1. Introduction

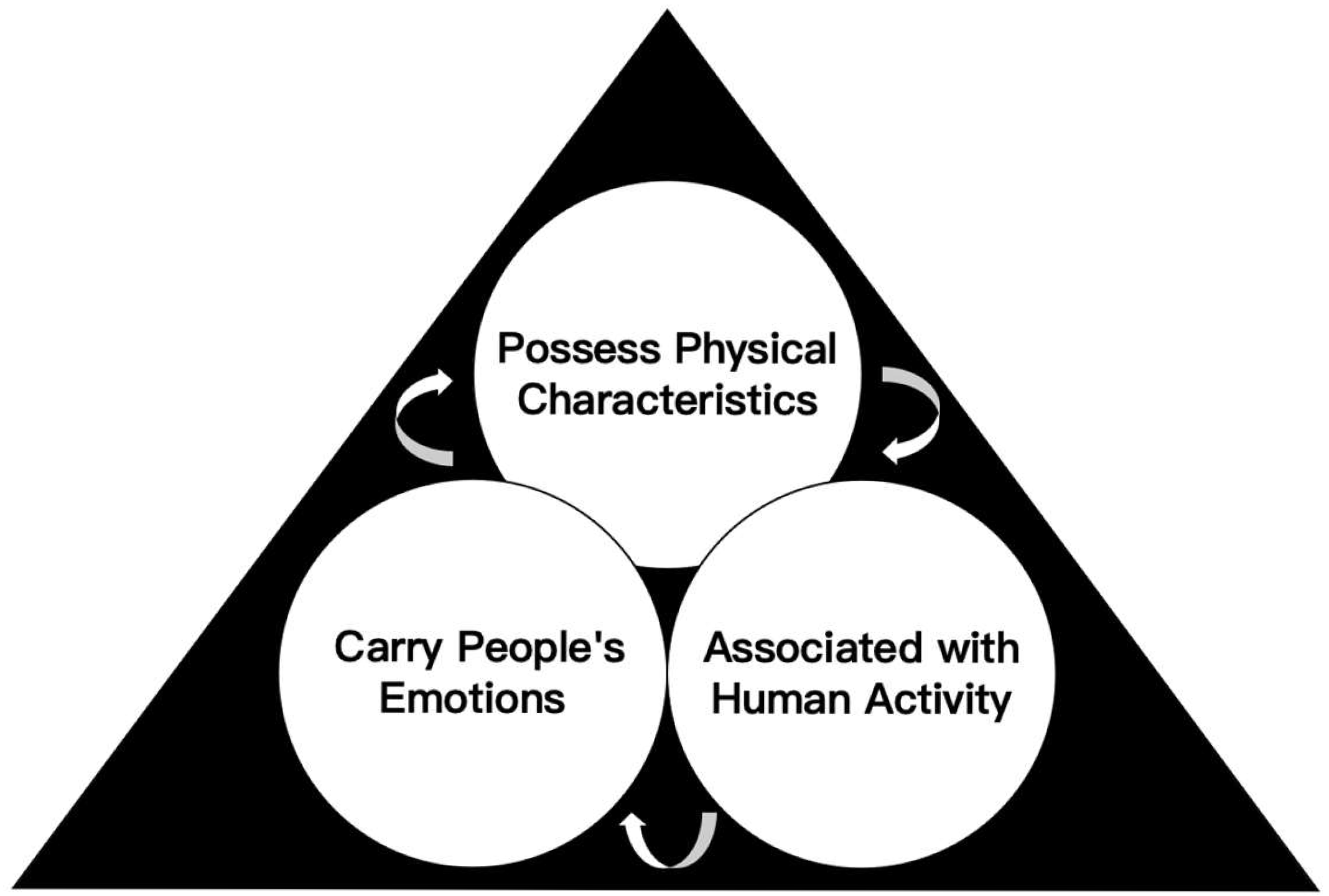

Motivated by rapid global urbanization and the rising tourism economy, the mission to protect and revitalize architectural heritage thus requires the simultaneous conservation of historical authenticity and contemporary functional requirements. Historic districts and traditional dwellings are the material witnesses to urban cultural memory, and they keep the collective memories of local civilizations. They are today highly important cultural tourism spaces in contemporary urban renewal. This is particularly noticeable in Macau’s historic district. Having a complete historic district listed on the World Heritage List [

1], the Macau Historic District comprises 22 historic buildings and eight squares [

2]. As a unique symbol of Chinese–Portuguese cultural integration, it is also an important service bearer of Macau’s cultural economy. The statistics by DSEC indicate that Macau rebounded to 85% of the pre-pandemic level in 2023 in terms of visitors, and cultural heritage spaces are part of the attraction. In addition, the Historic Centre of Macao celebrates the twentieth anniversary of the inscription of the property on the UNESCO World Heritage List. To explore the social value of heritage from the tripartite perspective of historical context, physical environment, and cultural sustainability, the Macau Special Administrative Region (SAR) Government has actively engaged the local higher education institutions to study together. With this academic mandate as my ground, I approach this research using a three-method approach to analyze (1) operationalizing the Genius Loci theory into an evaluative matrix for evaluative heritage landscapes in Macau, (2) diagnosing visitor experience gaps in visitor experience with evidence-based solutions through Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) modeling at the UNESCO-listed Mandarin’s House, and (3) synthesizing theory, policy, and operational evidence into evidence-based intervention protocols for sustainable heritage revitalization.

The spatial creation of built-heritage sites is confronted by three principal challenges: (1) the diminishing of Genius Loci erodes the cultural atmosphere, thereby jeopardizing Christian Norberg-Schulz’s “Existential Space” theory through the encroachment of over-commercialization [

3]; (2) the disjunction between the preservation of material heritage and the inheritance of intangible culture disrupts the spatial narrative, impeding the formation of a cohesive cultural-perception chain; and (3) the discord between evolving tourist-experience demands and traditional display methods creates structural dilemmas in integrating modern functions while preserving historical context.

In Macau’s historic district, the burgeoning trend of “Musealization” and the homogenization of commercial spaces have emerged as pressing research issues. These challenges underscore the profound responsibility of such sites, steeped in history, to reflect historical narratives, promote cultural values, and educate the public. The cultural atmosphere of these sites directly shapes visitors’ experiences. However, many currently suffer from a lackluster cultural atmosphere, an underemphasized Genius Loci, and suboptimal tourist experiences in their spatial creation.

