Hydrothermal Surface Treatment of Mg AZ31 SPF Alloy: Immune Cell Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Potential for Orthopaedic Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Extract Preparation

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.4. Gene Expression Analysis

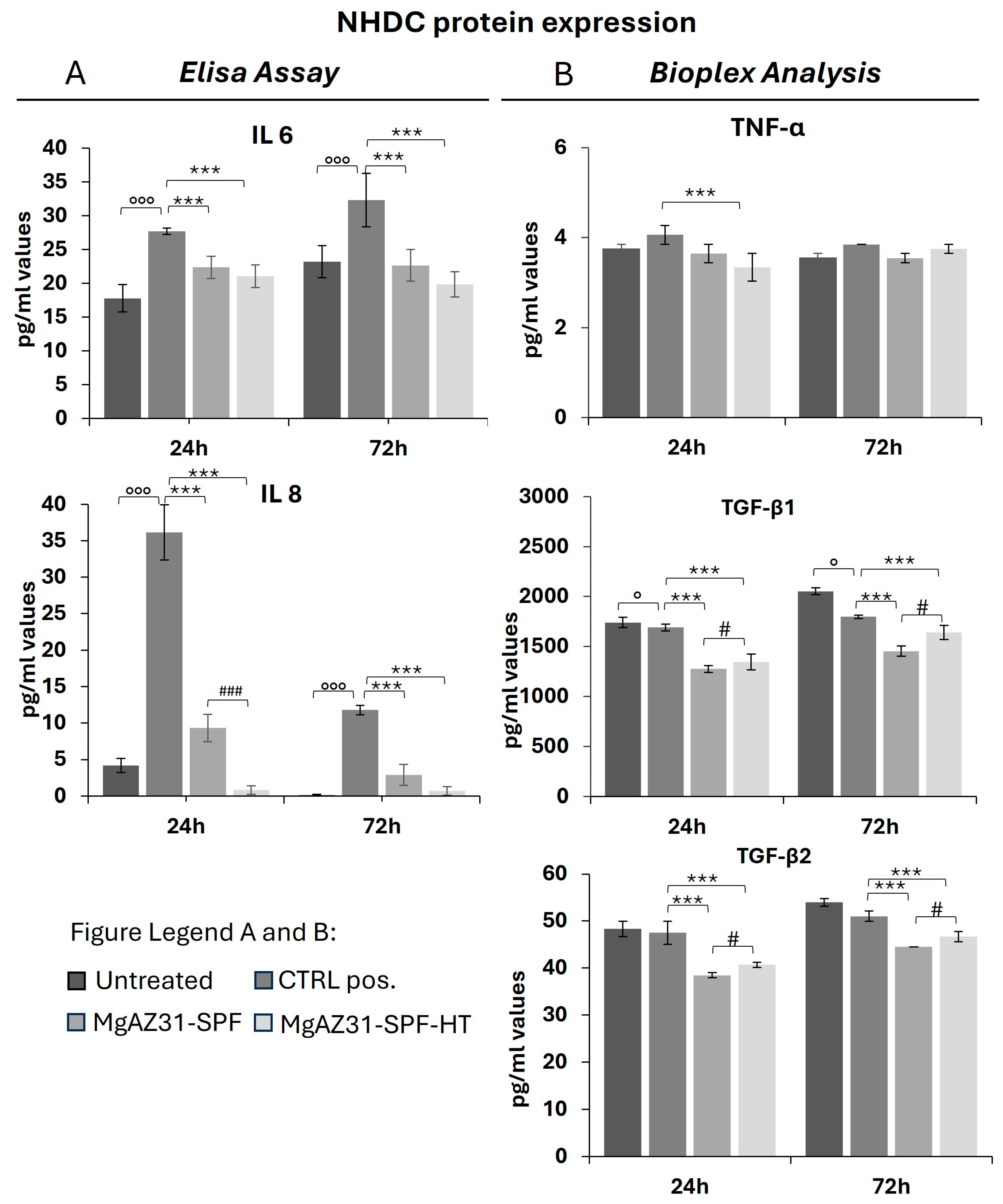

2.5. Protein Expression Analysis

2.5.1. Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.5.2. Bioplex Analysis

