Experimental Verification of Forming Characteristics Enhancement by Combined Variable Punch Speed/Blank Holder Force Process Path in Warm Deep Drawing of A5182 Aluminum Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

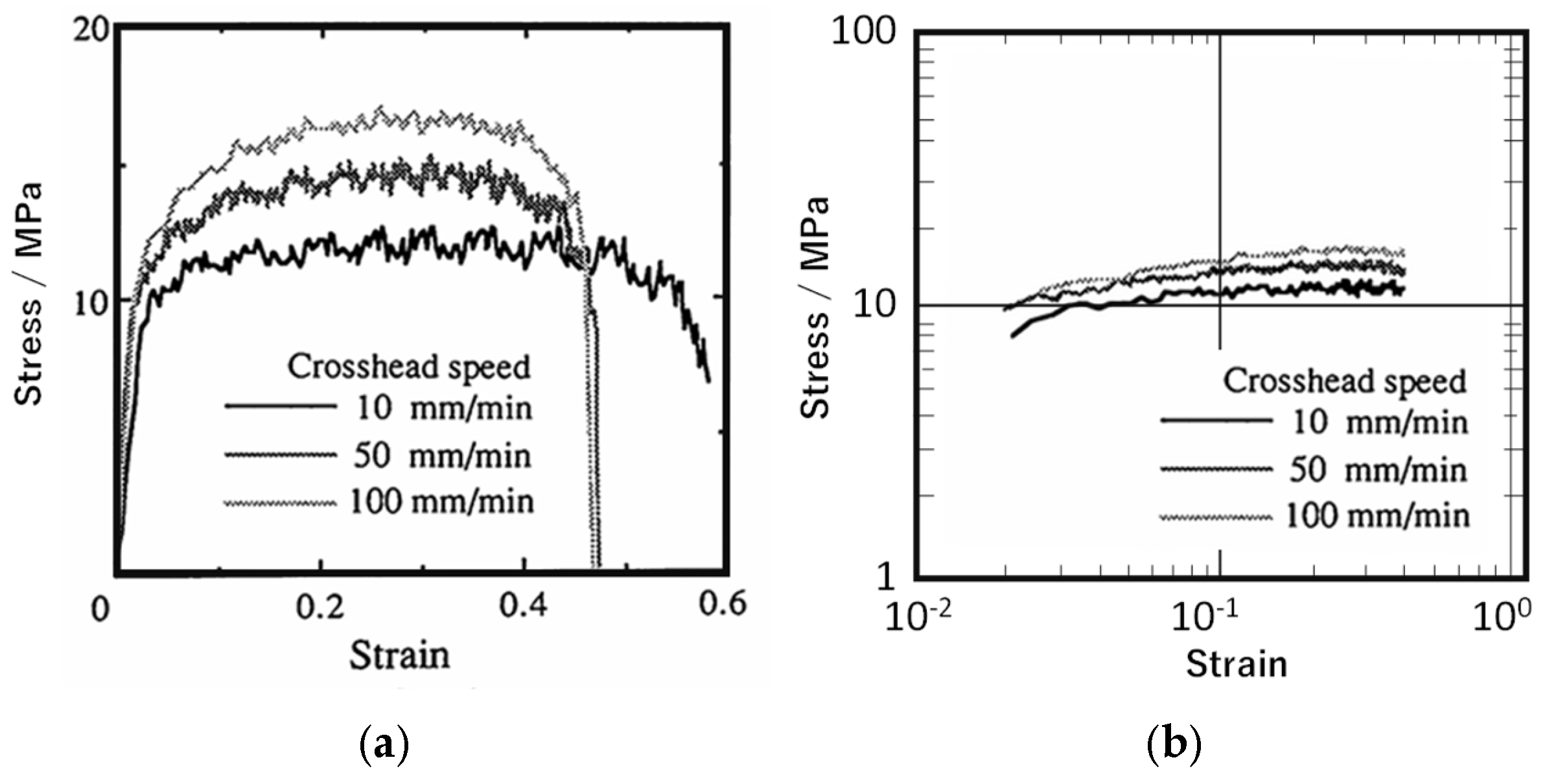

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

