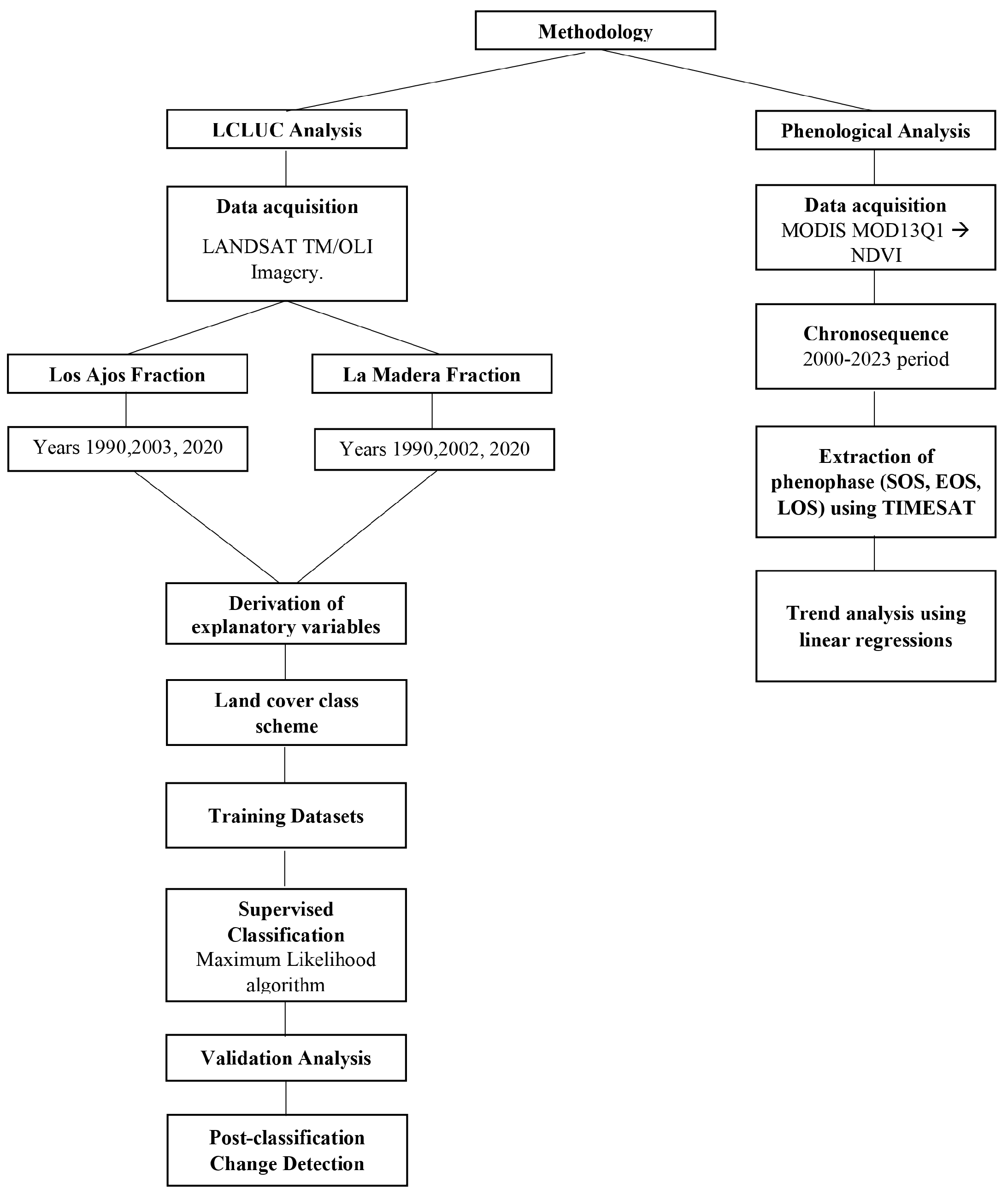

3.1. Land Cover Changes

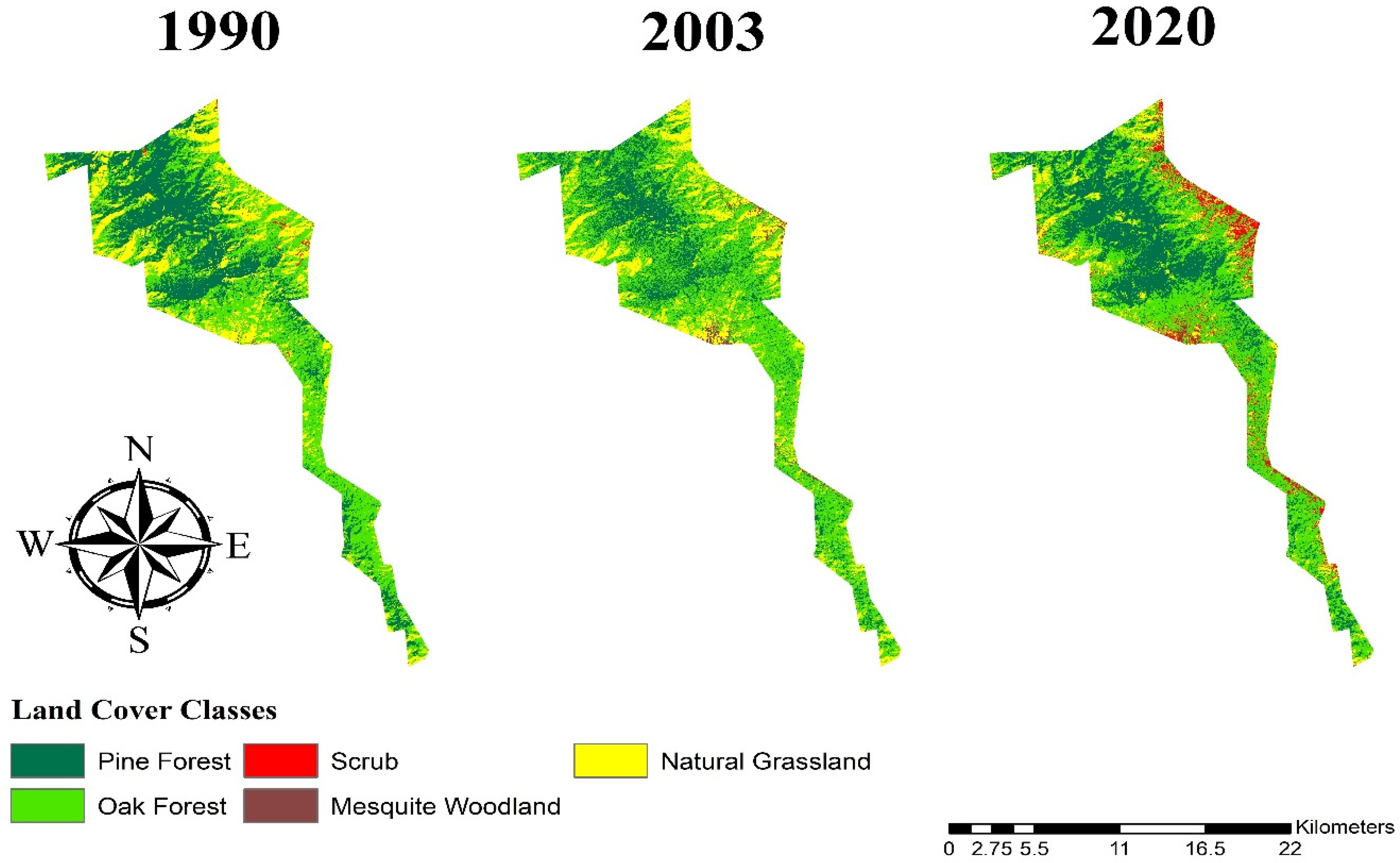

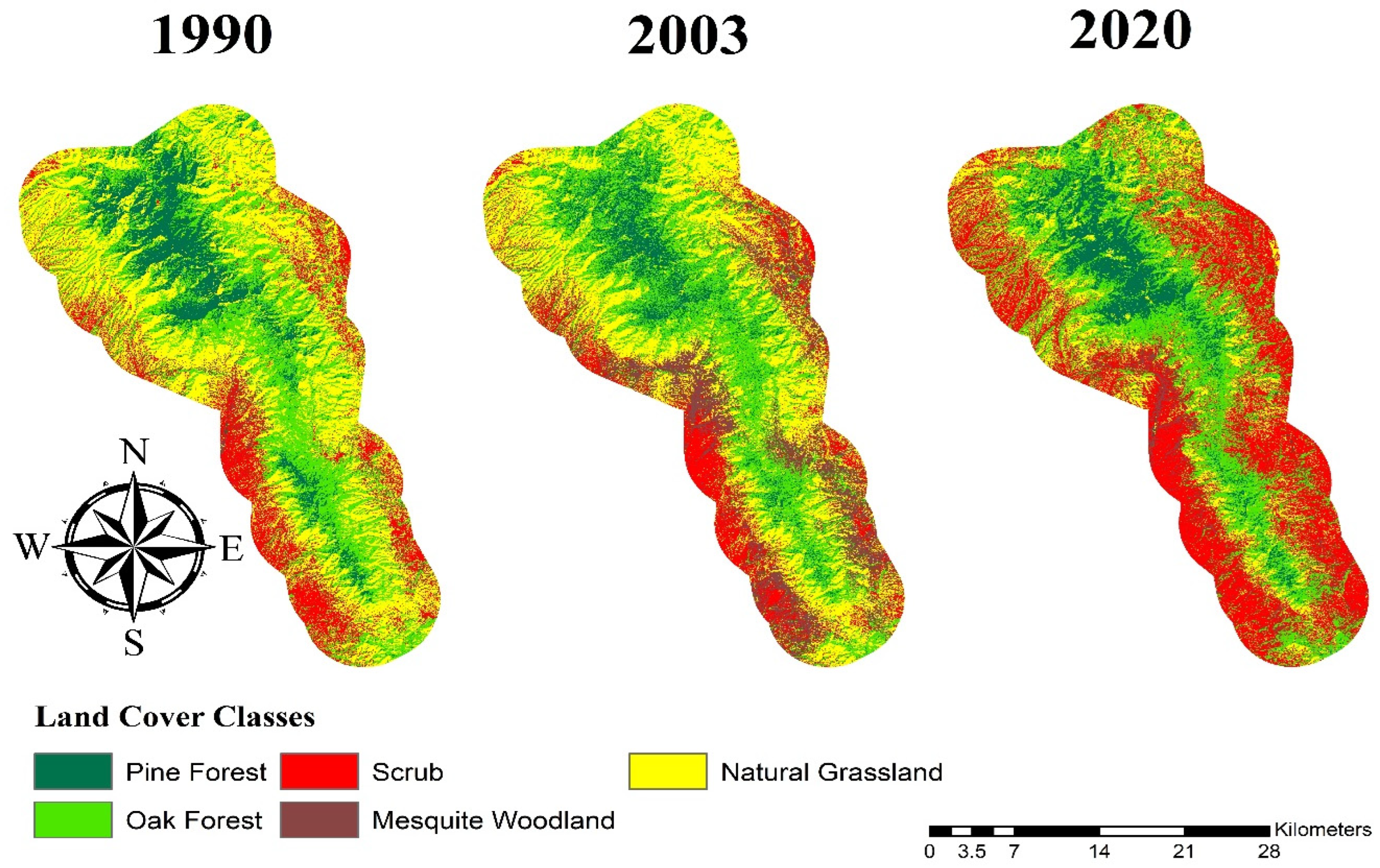

Land cover maps were generated for the years 1990, 2003, and 2020 for the Los Ajos fraction (

