The Roles of PCSK9 in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical, Genetic, and Preclinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

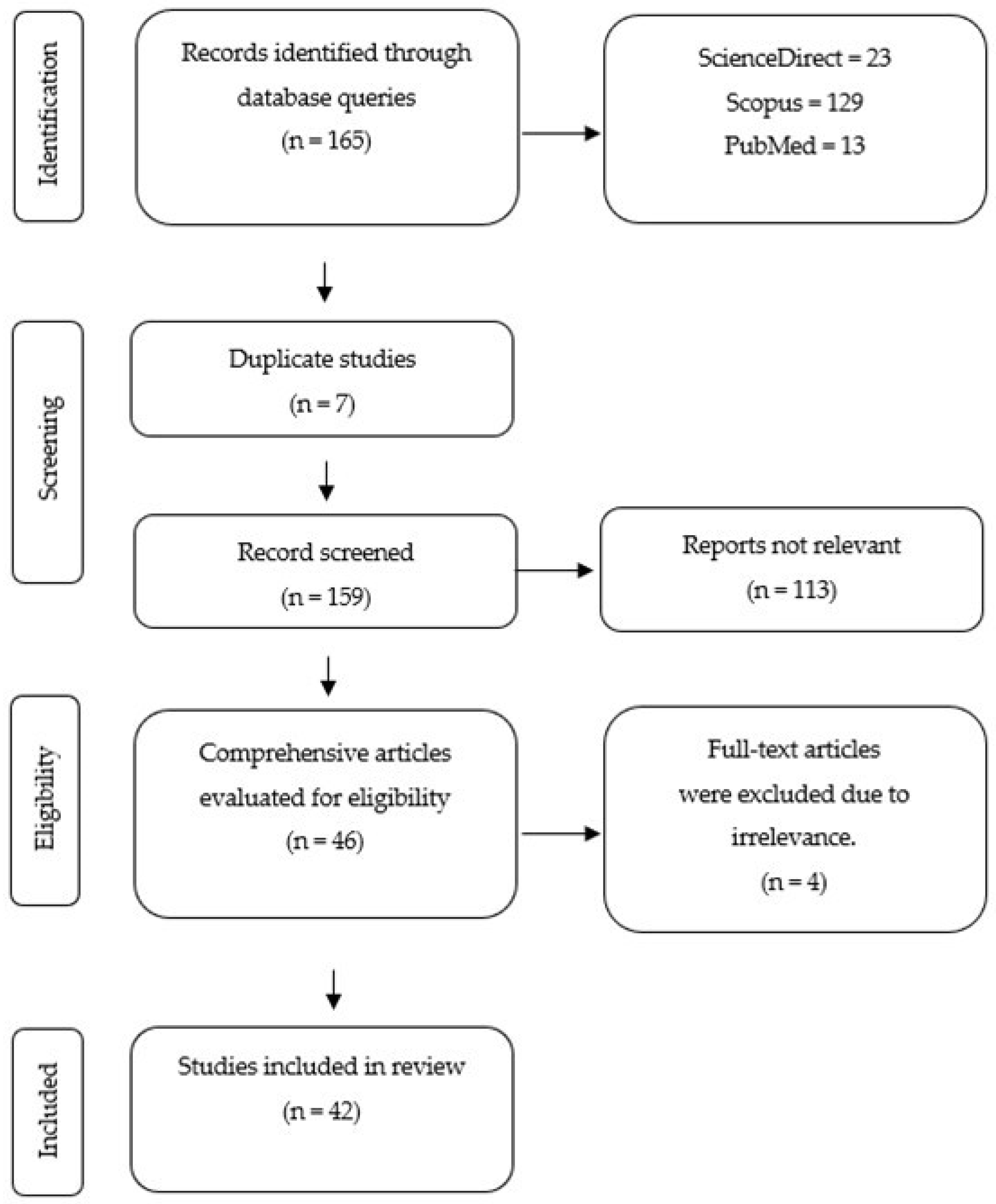

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Clinical Evidence

3.3. In Vivo Evidence

3.4. In Vitro Evidence

| Author (Year) | Population/Model | Intervention/Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bejaoui et al. (2025) [39] | 14,669 healthy individuals | DNA methylation & sequencing |

