Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Hot Springs and Mud Volcanoes and Their Short-Term Seismic Precursor Anomalies Around the Muji Fault Zone, Northeastern Pamir Plateau

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Sampling and Methods

3.1. Collection and Analysis of Geothermal Water Samples

3.2. Collection and Analysis of Geothermal Gas Samples

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Water Chemistry and Water Isotope Characteristics

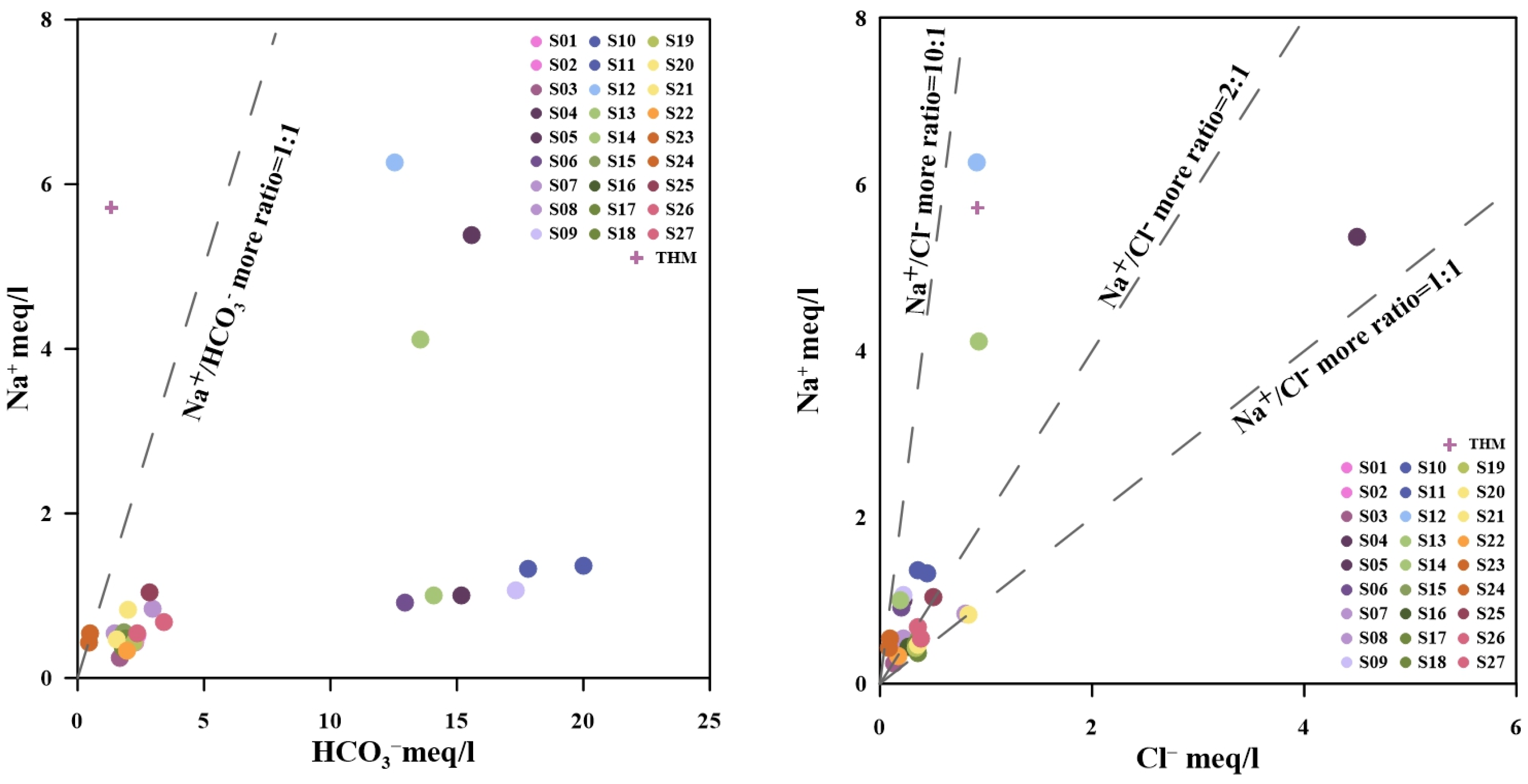

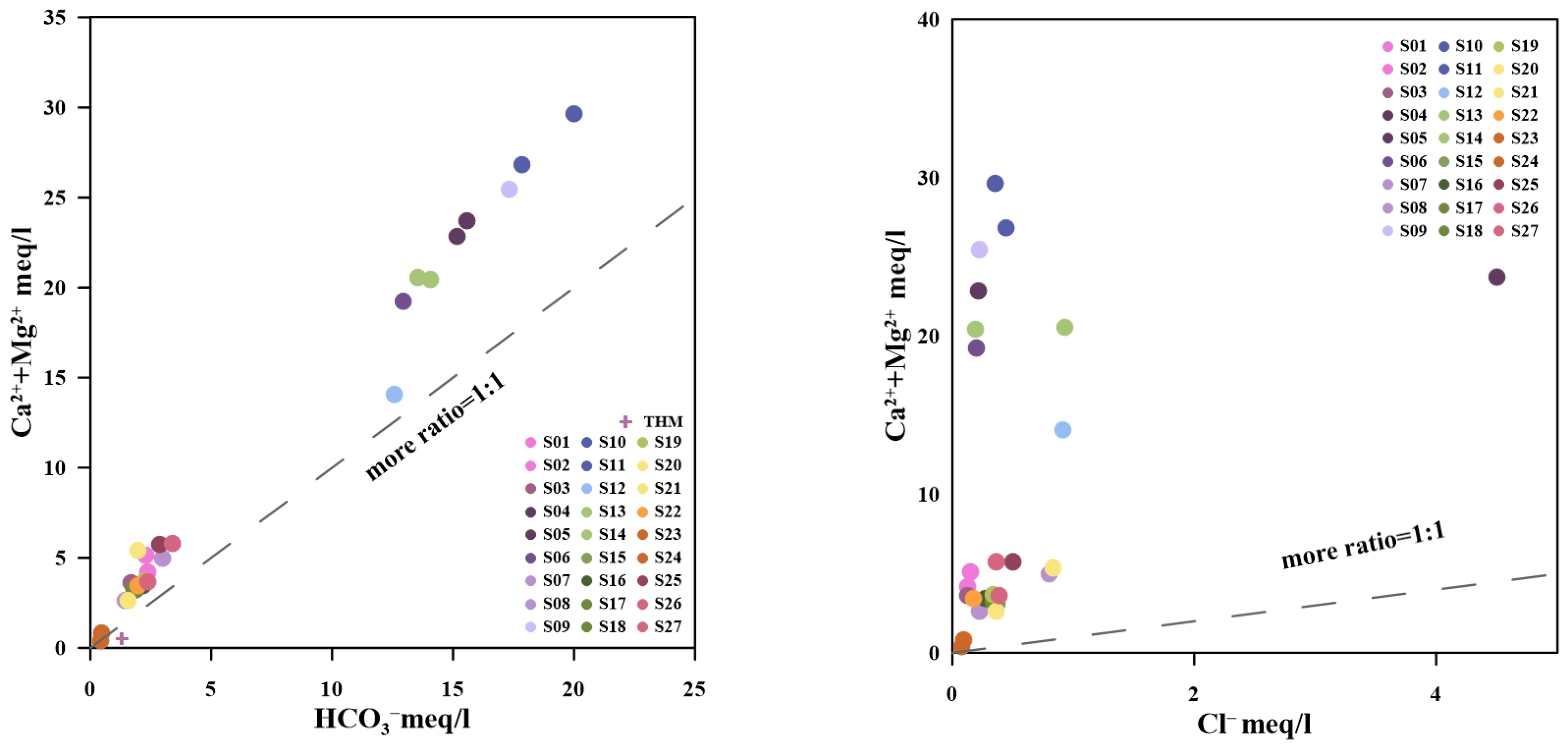

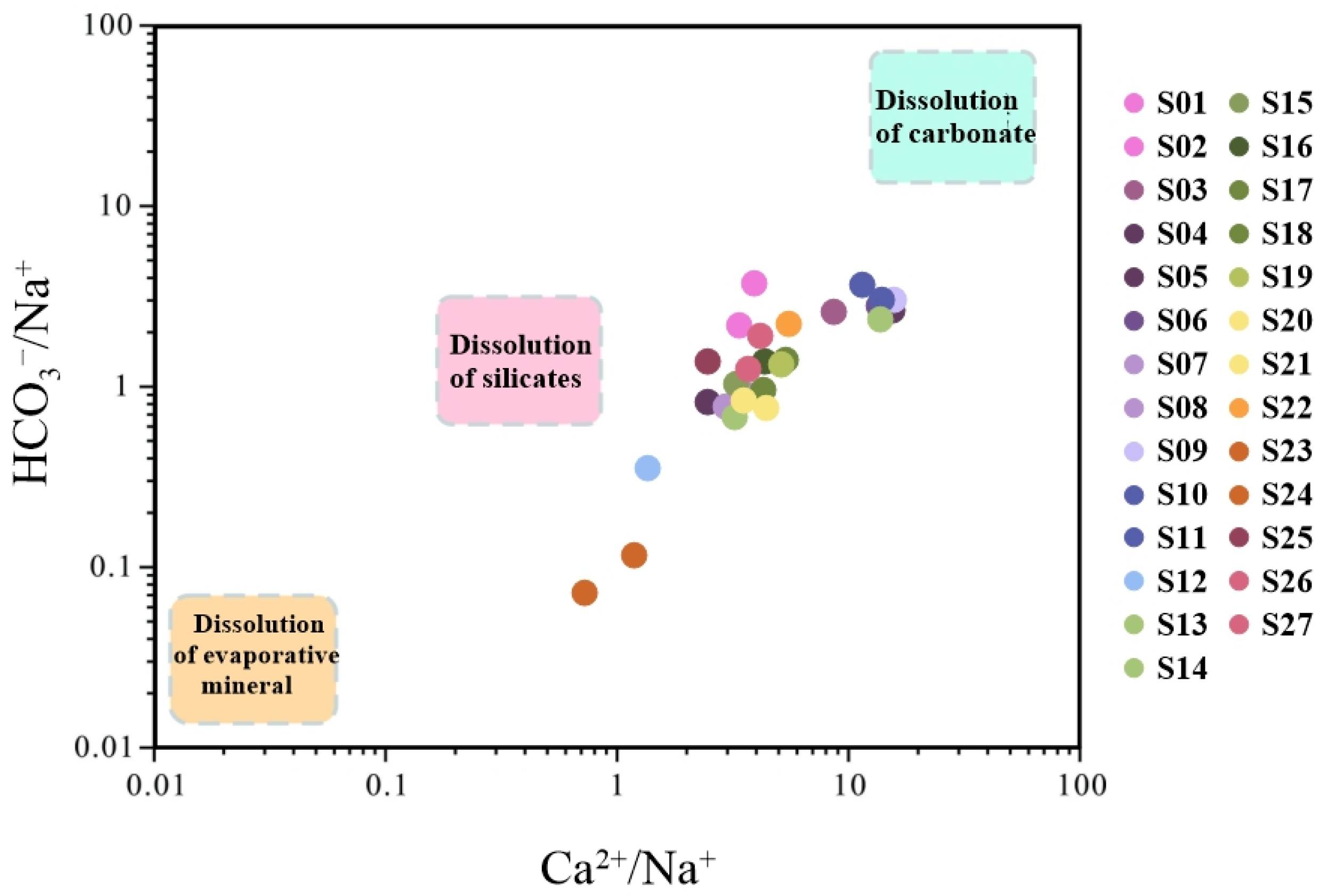

5.1.1. Origin of Major Elements in Hot Springs

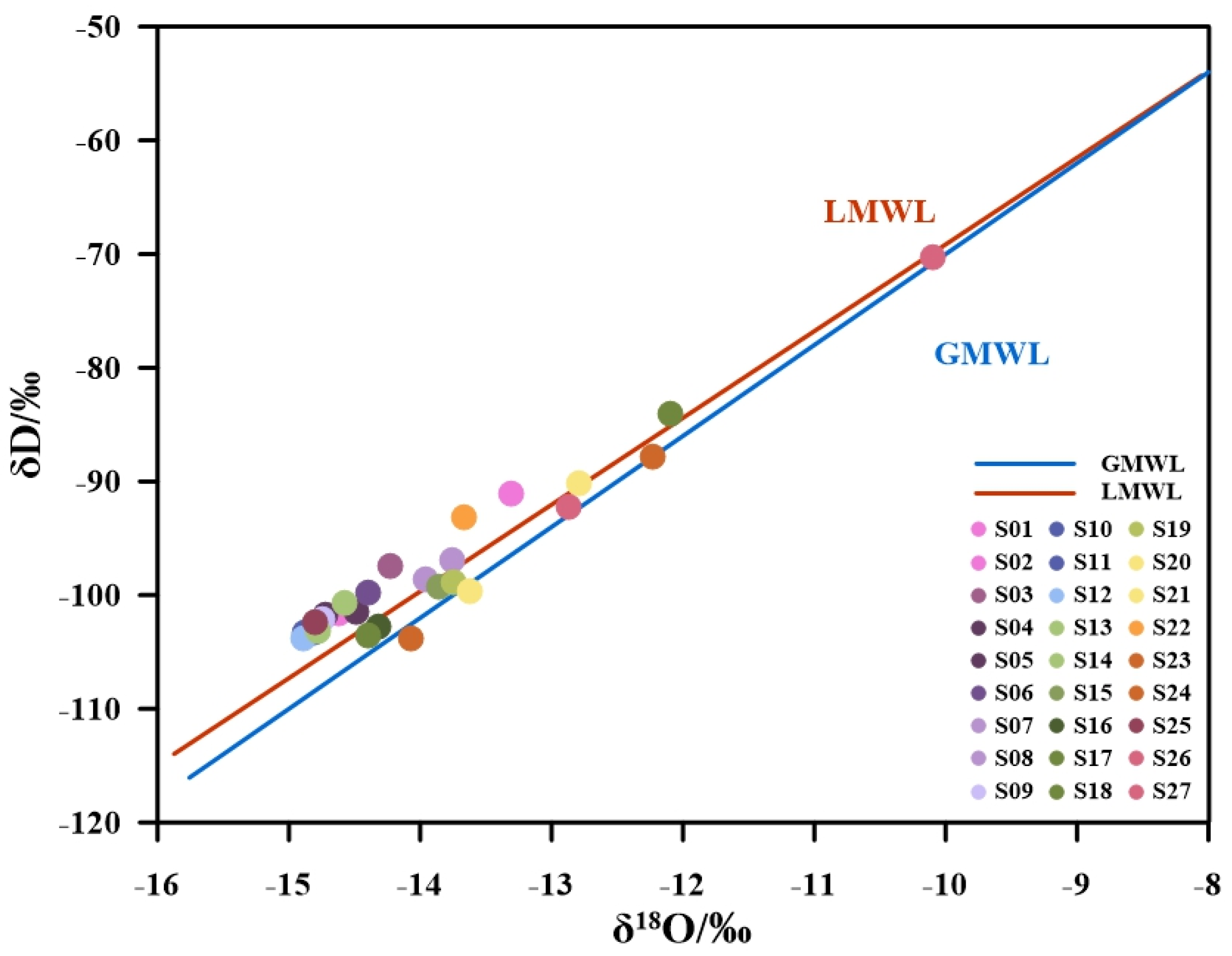

5.1.2. Stable Oxygen and Hydrogen Isotopes

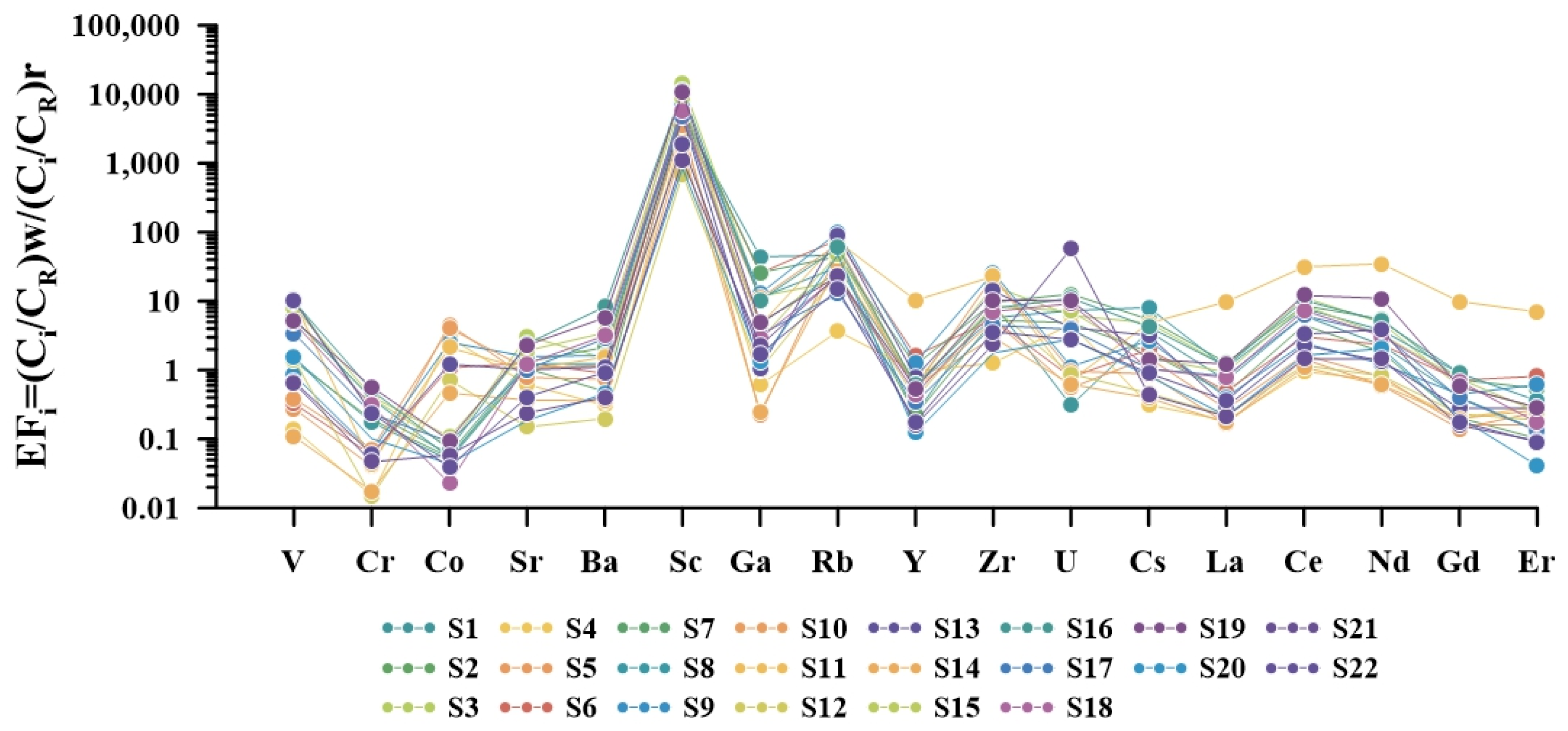

5.1.3. Origin of Trace Elements in Hot Springs

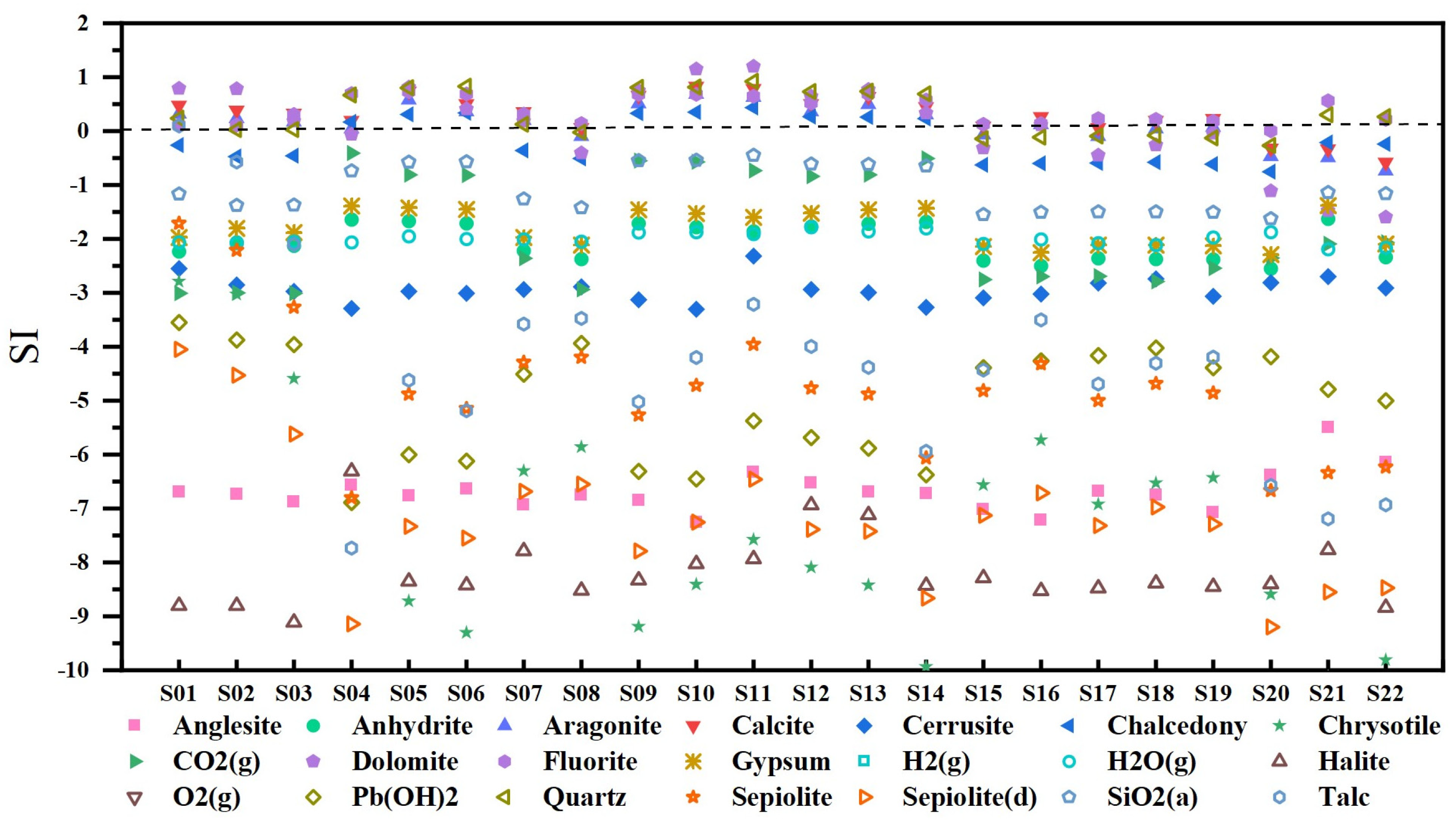

5.1.4. Mineral Saturation States