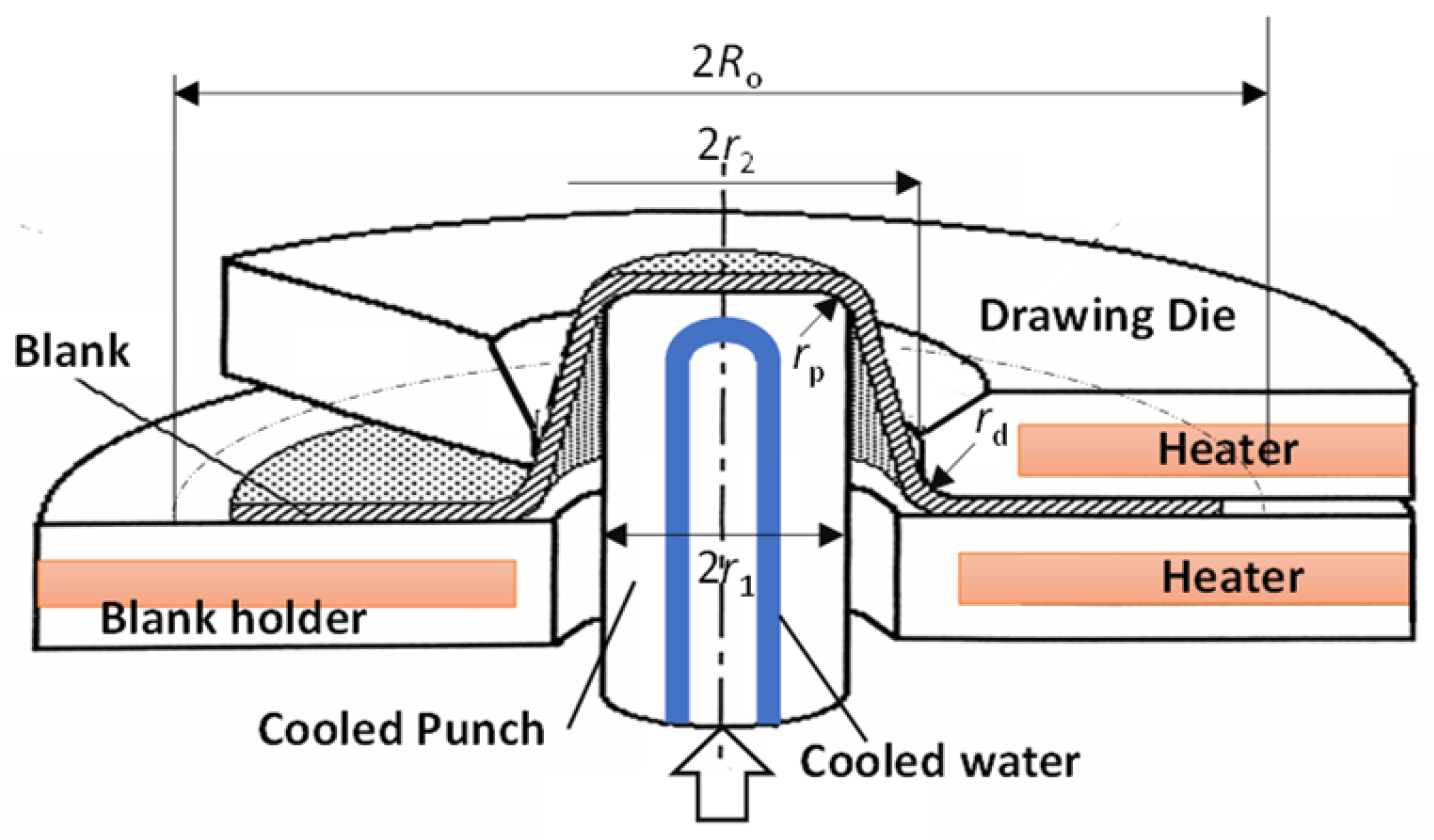

2.2.1. Warm Deep Drawing Test

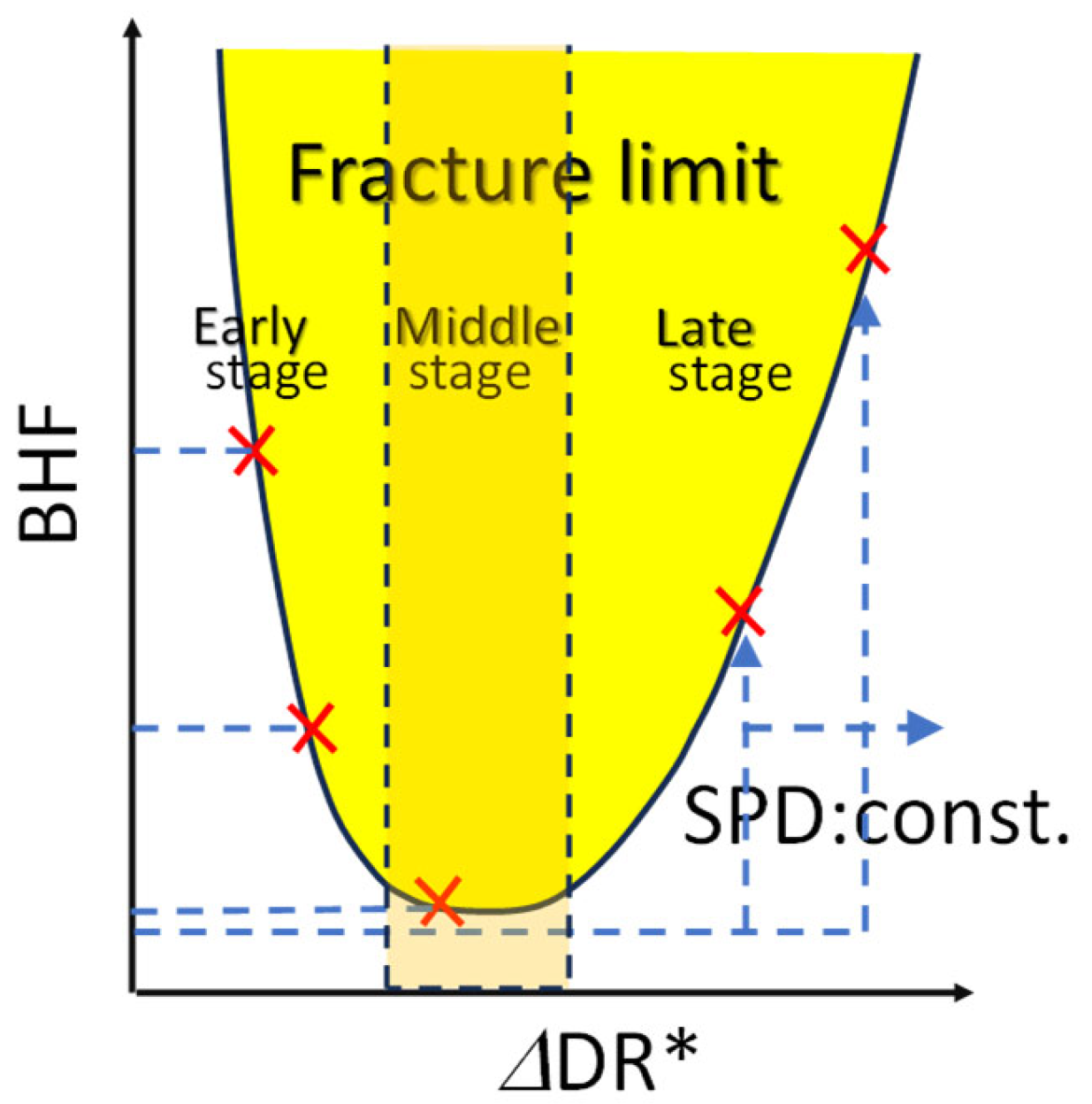

2.2.2. Determination of Fracture Limit and Wrinkle Limit

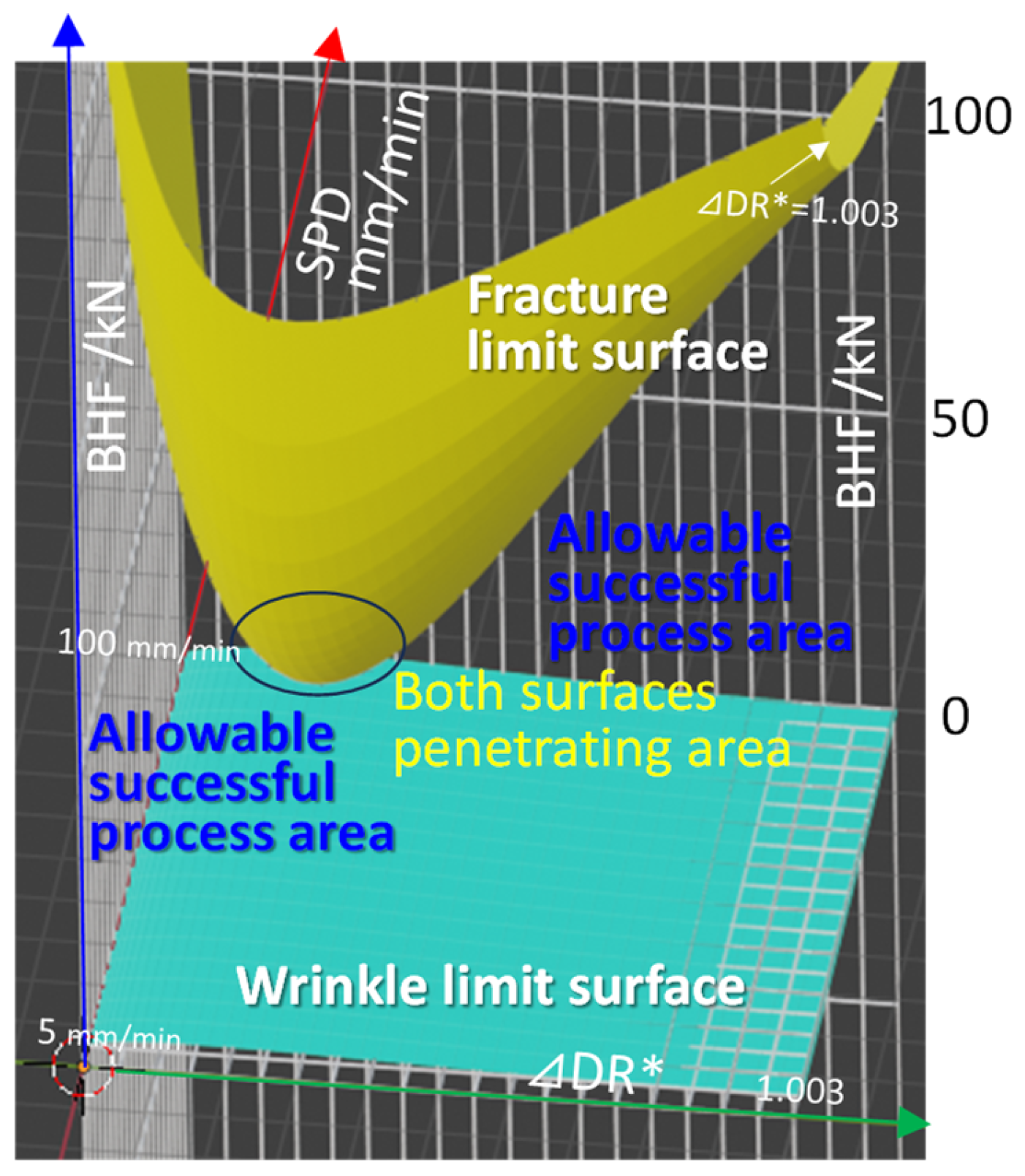

3. Deep Drawing Theory for Process Window

- (1)

- Critical Wrinkle Limit BHF, Hcrw:

- (2)

- Critical Fracture Limit BHF, Hcrf:

