The Role of High-Sensitivity Troponin I in Predicting Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHREs) in Patients with Permanent Pacemakers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Baseline Assessment

2.3. Biomarker Measurement

2.4. Outcome Definition and Follow-Up

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population and Baseline Characteristics

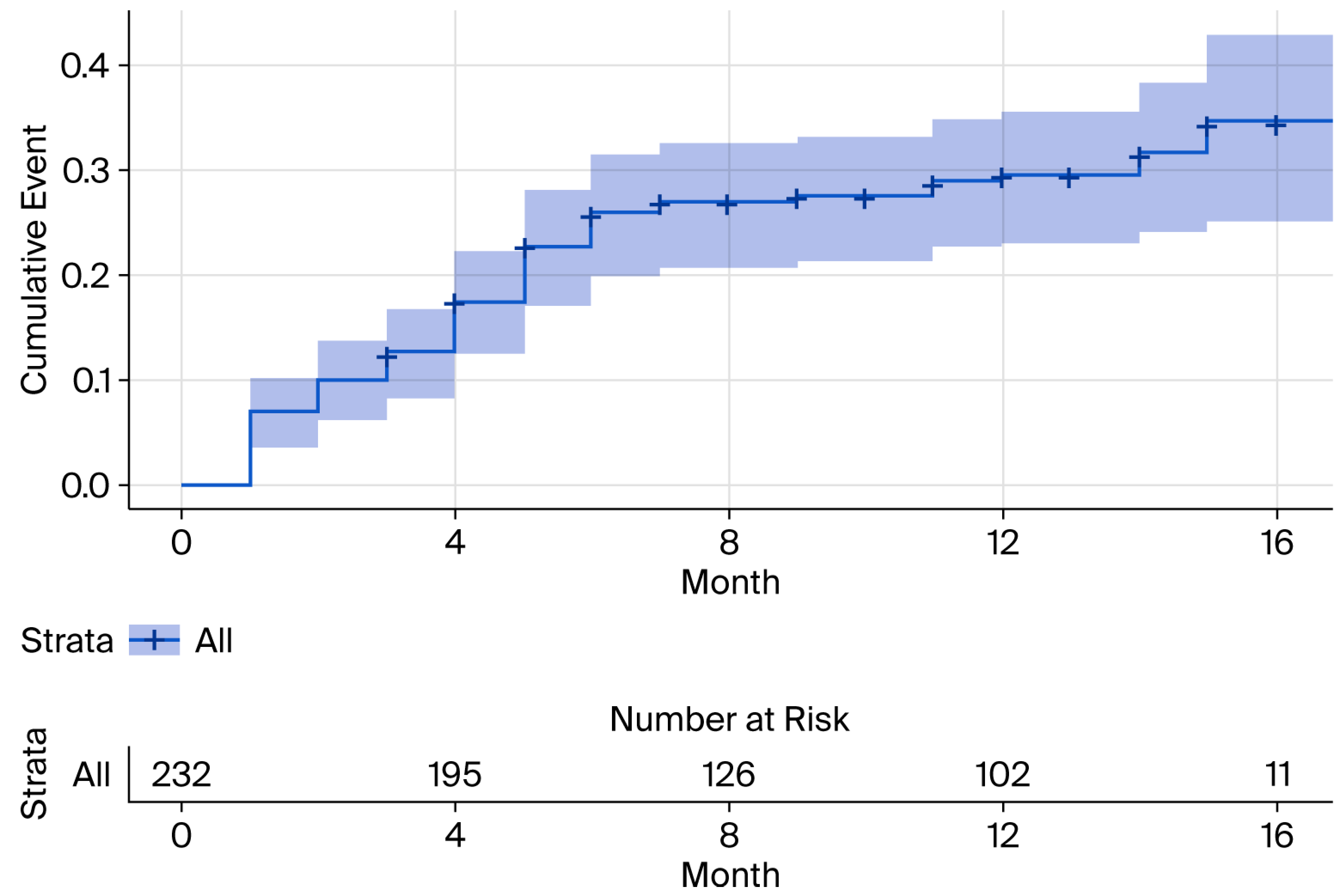

3.2. Incidence of Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHREs)

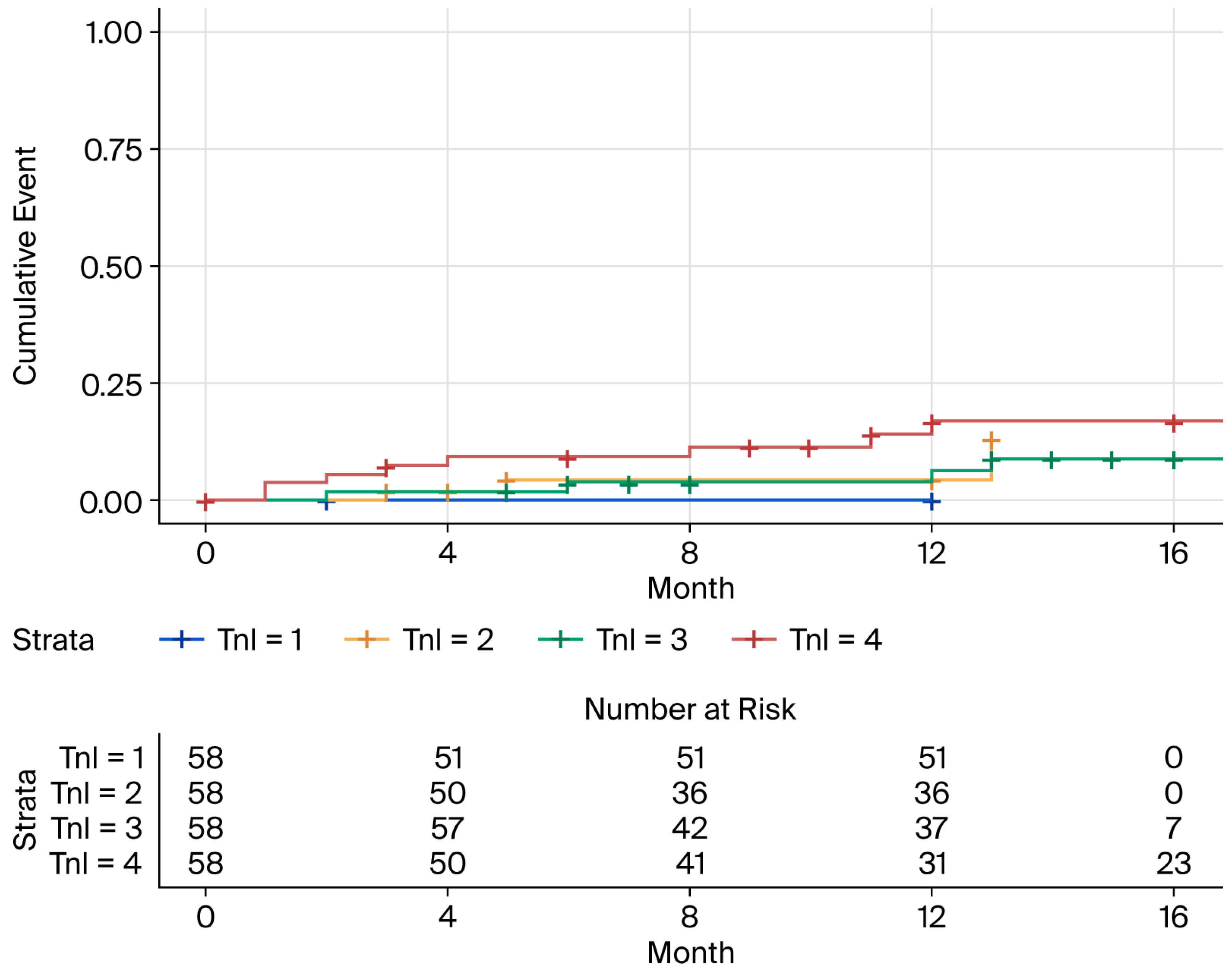

3.3. Baseline hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP Levels and Risk of New-Onset AHREs

3.4. Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis for Predictors of New-Onset AHREs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brundel, B.; Ai, X.; Hills, M.T.; Kuipers, M.F.; Lip, G.Y.H.; de Groot, N.M.S. Atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Cervellin, G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int. J. Stroke 2021, 16, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Gawalko, M.; Betz, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Vinter, N.; Guo, Y.; Johnsen, S. Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, screening and digital health. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennberg, E.; Freedman, B.; Andrade, J.G.; Anselmino, M.; Biton, Y.; Boriani, G.; Brandes, A.; Buckley, C.M.; Cameron, A.; Clua-Espuny, J.L.; et al. Recent-onset atrial fibrillation: Challenges and opportunities. Eur. Heart J. 2025, ehaf478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boriani, G.; Tartaglia, E.; Trapanese, P.; Tritto, F.; Gerra, L.; Bonini, N.; Vitolo, M.; Imberti, J.F.; Mei, D.A. Subclinical atrial fibrillation/atrial high-rate episodes: What significance and decision-making? Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2025, 27, i162–i166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletras, G.; Koutalas, E.; Bachlitzanaki, M.; Stratinaki, M.; Bachlitzanaki, I.; Stavratis, S.; Garidas, G.; Pitarokoilis, M.; Foukarakis, E. Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia and Troponin Elevation: Insights into Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Burbano, J.D.; Chara-Salazar, C.J.; Vargas-Zabala, D.L.; Castillo-Concha, J.S.; Agudelo-Uribe, J.F.; Ramirez-Barrera, J.D. Clinical relevance and management of atrial high-rate episodes: A narrative review. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.S.; Connolly, S.J.; Gold, M.R.; Israel, C.W.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Capucci, A.; Lau, C.P.; Fain, E.; Yang, S.; Bailleul, C.; et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaqat, S.; Rafaqat, S.; Ijaz, H. The Role of Biochemical Cardiac Markers in Atrial Fibrillation. J. Innov. Card. Rhythm. Manag. 2023, 14, 5611–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieweke, J.T.; Pfeffer, T.J.; Biber, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Weissenborn, K.; Grosse, G.M.; Hagemus, J.; Derda, A.A.; Berliner, D.; Lichtinghagen, R.; et al. miR-21 and NT-proBNP Correlate with Echocardiographic Parameters of Atrial Dysfunction and Predict Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borschel, C.S.; Geelhoed, B.; Niiranen, T.; Camen, S.; Donati, M.B.; Havulinna, A.S.; Gianfagna, F.; Palosaari, T.; Jousilahti, P.; Kontto, J.; et al. Risk prediction of atrial fibrillation and its complications in the community using hs troponin I. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noseworthy, P.A.; Kaufman, E.S.; Chen, L.Y.; Chung, M.K.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Joglar, J.A.; Leal, M.A.; McCabe, P.J.; Pokorney, S.D.; Yao, X.; et al. Subclinical and Device-Detected Atrial Fibrillation: Pondering the Knowledge Gap: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 140, e944–e963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, T.; Li, J.; Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Shen, C.; Gu, D.; Lu, X.; Liu, F. Association between NT-proBNP levels and risk of atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Heart 2025, 111, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugnicourt, J.M.; Rogez, V.; Guillaumont, M.P.; Rogez, J.C.; Canaple, S.; Godefroy, O. Troponin levels help predict new-onset atrial fibrillation in ischaemic stroke patients: A retrospective study. Eur. Neurol. 2010, 63, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, M.; Tascanov, M.B. Clinical value of the combined use of P-wave dispersion and troponin values to predict atrial fibrillation recurrence in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2021, 40, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Boriani, G.; Lip, G.Y.H. Are atrial high rate episodes (AHREs) a precursor to atrial fibrillation? Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Geng, J.; Ni, S.; Li, Q. Pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and genetics of atrial fibrillation. Hum. Cell 2024, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, I.; Layton, G.R.; Nizam, A.; Barker, J.; Abdelrazik, A.; Eldesouky, M.; Koya, A.; Lau, E.Y.M.; Zakkar, M.; Somani, R.; et al. Hypertension and Atrial Fibrillation: Bridging the Gap Between Mechanisms, Risk, and Therapy. Medicina 2025, 61, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniari, I.; Bozika, M.; Nastouli, K.M.; Tzegka, D.; Apostolos, A.; Velissaris, D.; Leventopoulos, G.; Perperis, A.; Kounis, N.G.; Tsigkas, G.; et al. The Role of Early Risk Factor Modification and Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation Substrate Remodeling Prevention. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P.; Alahmadi, M.H.; Ahmed, A.A. Left Atrial Enlargement. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.F.; Hu, J.; Fu, H.X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, P.P.; Yu, Y.C.; Wang, Q.S.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.G. The risk factors of atrial substrate remodeling in the patients of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation following pulmonary vein isolation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, R.; Abu Jaber, B.; Alzuqaili, T.; Ghura, S.; Al-Ajlouny, T.; Saadeh, A.M. The relationship of atrial fibrillation with left atrial size in patients with essential hypertension. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestrea, C.; Cicala, E.; Enache, R.; Rusu, M.; Gavrilescu, R.; Vaduva, A.; Risca, S.; Clapon, D.; Ortan, F. Mid-term comparison of new-onset AHRE between His bundle and left bundle branch area pacing in patients with AV block. J. Arrhythm. 2025, 41, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, B.; Fang, C.; Wang, P.; Tan, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, G.; Zheng, S.; Zhou, S. Study on the relationship between atrial high-rate episode and left atrial strain in patients with cardiac implantable electronic device. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 1844–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nguyen, S.K.; Kieu, D.N.; Tran, P.L.U.; Nguyen, C.K.T.; Dang, T.Q.; Van Ly, C.; Van Hoang, S.; Nguyen, T.T. The incidence and risk factors of atrial high-rate episodes in patients with a dual-chamber pacemaker. J. Arrhythm. 2024, 40, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, J.; Batta, A.; Barwad, P.; Sharma, Y.P.; Panda, P.; Kaur, N.; Shrimanth, Y.S.; Pruthvi, C.R.; Sambyal, B. Incidence of atrial high rate episodes after dual-chamber permanent pacemaker implantation and its clinical predictors. Indian. Heart J. 2022, 74, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, M.; Dejene, K.; Bedru, M.; Ahmed, M.; Markos, S. Predictors of complications and mortality among patients undergoing pacemaker implantation in resource-limited settings: A 10-year retrospective follow-up study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, S.; Nasir, M.; Ahmed, M.; Abebe, S.; Amogne, M.A.; Tesfaye, D.; Mekonnen, T.S.; Getachew, Y.G. Assessment of Trend, Indication, Complications, and Outcomes of Pacemaker Implantation in Adult Patients at Tertiary Hospital of Ethiopia: Retrospective Follow Up Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbi, M.; Verdaguer, J.; Itier, R.; Barde, L.; Fournier, P.; Grunenwald, E.; Gaudard, P.; Rouviere, P.; Molina, A.; Ughetto, A.; et al. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP monitoring in patients with left ventricular assist devices. JHLT Open 2025, 10, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bian, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Song, C.; Yuan, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Gao, J.; Cui, X.; et al. Clinical implication of NT-proBNP to predict mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.C.; Ciobanu, M.; Tint, D.; Nechita, A.C. Linking Heart Function to Prognosis: The Role of a Novel Echocardiographic Index and NT-proBNP in Acute Heart Failure. Medicina 2025, 61, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianos, R.D.; Iancu, M.; Pop, C.; Lucaciu, R.L.; Hangan, A.C.; Rahaian, R.; Cozma, A.; Negrean, V.; Mercea, D.; Procopciuc, L.M. Predictive Value of NT-proBNP, FGF21, Galectin-3 and Copeptin in Advanced Heart Failure in Patients with Preserved and Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina 2024, 60, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value (n = 232) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 63.7 ± 14.0 |