This research endeavors to catalyze a paradigm shift from “Physical Space” to “Cultural Field”, a transformation essential for the sustainable development of Macau’s cultural heritage. By diagnosing visitor experience gaps through empirical data analysis, the study eschews prescriptive policy advocacy. Instead, it focuses on systematically identifying spatial performance discrepancies rather than proposing definitive governance frameworks. This methodological stance ensures that the research remains objectively grounded in observed phenomena while inviting contextual adaptation of findings by heritage management stakeholders.

3. Methods

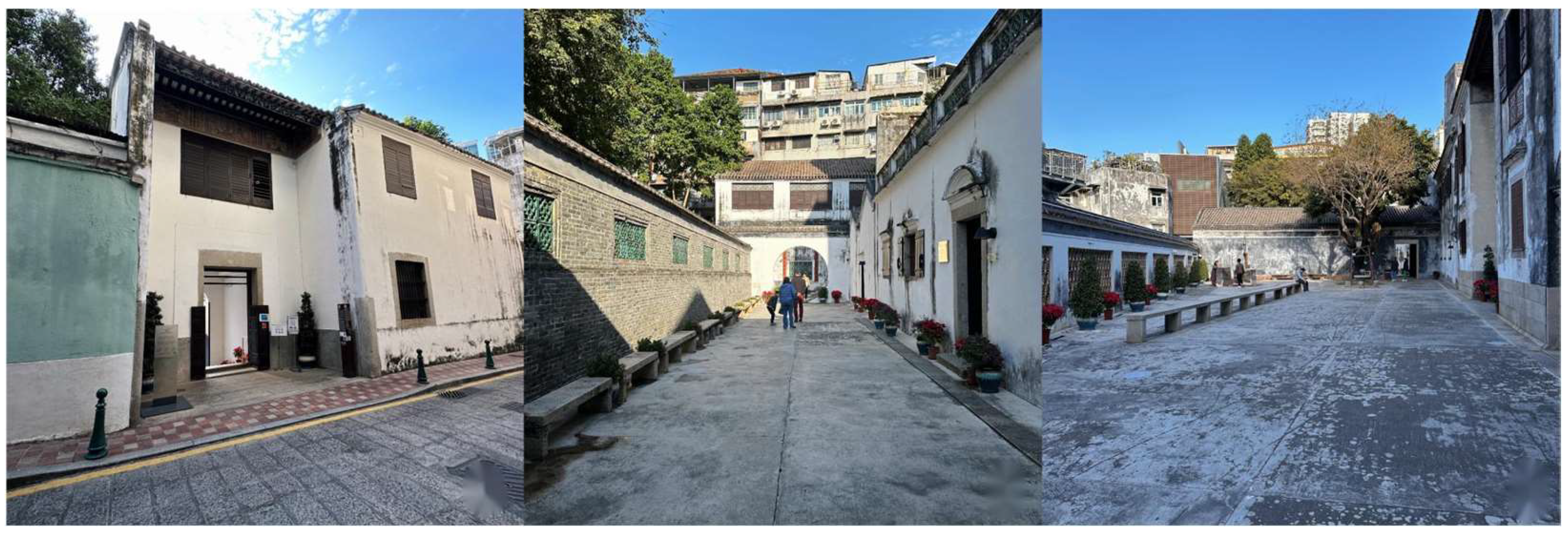

This research utilizes Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) to investigate visitor evaluations of spatial elements in architectural heritage spaces, with the Mandarin’s House in Macau serving as the case study. The research examines four key dimensions: spatial perception, cultural identity, emotional engagement, and functional attributes. By systematically comparing visitor expectations with on-site experiences, the study identifies critical gaps that inform adaptive reuse strategies for historical buildings. The outcomes aim to balance heritage conservation with cultural tourism development in World Heritage cities, particularly in maintaining Genius Loci while enhancing visitor engagement.

3.1. Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA)

Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) is an evaluative technique that identifies priority areas for improvement by comparing the importance and performance of service or product features. Initially proposed in 1977 [

36], IPA has been widely applied across various fields, including tourism management, service satisfaction, product performance, and place attractiveness, for quality improvement and strategy optimization [

37]. It primarily analyzes the discrepancy between respondents’ perceived importance and the objective performance of the subject, evaluates satisfaction, and predicts optimization strategies [

38]. Existing research has confirmed the feasibility of the IPA model in researching users’ perception of spatial environmental elements [

39]. Through this theory, it has been found that the satisfaction level of respondents’ spatial evaluation can be obtained by using “Likert Scales” to have respondents evaluate both the performance and importance of spatial elements simultaneously [

40].

The ‘x-axis’ for the IPA quadrant consists of importance, and the ‘y-axis’ has satisfaction, forming four quadrants on the basis of the mean values of importance and satisfaction [

41]. The Mandarin’s House belongs to quadrant Ⅰ, which is the area with high importance and satisfaction, the ‘Strength Development Area’. The “Continue to Maintain Area” is in quadrant Ⅱ, which has low importance and high satisfaction. Quadrant Ⅲ, the “Opportunity Expansion Area”, is the place where you have low importance and satisfaction and, therefore, can be given lesser priority. The “Urgent Improvement Area” is quadrant Ⅳ, characterized by low satisfaction and high importance, which should be a development breakthrough point, as improvement will be significant to stimulate visitors’ experience and needs to be paid attention to and improved immediately. The analysis of strengths and weaknesses of the sense of place elements of the Mandarin’s House offers directions and feasibility for the improvement of the sense of place expression.

Subheadings should be optional in this section. The experimental results should be described in a concise and precise form, supplemented with interpretation and what can be drawn from experimental conclusions.

The Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) method was used to quantitatively compare and analyze the indicators based on the application of the adjusted evaluation index system [

42]. This research also combined the IPA method to collect data through questionnaires. In terms of the development performance of Mandarin’s House, their satisfaction from the visitors’ perspective was taken as the place spirit, and the visitors’ perceived importance of Genius Loci elements was regarded as a factor affecting satisfaction. A comprehensive evaluation was performed on the collected data. The research offered a basis for improving visitors’ experience by contrasting the two dimensions and presenting them in a visual form of an IPA quadrant. With this approach, descriptive analytics is given prioritized importance over normative recommendations, and the performed analysis maintains fidelity with what is actually perceived by the visitor and resident communities and prevents prematurely guiding spatial interventions.

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

The field survey employed a hybrid sampling strategy that combined stratified random sampling with purposive techniques to ensure representativeness. This approach aimed to evaluate visitor perceptions of the spatial quality of the Mandarin’s House, with the dual purpose of informing adaptive reuse policies and enhancing heritage conservation strategies through targeted spatial optimization. To achieve representative sampling, respondents were categorized by visitor type, including tourists, local residents, professionals, students, and others.

Data collection took place at three key locations, each utilizing distinct sampling strategies tailored to the context: (1) Entrance/Exit Areas: Systematic random sampling was implemented during open hours (10:00–16:00), with researchers approaching every fifth visitor using a predetermined interval method. This ensured that immediate post-visit impressions were captured while minimizing selection bias (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) (Reference: (INSTITUTO CULTURAL OF MACAU) Ground/First floor plan of Mandarin’s House:

https://reurl.cc/OYj2rR, accessed on 26 December 2024) (Reference: (CULTURAL HERITAGE OF MACAO) Mandarin’s House VR:

https://reurl.cc/NY424m, accessed on 26 December 2024); (2) Guided Tour Routes: Purposive sampling targeted participants in guided tour groups to actively engage visitors demonstrating intentional cultural exploration; (3) Surrounding Public Spaces: Convenience sampling was employed during non-peak periods to include casual visitors and local residents, with researchers recruiting available participants to broaden geographic and behavioral diversity.

The survey was conducted between 18 December 2024 and 5 January 2025, excluding Wednesdays when the site was closed. Over 16 days, trained researchers distributed questionnaires both on-site and online, targeting diverse visitor demographics. To minimize selection bias, every fifth visitor entering the site during open hours (10:00–16:00) was approached, while non-peak hours utilized convenience sampling. Online surveys were disseminated via Macau tourism platforms and social media groups to ensure broad geographic and temporal coverage.

3.3. Research Design Framework

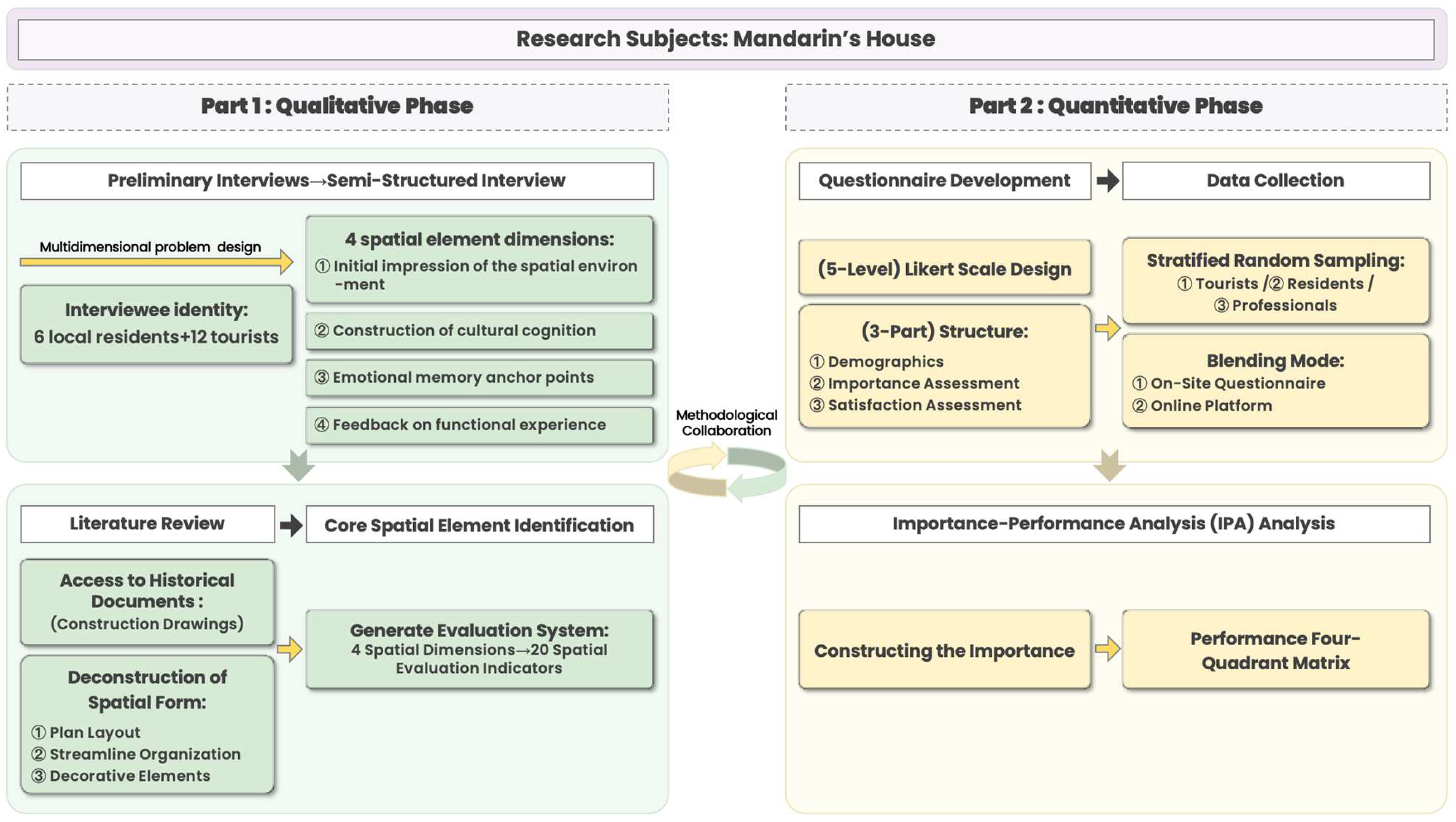

The research framework primarily describes the systematic integration of qualitative and quantitative methods (

Figure 6). The qualitative phase (left) encompasses semi-structured interviews and archival analysis to identify core spatial elements of cultural heritage, while the quantitative phase (right) utilizes Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) to evaluate visitor satisfaction.

