Impact of Political Economy on Land Administration Reform

Abstract

1. Introduction

“In the 1970s, donor agencies and other development practitioners sought to sidestep politics as much as possible and focus advice on technical questions and solutions, both because political incentives appeared so frequently incompatible with development in the public interest and because politics had become so deeply entangled with foreign policy considerations at the time”. ([6] p. 2)

“There is a need for a large-scale study specifically probing the political economy of land in developing countries. The literature review revealed that eventually the Bank will have to deal with the political economy concerns”. ([9] p. 42)

- (a)

- In Ghana, ongoing competition for rents between the state and customary authorities.

- (b)

- In Indonesia, resistance to policy reform, reluctance within land agencies to undertake business process re-engineering, and unwillingness to share data.

- (c)

- In the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, reluctance to improve tenure security for the poorest and a failure to encourage willingness to pay fees for registering subsequent land transactions.

- (d)

- In Thailand, political resistance to legislating for improved property valuation.

2. Literature Review and Theory

2.1. Land Administration Is Implemented by Government but Definitions Have Changed

2.2. Land Administration Standards and Guidelines

- Continuum of Rights—Developed by UN-Habitat, this concept emphasizes that effective land administration systems must recognize and provide legal protection across the full spectrum of land tenure types, including formal, informal, and customary arrangements.

- Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests (VGGTs)—Endorsed in 2012 by the Committee on World Food Security and prepared by the FAO, the VGGTs promote secure tenure rights and equitable access to land, fisheries, and forests as a foundation for eradicating hunger and poverty, supporting sustainable development, and protecting the environment.

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—Adopted by all UN Member States in 2015, the 2030 Agenda sets out 17 SDGs as a global call to action. These goals aim to end poverty, improve health and education, reduce inequality, and drive economic growth while addressing climate change and safeguarding the planet’s natural resources.

- New Urban Agenda (NUA)—Adopted at the UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) in Quito in October 2016 and later endorsed by the UN General Assembly, the NUA outlines a shared vision of inclusive, sustainable cities where everyone enjoys equal rights and access to opportunities.

2.3. Lessons from Land Administration Reform Experience

2.4. Topics That Typically Should Be Considered in Designing Land Sector Reform

2.5. Considering Political Economy in Designing Reform

- The first generation in the 1990s focused on ‘governance’ largely from a public sector management perspective.

- The second generation brought in politics with an increased emphasis on historical, structural, institutional, and political factors.

- The third generation combines elements from the first two generations and adopts assumptions, concepts, and methods from economics.

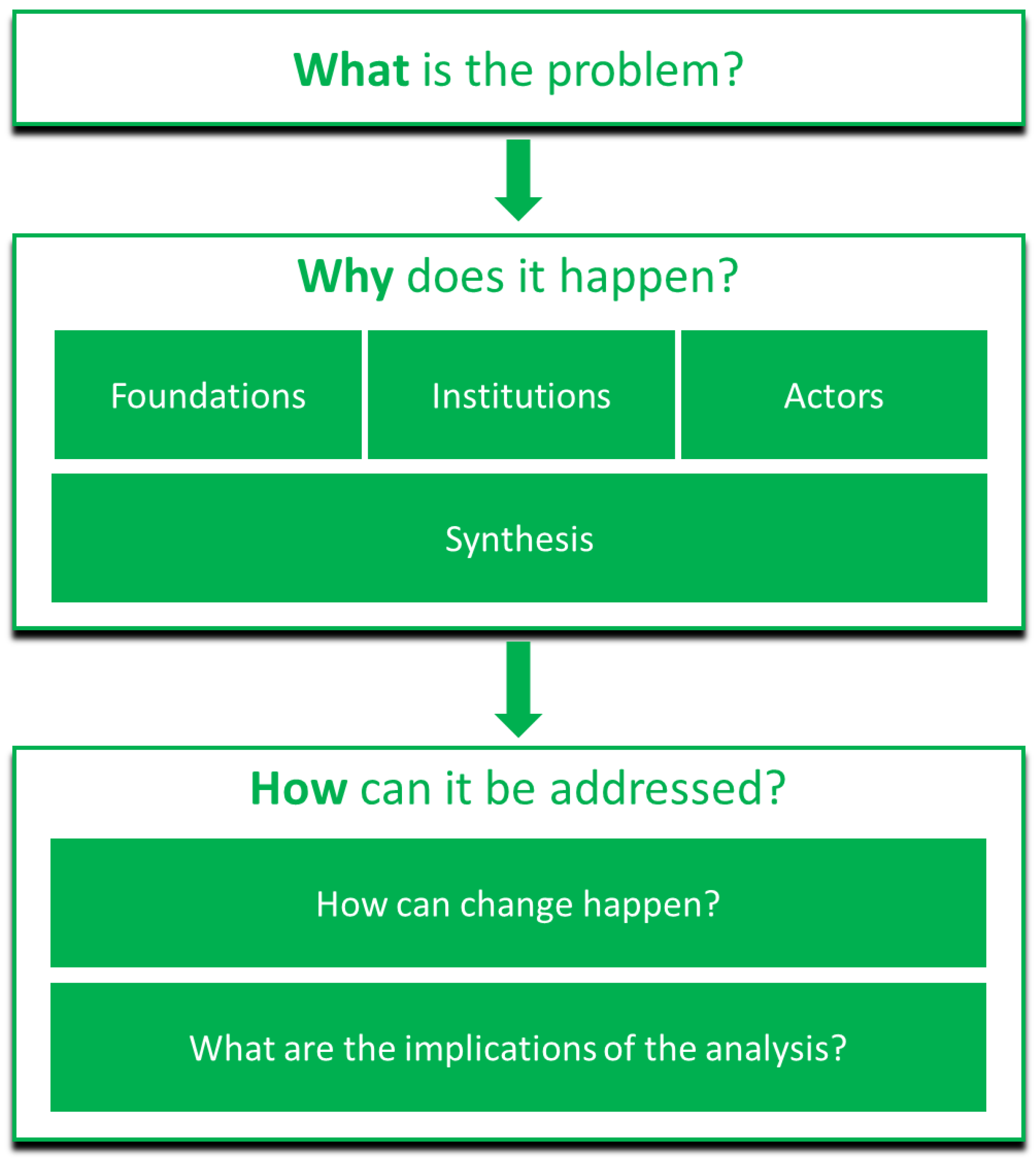

- What is the problem?

