Two-Plate Splintless Repositioning in Bimaxillary Surgery: Accuracy and Influence of Segmental Osteotomies in a Consecutive Single-Centre Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Acquisition

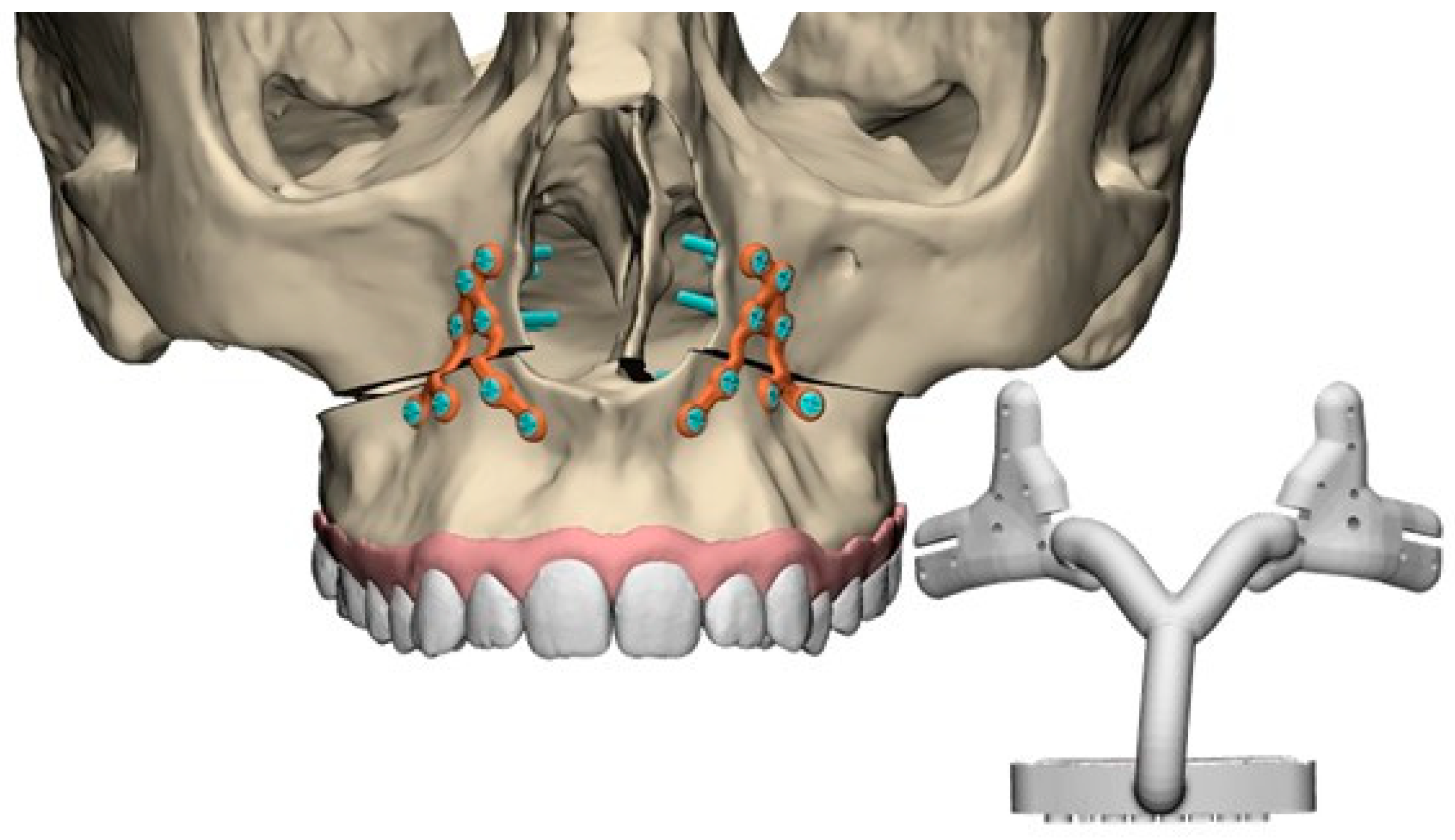

2.3. Virtual Surgical Planning

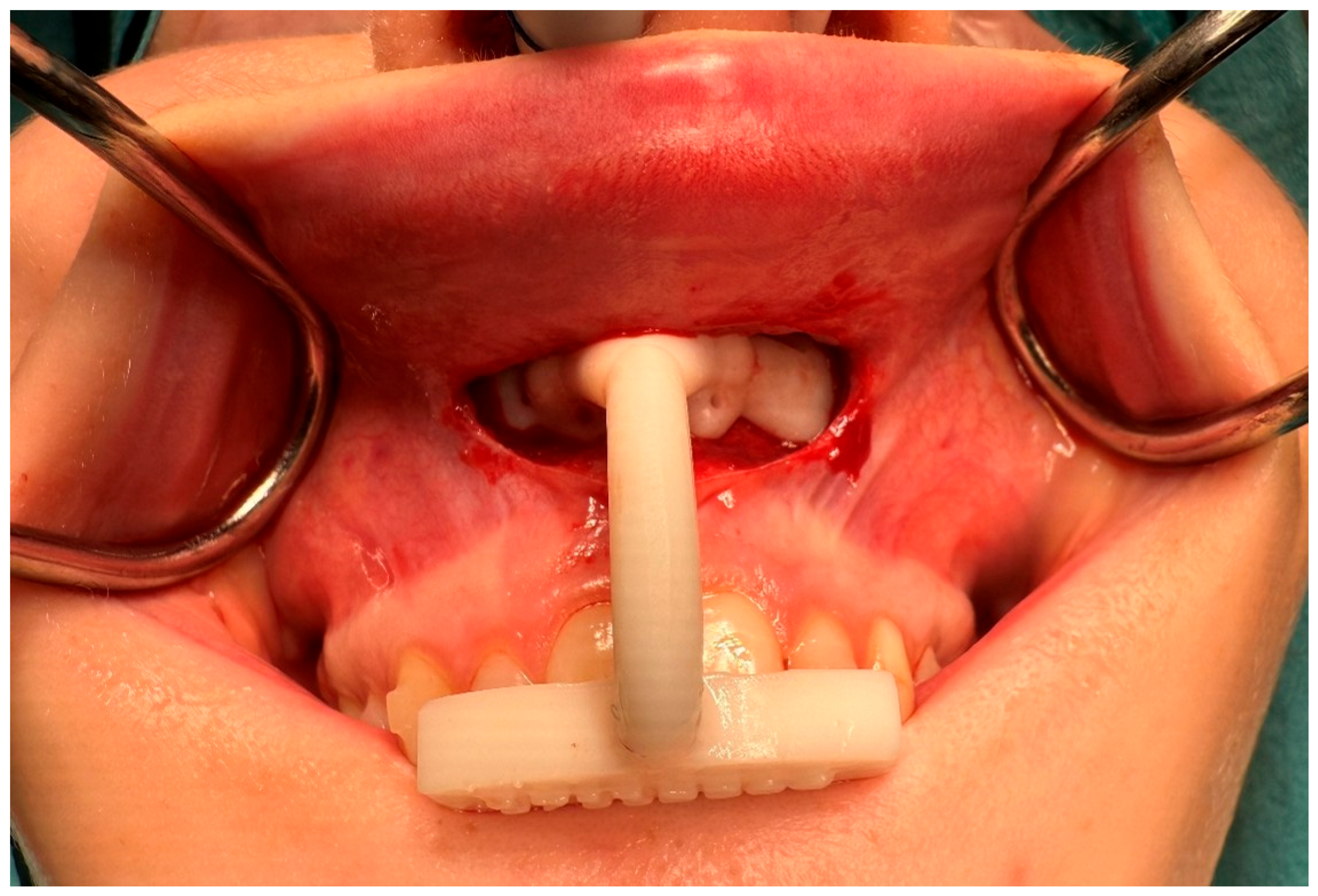

2.4. Surgical Procedure

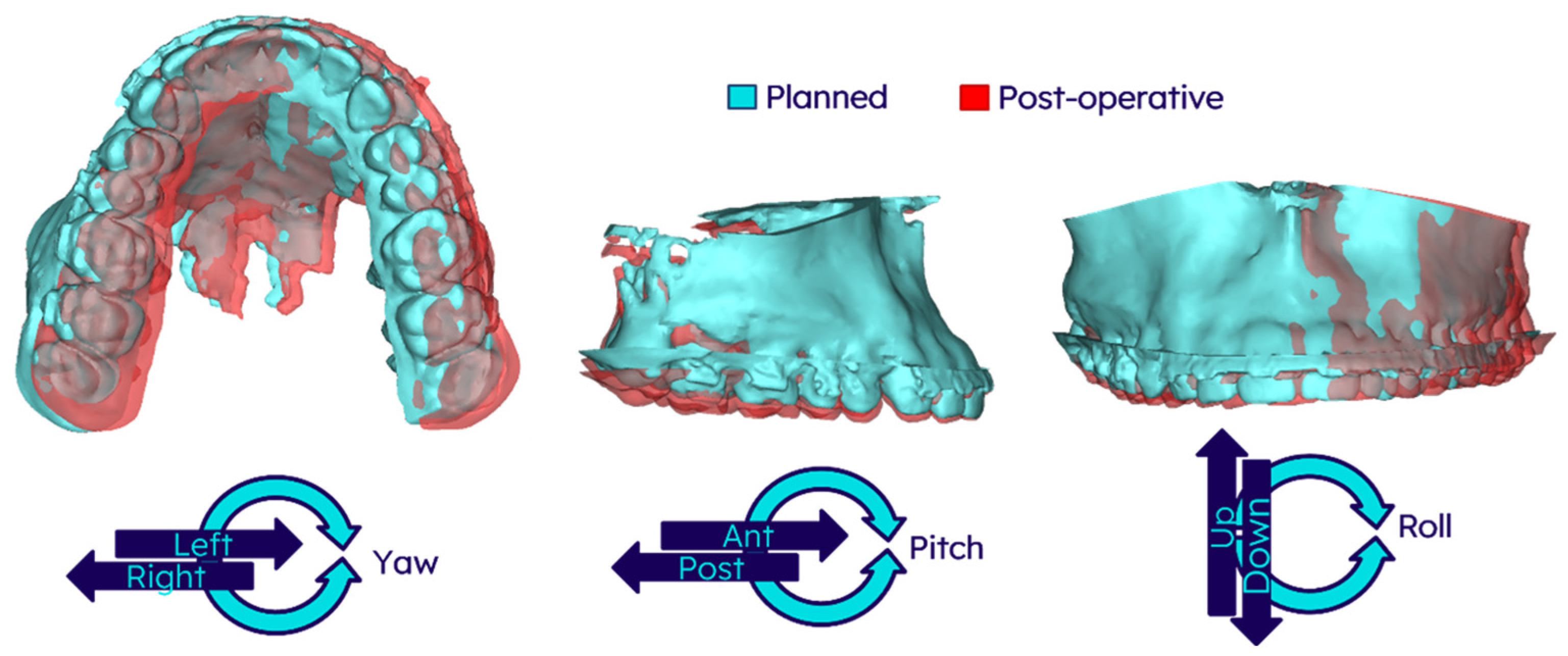

2.5. Post-Operative Evaluation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Data

3.2. Accuracy of the Surgery

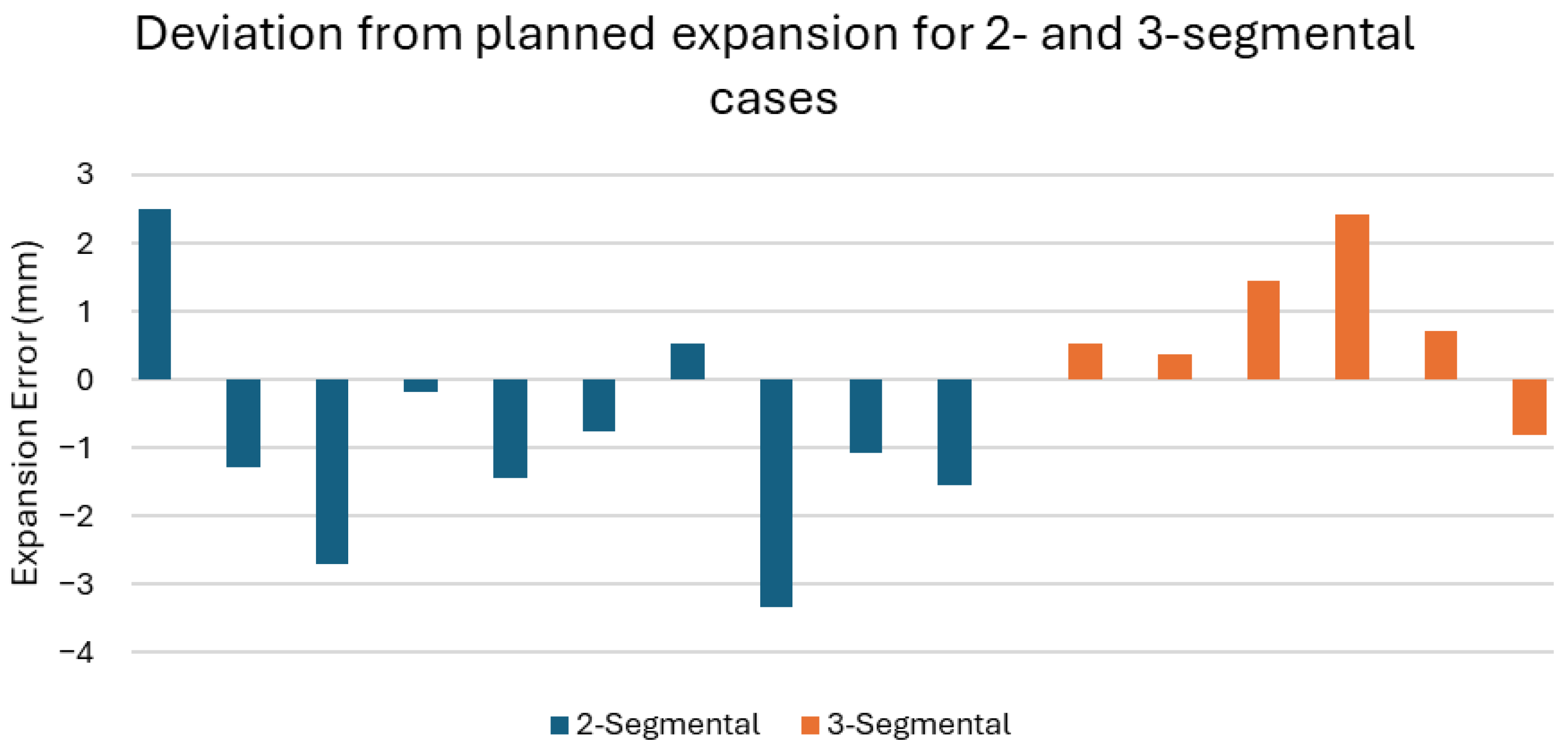

3.3. Accuracy of Segment Osteotomies

3.4. Categorisation of Clinical Accuracy

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Pitch

4.3. Segments and Palatal Expansion

4.4. Longer-Term Stability of the Result

4.5. Exclusion of CBCT Scans Due to Stitching Error

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Proffit, W.R.; Turvey, T.A.; Phillips, C. The Hierarchy of Stability and Predictability in Orthognathic Surgery with Rigid Fixation: An Update and Extension. Head. Face Med. 2007, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokbro, K.; Aagaard, E.; Torkov, P.; Bell, R.B.; Thygesen, T. Virtual Planning in Orthognathic Surgery. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.B.; da Silva, L.E.; de Oliveira Caetano, M.T.; da Motta, A.F.J.; de Alcantara Cury-Saramago, A.; Mucha, J.N. Perception of Midline Deviations in Smile Esthetics by Laypersons. Dental Press. J. Orthod. 