Reversible Steganographic Scheme for AMBTC-Compressed Image Based on (7,4) Hamming Code

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

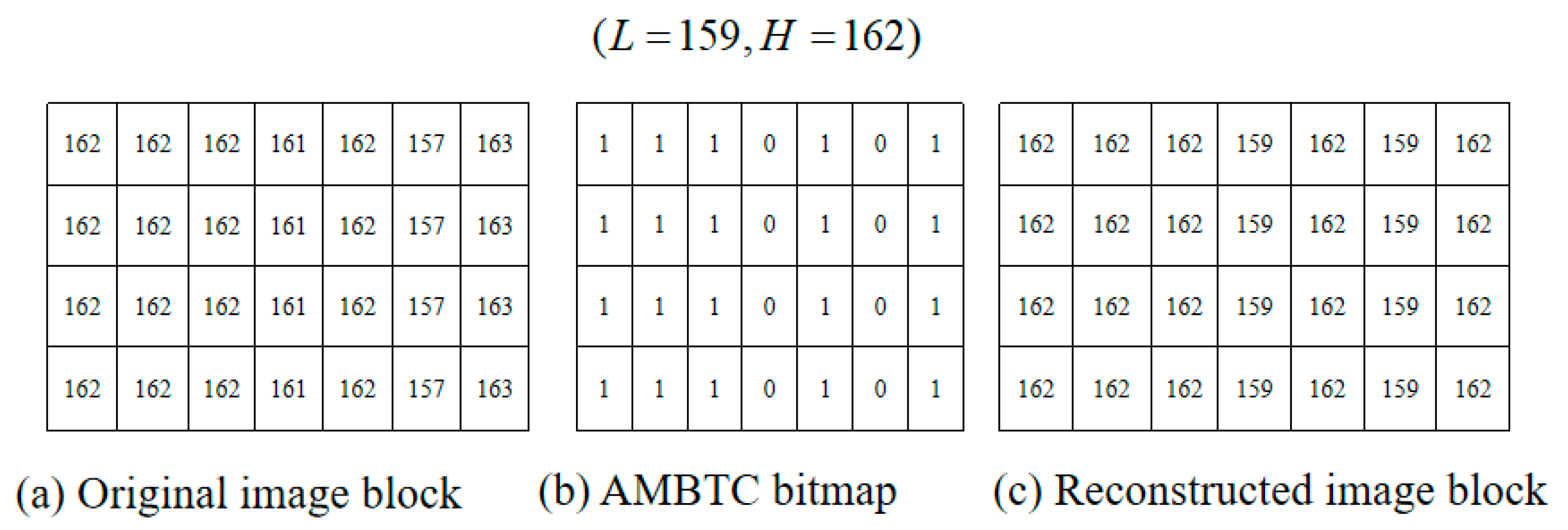

2.1. Absolute Moment Block Truncation Coding (AMBTC)

2.2. (7,4) Hamming Code

3. Proposed Scheme