4. Results and Discussion

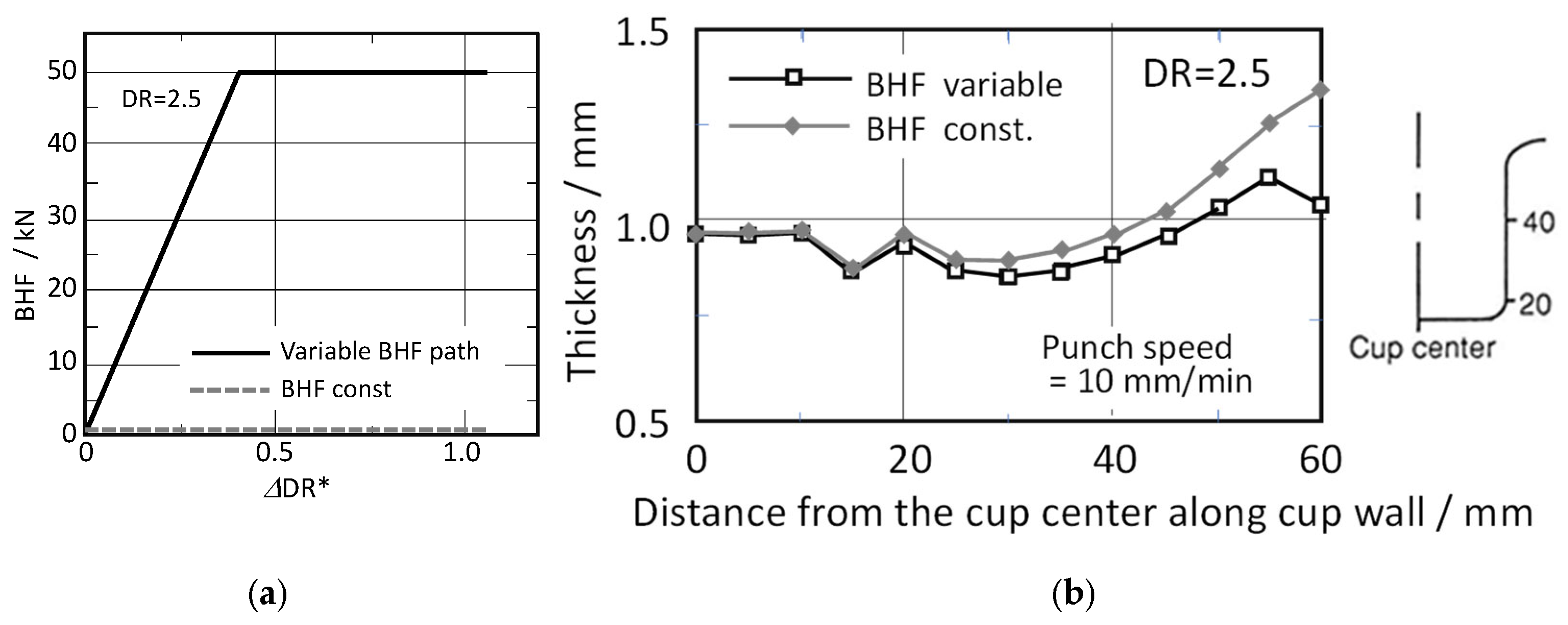

4.1. Warm Deep Drawing Properties with Variable Process Path at DR = 2.5

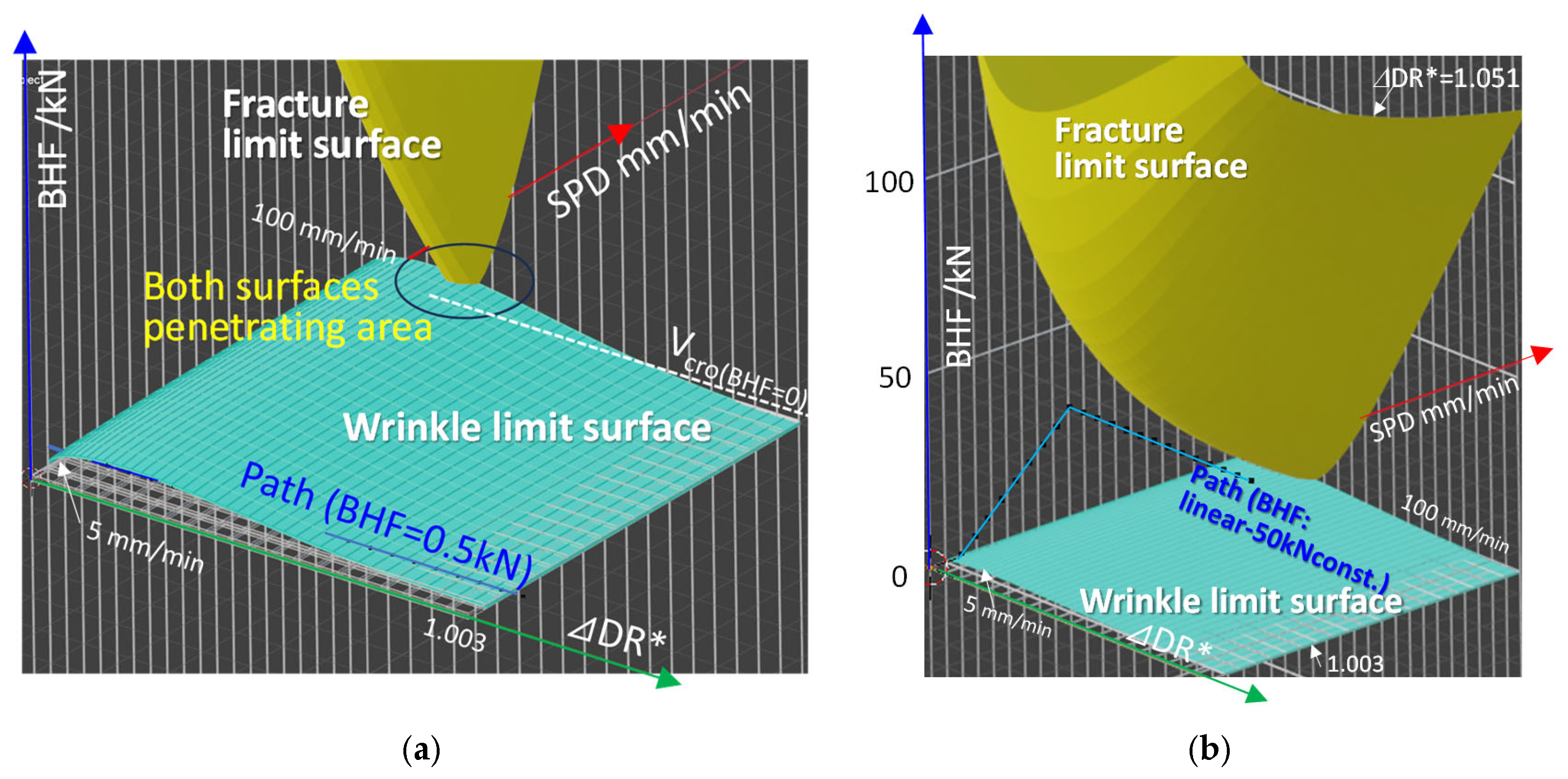

4.1.1. Theoretical Process Window and Process Path

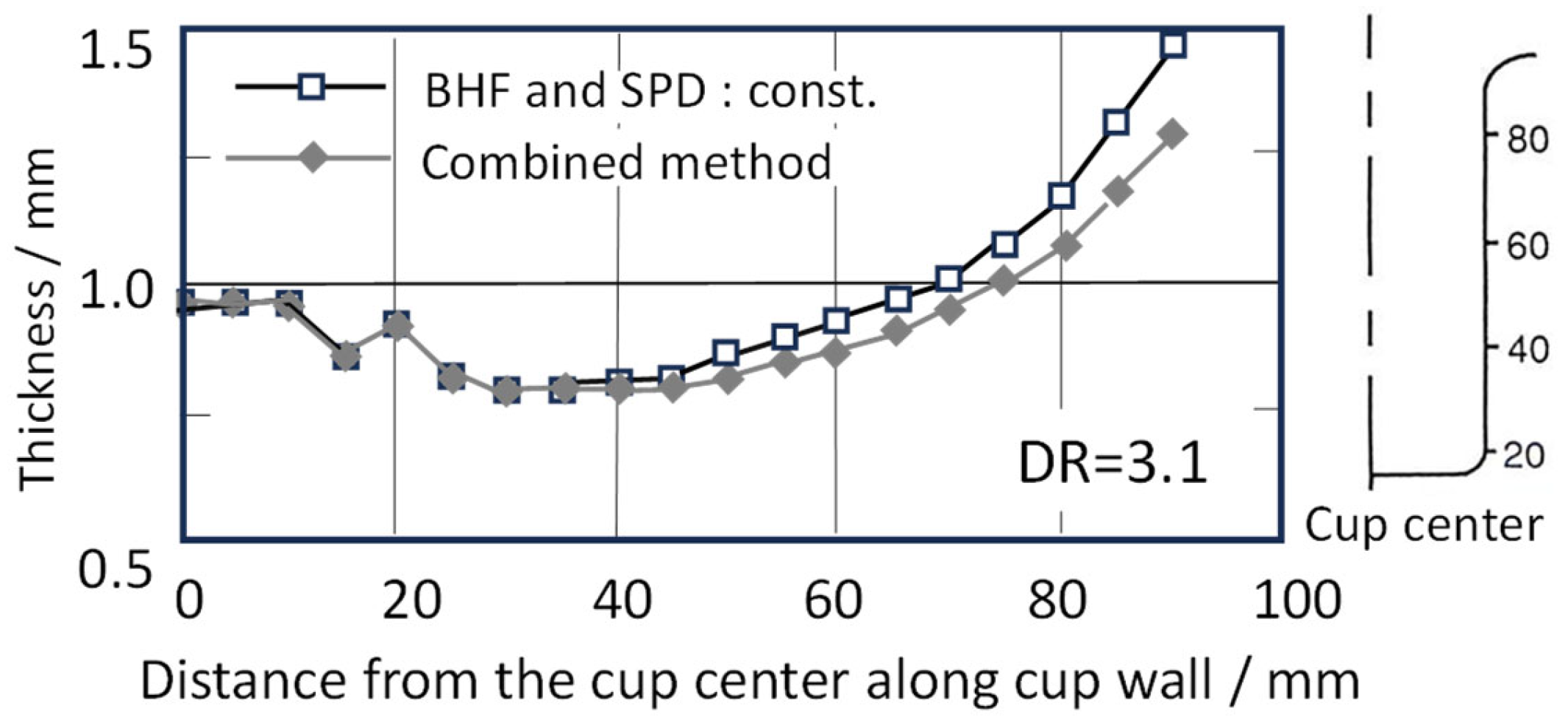

4.1.2. Effect of VBHF Path on Wall Thickness Distribution

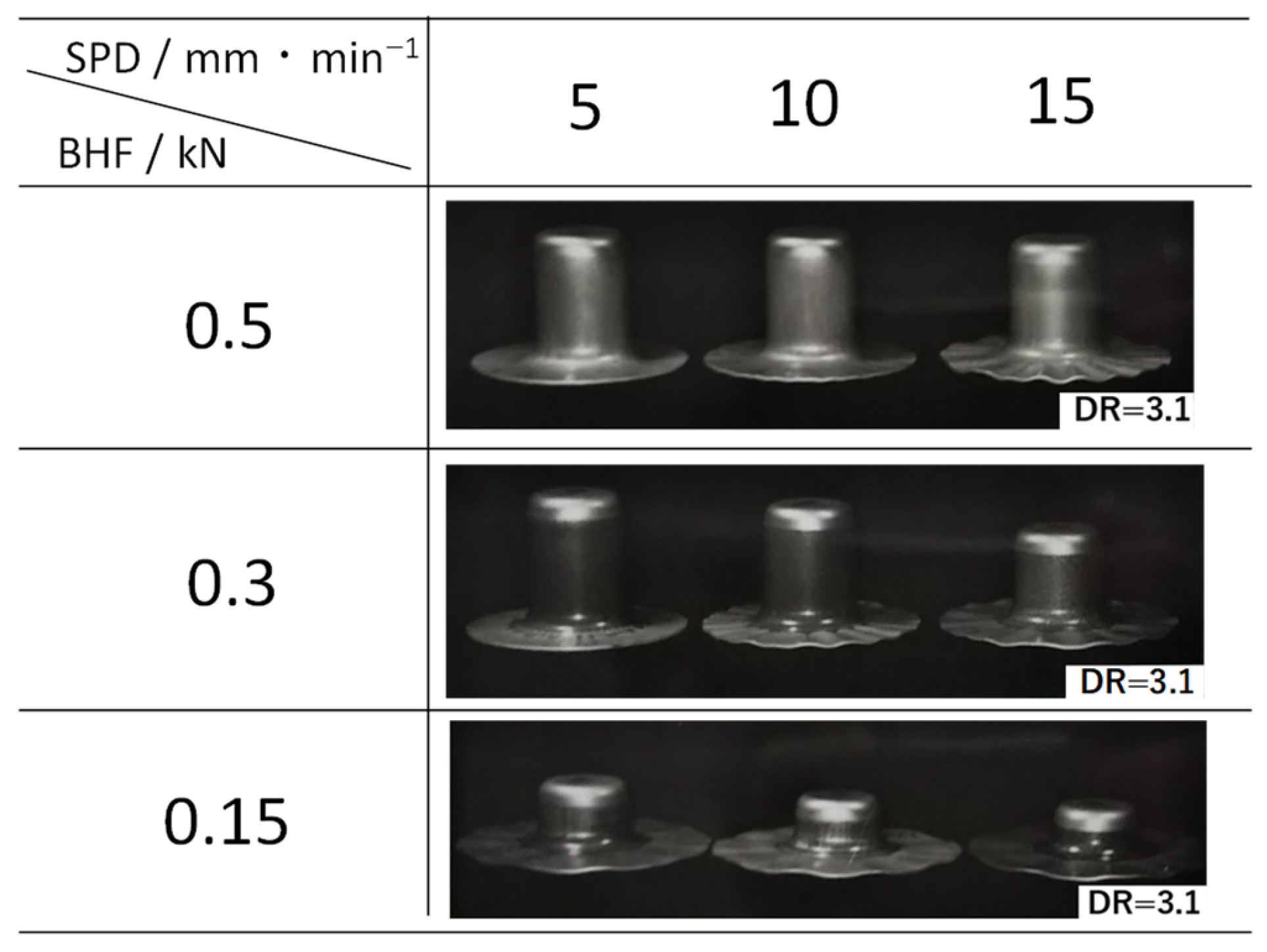

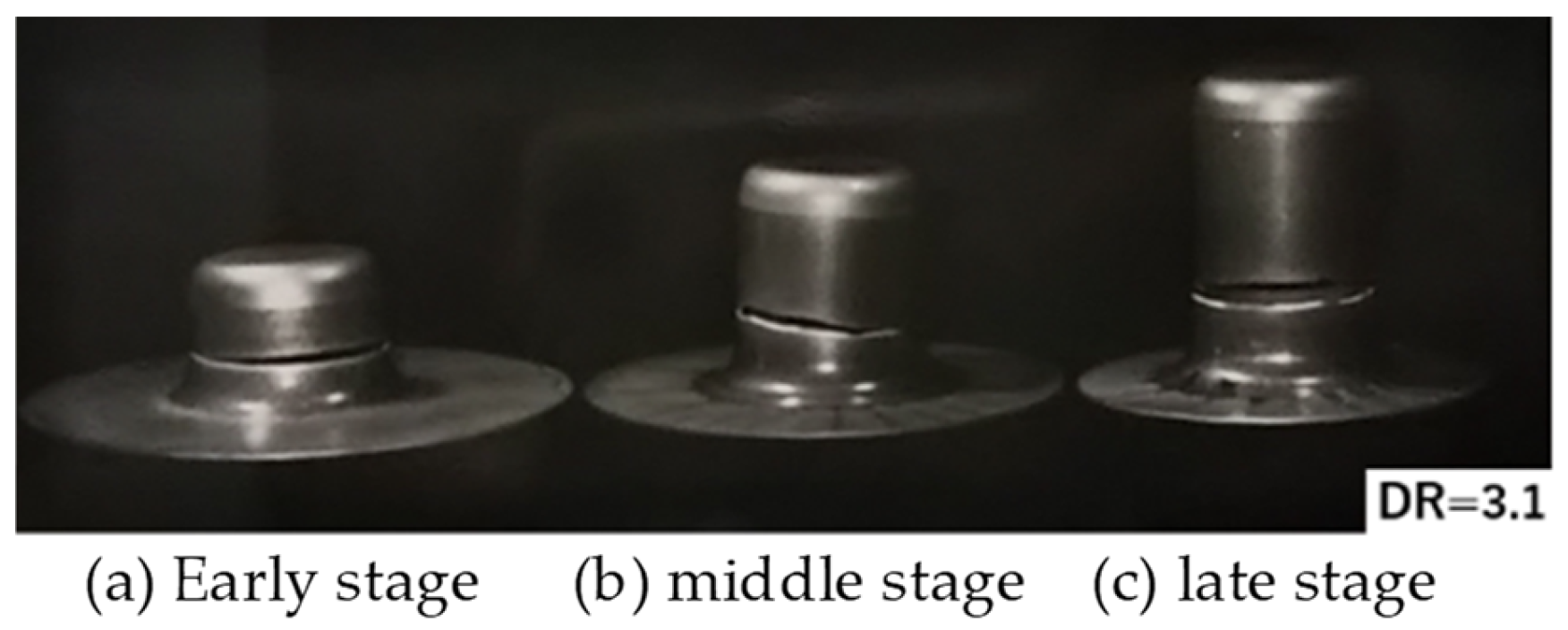

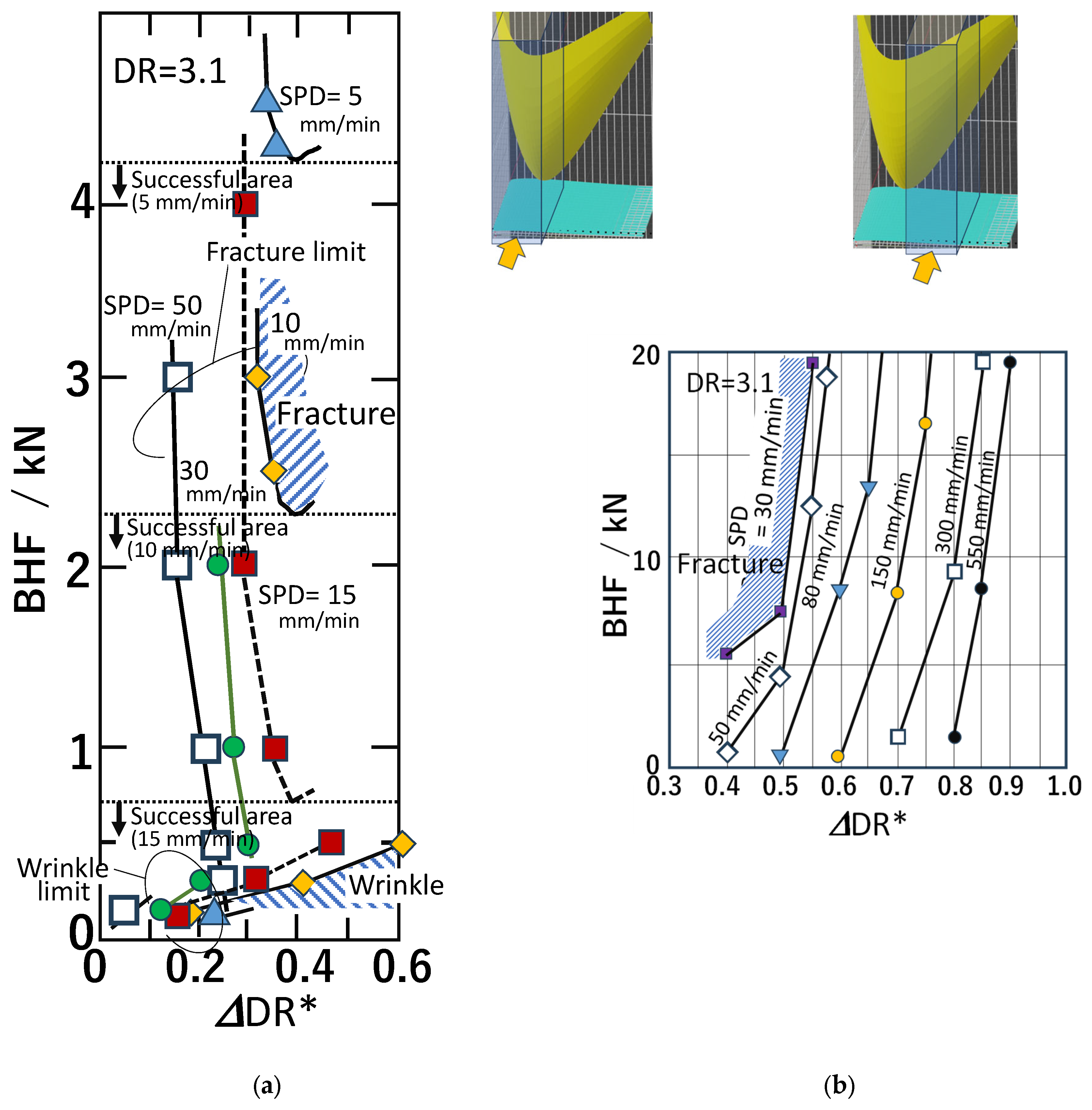

4.2. Warm Deep Drawing Properties with Variable Process Path at DR = 3.1

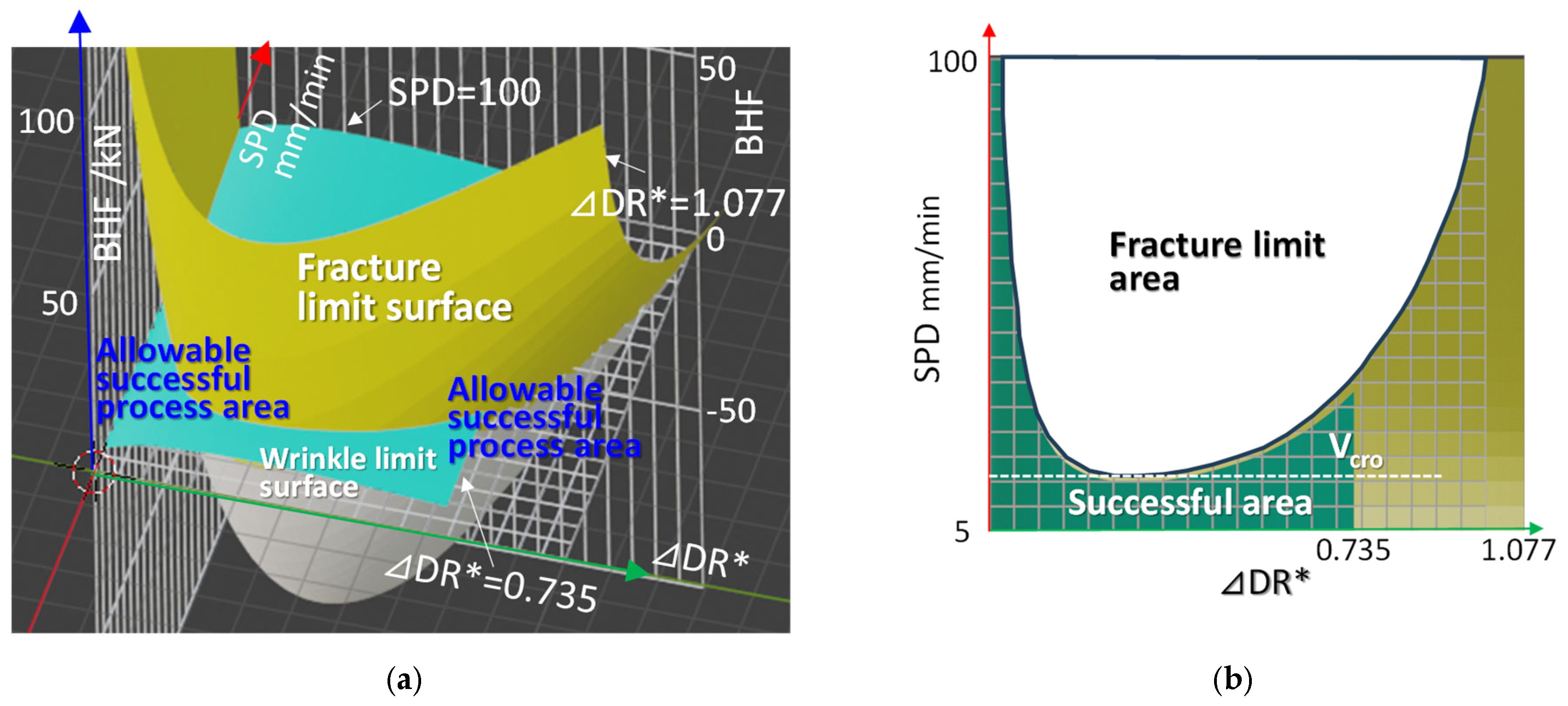

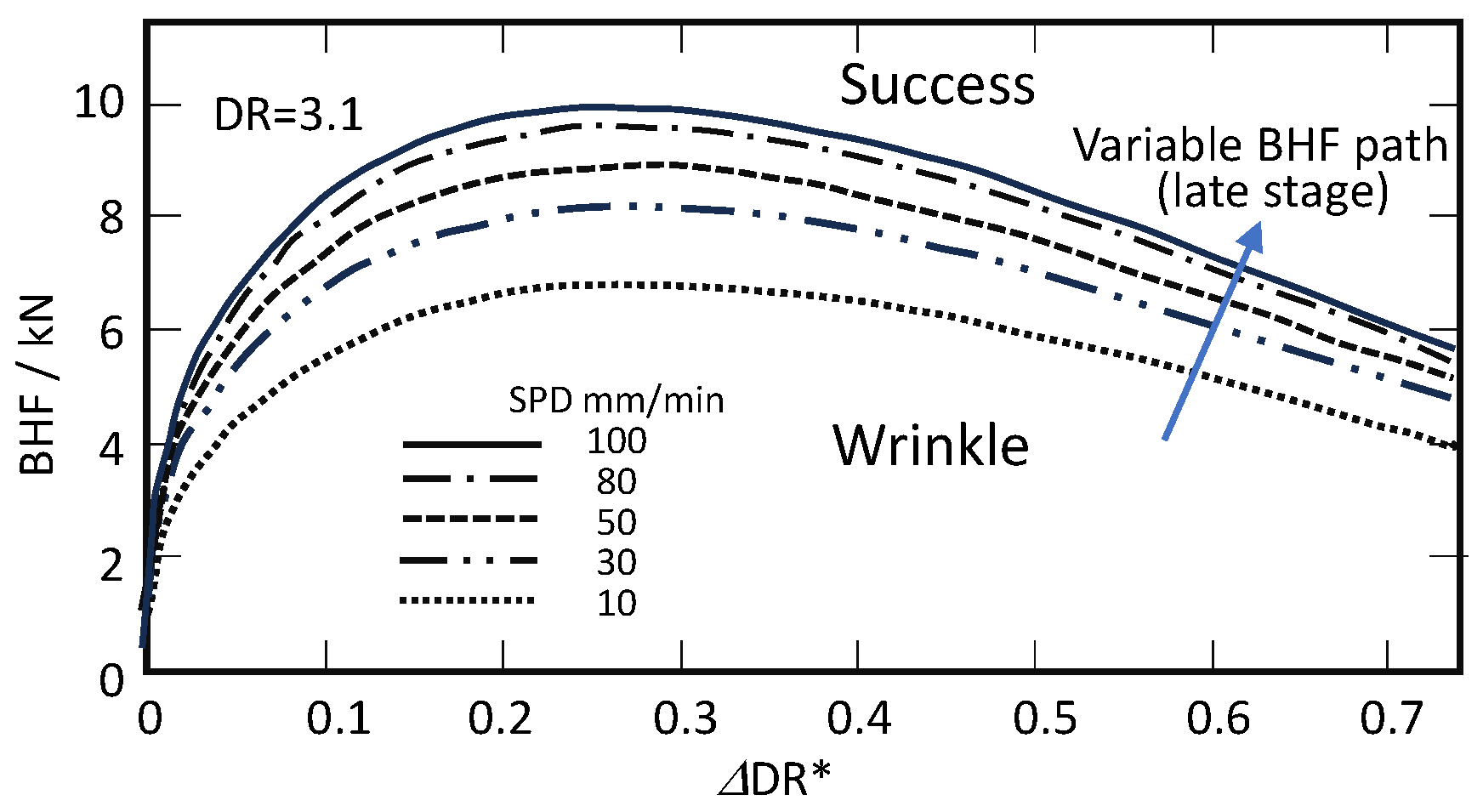

4.2.1. Theoretical Process Window at DR = 3.1

4.2.2. Comparison of Experimental and Theoretical Results for Flange Wrinkling and Fracture Limits

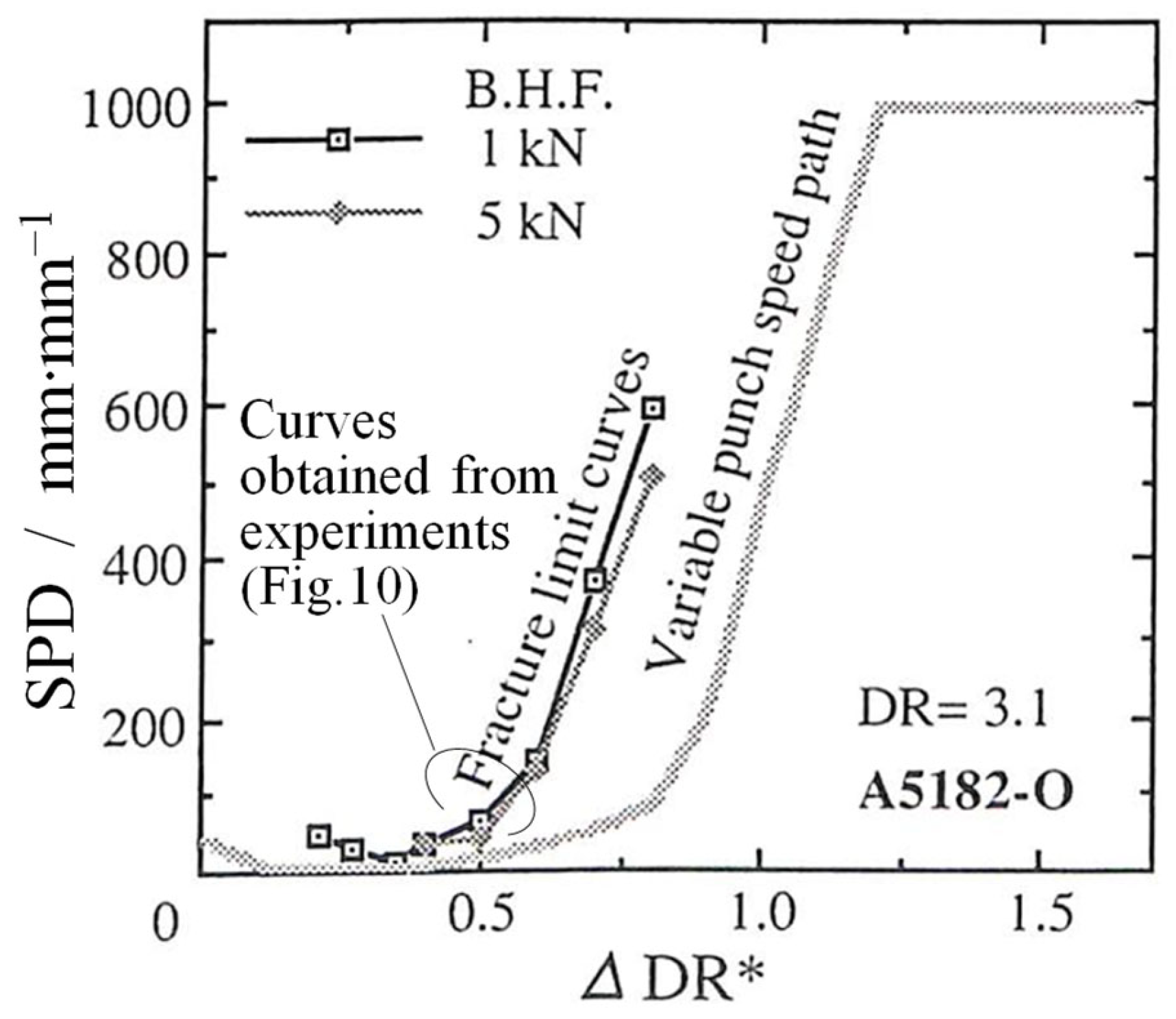

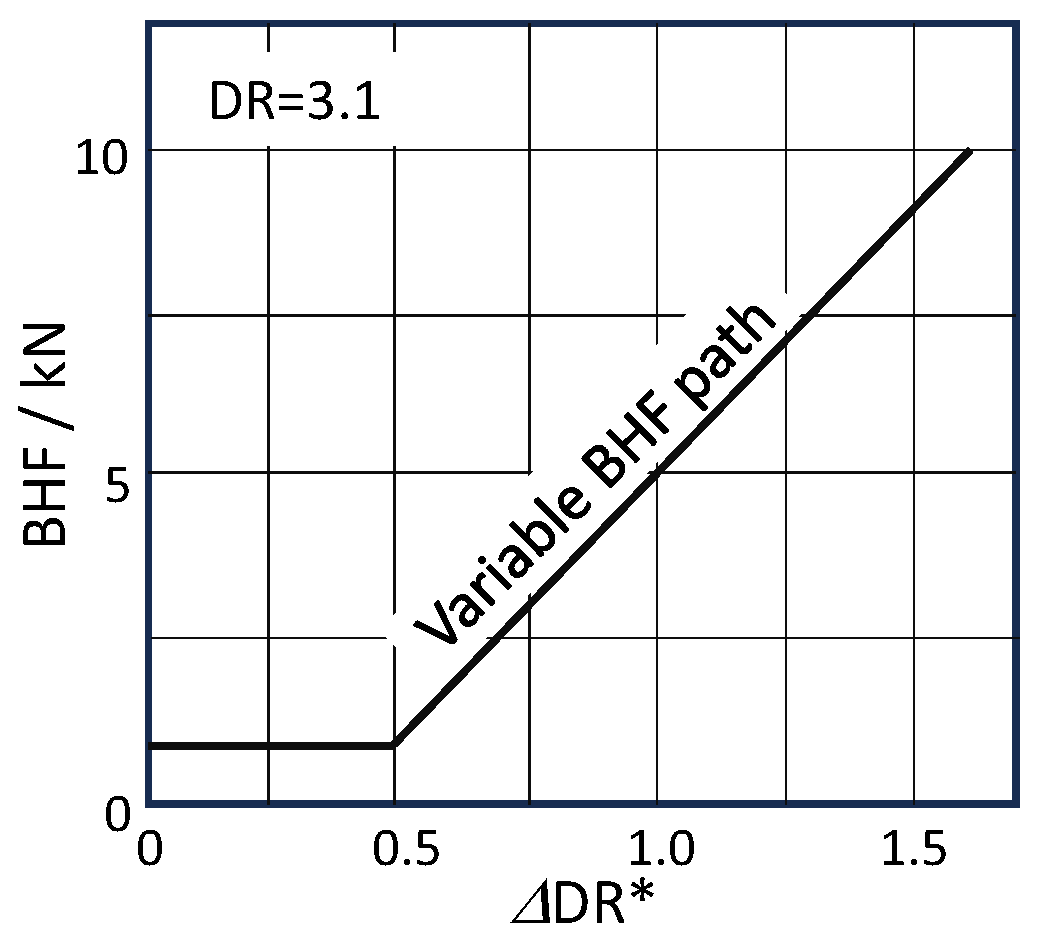

4.2.3. Effects and Effectiveness of Combined Variable Process Path

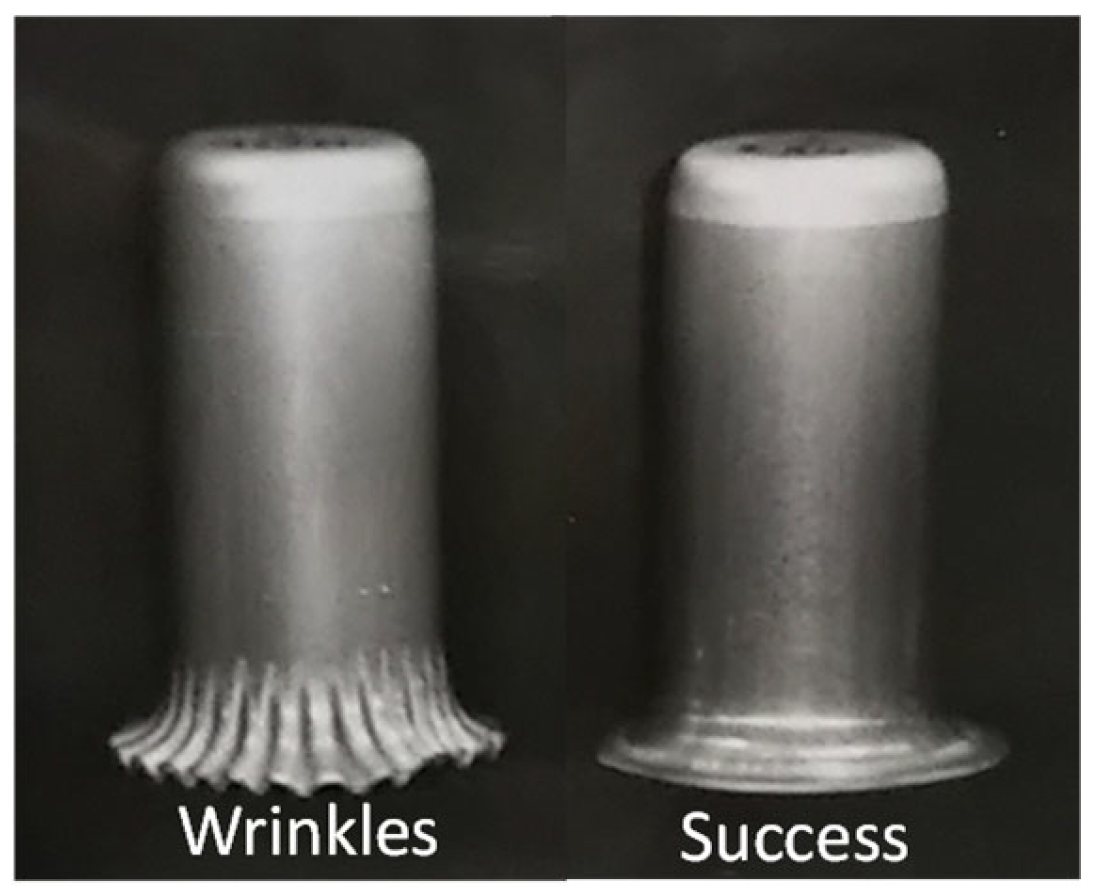

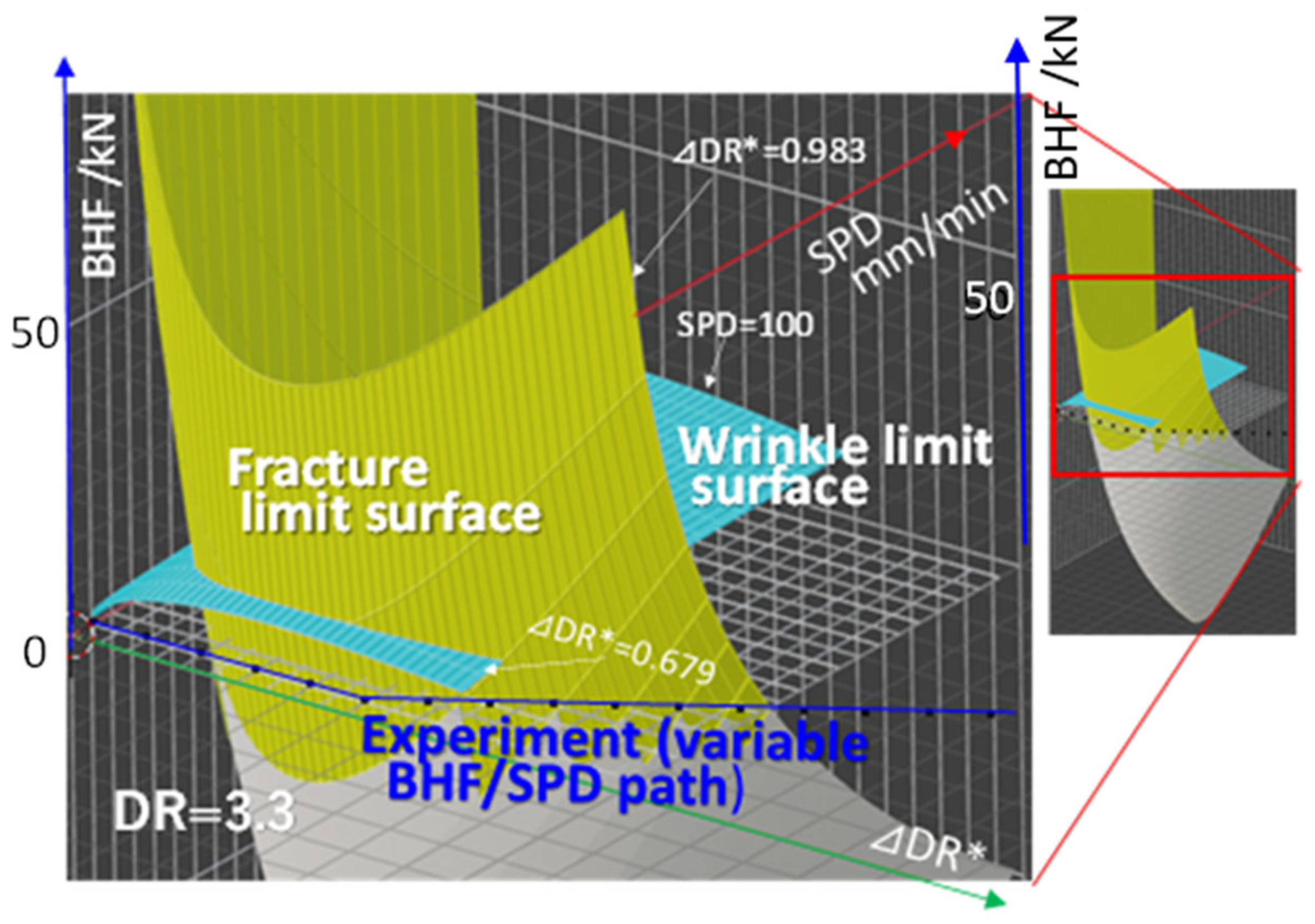

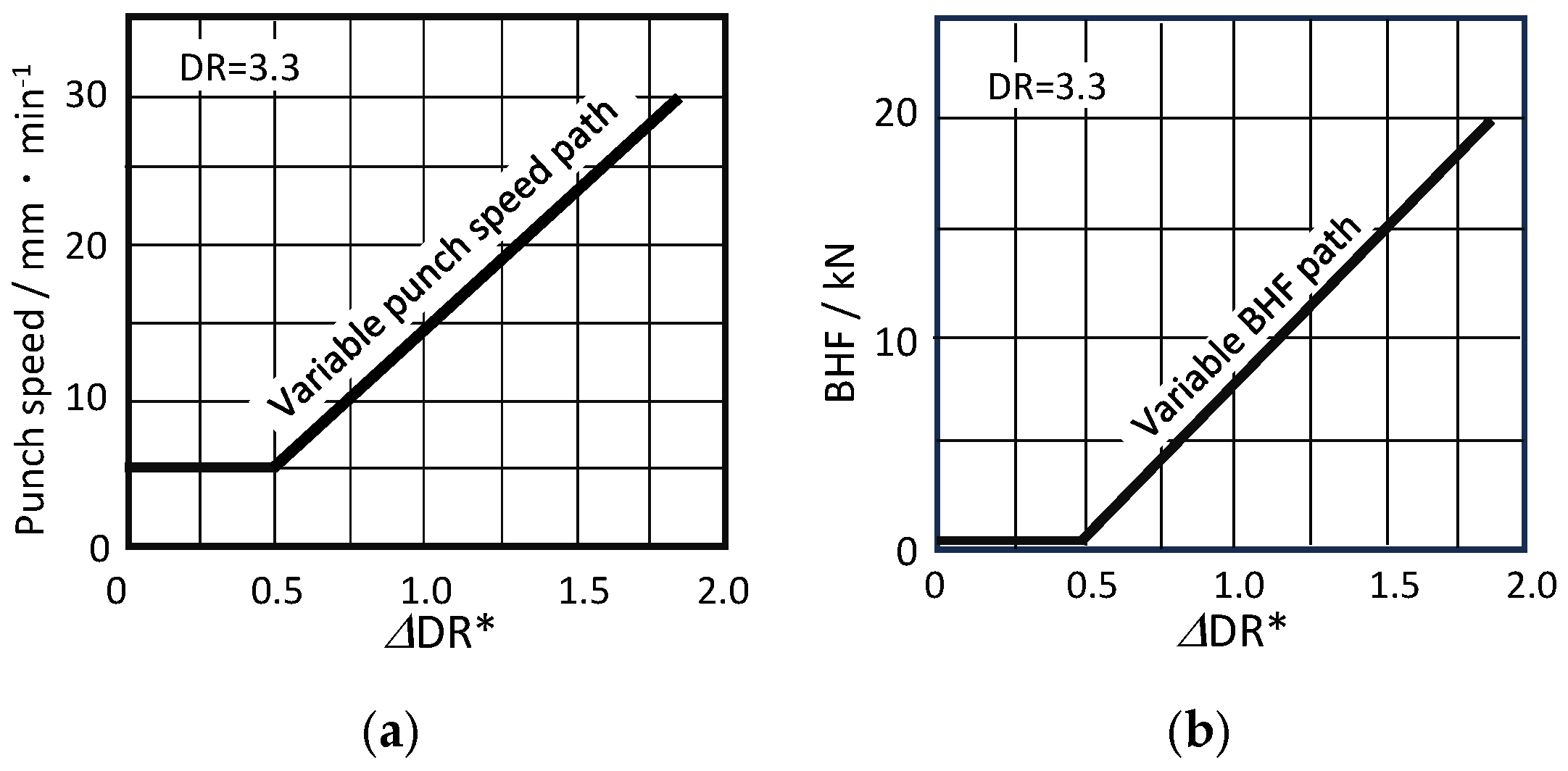

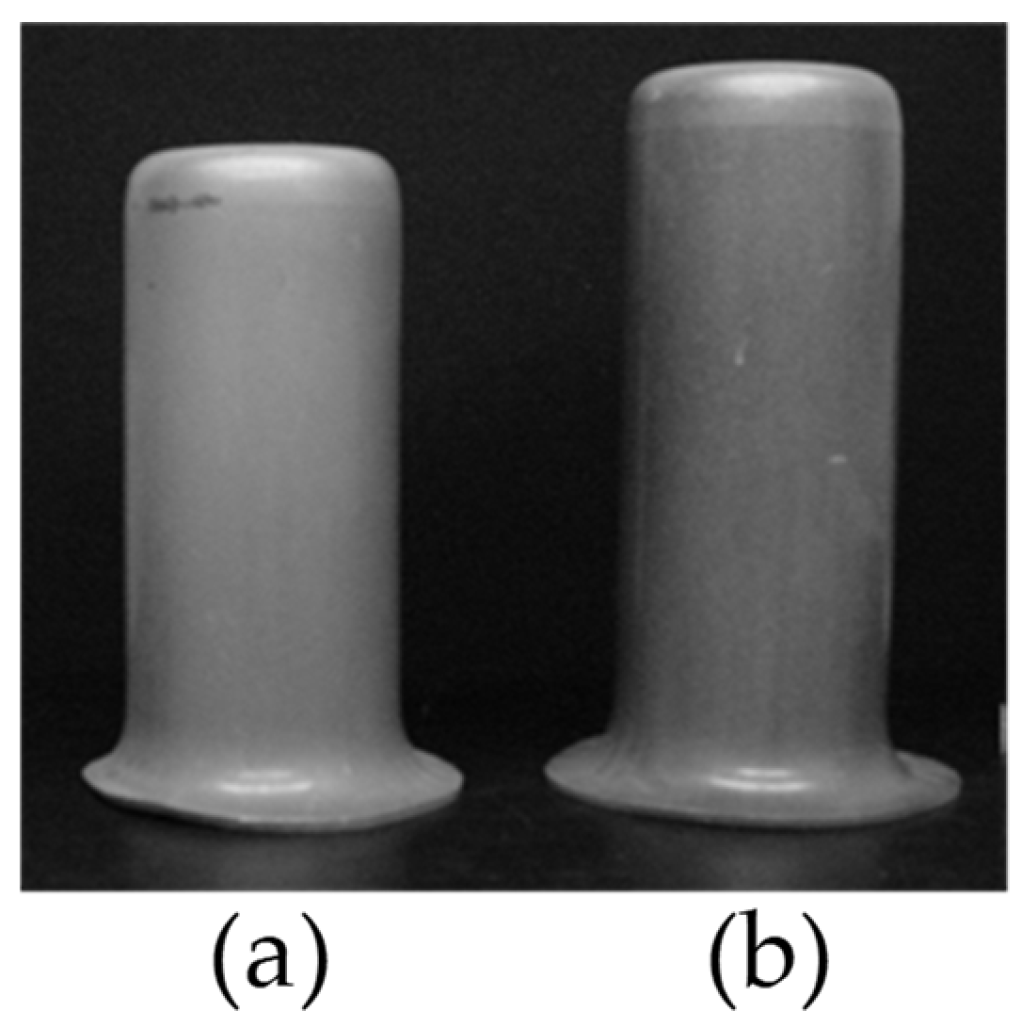

4.3. Novel Forming Principle Combining VSPD/VBHF Processing Path (DR = 3.3)

5. Conclusions

- Experiments using the aluminum alloy A5182 experimentally verified that warm deep drawing using a combined VSPD/VBHF path technique is an innovative forming process that simultaneously achieves a shortened forming time, improved forming limits, and a uniform wall thickness distribution. A large degree of reduction (DR) of 3.3 was achieved in the warm deep drawing of A5182. This was due to the moderate strain rate sensitivity index (m) value (=0.11) at a forming temperature of 300 °C, and the m value played a major role. This method is highly promising and a sustainable approach for application to other lightweight metals, and it is expected that new forming processes will be developed that make full use of the m value.