|

| Benn et al. (2017) [23] | >100,000 human cohorts (Denmark/UK) | Genetic proxies (MR |

|

| Caselii et al. (2019) [40] | 539 suspected CAD (EVINCI) | Plasma PCSK9 + coronary CTA |

|

| Courtemanche et al. (2018) [19] | 67 patients (36 AD, 31 controls) | CSF PCSK9, |

|

| Giugliano et al. (2017) [22] | 1204 ASCVD patients | Evolocumab vs. placebo (EBBINGHAUS RCT) |

|

| Harvey et al. (2018) [41] | Statin/PCSK9i users (multinational) | RCT meta-analysis | No increase in neurocognitive adverse events |

| Huang et al. (2024) [26] | 462,933 participants (China/UK Biobank) | Mendelian randomization |

|

| Korthauer et al. (2022) [42] | 868 elderly (65–83y, Germany) | Cognitive tests + APOE genotyping | No association of APOE genotype, lipid-lowering, cognition |

| Lambert et al. (2013) [25] | 74,046 individuals (I-GAP) | GWAS meta-analysis | Identified 19 AD-associated loci beyond APOE |

| Lee et al. (2025) [43] | 117 BD-II patients + 41 controls | Plasma PCSK9 biomarkers |

|

| Lütjohann et al. (2021) [44] | 28 hypercholesterolemic patients | Alirocumab/evolocumab |

|

| Paquette et al. (2018) [20] | 878 (468 AD cases, 410 ctrls, Canada) | PCSK9 LOF genotyping | No association with AD risk or cognition |

| Picard et al. (2019) [15] | AD brains + controls + at-risk individuals | Protein/mRNA/eQTL |

|

| Postmus et al. (2013) [45] | 5777 elderly (PROSPER) | PCSK9 SNP rs11591147 |

|

| Robinson et al. (2015) [10] | 2341 high-risk patients (ODYSSEY) | Alirocumab vs. placebo |

|

| Rosoff et al. (2022) [46] | ~740,000 European ancestry | MR study |

|

| Sabatine et al. (2017) [11] | 27,564 ASCVD (FOURIER) | Evolocumab vs. placebo |

|

| Seijas-Amigo et al. (2023) [47] | 158 ASCVD/familial hyperchol. (Spain) | Alirocumab/evolocumab (24mo MEMOGAL) | No cognitive impairment; small memory improvement |

| Shahid et al. (2022) [48] | Systematic review (20 trials) | Statins vs. PCSK9 inhibitors |

|

| Simeone et al. (2021) [27] | 166 high CV-risk (Italy) | Plasma PCSK9 + cognitive tests |

|

| Xu et al. (2014) [49] | 281 CAD patients (China) | Plasma PCSK9 + lipoprotein subfractions |

|

| Zimetti et al. (2016) [24] | 30 AD vs. 30 controls (Italy) | CSF PCSK9 + ApoE |

|

| Author (Year) | Population/Model | Intervention | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abuelezz et al. (2021) [34] | Wistar rats + HFCD | Alirocumab vs. memantin |

|

| Apaijai et al. (2019) [50] | 52 Wistar rats (cardiac I/R model) | PCSK9 inhibitor (10 µg/kg IV) |

|

| Arunsak et al. (2020) [35] | Sprague-Dawley rats + HFD | PCSK9 inhibitor vs. atorvastatin |

|

| Dong et al. (2023) [51] | APP/PS1 mice + rat neurons | Resveratrol, suramin, siRNA |

|

| Grames et al. (2018) [21] | APP/PS1 mice | AV8-PCSK9 gene transfer |

|

| Hernandez Torres et al. (2024) [31] | PCSK9DY mice (C57BL/6N) | AAV-PCSK9DY + Western diet |

|

| Kysenius et al. (2012) [52] | Mouse neurons (CGN & DRG) | PCSK9 RNAi knockdown |