3.4. Preliminary Interviews and Questionnaire Development

A preliminary interview conducted as a widely used method of data collection [

43] improves the objectivity and credibility of the research. The researchers then laid a foundation to set up an evaluation criteria system (

Table 2) by conducting preliminary interviews from the dual perspectives of tourists and residents (

Table 2).

A commonly used data collection measure is preliminary interviews, which have a way of increasing the objectivity and credibility of research. After that, the researchers carried out preliminary interviews with both tourists’ and residents’ perspectives as the basis for the construction of an evaluation criteria system. A comparative analysis was performed by conducting on-site interviews with 6 local residents and 12 tourists, with an attempt to understand the differences between the two user groups’ views on the Mandarin’s House. The analysis of the experimental hypothesis also revealed there were significant differences in the categories of concern, along with the experiential perceptions between the two user types. On the one hand, local residents cared more about the daily convenience-oriented activities of the Mandarin’s House, while on the other hand, tourists stressed more the convenience of service facilities and the aesthetic quality of the landscape and architecture and asked for more historical and cultural value. Interviews with local residents during the on-site research on the Mandarin’s House show that the area around it has become well known to tourists, and the place has practically turned into a commercial street. As a result, the perspective of the needs of local residents is also a very important source for this research.

In accordance with the foregoing evaluation indicators, Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) was employed to systematically assess place identity dimensions of the Mandarin’s House. Research was performed focusing on investigating variations between visitors’ importance evaluation of space and satisfaction levels, so that place elements that are missing can be identified and how they may have a role in place perception.

The importance and satisfaction with the spatial quality of the Mandarin’s House were based on the evaluation that was performed on the basis of a 5-point Likert scale. The structured questionnaire was made up of three parts.

(1) Gender, age, education level, identity, and purpose of visit (demographic information).

(2) Genius Loci elements pre-visit importance evaluation using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘very unimportant’ to 5 = ‘very important’).

(3) Evaluating post-visit satisfaction of spatial quality through a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’).

The sample included a total of 320 questionnaires distributed, from which there was a response rate of 98%, with 313 returned. After clearing data, 306 valid questionnaires were obtained, with a valid response rate of 96%. These are all valid questionnaires, which will form an important basis for further research.

4. Research Results

4.1. Data Result Analysis

An analysis was conducted on the demographic variables of the formally collected samples, which included seven aspects: gender, age, education level, identity, length of residence, purpose of visiting the Mandarin’s House, and whether they had previously visited similar architectural spaces. Among the 307 valid respondents, 158 were male (51.5%) and 149 were female (48.5%). In terms of age distribution, respondents aged 26–35 accounted for the largest group with 123 individuals (40.1%). Regarding education level, 207 respondents (67.4%) held a university or college degree. Most respondents (75.9%) had lived in the area for less than a year. As for the purpose of visiting the Mandarin’s House, 30.9% came to watch festive activities, and 24.8% for artistic and cultural appreciation. Additionally, the majority of the sample (79.5%) had previously visited similar architectural spaces (

Table 3).

Notably, the stratified sampling framework specifically separated the tourist (60.3%) and resident (13.0%) responses. Divergent priorities were found using subsequent subgroup analyses. Both tourists (D5) and residents (B3) attribute more emphasis to functional attributes such as clarity of signage and intangible cultural continuation, respectively. Distinctions of these kinds provide justification for the methodological choice to combine the two cohorts so that the heritage space performance can be evaluated in its entirety.

There were a total of 307 valid questionnaires collected, of which 56.4% of the sample were young adults, suggesting extreme age bias in the population surveyed. Moreover, the timing of the survey over the Christmas and New Year holidays meant that the participants tended to be tourists and students on holidays. Statistical analysis showed that the time of survey distribution significantly affected the visitors’ purposes: most of the visitors visited the Mandarin’s House to join in the festival activities, especially for visitors from Hangzhou city.

As a visitor group, from the perspective of visiting motivations and behaviors, the youth demographic is the key group, while foreign tourists and international students are mainly for short visits motivated by the desire to appreciate historic culture and experience local traditional ones. However, local residents visit mainly during periods corresponding to festival cultural events, and it is unusual for them to visit for common sightseeing during non-festival periods.

Based on the sample data, current statistical facts are showing two opposite tendencies: (1) To decline the Mandarin’s House in the locals; and (2) to arouse the interest in the historical architectural spaces and growing demand from foreign visitors visiting them. However, this situation highlights the need to improve the physical and spiritual properties of the mansion. To draw in foreign tourists sustainably and reengage local residents, it is indispensable to significantly improve the physical features and spiritual connotations of the cultural heritage space so that it can become a dynamic historical and cultural experience space that is enduringly attractive.

However, it should be noted that the sample comprised six respondents (2.0% of the total sample) who had primary school education or lower. From cross-referencing with age distribution data, it is found that three respondents fell into the under-18 group (27.3% of the minor subgroup) and the remaining three into the 46+ age group (9.7% of this age cohort). This implies there are many possible scenarios: The lower educational attainment of younger respondents may be due to not having finished their education, while older adults may have been limited in what they could attain educationally for historical reasons. However, this subgroup represents a small proportion of the sample, and differences in cognitive maturity and education may be potent latent influences on cultural evaluation of cultural space perception. This helped to reduce the potential of bias, and the research validated the consistency of the response of the low-education respondents by semi-structured interviews that found absolutely no significant contradiction to the general trends that emerged. Educational attainment appears to modulate heritage space evaluations by influencing priorities, processing of information, and affective processes; therefore, future research should seek to strategically analyze these effects by stratifying the analyses by educational attainment.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2.1. Reliability Analysis

This research uses the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to test the reliability of the questionnaire, which has been widely used in empirical data analysis [

44]. In general, if the Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale designed in the questionnaire is even lower than 0.7, it means that the internal consistency of this scale is poor, and the scale needs to be redesigned. It means that if the Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale is greater than 0.7, then the internal consistency of the constructed multiple variables for this scale is good [

45].