- The theoretical 3D process window (BHD-SPD-DDR* space) was consistent with the experimental results, demonstrating its applicability to process design. It became clear that the existence of Vcro holds the key to the suitability of applying the new VSPD/VBHF process to the design and development.

- The optimization of VSPD/VBHF paths remains a challenge, and advanced numerical approaches using multiphysics models and optimization algorithms are expected to significantly improve their prediction accuracy and fully automate the complex path design process for industrial implementation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| BHF | blank holder force |

| DR | drawing ratio (=Ro/r2) |

| DR* | current drawing ratio (=r0/r2) |

| ΔDR* | flange reduction ratio (=DR − DR* = (R0 − r0)/r2) |

| Hcrf | critical blank holder force for fracture |

| Hcrw | critical blank holder force for flange wrinkle |

| K | |

| LDR | limiting drawing ratio |

| m | |

| n | |

| SPD | punch speed, v |

| Vcro | critical punch speed at constant punch speed condition (see Figure 7) |

| VBHF | variable blank holder force |

| VSPD | variable punch speed |

| mean equivalent strain rate | |

| μ | coefficient of friction between blank and tool |

| ρd = rd/to | relative die shoulder radius |

| σal | allowable fracture stress of blank material |

| mean equivalent stress | |

| ωcr | allowable specific wrinkle height |

References