|

| Liu et al. (2010) [32] | WT, KO & TG mice | Genetic manipulation |

|

| Mazura et al. (2022) [18] | 5xFAD mice + BBB cells | PCSK9, anti-PCSK9 mAbs |

|

| Shabir et al. (2022) [53] | PCSK9-ATH & J20-AD mice | AAV-PCSK9-induced atherosclerosis |

|

| Viella et al. (2024) [33] | 5xFAD mice + astrocytes | PCSK9 knockout + Aβ exposure |

|

| Wagner et al. (2024) [36] | Rats, chronic ethanol | Alirocumab |

|

| Yang et al. (2024) [54] | Streptozotocin-induced T2DM rats | PCSK9 inhibitor |

|

| Zhao et al. (2017) [55] | ApoE(−/−) mice + HFD | Diet-induced hyperlipidemia |

|

| Author (Year) | Population/Model | Intervention | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeVay et al. (2013) [56] | Human hepatocyte-derived cells (HepG2, Huh7, HEK293) | PCSK9, antibodies, siRNA |

|

| Fu et al. (2017) [57] | CHO cells, mouse neurons | siRNA, overexpression | PCSK9 interacts with APP/APLP2/LRP1, not essential for degradation |

| Kysenius et al. (2016) [38] | Primary cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) | Primary cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) |

|

| Papotti et al. (2022) [37] | Astrocytes & neurons (U373 + Aβ fibrils) | PCSK9 treatment |

|

| Rousselete et al. (2011) [16] | Mouse primary neurons | PCSK9 overexpression/knockdown | PCSK9 ↓ LDLR, impaired cholesterol uptake |

