Cryoneurolysis: An Emerging Personalized Treatment Strategy for Significant Pelvic Pain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cryoneurolysis Mechanism of Action

3. Anatomic Targets in the Pelvis

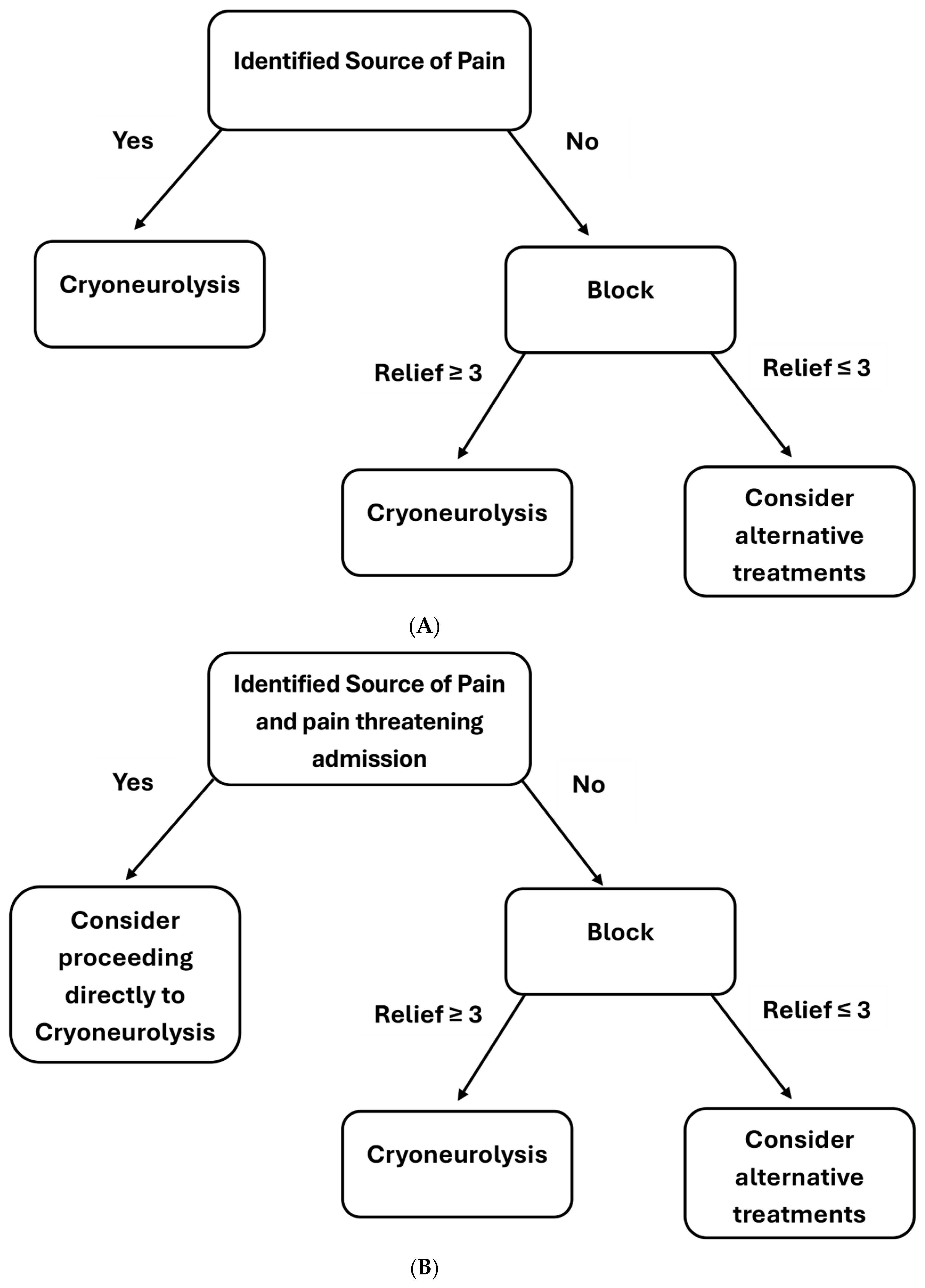

4. Patient Workup and Technique

4.1. Technique

4.2. Available Literature

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murphy, B.S.; Falls, N. Implementation of opioid stewardship programs (OSPs) in hospitals: A narrative literature review. J. Opioid Manag. 2025, 21, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, A.; Mansour, K. Improving Patient Care in Hand Surgery Through Non-narcotic Postoperative Pain Control Regimens. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 56, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butiulca, M.; Stoica Buracinschi, F.; Lazar, A. Ultrasound-Guided PECS II Block Reduces Periprocedural Pain in Cardiac Device Implantation: A Prospective Controlled Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sag, A.A.; Bittman, R.; Prologo, F.; Friedberg, E.B.; Nezami, N.; Ansari, S.; Prologo, J.D. Percutaneous Image-guided Cryoneurolysis: Applications and Techniques. Radiographics 2022, 42, 1776–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Garcia, R.M.; Prologo, J.D. Image-guided peripheral nerve interventions- applications and techniques. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 27, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prologo, J.D.; Edalat, F.; Moussa, M. Interventional Cryoneurolysis: An Illustrative Approah. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 23, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittman, R.W.; Peters, G.L.; Newsome, J.M.; Friedberg, E.B.; Mitchell, J.W.; Knigth, J.M.; Prologo, J.D. Percutaneous Image-Guided Cryonerurolysis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018, 210, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathias, S.D.; Kuppermann, M.; Liberman, R.F.; Lipschutz, R.C.; Steege, J.F. Chronic pelvic pain: Prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 87, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gish, B.; Langford, B.; Sobey, C.; Singh, C.; Adullah, N.; Walker, J.; Gray, H.; Hagedorn, J.; Ghosh, P.; Patel, K.; et al. Neuromodulation for the management of chronic pelvic pain syndromes: A systematic review. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfeki, H.; Alharbi, R.A.; Juul, T.; Drewes, A.M.; Christensen, P.; Laurberg, S.; Emmertsen, K.J. Chronic pain after colorectal cancer treatment: A population-based cross-sectional study. Colorectal Dis. 2025, 27, e17296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeve, C.; Gao, G.; Stephenson, V.; Helland, R.; Jeffery, A.D. Impact of chronic pelvic pain on quality of life in diverse young adults. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 10, 3147–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natuhwera, G.; Ellis, P. The Impact of Chronic Pelvic Pain and Bowel Morbidity on Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer Patients Treated with Radio (Chemo) Therapy. A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pain Res. 2025, 6, 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploteau, S.; Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Levesque, A.; Robert, R.; Nizard, J. New concepts on functional chronic pelvic and perineal pain: Pathophysiology and multidisciplinary management. Discov. Med. 2015, 19, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Conic, R.R.Z.; Kaur, P.; Kohan, L.R. Pudendal Neuralgia: A Review of the Current Literature. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2025, 29, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Lassaux, A.; Rioult, B.; Rabischong, B.; Khalfallah, M.; Volteau, C.; Leroi, A.; Ploteau, S. Adding corticosteroids to the pudendal nerve block for pudendal neuralgia: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. BJOG 2017, 124, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolak, S.; Antolak, C.; Lendway, L. Measuring the Quality of Pudendal Nerve Injections. Pain Physician 2016, 19, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancaillie, T.; Eggermont, J.; Armstrong, G.; Jarvis, S.; Liu, J.; Beg, N. Response to pudendal nerve block in women with pudendal neuralgia. Pain Med. 2012, 13, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannantoni, A.; Porena, M.; Gubbiotti, M.; Maddonni, S.; Di Stasi, S.M. The efficacy and safety of duloxetine in a multidrug regimen for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology 2014, 83, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wu, O.; Vincent, K.; Jack, S.A.; Critchley, H.O.D.; APorter, M.; Cranley, D.; AWilson, J.; Horne, A.W. Gabapentin for the Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women (GaPP1): A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Lin, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, X.N.; Yang, Y.; Liu, N.; Jiang, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Clinical efficacy evaluation and prevention of adverse reactions in a randomized trial of combination of three drugs in the treatment of cancerous pudendal neuralgia. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 5754–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krijnen, E.A.; Schweitzer, K.J.; van Wijck, A.J.M.; Withagen, M.J. Pulsed Radiofrequency of Pudendal Nerve for Treatment in Patients with Pudendal Neuralgia. A Case Series with Long-Term Follow-Up. Pain Pract. 2021, 21, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, F.; Zhou, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H. Therapeutic Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided High-Voltage Long-Duration Pulsed Radiofrequency for Pudendal Neuralgia. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 9961145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ye, L.; Wang, X. Clinical effect and safety of pulsed radiofrequency treatment for pudendal neuralgia: A prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Pain Res. 2018, 16, 2367–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, M.D.; Xi, Y.; Patel, A.A.; Scott, K.M.; Jones, S.; Chhabra, A. Initial experience of CT-guided pulsed radiofrequency ablation of the pudendal nerve for chronic recalcitrant pelvic pain. Clin. Radiol. 