- Why does it occur?

- How can it be addressed?

- Actors or stakeholders are individuals, groups, or organizations that influence formal institutions and determine the extent to which informal institutions align with or diverge from them. In PEA, these actors may be influential participants or marginalized groups excluded from decision-making [45].

2.6. PEA and Land Administration Reform

- The potential benefits to citizens from the reform. These benefits might include tenure security, the capacity to access and utilize official land records to support investment and improved access to institutional credits secured against the property.

- The understanding of citizens of what is being expected of them in participating in the project, and

- The long-term expectation that citizens will keep their formal land registration documentation up to date.

3. Methodology

3.1. Methodology for Case Studies

- the design of the interventions, and

- the political economy issues that have impacted on project outcomes and how these issues were assessed in the design of the interventions.

3.2. Methodology for Key Informant Interview

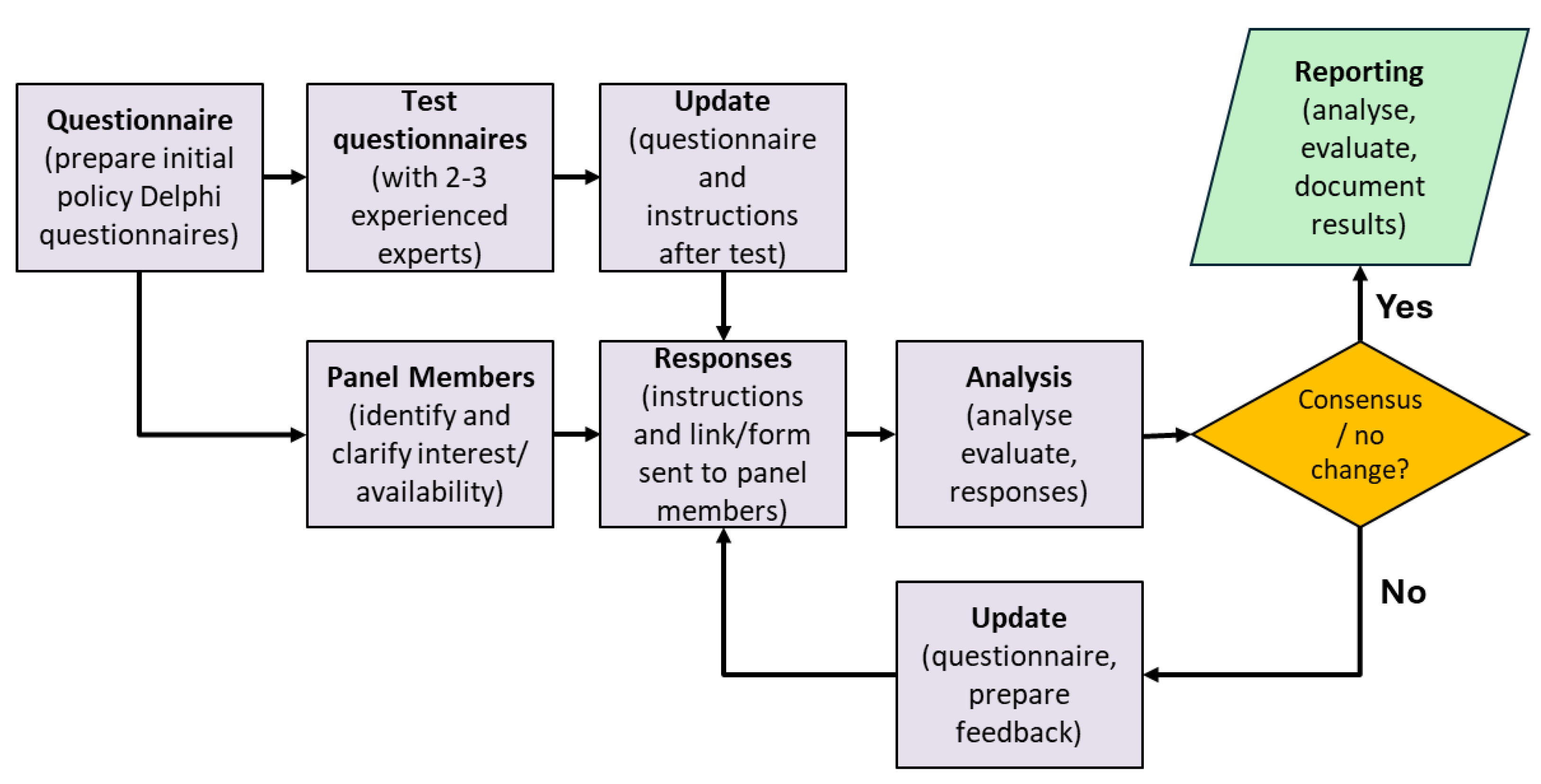

3.3. Methodology for Policy Delphi Survey

- (a)

- will PEA be useful in designing land administration reform?