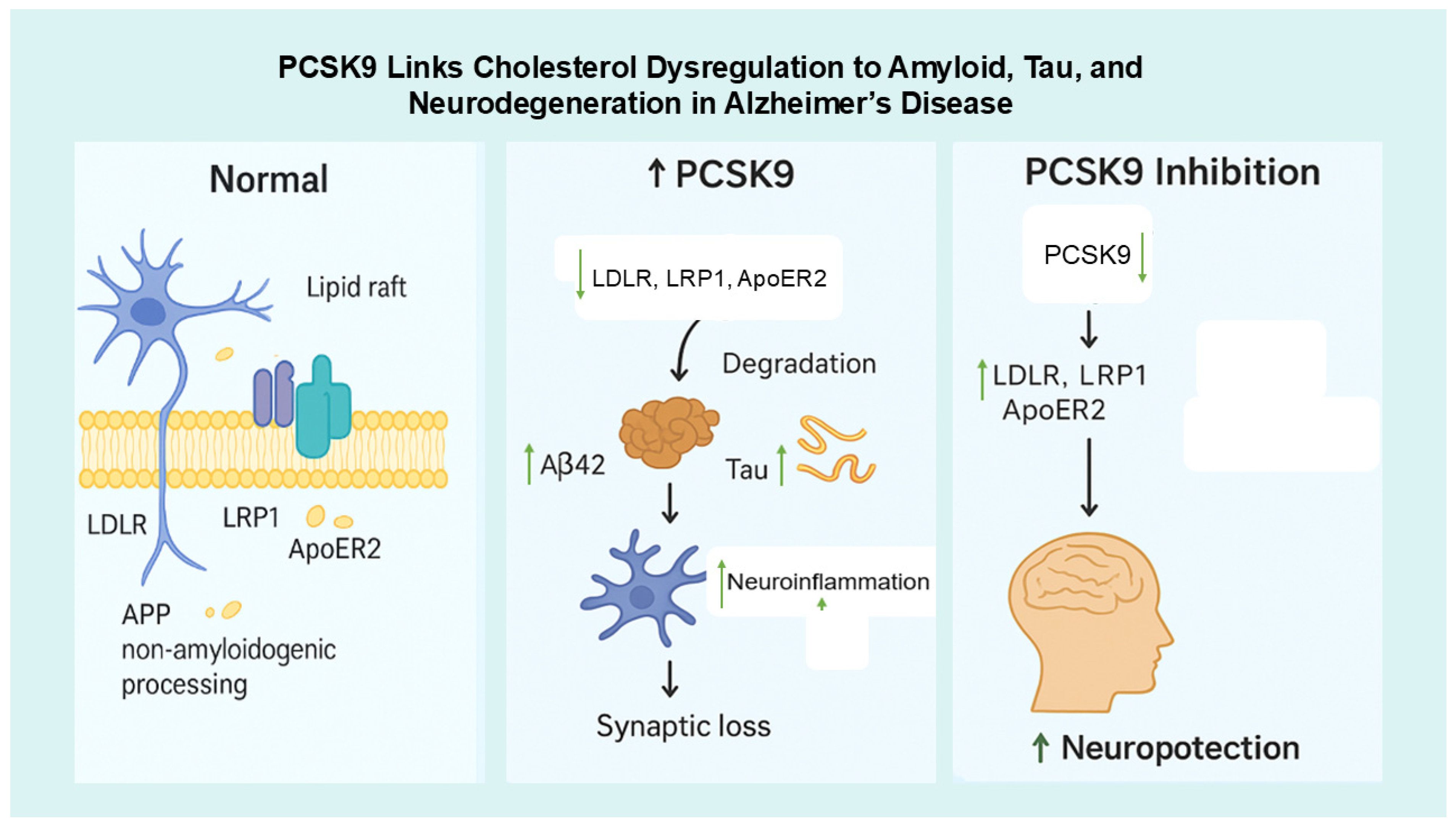

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Studies

4.2. In Vivo Studies

4.3. In Vitro Studies

4.4. Integrative Studies

4.5. Future Priorities

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Paolo, G.; Kim, T.W. Linking lipids to Alzheimer’s disease: Cholesterol and beyond. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.K.; Moquin-Beaudry, G.; Mangahas, C.L.; Pratesi, F.; Aubin, M.; Aumont, A.; Joppé, S.E.; Légiot, A.; Vachon, A.; Plourde, M.; et al. Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase inhibition reverses immune, synaptic and cognitive impairments in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz-Vazquez, O.; Puente-Martinez, A.; Ubillos-Landa, S.; Pacheco-Bonrostro, J.; Santabárbara, J. Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk: A Meta-Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, M.; Yin, X.; Chen, K.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, D. The role of pathological tau in synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2021, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, B.; Ba, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Su, K.; Qi, H.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Targeting dysregulated lipid metabolism for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: Current advancements and future prospects. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 196, 106505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Giannelli, S.; Staurenghi, E.; Cecci, R.; Floro, L.; Gamba, P.; Sottero, B.; Leonarduzzi, G. The Emerging Role of PCSK9 in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Possible Target for the Disease Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yuan, W.; Li, L.; Ma, H.; Zhu, M.; Li, X.; Feng, X. Targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) to tackle central nervous system diseases: Role as a promising approach. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Liang, Y.; Chang, H.; Cai, T.; Feng, B.; Gordon, K.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, H.; He, Y.; Xie, L. Targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): From bench to bedside. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S.T.; Rosenson, R.S.; Avery, C.L.; Chen, Y.D.I.; Correa, A.; Cummings, S.R.; Cupples, L.A.; Cushman, M.; Evans, D.S.; Gudnason, V.; et al. PCSK9 Loss-of-Function Variants, Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol, and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: Data from 9 Studies of Blacks and Whites. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e001632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.G.; Farnier, M.; Krempf, M.; Bergeron, J.; Luc, G.; Averna, M.; Stroes, E.S.; Langslet, G.; Raal, F.J.; El Shahawy, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Alirocumab in Reducing Lipids and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidah, N.G.; Benjannet, S.; Wickham, L.; Marcinkiewicz, J.; Jasmin, S.B.; Stifani, S.; Basak, A.; Prat, A.; Chrétien, M. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): Liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidah, N.G.; Awan, Z.; Chrétien, M.; Mbikay, M. PCSK9: A key modulator of cardiovascular health. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puteri, M.U.; Azmi, N.U.; Kato, M.; Saputri, F.C. PCSK9 Promotes Cardiovascular Diseases: Recent Evidence about Its Association with Platelet Activation-Induced Myocardial Infarction. Life 2022, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, C.; Poirier, A.; Bélanger, S.; Labonté, A.; Auld, D.; Poirier, J. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) in Alzheimer’s disease: A genetic and proteomic multi-cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousselet, E.; Marcinkiewicz, J.; Kriz, J.; Zhou, A.; Hatten, M.E.; Prat, A.; Seidah, N.G. PCSK9 reduces the protein levels of the LDL receptor in mouse brain during development and after ischemic stroke. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.S.; Wagner, J.; Rosoff, D.B.; Lohoff, F.W. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) in the central nervous system. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 149, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazura, A.D.; Ohler, A.; Storck, S.E.; Kurtyka, M.; Scharfenberg, F.; Weggen, S.; Becker-Pauly, C.; Pietrzik, C.U. PCSK9 acts as a key regulator of Aβ clearance across the blood–brain barrier. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtemanche, H.; Bigot, E.; Pichelin, M.; Guyomarch, B.; Boutoleau-Bretonnière, C.; Le May, C.; Derkinderen, P.; Cariou, B. PCSK9 Concentrations in Cerebrospinal Fluid Are Not Specifically Increased in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 62, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, M.; Saavedra, Y.G.L.; Poirier, J.; Théroux, L.; Dea, D.; Baass, A.; Dufour, R. Loss-of-Function PCSK9 Mutations Are Not Associated with Alzheimer Disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2018, 31, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grames, M.S.; Dayton, R.D.; Lu, X.; Schilke, R.M.; Steven Alexander, J.; Wayne Orr, A.; Barmada, S.J.; Woolard, M.D.; Klein, R.L. Gene Transfer Induced Hypercholesterolemia in Amyloid Mice. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 65, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.P.; Mach, F.; Zavitz, K.; Kurtz, C.; Im, K.; Kanevsky, E.; Schneider, J.; Wang, H.; Keech, A.; Pedersen, T.R.; et al. Cognitive Function in a Randomized Trial of Evolocumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benn, M.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Frikke-Schmidt, R.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A. Low LDL cholesterol, PCSK9 and HMGCR genetic variation, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 2017, 357, j1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimetti, F.; Caffarra, P.; Ronda, N.; Favari, E.; Adorni, M.P.; Zanotti, I.; Bernini, F.; Barocco, F.; Spallazzi, M.; Galimberti, D.; et al. Increased PCSK9 cerebrospinal fluid concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 55, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; DeStafano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, B. Causal relationship between PCSK9 inhibitor and common neurodegenerative diseases: A drug target Mendelian randomization study. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, P.G.; Vadin, F.; Tripald, R.; Lian, R.; Ciotti, S.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Cipollone, F.; Santilli, F. Sex-Specific Association of Endogenous PCSK9 With Memory Function in Elderly Subjects at High Cardiovascular Risk. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 632655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Butterworth, A.S.; Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: Principles and applications. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4913–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, T.; Miao, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Chang, E. The causal association between circulating metabolites and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. Metabolomics 2025, 21, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirkhah, A.; Schachtl-Riess, J.F.; Lamina, C.; Di Maio, S.; Koller, A.; Schönherr, S.; Coassin, S.; Forer, L.; Sekula, P.; Gieger, C.; et al. Meta-GWAS on PCSK9 concentrations reveals associations of novel loci outside the PCSK9 locus in White populations. Atherosclerosis 2023, 386, 117384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Torres, L.D.; Rezende, F.; Peschke, E.; Will, O.; Hövener, J.B.; Spiecker, F.; Özorhan, Ü.; Lampe, J.; Stölting, I.; Aherrahrou, Z.; et al. Incidence of microvascular dysfunction is increased in hyperlipidemic mice, reducing cerebral blood flow and impairing remote memory. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1338458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, G.; Baysarowich, J.; Kavana, M.; Addona, G.H.; Bierilo, K.K.; Mudgett, J.S.; Pavlovic, G.; Sitlani, A.; Renger, J.J.; et al. PCSK9 is not involved in the degradation of LDL receptors and BACE1 in the adult mouse brain. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2611–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella, A.; Bodria, M.; Papotti, B.; Zanotti, I.; Zimetti, F.; Remaggi, G.; Elviri, L.; Potì, F.; Ferri, N.; Lupo, M.G.; et al. PCSK9 ablation attenuates Aβ pathology, neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunctions in 5XFAD mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 115, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelezz, S.A.; Hendawy, N. HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 axis and glutamate as novel targets for PCSK9 inhibitor in high fat cholesterol diet induced cognitive impairment and amyloidosis. Life Sci. 2021, 273, 119310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunsak, B.