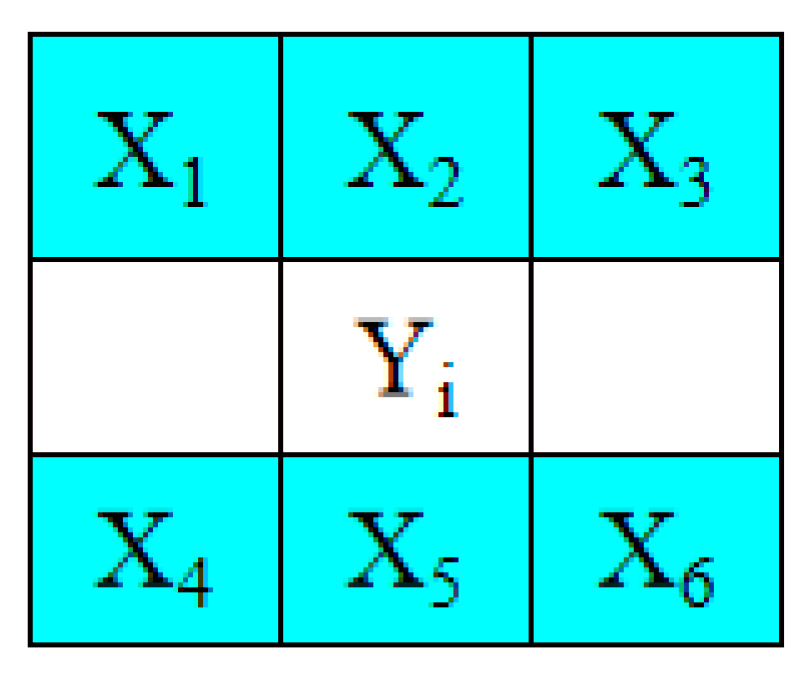

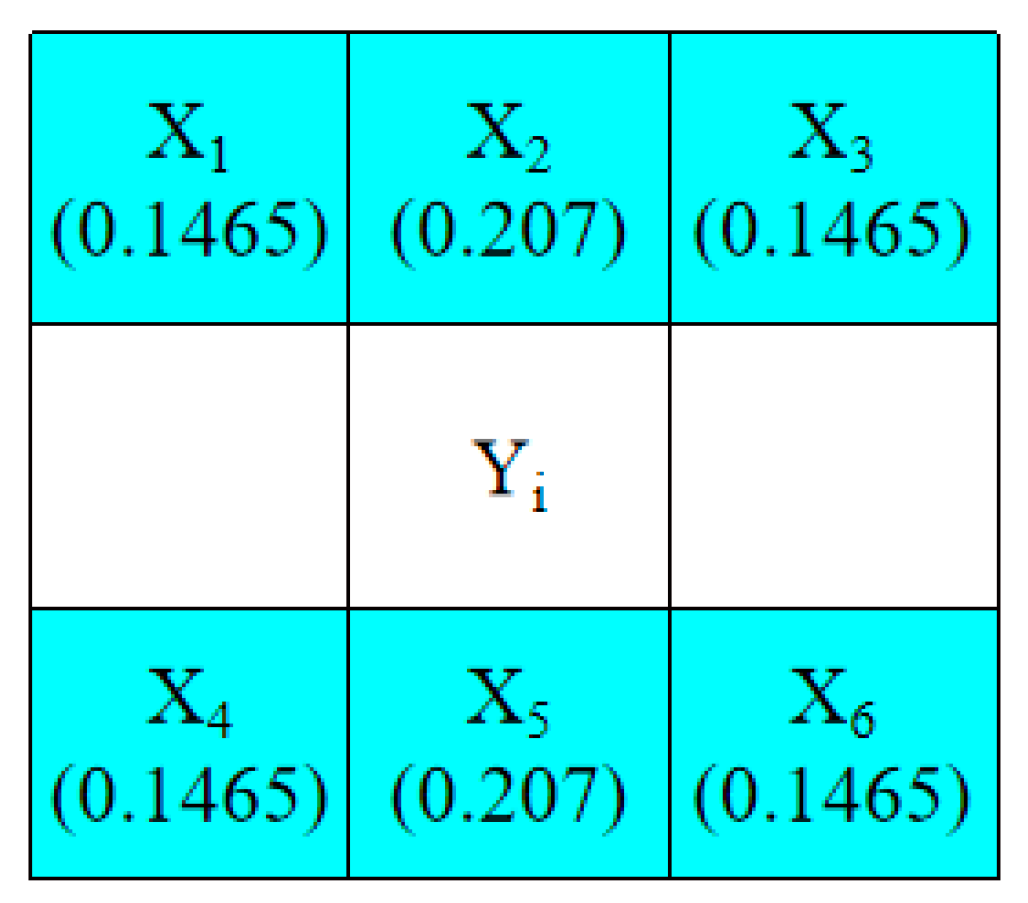

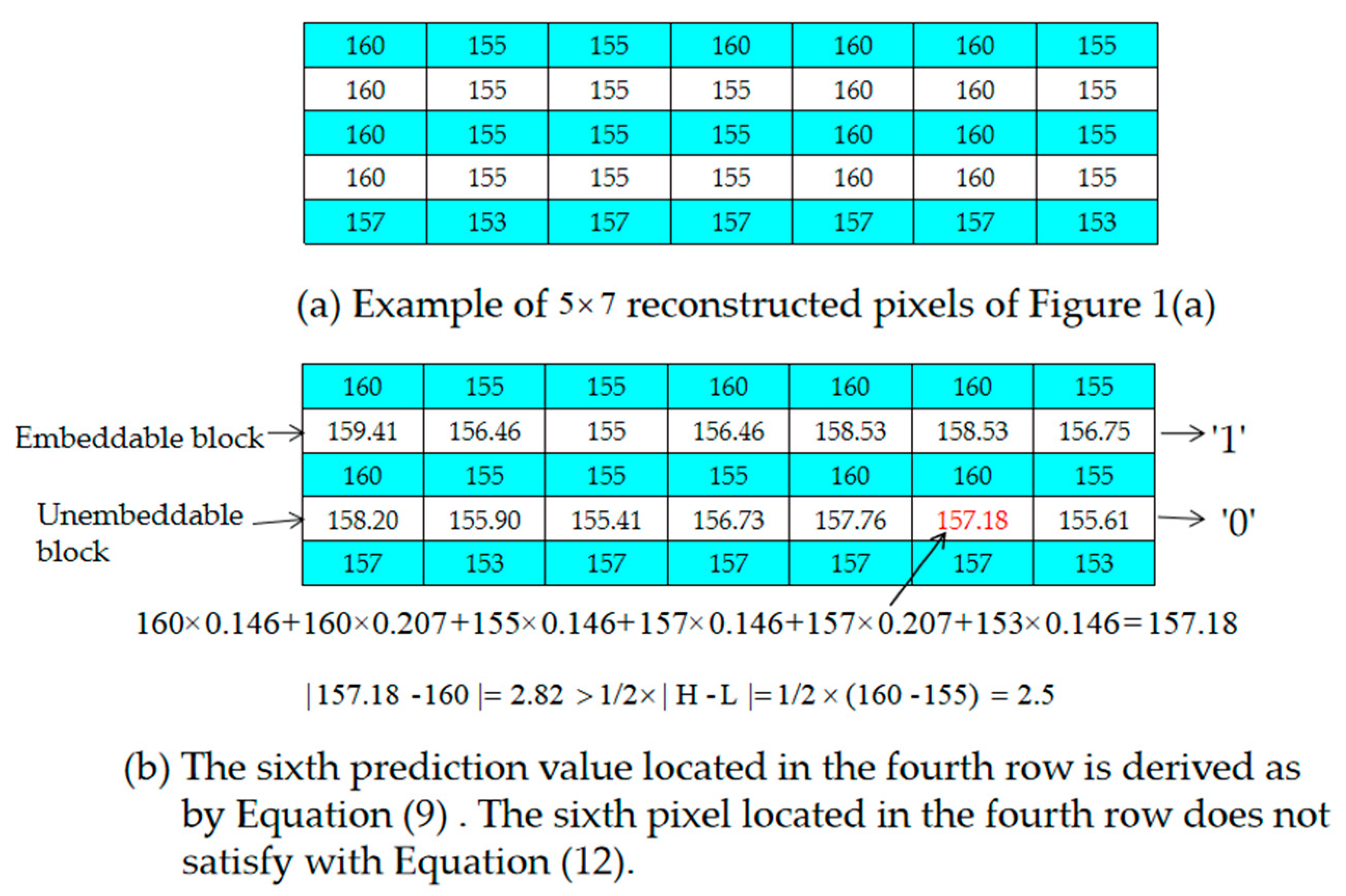

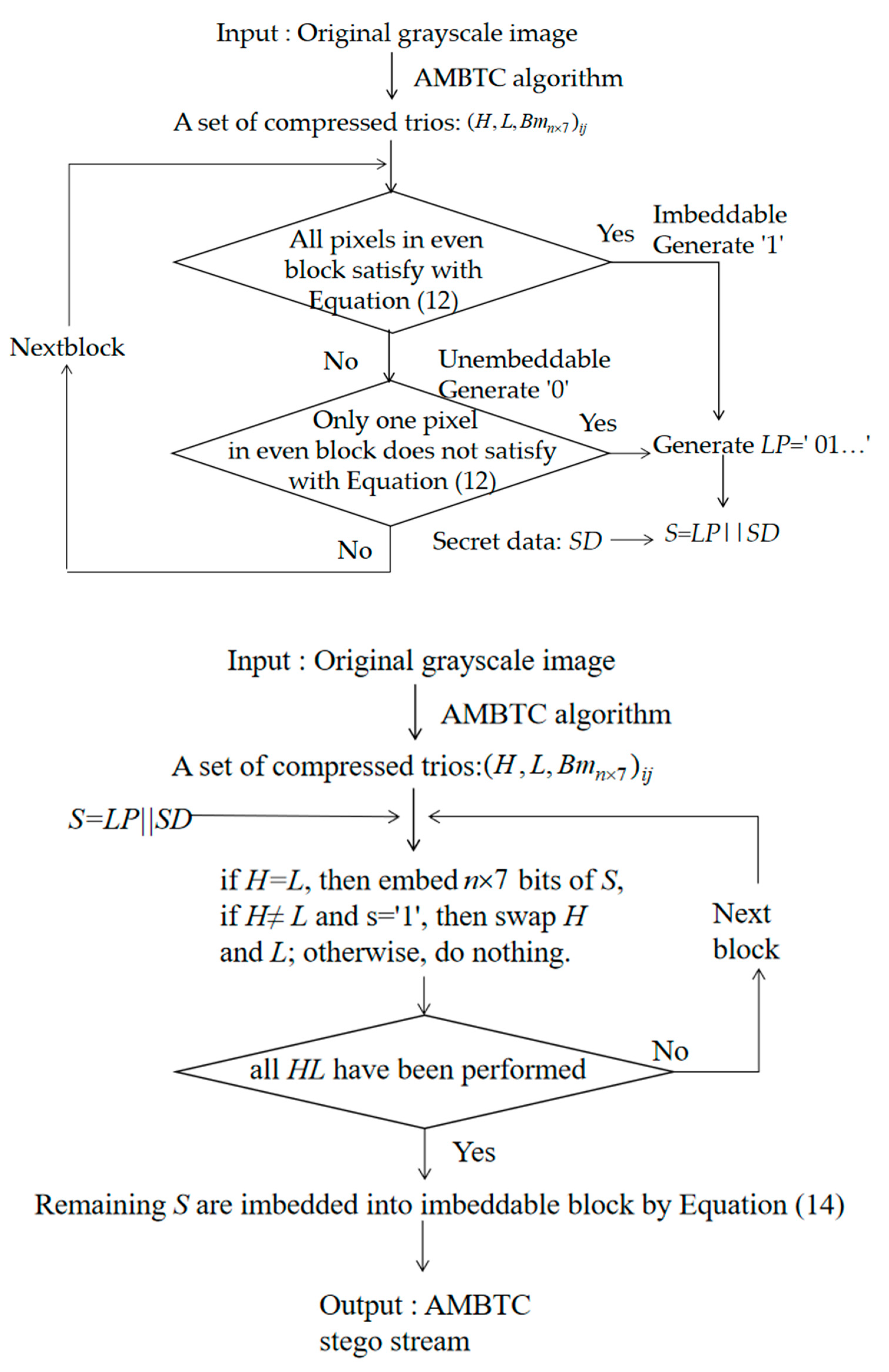

3.1. Prediction Method and Selections of Embeddable Blocks

Example of the Selection of Embeddable Blocks

3.2. Data Embedding Phase

- Step 1. Partition the original image into pixel blocks and conduct AMBTC encoding; a set of compressed trios, i.e., , is obtained, where H is the high mean table, L is the low mean table, is the bitmap, n = 4, and is the coordinate of the pixel block where and .

