Model of Threats to Computer Network Software

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To analyze the current state of the subject area: computer network models and approaches to building threat models used in compiling lists of threats.

- To develop a computer network model that allows to describe the structure of the system at a level of detail enough to compile a list of threats.

- To develop a computer network threat model that takes into account the maximum possible number of threats.

2. Related Work

- Some threat models contain elements of the attacker model, or the attacker model directly influences the formation of the list of threats.

- In one threat model at one level there may be a generalized description of threats, as well as a description of special cases.

- There is no division into threats aimed at the system and threats aimed at the information.

- The building of threat lists is based on the subjective opinion of an information security specialist.

- The hierarchy of computer network software.

- The possibility of the existence of several connections between two elements.

- The elements and the connections between them have parameters.

3. Proposed Approach

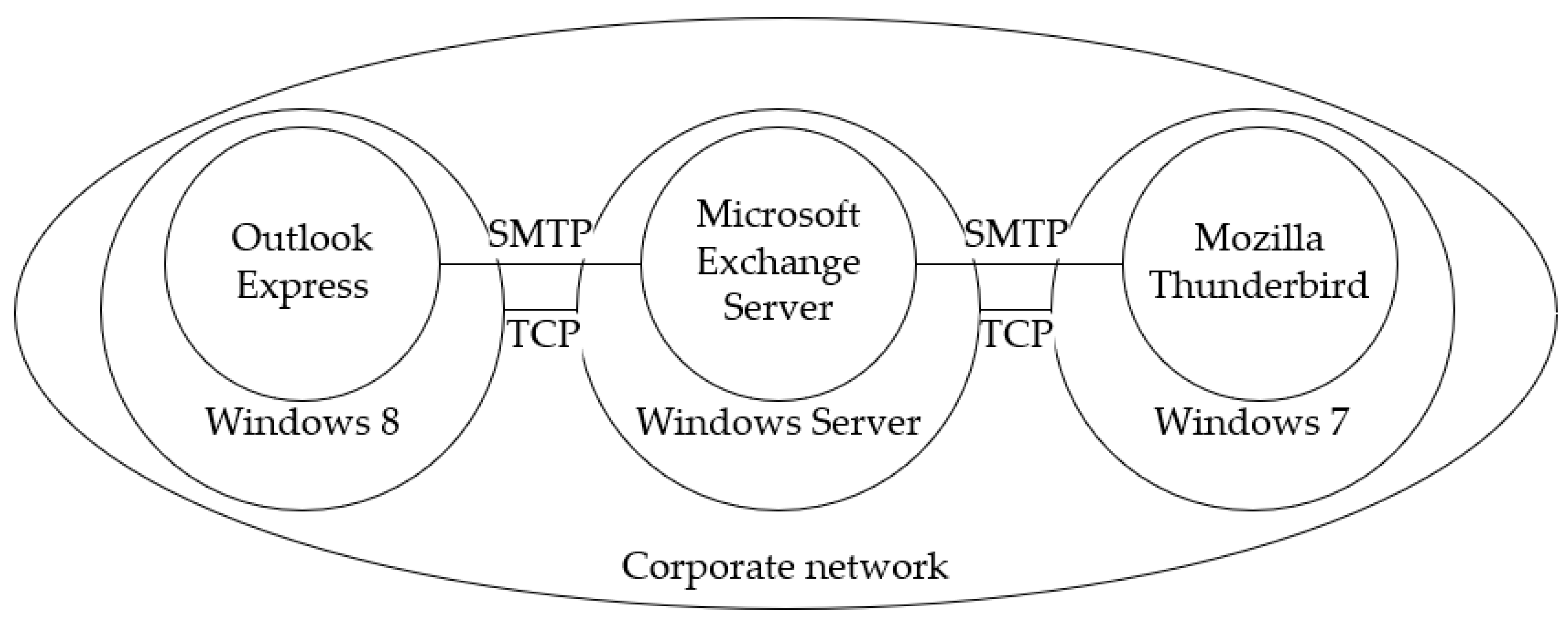

3.1. Computer Network Model

- , is a set of applications;

- , is a set of operating systems;

- , is a set of networks;

- , is a set of links between applications, defined over a set ;

- , is a set of links between operating systems, defined over a set ;

- , is a set of links between networks, defined over a set .