2019, 74, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istek, A.; Ugurlucan, F.G.; Yasa, C.; Gokyildiz, S.; Yalcin, O. Randomized trial of long-term effect of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on chronic pelvic pain. Arch. Gunecol Obstet. 2014, 290, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziev, G.; Topazio, L.; Iacovelli, V.; Asimakopoulos, A.; Di Santo, A.; De Nunzio, C.; Finazzi-Agrò, E. Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation (PTNS) efficacy in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctions: A systematic review. BMC Urol. 2013, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Balken, M.R.; Vandoninck, V.; Messelink, B.J.; Vergunst, H.; Heesakkers, J.P.F.A.; Debruyne, F.M.J. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulative treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur. Urol. 2003, 43, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, M.; Boccasanta, P.; Lombardi, B.; Brambilla, M.; Avesani, E.C.; Vergani, C. Pudendal Neuralgia: A New Option for Treatment? Preliminary Results on Feasibility and Efficacy. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalife, T.; Hagen, A.M.; Alm, J.E.C. Retroperitoneal Causes of Genitourinary Pain Syndromes: Systematic Approach to Evaluation and Management. Sex. Med. Rev. 2022, 10, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wie, C.; Ghanavatian, S.; Pew, S.; Kim, A.; Strand, N.; Freeman, J.; Maita, M.; Covington, S.; Maloney, J. Interventional Treatment Modalities for Chronic Abdominal and Pelvic Visceral Pain. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2022, 26, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Khan, A.R.; Saini, S.; Naimat, A.; Amudha, C.; Bannur, D.; Ajayi, E.; Rehman, A.; Shah, S.; Fakhruddin, N.M.; et al. Cryoneurolysis: A comprehensive review of Applications in Pain management. Cureus 2025, 17, e79448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trescot, A.M. Cryoanalgesia in interventional pain management. Pain Physician 2003, 6, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.M.; Dawber, R.P. The history of cryosurgery. J. R. Soc. Med. 2001, 94, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, A.A. History of cryosurgery. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1998, 14, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baust, J.G.; Gage, A.A. The molecular basis of cryosurgery. BJU Int. 2005, 95, 1187–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biel, E.; Aroke, E.N.; Maye, J.; Zhang, S.J. The applications of cryoneurolysis for acute and chronic pain management. Pain Pract. 2023, 23, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prologo, J.D.; Manyapu, S.; Bercu, Z.L.; Mittal, A.; Mitchell, J.W. Percutaneous CT-Guided Cryoablation of the Bilateral Pudendal Nerves for Palliation of Intractable Pain Related to Pelvic Neoplasms. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020, 37, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