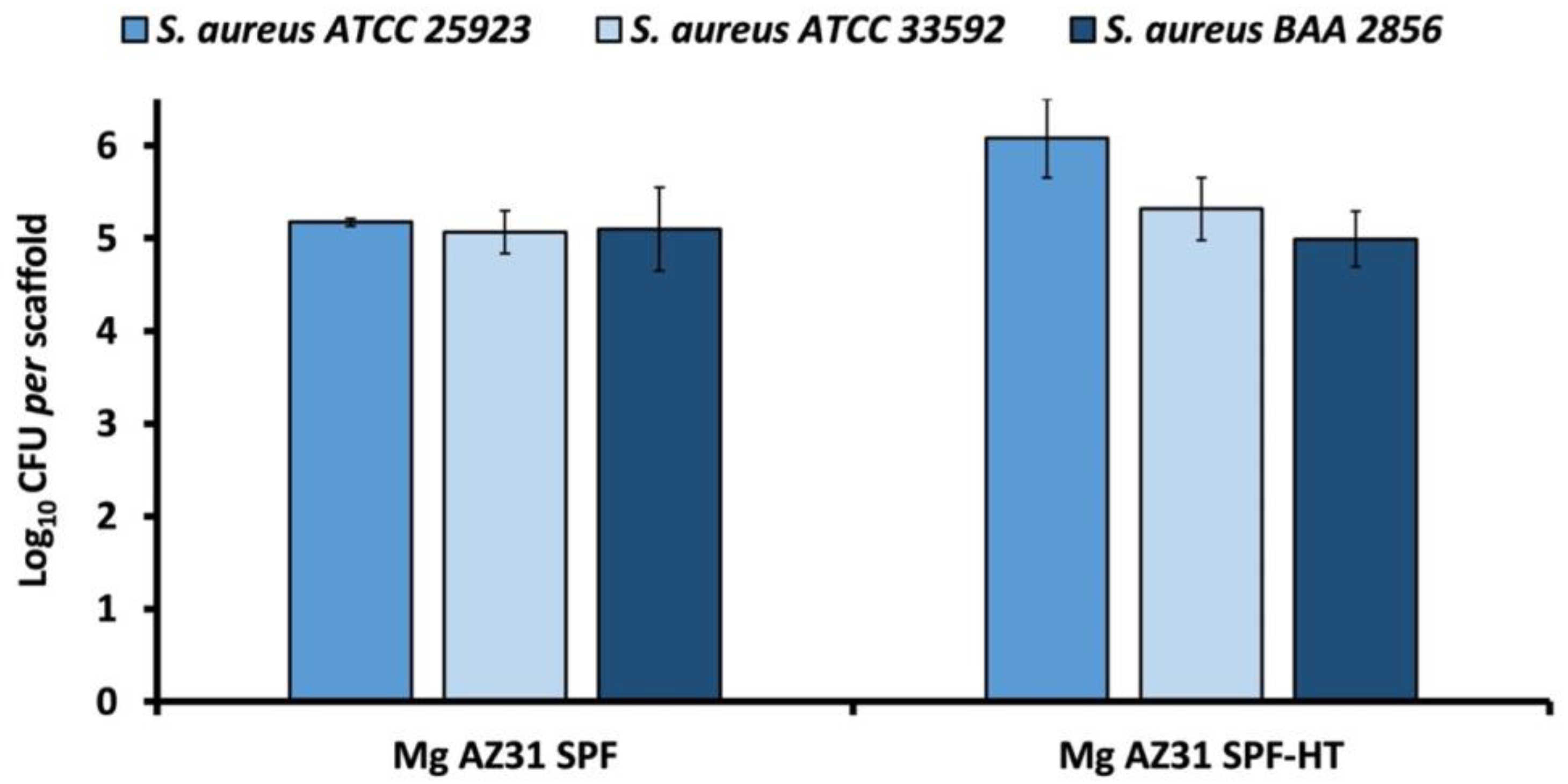

2.6. Evaluation of Antibacterial Properties

2.6.1. Bacterial Growth Inhibition Assay

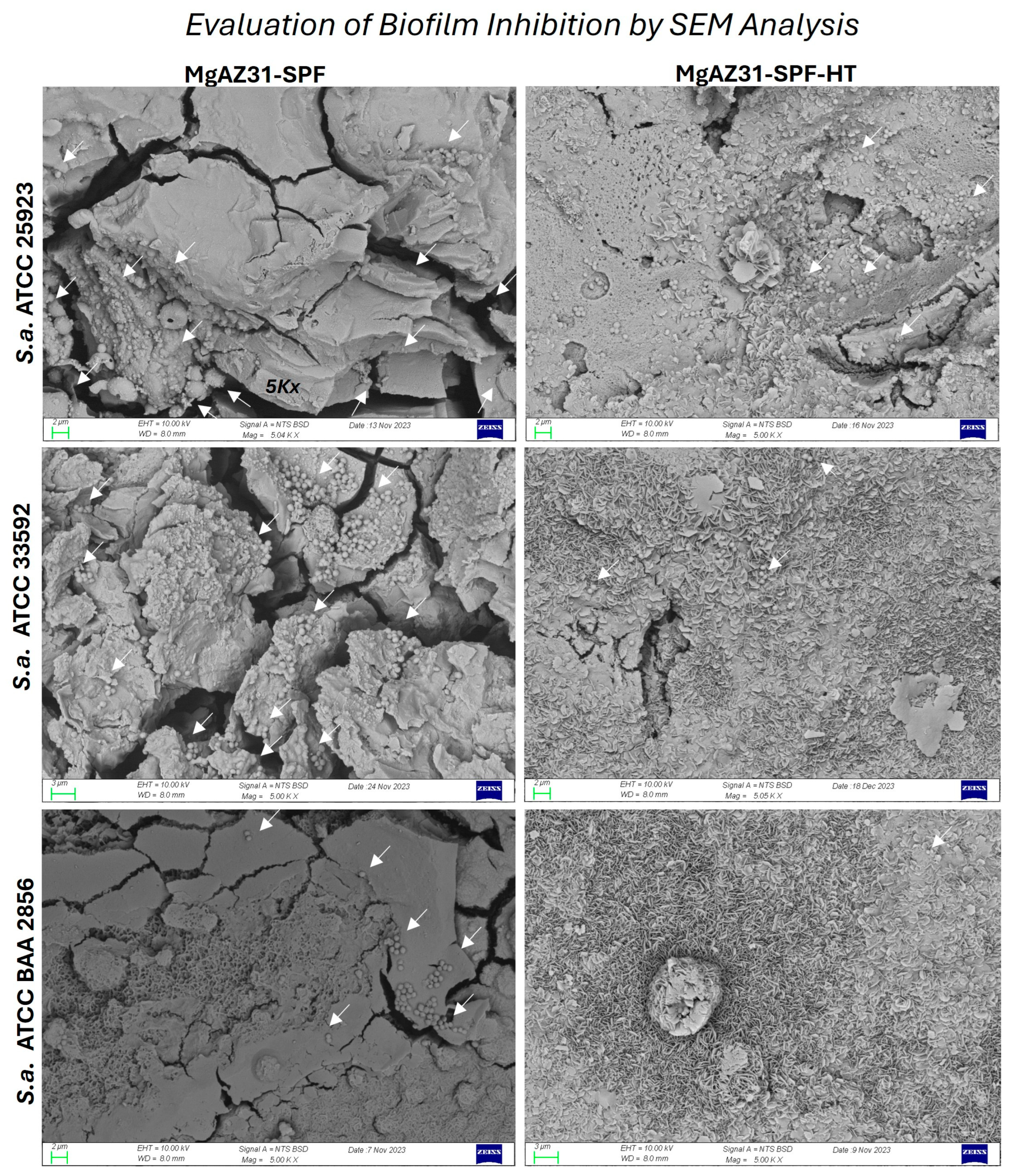

2.6.2. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

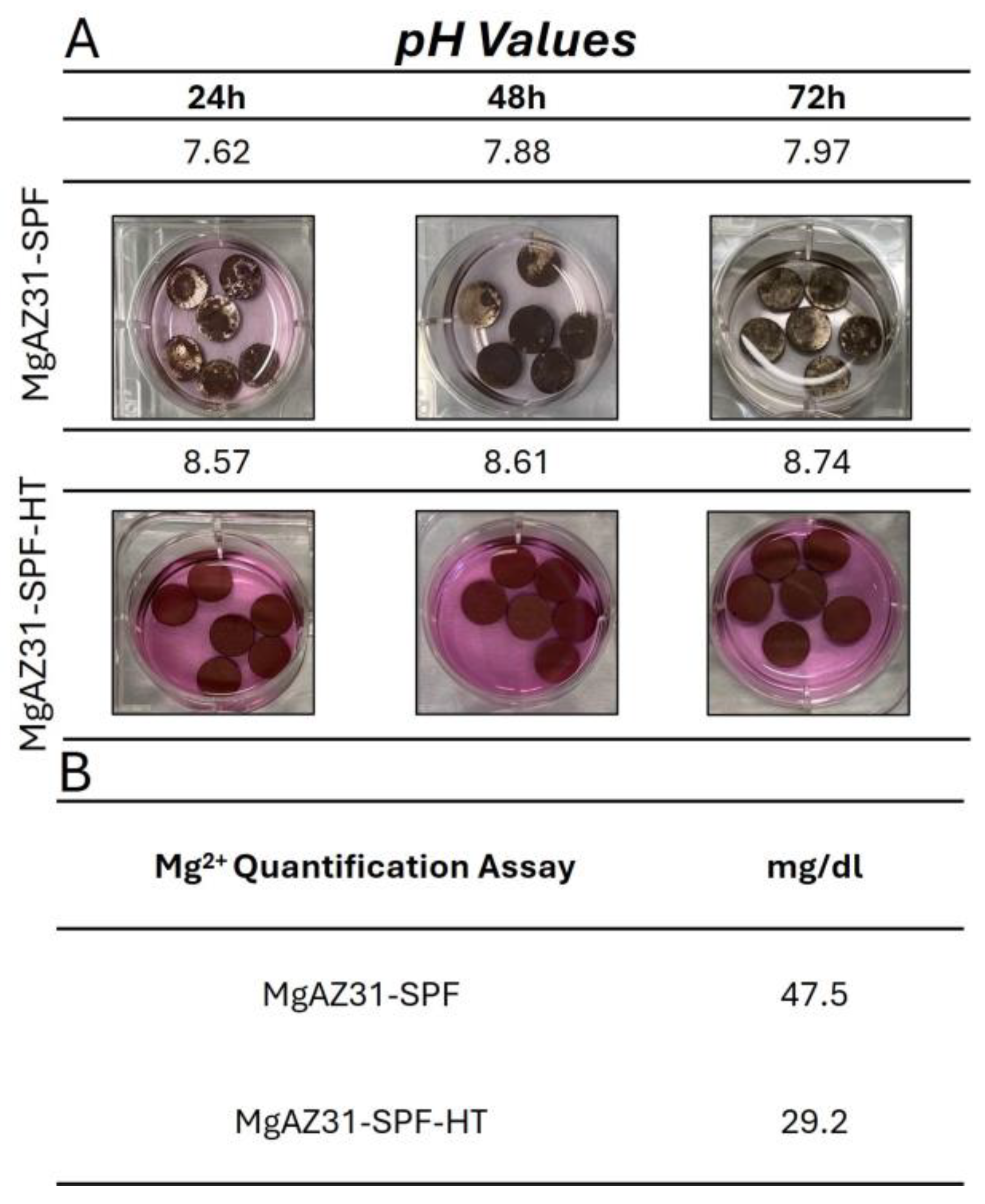

3.1. Evaluation of pH and Magnesium Ion Concentration in AZ31 Alloy SPF Extracts

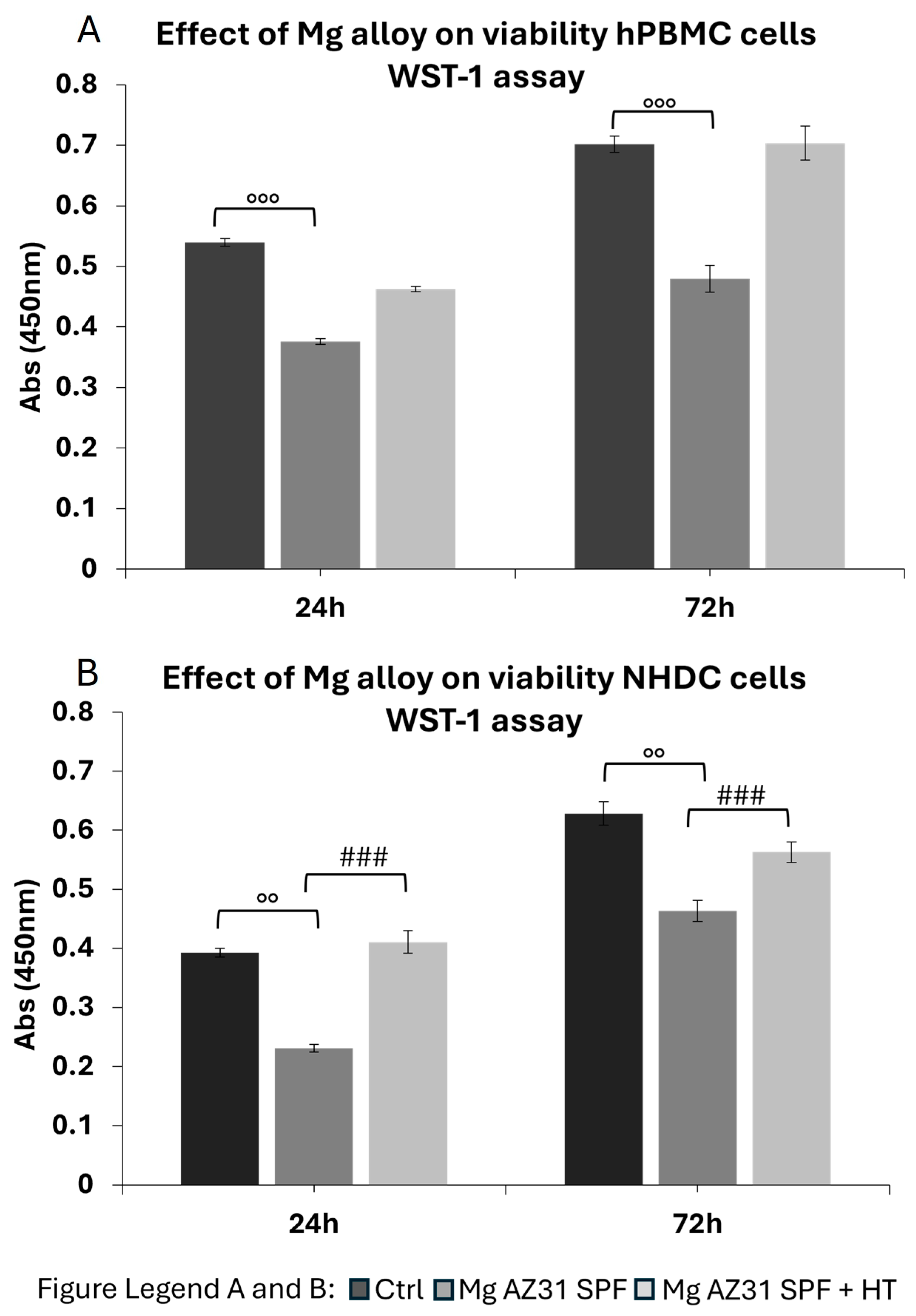

3.2. Cytotoxicity Evaluation on Immune Cells

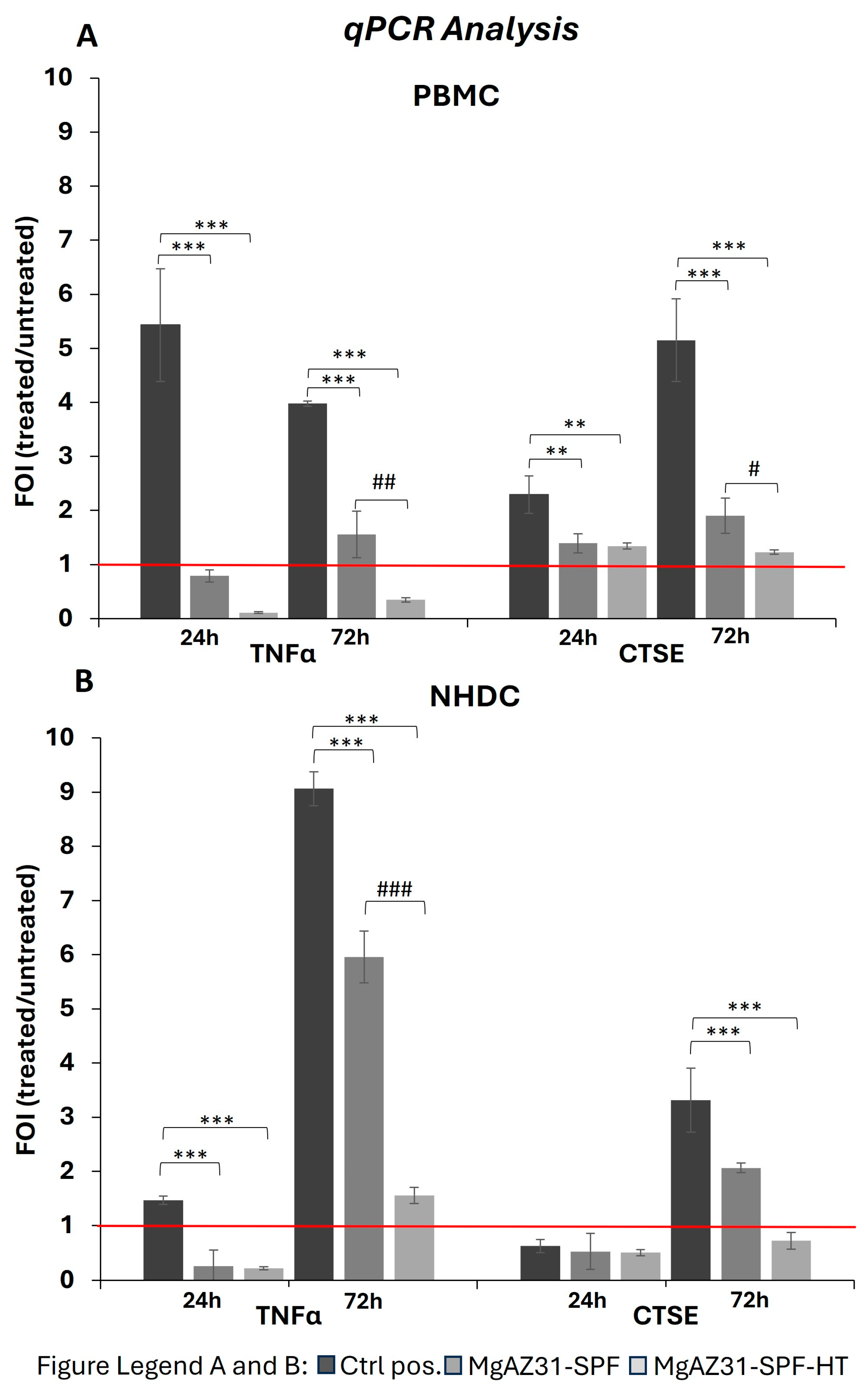

3.3. Hydrothermal Treatment Modulates the Gene Expression Involved in the Immune Response

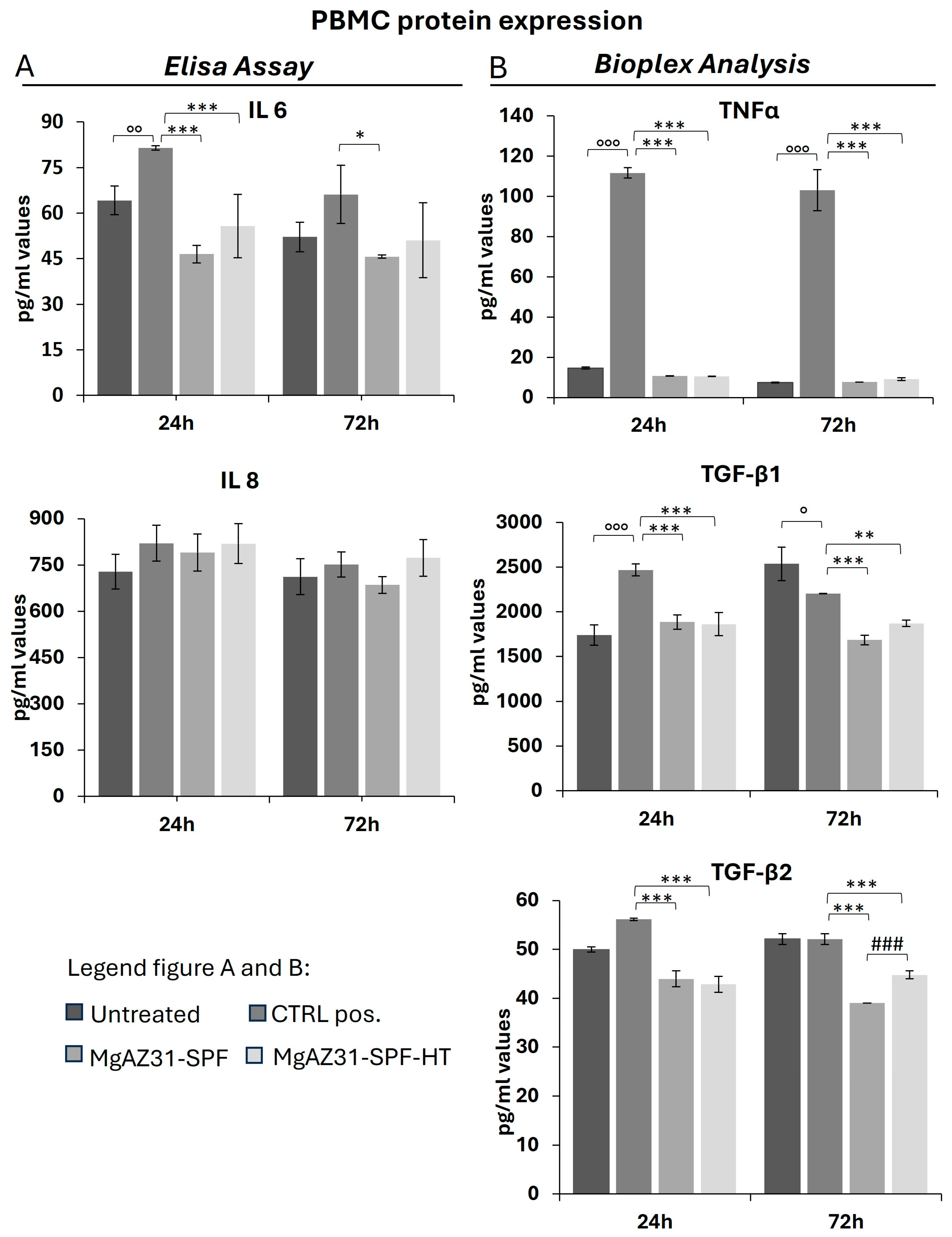

3.4. Hydrothermal Treatment Reduces the Levels of Protein Involved in the Activation of the Immune Cells

3.5. Antibacterial Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carrascal-Hernández, D.C.; Martínez-Cano, J.P.; Rodríguez Macías, J.D.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. Evolution in Bone Tissue Regeneration: From Grafts to Innovative Biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, J.W.; Palusińska, M.; Matak, D.; Pietrzak, D.; Nakielski, P.; Lewicki, S.; Grodzik, M.; Szymański, Ł. The Future of Bone Repair: Emerging Technologies and Biomaterials in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavaresi, G.; Bellavia, D.; De Luca, A.; Costa, V.; Raimondi, L.; Cordaro, A.; Sartori, M.; Terrando, S.; Toscano, A.; Pignatti, G.; et al. Magnesium Alloys in Orthopedics: A Systematic Review on Approaches, Coatings and Strategies to Improve Biocompatibility, Osteogenic Properties and Osteointegration Capabilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhu, G.-Z. Advances in Magnesium-Based Biomaterials: Strategies for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance, Mechanical Performance, and Biocompatibility. Crystals 2025, 15, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Raman, R.K.; Choudhary, L.; Shechtman, D. Simulated Body Fluid-Assisted Stress Corrosion Cracking of a Rapidly Solidified Magnesium Alloy RS66. Materials 2024, 17, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.A.; Tamjid, E. Controlled biodegradation of magnesium alloy in physiological environment by metal organic framework nanocomposite coatings. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, E.; Schoberwalter, T.; Mader, K.; Seitz, J.M.; Kopp, A.; Baranowsky, A.; Keller, J. The Biological Effects of Magnesium-Based Implants on the Skeleton and Their Clinical Implications in Orthopedic Trauma Surgery. Biomater. Res. 2024, 28, 0122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Tang, Y.; Wang, K. A review on magnesium alloys for biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 953344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuzyegit, B.; Karali, A.; De Mori, A.; Smith, N.; Usov, S.; Shashkov, P.; Bonithon, R.; Blunn, G. Evaluation of Corrosion Performance of AZ31 Mg Alloy in Physiological and Highly Corrosive Solutions. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, P.; Cusanno, A.; Bagudanch, I.; Centeno, G.; Ferrer, I.; Garcia-Romeu, M.; Palumbo, G. Experimental and numerical analysis of innovative processes for producing a resorbable cheekbone prosthesis. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 70, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.; Garriga Majo, D.; Soo, R.; Disilvio, L.; Gil, A.; Wood, R.; Atwood, R.; Said, R. Superplastic forming of dental and maxillofacial prostheses. In Dental Biomaterials; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 428–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatullo, M.; Piattelli, A.; Ruggiero, R.; Marano, R.M.; Iaculli, F.; Rengo, C.; Papallo, I.; Palumbo, G.; Chiesa, R.; Paduano, F.; et al. Functionalized magnesium alloys obtained by superplastic forming process retain osteoinductive and antibacterial properties: An in-vitro study. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, D.; Paduano, F.; Brogini, S.; Ruggiero, R.; Marano, R.M.; Cusanno, A.; Guglielmi, P.; Piccininni, A.; Pavarini, M.; D’Agostino, A.; et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of novel magnesium alloy implants enhanced by hydrothermal and sol–gel treatments for bone regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 14032–14046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarini, M.; Milanesi, N.; Moscatelli, M.; Chiesa, R. Harnessing Hydrothermal Treatments to Control Magnesium Alloy Degradation for Bioresorbable Implants: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Bath Chemistry Effect. Metals 2025, 15, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Zerankeshi, M.; Zohrevand, M.; Alizadeh, R. Hydrothermal Coating of the Biodegradable Mg-2Ag Alloy. Metals 2023, 13, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Raimondi, L.; Scilabra, S.D.; Pinto, M.L.; Bellavia, D.; De Luca, A.; Guglielmi, P.; Cusanno, A.; Cattini, L.; Pulsatelli, L.; et al. Effect of Hydrothermal Coatings of Magnesium AZ31 Alloy on Osteogenic Differentiation of hMSCs: From Gene to Protein Analysis. Materials 2025, 18, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Raimondi, L.; Bellavia, D.; De Luca, A.; Guglielmi, P.; Cusanno, A.; Cattini, L.; Pulsatelli, L.; Pavarini, M.; Chiesa, R.; et al. Hydrothermal Magnesium Alloy Extracts Modulate MicroRNA Expression in RAW264.7 Cells: Implications for Bone Remodeling. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, T.; Schmitzer, E.; Suresh, A.P.; Acharya, A.P. Immune response differences in degradable and non-degradable alloy implants. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 24, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negut, I.; Albu, C.; Bita, B. Advances in Antimicrobial Coatings for Preventing Infections of Head-Related Implantable Medical Devices. Coatings 2024, 14, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Szczerba, M.; Karbowniczek, J.; Cichocki, K.; Krzyzanowski, M.; Bajda, S.; Sulka, G.D.; Szuwarzynsky, M.; Sokolowski, K.; Wiese, B. Enhancedcorrosion resistance of magnesium alloy via surface transfer of microwave-synthesized, non-toxic, and ultra-smooth nitrogen-doped amorphous carbon thin film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 695, 162847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojak, V.; Jain, J.; Singhal, T.; Saxena, K.; Prakash, C.; Agrawal, M.; Malik, V. Friction Stir Processing and Cladding: An Innovative Surface Engineering Technique to Tailor Magnesium-Based Alloys for Biomedical Implants. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2025, 32, 2340007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendea, R.E.; Raducanu, D.; Claver, A.; García, J.A.; Cojocaru, V.D.; Nocivin, A.; Stanciu, D.; Serban, N.; Ivanescu, S.; Trisca-Rusu, C.; et al. Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys for Personalised Temporary Implants. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, S.; Sankaranarayanan, D.; Gupta, M. Magnesium-Based Temporary Implants: Potential, Current Status, Applications, and Challenges. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikin, M.; Shalomeev, V.S.; Kukhar, V.; Kostryzhev, A.; Kuziev, I.; Kulynych, V.; Dykha, O.; Dykha, V.; Shapoval, O.; Zagorskis, A.; et al. Recent Advances in Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys for Medical Implants: Evolution, Innovations, andClinical Translation. Crystals 2025, 15, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanna, F.; De Luca, A.; Vandenbulcke, F.; Di Matteo, B.; Kon, E.; Grassi, A.; Ballardini, A.; Morozzi, G.; Raimondi, L.; Bellavia, D.; et al. Preliminary osteogenic and antibacterial investigations of wood derived antibiotic-loaded bone substitute for the treatment of infected bone defects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1412584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Yang, L.; Yi, F.; Chen, C.; Guo, J.; Qi, Z.; Song, Y. Antibacterial Pure Magnesium and Magnesium Alloys for Biomedical Materials—A Review. Crystals 2024, 14, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgente, D.; Palumbo, G.; Piccininni, A.; Guglielmi, P.; Aksenov, S. Investigation on the thickness distribution of highly customized titanium biomedical implants