has become more and more prominent. As a result, local traditional culture and modern health concepts show “coexistence” and “tolerance”, and the relationship between tradition and modernity is intertwined [45], making the ethnic culture of Yunnan–Tibet more vivid and lively.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study is to explore the social logic and cultural law in the spatial form of the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibetan area by linking the three dimensions of space–time–vernacular architecture and, for the first time, applying the principle of spatial syntax to the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibetan area. This study proposes the inheritance factor and differentiation factor in the vernacular architecture built in the past 25–35 years through quantitative calculations and qualitative analyses of the samples of vernacular architecture.

The study shows that (a) the hierarchical spatial distribution form formed by the understanding of the “three realms” of social order in Tibetan ethnic culture further verifies the rationality of this study’s combination of global calculation and local calculation. (b) National psychology is an important component of Tibetan folk culture. The dual influence of the uncontrollable natural environment and wars and disputes has gradually led the Tibetan people to form a defensive mentality. At the same time, due to the temperature and humidity requirements for food storage, the granary space is located in a position with a relatively large depth value in the building. Production–life–piety are the daily activity trajectory points of the Tibetan people, and the three are concentrated in different spatial types. The corridor space connects these three parts and becomes the space that is most likely to gather people. The production activity trajectories of the Tibetan ethnic group are all located on the same floor. Among them, the space of the breeding area has transportation characteristics in the production activity trajectories. This is a rule that has been in the formation of the production habits of the Tibetan ethnic group for many years and is a manifestation of human beings’ active adaptation to nature and society. The scripture hall space carries the daily religious life of the Tibetan people. From the perspective of spatial connection relationship, it possesses sublimity and is the materialized manifestation of ethnic beliefs. (c) Through differentiation analysis, it is concluded that traditional spaces such as the TangWu are differentiating with the deepening of modern concepts. The Tibetan people have gradually transformed from the concept of gathering activities to that of public and private spaces. With the support of the policy background and the need for a healthy life for the Tibetan people, new ideas and concepts have weakened the reliance on faith in the hearts of the Tibetan people. Local traditional culture and modern hygiene concepts have shown coexistence. The space of the breeding area is independent outdoors, which provides convenience for the development planning of local animal husbandry. Meanwhile, the independent setting of indoor toilet spaces is being gradually advanced.

The main contribution of this study lies in the use of data to visualize the commonality and individuality in the sample of vernacular architecture, and, on this basis, the formation of inheritance and differentiation factors are related to the developmental origins of the ethnic culture and the development and change of the social form, exploring the law of the role of cultural survival on the spatial forms of vernacular architecture. Furthermore, it provides a new research path for understanding the law of change and development of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area and a new perspective for interpreting the vernacular architecture in the Yunnan region of China. Finally, this study complements the protection of the diversity of the architectural heritage of ethnic minority vernacular architecture.