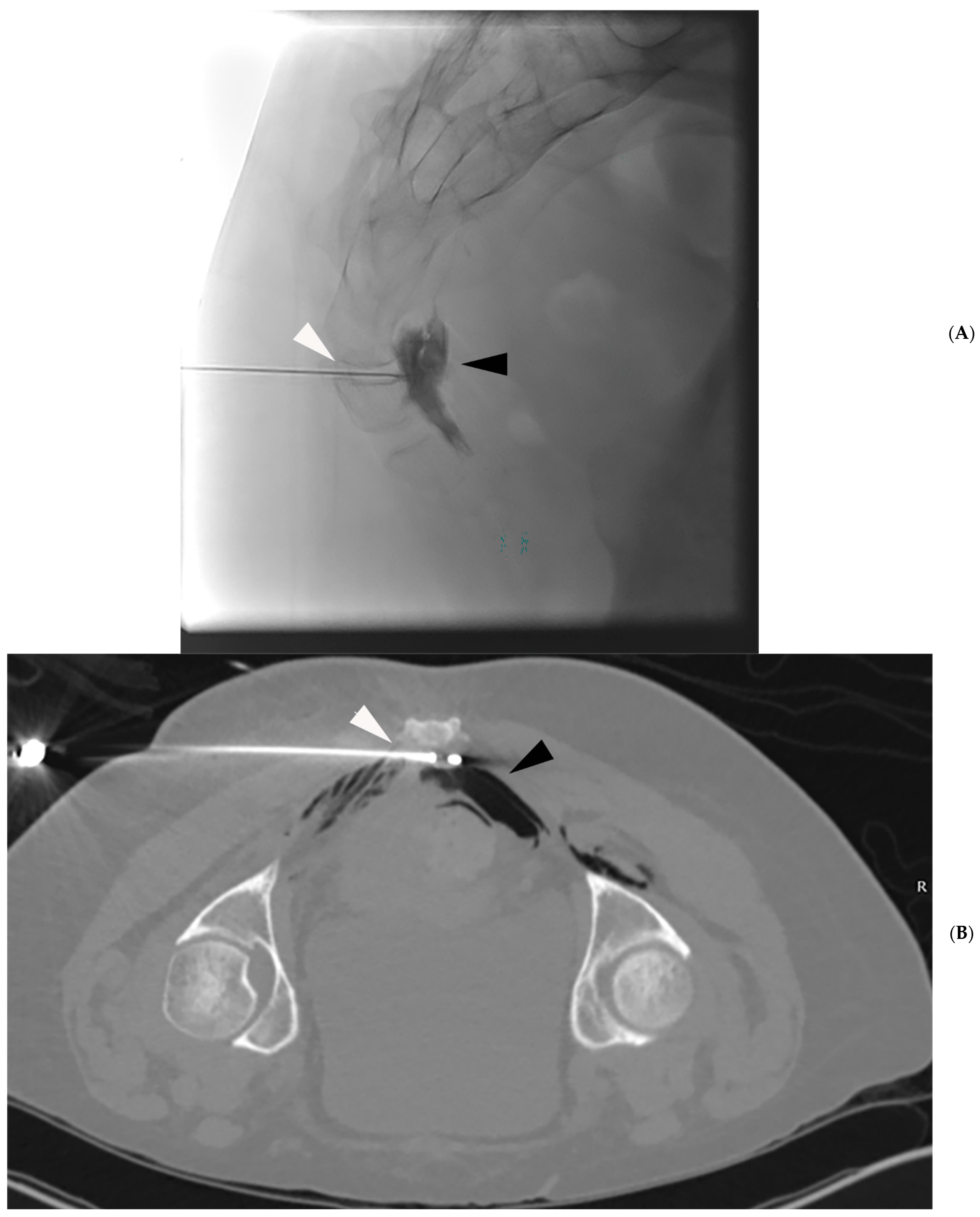

- Prologo, J.D.; Lin, R.C.; Williams, R.; Corn, D. Percutaneous CT-guided cryoablation for the treatment of refractory pudendal neuralgia. Skeletal Radiol. 2015, 44, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.E.; Grechushkin, V.; Chaudhry, A.; Bhattacharji, P.; Durkin, B.; Moore, W. Cryoneurolysis in Patients with Refractory Chronic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 27, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finneran, J.J.; Kobayashi, L.; Costantini, T.W.; Weaver, J.L.; Berndtson, A.E.; Haines, L.; Doucet, J.J.; Adams, L.; Santorelli, J.E.; Lee, J.; et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous Cryoneurolysis for the Treatment of Pain after Traumatic Rib Fracture: A randomized, Active-controlled, Participant- and Observer-masked Study. Anesthesiology 2025, 142, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Finneran, J.J.; Swisher, M.W.; Said, E.T.; Gabriel, R.A.; Sztain, J.F.; Khatibi, B.; Armani, A.; Trescot, A.; Donohue, M.C.; et al. Preoperative Ultrasound-guided Percutaneous Cryoneurolysis for the Treatment of Pain after Mastectomy: A Randomized, Participant- and Observer-masked, Shan-controlled Study. Anesthesiology 2022, 37, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foy, C.A.; Kuffler, D.P. Limitations to clinically restoring meaningful peripheral nerve function across gaps and overcoming them. Exp. Biol. Med. 2025, 250, 10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, J.C.; Ali, Z.S.; Zager, E.L.; Rosen, J.M.; Tatarchuk, M.M.; Cullen, D.K. Engineering the Future of Restorative Clinical Peripheral Nerve Surgery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2404293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Xue, J.; Ge, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Li, Y. Emerging therapeutic strategies for optic nerve regeneration. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailaud, M.; Richard, L.; Vallat, J.M.; Desmouliere, A.; Billet, F. Peripheral nerve regeneration and intraneural revascularization. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menorca, R.M.; Fussell, T.S.; Elfar, J.C. Nerve physiology: Mechanisms of injury and recovery. Hand Clin. 2013, 29, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Choi, Y.M.; Jang, E.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, T.K.; Kim, K.H. Neural Ablation and Regeneration in Pain Practice. Korean J. Pain 2016, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.J.; Lavernia, C.J.; Owens, P.W. Anatomy and physiology of peripheral nerve injury and repair. AM J. Orthop. 2000, 29, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tinnirello, A.; Marchesini, M.; Mazzoleni, S.; Santi, C.; Lo Bianco, G. Innovations in Chronic Pain Treatment: A Narrative Review of the Role of Cryoneurolysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, A.; Latich, I.; Levey, A.O. Common Cryoneurolysis Targets in Pain Management: Indications, Critical Anatomy, and Potential Complicaitons. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 42, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, A.; Edalat, F. Celiac Plexus Cryoneurolysis. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 39, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finneran, J.J.; Illfeld, B.M. Percutaneous cryoneurolysis for acute pain management: Current status and future prospects. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2021, 18, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prologo, J.D. Percutaneous CT-Guided Cryovagotomy. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 23, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Kambin, P.; Casey, K.F.; Bonner, F.J.; O’Brien, E.; Shao, Z.; Ou, S. Mechanism research of cryoanalgesia. Neurol. Res. 1995, 17, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Bem, G.; Agrelo, A. Ganglion impar block in chronic cancer-related pain—A review of the current literature. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 71, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.W.; Tumber, P.S. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain—A description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician 2008, 11, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkan, I.B.O.; Gorgun, E. Cadaveric Insights into Pudendal Nerve Variations for Sacrospinous Ligament Fixation: A Case Series. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2024, 35, 2385–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploteau, S.; Perrouin-Verbe, M.A.; Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Levesque, A.; Robert, R. Anatomical Variants of the Pudendal Nerve Observed during a Transgluteal Surgical Approach in a Population of Patients with Pudendal Neuralgia. Pain Physician 2017, 20, E137–E143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, H.; Kalava, A. Ischiorectal Approach to Cryoablation of the Pudendal Nerve Using a Handheld Device: A Report of Two Cases. Cureus 2023, 15, e44377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Yang, M.; Won, H.S.; Kim, Y.D. Coccdynia: Anatomic origin and considerations regarding the effectiveness of injections for pain management. Korean J. Pain 2023, 36, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.S.; Chung, I.H.; Ji, H.J.; Yoon, D.M. Clinical implications of topographic anatomy on the ganglion impar. Anesthesiology 2004, 101, 249–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwamide, O.; Syed, A.; Mehta, J.; Andrawis, M.; Zhang, H. Ganglion Impar Neurolysis to Treat Refractory Chronic Pain from Vulvar Cancer: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e70128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Phogat, V.; Sinha, N.; Kumar, A.; Charan, N. Arun Comparison of radiofrequency thermocagulation of ganglion Impar with block using a combination of local anesthetic steroid in chronic perineal pain. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 41, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puljak, L.; Boric, K.; Dosenovic, S. Pain assessment in clinical trials: A narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, D.C.; Dworkin, R.H.; Allen, R.R.; Bellamy, N.; Bradenburg, N.; Carr, D.B.; Cleeland, C.; Dionne, R.; Farrar, J.T.; Galer, B.S.; et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2003, 106, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramyan, A.; Shaub, D.; Kalarn, S.; Fitzgerald, Z.; Goldberg, D.; Hannallah, J.; Woodhead, G.; Young, S. Including the bowel within the iceball during cryoablation: A retrospective single-center review of adverse events. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, H.; Feng, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, B.X. The potential role of nerve growth factor in Cryoneurolysis-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Cryobiology 2012, 65, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, H.; Dureja, G.P.; Andleeb, R.; Tauheed, N.; Asif, N. Conventional Radiofrequency Thermocoagulation vs Pusled Radiofrequency Neuromodulation of Ganglion Impar in Chronic Perineal Pain of Nononcological Origin. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 2348–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal-Kozlowski, K.; Lorke, D.E.; Habermann, C.R.; Am Esch, J.S.; Beck, H. CT-guided blocks and neuroablation of the ganglion impar (Walther) in perineal pain: Anatomy, technique, safety, and efficacy. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Number of Patients | Type of Pain | VAS | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prologo et al. [37] | 10 | Cancer | 5.2 # | None |