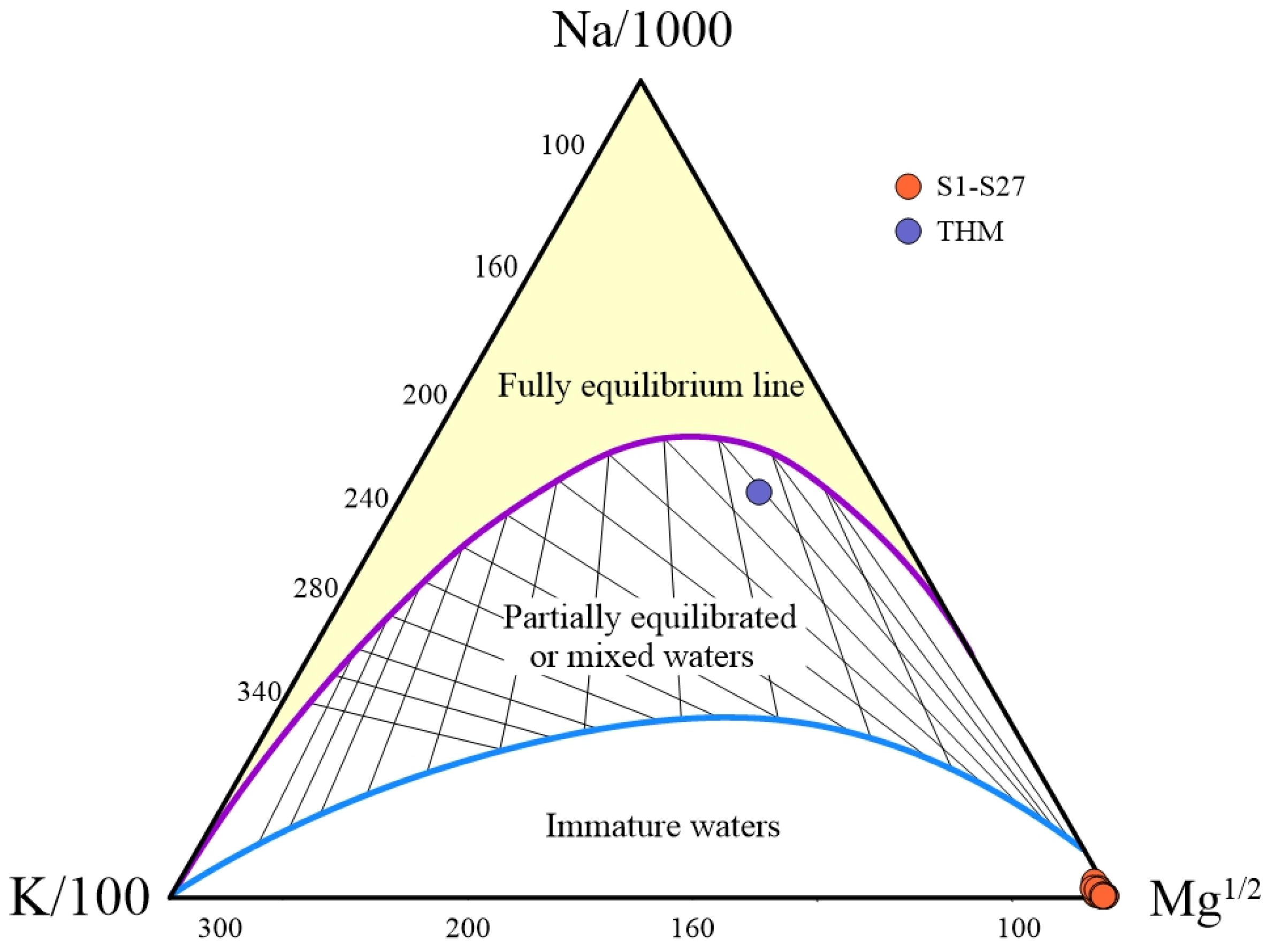

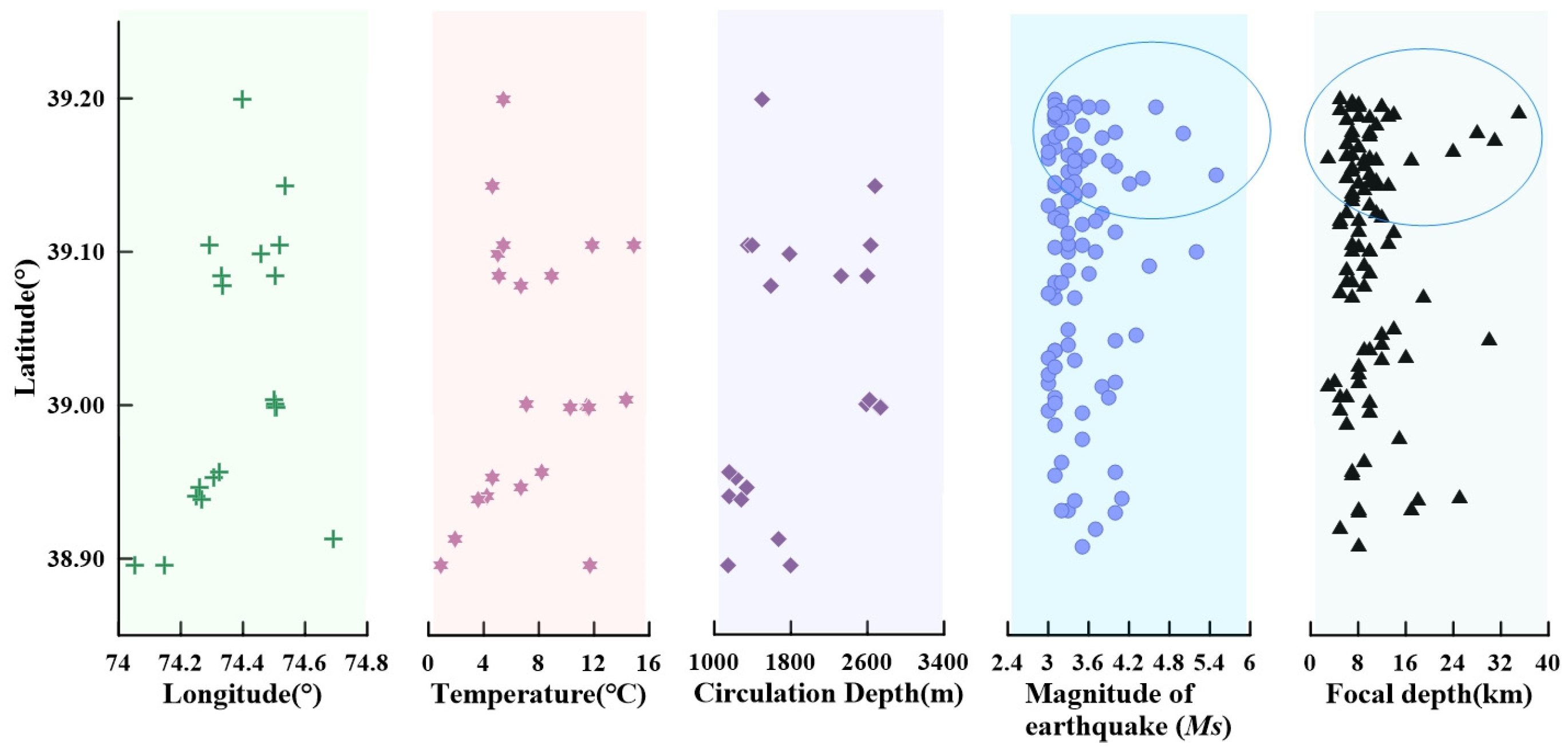

5.2. Reservoir Temperature

5.3. Geochemical Characteristics of Hot Spring Gas

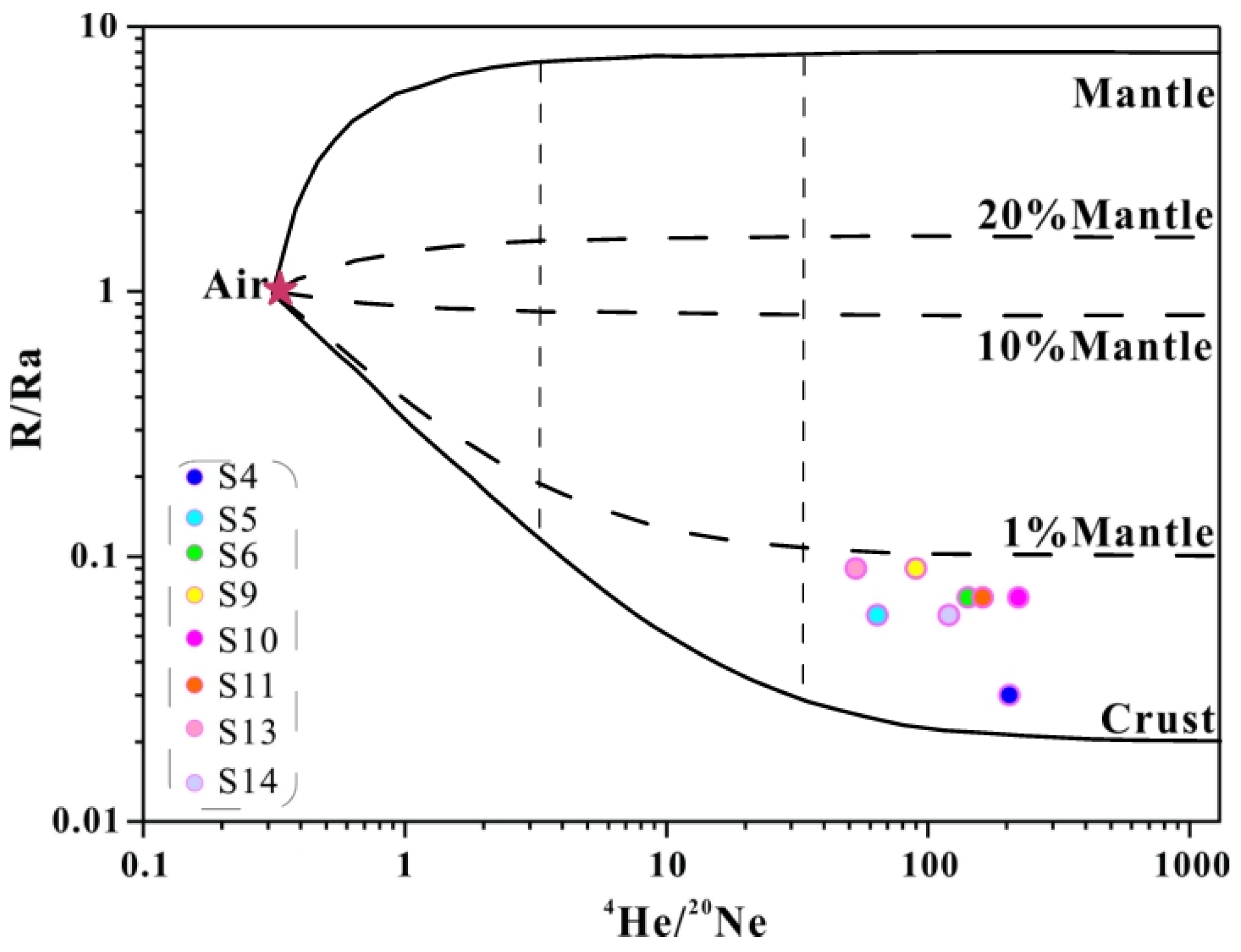

5.3.1. The Source of Helium

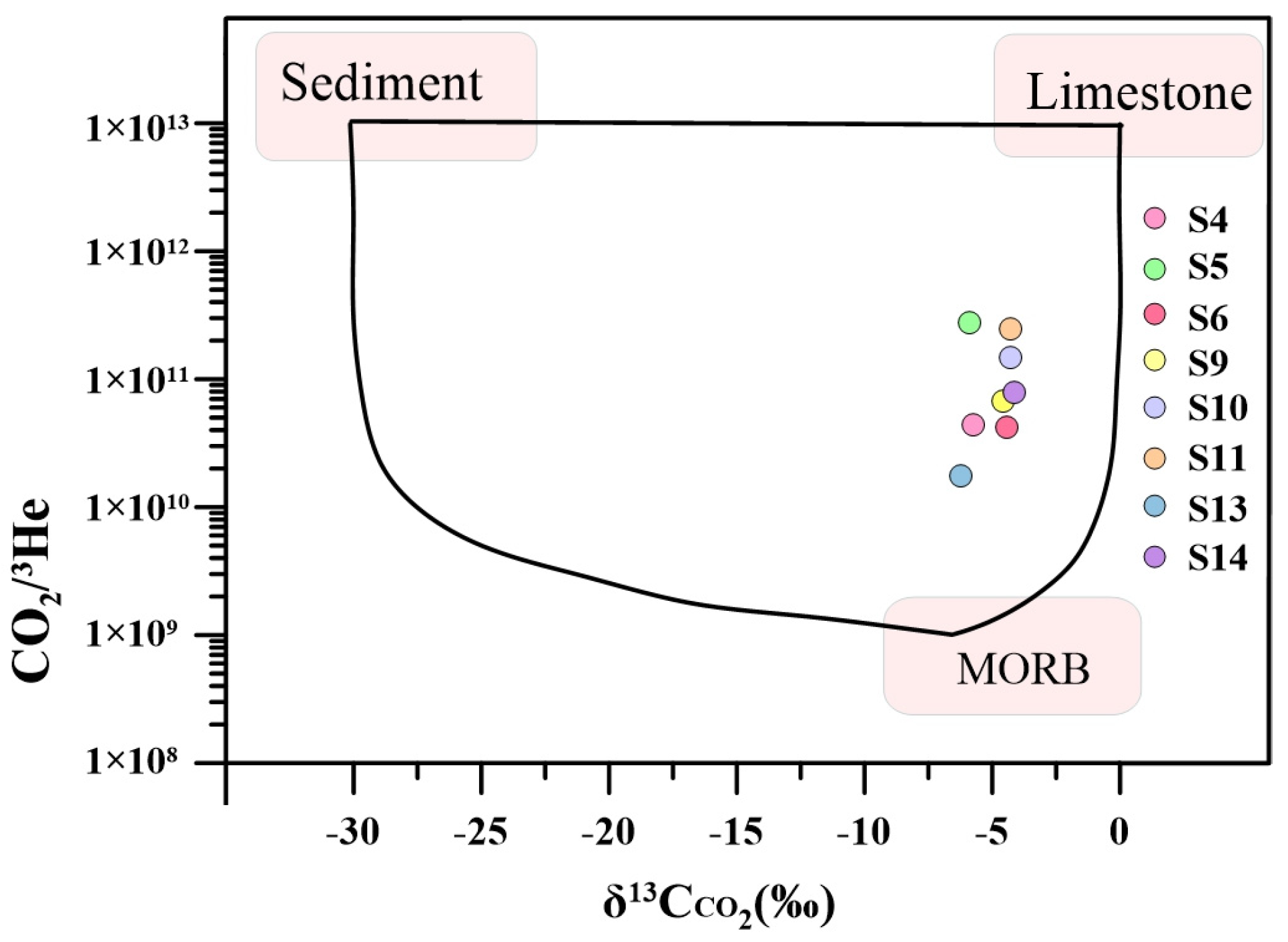

5.3.2. Sources of CO2 Gases

5.4. Hydrogeochemical Response to Tectonic Activity: From Spatial Distribution to Temporal Evolution

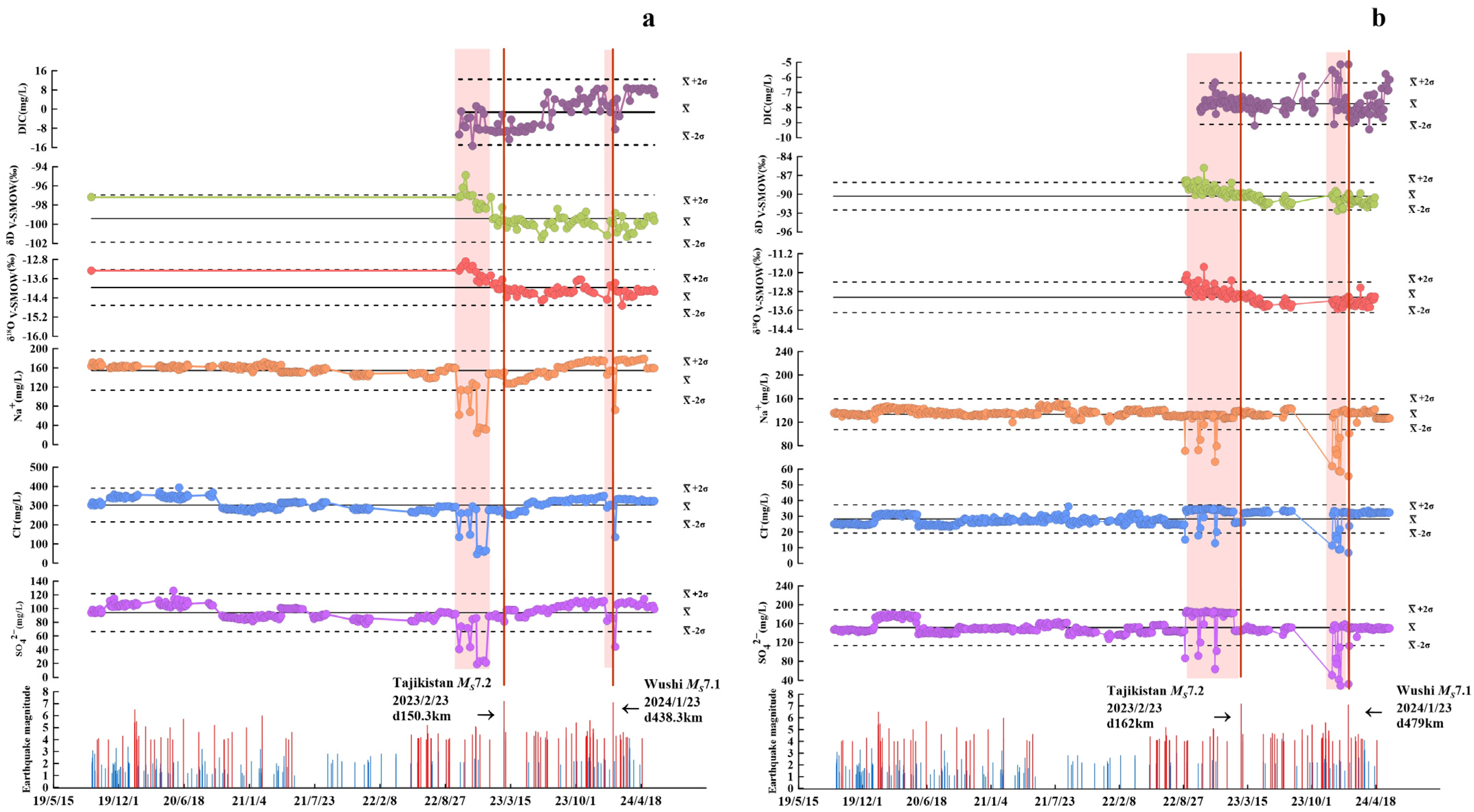

5.5. Correlation Between Hydrogeochemical Changes and Earthquakes

5.5.1. Consistency with Existing Hydrogeochemical Precursor Mechanisms

5.5.2. Distance-Dependent Anomaly Intensity and Temporal Patterns

5.6. Fluid Circulation Model of Hot Spring in the MJF

- Inter-seismic Fluid Circulation Model

- 2.

- Fluid Dynamic Response Model Under Intense Tectonic Stress Perturbation

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Hydrochemical and isotopic characteristics collectively indicate that the geothermal waters in the study area are primarily recharged by meteoric precipitation. During deep circulation, the waters form a HCO3-Ca-Mg type through water–rock interaction dominated by the dissolution of carbonate rocks. These deep hot waters, ascending along the fault zone under compressional stress, ultimately mix with shallow cold water, leading to their chemically “immature” signature.