manufactured by superplastic forming. Cirp J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 20, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Hu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, E. Grain growth kinetics of a fine-grained AZ31 magnesium alloy produced by hot rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 493, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.; Ruggiero, R.; Cordaro, A.; Marrelli, B.; Raimondi, L.; Costa, V.; Bellavia, D.; Aiello, E.; Pavarini, M.; Piccininni, A.; et al. Towards Accurate Biocompatibility: Rethinking Cytotoxicity Evaluation for Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys in Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Pan, H. Effects of magnesium alloy corrosion on biological response—Perspectives of metal-cell interaction. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 133, 101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrescu, A.M.; Necula, M.G.; Gebaur, A.; Golgovici, F.; Nica, C.; Curti, F.; Iovu, H.; Costache, M.; Cimpean, A. In Vitro Macrophage Immunomodulation by Poly(ε-caprolactone) Based-Coated AZ31 Mg Alloy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.W.; Rahmati, M.; Barrantes, A.; Haugen, H.J.; Mirtaheri, P. In Vitro Monitoring of Magnesium-Based Implants Degradation by Surface Analysis and Optical Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C. Study of ph effect on AZ31 magnesium alloy corrosion for using in temporaryimplants. Int. J. Adv. Med. Biotechnol. 2020, 3, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, D.D.; Li, M.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, S.; Peng, F. Osteogenesis, angiogenesis and immune response of Mg-Al layered double hydroxide coating on pure Mg. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, A.; Thongsiri, C.; Kudo, D.; Phuong, D.N.D.; Iwamoto, Y.; Fujii, W.; Nagai-Yoshioka, Y.; Yamasaki, R.; Ariyoshi, W. Mechanisms Underlying the Suppression of IL-1β Expression by Magnesium Hydroxide Nanoparticles. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiwut, R.; Kasinrerk, W. Very low concentration of lipopolysaccharide can induce the production of various cytokines and chemokines in human primary monocytes. BMC Res. Notes 2022, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.E.; Swan, D.J.; Sayers, B.L.; Harry, R.A.; Patterson, A.M.; von Delwig, A.; Robinson, J.H.; Isaacs, J.D.; Hilkens, C.M. LPS activation is required for migratory activity and antigen presentation by tolerogenic dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 85, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, S.; Luo, J.L. The multifaceted roles of cathepsins in immune and inflammatory responses: Implications for cancer therapy, autoimmune diseases, and infectious diseases. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchetina, E.V.; Markova, G.A.; Satybaldyev, A.M.; Lila, A.M. Downregulation of Tumour Necrosis Factor α Gene Expression in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Cultured in the Presence of Tofacitinib Prior to Therapy Is Associated with Clinical Remission in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lieshout, A.W.; Barrera, P.; Smeets, R.L.; Pesman, G.J.; van Riel, P.L.; van den Berg, W.B.; Radstake, T.R. Inhibition of TNF alpha during maturation of dendritic cells results in the development of semi-mature cells: A potential mechanism for the beneficial effects of TNF alpha blockade in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakehashi, H.; Nishioku, T.; Tsukuba, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Nakamura, S.; Yamamoto, K. Differential regulation of the nature and functions of dendritic cells and macrophages by cathepsin E. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 5728–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatnitskaia, S.; Rafikova, G.; Bilyalov, A.; Chugunov, S.; Akhatov, I.; Pavlov, V.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Modelling of macrophage responses to biomaterials. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1349461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, F. Formation of a hydrophobic and corrosion resistant coating on magnesium alloy via a one-step hydrothermal method. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2017, 505, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocchetti, M.; Piccinini, M.; Pietrella, D.; Antognelli, C.; Ricci, M.; Di Michele, A.; Jalaoui, L.; Ambrogi, V. The Effect of Surface Functionalization of Magnesium Alloy on Degradability, Bioactivity, Cytotoxicity, and Antibiofilm Activity. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.H.; Nisar, Z.; Hussain, S.Z.; Sabri, A.N.; Jamil, S. In vitro antibiofilm and anti-adhesion effects of magnesium oxide nanoparticles against antibiotic resistant bacteria. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 62, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oknin, H.; Steinberg, D.; Shemesh, M. Magnesium ions mitigate biofilm formation of Bacillus species via downregulation of matrix genes expression. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Yang, J.; Shang, Y.; Deng, S.; Yao, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Peng, C. Magnesium-doped Nanostructured Titanium Surface Modulates Macrophage-mediated Inflammatory Response for Ameliorative Osseointegration. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 7185–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, S.; Goeres, D.M.; Skogman, M.; Vuorela, P.; Fallarero, A. Prevention of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation by antibiotics in 96-Microtiter Well Plates and Drip Flow Reactors: Critical factors influencing outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reigada, I.; Guarch-Pérez, C.; Patel, J.Z.; Riool, M.; Savijoki, K.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Zaat, S.A.J.; Fallarero, A. Combined Effect of Naturally-Derived Biofilm Inhibitors and Differentiated HL-60 Cells in the Prevention of. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, Y.; Mashima, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Hara, S.; Takata, T.; Kamimura, H.; Takagi, S.; Jimi, S. Inhibitory effects of polysorbate 80 on MRSA biofilm formed on different substrates including dermal tissue. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.I.; Szafrański, S.P.; Ingendoh-Tsakmakidis, A.; Stiesch, M.; Mueller, P.P. Evidence for inoculum size and gas interfaces as critical factors in bacterial biofilm formation on magnesium implants in an animal model. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 186, 110684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Bawazir, M.; Dhall, A.; Kim, H.E.; He, L.; Heo, J.; Hwang, G. Implication of Surface Properties, Bacterial Motility, and Hydrodynamic Conditions on Bacterial Surface Sensing and Their Initial Adhesion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 643722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirani, Z.A.; Fatima, A.; Urooj, S.; Aziz, M.; Khan, M.N.; Abbas, T. Relationship of cell surface hydrophobicity with biofilm formation and growth rate: A study on. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2018, 21, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouloussa, H.; Mirza, M.; Ansley, B.; Jilakara, B.; Yue, J.J. Implant Surface Technologies to Prevent Surgical Site Infections in Spine Surgery. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2023, 17, S75–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanenko, A.M.; Domantovsky, A.G.; Kaminsky, V.V.; Pytskii, I.S.; Emelyanenko, K.A.; Boinovich, L.B. The Mechanisms of Antibacterial Activity of Magnesium Alloys with Extreme Wettability. Materials 2021, 14, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Cai, S.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, T.; Ling, L.; Lu, J.; He, B. Coated Mg Alloy Implants: A Spontaneous Wettability Transition Process with Excellent Antibacterial and Osteogenic Functions. Materials 2025, 18, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Al | Zn | Mn | Ca | Cu | Fe | Ni | Si | Others | Mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | Balance |