- (b)

- Can PEA be successfully completed in the timeframes typically available for the design of reform?

- Anonymous participation by the experts.

- More than one round of questionnaires.

- Feedback to experts after each iteration.

- Statistical analysis to assess the opinion of the panel of experts.

4. Results—Case Studies—Key Informant Interviews—Policy Delphi Survey

4.1. Results from the Case Studies

- Cumbersome, difficult to access land registration processes are noted in all three countries, as is limited public awareness of land policy and land law.

- There is also resistance from customary leaders in Ghana and the landed elite in Indonesia.

- Resistance from staff and professional service suppliers (cadastral surveyors in Ghana and Tanzania and notaries in Indonesia) is also apparent in the three countries.

4.2. Results from the Key Informant Interviews

- Ghana

- Reform should not be too ambitious; there should be strong capacity in the implementing agency and development partners supporting reform need to be aligned in reform objectives and activity.

- The project decision to work within the current policy and legal framework has been strongly criticized in the literature and in the independent evaluations of project outcomes but key informants felt that there was a strong argument that any effort to clarify the role of the state would not have succeeded.

- Successful land administration reform in Ghana needs to have a strong policy champion.

- Indonesia

- Land administration reform in Indonesia requires a long-term engagement.

- The suggestion that a land administration reform project in a country like Indonesia needs to focus on policy reform rather than technical matters is not realistic. The investment in technical efforts has resulted in changes in policy and enabled the project and the land agency to take advantage of policy windows that have arisen.

- Changing deeply rooted business practices needs more than consultant reports and the input of external agencies.

- Tanzania

- Good policy and laws and cost-effective, efficient procedures are important foundations for land administration reform but there needs to be a clear and effective mechanism to deliver the reform in the towns, districts, and villages.

- A champion at policy level is needed to support successful land administration reform in Tanzania.

4.3. Results from the Policy Delphi Survey

- Eight of the participants had more than 20 years of experience, five had 10 to 20 years of experience and two had 5 to 10 years of experience.

- Thirteen individuals had been employed by government, eleven had been employed by development partners, nine had been employed as consultants and five had been employed by academic, civil society and other employers.

- Fifteen individuals had experience in policy roles, twelve had experience in management roles, fourteen had experience in technical roles, and five had experience in administrative roles.

- (a)

- Power analysis and sensitivity analysis. One panelist in the round 2 responses consistently noted that power analysis and sensitivity analysis were alternative approaches to PEA without providing any details or context. Power analysis is a term used by development and social change specialists to understand how power can reinforce or reduce poverty and marginalization and to identify how positive forms of power can be mobilized [65]. The advantages listed for power analysis include enhanced sensitivities and competencies in ways to empower marginalized people and the identification of possible perverse consequences. The disadvantages of power analysis include a requirement for a certain level of understanding and ability to apply key concepts of structure and agency and the risk that the process may be applied in a superficial and limited manner [65]. Power analysis was established by SIDA [66] and has been used extensively by some international NGOs, particularly Oxfam (https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/handle/10546/313950, accessed 28 July 2025). The available material on power analysis seems to be dated with very limited information found that documents the successful application of power analysis by government or development partners in designing reform. However, there is the possibility of using PEA and power analysis in complementary ways to make development cooperation more effective and transformative [65]. For these reasons power analysis is not seen at this stage as a replacement or alternative to PEA in the design of land administration reform at this stage, but the methodology is noted as one worth further research.

- (b)

- Hedonic pricing model and social mapping. One panelist suggested hedonic pricing model and social mapping as an alternative approach to PEA in a response to one scenario. The hedonic pricing model is an economic approach used to estimate the value of a good or service by breaking it down into its constituent characteristics. The price of a product is seen as the sum of the prices of its individual attributes. This model is widely used in real estate to assess how different factors like location, view, and proximity to amenities affect property prices. Social mapping involves categorizing spaces based on their social and use values. It is used to understand how different areas are perceived and utilized by communities. A hedonic pricing model and social mapping have been used to categorize urban green spaces in Stockholm [67]. It is unclear how the process might be used to address the problem of keeping property in the formal land administration system, the problem nominated in the scenario. At this stage it is left as a topic for further research.