- Step 2. Based on their positions, use the pixels located in the odd rows to predict the pixels located in the even rows with Equations (9)–(11), respectively. If all of the pixels in a 1 × 7-sized block satisfy Equation (13), determine the block to be embeddable and denote it as “1” in the location map, LP. Otherwise, denote it as “0” in the location map, LP.

- Step 3. After all blocks have been evaluated, concatenate LP and secret data SD as the final secret message S, where S = LP||SD, and “||” denotes the concatenation of LP and SD.

- Step 4. Scan all AMBTC-compressed blocks in a zig-zag direction to embed the final secret message, S, into bitmap Bm. If H = L, 4 × 7 bits of S are selected and used to replace the original Bm. If not, H is not equal to L, select one bit, s, of S and embed it into the H and L pair by swapping the order when s = 1. Note that, if H ≠ L and s = 0, then the order of H and L is not changed.

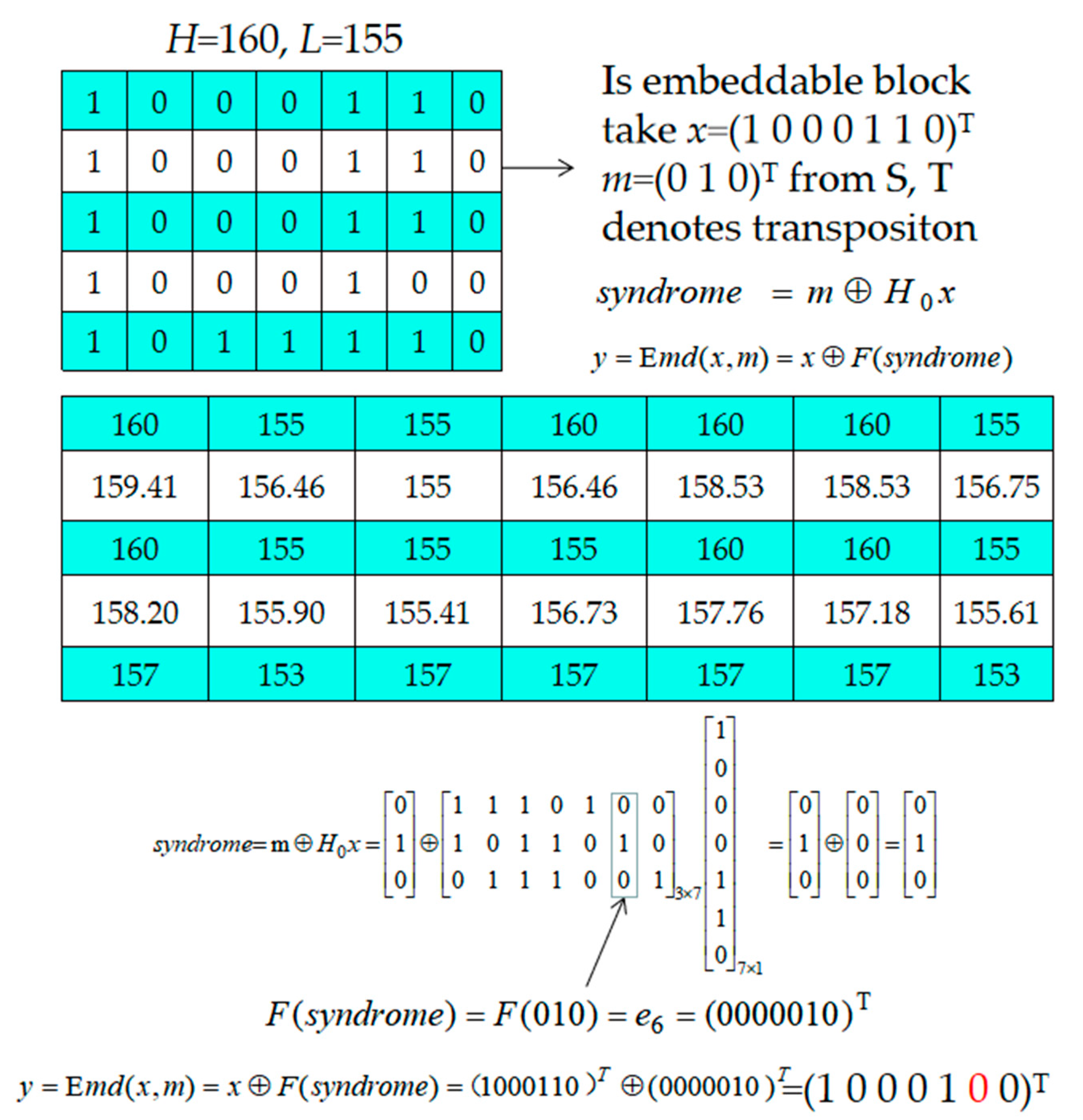

- Step 5. After all H and L pairs have been checked, take three bits of the remaining S as m and embed them into block x, which is marked with “1” in the location map LP by using Equation (14). The detailed description can be referred to Section 2.2.