Furthermore, the reliability of individual question items is measured with the CITC (Corrected Item-Total Correlation) [

46]. The following two conditions should be met when it is time to delete the question item in the research: a question item has Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) less than 0.4; after deleting a question item from the scale, the Cronbach’s coefficient alpha value of the scale is greater than that of the corresponding dimension.

(1) Reliability Test of Satisfaction

From the Cronbach’s alpha results of each dimension of the architectural space evaluation and recognition of Mandarin’s House in the Table, the Cronbach’s alpha values of the four satisfaction dimensions designed in this research are 0.937, 0.847, 0.895, and 0.950. The internal consistency reliability of each scale dimension reported is greater than 0.7 (

Table 4), which confirms good internal consistency reliability for each scale dimension. This makes sure that the survey results are highly reliable.

In addition, the values of the Corrected Item-Total Correlation values (CITC) and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients calculated after iteratively purifying each dimension by sequentially removing individual items met the research’s requirements. Poorly fitting items (CITC < 0.5) and constructs with insufficient reliability (α < 0.7) were eliminated. These findings collectively demonstrate that the data of the evaluation of the architectural space and recognition of the Mandarin’s House passed the reliability test.

(2) Reliability Test of Importance

The Cronbach’s alpha values for the four dimensions of architectural space importance assessment in the Mandarin’s House are presented in Table X. Specifically, the reliability coefficients for the dimensions are 0.839, 0.865, 0.837, and 0.899, indicating strong internal consistency across all constructs. In addition, on internal consistency reliability for each scale dimension, all values exceeded 0.7 (

Table 5). This attests to the high reliability of the survey results.

Moreover, CITC values and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were obtained after removal of each of the items in all dimensions, conforming to the research requirements. The items consistently measured the same constructs, and no items needed to be deleted. Taken together, the findings testify that the data on the architectural space evaluation importance of the Mandarin’s House passed the reliability test.

4.2.2. Validity Analysis (Factor Analysis)

In this research, interviews with visitors were carried out in depth before the questionnaire design by reference to the previous research and relevant theories. For the purposes of the evaluation, it considered the context of the Mandarin’s House spatial, including the perspectives of visitors, and identified four evaluation dimensions (A: spatial perception; B: cultural identity; C: emotional experience; D: functional features) and 20 spatial evaluation indicators (

Table 6).

The four dimensions represent the spatial physical as well as sociocultural attributes and their emotional connections and memories with one another, manifested through spatial interaction. The three categories are distributed among 20 indicators. These can be classified as spatial physical attributes (spatial environment, characteristics, layout, scale, and decoration), functional characteristics (visit routes, order, interpretation, facilities, and signage), and emotional experience (spatial value, local features, culture, innovation, and era-specific characteristics, display content, spatial feeling, visitor mood, atmosphere, and connection).

(1) Validity Test of Satisfaction

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to examine the construct validity of the questionnaire data. To ensure that the designed variables are qualified for factor analysis, the “Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin” (KMO) test and “Bartlett’s Test” of Sphericity were performed prior to the factor analysis. Relevant researchers believe that criterion: the acceptable KMO value (≥0.7) is suitable for factor analysis. Secondly, principal component analysis (PCA) takes place to extract common factors from the original indicators. However, the factors explain (≤60%) of the variance when the factor eigenvalues were equal to or greater than one, which will be considered an operational indication of good construct validity. It has finally been established that orthogonal rotation with Varimax is performed in order to construct a rotated component matrix for the identification and naming of factors. The ideal scenario is when all items load (>0.5) on the corresponding factor and none of the items load (>0.4) on more than one factor. Any items we had that violated this criterion were considered for deletion.

The KMO value of the architectural space evaluation scale of the Mandarin’s House was 0.910, which is more than the criterion of 0.7 (

Table 7), meeting the standards for factor analysis. Factors were extracted with eigenvalues (>1) using principal component analysis (PCA). Further tests of the quality of factors extracted were performed, and the total variance explained by the four extracted factors is 74.368%, exceeding the recommended 60% threshold. This illustrates the acceptability of the construct validity of the satisfaction measurement model.

Overall, the rotated component matrix of factor loadings matched the theoretically derived dimensions. There were no cross-loadings (>0.4), and all items loaded (>0.5) on their respective factors (

Table 8). The results validate the use of the scale to fulfill subsequent analytical purposes, since its high validity has been confirmed.

The method of principal component analysis was used to obtain factors where the eigenvalues are greater than one from the scale. The four factors with eigenvalues greater than one can be seen in the results of the total variance explained by each dimension of the evaluation and recognition of the architectural space of the Mandarin’s House. The four factors explained a total variance of 74.368%, which is more than 60% (

Table 9). It could be concluded that the degree of explanation about the evaluation and recognition of the architectural space of the Mandarin’s House in this paper is relatively high.

(2) Validity Test of Importance

According to one of the methods of important architectural space evaluation, the Mandarin’s House KMO value is 0.918. Since it is greater than 0.7 (

Table 10), the KMO value of the questionnaire data on the importance of the architectural space evaluation of the Mandarin’s House in this paper conforms to the requirement of factor analysis.

To extract factors with an eigenvalue greater than one, the scale was fed as an input to principal component analysis (PCA). With eigenvalues (>1), four factors were derived from the Mandarin’s House architectural space evaluation, explaining the total variance importance, which was 64.854%, which exceeded the required 60% (

Table 11). The findings above indicate acceptable construct validity for the importance measurement model.

In summary, the rotated component matrix of factor loadings for the questionnaire data on the importance of architectural space evaluation of the Mandarin’s House in this research shows results that are compatible with the suggested scales and dimensions in the design of the research. We can further observe that the loading values of the items regarding each dimension of the importance of the architectural space evaluation of the Mandarin’s House are greater than 0.5 (

Table 12). Accordingly, the questionnaire for assessing the importance of the architectural space of the Mandarin’s House holds high validity in this research, which means that it is effective and suitable for the following research and analysis.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Hypothesis Testing

Descriptive statistics of the means of items pertaining to each of the satisfaction variables reveal that the means of items for the satisfaction of spatial evaluation of the Mandarin’s House in this research varied from 2.81 to 3.88. The recognition for the visiting route, visiting sequence, and guided tour explanations was relatively low, while the recognition for the regional features, local culture, and cultural innovation of the Mandarin’s House was relatively high.