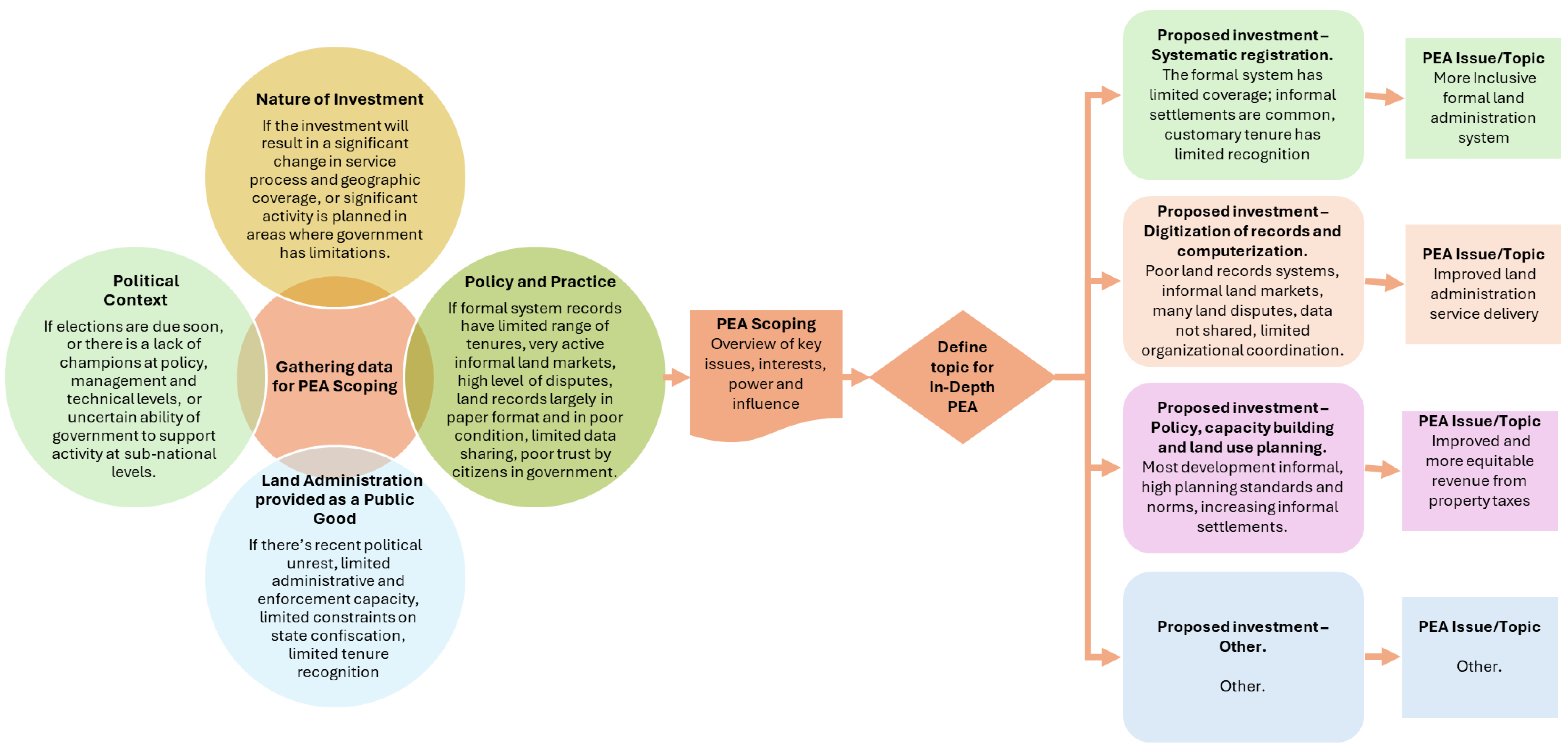

5. Framework to Consider Political Economy in Reform Design

5.1. PEA Scoping

- The nature of the investment that is being funded under the project.

- The existing land administration policy and practices.

- The ability of the state to provide land administration services as a public good.

- The existing political context.

5.2. In-Depth PEA

5.3. Validation of the Framework

- You are designing a land administration reform in the country you are currently working in. Do you use PEA to support your design?

- Are the four drivers described in the framework appropriate?

- Is this a good framework to identify the key problems to investigate in the reform design?

- The Framework proposes a register of the political economy issues and drawing information from the sources, filtering and prioritizing the main PEA issues. Is this a good approach?

- What resources are needed to undertake PEA as part of the design process?

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

- (a)

- Power analysis and sensitivity analysis. The available material on power analysis seems to be dated with very limited information found that documents the successful application of power analysis by government or development partners in designing reform. However, there is the possibility of using PEA and power analysis in complementary ways to make development cooperation more effective and transformative. Power analysis is not seen at this stage as a replacement or alternative to PEA in the design of land administration reform at this stage, but the methodology is noted as one worth further research.

- (b)

- Hedonic pricing model and social mapping. It is unclear how the hedonic pricing model and social mapping might be used to address the problem of keeping property in the formal land administration system, the problem nominated in scenario 1, the problems listed in the other scenarios or more broadly how the process would be a better alternative to PEA in addressing political problems in designing land administration reform. At this stage it is left as a topic for further research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAL | Basic Agrarian Law (Indonesia) |

| BPN | National Land Agency (Indonesia) |

| CIDA | Canadian International Development Agency |

| CMU | Country Management Unit (World Bank) |

| DFID | Department for International Development (UK, now FCDO) |

| DLP | Development Leadership Programme |

| DANIDA | Danish International Development Agency |

| FAO | Food and Agricultural Agency (UN) |

| FCDO | Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (UK) |

| FFPLA | Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration |

| FGD | Focus group discussions |

| FIG | International Federation of Surveyors |

| ICT | Information and communications technology |

| INSPIRE | Infrastructure for spatial information in Europe to support Community environmental policies, established under the INSPIRE Directive. |

| IQR | Inter-quartile range |

| KII | Key informant interviews |

| LAP | Land Administration Project |

| LGAF | Land governance assessment framework (World Bank) |

| LGI | Land governance indicator |

| LINK | Land International Network for Knowledge |

| LMA | Land Markey assessment |

| LTRS | Land Tenure and Records System (MCC) |

| MCC | Millennium Challenge Corporation (US) |

| NGO | Non-government organization |

| NUA | New Urban Agenda |

| PCM | Participatory comm unity mapping |

| PDIA | Problem-driven iterative adaptation |

| PEA | Political economy analysis. |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SIDA | Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency |

| TWP | Thinking and Working Politically |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNECE | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe |

| US | United States of America |

| USAID | US Agency for International Development |

| VGGTs | Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (UN) |

| WGI | World Governance Indicator (World Bank) |

Appendix A

| Country/Project | Duration | Cost | Objectives | Rating 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana Land Administration Project (World Bank with CIDA providing US$1.3 m, Germany US$3.8 m, Nordic Development Fund US$9.2 m, DFID US$7.4 m) Implementation Completion Report Review: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/805541474634688190/pdf/000020051-20140625080330.pdf (accessed 28 July 2025) | 2004–2011 | US$48.1 m | Develop a sustainable and well-functioning land administration system that is fair, efficient, cost-effective, decentralized, and that enhances tenure security. | MU |