Example of Data Embedding

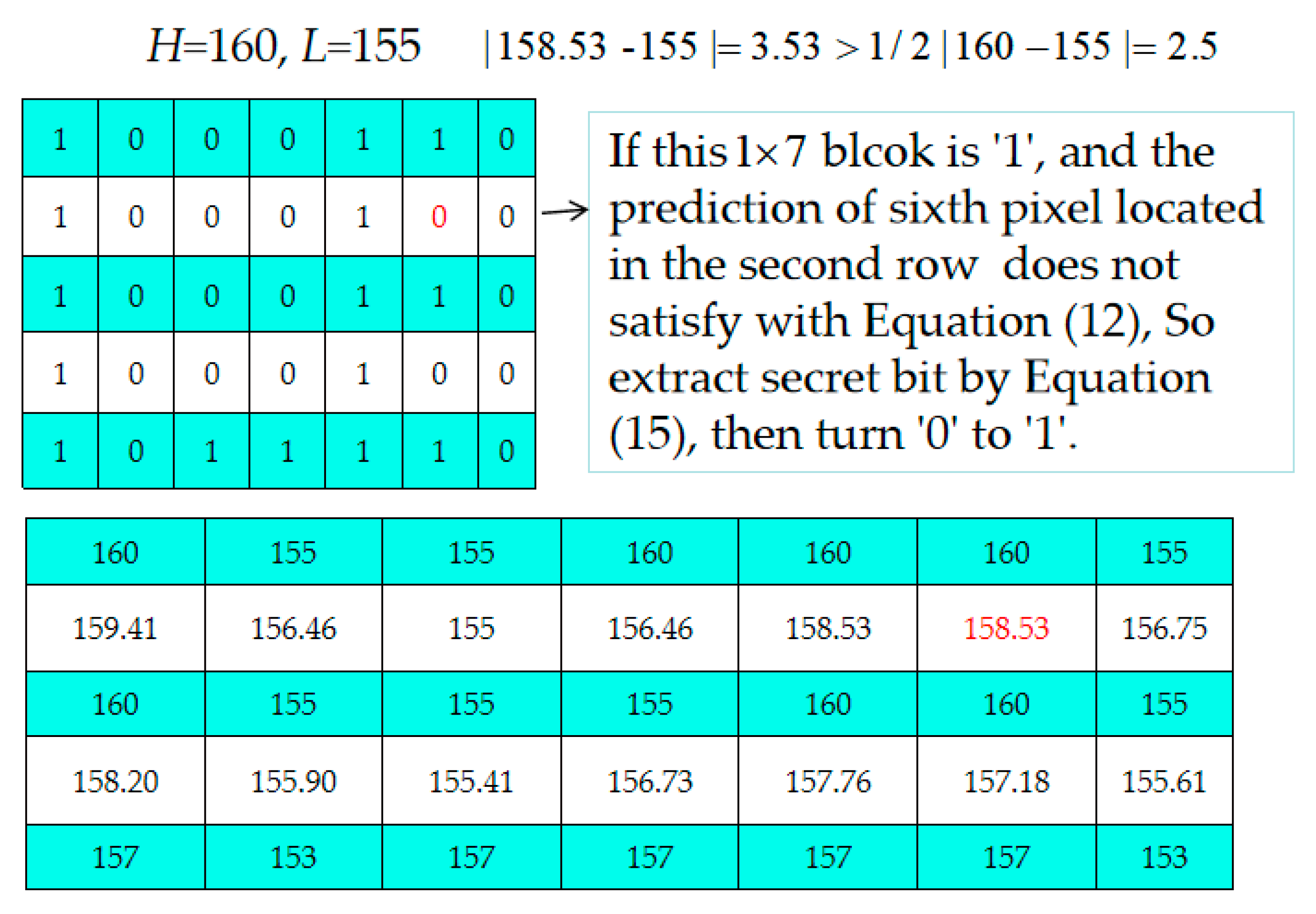

3.3. Data Extraction and Recovery Phase

- Step 1. Scan stego bitstream , and if H = L, extract 1 × 7 secret bits from the Bm. If H > L, extract secret bit “0”; otherwise, extract secret bit “1”, and swap H and L.

- Step 2. Decide which 1 × 7-sized blocks located in even rows are embeddable or not according to the extracted location map, LP. If the current block is an embeddable block, 3 bits are extracted from the corresponding 1 × 7 bits of Bm according to Equation (15) [34].If the current block is unembeddable, go to Step 4.

- Step 3. Use Equation (12) to check each pixel of the embeddable block to see it is satisfied. If one pixel is not satisfied, modify its bit value to its complementary bit value, i.e., if the current bit value is “0”, change it to “1” and vice versa.

- Step 4. Check the next embeddable block until all blocks are preceded. Output all extracted secret data and replace the corrected bitmaps with the corresponding Hs and Ls to obtain the reconstructed AMBTC-image.