| Max | 3.5 | 1.3 | 0.40 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.05 | 0.30 | Balance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Luca, A.; Presentato, A.; Alduina, R.; Raimondi, L.; Bellavia, D.; Costa, V.; Cavazza, L.; Cordaro, A.; Pulsatelli, L.; Cusanno, A.; et al. Hydrothermal Surface Treatment of Mg AZ31 SPF Alloy: Immune Cell Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Potential for Orthopaedic Applications. Metals 2025, 15, 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121328

De Luca A, Presentato A, Alduina R, Raimondi L, Bellavia D, Costa V, Cavazza L, Cordaro A, Pulsatelli L, Cusanno A, et al. Hydrothermal Surface Treatment of Mg AZ31 SPF Alloy: Immune Cell Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Potential for Orthopaedic Applications. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121328

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Luca, Angela, Alessandro Presentato, Rosa Alduina, Lavinia Raimondi, Daniele Bellavia, Viviana Costa, Luca Cavazza, Aurora Cordaro, Lia Pulsatelli, Angela Cusanno, and et al. 2025. "Hydrothermal Surface Treatment of Mg AZ31 SPF Alloy: Immune Cell Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Potential for Orthopaedic Applications" Metals 15, no. 12: 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121328

APA StyleDe Luca, A., Presentato, A., Alduina, R., Raimondi, L., Bellavia, D., Costa, V., Cavazza, L., Cordaro, A., Pulsatelli, L., Cusanno, A., Palumbo, G., Pavarini, M., Chiesa, R., & Giavaresi, G. (2025). Hydrothermal Surface Treatment of Mg AZ31 SPF Alloy: Immune Cell Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Potential for Orthopaedic Applications. Metals, 15(12), 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121328