2016, 21, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaipatur, N.; Al-Thomali, Y.; Flores-Mir, C. Accuracy of Computer Programs in Predicting Orthognathic Surgery Hard Tissue Response. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wel, H.; Schepers, R.H.; Baan, F.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Jansma, J.; Kraeima, J. Maxilla-First Patient-Specific Osteosynthesis vs Mandible-First Bimaxillary Orthognathic Surgery Using Splints: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 54, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, A.; Holte, M.B.; Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Pinholt, E.M. Three-Dimensional Accuracy and Stability of Personalized Implants in Orthognathic Surgery: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.J.; Gateno, J.; Teichgraeber, J.F.; Christensen, A.M.; Lasky, R.E.; Lemoine, J.J.; Liebschner, M.A.K. Accuracy of the Computer-Aided Surgical Simulation (CASS) System in the Treatment of Patients With Complex Craniomaxillofacial Deformity: A Pilot Study. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paggi Claus, J.D.; Almeida, M.S.; Zille, D. Customization in Minimally Invasive Orthognathic Surgery. Adv. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 3, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alfaro, F.; Guijarro-Martínez, R. “twist Technique” for Pterygomaxillary Dysjunction in Minimally Invasive Le Fort i Osteotomy. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 71, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlAsseri, N.; Swennen, G. Minimally Invasive Orthognathic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Alfaro, F.; Saavedra, O.; Duran-Vallès, F.; Valls-Ontañón, A. On the Feasibility of Minimally Invasive Le Fort I with Patient-Specific Implants: Proof of Concept. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wel, H.; Glas, H.; Jansma, J.; Schepers, R. Accuracy of Patient-Specific Osteosynthesis in Bimaxillary Surgery: Comparative Feasibility Analysis of Four- and Two-Miniplate Fixation. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.A.; Upton, L.G.; Rottman, K.R. Comparison of the Postsurgical Stability of the Le Fort I Osteotomy Using 2- and 4-Plate Fixation. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavili, M.E.; Canter, H.I.; Saglam-Aydinatay, B. Semirigid Fixation of Mandible and Maxilla in Orthognathic Surgery: Stability and Advantages. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2009, 63, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susarla, S.M.; Ettinger, R.; Preston, K.; Kapadia, H.; Egbert, M.A. Two-Point Nasomaxillary Fixation of the Le Fort I Osteotomy: Assessment of Stability at One Year Postoperative. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyler, E.; Altıparmak, N.; Bayram, B. Comparison of the Postoperative Stability after Repositioning of the Maxilla with Le Fort I Osteotomy Using Four- versus Two-Plate Fixation. J. Stomatol. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 122, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.P.T.F.; Schreurs, R.; Baan, F.; de Lange, J.; Becking, A.G. Splintless Orthognathic Surgery in Edentulous Patients—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraeima, J.; Schepers, R.H.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Maal, T.J.J.; Baan, F.; Witjes, M.J.H.; Jansma, J. Splintless Surgery Using Patient-Specific Osteosynthesis in Le Fort I Osteotomies: A Randomized Controlled Multi-Centre Trial. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wei, H.; Jiang, T.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Randomized Clinical Trial of the Accuracy of Patient-Specific Implants versus CAD/CAM Splints in Orthognathic Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 148, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, R.; Reis, B.A.Q.; Lima, B.C.; Pinto, L.A.P.F.; Melhem-Elias, F. Comparison between 2- and 4-Plate Fixation in Le Fort I Osteotomy: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2025, 139, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Patient underwent a bimaxillary osteotomy | Unsuitable CBCT quality for analysis. |

| Patient was operated with a two-plate PSO system | |

| Availability of both pre- and post-operative CBCT scans. |

| Result | 2° Criteria | 4° Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal | <1 mm deviation in translation AND <2° deviation in roll/pitch/yaw | <1 mm deviation in translation AND <2° deviation in roll/pitch/yaw |

| Good | 1–2 mm deviation in translation AND <2° deviation in roll/pitch/yaw | 1–2 mm deviation in translation AND <4° deviation in roll/pitch/yaw |

| Suboptimal | >2 mm deviation in translation OR >2° deviation in roll/pitch/yaw | >2 mm deviation in translation OR >4° deviation in roll/pitch/yaw |

| Demographic | |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 47 |

| Mean age (years ± SD) | 27.9 ± 9.4 |

| No. of one-segment maxillary osteotomy patients | 31 |

| No. of two-segment maxillary osteotomy patients | 10 |

| No. of three-segment maxillary osteotomy patients | 6 |

| Median Planned Movement of the Maxilla | |

|---|---|

| Direction | Median [IQR] |

| Ant/Post (mm) | 5.0 (Ant) [3.8 (Ant)–6.5 (Ant)] |

| Left/Right (mm) | 0.0 [1.0 (Left)–0.0 (Right)] |

| Up/down (mm) | 0.0 [0.0 (Up)–2.0 (Down)] |

| Roll (°) | 0.1 (CCW) [1.8 (CCW)–1.5 (CW)] |

| Pitch (°) | 0.9 (CW) [1.7 (CCW)–4.9 (CW)] |

| Yaw (°) | 0.3 (CCW) [0.7 (CCW)–1.8 (CW)] |

| Direction | Median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Ant/Post (mm) | 0.7 [0.4–1.2] |