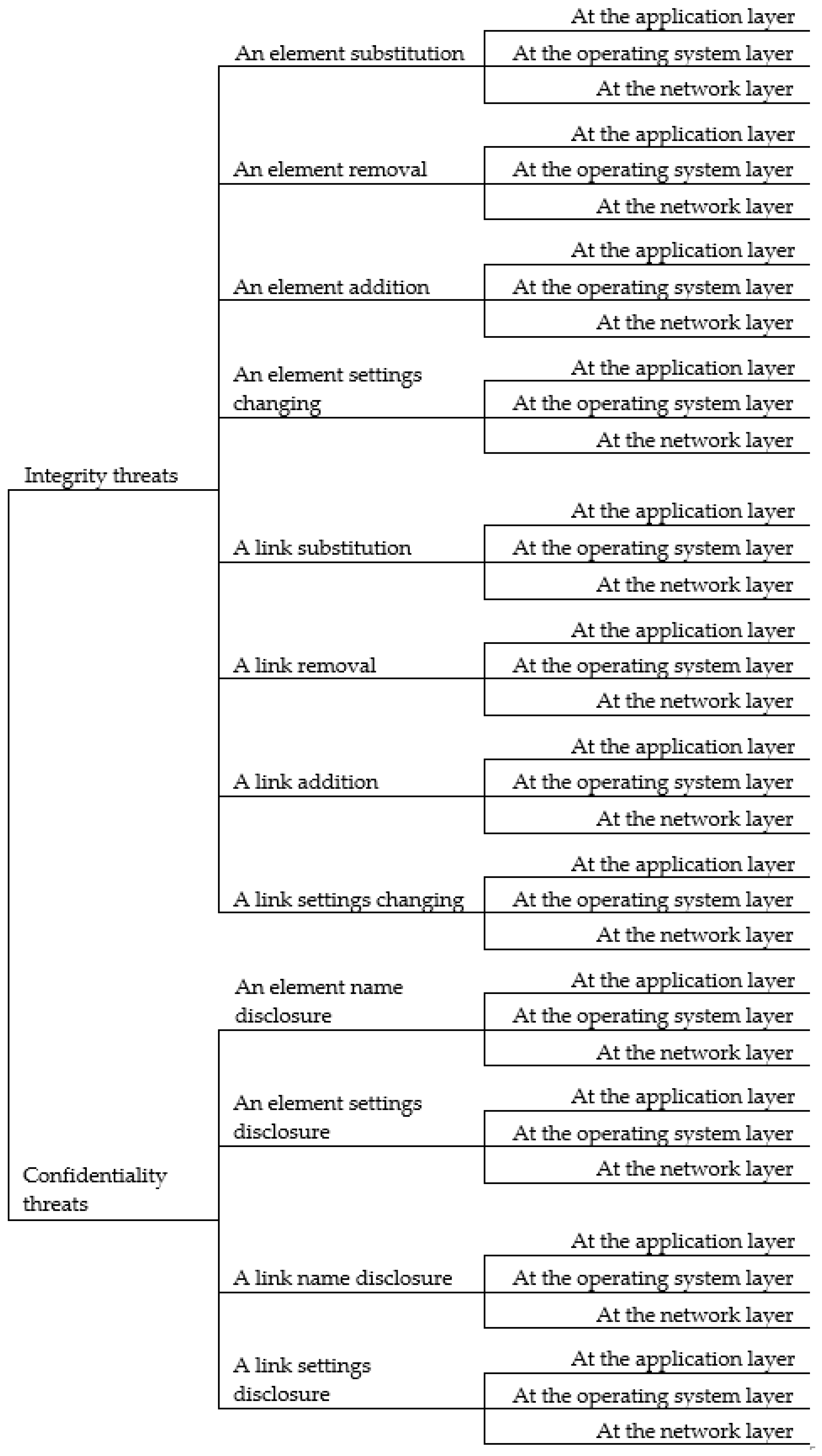

3.2. Model of Threats

- Threats of an element substitution—

- Threats of a link substitution—

- Threats of an element removal—

- Threats of a link removal—

- Threats of an element addition—

- Threats of a link addition—

- Threats of an element settings changing—

- Threats of a link settings changing—

- Threats of an element name disclosure—

- Threats of a link name disclosure—

- Threats of an element settings disclosure—

- Threats of a link settings disclosure—

4. Discussion

- Network layer: the availability of equipment is isolated, network traffic is intercepted, network traffic is modified.

- OS layer: malicious software is installed, the stability of system processes and services is violated, information resources are impacted.

- Application layer: applications are disabled, information resources of applications are impacted, the operations of applications are modified.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Penetration Testing of Corporate Information Systems: Statistics and Findings, 2019. Available online: https://www.ptsecurity.com/ww-en/analytics/corp-vulnerabilities-2019 (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Internet Security Threat Report (ISTR) 2019. Symantec. Available online: https://www.symantec.com/security-center/threat-report (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Meneghello, F.; Calore, M.; Zucchetto, D.; Polese, M.; Zanella, A. IoT: Internet of Threats? A Survey of Practical Security Vulnerabilities in Real IoT Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8182–8201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, H.A.; Nijdam, N.A.; Collen, A.; Konstantas, D. A Study on Security and Privacy Guidelines, Countermeasures, Threats: IoT Data at Rest Perspective. Symmetry 2019, 11, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelupanov, A.; Konev, A.; Kosachenko, T.; Dudkin, D. Threat model for IoT systems on the example of openUNB protocol. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Eng. Res. 2019, 7, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.; Barhamgi, M.; Bandara, A.; Ajmal, M.; Price, B.; Nuseibeh, B. Designing privacy-aware internet of things applications. Inf. Sci. 2019, 512, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konev, A.A. Approach to creation protected information model. Proc. TUSUR Univ. 2012, 25, 34–39. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zahoor, A.S.; Mahmood, H.S.; Javed, A. Information security management needs more holistic approach: A literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelupanov, A.; Evsyutin, O.; Konev, A.; Kostyuchenko, E.; Kruchinin, D.; Nikiforov, D. Information Security Methods—Modern Research Directions. Symmetry 2019, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shostack, A. Threat Modeling: Designing for Security; John Wiley & Sons: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2014; pp. 59–121. [Google Scholar]