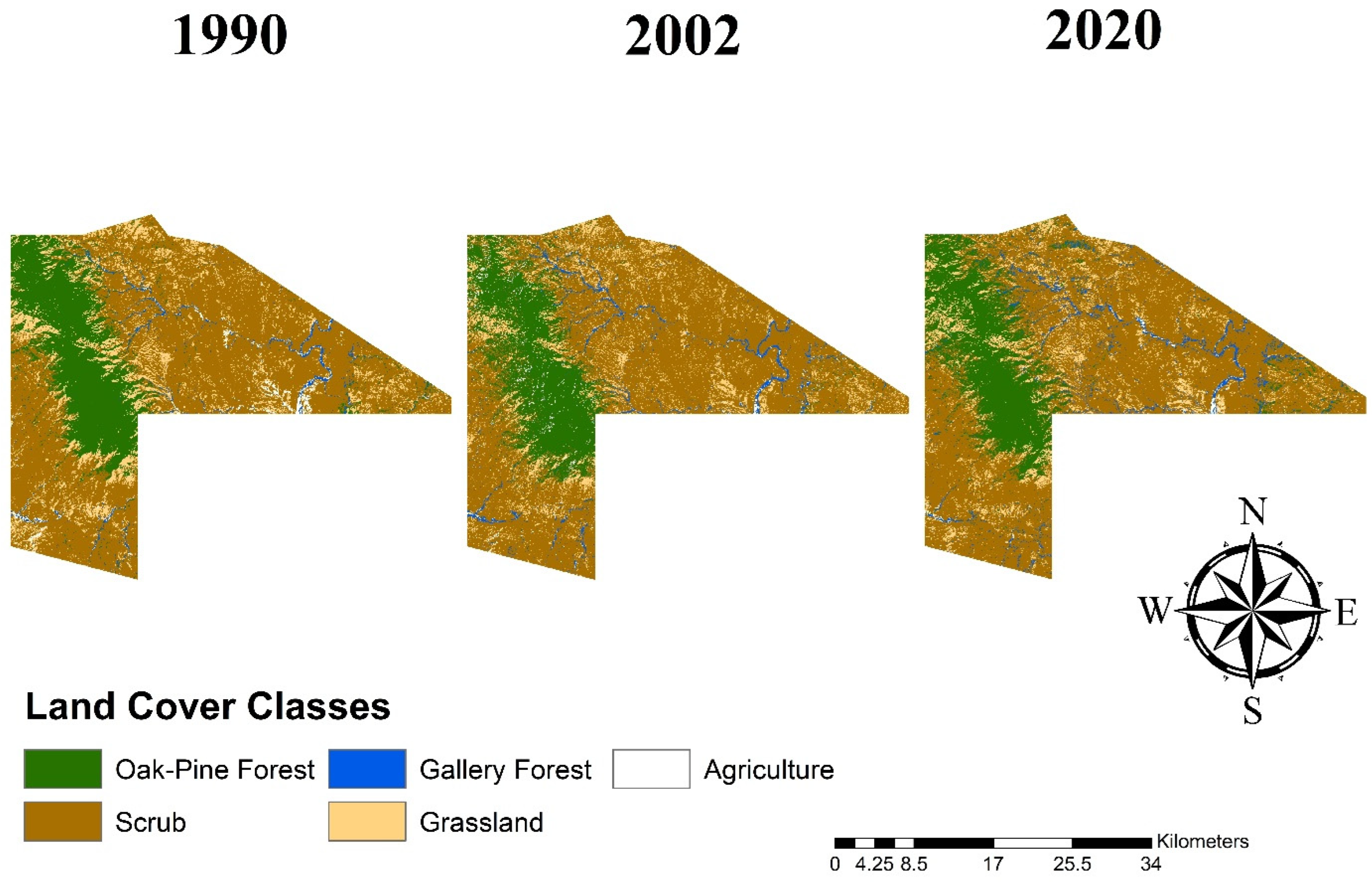

Figure 3). Similarly, land cover maps were produced for the years 1990, 2002, and 2020 for the La Madera sector (

Figure 4). Post-classification accuracy assessments indicated overall classification accuracies ranging from 83% to 92%, with Kappa coefficients between 0.79 and 0.90 (

Table 3 and

Table 4). According to established criteria, such as those proposed by Landis and Koch [

50], these values are considered acceptable given the spatial and temporal resolution of the satellite sensors employed.