| Ghana Land Administration Project 2 (World Bank US$46.7 m, CIDA US$2.5 m) IEG Implementation Complement Report Review: https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/460521609406326577/pdf/Ghana-GH-Land-Administration-2.pdf (accessed 28 July 2025) | 2011–2018 | US$49.2 m | To support the Recipient’s efforts to consolidate and strengthen land administration and management systems for efficient and transparent land service delivery. | MU |

| Indonesia Land Administration Project (World Bank US$46.1 m, Australian Government US$20 m and Government of Indonesia US14.6 m) Operations Evaluation Department Implementation Completion Review Report: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/867061474572889181/pdf/000020051-20140607153814.pdf (accessed 28 July 2025) | 1995–2001 | US$80.7 m | To foster efficient and equitable land markets and alleviate social conflicts over land, through acceleration of land registration, and through improvement of the institutional framework for land administration needed to sustain the program. | S |

| Indonesia Land Management and Policy Development (World Bank) Implementation Performance Assessment Report: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/867061474572889181/pdf/000020051-20140607153814.pdf (Accessed 28 July 2025) | 2004–2010 | US$87.62 m | Improve land tenure security and enhance efficiency, transparency and improve service delivery of land titling and registration. | US |

| Tanzania Private Sector Competitiveness Project (World Bank US$137.6 m, Bank administered Trust Fund US$15.7 m) | 2006–2018 | US$153.3 m | To strengthen the business environment in Tanzania, including land administration reform, and improve access to financial services. | MS |

| Tanzania Land Tenure Support Program (DFID US$6.2 m, SIDA US$3.4 m and DANIDA US$2.3 m, Government 0.3 m) IEG Implementation Completion Report Review: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/128441562964284969/pdf/Tanzania-TZ-Private-Sector-MSME-Competitiveness.pdf (Accessed 28 July 2025) | 2016–2019 | US$12.2 m | To establish a road map for long term support to the land sector and contribute to implementing the revised Strategic Plan to implement the Land Laws (SPILL), while achieving concrete results during the three-year program period to make significant contributions to improving the transparency and efficiency of land administration and governance. | |

| Tanzania Feed the Future Land Tenure Assistance Activity (USAID US$6.052 m) Data from the LTA final report—https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00Z2NF.pdf (accessed 2 December 2024) | 2015–2021 | US$6.052 m | The objectives of the first phase were: (i) to assist villages in completing the land use planning process and delivering CCROs using MAST; (ii) build the capacity of village and district land governance institutions and individual villagers; (iii) raise awareness of MAST technology in government, civil society, academe, and the private sector in Tanzania. |

Appendix B

| Political Feature as Specified by Cai et al. [3] | Key Issues/Problem | Proposed Modified Formulation |

|---|---|---|

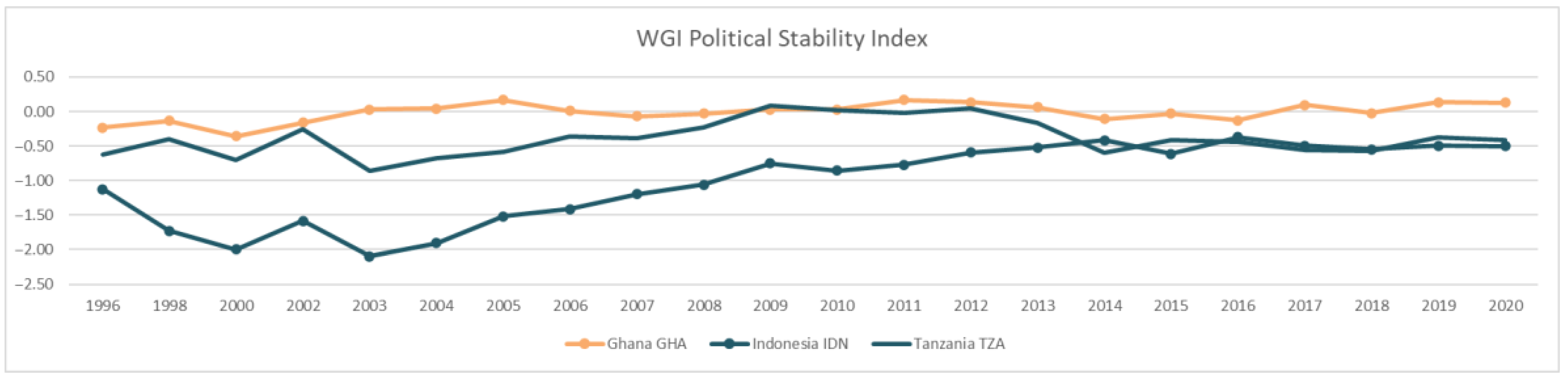

| Political stability—the state has established authority over sufficient territory to be able to establish systems to protect property rights, this will encourage investment and production and there is political stability that enables the state to become a ‘stationary bandit’ to claim ongoing future income through fees and taxes | There is a lack of consensus on what the term “political stability” means and a number of different approaches to assess political stability, including: (a) the absence of violence; (b) government longevity/duration; (c) existence of a legitimate constitutional regime; (d) absence of structural change; and (e) a multifaceted societal attribute [70] | Adopt the political stability indicator used by the World Bank as one of the six indicators of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators, Accessed 28 July 2025). The World Bank time series political stability indicators are available on the theGlobalEconomy.com website—https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_political_stability/ |