- (2)

- Na+, Cl−, and SO42− are sensitive indicators exhibiting significant pre-seismic anomalies in the study area. The characteristic decrease in these ion concentrations observed before strong earthquakes can be attributed to a coupled “enhanced-permeability–cold-water-mixing–dilution” mechanism: pre-seismic stress accumulation enhances fault zone permeability, allowing shallow, low-TDS cold water to mix with and dilute the deep geothermal fluid more efficiently.

- (3)

- A conceptual model of fluid circulation and seismic response was established, explaining the entire fluid pathway from recharge to discharge and revealing its dynamic response to changes in tectonic stress. The observed hydrochemical changes effectively track fluid–tectonic interactions. Future research should focus on expanding long-term monitoring networks to include more springs and mud volcanoes, quantifying the sensitivity of geochemical indicators to different magnitudes of tectonic disturbance, and integrating geophysical data (e.g., GPS, InSAR) to further refine the fluid–tectonic–seismic interaction mechanism in fault-controlled geothermal systems.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MJF | Muji Fault Zone |

| THM | Tahman Spring |

| BLK | Bulake Village Spring |

| SFKM | Southern Fault of the Kungai Mountains |

| δD | Deuterium isotope ratio (relative to V-SMOW) |

| δ18O | Oxygen-18 isotope ratio (relative to V-SMOW) |

| δ13C DIC | δ13C in dissolved inorganic carbon |

| δ13C CO2 | δ13C in CO2 |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviation |

| TDS | Total dissolved solids |

| GMWL | Global Meteoric Water Line |

| LMWL | Local Meteoric Water Line |

| EFi | Enrichment Factors |

| SI | Saturation Index |

References

- Nishio, Y. Geofluid research using lithium isotopic tool advances understanding of whole crustal activity. J. Jpn. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2013, 43, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, D.; Kanamori, H.; Negishi, H.; Wiens, D. Tomography of the source area of the 1995 Kobe earthquake: Evidence for fluids at the hypocenter? Science 1996, 274, 1891–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandvakili, Z.; Nishio, Y.; Sano, Y. Geofluid behavior prior to the 2018 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi earthquake: Insights from groundwater geochemistry. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2024, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, L.; Skelton, A.; Graham, C.; Dietl, C.; Mörth, M.; Torssander, P.; Kockum, I. Hydrogeochemical changes before and after a major earthquake. Geology 2004, 32, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.R.; Banjara, S.P.; Wagle, A.; Freund, F.T. Earthquake chemical precursors in groundwater: A review. J. Seismol. 2018, 22, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, T.; Saltalippi, C.; Jean, J.-S. Coseismic hydro-environmental changes: Insights from recent earthquakes. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.; Liljedahl-Claesson, L.; Wasteby, N.; Andren, M.; Stockmann, G.; Sturkell, E.; Morth, C.M.; Stefansson, A.; Tollefsen, E.; Siegmund, H.; et al. Hydrochemical Changes Before and After Earthquakes Based on Long-Term Measurements of Multiple Parameters at Two Sites in Northern Iceland—A Review. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2019, 124, 2702–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, J.; Jiang, X.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Y. Reactive Transport Process of Earthquake-induced Hydro-chemical Changes in Guanding Thermal Spring, Western Sichuan, China. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2024, 98, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, C. Earthquake-related hydrochemical changes in thermal springs in the Xianshuihe Fault zone, Western China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 579, 124175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P.; Forster, C.B.; Goddard, J.V. Permeability of fault-related rocks, and implications for hydraulic structure of fault zones. J. Struct. Geol. 1997, 19, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibson, R.H. Fluid involvement in normal faulting. J. Geodyn. 2000, 29, 469–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchi, M. Faults controlling geothermal fluid flow in low permeability rock volumes: An example from the exhumed geothermal system of eastern Elba Island (northern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). Geothermics 2020, 85, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.C.; Menzies, C.D.; Sutherland, R.; Denys, P.H.; Chamberlain, C.; Teagle, D.A. Changes in hot spring temperature and hydrogeology of the Alpine Fault hanging wall, New Zealand, induced by distal South Island earthquakes. In Crustal Permeability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 228–248. [Google Scholar]

- Leloup, P.H.; Lacassin, R.; Tapponnier, P.; Scharer, U.; Zhong, D.L.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, L.S.; Ji, S.C.; Trinh, P.T. The Ailao Shan-Red River shear zone (Yunnan, China), Tertiary transform boundary of Indochina. Tectonophysics 1995, 251, 3–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, Y. Rheological characteristics of lithospheric mantle in the Pamir Plateau and temperature structure of its northeastern margin: Results of the Third Xinjiang Comprehensive Scientific Expedition on Geothermal Science. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chin. Ed. 2025, 68, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelnokov, G.; Lavrushin, V.; Bragin, I.; Abdullaev, A.; Aidarkozhina, A.; Kharitonova, N. Geochemistry of Thermal and Cold Mineral Water and Gases of the Tien Shan and the Pamir. Water 2022, 14, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lin, J.; He, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Qi, S. Analysis of geothermal resources in the northeast margin of the Pamir plateau. Geothermics 2025, 127, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pang, Z.; Yang, F.; Yuan, L.; Tang, P. Hydrogeochemical characteristics and genesis of the high-temperature geothermal system in the Tashkorgan basin of the Pamir syntax, western China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 149, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, P.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, C.; Yan, Y. Environmental Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Hot Springs in Tashkurgan Fault Zone of Xinjiang, China. J. Earch Sci. Environ. 2022, 44, 699–712. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, B. The attributes and characteristics of “Muji volcano group” in Xinjiang. Acta Geol. Sin. 2024, 98, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Li, J.; Liu, D. InSAR study of current tectonie deformation and seismie hazard analysis ofthe Kongur tension system in northeastern Pamir’s. Bull. Surv. Mapp 2024, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; He, G.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Qi, S. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics and Genesis of Medium-High Temperature Geothermal System in Northeast Margin of Pamir Plateau. Editor. Comm. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2024, 49, 3736–3748. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Qi, S.; Wang, S.; He, G.; Zhao, B. Unraveling the Genesis of the Geothermal System at the Northeastern Edge of the Pamir Plateau. Water 2023, 15, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Harrison, T.M. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 211–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Rai, S.S.; Hawkins, R.; Bodin, T. Seismic imaging of crust beneath the western Tibet-Pamir and Western Himalaya using ambient noise and earthquake data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Song, X.; Wu, D.; Shan, X. Present-Day Tectonic Deformation Characteristics of the Northeastern Pamir Margin Constrained by InSAR and GPS Observations. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Schoenbohm, L.M.; Chen, J.; Yuan, Z.; Feng, W.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Owen, L.A.; Sobel, E.R.; Zhang, B.; et al. Cumulative and Coseismic (During the 2016 Mw 6.6 Aketao Earthquake) Deformation of the Dextral-Slip Muji Fault, Northeastern Pamir Orogen. Tectonics 2019, 38, 3975–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, L.; Hicks, S.; Garth, T.; Gonzalez, P.; Rietbrock, A. ‘Two go together’: Near-simultaneous moment release of two asperities during the 2016 Mw 6.6 Muji, China earthquake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018, 491, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Qiao, X.; Chen, W.; Zhou, Y. Source model of 2016 Mw 6.6 Aketao earthquake, Xinjiang derived from Sentinel-1 InSAR observation. Geod. Geodyn. 2018, 9, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, L.-S.; Li, L.; Yi, L.; Feng, W. Confirmation of the double-asperity model for the 2016 MW 6.6 Akto earthquake (NW China) by seismic and InSAR data. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 184, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, W.; Schurr, B.; Yuan, X.; Ratschbacher, L.; Reuter, S.; Kufner, S.K.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, J. Structure and stress field of the lithosphere between Pamir and Tarim. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL095413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, T.; Sun, J.; Fang, L.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Fu, B. Coseismic surface ruptures and seismogenic Muji fault of the 25 November 2016 Arketao MW 6.6 earthquake in northern Pamir. Seismol. Geol. 2016, 38, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Steinshouer, D.W.; Qiang, J.; McCabe, P.J.; Ryder, R.T. Maps Showing Geology, Oil and Gas Fields, and Geologic Provinces of the Asia Pacific Region; 2331-1258; US Geological Survey: Fairfax County, VA, USA, 1999.