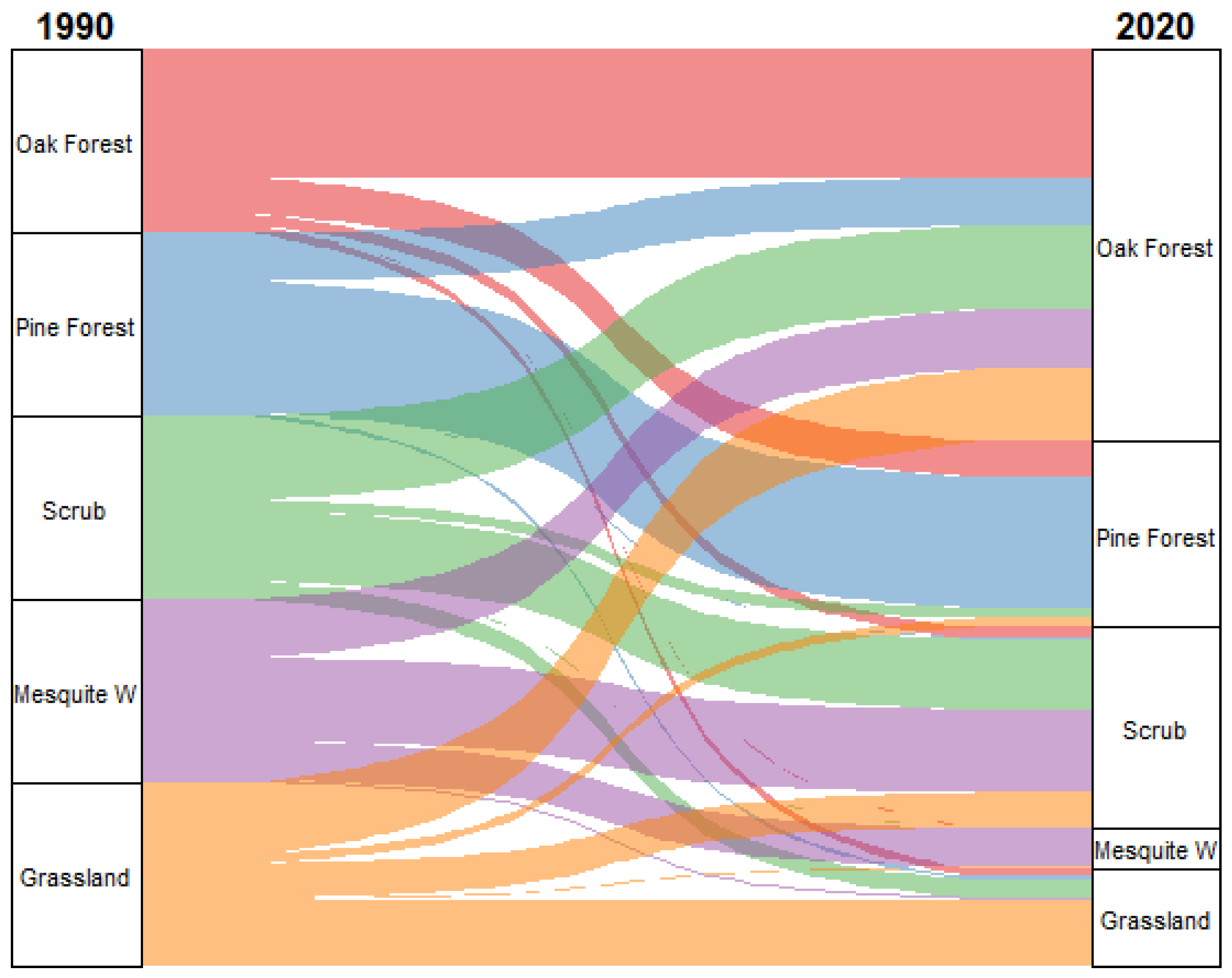

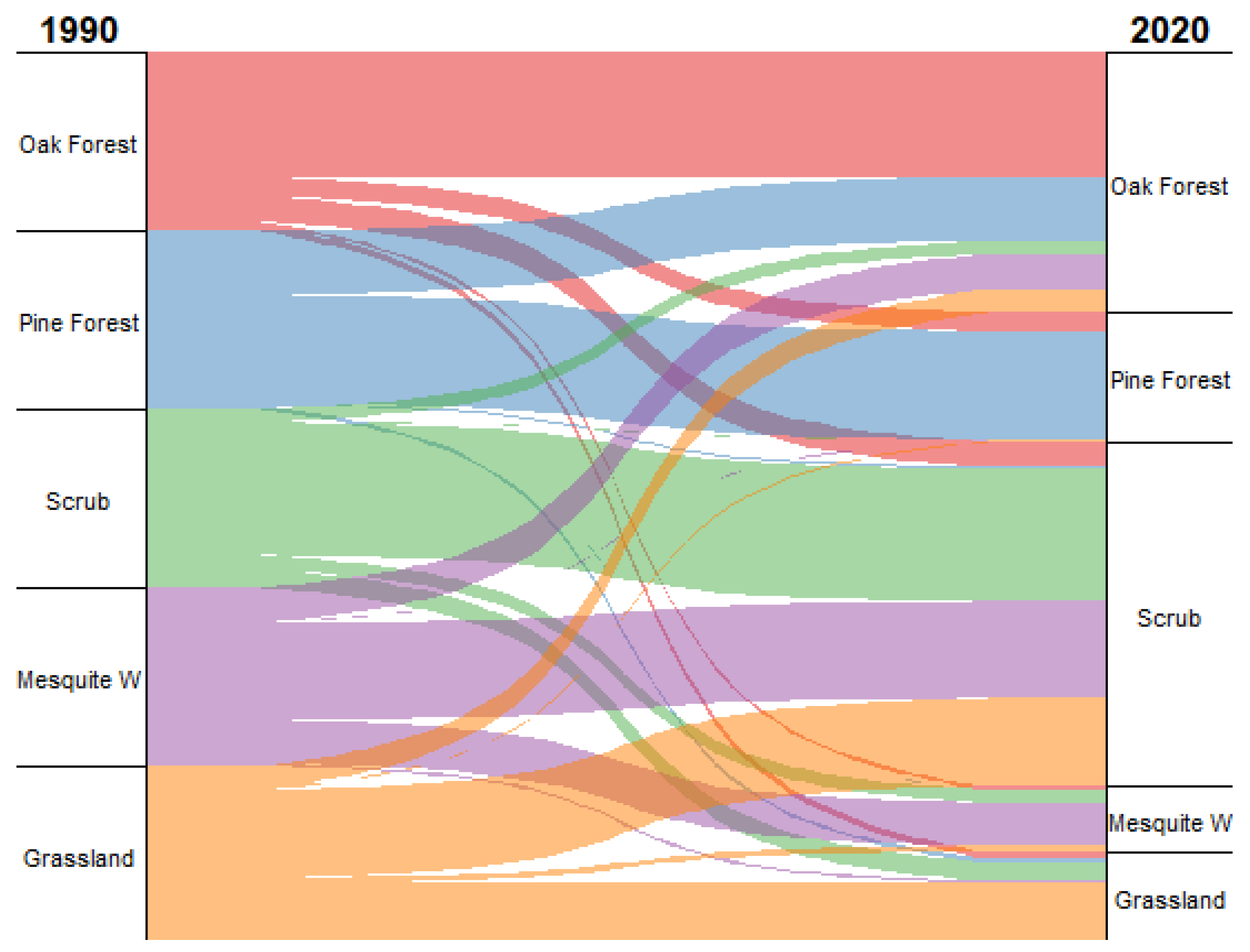

The results of this study indicate that between 1990 and 2020, the Los Ajos sector experienced a reduction of 81.41 hectares of pine forest, decreasing from 7033.14 ha in 1990 to 6947.73 ha in 2020. This change represents a loss of −1.214% relative to the original extent of this land cover type. In contrast, oak forest showed a notable expansion, increasing by 960.57 ha over the same period, from 8702.46 ha to 9663.03 ha, equivalent to an 11.03% increase from its initial area. Scrub exhibited the most dramatic transformation, expanding by 1322.64 ha, from just 101.34 ha in 1990 to 1423.98 ha in 2020, corresponding to a 1305.151% increase. Similarly, mesquite woodland experienced a substantial gain of 41.85 ha, growing from 101.34 ha to 1424.98 ha, which represents a 153.97% increase. Natural grassland, on the other hand, showed the most significant loss in spatial extent, with a reduction of 2239.65 ha, decreasing from 4261.41 ha in 1990 to only 2021.76 ha in 2020. This constitutes a −52.55% decline relative to its original area (

Table 5). Changes and their magnitudes between land cover classes can also be observed (

Figure 5).