| Administrative and enforcement capacity—the state has the capacity to gather information on property rights and enforce these rights. Cai et al. (2020) [3] saw this evidenced by the ability to implement cadastral surveys and the availability of police and the military to enforce the rights. | The measures used to assess administration and enforcement capacity—cadastral surveying and availability of police and military—are overly simplistic. There is a lot of experience in the land sector in assessing administrative and enforcement capacity. | Adopt the following LGAF indicators/dimensions:

|

| Political constraints on the state’s ability to confiscate property—separation of powers at the national level and effective transfer of authority to lower levels of government are seen as important constraints on the state’s ability to confiscate property without due process and fair compensation. | The attempt to link the political constraints to the state’s ability to confiscate property to a separation of powers lacks credibility. There are more direct measures of the effectiveness of political constraints on the expropriation of property in the land sector tools such as LGAF. | Adopt the following LGAF indicators/dimensions:

|

| The extent to which political and legal institutions are inclusive—covering the extent to which there is competition and autonomy between local governments and inclusion of non-government organizations in the political dialogue. This factor also includes an assessment of the accessibility and equity in the judicial system. | Linking competition and autonomy of local governments and the inclusion of NGOs in the political dialogue to the assessment of whether the political and legal institutions are inclusive is tenuous. There are more direct measures of inclusive institutions for the protection and enforcement of property rights in land sector tools such as LGAF. | Adopt the following LGAF indicators/dimensions:

|

| Political Feature | Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political stability (Data downloaded from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators, Accessed 28 July 2025) |  | |||

| (Assessments from LGAF studies completed in 2/2012 in Ghana, 1/2015 in Indonesia (Kalimantan) and 1/2015 in Tanzania https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/land-governance-assessment-framework#2, Accessed 28 July 2025) | Ghana | Indonesia | Tanzania | |

| Administrative and enforcement capacity |

| D D D D C D | D D D D D D | B B C D D D |

| Political constraints on the state’s ability to confiscate property |

| A D D C | D C D C | A A D C |

| The extent to which political and legal institutions are inclusive |

| A B A B C B | D D B B n/a n/a | B D A B C C |

Appendix C. Quantitative Data Analysis of Policy Delphi Data

| Problem | Question | Response Rate | Coefficient of Variation | IQR | Positive Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1. Properties registered by systematic registration may not remain in the formal system. | PEA useful | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Scenario 2. No clear plan to ensure that the investment will be sustainable financially. | PEA useful | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 75% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Scenario 3. No clear plan to ensure that the investment will be sustainable technically. | PEA useful | 75% | 0.6 | 1.0 | 87% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 75% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 75% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 93% | |

| Scenario 4. Other agencies may fail to provide the necessary support or resist reform. | PEA useful | 75% | 0.4 | 0.5 | 93% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 75% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 93% | |

| Scenario 5, The land agency and/or staff and/or service providers are not prepared to consider changes in business processes. | PEA useful | 75% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 80% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 75% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 80% | |

| Confident in response | 75% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 93% |

| Scenarios/Questions | Round 1 | Round 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation | IQR | Positive Response | Coefficient of Variation | IQR | Positive Response | ||

| Scenario 1 | PEA useful | 0.6 | 1.0 | 85% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 0.3 | 0.0 | 77% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 0.4 | 1.0 | 92% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Scenario 2 | PEA useful | 0.4 | 1.0 | 92% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 0.5 | 2.0 | 69% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 0.4 | 1.0 | 92% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Scenario 3 | PEA useful | 0.6 | 1.0 | 77% | 0.6 | 1.0 | 87% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 0.4 | 1.0 | 77% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 0.5 | 1.0 | 85% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 93% | |

| Scenario 4 | PEA useful | 0.4 | 1.0 | 92% | 0.4 | 0.5 | 93% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 0.4 | 1.0 | 54% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 87% | |

| Confident in response | 0.5 | 1.0 | 77% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 93% | |

| Scenario 5 | PEA useful | 0.6 | 2.0 | 69% | 0.5 | 1.0 | 80% |

| PEA can be completed in time | 0.4 | 2.0 | 69% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 80% | |