Example of the Data Extraction and Recovery Phase

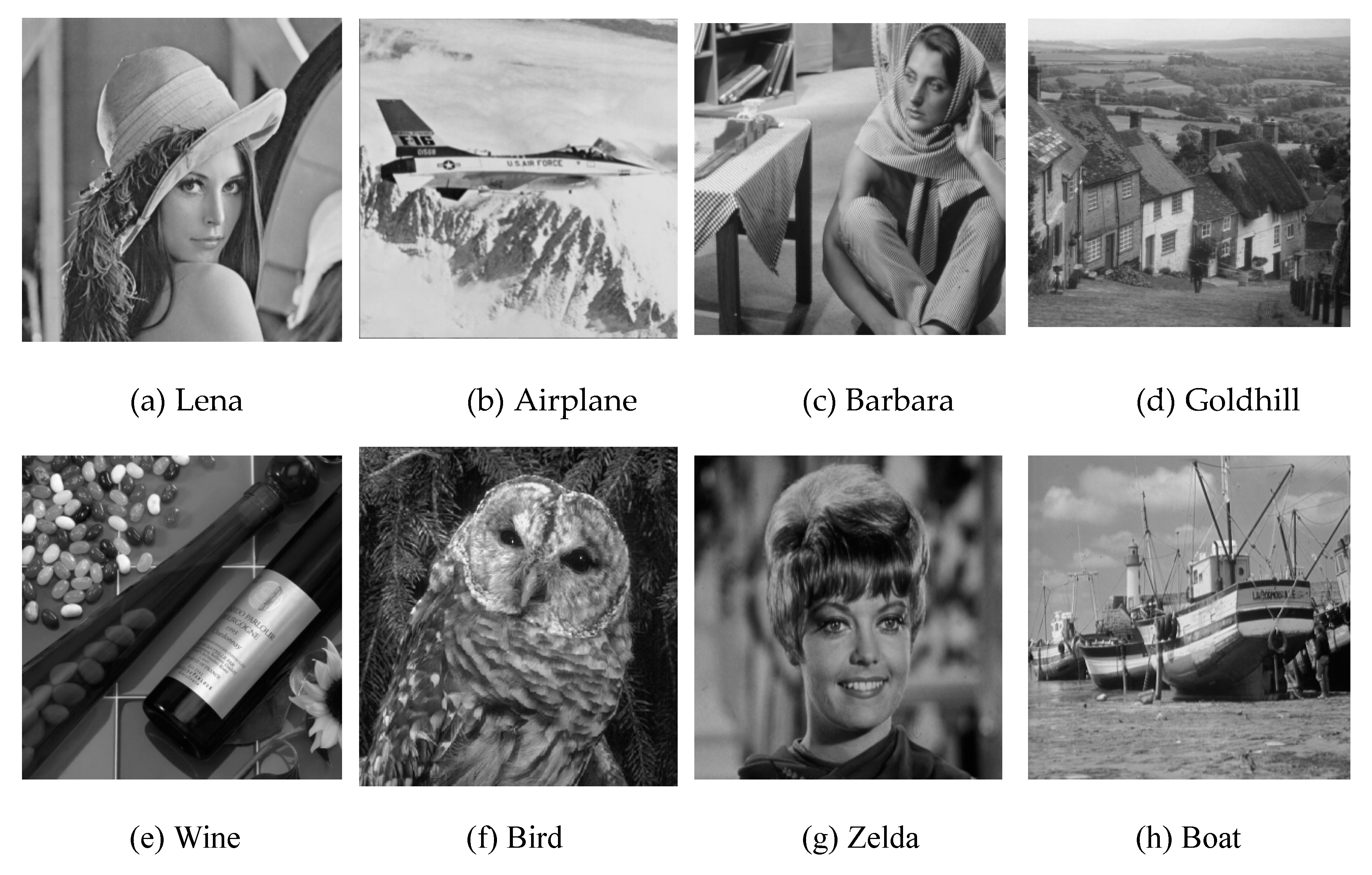

4. Experimental Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hong, W.; Chen, T.S.; Chen, J. Reversible data hiding using delaunay triangulation and selective embedment. Inf. Sci. 2015, 308, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, E.; Mazurczyk, W.; Szczpiorski, K. Trends in steganography. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.M. Method and Apparatus for Embedding Authentication Information with Digital Data. U.S. Patent 5646997, 8 July 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J. Reversible data embedding using a difference expansion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2003, 13, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Gui, X.; Yang, B. A novel reversible data hiding scheme based on two-dimensional difference-histogram modification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2013, 8, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Z.; Shi, Y.Q.; Ansari, N.; Su, W. Reversible data hiding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2006, 16, 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.C.; Tai, W.L.; Chang, C.C. Multilevel reversible data hiding based on histogram modification of difference images. Pattern Recognit. 2008, 41, 3582–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ye, J.; Wang, T. A high capacity reversible data hiding scheme based on right-left shift. Signal Process. 2018, 150, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, B.; Zeng, T. Efficient reversible watermarking based on adaptive predirection-error expansion and pixel selection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2011, 20, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Gui, X.; Yang, B. Efficient reversible data based on multiple histograms modification. IEEE Trans Inf. Forensics Secur. 2015, 10, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Li, X.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ni, R.R. Reversible data hiding based on pairwise embedding and optimal expansion path. Signal Process. 2019, 158, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Natarajan, T.; Rao, K. Discrete cosine transform. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1974, C-23, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, A. Discrete cosine transform. Math. Ann. 1911, 71, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Vector quantization. IEEE ASSP Mag. 1984, 1, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. Side match and overlap match vector quantizers for images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1992, 1, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lu, Z.; Sun, S. Reversible watermarking in the VQ-compressed domain. In Proceedings of the 5th IASTED International Conference on Visualization, Imaging, and Image Processing, Benidorm, Spain, 7–9 September 2005; pp. 273–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, B. An improved lossless data hiding scheme based on image VQ-index residual value coding. J. Syst. Softw. 2009, 82, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Tai, W.L.; Lin, C.C. A reversible data hiding scheme based on side match vector quantization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2006, 16, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.F.; Liao, I.E.; Hwang, M.S. A capacity-enhanced reversible data hiding scheme based on SMVQ. Imaging Sci. J. 2011, 59, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, E.J.; Mitchell, O.R. Image compression using block truncation coding. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1979, 27, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rover Camera Instrument Description. Available online: https://pdsimg.jpl.nasa.gov/data/mpfr-m-rvrcam-2-edr-v1.0/mprv_0001/document/rcinst.htm (accessed on 9 November 2011).