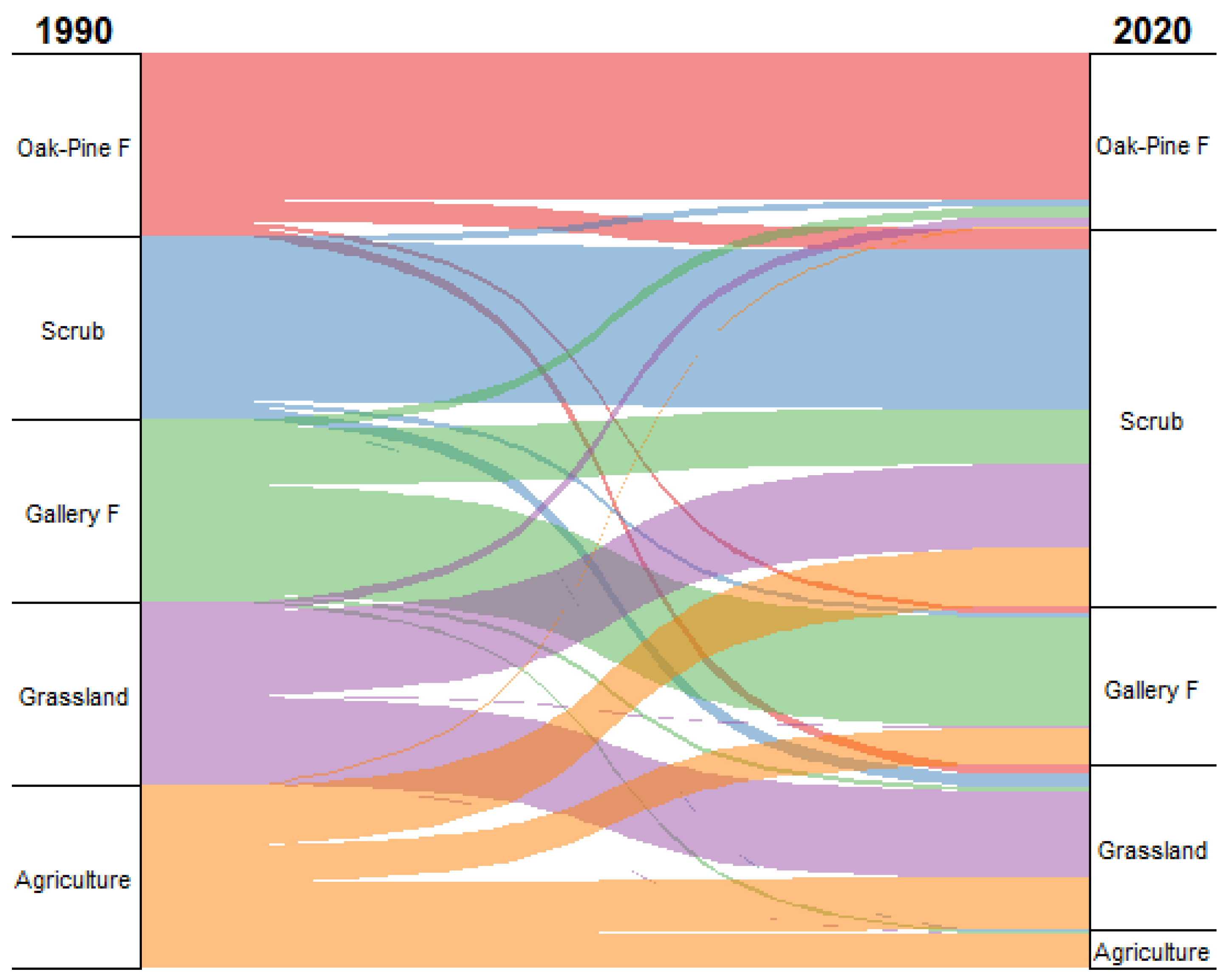

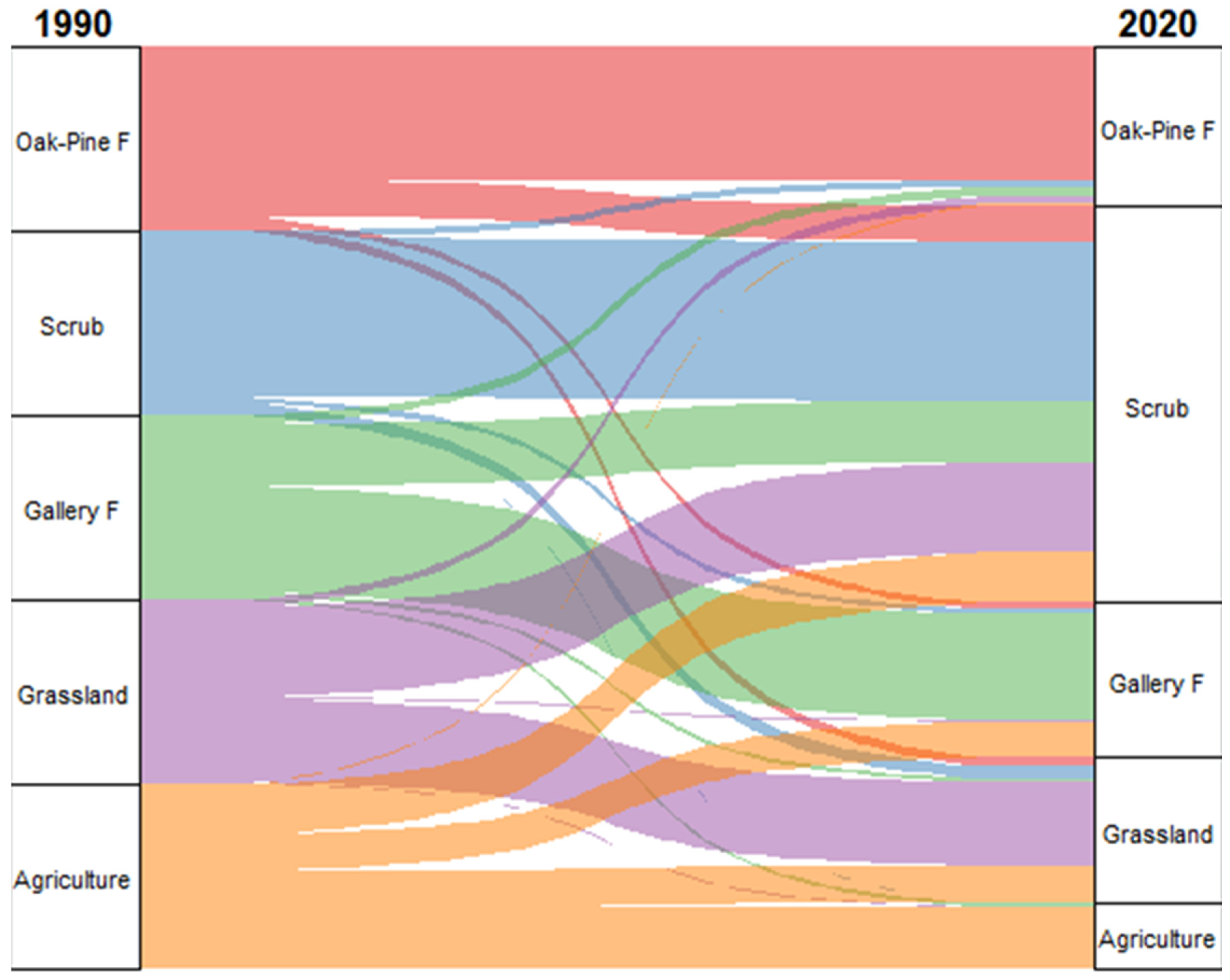

In the case of the La Madera sector, between 1990 and 2020, scrub remained the dominant land cover type, increasing by 1420.74 hectares, from 61,335.36 ha to 62,756.10 ha, representing a 2.316% expansion. Gallery forest also showed a significant increase, growing from 1603.89 ha to 3457.35 ha, which corresponds to a net gain of 1853.46 hectares or 115.56%. Oak-Pine Forest experienced a reduction of 852.84 hectares, decreasing from 19,638.81 ha to 18,785.97 ha, equivalent to a −4.343% loss in surface area. Grassland also declined, losing 1486.98 hectares, from 13,542.75 ha to 12,055.77 ha, corresponding to a −10.980% decrease, likely associated with the expansion of scrub. Finally, agricultural land showed a pronounced reduction of 934.38 hectares, dropping from 1374.30 ha to 439.92 ha, representing a −67.99% decrease from its original extent (

Table 6). Changes and their magnitudes between land cover classes can also be observed (

Figure 6).

Similarly, the same procedure was conducted using a 5 km buffer zone for both the Los Ajos sector (

Figure 7) and the La Madera sector (

Figure 8) in order to assess whether patterns observed within the core area were consistent in the surrounding landscape.

When considering the 5 km buffer zone around the Los Ajos fraction, the land cover change analysis (

Table 7) shows that natural grassland experienced the most substantial loss in spatial extent, with a decrease of 19,909.53 hectares between 1990 and 2020, representing a −59.17% reduction from its initial coverage. In contrast, scrubland underwent a significant expansion, gaining 18,629.10 hectares, which corresponds to a 161.815% increase relative to its original area. Oak forest also expanded, increasing by 2331.09 hectares, from 24,136.65 ha to 26,467.74 ha, equivalent to a 9.658% increase. Conversely, pine forest decreased by 1378.98 hectares, from 10,796.13 ha to 9417.15 ha, representing a −12.77% loss in surface area. Finally, mesquite woodland showed a moderate increase of 328.32 hectares, from 2696.49 ha to 3024.81 ha, which constitutes a 12.17% increase in its extent. Changes and their magnitudes between land cover around the 5 km buffer classes can also be observed (

Figure 9).

In the 5 km buffer zone surrounding the La Madera sector (

Table 8), a notable expansion of scrub was observed, with an increase of 7493.04 hectares, from 114,490.26 ha in 1990 to 121,983.30 ha in 2020, representing a 6.545% increase in its original extent. Gallery forest also experienced a substantial gain, increasing by 4208.67 hectares, from 3157.47 ha to 7366.14 ha, which corresponds to a 133.292% rise in surface area. Oak-Pine Forest showed a reduction of 1980.81 hectares, declining from 28,220.67 ha to 26,239.86 ha, equivalent to a −7.019% decrease. Grassland also underwent a significant reduction, losing 7167.06 hectares, from 30,989.97 ha to 23,822.91 ha, which constitutes a −23.127% decrease. Lastly, agricultural land use experienced a sharp decline of 2553.84 hectares, decreasing from 4633.29 ha to 2079.45 ha, amounting to a −55.119% reduction in its initial area. Changes and their magnitudes between land cover around the 5 km buffer classes can also be observed (

Figure 10).