| Left/Right (mm) | 0.4 [0.2–0.7] |

| Up/down (mm) | 0.6 [0.2–1.1] |

| Roll (°) | 0.8 [0.5–1.2] |

| Pitch (°) | 1.6 [0.6–2.4] |

| Yaw (°) | 0.5 [0.3–1.2] |

| Direction | Correlation (r-Value) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Ant/Post (mm) | 0.080 | 0.592 |

| Left/Right (mm) | 0.285 | 0.052 |

| Up/down (mm) | −0.127 | 0.395 |

| Roll (°) | 0.311 | 0.034 |

| Pitch (°) | 0.316 | 0.031 |

| Yaw (°) | 0.201 | 0.175 |

| Landmark | Direction | 1-Segment (n = 31) | 2-Segment (n = 10) | 3-Segment (n = 6) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | |||

| Upper Incisor | Ant/Post (mm) | 0.7 [0.4–1.3] | 0.9 [0.5–1.4] | 0.5 [0.3–0.7] | 0.279 |

| Left/Right (mm) | 0.5 [0.2–0.7] | 0.5 [0.2–1.2] | 0.3 [0.1–0.8] | 0.596 | |

| Up/Down (mm) | 0.6 [0.3–1.1] | 0.9 [0.5–1.3] | 0.4 [0.1–0.9] | 0.209 | |

| Upper Canine | Ant/Post (mm) | 0.7 [0.4–1.3] | 1.3 [0.5–1.6] | 1.1 [0.6–1.9] | 0.420 |

| Left/Right (mm) | 0.4 [0.1–0.7] | 0.4 [0.3–1.1] | 1.0 [0.5–1.6] | 0.060 | |

| Up/Down (mm) | 0.5 [0.2–0.7] | 0.7 [0.4–1.1] | 0.6 [0.4–1.5] | 0.873 | |

| Upper First Molar | Up/Down (mm) | 0.8 [0.4–1.3] | 1.2 [0.5–1.8] | 0.9 [0.6–1.5] | 0.263 |

| Left/Right (mm) | 0.4 [0.2–0.7] | 0.7 [0.5–1.6] | 0.5 [0.3–1.3] | 0.065 | |

| Up/Down (mm) | 0.8 [0.5–1.4] | 0.8 [0.3–1.4] | 1.4 [0.3–1.5] | 0.634 |

| Planned Expansion (mm) | Realised Expansion (mm) | Absolute Error (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] |

| 3.0 [1.8–3.8] | 2.7 [1.3–3.2] | 1.2 [0.6–2.2] |

| Result | 2° Criteria | 4° Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal | 34.0% (16/47) | 34.0% (16/47) |

| Good | 17.0% (8/47) | 55.3% (26/47) |

| Suboptimal | 48.9% (23/47) | 10.6% (5/47) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van der Wel, H.; Zwijnenberg, T.L.; Jansma, J.; Schepers, R.H.; Glas, H.H. Two-Plate Splintless Repositioning in Bimaxillary Surgery: Accuracy and Influence of Segmental Osteotomies in a Consecutive Single-Centre Cohort. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120588

van der Wel H, Zwijnenberg TL, Jansma J, Schepers RH, Glas HH. Two-Plate Splintless Repositioning in Bimaxillary Surgery: Accuracy and Influence of Segmental Osteotomies in a Consecutive Single-Centre Cohort. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120588

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan der Wel, Hylke, Tom Lucas Zwijnenberg, Johan Jansma, Rutger Hendrik Schepers, and Haye Hendrik Glas. 2025. "Two-Plate Splintless Repositioning in Bimaxillary Surgery: Accuracy and Influence of Segmental Osteotomies in a Consecutive Single-Centre Cohort" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120588

APA Stylevan der Wel, H., Zwijnenberg, T. L., Jansma, J., Schepers, R. H., & Glas, H. H. (2025). Two-Plate Splintless Repositioning in Bimaxillary Surgery: Accuracy and Influence of Segmental Osteotomies in a Consecutive Single-Centre Cohort. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120588