| Confident in response | 0.5 | 1.0 | 85% | 0.4 | 1.0 | 93% | |

References

- Woetzel, J.; Mischke, J.; Madgavkar, A.; Windhagen, E.; Smit, S.; Birshan, M.; Kemeny, S.; Anderson, R.J. The Rise and Rise of the Global Balance Sheet: Executive Summary; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/financial%20services/our%20insights/the%20rise%20and%20rise%20of%20the%20global%20balance%20sheet%20how%20productively%20are%20we%20using%20our%20wealth/mgi-the-rise-and-rise-of-the-global-balance-sheet-es-vf.pdf?shouldIndex=false (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- UNECE. Land Administration Guidelines: With Special Reference to Countries in Transition; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996; Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/hlm/documents/Publications/land.administration.guidelines.e.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Cai, M.; Murtazashvili, I.; Murtazashvili, J. The politics of land property rights. J. Institutional Econ. 2020, 16, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törhönen, M.-P. Keys to Successful Land Administration: Lessons Learned in 20 Years of ECA Land Projects; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24623 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Napier, M.; Berrisford, S.; Kihato, C.W.; McGaffin, R.; Royston, L. Trading Places: Accessing Land in African Cities; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2013; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, V.; Levy, B.; Ort, R. (Eds.) Problem-Driven Political Economy Analysis: The World Bank Experience; World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2014; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Weingast, B.R.; Wittman, D.A. The Reach of Political Economy. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2008; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, S. Land Policy Dialogues: Addressing Urban-Rural Synergies in World Bank Facilitated Dialogues in the Last Decade; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/770411468149091564/pdf/705690ESW0P1030C00000Final0LP0Repor.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- World Bank. Lessons from Land Administration Projects: A Review of Project Performance Assessments; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/145041468001168154/pdf/Lessons-from-land-administration-projects-a-review-of-project-performance-assessments-IEG-category-one-learning-product.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Dale, P.F.; McLaughlin, J.D. Land Administration; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, C.R.; Kerekes, C.B. Securing Private Property: Formal versus Informal Institutions. J. Law Econ. 2011, 54, 537–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dercon, S. Gamblimg on Development: Why Some Countries Win and Others Lose; C. Hurst & Co: London, UK, 2022; p. 398. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, I.P. Land administration “best practice” providing the infrastructure for land policy implementation. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudler, D.; Rajabifard, A.; Williamson, I.P. Evaluation of land administration systems. Land Use Policy 2004, 21, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; ESRI Press Academic: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010; p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- English, C.; Locke, A.; Quan, J.; Feyertag, J. Securing Land Rights at Scale: Lessons and Guiding Principles from DFID Land Tenure Regularisation and Land Sector Support Programmes; DFID LEGEND Report: Kigali, Rwanda, 2019; p. 42. Available online: https://www.landportal.org/library/resources/securing-land-rights-scale (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Burns, A.F.; Rajabifard, A.; Shojaei, D. Undertaking land administration reform: Is there a better way? Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S. Debating the Land Question in Africa; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 638–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulmin, C.; Quan, J. (Eds.) Evolving Land Rights, Policy and Tenure in Africa; DFID/IIED/NRI: London, UK, 2000; p. 297. [Google Scholar]