- Zhonghe, P. Mechanism of water cycle changes and implications on water resources regulation in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. Quat. Sci. 2014, 34, 907–917. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; He, M.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yao, B.; Cui, S.; et al. Seismic Signals of the Wushi MS7.1 Earthquake of 23 January 2024, Viewed Through the Angle of Hydrogeochemical Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11885: 2007; Water Quality-Determination of Selected Elements by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2009.

- Assayag, N.; Rivé, K.; Ader, M.; Jézéquel, D.; Agrinier, P. Improved method for isotopic and quantitative analysis of dissolved inorganic carbon in natural water samples. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 20, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alixiati, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Abudutayier, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Li, G.; Chen, L. Analysis of Gravity Changes Before and After Aktao Earthquake with Ms 6.7, 2016. Inland Earthq. 2017, 31, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, G.; He, M.; Tian, J.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Geochemical characteristics of hot springs in active fault zones within the northern Sichuan-Yunnan block: Geochemical evidence for tectonic activity. J. Hydrol. 2024, 635, 131179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.N. Ionic Equilibrium: Solubility and pH Calculations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chun-hui, C.; Ming-jie, Z.; Qing-yan, T.; Zong-gang, L.; Yang, W.; Li, D.; Zhong-ping, L. Geochemical characteristics and implications of shale gas in Longmaxi Formation, Sichuan Basin, China. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2015, 26, 1604–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Tian, J.; He, M.; Li, J.; Dong, J.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Xing, L.; Zheng, G. Constraints on geological structures and dynamics along the Tian Shan-Pamir orogenic belt with helium isotopes in hot springs. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 160, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Wakita, H. Geographical distribution of 3He/4He ratios in Japan: Implications for arc tectonics and incipient magmatism. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1985, 90, 8729–8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, Groundwater and Pollution, 2nd ed.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hanshaw, B.B.; Back, W. Major geochemical processes in the evolution of carbonate—Aquifer systems. J. Hydrol. 1979, 43, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.W.; Arvidson, R.S.; Lüttge, A. Calcium carbonate formation and dissolution. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 342–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Geothermal solute equilibria. derivation of Na-K-Mg-Ca geoindicators. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 2749–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnórsson, S.; Stefánsson, A.; Bjarnason, J.O. Fluid-fluid interactions in geothermal systems. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2007, 65, 259–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic variations in meteoric waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasch, K.W.; Bryson, J.R. Distinguishing sources of ground water recharge by using δ2H and δ18O. Groundwater 2007, 45, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortelainen, N.M.; Karhu, J.A. Regional and seasonal trends in the oxygen and hydrogen isotope ratios of Finnish groundwaters: A key for mean annual precipitation. J. Hydrol. 2004, 285, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Hughes, C.E.; Zhu, X.; Dong, L.; Ren, Z.; Chen, F. Factors controlling stable isotope composition of precipitation in arid conditions: An observation network in the Tianshan Mountains, central Asia. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2016, 68, 26206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Yao, T.; MacClune, K.; White, J.; Schilla, A.; Vaughn, B.; Vachon, R.; Ichiyanagi, K. Stable isotopic variations in west China: A consideration of moisture sources. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Yao, T.; Numaguti, A.; Sun, W. Stable isotope variations in monsoon precipitation on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2001, 79, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Kong, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, J. An isotopic geoindicator in the hydrological cycle. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 17, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Kong, Y.; Froehlich, K.; Huang, T.; Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, F. Processes affecting isotopes in precipitation of an arid region. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2011, 63, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.-X.; Wu, C.-H.; Zou, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, H.-Q.; Yue, X.-Y. Provenance analysis of Late Triassic turbidites in the eastern Songpan–Ganzi Flysch Complex: Sedimentary record of tectonic evolution of the eastern Paleo-Tethys Ocean. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 126, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, X.; Cui, H.; Wang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, X.; Luo, X.; Lin, Q. Formation Mechanism of Muji Travertine in the Pamirs Plateau, China. Minerals 2024, 14, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bufe, A.; Hovius, N.; Emberson, R.; Rugenstein, J.K.; Galy, A.; Hassenruck-Gudipati, H.J.; Chang, J.-M. Co-variation of silicate, carbonate and sulfide weathering drives CO2 release with erosion. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Cui, Q.; Zhou, Y. smic velocity structures and deep dynamic processes in the crust and mantle beneath the Tianshan Orogenic Belt. Rev. Geophys. Planet. Phys. 2024, 55, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Hongbing, T.; Yanfei, Z.; Wenjie, Z. Geochemical characteristics and source mechanism of geothermal water in Tethys Himalaya belt. Geol. China 2018, 45, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C. User’s Guide to PHREEQC (Version 2): A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations; US Geological Survey: Fairfax County, VA, USA, 1999.

- Arnórsson, S.; Gunnlaugsson, E.; Svavarsson, H. The chemistry of geothermal waters in Iceland. III. Chemical geothermometry in geothermal investigations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1983, 47, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, R. Chemical geothermometers and mixing models for geothermal systems. Geothermics 1977, 5, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.-Z.; Gao, P.; Rao, S.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Tang, X.-Y.; Huang, F.; Zhao, P.; Pang, Z.-H.; He, L.-J.; Hu, S.-B. Compilation of heat flow data in the continental area of China. Chin. J. Geophys. 2016, 59, 2892–2910. [Google Scholar]

- Kurz, M.D.; Meyer, P.S.; Sigurdsson, H. Helium isotopic systematics within the neovolcanic zones of Iceland. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1985, 74, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Huang, T.; Tian, J.; He, M.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, B. Origins of volatiles and helium fluxes from hydrothermal systems in the Eastern Himalayan Syntaxis and constraints on regional heat and tectonic activities. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakita, H. Water wells as possible indicators of tectonic strain. Science 1975, 189, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, Z.; Cui, Y.; Du, J. Gas geochemistry of the hot spring in the Litang fault zone, Southeast Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Geochem. 2017, 79, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Marty, B. Origin of carbon in fumarolic gas from island arcs. Chem. Geol. 1995, 119, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.C.; Hilton, D.R.; Muñoz, J.; Fischer, T.P.; Shaw, A.M. The effects of volatile recycling, degassing and crustal contamination on the helium and carbon geochemistry of hydrothermal fluids from the Southern Volcanic Zone of Chile. Chem. Geol. 2009, 266, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.; Williams, P.D. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hosono, T.; Masaki, Y. Post-seismic hydrochemical changes in regional groundwater flow systems in response to the 2016 Mw 7.0 Kumamoto earthquake. J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, C. Advances in research on earthquake fluids hydrogeology in China: A review. Earthq. Sci. 2013, 26, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunogai, U.; Wakita, H. Precursory chemical changes in ground water: Kobe earthquake, Japan. Science 1995, 269, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G. Groundwater trace elements change induced by M5.0 earthquake in Yunnan. J. Hydrol. 2020, 581, 124424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Peng, S. Hydrochemical and stable isotopes (δ2H and δ18O) changes of groundwater from a spring induced by local earthquakes, Northwest China. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Manga, M.; Nair, A.M.; Dixit, A.; Mahanta, C. Water geochemistry and stable isotope changes record groundwater mixing after a regional earthquake in Northeast India. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2024, 25, e2024GC011476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; He, M.; Tian, J.; Saimaiernaji, K.; Zhu, C.; Yan, W.; Ma, R. Hydrogeochemical characterization and precursor anomalies of hot springs in the North Tianshan orogen. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 158, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, L.; Aubaud, C.; Muehlenbachs, K. Efficient carbon recycling at the Central-Northern Lesser Antilles Arc: Implications to deep carbon recycling in global subduction zones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL086950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, R.; Hirschmann, M.M. The deep carbon cycle and melting in Earth’s interior. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 298, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N.-A.; Etiope, G. Carbon degassing from the lithosphere. Glob. Planet. Change 2002, 33, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, M.; Hilton, D.; Kreulen, R. Tracing crustal and slab contributions to arc magmatism in the Lesser Antilles island arc using helium and carbon relationships in geothermal fluids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1998, 62, 3323–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabine, C.L.; Heimann, M.; Artaxo, P.; Bakker, D.C.; Chen, C.-T.A.; Field, C.B.; Gruber, N.; Le Quéré, C.; Prinn, R.G.; Richey, J.E. Current status and past trends of the global carbon cycle. Scope-Sci. Comm. Probl. Environ. Int. Counc. Sci. Unions 2004, 62, 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Barberio, M.D.; Barbieri, M.; Billi, A.; Doglioni, C.; Petitta, M. Hydrogeochemical changes before and during the 2016 Amatrice-Norcia seismic sequence (central Italy). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.; Andrén, M.; Kristmannsdóttir, H.; Stockmann, G.; Mörth, C.-M.; Sveinbjörnsdóttir, Á.; Jónsson, S.; Sturkell, E.; Guðrúnardóttir, H.R.; Hjartarson, H. Changes in groundwater chemistry before two consecutive earthquakes in Iceland. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, L.; Chen, Z.; Sun, F.; Lu, C. A case study of 10 years groundwater radon monitoring along the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau and in its adjacent regions: Implications for earthquake surveillance. Appl. Geochem. 2021, 131, 105014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Wang, H.; Wright, T.J.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Shi, C.; Huang, J.; Wei, N. Crustal deformation in the India-Eurasia collision zone from 25 years of GPS measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9290–9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Site | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Bulake Spring 1 | 74.4583 | 39.1033 | 3524.51 |