The results of the present study reveal significant transformations that occurred in just 30 years. In the Los Ajos section, scrubland cover increased by 1322.64 ha (a 1305.15% relative change) within the reserve boundary and by 18,629.10 ha (a 161.82% relative change) in the 5 km buffer zone, while oak forest cover increased by 960.57 ha (a 11.03% relative change) within the reserve limits and by 2331.09 ha (a 9.65% relative change) in the buffer area. In contrast, in the La Madera section, scrubland increased by 1420.74 ha (a 2.31% relative change) within the protected area and 7493.04 ha (a 6.54% relative change) in its surrounding buffer. While grasslands decreased significantly by 2239.65 ha (a −52.55% relative change) and 19,909.53 ha (a −59.17% relative change) in Los Ajos, and by 1486.98 ha (a −10.98% relative change) in the reserve and 7167.06 ha (a −23.12% relative change) in the buffer zone. This marked difference is mainly explained by the initial conditions of each area and their distinct topographic characteristics. While Los Ajos was originally dominated by typical mountain communities such as grasslands, pine forests, and oak woodlands, La Madera was already largely covered by scrubland. Therefore, woody vegetation expansion was more intense in areas previously occupied by vegetation types more susceptible to replacement.

Our results are consistent with previous studies conducted in ecologically similar sites, where the expansion of woody species into ecosystems formerly dominated by grasses has been reported [

49,

61]. In North America, the rates of woody vegetation expansion vary across ecoregions, ranging from 0.1% to 2.3% cover per year [

8]. Specifically, in the Great Plains region, an annual increase of 1–2% in woody species cover has been documented [

2]. In particular, the progressive degradation of grasslands in the Madrean Archipelago, where the present study site is located, has been widely documented [

62,

63]. Recent estimates indicate that approximately 3.5 million hectares (84.1%) of the historical grasslands in the Arizona and New Mexico portion of the Apache Highlands Ecoregion have already undergone varying degrees of woody encroachment [

53].

On the other hand, the results show that both within the boundaries of the Los Ajos sector and in the surrounding 5 km buffer zone, there was a reduction in pine forest cover and a concurrent expansion of oak forest. This pattern has also been noted in previous studies [

64,

65,

66], including in nearby regions such as the Sky Islands of Arizona [

67]. According to Alfaro-Reyna et al. [

65], temperate forests have undergone rapid changes in recent decades, with a directional increase in the abundance of Fagaceae species at the expense of Pinaceae. This trend has been primarily attributed to rising temperatures and the prolongation of drought periods. Pinaceae species are adapted to cold climates due to the anatomy of their wood (narrow-diameter xylem resistant to freeze–thaw cycles), as well as their leaf morphology and photosynthetic physiology. In contrast, many Fagaceae species are better suited to warmer conditions and exhibit less strict stomatal control, allowing them to sustain high transpiration rates during droughts [

54]. Moreover, the replacement of pine-dominated forests by oak shrublands and grasslands has been documented following several high-severity wildfires over the past two decades [

67,

68,

69].

In contrast to what is commonly observed in arid and semi-arid landscapes, where water bodies and their associated vegetation typically diminish due to human or climatic pressures, a significant expansion of gallery vegetation was documented in the La Madera region during the analyzed period. According to Huang et al. [

70], intermittent drainages (arroyos) receive precipitation inputs in the form of runoff from neighboring and upslope areas. These precipitation inputs render arroyo environments more mesic than other landforms, enabling greater scrub cover and biomass.

Developing metrics to assess parameters measured or address conservation effectiveness, using remote sensing tools, has the potential to greatly improve management decisions. Most likely, these metrics would reflect the progression of land cover and vegetation response to state variables [

71]. The current study explores the development of these tools by addressing vegetation processes (timing vegetation response) as a consequence of cover change.

Future research regarding land cover distribution in remote PNA sites might benefit from higher spatial resolution datasets to address shifts in recent decades. However, historical reconstructions using these datasets might be challenging since imagery legacies might cover a considerably shorter timespan than the Landsat missions. On the same note, it would be desirable to build up location datasets (basic georeferenced records) for land cover class presence over time in order to develop a robust training dataset for supervised classifications.