| Male Sex, n (%) | 124 (53.4%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 22.5 ± 3.3 |

| Clinical History and Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 137 (59.0%) |

| Heart Failure, n (%) | 42 (18.0%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 51 (22.0%) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 94 (40.5%) |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), n (%) | 36 (15.6%) |

| Prior Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 12 (5.2%) |

| Pacing Indication | |

| Sick Sinus Syndrome, n (%) | 77 (33.1%) |

| Atrioventricular Block, n (%) | 81 (34.9%) |

| Medications at Baseline | |

| ACE Inhibitors/ARBs, n (%) | 58 (25.1%) |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 18 (7.8%) |

| Statins, n (%) | 94 (40.7%) |

| Antiplatelets, n (%) | 66 (28.6%) |

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and Demographic Variables | |||

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.42 | 1.10–1.83 | 0.007 |

| Male Sex (vs. Female) | 1.05 | 0.72–1.54 | 0.810 |

| Hypertension (Yes vs. No) | 1.65 | 1.08–2.51 | 0.020 |

| Heart Failure (Yes vs. No) | 1.78 | 1.15–2.76 | 0.010 |

| Coronary Artery Disease (Yes vs. No) | 1.24 | 0.82–1.89 | 0.310 |

| Pacing Indication | |||

| Sick Sinus Syndrome (vs. AV Block) | 2.10 | 1.35–3.26 | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic | |||

| Left Atrial Diameter (per 1 mm increase) | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 | 0.006 |

| LVEF (per 5% increase) | 0.98 | 0.89–1.08 | 0.650 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE Inhibitors/ARBs (Yes vs. No) | 0.92 | 0.64–1.33 | 0.670 |

| Beta-blockers (Yes vs. No) | 1.12 | 0.70–1.78 | 0.635 |

| Biomarkers | |||

| hs-cTnI (per log-unit increase) | 1.03 | 0.85–1.25 | 0.780 |

| NT-proBNP (per log-unit increase) | 1.07 | 0.90–1.28 | 0.430 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duong, L.H.K.; Lam, N.V.; Tran, V.T. The Role of High-Sensitivity Troponin I in Predicting Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHREs) in Patients with Permanent Pacemakers. Life 2025, 15, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121850

Duong LHK, Lam NV, Tran VT. The Role of High-Sensitivity Troponin I in Predicting Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHREs) in Patients with Permanent Pacemakers. Life. 2025; 15(12):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121850

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuong, Linh Ha Khanh, Nien Vinh Lam, and Vinh Thanh Tran. 2025. "The Role of High-Sensitivity Troponin I in Predicting Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHREs) in Patients with Permanent Pacemakers" Life 15, no. 12: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121850

APA StyleDuong, L. H. K., Lam, N. V., & Tran, V. T. (2025). The Role of High-Sensitivity Troponin I in Predicting Atrial High-Rate Episodes (AHREs) in Patients with Permanent Pacemakers. Life, 15(12), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121850