| S2 | Mining Area Spring | 74.5436 | 39.1378 | 3714.62 |

| S3 | Bulake Spring 2 | 74.4092 | 39.2103 | 4020.47 |

| S4 (BLK) | Bulake Village Spring | 74.3253 | 39.1044 | 3523.78 |

| S5 | Muji River Spring 1 | 74.5089 | 39.0189 | 3447.81 |

| S6 | Muji River Spring 2 | 74.5019 | 39.0175 | 3458.14 |

| S7 | Border Defense Highway Spring | 74.3453 | 39.0667 | 3521.72 |

| S8 | Bridge—Under Spring | 74.2834 | 39.1144 | 3541.76 |

| S9 | Muji River Spring 3 | 74.5056 | 39.0003 | 3542.65 |

| S10 | Muji River Spring 4 | 74.5233 | 38.9981 | 3449.73 |

| S11 | Muji River Spring 5 | 74.5106 | 38.9989 | 3451.57 |

| S12 | Mud Volcano | 74.5383 | 39.1156 | 3448.79 |

| S13 | Muji River Spring 6 | 74.5214 | 39.1158 | 3450.81 |

| S14 | Muji River Spring 7 | 74.4981 | 39.0003 | 3468.80 |

| S15 | Qiongrang Village Spring 1 | 74.2419 | 38.9439 | 3593.09 |

| S16 | Qiongrang Village Spring 2 | 74.2678 | 38.9497 | 3587.50 |

| S17 | Qiongrang Village Spring 3 | 74.3097 | 38.9503 | 3560.15 |

| S18 | Qiongrang Village Spring 4 | 74.2669 | 38.9378 | 3590.24 |

| S19 | Qiongrang Village Spring 5 | 74.3433 | 38.9706 | 3551.90 |

| S20 | Qiate | 74.0756 | 38.8908 | 3846.30 |

| S21 | Winter Pasture | 74.1431 | 39.0936 | 4072.64 |

| S22 | Kuntibiesi Village | 74.6975 | 38.9001 | 3419.87 |

| S23 | Upstream Snowmelt Water | 75.0153 | 40.4547 | 3541.74 |

| S24 | Midstream Snowmelt Water | 73.9006 | 39.7658 | 2988.93 |

| S25 | Upstream River Water | 74.0919 | 39.7706 | 2699.03 |

| S26 | Midstream River Water | 74.3542 | 39.8433 | 2478.96 |

| S27 | Downstream River Water | 74.4544 | 39.9706 | 2699.73 |

| Sample | R/Ra | 3He/4He(R) | He (ppm) | 4He/20Ne | Ar% | H2 (ppm) | CO2 (%) | N2 (%) | O2 (%) | CH4 (%) | 4He/20Ne |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S4 | 0.03 | 4.26 × 10−8 | 394 | 205 | 0.16 | 2.4 | 74.80 | 24.409 | 0.0257 | 0.0399 | 205 |

| S5 | 0.06 | 8.93 × 10−8 | 32 | 64 | 0.062 | 1 | 94.60 | 4.8465 | 0.0442 | 0.0439 | 64 |

| S6 | 0.07 | 9.73 × 10−8 | 171 | 142 | 0.17 | 1.1 | 85.50 | 13.635 | 0.0408 | 0.0544 | 142 |

| S9 | 0.09 | 1.23 × 10−7 | 116 | 90 | 0.052 | 1 | 94.70 | 4.3602 | 0.0424 | 0.0422 | 90 |

| S10 | 0.07 | 9.67 × 10−8 | 56 | 222 | 0.035 | 0.9 | 96.90 | 2.5515 | 0.0676 | 0.0048 | 222 |

| S11 | 0.07 | 9.11 × 10−8 | 41 | 162 | 0.057 | 1.2 | 96.60 | 3.052 | 0.2467 | 0.048 | 162 |

| S13 | 0.09 | 1.32 × 10−7 | 297 | 53 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 73.80 | 25.468 | 0.032 | 0.0062 | 53 |

| S14 | 0.06 | 7.88 × 10−8 | 157 | 120 | 0.11 | 1.1 | 90.80 | 8.781 | 0.0304 | 0.007 | 120 |

| Sample | SiO2 (mg/L) | Quartz Thermometer Scale 1 (°C) | Circulation Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 5.7 | 102 | 1788 |

| S2 | 22.2 | 152 | 2681 |

| S3 | 3.6 | 86 | 1501 |

| S4 | 13.2 | 132 | 2325 |

| S5 | 19.7 | 148 | 2600 |

| S6 | 19.4 | 147 | 2588 |

| S7 | 4.1 | 91 | 1583 |

| S8 | 2.8 | 78 | 1349 |

| S9 | 23.9 | 155 | 2734 |

| S10 | 23.4 | 154 | 2721 |

| S11 | 23.6 | 155 | 2727 |

| S12 | 3.0 | 80 | 1394 |

| S13 | 20.7 | 149 | 2634 |

| S14 | 20.1 | 148 | 2615 |

| S15 | 2.0 | 67 | 1153 |

| S16 | 2.7 | 77 | 1335 |

| S17 | 2.3 | 70 | 1221 |

| S18 | 2.5 | 74 | 1280 |

| S19 | 2.0 | 67 | 1151 |

| S20 | 2.0 | 66 | 1140 |

| S21 | 5.8 | 102 | 1795 |

| S22 | 4.7 | 95 | 1667 |

| S23 | |||

| S24 | - | - | |

| S25 | - | - | |

| S26 | - | - | |

| S27 | - | - |

| Earthquake | Hot Spring | Anomaly Amplitude (Days Before the Earthquake) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO42− | Cl− | Na+ | δ18O | δD | δ13C (DIC) | ||

| Tajikistan Ms7.2 2023/2/23 | BLK d150.3 km | −5.10σ (120D) | −3.78σ (120D) | −6.65σ (120D) | 3.61σ (99D) | 2.84σ (99D) | −2.05σ (76D) |

| THM d162 km | −3.41σ (155D) | −3.27σ (155D) | −4.77σ (155D) | 4.11σ (94D) | 3.91σ (94D) | 1.99σ (63D) | |

| Wushi Ms7.1 2024/1/23 | BLK d480.3 km | −1.12σ (18D) | −0.28σ (18D) | −0.64σ (18D) | −1.41σ (12D) | −1.32σ (12D) | 1.42σ (28D) |

| THM d479 km | −5.26σ (49D) | −4.323σ (49D) | −6.73σ (49D) | −2.05σ (32D) | −1.52σ (32D) | 3.77σ (94D) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, S.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Tian, J.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yao, B.; Xing, G.; Dong, J.; et al. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Hot Springs and Mud Volcanoes and Their Short-Term Seismic Precursor Anomalies Around the Muji Fault Zone, Northeastern Pamir Plateau. Water 2025, 17, 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223241

Cui S, Zhang F, Zhou X, Li J, Tian J, Zeng Z, Wang Y, Yao B, Xing G, Dong J, et al. Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Hot Springs and Mud Volcanoes and Their Short-Term Seismic Precursor Anomalies Around the Muji Fault Zone, Northeastern Pamir Plateau. Water. 2025; 17(22):3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223241

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Shihan, Fenna Zhang, Xiaocheng Zhou, Jingchao Li, Jiao Tian, Zhaojun Zeng, Yuwen Wang, Bingyu Yao, Gaoyuan Xing, Jinyuan Dong, and et al. 2025. "Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Hot Springs and Mud Volcanoes and Their Short-Term Seismic Precursor Anomalies Around the Muji Fault Zone, Northeastern Pamir Plateau" Water 17, no. 22: 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223241

APA StyleCui, S., Zhang, F., Zhou, X., Li, J., Tian, J., Zeng, Z., Wang, Y., Yao, B., Xing, G., Dong, J., He, M., Yan, H., Li, R., Zheng, W., Saimaiernaji, K., Wang, C., Yan, W., & Ma, R. (2025). Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Hot Springs and Mud Volcanoes and Their Short-Term Seismic Precursor Anomalies Around the Muji Fault Zone, Northeastern Pamir Plateau. Water, 17(22), 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223241