| Prologo et al. [38] | 11 | Non-Cancer | Pre: 7.6 24 H post: 2.6 45 D post: 3.5 6 M post: 3.1 | None |

| Hampton et al. [59] | 2 | Non-Cancer | 25–85% reduction | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, S.; Abramyan, A.; Vittoria De Martini, I.; Hannallah, J.; Woodhead, G.; Struycken, L.; Goldberg, D. Cryoneurolysis: An Emerging Personalized Treatment Strategy for Significant Pelvic Pain. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120587

Young S, Abramyan A, Vittoria De Martini I, Hannallah J, Woodhead G, Struycken L, Goldberg D. Cryoneurolysis: An Emerging Personalized Treatment Strategy for Significant Pelvic Pain. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120587

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Shamar, Artyom Abramyan, Ilaria Vittoria De Martini, Jack Hannallah, Gregory Woodhead, Lucas Struycken, and Daniel Goldberg. 2025. "Cryoneurolysis: An Emerging Personalized Treatment Strategy for Significant Pelvic Pain" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120587

APA StyleYoung, S., Abramyan, A., Vittoria De Martini, I., Hannallah, J., Woodhead, G., Struycken, L., & Goldberg, D. (2025). Cryoneurolysis: An Emerging Personalized Treatment Strategy for Significant Pelvic Pain. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120587