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Amput, P.; Chattipakorn, K.; Tosukhowong, T.; Kerdphoo, S.; Jaiwongkum, T.; Thonusin, C.; Palee, S.; Chattipakorn, N.; et al. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor exerts greater efficacy than atorvastatin on improvement of brain function and cognition in obese rats. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 689, 108470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.; Park, L.M.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Matyas, C.; Trojnar, E.; Damadzic, R.; Jung, J.; Bell, A.S.; Mavromatis, L.A.; Hamandi, A.M.; et al. PCSK9 inhibition attenuates alcohol-associated neuronal oxidative stress and cellular injury. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 119, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papotti, B.; Adorni, M.P.; Marchi, C.; Zimetti, F.; Ronda, N.; Panighel, G.; Lupo, M.G.; Vilella, A.; Giuliani, D.; Ferri, N.; et al. PCSK9 Affects Astrocyte Cholesterol Metabolism and Reduces Neuron Cholesterol Supplying In Vitro: Potential Implications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysenius, K.; Huttunen, H.J. Stress-induced upregulation of VLDL receptor alters Wnt-signaling in neurons. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 340, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, Y.; Srour, L.; Qannan, A.; Oshima, J.; Saad, C.; Horvath, S.; Mbarek, H.; El Hajj, N. The role of protective genetic variants in modulating epigenetic aging. GeroScience 2025, 47, 5995–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, C.; Del Turco, S.; Ragusa, R.; Lorenzoni, V.; De Graaf, M.; Basta, G.; Scholte, A.; De Caterina, R.; Neglia, D. Association of PCSK9 plasma levels with metabolic patterns and coronary atherosclerosis in patients with stable angina. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.D.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Harrison, J.E.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Chapman, M.J.; Manvelian, G.; Moryusef, A.; Mandel, J.; Farnier, M. No evidence of neurocognitive adverse events associated with alirocumab treatment in 3340 patients from 14 randomized Phase 2 and 3 controlled trials: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthauer, L.E.; Giugliano, R.P.; Guo, J.; Sabatine, M.S.; Sever, P.; Keech, A.; Atar, D.; Kurtz, C.; Ruff, C.T.; Mach, F.; et al. No association between APOE genotype and lipid lowering with cognitive function in a randomized controlled trial of evolocumab. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Li, S.C.; Wang, T.Y.; Lu, R.B.; Wang, L.J.; Tsai, K.W. Protein biomarkers for bipolar II disorder are correlated with affective cognitive performance. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütjohann, D.; Stellaard, F.; Bölükbasi, B.; Kerksiek, A.; Parhofer, K.G.; Laufs, U. Anti-PCSK 9 antibodies increase the ratios of the brain-specific oxysterol 24S-hydroxycholesterol to cholesterol and to 27-hydroxycholesterol in the serum. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 4252–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmus, I.; Trompet, S.; De Craen, A.J.M.; Buckley, B.M.; Ford, I.; Stott, D.J.; Sattar, N.; Slagboom, P.E.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Jukema, J.W. PCSK9 SNP rs11591147 is associated with low cholesterol levels but not with cognitive performance or noncardiovascular clinical events in an elderly population. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosoff, D.B.; Bell, A.S.; Jung, J.; Wagner, J.; Mavromatis, L.A.; Lohoff, F.W. Mendelian Randomization Study of PCSK9 and HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibition and Cognitive Function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijas-Amigo, J.; Mauriz-Montero, M.A.J.; Suarez-Artime, P.; Gayoso-Rey, M.; Estany-Gestal, A.; Casas-Martínez, A.; González-Freire, L.; Rodriguez-Vazquez, A.; Pérez-Rodriguez, N.; Villaverde-Piñeiro, L.; et al. Cognitive Function with PCSK9 Inhibitors: A 24-Month Follow-Up Observational Prospective Study in the Real World—MEMOGAL Study. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2023, 23, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, R.; Naik, S.S.; Ramphall, S.; Rijal, S.; Prakash, V.; Ekladios, H.; Saju, J.M.; Mandal, N.; Kham, N.I.; Hamid, P. Neurocognitive Impairment in Cardiovascular Disease Patients Taking Statins Versus Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.L.; Guo, Y.L.; Zhu, C.G.; Li, J.J. Relation of plasma PCSK9 levels to lipoprotein subfractions in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaijai, N.; Moisescu, D.M.; Palee, S.; Mervyn McSweeney, C.; Saiyasit, N.; Maneechote, C.; Boonnag, C.