3.2. Changes in Phenology

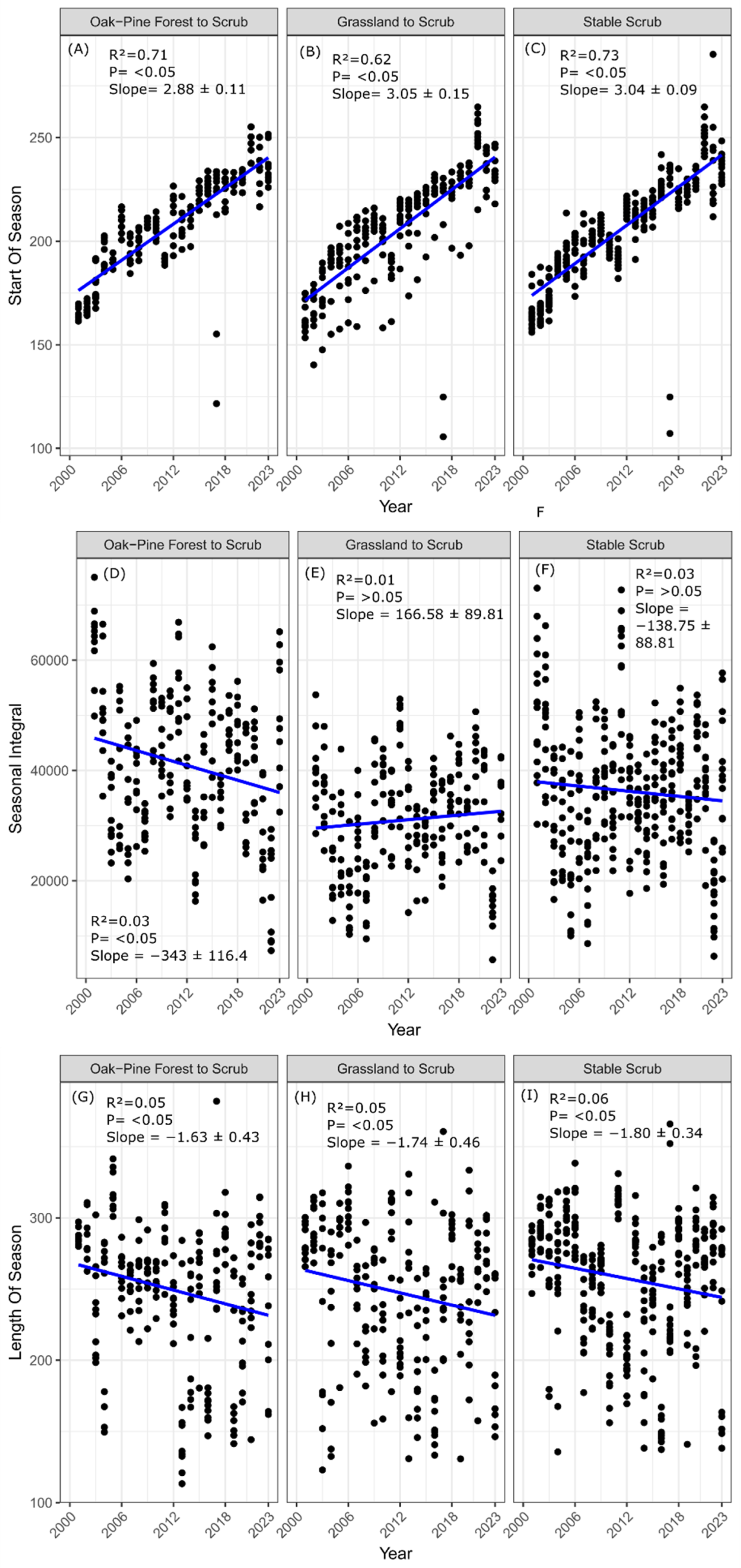

We analyzed 24 years of trends (from 2000 to 2023) of key phenophases for study sites where woody vegetation substituted other land cover types. Specifically, we observed the length and start of the season and the seasonal minor integral for the three selected land cover types in the Los Ajos and La Madera fraction. Regarding the start of the season (SOS), our analysis suggests that in the Los Ajos area (

Figure 11), the transition from Oak to Scrub (

Figure 11A) exhibited a significant delay in the start of the season, with an average increase of 2.37 days per year (R

2 = 0.5791,

p < 0.001). In the transition from Grassland to Scrub (

Figure 11B), the delay was even more pronounced, with an increase of 2.66 days per year (R

2 = 0.6002,

p < 0.001). Finally, stable scrublands (

Figure 11C) also showed a delay in the start of the season, with an increase of 2.61 days per year, although with a lower explanatory power (R

2 = 0.3087,

p < 0.001). Similarly to Los Ajos, La Madera also shows a significant delay in the start of the season for all three transition types (

Figure 12). Oak-Pine to Scrub transitions (

Figure 12A) suggests a delay of 2.89 days per year at SOS (R

2 = 0.7198,

p < 0.001). The transition from Grassland to Scrub (

Figure 12B) showed the greatest delay, with an increase of 3.06 days per year (R

2 = 0.6246,

p < 0.001). Finally, Stable Scrub (

Figure 12C) shows a delay of approximately 3.04 days per year (R

2 = 0.7336,

p < 0.001).