- Trzepieci’nski, T. Recent developments and trends in sheet metal forming. Metals 2020, 10, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepieci’nski, T.; Pieja, T.; Malinowski, T.; Smusz, R.; Motyka, M. Investigation of 17-4PH steel microstructure and conditions of elevated temperature forming of turbine engine strut. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 252, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y. Warm deep drawing method of stainless steel sheet. J. JSTP 1992, 37, 396–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kotkunde, N.; Hansoge, N.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kumar, S.; Gangadhar, J. Experimental and numerical investigations on hot deformation behavior and processing maps for ASS 304 and ASS 316. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2018, 37, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, E.; Kadkhodayan, M. An experimental investigation into the warm deep-drawing process on Laminated sheets under various grains sizes. Mater. Des. 2015, 87, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Shinomiya, T.; Morimoto, M.; Aikawa, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Shirakawa, N. Development of highly productive warm drawing using high frequency induction heating with ring shaped heating coils. Bull. JSTP 2020, 3, 735–739. [Google Scholar]

- Toros, S.; Ozturk, F.; Kacar, I. Review of warm forming of aluminum-magnesium alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 207, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, T.; Yoshida, F. Deep drawability of type 5083 aluminum–magnesium alloy sheet under various conditions of temperature and forming speed. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1999, 89/90, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohwue, T.; Takata, K.; Saga, M.; Kikuchi, M. Deep drawability of 5000 series aluminum alloy sheets in warm working condition. J. Jpn. Inst. Light Met. 2000, 50, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt1, P.J.; Werkhoven, R.J.; van den Boogaard, A.H. Warm deep drawing of aluminium sheet. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Sheet Metal, SheMet 2003, Jordantown, UK, 14–16 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara, S.; Nishimura, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Manabe, K. Formability enhancement in magnesium alloy stamping using a local heating and cooling technique: Circular cup deep drawing process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003, 142, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, K.; Yoshihara, S.; Nishimura, H.; Shibata, A. Theoretical analysis of punch speed and blank holder force control; in deep drawing process of strain-rate-Sensitive materials. In Proceedings of the ASME Dynamics Systems and Control Division ASME, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–22 November 1996; pp. 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Manabe, K.; Soeda, K.; Shibata, A. Effects of variable punch speed and blank holder force in warm superplastic deep drawing process. Metals 2021, 11, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagami, T.; Manabe, K. FE analysis on deformation mechanism of strain-rate-sensitive materials in cylindrical deep-drawing with combination punch speed and blank holder control. J. Solid Mech. Mater. Eng. 2007, 1, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, K.; Koyama, H.; Yoshihara, S.; Yagami, T. Development of a combination Punch-Speed and Blank-Holder Control System for the Deep Drawing Process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 125/126, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Koç, M.; Ni, J. Development of an analytical model for warm deep drawing of aluminum alloys. J. Materi. Process. Technol. 2008, 197, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuda, H.; Mori, K.; Masuda, I.; Abe, Y.; Matsuo, M. Finite element simulation of warm deep drawing of aluminium alloy sheet when accounting for heat conduction. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 120, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, H.; Coër, J.; Manach, P.Y.; Oliveira, M.C.; Menezes, L.F. Experimental and numerical studies on the warm deep drawing of an Al–Mg alloy. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 93, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.M.; Martins, J.M.P.; Cunha, P.M.; Alves, J.L.; Oliveira, M.C.; Laurent, H.; Menezes, L.F. Thermo-mechanical finite element analysis of the AA5086 alloy under warm forming conditions. Int. J. Solid. Struct. 2018, 151, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, K.; Hamano, H.; Nishimura, H. A new variable blank holding force method in deep drawing of sheet materials. J. JSTP 1988, 29, 740–747. [Google Scholar]

- Manabe, K.; Yoshihara, S.; Yang, M.; Nishimura, H. Fuzzy controlled variable blank holding force technique for circular cup deep drawing of aluminum alloy sheet. In Technical Papers of the North American Manufacturing Research Institution of SME 1995; Society of Manufacturing Engineers (SME): Dearborn, MI, USA, 1995; pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

| Temperature/°C | K/MPa | m | n | Strain Range | Strain Rate Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 258 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 10−2 < ε < 1 | 10−3 < < 7 × 10−2 |

| Punch diameter 2r1/mm | 32 | Punch shoulder radius rp/mm | 5 |

| Punch speed (SPD)/mm∙min−1 | 5~1000 | Blank holder force (BHF)/kN | 0.15~50 |