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Pretreatment with PCSK9 inhibitor protects the brain against cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury through a reduction of neuronal inflammation and amyloid beta aggregation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e010838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.T.; Cao, K.; Xiang, J.; Qi, X.L.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, W.F.; He, Y.; Hong, W.; Guan, Z.Z. Resveratrol Attenuates the Disruption of Lipid Metabolism Observed in Amyloid Precursor Protein/Presenilin 1 Mouse Brains and Cultured Primary Neurons Exposed to Aβ. Neuroscience 2023, 521, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysenius, K.; Muggalla, P.; Mätlik, K.; Arumäe, U.; Huttunen, H.J. PCSK9 regulates neuronal apoptosis by adjusting ApoER2 levels and signaling. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabir, O.; Pendry, B.; Lee, L.; Eyre, B.; Sharp, P.S.; Rebollar, M.A.; Drew, D.; Howarth, C.; Heath, P.R.; Wharton, S.B.; et al. Assessment of neurovascular coupling and cortical spreading depression in mixed mouse models of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. eLife 2022, 11, e68242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, T.; Zhao, L. PCSK9 inhibitor effectively alleviated cognitive dysfunction in a type 2 diabetes mellitus rat model. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.S.; Wu, Q.; Peng, J.; Pan, L.H.; Ren, Z.; Liu, H.T.; Jiang, Z.S.; Wang, G.X.; Tang, Z.H.; Liu, L.S. Hyperlipidemia-induced apoptosis of hippocampal neurons in apoE(−/−) mice may be associated with increased PCSK9 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVay, R.M.; Shelton, D.L.; Liang, H. Characterization of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) trafficking reveals a novel lysosomal targeting mechanism via amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2). J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10805–10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Guan, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y. APP, APLP2 and LRP1 interact with PCSK9 but are not required for PCSK9-mediated degradation of the LDLR in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1862, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, S.; Prat, A.; Marcinkiewicz, E.; Paquin, J.; Chitramuthu, B.P.; Baranowski, D.; Cadieux, B.; Bennett, H.P.J.; Seidah, N.G. Implication of the proprotein convertase NARC-1/PCSK9 in the development of the nervous system. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiciński, M.; Żak, J.; Malinowski, B.; Popek, G.; Grześk, G. PCSK9 signaling pathways and their potential importance in clinical practice. EPMA J. 2017, 8, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, A.K.; Techer, R.; Chemello, K.; Lambert, G.; Bourane, S. PCSK9 and the nervous system: A no-brainer? J. Lipid Res. 2023, 64, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, E.M.; Lohoff, F.W. Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) in the Brain and Relevance for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorni, M.P.; Ruscica, M.; Ferri, N.; Bernini, F.; Zimetti, F. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, brain cholesterol homeostasis and potential implication for Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Tang, Z.H.; Peng, J.; Liao, L.; Pan, L.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Jiang, Z.S.; Wang, G.X.; Liu, L.S. The dual behavior of PCSK9 in the regulation of apoptosis is crucial in Alzheimer’s disease progression (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2014, 2, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Mazidi, M.; Davies, I.G.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Seidah, N.; Libby, P.; Kroemer, G.; Ren, J. PCSK9 in metabolism and diseases. Metabolism 2025, 163, 156064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.D.; Peng, Z.S.; Gu, H.M.