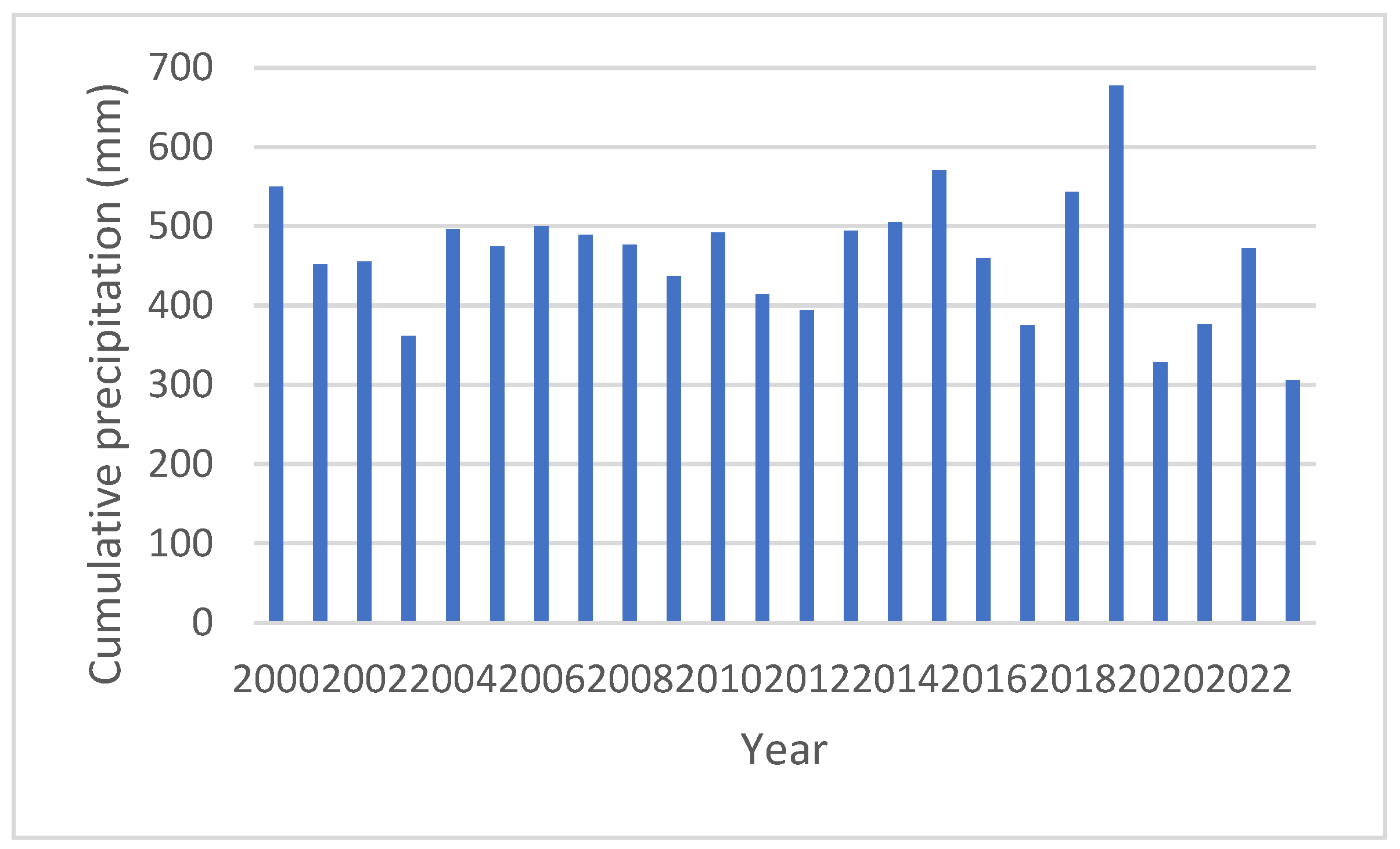

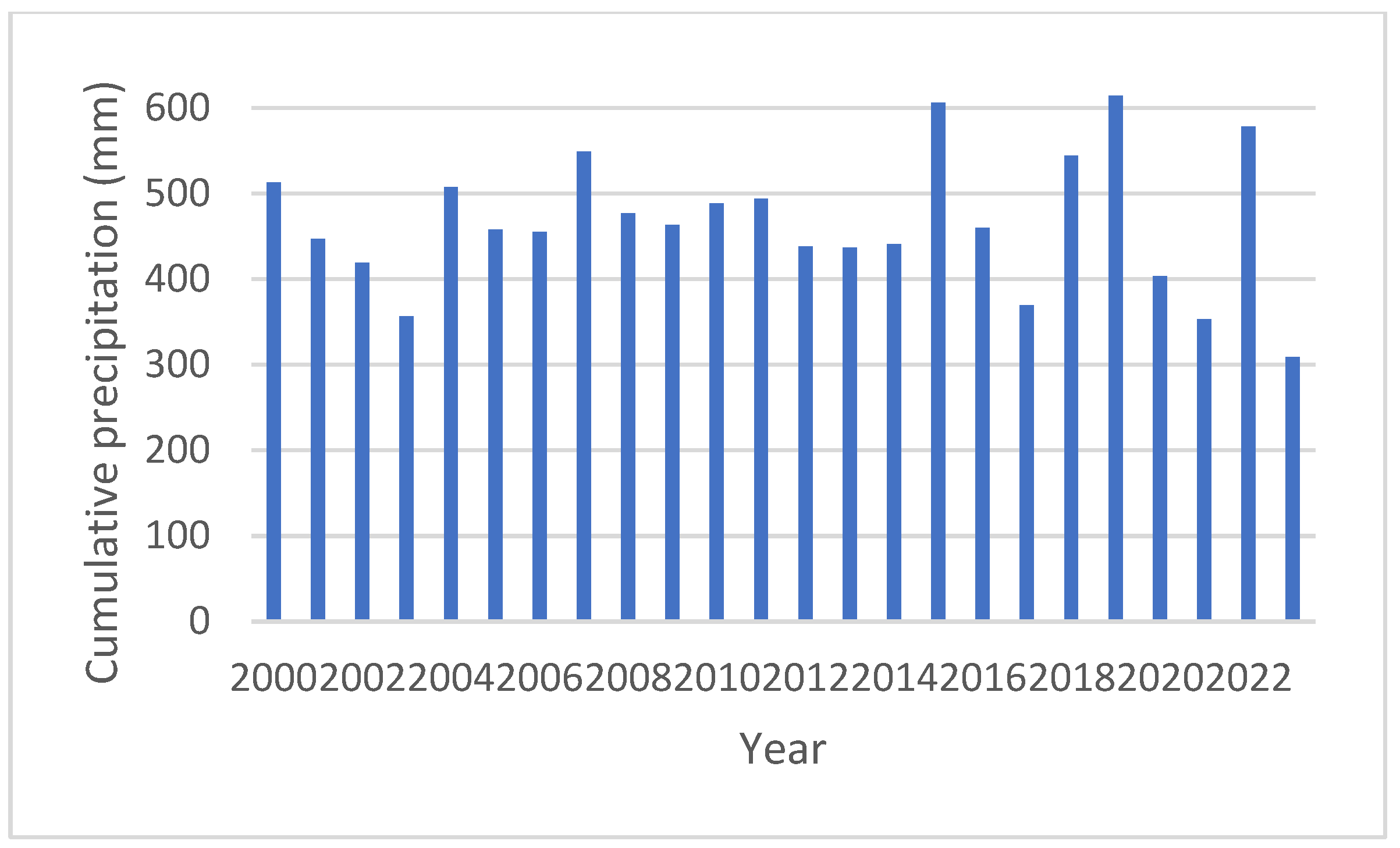

One of the most significant findings of this study is observed in the phenophase of the SOS. It was significantly later in both the Los Ajos and La Madera fractions, a pattern that has also been observed in regions of North America [

72]. Estimates of the SOS are often linked to the timing and intensity of precipitation (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14), making their detection highly sensitive to atmospheric conditions and rapid vegetation responses [

73]. Building on the work of Crimmins et al. [

32], an increase of between 2 and 6 °C in temperatures is projected for the arid southwestern United States by the year 2100, accompanied by a decrease in total precipitation, particularly in winter and spring, as well as an increase in the frequency of extreme climatic events such as droughts, heavy rains, and heat waves. Although earlier spring flowering of woody species in lowland areas associated with warming has been documented in the Sonoran Desert, little is yet known about the response of other life forms, especially those inhabiting higher elevations and facing drier conditions. Finally, the authors warn that if autumn rains do not reach the minimum moisture thresholds required to trigger flowering, some species may not flower at all during the following spring, as has been observed in Finger Rock Canyon after particularly dry autumns and winters.

Regarding the length of season (LOS), for the Los Ajos fraction, significant differences were observed across all three land cover categories (

Figure 11). The transition from oak to scrub (

Figure 11G) shows a season length shortened by 2.8 days per year (R

2 = 0.1591,

p < 0.05). In the transition from grassland to scrub (

Figure 11H), the decrease was 1.7 days per year (R

2 = 0.05885,

p < 0.05). Lastly, in stable scrubland (

Figure 11I), the season length decreased by 1.17 days per year (R

2 = 0.02199,

p < 0.05). Similarly to Los Ajos, La Madera also shows significant differences for all the cases analyzed (

Figure 12). In the transition from oak-pine to scrub (

Figure 12G), the season length decreased by 1.6 days per year, (R

2 = 0.05185,

p < 0.05). In the grassland-to-scrub transition (

Figure 12H), the reduction was 1.74 days per year (R

2 = 0.05189,

p < 0.05). Finally, stable scrub (

Figure 12I) exhibited a decrease of 1.80 days per year (R

2 = 0.06924,

p < 0.05).

Regarding the small integral analyses, tightly linked to productivity (