- The STRIDE Threat Model. Available online: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/commerce-server/ee823878(v=cs.20) (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Jouini, M.; Rabai, L. Threat classification: State of art. In Handbook of Research on Modern Cryptographic Solutions for Computer and Cyber Security; Gupta, B., Agrawal, D., Yamaguchi, S., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 368–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wenjun, X.; Lagerström, R. Threat modeling—A systematic literature review. Comput. Secur. 2019, 84, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, D.; Ming, L.; Li, X. A Scalable Architecture for Classifying Network Security Threats. Available online: http://papersub.academicpub.org/Global/DownloadService.aspx?ID=2514 (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Pan, J.; Zhuang, Y. PMCAP: A Threat Model of Process Memory Data on the Windows Operating System. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Maglaras, L.A.; Janicke, H.; Jiang, J.; Shu, L. Authentication Protocols for Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Survey. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, T. A Clustering K-Anonymity Privacy-Preserving Method for Wearable IoT Devices. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.D.; Palomar, E.; Mahbub, K.; Abdallah, A.E. Relevance Filtering for Shared Cyber Threat Intelligence (Short Paper). In Information Security Practice and Experience; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhno, V. Creation of the adaptive cyber threat detection system on the basis of fuzzy feature clustering. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2016, 2, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodeau, D.J.; McCollum, C.D. System-of-Systems Threat Model; The Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute (HSSEDI) MITRE: Bedford, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Darwisha, S.; Nouretdinova, I.; Wolthusen, S.D. Towards Composable Threat Assessment for Medical IoT (MIoT). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 113, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wei, Q. Quantitative Analysis of the Security of Software-Defined Network Controller Using Threat/Effort Model. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.; Bag, S.; Perera, C.; Barhamgi, M.; Hao, F. Authentic-Caller: Self-enforcing Authentication in a Next Generation Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouini, M.; Rabai, L.; Aissa, A.B. Classification of Security Threats in Information Systems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 32, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhebaishi, N.; Wang, L.; Jajodia, S.; Singhal, A. Threat Modeling for Cloud Data Center Infrastructures. In International Symposium on Foundations and Practice of Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 302–319. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.; Vernotte, A.; Ekstedt, M.; Lagerström, R. pwnPr3d: An Attack-Graph-Driven Probabilistic Threat-Modeling Approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES), Salzburg, Austria, 31 August–2 September 2016; pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhtouta, A.; Mouheb, D.; Debbabi, M.; Alfandi, O.; Iqbal, F.; El Barachi, M. Graph-theoretic characterization of cyber-threat infrastructures. Digit. Investig. 2015, 14, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luh, R.; Temper, M.; Tjoa, S.; Schrittwieser, S. APT RPG: Design of a Gamified Attacker/Defender Meta Model. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2018), Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 526–537. [Google Scholar]