| Temperature/°C | 300 | Blank diameter 2Ro/mm | 88.8, 110, 117 (DR = 2.5, 3.1, 3.3) |

| Lubricant | A spray-type dry fluorine lubricant “Yunon S” (VALQUA, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) | ||

| Processing Path | Forming Time/s |

|---|---|

| Constant SPD/BHF method (SPD = 15 mm/min, BHF = 1 kN) | 320 |

| VSPD method under constant BHF = 1 kN | 129 |

| Combined VSPD/VBHF method (modified VSPD path) | 134 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshihara, S.; Shibata, A.; Manabe, K.-i. Experimental Verification of Forming Characteristics Enhancement by Combined Variable Punch Speed/Blank Holder Force Process Path in Warm Deep Drawing of A5182 Aluminum Alloy. Metals 2025, 15, 1329. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121329

Yoshihara S, Shibata A, Manabe K-i. Experimental Verification of Forming Characteristics Enhancement by Combined Variable Punch Speed/Blank Holder Force Process Path in Warm Deep Drawing of A5182 Aluminum Alloy. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1329. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121329

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshihara, Shoichiro, Akinori Shibata, and Ken-ichi Manabe. 2025. "Experimental Verification of Forming Characteristics Enhancement by Combined Variable Punch Speed/Blank Holder Force Process Path in Warm Deep Drawing of A5182 Aluminum Alloy" Metals 15, no. 12: 1329. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121329

APA StyleYoshihara, S., Shibata, A., & Manabe, K.-i. (2025). Experimental Verification of Forming Characteristics Enhancement by Combined Variable Punch Speed/Blank Holder Force Process Path in Warm Deep Drawing of A5182 Aluminum Alloy. Metals, 15(12), 1329. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121329