- Lema, M.; Mitchell, O.R. Absolute moment block truncation coding and its application to color images. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1984, 19, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hong, W.; Chen, T.S.; Shiu, C.W. Steganography for BTC compressed image using no distortion technique. Imaging Sci. J. 2010, 58, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.C.; Hu, Y.C.; Chen, W.L.; Wu, C.M. Reversible data hiding scheme for BTC-compressed images based on histogram shifting. Int. J. Secur. Appl. 2014, 8, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.C.; Hu, Y.C.; Chen, W.L.; Lo, C.C. High capacity reversible data hiding scheme based on residual histogram shifting for block truncation coding. Signal Process. 2015, 108, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Lu, Z.M.; Wen, Y.C.; Yu, F.X.; Shen, R.J. High performance reversible data hiding for block truncation coding compressed image. SIViP 2013, 7, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Ma, Y.B.; Wu, H.C.; Chen, T.S. An efficient reversible data hiding method for AMBTC compressed images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 5441–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Chang, C.C.; Wang, Z.M. Reversible Data hiding scheme using adaptive block truncation coding based on an edge-based quantization approach. Symmetry 2019, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Kieu, T.D.; Chou, Y.A. high payload steganographic scheme based on (7,4) hamming code for digital images. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Electronic Commerce and Security, Guangzhou, China, 3–5 August 2008; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yin, Z.; Hu, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, L. High capacity data hiding scheme based on (7,4) hamming code. Springer Plus 2016, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Chang, C.C. A high payload steganographic scheme for compressed images with hamming code. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2016, 18, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Biswapati, J.; Giri, D.; Mondal, S.K. Partial reversible data hiding scheme using (7,4) hamming code. Multimed. Tool Appl. 2017, 76, 21691–21706. [Google Scholar]

- Biswapati, J.; Giri, D.; Mondal, S.K. Dual image based reversible data hiding scheme using (7,4) hamming code. Multimed. Tool Appl. 2018, 77, 763–785. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Q. A fast algorithm for matrix embedding steganography. Digit. Signal Process. 2014, 25, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The USC-SIPI Image Database. Available online: http://sipi.usc.edu/database (accessed on 9 November 1977).

- Luigi, F.; Paolo, A.; David, B.; Ákos, Z. Cellular neural networks: A paradigm for nonlinear spatio-temporal processing. IEEE Circuits Syst. Mag. 2001, 1, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Chen, X.; Tian, Q. An Improved Reversible Image Transformation Using K-Means Clustering and Block Patching. Information 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Lin, Y.H.; Lo, Y.H.; Lo, C.C.; Wu, C.M. Implementation of Block-Based Hierarchical Prediction for Developing an Error-Propagation-Free Reversible Data Hiding Scheme. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.S. Generalized Scheme Based on Octagon-Shaped Shell for Data Hiding in Steganographic Applications. Symmetry 2019, 11, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.M.; Chang, C.C. Real-Time Error-Free Reversible Data Hiding in Encrypted Images Using (7,4) Hamming Code and Most Significant Bit Prediction. Symmetry 2019, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Min, L.Q.; Yang, H. A Reversible Watermarking Scheme for Vector Maps Based on Multilevel Histogram Modification. Symmetry 2018, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image | Lana | Airplane | Barbara | Goldhill | Wine | Bird | Zelda | Boat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 × 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 398 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 × 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 89 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Image | Lana | Airplane | Barbara | Goldhill | Wine | Bird | Zelda | Boat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of embeddable blocks | 3980 | 3482 | 3924 | 3037 | 5314 | 3676 | 4386 | 3155 |

| Number of blocks with one bit changed | 3614 | 3134 | 3556 | 2686 | 5060 | 3332 | 4006 | 2821 |

| Number of blocks without bits changed | 366 | 348 | 368 | 351 | 254 | 344 | 380 | 334 |

| Ratio 1 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.17 |

| 2 × 7 (18,688) Criteria | AMBTC PSNR (dB) | PSNR (dB) | H ≠ L HC (bits) | Proposed Scheme H ≠ L IC (bits) | H ≠ L EHC (bits) | H = L HLC (bits) | Total of HC 1 (bits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lena | 32.05 | 29.88 | 11,940 | 8612 | 3328 | 0 | 22,016 |