- Amanor, K.S. Land Governance in Africa: How historical context has shaped key contemporary issues related to policy on land. In Framing the Debate Series; International Land Coalition: Rome, Italy, 2012; Available online: https://d3o3cb4w253x5q.cloudfront.net/media/documents/FramingtheDebateLandGovernanceAfrica.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Lavigne Delville, P. Harmonising Formal Law and Customary Land Rights in French-Speaking West Africa; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 1999; Available online: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=e6123dd5-ccd1-37ee-a073-49e8da235923 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Pedersen, R. Decoupled Implementation of New-Wave Land Reforms: Decentralisation and Local Governance of Land in Tanzania. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.F.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Afiff, S.; Robinson, K. Land reform rationalities and their governance effects in Indonesia: Provoking land politics or addressing adverse formalisation? Geoforum 2022, 132, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Lasserve, A.; Durand-Lasserve, M.; Selod, H. A Systemic Analysis of Land Markets and Land Institutions in West African Cities: Rules and Practices—The Case of Bamako, Mali. In Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/889891468049214422/pdf/WPS6687.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Barry, M.; Augustinus, C. Framework for Evaluating Continuum of Land Rights Scenarios; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/Framework%20for%20Evaluating%20Continuum%20of%20Land%20Rights%20Scenarios_English_2016.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Kironde, J.M.L. Understanding land markets in African urban areas: The case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Habitat Int. 2000, 24, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowall, D.E. The Land Market Assessment: A New Tool for Urban Management; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/296941468764366469/pdf/The-land-market-assessment-a-new-tool-for-urban-management.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Dowall, D.E.; Leaf, M. The price of land for housing in Jakarta. Urban Stud. 1991, 28, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowall, D.E.; Ellis, P.D. Urban Land and Housing Markets in the Punjab, Pakistan. Urban Stud. (Sage Publ. Ltd.) 2009, 46, 2277–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellman, B.; Eakin, H.; Janssen, M.A.; de Alba, F.; Ii, B.T. The role of institutional entrepreneurs and informal land transactions in Mexico City’s urban expansion. World Dev. 2021, 140, 105374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.W.; Knox, A. Structures and Stratagems: Making Decentralization of Authority over Land in Africa Cost-Effective. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J. Decentralization of Land Administration in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recent Experiences and Lessons Learned. In Agricultural Land Redistribution and Land Administration in Sub-Saharan Africa: Case Studies of Recent Reforms; Chapter 3; Byamugisha, F., Ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 55–84. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4aa5f57b-cb5b-5fc0-a9a5-881b03ec96dc/content (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Biitir, S.B.; Miller, A.W.; Musah, C.I. Land Administration Reforms: Institutional Design for Land Registration System in Ghana. J. Land Rural. Stud. 2021, 9, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C.; Dyzenhaus, A.; Manji, A.; Gateri, C.W.; Ouma, S.; Owino, J.K.; Gargule, A.; Klopp, J.M. Land law reform in Kenya: Devolution, veto players, and the limits of an institutional fix. Afr. Aff. 2019, 118, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, E. Reform and resistance: The political economy of land and planning reform in Kenya. Urban Stud. (Sage Publ. Ltd.) 2020, 57, 1164–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carothers, T.; Gramont, D.D. Development Aid Confronts Politics: The Almost Revolution; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E.; Marquette, H. Thinking and Working Politically: Reviewing the Evidence on the Integration of Politics into Development Practice over the Past Decade; TWP Community of Practice: Birmingham, UK, 2018; Available online: https://twpcommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Thinking-and-working-politically-reviewing-the-evidence.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- McCulloch, N.; Piron, L.-H. Thinking and Working Politically: Learning from Practice. Dev. Policy Rev. 2019, 37, O1–O15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, W. Putting Political Economy to Use in Aid Policies. Third World Q. 2012, 33, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, S. Donor Political Economies and the Pursuit of Aid Effectiveness. Int. Organ. 2016, 70, 65–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautigam, D. Governance, economy, and foreign aid. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 1992, 27, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K.A.; Booth, D.; Wild, L. Doing Development Differently at the World Bank: Updating the Plumbing to Fit the Architecture; ODI: London, UK, 2016; p. 57. Available online: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/10867.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Hudson, D.; Leftwich, A. From Political Economy to Political Analysis; DLP: Birmingham, UK, 2014; Available online: https://dlprog.org/publications/research-papers/from-political-economy-to-political-analysis/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Whaites, A.; Piron, L.H.; Menocal, A.R.; Teskey, G. Understanding Political Economy Analysis and Thinking and Working Politically; FCDO and TWP CoP: Birmingham, UK, 2023. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/63fca3bd8fa8f527f310d47d/Understanding_Political_Economy_Analysis_and_Thinking_and_Working_Politically.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Harris, D. Applied Political Economy Analysis: A Problem-Driven Framework; ODI: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://media.odi.org/documents/8334.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Burns, A.F.; Rajabifard, A.; Shojaei, D. Adopting a Politically Informed Approach to the Design of Land Administration Reform. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Land Management Conference, LINK—Land—International Network for Knowledge, Bristol, UK, 14–15 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, V.; Kaiser, K.; Levy, B. Problem-Driven Governance and Political Economy Analysis: Good Practice Framework. 2009. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a8ccade5-fe50-564c-9907-c07466008e49/content (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Samji, S.; Andrews, M.; Pritchett, L.; Woolcock, M. PDIA Toolkit: A DIY Approach to Solving Complex Problems; Center for International Development, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; p. 60. Available online: https://bsc.hks.harvard.edu/tools/toolkit/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 5, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aenis, T. Stakeholder analysis in support of sustainable land management: Experiences from southwest China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 243, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, C.; Cordell, D.; Jacobs, B.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Marshall, R.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; Sherry, E. Five pillars for stakeholder analyses in sustainability transformations: The global case of phosphorus. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaventa, J. Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, R.B. Transparency in Land Title Registration: Strategies to Eradicate Corruption in Africa Land Sector. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2020, 3, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhardiman, D.; Kenney-Lazar, M.; Meinzen-Dick, R. The contested terrain of land governance reform in Myanmar. Crit. Asian Stud. 2019, 51, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Environmental and Social Framework; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 121. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/383011492423734099/pdf/114278-WP-REVISED-PUBLIC-Environmental-and-Social-Framework.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Kermanshachi, S.; Rouhanizadeh, B.; Dao, B. Application of Delphi Method in Identifying, Ranking, and Weighting Project Complexity Indicators for Construction Projects. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2020, 12, 04519033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-K.; Tsai, S.-C.; Lin, P.-C.; Chu, K.-C.; Chen, A.N. Toward a New Real-Time Approach for Group Consensus: A Usability Analysis of Synchronous Delphi System. Group Decis. Amp Negot. 2020, 29, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodyakov, D.; Grant, S.; Kroger, J.; Bauman, M. RAND Methodological Guidance for Conducting and Critically Appraising Delphi Panels. 2023. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TLA3082-1.html (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- de Loë, R.C.; Melnychuk, N.; Murray, D.; Plummer, R. Advancing the State of Policy Delphi Practice: A Systematic Review Evaluating Methodological Evolution, Innovation, and Opportunities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackham, A. Emerging Options for Extending Working Lives: Results of a Delphi Study in Challenges of Active Ageing: Equality Law the Workplace; Manfredi, S., Vickers, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger, S.M.; Housner, L.D. Modified Delphi Investigation of Exercise Science in Physical Education Teacher Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2007, 26, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Gracht, H.A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayens, M.K.; Hahn, E.J. Building Consensus Using the Policy Delphi Method. Policy Politics Amp Nurs. Pract. 2000, 1, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, J.; Mejía Acosta, A. Power Above and Below the Waterline: Bridging Political Economy and Power Analysis. IDS Bull. 2014, 45, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, H.; Rao, S. Political and Social Analysis for Development Policy and Practice: An Overview of Five Approaches; Governance and Social Development resource Centre: Birmingham, UK, 2010; Available online: https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/EIRS10.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Czembrowski, P.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Kronenberg, J.; Engström, G.; Andersson, E.; Lenormand, M. Valuing individual characteristics and the multifunctionality of urban green spaces: The integration of sociotope mapping and hedonic pricing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, C.M.; Woolcock, M. The World Bank Legal Review; Volume 2: Law, Equity, and Development, The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/441771468336048667/pdf/568260PUB0REPL1INAL0PROOF0FULL0TEXT.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Pradhan, R. Legal Pluralism and Dynamic Property Rights. 2002. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/e1b794c8-b037-4efa-91ba-d009a9884570/content (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Hurwitz, L. Contemporary Approaches to Political Stability. Comp. Politics 1973, 5, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Round | Participants | Response Rate | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | 65% | 1 November to 24 December 2024 |

| 2 | 15 | 75% | 24 February to 25 March 2025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burns, A.F.; Rajabifard, A.; Shojaei, D. Impact of Political Economy on Land Administration Reform. Land 2025, 14, 1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091888

Burns AF, Rajabifard A, Shojaei D. Impact of Political Economy on Land Administration Reform. Land. 2025; 14(9):1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091888

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurns, Anthony Francis, Abbas Rajabifard, and Davood Shojaei. 2025. "Impact of Political Economy on Land Administration Reform" Land 14, no. 9: 1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091888

APA StyleBurns, A. F., Rajabifard, A., & Shojaei, D. (2025). Impact of Political Economy on Land Administration Reform. Land, 14(9), 1888. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091888