Furthermore, following the descriptive statistical results of the means of the items pertaining to each variable of importance, the ranges of the means of the items of the importance of the spatial evaluation of Mandarin’s House in this research fall between 3.81 and 4.18 (

Table 13). Therefore, the participants’ evaluation level for the importance of various indicators of the Mandarin’s House is at a relatively high level. In particular, they pay the most attention to the visiting mood, connection to the space, and exhibition content.

From the on-site investigation, the researchers can ascertain that the Mandarin’s House is an example of a hybrid architectural style, combining Chinese courtyard arrangement with Portuguese ornamentation. Significant spatial parameters like A1 (courtyard connectivity) and A5 (ornamental carvings) have been visually documented. The significance of these features lies in the way they show the interplay between material heritage and cultural symbolism that informs visitors’ Genius Loci. Nevertheless, the current site layout (

Table 3) exhibits challenges of functional incoherence in the form of fragmented circulation paths (D2) and insufficient interpretive signage (D5).

4.4. Paired Samples t-Test Results

The significant differences in satisfaction ratings and importance scores in the spatial evaluation of the Mandarin’s House architectural spaces were further studied with a paired-sample

t-test (

Table 14). The results reveal that the satisfaction ratings were systematically lower than the corresponding importance scores within this architectural assessment. In particular, there were no statistically significant differences (

p < 0.05) in satisfaction and importance ratings between regional distinctiveness, local cultural expression, and cultural innovation. On the other hand, differences emerged in the following domains, which were statistically significant (

p < 0.05). They provide viewers with spatial environment, spatial characteristics, spatial configuration, dimensional scale, ornament elements, spatial value, temporal attributes, exhibition content, perceptual experience, viewer affect, ambient quality, spatial connectivity, circulation path, visitation sequence, interpretive narrative, facility provision, and wayfinding system. In all of these dimensions, the evaluation of satisfaction was substantially lower in comparison to their perceived importance.

The mean scores of the importance and satisfaction of the visitors to the spatial element indicators, the difference between (P)and (I), the “T-value”, and the results of the paired samples

t-test were obtained using “SPSS 27”. All fourteen of the indicators reached the significance standard (

Table 2), allowing their analysis.

With regard to the space of the Mandarin’s House, the mean scores of visitors’ perceived importance in the space vary from 3.81 to 4.18, near the mean of “important” (four points), suggesting that the expectation level of the interviewed visitors to the visiting experience in the Mandarin’s House is fairly high. The interviewed visitors give relatively high importance values to the three spatial elements of (C3, C5, and A1) among the six selected ones, signifying that while visiting the Mandarin’s House, the interviewed visitors may respond relatively more to the creation of the physical spatial environment, the narrative rhythm of the visiting process, and its own visiting mood in the space. On the contrary, the importance scores of (D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5) are relatively low. This shows that the experience facilities in the space of Mandarin’s House, as mentioned by the investigated visitors, do not have much impact on how sensitive the interviewed visitors are to the visiting experience.

The mean scores of the visitors’ perceived satisfaction of the space measured in the Mandarin’s House span from 2.91 to 3.88 and vary in a range around “average” (three points) and slightly below the level of “satisfied” (four points), meaning that the interviewed visitors were not completely satisfied with their visiting experiences and identities of places in the Mandarin’s House. The satisfaction scores for dimensions (B4 and B2) were relatively high compared to other dimensions. The scores of satisfaction for (A3, D1, D3, and B1) are relatively low. Analysis of the interviewed visitors’ input reveals that the spatial treatment and current situation of the Mandarin’s House have not met the needs of the visitors. The shaping of the display space and the visitor experience in the Mandarin’s House especially requires substantial improvement.

5. Research Discussion

This research uses Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) to structurally analyze visitors’ place perception at the Mandarin’s House based on the above-mentioned evaluation data indicators and consequently distinguishes the discrepancies in visitors’ pre-visit and post-visit satisfaction evaluations. This thesis aimed at discovering the missing spatial elements and the roles they would play in redefining the place identity in the heritage space. Key findings include the following:

An IPA quadrant diagram of visitor satisfaction scores plotted against importance scores was used to schedule and prioritize optimization strategies for spatial elements of the facility from the visitor’s point of view. However, the origin of the coordinate (3.42 for satisfaction, 4.00 for importance) was set at the mean. The categorized indicators were placed into one of four quadrants based on the respective importance (I) and performance (

p) values (

Figure 7). By doing this, this analytical framework also expounds on critical gaps of perceived significance and real performance, which allow for more actionable intelligence when it comes to improving the Genius Loci expression and supplementing functional deficiencies in adaptive reuse practices.

The socio-demographic analysis of the above research, combined with this, shows that the visitors are mostly young adults (40.1% aged 26–35) and tourists (60.3%), with (67.4%) holding tertiary education. Favoring event-driven engagements, this cohort prioritized festival participation (30.9%) and cultural-artistic experiences (24.8%) (

Table 3).

Although functional deficiencies in spatial navigation the mismatch of high educational expectations with static exhibition methods was supported by the high rate of interpretive clarity (D3: 2.91) and interpretive clarity (2.94) (13.0%), local residents engaged with the site on a limited basis outside of festival periods as a result of commercialization of the site for tourism purposes, which is a risk for loss of authentic cultural connections. Further interviews indicated the homogenization of adjacent parts into tourist-centric zones, inimical to the Genius Loci integrity, which necessitates balancing visitor services with community-oriented spatial practices for sustainability.

The first quadrant (where the development should be advantageous) indicates that the scores of importance and satisfaction are high in the area. That consists of the (C3, C4, C5, and A2) spatial evaluation indicators. For the establishment of the spirit of the Mandarin’s House space in this area, these five indicators can be said to be relatively important, and satisfaction is relatively high. Nevertheless, the actual mean satisfaction score is inferior to the mean importance score; therefore, the visitors are still not surprised by the overall poor service. As such, these spatial elements also reflect the essential requirements of the visitors to the exhibition space and must be given meticulous attention. Improving spatial shaping would improve comfort. By changing the pattern of the current spatial image of the Mandarin’s House, as well as increasing the number of exhibits, a new type of folk-cultural exhibition space can be formed, and the perception of its regional characteristics can be raised. The artistic conception is enhanced by appeal and shock, and by reforming the spatial division or guidance, as well as the mode of exhibition, an immersive experience can be achieved. At the same time, spatial inclusiveness can be improved, the types of exhibits can be expanded, and the emotional shaping points can be magnified to improve upon the spiritual experience of visitors.