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.Q.; Zhang, D.W. Regulation of PCSK9 Expression and Function: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 764038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, X.H.; Liu, H.J.; Xu, Q. Evaluating the potential effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on the risk of sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmias: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.Q.T.; Tran, N.B.; Nguyen, N.; Downes, D.; Arrighini, G.S.; Dandamudi, M.; Cardoso, R.; Giorgi, J. Oral PCSK9 Inhibitors as an Emerging Frontier in Lipid Management: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 12, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, M.; Peterson, K.; Holzhammer, B.; Fazio, S. A systematic review of PCSK9 inhibitors alirocumab and evolocumab. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2016, 22, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeter, W.C.; Carter, N.M.; Nadler, J.L.; Galkina, E.V. The AAV-PCSK9 murine model of atherosclerosis and metabolic dysfunction. Eur. Heart J. Open 2022, 2, oeac028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.J.; Xu, Y.T.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z.H.; Little, P.J.; Wang, L.; Xian, X.D.; Weng, J.P.; Xu, S.W. A novel mouse model of familial combined hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Niu, D.; Sun, Y.; Chai, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Dong, J. PCSK9 inhibitors suppress oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerotic development by promoting macrophage autophagy. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 5129–5144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ugolotti, M.; Papotti, B.; Adorni, M.P.; Giannessi, L.; Rossi, I.; Lupo, M.G.; Panighel, G.; Ferri, N.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Vilella, A.; et al. Effect of natural and synthetic PCSK9 inhibitors on Alzheimer’s disease-related parameters in human cerebral cell models. Atherosclerosis 2024, 395, 118365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frostegård, J. The role of PCSK9 in inflammation, immunity, and autoimmune diseases. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejabat, M.; Hadizadeh, F.; Almahmeed, W.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of PCSK9 inhibitors on cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2025, 30, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Brickell, A.N.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Ding, Z. NADPH oxidase promotes PCSK9 secretion in macrophages. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 153, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkapli, R.; Muid, S.A.; Wang, S.M.; Nawawi, H. PCSK9 Inhibitors Reduce PCSK9 and Early Atherogenic Biomarkers in Stimulated Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, P.; Sharma, V.; Sagar, R.; Thapliyal, S. Role of PCSK9 in Alzheimer’s Disease by Modulating Brain Cholesterol Homeostasis: An Overview. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2025, 13, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.L.; Trankle, C.; Buckley, L.; Parod, E.; Carbone, S.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Abbate, A. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2016, 10, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Fan, D.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Jiang, H.; Wang, L. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential of PCSK9-regulating drugs. Pharm. Biol. 2025, 63, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suswidiantoro, V.; Puteri, M.U.; Kato, M.; Ariestanti, D.M.; James, R.J.; Saputri, F.C. The Roles of PCSK9 in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical, Genetic, and Preclinical Evidence. Life 2025, 15, 1851. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121851

Suswidiantoro V, Puteri MU, Kato M, Ariestanti DM, James RJ, Saputri FC. The Roles of PCSK9 in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical, Genetic, and Preclinical Evidence. Life. 2025; 15(12):1851. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121851

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuswidiantoro, Vicko, Meidi Utami Puteri, Mitsuyasu Kato, Donna Maretta Ariestanti, Richard Johari James, and Fadlina Chany Saputri. 2025. "The Roles of PCSK9 in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical, Genetic, and Preclinical Evidence" Life 15, no. 12: 1851. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121851

APA StyleSuswidiantoro, V., Puteri, M. U., Kato, M., Ariestanti, D. M., James, R. J., & Saputri, F. C. (2025). The Roles of PCSK9 in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical, Genetic, and Preclinical Evidence. Life, 15(12), 1851. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121851