- MITRE ATT&CK Matrix. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Information Security Threat Databank. Available online: https://bdu.fstec.ru/threat (accessed on 29 October 2019). (In Russian).

- Bernard, G. Interconnection of Local Computer Networks: Modeling and Optimization Problems. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1983, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudin, E.B.; Smetanin, Y.G. Problems and prospects of modeling computer information networks. A review. Autom. Doc. Math. Linguist. 2010, 44, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Y.E.; Myr, A.E.; Omari, L. Deterministic and Stochastic Study for an Infected Computer Network Model Powered by a System of Antivirus Programs. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchurov, A.A. A Multilayer Model of Computer Networks. Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol. 2015, 26, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchurov, A.A.; Marik, R. A Trusted Model of Complex Computer Networks. J. ICT Stand. 2016, 3, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrova, D.S.; Pechenkin, A.I. Adaptive reflexivity threat protection. Autom. Control Comput. Sci. 2015, 49, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Blanning, R.W. Metagraphs and Their Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novokhrestov, A.; Konev, A. Mathematical model of threats to information systems. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1772, 060015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novokhrestov, A.K.; Nikiforov, D.S.; Konev, A.A.; Shelupanov, A.A. Model of threats to automatic system for commercial accounting of power consumption. Proc. TUSUR Univ. 2016, 19, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Attributes |

|---|---|

| Element of set (applications) | Application name Application version Number of the port used by the application |

| Element of set (operating systems) | OS name OS version IP-address used by the OS |

| Element of set (networks) | Network name Protocols in the network (OSI model network layer) Routing table IP-address and network mask |

| Element of set (links between applications) | OSI model application layer (session, presentation) |

| Element of set (links between operating systems) | Protocols of the OSI model transport layer |

| Element of set (links between networks) | Protocols of the OSI model network layer |

| Threat Classes | Computer Network Software Layers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Application | OS | Network | |

| + | + | ||

| + | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| Threat Classes | Computer Network Software Layers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Application | OS | Network | |

| + | |||

| + | + | ||

| + | + | + | |

| + | + | ||

| + | + | + | |

| + | |||

| + | + | + | |

| + | |||

| + | + | ||

| + | + | ||

| + | + | + | |

| + | + | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novokhrestov, A.; Konev, A.; Shelupanov, A. Model of Threats to Computer Network Software. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11121506

Novokhrestov A, Konev A, Shelupanov A. Model of Threats to Computer Network Software. Symmetry. 2019; 11(12):1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11121506

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovokhrestov, Aleksey, Anton Konev, and Alexander Shelupanov. 2019. "Model of Threats to Computer Network Software" Symmetry 11, no. 12: 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11121506

APA StyleNovokhrestov, A., Konev, A., & Shelupanov, A. (2019). Model of Threats to Computer Network Software. Symmetry, 11(12), 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11121506