There is a large gap between the visitors’ expectations and the actual satisfaction of these two evaluation elements (A1, A3) in this area. These spatial elements are also the fundamental needs of visitors in the exhibition space, and improvement is needed in a rush. Improving spatial shaping would improve comfort. By changing the current spatial image of the Mandarin’s House and expanding the types of exhibits, a unique folk culture exhibition space can be built in order to emphasize the perception of regional characteristics. While changing the spatial division or guidance and the exhibit display mode could enhance the attractiveness and shock of the artistic conception, they can also form an immersive experience. Meanwhile, the spatial characteristics of inclusiveness can be added, the category of exhibits can be increased, and emotional shaping points can be amplified to augment the spiritual experience possessed by visitors. The Table listed above shows the significant differences between the importance and performance (satisfaction) of both evaluation elements.

According to the analysis principle of IPA, it can be inferred that these six evaluation elements (A3, A4, and C1) belong to this quadrant (the area for continued maintenance) and are relatively important for the place perception of the Mandarin’s House, and the perceived performance is relatively high. Nevertheless, the actual mean satisfaction score is lower than the mean importance score, meaning that it does not surprise the visitors overall and offers a relatively perfect experience, which can still be improved. Furthermore, (C3) visiting mood’s importance and performance (satisfaction) scores are high among them, indicating that the visitors have the highest demand for and are the most satisfied with the positive experience of the visiting mood.

The five evaluation points (D1, D2, D3, B1, and B5) for the three exhibit spaces (in the third quadrant: the space for opportunity expansion) of the Mandarin’s House are all the potential opportunities for efficient development of the exhibits. The values of importance and performance in scores are relatively low. Further, all four elements’ importance scores for these values are higher than the performance scores. Consequently, visitors also have certain expectations for them, but the actual content of the venue does not fulfill these expectations. Consequently, these four evaluation elements leave much room for improvement. The performance (satisfaction) score of the D2 visiting sequence is the lowest, and the importance score of the D1 visiting route is also the lowest.

With regard to these four evaluation elements (D4, D5, B2, and B4), they are in the fourth quadrant (the area in urgent need of improvement), which means that they are relatively important but perform relatively poorly. However, from the perspective of individual spatial elements, actual importance values are still higher than those of performance (satisfaction) values.

As such, there is still some room for improvement and optimization. Improvement of the content, space, and human-centered experiences can be improved based on a better expression of the place spirit, which amalgamates the existing advantages, such as historical and cultural displays and spatial visiting experiences.

Based on the empirical findings, this research synthesizes gaps in prioritized improvement areas and proposes strategic directions for future intervention to improve visitor experience at the Mandarin’s House. The analysis specifically points to critical gaps in spatial narrative continuity, functional adaptability, and cultural memory activation that contribute to an incapability of deploying Genius Loci.

(1) Improving the Material Experience of Display Spaces [

47]

Based on the research, spatial layout and the visitor’s experience within the Mandarin’s House are found to be critical areas that need improvement. Specifically, if the physical space provides a bad experience of experiencing the architecture, the space, and the exhibits, it becomes less likely that the visitors will provide feedback. As a result, the sense of place and the spirit of the place diminish as there is no human involvement. Being immovable properties, cultural heritage buildings demand to imbue their visitors with a sense of order and logic within their spatial environment in order to enable their visitors to understand and appreciate the cultural value of the heritage architecture.

(2) Enhancing the Unique Regional Characteristics of Display Spaces [

48]

The expression of the spirit of place also involves regional characteristics and how the spirit of place is reflected both in the exhibit content and the spaces therein. Despite the fact that the Mandarin’s House often hosts events promoting traditional local culture, visitors are often unsatisfied with the experience within a short period of time. Accordingly, the research proposes that although exhibits and specialty pavilions can manifest local cultural properties, the depth in terms of history and the scope in terms of time may impede emotional resonance. Using distinct spatial connections, specially designed interiors, and other local cultural traits can help achieve a stronger regional expression.

(3) Ensuring Continuous Development of the Display Space Experience [

49]

A sense of place is not manifested only in the interior exhibition spaces. If outdoor areas such as a courtyard, corridors, souvenir shops, and rest areas are capable of sharing the unity of the Mandarin’s House space, the visitors’ interaction with the space will be extended. This gives the visitors longer pauses for interaction so that they can engage more deeply with the content to be conveyed by the space. There needs to be a way to introduce innovations in the visitor experience, for example, in the form of interactive exhibitions, multimedia information points, themed lectures, and workshops, where the visitors can also participate in the experience. Thoughtful design can be extended into the spaces in which it exists and can make the original space more desirable.

(4) Enhancing Visitors’ Spiritual Experience [

50]

On the one hand, the research indicates that visitors’ spiritual engagement is rather poor. On the other hand, in order to cultivate local awareness of their cultural identity, cultural outreach requires the use of physical parameters in the courses of pathways and audiovisual elements to elicit emotions in visitors. Streamlining information acquisition is, on the other hand, vital. Setting this information points along the flow to visitors gives them a sense of gain. In addition, an inviting spatial atmosphere and content display can influence visitors’ moods, causing the visitors to feel happy, sad, and so forth, and thus, the positive significance plays a role in forming the spirit of place.