At the same time, although the 30 residential samples selected in this study are representative, they may not be able to encompass the full diversity of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area. In addition, this study only investigates vernacular architecture from the perspective of spatial dimension, ignoring the analysis and research on the architecture of vernacular architecture from the perspectives of volume and vision. Therefore, in the future, we can explore the inheritance and differentiation of vernacular architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet area from multiple dimensions and use advanced computer technology to expand the study to a wider field.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, K.W.; methodology, K.W. and H.W.; formal analysis, K.W. and H.L.; investigation, K.W., H.L., H.W., M.Y., Y.S., J.X. and M.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.S., J.X. and M.Q.; supervision, Y.S. and M.Q.; funding acquisition, J.X., Y.S. and M.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research on the Construction and Design Application of Decorative Color Painting Atlas for Folk Houses in Yunnan Tibet Region (24YJA760126), the Department of Social Sciences, Ministry of Education, Youth Project, Research on the Living Inheritance and Innovative Design of Bamboo Weaving Techniques of Ethnic Minorities in Yunnan, (19XJC76005), and the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund of Southwest Forestry University, Research on the Degradation of Mechanical Properties of Typical Mortise and Tenon Joints of Tusi Manor in Yunnan–Tibet Region (110225005).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhong, Z. Decoration Room: A Study on the Regeneration and Cultural Context of Li Traditional Houses in Tourism Landscape Design. Furnit. Inter. Decor. 2025, 32, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Discussion on the industrial development mode of Zhouhuang historical and cultural heritage. Soc. Sci. 2025, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, C.; Zhu, Y. Visiting sequence:A research perspective on the identification and interpretation of the value of historical gardens. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 1–8. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2165.TU.20250403.1345.002.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Zhou, Q.; Liang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C. The “core” and “periphery” in the Dai house—Taking Meng Lian Na Yun as an example. Archit. J. 1–7. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1930.TU.20250427.1138.006.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Peng, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, F.; Zhu, P. Evaluation and renewal mechanism of cultural tourism development potential of urban built heritage: A case study of the main urban area of Dalian. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 1504–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, A.M.; Patiño, G.L.; Blanca-Gimenez, V.; Clemente, I.T. Analysis of the Hygrothermal Conditions of the Vinalopó Medio Cave Houses (Alicante, Spain). Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 162, 106611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoying, L.; Ming, L. Adaptive Changes to Korean Vernacular Houses in Northeast China: The Influence of Changing Family Patterns on Spatial Capacity. Open House Int. 2025, 50, 324–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bigiotti, S.; Santarsiero, M.L.; Del Monaco, A.I.; Marucci, A. A Typological Analysis Method for Rural vernacular architecture: Architectural Features, Historical Transformations, and Landscape Integration: The Case of “Capo Due Rami”, Italy. Land 2025, 14, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Chen, Y. Research and Practice on Protection and Design Guidelines for Historic Towns—Taking Pingyao as an Example. J. Urban Plan. 2020, 6, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Chen, Y. Cultural Origins and the Protection and Inheritance of Traditional Houses—An Examination Based on the Traditional Houses of the Cai Clan in Fujian. Guangxi Ethn. Stud. 2020, 4, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Luxi, Y. A Critical Analysis of the Yin Yu Tang Project and the Preservation of Huizhou-Style vernacular architecture in China. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2022, 34, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, M.; Gu, X. Optimization Strategies for Conservation of Traditional vernacular architecture in Hongcun Village, China, Based on Decay Phenomena Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276306. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.Y. Research on the Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Island Stone vernacular architecture in China. J. Sci. Des. 2022, 6, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, M.; Gu, X. The Research on the Evaluation and Optimization of the Traditional Dwelling Conservation Practice: A Case Study of Cheng Zhi Hall Restoration Project within Hongcun. J. Archit. Res. Dev. 2020, 4, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Design and Implementation of Traditional Residential Protection and Development System Based on View of Landscape Information Chain. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1345, 062053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P. “Survival-Growth-New Life”—Schematic Design of Cellar Village Renovation. Build. Struct. 2022, 52, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Evaluation of Residential Suitability of Traditional Residential Hammock in Qiandongnan. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2022, 43, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, N.; Gao, M.; Feng, J.; Zhou, Z. Design Intervention and Co-Creation: The Case of Gao Dang Buyei Mountain Village. Decoration 2022, 4, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Solang, B.; Chang, Q. Research on Climate Adaptation of Traditional Residential Buildings in Lhasa. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 52, 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.; Bian, G. A Strategic Study on the Ecological Transformation of Rural vernacular architecture in Lingnan Region—Taking the Example of Xiangang Villagers’ Residence Transformation Project in Foshan. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 34, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Solang, B.; Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Research on the Contemporary Construction of the Main Room Space of Traditional Qiang vernacular architecture. Chin. Cult. Forum 2017, 6, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, H.; Yin, Q.; Pu, Y. A Study on the Evolution of Raw Soil Dwelling Types in Inner Mongolia along the Route of the Westward Exit. J. Archit. 2024, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Jia, B. Differentiation and Transformation—Evolution of Spatial Types of Durian Residences from Ming and Qing Dynasties to Contemporary Times in Taishun Area, South Zhejiang. J. Archit. 2023, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Y. Research on the Design of Traditional Residential Remodeling Based on Schema Fusion—Taking Phoenix Inn as an Example. Decoration 2023, 09, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Zhuo, X.; Xiao, D. Ethnic Differentiation in the Internal Spatial Configuration of Vernacular vernacular architecture in the Multi-Ethnic Region in Xiangxi, China from the Perspective of Cultural Diffusion. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Li, J. Genotype Extraction of Traditional vernacular architecture Using Space Syntax: A Case Study of Tibetan Rural Houses in Ganzi County, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Ismail, A.S. Huizhou Residences under the Influence of Zhu Xi Neo-Confucianism. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2024, 11, 2438477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçen, D.; Özbayraktar, M. Integrating Space Syntax and System Dynamics for Understanding and Managing Change in Rural Housing Morphology: A Case Study of Traditional Village Houses in Düzce, Türkiye. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasiewicz-Sych, A.; Lewicka, M. The Engagement of Polish Residents with Their Home Space in Single-Family Houses and Flats in Multi-Family Blocks of Flats. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 1035–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, F.C.; Greene, M. The Poet Neruda’s Environment: The Isla Negra House. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-H. Tibetan Folk Houses in Yunnan; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. Crystallization of Two Cultures—Tibetan Houses in Zhongdian, Yunnan. Cent. China Archit. 1998, 4, 135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Su, Y.; Qiang, M.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, Z. A Study on the Atlas and Influencing Factors of Architectural Color Paintings in Tibetan Timber vernacular architecture in Yunnan. Buildings 2024, 14, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kang, W.; Su, Y.; Li, F.; Qiang, M. Relationship Between Visual Attractiveness and Aesthetic Preference of Door Decoration Patterns of Wood-Framed vernacular architecture in Yunnan-Tibet. J. For. Eng. 2025, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Tang, R.; Ji, J.; Qiu, J. Conflict and Countermeasures of Yunnan Tibetan Houses in Contemporary Protection and Needs Under the Perspective of Fire Safety. Archit. Cult. 2021, 10, 254–256. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J.; Tie, L. A Study on Spatial Schema of Tibetan Houses in Yunnan. Settlement 2011, 6, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, M. Exploration of the Formal Characteristics and Causes of Traditional Tibetan Houses in Diqing, Yunnan—Based on the Field Survey and Comparative Study of Tangman Village. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 43, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Che, M. Contacts, exchanges, and blending of various ethnic groups are the mainstream of the historical development of the Tibetan people. Tibet. Stud. 2020, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. On the belief of the gods in Tibet. Stud. Ethn. Lit. 2003, 3, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Lv, X.; Liu, J. Research on the psychological defense mechanism in the Tibetan settlement environment. Archit. J. 2010, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Han, X. The Formation of Early Tibetan Folk Beliefs and the Integration and Adaptation of Buddha and Benzene--Ancient Tibetan Manuscripts of Bon in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2011, 39, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jiangbian, J. On the concept of “yang” and the nature worship of the Tibetan ancestors. Tibet. Stud. 1994, 1, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Angben, D. History of Tibetan Culture Development; Gansu Education Press: Gansu, China, 2001; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W. On the influence of Tibetan Buddhist belief on Tibetan social psychology and behavior. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2011, 32, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Tibetan Journal: Listening to the Sounds of the Countryside: The Life and Culture of the Tibetans in Yunnan; Yunnan University Press: Kunming, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).