| Airplane | 31.9 | 29.17 | 10,446 | 7953 | 2493 | 14 | 21,194 |

| Barbara | 28.9 | 27.66 | 11,772 | 8266 | 3506 | 0 | 22,194 |

| Goldhill | 32.52 | 31.07 | 9111 | 7020 | 2091 | 84 | 20,857 |

| Wine | 32.02 | 29.9 | 15,942 | 10,456 | 5486 | 5572 | 29,348 |

| Bird | 29.57 | 28.3 | 11,028 | 8821 | 2207 | 112 | 20,999 |

| Zelda | 35.67 | 33.96 | 13,158 | 9794 | 3364 | 0 | 22,052 |

| Boat | 30.72 | 28.73 | 9465 | 7096 | 2369 | 0 | 21,057 |

| Average | 31.66 | 29.83 | 11,607 | 8502 | 3105 | 720 | 22,464 |

| 2 × 7 (9344) Criteria | AMBTC PSNR (dB) | PSNR (dB) | H ≠ L HC (bits) | Proposed Scheme H ≠ L IC (bits) | H ≠ L EHC (bits) | H = L HLC (bits) | Total of HC 1 (bits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lena | 31.29 | 29.45 | 11,907 | 8902 | 3005 | 0 | 12,349 |

| Airplane | 30.49 | 28.21 | 12,159 | 8873 | 3286 | 0 | 12,630 |

| Barbara | 28.25 | 27.17 | 12,102 | 8553 | 3549 | 0 | 12,893 |

| Goldhill | 31.35 | 30.03 | 11,286 | 8063 | 3223 | 28 | 12,594 |

| Wine | 30.84 | 29.02 | 17,511 | 11,280 | 6231 | 2492 | 17,978 |

| Bird | 28.46 | 27.43 | 11,685 | 9352 | 2333 | 0 | 11,677 |

| Zelda | 34.66 | 33.25 | 13,440 | 10,223 | 3217 | 0 | 12,561 |

| Boat | 29.60 | 27.99 | 10,983 | 8037 | 2946 | 0 | 12,290 |

| Average | 30.61 | 29.06 | 12,634 | 9160 | 3474 | 315 | 13,121 |

| Performance | Scheme | Lena | Airplane | Barbara | Goldhill | Wine | Bird | Zelda | Boat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | AMBTC | 32.05 | 31.9 | 28.9 | 32.52 | 32.02 | 29.57 | 35.67 | 30.72 |

| Chen [23] | 32.05 | 31.9 | 28.9 | 32.52 | 32.02 | 29.57 | 35.67 | 30.72 | |

| Proposed | 29.88 | 29.17 | 27.66 | 31.07 | 29.9 | 28.3 | 33.96 | 28.73 | |

| HC | Chen [23] | 18,688 | 18,701 | 18,688 | 18,766 | 23,864 | 18,688 | 18,688 | 18,792 |

| Proposed | 22,016 | 21,194 | 22,194 | 20,857 | 29,348 | 20,999 | 22,052 | 21,057 | |

| CS1 | Chen [23] | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 |

| Proposed | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | 564,736 | |

| ER | Chen [23] | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.033 |

| Proposed | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.039 | 0.037 | 0.052 | 0.037 | 0.039 | 0.037 |

| Schemes | Types | Average PSNRs | max PSNR/ min PSNR | Average HC | max HC/ min HC | Average ER | max ER/ min ER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed | I(code) | 29.83 | 33.96/27.66 | 22,464 | 29,348/20,999 | 0.04 | 0.052/0.037 |

| Chen et al. [23] | I(code) | 32.28 | 35.67/28.90 | 19,359 | 23,864/18,688 | 0.037 | 0.042/0.033 |

| Lo et al. [24] | I(code) | 33.1 | 33.23/32.97 | 3615 | 4570/2660 | 0.006 | 0.008/0.005 |

| Chang et al. [25] | I(code) | 31.74 | 32.89/30.59 | 16,381 | 12,683/20,080 | 0.031 | 0.024/0.038 |

| Sun et al. [26] | II(code) | 29.7 | 33.40/26.0 | 64,008 | 64,008/64,008 | 0.122 | 0.122/0.122 |

| Hong et al. [27] | II(code) | 30.19 | 33.39/26.91 | 64,516 | 64,516/64,516 | 0.12 | 0.116/0.125 |

| Lin et al. [28] | II(code) | 33.36 | 37.23/30.91 | 90489 | 114,533/70,889 | 0.240 | 0.241/0.217 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, J.; Lin, C.-C.; Chang, C.-C. Reversible Steganographic Scheme for AMBTC-Compressed Image Based on (7,4) Hamming Code. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101236

Lin J, Lin C-C, Chang C-C. Reversible Steganographic Scheme for AMBTC-Compressed Image Based on (7,4) Hamming Code. Symmetry. 2019; 11(10):1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101236

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Juan, Chia-Chen Lin, and Chin-Chen Chang. 2019. "Reversible Steganographic Scheme for AMBTC-Compressed Image Based on (7,4) Hamming Code" Symmetry 11, no. 10: 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101236

APA StyleLin, J., Lin, C.-C., & Chang, C.-C. (2019). Reversible Steganographic Scheme for AMBTC-Compressed Image Based on (7,4) Hamming Code. Symmetry, 11(10), 1236. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11101236