In this research, the proposed adaptive management framework aligns with Remoaldo’s call for iterative stakeholder engagement as well as responding to Strategic Tourism Planning and Place Identity in Heritage Spaces in the literature review section. For example, participatory workshops with Macau residents and tourists could be organized in the context of the “Diagnostic Phase” to collect data mapping perceived gaps in cultural narrative continuity at the Mandarin’s House. Semi-structured interviews with visitors confirmed these findings of frustrated visitors accusing fragmented storytelling (

Table 2) as an example. Through this process, however, the “Co-Design Phase” should more actively engage in community-based interventions like recapturing the mansion’s residential roots in a “72-family tenancy” experience that allows material preservation and intangible heritage activation to coexist while creating new forms of commerce for Narragansett Bay’s visitors. Lastly, in the “Monitoring Phase”, feedback systems (like IoT sensors measuring visitor flow or sentiment analysis of visitors via social media) must be embedded in order to dynamically adjust the spatial interventions. An approach of this kind meets the IPA’s identified urgency for improving functional attributes (

Table 14) and mitigates the risks of “musealization” by keeping heritage spaces as living fields of cultural practice.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Research Summary

The cultivation of Genius Loci for cultural heritage buildings has an inherent spatial shaping propensity of informing important environmental narratives and fulfilling diverse user needs. This revitalizes the architectural space, making it a place full of culture, increasing its experiential value and sustainable development. The core aim is to move visitor engagement upwards, sustaining the historically authentic site of heritage, such as the Mandarin’s House in Macau, guaranteeing cultural survival and social significance.

IPA shows us how essential it is to pick strategic interventions that directly match up with the gaps in a given quadrant. Thus, for example, there is a need to upgrade the infrastructural pillars (Quadrant IV) of low functional satisfaction and narrative enrichment (Quadrant I) of the high-importance cultural elements. By targeting the approach, the optimization efforts address deficiencies, both immediate and long-term, as well as cultural sustainability. Through using the quadrant framework, stakeholders can identify which actions to take to create opportunities to accomplish visitor expectations with spatial performance, thereby increasing the Genius Loci expression of the Mandarin’s House.

Based on the visitor satisfaction with the architectural cultural heritage of Macau, with special reference to Mandarin’s House, there is a series of conclusions and recommendations we arrive at. Firstly, cultural heritage building spatial design generates the cultivation of a sense of place. This sense of place refers not only to the historical and cultural importance of the building itself but also to the emotional and cultural legacy and identity of its visitors. Consequently, this sense of place needs to be cultivated, as its enhancement will help present the space more attractively and, at the same time, meet the different demands from a variety of visitors, as well as inject more vitality and attractiveness into cultural heritage buildings.

The Mandarin’s House is hence an important cultural heritage site with rich historical information and a living social space in Macau. Being unique in architectural style and rich in cultural heritage places it within the ranks of strong candidates in cultural tourism. Still, the experience for visitors has some room for improvement. Therefore, some visitors of the Mandarin’s House are not able to fully understand the history and culture of the area due to the insufficient interactive experiences and the absence of a variety of interpretive services. Thus, future conservation and utilization strategies for the Mandarin’s House should pay more attention to promoting more engaging and interactive programs for the visitors.

Specifically, we propose to adopt multimedia displays and virtual reality technology to more vividly present the history, allowing the visitors to intuitively experience how the place witnessed historical changes and how the cultural connotations of the place changed over time. Moreover, the diversity of the given guided tours should be strengthened by providing multilingual explanations and customized experiential activities in accordance with tourists from different cultural backgrounds. For instance, there could be regular cultural workshops in which visitors can take part in the making of traditional handicrafts, thus making them closer to Macau culture.

In addition, the Mandarin’s House would be considered a means of exchange of culture and social interaction. Local residents and tourists could be pulled in for regular cultural exchange activities and exhibitions to understand the cultures of other people and integrate with different cultures. In addition to that, social media and online platforms ought to be exploited to the maximum so as to bolster the influence of Mandarin’s House in the international tourism market.

Furthermore, the principles of sustainable development, which must be guided by the conservation and use of cultural heritage buildings, should be used to direct the strategies for the protection and utilization of cultural heritage buildings. That is the only way for the visitor value of the Mandarin’s House to be genuinely increased, to accelerate the development of its non-urban heritage context, and to preserve this cultural treasure in modern society. We hope that our efforts to make the Mandarin’s House a cherished memory for visitors and a bridge between history and modernity, and culture and society, will succeed.

The Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) framework demonstrates that conservation strategies should be prioritized by quadrant, as there is an imperative for quadrant-specific strategies. Physical accessibility and service standardization are both required for an upgrade to suboptimal wayfinding systems (D2) and interpretative infrastructure (D3); however, these aspects are both critical performance gaps within quadrant IV. In contrast, while the cultural perception metrics are comparatively strong (A2, B4) in Quadrant I, needed curatorial enhancements to strengthen historical contextualization by adding a layer of coexisting narratives (e.g., multisensory exhibits) are necessary. The proposed stratified optimization framework universalizes synergistic resolution of the immediate operational deficiencies with maintaining the longitudinal integrity of heritage valorization.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Lacking doubt, this exploration gives important bits of knowledge to the evaluation of guestfulness at the Mandarin’s House, notwithstanding a few impediments. The first survey was conducted during the Christmas and New Year holidays (December 2024–January 2025), when there is a higher turnout of tourists and their travel is more likely to be motivated due to specific festival events. Second, if differentiating temporal bias, this temporal bias might influence visitor demographics and priorities, and may result in skewed results about visitor participation in short-term cultural events rather than regular heritage engagement. Second, the sample was overrepresented in younger adults (56.4% aged 18–35), which likely introduced a generational skew in the results that may limit generalizability to older or less technologically savvy people. Third, self-selection bias could emerge from the on-site and online survey placement methods in that people already with an interest in cultural heritage or already dissatisfied with current experiences may have been more likely to respond. These limits suggest caution in generalizing the results.

These gaps must be filled through future research via comparative and longitudinal approaches. Comparative studies with other built-heritage sites in Macau (for example, Temlo de A-Má or Largo do Senado) could examine whether the challenges and strategies identified are site-specific or part of a wider pattern. Moreover, longitudinal studies, which follow visitors’ satisfaction before and after introducing these proposed optimization strategies (e.g., enhanced spatial narratives or digital interactivity), would offer empirical evidence on how interventions would perform over time. This could be validated by expanded demographic diversity in sampling, in particular including elderly residents and international tourist populations. Finally, integrating mixed methods into the methods of visitor research—like real-time behavioral tracking or eye-tracking technologies—might yield more in-depth insight into visitors’ subconscious spatial element interactions.