Figure 11D–F and

Figure 12D–F) significant changes were only observed in the transition from oak to scrub in the Los Ajos area (

Figure 11D), where productivity in later years decreased (R

2 = 0.7198,

p < 0.05). In the La Madera area, significant changes were only detected in the transition from oak-pine to scrub (

Figure 12D), where once again productivity declined in later years (R

2 = 0.3116,

p < 0.05). According to [

74], the life cycle of scrubs follows a seasonal time scale, whereas oaks function on an annual time scale. Consequently, the replacement of oak forest by scrubs leads to a decrease in seasonal productivity as the continuous activity associated with oak cover is lost.

The convergence in productivity and season length may be related, according to Crimmins et al. [

32], to the phenological strategies of woody species, which tend to exhibit more synchronized flowering both at the individual and community levels. In contrast to perennial herbaceous species, which respond more opportunistically and asynchronously to rainfall pulses, woody plants display more stable phenological patterns, likely due to their ability to access deeper groundwater sources [

74]. This greater phenological stability could explain the lower interpatch variability observed in certain parameters. Various studies have shown that the effects of shrub encroachment on aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) are complex and context-dependent [

4]. Although declines in productivity have been documented in arid regions, these trends are not universal. For example, the expansion of

Juniperus virginiana into low-elevation grasslands and scrublands in the western United States has been associated with increases in ecosystem net productivity, as well as changes in the distribution and quantity of carbon and nitrogen in both soil and vegetation [

75,

76]. Therefore, the study of complex dynamics regarding transitions to woody vegetation should be addressed at multiple spatiotemporal scales. At the landscape level, the quantification of the increase/decrease in woody vegetation, as well as the changes in ecosystem function posed by it, are key components to analyze encroachment. The current study focuses only on phenological changes as a consequence of woody vegetation transitions. However, given the results reached in this work, a regional assessment of phenological trends could further our understanding of climatic shifts on all land cover types in the region.